1. Introduction

To consider the connection between the mathematical equations of a physical theory and the world, Bas van Fraassen introduced the concept of the problem of coordination [

1]. In the previous work [

2], this question was discussed for temperature, and in this paper, this is extended to entropy in classical thermodynamics (below just thermodynamics). In the case of entropy, the problem of coordination is expressed in two related questions:

For simplicity, the discussion is limited to pure substances, but even in this case, things become significantly more complex than for temperature. The main difference is that entropy belongs to the formalism of classical thermodynamics, and the solution of the problem of coordination for entropy is impossible without simultaneously solving the problem of coordination for other thermodynamic properties, such as heat capacity, internal energy, enthalpy, and Gibbs energy. In the paper it is assumed that the physical quantities pressure, volume, and temperature have already been defined, and that the thermal equation of state is known f(

V,

p,

T) = 0 (see [

2]). It is also assumed that the mass of the substance remains constant, and this is implicitly reflected in all the equations in this paper.

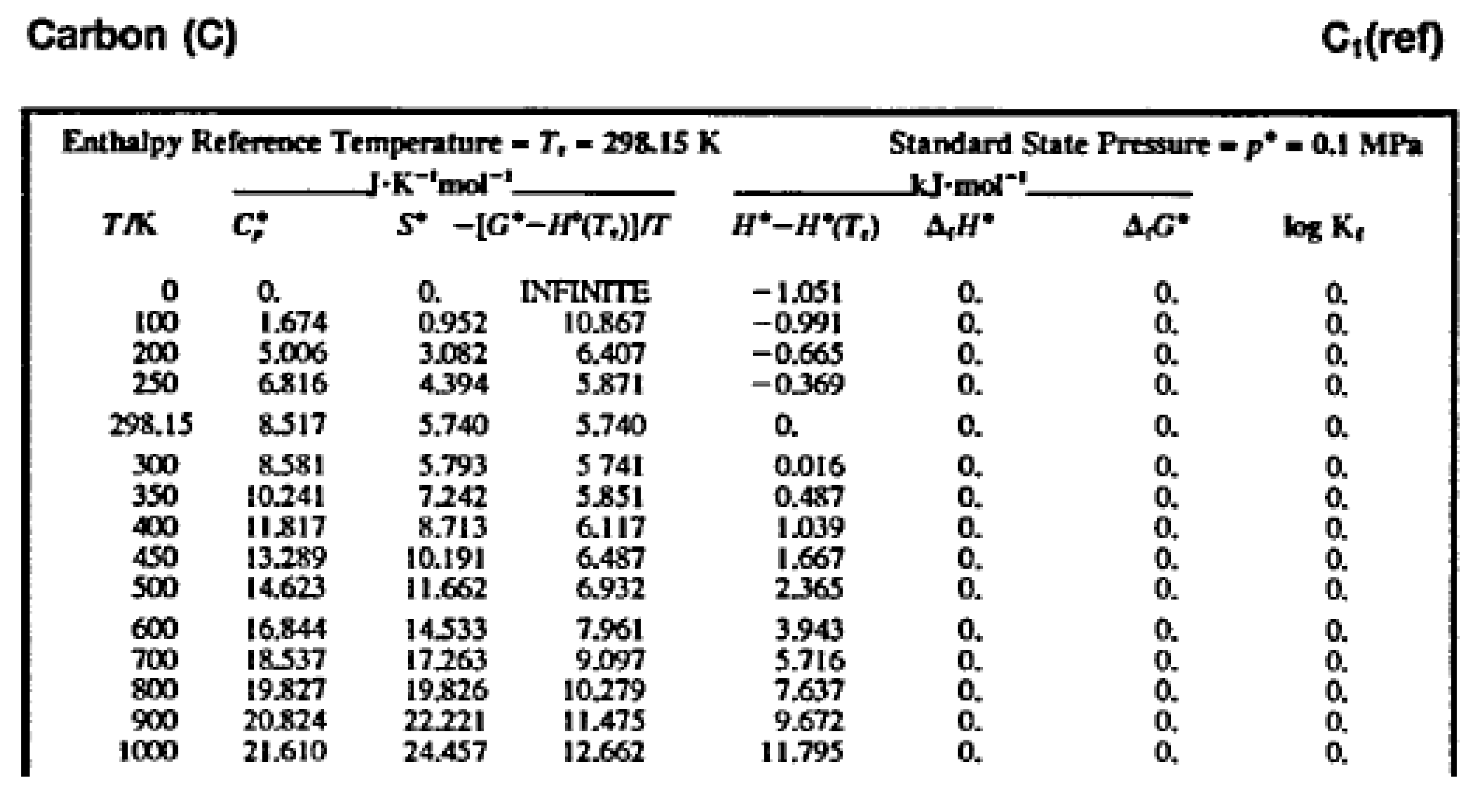

Figure 1 shows a part of the table of thermodynamic properties of graphite from '

NIST-JANAF Thermochemical Tables' [

3]. Numerical values of thermodynamic properties, including entropy, are obtained from the experimental results; thus, understanding of the process to produce this table leads to the solution of the problem of coordination. The theory of thermodynamics says what entropy and other thermodynamic properties are and makes it possible to create conceptual models of ideal experiments to be used to perform measurements necessary to make a table of thermodynamic properties. As always, a choice of the measurement scale is needed - certain conventions about the dimension of physical quantities in the table.

We start by conceptual models that correspond to the first and second laws of thermodynamics; the definitions of two physical quantities, internal energy and entropy. This models then are transformed into a conceptual model of an ideal experiment in calorimetry, and in parallel, heat capacities at constant volume and at constant pressure are defined. Real calorimetric experiments are carried out at constant pressure, so for convenience a new thermodynamic property, enthalpy, is introduced. The table above shows enthalpies of the substance, since internal energy is almost not used in practical calculations. Mathematical transformations of the first and second laws open the way to obtain from experimental results thermodynamic properties in the table, including entropy. Gibbs energy is also considered, since it allows us to propose an optimal way for simultaneous assessment of miscellaneous thermodynamic experiments. In conclusion, we discuss what entropy is.

2. Internal energy and entropy as physical properties

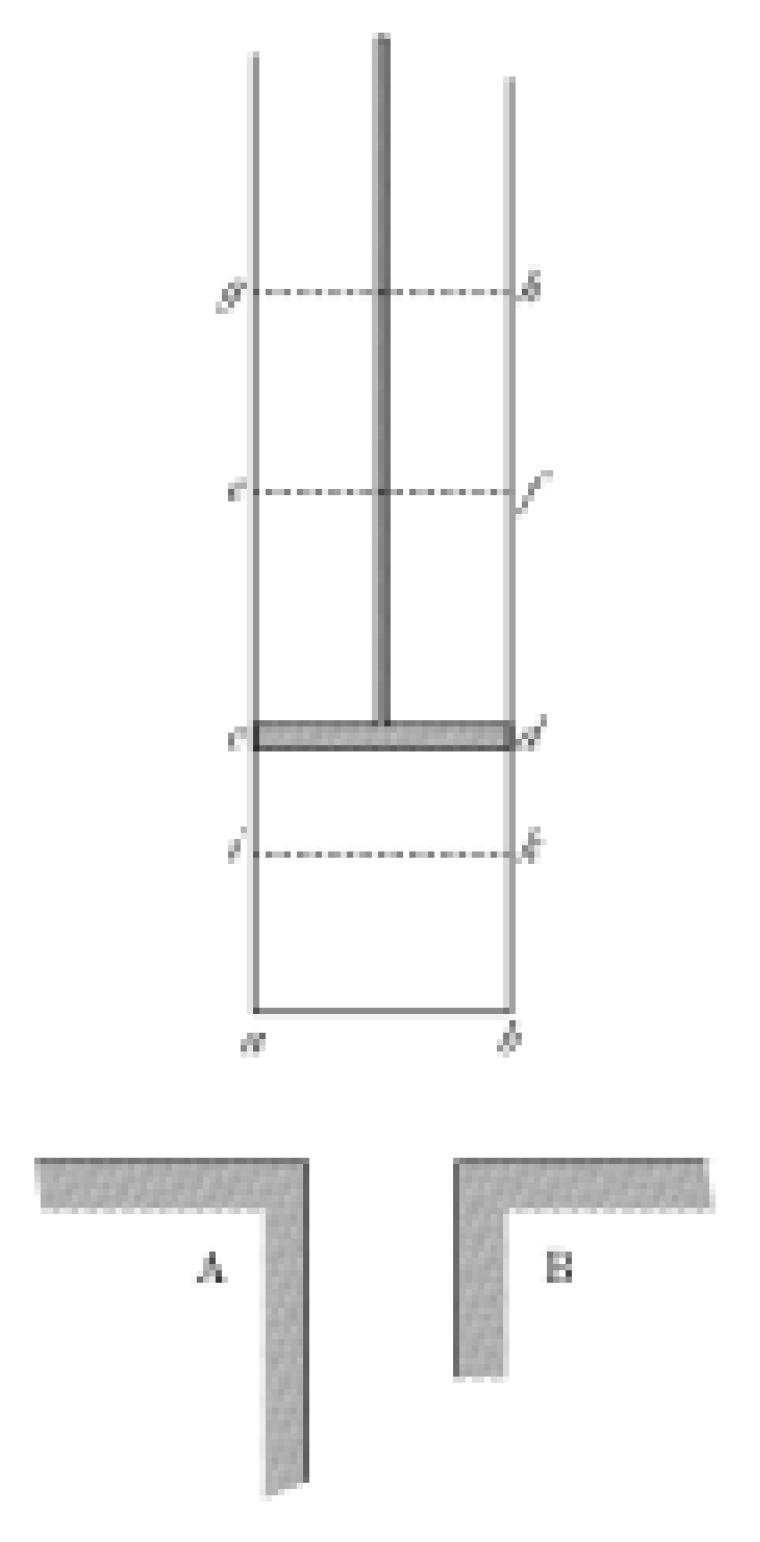

I use a drawing from Sadi Carnot's book [

4] shown in

Figure 2 to discuss the conceptual model. The substance under study is inside of a cylinder with a piston. It is assumed that the cylinder and the piston have ideal thermal properties, and they do not deform. Therefore, their properties do not affect the interaction of the substance with the external environment. The piston sets the external pressure, and the other two bodies A and B at the bottom of the drawing are used for heat exchange, that is, for setting the temperature. When the cylinder does not touch any of these bodies, heat exchange is excluded, and when the cylinder is connected to one of them, heat transfer occurs.

Thermodynamics, like continuum mechanics, uses properties of substances, which must be determined for each substance in appropriate experiments. The theory of thermodynamics defines existing thermodynamic properties and proposes experiments to find them. However, there are various relationships between thermodynamic properties, and this imposes requirements on assessment of miscellaneous experiments - it is necessary to precisely fulfill all mathematical relations between different properties.

The laws of thermodynamics refer to the change in the thermodynamic state of the substance under the piston. The state is characterized by temperature and pressure in the absence of gradients - temperature and pressure are uniform within the entire volume of the substance. A change in the state of the substance is caused by a change in external conditions, for example, a jump in external pressure or the connection of the substance to one of the heat sources. After that, a spontaneous process begins, which ends with a new thermodynamic state with different uniform temperature and pressure.

A thermodynamic process is the idealization of processes in continuum mechanics, and therefore in thermodynamics real spontaneous processes are called irreversible; during such a process there are temperature and pressure gradients in the substance. The idealization in thermodynamics, on the other hand, deals with the concept of the reversible process, in which there is no time and in which the substance always remains in a uniform state without gradients of temperature and pressure.

Changes in the state in an irreversible or reversible process are accompanied by mechanical work and heat transfer. Work and heat do not belong to the state of the substance, since they are not functions of state. Their differentials are called inexact, since they do not correspond to a function; integrals from heat and work differentials depend on the integration path, and the closed-contour integral is not zero.

The thermodynamic properties of a substance are functions of state, and their change does not depend on the path of the process, nor on whether the process was irreversible or reversible. This is the key to understand experiments in thermodynamics. Conceptual models using reversible processes are required to define some thermodynamic quantities, but they cannot be directly used to form ideal experiments, since all real measurements are done by irreversible processes. The property of being a state function ultimately allows us to connect conceptual models based on reversible processes with conceptual models of an ideal experiment based on irreversible processes.

The first law of thermodynamics relates the change in internal energy (U) with heat (Q) and mechanical work (

pexd

V, p

ex is external pressure,

V is volume) (see, e.g., [

5,

6]):

In the general case, mechanical work uses the external pressure on the piston, since in the irreversible process, a pressure field is formed inside the substance. Thus, the equation above allows us to correctly calculate the work of the irreversible process. The equation is also the definition of internal energy, that is, it formally says what internal energy is.

Entropy (

S) is related to heat according to the second law of thermodynamics (see, e.g., [

5,

6]):

| Reversible process |

|

| Irreversible process |

|

These equations define entropy and in this sense the equations say what entropy is; this is discussed in the last section.

The first and second laws introduce functions of state, internal energy and entropy from heat and work, which are not themselves functions of state. This means that there are new equations of state analogous to the thermal equation of state p(T, V) - the equation of state for the internal energy U(T, V) and the entropy S(T, V). The problem of coordination for internal energy and entropy comes down to ways to construct these equations based on experiments. More precisely, the theory specifies which experiments are suitable to determine thermodynamic properties.

As already mentioned, the reversible process is idealization. This was required to consider the ideal Carnot cycle and thus to obtain the equations of the first and second laws above in the differential form. The concept of the reversible process is quite non-trivial, and discussions to this end continue up to now - see, for example, the correct treatment in 2018 [

7,

8] and misinterpretation in 2016 [

9] (it has been discussed in [

10]). In any case, the definition of entropy cannot be used to construct a conceptual model of an ideal experiment, since the reversible process cannot be carried out. This, however, does not mean that entropy cannot be related to experiments, but some mathematical transformations would be required.

Substituting the inequality from the second law to the first law leads to the fundamental inequality:

Temperature and pressure set by external conditions are used in the inequality. Thus, the inequality includes, among other things, the state of a substance with temperature and pressure gradients. Under given external conditions, the inequality is the criterion of the spontaneous process and the criterion of the final equilibrium state. In this paper, the inequality is not used, since it is just assumed that the establishment of the final state of the irreversible process belongs to real experiments. I return to the inequality in the second law at the end of the paper to discuss what entropy is.

Substituting the equality from the second law to the first law gives the fundamental equation:

Now the change of the state of the substance is characterized only by state functions. Formally, the fundamental equation refers to the state with uniform temperature and pressure without gradients. Integrals from the fundamental equation could in principle be classified as reversible processes, but now, the change of the state function obtained in this way is the same for all processes, including irreversible ones.

A simple example - let us assume that we know the volume magnitude in two states. Then the change in volume is the difference of these values, regardless of how the process occurred. The same logic applies to all thermodynamic properties — internal energy, entropy, enthalpy, and Gibbs energy; this is what the concept of the state function means.

For example, entropy in both parts of the second law (equality and inequality) has the same meaning: it is a physical property of the substance, that is, it is a function of state. This is the difference between entropy and heat on the right side, since heat is not a property of a substance. Thus, the sign of inequality in the second part refers not to entropy, but to heat. The change in entropy from state 1 to state 2 is the same for reversible and irreversible processes, provided that the initial and final states in both processes are the same. The transition to the fundamental equation opens the way to find entropy from experimentally measurable quantities.

3. Calorimetry

Calorimetric experiments play a key role in this paper, and this section provides a simplified introduction to calorimetry. The concept of heat has been developed during mixing of hot and cold substances. Georg Richmann at the St. Petersburg Academy published a rule for mixing hot and cold quantities of water in 1750:

where m

1 and m

2 denote the masses of water to be mixed, and

t1 and

t2 denote initial temperatures. The concept of heat appeared later in the works of Joseph Black. It was found that Richmann's rule does not work when mixing hot water and cold mercury. To obtain correct results, it was necessary to introduce the specific heat capacity and modify the rule as follows:

In the case of mixing water, specific heat capacity is the same, and Richmann's rule is obtained, in the case of mixing mercury and water, specific heat capacities are different and without them it is impossible to explain the observed results.

To use this equation, the unit of heat was introduced. Note that at that time heat was assumed to be a property of a substance – this is corrected in the next section. One calorie was defined as the heat required to heat one gram of water by one degree Celsius. Thus, the specific heat capacity of water was accepted to be equal to 1 cal/g. The accepted heat capacity of water made it possible to determine the heat capacities of other bodies and this way a scale for the heat magnitude was introduced.

In parallel, experiments were carried out on the mixing of hot water and ice at 0 °C. The final temperature differed from that according to Richmann's rule, that is, from the results of mixing hot water and cold water at 0 °C. Hence it was necessary to include the latent heat of melting ice, that is, heat required to melt ice at constant temperature of 0 °C. On this basis, Antoine Lavoisier and Pierre-Simon Laplace proposed the ice calorimeter in 1780, which was actively used to measure the amount of heat in the first half of the 19th century.

An ideal measuring device corresponding to the ice calorimeter is ice at the melting point of 0 °C, inside which the process takes place to cool the substance from the initial temperature to 0 °C. The amount of heat is equal to the specific latent heat of ice multiplied by the mass of water formed. It was also possible to study combustion reactions in the vessel inside the ice. In this case, the heat of combustion is obtained from the mass of the formed water. There are many technical difficulties, and the accuracy of the ice calorimeter is rather low; so eventually it fell out of use. However, understanding calorimetry at the level of the ice calorimeter already gives a good idea of calorimetry.

The ideas behind modern calorimeters are close to mixing calorimetry discussed above. The difference lies in various corrections for heat exchange with the environment, which cannot be eliminated completely, considering the dependence of heat capacity on temperature and, of course, in the transition to energy units (1 cal = 4.184 J).

4. Caloric equation of state and heat capacity at constant volume

Heat happens not to be a function of state, and therefore it is necessary to connect the results of calorimetric experiments to changes of the function of state. In this section, this is done in the case of internal energy, and at the same time the construction of function U(T, V) is considered. After heat was denied the status of the property of a substance, this function became known as the caloric equation of state.

At constant volume, there is no mechanical work, and therefore the measured amount of heat at constant volume (

QV) is equal to the change in internal energy:

The second equation gives the relationship between the result of the experiment in calorimetry at constant volume and the change in the internal energy of the substance. This equation holds true for the irreversible process in calorimetry, that is, it applies to a real experiment. For example, in Carnot's drawing, one could imagine the connection of the cylinder with a substance in a certain state with a fixed position of the piston (constant volume) to a heat source. The amount of heat transferred during establishment a new equilibrium state is equal to the change in the internal energy of the substance. In this case, the conceptual model turns into a model of an ideal experiment, which serves as the basis to conduct real experiments. It explains what corrections are necessary due to differences in the real experiment from the ideal conditions.

From above follows the definition of heat capacity at constant volume as the derivative of internal energy:

It is important that heat capacity at constant volume is a function of state, that is, a property of the substance. As usual, the derivative can be considered constant only in a small temperature range, in general, the heat capacity at constant volume remains a function of temperature and volume.

now the differential for the caloric equation of state is written:

the first derivative is heat capacity at constant volume (connection with calorimetry), but special efforts are required to determine the dependence of internal energy on volume at constant temperature. in the history of 19th-century physics, gay-lussac and joule's experiments with gases led to the conclusion that this derivative for gases is zero. Later, however, it turned out that this conclusion was valid only for the ideal gas equation of state, and for real gases the situation was more complicated (Joule-Thomson experiments).

At the same time, the second law of thermodynamics, that is, the introduction of state function

S(

T,

V), not only does not require new experiments, but even makes it possible to express the second derivative of internal energy by means of the thermal equation of state. Formally

, function

S(

T,

V) leads to two new derivatives:

However, substituting this equation into the fundamental equation of thermodynamics gives a connection between these derivatives and the derivatives of internal energy in temperature and volume:

In classical thermodynamics, the Maxwell relation is proved (see, for example, [

6]), which expresses the entropy derivative by volume in terms of the thermal equation of state:

Taken together, this leads to the final expressions:

Thus, to determine internal energy and entropy of a pure substance, it is enough to have information on heat capacity at constant volume and the thermal equation of state. Calorimetric experiments and the study of the thermal equation of state (relative pressure coefficient) lead simultaneously to the construction of functions of internal energy and entropy. Two equations give a joint solution to the problem of coordination for internal energy and entropy, since all the physical quantities on the right-hand side are now related to experiments. It is worth noting, that these equations are obtained when entropy and internal energy are considered together, that is, the problem of coordination of these quantities cannot be separated from each other.

The equations also demonstrate that the construction of internal energy and entropy follows from the same experiments. Of course, these equations cannot be regarded as definitions of internal energy and entropy. The definitions are the first and second laws, and these equations are the consequences that lead to a connection of required functions U(T, V) and S(T, V) with experiments. Integration gives results that correspond to reversible and irreversible processes, since the integral expression contains only state functions. In the case of entropy, this is the answer to the question of how the second law allows us to construct the entropy function from experimental results based on real, irreversible processes.

5. Enthalpy and heat capacity at constant pressure

Real calorimetric experiments are carried out at constant pressure. The discussion in the previous section is interesting from a theoretical point of view, but in practice a new independent variable, pressure, is required. The Legendre transform below allows us to switch pressure and volume:

This is the formal definition of enthalpy. Unlike internal energy and entropy, which are introduced by the laws of thermodynamics, enthalpy is the equivalent transformation that is introduced for convenience.

New thermodynamic properties in classical thermodynamics introduced 'for convenience' cause a certain cognitive dissonance, but this is another good reason to discuss the relationship between mathematics in a physical theory and the world. For example, let us ask whether enthalpy exists. The formal answer is that if a substance has internal energy, pressure, and volume, then it also has enthalpy as its property. The expression 'for convenience' means that in mathematics there is an equivalent transformation that produces a new function that is more convenient to use in practice. This, of course, raises difficult questions for metaphysicians who are concerned with the structure of the world — whether enthalpy really exists, but this does not cause problems in practice.

Taking the differential from the definition of enthalpy and using the expression for internal energy leads to the connection of enthalpy and heat

as well as to the new fundamental equation of thermodynamics

The change of variables occurred, in the differential equations for enthalpy, pressure is the independent variable, and volume has become the derivative. Thus, the amount of heat in a calorimetric experiment at constant pressure is equal to the change in the enthalpy of the substance:

Sometimes, it is said that enthalpy differs from internal energy by mechanical work, but it is true only for processes under constant pressure. In any case, enthalpy turns out to be a state function that is convenient to use in respect to calorimetry and which is related to heat capacity at constant pressure:

In principle, it is possible to use the results of calorimetry at constant pressure to calculate the change in internal energy, since there is a relationship between heat capacities at constant volume and constant pressure. However, this would require the use of the thermal equation of state, and the use of enthalpy makes it possible to separate the results from calorimetry from the thermal equation of state. Moreover, many calculations are done with pressure and temperature as independent variables, and in this case, it is more convenient to use enthalpy. Therefore, in tables of thermodynamic properties enthalpy rather than internal energy is given. If required, internal energy is estimated as U = H - pV.

There are similar derivations for functions

H(

T,

p) and

S(

T,

p), and I give only the final expressions that are used to construct thermodynamic tables:

6. Thermodynamic properties of pure substances

The equations for differentials of entropy

dS(

T,

p) and enthalpy

dH(

T,

p) emphasize the possibility to separate calorimetry from the study of the thermal equation of state. This is employed in thermodynamic tables, where the properties of substances are given as functions of the temperature in the standard state at the standard pressure

H(

T,

p°) and

S(

T,

p°), where

p° according to the latest IUPAC recommendations, is equal to one bar. The standard state of solids and liquids corresponds to the real state of these substances at standard pressure, while the standard state of gases is more complicated – it corresponds to the idealized state (see, e.g., [

6]).

Thus, the term with

dp falls out and only the integral with respect to temperature remains:

The difference between entropy and enthalpy above is related to the third law of thermodynamics, according to which the entropy of all substances at absolute zero is the same, so we can use the convention that this entropy is equal to zero:

S°(

0 K) = 0. Thus, absolute entropy can be obtained from experimental heat capacities, while for enthalpy (also for internal energy) only a change can be estimated. This leads to the need for additional experiments to determine the enthalpies of the formation (see, e.g., [

6]).

In thermodynamics, an important role is played by the Gibbs energy, which is the double Legendre transformation:

As in the case of enthalpy, the definition of the Gibbs energy is purely mathematical, the Gibbs energy in thermodynamics allows us to work more conveniently with practical problems.

The Gibbs energy of a system is used as the equilibrium criterion at constant temperature and pressure. The use of temperature and pressure as controlled external conditions is well suited to many experiments, and therefore the Gibbs energy is an important part of thermodynamic tables. Another important property of the Gibbs energy is that it is the characteristic function. This means that from function

G(

T,

p) in the case of pure substances it is possible to find all other thermodynamic properties by taking derivatives, for example

This is employed in the simultaneous assessment of miscellaneous experiments. Only calorimetry and the thermal equation of state were considered above, but there are other experiments that are related to the thermodynamic properties. Experimental results contain measurement errors, both reproducibility errors and systematic errors. Therefore, the most optimal procedure for processing all available experimental results is as follows. Unknown parameters from all equations of state are collected in the Gibbs energy for consistency; this way all thermodynamic relationships are fulfilled. Then all the primary miscellaneous experimental results are expressed by means of these unknown parameters. This way produces an optimal solution in the case of simultaneous assessment of miscellaneous experiments. A paper with the search for unknown parameters in the Gibbs energy of YBa

2Cu

3O

6+z [

11] gives a good example.

In modern thermodynamic databases, only the expression of the Gibbs energy is stored in the computer representation, and all other thermodynamic properties are derived from this function. In this regard, it is useful to return to other possibilities. For example, the functions U(S, V) and H(S, p) are also characteristic. From this point of view, representations of the thermodynamic properties of a substance as functions U(S, V), H(S, p), or G(T, p) are mathematically equivalent: for any function, derivatives give all other thermodynamic properties.

The difference lies in the independent variables - solving problems in thermodynamics requires thermodynamic properties at given temperature and pressure. In the case of the Gibbs energy, the calculations follow directly, and in the case of internal energy and enthalpy, first is required to solve an internal mathematical problem to find the necessary values of the independent variables that correspond to the given temperature and pressure. As a result, the use of the Gibbs energy in practice is related to convenient independent variables that are well suited to solving practical problems.

7. What is entropy?

The second law of thermodynamics contains two parts, and therefore there are two steps in the discussion of what entropy is. The first step is associated with entropy as a physical property of a substance; the entropy change is independent from the path and the same for reversible and irreversible processes. This step has been done in this paper. We have considered the connection between mathematical equations of thermodynamics and the experimental measurements and thus the process to obtain numerical values of entropy in thermodynamic tables.

Let me list the differences between the entropy function S(T, p) and the thermal equation of state V(T, p). First, integration is necessary to obtain the entropy function; in this sense, entropy, like internal energy, enthalpy, and the Gibbs energy, can be called the integral property. Second, a conceptual model associated with the definition of entropy cannot be used directly to plan necessary measurements and it is necessary to transform it to other conceptual models using the formalism of thermodynamics. Finally, the entropy function is tightly connected with other thermodynamic properties.

The second step in this discussion is related to the second part of the second law, the Clausius inequality, but the first step is a prerequisite for considering the second step. In the Clausius inequality, entropy of the thermodynamics system is employed, and thus, a relationship is required between entropy of a substance and entropy of the system. The system consists of substances but in the general case of the Clausius inequality, it is necessary to consider non-equilibrium states.

The tragicomedy of thermodynamics (Truesdell's expression [

12], but in a different sense) consists in the fact that in textbooks of thermodynamics in one chapter the Clausius inequality and examples are given, and in another chapter, it is stated that in thermodynamics it is possible only to consider equilibrium states. This question was discussed in the paper by G. F. Voronin [

13] with an example of the textbook [

14]; this textbook is reasonably good but there are indeed contradictory statements in different places.

I take the example of the isolated system in which the Clausius inequality is reduced to the principle of increasing entropy, and this is often used as another answer to the question of what entropy is:

The subscripts U and V indicate that internal energy and volume of the isolated system remain constant. Let us suppose that in the isolated system the state of global equilibrium is found by maximizing the entropy. The question would be then whether such a statement makes sense if thermodynamics does not allow to consider the entropy of non-equilibrium states.

Thermodynamics was developed in parallel to continuum mechanics, which contain time in the explicit form. The equations of continuum mechanics are asymmetric in time, they predict the establishment of an equilibrium state in the isolated system even without the entropy in the explicit form. On the other hand, thermodynamics does not contain time in the explicit form, since time disappeared during the development of the ideal Carnot cycle with reversible processes.

Clifford Truesdell called the tragicomedy of thermodynamics [

12] lack of integration of thermodynamics and continuum mechanics. His ideal was to create rational thermodynamics (a variant of non-equilibrium thermodynamics) [

15], in which the Clausius inequality belongs to non-equilibrium thermodynamics, and thus is excluded from classical thermodynamics [

16]. Such an approach in principle could work, but rational thermodynamics proposed by Truesdell failed, and the development of non-equilibrium thermodynamics still continues [

17]. This shows that the 19th century decision to create a separate formalism of thermodynamics was after all correct.

Truesdell's critique of thermodynamics received an unexpected development in papers [

18,

19], in which, however, not only the Clausius inequality but also non-equilibrium thermodynamics in general was rejected. This has been discussed in [

20] and below there are the main points.

It is possible to consider thermodynamic properties, including entropy, for a non-equilibrium state by using a distinction between local and global equilibrium. The system in question is divided into subsystems, each of which is in a state of local equilibrium, and this allows us to use thermodynamic properties. At the same time, subsystems can exchange energy with each other, and therefore there is no global equilibrium in the whole system. The entropy of the system is found as the sum of entropies of all subsystems, and after all entropy remains as a physical property. If necessary, it is possible to include temperature and pressure gradients when dividing the system into infinitely large number of infinitesimal subsystems.

Thus, thermodynamics can work with non-equilibrium states of continuum mechanics, and the Clausius inequality without time is compatible with the equations of continuum mechanics, which contain time in the explicit form. The Clausius inequality reflects the asymmetry of the equations of continuum mechanics in time, the arrow of time being transferred from continuum mechanics to thermodynamics (see discussion in [

20]).

Such an approach gives another answer to what entropy is. The entropy of the isolated system is the criterion for the spontaneous process and the criterion for global equilibrium (entropy reaches the maximum value). However, thermodynamics does not contain time, so nothing can be said about the rate of transition from the entropy value alone. To determine the path and rate, the equations of continuum mechanics are required.

It is important not to forget that the increase in entropy for the spontaneous process refers only to the isolated system. In the case of other external conditions, other criteria are required, which are obtained from the Clausius inequality by transformations. For example, with constant external pressure and temperature, the Gibbs energy of the system tends to minimum, and in this case, this is the criterion for the spontaneous process. Entropy is a component of the Gibbs energy, but we cannot talk about the increase in entropy in such a case.

In conclusion, I note once again the tight connection of all thermodynamic quantities in the formalism of thermodynamics. Any attempt to relate entropy to information or ignorance will automatically relate all thermodynamic quantities to information or ignorance.

References

- van Fraassen, Bas C. Scientific Representation: Paradoxes of Perspective, 2008. Part II: Windows, Engines, and Measurement.

- Rudnyi, E. The Problem of Coordination: Temperature as a Physical Quantity, 2025, preprint.

- NIST-JANAF Thermochemical Tables, Fourth Edition, Monograph No. 9, Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 1998. Available at: https://janaf.nist.gov/.

- Carnot, S. Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire and on Machines Fitted to Develop that Power, 1897 (in French in 1824).

- Poincaré, H. Termodynamique, 1908, first published in 1892. I have read Russian translation, 2005.

- Atkins P., de Paula J. Atkins' Physical Chemistry, 2002.

- Leff H. S., Mungan C. E. Isothermal heating: purist and utilitarian views. European Journal of Physics 39, no. 4 (2018): 045103.

- Leff H., S. Reversible and irreversible heat engine and refrigerator cycles. American Journal of Physics 86, no. 5 (2018): 344-353.

- Norton J., D. The impossible process: Thermodynamic reversibility. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in Hist. and Philosophy of Modern Physics 55 (2016): 43-61.

- Rudnyi, E. Reversible Processes in Classical Thermodynamics, 2025, preprint.

- Rudnyi E. B., Kuzmenko V. V., Voronin G. V. Simultaneous assessment of the YBa2Cu3O6+z thermodynamics under the linear error model. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data, 1998, v. 27, N 5, p. 855-888.

- Truesdell, C. The tragicomical history of thermodynamics, 1822–1854. 1980.

- Voronin G., F. , Notes on the Quality of Textbooks on Thermodynamics (in Russian), Vestnik Mosk. Univ. Khimiya, 1997, vol. 38, No. 2, p. 138-144. English Translation is in Moscow University Chemistry Bulletin.

- P. Bazarov, Thermodynamics, 1964.

- Truesdell, C. Rational Thermodynamics. 1969.

- Truesdell C. A., Bharatha S. The concepts and logic of classical thermodynamics as a theory of heat engines: rigorously constructed upon the foundation laid by S. Carnot and F. Reech, 1977.

- Müller I., Weiss W. Thermodynamics of irreversible processes—past and present. The European Physical Journal H 37, no. 2 (2012): 139-236.

- Uffink, J. Bluff your way in the second law of thermodynamics. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 32, no. 3 (2001): 305-394.

- Brown H. R., Uffink J. The origins of time-asymmetry in thermodynamics: The minus first law. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 32, no. 4 (2001): 525-538.

- Rudnyi, E. Clausius Inequality in Philosophy and History of Physics, 2025, preprint.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).