Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

06 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

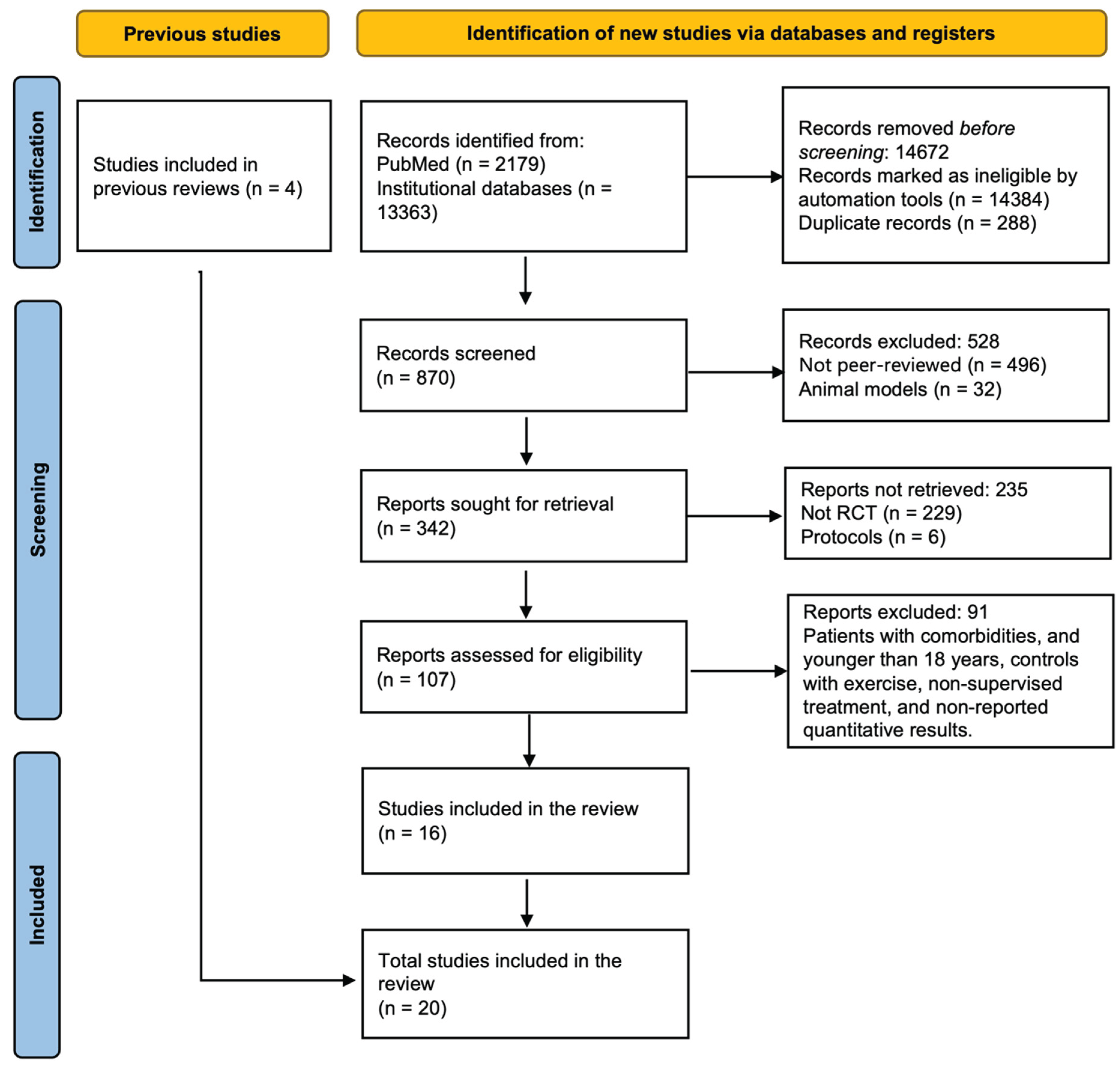

2.1. Search Results

2.2. Characteristics of Participants Included in Trials

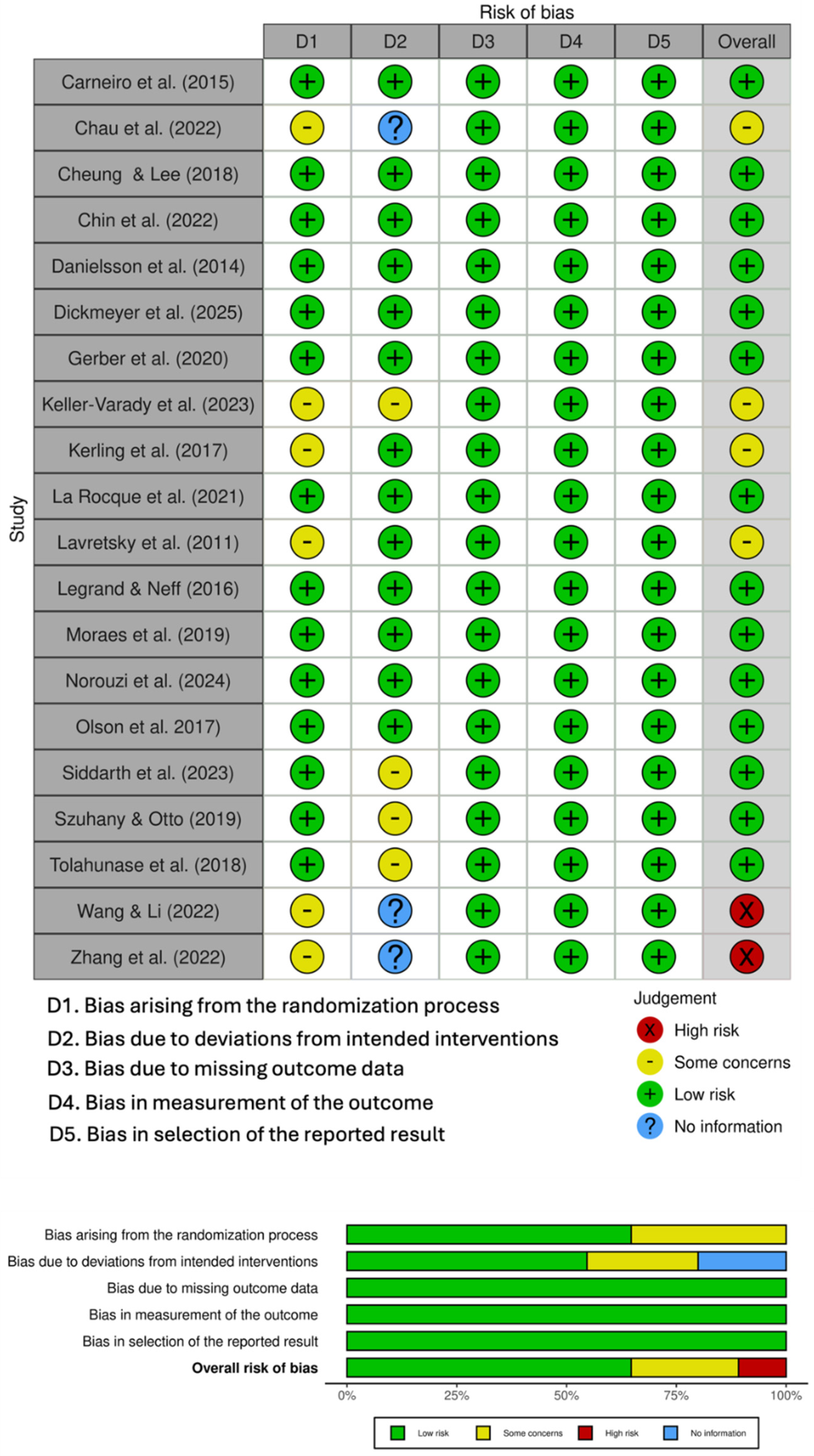

2.3. Risk of Bias

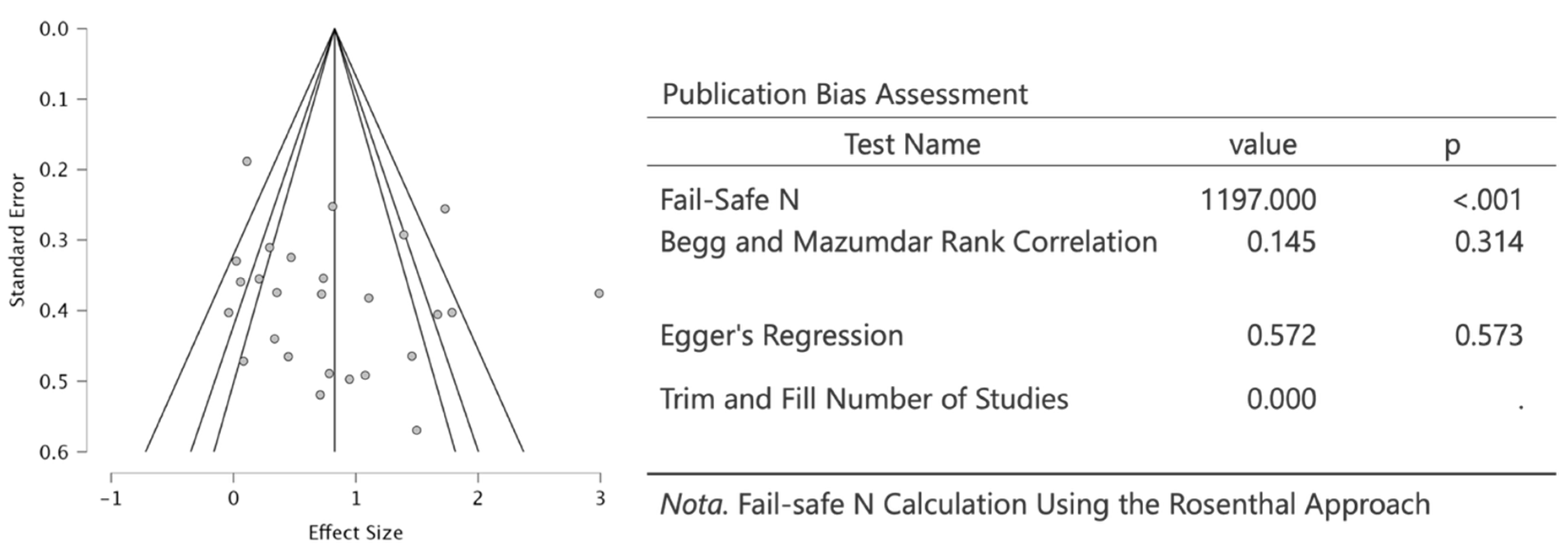

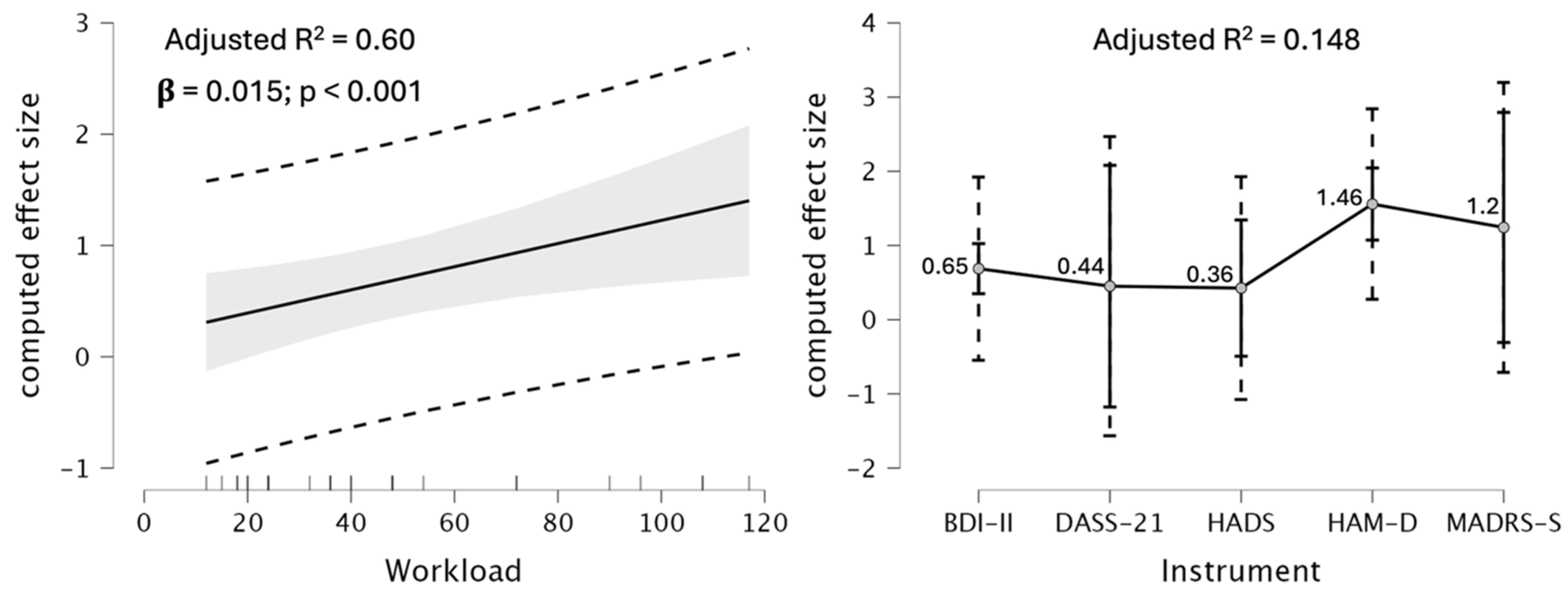

2.4. Meta-Regression

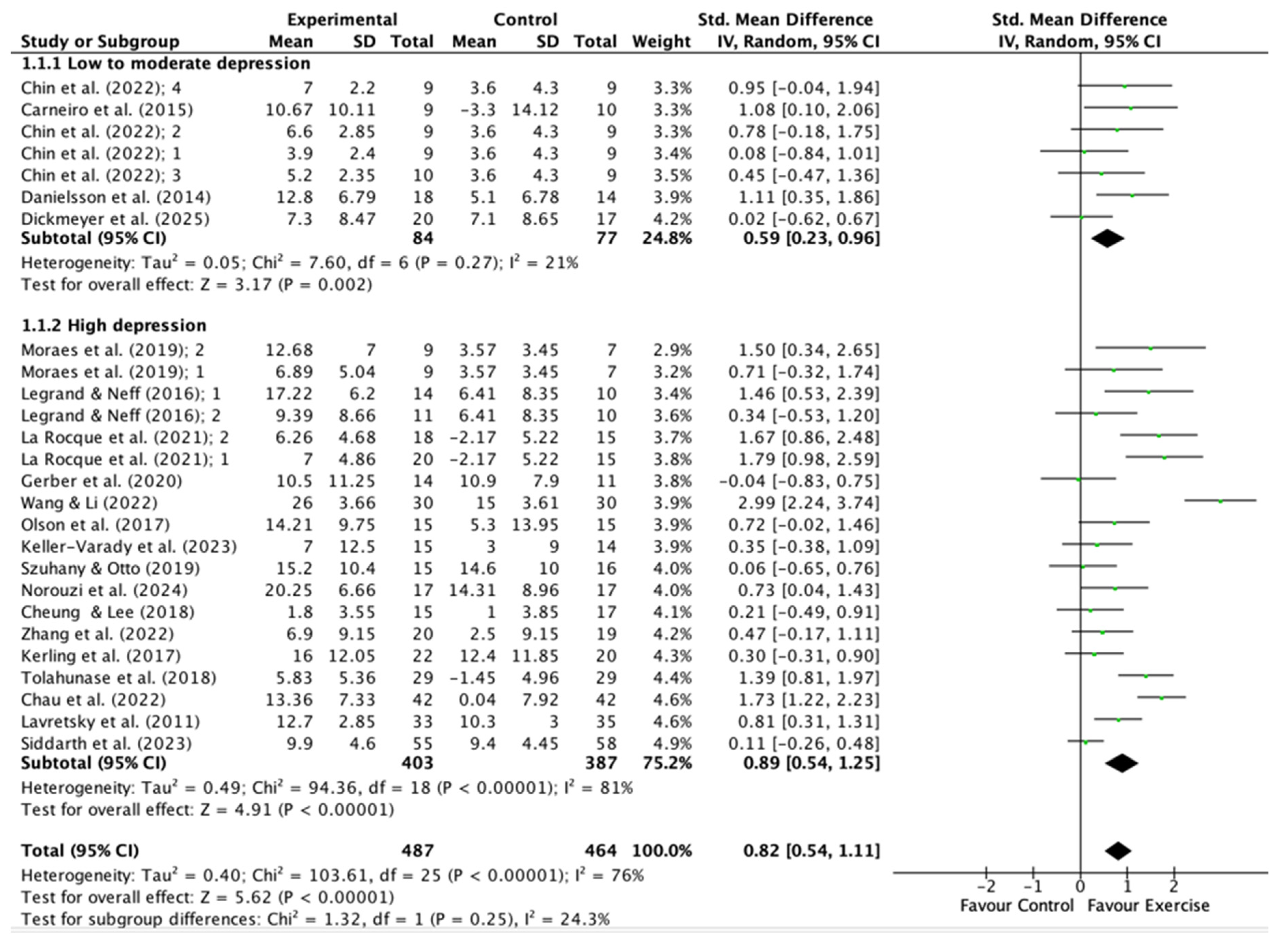

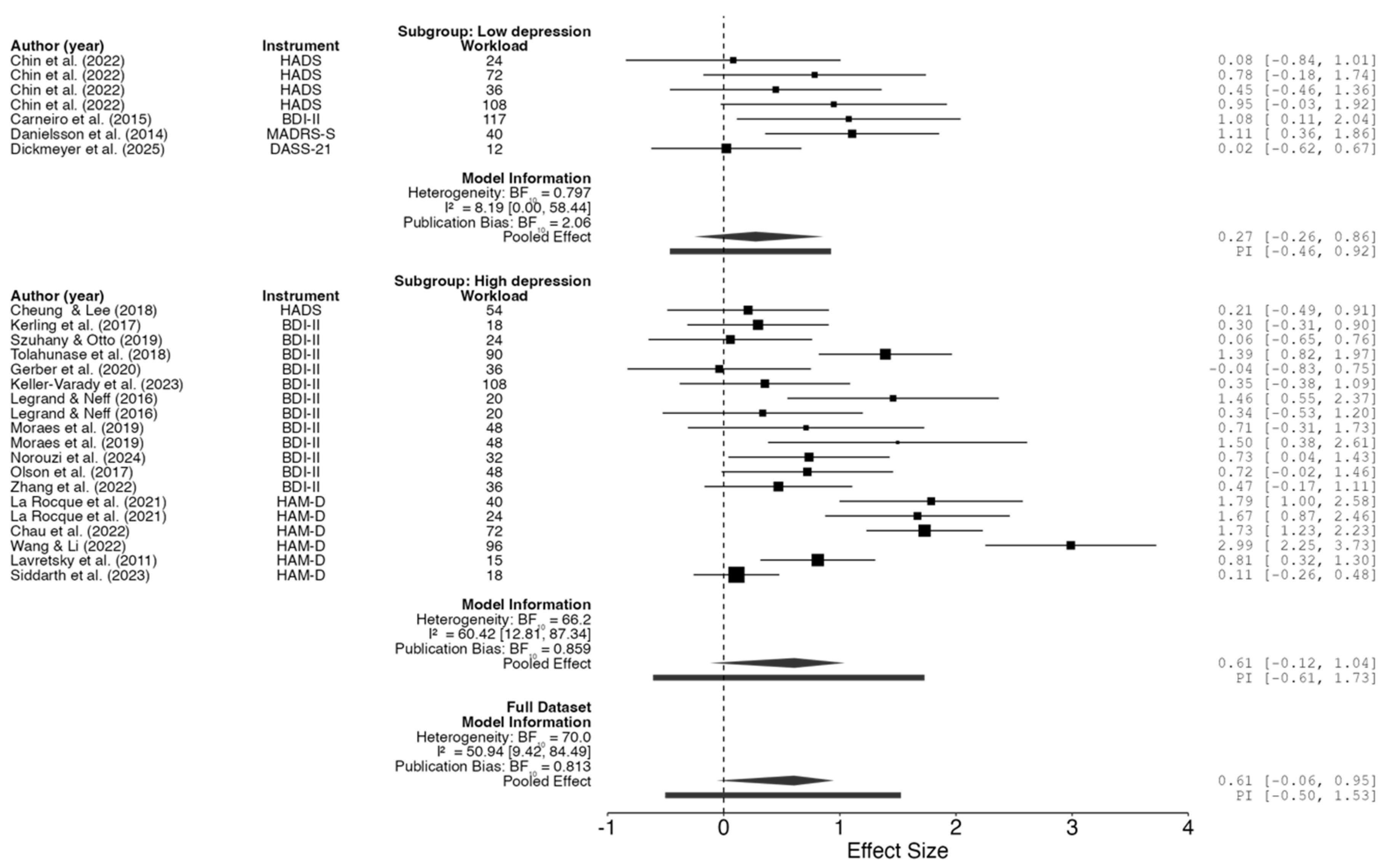

2.5. Meta-Analysis

3. Discussion

- Type of Exercise: Aerobic exercise (e.g., walking, jogging, cycling) and resistance training are the most extensively studied modalities, with both demonstrating large effect sizes [48,64]. In contrast, yoga and mind-body exercises show moderate effects, especially in older adults and individuals with comorbidities [48,49].

- Intensity: The antidepressant effects of exercise are proportional to the intensity prescribed, with moderate to vigorous exercise yielding the most significant benefits [48,49,64]. However, even light physical activity confers clinically meaningful effects, especially in previously inactive individuals [48].

- Duration and Frequency: Interventions lasting 6–12 weeks, with sessions of 30–60 minutes and performed 3–4 times per week, are associated with optimal outcomes [18,64,64]. Short interventions may also produce large effects, possibly attributable to greater participant adherence to the programs and the novelty of the activities; however, sustained engagement is necessary for long-term benefits [48,49].

- Participant Characteristics: Age, sex, baseline depression severity, and comorbidities may also influence the response to exercise; however, the evidence remains inconclusive. Certain studies indicate that women might derive greater benefits from strength training, whereas older adults tend to respond favorably to yoga and walking [44,49,53].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Registration

4.2. Search Strategy

4.3. Eligibility Criteria

4.4. Study Selection

4.5. Data Extraction

4.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Depressive Disorder (Depression). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Rong, J.; Wang, X.; Cheng, P.; Li, D.; Zhao, D. Global, Regional and National Burden of Depressive Disorders and Attributable Risk Factors, from 1990 to 2021: Results from the 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2025, 227, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Major Depression. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Malgaroli, M.; Calderon, A.; Bonanno, G.A. Networks of Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 85, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, A.M.; Brister, T.S.; Duckworth, K.; Foxworth, P.; Fulwider, T.; Suthoff, E.D.; Werneburg, B.; Aleksanderek, I.; Reinhart, M.L. Impact of Major Depressive Disorder on Comorbidities: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2022, 83, 43390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Pabst, A.; Luppa, M. Risk Factors and Protective Factors of Depression in Older People 65+. A Systematic Review. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0251326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, V.; Calati, R.; Serretti, A. Socio-Demographic and Clinical Predictors of Non-Response/Non-Remission in Treatment Resistant Depressed Patients: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 240, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, B.M.; Siqueira, C.C.; Vieira, R.M.; Moreno, R.A.; Soeiro-de-Souza, M.G. Physical Activity as an Adjuvant Therapy for Depression and Influence on Peripheral Inflammatory Markers: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2022, 22, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.; Beck, J.; Brand, S.; Cody, R.; Donath, L.; Eckert, A.; Faude, O.; Fischer, X.; Hatzinger, M.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; et al. The Impact of Lifestyle Physical Activity Counselling in IN-PATients with Major Depressive Disorders on Physical Activity, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, Depression, and Cardiovascular Health Risk Markers: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2019, 20, N.PAG-N.PAG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, F.D.; Neff, E.M. Efficacy of Exercise as an Adjunct Treatment for Clinically Depressed Inpatients during the Initial Stages of Antidepressant Pharmacotherapy: An Open Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccolo, J.T.; Louie, M.E.; SantaBarbara, N.J.; Webster, C.T.; Whitworth, J.W.; Nosrat, S.; Chrastek, M.; Dunsiger, S.I.; Carey, M.P.; Busch, A.M. Resistance Training for Black Men with Depressive Symptoms: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess Acceptability, Feasibility, and Preliminary Efficacy. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.; Imboden, C.; Beck, J.; Brand, S.; Colledge, F.; Eckert, A.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Pühse, U.; Hatzinger, M. Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Cortisol Stress Reactivity in Response to the Trier Social Stress Test in Inpatients with Major Depressive Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, H.; Anheyer, D.; Lauche, R.; Dobos, G. A Systematic Review of Yoga for Major Depressive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 213, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Song, J.; He, Y.; Li, Z.; Deng, H.; Huang, Z.; Xie, X.; Wong, N.M.L.; Tao, J.; Lee, T.M.C.; et al. Effect of Tai Chi on Young Adults with Subthreshold Depression via a Stress–Reward Complex: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Sports Med. - Open 2023, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Babyak, M.A.; Murali Doraiswamy, P.; Watkins, L.; Hoffman, B.M.; Barbour, K.A.; Herman, S.; Edward Craighead, W.; Brosse, A.L.; Waugh, R.; et al. Exercise and Pharmacotherapy in the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. Psychosom. Med. 2007, 69, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniele de Araújo Silva, J.; Cândido Mendes Maranhão, D.; Machado Ferreira Tenório de Oliveira, L.; Luiz Torres Pirauá, A. Comparison between the Effects of Virtual Supervision and Minimal Supervision in a 12-Week Home-Based Physical Exercise Program on Mental Health and Quality of Life of Older Adults: Secondary Analysis from a Randomized Clinical Trial. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2023, 23, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Liang, Z.; Qui, F.; Yu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X. Optimal Exercise Modality and Dose to Improve Depressive Symptoms in Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Model-Based Network Meta-Analysis of RCTs. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2024, 176, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, H.; Liu, W.; Qu, S.; Ge, Y.; Song, J. Efficacy of Vigorous Physical Activity as an Intervention for Mitigating Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasstasia, Y.; Baker, A.L.; Lewin, T.J.; Halpin, S.A.; Hides, L.; Kelly, B.J.; Callister, R. Differential Treatment Effects of an Integrated Motivational Interviewing and Exercise Intervention on Depressive Symptom Profiles and Associated Factors: A Randomised Controlled Cross-over Trial among Youth with Major Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 259, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.L.; Brush, C.J.; Ehmann, P.J.; Alderman, B.L. A Randomized Trial of Aerobic Exercise on Cognitive Control in Major Depression. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 128, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, M. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (5th Edition). Ref. Rev. 2014, 28, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, D.L. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR). In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; 2010; pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-470-47921-6.

- Hong, Y.; Zeng, M.L. International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Knowl. Organ. 2022, 49, 496–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Koku, G. Beck Depression Inventory. Occup. Med. 2016, 66, 174–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, P.; Allerup, P.; Larsen, E.R.; Csillag, C.; Licht, R.W. The Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Scale (MADRS). A Psychometric Re-Analysis of the European Genome-Based Therapeutic Drugs for Depression Study Using Rasch Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 217, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocalevent, R.-D.; Hinz, A.; Brähler, E. Standardization of the Depression Screener Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the General Population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2013, 35, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinsohn, P.M.; Seeley, J.R.; Roberts, R.E.; Allen, N.B. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a Screening Instrument for Depression among Community-Residing Older Adults. Psychol. Aging 1997, 12, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokelainen, J.; Timonen, M.; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S.; Härkönen, P.; Jurvelin, H.; Suija, K. Validation of the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) in Older Adults. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2019, 37, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- reenberg, S.A. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). 2012.

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazeri, A.; Vahdaninia, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; Jarvandi, S. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): Translation and Validation Study of the Iranian Version. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Welch, V. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5 (Updated August 2024)[EB. OL]. Cochrane; 2024. 2025.

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-Bias VISualization (Robvis): An R Package and Shiny Web App for Visualizing Risk-of-Bias Assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cochrane Collaboration RevMan: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Tool for Researchers Worldwide | Cochrane RevMan Available online:. Available online: https://revman.cochrane.org/info (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- JASP Team JASP (Version 0.95.3)[Computer Software] Available online:. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Chin, E.C.; Yu, A.P.; Leung, C.K.; Bernal, J.D.; Au, W.W.; Fong, D.Y.; Cheng, C.P.; Siu, P.M. Effects of Exercise Frequency and Intensity on Reducing Depressive Symptoms in Older Adults With Insomnia: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, L.; Papoulias, I.; Petersson, E.-L.; Carlsson, J.; Waern, M. Exercise or Basic Body Awareness Therapy as Add-on Treatment for Major Depression: A Controlled Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 168, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickmeyer, A.; Smith, J.J.; Halpin, S.; McMullen, S.; Drew, R.; Morgan, P.; Valkenborghs, S.; Kay-Lambkin, F.; Young, M.D. Walk-and-Talk Therapy Versus Conventional Indoor Therapy for Men With Low Mood: A Randomised Pilot Study. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2025, 32, e70035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Z. Effect of Physical Exercise on Medical Rehabilitation Treatment of Depression. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2022, 28, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, 2013. ISBN 978-0-203-77158-7.

- Cooney, GM, Dwan, K, Greig, CA, Lawlor, DA, Rimer, J, Waugh, FR, McMurdo, M.; Mead, G. Exercise for Depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Schuch, F.B.; Dunn, A.L.; Kanitz, A.C.; Delevatti, R.S.; Fleck, M.P. Moderators of Response in Exercise Treatment for Depression: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 195, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, B.R.; McDowell, C.P.; Hallgren, M.; Meyer, J.D.; Lyons, M.; Herring, M.P. Association of Efficacy of Resistance Exercise Training With Depressive Symptoms: Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvam, S.; Kleppe, C.L.; Nordhus, I.H.; Hovland, A. Exercise as a Treatment for Depression: A Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 202, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firth, J.; Solmi, M.; Wootton, R.E.; Vancampfort, D.; Schuch, F.B.; Hoare, E.; Gilbody, S.; Torous, J.; Teasdale, S.B.; Jackson, S.E.; et al. A Meta-Review of “Lifestyle Psychiatry”: The Role of Exercise, Smoking, Diet and Sleep in the Prevention and Treatment of Mental Disorders. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noetel, M.; Sanders, T.; Gallardo-Gómez, D.; Taylor, P.; del Pozo Cruz, B.; van den Hoek, D.; Smith, J.J.; Mahoney, J.; Spathis, J.; Moresi, M.; et al. Effect of Exercise for Depression: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ 2024, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; O’Connor, E.; Ferguson, T.; Eglitis, E.; et al. Effectiveness of Physical Activity Interventions for Improving Depression, Anxiety and Distress: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Stead, T.S.; Ganti, L. Determining a Meaningful R-Squared Value in Clinical Medicine. Acad. Med. Surg. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Jiménez, A.; Rubio-Valles, M.; Ramos-Hernández, J.A.; González-Rodríguez, E.; Moreno-Brito, V. Adaptations in Mitochondrial Function Induced by Exercise: A Therapeutic Route for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, G.; Faulkner, G. Physical Activity and the Prevention of Depression: A Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 45, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, F.B.; Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Rosenbaum, S.; Ward, P.B.; Silva, E.S.; Hallgren, M.; Ponce De Leon, A.; Dunn, A.L.; Deslandes, A.C.; et al. Physical Activity and Incident Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; 1st ed.; Geneva: World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020. ISBN 978-92-4-001512-8.

- NICE Recommendations | Depression in Adults: Treatment and Management | Guidance | NICE Available online:. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG222/chapter/recommendations (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Moreira-Neto, A.; Neves, L.M.; Miliatto, A.; Juday, V.; Marquesini, R.; Lafer, B.; Cardoso, E.F.; Ugrinowitsch, C.; Nucci, M.P.; Silva-Batista, C. Clinical and Neuroimaging Correlates in a Pilot Randomized Trial of Aerobic Exercise for Major Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 347, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, R.S.; Aghajanian, G.K.; Sanacora, G.; Krystal, J.H. Synaptic Plasticity and Depression: New Insights from Stress and Rapid-Acting Antidepressants. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandola, A.; Ashdown-Franks, G.; Hendrikse, J.; Sabiston, C.M.; Stubbs, B. Physical Activity and Depression: Towards Understanding the Antidepressant Mechanisms of Physical Activity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 107, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y. Physical Exercise and Mental Health among Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Social Competence. Front. Public Health 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, S.; Feng, C.; Wang, S. Leisure Time Exercise and Depressive Symptoms in Sedentary Workers: Exploring the Effects of Exercise Volume and Social Context. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, P.A. ; Brown, JenniferV. E.; Pervin, J.; Brabyn, S.; Pateman, R.; Breedvelt, J.; Gilbody, S.; Stancliffe, R.; McEachan, R.; White, PiranC.L. Nature-Based Outdoor Activities for Mental and Physical Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. SSM - Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Chen, W.; Wang, H.; Yu, T. How Does Physical Exercise Influence Self-Efficacy in Adolescents? A Study Based on the Mediating Role of Psychological Resilience. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Tu, Y.; Su, Y.; Jin, L.; Tian, Y.; Chang, X.; Yang, K.; Xu, H.; Zheng, J.; Wu, D. The Mediating Effect of Self-Efficacy and Physical Activity with the Moderating Effect of Social Support on the Relationship between Negative Body Image and Depression among Chinese College Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, É.M.; Monteiro, D.; Bento, T.; Rodrigues, F.; Cid, L.; Vitorino, A.; Figueiredo, N.; Teixeira, D.S.; Couto, N. Analysis of the Effect of Different Physical Exercise Protocols on Depression in Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sports Health 2024, 16, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heissel, A.; Heinen, D.; Brokmeier, L.L.; Skarabis, N.; Kangas, M.; Vancampfort, D.; Stubbs, B.; Firth, J.; Ward, P.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; et al. Exercise as Medicine for Depressive Symptoms? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Meta-Regression. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1049–1057, Author 1, A.B.; Author 2, C.D. Title of the article. Abbreviated Journal Name Year, Volume, page range. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author (Year) | Sample size (treatment/control) | Age, y | Gender M/F | Instrument | Grade of depression | Drugs | Intervention (treatment/control) | Time of treatment | Number of sessions | Exercise Intensity |

| Carneiro et al. (2015) | 9/10 | 18-65 | 0/19 | BDI-II | Low to moderate | Yes | Aerobic exercise/rest | 16 weeks | 39 | 65-80% MHR |

| Chau et al. (2022) | 42/42 | 18-64 | 17/67 | HAM-D | High | Yes | Multimodal exercise/rest | 12 weeks | 36 | 50-70% MHR |

| Cheung & Lee (2018) | 15/17 | 18-65 | 7/34 | HADS | High | Yes | Aerobic exercise/rest | 12 weeks | 36 | 60% MHR |

| Chin et al. (2022) | 9/9 | ≥ 60 | 3/18 | HADS | Low to moderate | NM | Aerobic exercise/light stretching | 12 weeks | 12 | ∼3.25 METs |

| Chin et al. (2022) | 9/9 | ≥ 60 | 3/18 | HADS | Low to moderate | NM | Aerobic exercise/light stretching | 12 weeks | 36 | ∼3.25 METs |

| Chin et al. (2022) | 10/9 | ≥ 60 | 4/19 | HADS | Low to moderate | NM | Aerobic exercise/light stretching | 12 weeks | 12 | ∼6.5 METs |

| Chin et al. (2022) | 9/9 | ≥ 60 | 3/18 | HADS | Low to moderate | NM | Aerobic exercise/light stretching | 12 weeks | 36 | ∼6.5 METs |

| Danielsson et al. (2014) | 18/14 | 18-65 | 10/32 | MADRS-S | Low to moderate | Yes | Aerobic exercise/rest | 10 weeks | 20 | Moderate |

| Dickmeyer et al. (2025) | 20/17 | 18-70 | 37/0 | DASS-21 | Low to moderate | NM | Aerobic exercise/rest | 6-weeks | 6 | 3.5 METs |

| Gerber et al. (2020) | 14/11 | 18-61 | 0/25 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Aerobic exercise/rest | 6 weeks | 18 | 60-75% MHR |

| Keller-Varady et al. (2023) | 15/14 | 18-60 | 4/27 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Multimodal exercise/rest | 6 weeks | 36 | Moderate-to-vigorous |

| Kerling et al. (2017) | 22/20 | 18-60 | 26/16 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Aerobic exercise/rest | 6 weeks | 18 | 50% MHR |

| La Rocque et al. (2021) | 20/15 | 18-65 | 0/35 | HAM-D | High | Yes | Multimodal exercise/rest | 8 weeks | 16 | Moderate |

| La Rocque et al. (2021) | 18/15 | 18-65 | 0/33 | HAM-D | High | Yes | Yoga/rest | 8 weeks | 16 | Low to moderate |

| Lavretsky et al. (2011) | 33/35 | ≥ 60 | 26/42 | HAM-D | High | Yes | Tai Chi/rest | 10 weeks | 10 | Low to moderate |

| Legrand & Neff (2016) | 14/10 | 27-67 | 8/16 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Aerobic exercise/rest | 10 days | 10 | 65-75% MHR |

| Legrand & Neff (2016) | 11/10 | 27-67 | 8/17 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Stretching/rest | 10 days | 10 | 65-75% MHR |

| Moraes et al. (2019) | 9/7 | ≥ 60 | 3/13 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Aerobic exercise/rest | 12 weeks | 24 | 70% MHR |

| Moraes et al. (2019) | 9/7 | ≥ 60 | 3/13 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Resistance training/rest | 12 weeks | 24 | 70% 1-MR |

| Norouzi et al. (2024) | 17/17 | 18-70 | 8/26 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Multimodal exercise/rest | 8 weeks | 16 | 70% MHR |

| Olson et al. (2017) | 15/15 | 18-30 | 6/24 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Aerobic exercise/light stretching | 8 weeks | 24 | 40–65% HR reserve |

| Siddarth et al. (2023) | 55/58 | ≥ 60 | 31/82 | HAM-D | High | Yes | Tai Chi/rest | 12 weeks | 12 | Low to moderate |

| Szuhany & Otto (2019) | 15/16 | 18-65 | 5/16 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Aerobic exercise/light stretching | 12 weeks | 12 | Moderate |

| Tolahunase et al. (2018) | 29/29 | 19-50 | 27/31 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Yoga/rest | 12 weeks | 60 | Low to moderate |

| Wang & Li (2022) | 30/30 | NM | NM | HAM-D | High | Yes | Aerobic exercise/rest | 8 weeks | 32 | 120-150 beats/min |

| Zhang et al. (2022) | 20/19 | 30-60 | 4/35 | BDI-II | High | Yes | Tai Chi/rest | 12 weeks | 24 | Low to moderate |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [26], Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) [27], Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) [27], The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [31], Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) [32], or Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [33], Heart Rate (HR), Maximal Heart Rate (MHR), Maximal Repetition (MR), Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET). | ||||||||||

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p-value | R2 adjusted |

|

| M₁ | Regression | 19.056 | 1 | 19.056 | 39.432 | < .001 | 0.612 |

| Residual | 12.082 | 25 | 0.483 | ||||

| Total | 31.138 | 26 | |||||

| M₂ | Regression | 25.011 | 6 | 4.169 | 13.608 | < .001 | 0.744 |

| Residual | 6.127 | 20 | 0.306 | ||||

| Total | 31.138 | 26 | |||||

| Note. M₁ includes Workload; M₂ includes Workload and Instrument | |||||||

| Subgroup | F | df₁ | df₂ | p-value | ||

| Workload | Full dataset | 9.759 | 1 | 20 | .005 | |

| Low depression | 15.823 | 1 | 2 | .058 | ||

| High depression | 6.582 | 1 | 15 | .022 | ||

| Instrument | Full dataset | 3.515 | 4 | 20 | .025 | |

| Low depression | 10.211 | 3 | 2 | .091 | ||

| High depression | 4.385 | 2 | 15 | .032 | ||

| Note. Fixed effects tested using Knapp and Hartung adjustment. | ||||||

| Quality Characteristics | Covered in Meta-Analysis? | Details |

| Protocol pre-registration | Yes | PROSPERO (CRD420251121919) |

| Use of PRISMA | Yes | PRISMA 2020 reporting |

| Independent screening and data extraction | Yes | Two independent reviewers; third reviewer for consensus |

| Comprehensive search | Yes | Multiple databases, PICOS strategy |

| Standardized eligibility criteria | Yes | DSM/ICD diagnosis, validated instruments, exclusion of comorbidities/med changes |

| Use of validated depression assessment tools | Yes | BDI, HAM-D, PHQ-9, CES-D, MADRS, etc. |

| Risk of bias (RoB 2) assessment | Yes | All five domains, two blinded reviewers |

| Sensitivity/subgroup analyses | Yes | Performed as part of results |

| Transparent study flow and exclusion reporting | Yes | PRISMA diagram, full text review and exclusion reasons |

| Handling of missing data | Yes | SDs estimated from SEs, CIs, p-values if needed |

| Statistical rigor (heterogeneity, influence, funnel) | Yes | Tau², Q-test, I², Cook's D, studentized residuals, funnel plot asymmetry |

| Assessment of comorbidity | Yes | Included as a section in results |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | Yes (as RoB domain) | Not always feasible for exercise; assessed as risk of bias domain |

| Adverse event/safety reporting | Not explicitly | Not detailed in the provided text |

| Power analysis/sample size in included studies | Yes | In meta-analysis description |

| Long-term follow-up | Not systematically | Mentioned as a gap, not systematically analyzed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).