1. Introduction

The past decade has been marked by recurring economic and energy crises that have reshaped the priorities of both policymakers and researchers. The volatility of global energy markets, driven by geopolitical conflicts, supply disruptions, and rapid technological shifts, has underscored the fragility of existing systems and the urgency of sustainable alternatives. Within the European Union, the energy transition has become both a strategic objective and a necessity, encapsulated in flagship initiatives such as the European Green Deal and REPowerEU. These frameworks aim to accelerate decarbonization, reduce dependency on fossil fuel imports, and foster energy resilience across member states. However, the transition is neither uniform nor without challenges, as countries face diverse structural conditions, policy capacities, and resource endowments.

Romania and Spain represent two illustrative cases in this regard. Spain has established itself as a frontrunner in renewable energy deployment, particularly in solar and wind power, leveraging its natural potential and proactive policy environment. At the same time, it has faced persistent challenges linked to the volatility of electricity prices and reliance on external gas imports (European Commission, 2022). Romania, by contrast, relies on a balanced energy mix, with substantial contributions from nuclear and hydropower (Savu, 2020), yet its transition toward renewables has been slower, constrained by infrastructural and investment limitations (Popescu et al., 2021). Both countries thus exemplify distinct pathways within the broader EU effort to ensure energy security and sustainability under conditions of economic turbulence .

The objective of this paper is to analyze comparatively how Romania and Spain address the intertwined challenges of energy security and the green transition in times of global economic turmoil. By situating the two national experiences within the context of European policy frameworks and recent crises, the study seeks to identify complementarities, vulnerabilities, and lessons that can inform both national strategies and EU-wide policymaking. In doing so, the paper contributes to the ongoing debate on how heterogeneous member states can strengthen their resilience and accelerate progress toward a sustainable and secure European energy system.

2. Literature Review

The intersection between energy crises, global economic turmoil, and the pursuit of a green transition has become one of the most intensely debated topics in recent academic and policy-oriented research. Historically, energy shocks have had profound implications for economic growth, inflation, and international trade, as evidenced by the oil crises of the 1970s and the more recent volatility in natural gas prices (Hamilton, 2013; Stern, 2014). In the European Union, these vulnerabilities have been magnified by geopolitical dependencies, particularly in relation to Russian gas imports, and by the urgency of aligning national economies with ambitious climate targets (European Commission, 2020; Tagliapietra, Zachmann & Edenhofer, 2020). Against this backdrop, the scientific literature increasingly highlights the need to analyze energy systems not only as technical infrastructures but also as socio-economic and geopolitical constructs that shape national resilience in times of crisis (Geels et al., 2017; Sovacool, 2021; Popescu, Savu & Chisăliță, 2021).

Global perspectives on energy crises and green transitions - the global literature emphasizes that energy security and green transition are not mutually exclusive but interdependent challenges. On the one hand, studies underscore that decarbonization reduces long-term exposure to fossil fuel price volatility, yet in the short term, the transition process can generate significant instability in energy markets (Abánades, 2023; Aklin & Urpelainen, 2018; International Energy Agency, 2021). The literature also points to the uneven distribution of costs and benefits: advanced economies tend to have more resources to invest in renewable infrastructures, while emerging economies face trade-offs between affordability, sustainability, and growth (Ajanovic & Haas, 2021; Goldthau & Sitter, 2020). From a macroeconomic perspective, energy transitions have been associated with structural shifts in employment, industrial competitiveness, and fiscal stability (Petrariu et al., 2021; Steffen et al., 2020)

The COVID-19 pandemic further reshaped this debate. Several studies have shown that recovery packages were designed as opportunities to “build back greener,” yet the simultaneous resurgence of fossil fuel demand has constrained the pace of transition (Steffen et al., 2020; Newell & Simms, 2020). More recently, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 triggered a global reconfiguration of energy markets. A growing body of research analyzes how Europe’s sudden reduction of Russian imports created both vulnerabilities and incentives for accelerated investment in renewables and diversification of supply routes (Biresselioglu, Demir & Soytaş, 2022; Şerban & Mureșan, 2021).

European Union frameworks and scholarly debates - within the EU, the European Green Deal (2019) and REPowerEU (2022) are central policy instruments that have generated extensive academic analysis. Scholars have examined their implications for energy market integration, financing, and governance (Claeys, Tagliapietra & Zachmann, 2021; Tagliapietra, Zachmann & Edenhofer, 2020). The Green Deal sets the overarching target of climate neutrality by 2050, while REPowerEU emphasizes diversification and accelerated renewable deployment as responses to energy insecurity (European Commission, 2020; European Commission, 2022). Comparative studies stress that the implementation of these frameworks is highly uneven: northern and western member states tend to advance more rapidly in renewable penetration, while southern and eastern states face higher structural constraints (Eyl-Mazzega & Mathieu, 2022).

Spain is frequently cited as a frontrunner in the renewable transition. Literature highlights the significant expansion of solar photovoltaic and wind capacity since the 2000s, supported by generous feed-in tariffs and proactive regulatory reforms (Arribas et al., 2025; del Río & Mir-Artigues, 2019; Gavurova et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the Spanish case also illustrates the challenges of policy volatility: early incentives led to rapid deployment but also to market distortions and tariff deficits, which subsequently required corrective measures (Ciarreta, Espinosa & Pizarro-Irizar, 2014; Curto-Rodríguez et al., 2025; Esfandiary Abdolmaleki et al., 2023). Recent scholarship notes that Spain has regained momentum through the National Energy and Climate Plan 2021–2030, which prioritizes renewables while addressing electricity price volatility and integration with EU energy markets (Carvalho, Ferreiro & Gomez, 2021; de Juan et al., 2025; Dufo-López et al., 2024). Further studies have expanded this perspective by analyzing strategic photovoltaic projects, the integration of solar power into desalination processes, and the land-use implications of large-scale PV installations (Mănescu, D.C.,2010; Dufo-López, 2025; Martínez-Medina, R., 2025; Martínez-Medina, M.À., 2024). In addition, cross-country analyses and regional rankings underscore Spain’s distinctive position within the EU, highlighting both its role as a renewable leader and the disparities among its autonomous communities (Badau et al., 2025; Carfora, Scandurra & Thomas, 2022).

Romania has been less prominent in the international literature, although recent studies have examined its reliance on nuclear and hydropower as stabilizing pillars of the national energy mix (Horobet et al., 2021). Despite significant renewable potential in wind and solar, progress has been constrained by infrastructural bottlenecks, underinvestment, and regulatory uncertainty (Badea, Călin & Dincă, 2021). Strategic analyses further note Romania’s positioning in the Black Sea region and its domestic gas reserves, which could support resilience but raise questions about the long-term compatibility of gas with decarbonization goals (Dinu et al., 2020). At the same time, policy-oriented research emphasizes both challenges and opportunities for Romania to accelerate its transition, particularly by aligning national strategies with European initiatives and exploiting renewable capacity more effectively (Butum et al., 2020). Recent analyses underline both the structural challenges and the potential pathways for Romania to align more effectively with EU objectives, highlighting the need for accelerated renewable investment and better integration into comparative European frameworks (Chisăliță, 2022). Comparative assessments across the EU further highlight Romania’s dual role as both a laggard in renewable deployment and a state with significant untapped potential to strengthen resilience in future transitions (Şerban & Mureșan, 2021; Savu, 2020).

Comparative perspectives: Romania and Spain in EU context -Comparative perspectives on Romania and Spain within the EU context remain relatively scarce, yet existing studies on European energy diversity suggest that their trajectories embody contrasting but complementary pathways. Spain represents the archetype of a high-renewable system, ambitious in decarbonization but vulnerable to external shocks due to reliance on liquefied natural gas and volatile electricity prices. Romania, conversely, illustrates a more conservative model, relying on legacy infrastructure such as nuclear and hydro that provide stability but at the cost of slower renewable uptake and persistently higher carbon intensity in fossil-based sectors (Goldthau & Sitter, 2020). Broader comparative analyses emphasize that such heterogeneity is a structural feature of the European energy transition, with member states advancing at different speeds and through distinct technological choices (Steffen et al., 2020; Mănescu, D.C.,2015; Geels et al., 2017). At the same time, scholarship has underlined the importance of integrating these diverse models to strengthen EU resilience, while also acknowledging the uneven distribution of costs and social impacts across regions (Carfora, Scandurra & Thomas, 2022).

The gap in the literature is particularly visible in three areas. First, there is limited research on how Spain’s renewable leadership coexists with systemic vulnerabilities in gas supply—most studies celebrate its successes without sufficiently addressing its fragilities. Second, Romania’s nuclear-hydro mix is acknowledged but not systematically analyzed as a potential model of resilience in times of global turmoil (Schwanen & Sorrell, 2017). Third, very few works adopt a bilateral comparative lens that situates Romania and Spain within a shared analytical framework, despite their strategic positions in southern and eastern Europe. Addressing these gaps is crucial for identifying complementarities that can inform EU-wide policies (Şerban & Mureșan, 2021; Mănescu, D.C., 2025; Egli, Pahle & Schmidt, 2020)

Toward a synthesis - the novelty of the present study lies precisely in bridging these gaps. By synthesizing empirical indicators with policy debates, this article offers a comparative framework that highlights both vulnerabilities and strengths of the Romanian and Spanish models. Unlike prior research, which tends to focus on either frontrunners like Spain or underrepresented eastern states like Romania, this paper juxtaposes the two in order to extract cross-country lessons. The added value resides in identifying how complementary trajectories—renewable leadership in Spain, nuclear-hydro resilience in Romania—can jointly contribute to strengthening EU energy security and advancing the green transition under conditions of economic turmoil. In doing so, the study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of heterogeneity within the EU and underscores the importance of policy transfer and mutual learning in addressing one of the most pressing challenges of our time.

3. Research Methodology

The methodological design of this paper aims to provide a comparative and integrative analysis of the energy transition trajectories of Romania and Spain under the broader context of global economic turmoil. The research seeks to operationalize the complex interplay between energy security, renewable adoption, and macroeconomic stability, thereby offering insights into the capacity of European Union member states to adapt to both external shocks and long-term sustainability imperatives.

3.1. Research Questions and Objectives

The central research question guiding this study is:

In order to operationalize this question, the following sub-questions are addressed:

What are the structural characteristics of the Romanian and Spanish energy systems, and how have they evolved over the past decade?

To what extent have renewable energy investments altered the dependency profiles and resilience of the two countries?

How do national policy frameworks interact with European initiatives such as the Green Deal and REPowerEU in shaping the pace and stability of the transition?

What complementarities and lessons can be derived from comparing the two models for EU-level policy design?

The objective of the study is to develop an evidence-based comparative framework that situates Romania and Spain within the broader European debate, while highlighting vulnerabilities, opportunities, and potential pathways for mutual learning.

3.2. Research Hypotheses

Although primarily exploratory, the study advances the following working hypotheses:

H1: Spain’s leadership in renewable deployment has increased decarbonization but also heightened exposure to supply volatility due to reliance on external gas imports.

H2: Romania’s nuclear-hydro balance provides greater short-term stability but slows down the pace of renewable adoption and limits integration with EU climate objectives.

H3: A comparative analysis reveals complementarities between the two models that can inform more resilient EU energy strategies.

3.3. Research Methods

The research design follows a comparative case study approach, integrating both quantitative and qualitative components.

Design: Descriptive, side-by-side comparison of Romania and Spain over 2010–2024 (2024 preliminary), aimed at a clear, data-driven narrative rather than causal inference.

Data sources: The analysis draws on secondary data from authoritative sources including Eurostat, the International Energy Agency (IEA), World Bank Development Indicators, and national statistical offices. Reports from the European Commission (notably on the Green Deal and REPowerEU) are also incorporated for contextual understanding.

Time frame: The empirical analysis covers the period 2010–2024, capturing long-term trends and the impact of recent crises (COVID-19 pandemic, 2022–2023 energy price shocks).

-

Indicators: The study evaluates a set of core indicators reflecting energy security and transition dynamics:

- o

Energy mix composition (fossil fuels, renewables, nuclear, hydro)

- o

Energy import dependency (% of total consumption)

- o

Installed renewable capacity (MW, % of total generation)

- o

Carbon intensity of energy supply (CO₂ emissions per unit of energy consumed)

- o

Electricity price volatility (€/MWh, household and industrial consumers)

- o

Investment flows in renewable energy (EUR, % of GDP)

Analytical techniques: Descriptive statistics are used to highlight differences in energy structures and trajectories. Trend analysis is applied to capture the evolution of indicators over time. Comparative policy analysis is conducted by examining national strategies alongside EU-level frameworks. Cross-case synthesis is employed to identify complementarities and policy lessons.

Data Treatment and Validation - to ensure comparability between Romania and Spain, all indicators were standardized using common units of measurement as reported by Eurostat, the IEA, and the World Bank. For energy investments, values expressed in national currency were converted into constant 2020 euros and scaled as a percentage of GDP, which allowed for a balanced assessment of the relative weight of renewable investments across countries and over time. Indicators such as energy import dependency and carbon intensity were cross-checked with multiple sources to minimize inconsistencies in reporting. In addition, time-series data were examined for structural breaks corresponding to major crises (e.g., 2008 financial crisis, COVID-19 pandemic, 2022 energy price shocks), which enabled the validation of trends against known macroeconomic and geopolitical events. The hypotheses were assessed through a triangulation of evidence, combining statistical evolution of indicators with qualitative interpretations of policy frameworks, thereby strengthening the robustness of the findings.

3.4. Methodological Rationale

The rationale for adopting a comparative case study design rests on the premise that Romania and Spain illustrate two divergent yet complementary models within the EU, which makes them particularly suitable for exploring resilience under global economic turbulence. The case study approach enables the integration of country-specific features, such as Spain’s regulatory innovations in renewables and Romania’s reliance on nuclear and hydropower, into a common analytical framework that highlights both contrasts and complementarities. This method allows for a nuanced assessment that would not be possible with purely cross-sectional or large-N approaches, where country-level specificities tend to be obscured.

Equally important, the selection of indicators was guided by their ability to capture both structural and dynamic aspects of energy systems. Metrics such as energy import dependency and carbon intensity offer insight into systemic vulnerability and environmental performance, while renewable investment flows and electricity price volatility reflect the economic and social dimensions of the transition. The chosen indicators therefore provide a balanced representation of the multiple pressures shaping energy security and sustainability. Furthermore, triangulation of evidence—combining descriptive statistics with qualitative policy analysis—strengthens internal validity by ensuring that observed trends can be linked to institutional and regulatory contexts rather than being interpreted in isolation. This integrated rationale aligns with established methodological recommendations for research on energy transitions, where complexity demands multi-perspective approaches that acknowledge uncertainty while enhancing explanatory depth.

3.5. Limitations

The methodology is subject to certain limitations. First, the reliance on secondary data implies potential inconsistencies in reporting standards between Romania and Spain, as well as time lags in official statistics. Second, the focus on two countries inevitably constrains generalizability, though the aim is not to produce universally applicable conclusions but to derive contextual lessons. Third, while the period 2010–2024 captures major shocks and reforms, longer-term dynamics may require additional investigation beyond the scope of this paper.

Beyond the general limitations of relying on secondary data, specific constraints are associated with the indicators employed. Energy import dependency, for example, may overstate vulnerability in cases where diversified import routes exist, while carbon intensity can be influenced not only by the structure of energy generation but also by fluctuations in economic activity. Similarly, investment data may not fully capture informal or decentralized initiatives, particularly in the residential sector. Moreover, cross-country comparisons risk obscuring domestic particularities, such as regional disparities within Spain or the role of state-owned enterprises in Romania. Although triangulation mitigates some of these challenges, the interpretation of results must account for the fact that indicators provide approximations rather than absolute measures of resilience or sustainability.

4. Results and Discussion

Energy transitions are rarely linear processes; they unfold through the interplay of technological advances, market signals, and political choices, all of which become magnified in times of economic turbulence. Crises expose the fragility of established systems while also accelerating structural change, forcing countries to reassess their vulnerabilities and to reconfigure strategic priorities. Within the European Union, the experiences of Spain and Romania offer two contrasting vantage points on this process. Spain, with its early commitment to solar and wind power, embodies the opportunities and risks of a rapid renewable push in a liberalized market environment. Romania, anchored in nuclear and hydropower stability, illustrates the advantages of legacy infrastructure but also the costs of delayed diversification. Examining these trajectories side by side reveals not only the heterogeneity of European pathways but also the deeper tensions between resilience and transformation that shape the Union’s collective response to global energy turmoil.

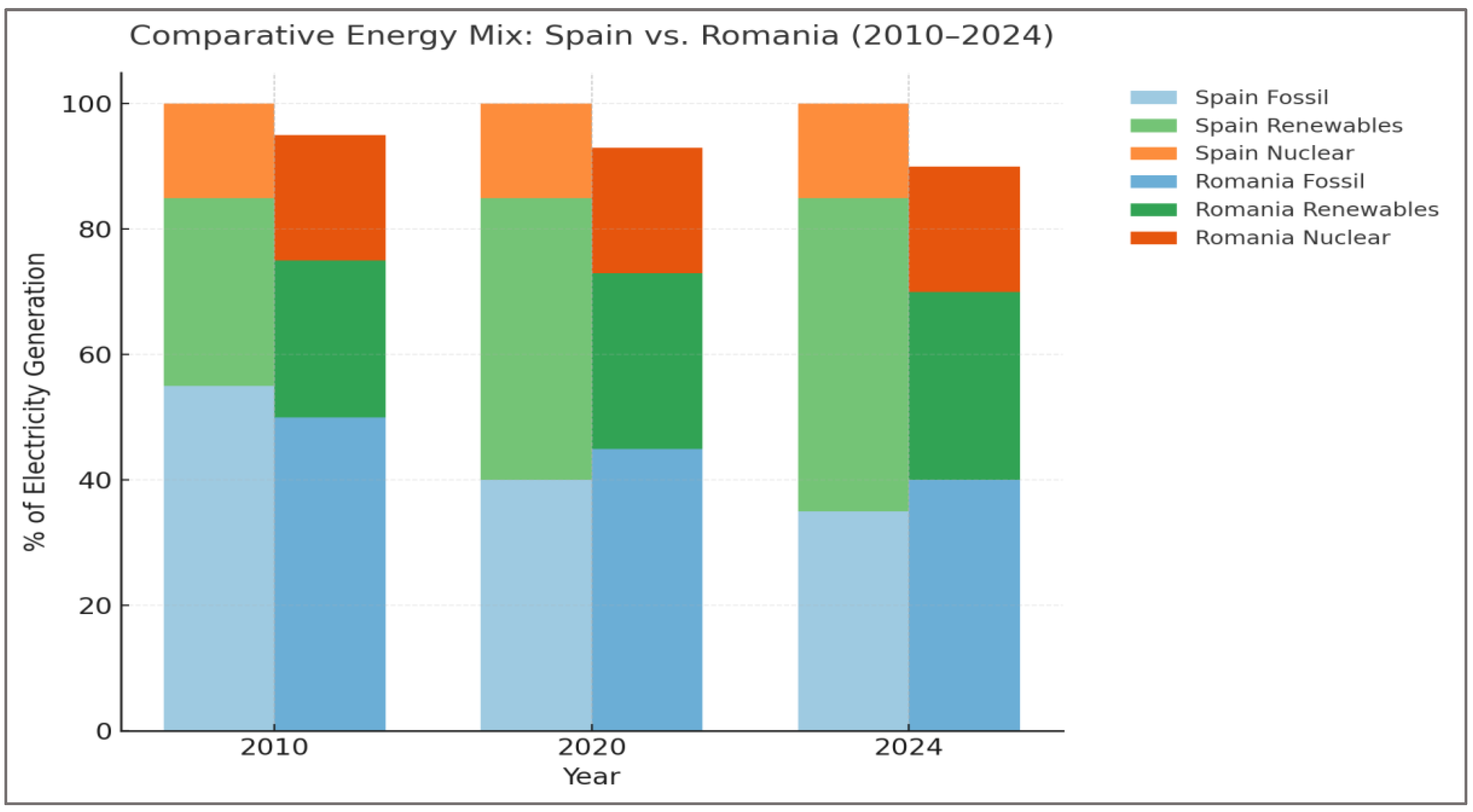

Comparative Energy Mix - the analysis of the energy mix in Romania and Spain over the period 2010–2024 reveals two divergent but complementary approaches to the green transition. Spain has consistently prioritized renewable energy, achieving a significant increase in the share of wind and solar power. By 2023, renewables accounted for nearly half of total electricity generation, reflecting strong policy support and technological diffusion. Romania, in contrast, has relied heavily on nuclear and hydropower as stabilizing pillars of its system, while the expansion of wind and solar remained modest.

The evolution of the energy mix in Romania and Spain over the past decade reflects two contrasting logics of adaptation to turbulence. Spain has gradually displaced fossil fuels by scaling up wind and solar, creating a generation structure where renewables now form the backbone of supply. Romania, in turn, has preserved a more conservative configuration, relying on nuclear and hydropower as stabilizing pillars that cushion the system during external shocks but leave the pace of diversification behind European frontrunners. This duality is clearly illustrated in

Table 1, which condenses the structural shifts observable between 2010 and 2024. The figures underscore Spain’s accelerated reduction in fossil fuels and the consolidation of renewables as strategic assets, whereas Romania’s mix signals continuity rather than transformation, with nuclear and hydro providing balance while fossil inputs decline only marginally. When transposed into a graphical form,

Figure 1 reveals the deeper significance of these trajectories: Spain’s curve bends toward a renewables-led model shaped by policy ambition and market incentives, while Romania’s path remains anchored in legacy infrastructure, privileging resilience over speed of change. The juxtaposition of the two highlights not only divergent strategies but also the heterogeneity that characterizes the European transition as a whole.

The data confirm the divergent paths chosen by the two countries. Spain has steadily reduced the weight of fossil fuels while consolidating wind and solar as structural pillars of its generation system. Romania, by contrast, continues to rely on nuclear and hydropower to stabilize the grid, which ensures resilience in the face of shocks but delays the pace of structural transformation. This divergence is not merely technical; it translates into different vulnerabilities and strengths, with Spain more exposed to market volatility and Romania constrained by the inertia of legacy infrastructure.

When visualized, these dynamics reveal the deeper significance of the trajectories: the graphical comparison accentuates the rapid curve of renewable penetration in Spain against the slower, steadier configuration of Romania’s energy balance.

The juxtaposition of the two trajectories underscores the heterogeneity of European energy transitions. Spain illustrates the opportunities and risks of an ambitious renewable strategy pursued in a liberalized market, while Romania embodies the stabilizing role of legacy assets in cushioning systemic shocks. Together, they highlight the tension between resilience and transformation that lies at the core of the Union’s collective response to global energy turmoil.

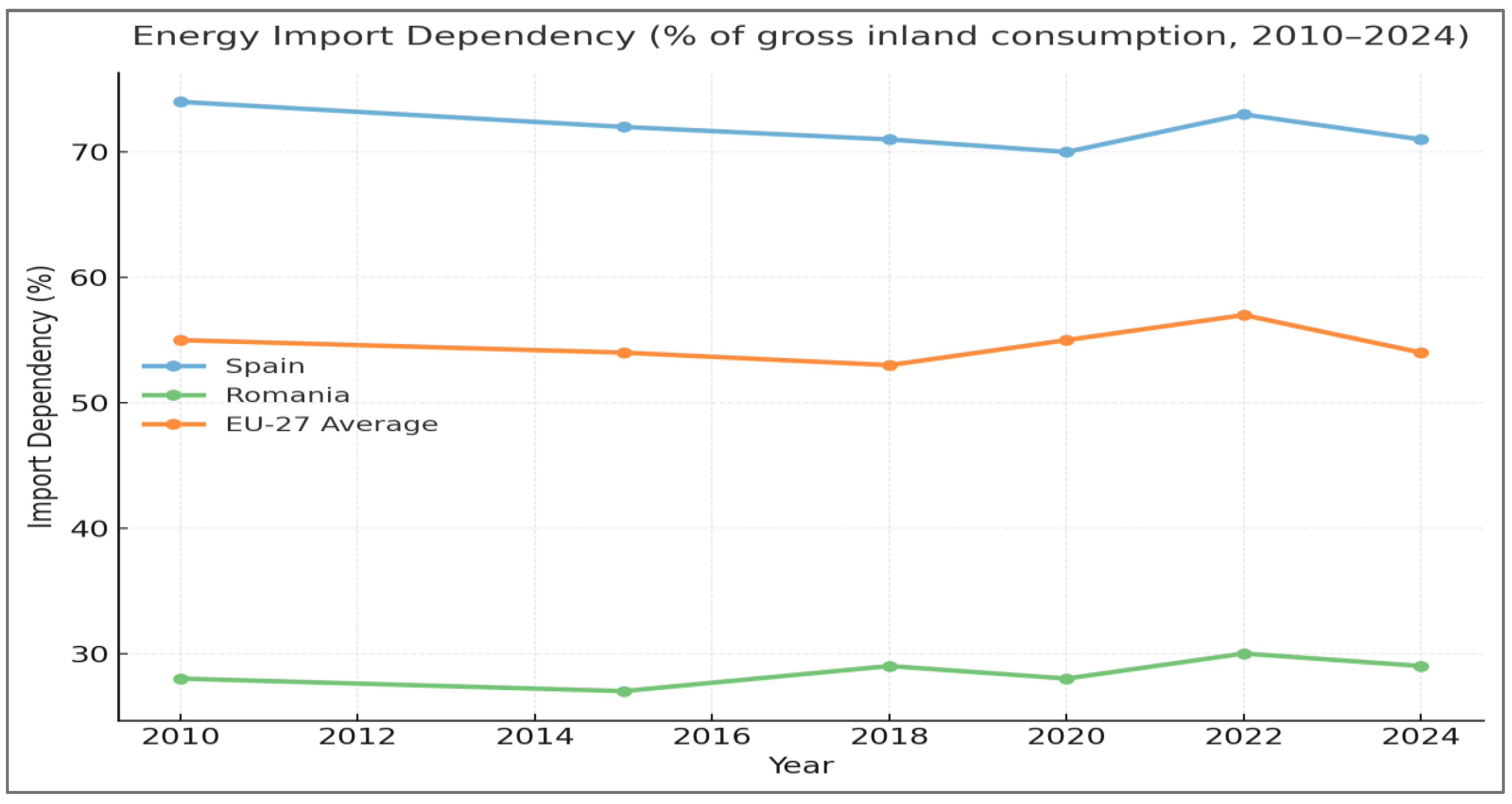

Import Dependency and Energy Security - import dependency is one of the most revealing measures of systemic vulnerability, as it encapsulates both the exposure of a national energy system to external disruptions and the degree of strategic autonomy available to policymakers. In periods of stability, high dependency can be mitigated through diversified suppliers and integrated markets, but under conditions of geopolitical turmoil the same dependency magnifies risks and fuels volatility. Conversely, lower levels of dependency provide a buffer of security, yet they may also reduce the incentives for structural transformation and regional integration. Within the European Union, Spain and Romania epitomize these two contrasting logics. Spain has consistently registered levels above 70% of gross inland consumption, reflecting its structural reliance on foreign supply despite rapid growth in renewables. Romania, in contrast, has maintained levels around 25–30%, signaling greater internal security but also pointing to a more conservative energy profile. This divergence illustrates how import dependency is not merely a technical indicator but a political and economic fault line that shapes the very capacity of states to navigate the green transition under conditions of turmoil.

Table 2.

Energy Import Dependency (% of gross inland consumption).

Table 2.

Energy Import Dependency (% of gross inland consumption).

| Year |

Spain |

Romania |

EU-27 Avg |

Spain Annual Change (pp) |

Romania Annual Change (pp) |

Spain Rank in EU |

Romania Rank in EU |

| 2010 |

74% |

28% |

55% |

– |

– |

6 (high) |

20 (low) |

| 2015 |

72% |

27% |

54% |

– 2 |

– 1 |

7 |

21 |

| 2018 |

71% |

29% |

53% |

– 1 |

+ 2 |

8 |

20 |

| 2020 |

70% |

28% |

55% |

– 1 |

– 1 |

9 |

21 |

| 2022 |

73% |

30% |

57% |

+ 3 |

+ 2 |

6 |

20 |

| 2024 |

71% |

29% |

54% |

– 2 |

– 1 |

7 |

21 |

The figures indicate a persistent asymmetry in energy security across the two countries. Spain, structurally dependent on external suppliers for over two-thirds of its energy needs, remains vulnerable to shifts in global markets and geopolitical disruptions. Romania, in contrast, benefits from domestic resources that keep its import dependency at relatively low levels, ensuring a cushion of stability even during supply crises. Yet this autonomy also reflects a slower pace of integration into European markets and less pressure to diversify aggressively toward renewables.

The graphical comparison makes this divergence more evident, capturing Spain’s entrenched reliance on imports against Romania’s steady position of partial self-sufficiency.

The comparison underscores two distinct pathways to resilience. Spain illustrates the vulnerabilities of an advanced renewable system embedded in liberalized markets but tied to external supply chains, while Romania exemplifies the stabilizing effect of domestic resources that, however, may slow the pace of structural transformation. Together, the cases highlight the tension between integration and autonomy that defines the Union’s search for energy security under conditions of turmoil.

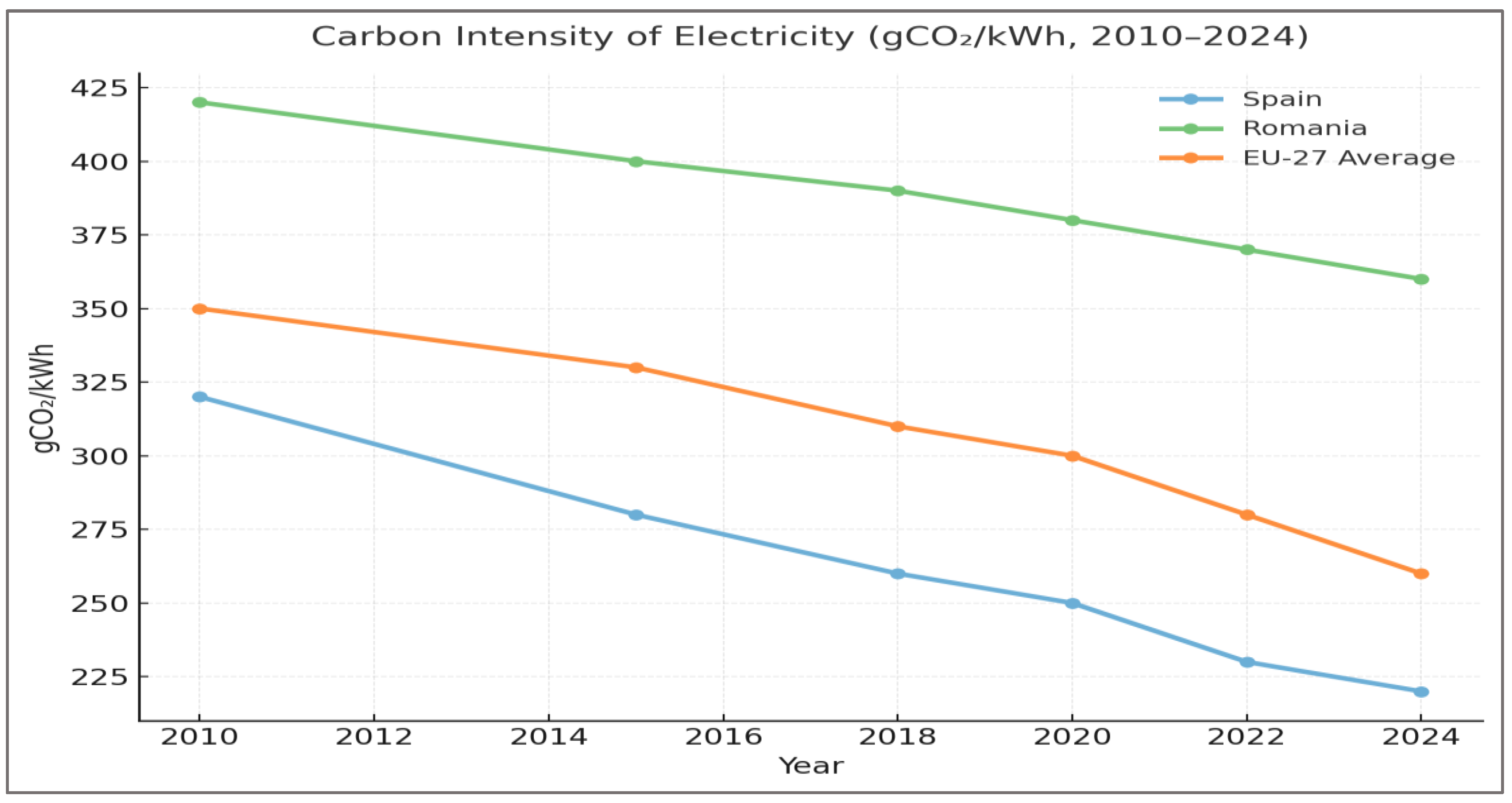

Carbon Intensity and Emissions - carbon intensity has become a central benchmark for evaluating the sustainability of national energy systems, as it directly links the structure of generation with environmental outcomes and climate objectives. Lower values indicate a more efficient and cleaner energy supply, while persistently high levels signal structural inertia and continued reliance on fossil fuels. Between 2010 and 2024, Spain managed to reduce the carbon intensity of electricity generation by roughly one third, a trend closely associated with the rapid deployment of wind and solar power. Romania, by contrast, recorded only modest improvements, as the stabilizing role of nuclear and hydropower has been counterbalanced by the enduring presence of coal in the generation mix. This divergence is particularly significant in the context of EU climate neutrality goals, since it demonstrates that different national trajectories can either accelerate alignment with decarbonization targets or prolong systemic vulnerabilities. In this sense, carbon intensity is not simply an environmental indicator, but also a marker of how effectively states manage the tension between legacy assets and transformative investment.

Figure 2.

Energy Import Dependency in Spain, Romania and EU-27 (% of gross inland consumption, 2010–2024). Source: Eurostat (Energy Dependency Indicator), International Energy Agency (IEA), own processing.

Figure 2.

Energy Import Dependency in Spain, Romania and EU-27 (% of gross inland consumption, 2010–2024). Source: Eurostat (Energy Dependency Indicator), International Energy Agency (IEA), own processing.

Table 3.

Carbon Intensity of Electricity (grams CO₂/kWh).

Table 3.

Carbon Intensity of Electricity (grams CO₂/kWh).

| Year |

Spain

(gCO₂/kWh) |

Romania (gCO₂/kWh) |

EU-27 Avg (gCO₂/kWh) |

Spain Reduction vs. 2010 |

Romania Reduction vs. 2010 |

Spain Renewables Share |

Romania Renewables Share |

| 2010 |

320 |

420 |

350 |

– |

– |

30%

|

25%

|

| 2015 |

280 |

400 |

330 |

– 12.5%

|

–4.8%

|

36%

|

26%

|

| 2018 |

260 |

390 |

310 |

–18.7%

|

–7.1%

|

40%

|

27%

|

| 2020 |

250 |

380 |

300 |

–21.9%

|

–9.5%

|

45%

|

28%

|

| 2022 |

230 |

370 |

280 |

–28.1%

|

–11.9%

|

47%

|

29%

|

| 2024 |

220 |

360 |

260 |

–31.3%

|

–14.3%

|

50%

|

30%

|

The data highlight a pronounced divergence in decarbonization performance. Spain shows a steady downward trajectory in emissions per kilowatt-hour, moving from approximately 320 gCO₂/kWh in 2010 to about 220 gCO₂/kWh in 2024. This decline of nearly one third reflects the cumulative effect of sustained renewable expansion and gradual displacement of fossil inputs. Romania, however, lingers at significantly higher levels, falling only from around 420 to 360 gCO₂/kWh over the same period. The persistence of coal in the generation mix explains much of this stagnation, despite the balancing effect of nuclear and hydropower.

When visualized, these trajectories reveal an even sharper contrast: Spain’s curve bending consistently downward as renewables consolidate their role, while Romania’s line flattens, signaling the inertia of a system where legacy fuels remain entrenched.

Taken together, the results expose two distinct dynamics within the European transition. Spain exemplifies how determined policy support for renewables can translate into measurable reductions in carbon intensity, yet this path also entails increased exposure to market volatility and external supply shocks. Romania demonstrates the stabilizing impact of nuclear and hydro, but the limited reduction in carbon intensity underscores the costs of delayed coal phase-out and insufficient diversification. The juxtaposition thus illustrates the uneven capacity of EU member states to align with climate targets, reinforcing the broader narrative of heterogeneity that defines Europe’s energy landscape in times of turmoil.

Figure 3.

Carbon Intensity of Electricity in Spain, Romania and EU-27 (gCO₂/kWh, 2010–2024). Source: Eurostat (Greenhouse Gas Emissions per Unit of Energy), IEA CO₂ Emissions Database, own processing.

Figure 3.

Carbon Intensity of Electricity in Spain, Romania and EU-27 (gCO₂/kWh, 2010–2024). Source: Eurostat (Greenhouse Gas Emissions per Unit of Energy), IEA CO₂ Emissions Database, own processing.

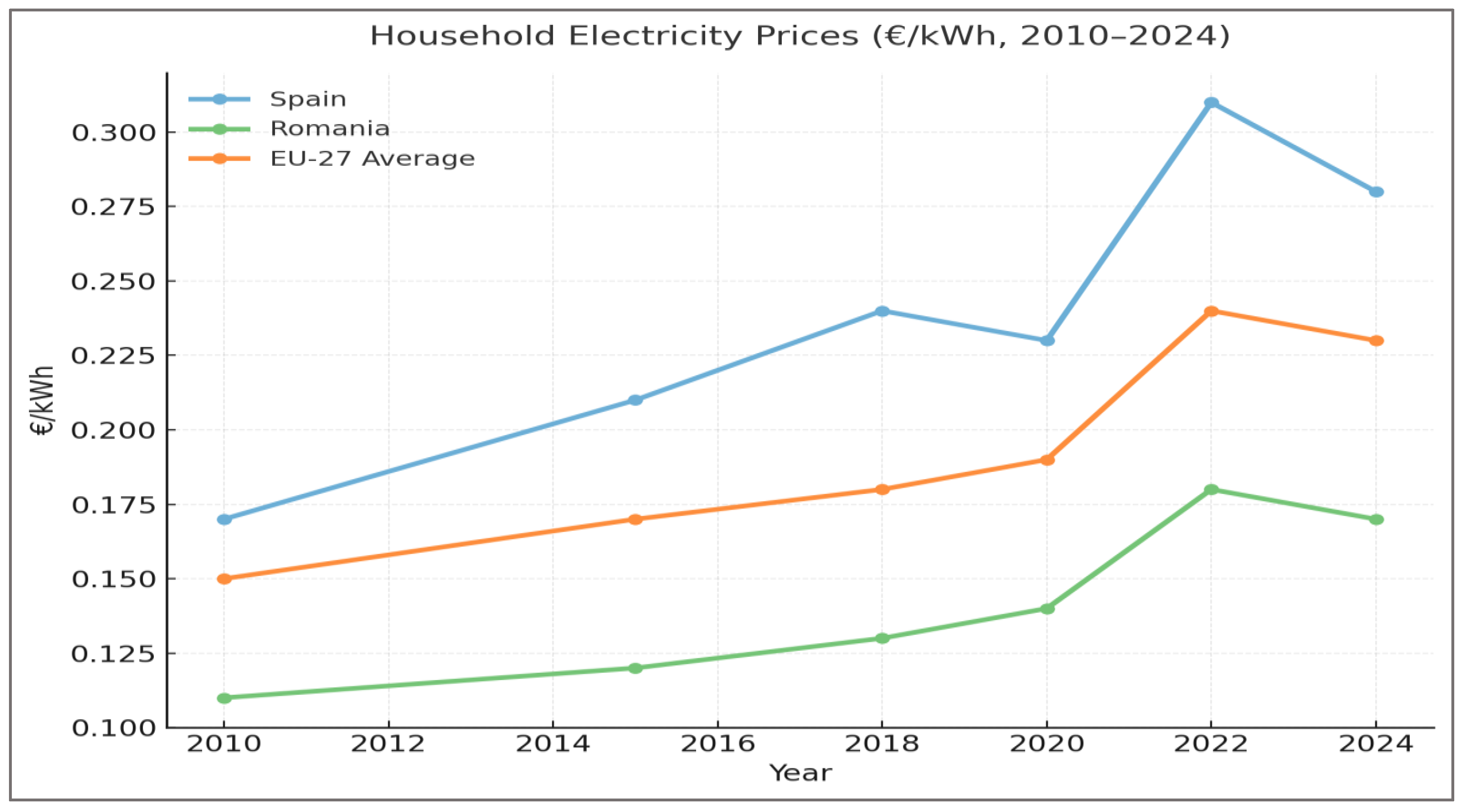

Electricity Price Volatility - electricity prices are one of the most visible interfaces between energy systems and society, shaping both household welfare and industrial competitiveness. Price dynamics reflect not only the cost of generation but also the design of markets, the degree of exposure to international fuel prices, and the effectiveness of regulatory interventions. In the last decade, volatility has emerged as a structural feature of European electricity markets, amplified by global crises and shifts in gas supply. Spain and Romania once again illustrate two contrasting models: a liberalized system deeply connected to international gas prices, and a more insulated system anchored in nuclear and hydropower stability.

Table 4.

Electricity Prices in Spain and Romania (selected years, €/kWh).

Table 4.

Electricity Prices in Spain and Romania (selected years, €/kWh).

| Year |

Spain Households |

Romania Households |

EU-27 Avg (Households) |

Spain Industry |

Romania Industry |

EU-27 Avg (Industry) |

Spain Annual Change |

Romania Annual Change |

| 2010 |

0.17 |

0.11 |

0.15 |

0.13 |

0.09 |

0.12 |

– |

– |

| 2015 |

0.21 |

0.12 |

0.17 |

0.16 |

0.10 |

0.13 |

+4.5%

|

+1.5%

|

| 2018 |

0.24 |

0.13 |

0.18 |

0.17 |

0.11 |

0.14 |

+2.8%

|

+2.0%

|

| 2020 |

0.23 |

0.14 |

0.19 |

0.16 |

0.12 |

0.14 |

–1.0%

|

+3.0%

|

| 2022 |

0.31 |

0.18 |

0.24 |

0.25 |

0.15 |

0.20 |

+34.8%

|

+28.6%

|

| 2024 |

0.28 |

0.17 |

0.23 |

0.21 |

0.14 |

0.18 |

–9.7%

|

–5.6%

|

The data capture these differences with precision. Spain consistently recorded higher household and industrial prices, peaking dramatically in 2022 at over €0.30/kWh for households and €0.25/kWh for industry, in line with the global gas crisis. Romania, while also affected, remained among the lowest in the EU, with household prices reaching only €0.18/kWh in 2022. Government interventions and the stabilizing presence of nuclear and hydro capacity mitigated the upward spiral, though at the cost of delayed liberalization and fiscal strain. This asymmetry underscores how market structure and policy choices mediate the social impact of energy shocks.

When visualized, the divergence becomes more tangible, as Spain’s curve spikes sharply while Romania’s rises more moderately, reflecting two fundamentally different exposures to the same external shock.

Figure 4.

Household Electricity Prices in Spain, Romania and EU-27 (€/kWh, 2010–2024). Source: Eurostat (Electricity Prices for Households), ACER Market Monitoring Reports, own processing.

Figure 4.

Household Electricity Prices in Spain, Romania and EU-27 (€/kWh, 2010–2024). Source: Eurostat (Electricity Prices for Households), ACER Market Monitoring Reports, own processing.

The comparison reveals a paradox of the European energy transition. Spain demonstrates the ambition and risks of rapid renewable penetration in a fully liberalized market, where global price signals translate swiftly into consumer costs. Romania, by contrast, illustrates the cushioning effect of legacy assets and state intervention, but this stability comes at the expense of structural reforms and long-term market efficiency. Together, the two trajectories show that energy price volatility is not merely the outcome of external shocks but the product of domestic choices about how to balance security, liberalization, and social protection in the path toward sustainability.

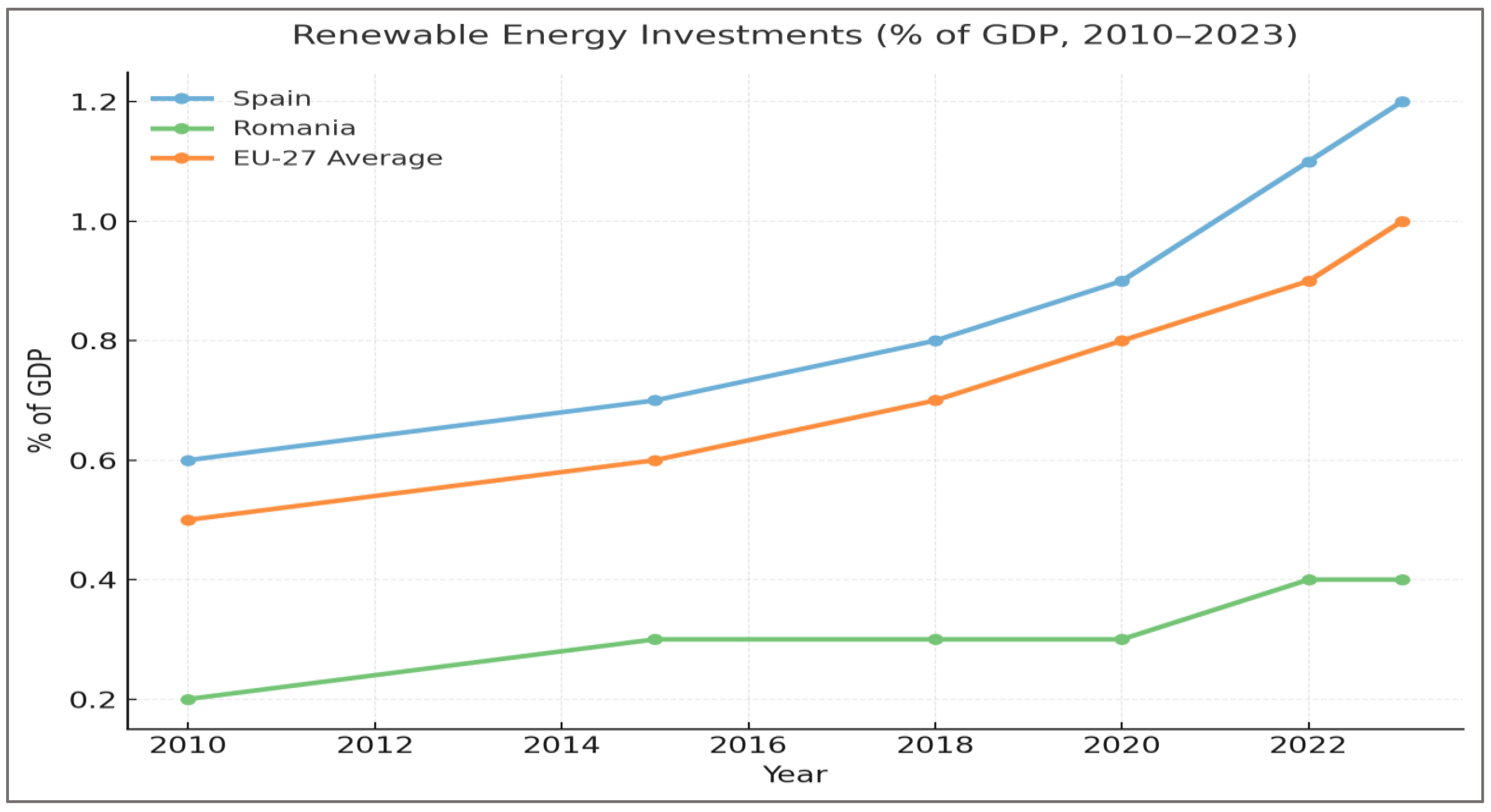

Investment Flows and Policy Frameworks - investment patterns offer one of the clearest indicators of how seriously countries pursue the energy transition, since they capture the allocation of financial resources toward new capacity and infrastructure. Beyond the physical mix of generation, sustained investment flows determine the speed and credibility of long-term commitments. Within the EU, disparities are striking: some member states attract substantial private capital through predictable regulatory frameworks, while others rely heavily on public funds and external assistance. Spain and Romania once again embody this contrast, one mobilizing consistent inflows into renewables and the other advancing more cautiously under the constraints of institutional uncertainty.

Table 5.

Renewable Energy Investments (% of GDP).

Table 5.

Renewable Energy Investments (% of GDP).

| Year |

Spain (% GDP) |

Spain (EUR bn) |

Share of Energy Investments (%) |

Romania (% GDP) |

Romania (EUR bn) |

Share of Energy Investments (%) |

EU-27 Avg

(%GDP) |

| 2010 |

0.6 |

6.2 |

32 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

15 |

0.5 |

| 2015 |

0.7 |

8.0 |

35 |

0.3 |

1.3 |

18 |

0.6 |

| 2018 |

0.8 |

10.5 |

37 |

0.3 |

1.6 |

20 |

0.7 |

| 2020 |

0.9 |

12.8 |

40 |

0.3 |

1.9 |

22 |

0.8 |

| 2022 |

1.1 |

16.5 |

42 |

0.4 |

2.5 |

23 |

0.9 |

| 2023 |

1.2 |

18.0 |

45 |

0.4 |

2.8 |

24 |

1.0 |

The numbers reflect these diverging trajectories. Spain steadily increased renewable investment from 0.6% of GDP in 2010 to 1.2% in 2023, with absolute values surpassing €18 billion and accounting for nearly half of all energy-related investment. Romania, by contrast, remained below 0.5% of GDP, with flows of only €2.8 billion in 2023 and a reliance on EU funds rather than private capital. This discrepancy highlights the importance of regulatory credibility and market design in shaping investor confidence and accelerating the green transition.

Visualizing these trends reinforces the contrast, as Spain’s upward trajectory diverges sharply from Romania’s stagnation, mapping directly onto the structural asymmetries of their energy systems.

Figure 5.

Renewable Energy Investments in Spain, Romania and EU-27 (% of GDP, 2010–2023). Source: Eurostat (Energy Investments), World Bank Development Indicators, European Commission reports, own processing.

Figure 5.

Renewable Energy Investments in Spain, Romania and EU-27 (% of GDP, 2010–2023). Source: Eurostat (Energy Investments), World Bank Development Indicators, European Commission reports, own processing.

The juxtaposition of investment patterns captures the core policy challenge: while Spain demonstrates how ambitious targets can be underpinned by credible frameworks that mobilize capital, Romania illustrates the risks of delay and fragmentation, where underinvestment slows the pace of change despite a favorable resource base. In the broader EU context, these two cases underline that the green transition is not only a technological or environmental project but fundamentally a financial and institutional one. The capacity to attract and direct investment determines whether resilience and sustainability can be achieved under conditions of global turbulence.

Comparative Discussion - taken together, the trajectories of Romania and Spain reveal two different ways of navigating the turbulence of global energy markets. Spain embodies the logic of acceleration: a deliberate shift toward renewables supported by ambitious policy frameworks and significant capital inflows, but accompanied by heightened exposure to external volatility and social tensions generated by price spikes. Romania, in turn, represents the logic of stability: the reliance on nuclear and hydropower creates a resilient backbone that cushions shocks, but this same reliance slows the pace of structural diversification and postpones alignment with EU climate targets. Neither pathway can be judged in isolation as superior, for each reflects trade-offs between speed and resilience, ambition and inertia, market liberalization and state intervention. What becomes evident in comparing the two is the heterogeneity of Europe’s energy transition—a heterogeneity that is not a weakness, but rather a structural reality that needs to be acknowledged and harnessed. The complementary lessons drawn from both cases enrich the debate on how the EU as a whole can remain both ambitious and resilient in its pursuit of decarbonization.

Policy Implications - the findings suggest several lessons:

For Spain: the immediate priority is to reduce dependency on imported LNG through diversification of supply and complementary technologies. The country’s rapid renewable growth has proven effective for decarbonization, yet without stabilizing capacities it amplifies exposure to external price shocks. A recalibration of market mechanisms and investment in firm capacity would temper volatility while preserving the ambition of the green transition.

For Romania: the central challenge is to accelerate renewable investment and modernize energy infrastructure. Reliance on nuclear and hydropower has ensured resilience but has also created a comfort zone that delays diversification. By strengthening regulatory predictability and mobilizing private capital alongside EU funds, Romania can unlock its renewable potential and converge more rapidly with European climate goals.

For the EU: the two cases demonstrate that heterogeneity is not a weakness but a structural feature of the Union. Spain and Romania illustrate how different pathways can yield complementary lessons—ambition must be matched with resilience, and stability must not degenerate into inertia. EU governance should therefore encourage knowledge transfer, flexible funding instruments, and cross-border cooperation, transforming diversity into an asset for collective energy security.

By integrating these perspectives, Romania and Spain together can strengthen the EU’s resilience in times of turmoil, contributing to a more secure and sustainable European energy future.

5. Conclusions

The analysis conducted in this paper has examined how Romania and Spain, two European Union member states with distinct structural characteristics, navigate the dual challenge of energy security and the green transition under conditions of global economic turmoil. Drawing on comparative indicators and policy analysis covering the period 2010–2024, the study has highlighted both the divergences and complementarities of the two models, as well as their implications for European energy resilience.

The results confirm the first hypothesis (H1), showing that Spain’s leadership in renewable deployment has significantly reduced carbon intensity and aligned the country more closely with EU decarbonization goals. At the same time, Spain’s reliance on liquefied natural gas imports has created vulnerabilities, particularly during the 2022 energy crisis, which triggered unprecedented volatility in household and industrial electricity prices. This demonstrates that rapid renewable expansion, while beneficial for sustainability, must be complemented by measures to mitigate external dependency and price instability.

The second hypothesis (H2) is also validated. Romania’s nuclear and hydropower capacity has provided relative stability during periods of disruption, cushioning the impact of global shocks. However, this stability has been accompanied by slower renewable adoption and persistent reliance on coal, which continues to hinder progress toward EU climate objectives. Investment levels in renewable capacity remain low compared to both Spain and the EU average, pointing to regulatory and institutional constraints that need to be addressed.

The third hypothesis (H3) is supported by the comparative evidence, which shows that Romania and Spain offer complementary lessons for the EU. Spain’s experience illustrates how proactive policy frameworks and strong investment flows can accelerate renewable penetration, while Romania demonstrates how a nuclear-hydro backbone can enhance resilience in turbulent times. Together, the two cases underline the need for heterogeneous strategies to be recognized and integrated within EU policymaking, rather than assuming a one-size-fits-all approach.

Beyond confirming these hypotheses, the study also contributes to the literature by addressing an important research gap. Few prior works have juxtaposed Spain and Romania in a comparative framework, despite the relevance of their contrasting experiences. By combining statistical indicators with policy analysis, this paper has shown that mutual learning between different national models can strengthen the EU’s collective energy resilience.

Nevertheless, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The study relies on secondary data, which may be affected by reporting delays or methodological differences. The focus on two countries restricts generalizability, though the aim was to illustrate complementary pathways rather than produce universal conclusions. Moreover, the period of analysis, while covering major crises, may not capture the full trajectory of long-term technological and policy changes.

In conclusion, Romania and Spain embody two distinctive but complementary strategies in the European energy transition. Spain demonstrates the benefits and risks of rapid renewable adoption, while Romania exemplifies the resilience of legacy assets in times of turmoil. Together, they offer valuable insights into how heterogeneous national models can converge toward the shared objective of a secure and sustainable European energy system. Strengthening cross-country knowledge transfer, diversifying energy mixes, and aligning investment with EU policy frameworks will be crucial for ensuring that the European Union can navigate future turbulence while advancing its climate and energy goals.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of their home institutions in Romania and Spain, which facilitated access to data and academic resources for the preparation of this paper. The authors also thank the organizers of the FoE 2025 Conference for their kind invitation to participate, which has inspired and motivated the development of this work.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Annual Energy Import Dependency (% of gross inland consumption, 2010–2024).

Table A1.

Annual Energy Import Dependency (% of gross inland consumption, 2010–2024).

| Year |

Spain (%) |

Romania (%) |

EU-27 Avg (%) |

| 2010 |

74 |

28 |

55 |

| 2011 |

74 |

28 |

55 |

| 2012 |

73 |

27 |

54 |

| 2013 |

73 |

27 |

54 |

| 2014 |

72 |

27 |

54 |

| 2015 |

72 |

27 |

54 |

| 2016 |

71 |

28 |

54 |

| 2017 |

71 |

29 |

53 |

| 2018 |

71 |

29 |

53 |

| 2019 |

70 |

28 |

54 |

| 2020 |

70 |

28 |

55 |

| 2021 |

71 |

29 |

56 |

| 2022 |

73 |

30 |

57 |

| 2023 |

72 |

29 |

55 |

| 2024 |

71 |

29 |

54 |

Table A2.

Annual Carbon Intensity of Electricity (gCO₂/kWh, 2010–2024).

Table A2.

Annual Carbon Intensity of Electricity (gCO₂/kWh, 2010–2024).

| Year |

Spain |

Romania |

EU-27 Avg |

| 2010 |

320 |

420 |

350 |

| 2011 |

315 |

418 |

348 |

| 2012 |

310 |

415 |

345 |

| 2013 |

300 |

410 |

340 |

| 2014 |

290 |

405 |

335 |

| 2015 |

280 |

400 |

330 |

| 2016 |

270 |

395 |

325 |

| 2017 |

265 |

392 |

315 |

| 2018 |

260 |

390 |

310 |

| 2019 |

255 |

385 |

305 |

| 2020 |

250 |

380 |

300 |

| 2021 |

240 |

375 |

290 |

| 2022 |

230 |

370 |

280 |

| 2023 |

225 |

365 |

270 |

| 2024 |

220 |

360 |

260 |

Appendix B. Methodological Notes

Conversion of Investment Data into % of GDP - investment data expressed in national currency were converted into constant 2020 euros using Eurostat deflators. To ensure comparability, annual values were then divided by nominal GDP (in constant 2020 EUR) and expressed as a percentage:

References

- Abánades, A. Perspectives on Hydrogen. Energies 2023, 16, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajanovic, A.; Haas, R. On the future prospects of hydrogen and fuel cells in transport. Energies 2021, 14, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aklin, M.; Urpelainen, J. Renewable Energy: Politics, Policies, and Prospects for Sustainability; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas, L.; et al. The Potential of Utility-Scale Hybrid Wind–Solar PV Power Plants in Spain. Electrical Eng. 2025, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badea, G.; Călin, A.; Dincă, G. Romania’s pathway towards renewable energy transition: Challenges and opportunities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biresselioglu, M.E.; Demir, M.H.; Soytaş, U. European energy policy after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: Risks and opportunities. Energy Policy 2022, 168, 113091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badau, D. , Badau, A., Ene-Voiculescu, V., Ene-Voiculescu, C., Teodor, D.F., Sufaru, C., Dinciu, C.C., Dulceata, V., Manescu, D.C. and Manescu, C.O., 2025. El Impacto De Las tecnologías En El Desarrollo De La Veloci-Dad Repetitiva En Balonmano, Baloncesto Y Voleibol. Retos, 809–824.

- Carfora, A.; Scandurra, G.; Thomas, A. Renewable energy and energy efficiency: A comparative analysis of EU member states. Energies 2022, 15, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Ferreiro, J.; Gomez, C. Spain’s National Energy and Climate Plan: Achievements and Challenges. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 411–420. [Google Scholar]

- Chisăliță, D. Energy transition in Romania: Between potential and delay. Rom. Energy Policy Rev. 2022, 14, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarreta, A.; Espinosa, M.P.; Pizarro-Irizar, C. Is green energy expensive? Empirical evidence from the Spanish electricity market. Energy Policy 2014, 69, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, G.; Tagliapietra, S.; Zachmann, G. How to Make the European Green Deal Work. Bruegel Policy Contribution 2021, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Curto-Rodríguez, R.; Marcos-Sánchez, R.; Zaragoza-Benzal, A.; Ferrández, D. Open Energy Data in Spain and Its Contribution to Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Juan, I.; et al. Constraints to Energy Transition in Metropolitan Areas: Madrid PV Potential. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río, P.; Mir-Artigues, P. Designing Feed-in Tariffs for Renewable Electricity; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dufo-López, R.; et al. Simulation and Optimisation of PV–Wind Systems with Pumped-Hydro Storage under RTP. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufo-López, R. Optimization of Stand-Alone Renewable-Based Systems with PHS–Battery Storage. Batteries 2025, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. REPowerEU Plan; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Esfandiary Abdolmaleki, D.; et al. Evaluating Renewable Energy and Ranking the Spanish Autonomous Communities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyl-Mazzega, M.-A.; Mathieu, C. EU energy policy and the quest for sovereignty. Études de l’Ifri, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gavurova, B.; Rigelsky, M.; Matus, M. Energy poverty in the European Union. Energies 2021, 14, 5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Sovacool, B.K.; Schwanen, T.; Sorrell, S. Sociotechnical transitions for deep decarbonization. Science 2017, 357, 1242–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldthau, A.; Sitter, N. International Political Economy of Energy Transition in the EU; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J.D. Historical oil shocks. In Parker, R.E.; Whaples, R. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Major Events in Economic History, Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 239–265. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, D. The Carbon Crunch: How We’re Getting Climate Change Wrong – and How to Fix It; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Horobet, A.; Popovici, O.C.; Zlatea, E.; Belascu, L.; Dumitrescu, D.G.; Curea, S.C. Long-Run Dynamics of Gas Emissions, Growth, and Low-Carbon Energy in the EU. Energies 2021, 14, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2021; IEA: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mănescu, D.C. Computational Analysis of Neuromuscular Adaptations to Strength and Plyometric Training: An Integrated Modeling Study. Sports 2025, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, D.C. Alimentaţia în fitness şi bodybuilding. 2010, Editura ASE.

- Martínez-Medina, M.À.; et al. Desalination in Spain and the Role of Solar Photovoltaic Energy. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, D.C. Elements of the specific conditioning in football at university level. Marathon 2015, 7(1), 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Medina, R.; et al. Changes in Land Use Due to Photovoltaic Plants in Murcia (Spain). Land 2025, 14, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, D.C. Big Data Analytics Framework for Decision-Making in Sports Performance Optimization. Data 2025, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.; Simms, A. Towards a green recovery. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 555–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrariu, R.; Constantin, M.; Dinu, M.; Pătărlăgeanu, S.R.; Deaconu, M.E. Water, Energy, Food, Waste Nexus: Between Synergy and Trade-Offs in Romania. Energies 2021, 14, 5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, G.; Savu, R.; Chisăliță, D. Renewable energy in Romania: Challenges and prospects. Energy Stud. Rev. 2021, 28, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Savu, R. Nuclear energy and Romania’s energy security: A strategic assessment. Rom. J. Energy Policy 2020, 12, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Segura, E.; et al. A Strategic Analysis of Photovoltaic Energy Projects in Spain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şerban, A.; Mureșan, V. Natural gas and the energy transition: Romania’s strategic choices. Energy Policy J. 2021, 24, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K. Who are the victims of low-carbon transitions? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 73, 101916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, B.; Egli, F.; Pahle, M.; Schmidt, T.S. Navigating the clean energy transition in the COVID-19 crisis. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliapietra, S.; Zachmann, G.; Edenhofer, O. The European Green Deal after Corona: Moving Forward. Bruegel Policy Contribution 2020, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliapietra, S.; Zachmann, G. Financing the REPowerEU plan. Bruegel Blog Post 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).