Submitted:

21 October 2024

Posted:

22 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Development of Energy Security

1.2. Modern Definitions and Components

1.3. Threats and Challenges

1.4. Primary Energy Production and Energy Security

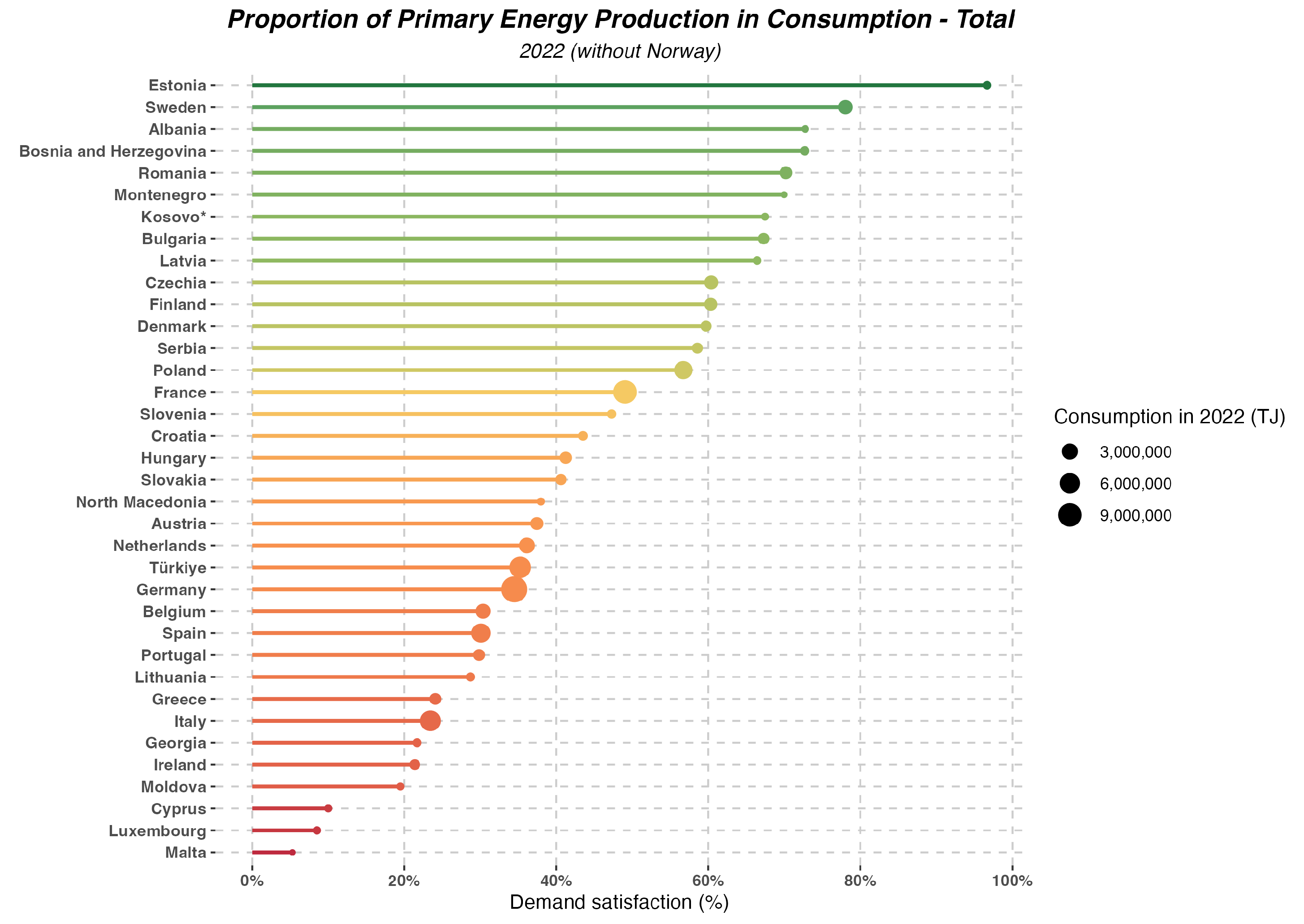

2. Primary Energy Production in the European Union and Other European Countries

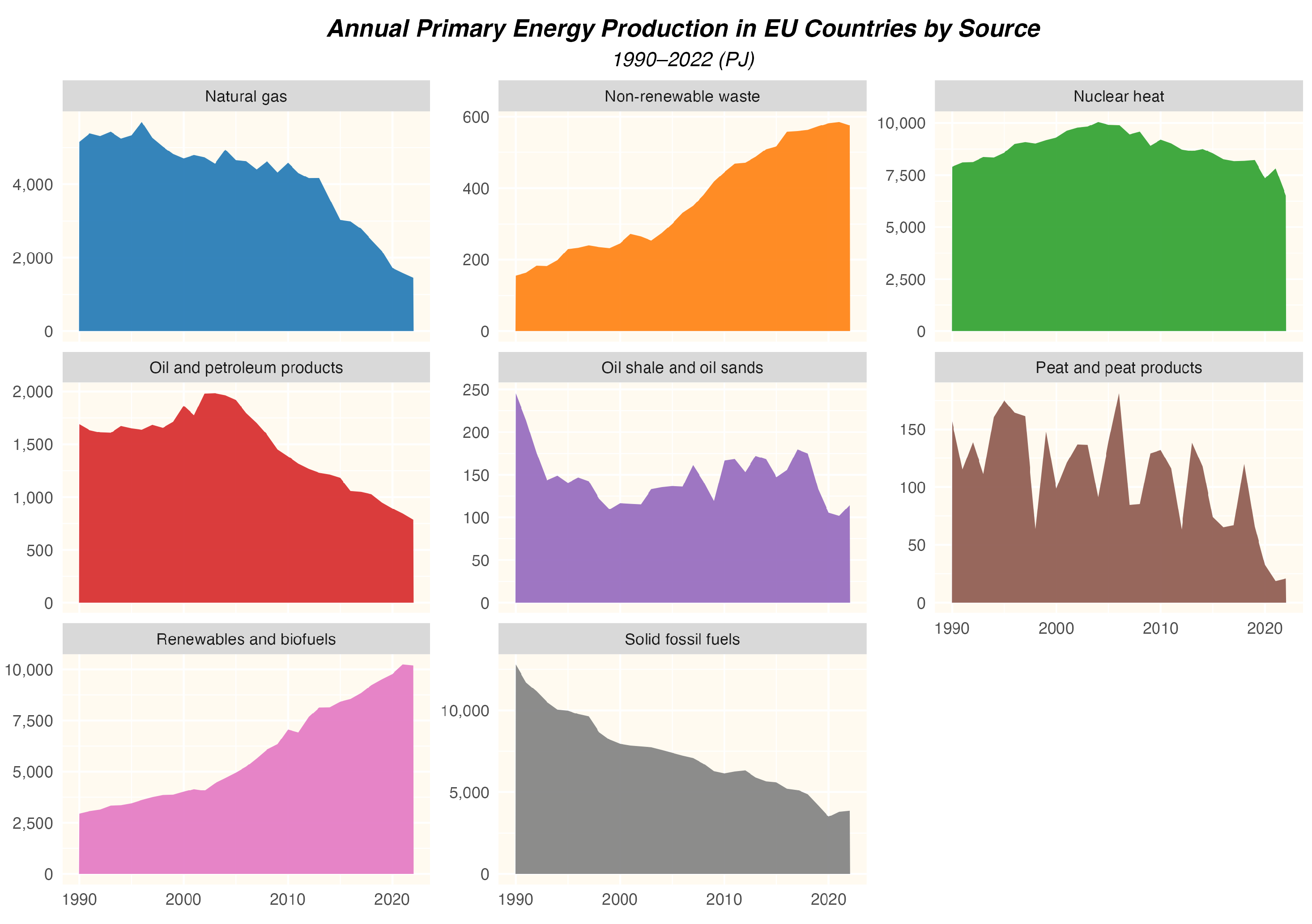

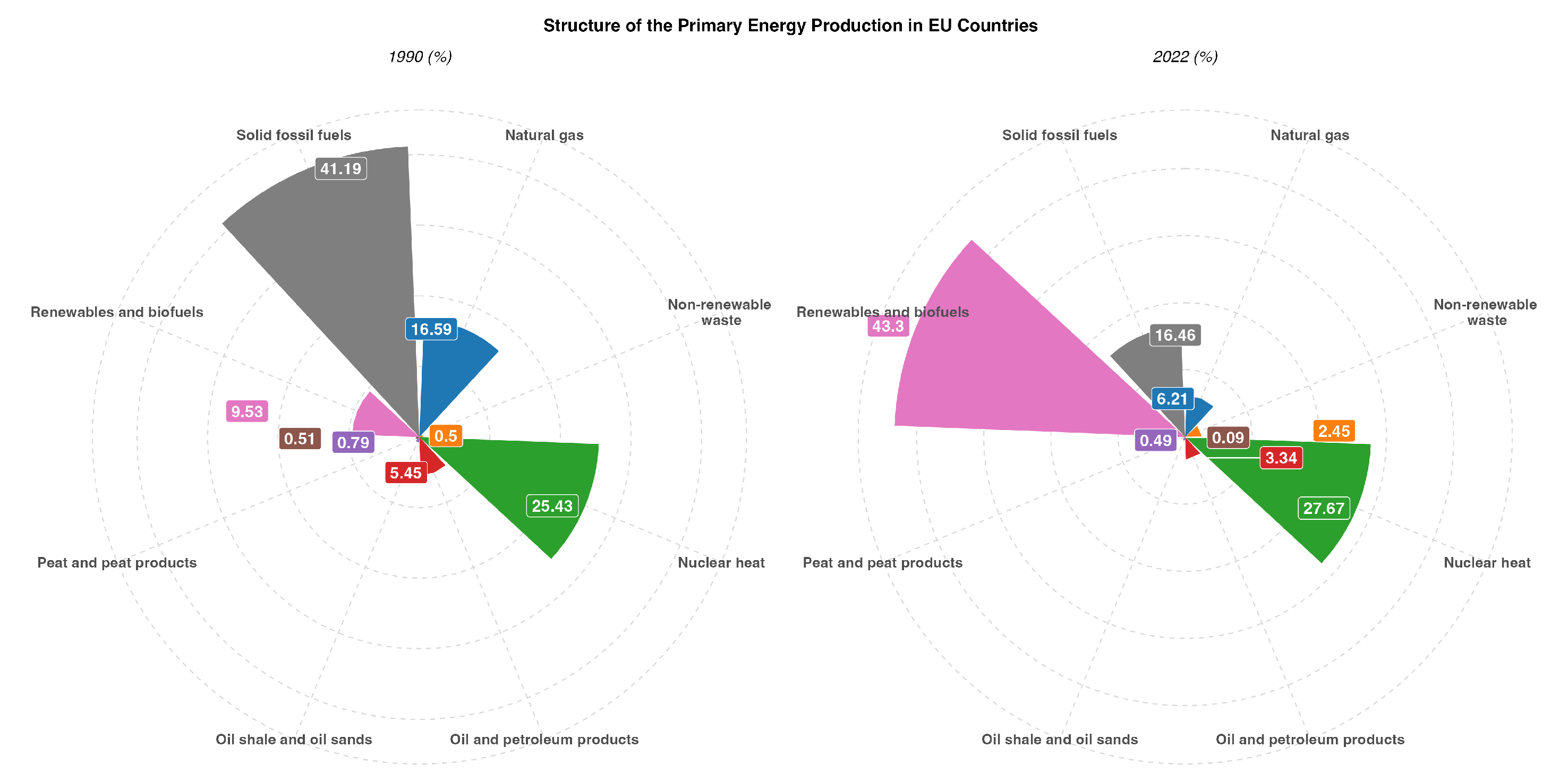

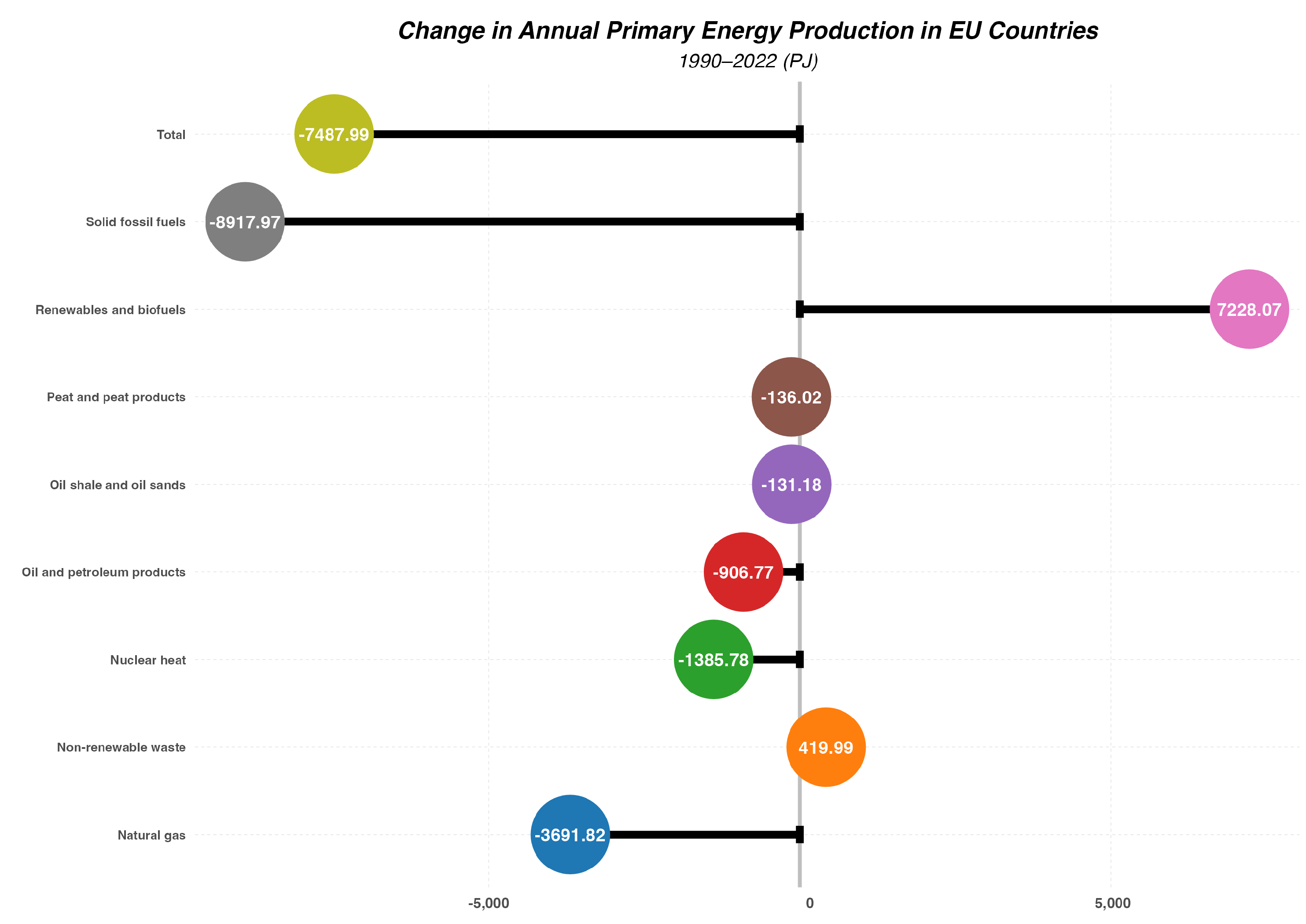

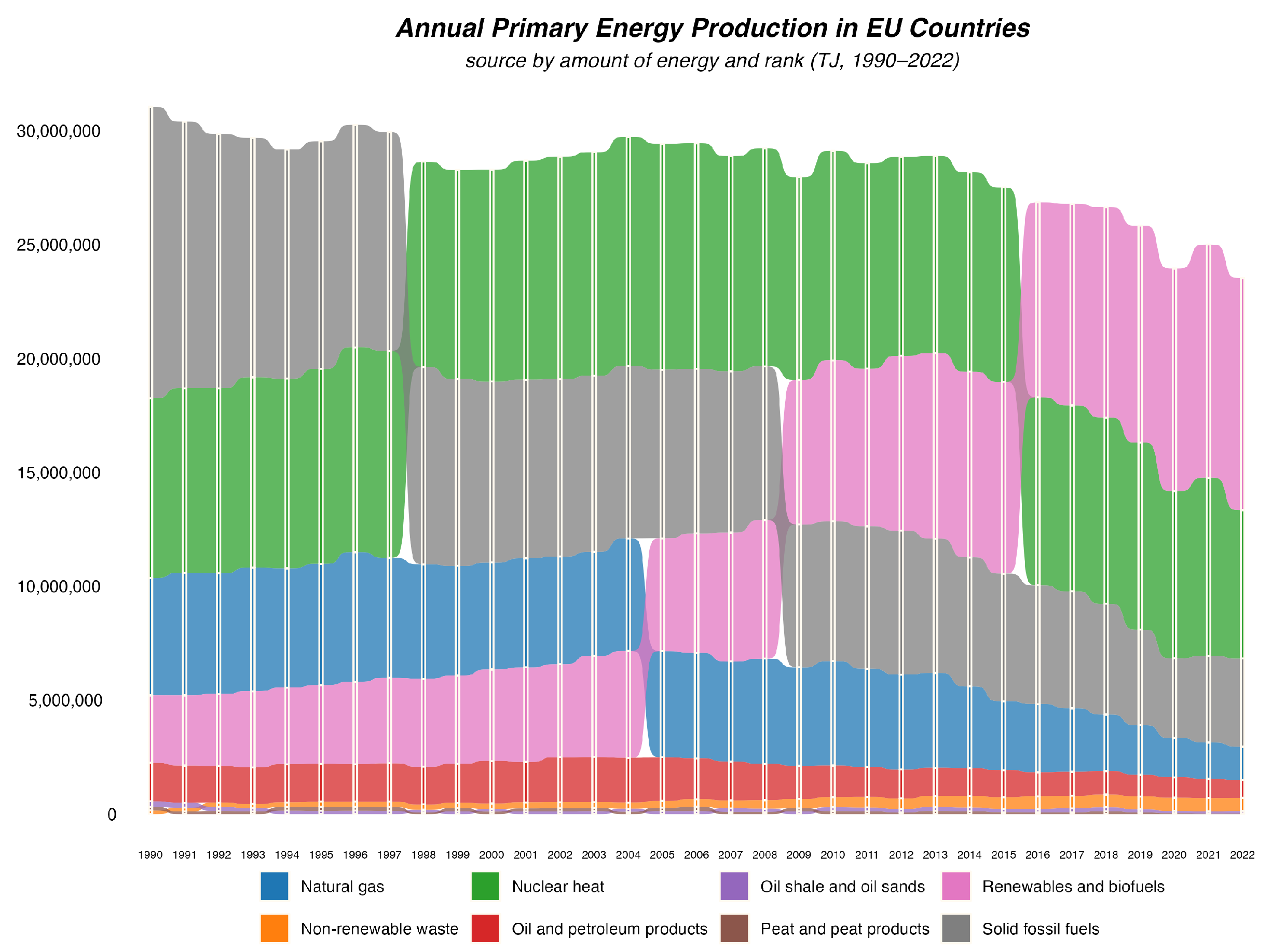

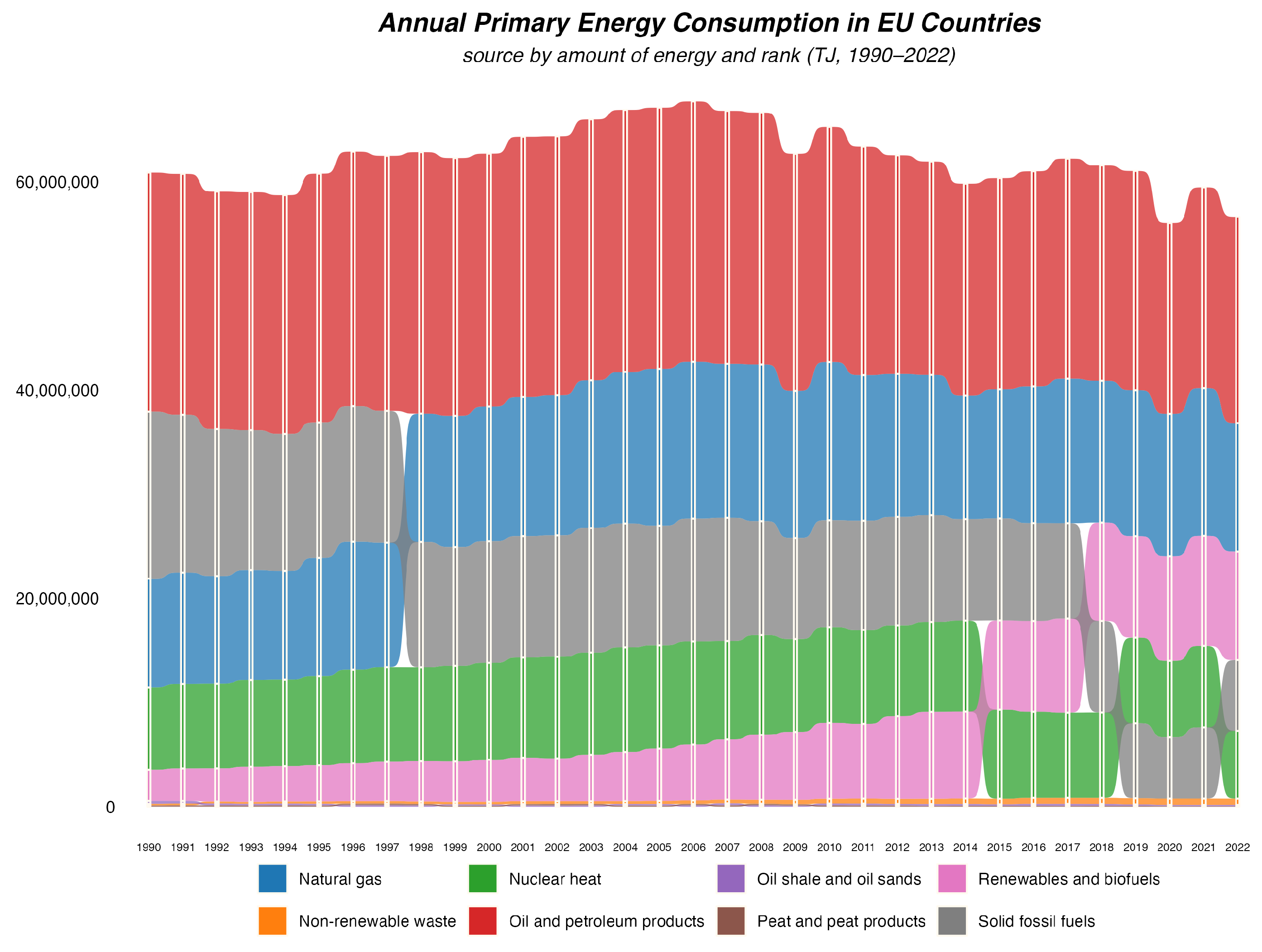

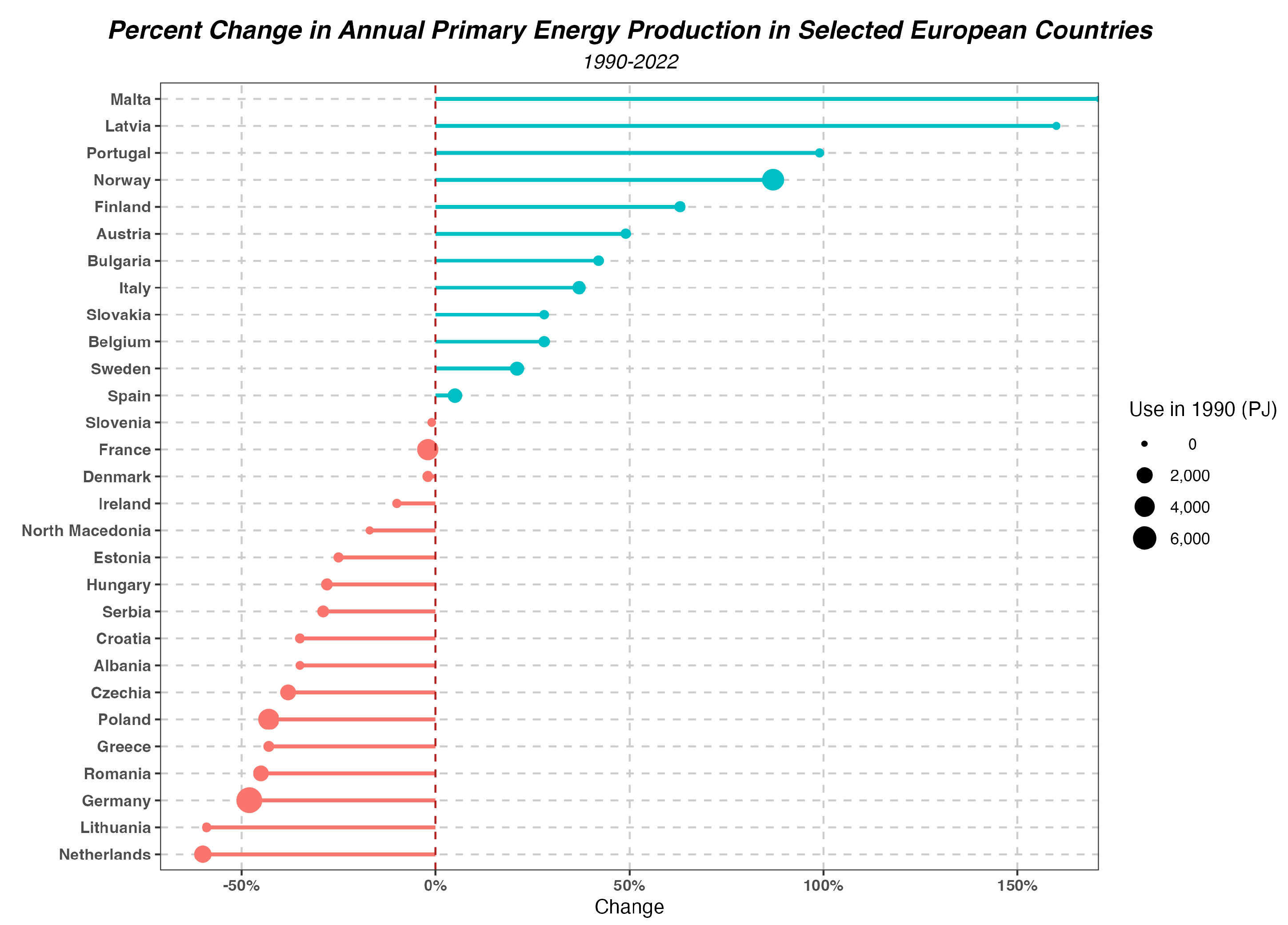

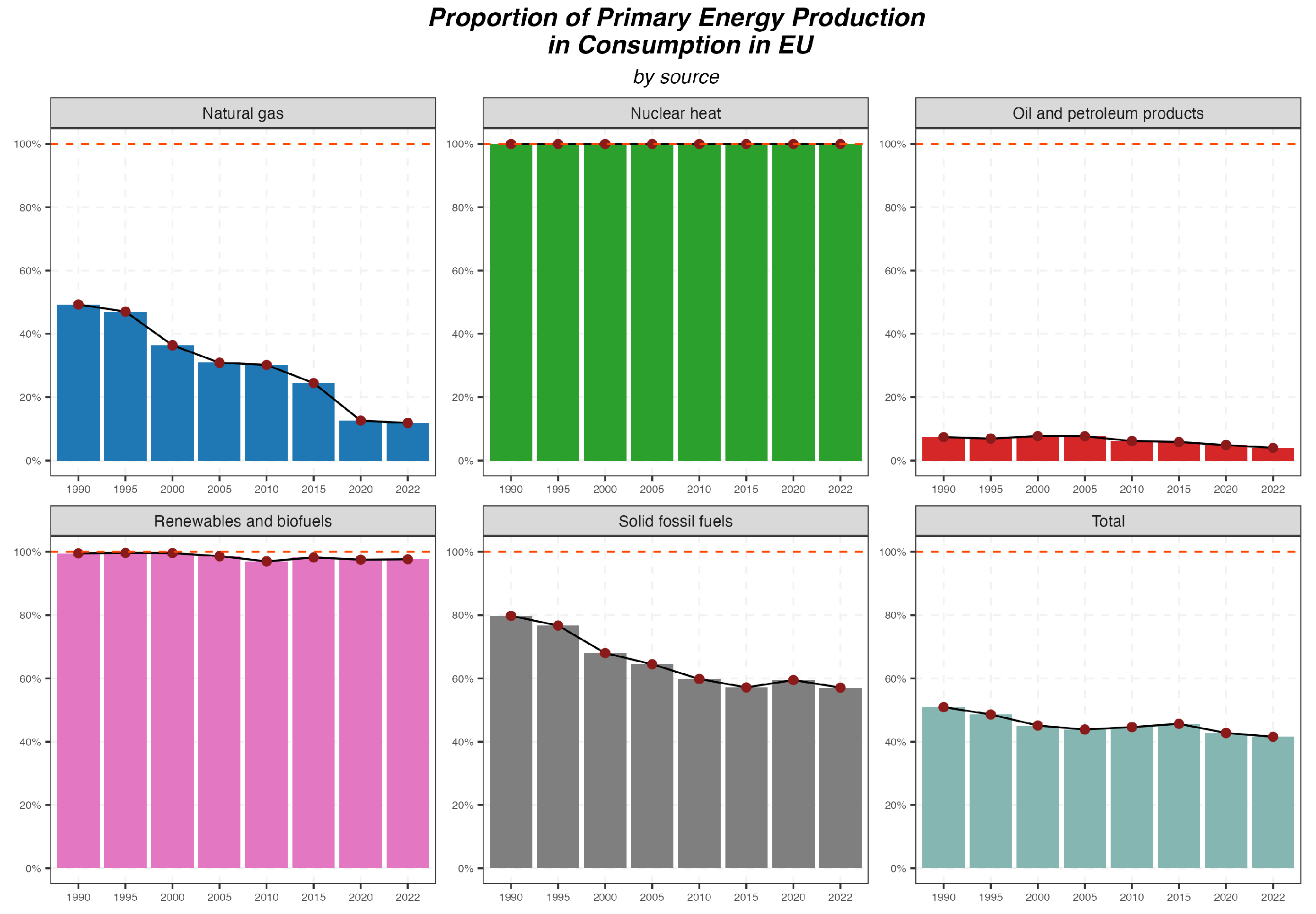

- The production of primary energy in the EU has significantly decreased over the last thirty years, with nearly unchanged consumption.

- There are significant differences between the structure of primary energy production and consumption in the EU. For some sources (such as crude oil), almost the entire consumption is met through imports.

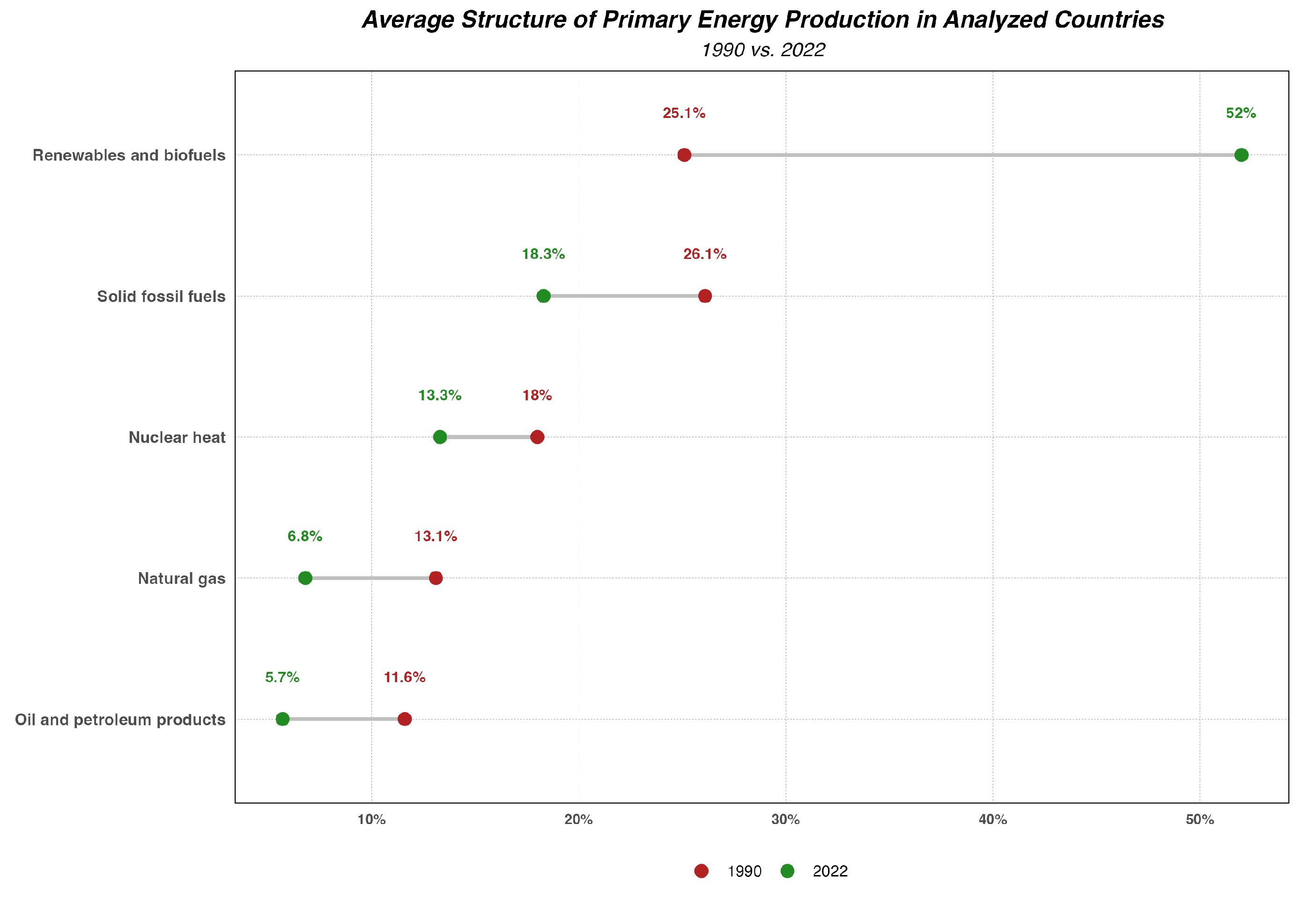

- Renewable energy sources have become the dominant source of primary energy production in EU countries, which is a positive trend in terms of sustainable development but increases risks related to the stability of energy supplies and other aspects of broadly defined energy security.

- EU countries, especially large economies, are heavily dependent on energy imports, which poses a challenge to energy security.

- To reduce dependency on imports, further investments in renewable energy sources, energy transmission and storage systems, and improvements in energy efficiency are necessary.

- High dependence on primary energy imports constitutes a significant risk to the energy security of EU countries. Geopolitical changes, supply disruptions, and rising prices of imported energy can negatively impact the region’s energy stability. Therefore, to ensure energy security, it is essential to pursue an appropriate energy policy that combines the continued development of renewable energy sources with the assurance of stable supplies of those primary energy sources that cannot be easily and quickly replaced by renewable energy.

3. Cluster Analysis

3.1. Theoretical Introduction

3.1.1. K-Means Algorithm

- Initialization: Choose the number of clusters k and randomly initialize k centroids.

- Assignment: Assign each data point to the nearest centroid using a distance metric, typically Euclidean distance, forming k clusters.

- Update: Recompute the centroids by calculating the mean of all data points in each cluster.

- Iteration: Repeat the assignment and update steps until convergence is achieved—when centroids stabilize or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

- Result: Finalize the clustering with each data point assigned to its nearest centroid, partitioning the dataset into k clusters.

- Simplicity: Easy to understand and implement due to its straightforward approach.

- Scalability: Efficiently handles large datasets with linear time complexity, suitable for big data applications.

- Speed: Generally converges quickly because of its simple iterative process.

- Interpretability: Clusters are often interpretable, especially in datasets with low dimensions.

- Versatility: Applicable to various data types, including numerical, categorical, and binary data.

- Sensitivity to Initial Centroids: Different initial centroid placements can lead to varying results.

- Outlier Influence: Susceptible to outliers, which can distort cluster centroids and sizes.

- Assumption of Cluster Shape: Assumes clusters are convex and similar in size, which may not be true for all datasets.

- Determining Optimal k: Selecting the appropriate number of clusters k is subjective and affects clustering quality.

- Feature Scaling Impact: Features with larger scales can dominate distance calculations, potentially biasing the algorithm.

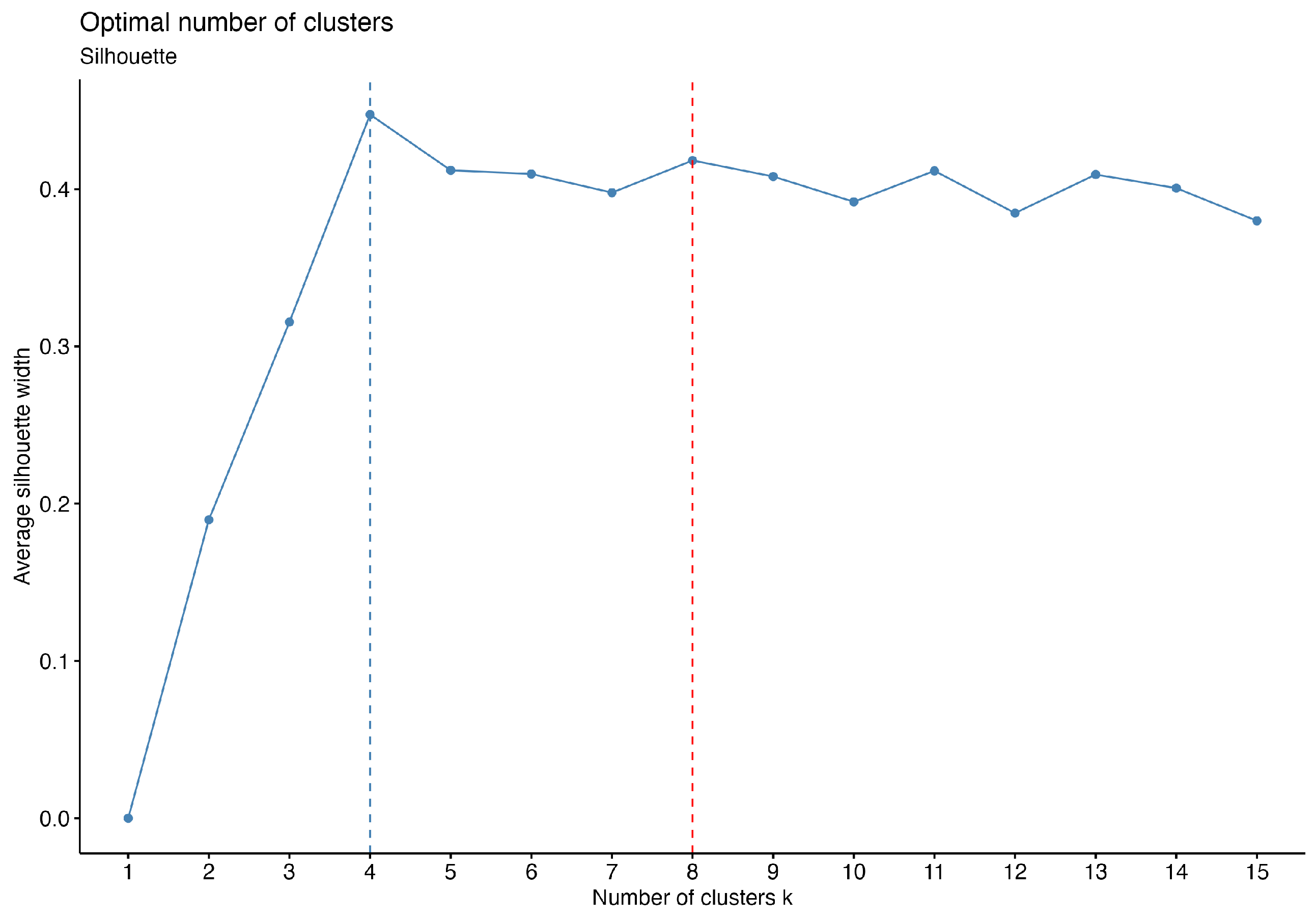

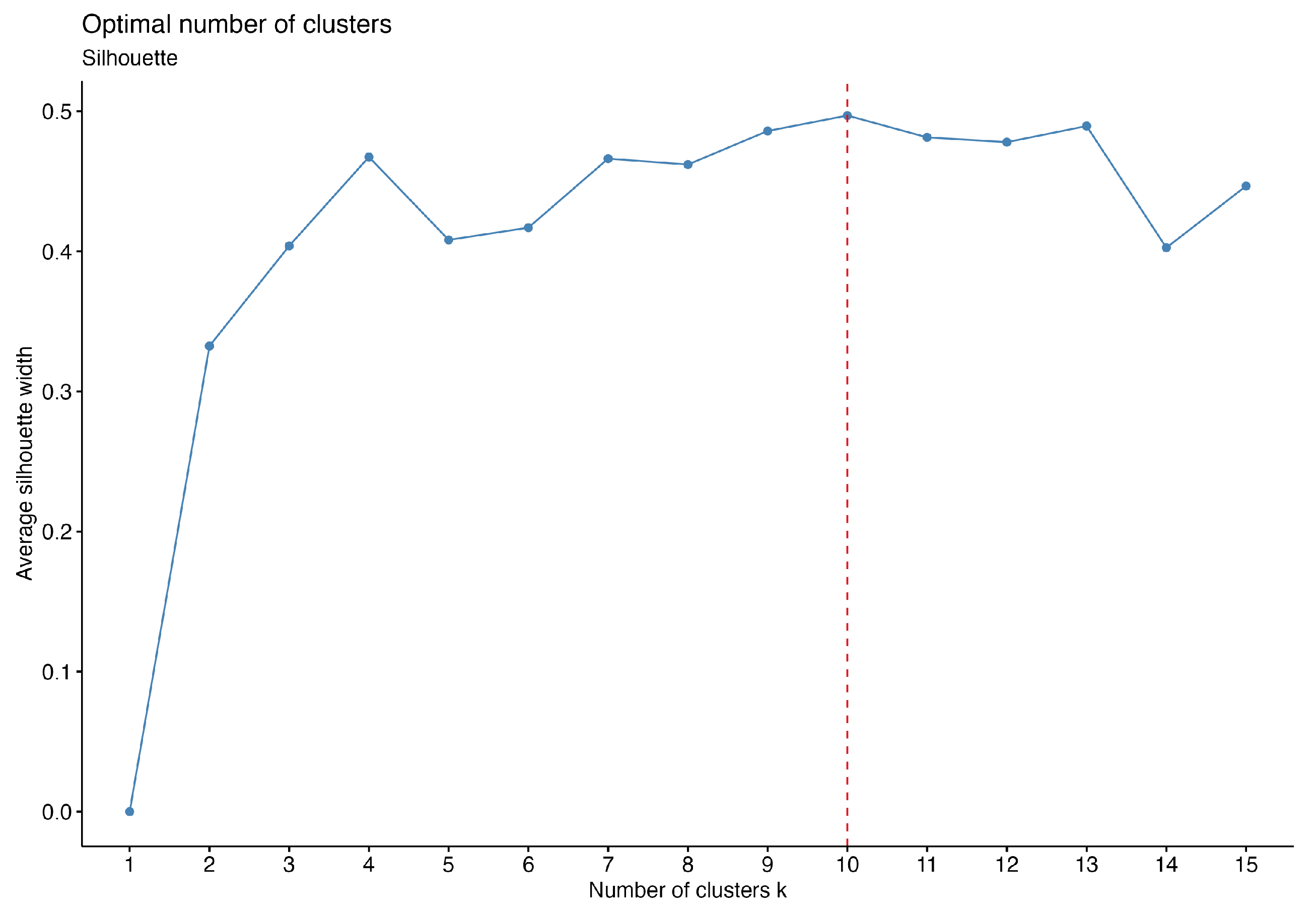

3.1.2. Optimal Number of Clusters

- Run the clustering algorithm (e.g., k-means) for a range of k values.

- For each k, calculate the WSS, which is the sum of squared distances between data points and their cluster centroids.

- Plot k on the x-axis and the corresponding WSS on the y-axis.

- Identify the elbow point where the decrease in WSS becomes less pronounced.

- Choose the k at this elbow point as the optimal number of clusters.

- is the average distance between i and all other points in the same cluster.

- is the minimum average distance from i to all points in any other cluster (the nearest cluster).

- Perform clustering for various values of k.

- For each k, compute the average silhouette coefficient for all data points.

- Select the k that maximizes the average silhouette coefficient as the optimal number of clusters.

3.2. Results

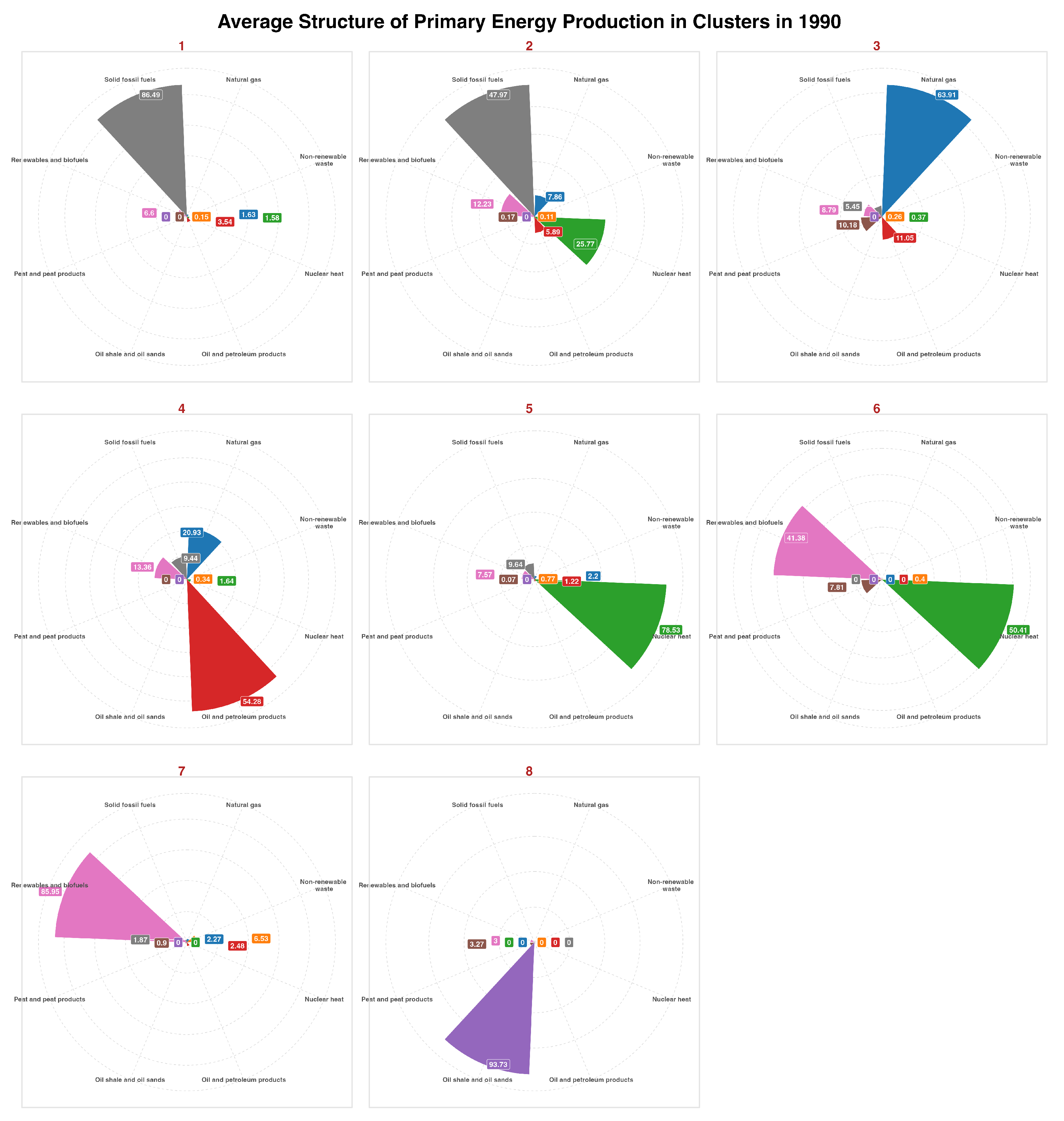

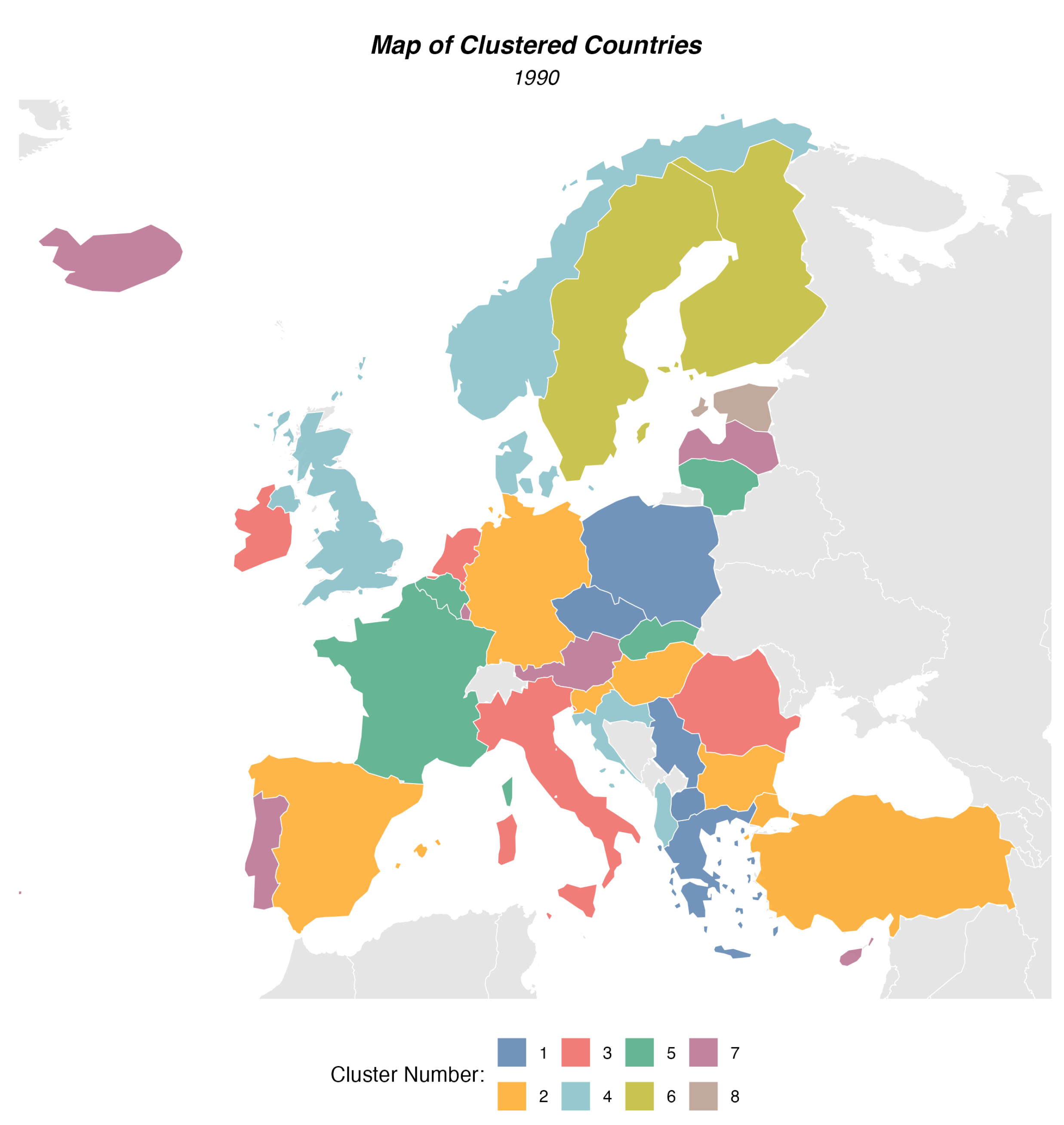

3.2.1. Cluster Analysis for the Year 1990

- Characteristics: This cluster is characterized by a very high share of solid fossil fuels (86.49%) with minimal contributions from other energy sources.

- Countries: Czechia, Greece, North Macedonia, Poland, Serbia.

- Interpretation: These countries primarily base their primary energy production on coal and other solid fossil fuels, indicating a strong reliance on traditional, high-emission energy sources.

- Characteristics: A cluster with a diversified production structure, featuring a significant share of nuclear energy (25.77%) and solid fossil fuels (47.97%). Natural gas and renewable energy also play a role.

- Countries: Bulgaria, Germany, Spain, Hungary, Slovenia, Turkey, Ukraine.

- Interpretation: These countries have diverse energy sources, with a notable nuclear component, suggesting a more balanced approach to energy production with less reliance on a single source.

- Characteristics: Dominant share of natural gas (63.91%) with a contribution from oil (11.05%).

- Countries: Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Romania.

- Interpretation: These countries primarily base their domestic primary energy production on natural gas, with some reliance on oil.

- Characteristics: Very high share of oil (54.28%) with a notable addition of natural gas (20.93%).

- Countries: Albania, Denmark, Croatia, Norway, United Kingdom.

- Interpretation: In these countries, most of the primary energy production comes from oil, with natural gas playing a secondary role.

- Characteristics: High share of nuclear energy (78.53%) with minimal contributions from other sources.

- Countries: Belgium, France, Lithuania, Slovakia.

- Interpretation: These countries based their primary energy production largely on nuclear energy in 1990.

- Characteristics: High share of nuclear energy (50.41%) and renewable energy sources (41.38%).

- Countries: Finland, Sweden.

- Interpretation: These countries had a balanced and sustainable energy production structure, focusing on both renewable and nuclear energy.

- Characteristics: Nearly entirely based on renewable energy sources (85.95%).

- Countries: Austria, Cyprus, Iceland, Luxembourg, Latvia, Portugal.

- Interpretation: These countries show a very high commitment to producing energy from renewable sources, which benefits the environment while reducing reliance on fossil fuels such as hydrocarbons.

- Characteristics: Dominated by production from oil shale (93.73%).

- Countries: Estonia.

- Interpretation: Estonia is a unique case, heavily relying on its significant oil shale resources.

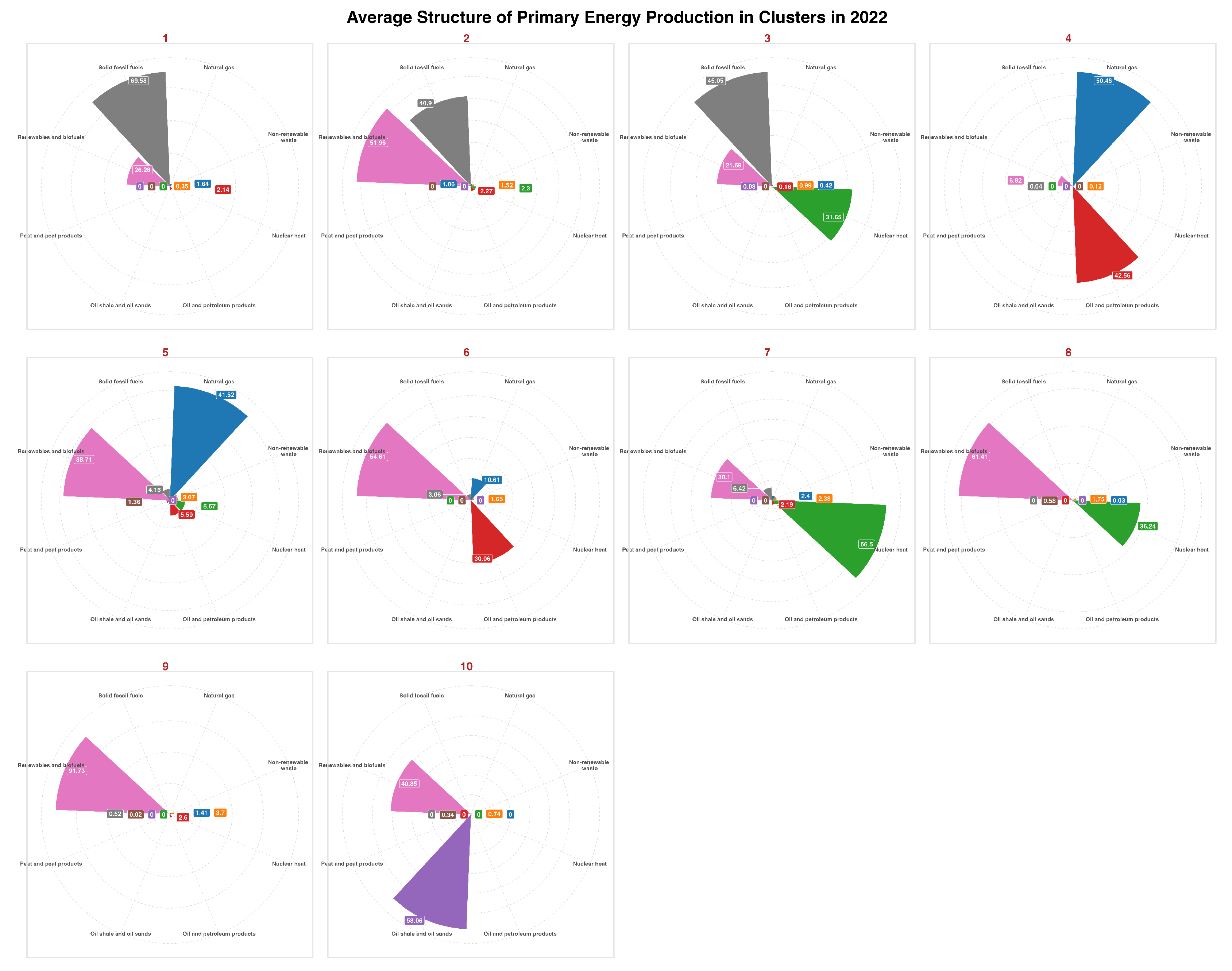

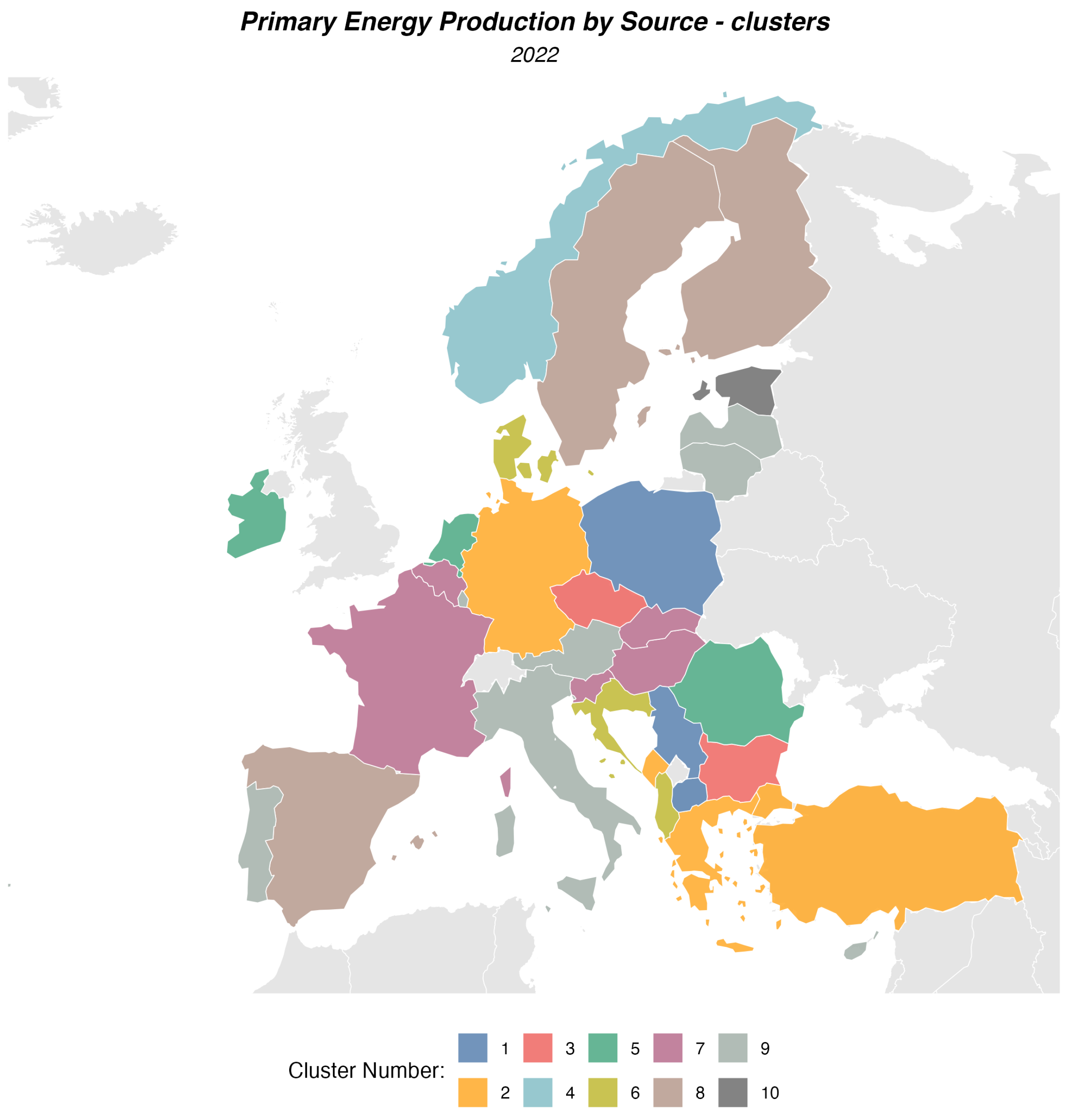

3.2.2. Cluster Analysis for the Year 2022

- Characteristics: High share of solid fossil fuels (69.58%) and renewable energy sources (26.28%).

- Countries: Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Poland, Serbia, Kosovo.

- Interpretation: These countries base their primary energy production mainly on coal, but also have a significant share of renewable energy. It is a combination of traditional and newer energy sources.

- Characteristics: Dominated by renewable energy sources (51.96%) with still a high share of fossil fuels (40.9%).

- Countries: Germany, Greece, Montenegro, Turkey.

- Interpretation: These countries focus their primary energy production on renewable sources and solid fossil fuels.

- Characteristics: A production structure with a significant share of solid fossil fuels (45.05%) and nuclear energy (31.65%).

- Countries: Bulgaria, Czechia.

- Interpretation: These countries rely on primary energy production from fossil fuels and nuclear energy, with a smaller share of renewable sources.

- Characteristics: High share of oil (42.56%) and natural gas (50.46%).

- Countries: Norway.

- Interpretation: Norway bases its primary energy production mainly on natural gas and oil, reflecting its natural resources and role as a major exporter of these commodities.

- Characteristics: Dominated by natural gas (41.52%) and renewable energy sources (38.71%).

- Countries: Ireland, Netherlands, Romania.

- Interpretation: These countries rely primarily on natural gas, but renewable energy sources also play an important role.

- Characteristics: High share of renewable energy sources (54.61%) and a significant share of oil (30.06%).

- Countries: Albania, Denmark, Croatia.

- Interpretation: Energy production in these countries is primarily based on renewable sources, but oil still plays a significant role.

- Characteristics: High share of nuclear energy (56.50%) and renewable energy sources (30.10%).

- Countries: Belgium, France, Hungary, Slovenia, Slovakia.

- Interpretation: These countries rely heavily on nuclear energy, but renewable sources also play a significant role, reflecting their diversified energy strategies.

- Characteristics: Dominated by renewable energy sources (61.41%) and a significant share of nuclear energy (36.24%).

- Countries: Spain, Finland, Sweden.

- Interpretation: These countries invest heavily in renewable energy, while also utilizing nuclear energy as an important part of their energy mix.

- Characteristics: Nearly entirely renewable energy sources (91.73%) with minimal contributions from other sources.

- Countries: Austria, Cyprus, Georgia, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Moldova, Portugal.

- Interpretation: These countries have a very high share of renewable energy in their primary energy production.

- Characteristics: Dominated by production from oil shale (58.06%) with a significant share of renewable energy sources.

- Countries: Estonia.

- Interpretation: Estonia is a unique case, where the main source of energy production is oil shale, which reflects its natural resources and local energy policy.

3.2.3. Key Changes Between 1990 and 2022

4. Conclusions

- Dependence on imported energy sources: One of the most pressing issues for many European countries is their heavy reliance on imported fossil fuels, such as natural gas and oil, from non-European countries. This dependency increases their vulnerability to geopolitical tensions and supply disruptions. Events like the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the resulting gas supply restrictions illustrate the risks of over-reliance on single suppliers. The need for diversified energy sources has become more urgent to avoid being subject to external political pressures and market volatility.

- Renewable energy and its limitations: While renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and hydropower have seen substantial growth, they also introduce new challenges to energy security. The variability and intermittency of renewables mean that energy production can be unpredictable, especially in regions where the sun and wind resources are not consistent. Without significant advances in energy storage technologies and grid infrastructure, the over-reliance on renewables could lead to instability in energy supply during peak demand or unfavorable weather conditions.

- Role of natural gas as a transitional fuel: Natural gas has been positioned as a transitional fuel to bridge the gap between high-emission fossil fuels and low-emission renewable sources. Its lower carbon footprint compared to coal makes it a preferred option for many European countries aiming to reduce emissions while ensuring energy security. However, the geopolitical implications of natural gas imports, especially from Russia and other non-EU countries, remain a significant risk factor. Efforts to increase LNG (liquefied natural gas) imports from diverse global suppliers are steps toward mitigating this risk, but infrastructural and logistical challenges persist.

- Nuclear energy’s stability and controversy: Nuclear energy continues to play a pivotal role in ensuring energy security for many European nations due to its ability to provide a stable and continuous energy supply. Countries like France have leveraged their nuclear infrastructure to reduce reliance on fossil fuel imports significantly. However, nuclear energy remains controversial due to concerns about nuclear waste, safety risks, and the high costs associated with plant construction and decommissioning. The decision by some countries, such as Germany, to phase out nuclear energy poses additional challenges in balancing their energy needs with sustainable practices.

- Impact of geopolitical events on energy security: The geopolitical landscape greatly influences Europe’s energy security. Conflicts, such as the situation in Ukraine, have highlighted the vulnerabilities of relying on imported energy resources from politically unstable regions. In response, the European Union has been actively seeking ways to reduce its dependence on external suppliers by promoting energy sovereignty and solidarity among member states. This involves enhancing intra-EU energy cooperation, investing in cross-border energy infrastructure, and developing a unified energy policy that can withstand external shocks.

- Diversification of energy sources: European countries need to further diversify their energy supply sources, both in terms of energy types (e.g., expanding renewables) and supply origins (e.g., reducing dependency on specific countries). This includes increasing investments in alternative technologies such as hydrogen, biomass, and small modular reactors (SMRs), which can provide stable and scalable energy solutions.

- Investment in energy storage and smart grids: The advancement of energy storage technologies is crucial to counteract the intermittency of renewable energy sources. Developing large-scale battery systems, hydrogen storage, and other innovative solutions can significantly enhance grid stability. Moreover, smart grid technologies can help manage energy distribution more effectively, balancing supply and demand in real time.

- Strengthening regional energy infrastructure: Enhancing the interconnectedness of Europe’s energy grid is vital for energy security. Building robust cross-border energy infrastructure, such as gas interconnectors, electric grids, and LNG terminals, will enable more efficient energy sharing among EU countries. This infrastructure will help mitigate the impact of local disruptions by distributing resources across the region more flexibly.

- Enhancing energy efficiency: Improving energy efficiency across industries and households is a key strategy to reduce overall energy demand. Lower consumption not only lessens the pressure on energy imports but also contributes to achieving decarbonization goals. Energy efficiency measures, including modernizing industrial processes, building renovations, and promoting energy-saving technologies, are fundamental to sustainable development.

- Policy and regulatory measures: Strong and coordinated policy frameworks are essential to drive the energy transition and ensure long-term energy security. The European Union’s Green Deal and Fit for 55 initiatives are examples of policy efforts aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions while boosting renewable energy adoption. Regulatory measures should also focus on encouraging private investment in clean energy technologies and setting clear targets for reducing dependency on imported fossil fuels.

- Geopolitical alliances and partnerships: Forming strategic alliances with energy-exporting nations that are politically stable and environmentally conscious is crucial for enhancing Europe’s energy security. Diversifying natural gas imports through LNG partnerships with countries like the United States, Qatar, and Australia, alongside fostering stronger ties with renewable energy leaders, will reduce Europe’s exposure to geopolitical risks.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SIEC | Standard International Energy Product Classification |

| IDE | Integrated Developmnet Environment |

| APERC | Asia Pacific Energy Research Centre |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| EU | European Union |

| EJ | Exajoule |

| TJ | Terajoule |

| PJ | Petajoule |

| WSS | Within-cluster Sum of Squares |

| LNG | Liquefied Natural Gas |

| SMR | Small Modular Reactor |

References

- Kosowski, P.; Kosowska, K.; Janiga, D. Primary Energy Consumption Patterns in Selected European Countries from 1990 to 2021: A Cluster Analysis Approach. Energies 2023, 16, 6941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Balances - Table nrg_bal_s, 2024.

- R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, 2024.

- RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R, 2024.

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; Kuhn, M.; Pedersen, T.L.; Miller, E.; Bache, S.M.; Müller, K.; Ooms, J.; Robinson, D.; Seidel, D.P.; Spinu, V.; Takahashi, K.; Vaughan, D.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H. Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Liu, L.; Zhou, X.; Hafeez, M.; Ullah, S.; Sohail, M.T. How does natural resource depletion affect energy security risk? New insights from major energy-consuming countries. Energy Strategy Reviews 2024, 54, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palonkorpi, M., The security complex theory and the energy security. In Pieces from peripheries and centres; University of Lapland Reoprts in Education, University of Lapland, 2006; pp. 302–313.

- Stern, D. Energy and Economic Growth: The Stylized Facts; Australian National University, 2011.

- Mazur, A.; Rosa, E. Energy and Life-Style. Science 1974, 186, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özcan, S. Securitization of Energy Through the Lenses of Copenhagen School. In The 2013 WEI International Academic Conference Proceedings; The West East Institute, 2013; p. 10.

- Flaherty, C.; Filho, W.L. Energy Security as a Subset of National Security. In Global Energy Policy and Security; Springer London, 2013; pp. 11–25.

- Roberts, P. The End of Oil. On the Edge of Perilous New World; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2004.

- Kemp, G. Scarcity and Strategy. Foreign Affairs 1978, 56, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahgat, G. Oil Security at the Turn of the Century: Economic and Strategic Implications. International Relations 1999, 14, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocklin, C. Anatomy of a future energy crisis Restructuring and the energy sector in New Zealand. Energy Policy 1993, 21, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J.F. Technological change and future growth: Issues and opportunities. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 1977, 11, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherp, A.; Jewell, J. The three perspectives on energy security: intellectual history, disciplinary roots and the potential for integration. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2011, 3, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBelle, M.C. Breaking the era of energy interdependence in Europe: A multidimensional reframing of energy security, sovereignty, and solidarity. Energy Strategy Reviews 2024, 52, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyke, B.N. Climate change, energy security risk, and clean energy investment. Energy Economics 2024, 129, 107225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Khurshid, A.; Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Xianjun, D. Does renewable energy development enhance energy security? Utilities Policy 2024, 87, 101725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yergin, D. Ensuring Energy Security. Foreign Affairs 2006, 85, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams P.D., M.M., Ed. Energy Security; Routledge, 2018; pp. 483–496.

- A Quest for Energy Security in the 21st Century Resources and Constraints. APERC, 2007.

- Ren, J.; Sovacool, B.K. Quantifying, measuring, and strategizing energy security: Determining the most meaningful dimensions and metrics. Energy 2014, 76, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzer, C. Conceptualizing energy security. Energy Policy 2012, 46, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Security: Reliable, affordable access to all fuels and energy sources, 2020.

- Study on Energy Supply Security and Geopolitics, 2004.

- Hedenus, F.; Azar, C.; Johansson, D.J. Energy security policies in EU-25—The expected cost of oil supply disruptions. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazantsev, A. Policy networks in European–Russian gas relations: Function and dysfunction from a perspective of EU energy security. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 2012, 45, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2008/92/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2008 concerning a Community procedure to improve the transparency of gas and electricity prices charged to industrial end-users (Recast) (Text with EEA relevance), 2008.

- Šipkovs, P.; Pelīte, U.; Kashkarova, G.; Lebedeva, K.; Migla, L.; Shipkovs, J. Policy and Strategy Aspects for Renewable Energy Sources Use in Latvia. ECP 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Erkök, B.; Kütük, Y. Dependency on Imported Energy in Turkey: Input-Output Analysis. Marmara Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi 2023, 45, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, J.; Pitlik, H.; Fronaschütz, A. Has the Russian invasion of Ukraine reinforced anti-globalization sentiment in Austria? Empirica 2023, 50, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, P. Does the Volatility of Oil Price Affect the Structure of Employment? The Role of Exchange Rate Regime and Energy Import Dependency. Energies 2022, 15, 6895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Siksnelyte-Butkiene, I.; Lekavicius, V. Energy Diversification and Security in the EU: Comparative Assessment in Different EU Regions. Economies 2023, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J.B. Some Methods for Classification and Analysis of MultiVariate Observations. Proc. of the fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; Cam, L.M.L.; Neyman, J., Eds. University of California Press, 1967, Vol. 1, pp. 281–297.

- Jain, A.K.; Dubes, R.C. Algorithms for clustering data; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, L.; Rousseeuw, P.J., Eds. Finding Groups in Data; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1990.

- Xu, R.; Wunsch, D. Survey of Clustering Algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 2005, 16, 645–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirkin, B. Clustering for Data Mining; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2005.

- Everitt, B.; Landau, S.; Leese, M. Cluster Analysis, 4th ed.; Arnold, 2001.

- Hennig, C. What are the true clusters? Pattern Recognition Letters 2015, 64, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K. Data clustering: 50 years beyond K-means. Pattern Recognition Letters 2010, 31, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, D.; Vassilvitskii, S. K-Means++: The Advantages of Careful Seeding. Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, P.N.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Introduction to Data Mining; Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.: USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, G.W.; Cooper, M.C. An examination of procedures for determining the number of clusters in a data set. Psychometrika 1985, 50, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer New York, 2009.

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cluster | Solid Fossil Fuels | Natural Gas | Nuclear Heat | Oil and Petroleum Products | Peat and Peat Products | Renewables and Biofuels | Oil Shale and oil Sands | Non-Renewable Waste | Countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 86.49 | 1.63 | 1.58 | 3.54 | 0.00 | 6.60 | 0.00 | 0.15 | Czechia, Greece, North Macedonia, Poland, Serbia |

| 2 | 47.97 | 7.86 | 25.77 | 5.89 | 0.17 | 12.23 | 0.00 | 0.11 | Bulgaria, Germany, Spain, Hungary, Slovenia, Türkiye, Ukraine |

| 3 | 5.45 | 63.91 | 0.37 | 11.05 | 10.18 | 8.79 | 0.00 | 0.26 | Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Romania |

| 4 | 9.44 | 20.93 | 1.64 | 54.28 | 0.00 | 13.36 | 0.00 | 0.34 | Albania, Denmark, Croatia, Norway, UK |

| 5 | 9.64 | 2.20 | 78.53 | 1.22 | 0.07 | 7.57 | 0.00 | 0.77 | Belgium, France, Lithuania, Slovakia |

| 6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 50.41 | 0.00 | 7.81 | 41.38 | 0.00 | 0.40 | Finland, Sweden |

| 7 | 1.87 | 2.27 | 0.00 | 2.48 | 0.90 | 85.95 | 0.00 | 6.53 | Austria, Cyprus, Iceland, Luxembourg, Latvia, Portugal |

| 8 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.27 | 3.00 | 93.73 | 0.00 | Estonia |

| Cluster | Solid Fossil Fuels | Natural Gas | Nuclear Heat | Oil and Petroleum Products | Peat and Peat Products | Renewables and Biofuels | Oil Shale and oil Sands | Non-Renewable Waste | Countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 69.58 | 1.64 | 0.00 | 2.14 | 0.00 | 26.28 | 0.00 | 0.35 | Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Poland, Serbia, Kosovo |

| 2 | 40.90 | 1.06 | 2.30 | 2.27 | 0.00 | 51.96 | 0.00 | 1.52 | Germany, Greece, Montenegro, Türkiye |

| 3 | 45.05 | 0.42 | 31.65 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 21.69 | 0.03 | 0.99 | Bulgaria, Czechia |

| 4 | 0.04 | 50.46 | 0.00 | 42.56 | 0.00 | 6.82 | 0.00 | 0.12 | Norway |

| 5 | 4.16 | 41.52 | 5.57 | 5.59 | 1.36 | 38.71 | 0.00 | 3.07 | Ireland, Netherlands, Romania |

| 6 | 3.06 | 10.61 | 0.00 | 30.06 | 0.00 | 54.61 | 0.00 | 1.65 | Albania, Denmark, Croatia |

| 7 | 6.42 | 2.40 | 56.50 | 2.19 | 0.00 | 30.10 | 0.00 | 2.38 | Belgium, France, Hungary, Slovenia, Slovakia |

| 8 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 36.24 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 61.41 | 0.00 | 1.75 | Spain, Finland, Sweden |

| 9 | 0.52 | 1.41 | 0.00 | 2.60 | 0.02 | 91.73 | 0.00 | 3.70 | Austria, Cyprus, Georgia, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Moldova, Portugal |

| 10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 40.85 | 58.06 | 0.74 | Estonia |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).