Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

06 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

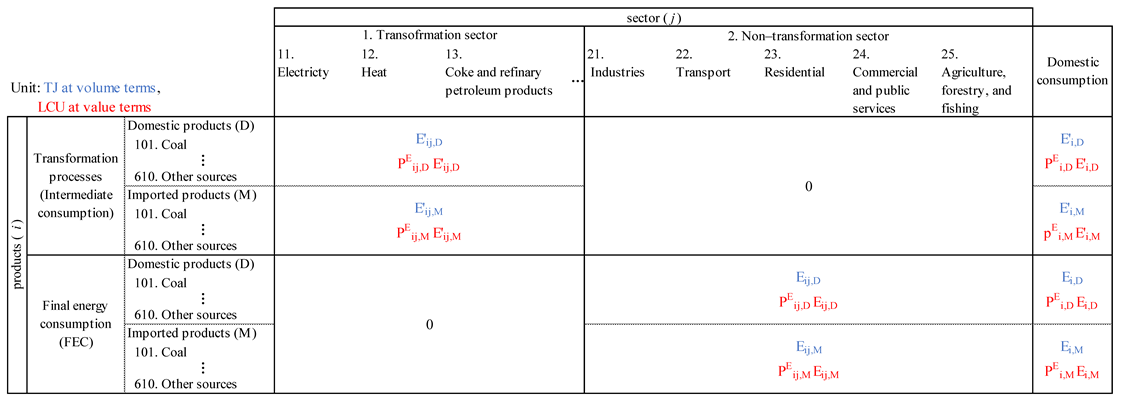

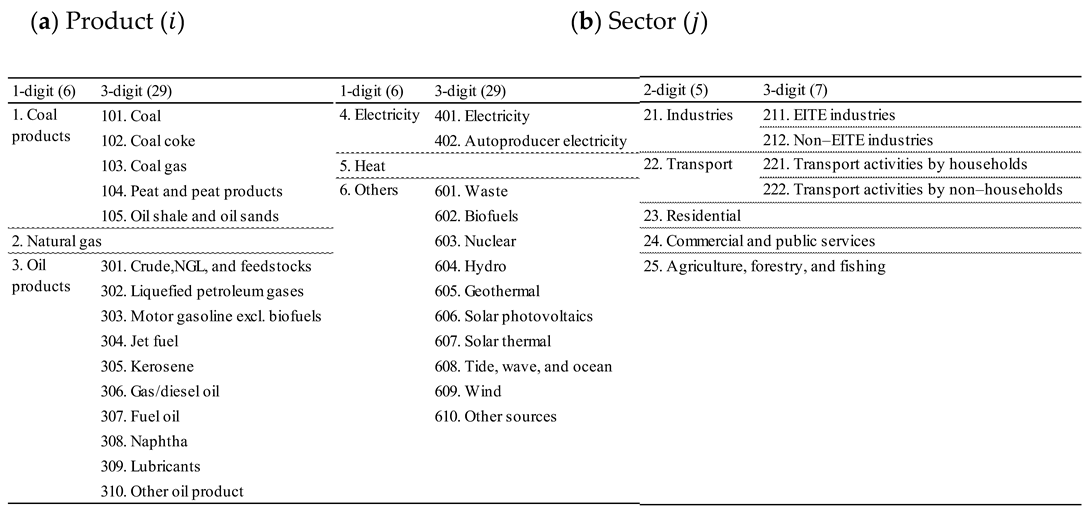

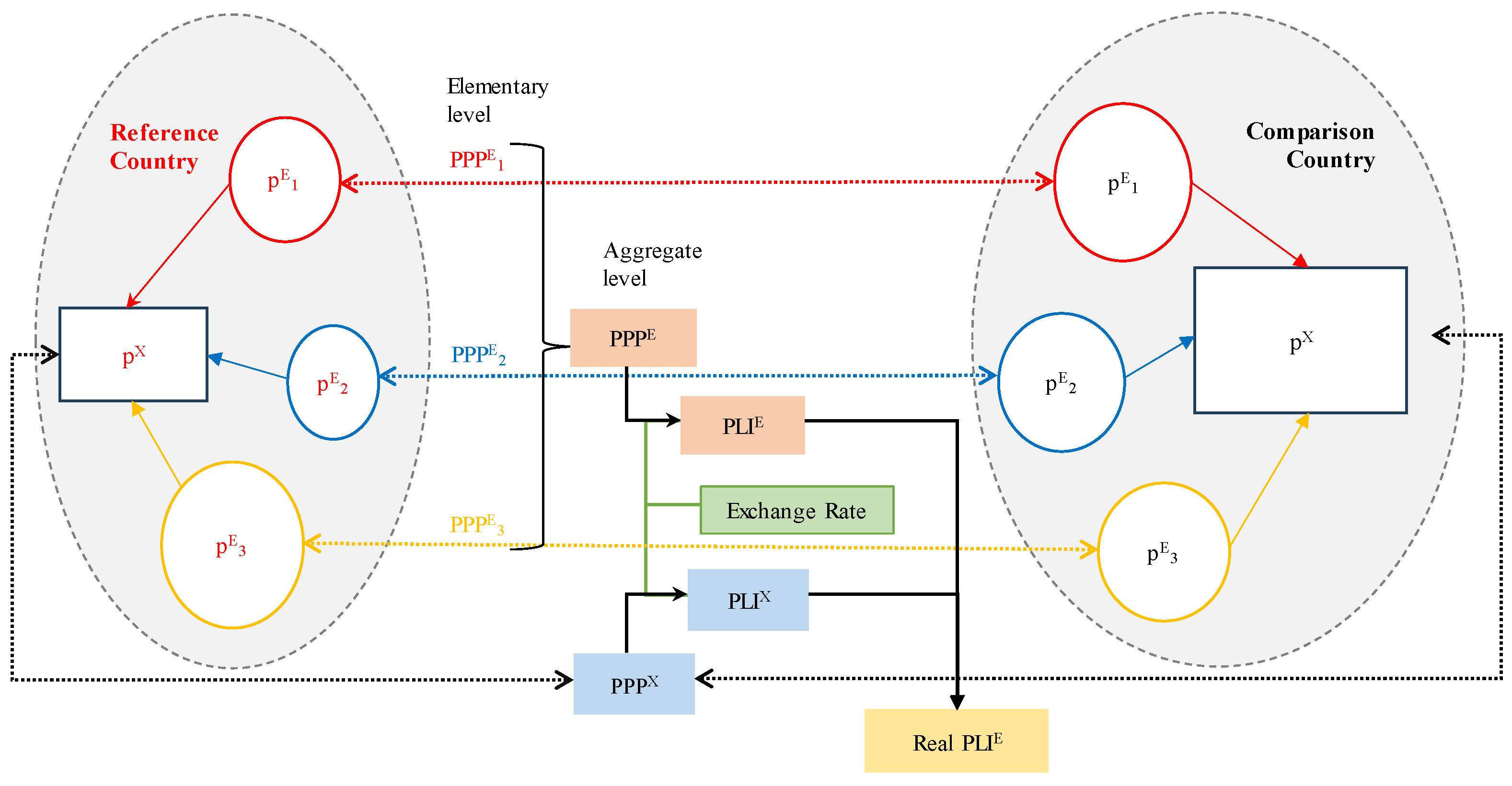

3. Measurement Framework

3.1. RUEC

3.2. Energy PPP

3.3. Energy PLI

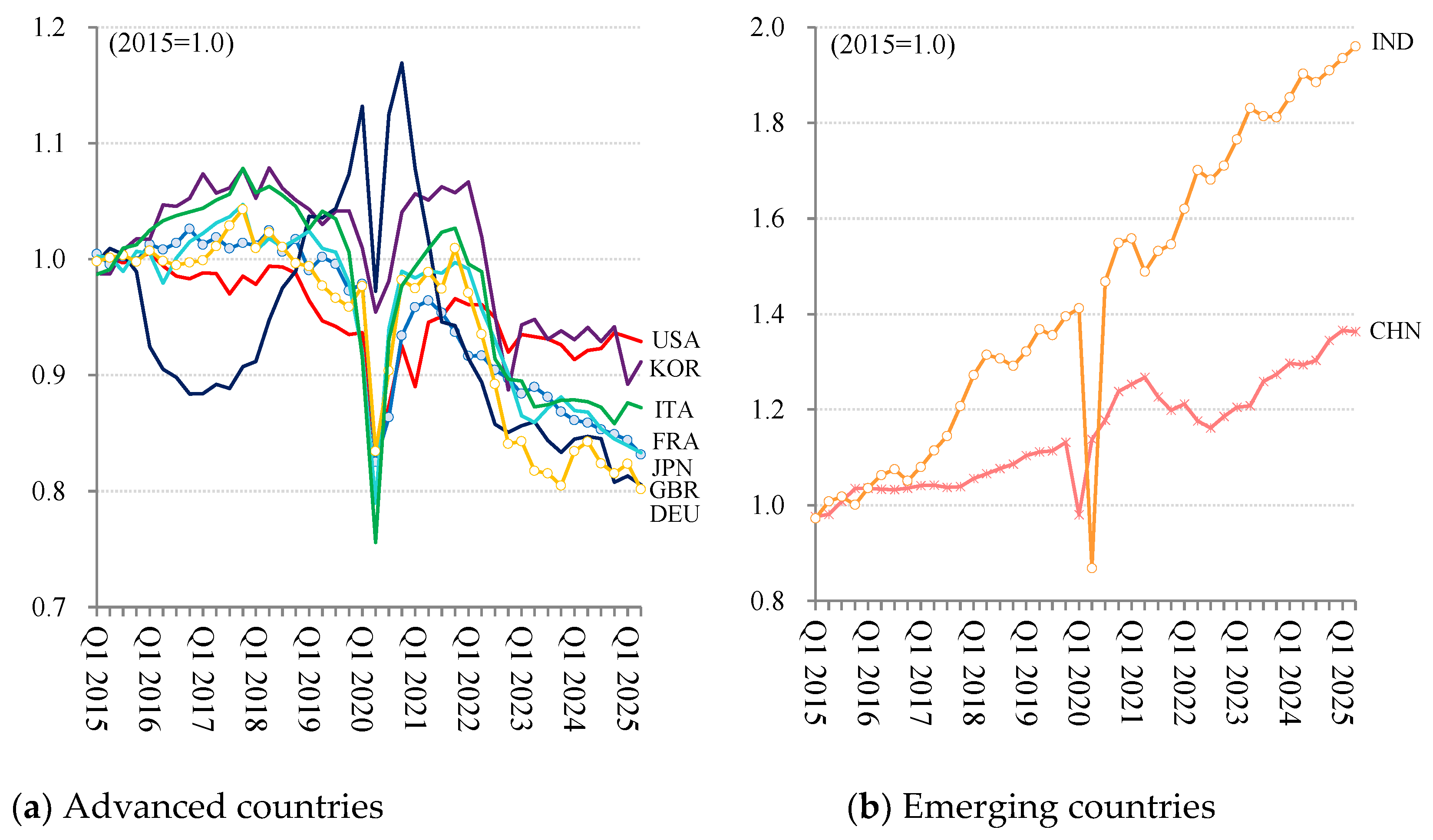

4. Results

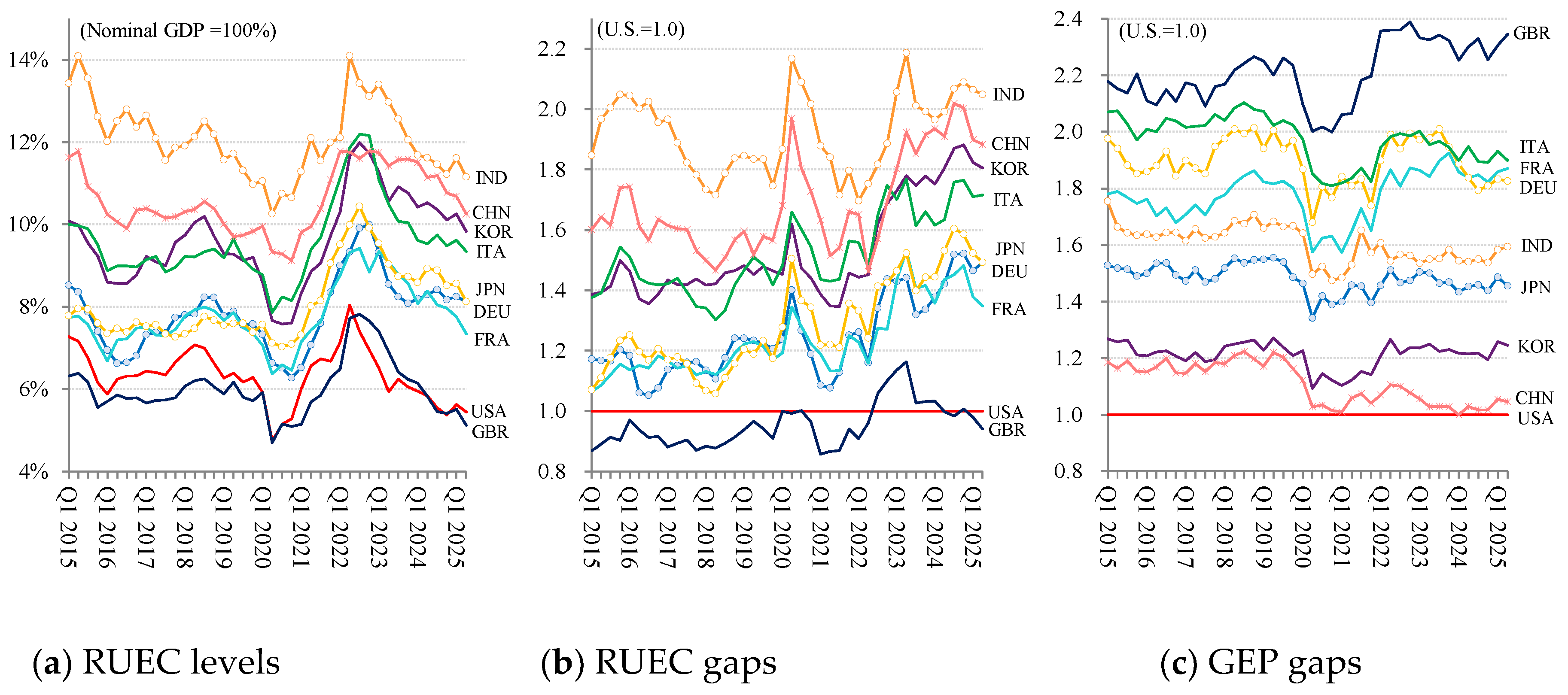

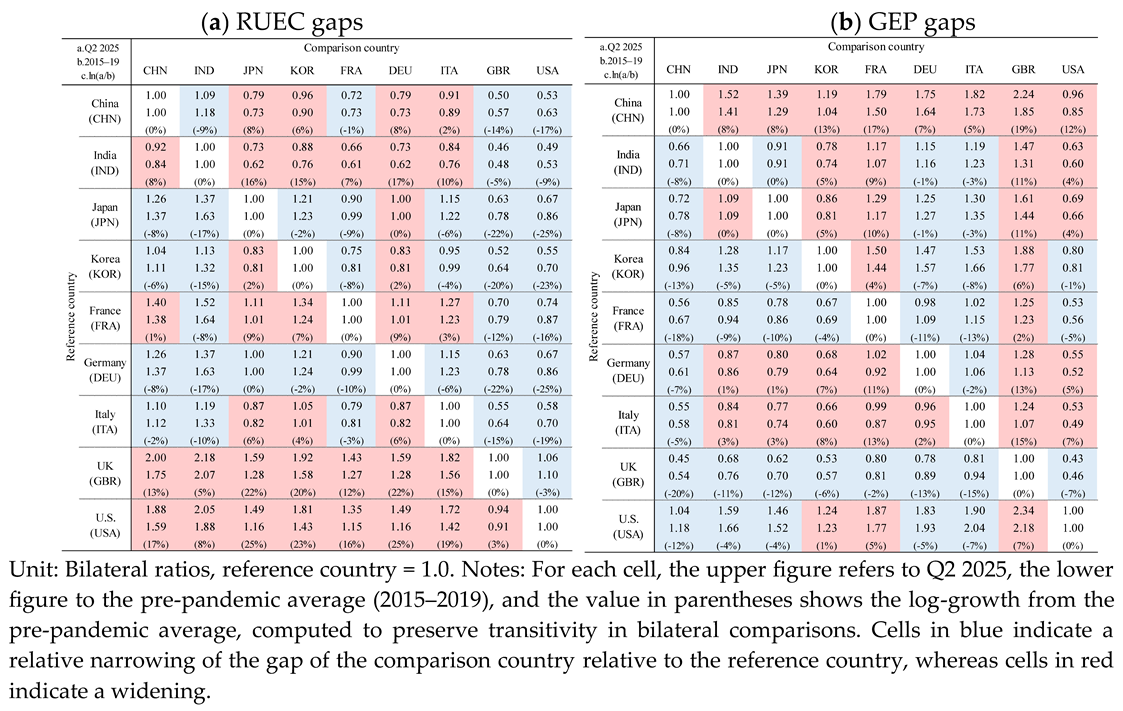

4.1. RUEC Gaps

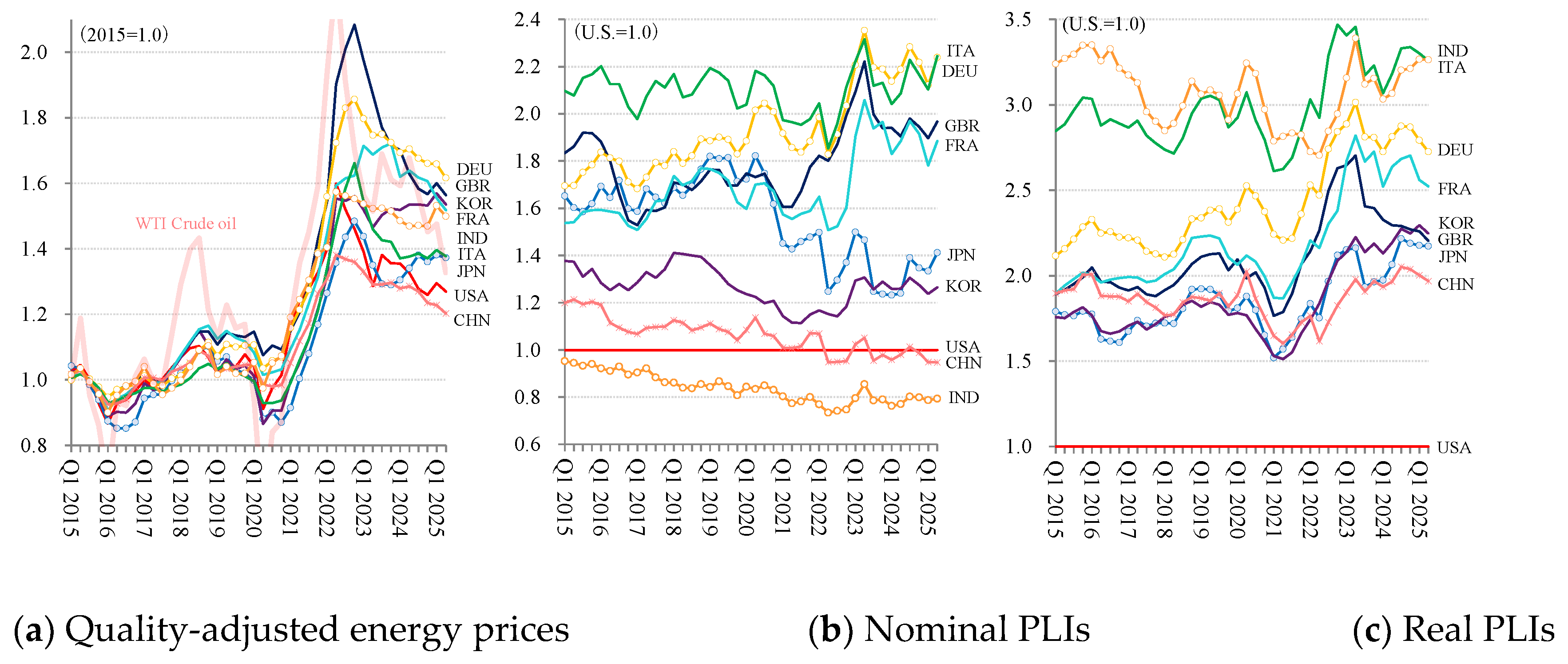

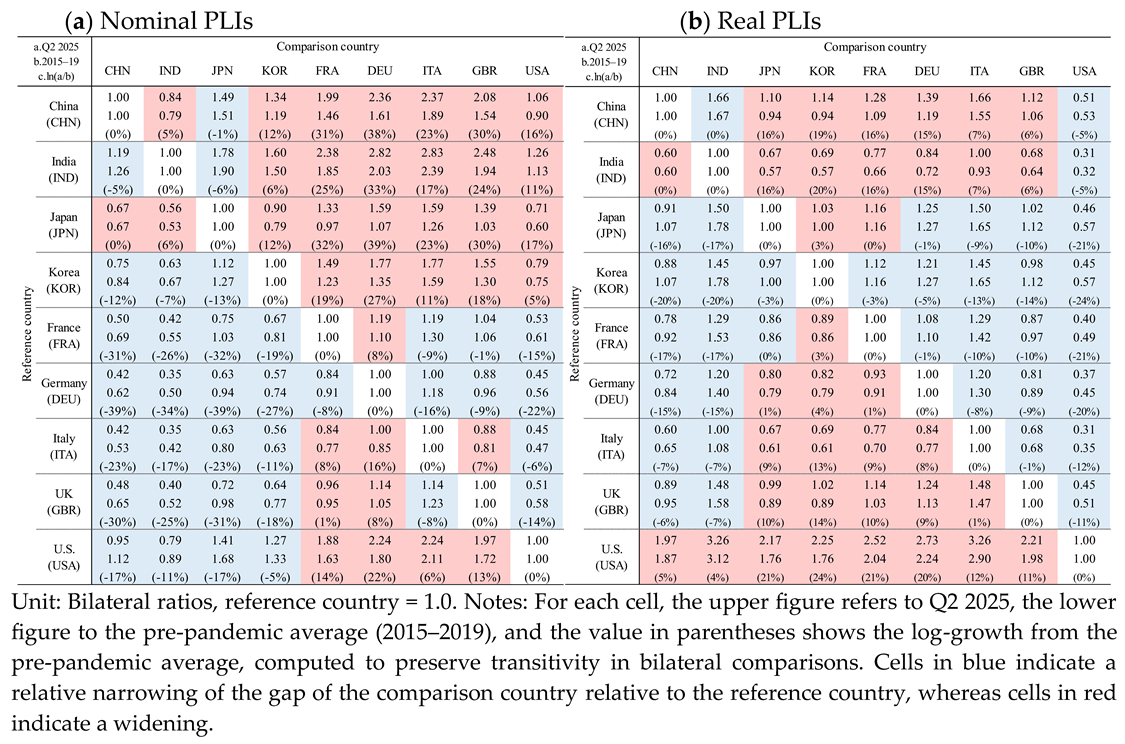

4.2. Real PLI

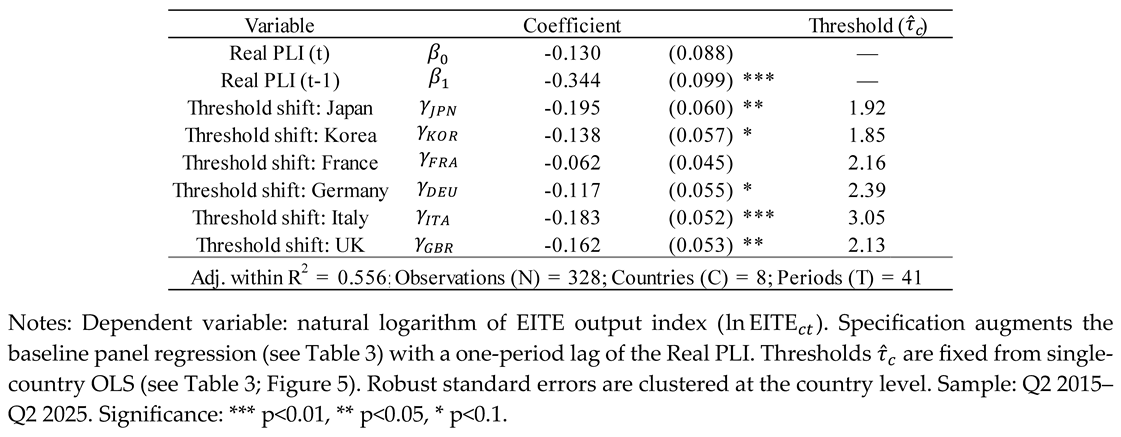

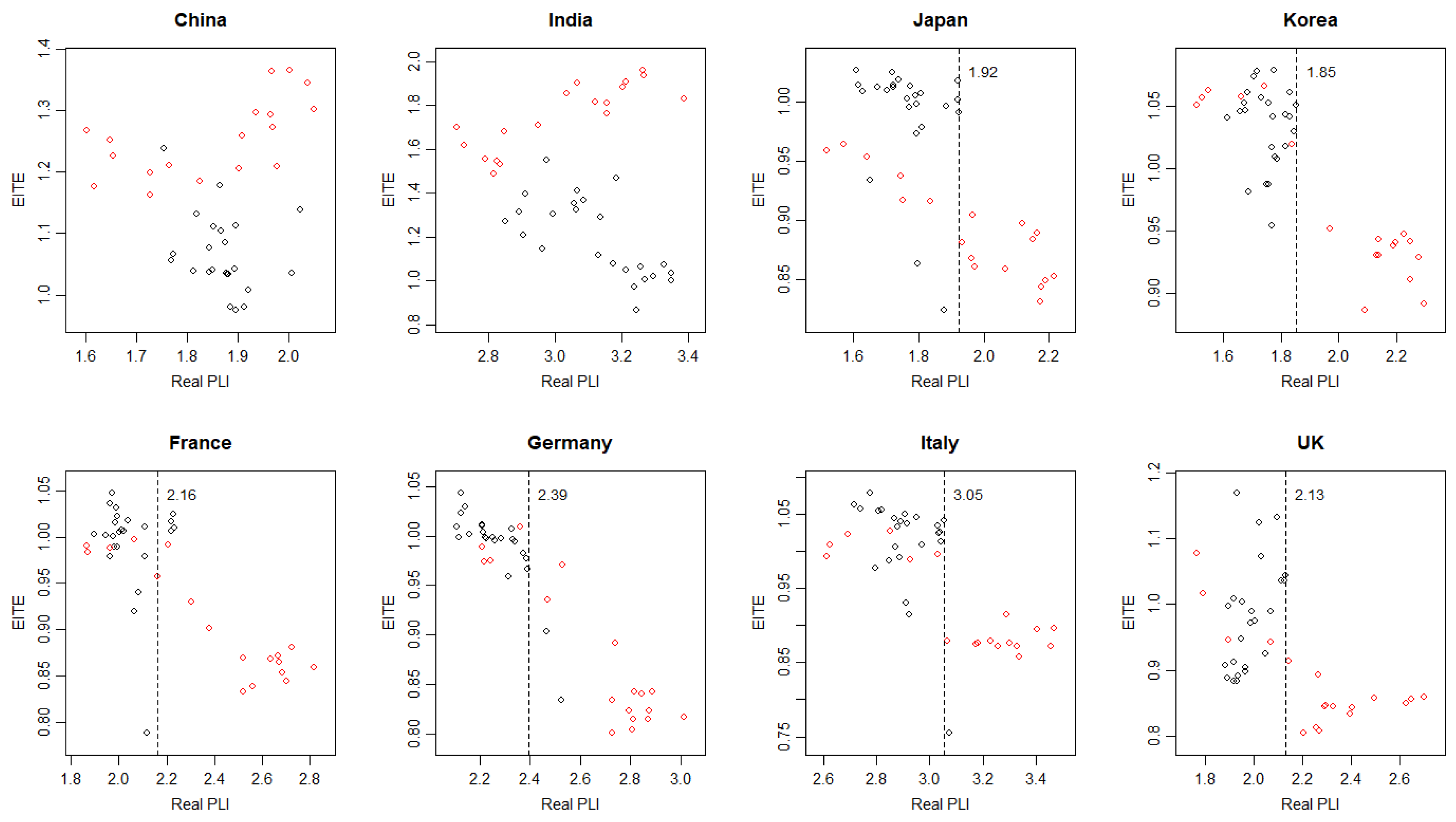

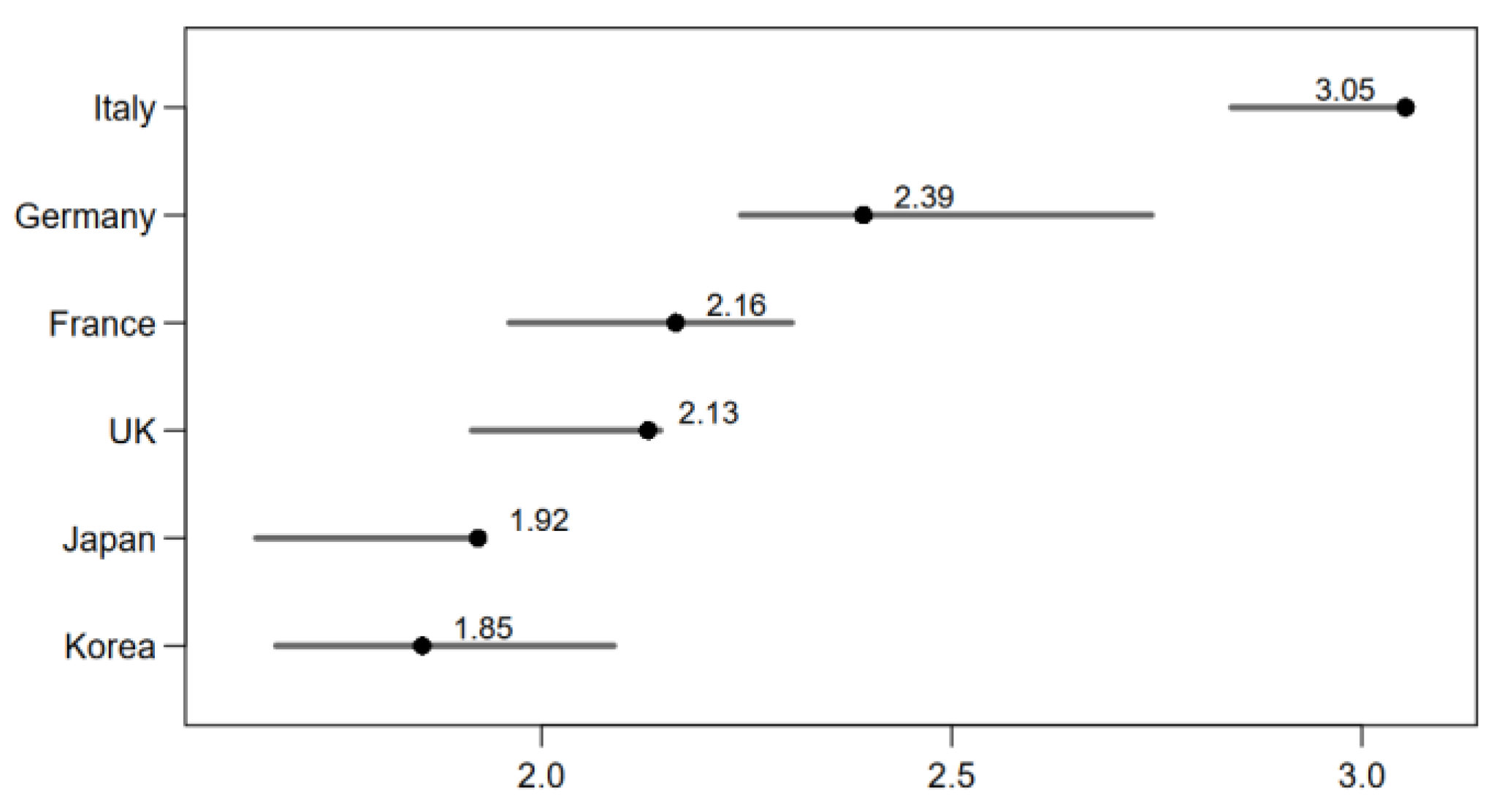

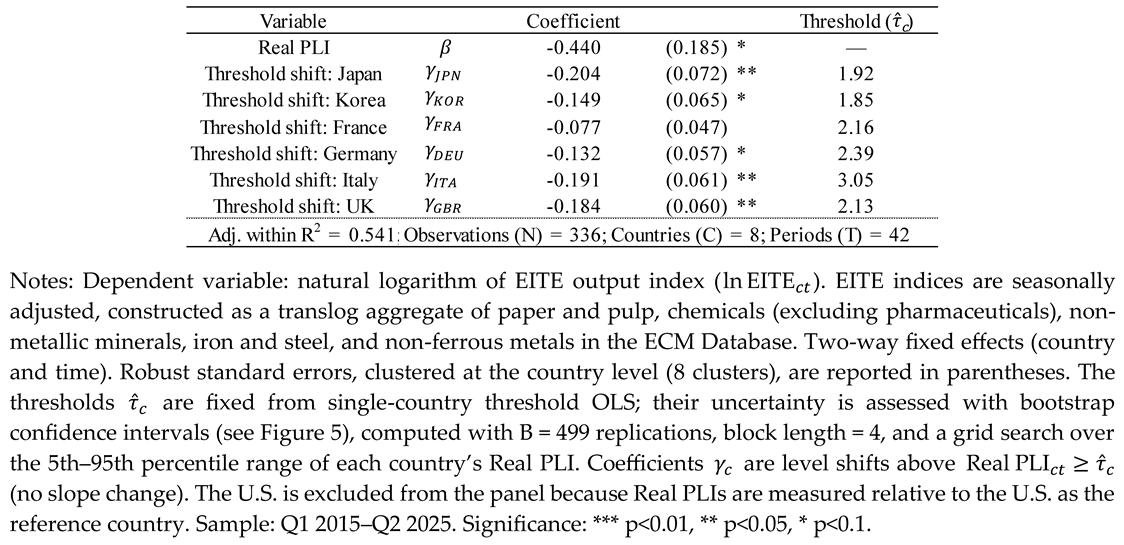

4.3. Threshold Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Global Governance

5.2. Industry Dynamics

5.3. Structural Policy Design

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EITE | Energy-intensive and trade-exposed |

| GEP | Gross energy productivity |

| PPP | Purchasing power parity |

| Real PLI | Real price level index for energy |

| RUEC | Real unit energy cost |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

Appendix B

Appendix B.1

Appendix B.2

References

- Stern, N. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Stern, N.; Duan, M.; Edenhofer, O.; Giraud, G.; Heal, G.M.; la Rovere, E.L.; Morris, A.; Moyer, E.; Pangestu, M.; Shukla, P.R.; Sokona, Y.; Winkler, H. Report of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Stern, N.; Stiglitz, J.E. Climate Change and Growth. Industrial and Corporate Change 2023, 32, 277–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-level Perspective and A Case-study. Research Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability Transitions: An Emerging Field of Research and Its Prospects. Research Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F.; Fünfschilling, L.; Hess, D.; Holtz, G.; Hyysalo, S.; Jenkins, K.; Kivimaa, P.; Martiskainen, M.; McMeekin, A.; Mühlemeier, M.S.; Nykvist, B.; Pel, B.; Raven, R.; Rohracher, H.; Sandén, B.; Schot, J.; Sovacool, B.; Turnheim, B.; Welch, D.; Wells, P. An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of The Art and Future Directions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechezleprêtre, A.; Sato, M. The Impacts of Environmental Regulations on Competitiveness. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 2017, 11, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löschel, A.; Lutz, B.J.; Managi, S. The Impacts of the EU ETS on Efficiency and Economic Performance– An Empirical Analysis for German Manufacturing Firms. Resource and Energy Economics 2019, 56, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiacchio, F.; De Santis, R.A.; Gunnella, V.; Lebastard, L. How Have Higher Energy Prices Affected Industrial Production and Imports? Economic Bulletin Boxes, European Central Bank: Frankfurt, Germany, 2023. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/economic-bulletin/focus/2023/html/ecb.ebbox202301_02~8d6f1214ae.en.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Jäger, P. Rustbelt Relics or Future Keystone? EU Policy for Energy-intensive Industries. Jacques Delors Centre: Berlin, Germany, 2023. Available online: https://www.delorscentre.eu/fileadmin/2_Research/1_About_our_research/2_Research_centres/6_Jacques_Delors_Centre/Publications/20231221_Jaeger_Industries.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Vogel, L.; Neuman, M.; Linz, S.; Calculation and Development of the New Production Index for Energy-Intensive Industrial Branches. WISTA–Scientific Journal 2023, 2. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Methods/WISTAScientificJournal/Downloads/production-index-energy-intensive-industrial-022023.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Saussay, A.; Sato, M. The Impact of Energy Prices on Industrial Investment Location: Evidence from Global Firm Level Data. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2024, 127, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draghi, M. The Future of European Competitiveness: A Competitiveness Strategy for Europe. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/97e481fd-2dc3-412d-be4c-f152a8232961_en (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- DIHK. Neue Wege für die Energiewende („Plan B“): Wissenschaftliche Studie im Auftrag der Deutschen Industrie- und Handelskammer [New Paths for the Energy Transition (“Plan B”): Scientific Study Commissioned by the Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce]. Deutsche Industrie- und Handelskammer: Berlin, Germany, 2025. Available online:. Available online: https://www.frontier-economics.com/media/u1vbsfop/frontier-dihk-energiewende-plan-b-03092025-stc-update-stc.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- WCED. Our Common Future (Brundtland Report); Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K. What Are We Doing Here? Analyzing Fifteen Years of Energy Scholarship and Proposing a Social Science Research Agenda. Energy Research & Social Science 2014, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, I.; Heindl, P. Price and Income Elasticities of Residential Energy Demand in Germany. Energy Policy 2017, 102, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S. Energy Poverty: (Dis)Assembling Europe's Infrastructural Divide; Palgrave Macmillan Cham: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Volodzkiene, L.; Streimikiene, D. Integrating Energy Justice and Economic Realities through Insights on Energy Expenditures, Inequality, and Renewable Energy Attitudes. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 27067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shejale, S.; Zhan, M.X.; Sahakian, M.; Aleksieva, R.; Biresselioglu, M.E.; Bogdanova, V.; Cardone, B.; Epp, J.; Kirchler, B.; Kollmann, A.; Liste, L.; Massullo, C.; Schibel, K. Participation as a Pathway to Procedural Justice: A Review of Energy Initiatives across Eight European Countries. Energy Research & Social Science 2025, 122, 103982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Energy Economic Developments in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Energy Prices and Costs in Europe. Commission Staff Working Document, 2019. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2019-01/swd_-_v5_text_6_-_part_1_of_4_0.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Faiella, I.; Mistretta, A. Energy Costs and Competitiveness in Europe. Bank of Italy Temi di Discussione 2020, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenegger, O.; Löschel, A.; Baikowski, M.; Lingens, J. Energy Costs in Germany and Europe: An Assessment Based on a (Total Real Unit) Energy Cost Accounting Framework. Energy Policy 2017, 104, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenegger, O. What Drives Total Real Unit Energy Costs Globally? A Novel LMDI Decomposition Approach. Applied Energy 2020, 261, 114340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K. Energy Productivity and Economic Growth: Experiences of the Japanese Industries, 1955–2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNIDO. Industrial Development Report 2020: Industrializing in the Digital Age; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, C.; Simsek, Y.; Mercure, J.-F.; Fragkos, P.; Lefèvre, J.; Le Gallic, T.; Fragkiadakis, K.; Paroussos, L.; Fragkiadakis, D.; Leblanc, F.; Nijsse, F. Structural Change and Socio-Economic Disparities in a Net Zero Transition. Economic Systems Research 2024, 36, 607–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Purchasing Power Parities and the Size of World Economies: Results from the International Comparison Program 2021; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/icp/brief/ICP2021 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Nomura, K.; Miyagawa, K.; Samuels, J.D. Benchmark 2011 Integrated Estimates of the Japan–US Price Level Index for Industry Outputs. In Measuring Economic Growth and Productivity: Foundations, KLEMS Production Models, and Extensions; Fraumeni, B.M., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 251–281. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson, D.W.; Nomura, K.; Samuels, J.D. A Half Century of Trans-Pacific Competition: Price Level Indices and Productivity Gaps for Japanese and U.S. In dustries, 1955–2012. In The World Economy: Growth or Stagnation? Jorgenson, D.W.; Fukao, K., Timmer, M.P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 469–507. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Energy Prices. International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/energy-prices (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Nomura, K.; Inaba, S.; Jisshitsuteki na Enerugī Kosuto Futan ni Kansuru Kōhindo Shihyō no Kaihatsu: Getsuji RUEC to Sono Henka Yōin [Development of High-Frequency Indicators of Real Unit Energy Cost in Japan]. RCGW Discussion Paper 2023, 68. Available online: https://www.dbj.jp/ricf/pdf/research/DBJ_RCGW_DP68.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Nomura, K.; Inaba, S.; Post-Pandemic Surges of Real Unit Energy Costs in Eight Industrialized Countries. RCGW Discussion Paper 2024, 70. Available online: https://www.dbj.jp/ricf/pdf/research/DBJ_RCGW_DP70.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Nomura, K.; Inaba, S. Posuto Pandemikku no Enerugī Kakaku Kōtō to Jisshitsu Kakusa Kakudai—Shuyō Nanaka Koku no Hikaku Bunseki [Energy Price Surge and Widening Real Price Differentials in the Post-Pandemic Era: A Comparative Analysis of Seven Major Countries]. KEO Discussion Paper 2025, 185. [Google Scholar]

- APO. APO Productivity Databook 2025; Asian Productivity Organization, Keio University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, B.E. Threshold Effects in Non-dynamic Panels: Estimation, Testing, and Inference. Journal of Econometrics 1999, 93, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, A.O. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).