1. Introduction

Swaps are widely used financial instruments that allow two or more parties to exchange value flows either at predetermined intervals or contingent upon specific events [

1,

2]. A subset of these instruments, known as subordinated risk swaps, enables firms to transfer idiosyncratic risks, such as managerial or event-related uncertainties, in exchange for structured cash flows [

3,

4].

In this study, we introduce the concept of an Acquisition Risk Swap (ARS), a specialized form of subordinated risk swap that serves as a hedging mechanism for acquiring agents (“acquirers”). The primary function of an ARS is to mitigate the risk of being unable to procure a critical capability at an uncertain future date. A pertinent example of this is in defense acquisitions, where supply chain disruptions, such as the well-documented shortages of 155mm artillery shells, pose significant operational risks [

5,

6].

The adoption of ARS by capability users presents several advantages, which can be broadly categorized into three interrelated dimensions: risk reduction, efficiency, and transparency [

7,

8].

Risk reduction – ARS provides acquirers with enhanced certainty regarding future contingencies, allowing them to hedge against unfavorable procurement conditions. This, in turn, enables better financial planning and cost reduction in the event that the hedged risk materializes.

Efficiency – By employing ARS, the three key stakeholders—the acquirer, the ARS writer, and the capability creator—can focus on their respective comparative advantages. Instead of the acquirer handling risk estimation, financial structuring, and capability production independently, these functions can be distributed to specialized entities, improving overall efficiency [

1,

9].

Transparency – Like other financial markets, ARS pricing mechanisms provide valuable information regarding supply-demand dynamics. The observed market prices for ARS can signal the estimated probability of a future event occurring and the perceived value of the associated capability. This transparency aids strategic decision-making but may also inadvertently reveal sensitive intent to competitors or adversaries [

3,

4]. For instance, price fluctuations in ARS markets could be interpreted as indicators of potential military strategies or corporate actions, making discretion an important consideration.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: In

Section 2, we outline the fundamental ARS contract structure and derive explicit pricing models under various assumptions.

Section 3 explores potential market structures that could facilitate ARS pricing and exchange.

Section 4 presents empirical simulations of ARS price distributions under different modeling assumptions, while

Section 5 discusses possible extensions and generalizations of our work.

2. Asset Definition and Pricing

We outline the asset definition and pricing in discrete time; an extension to continuous time should be straightforward. An agent that needs a capability during a future time interval holds the ARS, paying a coupon of , where (the ARS may never be exercised, in which case the ARS is a perpetual obligation). When the capability is needed – the a priori unknown future time t – the holder of the ARS ceases to pay the coupon and is delivered a capability that has value .

We solve for the coupon rate by finding such a value that makes the cash flows equivalent at time zero. Defining the valuation where and r is the risk free rate, the coupon payments are those values that satisfy . With the simplifying assumption that , the coupon payment is or under the additional assumption that the value of the acquired capability is equal at all times , Here, m is a random variable, as it depends on the random time interval over which the capability is required. Modeling the time interval with the joint distribution , we take the coupon payment as the expected value of m, .

More generally, the interest rate

and the valuation of the capability

may vary over time. Interest rates may be correlated with the existence or nature of the conditioning event; for example, conflict could lead to shortages of basic necessities such as food and fuel, raising inflation, which could cause a central bank to raise interest rates [

10]. The value of one capability immediately after the inception of a conflict could be very high but decrease as time progresses, while another capability could increase in importance as a conflict progresses. With these considerations in mind, a more general valuation of the ARS is

, where analogously

.

3. Market Structure

We undertake a brief discussion of naive and more nuanced market structures for ARS and discuss methods by which price discovery for ARS is likely to occur. We leave in-depth analysis of possible market structures for future work.

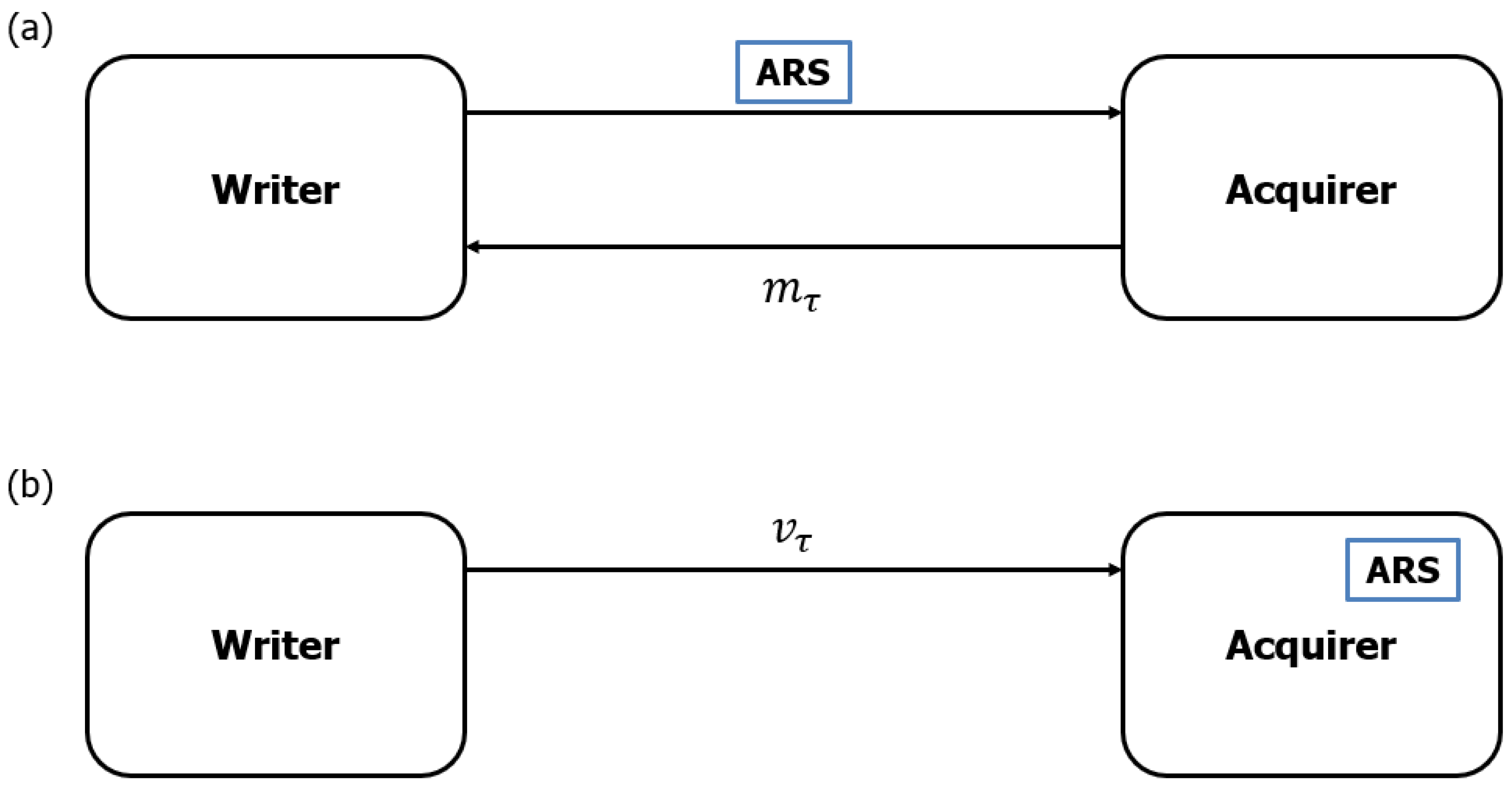

The mechanics of an ARS contract are specified in

Section 2; a graphical depiction of these simple mechanics is displayed in

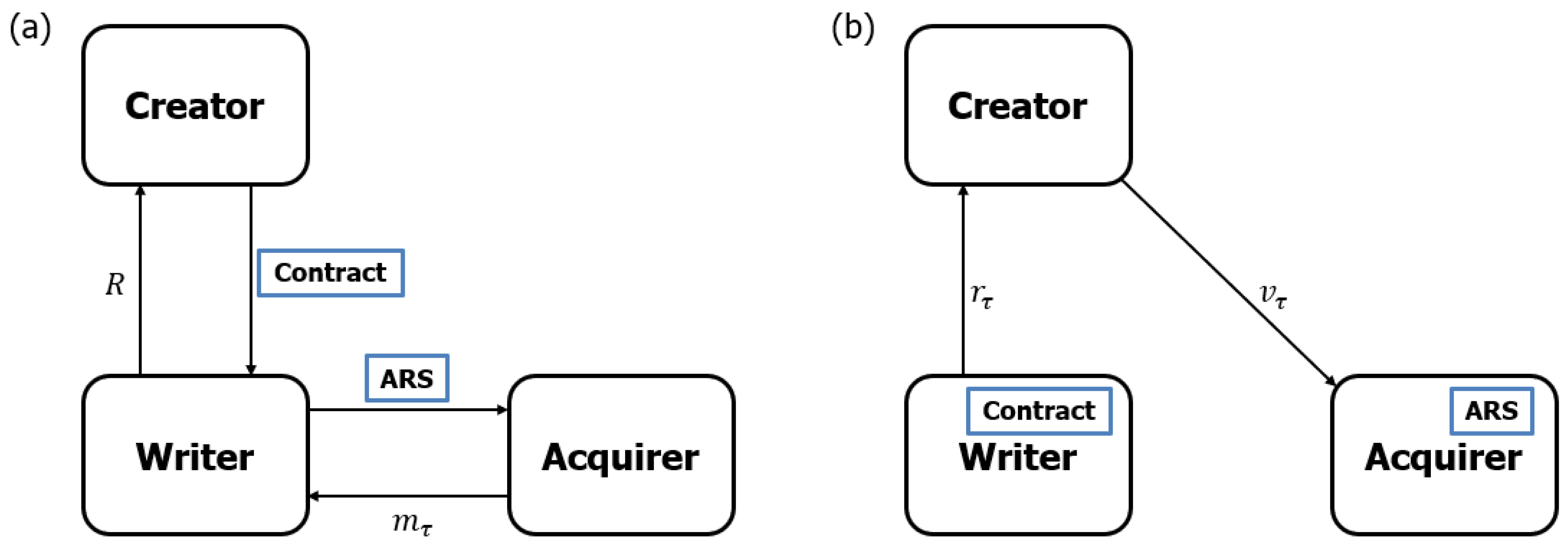

Figure 1, in which panel (a) refers to before the ARS is exercised by the holder and panel (b) describes the structure after it is exercised. We display a notional, more-developed market structure in

Figure 2. In this example, the writer sells the ARS to the acquirer and hedges the risk it takes on in doing so by contracting with a creator of the capability (e.g., in the 155mm shell example, a manufacturer capable of rapidly retooling to create shell casings), paying that creator a fixed-fee retainer of

R at the initial time period. If the triggering event occurs, the writer pays a further stream of cashflows

(which are possibly zero) to the creator; the creator creates the capability and delivers it to the acquirer.

A more complex market structure, such as the one outlined in the previous paragraph and displayed in

Figure 2, has at least two benefits over the naive market structure displayed in

Figure 1:

- 1.

Decoupling of financial valuation from physical delivery. In general, there is no reason to believe that a firm with the expertise valuing an ARS – i.e., a firm that believes it can accurately and precisely estimate the probability distribution of the window over which a capability would be needed – would also have the expertise required to rapidly create that capability. For example, a geopolitical risk firm that believes it can assess the likelihood and duration of a conflict between two nations is probably not the same firm that can rapidly manufacture a large quantity of shell casings.

- 2.

Incentive to participate in the market due to speculation and innovation. The writer of an ARS might believe that the conditioning event will occur in the very distant future or has a very low probability of occurrence at all and therefore believe that the negotiated stream of income represents a low-risk profit opportunity. The creator of the capability, on the other hand, may have no opinion about the likelihood of the event at all but assesses it can very rapidly create the required capability with almost no advance warning and at a cost exactly equal to in perpetuity; in this case, the retaining fee R is essentially a risk-free profit for the creator.

How might the price of an ARS be discovered? As with other swaps, this would likely depend on the liquidity of the underlying capability that the acquirer is hedging and the relative market power of the acquirer(s) compared with the writer(s). In the monopsonistic case, when the capability is relatively liquid or even standardized, it seems likely that the acquirer would run an English reverse auction (or a similar commonly practiced single reverse auction). When the capability is less liquid, the contracted price could be negotiated over the counter between the writer(s) and the acquirer. We explore other mechanisms for price discovery in

Section 5.

4. Simulation

We outline some empirical statistical properties of the ARS under simple statistical models and an example market structure.

1

4.1. Statistics of Price Distributions

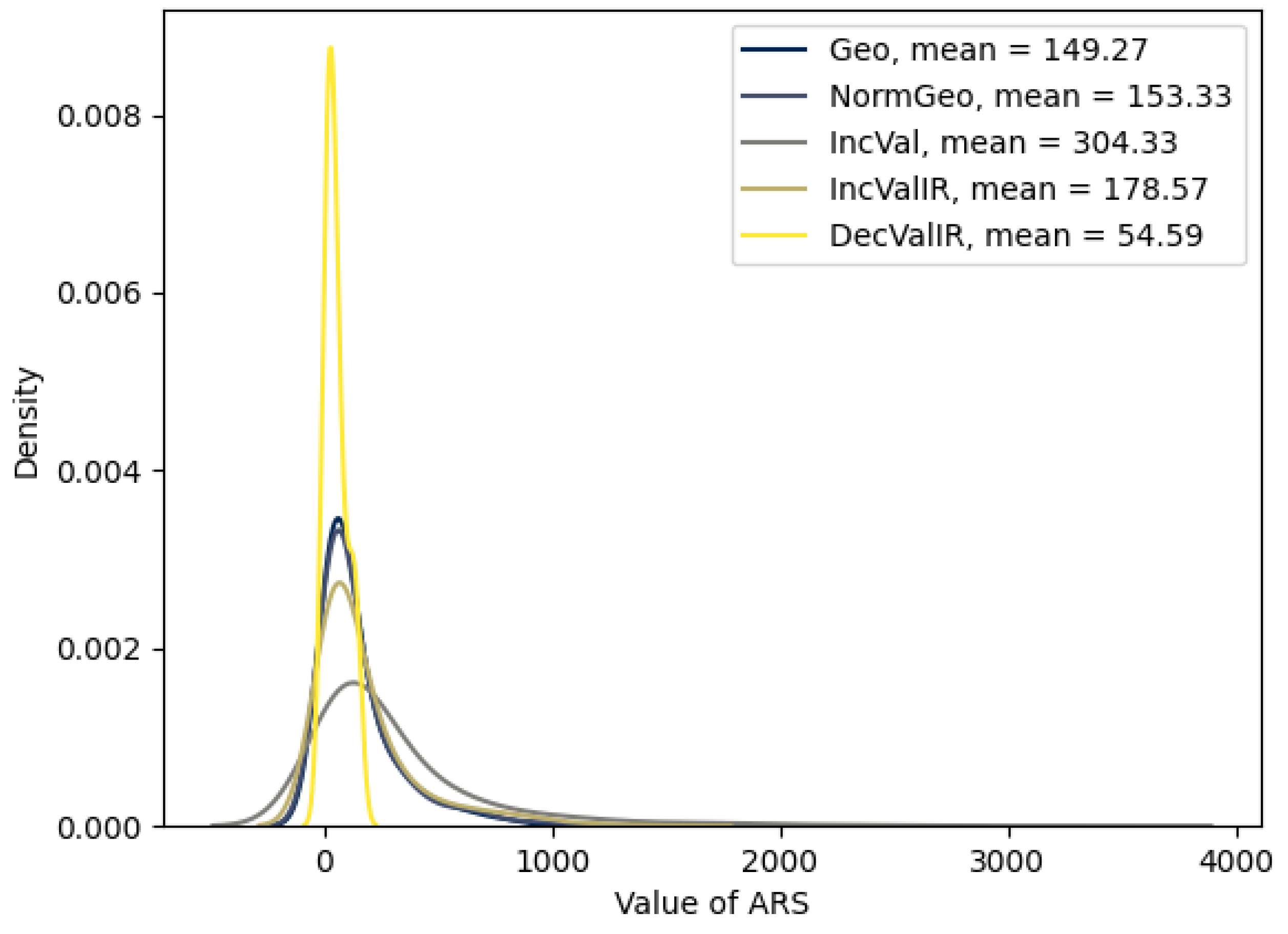

We briefly compare empirical distributions of ARS price under different generative models of event time interval , value v, and interest rate r. We emphasize that these distributions are rough indicators of behavior only as the price of ARS will depend crucially on the estimation of value and event time interval probability that will very likely be highly context-dependent. Specializations to specific operational contexts are not in scope for this work.

Each pricing example uses the naive event probability distribution

, where

. Each example begins with a notional risk-free rate of 4%, capability value of

(abstract numeraire), and

. Empirical density functions of price are displayed in

Figure 3.

We describe scenarios in terms of changes to the default parameters listed above.

(Geo) – no changes to the specifications listed above.

(NormGeo) – . By Jensen’s inequality, the linearity of the identity function, and the conditional independence of v and , the price distribution in this scenario is theoretically identical to that of Geo.

(IncVal) – , where , modeling an on-average-precipitous increase in the value of the capability for the duration of the event.

(IncValIR) – simultaneously (a) the value of the capability deterministically increases from v to asymptotically approach a new steady state according to and (b) the interest rate moves from stochastic fluctuation about the steady state to the higher steady-state . Stochastic fluctuation is modeled via a single-factor short-rate model, , where and is the equilibrium rate and .

(DecValIR) – simultaneously (a) the value of the capability deterministically decreases according to and (b) the interest rate fluctuates according to the same model presented in IncValIR.

In these examples, ARS price distributions generally have excess mass in their right tails, meaning that there is a substantial tail risk that the actual value of the cash flows to the right of the event start date has a higher value than what would be suggested by the expected value pricing formulae presented earlier. We will discuss hedging strategies in

Section 5.

4.2. Market Structure

We construct a simulation of a simple form of the market structure presented in

Figure 2. There is a single acquirer who has a mean reservation price

, where

is computed under the distribution

where

and the estimates

and

are publicly known. The acquirer’s observed price of the ARS is given by

. There are

writers of ARS who compete to sell a single ARS to the acquirer via an English reverse auction. They have heterogeneous beliefs about the start and stop probability of the event, modeling it as

and

conditioned to lie in

. There are

manufacturers who can create the capability desired by the acquirer. Each manufacturer has a private reserve value

they are required to accept a contract for manufacture at an unknown future date, and each has a marginal production cost of

. Before time

, the acquirer conducts an English reverse auction to purchase the ARS from a writer. Then, the successful writer conducts an English reverse auction at a reserve price with the manufacturers. If this market clears, meaning that the writer who wins the auction has a price for the ARS that is less than or equal to the acquirer’s maximum willingness to pay and, similarly, that the manufacturer who wins the auction has a reserve price for manufacturing that is less than or equal to the writer’s maximum willingness to pay, the model advances in discrete time, with contract mechanics as specified in

Section 2.

2

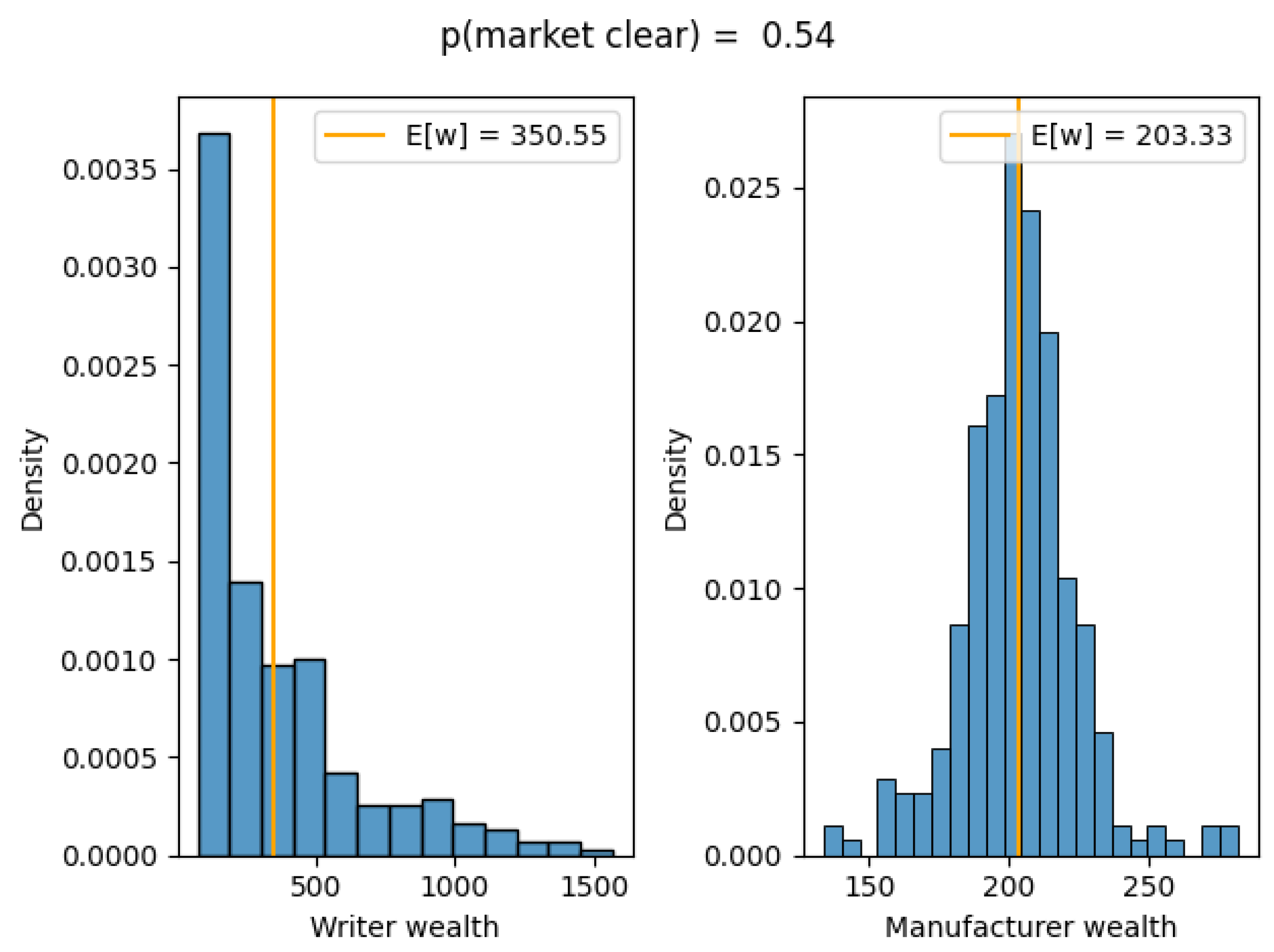

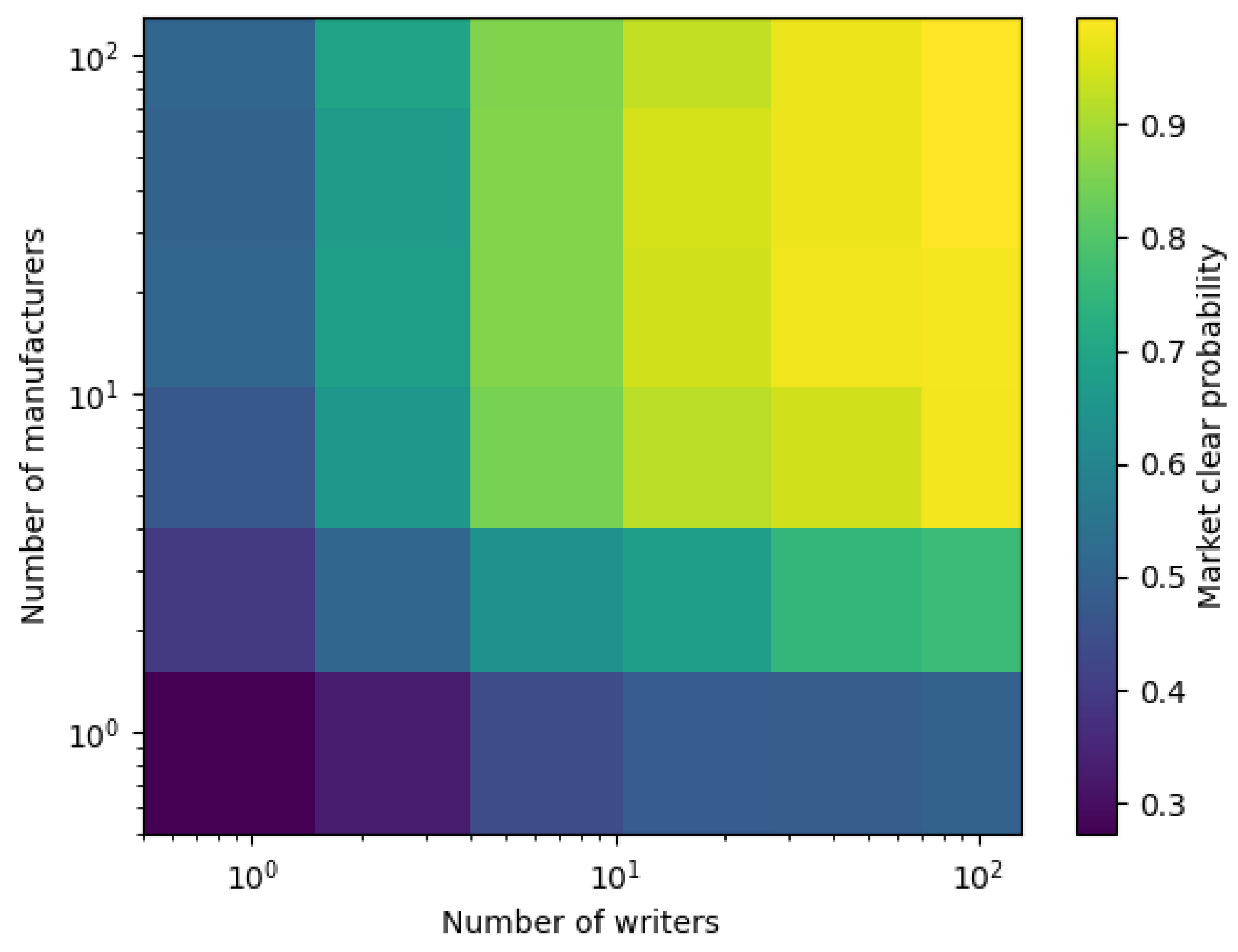

We display wealth distributions of successfully matched writers and manufacturers in

Figure 4 and market clearing probability as a function of number of writers and manufacturers in

Figure 5. Monte Carlo simulations of this market structure suggest that the market will likely clear even with relatively low participation. For example, even with only two writers and two manufacturers participating in the marketplace, the market clears more than half of the time. (Under this model, a market with only one potential writer and 10 manufacturers clears almost half of the time – 44% – while an ARS market with a healthy five writers and 20 manufacturers clears a full 92% of the time!)

5. Generalizations and Structural Considerations

We constructed a pricing and market structure framework for acquisition risk swaps (ARS), a type of subordinated risk swap that eliminates the risk that an agent faces from needing to acquire a costly capability during an unknown future time interval. However, we made multiple simplifying assumptions that, in our judgment, would be eliminated in a commercial implementation of an ARS marketplace. We outline several unaddressed shortcomings of the present work, each of which could be grounds for further research.

Event probability distribution – probably the most glaring assumption we made for each of our simulations was that of events starting and stopping according to independent Bernoulli trials. The pricing formulae described earlier do not depend on such an assumption. In reality, the probability of events for which an ARS would be appropriate to hedge, such as conflict or large-scale business transformation, would have a rich structure conditioned on complex representations of the world state (e.g., geopolitical factors or the competitive structure of a firm’s target marketplace). Event times might also exhibit a nontrivial correlation structure (e.g., if a conflict starts sooner than expected, it could also end sooner than expected). Such dependence could be modeled using an appropriate copula structure.

Valuation of the capability – we have assumed that the acquirer can place a monetary value on the capability it seeks to acquire and that the writer can assess what that monetary value is. In practice, each of these statements may not be true. A lower bound to the value of an additional unit of a capability could be the sum of the marginal costs of each of its components (including labor and properly amortized operational expenditures), but this bound may be very weak. Estimating the acquirer’s value function would probably be a nontrivial task for both the writer and the acquirer but could be facilitated by advances in reinforcement learning [

11]. The acquirer may face the risk that it systematically understates its true valuation of the capability (e.g., by valuing it at only the sum of its marginal costs of production plus a constant value that does not incorporate the discounted benefits of future use) and consequently faces lower market supply than expected.

3

Interest rate dynamics – interest rates may co-vary substantially with the probability of the conditioning event. For example, interest rates and the capability to be acquired may both be affected by geopolitical dynamics.

Market structure – we have outlined one market structure, in addition to the naive one defined by the mechanics of the ARS contract, that could create additional market efficiencies in terms of hedging risk and decoupling firms’ comparative advantages. However, there are likely other market structures, depending on the operational context, that could incentivize participation by different firm types (e.g., different production capacities, risk preferences, or investing time horizons). In some applications, markets could need to place constraints on writers and creators (e.g., based on capitalization or security requirements).

Price discovery – the nature of the acquired capability would likely dictate the method by which its price is discovered. Non-exquisite, low-marginal cost capabilities (e.g., commodity drone parts) could be created by many parties, leading to very liquid markets; other capabilities (e.g., bespoke defense manufacturing) might exhibit complexity such that the market for capability creators, at the time of the ARS’s inception, is much less liquid.

The price signal created by the ARS could facilitate capital investment in that market if the timescale on which the ARS writers’ market expects the capability to be needed, , is compatible with the required investing timeline (e.g., the timeline required to build a manufacturing facility).

6. Conclusion

This study explored the interplay between market structures and asset pricing through a simulation-based approach, focusing on Acquisition Risk Swaps (ARS). Our findings suggest that ARS pricing is influenced by various factors, including event probability distributions, interest rate fluctuations, and the valuation of capabilities. The simulations indicate that ARS price distributions generally exhibit right-skewed behavior, highlighting the presence of tail risks in certain scenarios. Additionally, our Monte Carlo simulations demonstrate that market clearing is achievable even with a relatively low number of participating writers and manufacturers.

A structured market framework that decouples financial valuation from physical capability creation appears to enhance efficiency, reduce risk, and promote market participation. This approach aligns with existing financial risk management strategies, where specialization plays a crucial role in improving liquidity and stability [

3]. Future research should refine event probability distributions using advanced modeling techniques such as copulas [

10] and reinforcement learning [

11] to better estimate the valuation of capabilities. Furthermore, exploring alternative market structures could provide insights into optimizing ARS price discovery mechanisms and improving financial risk mitigation strategies [

9].

By addressing these areas, future studies can enhance the robustness of ARS pricing models and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of risk management in financial markets.

References

- Hull, J.C. Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives, 10th ed.; Pearson, 2022.

- Duffie, D. Swap Rates and Credit Risk; 1999.

- McNeil, A.; Frey, R.; Embrechts, P. Quantitative Risk Management: Concepts, Techniques, and Tools; Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Geman, H. Commodities and Commodity Derivatives: Modelling and Pricing for Agriculturals, Metals, and Energy; Wiley, 2005.

- Investigates, R. Ukraine Crisis and Artillery Shortages, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/ukraine-crisis-artillery.

- Tang, C.S. Robust Strategies for Mitigating Supply Chain Disruptions. International Journal of Logistics Research 2006, 9, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.C.; White, A. The Pricing of Options on Assets with Stochastic Volatilities. Journal of Finance 1987, 42, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasserman, P. Monte Carlo Methods in Financial Engineering; Springer, 2004.

- Harris, L. Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners; Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Nelsen, R.B. An Introduction to Copulas; Springer, 2006.

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press, 2018.

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

Otherwise, the market does not clear and the acquirer would likely have to raise its price. We do not study the likelihood of this event here as it is likely highly dependent on the nature of the acquired capability and the operational context in which it would be used. |

| 3 |

This could occur because the acquirer is unlikely to be a monolithic entity making completely rational decisions; instead, it is likely to be an institution (e.g., a nation’s Ministry of Defense or a company’s risk management division) exhibiting internal principal-agent problems and other organizational considerations. For example, it may be beneficial to an individual within the organization to price an ARS lower than its true value to receive short-term commendation for lowering risk management expenditures. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).