1. Introduction

Adapted exercise and sport represent key components of preventive, therapeutic, and inclusive strategies across clinical and community contexts, offering multidimensional benefits for individuals with chronic and complex conditions. Despite the strong evidence base supporting their safety and efficacy, intervention design and evaluation remain heterogeneous and inconsistently reported, which limits reproducibility, scalability, and translation into real-world practice [

1,

2,

3,

4]. A standardized, operational methodological framework is therefore needed to integrate the essential phases of adapted exercise programs, such as functional assessment, individualized prescription, progression, supervision, and outcome evaluation, while ensuring both scientific rigor and clinical feasibility [

5,

6]. Such a framework should align with contemporary exercise science principles (FITT-VP model), emphasize safety, adaptability, and individualization, and facilitate the development of comparable data across diverse populations and health systems [

7,

8].

Traditional exercise guidelines provide clear evidence of dose–response relationships between physical activity and health outcomes; however, their implementation across heterogeneous clinical and community environments remains inconsistent. Variability in assessment protocols, exercise dosage, reporting of adherence, and evaluation metrics continue to hamper the integration of adapted exercise into multidisciplinary care pathways [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Therefore, this methodological paper proposes a pragmatic, standardized, and scalable framework for designing and evaluating adapted exercise and sport interventions. By consolidating key components, i.e. screening and risk stratification, functional assessment, individualized prescription, structured supervision, and multidimensional evaluation, the framework promotes fidelity, comparability, and scalability. It aims to guide researchers, clinicians, and exercise professionals toward the systematic development of evidence-informed, person-centered, and context-responsive adapted exercise programs that can be effectively implemented across clinical and community environments. Furthermore, the framework extends to adapted sport, where exercise principles are translated into structured, rule-based, and socially engaging activities that foster autonomy, inclusion, and performance potential.

2. Conceptual Framework

The proposed framework offers a structured, adaptable, and implementation-oriented model for designing, delivering, and evaluating adapted exercise and sport interventions. It applies across clinical and community contexts and progressively extends to adapted sport environments, where therapeutic, functional, and performance objectives coexist within structured and inclusive settings. It is grounded in the principles of individualization, safety, progression, and multidimensional monitoring, aligning with contemporary exercise science and public health recommendations [

4,

5,

9]. The framework comprises six interconnected components, i.e. screening and risk stratification, functional and psychosocial assessment, individualized prescription, supervision and monitoring, outcome tracking and feedback, and reporting/knowledge translation, which together support fidelity, reproducibility, and scalability of adapted exercise programs.

This structure synthesizes established exercise guidelines (e.g., ACSM) and leading implementation-science models, such as RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) [

14,

15], TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) [

3,

5], and CERT (Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template) [

16]. By integrating these complementary models, the framework ensures methodological consistency across the full exercise–sport continuum—from clinical and therapy-oriented exercise to skill development, inclusive participation, and adapted competition.

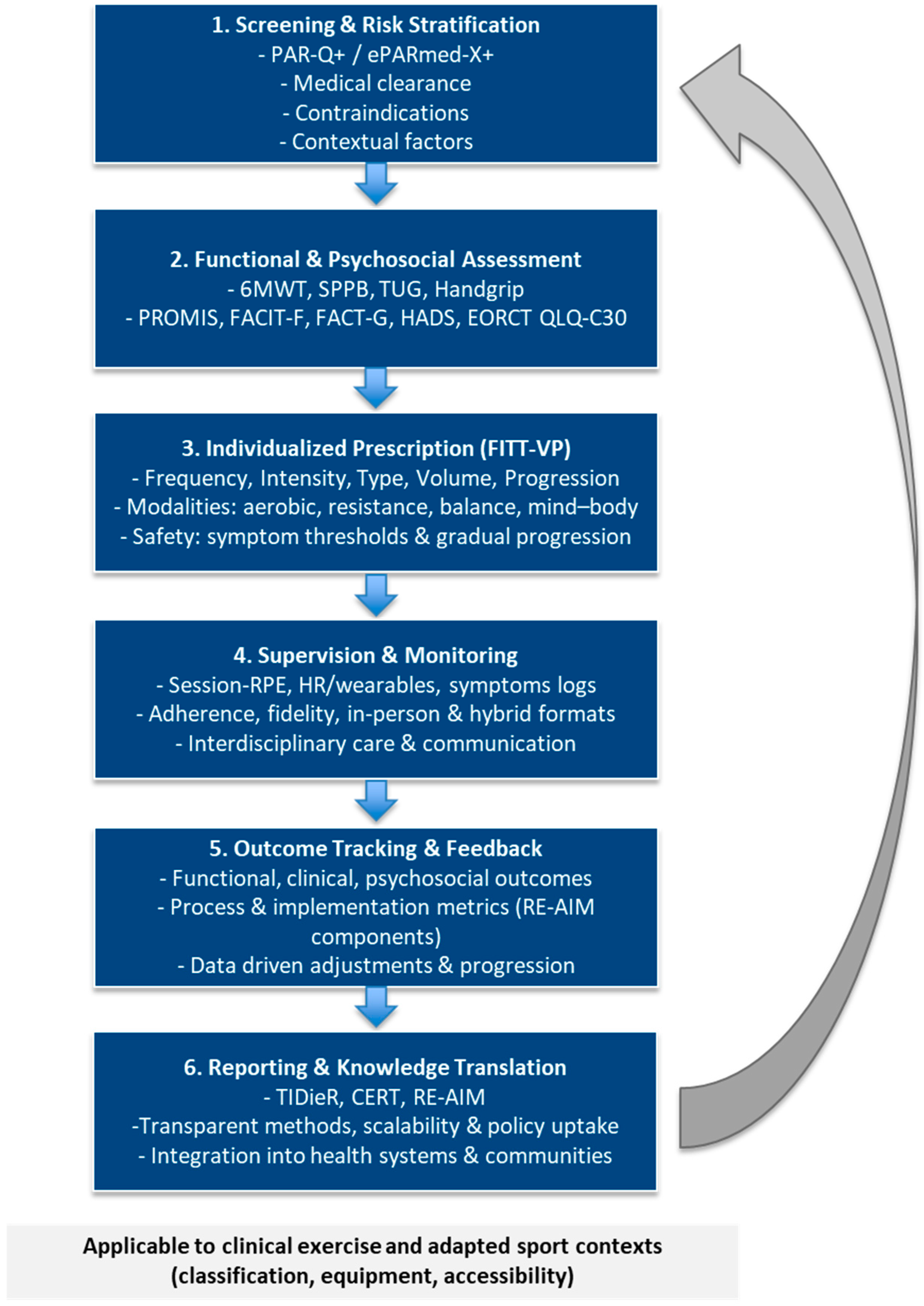

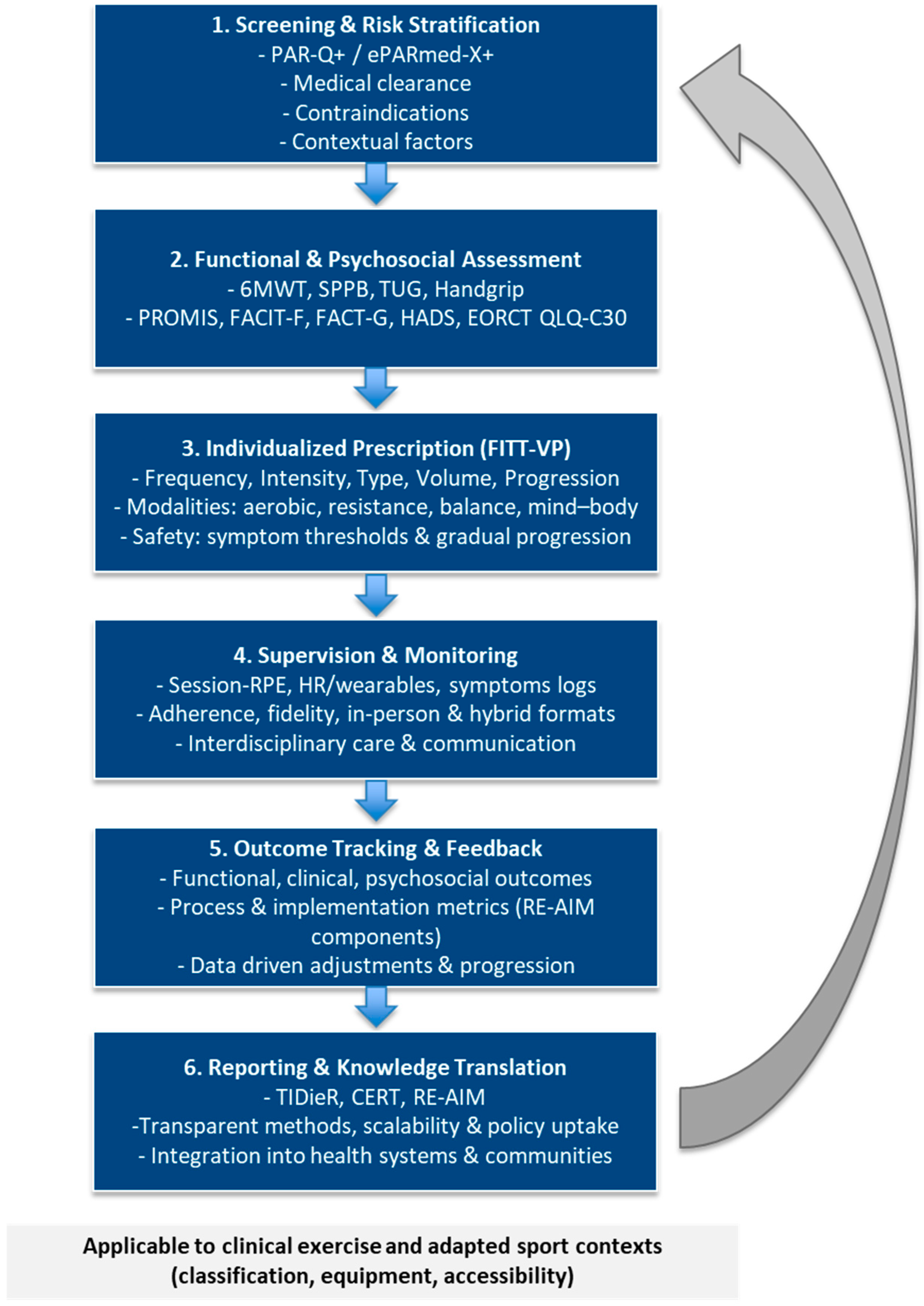

Figure 1 provides a visual synthesis of this iterative workflow, integrating FITT-VP principles, safety management, and implementation metrics (RE-AIM, TIDieR, CERT) interact dynamically within a continuous evaluation cycle.

2.1. Screening and Risk Stratification

A safe and effective program begins with structured pre-participation screening to identify contraindications, risk factors, and individual limitations. Evidence-based tools such as the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q+ and ePARmed-X+) are recommended for systematic risk classification [

17]. Screening should integrate medical history, medication review, and symptom-based triage, following ACSM’s risk stratification model and the

“start low, progress slow” principle for individuals with chronic or complex conditions [

5,

7]. This initial module ensures participant safety, eligibility, and baseline clearance before exercise initiation. For participants in adapted-sport contexts, screening should additionally cover functional classification criteria, sport-specific demands, and environmental safety requirements, ensuring both equity and inclusion.

2.2. Functional and Psychosocial Assessment

This phase establishes the participant’s baseline profile, combining validated functional tests such as the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT), Timed Up and Go (TUG), 30-s Chair Stand, Handgrip Strength, and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), which are widely used to assess mobility and endurance [

18,

19,

20]. Handgrip strength remains a robust predictor of functional decline and mortality in older adults [

21]. Patient-reported outcomes should capture fatigue, mood, quality of life, and self-efficacy using validated tools such as PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System), FACIT/FACT-G v4, EORTC QLQ-C30, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [

22,

23,

24,

25].

Contextual and environmental factors, including accessibility, social support, and available resources, should be mapped according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework, supported, when possible, by digital assessment platforms or tele-based tools [

26]. For adapted sports participants, assessment should additionally evaluate sport-specific motor skills, coordination, and wheelchair or prosthetic efficiency, while psychosocial tools may explore motivation and readiness for sport inclusion.

2.3. Individualized Prescription

Exercise prescription should follow the FITT-VP model, ensuring that each parameter (frequency, intensity, time, type, volume, progression) is tailored to functional capacity and clinical status [

7]. Within the adapted-sport continuum, these principles guide not only therapy-oriented programs but also progressive training toward skill acquisition and safe competition preparation.

Core components include aerobic and resistance training, with balance, flexibility, and mind–body practices integrated as indicated by the participant’s goals and condition [

4,

5]. The prescription component operationalizes the FITT-VP model into practical rules suitable for clinical and community programs:

Intensity can be prescribed via objective measures (%HRR, %1RM) or subjective scales (RPE, talk test).

Volume and progression must be adapted according to tolerance and recovery.

Safety should be maintained through individualized symptom thresholds and real-time monitoring, applying clear stop or regression rules for pain, dyspnea, or excessive fatigue.

In adapted sports programs, training parameters should align with functional classification, equipment adaptation, and environmental accessibility, balancing safety with performance goals [

27].

2.4. Supervision and Monitoring

Supervision models can range from in-person clinical oversight to remote or hybrid tele-exercise models, depending on context and resources, with interdisciplinary communication between clinicians, exercise specialists, and adapted-sport professionals. Monitoring tools such as session-RPE, digital training logs, or wearable sensors help ensure adherence, detect adverse events, and guide progression [

28,

29,

30]. Feedback mechanisms, both physiological and behavioral, create a dynamic adjustment loop supporting self-regulation, safety, and sustained engagement.

In adapted-sport contexts, real-time monitoring, load-management records, and communication between health and sport specialists optimize performance, prevent injuries, and maintain motivation.

2.5. Outcome Tracking & Feedback

This component integrates functional, clinical, psychosocial, and process-related outcomes into a continuous feedback system that guides progression and program adjustment. In adapted sport, outcome tracking should extend beyond health and function to include sport-specific performance indicators, participation level, and psychosocial metrics such as motivation, teamwork, and sense of belonging.

Key evaluation domains include:

Functional outcomes: cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, balance, mobility.

Clinical outcomes: biomarkers, treatment tolerance, disease-specific indicators.

Psychosocial outcomes: fatigue, mood, quality of life, self-efficacy.

Process outcomes: adherence, feasibility, and fidelity [

31].

A multidimensional tracking system allows clinicians and researchers to link observed improvements with specific intervention parameters, enhancing fidelity, external validity, and reproducibility [

2,

14]. This iterative cycle generates actionable data for reporting and knowledge translation, supporting progression along the exercise–sport continuum, from clinical improvement to sustainable participation and inclusion.

2.6. Reporting and Knowledge Translation

This final phase emphasizes transparent reporting and dissemination of adapted exercise and sport programs. Interventions should follow the TIDieR and CERT checklists to document components, delivery methods, supervision, and fidelity [

2,

16]. Implementation outcomes such as reach, adoption, feasibility, and maintenance (RE-AIM) should be systematically reported with defined indicators and formulas to enhance comparability and facilitate policy translation. This module bridges research and practice, enabling the integration of adapted exercise and sport programs into clinical guidelines, community services, and professional training [

14,

15]. For adapted sport, transparent reporting should also detail classification procedures, equipment adaptations, and inclusive delivery strategies, ensuring equity, safety, and comparability across sport-based programs.

Table 1 summarizes the purpose, scope, and key features of RE-AIM, TIDieR, and CERT, which collectively ensure transparent reporting, replicability, and scalability of adapted exercise and sport interventions. Detailed TIDieR and CERT checklists, along with the RE-AIM indicator matrix and examples of completed tables, are available in the

Supplementary Material (Tables S1–S3) to support comprehensive reporting and facilitate replication.

Table 2 illustrates how RE-AIM, TIDieR, and CERT align with the six components of the proposed framework, highlighting their complementary roles in ensuring fidelity, scalability, and comprehensive reporting.

3. Evaluation Dimensions

Evaluation represents a critical component of any adapted exercise and sport intervention, ensuring that effectiveness, safety, and feasibility can be objectively quantified and compared across programs and settings. An effective evaluation strategy must integrate multidomain outcomes, i.e. functional, clinical, psychosocial, and behavioral, together with process and implementation indicators describing adherence, fidelity, scalability, and contextual feasibility [

14,

31]. In the context of adapted sport, evaluation also extends to performance- and participation-related outcomes, capturing physiological adaptations, functional progression, and social inclusion effects. This multidimensional approach acknowledges the inherent complexity of adapted exercise and sport interventions, where physical, psychological, and social gains interact dynamically with contextual, environmental, and motivational factors [

1]. In practice, this means predefining a core reporting set across domains, including standardized time points (e.g., baseline, 8–12 weeks, 6 months) and explicit decision thresholds for progression, maintenance, or de-escalation.

3.1. Functional and Clinical Outcomes

Functional outcomes represent the measurable physiological adaptations resulting from exercise training, typically captured through aerobic capacity, muscular strength, balance, and mobility tests. Valid and feasible field tests, such as the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT), Timed Up and Go (TUG), 30-s Chair Stand, and Handgrip Strength, are widely recognized indicators of global functional capacity [

18,

19,

20,

21].

Clinical outcomes should be tailored to the specific condition, capturing treatment tolerance, symptom burden, and relevant biomarkers (e.g., glucose control, lipid profile, inflammatory markers). Standardized measurement and reporting protocols enhance comparability across populations, disease conditions, and adapted sport modalities, supporting multi-site synthesis [

4,

5]. For adapted sport, performance-relevant functional markers (e.g., agility tests, wheelchair propulsion, sport-specific coordination tasks) should be added when appropriate, ensuring safety and consistency with classification rules.

3.2. Psychosocial and Quality-of-Life Measures

Because adapted exercise and sport influence both mental health and social well-being, evaluation should incorporate validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) targeting fatigue, mood, self-efficacy, and quality of life. Instruments such as the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue (FACIT-F), the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G v4), EORTC QLQ-C30, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) are frequently applied in clinical exercise research [

22,

23,

24,

25]. In the adapted-sport domain, additional PROMs such as the WHOQOL-BREF or the Participation Scale capture self-perceived inclusion, autonomy, and social connectedness, key indicators of psychosocial health and participation. These measures complement physiological and functional data and align with the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework [

26]. When programs target behavior change, consider adding motivation/behavioral regulation tools (e.g., BREQ-3) and participation frequency/intensity logs.

3.3. Process and Implementation Indicators

Beyond outcomes, process evaluation focuses on how interventions are designed, delivered, supervised, and received in practice. Indicators such as adherence (attendance and compliance), fidelity (alignment with the intended protocol), dose intensity, reach, acceptability, and feasibility provide a comprehensive understanding of implementation success [

31]. Frameworks like RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) emphasize both internal and external validity, guiding translation from controlled research to routine practice [

14,

15]. In adapted sport, process indicators should further include coach involvement, equipment accessibility, environmental suitability, and athlete classification accuracy, which are essential for inclusiveness and safe participation. Reporting adverse events, injuries, or participant burden further informs safety, sustainability, and feasibility, providing context for program optimization and policy evaluation. To support replication, pair process metrics with clear documentation of delivery dose (planned vs. completed), modification logs, and reasons for non-adherence.

3.4. Economic and Feasibility Considerations

Economic evaluation is essential for informing healthcare and community decision-making, quantifying the cost–benefit balance of adapted exercise and sport interventions. Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses, often based on quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) or healthcare service utilization, are increasingly employed to demonstrate the value of movement-based health promotion strategies [

32,

33]. In adapted sport programs, feasibility metrics also include equipment customization, venue accessibility, and the training of specialized personnel (e.g., adapted exercise and sport specialists). These analyses inform scalability and support the integration of adapted exercise and sport into preventive and clinical care pathways, as well as educational and community networks. Where relevant, include micro-costing of assistive devices and facility adaptations, and report cost per participant retained at follow-up.

3.5. Toward Standardization and Core Outcome Sets

The development of core outcome sets (COS) is essential to harmonize evaluation practices across trials and applied programs, reducing heterogeneity and improving reproducibility. Initiatives such as COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) and COSMIN (Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments) provide methodological guidance for defining core domains and selecting instruments with robust measurement properties: validity, reliability, responsiveness, and interpretability [

34]. Extending COSMIN and COMET principles to adapted sport can align health, performance, and participation indicators, facilitating cross-sector comparisons between clinical, community, and competitive contexts. Establishing a standardized outcome framework will strengthen meta-analytic evidence, improve comparability across studies, and accelerate the translation of research into clinical and community practice. At minimum, report the same core domains across time points and specify a priori thresholds that trigger progression or program modification.

Table 3 summarizes all core domains, indicators, and recommended measurement tools, integrating functional, clinical, psychosocial, process, and implementation outcomes, along with safety and follow-up indicators.

In summary, the evaluation of adapted exercise and sport interventions must move beyond single-domain outcomes toward an integrated system that captures physiological, psychological, behavioral, performance, and inclusion dimensions. Such comprehensive evaluation supports transparency, comparability, and long-term sustainability, reinforcing adapted exercise and sport as integral components of evidence-based, person-centered, and inclusive health practice.

4. Application Scenarios

The proposed framework can be applied and adapted across multiple clinical, community, and public-health contexts, illustrating its flexibility, scalability, and cross-disciplinary relevance. Although disease-specific exercise guidelines exist, their real-world implementation still depends heavily on local resources, professional expertise, and participant characteristics, underscoring the need for a standardized process adaptable to different settings. Applying a single, structured workflow, i.e. screening, assessment, individualized prescription, monitoring, and evaluation, enhances comparability across programs and ensures that adapted exercise and sport remain safe, personalized, and outcome-oriented [

4,

5]. Within this continuum, adapted and inclusive sport represents the natural extension of adapted exercise, sustaining long-term adherence, functional autonomy, and social participation through structured, engaging physical activities.

4.1. Oncology

Exercise has become an evidence-based and essential component of comprehensive cancer care. Evidence demonstrates improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness, muscle mass, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and quality of life among cancer survivors engaging in structured exercise programs [

10,

11,

35,

36,

37]. Within this framework, oncology interventions should include:

Pre-exercise screening for treatment-related contraindications (anemia, cardiotoxicity, neuropathy).

Functional and psychosocial assessment using fatigue and quality-of-life scales (FACIT-F, FACT-G, EORTC QLQ-C30).

Prescription emphasizing low-to-moderate aerobic and resistance training, progressing cautiously as tolerance increases.

Outcome tracking capturing both physical recovery and psychosocial well-being.

Supervision may range from clinical (during active treatment) to community-based or self-managed maintenance phases once clinical stability is achieved.

Adapted or low-impact sport activities, such as walking groups, yoga, Tai Chi, swimming, or dance-based sessions, can complement structured exercise, enhancing motivation, peer support, and reintegration after treatment. These activities maintain exercise benefits while fostering psychological resilience and community belonging [

5,

11].

4.2. Metabolic and Cardiovascular Disorders

In individuals with type 2 diabetes, obesity, or metabolic syndrome, exercise interventions primarily aim to improve insulin sensitivity, lipid profile, and blood-pressure regulation while reducing cardiometabolic risk [

38,

39]. The framework applies by integrating medical clearance, metabolic risk stratification, and individualized intensity prescription:

Aerobic components (walking, cycling, aquatic exercise) at 40–60% HRR are complemented by resistance training targeting large muscle groups.

Process indicators, such as adherence, perceived exertion, and energy expenditure, help refine dosage.

Implementation outcomes, such as reach, adoption, and feasibility, determine sustainability in public-health and workplace programs [

14].

Recent trials show that multicomponent exercise training produces measurable improvements in hemodynamic parameters, physical fitness, and quality of life, supporting its inclusion in both rehabilitation and preventive programs [

40,

41,

42]. Adapted sport modalities such as Nordic walking, cycling, or low-intensity team games (e.g., small-sided football, pickleball) can act as transitional bridges from clinical exercise programs to autonomous active living, reinforcing metabolic control and social engagement [

4,

43].

4.3. Chronic Respiratory Conditions

In chronic respiratory conditions (e.g., COPD), adapted exercise improves ventilatory efficiency, functional independence, and quality of life [

12,

13]. Assessment should include the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT), Borg Dyspnea Scale, and continuous oxygen-saturation monitoring, complemented by symptom logs and medication review when indicated. Prescription typically favors interval or combined aerobic–strength training with close supervision and gradual progression. Outcome tracking should integrate clinical and behavioral domains (exacerbation rate, physical-activity level, self-management competence).

Transitioning from therapeutic exercise to low impact adapted sports such as aquatic fitness, seated volleyball, or walking football helps maintain ventilatory efficiency and engagement while supporting psychological well-being. These activities also reduce sedentary behavior and anxiety associated with breathlessness, supporting self-efficacy and emotional well-being [

4].

4.4. Neurological and Neuromuscular Disorders

In neurological and neuromuscular disorders (e.g., multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, cerebral palsy), multicomponent adapted programs combining strength, balance, and cognitive-motor tasks enhance motor control, coordination, and functional independence. Balance, dual-task, and mind–body modalities (e.g., Tai Chi, dance, Pilates) improve stability and mobility while addressing fatigue and rigidity [

44,

45].

Within the adapted-sport continuum, structured activities such as Boccia, wheelchair basketball, table tennis, para-dance, or adaptive cycling, provide functional, motivational, and social benefits. These modalities promote participation, self-efficacy, and empowerment, representing an advanced stage of functional recovery and social reintegration [

46].

Outcome evaluation should include gait and balance testing, validated fatigue and mobility scales, and participation measures, capturing both physical and psychosocial domains.

4.5. Community and Public-Health Settings

When applied beyond clinical contexts, the framework supports health promotion, social inclusion, and community resilience. Community-based exercise hubs and tele-supervised programs can expand reach to older adults or individuals with limited access to healthcare [

28,

47]. Standardized assessment tools and outcome metrics ensure fidelity even when supervision is minimal. Implementation of research focusing on feasibility, acceptability, and cost guides large-scale adoption and integration into preventive services.

Inclusive community-sport initiatives such as running or walking clubs, adapted-sport centers, or inter-generational physical-activity programs, illustrate how therapeutic exercise principles can evolve into sustainable active-living ecosystems [

48]. These programs contribute to population-level physical literacy, reduce health disparities, and strengthen intersectoral collaboration between healthcare, education, and sport systems [

49].

4.6 Adapted Sport and Recreational Contexts

Adapted sport represents the highest level of the exercise–sport continuum, extending exercise prescription principles into structured, rule-based, and goal-oriented activities designed for individuals with disabilities or chronic health conditions. Within the proposed framework, adapted sport is conceptualized as a multidimensional extension of therapeutic exercise, merging health, recreational, and performance objectives within inclusive, rule-based environments. Assessment and risk stratification remain essential, but emphasis shifts toward functional capacity, skill acquisition, and sport-specific performance monitoring, ensuring both safety and engagement [

50,

51]. Core process indicators, such as adherence, motivation, and social participation, become critical outcomes alongside traditional physiological measures.

The framework supports a progressive, evidence-based transition from clinical exercise to sport participation, guided by readiness, accessibility, and interdisciplinary collaboration among clinicians, kinesiologists, coaches, and sport federations.

Implementation metrics should further evaluate inclusive-sport initiatives across schools, communities, and rehabilitation networks, assessing reach, feasibility, sustainability, and equity of participation [

52].

Ultimately, adapted and inclusive sport is not merely the endpoint of rehabilitation and clinical exercise phase but a lifelong vehicle for participation, empowerment, and health maintenance.

5. Practical Recommendations

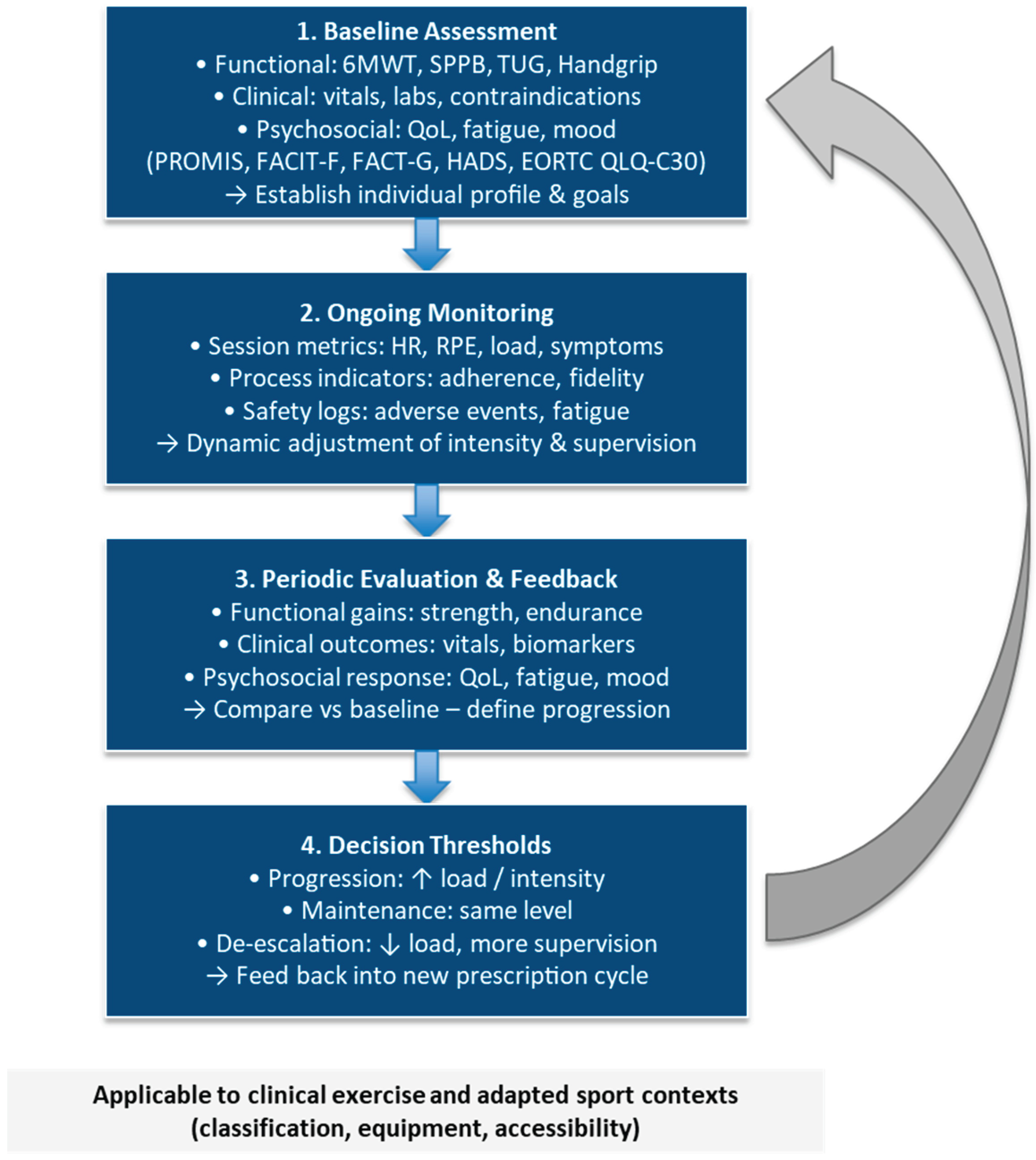

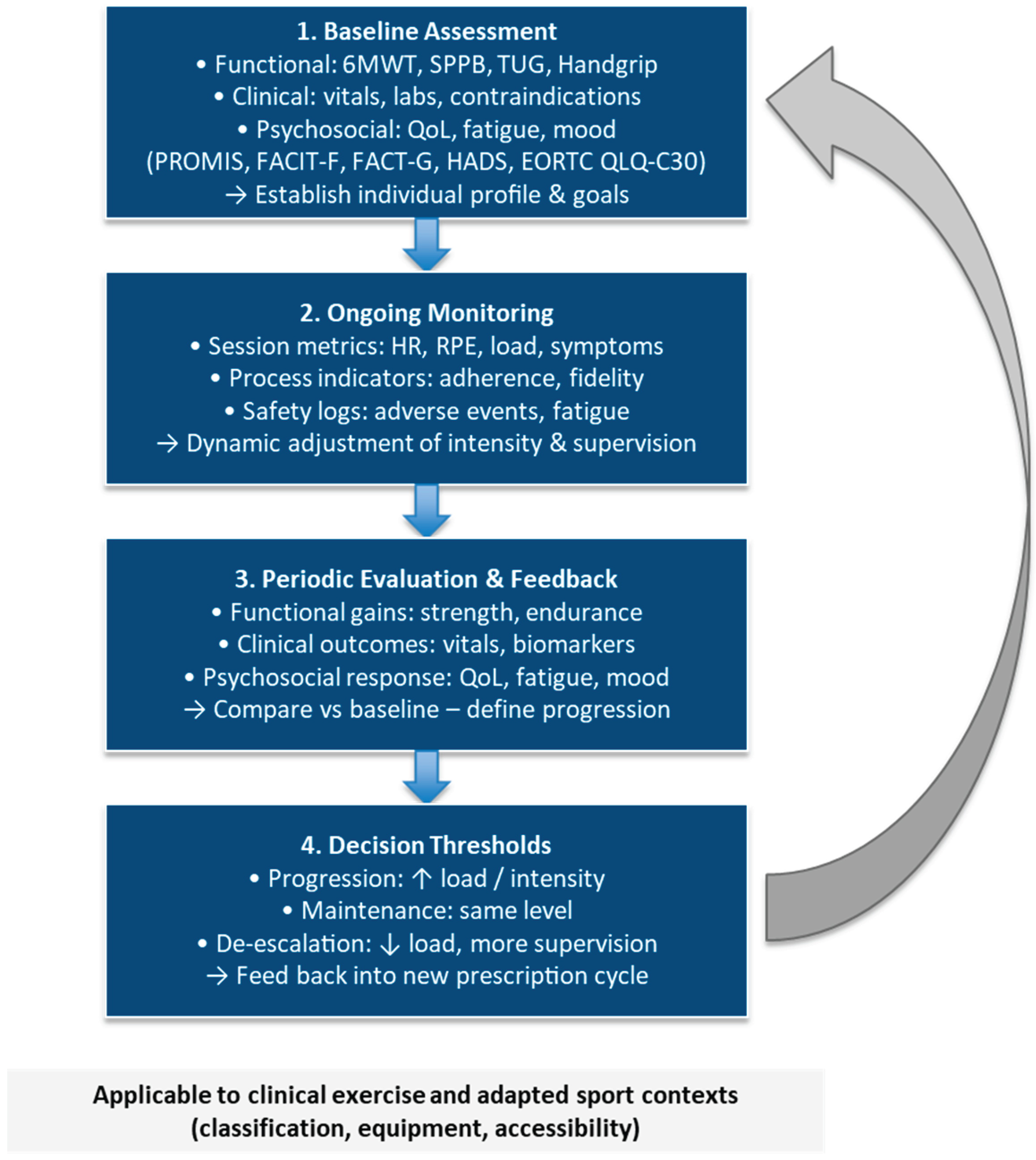

The proposed operational model translates the conceptual framework into a pragmatic and modular evaluation cycle for adapted exercise and sport programs. It organizes assessment and monitoring into four interconnected modules, i.e. baseline assessment, ongoing monitoring, periodic evaluation and feedback, and decision thresholds, linked by a continuous feedback loop. Each module integrates functional, clinical, and psychosocial outcomes together with process and implementation metrics (e.g., adherence, fidelity, feasibility, safety), to guide individualized adjustments.

Decision thresholds should reference minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs), predefined safety triggers (e.g., adverse events, symptom thresholds), and adherence milestones to standardize progression, maintenance, or de-escalation across settings.

This modular approach supports dynamic, data-driven evaluation, ensures safe progression, and enhances scalability from clinical to community and adapted-sport environments. The same logic applies to adapted and inclusive sport, where iterative monitoring and feedback cycles facilitate skill acquisition, performance optimization, and sustained participation across recreational and competitive contexts.

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of this cyclical evaluation plan, illustrating how baseline data, real-time monitoring, and periodic reviews inform progression, maintenance, or de-escalation decisions within an iterative prescription cycle.

5.1 Core Assessment Battery

A standardized core assessment battery should precede any adapted exercise program to establish baseline safety and functional status. This minimal set ensures comparability across settings and supports individualized program design. The core battery includes:

All assessments should follow standardized protocols, be repeated at predefined intervals (e.g., every 8–12 weeks), and be documented in a uniform format to enable longitudinal tracking and benchmarking. For adapted sport participants, include sport-specific motor tasks, classification-relevant tests (e.g., strength symmetry, wheelchair or prosthesis efficiency), and participation measures to ensure fair, safe, and inclusive engagement.

Table 4 provides recommended tools by domain and setting, supporting consistent application of the core assessment battery across clinical, community, and adapted-sport programs.

5.2 Prescription and Progression

Exercise programs should adhere to the FITT-VP (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Volume, Progression) model, ensuring individualized stimulus, adequate recovery, and safety [

5,

7]. The same structure applies across the adapted exercise–sport continuum, where the goal gradually shifts from therapeutic improvement to skill acquisition, participation, and, when appropriate, performance enhancement.

Key components:

Aerobic training: 3–5 sessions per week, 30–60 min, at 40–70% HRR or RPE 11–14 [

28].

Resistance training: 2–3 non-consecutive days, 1–3 sets of 8–12 repetitions at 50–70% 1RM, progressing gradually [

6].

Flexibility and balance: at least 2 days per week, integrated into warm-up or cool-down.

Mind–body or neuromotor components: Tai Chi, Pilates, or yoga may be added to improve postural control, breathing efficiency, and psychological regulation.

Progression principles:

Guided by tolerance, symptom monitoring, and adherence trends rather than fixed timelines [

4].

Adjust loads when predefined safety thresholds are reached, e.g., pain > 5 on a 0–10 scale, dyspnea ≥ 5 on the Borg scale, or excessive fatigue.

Record each modification to ensure transparency and allow replication.

Adapted sport context:

Apply the same FITT-VP logic to skill development and conditioning.

Respect sport-specific classification limits, safety rules, and environmental constraints.

Progression should integrate sport-specific drills, tactical or coordination tasks, and functional-ability-based workload adjustments.

Monitoring weekly training monotony and strain indices (e.g., load ratio < 1.5) can help prevent excessive fatigue, overuse injuries, and loss of motivation.

5.3 Monitoring and Supervision

Continuous monitoring is essential to ensure safety, fidelity, and sustained adherence, enabling early detection of overload or adverse responses. Session-RPE, HR or SpO₂ tracking, and wearable-based data provide objective feedback on internal and external load [

29]. Direct supervision is recommended for high-risk or unstable conditions (e.g., early cardiac or oncology rehabilitation). Remote or hybrid supervision is feasible for maintenance, home-based, or community settings, supported by tele-exercise platforms and digital logs. Routine documentation of attendance, session content, and adverse events improves transparency, allows benchmarking across programs, and enhances reproducibility.

In adapted-sport contexts, multidisciplinary supervision (clinician + exercise and sport specialist + coach) is essential to monitor health and performance indicators simultaneously. This interprofessional model ensures safety, optimizes motivation, and facilitates the transition from therapy to sustainable sport participation.

5.4 Implementation and Sustainability

Successful implementation requires embedding adapted exercise and sport programs within existing healthcare, educational, and community infrastructures, supported by clear governance, qualified professionals, and digital data systems. Sustainability depends on intersectoral partnerships, standardized procedures, and clear governance frameworks involving health systems, universities, and sport federations. The RE-AIM, TIDieR, and CERT frameworks should guide quality control, reporting, and long-term evaluation [

2,

14,

15,

16].

Key recommendations include:

Train qualified exercise professionals with clinical literacy, adapted-sport competence, and safety certification.

Promote interdisciplinary coordination among physicians, physiotherapists, psychologists, and behavioral scientists to ensure continuity of care.

Adopt digital and telemetric platforms for data collection, adherence tracking, and follow-up.

Engage adapted-sport organizations to extend exercise adherence through socially meaningful participation, competition pathways, and peer-support networks.

Include cost-effectiveness and feasibility assessments within implementation studies to support policy translation and funding allocation.

Building structured and bidirectional connections between healthcare providers, universities, community programs, and adapted-sport federations can transform time-limited rehabilitation into lifelong physical-activity participation, reinforcing autonomy and social inclusion.

5.5 Documentation and Reporting

Transparent documentation is the foundation of reproducibility and cross-study synthesis, supporting evidence accumulation and continuous quality improvement. Authors and practitioners should provide clear descriptions of:

Participant characteristics, eligibility, and risk stratification.

Detailed exercise type, dosage, intensity control, and supervision model.

Monitoring methods, criteria for progression, and decision thresholds (e.g., MCIDs, safety events, adherence ≥ 80 %).

Adherence rates, dropouts, injury or adverse-event data, and program fidelity.

Outcome domains, timing, analysis plan, and implementation metrics (reach, feasibility, cost).

Using RE-AIM, TIDieR, and CERT checklists ensures standardized reporting across clinical, community, and sport settings. These instruments provide complementary coverage: RE-AIM for external validity and scalability, TIDieR for intervention detail, and CERT for exercise-specific components.

Following these principles facilitates high-quality research and safe translation of adapted-exercise interventions into practice. Extending them to adapted sport further guarantees comparability in classification procedures, load management, safety surveillance, and inclusion indicators, bridging the gap between clinical exercise science and performance-oriented practice.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Although the proposed framework has not been formally validated across multiple sites, its primary aim is methodological rather than experimental to provide a structured, evidence-informed reference model for the design, implementation, and evaluation of adapted exercise and sport interventions. In this sense, the framework does not aim to prove immediate efficacy, but rather to establish a shared methodological foundation for harmonizing research and practice and for supporting replication, scalability, and policy translation. Its strength lies in synthesizing consolidated evidence from exercise physiology, clinical practice, and implementation science into a coherent operational structure that bridges methodological gaps between rehabilitation and inclusive sport participation.

Nonetheless, several lines of future development remain open for refinement and large-scale application. First, future research should focus on field-based validation studies to test feasibility, reliability, and inter-professional adoption across different healthcare systems and cultural contexts. Second, real-world implementation trials are needed to evaluate how effectively the framework enhances fidelity, cost-efficiency, and long-term adherence in practice. Third, adaptations tailored to sport-specific and competitive environments should be further developed, particularly regarding classification procedures, injury prevention, and performance monitoring. Finally, integrating digital monitoring tools, interoperable data systems, and AI- or machine-learning-based analytics could further enhance the scalability, personalization, and predictive precision of the framework.

Rather than a limitation, this stage of conceptualization represents a critical methodological step toward standardization, establishing a shared language and structure upon which future empirical research and professional guidelines can be built.

7. Conclusions

This methodological paper delivers a pragmatic and ready-to-implement framework for adapted exercise and adapted sport that standardizes how programs are designed (FITT-VP), supervised, monitored, and reported across clinical, community, and sport settings. Rather than remaining a purely conceptual proposal, the model is fully operationalized through: (i) modular workflow (screening → assessment → prescription → supervision/monitoring → outcome tracking → reporting/knowledge translation); (ii) core assessment batteries and decision thresholds; (iii) multidomain outcome sets that integrate functional, clinical, psychosocial, process, and implementation metrics; and (iv) aligned reporting standards (RE-AIM, TIDieR, CERT) to ensure fidelity, comparability, and scalability.

By providing ready-to-use tables, standardized indicators, and clear supervision/monitoring rules, the framework enables immediate adoption in clinical adapted-exercise programs, community initiatives, and adapted sport pathways. It supports day-to-day decision-making (progression, maintenance, or de-escalation), transparent documentation (adherence, fidelity, safety, and cost), and comparability of outcomes across sites and populations, thereby accelerating implementation, quality assurance, and policy translation.

The approach also bridges practice and research. Routine data captured with the framework (e.g., adherence, dose, adverse events, reach/adoption) constitute a built-in learning system that allows services to refine delivery, benchmark performance, and contribute to multisite evidence syntheses without redesigning their evaluation plans. In parallel, the exercise–sport continuum it articulates, from clinic-based adapted exercise to inclusive participation and adapted performance, offers a shared language for interprofessional teams, payers, and sport organizations to coordinate safe progression, social inclusion, and long-term engagement.

Finally, this framework functions as a deployable and scalable blueprint that equips practitioners with standardized tools, gives researchers reproducible methods and shared outcomes, and provides decision-makers with actionable implementation and cost metrics. Its systematic use can improve functional capacity and quality of life, enhance program safety and fidelity, and expand equitable access to adapted exercise and sport across health systems and communities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G. and F.F.; methodology, G.G., F.F. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G., F.F., and S.C.; writing—review and editing, G.G., F.F., and S.C.; supervision, G.G. and S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., Boyd, K. A., Craig, N., French, D. P., McIntosh, E., Petticrew, M., Rycroft-Malone, J., White, M., & Moore, L. (2024). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 154, 104705. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., Altman, D. G., Barbour, V., Macdonald, H., Johnston, M., Lamb, S. E., Dixon-Woods, M., McCulloch, P., Wyatt, J. C., Chan, A. W., & Michie, S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ, 348, g1687. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M., Katikireddi, S. V., Hoffmann, T., Armstrong, R., Waters, E., & Craig, P. (2018). TIDieR-PHP: A reporting guideline for population health and policy interventions. BMJ, 361, k1079. [CrossRef]

- Ehrman, J. K., Gordon, P. M., Visich, P., & Keteyian, S. J. (Eds.). (2023). Clinical exercise physiology: exercise management for chronic diseases and special populations. Human kinetics.

- American College of Sports Medicine. (2025). ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (12th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Jacobs, P. L. (Ed.). (2018). NSCA’s Essentials of Training Special Populations. Human Kinetics.

- Garber, C. E., Blissmer, B., Deschenes, M. R., Franklin, B. A., Lamonte, M. J., Lee, I. M., ... & Swain, D. P. (2011). Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 43(7), 1334–1359. [CrossRef]

- Riebe, D., Franklin, B. A., Thompson, P. D., Garber, C. E., Whitfield, G. P., Magal, M., & Pescatello, L. S. (2015). Updating ACSM’s recommendations for exercise preparticipation health screening. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 47(11), 2473–2479. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B. K., & Saltin, B. (2015). Exercise as medicine—Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 25(S3), 1–72. [CrossRef]

- Cormie, N., Zopf, E. M., Zhang, X., & Schmitz, K. H. (2017). The impact of exercise on cancer mortality, recurrence, and treatment-related adverse effects. Epidemiologic reviews, 39(1), 71-92. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, K. H., Campbell, A., & Schwartz, A. L. (2024). ACSM’s essentials of exercise oncology. Wolters Kluwer.

- Spruit, M. A., Singh, S. J., Garvey, C., ZuWallack, R., Nici, L., Rochester, C., ... & Wouters, E. F. (2013). An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 188(8), e13–e64. [CrossRef]

- Rochester, C. L., Alison, J. A., Carlin, B., Jenkins, A. R., Cox, N. S., Bauldoff, G., … Holland, A. E. (2023). Pulmonary rehabilitation for adults with chronic respiratory disease: An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 208(4), e7–e26. [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R. E., Harden, S. M., Gaglio, B., Rabin, B., Smith, M. L., Porter, G. C., Ory, M. G., & Estabrooks, P. A. (2019). RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: Adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 64. [CrossRef]

- Harden, S. M., Galaviz, K. I., & Estabrooks, P. A. (2024). Expanding methods to address RE-AIM metrics in hybrid effectiveness–implementation studies. Implementation Science Communications, 5, 123. [CrossRef]

- Slade, S. C., Dionne, C. E., Underwood, M., & Buchbinder, R. (2016). Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT): Explanation and elaboration statement. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(23), 1428–1437. [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D. E. R., Jamnik, V. K., Bredin, S. S. D., Shephard, R. J., & Gledhill, N. (2023). The 2023 Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PAR-Q+) and electronic Physical Activity Readiness Medical Examination (ePARmed-X+). Health & Fitness Journal of Canada, 16(1), 3–23. [CrossRef]

- Cavero-Redondo, I., Saz-Lara, A., Bizzozero-Peroni, B., Nunez-Martinez, L., Diaz-Goni, V., Calero-Paniagua, I., ... & Pascual-Morena, C. (2024). Accuracy of the 6-minute walk test for assessing functional capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and other chronic cardiac pathologies: Results of the ExIC-FEp trial and a meta-analysis. Sports Medicine-Open, 10(1), 74. [CrossRef]

- Böttinger, M. J., Mellone, S., Klenk, J., Jansen, C. P., Stefanakis, M., Litz, E., ... & Gordt-Oesterwind, K. (2025). A Smartphone-Based Timed Up and Go Test Self-Assessment for Older Adults: Validity and Reliability Study. JMIR aging, 8(1), e67322. [CrossRef]

- Eusepi, D., Pellicciari, L., Ugolini, A., Graziani, L., Coppari, A., Carlizza, A., ... & Piscitelli, D. (2025). Reliability of the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB): a systematic review with meta-analysis. European geriatric medicine, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R. W. (2019). Grip strength: An indispensable biomarker for older adults. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 14, 1681–1691. [CrossRef]

- Rothmund, M., Pilz, M. J., Egeter, N., Lidington, E., Piccinin, C., Arraras, J. I., ... & Giesinger, J. M. (2024). Comparing the contents of patient-reported outcome measures for fatigue: EORTC CAT core, EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-FA12, FACIT, PRO-CTCAE, PROMIS, brief fatigue inventory, multidimensional fatigue inventory, and piper fatigue scale. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 22(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Cella, D. F., Tulsky, D. S., Gray, G., Sarafian, B., Linn, E., Bonomi, A., ... & Brannon, J. (1993). The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 11(3), 570–579. [CrossRef]

- Cocks, K., Wells, J. R., Johnson, C., Schmidt, H., Koller, M., Oerlemans, S., ... & European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Group. (2023). Content validity of the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30 for use in cancer. European journal of cancer, 178, 128-138. [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health.

- Asonitou, K., Yiannaki, S., & Koutsouki, D. (2024). Exercise is medicine through time: Prescription of adapted physical activity in treatment and rehabilitation. In New Horizons of Exercise Medicine. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Borg, G. (1998). Borg’s perceived exertion and pain scales. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Chamradova, K., Batalik, L., Winnige, P., Dosbaba, F., Hartman, M., Batalikova, K., ... & Su, J. J. (2024). Effects of home-based exercise with telehealth guidance in lymphoma cancer survivors entering cardio-oncology rehabilitation: rationale and design of the tele@ home study. Cardio-Oncology, 10(1), 46. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., Huang, H., Zhang, Y., He, N., Shen, M., & Li, H. (2024). The effects of telerehabilitation on physiological function and disease symptoms for patients with chronic respiratory disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulmonary Medicine, 24, 305. [CrossRef]

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. [CrossRef]

- Guillon, M., Rochaix, L., & Dupont, J.-C. K. (2018). Cost-effectiveness of interventions based on physical activity in the treatment of chronic conditions: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 34(5), 481–497. [CrossRef]

- Chase, P. J., Owen, C. M., Bantham, A., Stoutenberg, M., Ajibewa, T., Barclay, J., ... & Whitsel, L. P. (2025). A review of the cost-effectiveness of supervised exercise therapy for adults with chronic conditions in the United States. Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine, 10(3), e000313. [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C. A. C., Mokkink, L. B., Bouter, L. M., Alonso, J., Patrick, D. L., de Vet, H. C. W., & Terwee, C. B. (2018). COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Quality of Life Research, 27(5), 1147–1157. [CrossRef]

- Pepe, I., Petrelli, A., Fischetti, F., Minoia, C., Morsanuto, S., Talaba, L., Cataldi, S., & Greco, G. (2025). Nonregular Physical Activity and Handgrip Strength as Indicators of Fatigue and Psychological Distress in Cancer Survivors. Current Oncology, 32(5), 289. [CrossRef]

- Cataldi, S., Greco, G., Mauro, M., & Fischetti, F. (2021). Effect of exercise on cancer-related fatigue: A systematic review. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 16(3), 476-492. [CrossRef]

- Fischetti, F., Greco, G., Cataldi, S., Minoia, C., Loseto, G., & Guarini, A. (2019). Effects of Physical Exercise Intervention on Psychological and Physical Fitness in Lymphoma Patients. Medicina, 55(7), 379. [CrossRef]

- Hakami, F. H. A., Ayoub, J. E. M., Abumerai, Z. Y. H., Hadi, E. N., Bashir, H. M., Omeesh, O. A. M., ... & Iskander, I. O. A. (2024). Physical activity/exercise and diabetes: a review statement of the American Diabetes Association. International Journal of Medicine in Developing Countries, 8(6), 1505-1505. [CrossRef]

- Mi, M. Y., Perry, A. S., Krishnan, V., & Nayor, M. (2025). Epidemiology and Cardiovascular Benefits of Physical Activity and Exercise. Circulation Research, 137(2), 120-138. [CrossRef]

- Poli, L., Greco, G., Cataldi, S., Ciccone, M.M., De Giosa, A., Fischetti, F. (2024). Multicomponent versus aerobic exercise intervention: Effects on hemodynamic, physical fitness and quality of life in adult and elderly cardiovascular disease patients: A randomized controlled study. Heliyon, 10(16), e36200. [CrossRef]

- Poli, L., Petrelli, A., Fischetti, F., Morsanuto, S., Talaba, L., Cataldi, S., & Greco, G. (2025a). The Effects of Multicomponent Training on Clinical, Functional, and Psychological Outcomes in Cardiovascular Disease: A Narrative Review. Medicina, 61(5), 822. [CrossRef]

- Poli, L., Mazić, S., Ciccone, M.M., Cataldi, S., Fischetti, F., Greco, G. (2025b). A 10-Week Multicomponent Outdoor Exercise Program Improves Hemodynamic Parameters and Physical Fitness in Cardiovascular Disease Adult and Elderly Patients. Sport Sciences for Health, 21, 239-249. [CrossRef]

- Grigoletto, A., Mauro, M., Oppio, A., Greco, G., Fischetti, F., Cataldi, S., & Toselli, S. (2022). Effects of Nordic Walking Training on Anthropometric, Body Composition and Functional Parameters in the Middle-Aged Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7433. [CrossRef]

- Abou, L., Murphy, T., Truong, E., & Peters, J. (2025). Meeting physical activity guidelines for persons with multiple sclerosis reduces fatigue severity and impact: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Physical Therapy, 105(6), pzaf046. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-García, P., Cavero-Redondo, I., De Arenas-Arroyo, S. N., Guzmán-Pavón, M. J., Priego-Jiménez, S., & Álvarez-Bueno, C. (2024). Effects of physical exercise interventions on balance, postural stability and general mobility in Parkinson’s disease: a network meta-analysis. Journal of rehabilitation medicine, 56, 10329. [CrossRef]

- Martin Ginis, K. A., Ma, J. K., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., & Rimmer, J. H. (2016). A systematic review of review articles addressing factors related to physical activity participation among children and adults with physical disabilities. Health Psychology Review, 10(4), 478–494. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Henley, T., Schiaffino, M., Wiese, J., Sachs, D., Migliaccio, J., & Huh-Yoo, J. (2021). Older adults’ perceptions of community-based telehealth wellness programs: A qualitative study. Informatics for Health and Social Care, 47(4), 361-372. [CrossRef]

- de Vries, H., Kremers, S. P. J., & Lippke, S. (2018). Health Education and Health Promotion: Key Concepts and Exemplary Evidence to Support Them. In Principles and Concepts of Behavioral Medicine (pp. 489–532). Springer. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (2023). Global policy and guidelines on physical activity. https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/physical-activity/global-policy-and-guidelines-on-physical-activity.

- Ramsden, R., Hayman, R., Potrac, P., & Hettinga, F. J. (2023). Sport participation for people with disabilities: exploring the potential of reverse integration and inclusion through wheelchair basketball. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(3), 2491. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/3/2491.

- Sherrill, C. (2024). Adapted Physical Activity Pedagogy: Principles, Practices, and Creativity. In Adapted Physical Activity (pp. 13–19). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-4-431-68272-1_2.

- Shao, J., Cui, Z., & Bao, Y. (2025). Adaptive sports programs as catalysts for social inclusion and cognitive flexibility in inclusive physical education: The mediating roles of emotional resilience and empathy. BMC Psychology, 13, Article 770. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Conceptual and Methodological Framework for Adapted Exercise and Sport Interventions. Note. Conceptual and methodological framework for designing, implementing, and evaluating adapted exercise and sport interventions. The model integrates six interconnected phases, from risk screening to evaluation and reporting, guided by FITT-VP principles, safety management, and implementation metrics (RE-AIM, TIDieR, CERT). Abbreviations: 6MWT = Six-Minute Walk Test; CERT = Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template; FACIT-F = Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue; FACT-G = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; FITT-VP = Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Volume, and Progression; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HR = Heart Rate; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; QoL = Quality of Life; RE-AIM = Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance; RPE = Rating of Perceived Exertion; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery; TIDieR = Template for Intervention Description and Replication; TUG = Timed Up and Go test

Figure 1.

Conceptual and Methodological Framework for Adapted Exercise and Sport Interventions. Note. Conceptual and methodological framework for designing, implementing, and evaluating adapted exercise and sport interventions. The model integrates six interconnected phases, from risk screening to evaluation and reporting, guided by FITT-VP principles, safety management, and implementation metrics (RE-AIM, TIDieR, CERT). Abbreviations: 6MWT = Six-Minute Walk Test; CERT = Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template; FACIT-F = Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue; FACT-G = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; FITT-VP = Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Volume, and Progression; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HR = Heart Rate; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; QoL = Quality of Life; RE-AIM = Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance; RPE = Rating of Perceived Exertion; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery; TIDieR = Template for Intervention Description and Replication; TUG = Timed Up and Go test

Figure 2.

Modular Evaluation Cycle for Adapted Exercise and Sport Programs. Note. The diagram illustrates four sequential modules, i.e. baseline assessment, ongoing monitoring, periodic evaluation and feedback, and decision thresholds, connected by a continuous feedback loop incorporating MCIDs, safety triggers, and adherence targets for individualized program adjustment. Each module integrates functional, clinical, and psychosocial outcomes, along with process and implementation metrics (e.g., adherence, fidelity, feasibility, safety), to guide decisions on progression, maintenance, or de-escalation. This model supports dynamic evaluation and enhances precision, safety, and scalability across clinical, community, and adapted sport contexts. The same modular logic applies to adapted sport, guiding transitions from clinic-based exercise to structured physical activity and inclusive participation. Abbreviations: 6MWT = Six-Minute Walk Test; EORTC QLQ-C30 = European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire – Core 30; FACT-G = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; FACIT-F = Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HR = Heart Rate; MCIDs = Minimal Clinically Important Differences; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; QoL = Quality of Life; RPE = Rating of Perceived Exertion; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery; TUG = Timed Up and Go test.

Figure 2.

Modular Evaluation Cycle for Adapted Exercise and Sport Programs. Note. The diagram illustrates four sequential modules, i.e. baseline assessment, ongoing monitoring, periodic evaluation and feedback, and decision thresholds, connected by a continuous feedback loop incorporating MCIDs, safety triggers, and adherence targets for individualized program adjustment. Each module integrates functional, clinical, and psychosocial outcomes, along with process and implementation metrics (e.g., adherence, fidelity, feasibility, safety), to guide decisions on progression, maintenance, or de-escalation. This model supports dynamic evaluation and enhances precision, safety, and scalability across clinical, community, and adapted sport contexts. The same modular logic applies to adapted sport, guiding transitions from clinic-based exercise to structured physical activity and inclusive participation. Abbreviations: 6MWT = Six-Minute Walk Test; EORTC QLQ-C30 = European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire – Core 30; FACT-G = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; FACIT-F = Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HR = Heart Rate; MCIDs = Minimal Clinically Important Differences; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; QoL = Quality of Life; RPE = Rating of Perceived Exertion; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery; TUG = Timed Up and Go test.

Table 1.

Comparative summary of reporting and implementation frameworks used in the proposed model (RE-AIM vs. TIDieR vs. CERT).

Table 1.

Comparative summary of reporting and implementation frameworks used in the proposed model (RE-AIM vs. TIDieR vs. CERT).

| Model |

Primary purpose |

Scope / level |

Core domains / items |

Expected outputs |

Strengths for this framework |

Limitations / cautions |

| RE-AIM |

Planning and multi-dimensional evaluation of real-world impact and scalability |

Program/service; setting; system (clinical, community, sport) |

Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance |

Adoption/implementation metrics; impact and sustainability evidence |

Aligns with pragmatic goals (scalability, equity, cost, adaptations over time); captures community and sport-organization adoption, federation engagement, and inclusion metrics |

Does not specify how to describe the intervention; requires clear operationalization of indicators |

| TIDieR |

Complete and replicable reporting of any intervention |

Intervention/protocol (description-focused) |

12 items: name; rationale; materials; procedures; provider; mode; setting; schedule/dose; tailoring; modifications; fidelity (planned/actual) |

Standardized description enabling replication and peer review |

Reduces heterogeneity in reporting; integrates well with FITT-VP and CERT; widely adopted for exercise, rehabilitation, and behavioral interventions; useful for describing adapted sport programs, equipment adjustments, and inclusive delivery methods |

Not an evaluation or adoption model; use with RE-AIM for implementation outcomes |

| CERT |

Exercise-specific reporting (prescription, progression, supervision, adherence) |

Exercise / physical-activity protocol (clinical → community → sport) |

16 items: equipment; provider qualifications; delivery & supervision; location; dosage; tailoring/progression; adherence & motivation; safety/modifications |

Reproducible, transferable exercise and sport protocols |

Details the how of exercise prescription and progression; ideal for the prescription–supervision–monitoring chain; extends to adapted sport classification, training-load management, and injury prevention reporting |

Does not cover adoption/scalability; should be paired with RE-AIM and TIDieR for full implementation coverage |

Table 2.

Integration of models across the six components of the framework.

Table 2.

Integration of models across the six components of the framework.

| Framework component |

RE-AIM |

TIDieR |

CERT |

| 1) Screening & risk stratification |

○ |

○ |

○ |

| 2) Functional & psychosocial assessment |

○ |

○ |

○ |

| 3) Individualized prescription |

— |

○ |

✓ |

| 4) Supervision & monitoring |

○ |

○ |

✓ |

| 5) Outcome Tracking & Feedback |

✓ |

○ |

○ |

| 6) Reporting & knowledge translation |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

Table 3.

Core outcome, process, and implementation indicators for adapted exercise and sport interventions.

Table 3.

Core outcome, process, and implementation indicators for adapted exercise and sport interventions.

| Domain |

Indicators |

Measurement tools / examples |

Purpose / rationale |

| Functional outcomes |

Aerobic capacity, muscle strength, balance, mobility, coordination, sport skills |

6MWT; Handgrip Strength; 30-s Chair Stand; SPPB; TUG; sport-specific performance tests: Agility T-test; Modified Yo-Yo (adapted); wheelchair propulsion; throwing accuracy |

Quantify physiological and sport-related adaptations |

| Clinical outcomes |

Vitals, biomarkers, treatment tolerance, symptom burden |

BP, HR, glucose, lipid profile, treatment-related AEs |

Monitor safety and therapeutic response |

| Psychosocial outcomes |

Fatigue, mood, QoL, participation, self-efficacy, autonomy/motivation, social connectedness |

FACIT-F; FACT-G; HADS; EORTC QLQ-C30; EQ-5D; BREQ-3; WHOQOL-BREF; Participation Scale |

Evaluate mental health, inclusion, and well-being |

| Process indicators |

Adherence, fidelity, dose intensity, session attendance, training-load management & recovery |

Training logs; RPE tracking; digital monitoring; coach checklists; session-RPE; training monotony/strain; Hooper Index; sleep-quality log |

Assess intervention quality, compliance, progression, and recovery balance |

| Implementation metrics |

Reach, adoption, feasibility, sustainability, accessibility, cost, classification status, equipment adaptation, facility suitability |

RE-AIM matrix; cost-effectiveness; staff workload; classification records; equipment-fit checklist; accessibility audit |

Evaluate scalability, equity, and sustainability of exercise and sport programs |

| Safety & injury surveillance |

Adverse events, symptom thresholds, injuries, dropout causes |

Session reports; safety audits; OSIICS injury logs; readiness/return-to-play checklist; RED-S screen |

Ensure safety and manage sport-related risks |

| Follow-up evaluation |

Maintenance of effects; relapse or progression; retention in sport; transition outcomes (clinic → club → competition) |

Re-testing at 3, 6 and 12 months; follow-up interviews; participation logs |

Measure durability of adaptations, adherence, and sustained participation |

Table 4.

Recommended assessment and outcome measures by domain and setting

Table 4.

Recommended assessment and outcome measures by domain and setting

| Domain |

Outcome / Indicator |

Recommended Tools or Tests |

Primary Setting(s) |

Purpose / Rationale |

| Functional |

Aerobic capacity |

6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT); Cycle ergometer submaximal test (e.g., Åstrand or YMCA protocol) |

Clinical /

Community |

Quantify endurance and mobility improvements |

| Muscular strength |

Handgrip strength; 30-s Chair Stand; 1-RM submaximal |

Clinical /

Community |

Evaluate upper- and lower-body strength adaptations |

| Balance / mobility |

Timed Up and Go (TUG); Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) |

Clinical /

Community |

Assess fall-risk reduction and functional autonomy |

| Gait/balance in neurological disorders |

10-m walk test; Berg Balance Scale |

Clinical /

Community |

Monitor mobility, balance, and fall-risk |

| Sport-specific functional skills |

Agility T-test; Modified Yo-Yo test; sport classification tests (e.g., wheelchair propulsion, throwing distance) |

Adapted Sport / Community |

Assess sport-related function, classification readiness, and performance progression |

| Clinical |

Vitals & cardiometabolic profile |

Resting BP & HR; glucose; lipids; oxygen saturation (SpO₂) |

Clinical |

Monitor physiological adaptations and safety |

| Treatment tolerance and symptom burden |

RPE scale; Borg dyspnea scale; symptom log |

Clinical |

Adjust intensity and detect overexertion or toxicity |

| Psychosocial |

Fatigue |

FACIT-F questionnaire |

Clinical /

Community |

Measure perceived fatigue and recovery status |

| Mood / anxiety |

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) |

Clinical /

Community |

Monitor emotional well-being and motivation |

| Quality of life / self-efficacy |

FACT-G; EORTC QLQ-C30; EQ-5D; Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale |

Clinical /

Community |

Capture perceived health status and participation |

| Process |

Adherence and fidelity |

Session attendance; training logs; wearable tracking; training-load monitoring |

All settings |

Evaluate program fidelity, engagement, and load-management consistency |

| Dose intensity and session load |

Session-RPE; HR monitoring; workload index |

All settings |

Quantify internal load and progression consistency |

| Implementation |

Feasibility, reach, and adoption |

RE-AIM indicators; participant flow; recruitment rate; classification records |

Community / Public health |

Assess scalability, population reach, and equity in adapted sport contexts |

| Cost and sustainability |

Resource use; staff time; cost-effectiveness analysis |

Clinical /

Community |

Support long-term integration and policy translation |

| Safety & injury surveillance |

Adverse events, injuries / illness, risk monitoring |

AE log; safety audit checklist; injury surveillance log (OSIICS) |

All settings |

Ensure safety, manage injury risk, and guide corrective actions |

| Follow-up |

Maintenance of benefits and relapse monitoring |

Reassessment at 3, 6, and 12 months; adherence survey |

Clinical /

Community |

Evaluate durability of training effects and compliance |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).