1. Introduction

In 2022, the construction industry in the European Union was responsible for a high level of greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions, 34% being energy-related emissions. Direct fossil fuels used in buildings to produce electricity for internal consumption are the main cause of these emissions [

1]. Furthermore, construction contributed 34% to global energy demand in 2022, revealing a considerable gap between the status and the defined target of decarbonizing the building sector by 2050 [

2]. A priority objective to mitigate environmental impacts lies in the reduction of energy consumption in the construction sector, according to the EPBD recast (Energy Performance of Buildings Directive) [

3] and COP29 [

4].

The improvement of the building envelope, using thermal insulation, is one of the key factors that can significantly impact the sustainability of the construction sector [

5]. In the European market, there are mainly three types of thermal insulators: mineral and inorganic based, which represent about 60% of the market, petroleum-based materials (particularly extruded materials) which account for 30%, and natural organic materials, which represent 10%. In this last group, expanded cork agglomerate stands out, Portugal holding the position of World’s largest producer and exporter of cork-based products [

6]. Thus, the pursuit of creating new environment-friendly composites for thermal insulation, incorporating waste, namely end-of-life wind turbine blades and textile waste, represents a relevant opportunity to reduce the negative impact of the construction sector on the environment and was never explored in the literature.

Several researchers worldwide have carried out numerous studies on the development of biocomposites and environmentally friendly materials for use as thermal insulators, proving that these materials are competitive and either match or surpass the insulating properties of more conventional commercially available materials [

7,

8,

9]. Although there are several works in the literature on the use of end-of-life wind turbine blades and/or textile waste for thermal insulation applications, few integrate bio-binders into the proposed solutions. Despite the small number of studies, there are different proposals using these materials (bio-binder), by combining them with other materials to obtain biocomposite thermal insulators, contributing to mitigate environmental problems of buildings operation and of construction sector [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], and paving ways for forward and valorization of waste from the wind and textile industries.

Wind turbine blades are designed to have a useful life of 20 to 25 years, the point at which they are deactivated. They are generally composed of fiberglass or carbon fibers, epoxy resins, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), balsa wood, and a polyurethane coating [

16]. The current trend in the wind power industry highlights the urgent need to develop effective and efficient recycling and disposal solutions due to the increasing volume of end-of-life blades. It is estimated that by 2025, 100,000 tons of blades will be decommissioned annually, a number which is expected to increase to 200,000 tons by 2033 [

17]. Furthermore, the prediction of end-of-life waste flow forecasts a 2.9 million tons by 2050, while the accumulated blade waste amounts to 43 million tons per year [

18,

19].

By its own turn, textile industry is very wasteful and produces pre-consumption waste (generated by the manufacturing process) and post-consumption waste (generated when customers discard clothes, or when they are no longer in use or in the case of fast fashion changes). There are two main types of fabrics based on the nature of the used materials: natural, such as cotton and sheep wool, and synthetic, such as polyester and nylon. A total of 92 million tons of clothing is thrown away worldwide every year, and global textile consumption is expected to be 134 million tons per year by the end of 2030 [

20]. The current methods of managing the textile waste include landfills and incineration, 87% of the fiber used in clothing production ending in these places. This represents approximately 2 billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions accounting for about 2% to 8% of global emissions each year [

21]. Pre-consumer waste is also expected to exceed 100 million tons per year [

21]. Thus, viable and sustainable approaches to textile and clothing waste management are essential.

This study aims to identify trends and opportunities for developing thermal and acoustical insulations for buildings using end-of-life materials from these two relevant sectors, offering a comprehensive view of the current state of the art and its foreseeable future directions. It aims thus at identifying trends, opportunities and contributions to increase the sustainability and circular economy of four sectors: the wind energy sector, the textile sector, the construction sector, and the buildings’ use and operation.

Scientific journals often consolidate previous studies demonstrating which solutions have been considered for these wastes, and their results. Therefore, before proceeding towards practical applications, it is of paramount importance to identify progresses made and research gaps that remain unaddressed in this research field.

2. Methods

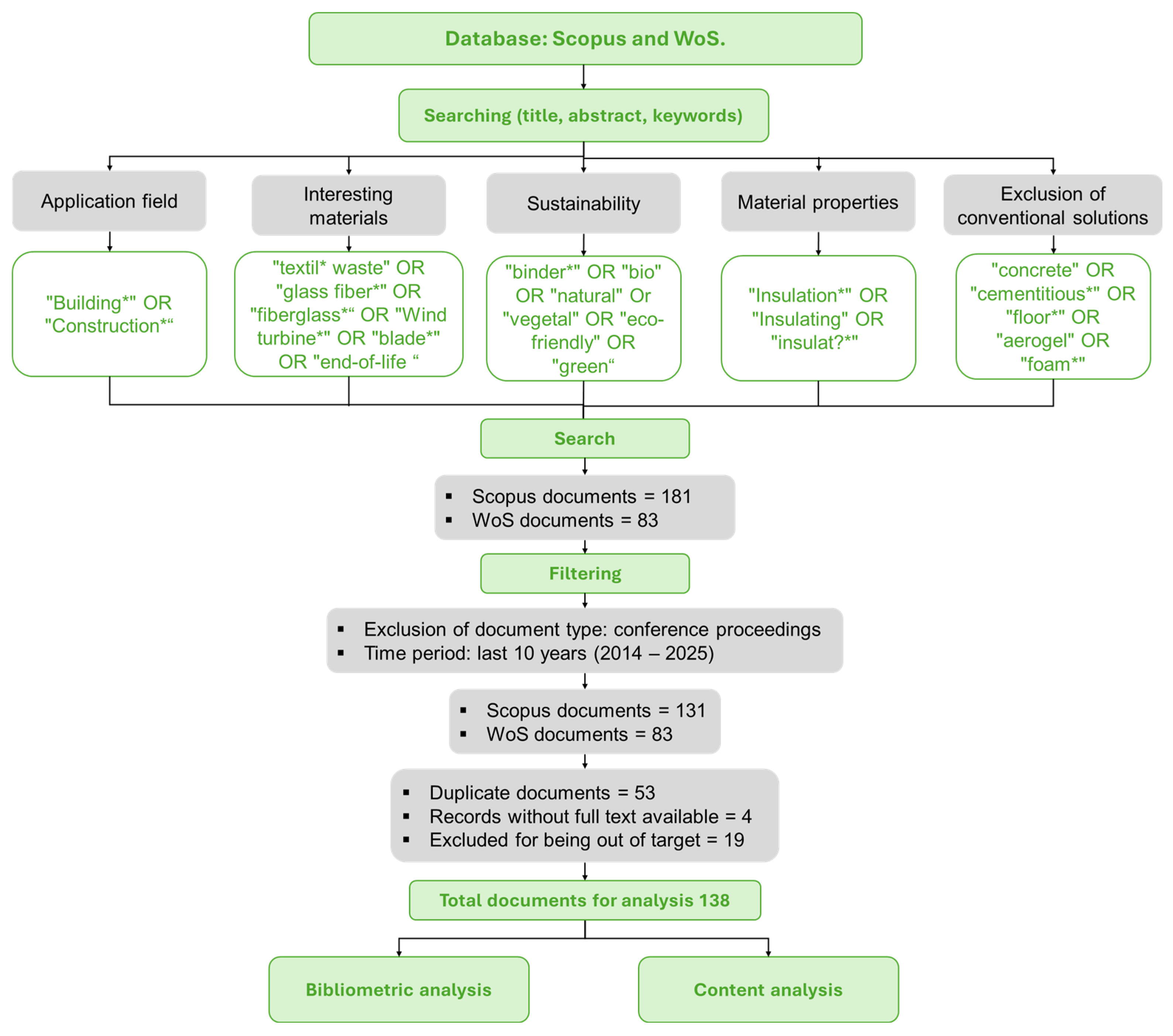

This review was based on a list of keywords, with the most relevant terms related to the field of application, in this case, “Building*” and “Construction*”. Then, terms related to specific materials of interest were added, such as “glass fiber*”, “fiberglass*”, “textile*”, “waste” “end-of-life”, “wind turbine*” and “blade*. Additionally, importance was given to ensure a sustainable approach to research, including terms that describe ecological characteristics, such as “bio”, “natural”, “vegetal”, “eco-friendly”, “binder*”, and “green”. At the same time, terms indicating insulating properties were defined, such as “Insulation*”, “Insulating,” and “insulat?”. Furthermore, words related to conventional and advanced materials used in the construction sector, such as “concrete”, “cementitious*”, “floor*”, “aerogel” and “foam*” were excluded. This approach covered the research domains, including the field of application, materials of specific interest, and sustainable characteristics of materials.

This research was conducted in two main databases: in Scopus, the search was structured constraining the query to the title, abstract, and keywords, resulting in 181 documents; in Web of Science (WoS) with a similar query, the search resulted in 83 documents. The documents were filtered to include only articles, reviews, book chapters, and books, in the 12-year period of publication from 2014 up to 2025, resulting in 136 documents from Scopus and 83 documents from WoS. A total of 53 duplicate documents was identified and excluded to be present only once in one of the databases. Additionally, 4 documents without full-text access and 19 documents deemed outside the scope of the study were removed. Following this screening process, 138 documents remained for bibliometric and content analysis.

Different metrics were evaluated in the bibliometric analysis, namely: evolution of the number of publications, main contributions by country, most influential and relevant journals, and frequency and relevance of keywords, using the specialized software tools RStudio (2024.04.2) and Bliblioshiny from Bibliometrix [

22].

Figure 1 describes the methodology employed for the selection and study of documents.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Research Landscape and Publication Trends

The bibliometric analysis covers the last decade, although the first record found in the literature dates to 1985 [

24]. This record presents the process of reusing textile waste for use in different applications outside the textile industry. Chemical binders combine these materials to manufacture boards, insulating panels for construction, and reinforcements for road paving. Shredded textile waste is also used to get synthetic polymers back and to make geotextiles, such as protective felts in reservoirs and drainage fabrics.

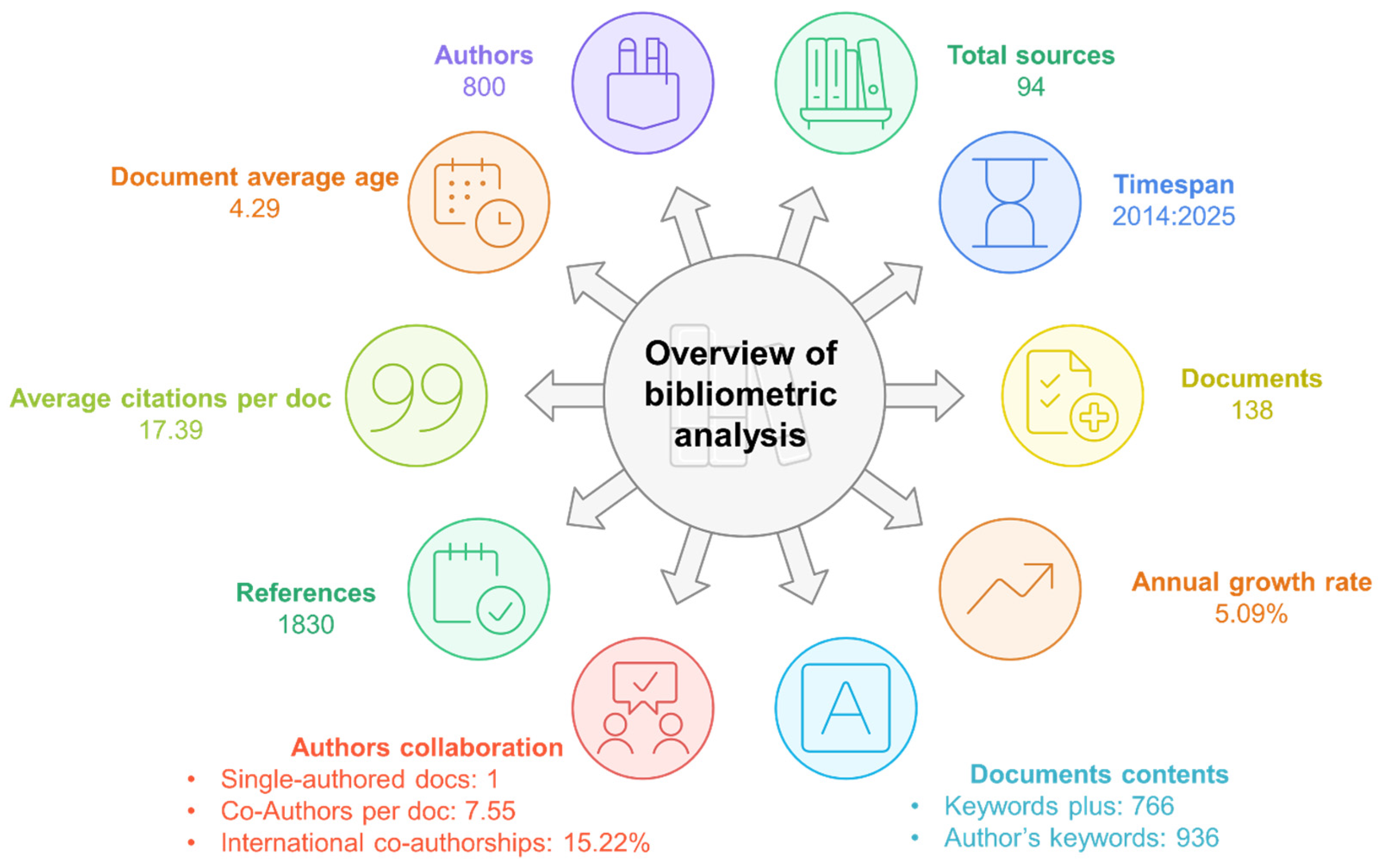

Figure 2 presents an overview of the bibliometric analysis, summarizing the key characteristics of scientific production on insulation materials incorporating end-of-life wind turbine blades and textile waste with bio-binders. Analysis presented an annual growth rate of 5.09%. This relatively moderate growth rate suggests a continuous and stable increase in publication output over the past decade. The average age of the documents is 4.29 years, indicating that the studies examined have a balance between recent and established publications. This metric reflects the field’s maturity and its capacity for continuous knowledge to increase and renewal.

In terms of bibliographic impact, the average number of citations per document is 17.39, which indicates a notable level of engagement within the scientific community. Collectively, documents cite 1830 references, highlighting a broad and interdisciplinary foundation of prior research. Regarding authorship, 800 researchers contributed to the corpus, with only 1 single-authored works, reinforcing the relevance of collaborative work in this research domain. On average, each document has 7.55 co-authors, and 15.22% of publications involve international collaboration. This high level of co-authorship and abroad collaboration clearly suggests that development of sustainable construction materials from these wastes requires multidisciplinary and cross-border collaborative expertise.

The thematic content of research is reflected in the use of 936 author-provided keywords and 766 keywords. They indicate also a large range of research interests, from materials characterization to environmental performance. Additionally, the presence of 93 total sources (journals, conferences, books) points to a diversified dissemination landscape, although (not surprisingly) peer-reviewed journals remain the primary channel for scientific dissemination and communication.

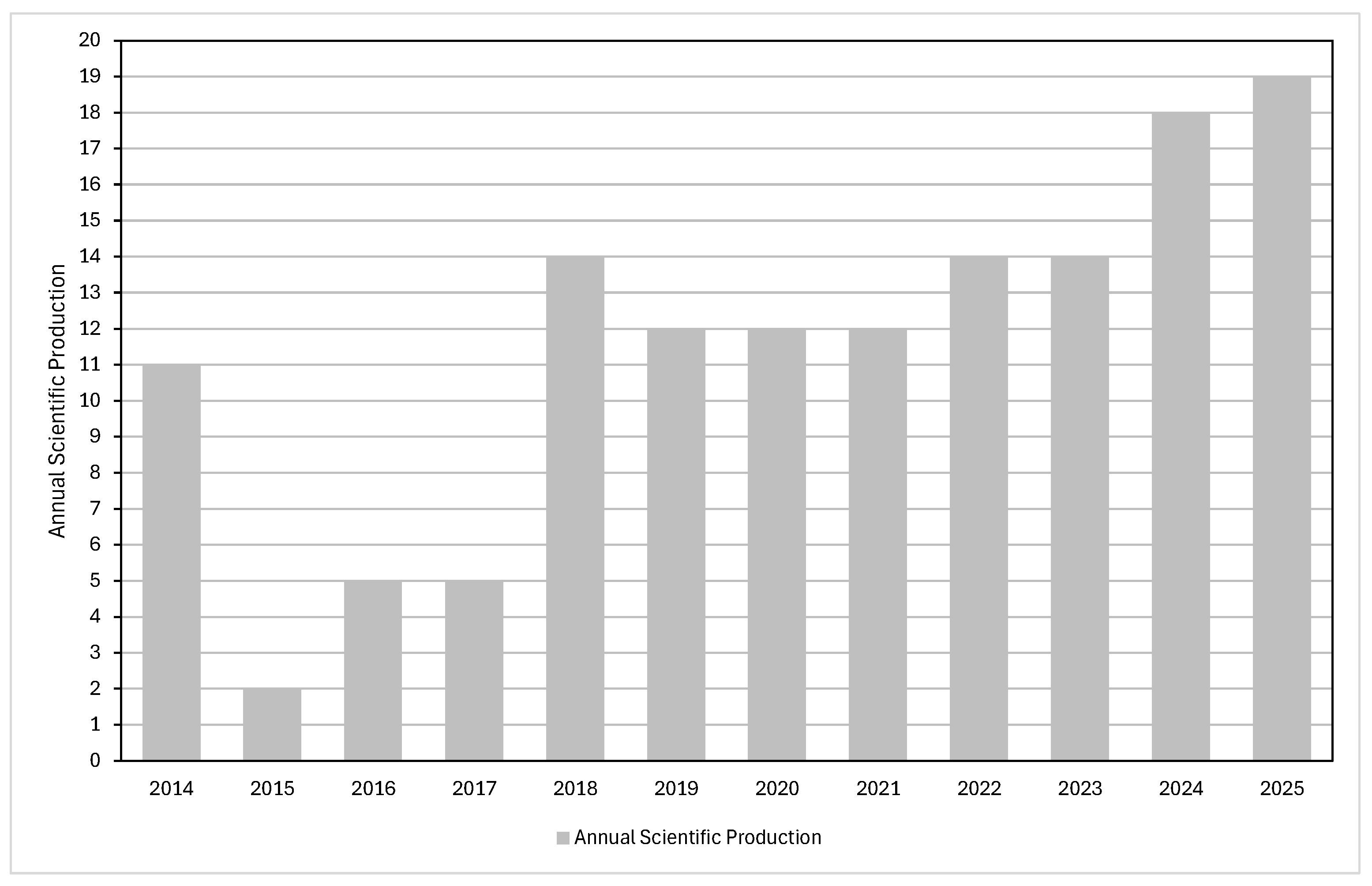

Analyzing in detail the number of published works during the last decade allows identification of a complex trend (

Figure 3).

From the plot, three different periods were identified and the following aspects are concluded:

Despite an overall increase in publications over the considered period, a period of lower output is observed between 2014 and 2017, with an average of 5.75 publications per year—which may indicate a period of adjustment and consolidation of research on the topic. From 2018 onwards, a recovery and new phase of growth began, with an average of 13 publications per year between 2018 and 2019, suggesting greater maturity of the field and growing interest among researchers. In 2020 and 2021, scientific production remained stable at 12 publications per year, demonstrating resilience despite global disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected laboratory access, international collaboration, academic conferences, and research workflows. Starting in 2022, a further increase in scientific output is observed, rising to an average of 16.25 publications per year from 2022 to 2025, indicating adaptation to post-pandemic working conditions and a continued expansion of the research field. It must be referred, additionally, that the interest in the use of the waste from the end-of-life wind turbine blades results from the actual concerns about the future large waste production, and not yet from the real pressure caused by such a large waste production, which will cause an increased interest and additional pressure on the research field.

3.2. Main Contributors to Scientific Production by Country

The scientific production of various countries serves as a general indicator of research relevance on the subject at national level, enabling at identifying countries with the highest scientific or technological outputs. It also maps global distribution of these activities, which may be correlated with the regions of the World where the demands on the subject increased.

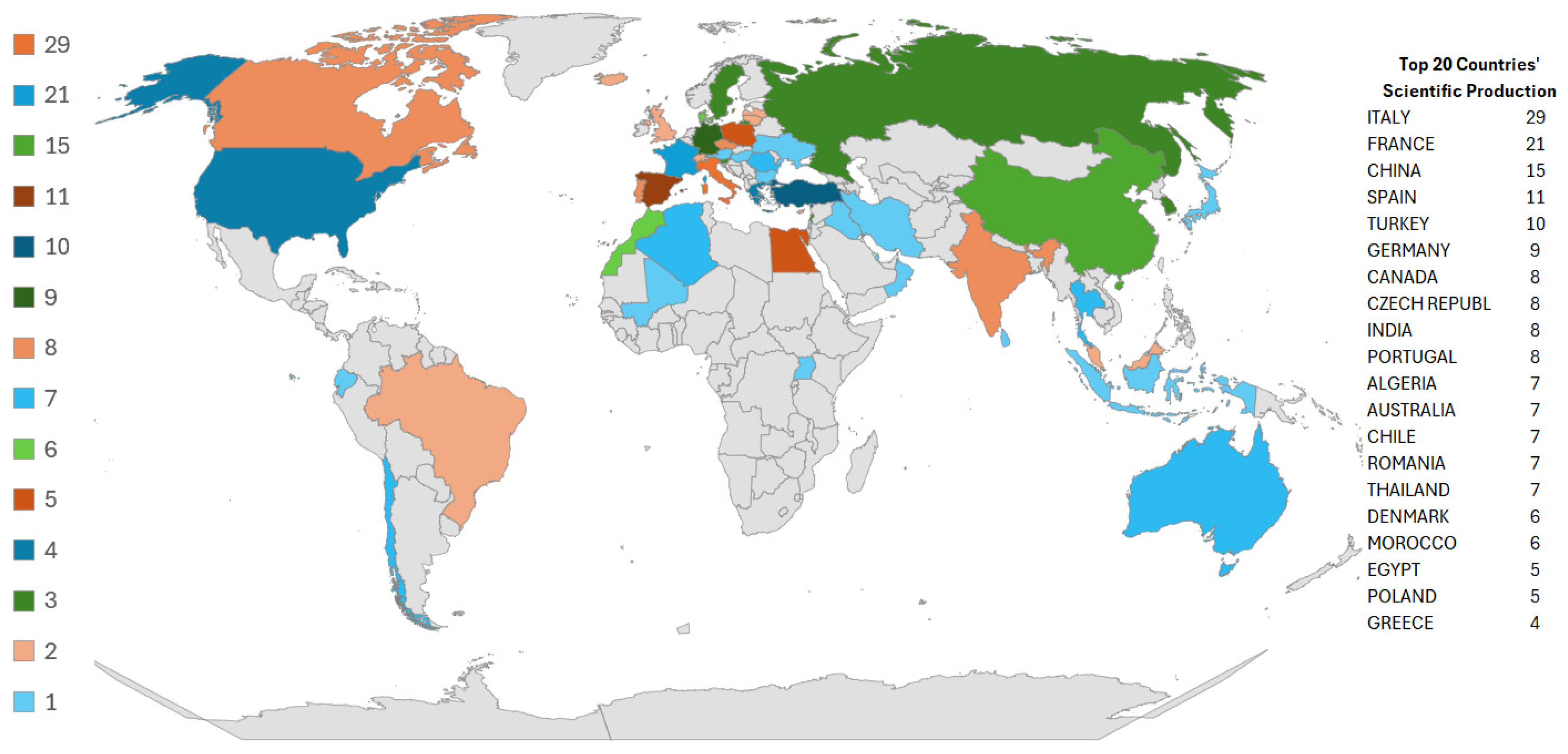

Figure 4 displays a color map that quantifies the scientific production by country, based on the author’s affiliation.

The world map reveals a significant concentration of scientific records in specific European countries, particularly Italy (29 publications), France (21), and Spain (11), which exhibit a more robust scientific and technological output compared to other global regions, positioning Europe as the leading force in global research on the reuse of wind turbine and textile industries waste. A marked disparity in publication volume is evident among countries: for instance, publication output of Italy is over seven times higher than that of the USA (4 publications), while several nations contributed only with one or two records. European countries alone account for approximately 45.5% of global publications, underscoring their dominant role in developing and shaping the field. Türkiye stands out as an important case, not only due to its notable contribution (10 publications), but also because of its geographic and scientific position between Europe and Asia, suggesting growing regional collaboration countries such as China (15) and India (8) which show increasing interest in this field, yet their current outputs remain considerably lower than those of leading European nations. That suggests substantial potential for growth and the development of localized research initiatives on the field in these emerging regions.

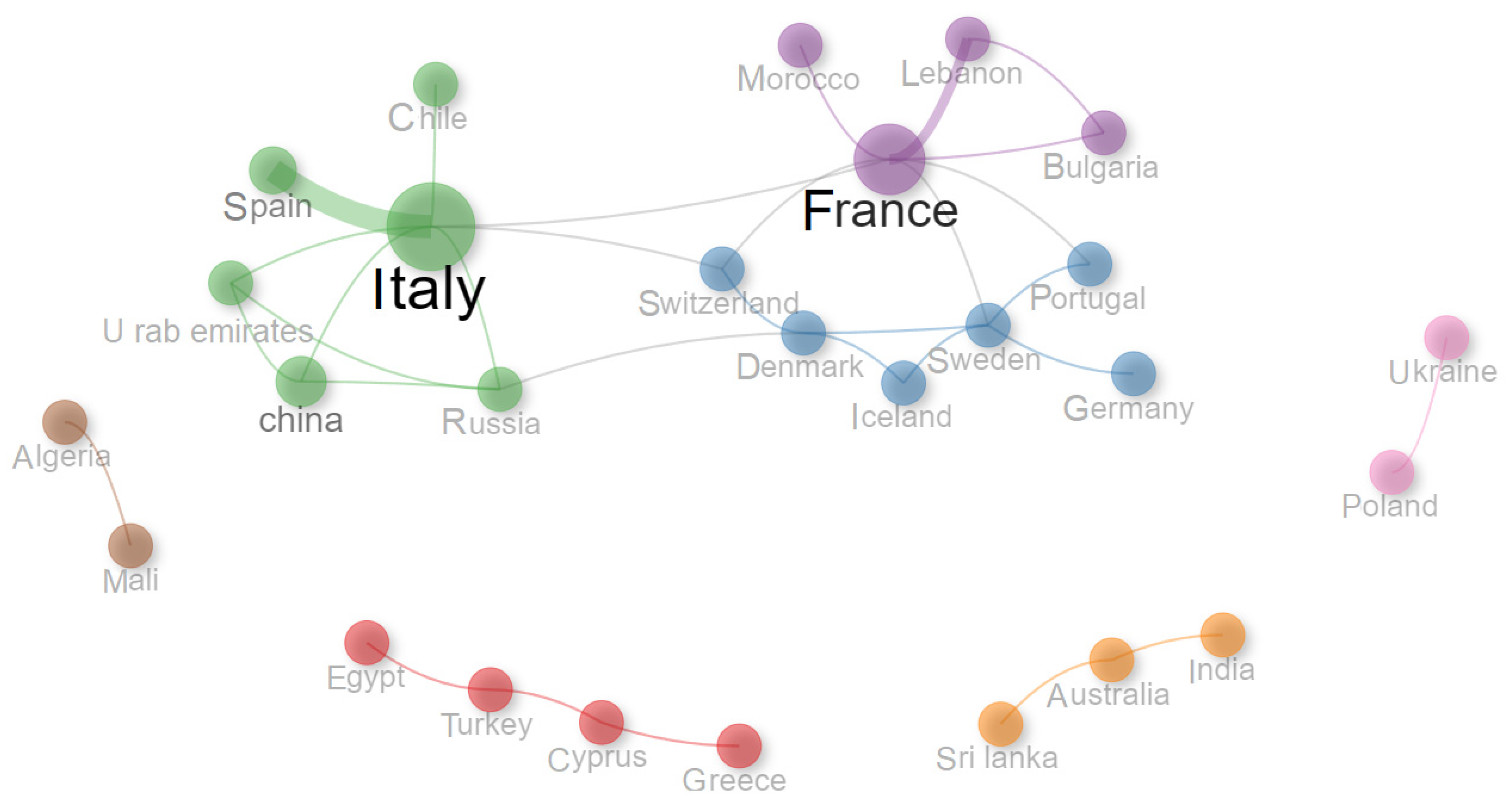

Figure 5 gives a comprehensive picture of the collaborative international ties of countries, divided into six groups of colors.

The cluster analysis identifies collaboration communities based on connection density. This approach aims at outlining measures of Betweenness, this used to highlight countries that act as bridges in the network. France shows the highest Betweenness (54.5), confirming its central role as main connector between clusters. It links Europe, the Middle East and South America. Italy follows with 46, playing a similar role in green cluster, connecting Spain, China, Russia and UAE. Both are key bridges for integration in the clusters acting on the field.

In Northern Europe (blue cluster), Sweden (23.5) and Denmark (12) stand out as key brokers. Switzerland (4.5) also contributes, while others like Germany and Iceland show zero, meaning no bridge function. They stay inside the cluster but not acting as bridges for the cluster. In Mediterranean (red), Türkiye and Cyprus have Betweenness of 2.0 central locally, but not globally. Greece and Egypt show zero, reinforcing their peripheral position in the network. Australia has 1.0 in orange cluster, which is a modest value. India and Sri Lanka have zero (no linking) role. Algeria and Mali (brown) are isolated, with no Betweenness at all.

Overall, only few countries, namely France, Italy, Sweden and Denmark act as true connectors. Most others are embedded within clusters. The network relies on a small number of strategic nodes to maintain cohesion across regions.

3.3. Scientific Landscape: Influential Journals in Sustainable Materials Research

As previously referred, the 138 documents identified in this study were collected from 94 different sources.

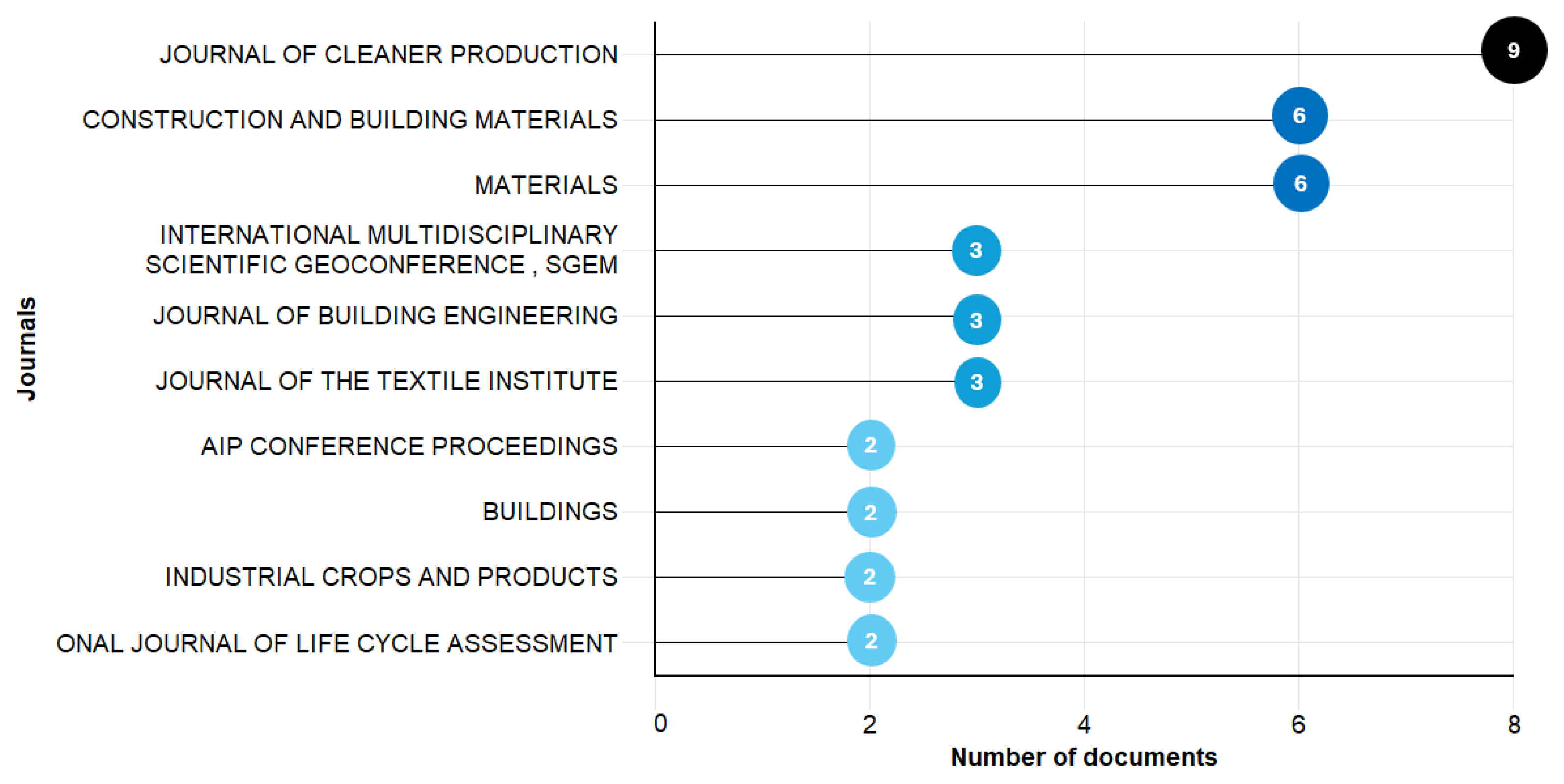

Figure 6 presents the 10 most relevant scientific journals in which research articles were published, ordered by the number of publications. This distribution offers an interesting overview of the most relevant information sources used in the study on the topics addressed.

Analyzing the scope of the journals, a strong focus on topics related to materials and engineering is revealed. The recurring presence of terms such as “materials,” “construction,” and “engineering” indicates that research is mainly focused on issues related to materials production, properties, and characterization.

“Journal of Cleaner Production” holds the top position, presenting 9 papers published on the subject, suggesting research focused on environmental and sustainable aspects related to the production and use of materials. “Industrial Crops and Products”, which is focused on (non-food) bio-based materials, including production of renewable materials, confirms this trend though it has only 2 articles here (not so many, but still present).

Despite the focus on materials and engineering, diversity of journals indicates that the research subject spreads over different areas of knowledge. Journals like “Construction and Building Materials” and “Materials” both have 6 articles each, reinforcing the centrality of construction and materials science. “Journal of Building Engineering” and “Journal of the Textile Institute” also appear with 3 articles each, showing the research on the field is also present into applied fields.

The presence of journals such as “Journal of the Textile Institute” and “Materials Science Forum” demonstrate the interdisciplinarity of the research field, which involves knowledge from areas such as chemistry, physics, biology, and engineering. Even conferences like “SGEM” and “AIP Conference Proceedings” are included with 3 and 2 articles, respectively, indicating that part of the research is presented in multidisciplinary or regional events.

In summary, analysis indicates that studies are focused on topics related to production, properties, and application of materials, with emphasis on environmental and sustainable issues. The analysis of Journal of Cleaner Production (9 articles) indicates that sustainability is not merely a subsidiary topic, but the primary driver of research in this field.

3.4. Frequency and Relevance of Keywords

An exhaustive analysis of keywords is essential in the information retrieval process, profoundly affecting the accuracy and pertinence of literature outcomes. This analysis can be performed using two unique approaches: the “author’s keyword” method and the “keyword plus” method [

22]. While both seek to enhance the search and retrieval of information, they vary in their attributes and distinct goals. The first approach mentioned explores the terminology or phrases selected by the article’s authors to characterize their study, thus representing their opinions on the principal issues and concepts explored in the research. The second outlines the terms or phrases automatically derived from the titles of the referenced articles, highlighting the most frequent and pertinent words within a collection of related articles.

This study employed the “keyword plus” methodology, which offers a more extensive perspective of the research subject, promoting development of a greater quantity of keywords than “author’s keywords.”

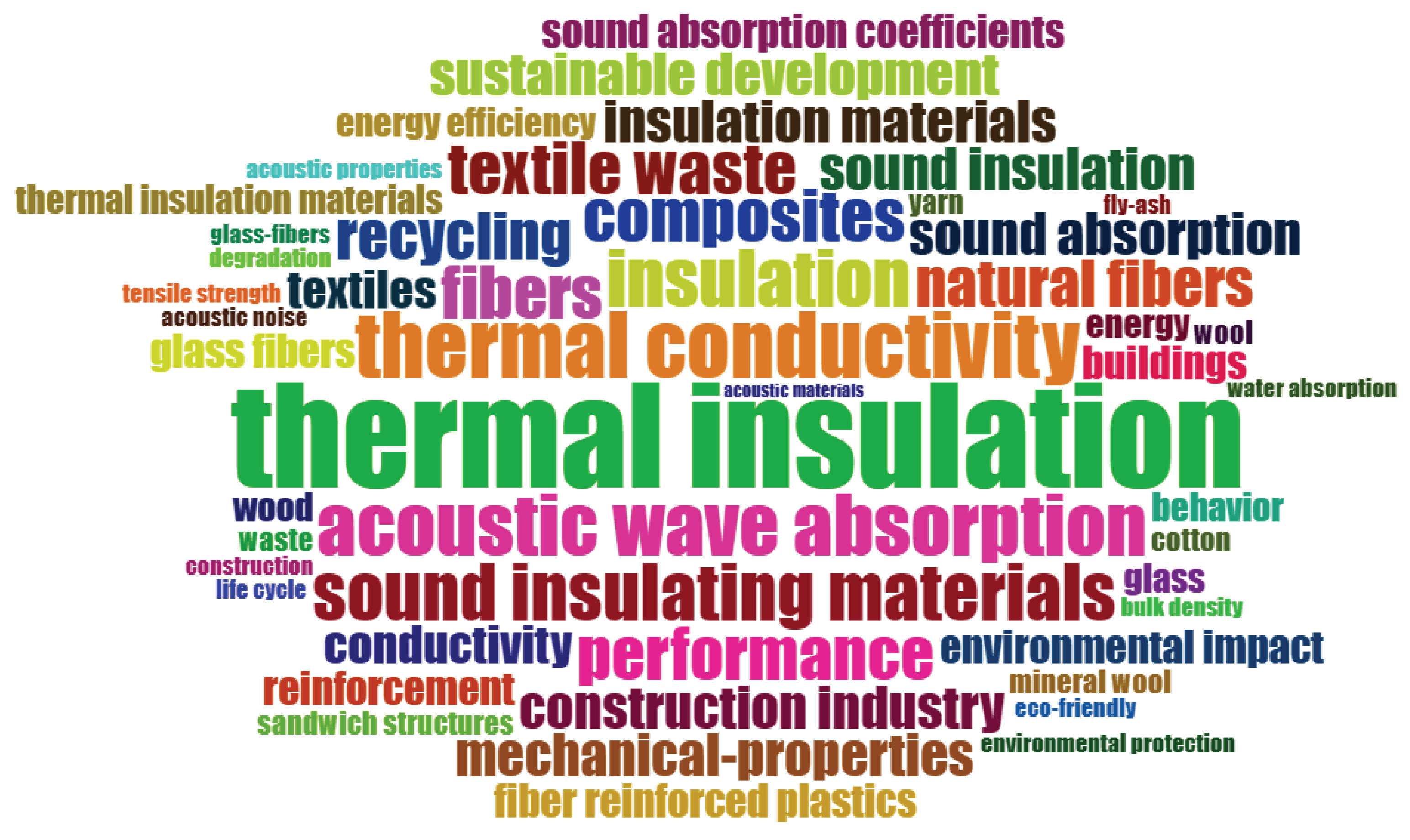

Figure 7 displays the predominant “keyword plus” cloud of this research, providing an overview of the principal subjects of the study.

The keywords analysis reveals that research is mostly centered on materials and their properties, particularly emphasizing thermal and acoustic insulation. The high frequency of terms such as “thermal insulation” (22), “thermal conductivity” (14), “acoustic wave absorption” (13), “insulation” (12), “sound insulating materials” (12), and “composites” (11) suggests that studies aim to understand and improve materials/solutions that help save energy and reduce noise, aligning with the construction industry’s trends toward comfort, innovation, and sustainability.

The construction area is a predominant topic, evidenced by the recurrent use of terms such as “buildings” (7), “construction industry” (9), and “construction” (4), indicating that research concentrates on the application of the materials studied in construction to enhance the buildings’ sustainability, and energy and acoustic performance. The study reveals a notable interest in composite materials and natural fibers, indicated by the frequent occurrence of keywords like “composites” (11), “fibers” (11), “natural fibers” (10), and “textile waste” (11). These materials are commonly used in insulation applications due to their distinctive characteristics, including lightweight, strength, and minimal environmental impact.

Terminology such as “recycling” (10), “sustainable development” (9), and “environmental impact” (7) clearly reflect the emphasis on sustainability, meaning that research pursues to provide materials and construction solutions that reduce environmental impact and enhance energy efficiency. Research examines not only thermal and acoustic insulation capabilities but also other material characteristics, including mechanical strength (denoted by terminology such as “mechanical-properties” (9) and “reinforcement” (7)) and density (referenced by terms like “bulk density” (4) and “specific mass”, implied through “density”-related terms). These properties are essential for ensuring the durability and performance of materials across many applications, aligned or not with the civil construction sector.

Nonetheless, a notable deficiency exists in terminology such as “binder” or “bio-binder”, which exhibit low or even nonexistent frequency. This highlights a domain which is still little explored, thus revealing strong research needs and opportunities.

Consequently, keyword analysis indicates that research centers on the development and characterization of thermal and acoustic insulating materials, particularly for civil construction applications.

4. Contents Analysis

4.1. Comparative Properties of Textile Fiber-Based Composites

Table 1 summarizes data from various studies, classified by materials composition, with emphasis on composites derived from natural, synthetic, and mixed textile fibers. The key properties include thermal conductivity (λ, in W/(m·K)), where lower values indicate better thermal insulation, particularly values below 0.07 W/(m·K) classified as thermal insulating materials for the construction sector [

25]; density (in kg/m

3), where reduced values allow for lighter-weight composites; compressive and flexural strength (in MPa), where higher values reflect greater mechanical capacity to suporting loads, and thus also durability; and the Noise Reduction Coefficient (NRC), where higher values indicate greater acoustic absorption of incident sound. By presenting average ranges for each category,

Table 1 facilitates direct comparisons of composites performance. Overall, these materials illustrate the repurposing of textile waste, in line with circular economy principles and contributing to reduce carbon emissions in the building sector.

Regarding thermal performance, natural fibers (sheep’s wool, flax, cotton, hemp) exhibit the lowest thermal conductivity values (0.029 - 0.089 W/(m.K)), positioning them as excellent thermal insulators. For example, flax composites with biologically derived resins achieve values of 0.029 W/(m.K), comparable to commercial thermal insulation materials like mineral wool (0.032 - 0.040 W/(m.K)) [

26]. This thermal performance can be attributed, in part, to the characteristic microstructure of many natural fibers, which often feature a microstructure rich in porous interstitial cavities or honeycomb-like, with numerous air filled micro-voids trapped inside [

27]. These porous reduce conduction and convection heat transfer, thereby favoring thermal insulation.

In contrast, composites incorporating dense mineral matrices (Portland cement, gypsum, sand) with different types of textile fibers show significantly higher thermal conductivities (0.83 - 1.17 W/(m·K)), approaching the behavior of conventional concrete (1.4 - 2.0 W/(m·K)) [

26]. This suggests an inverse relationship between structural functionality and thermal insulation characteristics: the higher the mineral content, the poorer the thermal insulation performance.

On the other hand, composites based on synthetic textile waste (denim) mixed with some agricultural residues present an intermediate range of thermal conductivity (0.076 - 1.14 W/(m.K)). This wide range reflects the strong influence of the ratio between organic and inorganic matrix: the higher the content of lightweight and porous organic components, the lower the thermal conductivity. These results indicate that the strategic combination of synthetic fibers with natural materials can offer a balance between structural and thermal insulation properties, opening new avenues of research for the development of sustainable construction materials with improved thermal insulation performance.

Regarding density, composites with natural fibers present the lowest values between 21 - 340 kg/m3, as in the case of hemp/flax, which favors non-structural applications. Mixtures with EPS or cement increase density to >1000 kg/m3, which compromises transportability or implies on-site manufacturing.

Meanwhile, the lowest densities (20 - 83 kg/m

3) correspond to flax/hemp composites with sodium silicate, highlighting the composite with mycelium as the lowest density recorded in the study (0.72 kg/m

3). Up to quasi-structural materials (1900 kg/m

3 in cotton/flax composites with cement). This wide range allows designing materials depending on the need, classifiable between non-structural thermal insulators < 200 kg/m

3 and semi-structural or cladding > 600 kg/m

3 [

28].

The least dense materials have the advantage of being prefabricated, unlike the denser ones, which compromises their transportability or implies their manufacturing be carried out in situ; in particular, it stands out that the low density of composites with natural fibers and biopolymeric matrices (PLA, alginate, chitosan) is directly correlated with the lightweight and porous nature of these materials, which significantly contributes to reducing the composite overall density.

In terms of mechanical properties, composites with synthetic fibers, especially when combined with cementitious or synthetic resin matrices such as gypsum, cement, or PLA, offer the best performances, with compressive strengths reaching up to 11 MPa [

29] and flexural strengths up to 13 MPa [

30], making them suitable for load-bearing panels. Hybrid or mixed-fiber materials present an intermediate balance (1.5 - 3 MPa in compression), although their high variability suggests certain fragility and critical dependence on manufacturing conditions.

In contrast, composites based on natural fibers with biopolymeric matrices or mechanical bonds (such as gum arabic, alginate, or carding processes) exhibit very low strengths (< 0.3 MPa), limiting their use to non-structural applications, mainly as thermal or acoustic insulators. In general, the type of fiber and, above all, the nature of the matrix are determining factors of mechanical behavior: mineral or synthetic matrices confer rigidity and strength, while natural or porous matrices prioritize lightness and insulation at the expense of structural capacity.

Finally, the best acoustic performance (NRC) is observed in natural fibers, with values ranging between 0.40 - 0.83 in sheep’s wool and cotton, due to their fibrous porosity. Synthetic and mixed fibers achieve NRC of 0.15 - 0.59, suitable for medium noise, although inferior to pure naturals. The highest NRCs are associated with low density (20 - 200 kg/m

3) and porous matrices such as mycelium, gum arabic, or natural rubber, in the absence of mineral sealing phases. Highlighted examples include cotton/polyester with natural rubber (NRC = 0.5 - 0.7) [

62], sheep’s wool (0.40 - 0.65) [

3][

37], and cotton with mycelium (NRC = 0.83) [

36]. In contrast, materials with cement or gypsum present NRC ≤ 0.5, even with fibers, due to pore sealing by the mineral matrix. Overall, acoustic absorption critically depends on open porosity and the absence of dense coatings, clearly favoring lightweight and organic composites.

In summary,

Table 1 reveals the potential of textile fibers in building insulation, where natural fibers balance thermal and acoustic insulation (λ < 0.06 W/(m·K); NRC up to 0.83) and synthetic fibers prioritize mechanical strength (compression up to 11 MPa; flexion up to 13 MPa). Hybrid and mixed fibers offer versatile applications; in general, all applications vary according to the type of matrix (biological or mineral), which influences properties and purposes, from lightness to durability, requiring optimizations to reduce inconsistencies. This view highlights the opportunities and positions these composites as sustainable construction materials for buildings.

Table 1.

Comparative properties of textile fiber-based composites.

Table 1.

Comparative properties of textile fiber-based composites.

| Type |

Textile fiber |

Other materials (Reinforcement/Aggregate/Skeleton) |

Binder/Matrix/Adhesive |

Thermal conductivity (W/(m.K)) |

Density (kg/m3) |

Compressive strength (MPa) |

Flexural strength (MPa) |

Noise Reduction Coefficient (NRC) |

Ref |

| Natural fibers |

Sheep’s wool |

Cellulose; rPET fibers; rPES fibers; hemp fibers. |

Carding-folding; PET; Co-PET/PET; chitosan; arabic gum; polylactic acid (PLA). |

0.030 - 0.060 |

N/A |

0.10 - 0.20 |

N/A |

0.40 - 0.65 |

[31,32,33,34,35,36,37] |

| Jute |

Coffee husk post-consumption; paper cups; coffee grounds |

Hydrothermal compression |

0.038 - 0.044 |

670 - 920 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

[38] |

| Flax |

Fiber glass; ash; sand; coconut fiber; jute felt; hemp felt; linen felt; cork |

Arabic natural glue; polyester; PLA; epoxy resin. |

0.029 - 1.177 |

240 - 340 |

N/A |

2.1 - 3.35 |

0.15 - 0.20 |

[39,40,41,42,43,44] |

| Cotton |

Hemp particles (hurd); coir pith; |

Mycelium; epoxy; calcium alginate; gypsum. |

0.029 - 1.173 |

72 - 730 |

0.28 - 1.57 |

0.06 - 3.35 |

0.15 - 0.83 |

[45,46,47,48,49,50] |

| Hemp |

Glass fibers; expanded polystyrene (EPS); rapeseed straw. |

Cement mortar; cement milk; corn starch; calcium sulfate hemihydrate (gypsum) |

0.041 - 0.089 |

21 - 1320 |

N/A |

2.1 - 4.1 |

N/A |

[51,52,53,54] |

| Flax and Hemp |

Wood fiber; miscanthus |

Sodium silicate; polyethylene fibers; polypropylen. |

0.040 - 0.047 |

56 - 83 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

[55] |

| Natural and synthetic fibers |

Textile Mix and hemp |

Wood; mixed fibers. |

polyester; polyolefins. |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

[56] |

| Sheep wool and polypropylene fabric |

Tetra Pak, glass fiber; Jute; |

Polypropylene spunbonded nonwoven fabric |

0.055 - 0.062 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

[56] |

| Cotton / polyester |

N/A |

Natural rubber |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

0.5 - 0.7 |

[57] |

| Wool with cotton and Polyester with nylon |

N/A |

N/A |

0.039 - 0.049 |

20 - 50 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

[58] |

| Cotton, flax and polyester |

N/A |

Portland cement |

0.830 - 1.170 |

1600 - 1900 |

N/A |

N/A |

0.2 - 0.5 |

[59] |

| Flax and textile waste |

Jute; Hemp; coconut fiber. |

Biodegradable epoxy resin; polyester. |

N/A |

1010 - 1230 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

[59] |

| Mixed textile waste fibers |

Mixed textile waste |

Residual wood sawdust; olive waste; grass cuttings; dry leaves; sugarcane bagasse; polypropylene carpet fibers; palm oil fuel ash; glass wool; cotton stalk fibre. |

Kelp brown algae; bivalve mollusc shells;synthetic fiber; unsaturated polyester resin; acrylic adhesive; white cement; paris plaster; sand; polypropylene textile; |

0.85 - 1.04 |

68 - 1850 |

1.54 - 3.11 |

0.05 - 2.62 |

0.18 - 0.46 |

[61,62,63,64,65] |

| Synthetic fibers |

Denim |

Miscanthus; rice husk; wheat husk; wood fibers; |

Corn starch; chitosan; glacial acetic acid; PBAT; PLA; sodium alginate; |

0.076 - 1.140 |

30 - 488 |

0.20 - 11 |

0.21 - 1.65 |

N/A |

[31,32,33,34,35,36,37] |

| Polyester |

Expanded polystyrene; End-of-life tyres (ELT). |

Polyvinyl acetate (PVAc); plaster (Gypsum). |

0.050 - 0.210 |

759 - 1390 |

4.4 - 8.5 |

1 - 13 |

0.15 - 0.59 |

[31,32,33,34,35,36,37] |

4.2. Comparative Properties of Glass Fiber-Based Composites

Table 2 compiles data on composites derived from glass fibers (including recycled ones), with various reinforcements such as natural fibers, tire residues, crushed aggregates, and binders like Portland cement, epoxy, and gypsum. These materials are intended for thermal, acoustic, and structural insulation applications in construction, promoting sustainability through recycling.

Thermal conductivity (λ) spans over a wide range, from 0.030 W/(m.K) (recycled tire rubber in inorganic matrix) to 0.83 W/(m.K) (FRP grids in mortar/geopolymer). This large spectrum reflects two clearly identifiable groups: those with λ < 0.07 W/(m.K), such as recycled tire rubber, Tetra Pak/textile waste with polypropylene, and bicomponent polyester fibers, positioning them in the range of commercial thermal insulators (mineral wool: λ ≈ 0.029 - 0.042 W/(m.K)). Those with intermediate or high thermal conductivity (λ > 0.12 W/(m.K)), such as snail shell/RPP, date palm fiber/UPR, and FRP in mortar, are associated with dense matrices (thermoset resins, mortars) or high fractions of mineral loading, increasing conduction heat transfer.

Density of the analyzed composite materials spans over a wide range: from 210 kg/m3 in systems based on bicomponent polyester fibers to reported values of 1582 - 1900 kg/m3 in date palm fiber composites with unsaturated polyester resin, allowing them to be classified into three functional categories according to their density. Ultralight materials (ρ < 400 kg/m3), such as bicomponent polyester fibers (210 - 400 kg/m3) and flax fiber/agglomerated cork (240 - 340 kg/m3), potentially including systems with foams or highly porous structures. Light to medium materials (400 ≤ ρ ≤ 1000 kg/m3): include polyester resin/PVC sheets (445.5 - 604.2 kg/m3), crushed mineral aggregates with glass fiber (low end: 467 – 1000 kg/m3), and composites with Tetra Pak/polypropylene, balancing lightness and cohesion for interior lining panels or semi-rigid insulation. Dense materials (ρ > 1000 kg/m3), such as gypsum reinforced with tissue paper and natural rubber latex (up to 1136.3 kg/m3), flax fiber with PLA (1240 - 1450 kg/m3), crushed aggregates (up to 1807 kg/m3), and date palm fiber composites (1582 - 1900 kg/m3), oriented toward semi-structural or lightweight structural applications, where high density contributes to rigidity and strength.

The mechanical strength of composites varies by orders of magnitude, reflecting the decisive influence of the matrix type, nature of the reinforcement, and quality of the fiber-matrix interface. Compressive strength shows the highest values in composites with reinforced mineral matrices: mortar with FRP grid (5.9 - 9.1 MPa), mortar with tire rubber (1.87 - 6.86 MPa), and cement with aggregates and glass fiber (0.92 - 8.54 MPa). These ranges approximate the ≥ 2.5 MPa required for lightweight cellular concrete blocks (EN 771-4)[

71]. In contrast, gypsum with paper/rubber shows lower strengths (0.197 - 1.980 MPa), limiting its use to non-critical applications from the mechanical viewpoint. Regarding flexural strength, the potential of natural fibers in polymeric matrices stands out: date palm fiber/UPR (14.71 - 105.71 MPa), an exceptional value comparable to conventional glass fiber composites, attributable to a high reinforcement fraction and good adhesion under controlled manufacturing conditions; snail shell/RPP (30.16 - 34.56 MPa), with high rigidity but limited ductility; and gypsum with paper/rubber (0.00 - 0.90 MPa), very low and typical of brittle materials without continuous reinforcement.

The Noise Reduction Coefficient (NRC) is reported in a limited manner in

Table 2, only in four cases, highlighting the need for more standardized data to evaluate the acoustic performance of glass fiber composites. Gypsum with tissue paper and natural rubber shows a low NRC (0.13 - 0.39), due to its dense mineral matrix that limits porosity; similarly, cork with flax and epoxy reaches only 0.15 - 0.18, due to the sealing action of resin. In contrast, brick/limestone aggregates with glass fiber and cement achieve a moderate NRC (0.23 - 0.34), thanks to their hybrid structure.

The standout case is centrifugal glass wool in gypsum, with an NRC of 0.77, preserving its open fibrous absorption in hybrids, unlike encapsulated short fibers. This last case is key: it demonstrates that the porous architecture of recycled glass fiber (as wool) can preserve its acoustic functionality even in hybrid systems, unlike short fibers or particles encapsulated in resins.

Finally, the role of recycled glass fiber in the

Table 2 composites is limited to three entries marked with ✓, highlighting its primary application as structural reinforcement rather than thermal or acoustic insulator, in contrast to its continuous fibrous variant as glass wool. For example, the FRP grid in mortar/geopolymer [

68] improves compressive strength (5.9 - 9.1 MPa) and flexural strength (2.2 - 3.1 MPa), although it raises thermal conductivity (0.234 - 0.83 W/(m.K)), compromising thermal insulation; the crushed mineral aggregates (brick/limestone) with glass fiber and white Portland cement [

70] mechanically reinforce (compression 0.92 - 8.54 MPa; flexion 0.59 - 3.06 MPa) and offer a moderate NRC (0.23 - 0.34), but lack data on λ; finally, polyester resin/PVC sheets [

79] present intermediate-high λ (0.133 - 0.190 W/(m.K)), with density (445.5 - 604.2 kg/m

3). This trend suggests that recycled fiber prioritizes durability in semi-structural uses, reserving its thermal insulating properties for unprocessed forms, inviting hybrid research to enhance its sustainable versatility.

In summary,

Table 2 evidences the versatile potential of glass fiber composites in sustainable construction, balancing thermal and acoustic insulation and reinforcement according to the matrix and reinforcements employed. This compilation positions these materials in the state of the art, promoting upcycling of waste to reduce environmental impacts. Future studies could focus on bio-mineral hybrids for integrated applications, boosting their commercial adoption.

4.3. Research Articles Employing Bio-Binders

Table 3 was developedexclusively presenting research works that used bio-binders combined with end-of-life wind turbine blades and/or textile waste. This table provides a detailed description of the materials and bio-binders studied, including properties such as thermal conductivity, density, and compressive strength. The objective of analysis is to identify the types of bio-binders used in different studies, and to evaluate integration of end-of-life wind turbine blades and/or textile waste. Analysis of the documents led to the conclusion that only solutions containing textile waste use bio-binders. Thus, no works were found in literature combining bio-binder with end-of-life wind turbine blades, thus higlighting a research need and opportunity.

Various combinations of natural and synthetic materials were observed, mainly for thermal, acoustic, and structural insulation purposes. The most used natural materials include plant fibers and textile waste, each presenting specific characteristics that promote sustainability and operational performance.

Among the plant fibers used, such as hemp, jute, coconut fibers, and bamboo particles, stood out presenting the best properties, for example, hemp and sheep wool were used in combination with polylactic acid (PLA), providing excellent thermal insulation and acoustic absorption, with thermal conductivities ranging from 0.034 to 0.045 W/(m.K) [

86]. Jute fibers and biaxial flax fibers, together with Karanja oil epoxy resins, contributed to improving the mechanical strength of composites.

While textile waste includes both natural and synthetic fibers as cotton, polyester and denim waste for production of biocomposites, these represent a meaningful option in the reuse of post-consumer materials. Cotton and polyester are bonded with natural latex, exhibiting good flexural strength and acoustic properties, while denim waste, in combination with corn starch, is used for development of acoustic panels.

However, biocomposites made from natural and synthetic materials, like basalt fibers and beech sawdust mixed with PLA, had the highest flexural strengths, reaching up to 79 MPa [

87]. Bio-binders used in the studies vary in terms of frequency of use, innovation, and performance concerning specific properties. Numerous studies have extensively used calcium alginate and PLA. Researchers used calcium alginate with cotton and viscose fibers due to its ability to withstand heat and sparks [

88]. Conversely, researchers mixed PLA with beech sawdust, basalt fibers, hemp fibers, and sheep wool waste. Chitosan comes from crustacean waste, and from literature it could be concluded that it works well when combined with miscanthus giganteus, rice husk, textile waste, and merino wool fibers, giving them good mechanical and thermal properties. Using corn starch to bond denim textile waste and hemp straw significantly enhanced the mechanical and acoustic properties of composites [

89]. Additionally, Arabic natural glue was employed with flax fiber waste, achieving low thermal conductivity of 0.029-0.325 W/(m.K) and densities from 25 to 650 kg/m

3, as characterized by modified guarded hot box, hot and cold room methods, and steady-state techniques [

90]. These bio-binders demonstrated significant improvements in the mechanical and thermal insulation properties of composites.

On the other hand, new research directions are emerging, such as the use of mycelium and other materials derived from microorganisms. Mycelium demonstrated the ability to bond bamboo particles, forming a biocomposite with thermal insulation properties and good mechanical strength. The ability of mycelium to grow and bond with different materials, forming lightweight and durable composites, represents an innovative and sustainable approach to materials manufacturing [

91].

Regarding characterization techniques, these have been widely used to evaluate the properties of composite materials. Among the most used are Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), essential for analyzing the microstructure of materials, and thermal analysis, including DSC, DTA-TG, and TGA, used to evaluate thermal stability and decomposition properties. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) was frequently used to identify functional groups and analyze the chemical composition of materials. Moreover, mechanical tests (tension, bending, and compression) were widely conducted to determine the strength of composites. Measurement of thermal conductivity (λ) is crucial for evaluating the thermal insulation performance of solutions, and water absorption analysis is of paramount importance regarding structural integrity and durability of the developed solutions. These techniques allow for understanding and quantification of physical, chemical, mechanical, thermal, and acoustic properties of composites, enabling a comprehensive assessment of their performance.

Additionally, the Noise Reduction Coefficient (NRC) is an important index for evaluating the acoustic properties of materials. NRC characterizes the effectiveness of a material in absorbing sound, essential for applications that require acoustic control.

As mentioned above, the literature did not present studies referring to combinations of materials from end-of-life wind turbine blades with bio-binders, thus indirectly highlighting the need for more research on the subject.

Summing up, bio-binders can help decrease dependence on nonrenewable resources, as they facilitate product development without the use of fossil fuels based-solutions, contributing for a sustainable development. With the variety of fiber composites, plants, and textile waste used, research reveals how environmentally friendly and technically possible solutions are searched.

5. Conclusions

This bibliometric and content analysis of 138 documents, from 2014 to 2025, reveals a maturing yet moderately growing research field (5.09% annual growing rate) in developing sustainable thermal and acountic insulation materials for construction, leveraging end-of-life wind turbine blades and textile waste. Europe, led by Italy (29 publications), France (21), and Spain (11), dominates research output (45.5% of global publications), with strong international collaborations centered in France and Italy as key network bridges. Publications emphasize materials characterization, thermal/acoustic properties, and sustainability, as evidenced by frequent keywords like “thermal insulation” (22 occurrences), “composites” (11), and “recycling” (10), disseminated primarily in sustainability-focused journals such as Journal of Cleaner Production (9 articles).

Contents analysis of textile fiber-based composites underscores their potential for circular economy applications: natural fibers (e.g., sheep’s wool, flax, cotton, hemp) presenting an thermal conductivity ranging between 0.029 - 0.089 W/(m.K) and acoustic insulation (NRC up to 0.83), attributed to porous microstructures, while synthetics (e.g., denim, polyester) allow improved mechanical strength (compression strength up to 11 MPa; flexural strength up to 13 MPa). Hybrids offer versatility but exhibit variability tied to matrix type (bio vs. mineral), with low-density options (<200 kg/m3) suiting non-structural prefabrication and denser ones (>1000 kg/m3) enabling semi-structural uses. Similarly, glass fiber composites demonstrate broad functionality, with low-λ groups (<0.07 W/(m.K), e.g., tire rubber hybrids) rivaling commercial thermal insulators, though recycled variants favoring reinforcement over insulation, highlighting trade-offs in density (210 - 1900 kg/m3) and mechanical strength (flexural up to 105.71 MPa in date palm/UPR).

Bio-binder integration is limited to textile waste solutions (e.g., PLA with hemp/sheep wool: λ = 0.034 - 0.045 W/(m.K); NRC = 0.60 - 0.65), enhancing thermal/mechanical properties via natural agents like calcium alginate, chitosan, corn starch, and mycelium, while no studies combine them with wind turbine blades — revealing a critical gap amid projected 43 million tons of annual blade waste by 2050.

Overall, these wastes enable competitive, eco-friendly thermal and acoustic insulators that reduce GHG emissions (construction’s 34% share) and align with EPBD/COP29 goals, fostering synergies across wind, textile, and construction sectors. Future research should prioritize bio-binder/wind blade hybrids, standardized testing, and life-cycle assessments to bridge gaps, accelerate upcycling, and drive commercial adoption for decarbonized buildings by 2050.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: G.V.; Methodology: G.V., A.F., V.C. and R.V.; Validation: G.V., A.F. and R.V.; Investigation: G.V., A.F., V.C. and R.V.; Resources: A.F., V.C. and R.V.; Writing - Original Draft Preparation: G.V.; Writing - Review and Editing: G.V., A.F., V.C. and R.V.; Visualization: G.V., A.F., V.C. and R.V.; Supervision: A.F., V.C. and R.V.; Project Administration: A.F., V.C. and R.V.; Funding Acquisition: A.F., V.C. and R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in whole or in part by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. (FCT,

https://ror.org/00snfqn58) under Grant UID/6438/2025 of the research unit CERIS. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC-BY public copyright license to any Author’s Accepted Manuscript (AAM) version arising from this submission. V

.: A. F. Costa acknowledges the national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project/contract UID 00481 - Centre for Mechanical Technology and Automation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DSC |

Differential scanning calorimetry |

| E |

Modulus of elasticity, MPa |

| EDS |

Energy dispersive spectroscopy |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy |

| JAC |

Obtained using the Johnson-Champoux-Allard method |

| MOR |

Modulus of rupture |

| N |

Open porosity |

| NP |

Number of publications |

| NRC |

Noise reduction coefficient |

| PET |

Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PY_start |

Year of first publication |

| SAC |

Sound absorption coefficient |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

| STL |

Sound transmission loss |

| T |

Tortuosity |

| TC |

Total citations |

| TGA |

Thermogravimetric analysis |

| TPS |

Transient plane source |

| XRD |

X-Ray diffraction analysis |

| λ |

Thermal conductivity, W/(m·K) |

| ρbulk

|

Bulk density, kg/m3

|

| ρtrue

|

True density, kg/m3

|

| σ |

Air flow resistivity, kN·s/m4

|

| FRP |

Fiber reinforced polymer |

References

- Environment Agency European Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy Use in Buildings in Europe Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-energy?activeAccordion=ecdb3bcf-bbe9-4978-b5cf-0b136399d9f8 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- United Nations Environment ProgrammeUnited Nations Environment Programme, G.A. for B. and C. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction - Beyond Foundations: Mainstreaming Sustainable Solutions to Cut Emissions from the Buildings Sector.

- European Commission Energy Performance of Buildings Directive Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-efficient-buildings/energy-performance-buildings-directive_en?prefLang=pt (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- UNFCCC, U.N.C.C. Summary of Global Climate Action at COP 29 Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/644497.

- Mazor, M.H.; Mutton, J.D.; Russell, D.A.M.; Keoleian, G.A. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction From Rigid Thermal Insulation Use in Buildings. J Ind Ecol 2011, 15, 284–299. [CrossRef]

- Pargana, N.; Pinheiro, M.D.; Silvestre, J.D.; de Brito, J. Comparative Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Thermal Insulation Materials of Buildings. Energy Build 2014, 82, 466–481. [CrossRef]

- Pianklang, S.; Muntongkaw, S.; Tangboriboon, N. Modified Thermal- and Sound-Absorption Properties of Plaster Sandwich Panels with Natural Rubber-Latex Compounds for Building Construction. J Appl Polym Sci 2022, 139. [CrossRef]

- Rubino, C.; Bonet Aracil, M.; Liuzzi, S.; Stefanizzi, P.; Martellotta, F. Wool Waste Used as Sustainable Nonwoven for Building Applications. J Clean Prod 2021, 278, 123905. [CrossRef]

- Sadrolodabaee, P.; Hosseini, S.M.A.; Claramunt, J.; Ardanuy, M.; Haurie, L.; Lacasta, A.M.; Fuente, A. de la Experimental Characterization of Comfort Performance Parameters and Multi-Criteria Sustainability Assessment of Recycled Textile-Reinforced Cement Facade Cladding. J Clean Prod 2022, 356, 131900. [CrossRef]

- Meddour, M.; Si Salem, A.; Ait Taleb, S. Bending Behavior of New Composited Sandwich Panels with GFRP Waste Based-Core and PVC Facesheets: Experimental Design, Modeling and Optimization. Constr Build Mater 2024, 426, 136117. [CrossRef]

- Suthatho, A.; Rattanawongkun, P.; Tawichai, N.; Tanpichai, S.; Boonmahitthisud, A.; Soykeabkaew, N. Low-Density All-Cellulose Composites Made from Cotton Textile Waste with Promising Thermal Insulation and Acoustic Absorption Properties. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2024, 6, 390–397. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Thilagavathi, G.; Rajkhowa, R. Composite Panels Utilizing Microdust and Coir Pith for Eco-Friendly Construction Solutions. The Journal of The Textile Institute 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Schulte, M.; Lewandowski, I.; Pude, R.; Wagner, M. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Bio-Based Insulation Materials: Environmental and Economic Performances. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 979–998. [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Krishnaraj, V.; Shankar, K.; Senthilkumar, M.; Zitoune, R. Experimental Investigation on Impact, Sound, and Vibration Response of Natural-Based Composite Sandwich Made of Flax and Agglomerated Cork. J Compos Mater 2019, 54, 669–680. [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, A.H.; Candan, Z.; Demirkir, C.; Hamouda, T. Thermal Insulation Properties of Hybrid Textile Reinforced Biocomposites from Food Packaging Waste. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2016, 47, 1024–1037. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K. Recycling Wind Turbine Blades. Renewable Energy Focus 2009, 9, 70–73. [CrossRef]

- Deeney, P.; Nagle, A.J.; Gough, F.; Lemmertz, H.; Delaney, E.L.; McKinley, J.M.; Graham, C.; Leahy, P.G.; Dunphy, N.P.; Mullally, G. End-of-Life Alternatives for Wind Turbine Blades: Sustainability Indices Based on the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Resour Conserv Recycl 2021, 171, 105642. [CrossRef]

- Sorte, S.; Martins, N.; Oliveira, M.S.A.; Vela, G.L.; Relvas, C. Unlocking the Potential of Wind Turbine Blade Recycling: Assessing Techniques and Metrics for Sustainability. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16. [CrossRef]

- Sorte, S.; Figueiredo, A.; Vela, G.; Oliveira, M.S.A.; Vicente, R.; Relvas, C.; Martins, N. Evaluating the Feasibility of Shredded Wind Turbine Blades for Sustainable Building Components. J Clean Prod 2024, 434, 139867. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Memon, H.A.; Wang, Y.; Marriam, I.; Tebyetekerwa, M. Circular Economy and Sustainability of the Clothing and Textile Industry. Materials Circular Economy 2021, 3, 12. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Tan, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhu, G.; Yin, R.; Tao, X.; Tian, X. Industrialization of Open- and Closed-Loop Waste Textile Recycling towards Sustainability: A Review. J Clean Prod 2024, 436, 140676. [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J Informetr 2017, 11, 959–975. [CrossRef]

- Souley Agbodjan, Y.; Wang, J.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Z.; Luo, Z. Bibliometric Analysis of Zero Energy Building Research, Challenges and Solutions. Solar Energy 2022, 244, 414–433. [CrossRef]

- Bottcher, P. Textile Waste Materials in New End-Uses. 1984.

- DIN 4108-2:2013-02, Thermal Protection and Energy Economy in Buildings - Part 2: Minimum Requirements to Thermal Insulation 2013.

- ASHRAE Handbook—Fundamentals. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. In; 2021.

- Lomelí-Ramírez, M.G.; Anda, R.R.; Satyanarayana, K.G.; Bolzon de Muniz, G.I.; Iwakiri, S. Comparative Study of the Characteristics of Green and Brown Coconut Fibers for the Development of Green Composites. Bioresources 2018, 13. [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, N.; Ramamurthy, K. Structure and Properties of Aerated Concrete: A Review. Cem Concr Compos 2000, 22, 321–329. [CrossRef]

- Muthuraj, R.; Lacoste, C.; Lacroix, P.; Bergeret, A. Sustainable Thermal Insulation Biocomposites from Rice Husk, Wheat Husk, Wood Fibers and Textile Waste Fibers: Elaboration and Performances Evaluation. Ind Crops Prod 2019, 135, 238–245. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Junior, J.C.; Triki, E.; Doutres, O.; Demarquette, N.R.; Hof, L.A. Recyclable Polyester Textile Waste-Based Composites for Building Applications in a Circular Economy Framework. J Clean Prod 2025, 515, 145759. [CrossRef]

- Stapulionienė, R.; Vaitkus, S.; Vėjelis, S. Development and Research of Thermal-Acoustical Insulating Materials Based on Natural Fibres and Polylactide Binder. In Proceedings of the Materials Science Forum; Trans Tech Publications Ltd., 2017; Vol. 908 MSF, pp. 123–128.

- Rubino, C.; Angeles, M.; Aracil, B.; Liuzzi, S.; Martellotta, F. Preliminary Investigation on the Acoustic Properties of Absorbers Made of Recycled Textile Fibers;

- Grebenisan, E.; Ionescu, B.A.; Toader, T.P.; Calatan, G.; Bulacu, C. Assesment of the bio-eco-innovative properties of sheep wool based heat insulation materials.; December 20 2021; pp. 107–116.

- Rubino, C.; Bonet Aracil, M.; Gisbert-Payá, J.; Liuzzi, S.; Stefanizzi, P.; Zamorano Cantó, M.; Martellotta, F. Composite Eco-Friendly Sound Absorbing Materials Made of Recycled Textile Waste and Biopolymers. Materials 2019, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rubino, C.; Bonet Aracil, M.; Liuzzi, S.; Stefanizzi, P.; Martellotta, F. Wool Waste Used as Sustainable Nonwoven for Building Applications. J Clean Prod 2021, 278, 123905. [CrossRef]

- Hegyi, A.; Vermeșan, H.; Lăzărescu, A.-V.; Petcu, C.; Bulacu, C. Thermal Insulation Mattresses Based on Textile Waste and Recycled Plastic Waste Fibres, Integrating Natural Fibres of Vegetable or Animal Origin. Materials 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Korjenic, A.; Teichmann, F. Building with Renewable Materials. De Gruyter Brill 2024, 72, 679–686. [CrossRef]

- Echeverria, C.A.; Ozkan, J.; Pahlevani, F.; Willcox, M.; Sahajwalla, V. Effect of Hydrothermal Hot-Compression Method on the Antimicrobial Performance of Green Building Materials from Heterogeneous Cellulose Wastes. J Clean Prod 2021, 280, 124377. [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Krishnaraj, V.; kumar, M.S.; Zitoune, R. Sound and Vibration Damping Properties of Flax Fiber Reinforced Composites. Procedia Eng 2014, 97, 573–581. [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Krishnaraj, V.; Shankar, K.; Senthilkumar, M.; Zitoune, R. Experimental Investigation on Impact, Sound, and Vibration Response of Natural-Based Composite Sandwich Made of Flax and Agglomerated Cork. J Compos Mater 2020, 54, 669–680. [CrossRef]

- Sivalingam, P.; Vijayan, K.; Mouleeswaran, S.; Vellingiri, V.; Mayilswamy, S. On the Tensile and Compressive Behavior of a Sandwich Panel Made of Flax Fiber and Agglomerated Cork. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications 2022, 236, 180–189. [CrossRef]

- Bąk, A.; Mikuła, J.; Oliinyk, I.; Łach, M. Basic Research on Layered Geopolymer Composites with Insulating Materials of Natural Origin. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 12576. [CrossRef]

- Dannemann, M.; Siwek, S.; Modler, N.; Wagenführ, A.; Tietze, J. Damping Behavior of Thermoplastic Organic Sheets with Continuous Natural Fiber-Reinforcement. Vibration 2021, 4, 529–536. [CrossRef]

- Messiry, M. El; El-Tarfawy, S.Y.; Ayman, Y.; Deeb, R. El Development of High-Performance Thermal Insulation Panels from Flax Fiber Waste for Building Insulation. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2025, 55, 15280837251338160. [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Zhang, X. Fully Bio-Based Fire-Safety Composite from Cotton/Viscose Wastes and Alginate Fiber as Furniture Materials. Waste Management 2023, 168, 137–145. [CrossRef]

- Kavun, Y.; Eken, M. Investigation of Thermal, Acoustic, Mechanical, and Radiation Shielding Performance of Waste and Natural Fibers. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2024, 214, 111539. [CrossRef]

- Suthatho, A.; Rattanawongkun, P.; Tawichai, N.; Tanpichai, S.; Boonmahitthisud, A.; Soykeabkaew, N. Low-Density All-Cellulose Composites Made from Cotton Textile Waste with Promising Thermal Insulation and Acoustic Absorption Properties. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2024, 6, 390–397. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Thilagavathi, G.; Rajkhowa, R. Composite Panels Utilizing Microdust and Coir Pith for Eco-Friendly Construction Solutions. The Journal of The Textile Institute 2025, 116, 175–182. [CrossRef]

- Taylor Ethan and Neupane, S. and M.C. Mycelium as a Sustainable, Low-Carbon Material for Building Panels. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering Annual Conference 2023, Volume 6; Desjardins Serge and J Poitras, G. and A.M.S. and S.-C.X., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; pp. 333–346.

- Binici, H.; Eken, M.; Dolaz, M.; Aksogan, O.; Kara, M. An Environmentally Friendly Thermal Insulation Material from Sunflower Stalk, Textile Waste and Stubble Fibres. Constr Build Mater 2014, 51, 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Iucolano, F.; Boccarusso, L.; Langella, A. Hemp as Eco-Friendly Substitute of Glass Fibres for Gypsum Reinforcement: Impact and Flexural Behaviour. Compos B Eng 2019, 175, 107073. [CrossRef]

- Kakitis, A.; Berzins, R.; Berzins, U. Cutting energy assessment of hemp straw; 2016;

- Neuberger, P.; Kic, P. Thermal Conductivity of Natural Materials Used for Thermal Insulation. In Proceedings of the Engineering for Rural Development; Latvia University of Agriculture, 2017; Vol. 16, pp. 420–424.

- Liu, K.; Perilli, S.; Chulkov, A.O.; Yao, Y.; Omar, M.; Vavilov, V.; Liu, Y.; Sfarra, S. Defining the Thermal Features of Sub-Surface Reinforcing Fibres in Non-Polluting Thermo–Acoustic Insulating Panels: A Numerical–Thermographic–Segmentation Approach. Infrastructures (Basel) 2021, 6. [CrossRef]

- Schulte, M.; Lewandowski, I.; Pude, R.; Wagner, M. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Bio-Based Insulation Materials: Environmental and Economic Performances. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 979–998. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Bhat, G. Environmentally-Friendly Thermal and Acoustic Insulation Materials from Recycled Textiles. J Environ Manage 2019, 251, 109536. [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, A.H.; Candan, Z.; Demirkir, C.; Hamouda, T. Thermal Insulation Properties of Hybrid Textile Reinforced Biocomposites from Food Packaging Waste. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2018, 47, 1024–1037. [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, D.G.K.; Weerasinghe, D.U.; Thebuwanage, L.M.; Bandara, U.A.A.N. An Environmentally Friendly Sound Insulation Material from Post-Industrial Textile Waste and Natural Rubber. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 33, 101606. [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Kim, Y.U.; Kim, S. Revolutionizing Thermal Management: Utilizing Textile Waste for Transformative Pipe Insulation as an Alternative to Conventional Materials. Waste Management 2025, 205, 114975. [CrossRef]

- Fontoba-Ferrándiz, J.; Juliá-Sanchis, E.; Amorós, J.E.C.; Alcaraz, J.S.; Borrell, J.M.G.; García, F.P. Panels of Eco-Friendly Materials for Architectural Acoustics. J Compos Mater 2020, 54, 3743–3753. [CrossRef]

- Echeverria, C.A.; Pahlevani, F.; Handoko, W.; Jiang, C.; Doolan, C.; Sahajwalla, V. Engineered Hybrid Fibre Reinforced Composites for Sound Absorption Building Applications. Resour Conserv Recycl 2019, 143, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.M.; Machado de Oliveira, E.; de Oliveira, C.M.; Dal-Bó, A.G.; Peterson, M. Study of the Incorporation of Fabric Shavings from the Clothing Industry in Coating Mortars. J Clean Prod 2021, 279, 123730. [CrossRef]

- Jamshaid, H.; Shah, A.; Shoaib, M.; Mishra, R.K. Recycled-Textile-Waste-Based Sustainable Bricks: A Mechanical, Thermal, and Qualitative Life Cycle Overview. Sustainability 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Valtere, M.; Bezrucko, T.; Liberova, V.; Blumberga, D. Recycling of Mixed Post-Consumer Textiles: Opportunities for Sustainable Product Development. Environmental and Climate Technologies 2025, 29, 323–343. [CrossRef]

- Rubino, C.; Liuzzi, S.; Martellotta, F. Exploring the potential of recycled textile panels to improve sound insulation in buildings. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Forum Acusticum; European Acoustics Association, EAA, 2023.

- Lacoste, C.; El Hage, R.; Bergeret, A.; Corn, S.; Lacroix, P. Sodium Alginate Adhesives as Binders in Wood Fibers/Textile Waste Fibers Biocomposites for Building Insulation. Carbohydr Polym 2018, 184, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Muthuraj, R.; Lacoste, C.; Lacroix, P.; Bergeret, A. Sustainable Thermal Insulation Biocomposites from Rice Husk, Wheat Husk, Wood Fibers and Textile Waste Fibers: Elaboration and Performances Evaluation. Ind Crops Prod 2019, 135, 238–245. [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, Y.; El Hage, P.; Dimitrova Mihajlova, J.; Bergeret, A.; Lacroix, P.; El Hage, R. Influence of Agricultural Fibers Size on Mechanical and Insulating Properties of Innovative Chitosan-Based Insulators. Constr Build Mater 2021, 287, 123071. [CrossRef]

- Juciene, M.; Dobilaitė, V.; Albrektas, D.; Bliūdžius, R. Investigation and Evaluation of the Performance of Interior Finishing Panels Made from Denim Textile Waste. Textile Research Journal 2022, 92, 4666–4677. [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza-Benzal, A.; Ferrández, D.; Atanes-Sánchez, E.; Morón, C. New Lightened Plaster Material with Dissolved Recycled Expanded Polystyrene and End-of-Life Tyres Fibres for Building Prefabricated Industry. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2023, 18, e02178. [CrossRef]

- 71. EN 771-4:2011 + A1:2015 Specification for Masonry Units – Part 4: Autoclaved Aerated Concrete Masonry Units; 2015;

- Nazari, S.; Ivanova, T.A.; Mishra, R.K.; Muller, M. A Review Focused on 3D Hybrid Composites from Glass and Natural Fibers Used for Acoustic and Thermal Insulation. Journal of Composites Science 2025, 9. [CrossRef]

- Longo, F.; Cascardi, A.; Lassandro, P.; Aiello, M.A. A Novel Composite Reinforced Mortar for the Structural and Energy Retrofitting of Masonry Panels. Key Eng Mater 2022, 916, 377–384. [CrossRef]

- Longo, F.; Cascardi, A.; Lassandro, P.; Sannino, A.; Aiello, M.A. Mechanical and Thermal Characterization of FRCM-Matrices. Key Eng Mater 2019, 817, 189–194. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, T.S. Acoustic Analyses of Mortars Prepared with Recycled Aggregates. Applied Acoustics 2023, 205, 109273. [CrossRef]

- K S, L.; D, S.M.; H L, Y.; I S, S.; Nikam, H.; K L, C.K.R. Evaluation of Mechanical, Acoustic and Vibration Characteristics of Calamus Rotang Based Hybrid Natural Fiber Composites. Results in Engineering 2025, 25, 104475. [CrossRef]

- Oladele, I.O.; Falana, O.S.; Okoro, C.J.; Onuh, L.N.; Akinbamiyorin, I.; Akinrinade, S.O.; Adegun, M.H.; Odemona, E.T. Sustainable Composites Reinforced with Glass Fiber and Bio-Derived Calcium Carbonate in Recycled Polypropylene. Hybrid Advances 2025, 8, 100357. [CrossRef]

- Pianklang, S.; Muntongkaw, S.; Tangboriboon, N. Modified Thermal- and Sound-Absorption Properties of Plaster Sandwich Panels with Natural Rubber-Latex Compounds for Building Construction. J Appl Polym Sci 2022, 139, 52068. [CrossRef]

- Cerkez, I.; Kocer, H.B.; Broughton, R.M. Airlaid Nonwoven Panels for Use as Structural Thermal Insulation. The Journal of The Textile Institute 2018, 109, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Osanga, N.; Shokry, H.; Hassan, M.A.; Khair-Eldeen, W. Investigation of Physical and Mechanical Behavior of Hybrid Date Palm-Glass Fiber-Reinforced BMC Composites for Sustainable Green Construction Applications. Fibers and Polymers 2025, 26, 4419–4437. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.G.; Han, M.Y.; Lee, Y.N. Fabrication of FRP Spacers of Insulating Glass for Energy-Saving Eco-Friendly Home. In Proceedings of the Eco-Materials Processing and Design XV; Trans Tech Publications Ltd., October 2015; Vol. 804, pp. 19–22.

- Li, X. Architectural Acoustic Application of Medical Space Roof Wall System Based on Prefabricated Interior Decoration Technology. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2019, 371, 22039. [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Krishnaraj, V.; Shankar, K.; Senthilkumar, M.; Zitoune, R. Experimental Investigation on Impact, Sound, and Vibration Response of Natural-Based Composite Sandwich Made of Flax and Agglomerated Cork. J Compos Mater 2020, 54, 669–680. [CrossRef]

- Meddour, M.; Si Salem, A.; Ait Taleb, S. Bending Behavior of New Composited Sandwich Panels with GFRP Waste Based-Core and PVC Facesheets: Experimental Design, Modeling and Optimization. Constr Build Mater 2024, 426, 136117. [CrossRef]

- Ji, F.; Peng, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Feng, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, S. Environmental-Friendly and Rapid Production of Rigid Glass Micro/Nano Fiber Porous Materials for Noise Absorption, Thermal Insulation and Fire Protection. Ceram Int 2025, 51, 45725–45737. [CrossRef]

- Stapulionienė, R.; Vaitkus, S.; Vėjelis, S. Development and Research of Thermal-Acoustical Insulating Materials Based on Natural Fibres and Polylactide Binder. Materials Science Forum 2017, 908 MSF, 123–128. [CrossRef]

- Aykanat, O.; Ermeydan, M.A. Production of Basalt/Wood Fiber Reinforced Polylactic Acid Hybrid Biocomposites and Investigation of Performance Features Including Insulation Properties. Polym Compos 2022, 43, 3519–3530. [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Zhang, X. Fully Bio-Based Fire-Safety Composite from Cotton/Viscose Wastes and Alginate Fiber as Furniture Materials. Waste Management 2023, 168, 137–145. [CrossRef]

- Juciene, M.; Dobilaitė, V.; Albrektas, D.; Bliūdžius, R. Investigation and Evaluation of the Performance of Interior Finishing Panels Made from Denim Textile Waste. Textile Research Journal 2022, 92, 4666–4677. [CrossRef]

- Messiry, M. El; El-Tarfawy, S.Y.; Ayman, Y.; Deeb, R. El Development of High-Performance Thermal Insulation Panels from Flax Fiber Waste for Building Insulation. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2025, 55, 15280837251338160. [CrossRef]

- Carcassi, O.B.; Minotti, P.; Habert, G.; Paoletti, I.; Claude, S.; Pittau, F. Carbon Footprint Assessment of a Novel Bio-Based Composite for Building Insulation. Sustainability 2022, 14.

- Dissanayake, D.G.K.; Weerasinghe, D.U.; Thebuwanage, L.M.; Bandara, U.A.A.N. An Environmentally Friendly Sound Insulation Material from Post-Industrial Textile Waste and Natural Rubber. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 33, 101606. [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, Y.; El Hage, P.; Dimitrova Mihajlova, J.; Bergeret, A.; Lacroix, P.; El Hage, R. Influence of Agricultural Fibers Size on Mechanical and Insulating Properties of Innovative Chitosan-Based Insulators. Constr Build Mater 2021, 287, 123071. [CrossRef]

- Fontoba-Ferrándiz, J.; Juliá-Sanchis, E.; Crespo Amorós, J.E.; Segura Alcaraz, J.; Gadea Borrell, J.M.; Parres García, F. Panels of Eco-Friendly Materials for Architectural Acoustics. J Compos Mater 2020, 54, 3743–3753. [CrossRef]

- Rubino, C.; Bonet Aracil, M.; Gisbert-Payá, J.; Liuzzi, S.; Stefanizzi, P.; Zamorano Cantó, M.; Martellotta, F. Composite Eco-Friendly Sound Absorbing Materials Made of Recycled Textile Waste and Biopolymers. Materials 2019, 12.

- Rubino, C.; Bonet Aracil, M.A.; Liuzzi, S.; Martellotta, F. Preliminary Investigation on the Acoustic Properties of Absorbers Made of Recycled Textile Fibers. Proceedings of the International Congress on Acoustics 2019, 2019-Septe, 3450–3457. [CrossRef]

- Lacoste, C.; El Hage, R.; Bergeret, A.; Corn, S.; Lacroix, P. Sodium Alginate Adhesives as Binders in Wood Fibers/Textile Waste Fibers Biocomposites for Building Insulation. Carbohydr Polym 2018, 184, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Neuberger, P.; Kic, P. Thermal Conductivity of Natural Materials Used for Thermal Insulation. Engineering for Rural Development 2017, 16, 420–424. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).