1. Introduction

Despite initial rejection of the Bachelier model [

6], its arithmetic Brownian motion dynamics have found acceptance in certain areas. To combine the strengths of both arithmetic and geometric Brownian motion models, the classical Black–Scholes–Merton (BSM) model [

7,

27] has been merged with a modernized Bachelier (MB) model [

31], producing a unified Bachelier–Black–Scholes–Merton (BBSM) model [

25]. Both the unified model and its MB limit allow for price trajectories taking values in

, while, under the BSM limit, price processes take values in

. Exploiting the more extensive price range of the MB model, [

31] developed a dynamic ESG-adjusted valuation (“ESG-adjusted pricing”) for assets, which allows for stocks with low ESG ratings to be given a negative ESG-adjusted value. A critical parameter of the adjusted valuation is the so-called ESG affinity, quantifying the market view of the “size” of the contribution of ESG ratings to asset values. [

5] explored fair valuation of options under the MB model using this ESG-adjusted asset valuation.

Consideration of ESG factors in financial modeling marks a paradigm shift in how asset values are assessed. As the world evolves toward a greener future, industry leaders must champion sustainability. (However, see [

15] for a study of how sustainability efforts have varied by market). Providing a solid quantitative use for ESG ratings is an important step in the effort to champion sustainability in the financial world. Consideration of ESG-adjusted prices alters the investment approach required for long-term investing, enabling ESG-conscious investors to more effectively measure, and (potentially) profit from, ESG strategies. Analyses based on such pricing must be woven into the investment processes of any discerning investor, as well as integrated into the corporate strategy of any company that is truly committed to increasing shareholder value [

21].

The first goal of this paper is to embed ESG asset valuation within the continuous-time BBSM model (

Section 2), placing ESG finance within the broader framework of a unified Bachelier and Black–Scholes–Merton theory. In

Section 3, we embed the ESG-adjusted asset valuation into the BBSM binomial option pricing model of [

25].

The second goal is to provide an empirical study of discrete option pricing under the ESG-BBSM binomial model of

Section 3. Our data set for 16 stocks selected from the Nasdaq-100 is described in

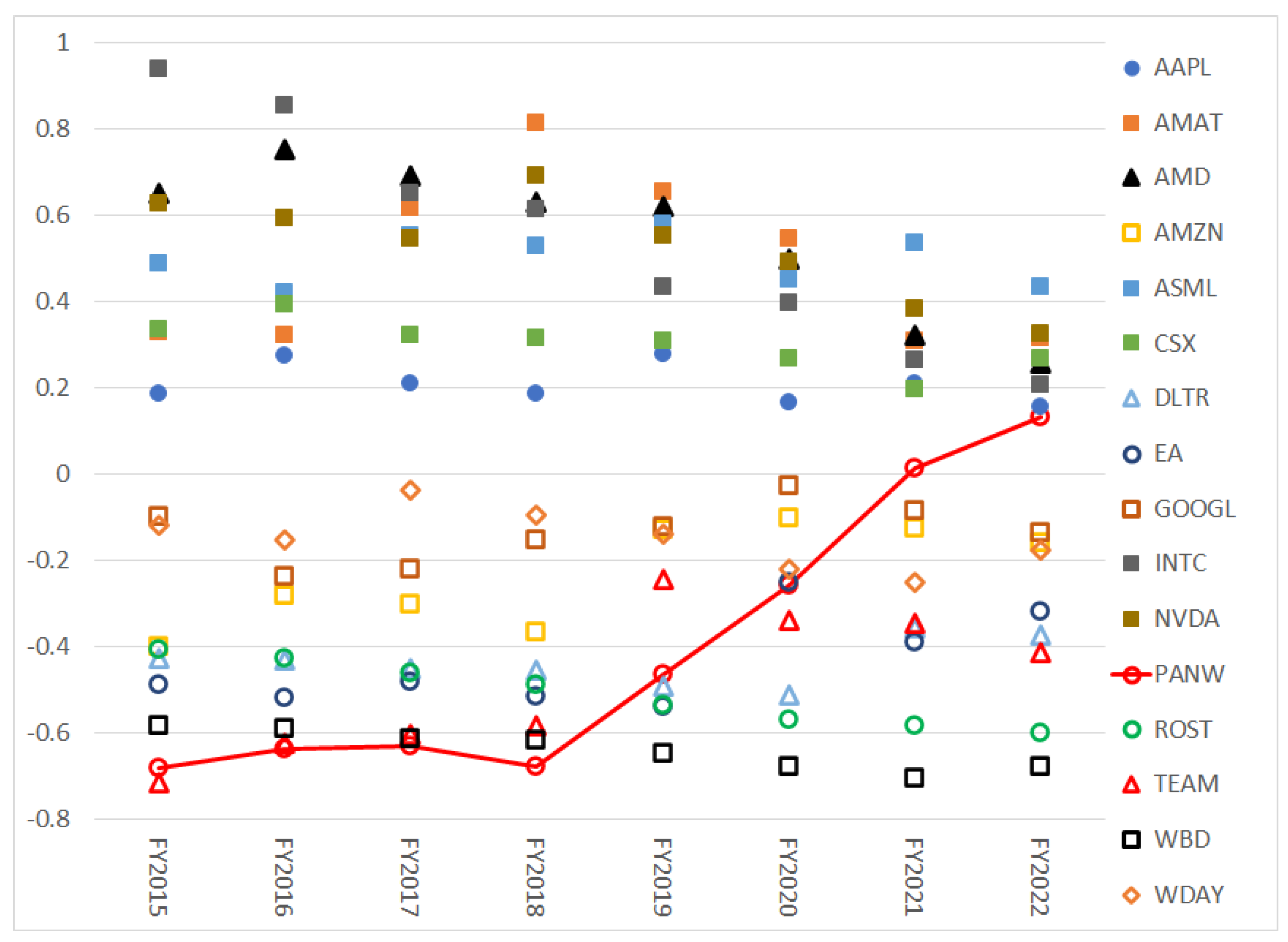

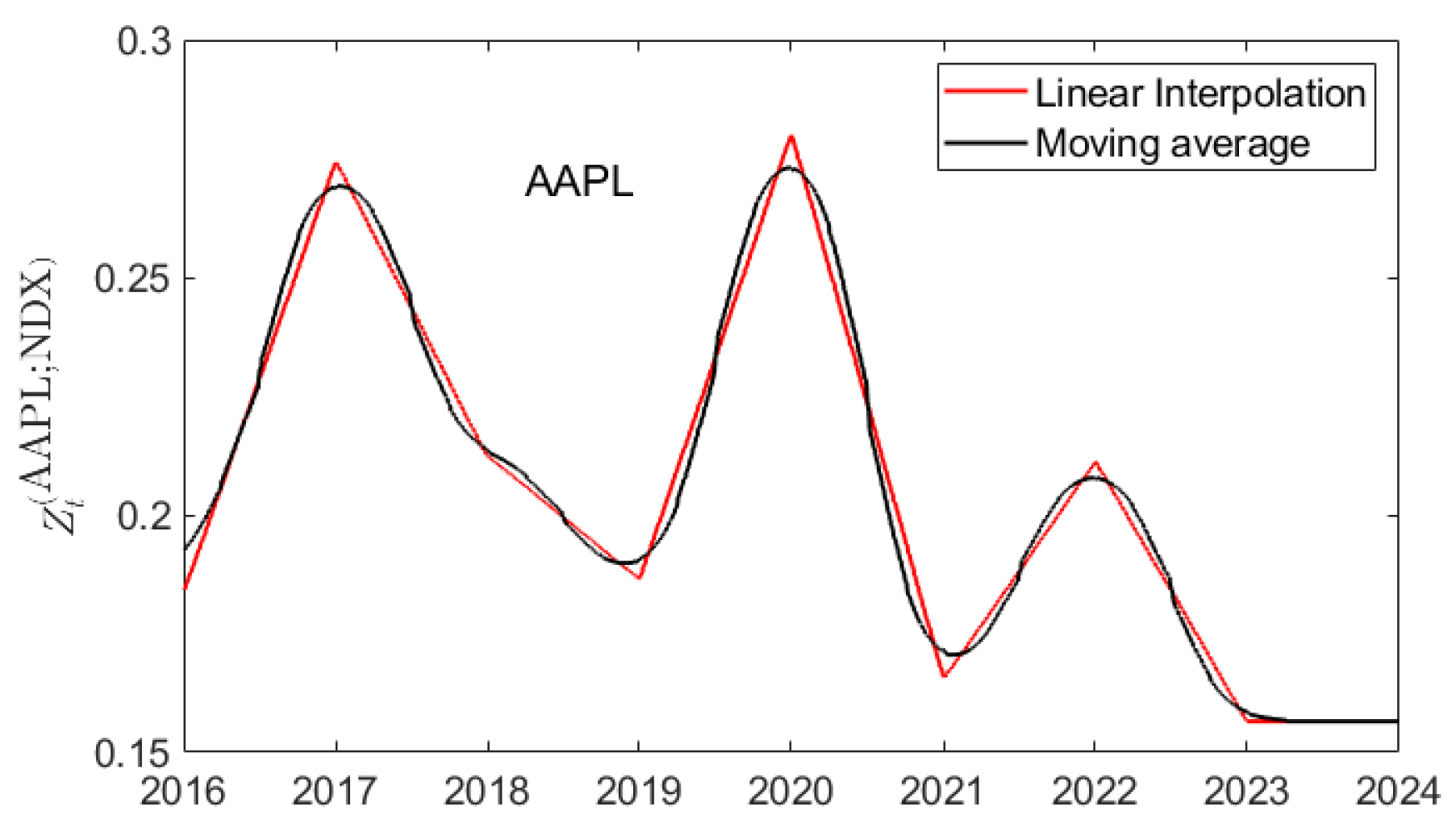

Section 4.1. Empirical examples of ESG-adjusted prices are presented in

Section 4.2. In

Section 4.3 we describe how to fit the required parameters of the binomial model to empirical data. In

Section 5, using published call option prices for 01/02/2024, we compute implied values of the ESG affinity parameter as functions of strike price and time to maturity. These can then be expressed in terms of an implied ESG valuation (as a function of strike price and time to maturity). Comparing the implied ESG valuation to financial spot prices provides insight into the views of option traders on the impact of ESG ratings on the underlying asset value.

The third goal of this study (

Section 6) focuses on a discrete-time, futures trading strategy that can be adopted by an option hedger (the trader taking a short position on an option) who may posses information regarding the future direction of movement of the ESG-adjusted valuation of the underlying stock. While the efficient market hypothesis argues that the direction of the asset price movement is unpredictable [

2,

3,

14,

17,

18,

19,

20,

23,

29], numerous studies challenge this view and indicate that price direction may, indeed, be predictable [

1,

4,

8,

9,

11,

12,

24,

26,

28,

30,

34,

35,

36,

38,

39]. As a result, [

10,

13,

37] and many others have worked on understanding informed trading markets and the strategies employed. We demonstrate that the trader can optimize this trading strategy to produce an effective dividend stream.

Section 7 concludes the paper with a discussion of future directions.

2. Embedding ESG pricing in the BBSM model

Consider the market

consisting of a risky asset

, a riskless asset

, and a European contingency claim (option)

. Under BBSM,

has the price dynamics of a continuous diffusion process determined by the stochastic differential equation

where

is a standard Brownian motion on a stochastic basis

of a complete probability space (

). The coefficients satisfy

,

,

,

, and are

-adapted processes. The

-adapted processes

and

are assumed to satisfy the usual regularity conditions.

1 [

25] define the appropriate price dynamics

2 of the riskless asset

in the BBSM market model as

Again,

and

are

-adapted processes. The

-adapted process

is also assumed to satisfy the usual regularity conditions.

3 The MB model is achieved as the limiting case

, while the classical BSM model is the limiting case

. For brevity, we adopt the notation

,

and

. We require

,

-almost surely (a.s.). A necessary condition for no-arbitrage is the requirement that

,

-a.s. Under the no-arbitrage assumption, the market price of risk is

which is strictly positive

-a.s. for all

providing

,

-.a.s.

The option

has the price dynamics

where

,

,

, has continuous partial derivatives

and

on

, and

T is the expiration (maturity) time of

. The option’s maturity payoff is

for some continuous function

. The risk-neutral valuation of

is [

25]

where

is the equivalent martingale measure and the asset price dynamics under

is

In (

6),

,

, is a standard Brownian motion on the stochastic basis

.

Consider a published ESG rating

4 (score)

for a company

X at time

t. argue that bounded scales for an ESG score do not differentiate adequately between the amount of effort that a company must undergo to raise their score above a current value.

5 They further argue that scores based upon a convex, monotonically increasing function better represent such effort, and that the choice of such a function should be based ultimately on an axiomatic approach. In the absence of such an approach, they proposed the relative ESG measure

where

is the ESG rating (score) of company

X and

is the ESG score of a relevant market index

I.

6 They further define the ESG-adjusted stock price of company

X at time

by

which incorporates ESG scores as part of an asset’s valuation. Here

represents the financial price of an asset, while

represents an ESG-adjusted valuation,

7 which refer to as the ESG-adjusted price. In (

8),

is referred to as the ESG affinity of the financial market.

8

The ESG-adjusted stock price (

8) can be negative.

9 This is not surprising as the relative score

is analogous to any financial `spread’. We note the following dependencies of

on

.

From (

9a) through (9d), we see that changing the value of

only affects the (additional) fractional financial price term

, which satisfies

.

3. Binomial Option Pricing under the BBSM Model

[

25], Section 7 developed a binomial option pricing model under the BBSM model. We briefly summarize that model here. Consider a BBSM market

) consisting of the risky asset (stock)

, the

and call option

. The stock price

evolves according to the binomial pricing tree

In (

10),

, is the stock price at time

,

where

T is the fixed maturity time and

. For every

,

,

, are independent, identically distributed Bernoulli random variables with

determining the filtration

of the stochastic basis

on the complete probability space

. The riskless asset

has the discrete price dynamics

where

is the instantaneous rate of (

2) at times

.

Under BBSM, price changes, rather than returns, are of primary interest. Let

Then,

In order that the càdlàg process on the Skorokhod space

generated by the binomial tree (

10) converge weakly to the continuous time process (

1), we require that the conditional mean and variance satisfy

where

and

are the instantaneous mean and variance of (

6) at time

. Then

and

are given by

The option

has the discrete price dynamics

,

. Consider a self-financing strategy,

replicating the option price process

:

The standard no-arbitrage arguments lead to

Thus, the risk-neutral valuation of the option is given by the recursion

where the risk-neutral probability

is

The limit

of (

18) and (

19) produces the option price recursion relation for the BSM model,

having risk-neutral probability

where

is the discrete form of the market price of risk,

, in the BSM model.

10 In this limit, the discrete price of the riskless asset obeys,

.

The limit

, produces the option price recursion relation for the [

31] Bachelier model,

The risk-neutral probability

is (see also [

22]),

In this limit, the discrete price of the riskless asset obeys

.

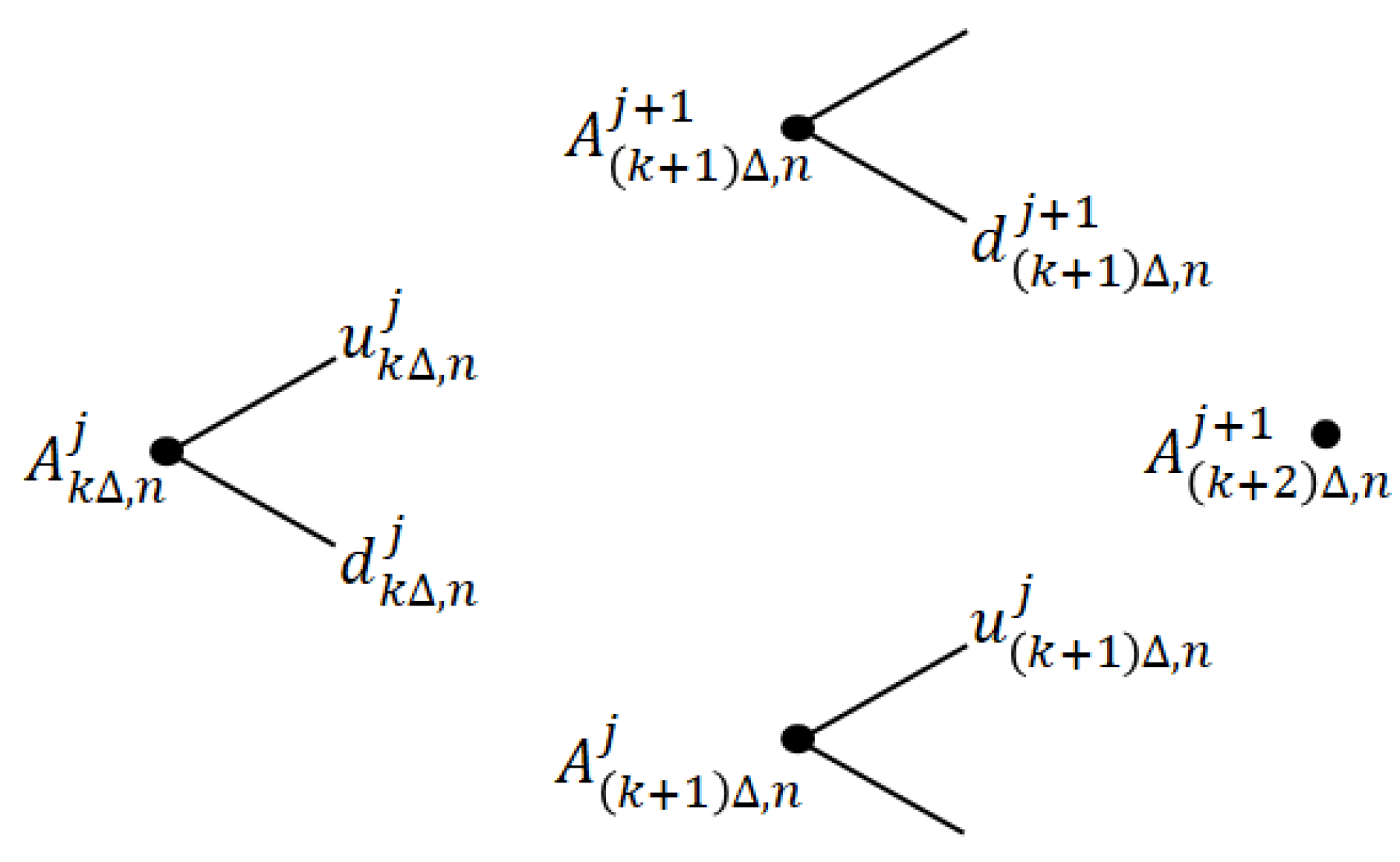

3.1. The Binomial Model is Not Recombining

A careful analysis shows that the risky-asset asset price process (

10) does not, in fact, form a recombining tree. For a fixed value of

k,

, the superscripts

and

determine node “level” values at time

. For a recombining binomial tree, at time

k, there are

level numbers Thus each node on the tree is indexed by a

pair,

,

. With the inclusion of level numbers, (

10) is written as

where, from (

16),

Figure 1 illustrates a price configuration on four nodes of the tree, with time and level values indicated. Substituting (

25) into (

24) gives

where

Note that , , , and are constants.

For the tree to be recombining, in

Figure 1 we must have

With some algebra, the difference

can be shown to be

independent of time or level number.

11 To ensure that the tree is numerically recombining in our empirical work in

Section 4, we define

We note that

vanishes more rapidly than

and

terms as

. However, theoretical work remains to be done to ascertain whether the càdlàg process on the Skorokhod space

generated by either (

10) or (

30) does indeed converge weakly to the continuous time process (

1). We leave this question open for further investigation. We do note that the BSM and MB limits of the price process (

10) are indeed recombining (binomial) trees whose generated càdlàg processes do converge weakly to the appropriate BSM and MB limits of the continuous time process (

1).

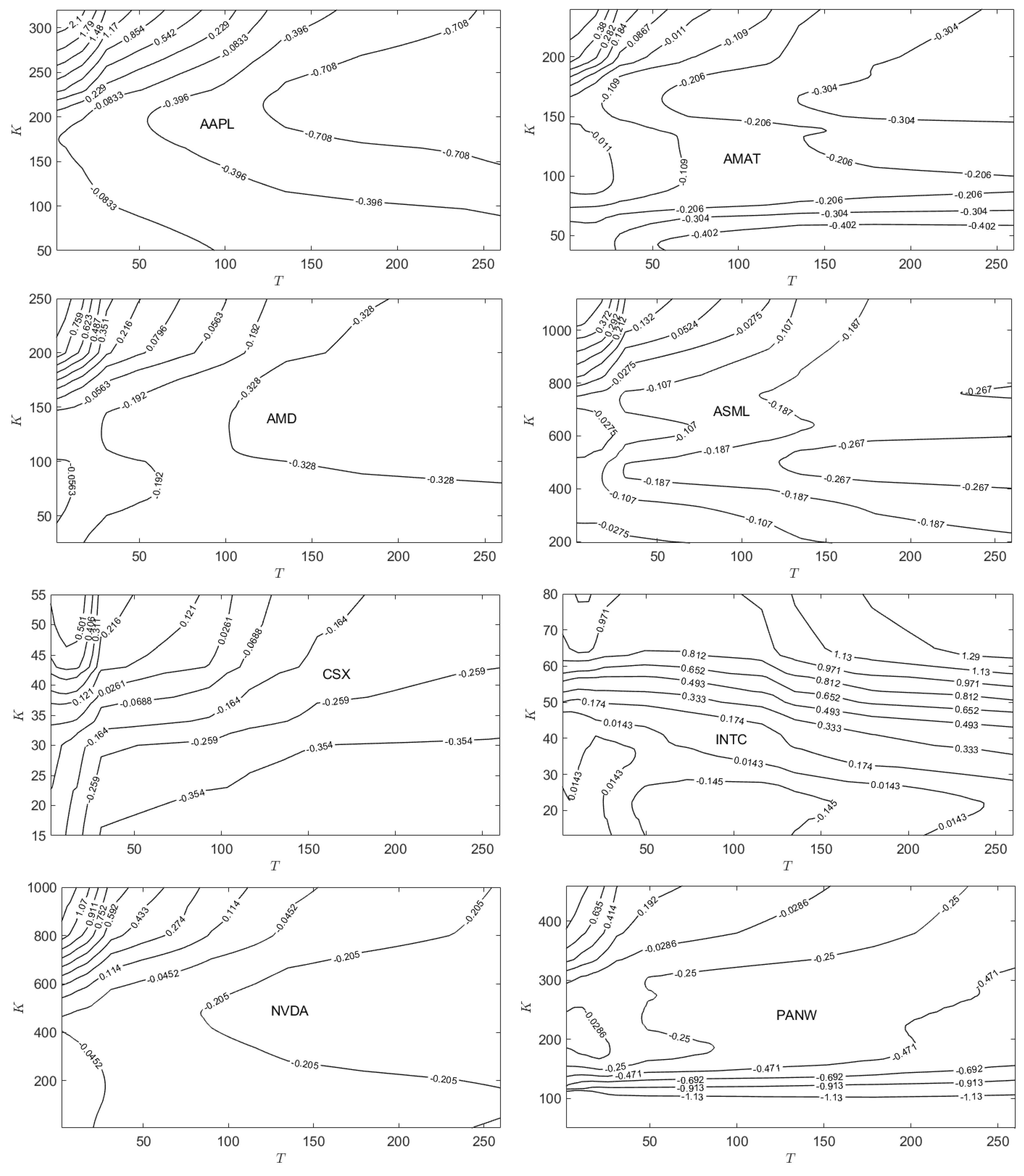

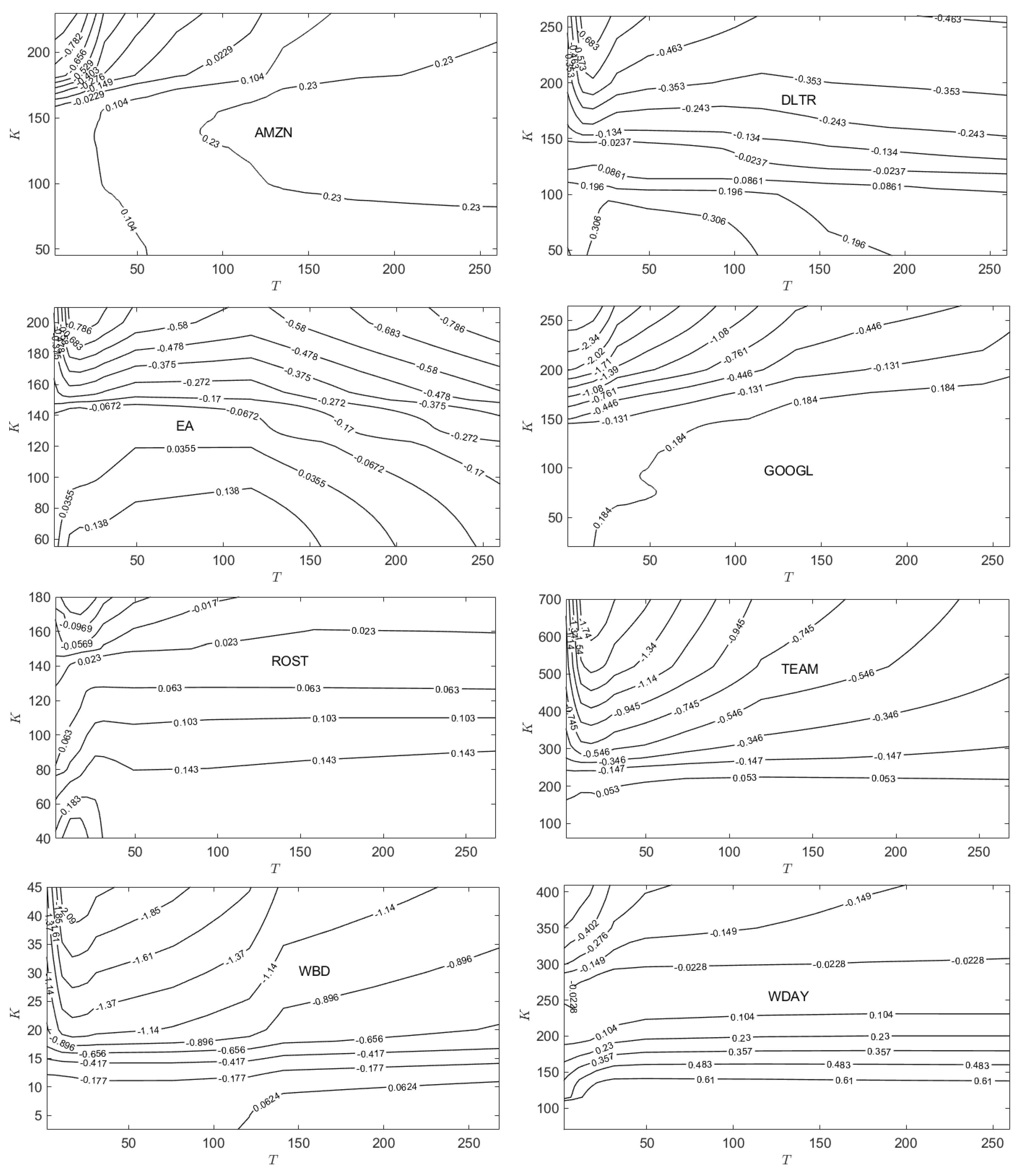

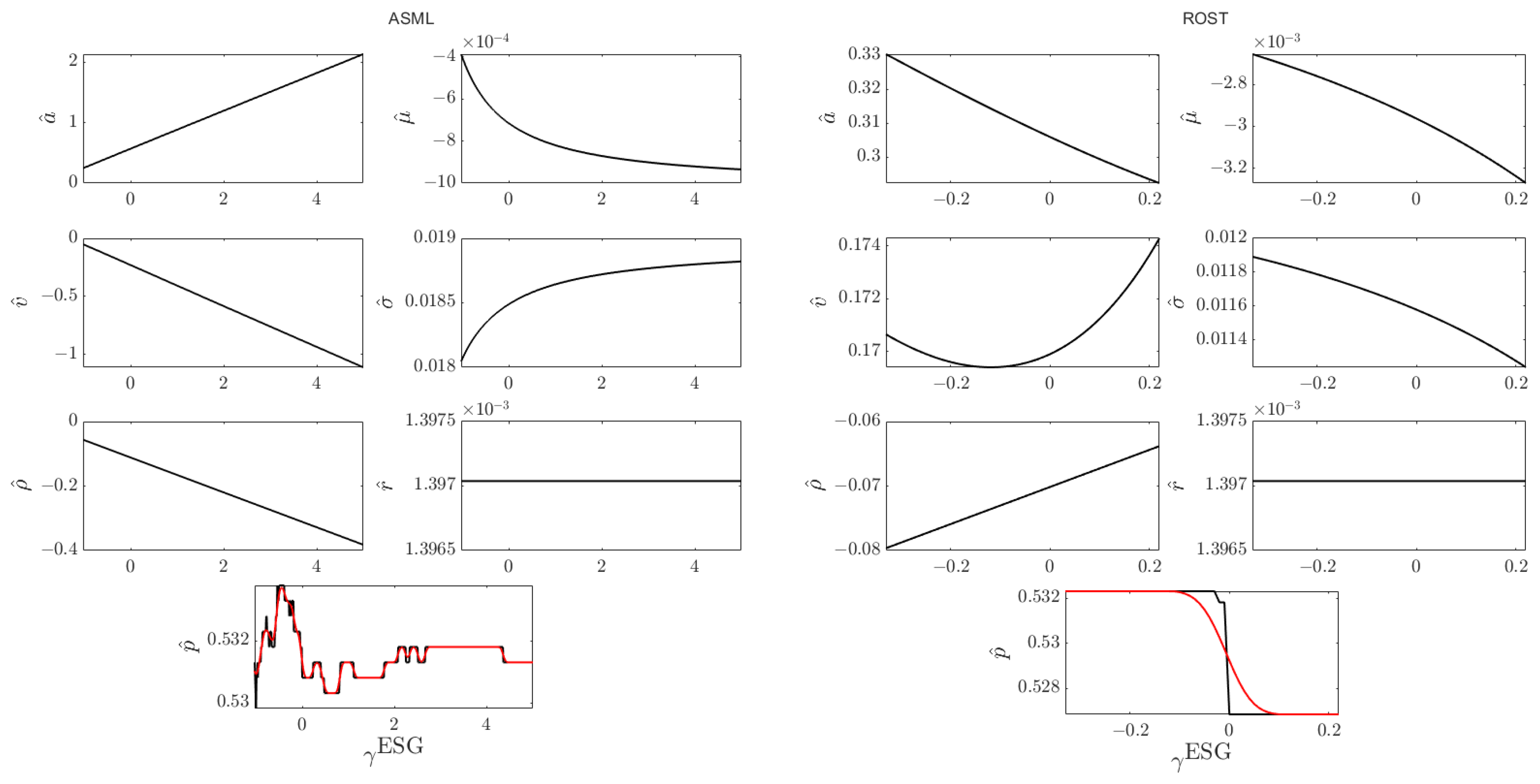

5. The Implied ESG Affinity

Let

denote published call option prices for an underlying stock having maturity date

,

, and strike price

,

. Let

denote the call option price computed from

Section 3 with constant parameters values. Let

denote the historical estimation of any parameter

. (Recall that, except for

, the parameters have dependence on the value of

.) Then implied values for

are computed via

Based upon call option prices published on 01/02/2024,

21 we computed theoretical call option prices for the same set of strike prices,

,

, and maturity times

,

. In (

39), the parameters

used in the theoretical option computation were fit from the historical data for each value of

tested in the minimization procedure. As the value of

is independent of the value of

and of the stock, theoretically it only needed to be calculated once. However, it is computed from the same regression (

36) that produces

, so it was recomputed for each value of

tested. The value

used to compute prices on the binomial tree was the smoothed value for 01/02/2024.

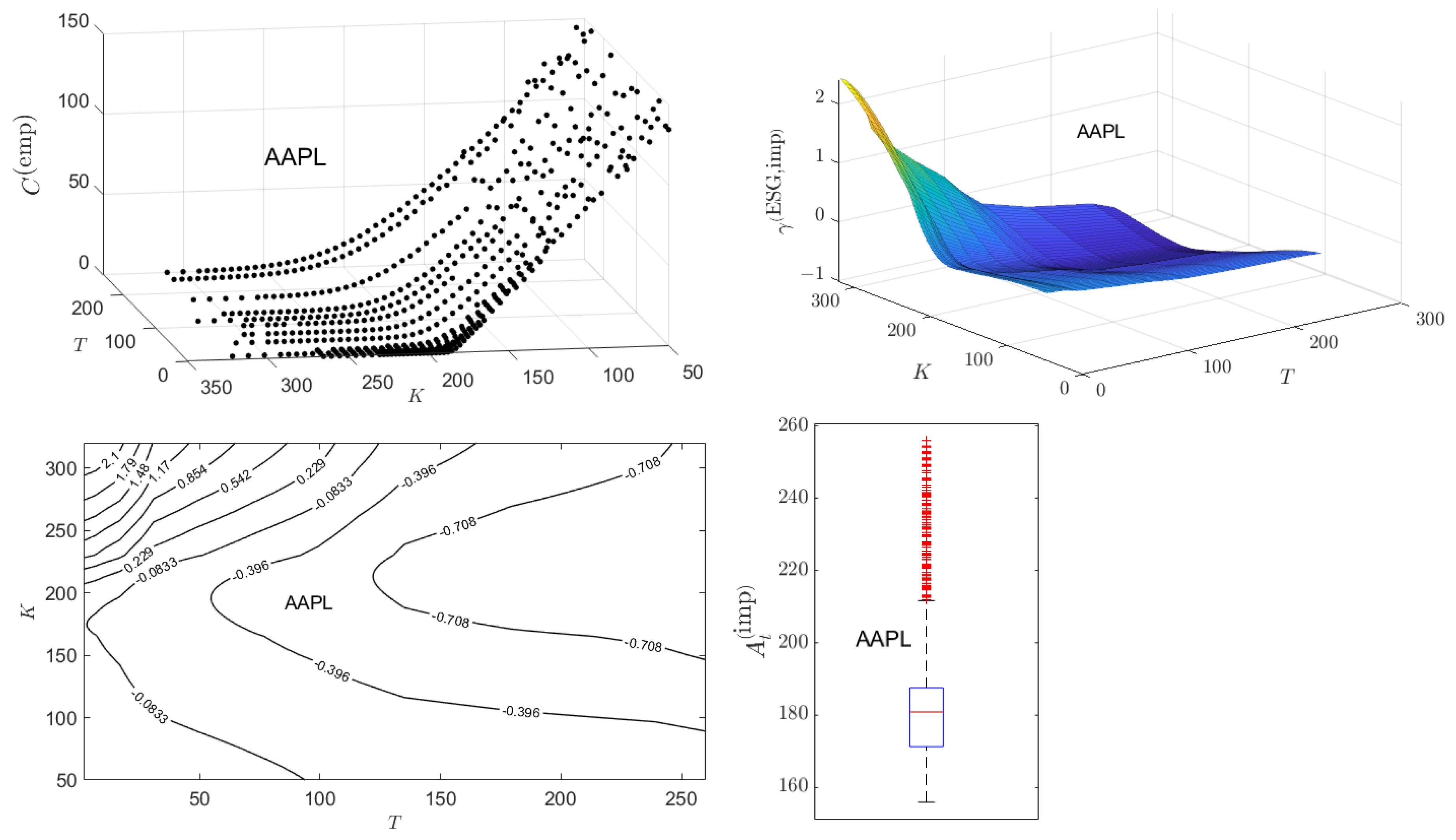

The published call option prices for AAPL on 01/02/2024 are presented in

Figure 8.

22 In contrast to some of the other stocks investigated, these option prices form a fairly “regular” surface over the published range of

,

, and maturity times

,

values. The values

computed from (

39) are plotted as a surface in

Figure 8.

23 Analysis of the

surface is enhanced by consideration of surface contours as shown in the bottom left of the figure. The

contour lies between the contours

and

, indicating that option traders have a positive view (relative to ^NDX) of the ESG rating of AAPL in the upper left triangular region of out-of-the money (the adjusted closing price for AAPL on 01/02/2024 was

$185.64) strike prices and maturity dates not exceeding 110 trading days. However, over the majority of

values, the option traders have a negative view of the ESG rating of AAPL.

A further view of the

values is presented in

Figure 8 as a box-whisker summary of the distribution over the surface.

Table A1 in

Appendix A presents the numerical values of the minumum, maximum,

,

, and

percentiles of the

distribution for AAPL. This table also presents the

for AAPL based upon examination of historical adjusted ESG prices discussed in

Section 4.3. The overwhelming majority of

values lie within the

for AAPL, giving some confidence that the implied ESG affinity values being computed are consistent with semi-martingale behavior of the associated ESG-adjusted price.

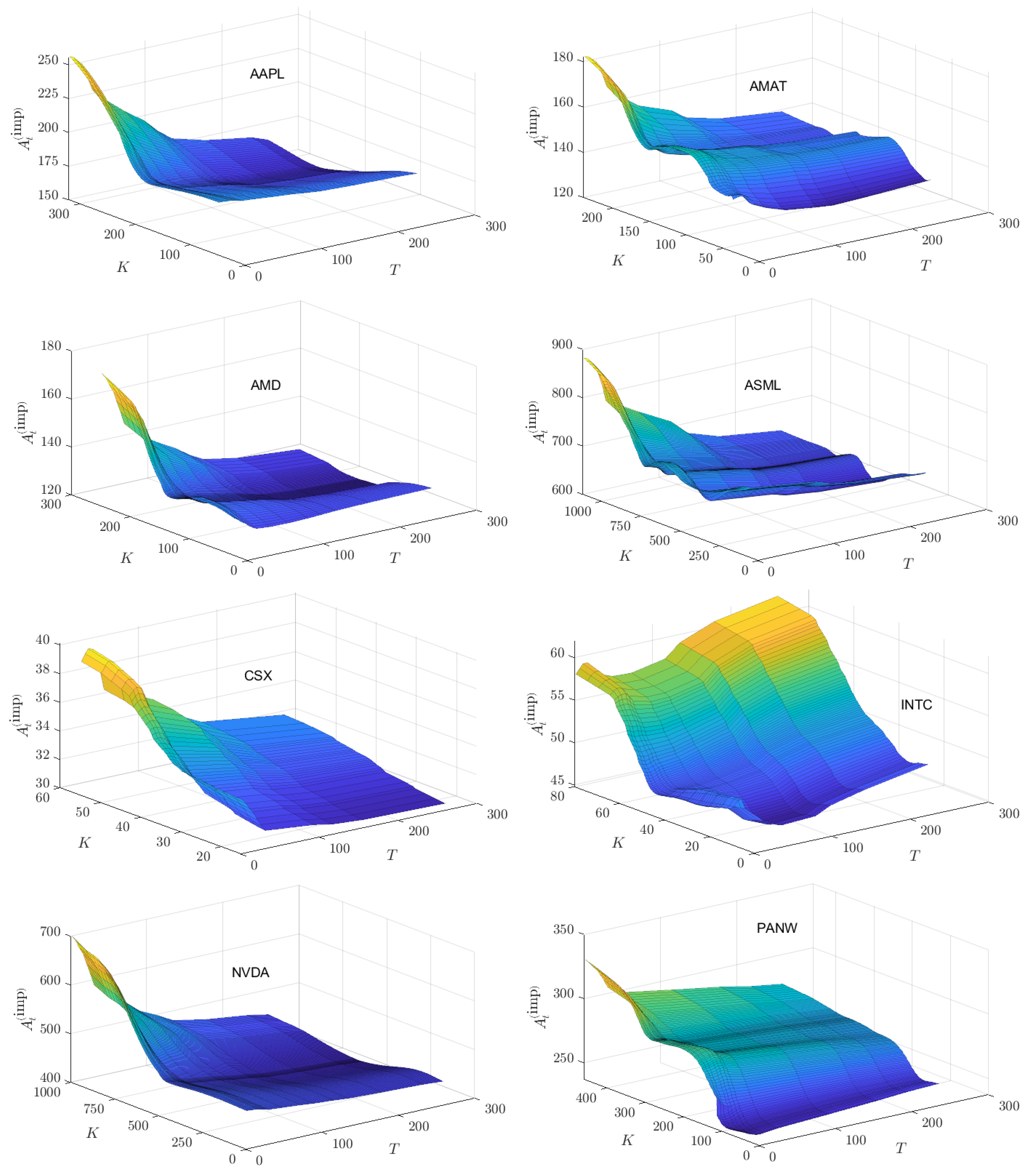

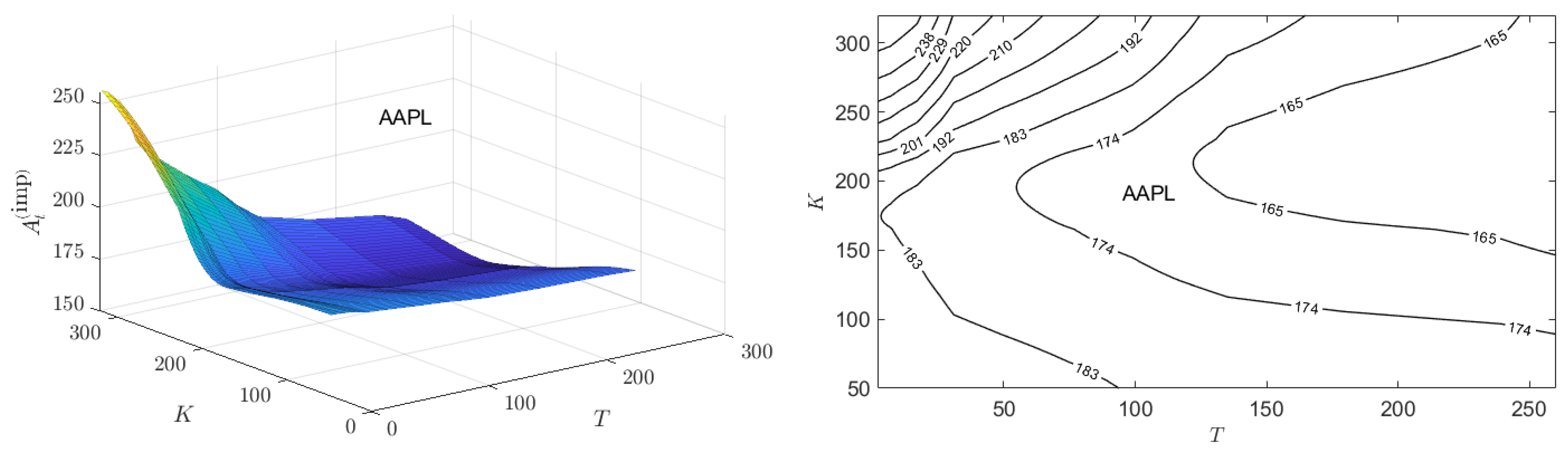

To appreciate the implication of this, we define from (

8) an implied ESG-adjusted price

where, for a given stock

X,

is a value from the implied ESG affinity surface, and

was the relative ESG score and

the spot price price used in computing the surface.

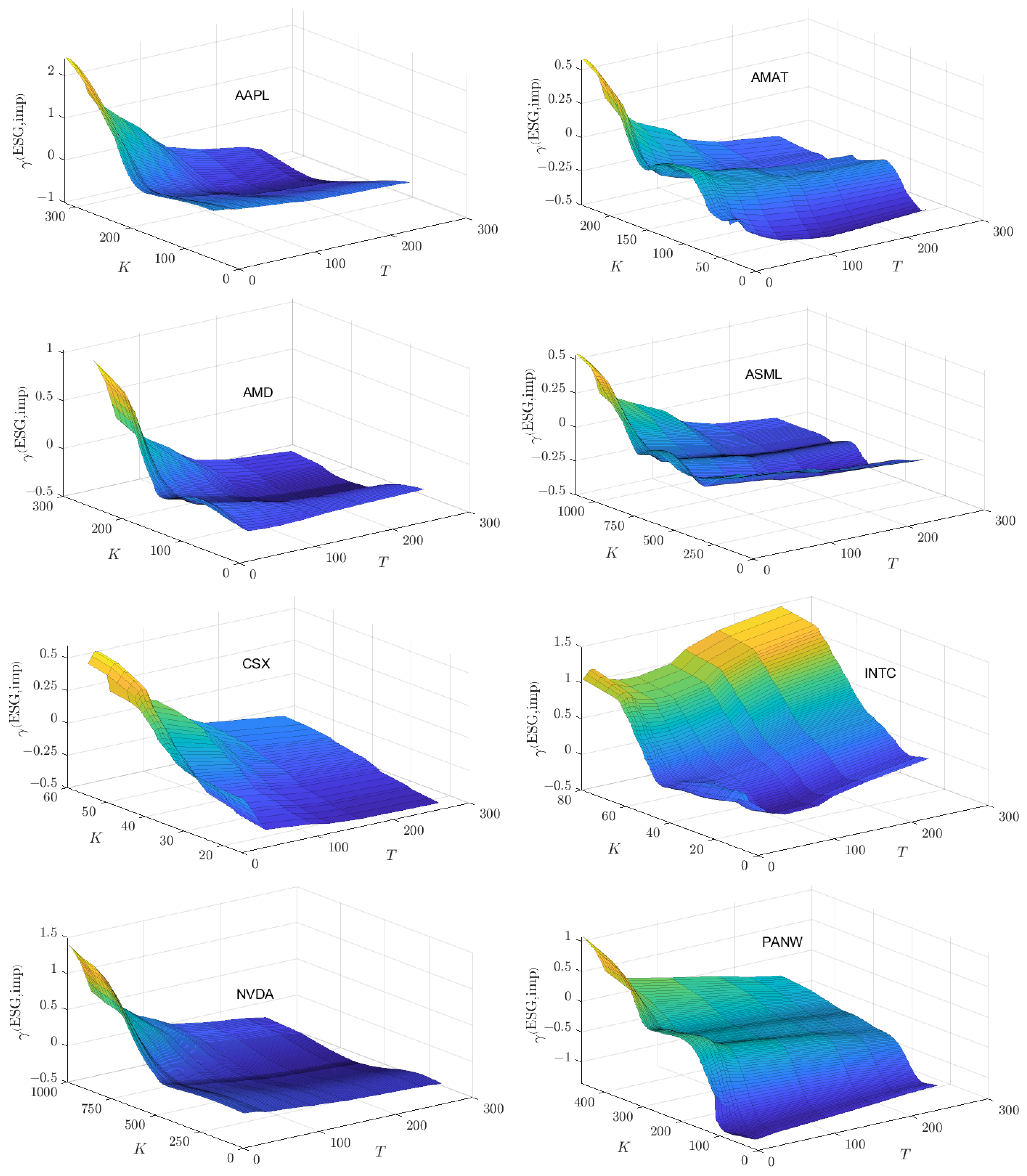

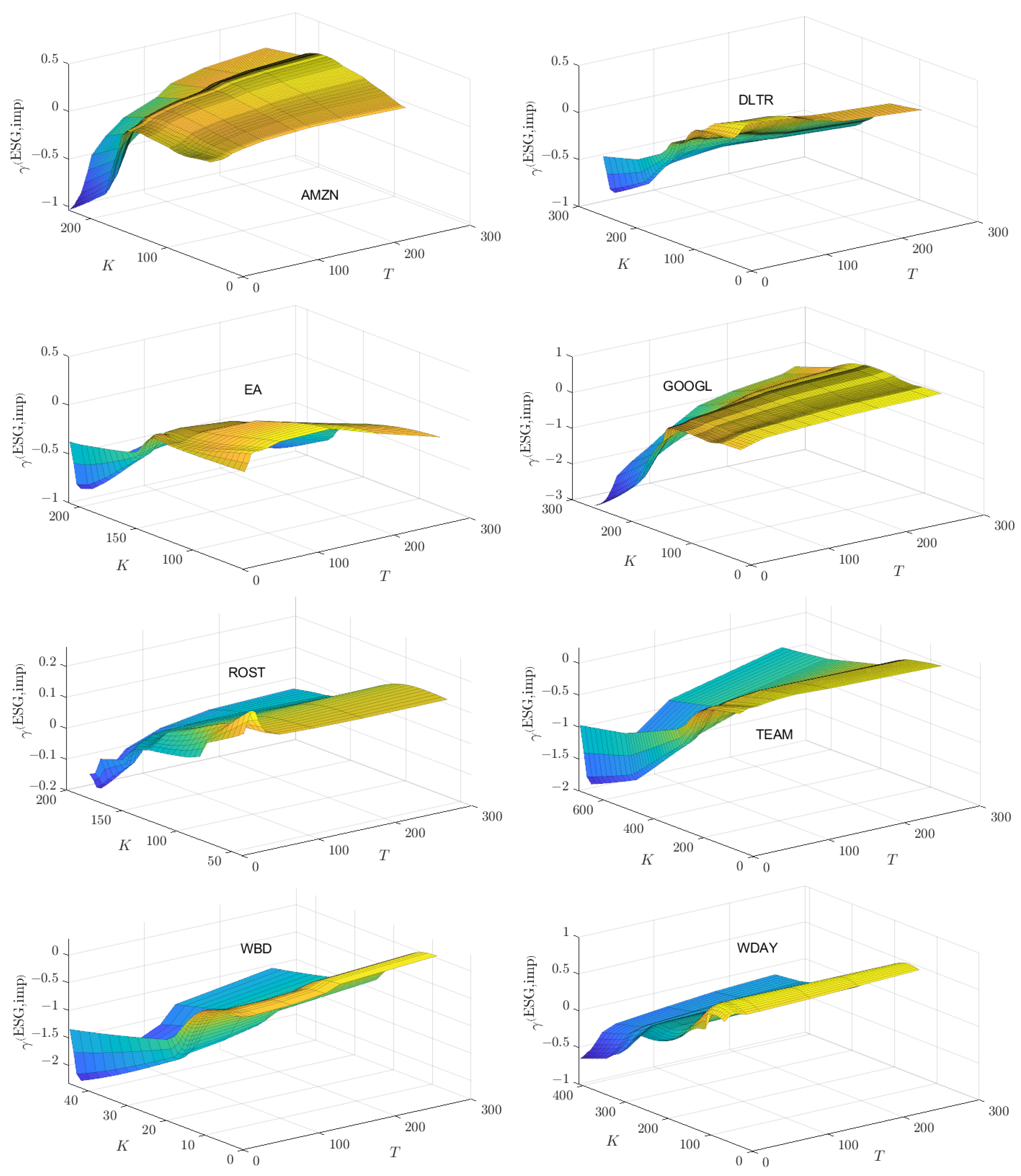

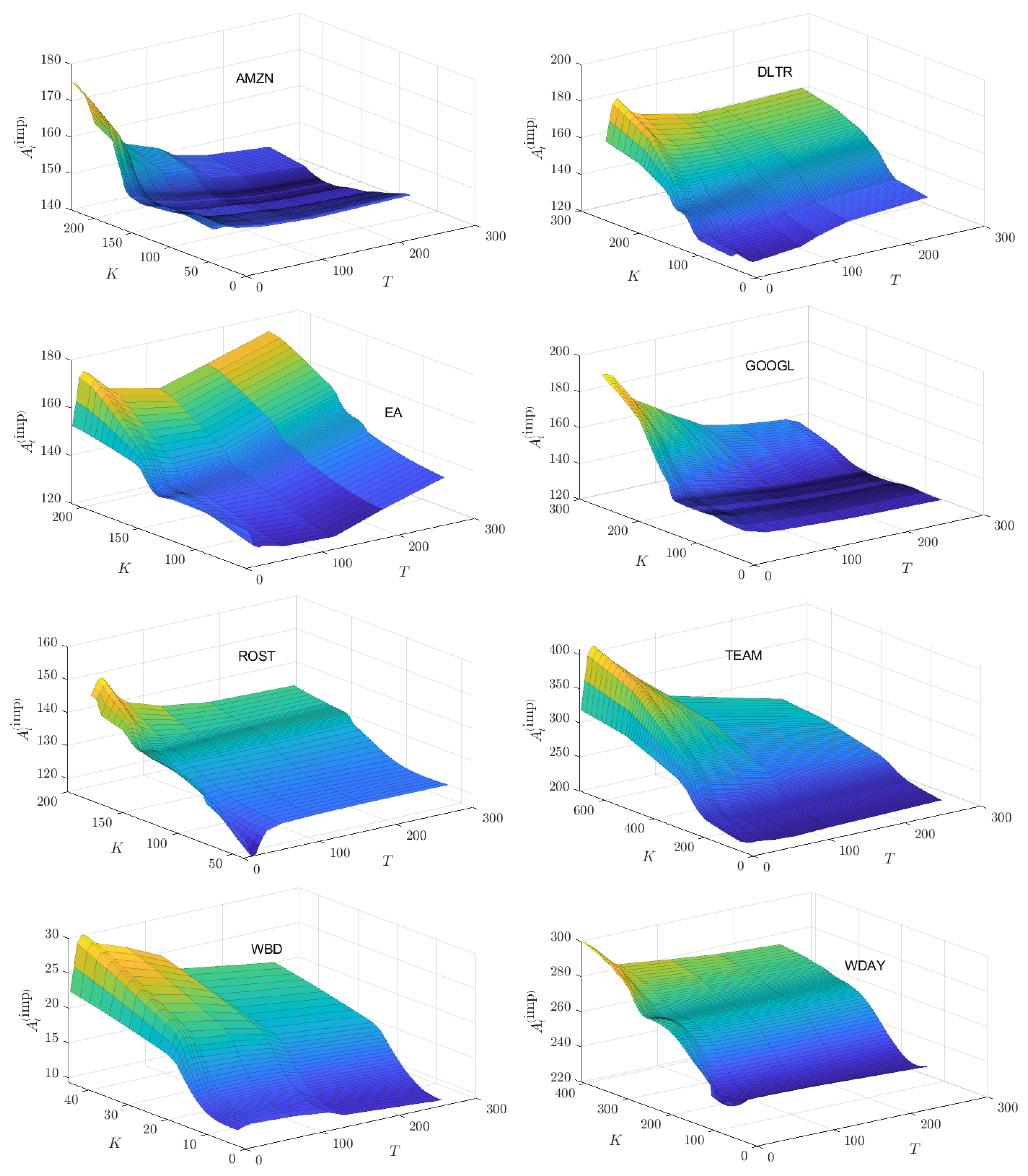

Figure 9 presents the surface of

values computed from the

values of

Figure 8. Also shown are contour levels of the

corresponding to the analogous contour levels of

shown in

Figure 8. Whether

is larger or smaller than

depends on the sign of the product

. If

is positive, then positive values of

correspond to an ESG valuation that exceeds

. However, if

is negative, then negative values of

correspond to an ESG valuation that exceeds

. Thus, consideration of the

surfaces rather than the

surfaces provides direct insight into the views of option traders on the ESG-valuation of stocks.

Since was positive on 01/02/2024, the surfaces of and are identical except for a rescaling of the z-axis. Similarly the contour plots for and are identical except for a rescaling of the value on the contour levels. The negative view of the option traders over most of the range for AAPL, results in implied, ESG-adjusted prices for 01/02/2024 that correspondingly fall below the financial price of AAPL on 01/02/2024.

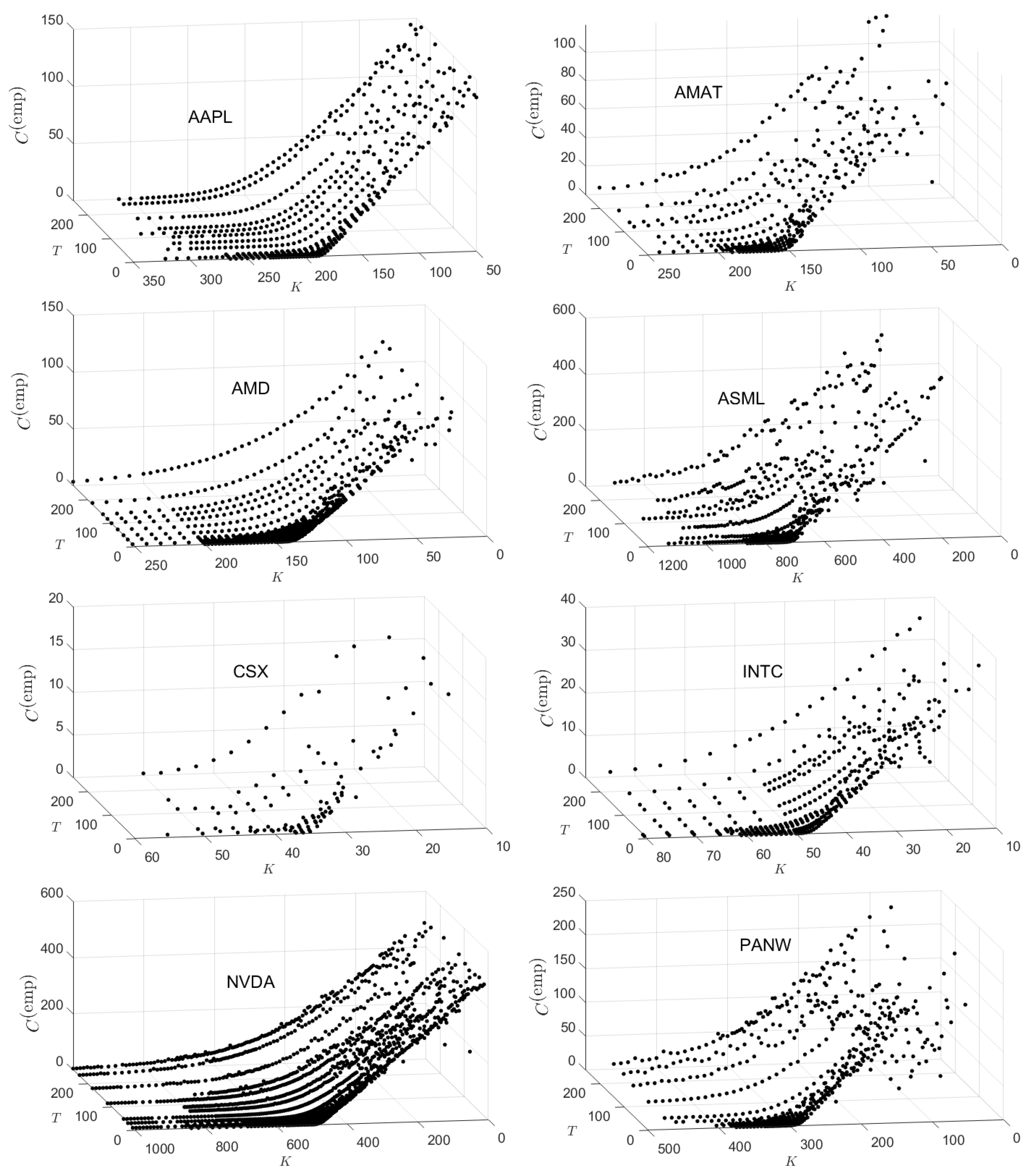

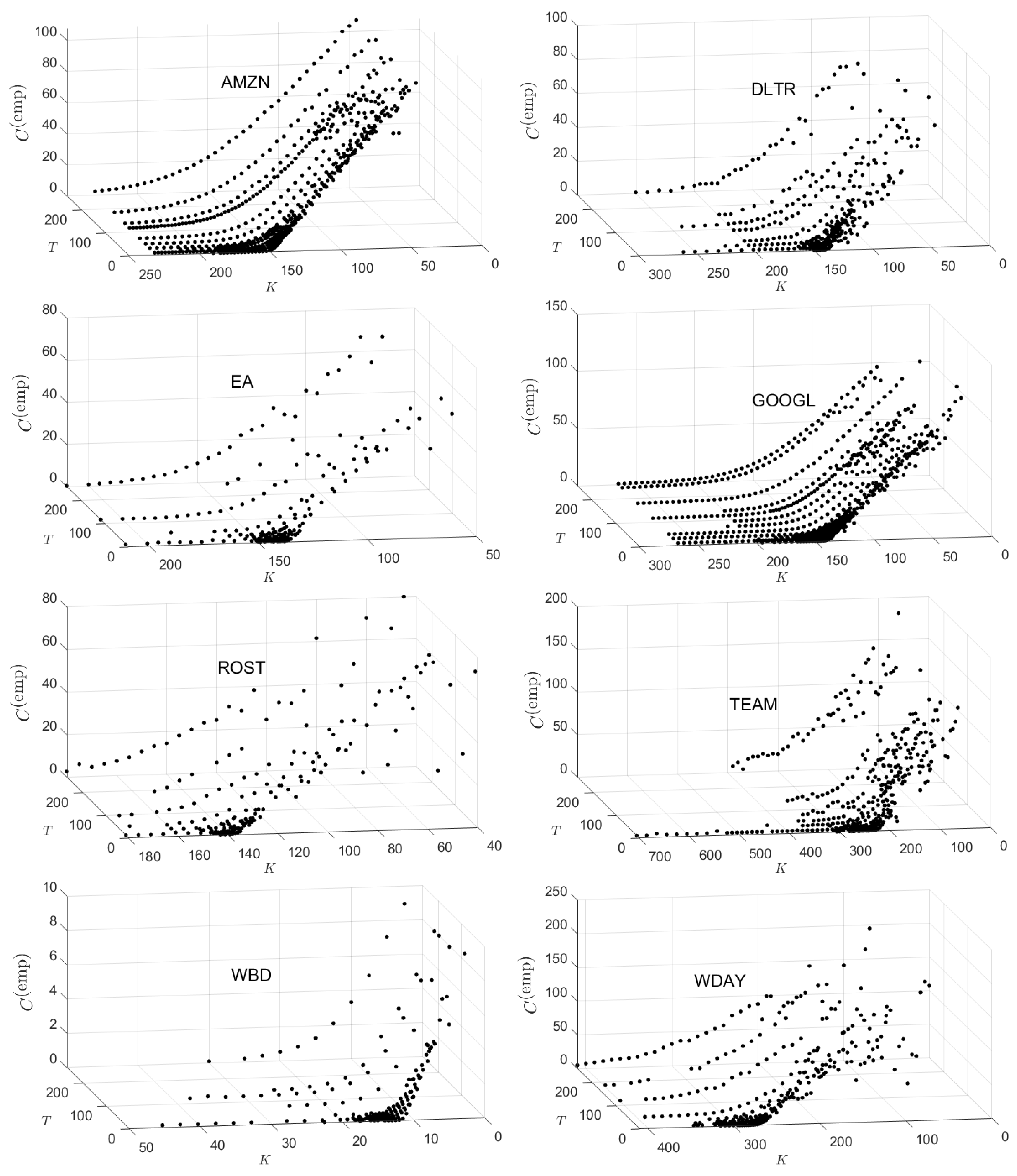

Figs.

Figure A1 and

Figure A2 in

Appendix B plot the published option prices on 01/02/2024 for all 16 stocks studied. The eight stocks for which

on

01/02/2024 are presented in

Figure A1, while the eight stocks for which

are presented in

Figure A2. This separation reflects the fact that when

, the corresponding surfaces for

and

will look like identical (rescaled) versions of each other. However, when

, the surface

will look like an inverted, rescaled version of the corresponding

surface. Examination of published option prices for PANW, TEAM, and WDAY show much greater irregularity over the range of

K and

T values than that shown for AAPL.

24

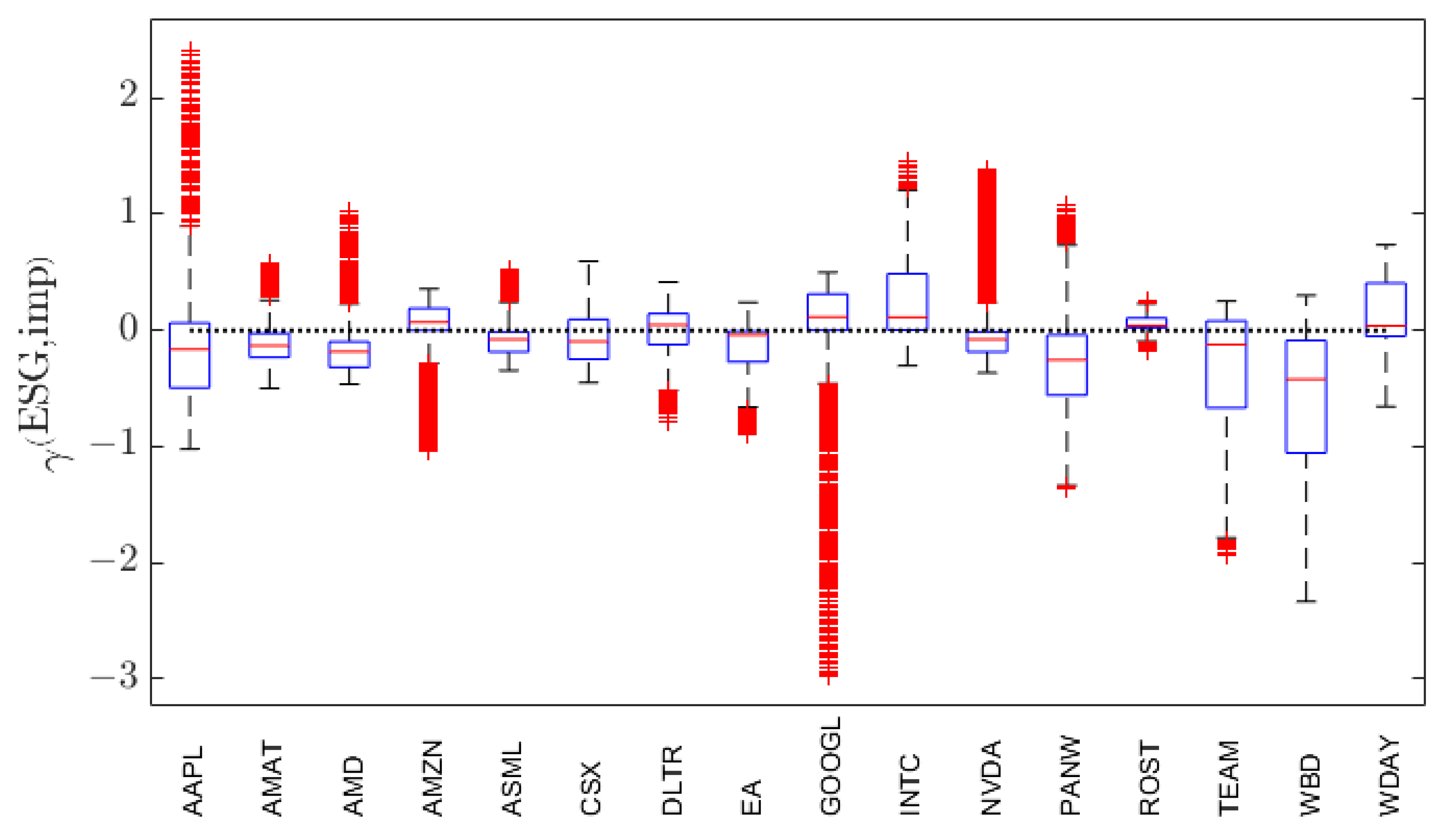

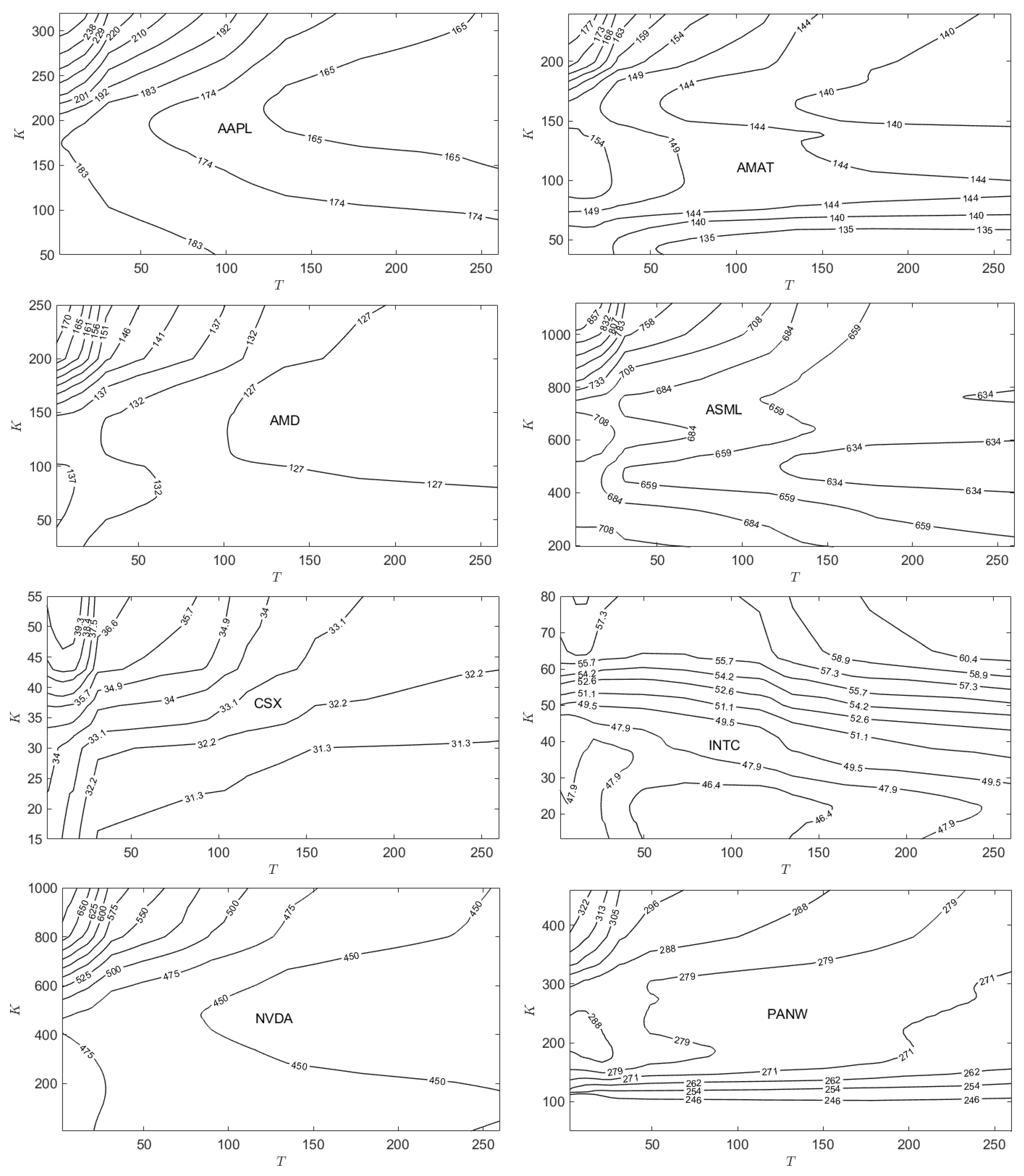

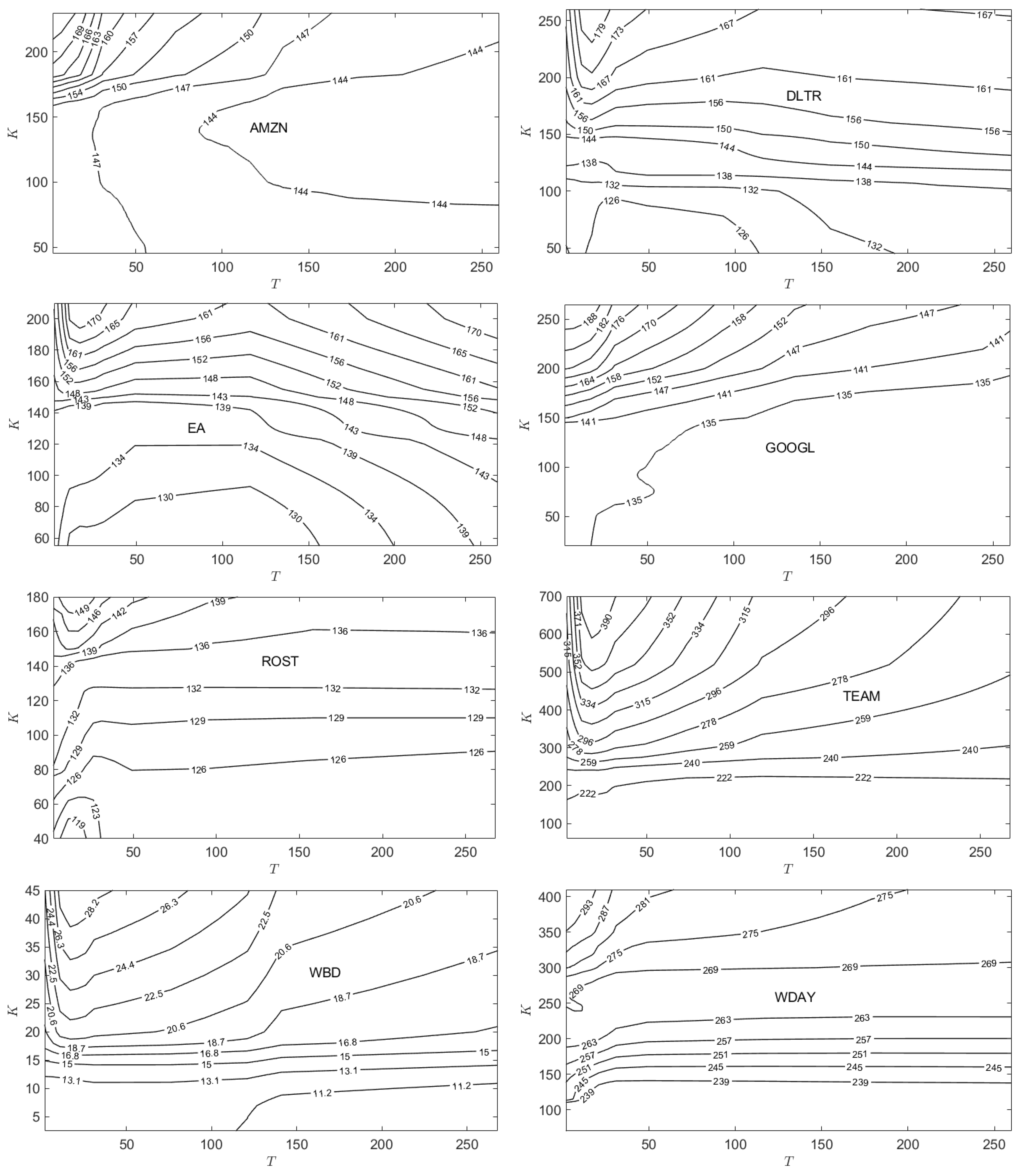

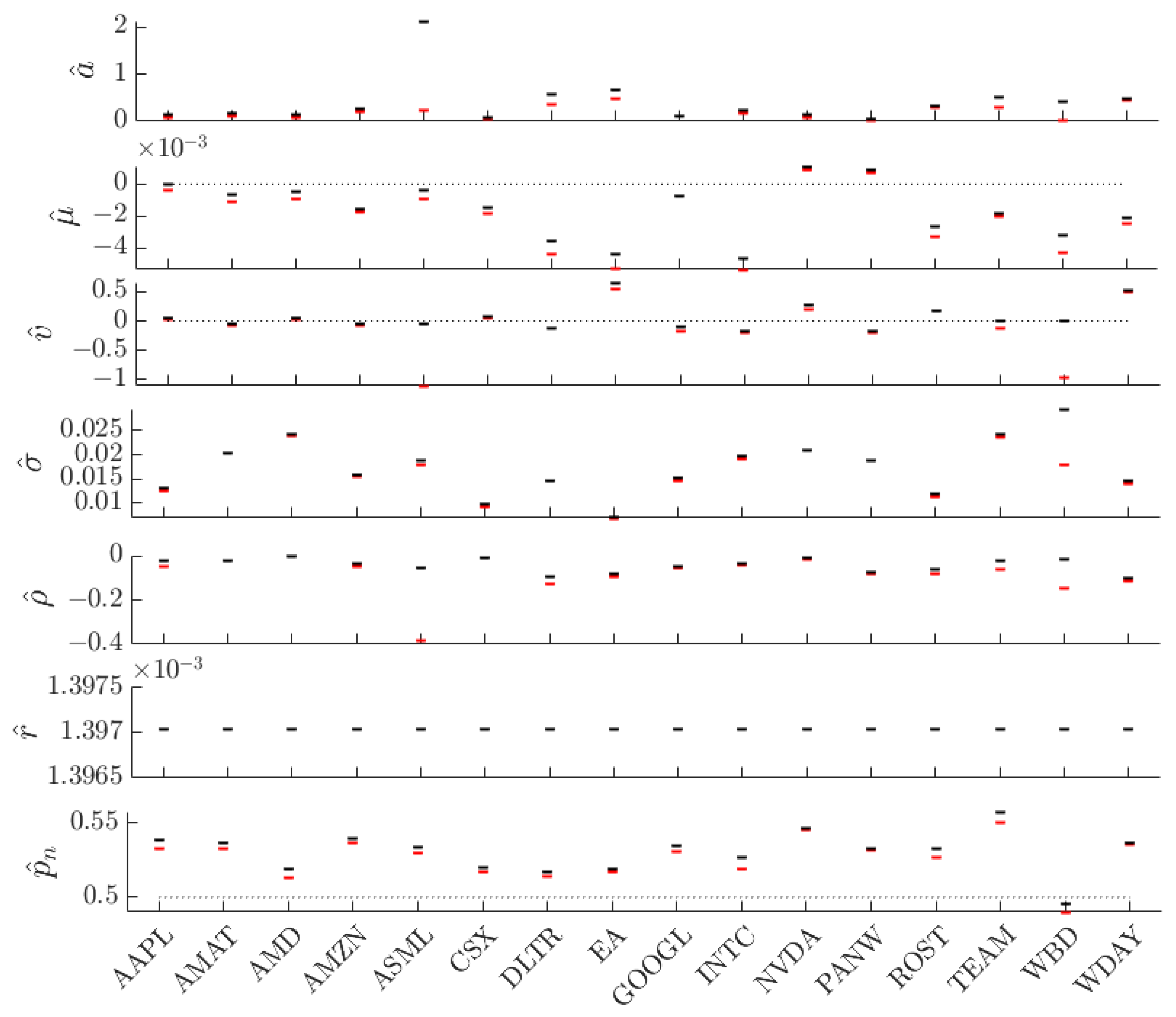

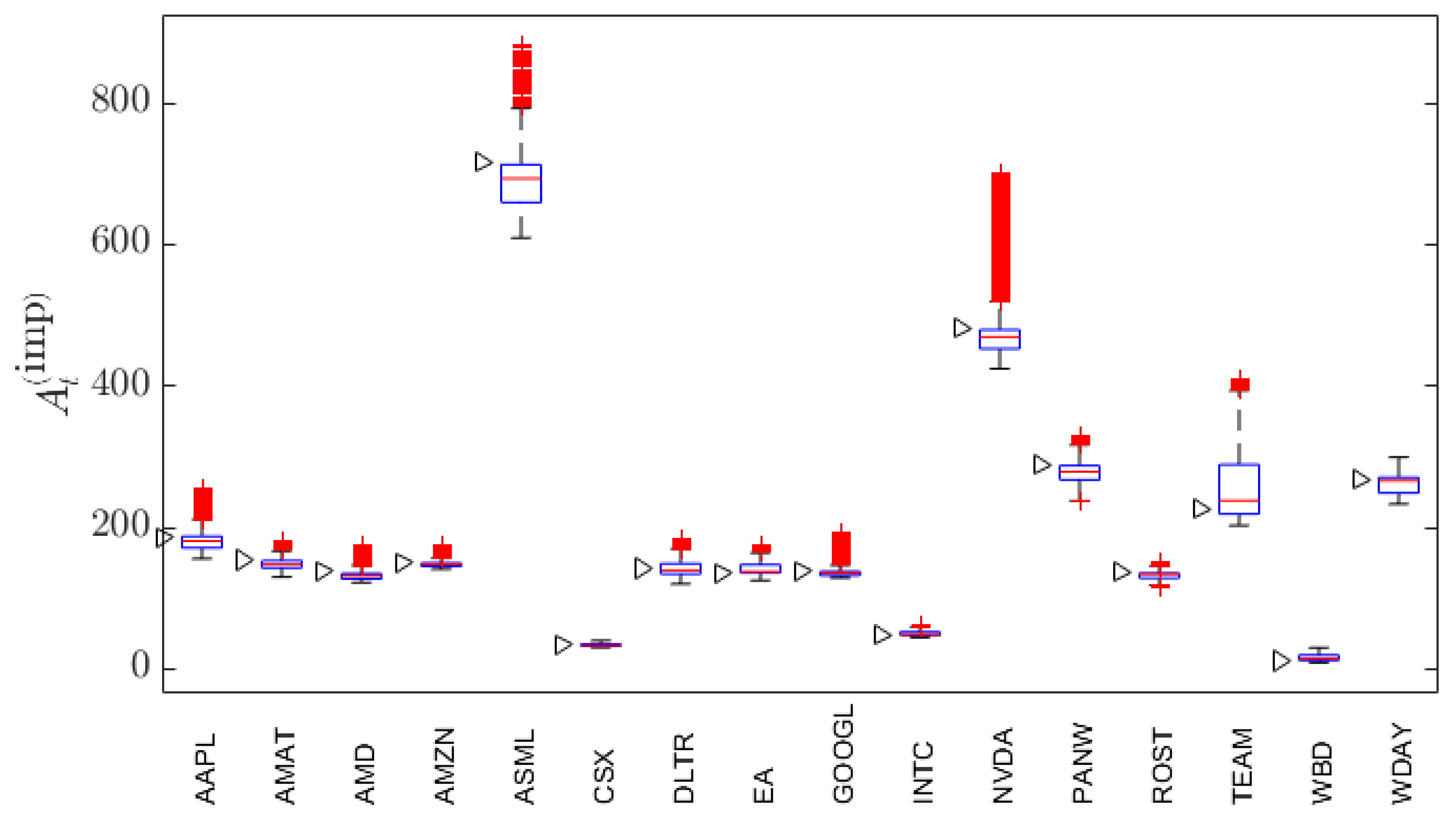

To summarize the information in

Appendix C and

Appendix D,

Figure 10 presents the box-whisker summaries of the distributions of

values for each of the 16 stocks. (The corresponding box-whisker summaries of the distributions of

values are given in

Figure A7.) Also indicated just to the left of each box-whisker summary is the financial spot price of the stock on 01/02/2024. For ease of reference, the financial spot prices on 01/02/2024 are listed in

Table A2. From the contour plots in

Figure A10 and

Figure A11, one can then ascertain over what region of

values option traders view the ESG valuation of the stock to be higher than its financial price. For EA, INTC, TEAM and WBD, spot traders have an implied ESG valuation that exceeds the spot price over most of the

region. For eight of the stocks (AAPL, AMAT, AMD, AMZN, ASML, CSX, NVDA, PANW), the implied ESG valuation exceeds the spot price over a triangular, out-of-the-money, shorter maturity time region as described above for AAPL. For the remaining four stocks, the implied ESG valuation exceeds the spot price over most of the out-of-the-money region. Thus, for 12 of the 16 stocks, option traders have in-the-money ESG valuations that are lower than the spot price.

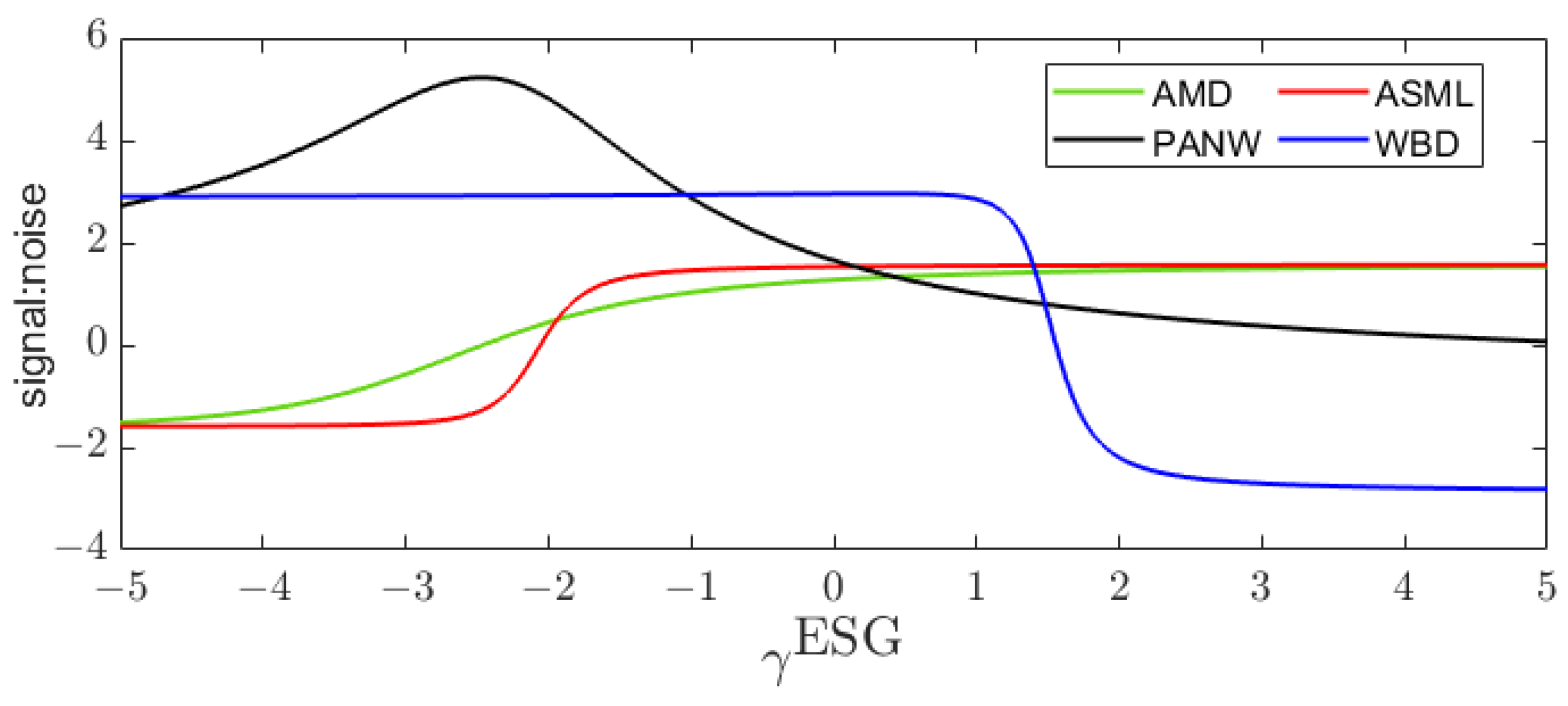

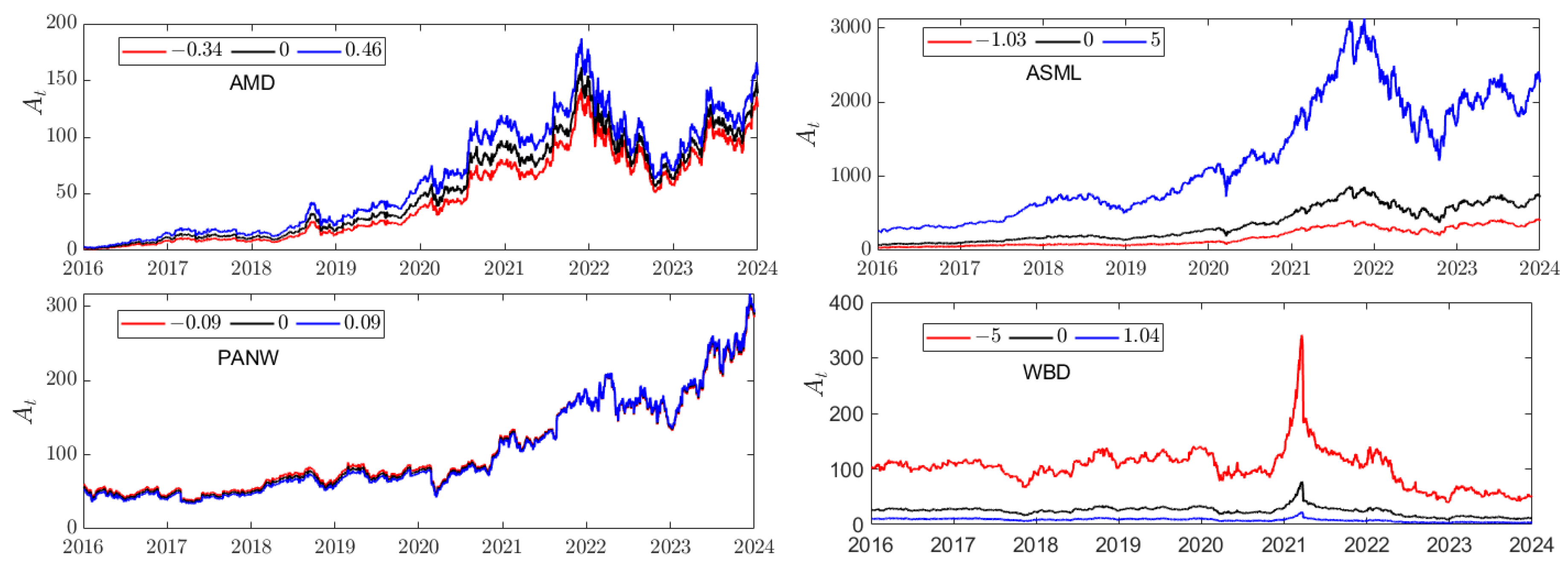

6. Trading Forward Contracts Utilizing Information on Asset Price Direction

[

22] extended BSM-based binomial option pricing theory to complete markets containing traders that have information on the stock price direction. We further extend that theory using the BBSM-based binomial option pricing in complete markets of

Section 3. For simplicity, we assume the parameters in the BBSM binomial model are constant:

,

,

,

,

, and

,

. As earlier, we continue to assume

is constant.

Let ℵ denote the trader (hedger) holding the short position in the option contract. Let denote the probability that information held by ℵ at time , , on the direction of stock price movement within any interval is correct. If , ℵ is an informed trader; if , ℵ is misinformed; and if , we refer to ℵ as a noisy trader. We assume ℵ is the only informed trader in a market of noisy traders; consequently, ℵ’s informed trading actions do not influence market prices.

In [

22], Shannon’s entropy [see e.g., [

32,

33] is used to quantify the amount of information

ℵ possesses. As with the price movement probability

of

Section 3,

is the probability governing a Bernoulli random variable

such that

. Then Shannon’s entropy is

, having maximum value

. [

22] defined

ℵ’s level of information as

25

where

We address the question of

ℵ’s potential gain from trading with an information level

. At any time

,

,

ℵ makes independent bets,

,

. Thus, the filtration (

11) needs to be augmented with the sequence of

ℵ’s independent bets:

Specifically, relying on the information on stock-price direction,

ℵ adopts a trading strategy involving forward contracts. For convenience, we label the two scenarios given by (

10) for the price of

:

: , resulting in w.p. ,

: , resulting in w.p. ,

where

and

are given by (

16) with constant coefficients. If at

,

ℵ believes that

will happen,

ℵ takes a long position

26 in

-forward contracts, for some

.

27 The forward contracts mature at

. If at

,

ℵ believes that

will happen, then

ℵ takes a short position in

-forward contracts

26:oppparty having maturity

.

[

25] developed the price of a forward contract under the BBSM model. Assuming there is no initial cost to enter into the forward contract and constant coefficients, the

T-forward price of

is

where the constant coefficient solution to (

2) is [

25], (A3)]

Evaluating (

44) using (

45) gives

for all

. Discretizing (

46) over the time interval

and assuming

, (

46) becomes

For notational brevity, define

.

Using (

10), conditionally on

, the payoff possibilities of

ℵ’s forward contract positions can be written

The conditional expected payoff is

with

and

given by (

16).

We write

where,

, for any finite value of

.

is referred to as

ℵ’s information intensity. Again assuming

,

28 Under the same assumption, the conditional variance of

ℵ’s payoff is

The instantaneous information ratio is then

As

is positive, the information ratio on the payoff of

ℵ’s strategy increases: as

ℵ’s information intensity increases, and when

.

29

To hedge the short position in the option,

ℵ executes the positions (

17), while simultaneously running the futures trading strategy. This leads to an enhanced price process for

ℵ, the dynamics of which can be expressed as:

,

. The price change of the process (

54) is

Conditionally on

, and using (

16),

It is in

ℵ’s interest to find the value of

which maximizes the conditional Markowitz’ expected utility function,

where

is

ℵ’s risk-aversion parameter. Using (

56),

is maximized for

Under the optimal value,

and the instantaneous conditional market price of risk for

ℵ is

If

ℵ had not traded futures on the information possessed, the trader’s instantaneous conditional market price of risk would have been the same as a noisy trader:

Thus,

futures trading results in an (optimized) dividend

yield over the time interval

determined by the solution of

Thus,

We note that, relative to a noisy trader,

Equality between the first and last terms in (

64) is obtained for

or

since, under these limits, all traders become aware of the direction of the price movement.

We investigate the dividend payout

as a function of

and

. From (

59) we note that

is a monotonic function of

having the limits

and

. Under the limit

, which corresponds to sufficiently small values of

or sufficiently large values of

,

which is always positive, increasing with

and decreasing as

increases. Under the limit

, which corresponds to sufficiently large values of

or sufficiently small values of

,

In this limit, the dividend payout is essentially independent of

.

7. Conclusion

Dynamic asset pricing based upon geometric Brownian motion [

7,

27] has had a tremendous’ impact on finance theory. While having had difficulty gaining acceptance, dynamic pricing based upon arithmetic Brownian motion [

6] has certain attractive features. The unified BBSM model of [

25] encompasses the strengths of both models. By adapting the BBSM framework to a model of ESG-adjusted asset valuation, we put the full strength of the BBSM model to practical use. Using an empirical data set of 16 stocks taken from the Nasdaq-100, based on call option prices for 01/02/2024 we have shown that, generally, option traders were implying ESG-adjusted prices that exceed the spot price in the out-of-the-money region, while in-the-money, ESG-adjusted prices were lower that the spot price. A follow-up study is required to determine how universal an observation this may be. It would be interesting to investigate call option prices issued during periods of bull and bear markets, and during market disruptions.

We have further extended this ESG-BBSM model to consider futures trading strategy accessible to a trader ℵ holding information on the direction of ESG-adjusted prices. It would be of interest to evaluate ℵ’s optimal dividend payout by, for example, projecting it forward on the binomial tree and computing an expected dividend at time . While this could be evaluated for a specific asset, using historical estimated values , , , , , , , and a spot price (with ), there is no historical information available for , while the parameters and are trader-dependent. Thus, estimates of an expected averate dividend payout at require an investigation of a three dimensional phase space - a fairly daunting prospect best left for a separate study.