Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and Description of Short Sales Policies

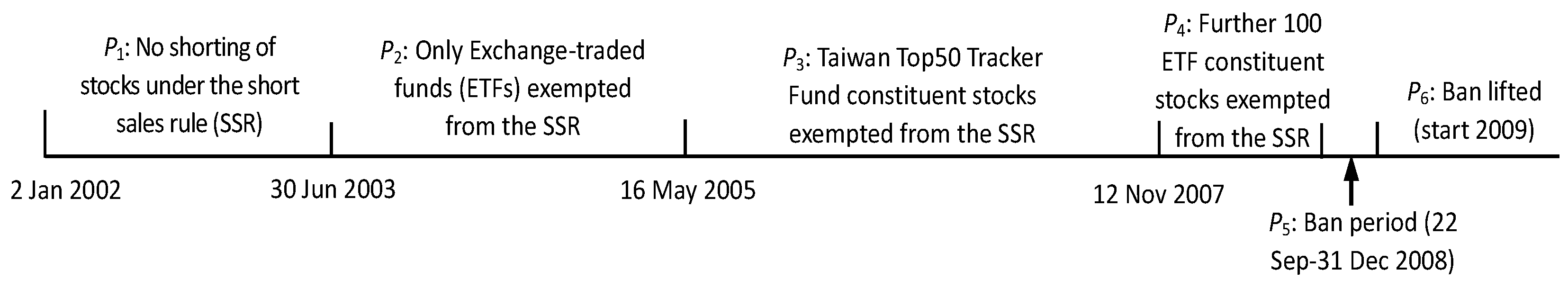

2.1. SSCs Policy Changes

2.2. SSCs Proxies

2.3. The Implied Index Price and Equilibrium Deviations

2.4. Other Variables and Control Variables

3. Hypothesis Development and Empirical Design

3.1. Improved Speed of Price Adjustment

3.2. Price Stabilization under SSCs: A Counterfactual Analysis

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Rapid Upward and Sluggish Downward Adjustment

4.2. How is Market Efficiency Improved after Lifting SSCs?

4.3. Counterfactual Analysis of a Zero-SSC Scenario

4.4. Tighter Constraints, Higher Risk and Price Fluctuations

5. Robustness Checks

5.1. Further Evidence on High Short Demand Transactions

5.2. The Elevated Risk Due to Stronger SSCs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Appendix A. Counterfactual Simulation Analysis with a Stationary Bootstrap

| 1 | See, for example, Diamond and Verrecchia (1987), Hong et al. (2000), D’Avolio (2002), Bris et al. (2007), Charoenrook and Daouk (2005), Saffi and Sigurdsson (2011), Lim (2011), Yeh and Chen (2014), Deng et al. (2020), and Khan et al. (2019). |

| 2 | Examples include Danielsen and Sorescu (2001), Jones and Lamont (2002), Ofek and Richardson (2003), Chang et al. (2007) and Diether et al. (2009a). Later works confirm the market inefficiency of SSCs include Deng et al. (2023), Li et al. (2022), Cai et al. (2019), Patatoukas et al. (2022), and Liu and Wang (2019). |

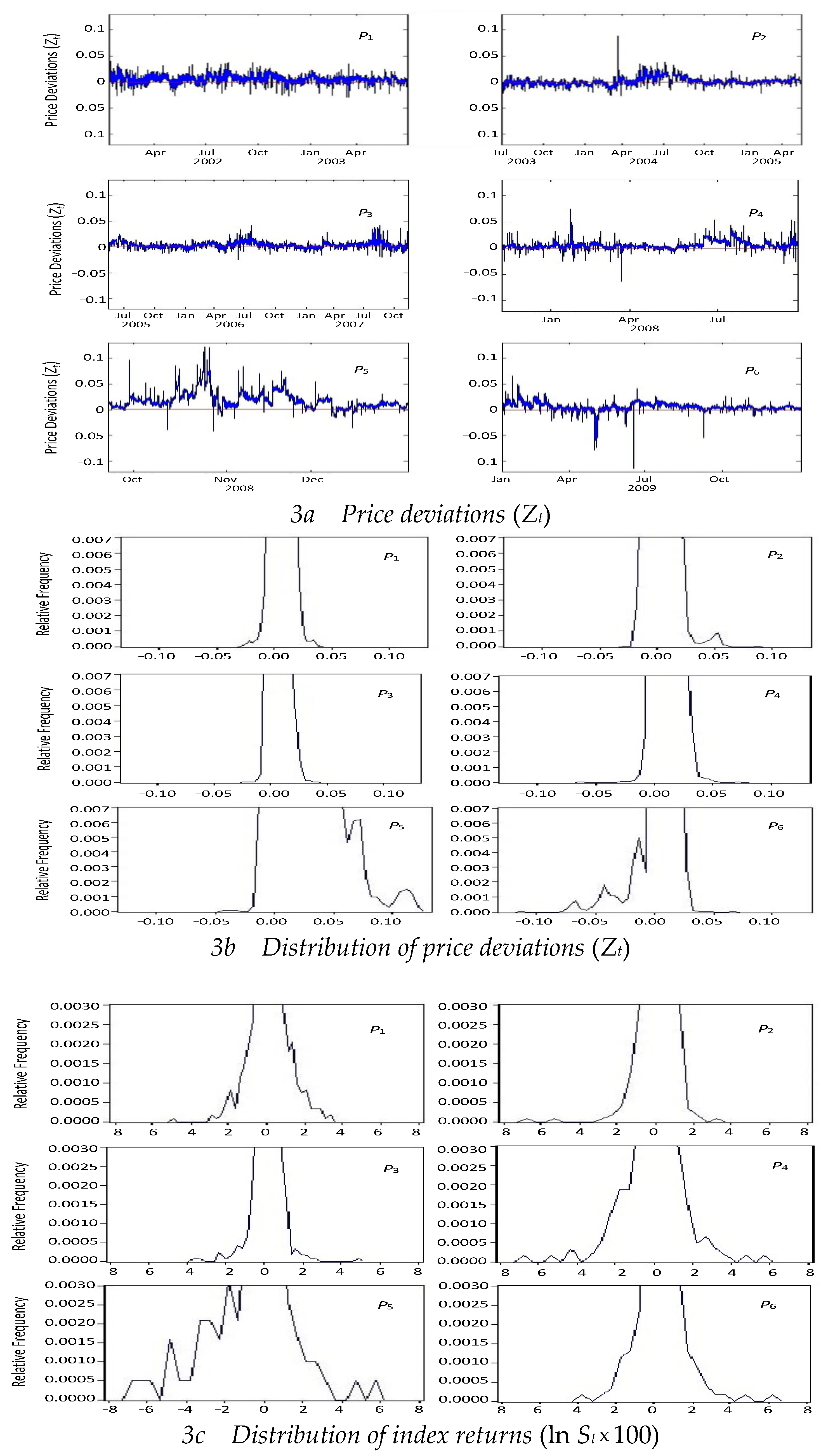

| 3 | Examples include Miller (1997), Jones and Lamont (2002), Bris et al. (2007), Ofek et al. (2004), Boulton and Braga-Alves (2010) and Autore et al. (2011). |

| 4 | See, for example, Patell and Wolfson (1984), Jennings and Starks (1986), Diamond and Verrecchia (1987), Senchack and Starks (1993), Figlewski and Webb (1993), Danielsen and Sorescu (2001), Battalio and Schultz (2011), Grundy et al. (2012), Beber and Pagano (2013), Chen et al. (2015) and Li et al. (2019). |

| 5 | See Chiou et al. (2007) among many others. |

| 6 | As such, the SSC in terms of the up-tick rule is stricter in Taiwan than in the U.S. since the up-tick rule in U.S. stock exchanges requires that the short selling prices not be lower than the best current ask price. |

| 7 | These stocks, among the largest and most actively traded stocks listed on the TWSE, are considered less vulnerable to potential price manipulations. |

| 8 | Although SSC were relaxed after the end of 2008, the basis for calculating securities borrowing and lending balances has been restricted since July 22, 2009. Hence the weakest SSC are in p4 rather than in p6. |

| 9 | For example, some use the lower lending supply or higher loan fees (Saffi and Sigurdsson, 2011), lower rebate rates (D’Avolio, 2002; Geczy et al., 2002; Bargeron et al., 2011), negative rebate rate spread (Ofek et al., 2004) and low daily short interest (Diether et al., 2009a). Some proxies for relaxed short-sales restrictions via the presence of stock options (Danielsen and Sorescu, 2001; Charoenrook and Daouk, 2005; Phillips, 2011), the introduction of stock futures (Danielsen et al., 2009), the availability of short-selling (Chen and Rhee, 2010), or the percentage of proceeds available to short-sellers (Kamara and Miller, 1995). |

| 10 | Geczy et al. (2002) use one-year rebate data (November 1998 to October 1999) provided by a US custodian bank to study borrowing costs for IPOs, whilst Ofek et al. (2004) rely on the rebate rate from one of the largest dealer-brokers. |

| 11 | The average loan fee for the 12,621 firms from 26 countries was computed by ten custodians. |

| 12 | There are advantages in deriving the theoretical index price from put-call parity. First, since the TAIFEX options are European-style options, we can avoid the potential effects of early exercise risk on mispricing errors and thus the ‘per minute’ synchronously matched data rules out the potential problem of non-synchronicity. Secondly, the options market has fewer transaction limitations than the stock market and, as shown by Miller (1977), investors prefer to trade in a less limited market where the asset prices immediately reflect new information. |

| 13 | For example, given the previous trading day’s closing price of 5,678, we round the number to 5,700. We then collect option contracts with strike prices ranging from 5,400 to 6,000 to derive their corresponding implied indices. Each series is matched with the same strike price and same maturity. We then average the seven implied index prices over moneyness to obtain the final theoretical index price (StO ) for time t. |

| 14 | Diether et al. (2009a) found that short sellers covered their positions in 5.4 days on the NYSE and 4.4 days on the NASDAQ with daily short interest rather than monthly data. |

| 15 | Tentative explanations for price deviations from extant studies include: the presence of transaction costs (Brooks and Garrett, 2002; Ofek et al., 2004; Ackert and Tian, 2001), non-synchronous trading (Easton, 1994), market illiquidity (Ofek et al., 2004; Roll et al., 2007; Kamara and Miller, 1995), idiosyncratic risk (Duan et al., 2010), the microstructure effect (Bakshi et al., 2000), analyst disagreement (Sadka and Scherbina, 2007) and SSC costs (Ofek et al., 2004; Ackert and Tian, 2001). |

| 16 | For instance, in their attempts to avoid such spurious findings, when examining the ways in which stock pricing efficiency and return distributions were affected by SSC, Saffi and Sigurdsson (2011) provided controls for firm capitalization, liquidity and transaction costs. The liquidity and transaction cost variables included total share turnover, incidences of zero weekly returns, the annual average of the weekly quoted bid-ask spread and the Datastream free float measure. |

| 17 | The evidence suggests that SSC tend to suppress the information content of the stock price (see Miller, 1977; Diamond and Verrecchia, 1987; Duffie et al., 2002 and Autore et al., 2011), and, indeed, several other studies provide similar support by showing that the SSC result in overvaluations and subsequent reduced returns (Jones and Lamont, 2002; Bris et al., 2007; Ofek et al., 2004, Boulton and Braga-Alves, 2010, and Coculescu and Jeanblanc, 2019). Saffi and Sigurdsson (2011) found price efficiency increases with smaller SSC (see also Jiang et al., 2001; Jones and Lamont, 2002; Bris et al., 2007; Ofek et al., 2004; Boulton and Braga-Alves, 2010 and Autore et al., 2011, Zhao, 2016, Wu et al., 2018, Ebrahimnejad & Hoseinzade, 2019, and Ramachandran and Tayal, 2021), while they find no evidence of the relaxation of SSC leading to price fluctuations or extreme negative returns. |

| 18 | Chen and Rhee (2010) is one exception. |

| 19 | Under perfect market conditions, if the index price is too high relative to the fundamental value (i.e., ), then arbitrageurs will engage in short selling or sell the spot commodity to mitigate the discrepancy, whereas if the index price is undervalued (), then the opposite trading strategies will occur. Both actions will ensure adjustment towards the fundamental price (). |

| 20 | For each SSC policy regime, we average over the number of minutes the price persists to be overpriced (underpriced) until it reverts to its fundamental price across days. The analyzed results are available upon request. |

| 21 | Since the explicit transaction costs of investors for sales (purchases) of stocks in the market are 0.4425% (0.1425%), we use 0.4425% (–0.1425%) as the upper (lower) bound of the transaction costs when defining the violations in Taiwan. |

| 22 | The TECM model has been used to describe many economic phenomena, such as government intervention in exchange rates at times when the market price diverges too far from the fair price (where an exchange rate is almost a random walk in an inside band). |

| 23 | In analyzing the non-linear dynamic relationship between S&P 500 futures and the cash indices attributable to non-zero transaction costs, Dwyer et al. (1996) showed that the estimated threshold value (c) was similar to real world transaction costs. |

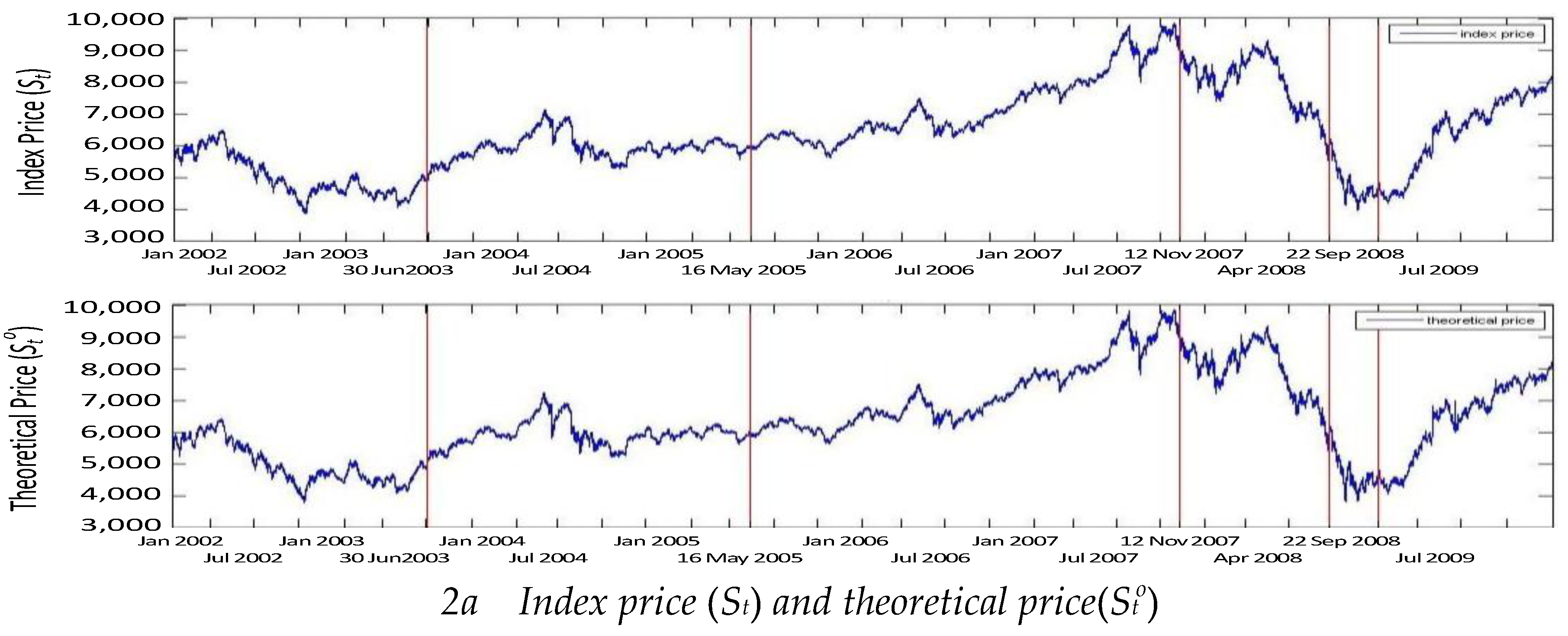

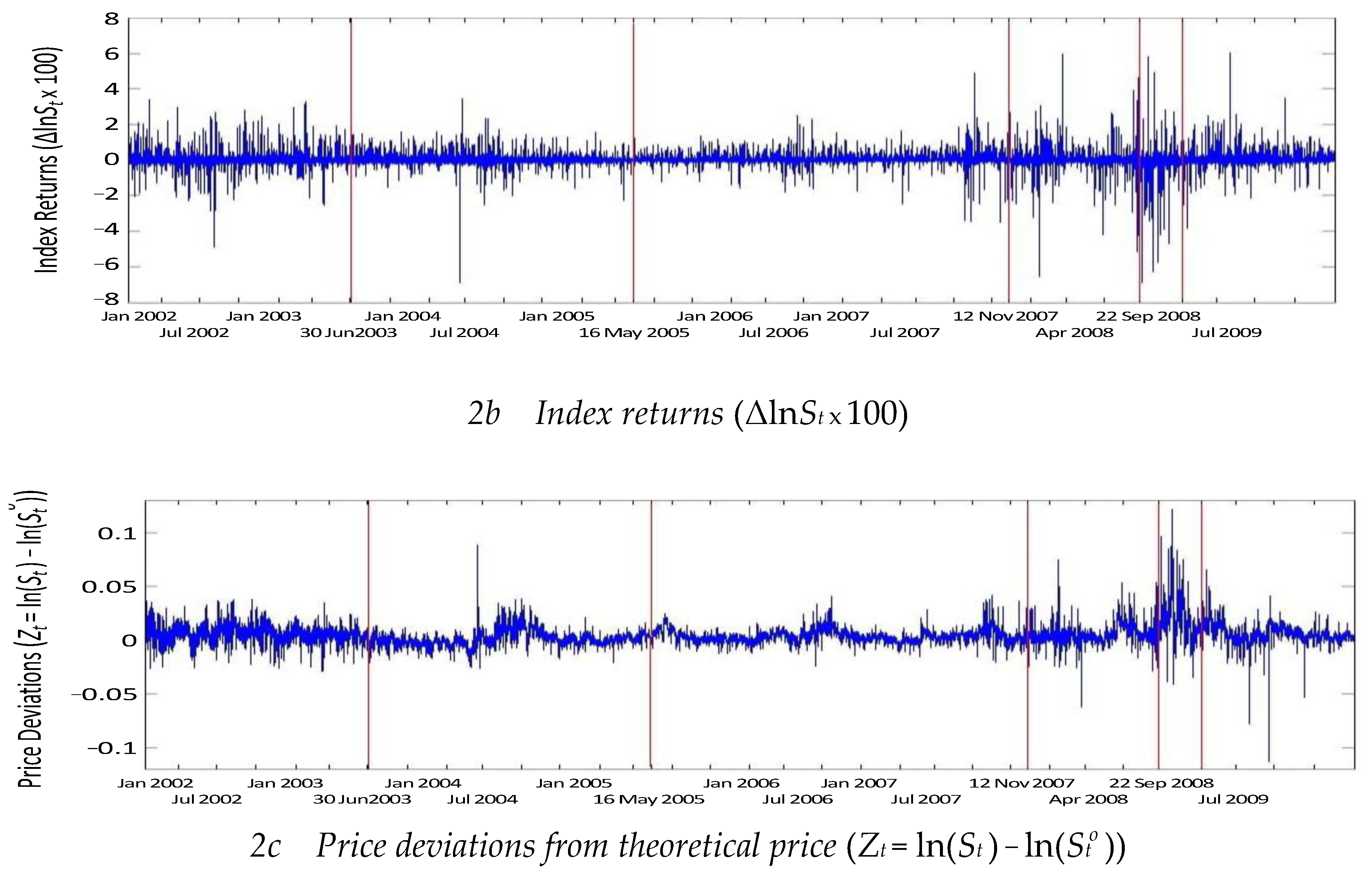

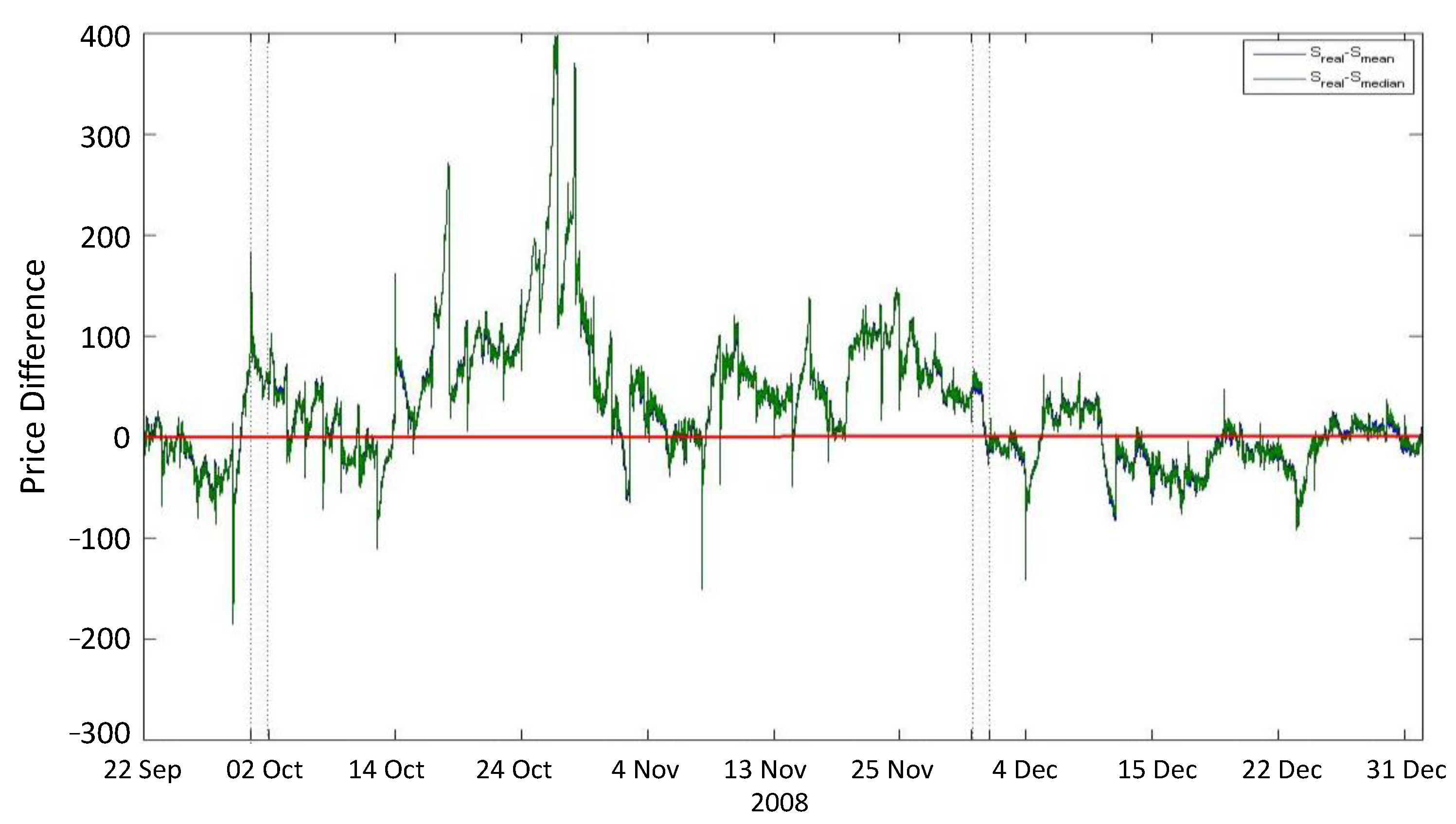

| 24 | Under the strictest constraints, a decline in market liquidity is found for several measures, including trading frequency, trading volume and trading dollars per minute. Decreasing daily turnover and increasing risk are shown in(see Table 2). The relative high frequency of the price deviations during periods of tighter SSC is clearly discernible from Figures 2c and 3a. In Figure 3, there are clearly more occurrences of positive deviations than negative deviations, particularly during p5 (a period of tight constraints). Secondly, consistent with the overvaluation effect (Miller, 1977), the constraints have hindered information incorporation, ultimately resulting in overvaluations and low subsequent returns. |

| 25 | See Charoenrook and Daouk (2005), Bris et al. (2007) and Phillips (2011). |

| 26 | The thresholds are clearly different under the various policy changes: –0.0003 and 0.0051 for ; –0.0015 and 0 for ; –0.0001 and 0.0001 for ; –0.0002 and 0.0139 for ; 0.0030 and 0.0270 for ; and –0.0001 and 0.0006 for , whilst the threshold lags are: in ; in; and in . The estimation procedure mainly follows Enders and Siklos (2001) and the results are available upon request. |

| 27 | Martens et al. (1998) showed that, based upon the price derived from the cost-of-carry relationship, the impacts of mispricing errors were significantly larger when the S&P 500 index was overpriced. |

| 28 | Examples include Diamond and Rajan (2010), Veronesi and Zingales (2010) and Hoshi and Kashyap (2010). |

| 29 | See, for example, Charoenrook and Daouk (2005), Bris et al. (2007) and Saffi and Sigurdsson (2011). Saffi and Sigurdsson (2011) found that the total risk and downside risk increased significantly for stocks with higher loan fees or low loan supply. Furthermore, from their analysis of 46 securities markets, Bris et al. (2007) also found that the distribution of market returns under SSC had less negative skewness, and they could find no evidence of the availability of short sales potentially giving rise to a crisis. |

| 30 | The index return distribution characteristics are measured by the and variables in Table 2, respectively referring to the daily skewness and excess kurtosis of the index returns. Average daily excess kurtosis for our TAIEX intraday data is 121 in and 96 in , whilst daily skewness is −3.01 in and 1.06 in . The negative skewness indicates that the left tail is heavier than the right tail. |

| 31 | The equations of Models (3), (4), and (5) in Table 5 are skipped to save space and can be provided upon request. |

| 32 | he VIX index is computed by weighted average index options with different strike prices and moneyness following the CBOE methodology. In general, the higher the VIX index, the more severe the expected future volatility of the stock price index among the derivatives investors. Since VIX describes changes in overall market sentiment, it is also known as the investor ‘fear index’ or ‘fear gauge’. |

References

- Ackert, L.F., Tian. Efficiency in index options markets and trading in stock baskets. Journal of Banking and Finance 2001, 25, 1607–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autore, D.A., Billingsley, R.S., Kovacs, T., 2011. The 2008 short sale ban: liquidity, dispersion of opinion, and the cross-section of returns of US financial stocks. Journal of Banking & Finance 35, 2252-2262. [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, G., Cao, C. Chen, Z., 2000, Do call prices and the underlying stock always move in the same direction? Review of Financial Studies 13, 549–584. [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.M., Lee, Y.T., Liu, Y.J., Odean, T., 2004. Who gains from trade? Evidence from Taiwan. Working paper, University of California.

- Bargeron, L., Kulchania, M., Thomas, S., 2011. Accelerated share repurchases. Journal of Financial Economics 101, 69-89. [CrossRef]

- Battalio, R., Schultz, P., 2011. Regulatory uncertainty and market liquidity: The 2008 short sale ban’s impact on equity option markets. Journal of Finance 66, 2013-2053. [CrossRef]

- Beber, A., Pagano, M., 2013. Short-selling bans around the world: Evidence from the 2007-09 crisis. Journal of Finance 68, 343-381. [CrossRef]

- Bris, A., Goetzmann W. N., and Zhu, N., 2007. Efficiency and the bear: Short sales and markets around the world. Journal of Finance 62, 1029-1079. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C. and Garrett, I., 2002. Can we explain the dynamics of UK FTSE 100 stock and stock index futures markets? Applied Financial Economics 12, 25–31. [CrossRef]

- Boulton, T. J., Braga-Alves, M. V., 2010. The skinny on the 2008 naked short-sale restrictions. Journal of Financial Markets 13, 397–421. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J., Ko, C. Y., Li, Y., & Xia, L. (2019). Hide and Seek: Uninformed Traders and the Short-sales Constraints. Annals of Economics and Finance, 20(1), 319-356.

- Chang, E.C., Cheng, W., Yu, Y., 2007. Short-sales constraints and price discovery: evidence from the Hong Kong market. Journal of Finance 62, 2097–2121. [CrossRef]

- Charoenrook, A., Daouk, H., 2005. A study of market-wide short-selling restrictions, working paper.

- Chen, S.-S., Chen, Y., Chou, R. K., 2015. Short-Sale Constraints and Option Trading: Evidence from Reg SHO. Working Paper. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. X., Rhee, S. G., 2010. Short sales and speed of price adjustment: Evidence from the Hong Kong stock market. Journal of Banking & Finance 34, 471-483. [CrossRef]

- Chiou, R. W., Hsieh, L.G., and Lin, Y.Y., 2007. The Impact of Execution Delay on the Profitability of Put-Call-Futures Trading Strategies – Evidence from Taiwan. Journal of Futures Markets 27, 361-385. [CrossRef]

- Coculescu, D., & Jeanblanc, M. (2019). Some no-arbitrage rules under short-sales constraints, and applications to converging asset prices. Finance and Stochastics, 23(2), 397-421. [CrossRef]

- Connolly, R. A., 1989. An examination of the robustness of the weekend effect. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 24, 133–169. [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, B., Sorescu, S. M., 2001. Why do option introductions depress stock prices? An empirical study of diminishing short sales constraints. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 36, 451–484.

- Danielsen, B.R., Van Ness, R.A., Warr, R. S., 2009. Single stock futures as a substitute for short sales: evidence from microstructure data. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 36, 1273-1293. [CrossRef]

- Deng, X., Gao, L., & Kim, J. B. (2020). Short-sale constraints and stock price crash risk: Causal evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Corporate Finance, 60, 101498. [CrossRef]

- Deng, X., Gupta, V. K., Lipson, M. L., & Mortal, S. (2023). Short-sale constraints and corporate investment. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 58(6), 2489–2521. [CrossRef]

- D’Avolio, G., 2002. The market for borrowing stock. Journal of Financial Economics 66, 271–306. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D. W., Rajan, R. G., 2010. Fear of Fire Sales and the Credit Freeze. Working Paper, University of Chicago.

- Diamond, D., Verrecchia, R., 1987. Constraints on short-selling and asset price adjustment to private information. Journal of Financial Economics 18, 277-311. [CrossRef]

- Diether, K.B., Lee, K.H., and Werner, I.M., 2009a. Short-sale strategies and return predictability, The Review of Financial Studies 22, 575-606. [CrossRef]

- Diether, K. B., Lee, K. H., Werner, I. M., 2009b. It’s SHO time! Short-sale price tests and market quality. Journal of Finance 64, 37-73. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y., Hu, G., Mclean, R. D., 2010. Costly arbitrage and idiosyncratic risk: Evidence from short sellers. Journal of Financial Intermediation 19, 564-579. [CrossRef]

- Duffie, D., Garleanu, N., Pedersen, L. H., 2002. Securities lending, shorting, pricing. Journal of Financial Economics 66, 307–339. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer Jr, G.P., Locke, P., Yu, W., 1996. Index arbitrage and nonlinear dynamics between the S&P 500 futures and cash. Review of Financial Studies 9, 301–332. [CrossRef]

- Easton, S. A., 1994. Non-simultaneity and apparent option mispricing in tests of Put-call parity. Australian J. Journal of Management, 19. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimnejad, A., & Hoseinzade, S. (2019). Short-sale constraints and stock price informativeness. Global Finance Journal, 40, 28-34. [CrossRef]

- Enders, W., Siklos, P. L., 2001. Cointegration and threshold adjustment. American Statistical Association 19, 166-176. [CrossRef]

- Figlewski, S., Webb, G.P., 1993. Options, short sales, market completeness. Journal of Finance 48, 761-777. [CrossRef]

- Franklin, A., Gale, D., 1991. Arbitrage, Short Sales, Financial Innovation, Econometrica 59, pages 1041-1068. [CrossRef]

- Fung, J.K.W., Jiang, L., 1999. Restrictions on Short Selling and Spot-Futures Dynamics. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 26, 227-248. [CrossRef]

- Geczy, C. C., Musto, D. K., Reed, A. V., 2002. Stocks are special too: an analysis of the equity lending market. Journal of Financial Economics 66, 241–269. [CrossRef]

- Grundy, B. D., Lim, B., Verwijmeren, P., 2012. Do option markets undo restrictions on short sales? Evidence from the 2008 short-sale ban. Journal of Financial Economics 106, 331-348Hong, H., Lim, T., Stein, J.C., 2000. Bad news travels slowly: size, analyst coverage, the profitability of momentum strategies. Journal of Finance 55, 265–295. [CrossRef]

- Hong, H., Stein, J.C., 2003. Differences of opinion, short-sales constraints, market crashes. Review of Financial Studies 16, 487-525.

- Hoshi, T., Kashyap, A. K., 2010. Will the U.S. Bank Recapitalization Succeed? Eight Lessons from Japan. Journal of Financial Economics 97, 398–417. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.H., Hsu, Y.C., Kuan, C.M., 2010. Testing the predictive ability of technical analysis using a new stepwise test without data snooping bias. Journal of Empirical Finance 17, 471–484. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, R.H., Starks, L.T., 1986. Earnings announcements, stock price adjustment, the existence of options markets. Journal of Finance 41, 143–161. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., Fung, J.K.W., Cheng, L.T.W., 2001. The lead-lag relation between spot and futures market under different short-selling regimes. The Financial Review 38, 63-88. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M., Lamont, O. A., 2002. Short-sale constraints and stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics 66, 207–239. [CrossRef]

- Kamara, A., Miller, T. W., 1995. Daily and Intradaily Tests of European Put-Call Parity. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 30, 519-539. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. S. R., Kato, H. K., & Bremer, M. (2019). Short sales constraints and stock returns: How do the regulations fare? Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 54, 101049. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Li, Z., Lin, B., & Xu, X. (2019). The effect of short sale constraints on analyst forecast quality: Evidence from a natural experiment in China. Economic Modelling, 81, 338-347. [CrossRef]

- Li, R., Li, C., & Yuan, J. (2022). Short-sale constraints and cross-predictability: Evidence from Chinese market. International Review of Economics & Finance, 80, 166-176. [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.Y., 2011. Short-sale constraints and price bubbles. Journal of Banking & Finance 35, 2443-2453. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., & Wang, Y. (2019). Asset pricing implications of short-sale constraints in imperfectly competitive markets. Management Science, 65(9), 4422-4439. [CrossRef]

- Martens M., Kofman, P., Vorst, T.C.F., 1998. A threshold error-correction model for intraday futures and index reurns. Journal of Applied Econometrics 13, 245-263. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E., 1977. Risk, uncertainty, divergence of opinion. Journal of Finance 32, 1151–1168. [CrossRef]

- Ofek, E., Richardson, M., 2003. DotCom mania: The rise and fall of internet stock prices. Journal of Finance 58, 1113-1137. [CrossRef]

- Ofek, E., Richardson, M., Whitelaw, R. F., 2004. Limited arbitrage and short sales restrictions: evidence from the options markets. Journal of Financial Economics 74, 305–342. [CrossRef]

- Patatoukas, P. N., Sloan, R. G., & Wang, A. Y. (2022). Valuation uncertainty and short-sales constraints: Evidence from the IPO aftermarket. Management Science, 68(1), 608-634. [CrossRef]

- Patell, J.M., Wolfson, M.A., 1984. The intraday speed of adjustment of stock prices to earnings and dividend announcements. Journal of Financial Economics 13, 223-252. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B., 2011. Options, Short-sale constraints and market efficiency: A new perspective. Journal of Banking & Finance 35, 430-442. [CrossRef]

- Politis, D.N., Romano, J.P., 1994. The stationary bootstrap. Journal of the American Statistical Association 89, 1303–1313. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, L. S., & Tayal, J. (2021). Mispricing, short-sale constraints, and the cross-section of option returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 141(1), 297-321. [CrossRef]

- Roll, R., Schwartz, E., Subrahmanyam, A., 2007. Liquidity and the Law of One Price: The Case of the Futures-Cash Basis. Journal of Finance 62, 2201-2234. [CrossRef]

- Sadka, R., Scherbina, A., 2007. Analyst Disagreement, Mispricing, Liquidity. Journal of Finance 62, 2367–2403. [CrossRef]

- Saffi, P.A.C., Sigurdsson, K., 2011. Price efficiency and short selling. The Review of Financial Studies 24, 821-852. [CrossRef]

- Senchack, A. J., Starks, L. T., 1993. Short-Sale Restrictions and Market Reaction to Short-Interest Announcements. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 28, 177-194. [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, A., Vishny, R.W., 1997. The Limits of Arbitrage. Journal of Finance 52, 35-55. [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, P., Zingales, L., 2010. Paulson's Gift. Journal of Financial Economics 97, 339-368. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., Luo, H., & Fu, Z. (2018). Positive Return–Volatility Correlation and Short Sale Constraints: Evidence from the Chinese Market. Asia‐Pacific Journal of Financial Studies, 47(1), 132-157. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-H., Chen, L.-C., 2014. Stabilizing the Market with Short Sale Constraint? New Evidence from Price Jump Activities. Finance Research Letters 11, 238-246. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K. M. (2016). Short sale constraints and information-driven short selling: evidence on NASDAQ. Applied Economics, 48(23), 2113–2124. [CrossRef]

| Measures | Statistics | Critical Values | First Difference | |

| t-Statistic | Critical Values | |||

| Panel A: Augmented Dickey-Fuller Test Statisticsb | ||||

| –1.38 | –3.43019 | –212.365 | –2.86136 | |

| –1.60 | –2.86136 | –287.005 | –2.86136 | |

| Panel B: Cointegration Testc | ||||

| Trace Test | 1180.2 | 25.87211 | – | – |

| Max-eigenvalue Test | 1176.0 | 19.38704 | – | – |

| Variables | Full Sample | Sub-period Mean Values | |||||||||||

| Median | S.E. | Min | Max | Mean | |||||||||

| 6212 | 1307 | 3846 | 6421 | 9860 | 5024 | 5931 | 7239 | 8006 | 4790 | 6463 | |||

| 6174 | 1308 | 3774 | 6393 | 9848 | 4995 | 5922 | 7211 | 7963 | 4705 | 6428 | |||

| 0.0000 | 82 | –6905 | 0.0721 | 6047 | –0.1304 | 0.1612 | 0.2412 | –0.7021 | –1.3651 | 0.8505 | |||

| 0.0000 | 107 | –12810 | 0.0731 | 12744 | –0.1310 | 0.1673 | 0.2400 | –0.7111 | –1.4137 | 0.8723 | |||

| 0.0036 | 0.0074 | –0.1132 | 0.0047 | 0.1218 | 0.0058 | 0.0016 | 0.0039 | 0.0056 | 0.0183 | 0.0058 | |||

| No. of Obs. | 539,019 | 99186 | 126557 | 168020 | 57994 | 19241 | 68021 | ||||||

| Market liquidity | |||||||||||||

| Num_Trades | 2289 | 2807 | 0 | 152241 | 2862 | 2434 | 2467 | 2745 | 3507 | 2690 | 4011 | ||

| Num_Shares | 11477 | 17737 | 0 | 1063416 | 14877 | 12965 | 14971 | 14411 | 16936 | 12759 | 17485 | ||

| TDollart –1 | 281 | 434 | 0 | 35933 | 368 | 301 | 332 | 394 | 450 | 223 | 438 | ||

| Daily_Turnover | 0.0061 | 0.0030 | 0.0020 | 0.0223 | 0.0069 | 0.0082 | 0.0078 | 0.0059 | 0.0057 | 0.0048 | 0.0075 | ||

| Daily_Turnover/MV | 0.0062 | 0.0025 | 0.0021 | 0.0193 | 0.0068 | 0.0083 | 0.0070 | 0.0061 | 0.0061 | 0.0050 | 0.0074 | ||

| No. of Obs. | 1,989 | 366 | 467 | 620 | 214 | 71 | 251 | ||||||

| Market condition | |||||||||||||

| Realized_Variance*100 | 0.0101 | 0.0358 | 0.0009 | 0.4814 | 0.0186 | 0.0240 | 0.0158 | 0.0080 | 0.0272 | 0.0757 | 0.0188 | ||

| 0.0005 | 0.0021 | –0.0070 | 0.0060 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.0006 | 0.0008 | –0.0012 | –0.0053 | 0.0014 | |||

| 0.0148 | 0.0053 | 0.0068 | 0.0270 | 0.0148 | 0.0181 | 0.0127 | 0.0100 | 0.0200 | 0.0242 | 0.0187 | |||

| –0.1374 | 0.6337 | –1.9077 | 2.2563 | –0.1706 | 0.1864 | –0.1878 | -0.4167 | 0.1668 | 0.3709 | –0.4920 | |||

| 0.8466 | 2.4404 | –0.3963 | 16.2872 | 1.7216 | 0.3252 | 1.4754 | 2.4858 | 2.4188 | 0.2950 | 2.1374 | |||

| Models | (1)(i)b | (1)(ii)b | (2)(i)b | (2)(ii)b | ||||||||||||||||

| Variables | ΔlnSt | ΔlnSto | ΔlnSt | ΔlnSto | ΔlnSt | ΔlnSto | ΔlnSt | ΔlnSto | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | –0.0000 | 0.0000 | –0.0000 | † | 0.0000 | –0.0000 | † | –0.0000 | –0.0000 | † | –0.0000 | |||||||||

| αj+ | –0.0011 | † | 0.0012 | † | –0.0016 | † | 0.0014 | † | – | – | – | – | ||||||||

| αjbtw | –0.0007 | –0.0021 | † | –0.0017 | † | –0.0014 | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| αj– | –0.0100 | † | 0.0094 | † | –0.0105 | † | 0.0097 | † | – | – | – | – | ||||||||

| – | – | – | – | 0.0041 | † | 0.0070 | † | 0.0041 | † | 0.0073 | † | |||||||||

| – | – | – | – | –0.0055 | 0.0511 | † | –0.0049 | 0.0505 | † | |||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | –0.0002 | 0.0020 | † | –0.0012 | 0.0021 | † | |||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | –0.0143 | † | –0.0001 | –0.0157 | † | 0.0001 | |||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | 0.0008 | 0.0009 | 0.0001 | 0.0007 | |||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | –0.0401 | † | –0.0038 | –0.0437 | † | –0.0033 | |||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | –0.0051 | † | 0.0008 | –0.0050 | † | 0.0009 | |||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | –0.2013 | † | –0.0152 | –0.2020 | † | –0.0151 | |||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | –0.0018 | † | –0.0008 | –0.0018 | † | –0.0006 | |||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | –0.0743 | † | –0.0022 | –0.0742 | † | –0.0025 | |||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | 0.0009 | 0.0017 | 0.0002 | 0.0019 | |||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | 0.0009 | 0.0123 | † | –0.0009 | 0.0124 | † | |||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | 0.0009 | –0.0052 | 0.0011 | –0.0043 | |||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | –0.0136 | –0.0045 | –0.0148 | –0.0051 | |||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | 0.0014 | 0.0748 | –0.0001 | 0.0732 | |||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | 0.0017 | –0.0013 | 0.0023 | –0.0005 | |||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | 0.0009 | –0.0009 | 0.0008 | –0.0002 | |||||||||||||

| – | – | – | – | –0.0007 | 0.0971 | –0.0335 | 0.0811 | |||||||||||||

| TDollart–1 | – | – | –0.0000 | † | 0.0000 | – | – | –0.0000 | 0.0000 | |||||||||||

| – | – | –0.0006 | 0.0015 | – | – | 0.0008 | 0.0010 | |||||||||||||

| – | – | –0.0000 | † | 0.0000 | – | – | –0.0000 | † | –0.0000 | |||||||||||

| – | – | 0.0014 | † | –0.0004 | – | – | 0.0009 | –0.0002 | ||||||||||||

| – | – | 0.0000 | –0.0000 | – | – | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |||||||||||||

| Overnight | – | – | 0.0002 | † | 0.0006 | † | – | – | 0.0002 | † | 0.0006 | † | ||||||||

| Open | – | – | 0.0001 | † | 0.0000 | † | – | – | 0.0001 | † | –0.0000 | † | ||||||||

| Close | – | – | –0.0000 | 0.0000 | – | – | –0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||||||||

| AIC | –22.6123 | – | –22.6152 | – | –22.6218 | – | –22.6249 | – | ||||||||||||

| –0.0089*** – | –0.0089*** – | – | – | – | – | |||||||||||||||

| – | – | – | –0.0033*** – | –0.0032*** – | ||||||||||||||||

| Periods | No. of Obs. | Skew | Kurt | Extre. Freq– | Extre. Freq+ | *100 | *100 |

| 366 | 0.9126 | 56.04 | 0.0054 | 0.0063 | 0.0240 | 0.0106 | |

| 467 | 0.8683 | 32.62 | 0.0092 | 0.0111 | 0.0158 | 0.0079 | |

| 620 | 2.6429 | 75.12 | 0.0049 | 0.0058 | 0.0080 | 0.0034 | |

| 214 | 1.0573 | 96.01 | 0.0031 | 0.0037 | 0.0272 | 0.0141 | |

| 71 | –3.0075 | 120.54 | 0.0032 | 0.0034 | 0.0757 | 0.0530 | |

| 251 | 2.8151 | 75.75 | 0.0073 | 0.0071 | 0.0188 | 0.0064 | |

| p4 − p5b | 4.0648*** | –24.54*** | –0.0003 | 0.0003 | –0.0484*** | –0.0389*** | |

| MODEL | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |||||||

| Dep. Var. | |||||||||||

| Intercept | -0.0000 | 0.0000 | Intercept | -0.0000 | 0.0000 | Intercept | -0.0000 | 0.0000 | Intercept | -0.0000 | -0.0000 |

| -0.0055† | 0.0011 | -0.0035† | -0.0004 | -0.0026 | 0.0055† | -0.0032† | 0.0026 | ||||

| -0.0262† | 0.0174† | -0.0023 | -0.0009 | 0.0129† | 0.0495† | ||||||

| -0.0051† | -0.0025 | -0.0028 | -0.0025 | ||||||||

| -0.0083† | -0.0002 | 0.0007 | 0.0042 | ||||||||

| -0.0038† | 0.0028 | -0.0035† | -0.0029 | ||||||||

| -0.0148† | 0.0059 | -0.0573† | 0.0060 | ||||||||

| -0.0050† | -0.0007 | ||||||||||

| -0.3309† | 0.0228 | ||||||||||

| -0.0010 | 0.0025 | ||||||||||

| -0.2231† | 0.0016 | ||||||||||

| -0.0051 | -0.0042 | ||||||||||

| -0.0326† | 0.0241† | ||||||||||

| -0.0028† | 0.0028† | -0.0025† | 0.0026† | -0.0027† | 0.0029† | -0.0024† | 0.0026† | ||||

| -0.0000† | 0.0000 | -0.0000† | 0.0000 | -0.0000† | 0.0000 | -0.0000† | 0.0000 | ||||

| -0.0007 | 0.0028 | -0.0005 | 0.0027 | -0.0007 | 0.0028 | 0.0003 | 0.0029 | ||||

| 0.0017† | -0.0009 | 0.0015† | -0.0008 | 0.0016† | -0.0011 | 0.0012† | -0.0007 | ||||

| -0.0000† | -0.0000 | -0.0000† | -0.0000 | -0.0000† | -0.0000 | -0.0000† | -0.0000 | ||||

| -0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||

| overnight | 0.0001† | 0.0006† | 0.0002† | 0.0006† | 0.0001† | 0.0006† | 0.0002† | 0.0006† | |||

| open | 0.0001† | -0.0000† | 0.0001† | -0.0000† | 0.0001† | -0.0000† | 0.0001† | -0.0000† | |||

| close | -0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0000 | 0.0000 | |||

| AIC | -22.6144 | -22.6151 | -22.6146 | -22.6202 | |||||||

| Asymmetry Test | |||||||||||

| -0.0226*** | |||||||||||

| Different Policy Test | |||||||||||

| -0.0045*** | |||||||||||

| Downward Adjustment Test | |||||||||||

| -0.0039*** | |||||||||||

| Dependent Variable | No. of Obs. | Interceptb | b | b | VIXb | |||||

| Realized_Variance*100 | 768 | –0.0343 | * | 0.0011 | 0.0162 | ** | –0.0111 | * | 0.0020 | * |

| Downside_Risk*100 | 768 | –0.0182 | * | 0.0000 | 0.0220 | * | –0.0091 | * | 0.0011 | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).