2. Theoretical Framework: Impact-Inventory Parity (IIP)

This section develops the analytical framework that bridges the two canonical models of market microstructure: the information-based model of Kyle [

8] and the inventory-based model of Ho and Stoll [

12]. We derive a theoretical relationship— the Impact-Inventory Parity (IIP) —that predicts how the forces of adverse selection and inventory risk management interact.

We begin by defining the two fundamental relationships that capture market maker behaviour, and establish a benchmark parity condition under idealized assumptions. We then generalize the framework to account for realistic market features like fragmented dealership and non-linear costs. The section continues with an interpretation of market regimes through the lens of the IIP, and derivation of plausible parameter ranges. Finally, we ground IIP in the context of secondary financial power markets and discuss its relevance to the unique characteristics that power markets present.

2.1. The Duality of Information and Inventory

A market maker’s pricing decisions can be viewed through two complementary lenses, each captured by a distinct regression plot:

- 1.

The Kyle Plot is a regression of price changes with the signed order flow . The resulting slope measures market depth, or the price impact of a trade. A higher indicates lower liquidity, as the market maker must adjust prices more significantly to protect against informed trading. This is a reactive response to the informational content of order flow.

- 2.

The Ho-Stoll Plot is a regression of the deviation of the mid-price from its fundamental value with the market maker’s lagged inventory . The slope measures inventory aversion. A more negative indicates that the market maker aggressively skews quotes to offload inventory risk. This is a proactive apporach to manage the cost of holding an unbalanced position.

The central diagnostic of our framework is the Parity Index

defined as the ratio of the proactive inventory sensitivity to the reactive flow sensitivity

This index quantifies the balance between the two primary risks a market maker faces. A value of

suggests a balanced market where informational risk and inventory risk are managed in balance. Deviations from unity signal that one risk management dominates the other, defining distinct market regimes which we will explore later.

2.2. The Classical Parity Condition

Under the idealized conditions assumed in classical microstructure theory, a perfect duality exists between the informational impact of order flow and the price pressure from inventory management. We formalize this relationship by establishing a benchmark where competition is perfect and inventory costs are linear. In this special case, the Parity Index equals unity. This result is established through two complementary theorems.

Theorem 1 (Kyle on the Ho-Stoll plot). In a pure information-based market (no inventory tilt ) with a monopolistic market maker and linear costs, if price discovery follows the linear impact rule , the implied slope of the Ho-Stoll plot is .

Proof. Iterating the price update gives . The cumulative order flow is thus when . Combining these yields , a linear relationship with slope . □

Theorem 2 (Ho-Stoll on the Kyle plot). In a pure inventory-based market (no information impact ) with a monopolistic market maker and linear costs, if the market maker sets prices according to a linear inventory tilt , the implied slope of the Kyle plot is .

Proof. The price change is . Since the inventory update is , this yields , a linear relationship with slope . □

These theorems demonstrate that under idealized, single-factor conditions, the informational price impact and the inventory price pressure are perfectly symmetric. An information-only model generates an apparent inventory slope, while an inventory-only model generates an apparent informational slope. In a combined model where both effects are present,

and

, their impacts are additive. The slopes become

This leads to the parity condition

and thus

. This benchmark provides a sharp, parameter-free prediction that serves as a null hypothesis for testing the impact of more realistic market features.

2.3. The Generalized Parity Index

We now relax the classical assumptions to account for two critical features of real-world markets: fragmented dealership and non-linear inventory costs. We introduce two parameters to capture these effects:

- 1.

Liquidity Fragmentation: We define as the fraction of the total net order flow captured by the market maker. A value of represents a competitive environment where the market maker does not intermediate all trades.

- 2.

Convex Inventory Costs: We model non-linear costs using a symmetric cubic penalty term . This captures the escalating risk of holding large inventory positions, which requires more aggressive price adjustments.

These generalizations modify the model dynamics. The market maker updates their belief about the fundamental value

V based on the

total order flow, but their inventory changes only by the

captured flow

The pricing rule is updated to include the non-linear cost term

We use odd-ordered polynomial terms (

) to model symmetric, mean-reverting costs. An even-ordered term like

would be non-reverting, incorrectly pushing the price in the same direction for both long and short positions.

Under these generalized dynamics, we can derive the estimators for the Ho-Stoll and Kyle slopes. First, we establish a relationship between the market maker’s belief and their inventory. Since inventory accumulates only a fraction

of the flow that drives belief updates, the perceived price deviation for a given inventory level is amplified by

Using this relationship, we can now derive the explicit forms for the generalized Ho-Stoll and Kyle slopes.

The Ho-Stoll slope is the OLS estimator from the regression of price deviation

on lagged inventory

. We begin by expressing the price deviation entirely in terms of inventory. We substitute the belief-inventory relationship Equation

5 into the pricing rule Equation

4,

The OLS estimator is defined as

. Substituting our expression for the price deviation yields

Using the properties of covariance, this becomes

Assuming the inventory process is stationary with a mean of zero, we have

and

. The equation simplifies to

We recognize that this is a linear approximation of a non-linear process. The validity and tightness of this approximation will be empirically tested in

Section 4.5.

By definition, the kurtosis is

. Substituting this in gives the final exact expression for the generalized Ho-Stoll slope under our assumptions

The Kyle slope is the OLS estimator from the regression of price changes

on order flow

. We first derive the price change

To handle the cubic term, we substitute

and expand

Substituting this back gives the full expression for the price change

This reveals that the relationship between

and

is non-linear when

. To find the linear regression coefficient

, we must approximate this relationship. We do so under two standard assumptions: (1) that the net order flow

is independent of the market maker’s lagged inventory

, and (2) that we can neglect the impact of higher-order terms of order flow (

) on the linear projection. These higher order terms will typcially be neglible if the order flow distribution is symmetric about zero. The OLS estimator then isolates the expected value of the coefficient on the term linear in

Recognizing that

, we arrive at the approximated generalized Kyle slope

Substituting these two derived slopes from Equations

10 and

15) into the definition of the Parity Index yields the central equation of our framework,

2.4. Analysis of the Generalized Framework

The generalized form of the Impact-Inventory Parity reveals a fundamental tension between the effects of competition and non-linear costs. To clarify the interpretation, we can factorize Equation

16:

This factorization isolates two distinct mechanisms that drive deviations from the classical parity of

.

The first term

represents a competition effect. This factor captures the impact of liquidity fragmentation. As competition increases (

decreases), the market maker’s belief about the fundamental value is still updated by the

total market order flow, but their inventory changes by a smaller,

captured fraction of that flow. This creates a disconnect: the market maker’s inventory becomes a weaker proxy for the cumulative order flow that has informed their price. As shown in Equation

5, the relationship between belief deviation and inventory is amplified by

. This inflates the magnitude of the measured Ho-Stoll slope relative to the Kyle slope, pushing the Parity Index

upwards. In the absence of non-linear costs

, the second term equals one, and we recover the simple prediction that

.

The second term represents a kurtosis effect. This factor captures the impact of non-linear inventory costs. Convex costs strongly penalize large inventory positions, inducing aggressive mean-reversion in the market maker’s behaviour. This constrains the inventory distribution, leading to thinner tails than a standard Gaussian distribution, i.e., platykurtosis where . Because the inventory kurtosis K appears in the numerator while the Gaussian benchmark of appears in the denominator’s coefficient, a platykurtic distribution causes the numerator to be smaller than the denominator. This pushes the value of the second term below unity, thereby pushing the Parity Index downwards.

The IIP framework therefore reveals a core conflict: competition tends to increase , while non-linear costs tend to decrease it. The observed market state depends on the relative strength of these opposing forces and the emergent response of the inventory statistics to the underlying market structure.

2.5. Breakdown of Parity: The Covariation Remainder

The IIP framework derived thus far relies on a critical assumption: that the market maker’s behavioural parameters () remain constant regardless of market conditions. However, this assumption breaks down in thin power markets characterized by adaptive oligopolistic participants. Consider a concrete scenario: a market maker holding a large long position in power futures faces an incoming buy order. If they process this order using their standard information extraction , they risk accumulating an even larger long position, potentially approaching physical delivery obligations they cannot fulfill. A rational response is to become more cautious, extracting information more aggressively (higher effective ) to avoid further exposure. Conversely, when holding negligible inventory, the same market maker might process orders more passively.

This state-dependent behaviour is not merely a theoretical possibility but a practical necessity in power markets. Large players— generation companies, utilities —observe market makers’ quote patterns and can infer inventory positions. When they perceive vulnerability (large inventory imbalance), they may trade more aggressively to exploit it. The market maker, anticipating this, adjusts their response dynamically. Unlike anonymous equity markets where such adaptation is difficult to implement, the concentrated structure of power futures makes state-dependent behaviours both observable and important.

To quantify the magnitude of such dynamic behaviour, we consolidate all sources of linear price impact into a single, time-varying effective price impact coefficient

. This coefficient captures the baseline informational impact

, the inventory-hedging pressure

, and any additional adjustments made in response to current market state

where

represents price moves not caused by order flow. Summing these price changes gives the cumulative deviation from the fundamental value

To connect this cumulative impact to the current inventory

, we apply summation by parts (the discrete equivalent of integration by parts). This decomposes the relationship into the standard parity term and a new term that explicitly accounts for changes in the impact coefficient over time:

This identity reveals when and how the static IIP framework breaks down (for example, as a result of dealers becoming more cautious as they approach potentially unmanageable physical delivery obligations). If the price impact

remains constant (

), the Covariation Remainder vanishes, and we recover the static parity relationship scaled by

. However, when market makers adapt their information extraction based on inventory exposure, the Covariation Remainder becomes non-zero and systematically alters the measured Ho-Stoll slope.

The economic interpretation is straightforward: the term quantifies the correlation between changes in price impact and past inventory positions . When a market maker increases their price impact precisely when holding large inventory ( large), the Covariation Remainder accumulates systematically, breaking the classical parity prediction.

The Parity Index

therefore serves dual purposes: measuring static market structure (

) under time-invariant behaviour, and detecting dynamic, state-dependent adaptation when that assumption fails. In

Section 4.4, we test this breakdown empirically through controlled simulations.

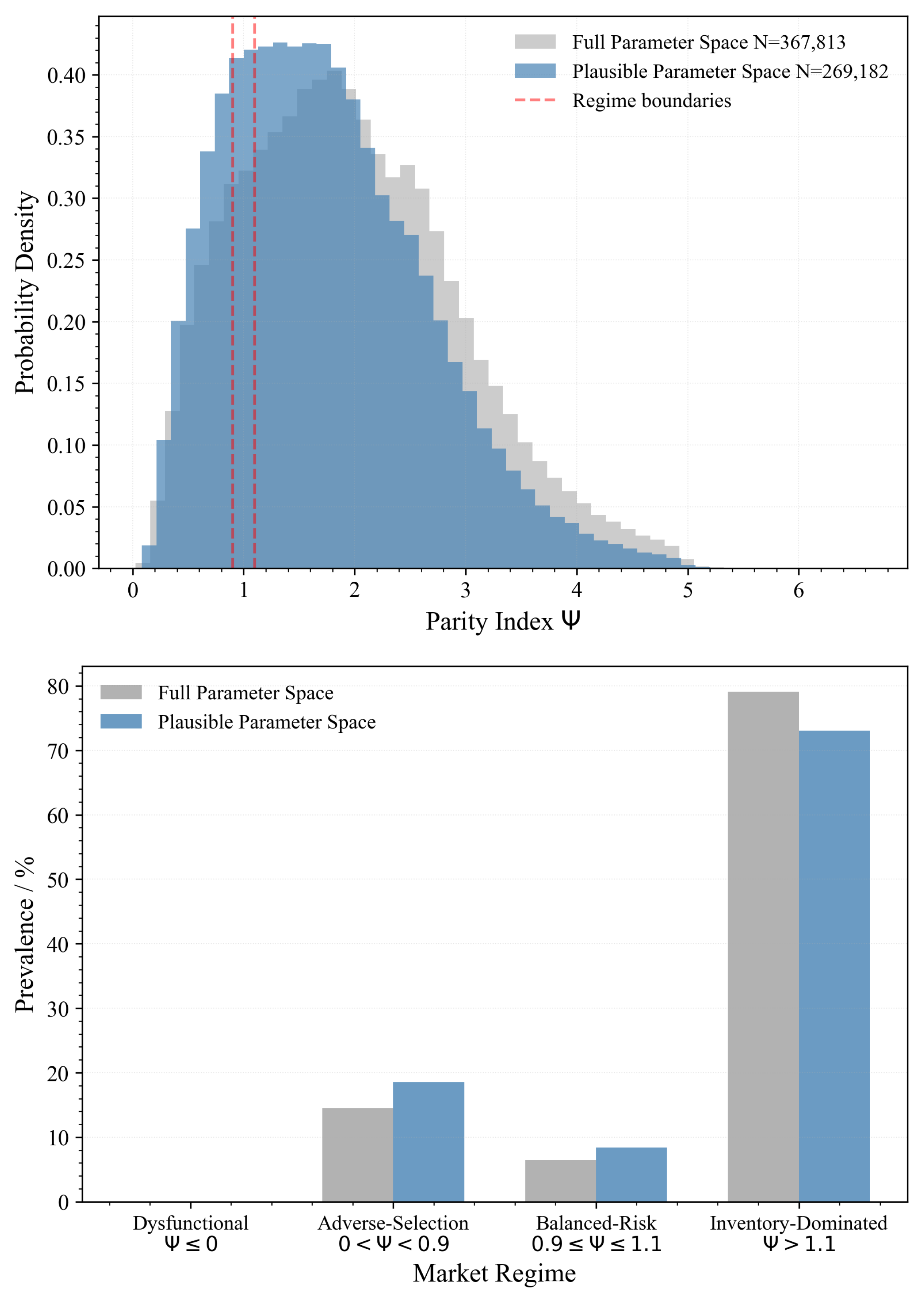

2.6. Defining Market Regimes

The theoretical framework developed thus far provides a powerful tool for diagnosing market dynamics, but its value lies in its connection to observable economic behaviour. While the condition of perfect parity serves as a theoretical benchmark, understanding the implications of deviations from this ideal is essential. In this section we classify the economic meaning of different values of into distinct market regimes; and establish physically grounded bounds on the underlying regression coefficients to ensure our analysis remains anchored in economic reality.

The Parity Index can be interpreted as a descriptor of the market maker’s dominant risk-management stance. By analyzing its value, we can move beyond a binary test of parity and classify the market into one of four primary regimes:

2.6.1. Regime 1: Inventory-Dominated Market

In this regime, the market maker’s pricing is more sensitive to their own inventory imbalance than to the informational content of incoming order flow . The dominant perceived risk is the cost of holding a large position. This is characteristic of a market with a high proportion of noise or liquidity trading, where the market maker acts as a classic inventory-balancing dealer, aggressively skewing quotes to offload risk.

2.6.2. Regime 2: Balanced-Risk Market

This regime represents the theoretical ideal of Impact-Inventory Parity . Here, the price impact from a trade (a reactive measure against adverse selection) is perfectly offset by the price adjustment made to manage the resulting inventory (a proactive measure). This corresponds to a well-functioning, efficient dealership market where both primary risks are managed in equilibrium. We define this regime as a relatively tight band around unity .

2.6.3. Regime 3: Adverse-Selection-Dominated Market

When is less than one, the market maker’s pricing is more sensitive to the informational content of order flow than to their inventory position . The dominant risk is adverse selection. The market maker acts more like an information processor, reacting strongly to each trade while tolerating larger short-term inventory imbalances to avoid losses to better-informed traders. This regime is characteristic of a market with a high proportion of informed trading.

2.6.4. Regime 4: Dysfunctional Non-Dealership Market

A negative value for signifies a breakdown of the rational dealership model. Assuming a positive price impact , a negative implies that . This would mean that the market maker raises their quote midpoint in response to accumulating a long inventory— an economically irrational behaviour. Such a result suggests that the emergent market dynamics do not conform to a dealership structure, perhaps because intense competition has decoupled the designated market maker’s inventory from the market’s overall price formation process.

An even more pathological scenario leading to occurs if price impact becomes negative while inventory management is also destabilizing . A negative would imply a complete reversal of price discovery: the market maker lowers the price in response to net buying and raises it in response to net selling, effectively paying traders to take liquidity. Simultaneously, a positive means the market maker raises prices when long and lowers them when short, actively working to worsen their inventory imbalance. While highly irrational, this combination represents a total failure of both the information-processing and inventory-management functions of a market maker.

In either case, a measured does not imply a flaw in the measurement itself, but rather signals that the emergent market dynamics do not conform to any rational dealership structure.

2.7. Plausible Order-of-Magnitude Parameter Bounds

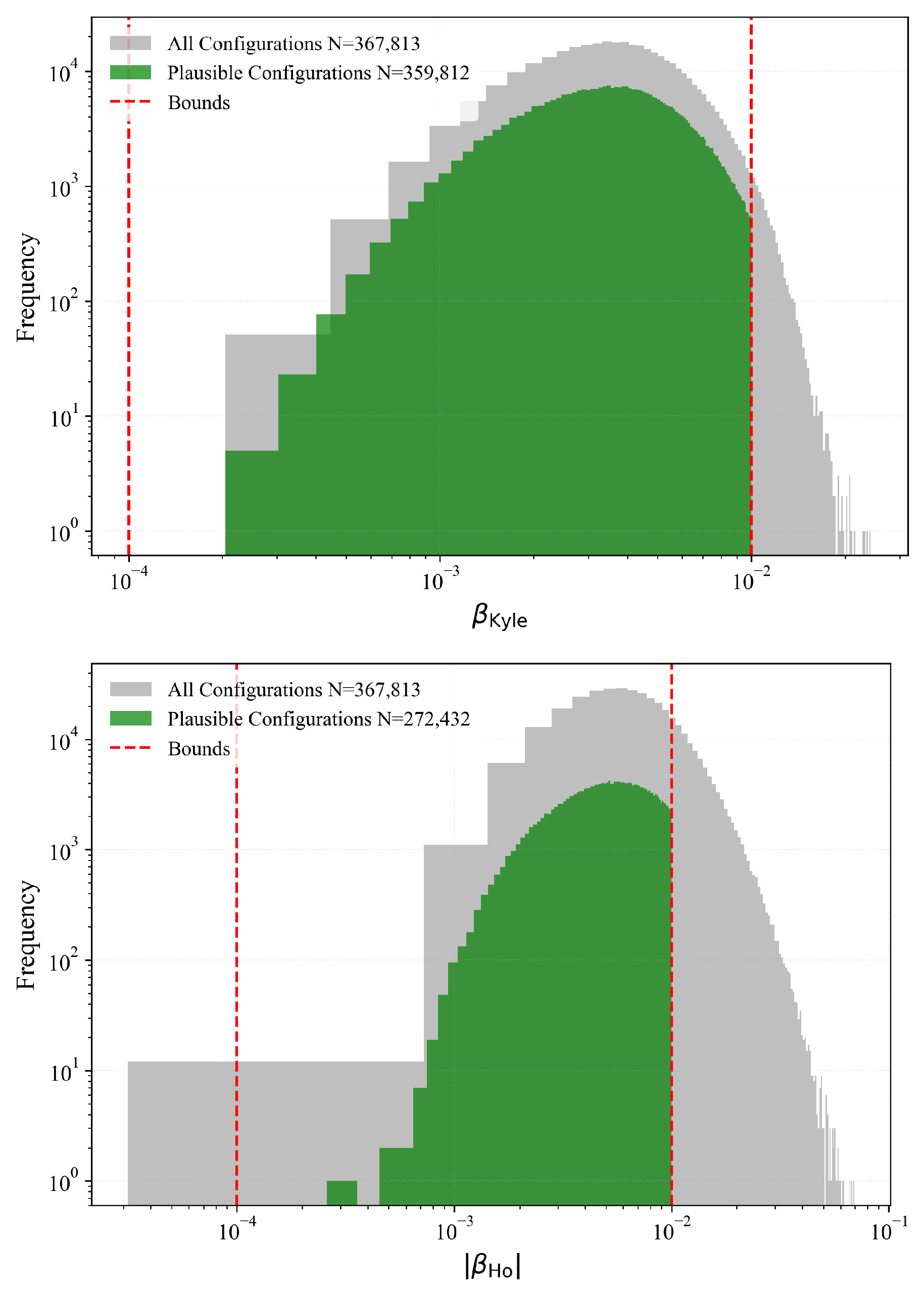

To ensure our analytical predictions apply to economically realistic markets, we establish physically grounded bounds for the two key regression coefficients and . These are derived from a dimensional analysis based on observable market characteristics: typical tick sizes , meaningful order sizes , and standard inventory positions . This anchoring in empirical scales identifies the relevant parameter space for testing the IIP predictions. Given the wide variation in these characteristics across markets, our goal is not spurious precision but the identification of a conservative, order-of-magnitude range for plausible market dynamics.

The Kyle coefficient is dimensionally the ratio of a characteristic price change to the order size that causes it

A representative tick size of

units is common in many futures and equity markets. Secondly, we define a characteristic order flow

as a meaningful, liquidity-demanding order, ranging from 10 to 100 contracts or lots. Finally, we assume the resulting price change

will be a small number of ticks in a liquid market (e.g., 1-10 ticks) but a larger number in an illiquid one (e.g., 10-100 ticks). This yields a range

The Ho-Stoll coefficient is dimensionally the ratio of a characteristic price skew to the inventory imbalance that necessitates it

Here, the characteristic inventory

represents a position large enough to require active management, which we assume to be in the range of 10 to 100 contracts. The price skew

is the amount in ticks that a market maker adjusts their quotes to attract offsetting flow. This might be a few ticks (e.g., 1-10) for moderate inventory pressure but could become much larger (e.g., 10-100 ticks) under severe constraints. This gives the range for its absolute value

This independent analysis yields a similar range for

as for

. This is a notable finding, as it ensures that the condition of parity

is physically achievable across the full spectrum of plausible market conditions. At the lower end, values near

for both

and

represent highly liquid markets where both price impact from large orders and price skewing for large inventories are minimal. The upper end approaching

corresponds to illiquid markets where prices are highly sensitive to both order flow and inventory imbalances, while the intermediate band of

captures the dynamics of typical electronic markets.

2.8. Relevance of the IIP Framework for Power Markets

While the IIP framework is a general theory of market making, its individual components are particularly suited to address the specific structural challenges inherent in secondary financial power markets. The core assumptions of classical models often fail in this environment, whereas the generalizations we have introduced directly map to the defining features of electricity trading.

2.8.1. Acute Inventory Risk and Non-Storability

A particular characteristic of electricity as an asset is its non-storability. For a market maker in power futures, inventory risk is not merely a financial concern about price fluctuations; as a contract nears expiry, it becomes a risk of physical delivery obligation. Unlike a market maker in equities who can hold a position indefinitely, a power market maker accumulating a large short or long position faces the tangible prospect of having to source or deliver physical power— a specialized activity for which they are likely ill-equipped. This reality makes the inventory aversion parameters and especially the non-linear costs critically important. We can hypothesize that the fear of unmanageable physical positions will lead to strong, non-linear quote shading, making the kurtosis effect a dominant force in price formation.

2.8.2. Thin Markets and Limited Competition

Power futures markets are often thin, characterized by a small number of active participants and designated market makers. This stands in stark contrast to deep equity markets with dozens of competing liquidity providers. Consequently, the assumption of perfect competition is particularly inappropriate. The liquidity fragmentation parameter is central to modeling this environment, where it is the norm for any single market maker to capture only a fraction of the total order flow. The competition effect, which pushes upwards, is therefore expected to be a primary and persistent feature of these markets.

2.8.3. Adaptive Behaviour of Large Players

The participants in power markets are not anonymous noise traders. They are often large entities (e.g., generation companies, utilities) with significant market power and sophisticated knowledge of the underlying physical system. These players are capable of recognizing when a market maker may be vulnerable due to a large inventory imbalance. This creates the potential for strategic trading, where agents might increase their trade sizes or aggression precisely to exploit the market maker’s position. Such state-dependent behaviour is exactly what the Covariation Remainder is designed to capture. It is not merely a theoretical curiosity, but a necessary tool for detecting the impact of adaptive interactions that break the static assumptions of classical models.

In summary, the IIP framework provides a precise vocabulary to analyze the fundamental tension in power markets. It allows us to quantify the balance between a market maker’s fear of adverse selection from traders with superiour forecasts and their more pressing fear of accumulating untenable physical delivery obligations (). It provides the tools to measure how this balance is distorted by limited competition and exploited by adaptive agents . This framework is therefore essential for moving beyond transplanted financial models to a theory of market making genuinely tailored to the unique physics and economics of power.

3. Methodology: Agent-Based Simulation and Econometrics

Having established the Impact-Inventory Parity as our theoretical framework, we now turn to the methodology used to test its predictions through simulations unconstrained by direct implementation of those predictions: the IIP relationships must arise emergent from micro-level agent interactions.

Testing the theory on real-world power markets is challenging. Empirical data is scarce, and the high concentration of participants makes it difficult to isolate the causal effects of competition or adaptive behaviour. Analytical models require simplifying assumptions— perfect competition, linear costs, and time-invariant behaviours— that are precisely the conditions our framework seeks to relax. This section details our use of Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) as a computational laboratory to bridge this gap. We outline the simulation design, the agent architecture, and the econometric protocol used to measure emergent market dynamics.

3.1. Rationale for Agent-Based Modeling in Power Markets

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) provides a bottom-up approach to studying complex economic systems where traditional methods fall short. An ABM constructs a simulated market from the micro-level interactions of heterogeneous agents, each with specific objectives and behavioural rules. This methodology is particularly well-suited for testing the IIP framework in power markets for three key reasons:

- 1.

Controlled experimentation. The ABM environment allows us to surgically introduce and isolate the mechanisms that our theory predicts are important. We can precisely control the level of competition , the degree of non-linear inventory costs , or introduce specific adaptive behaviours . This enables us to test the causal impact of each factor on the Parity Index in a way that is impossible with observational data.

- 2.

Perfect observability. Unlike real markets, the internal states of our agents are fully observable. We can track the market maker’s belief about the fundamental value , their inventory position , and the true fundamental value V itself. This allows us to directly estimate all components of the IIP framework, including the Ho-Stoll slope , which requires knowledge of the fundamental value— a quantity that is unobservable in real markets.

- 3.

Emergent macro-outcomes from programmed micro-behaviour. This separation between micro-level programming and macro-level outcomes is the methodological foundation of our test. We program agents with competitive behavioural rules derived from classical microstructure theory: informed traders exploit private signals according to the Kyle framework, market makers adjust quotes based on inventory following Ho-Stoll principles, noise traders submit random orders. Critically, we implement only the implicit assumptions of these canonical models at the agent level. We do not program the predicted market-level parity relationships. The key regression coefficients and must emerge from the collective interaction of agents over thousands of trading periods. Whether these emergent, statistically measured coefficients align with our theoretical predictions–— whether micro-level assumptions generate macro-level parity –—constitutes the empirical test of the IIP framework.

This methodology allows us to rigorously explore the conditions under which canonical microstructure theories hold and, critically, to identify and quantify the mechanisms through which they break down in the environment of thin power markets.

3.2. Simulation Environment and Agents

Our ABM is designed as a minimal yet robust representation of a continuous limit order market that combines the core mechanics of both information-based and inventory-based microstructure theories. The simulation proceeds in discrete time steps , within which a cast of heterogeneous agents interact around a single traded asset with a fixed fundamental value V.

3.2.1. The Market Maker (MM)

At the heart of the simulation is a single, risk-averse market maker who must simultaneously manage two distinct risks. At the beginning of each period

t, the MM posts a mid-price

according to the pricing rule

where

is the MM’s current belief about the fundamental value,

is their inventory position from the previous period,

is the linear inventory aversion parameter, and

is the non-linear (cubic) inventory cost parameter. This pricing rule implements the Ho-Stoll framework: the MM proactively skews quotes away from the fundamental value to attract offsetting order flow and manage inventory risk. After observing the aggregate order flow

in period

t, the MM updates their belief about the fundamental value according to

where

is the price impact coefficient. This belief update implements the Kyle framework: the MM learns from order flow, treating net buying pressure as a signal that informed traders perceive the asset to be undervalued.

In the baseline configuration,

is constant and equal to

, representing a fixed informational price impact. In some experiments we explore an simple adaptive price impact mechanism

where

is a state-dependence parameter. This captures the possibility that the MM becomes more cautious when holding large inventory positions, increasing their price impact response to order flow precisely when they are most vulnerable. This state-dependent behaviour is the mechanism underlying the Covariation Remainder derived in

Section 2.3. The MM’s inventory evolves according to

where

represents the fraction of total order flow captured by the MM. When

, the MM intermediates all trades (monopolistic dealership). When

, the MM faces competition from other liquidity providers who absorb a portion of the order flow.

3.2.2. Informed Traders

The simulation features

M informed traders who represent market participants with superior analytical capabilities. We adopt a differential information framework: at the start of the simulation, each trader

receives a unique, noisy private signal about the true fundamental value

This setup avoids the unrealistic assumption of a single, perfectly informed insider and better reflects a power market environment where participants (e.g., generation firms, weather forecasting specialists) form proprietary, imperfect views on future prices based on private analysis and data. In each period

t, each informed trader submits a market order proportional to the difference between their signal and the current mid-price

where

is the aggressiveness parameter that governs how much capital they deploy per unit of perceived mispricing. The aggregate informed order flow is thus

. Informed traders do not update their signals during the simulation, maintaining their initial differential information throughout.

3.2.3. Liquidity Traders

To represent hedgers and other non-speculative participants, liquidity trades arrive stochastically according to a Poisson process with arrival rate

. In each period

t, the number of arrivals is drawn as

. Each arriving liquidity trade is a market order to buy (+1 unit) or sell (

unit) with equal probability. The aggregate liquidity order flow is thus

These traders’ inelastic demand serves two essential functions: it creates the inventory risk that the market maker must manage, and it provides noise (camouflage) for the informed traders’ activity, making the market maker’s information-processing problem non-trivial.

3.2.4. Timing and Market Clearing

Within each period t, the sequence of events is

- 1.

The MM posts the mid-price based on their current belief and inventory .

- 2.

Informed traders observe and submit orders based on their signals.

- 3.

Liquidity traders arrive and submit random orders.

- 4.

The total order flow is executed against the MM’s quotes.

- 5.

The MM updates inventory: .

- 6.

The MM updates belief: .

The simulation runs for periods. The first periods allow the system to reach a statistical steady state, after which we collect data for periods for econometric analysis. All agents begin with zero inventory, and the MM’s initial belief is set to the true value .

3.3. Econometric Measurements

Let’s take stock of the mechanics of the simulation we are dealing with. The agent-based model generates a time series of market activity. At each period t, informed traders submit orders based on their private signals, liquidity traders arrive stochastically, and the market maker posts quotes reflecting their current belief about the fundamental value and inventory position . Trades execute, the market maker updates their inventory and their belief based on observed order flow , and a new mid-price forms. After running the simulation for periods, we observe complete time series: . At this point our data analysis can begin.

The central econometric question is: do these emergent price dynamics exhibit the Kyle relationship and the Ho-Stoll relationship predicted by theory? More precisely, can we reliably measure the regression coefficients and , and do they satisfy the parity prediction under idealized conditions?

To measure the emergent properties of the simulated market and test the IIP predictions, we employed a three-stage econometric statistical analysis. Unlike a deterministic model with closed-form solutions, our ABM is stochastic: random arrivals of liquidity traders, random signals for informed traders, and random order flow mean that each simulation run produces a different market trajectory. A single run could be misleading due to chance. Moreover, even within a single run, we estimate relationships from finite time-series data, introducing estimation error. Our analysis addressed both sources of uncertainty: we ran many independent simulations (addressing simulation variability), and we used appropriate time-series methods for each run (addressing estimation error). Finally, we pooled results across runs using statistical theory designed for multiple imperfect measurements. This ensures that our conclusions about the IIP framework are not artifacts of a lucky (or unlucky) random draw, but reflect the true emergent properties of the model.

3.3.1. Stability Filtering

Before any econometric analysis, we monitored each simulation for numerical stability. The model includes hard constraints to prevent explosive, uncontrolled growth that would indicate ill-conditioned dynamics rather than economically meaningful equilibrium behaviour. Specifically, we terminated and excluded any run where

Inventory position grew faster than the scaling expected from a random walk, indicating the MM had lost control of their position.

Price deviation exceeded a multiple of the fundamental value, indicating the market had detached from rational pricing.

These filters ensured that we analyzed only simulations exhibiting stable, economically interpretable dynamics. The proportion of runs that fail this test is not an indication of errors. Rather, the failure rate is a key diagnostic of market fragility that will be analyzed as a primary result in

Section 4.5.

3.3.2. Steady State Verification and Burn-in Period

Before collecting measurement data, we verified that the system had reached statistical steady state. We ran extended diagnostic simulations of 5000 periods and monitored rolling window statistics (window size = 100 periods) for key state variables: inventory position , belief error , and price deviation . Steady state was confirmed when the coefficient of variation of these rolling statistics fell below 2% and remained stable. Across all parameter configurations, we found that steady state was achieved within 500 periods. We therefore set for all experiments and discarded this initial transient period before econometric analysis.

3.3.3. Stage 1: Coefficient Estimation

For each stable simulation run, we collected

periods of data after discarding the initial burn-in period of

periods. We estimated the two primary coefficients using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression. The Kyle Coefficient

measures the price impact of order flow

This forward-looking specification captures how order flow in period

t affects the subsequent price

, consistent with the MM’s belief-update mechanism. Both the price change

and order flow

are stationary by construction, making standard OLS appropriate. We computed Newey-West (HAC) standard errors with automatic lag selection to account for potential autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity in the residuals.

The Ho-Stoll Coefficient

measures inventory sensitivity

Here we faced a more delicate statistical problem. Under the IIP framework’s dynamics, both inventory

and price deviation

are non-stationary: they accumulate past shocks rather than reverting to stable means (both are integrated of order one

processes). Regressing one non-stationary series on another without establishing cointegration risks producing a spurious regression: a statistically significant relationship that is merely an artifact of trending variables rather than a genuine economic connection.

However, the economic mechanism shared by both the Kyle and Ho-Stoll models predicts these variables should be cointegrated. Both inventory and price deviation are driven by the same underlying process—– cumulative order flow. Inventory accumulates captured order flow ; while price deviation accumulates the information extracted from that same order flow . Because they share a common stochastic driver, the theory predicts a stable long-run linear relationship between them, even as both variables wander individually.

To test whether this theoretical prediction holds in the simulated data, we applied the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test to the regression residuals . If the test rejected the null hypothesis of a unit root in the residuals at the 5% level, this confirmed the residuals are stationary and verified the cointegrating relationship predicted by theory. We then reported with HAC standard errors as a valid estimate of inventory sensitivity.

If cointegration failed— that is, if the ADF null hypothesis was not rejected at the 5% level —we discarded that run from further analysis. This failure was not merely a statistical technicality; it indicates that the simulation was ill-conditioned. The market may have failed to reach a steady state, exhibited explosive dynamics that escaped the stability filters, or produced economically incoherent behaviour that violated the IIP framework’s structural assumptions.

3.3.4. Stage 2: Parity Index Calculation

For runs which passed all filters and cointegration tests, we computed the Parity Index

To perform hypothesis tests on

, we calculated its standard error using the Delta method, which propagates the estimation uncertainty from the two underlying regressions, assuming asymptotic independence

3.3.5. Stage 3: Aggregation Across Runs

A single simulation represents one stochastic realization of the model. To obtain robust estimates that properly account for simulation variability, we performed independent simulations for each parameter configuration, each initialized with a different random seed. Point estimates and standard errors from valid runs (those passing stability checks and cointegration tests) were pooled using Rubin’s Rules, the established statistical method for combining multiple imperfect measurements.

Rubin’s Rules correctly combines within-run variance (estimation uncertainty from finite time-series data) and between-run variance (simulation uncertainty from stochastic agent behaviour). For any parameter

, such as

,

, or

,

where

is the number of runs passing all validity checks. The pooled estimate is

with standard error

. Confidence intervals were constructed using the

t-distribution with degrees of freedom calculated via the Barnard-Rubin approximation, which accounts for the finite number of simulations and the relative magnitudes of within-run and between-run uncertainty. This rigorous protocol ensured that our reported estimates of the Parity Index and its components are statistically sound, reflecting the true emergent behaviour of the model rather than sampling noise or unstable simulation artifacts.

4. Results: Testing the IIP Framework

This section presents results from numerical experiments designed to test the core predictions of the Impact-Inventory Parity (IIP) framework. We systematically examine the effects of liquidity fragmentation, non-linear inventory costs, and adaptive behaviour on market maker pricing. Simulations were conducted using the Agent-Based Model (ABM) architecture described in

Section 3.

The baseline parameters for the simulation environment and calibrated agent behaviours are summarized in

Table 1. The environmental parameters represent a moderately thin market structure characteristic of illiquid power futures contracts: a limited number of informed traders

, sparse liquidity provision

arrivals per period, and meaningful signal noise

reflecting the difficulty of forecasting power prices even with sophisticated analysis. These values generate order flow patterns and inventory dynamics consistent with the thin market conditions motivating the IIP framework.

The behavioural parameters

,

, and

were calibrated such that the classical parity condition

holds under idealized conditions of monopolistic dealership

and linear costs

. This calibration ensures that deviations from parity observed in subsequent experiments reflect the mechanisms under investigation (competition, non-linear costs, adaptive behaviour) rather than arbitrary parameter choices. The calibrated values also satisfy the dimensional consistency bounds established in

Section 2.7, producing regression coefficients

consistent with empirically observed price impacts in commodity futures markets.

4.1. Validation of Classical Parity and Competition Effect

We began by validating the model under the idealized conditions assumed by canonical microstructure theory: monopolistic dealership

, linear inventory costs

, and time-invariant response

. Under these conditions, the IIP framework predicts perfect parity with

. The simulation confirmed this benchmark with high precision:

(SE

,

) for the baseline market environment given in

Table 1. This validated both the ABM implementation and the econometric measurement protocol.

The competition effect, which predicts

under linear cost conditions

, demonstrated equally precise agreement with theory. We varied the flow capture rate

from 0.3 to 1.0 in eight steps, measuring the emergent Parity Index

at each level. Linear regression of measured

against

yielded

This alignment validated the theoretical mechanism derived in

Section 2.3: when

, the market maker observes total order flow

for belief updates but accumulates inventory based only on captured flow

. This structural disconnect creates a systematic amplification factor of

in the relationship between inventory position and price deviation in Equation.

5. The market maker’s inventory becomes a progressively weaker proxy for the cumulative order flow informing their price as competition increases, inflating the measured Ho-Stoll slope

relative to the Kyle slope

.

To assess robustness, we tested whether the competition effect persists across different market environments. We replicated the sweep in thin market configurations (; ) representing severely illiquid conditions. Despite these substantial changes in market structure and parameter values, the competition effect remained robust. Linear regression of measured against again yielded with a slope indistinguishable from unity. This confirms that the relationship is a structural feature of fragmented dealership that operates independently of market thickness, liquidity levels, or the specific calibration of behavioural parameters. The mechanism–— inventory decoupling from total order flow when –—proves universal across the thin market spectrum.

4.2. The Kurtosis Effect: Non-Linear Inventory Costs

Having validated the classical predictions under idealized conditions, we now examine the first mechanism that produces systematic deviations from parity: non-linear inventory costs. The theory predicts that convex costs

induce platykurtosis

in the inventory distribution, suppressing the Parity Index below unity. The mechanism operates through the generalized IIP given in Equation

17: non-linear terms contribute differently to the Kyle and Ho-Stoll slopes based on the inventory distribution’s higher moments, with the effect scaling with inventory variance

.

We tested this prediction by varying the non-linear cost parameter

from 0 to

across 11 steps, while maintaining monopolistic conditions

and non-adaptive behaviour

. The market maker’s pricing rule becomes

, where the cubic term penalizes large inventory positions with escalating severity. To assess how market thickness moderates this effect, we conducted experiments across seven market environments spanning a liquidity gradient from very liquid

to very thin

.

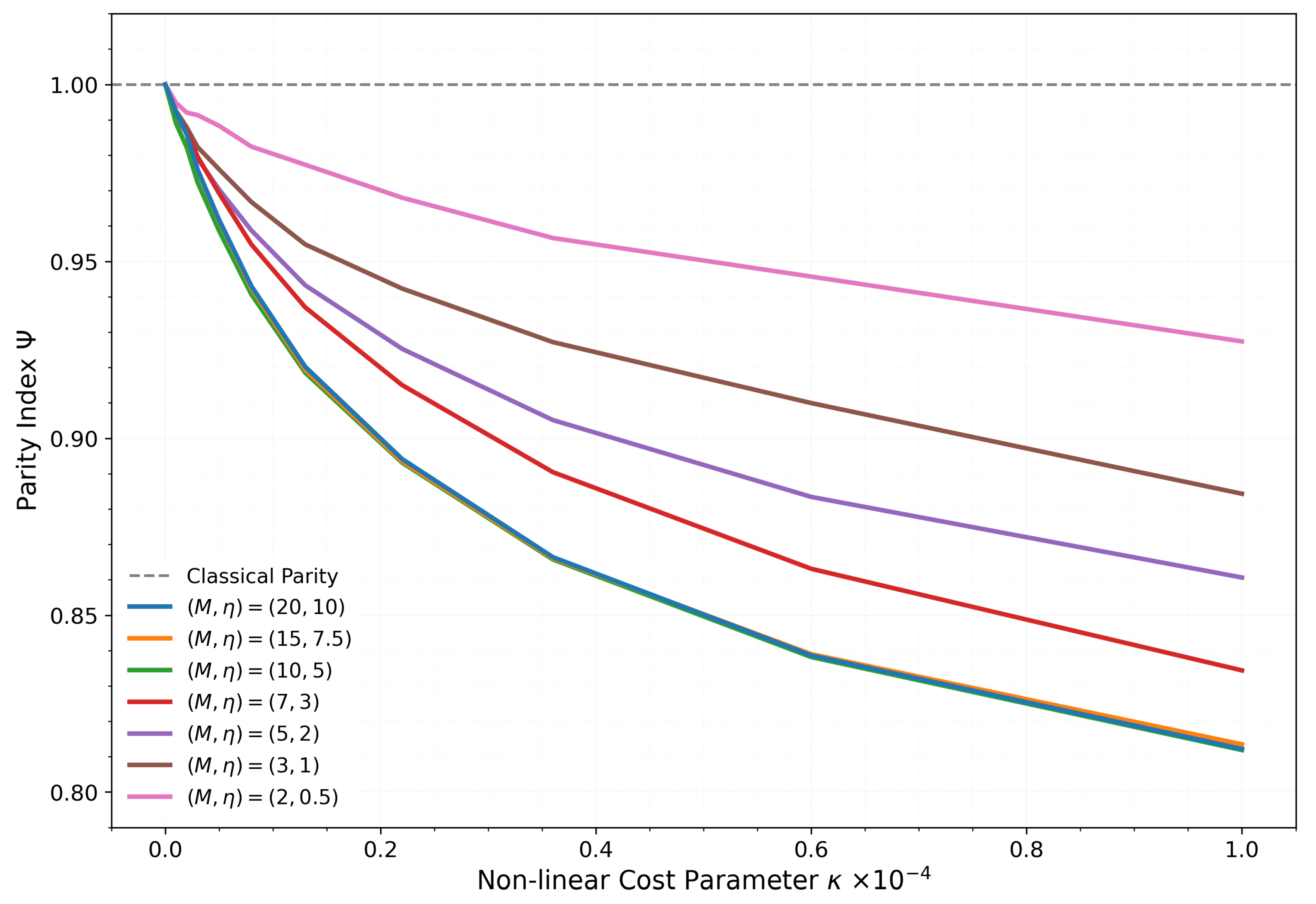

Figure 1 presents the results.

The results confirm the theoretical prediction across all market environments and reveal a consistent pattern. Starting from the validated classical parity

at

, all markets exhibit monotonic suppression of the Parity Index as non-linear costs increase. However, the magnitude of this suppression is strongly moderated by market thickness, producing a clear stratification visible in

Figure 1.

In the most liquid market , the kurtosis effect is most pronounced. The Parity Index falls from at to at , representing an 18.8% deviation from classical parity and a transition into the Adverse-Selection-Dominated regime (Regime 3, ). At this extreme, the market maker’s pricing becomes substantially more sensitive to order flow information than to inventory pressure.

As market thickness decreases, the suppression effect attenuates systematically. The baseline market shows at maximum , while moderately thin markets reach . In the thinnest environment , the effect is most muted: falls only to at , representing a 7.3% deviation— less than half the magnitude observed in liquid markets.

This stratification pattern is precisely predicted by the theoretical framework. The generalized IIP given in Equation

17 shows that the influence of

scales with inventory variance

. In thinner markets, reduced trading activity (lower

and fewer informed traders

M) leads to smaller absolute inventory swings, lowering

. With smaller inventory variance, the non-linear terms

and

in the numerator and denominator become smaller relative to the linear terms

and

, weakening the overall suppression of

. The market maker in a thin environment still employs the same convex cost structure, but accumulates smaller positions, reducing the practical impact of the non-linearity.

This finding has important implications for applying the IIP framework to illiquid power markets. While the kurtosis effect operates universally as theory predicts, its magnitude depends on the market’s trading intensity. Market makers in highly illiquid environments face elevated informational risk (reflected in higher equilibrium ) but accumulate smaller inventory positions, naturally limiting the severity of non-linear inventory costs. Even in the thinnest simulated market, however, strong convexity produces economically significant deviations from classical parity— the effect is attenuated but not eliminated. This suggests that inventory cost structures matter across the full spectrum of market conditions, though their relative importance declines as markets become thinner.

4.3. Joint Effects and Market Regime Boundaries

Having isolated the competition and kurtosis effects independently, we now examine their interaction by varying both parameters simultaneously across multiple market environments. This analysis maps the full landscape of market regimes that can emerge from the fundamental tension between these opposing forces and reveals how market thickness moderates their interaction.

We conducted two-dimensional parameter sweeps varying the flow capture rate

from 0.5 to 1.0 across six levels and the non-linear cost parameter

from 0 to

across six levels, yielding 36 parameter configurations. All configurations maintained non-adaptive behaviour

. We replicated this grid across four market environments spanning the liquidity gradient: very liquid

, baseline

, illiquid

, and thin

.

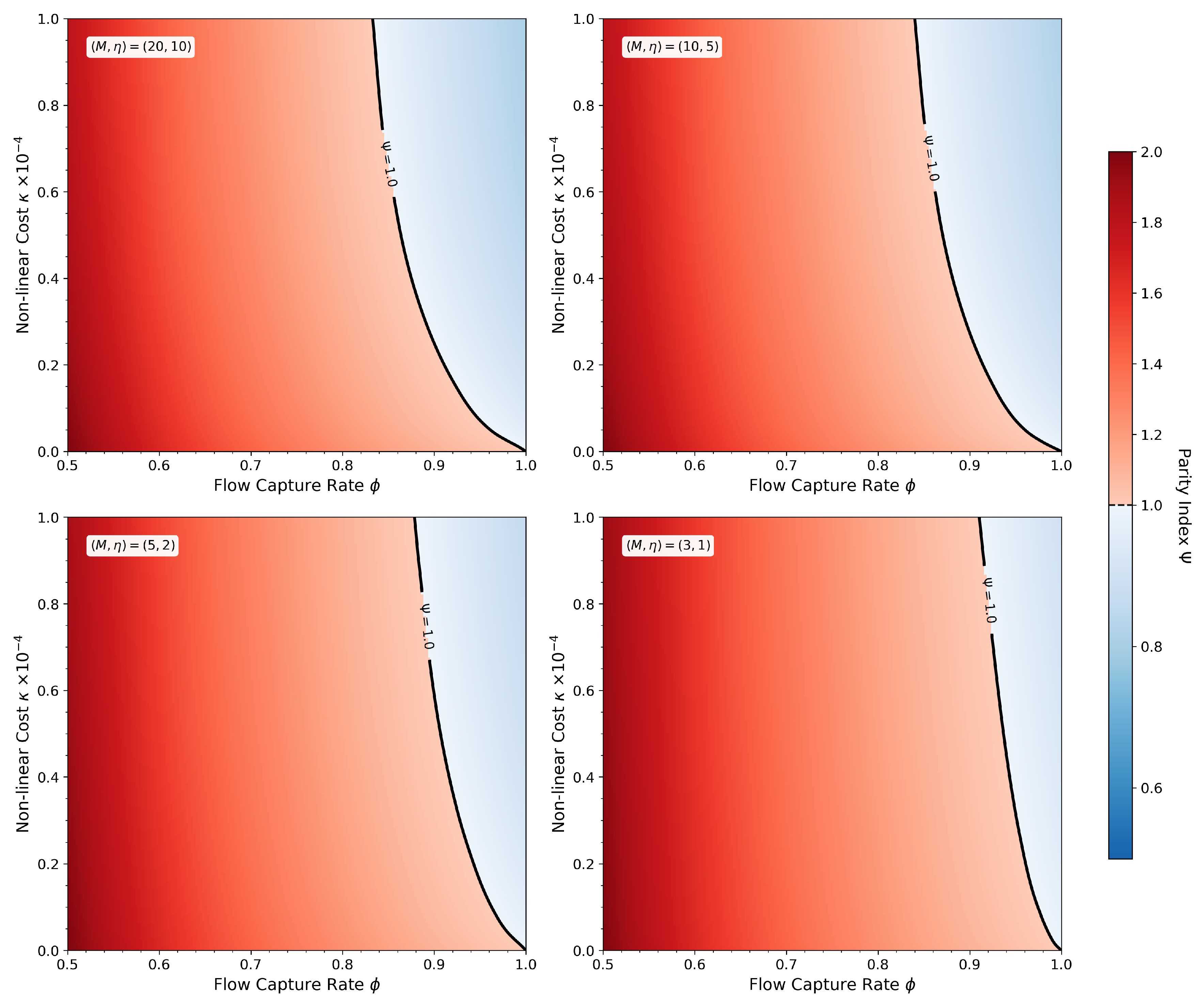

Figure 2 presents the results as heatmaps of the measured Parity Index across the parameter space for each market environment.

The heatmaps reveal consistent structural patterns across all market environments, with systematic variations in magnitude. In all four panels, three key features emerge:

- 1.

Competition dominance at low . The left edge of each heatmap (low , low ) exhibits elevated values, consistent with the isolated competition effect. Markets with show ranging from approximately 1.8 to 2.1 across the four environments (with linear costs ), placing them firmly in the Inventory-Dominated regime (Regime 1). This demonstrates that liquidity fragmentation systematically elevates inventory sensitivity relative to price impact, independent of market thickness.

- 2.

Kurtosis dominance at high . The upper-right region (high , high ) in all panels shows suppressed values below unity. Markets approaching monopolistic structure with strong convex costs exhibit , entering the Adverse-Selection-Dominated regime (Regime 3). This confirms that non-linear inventory costs can overcome the baseline parity condition through the kurtosis mechanism, again independent of market environment.

- 3.

Third, non-linear interaction and curved regime boundaries. Notably, the contour (black line) curves through the parameter space in all panels, demonstrating that the two effects do not combine linearly. As competition increases (lower ), progressively stronger non-linear costs are required to maintain balanced-risk conditions. A monopolistic market maker () achieves parity with linear costs , but introducing modest competition to requires to restore balance. At severe fragmentation , the required to achieve parity exceeds the tested range in all environments.

However, market thickness introduces quantitative moderation. Comparing across the four panels reveals systematic compression of the range as markets thin. In the very liquid market , the Parity Index spans approximately 0.75 to 2.1, a range of 1.35. This range compresses progressively as market thickness decreases: the baseline market exhibits a range of 1.20 (from 0.80 to 2.0), the illiquid market shows a range of 1.05 (from 0.85 to 1.9), and the thin market displays the most compressed range of 0.97 (from 0.88 to 1.85). This near-monotonic compression represents a 28% reduction in the parameter space’s dynamic range when moving from the most liquid to the thinnest market environment.

This compression reflects the attenuated kurtosis effect documented in

Section 4.2: thinner markets accumulate smaller inventory positions, reducing the impact of non-linear costs. Consequently, the blue region (Adverse-Selection-Dominated) shrinks in thinner markets, while the overall topology of the parameter space remains structurally similar.

The contour also shifts systematically. In the very liquid market, the balanced-risk boundary reaches lower into the parameter space (allowing higher values before exiting the balanced regime). In thin markets, the contour is pushed toward lower values, indicating that even modest non-linear costs can be sufficient to offset competition effects when inventory variance is low.

These findings reveal fundamental constraints on market design in thin, competitive environments. The structural force pushing toward inventory dominance (the competition effect) operates at full strength regardless of market thickness, while the countervailing kurtosis effect weakens in thin markets. This asymmetry suggests that severely fragmented thin markets may be inherently difficult to maintain in a balanced-risk state through inventory cost adjustments alone. For market maker programs in illiquid power futures, this implies that regulatory interventions to increase effective (by consolidating liquidity or providing exclusivity arrangements) may be more effective than relying on market makers to manage the imbalance through sophisticated inventory risk management.

4.4. Adaptive Behaviour and Parity Breakdown

The preceding experiments examined structural market features (competition, cost structure) that produce systematic but bounded deviations from classical parity. We now turn to a more fundamental question: under what conditions does the IIP framework itself break down?

Section 2.3 derived the Covariation Remainder, which quantifies how time-varying information processing causes deviations from the static parity relationship. To test this mechanism, we introduced a parsimonious parameterization where the market maker’s belief-updating intensity responds to inventory exposure,

This specification is not intended to represent an empirically measurable behavioural parameter. Rather, it serves as a minimal model to operationalize state-dependent information processing: the market maker extracts information more aggressively from order flow when inventory risk is elevated. The parameter

controls the intensity of this state-dependence, where

recovers the static Kyle model.

We tested the robustness of the IIP framework by varying

from 0 to 0.01 under controlled baseline conditions. The covariation remainder theory from Equation

20 predicts this adaptation should primarily affect the Kyle regression. When

varies systematically with inventory, the measured Kyle slope becomes

capturing both the baseline informational sensitivity

and the covariation between inventory exposure and order flow. In contrast, the Ho-Stoll regression measures the long-run cointegrating relationship between price deviation and inventory position, which should be less sensitive to the state-dependence of belief updating.

To test this mechanism comprehensively, we conducted a three-dimensional parameter sweep: varying

from 0 to 0.01 across six levels, market structure through three

combinations representing different competitive and cost environments, and market thickness through seven

configurations ranging from very liquid to very thin markets. This yields

distinct market configurations, and

for each configuration.

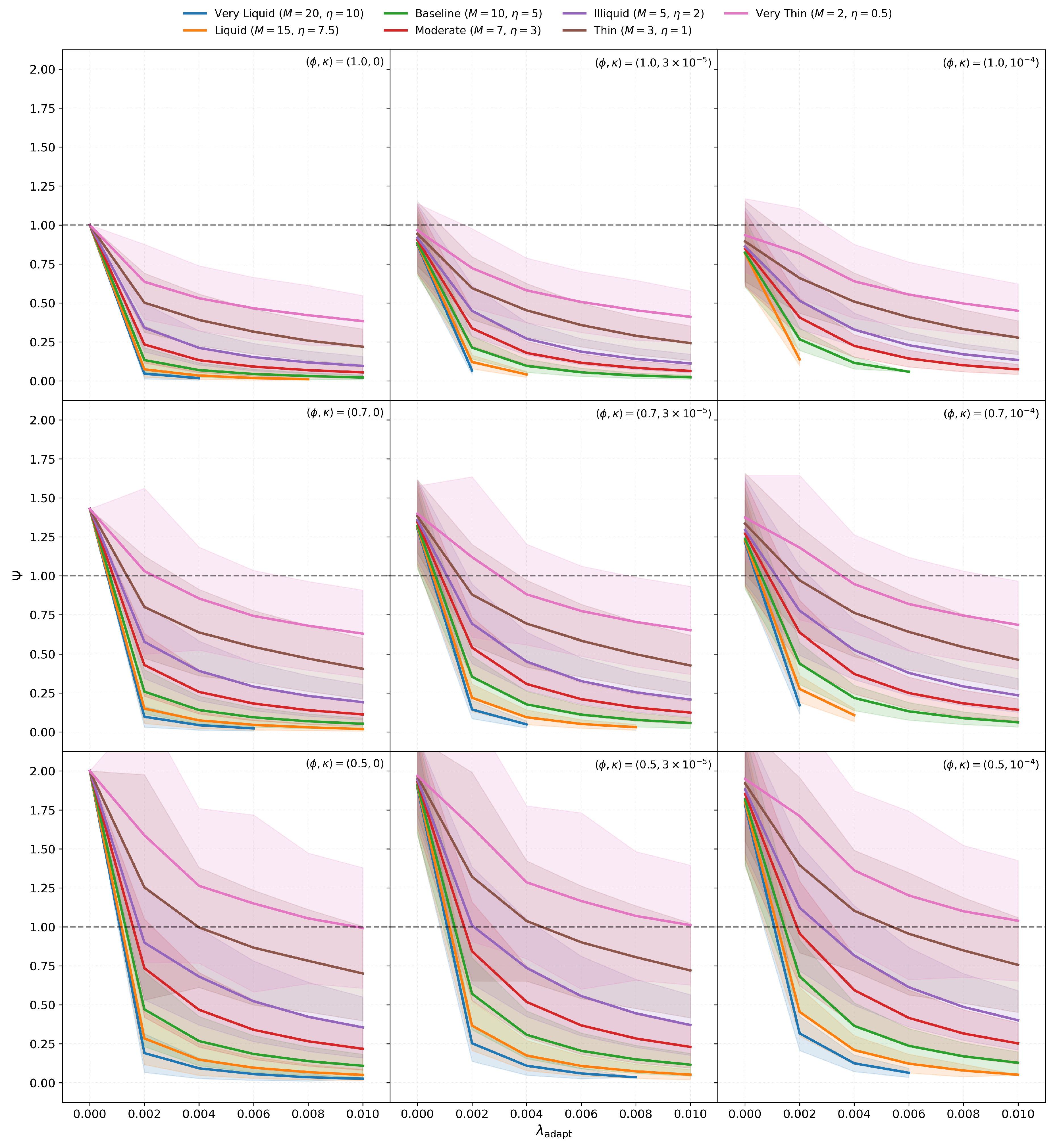

Figure 3 presents nine panels, one for each

combination, with each panel showing the response of all seven market environments.

The multi-panel results reveal three systematic patterns. First, liquidity amplifies collapse rather than providing stability. In monopolistic markets with linear costs (, ), very liquid markets (, ) declined from to approximately at — a nearly 20-fold decrease. Meanwhile, very thin markets (, ) declined only to under identical adaptation parameters. This systematic fan pattern is visible across all nine parameter combinations, with liquid markets (blue lines) always collapsing fastest and thin markets (pink lines) showing the greatest resilience.

The mechanism driving this thickness-dependence operates through inventory variance. In liquid markets, frequent trading generates large inventory excursions with variance potentially reaching 20-30 units squared. The covariation term thus becomes substantial, as the market maker frequently holds positions of units where adaptive information extraction is amplified. In thin markets, sparse trading produces smaller inventory excursions (–5), meaning rarely exceeds 2-3 units. The same parameter therefore generates weaker amplification, limiting the covariation remainder’s impact on the Kyle slope.

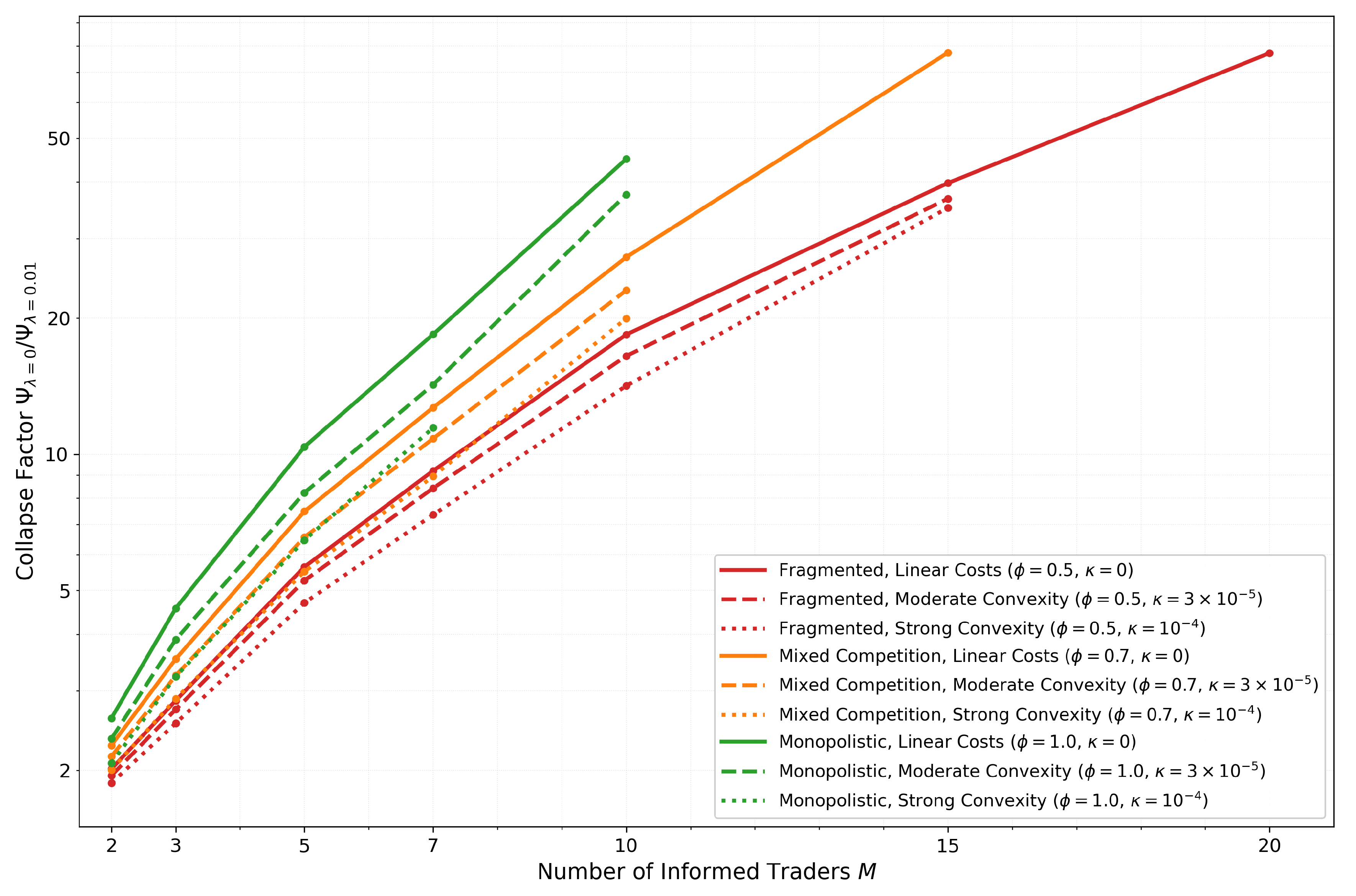

To quantify this relationship systematically,

Figure 4 plots the collapse factor against market thickness

M for all nine structural configurations. We defined this collapse factor as

: a measure of strength of

impact.

Three structural patterns emerge from this analysis. First, competition provides systematic protection against adaptive collapse. Monopolistic markets (, green lines) exhibit collapse factors reaching approximately 45 in very liquid environments, representing severe breakdown of the parity relationship. Markets with moderate competition (, orange lines) show reduced factors around 27, while severely fragmented markets (, red lines) limit collapse to approximately 18. This protective hierarchy persists across all market thickness levels and cost structures.

The protective mechanism of competition operates through inventory-flow decoupling. When , the market maker’s inventory accumulates only a fraction of the total order flow that informs their belief updates. This creates a natural damping effect: even when the market maker adapts their information extraction based on , that inventory position represents a weakened signal of cumulative information flow. The covariation remains bounded because scales down the inventory’s correlation with current flow. In monopolistic markets, this damping is absent— inventory perfectly tracks cumulative flow, maximizing the covariation term’s impact.

Second, non-linear costs provide consistent but secondary stabilization across all configurations. Within each colour group (fixed ), moving from solid to dashed to dotted lines (increasing ) systematically reduces collapse factors. For example, in monopolistic very liquid markets, linear costs (, solid green) yield approximately 45-fold collapse, while moderate non-linearity (, dashed green) reduces this to approximately 38-fold. The stabilization mechanism operates through inventory variance reduction: the cubic penalty term constrains inventory excursions, lowering and thereby reducing both and the sensitivity of the covariation remainder. However, this effect remains secondary, producing 15–25% reductions in collapse factors compared to the order-of-magnitude separations created by competition and thickness.

Third, the logarithmic scaling visible in

Figure 4 shows that collapse severity grows rapidly with market thickness. Adding informed traders to an already-liquid market produces substantially larger increases in collapse vulnerability than adding them to a thin market. Monopolistic markets exhibit the steepest growth rates, while competitive markets show shallower slopes.

These findings have important implications for interpreting empirical parity violations and assessing market fragility. A measured does not necessarily indicate a market dominated by adverse selection in the classical sense (high proportion of informed traders). Instead, it may signal adaptive information processing by dealers— a behavioural response to inventory risk rather than a fundamental shift in trader composition.

From the Kyle regression alone, both scenarios produce similarly low values and appear observationally equivalent. However, the covariation remainder framework provides a diagnostic approach. Adaptive behaviour affects primarily through the time-varying response to order flow, while leaving relatively stable since it measures the long-run cointegrating relationship. In contrast, a genuine increase in informed trading would affect both coefficients by changing the fundamental market composition. If empirical data shows deviating dramatically from unity while remains stable and market thickness is high, the cause is likely state-dependent behaviour rather than structural features.

More broadly, the systematic interaction between adaptation intensity, market structure, and liquidity reveals limits on when parity-based measurements remain reliable. The IIP framework performs robustly in thin, competitive markets even under substantial adaptive behaviour. For example, produces under fragmented, thin market conditions (, ). This value of represents a twofold increase over baseline at typical inventory levels. The framework continues to provide meaningful diagnostics in this regime. However, in liquid monopolistic markets, the same adaptation intensity triggers collapse to , entering a regime where the parity index loses interpretive power. Even adaptation intensity of (40% of baseline at typical inventory levels) reduces below 0.2 in very liquid monopolistic markets. This suggests that empirical applications to centralized, liquid markets— precisely the venues with the best data quality —may be most vulnerable to measurement breakdown when dealers adapt their information extraction approaches based on inventory exposure.

The strong sensitivity to market thickness implies that this vulnerability increases rapidly rather than gradually as markets become more liquid. Markets crossing from moderate to high liquidity may experience sharp degradation in the reliability of parity-based inference. This finding suggests that the appropriate domain for applying the IIP framework empirically may be precisely the thin, fragmented markets that motivated its development— illiquid power futures and similar commodity markets —rather than the liquid financial markets where canonical microstructure theory was originally validated.

4.5. Diagnostic Analysis: Econometric Measurement Reliability

The preceding experiments demonstrate how market structure and behavioural parameters affect the measured parity index

. A methodological question remains: across what range of parameters can we trust these measurements? This section evaluates the reliability of our econometric protocol across all experiments conducted in

Section 4.1 to

Section 4.4.

We tracked two diagnostic metrics for each simulation run. The failure rate measures the proportion of simulations excluded from analysis. Runs were excluded for two distinct reasons: (1) failed cointegration tests, or (2) stability filter violations.

For cointegration failures, the Augmented Dickey-Fuller test failed to reject the null hypothesis of a unit root in the Ho-Stoll regression residuals at the 5% significance level. This indicates the absence of the stable long-run relationship between price deviation and inventory that the IIP framework predicts theoretically. Such failures suggest the market did not achieve the equilibrium dynamics required for valid parity measurement. For stability violations, inventory position or price deviation exhibited explosive growth indicating ill-conditioned dynamics rather than economically meaningful equilibrium behaviour. Together, these exclusions mean the failure rate serves as a diagnostic of market fragility: the proportion of parameter configurations unable to sustain the structural relationships necessary for IIP analysis.

The second metric, the coefficient of determination from the Kyle and Ho-Stoll regressions, were computed only for successful runs and measures the strength of the empirical relationships when they do exist.

These two metrics jointly distinguish between two qualitatively different scenarios. High failure rates accompanied by low values in successful runs would indicate weak or nonexistent economic relationships, suggesting the theoretical framework does not capture market dynamics. By contrast, high failure rates combined with strong values when successful indicate that the predicted relationships do exist and exhibit strong explanatory power, but the cointegration test lacks statistical power to detect them reliably in finite samples under certain parameter configurations. This latter scenario reflects the statistical limitations of testing for cointegration in short time series rather than inadequacy of the theoretical framework itself.

Table 2 presents reliability statistics across five market environments, aggregating data from all experiments conducted in

Section 4.1 to

Section 4.4. For each market, we report mean failure rates (averaged across all parameter configurations tested) and maximum failure rates (the worst-case configuration), along with mean

values computed from successful runs only.

The results reveal systematic patterns in measurement reliability. Failure rates increase monotonically with market thinness. In liquid markets , fewer than 2% of simulation runs fail on average, with maximum failure rates below 7% even in the most extreme parameter configurations. This rate rises progressively: illiquid markets average 7% failures with 21% maximum, thin markets reach 12% average with 30% maximum, and very thin markets show 20% average failures with 44% in the worst case. The measurement challenge intensifies precisely where economic theory predicts the weakest statistical signals due to sparse trading.

Examining failures across the parameter space reveals economically interpretable clustering. In the joint effects experiments, failures concentrate where (fragmented competition) and (approximately linear costs). When market makers face limited flow capture and linear inventory costs, their positions exhibit weaker mean reversion. This makes it harder for the ADF test to detect the long-run price-inventory relationship within periods. Increasing systematically reduces failure rates: as non-linear costs rise from 0 to , the cubic penalty induces stronger mean reversion, making the cointegrating relationship statistically easier to detect.

In the adaptive behaviour experiments, high values combined with liquid markets and monopolistic structure produce the highest failure rates within their parameter class. Although these remain below 15% on average. The time-varying response creates non-standard dynamics that challenge the ADF test’s assumptions, but the effect is secondary to the market thickness gradient.

The notable finding concerns the nature of failures across all experiments. Even in configurations with 40% failure rates (the maximum observed in very thin markets with and ), successful runs maintain high explanatory power. The minimum observed across all successful runs and all experiments exceeded 0.88 for Kyle regressions and 0.94 for Ho-Stoll regressions. Mean values remained above 0.88 even in the thinnest markets. This establishes that failures stemed from finite-sampling effects rather than fundamental weakness in the economic relationships. The theoretical connections between prices, inventory, and order flow remained empirically strong; the ADF test simply lacked power in extreme parameter regions.

Both regressions exhibit similar robustness. Across all parameter configurations tested, the failure rates for Kyle and Ho-Stoll regressions in the same simulation run are highly correlated (correlation coefficient ), meaning configurations that challenge one regression typically challenge both. However, Ho-Stoll regressions achieved systematically higher values (0.95–0.99 versus 0.88–0.97). This likely reflects that inventory, as a stock variable accumulated over time, contains less period-to-period noise than order flow, making the cointegrating relationship statistically cleaner to measure. Also, these high values empirically measures the tightness of the relationship, which is a non-linear process.

These diagnostics establish operational boundaries. The econometric protocol is highly reliable ( failure rates) when

Market thickness is moderate or high:

Competition is not severely fragmented:

Non-linear costs provide some mean reversion:

Adaptive behaviour is moderate:

The pattern of failures provides indirect validation of the theoretical framework while revealing substantive findings about market fragility. Failures occured precisely where economic theory predicts difficult measurement conditions: thin markets with weak mean reversion, limited competitive pressure, and time-varying behavioural responses. Yet the strong values in successful runs confirm that the fundamental IIP relationships remain empirically sound even in these extremes.

However, these measurement challenges are not artifacts of insufficient sampling that could be eliminated with more simulations. With 1000 simulations per configuration, estimation uncertainty (epistemic uncertainty about our estimators) has been decreased to very low levels through Rubin’s Rules pooling. What remains is genuine system variability (aleatory uncertainty inherent to the stochastic market dynamics). A 30% cointegration failure rate does not indicate our measurements were imprecise; it indicates that 30% of the time, this particular market structure genuinely fails to produce a detectable long-run relationship within realistic sample lengths. This is a property of the market, not a limitation of the statistical methodology.

This distinction has important implications for empirical applications. Real power futures markets operate with finite participants generating finite transaction samples. Empirical researchers analyzing 500-1000 periods of data from thin markets will encounter exactly the same cointegration test failures we observe in our simulations—not because they need more data, but because the market structure itself produces inconsistent dynamics. The variance in measured across simulation simulations under identical parameters quantifies how unpredictable and fragile these market configurations actually are. Wide confidence intervals in certain regimes are not measurement noise to be eliminated; they are substantive findings about market instability.

The IIP framework is structurally valid: the theoretical relationships hold when they can be measured. However, our diagnostics reveal that certain market structures (thin, fragmented, with weak mean reversion) are fundamentally difficult to characterize with finite-sample econometrics, not due to methodological inadequacy but due to the intrinsic instability of those market configurations. This represents a genuine limitation on the reliability of market maker programs operating in such environments, and empirical researchers should interpret measurement difficulties in real thin markets as potential signals of structural fragility rather than merely technical challenges to be overcome with larger datasets.

5. Results: IIP Global Sensitivity Analysis and the Connection to Real Power Markets

The experiments in

Section 4.1–

Section 4.4 validated the theoretical mechanisms underlying the IIP framework through controlled parameter sweeps. While these experiments successfully isolated individual effects—– competition, non-linear costs, and adaptive behaviour –—they explored narrow slices of parameter space designed for theoretical clarity rather than empirical realism. Each experiment varied at most two parameters simultaneously, holding others at calibrated baseline values chosen for analytical convenience rather than to represent actual power market conditions.

This section bridges from theoretical validation to practical application by asking: how does the IIP framework behave across the full range of parameter combinations that characterize real thin power futures markets? Unlike liquid financial markets where canonical microstructure models were developed and validated, power futures exhibit distinctive structural features: small numbers of active participants (limited M), sparse hedging activity (low ), fragmented liquidity provision (reduced ), physical delivery constraints inducing strong inventory aversion (elevated ), and adaptive behaviour by large players with market power (potential for adaptive responses ). The question is not whether these features matter in isolation—– the preceding experiments established that they do –—but rather which combinations dominate real market dynamics and which parameters exert the strongest influence when all vary simultaneously within physically plausible bounds.

We addressed these questions through a Global Sensitivity Analysis (GSA) using variance-based Sobol indices. This approach decomposes the variance in measured across the six-dimensional parameter space , with parameter ranges calibrated to reflect the structural characteristics of illiquid power futures markets rather than abstract theoretical benchmarks. The analysis serves three objectives relevant if the IIP framework were applied to operating markets:

Parameter attribution: If a market operator or regulator measures in an operating power futures market, which of the six structural parameters is most likely driving the deviation from classical parity? Should policy interventions target competition (adjusting through market maker exclusivity), cost structures (influencing through capital requirements or position limits), or market composition (affecting M and through incentive programs)?

Regime prevalence: What percentage of parameter combinations representative of thin power markets fall into each of the four market regimes defined in

Section 2.3? Are Dysfunctional markets (

) rare pathological cases, or do they represent a substantial fraction of plausible configurations that regulators should anticipate?

Interaction complexity: Are observed market outcomes in power futures primarily determined by individual structural features (e.g., number of participants), or by complex nonlinear interactions among multiple parameters (e.g., competition level affecting how non-linear costs influence dynamics)? If interactions dominate, isolated policy interventions may prove ineffective.

The GSA methodology addresses these questions by exploring the full parameter space defined by physically realistic bounds for thin power markets, weighted equally across all combinations that produce dimensionally-consistent regression coefficients, as discussed in

Section 2.7. This provides a representative picture of how the IIP framework behaves under conditions matching actual illiquid commodity markets rather than the idealized scenarios of canonical theory.

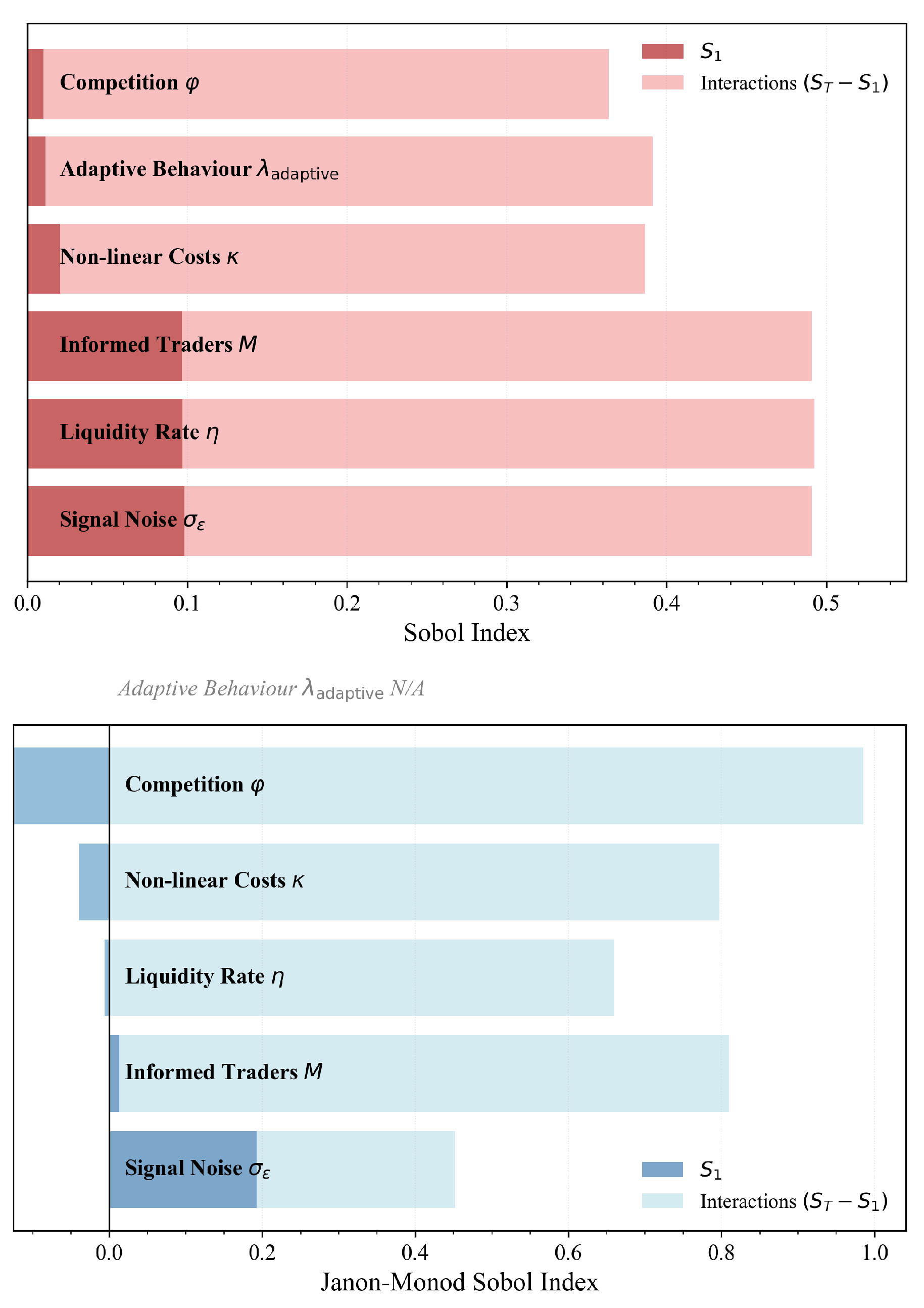

5.1. Sobol Sensitivity Analysis

Variance-based sensitivity analysis decomposes the total variance of an output

Y—– in our case, the Parity Index

—–into contributions from individual inputs

and their interactions. For a model

, the Sobol decomposition expresses the variance as

where

represents the variance contribution of parameter

i alone, and

represents the interaction between parameters

i and

j. This decomposition defines two key sensitivity indices for each parameter. The first-order index:

measures the direct effect of

on

Y, averaging over all other parameters. It answers the question “If uncertainty in only one parameter could be eliminated through better market data or institutional knowledge, which would reduce uncertainty in

the most?” The total-effect index

measures the total contribution of

including all interactions, where

denotes all parameters except

i. It answers the question “What fraction of variance in

would remain if

were the only uncertain parameter?”

The difference quantifies the importance of interactions involving parameter i. A large difference indicates that the parameter’s influence depends strongly on the values of other parameters, a hallmark of complex, nonlinear systems where isolated interventions may produce unexpected outcomes.

We employed the Saltelli sampling scheme, which generates a quasi-random sample of size that enables simultaneous estimation of all first-order and total-effect indices with controlled statistical error. For our six-parameter model , this requires evaluations of the full ABM simulation. This approach is computationally expensive but provides model-independent sensitivity estimates without requiring linearity or additivity assumptions—essential properties when analyzing the inherently nonlinear dynamics of thin markets with adaptive agents.

5.2. Parameter Space Definition: Two-Stage Discovery Process

Defining the parameter space for Global Sensitivity Analysis in thin power markets presents a fundamental challenge: the plausible ranges for structural parameters

were constrained by dimensional consistency requirements established in

Section 2.7. Market configurations must produce regression coefficients within physically realistic bounds (

and

) to represent actual power futures market conditions. However, these constraints create complex, nonlinear feasibility boundaries in the six-dimensional parameter space that cannot be determined analytically. We therefore employed a two-stage empirical discovery process.

5.2.1. Stage 1: Grid Search for Feasible Bounds

We began with deliberately wide parameter ranges based on order-of-magnitude dimensional analysis, spanning from extreme thin markets to moderately liquid conditions.

Table 3 presents these initial ranges, which were intentionally generous to avoid excluding potentially relevant regions a priori.

We conducted a systematic grid search with 5 points per dimension, yielding

configurations. For each configuration, we implemented the Equilibrium-Aware Monte Carlo Simulation (E-MCS) protocol: (1) recalibrate behavioural parameters

to maintain the balanced-risk condition

under the scaling relationships from

Section 3, (2) execute

independent ABM simulations with

and

periods. Thus, this grid search consisted of

simulations in total. (3) apply the full econometric protocol (Kyle and Ho-Stoll regressions with cointegration testing), and (4) average measured outputs across valid simulations.

The grid search revealed severe dimensional constraints: only 1,953 configurations (12.5%) produced regression coefficients within the physically plausible bounds. Configurations outside these bounds corresponded to either hyper-liquid markets where price impact becomes negligible () or pathologically illiquid markets where single trades move prices by hundreds of ticks : neither representing realistic power market conditions. The plausibility failures clustered in economically interpretable regions: very high values (modeling unrealistically active hedging), very low M combined with high (producing extreme noise-trader dominance), and extreme values (creating adaptive behaviour so aggressive it violated the Kyle model’s implicit assumptions).

From the plausible subset, we extracted refined parameter bounds by identifying the minimum and maximum values along each dimension that produced dimensionally consistent coefficients, adding a 10% margin to allow Sobol sampling to explore the boundaries.

Table 3 also presents these empirically-discovered ranges, which define the physically realistic parameter space for thin power markets.

5.2.2. Stage 2: Sobol Variance Decomposition on Refined Space