Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

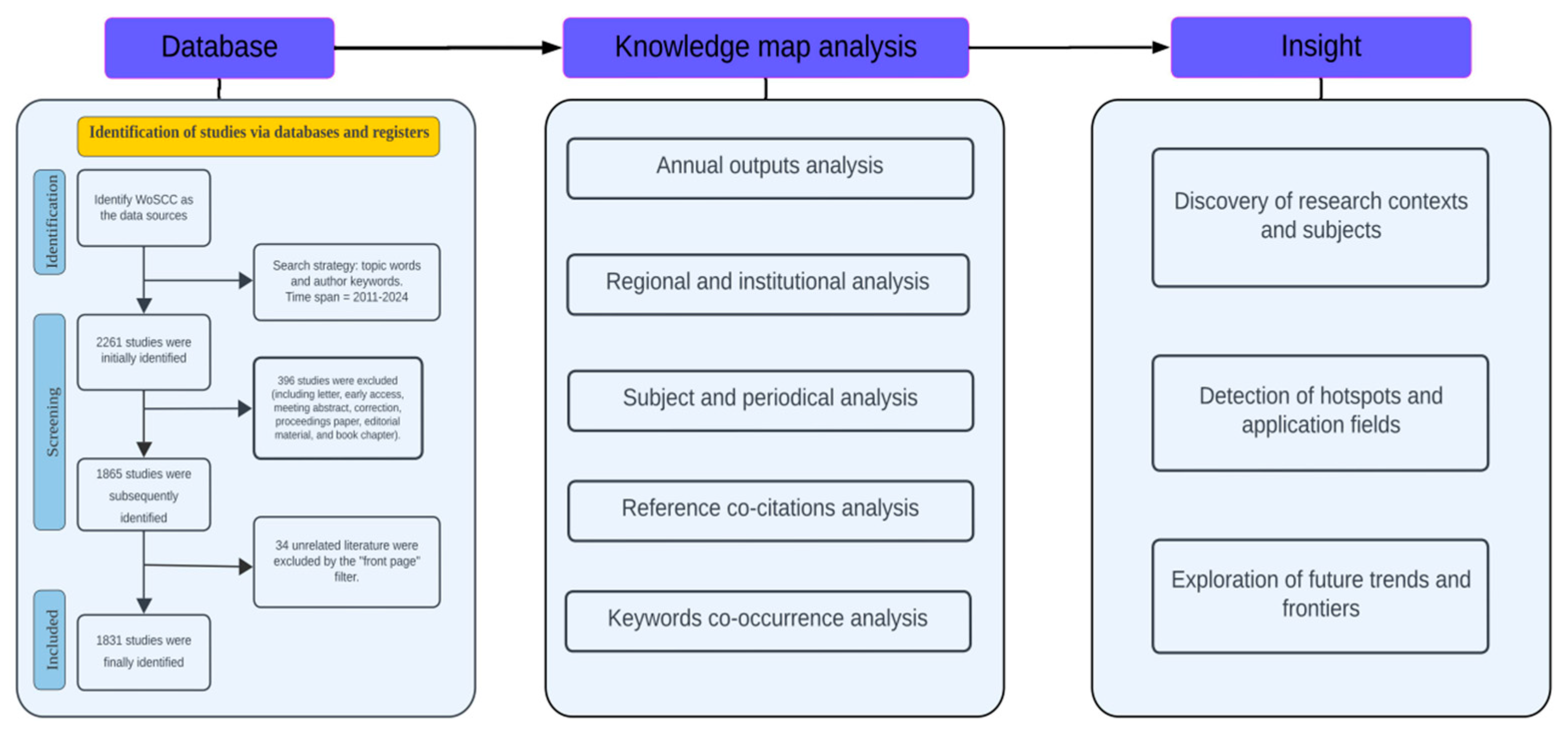

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Acquisition and Search Strategy

2.2. Research Methods and Analysis Tools

3. Results and Discussions

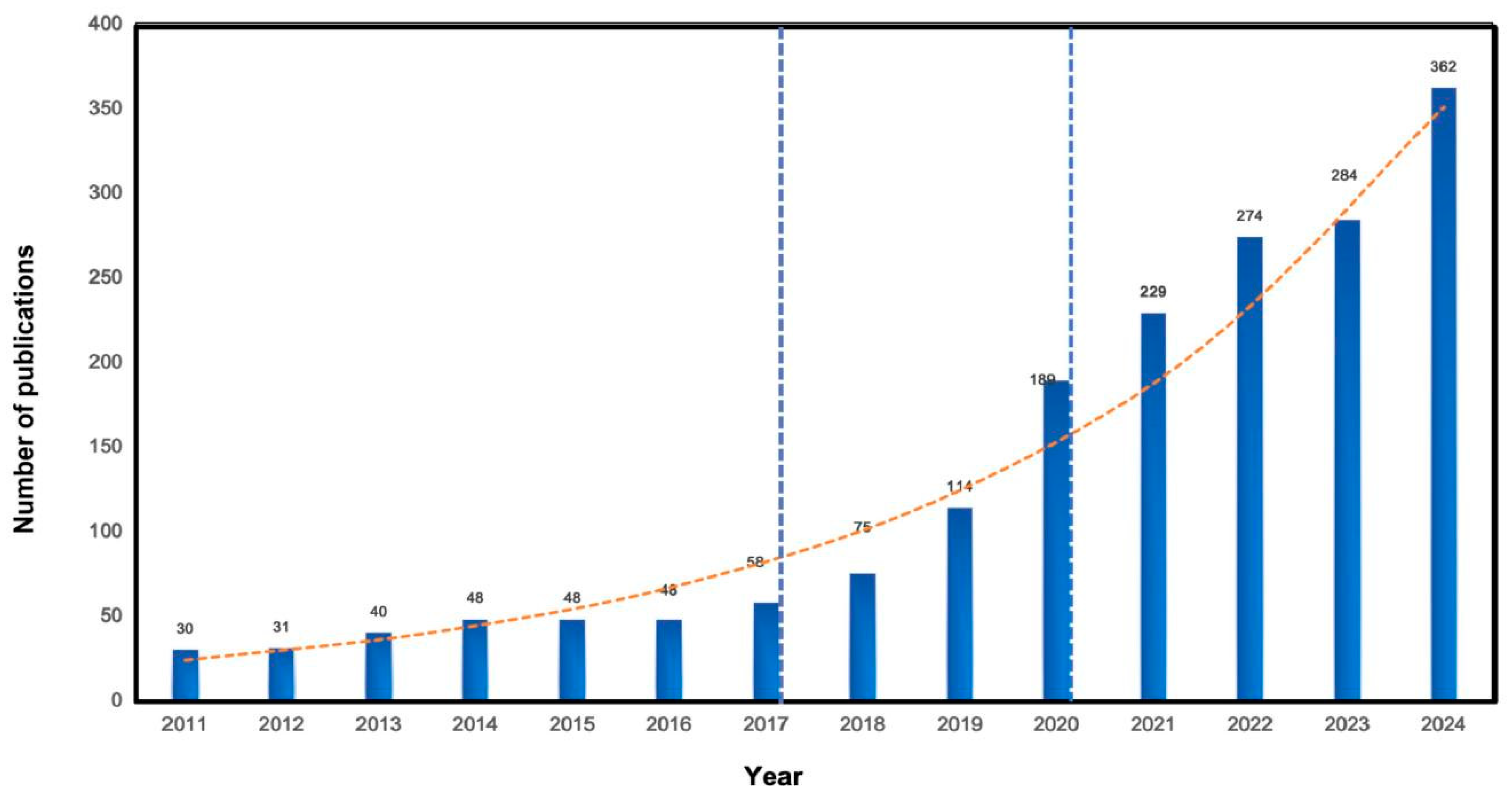

3.1. Annual Outputs Analysis

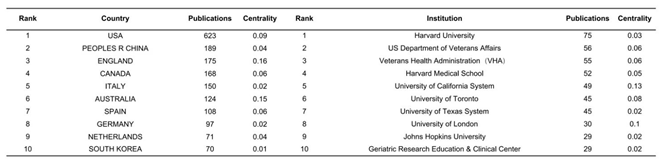

3.2. Regional and Institutional Analysis

|

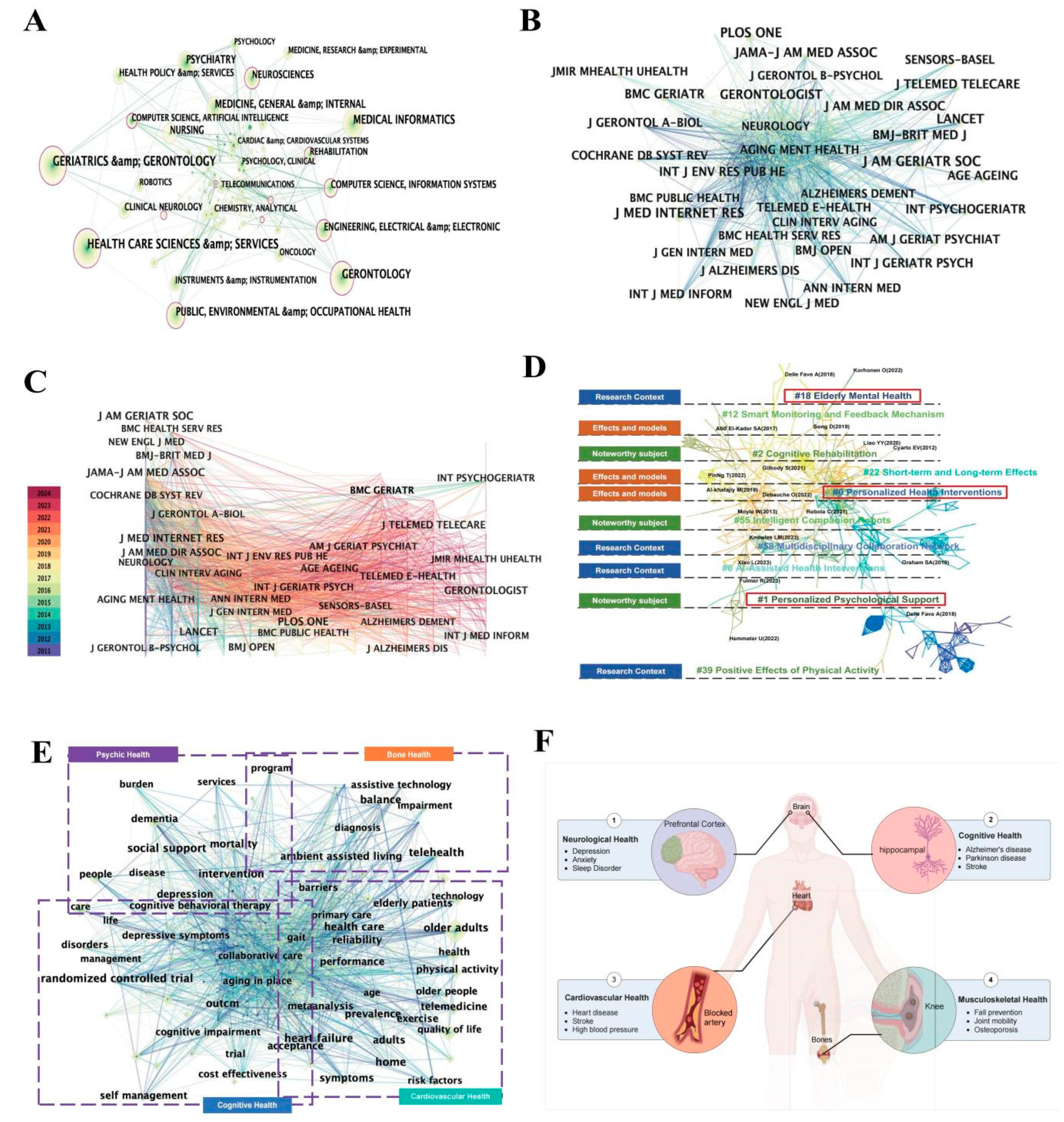

3.3. Subject and Periodical Analysis

3.4. Analysis of Co-Cited References

3.5. Analysis of Co-Occurrence Keywords

4. Research Hot Spots and Application Fields Analyses

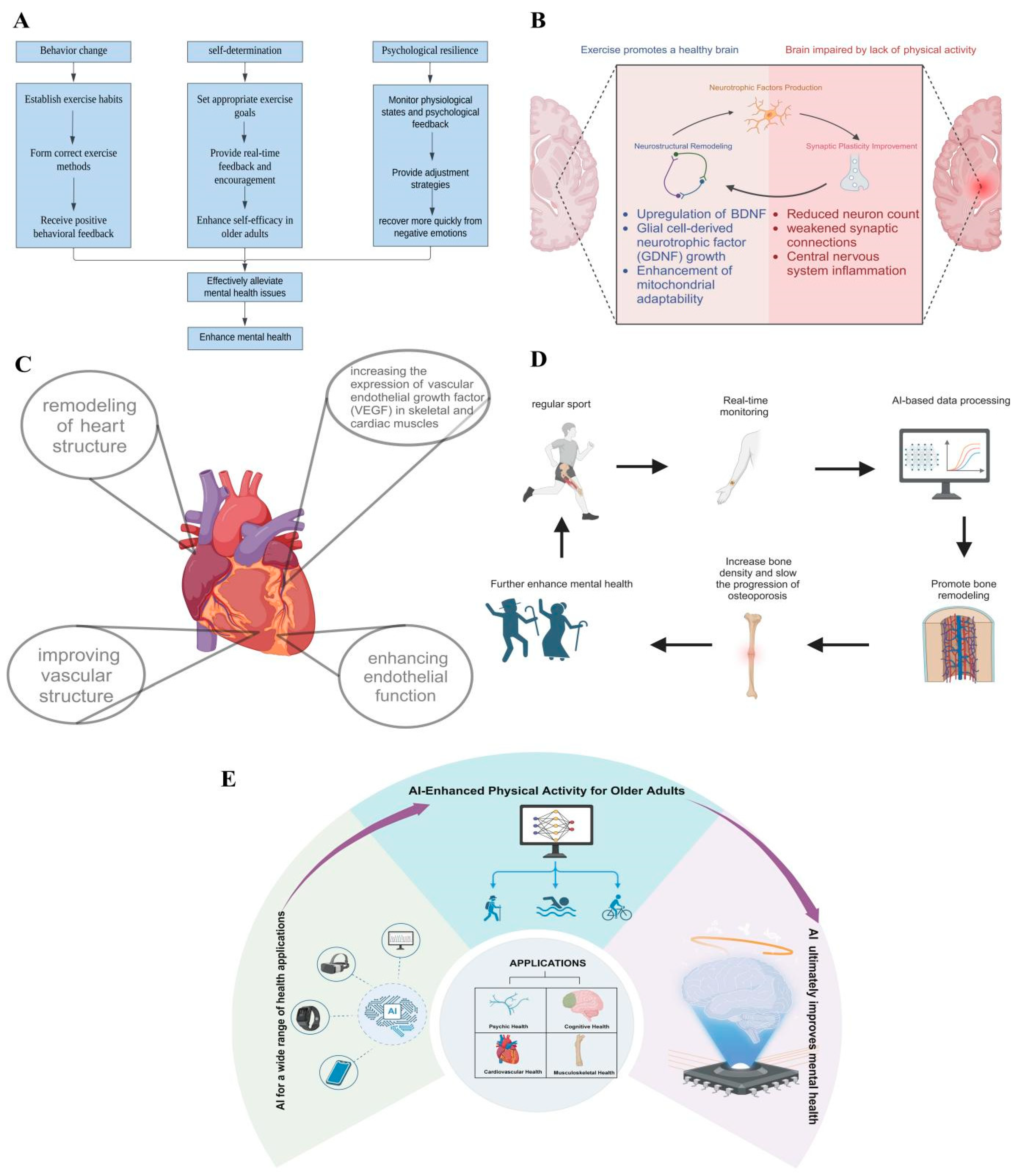

4.1. Psychic Health

4.2. Cognitive Health

4.3. Cardiovascular Health

4.4. Musculoskeletal Health

5. Conclusion and Future Perspective

5.1. Conclusion

5.2. Future Perspectives

5.3. Strength and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aarsland, D., Batzu, L., Halliday, G. M., Geurtsen, G. J., Ballard, C., Ray Chaudhuri, K., & Weintraub, D. (2021). Parkinson disease-associated cognitive impairment. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 7(1), 47. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, V., Fan, K., Snitz, B. E., Ganguli, M., DeKosky, S., Lopez, O. L., Feingold, E., & Kamboh, M. I. (2021). Genome-wide meta-analysis of age-related cognitive decline in population-based older individuals. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 17(S2), e058723. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, N., & Kim, K. (2020). Can Active Aerobic Exercise Reduce the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Prehypertensive Elderly Women by Improving HDL Cholesterol and Inflammatory Markers? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17. [CrossRef]

- Alexandrino-Silva, C., Ribeiz, S. R., Frigerio, M. B., Bassolli, L., Alves, T. F., Busatto, G., & Bottino, C. (2019). Prevention of depression and anxiety in community-dwelling older adults: The role of physical activity. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo), 46(1), 14–20. [CrossRef]

- Al-khafajiy, M., Baker, T., Chalmers, C., Asim, M., Kolivand, H., Fahim, M., & Waraich, A. (2019). Remote health monitoring of elderly through wearable sensors. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 78(17), 24681–24706. [CrossRef]

- Babić, D., Kamenečki, G., Milošević, M., Završnik, J., & Železnik, D. (2022). Functional Independence and Social Support as Mediators in the Maintenance of Mental Health among Elderly Persons with Chronic Diseases. Collegium Antropologicum, 46(1), 37–45. [CrossRef]

- Bangen, K. J., Delano-Wood, L., Wierenga, C. E., McCauley, A., Jeste, D. V., Salmon, D. P., & Bondi, M. W. (2010). Associations between stroke risk and cognition in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease with and without depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(2), 175–182. [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, G., Bellafiore, M., Alesi, M., Paoli, A., Bianco, A., & Palma, A. (2016). Effects of an adapted physical activity program on psychophysical health in elderly women. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 11, 1009–1015. [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, M. R., Hulteen, R. M., Ruissen, G. R., Liu, Y., Rhodes, R. E., Wierts, C. M., Waldhauser, K. J., Harden, S. H., & Puterman, E. (2021). Online-Delivered Group and Personal Exercise Programs to Support Low Active Older Adults’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(7), e30709. [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M., Furlini, G., Zati, A., & Mauro, G. letizia. (2018). The Effectiveness of Physical Exercise on Bone Density in Osteoporotic Patients. BioMed Research International, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Benitez-Lugo, M.-L., Suárez-Serrano, C., Galvao-Carmona, A., Vazquez-Marrufo, M., & Chamorro-Moriana, G. (2022). Effectiveness of feedback-based technology on physical and cognitive abilities in the elderly. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 14. [CrossRef]

- Bleijenberg, N., Drubbel, I., Neslo, R. Ej., Schuurmans, M. J., Ten Dam, V. H., Numans, M. E., De Wit, G. A., & De Wit, N. J. (2017). Cost-Effectiveness of a Proactive Primary Care Program for Frail Older People: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18(12), 1029-1036.e3. [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., & Lubet, A. (2015). Global Population Aging: Facts, Challenges, Solutions & Perspectives. Daedalus, 144(2), 80–92. [CrossRef]

- Bourouis, A., Feham, M., & Bouchachia, A. (2011). Ubiquitous Mobile Health Monitoring System for Elderly (UMHMSE). International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology, 3(3), 74–82. [CrossRef]

- Breteler, M. M. B. (2000). Vascular Involvement in Cognitive Decline and Dementia: Epidemiologic Evidence from the Rotterdam Study and the Rotterdam Scan Study. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 903(1), 457–465. [CrossRef]

- Byass, P. (2008). Towards a global agenda on ageing. Global Health Action, 1, 10.3402/gha.v1i0.1908. [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, L. F., Chàfer, M., & Mata, É. (2020). Comparative Analysis of Web of Science and Scopus on the Energy Efficiency and Climate Impact of Buildings. Energies, 13(2), 409. [CrossRef]

- Cascajares, M., Alcayde, A., Salmerón-Manzano, E., & Manzano-Agugliaro, F. (2021). The Bibliometric Literature on Scopus and WoS: The Medicine and Environmental Sciences Categories as Case of Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5851. [CrossRef]

- Chadegani, A. A., Salehi, H., Yunus, M. M., Farhadi, H., Fooladi, M., Farhadi, M., & Ebrahim, N. A. (2013). A Comparison between Two Main Academic Literature Collections: Web of Science and Scopus Databases. Asian Social Science, 9(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. (2006). CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(3), 359–377. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Guo, B., Ma, G., & Cao, H. (2024). Sensory nerve regulation of bone homeostasis: Emerging therapeutic opportunities for bone-related diseases. Ageing Research Reviews, 99, 102372. [CrossRef]

- Civieri, G., Abohashem, S., Grewal, S. S., Aldosoky, W., Qamar, I., Hanlon, E., Choi, K. W., Shin, L. M., Rosovsky, R. P., Bollepalli, S. C., Lau, H. C., Armoundas, A. A., Seligowski, A. V., Turgeon, S. M., Pitman, R. K., Tona, F., Wasfy, J. H., Smoller, J. W., Iliceto, S., … Tawakol, A. (2024). Anxiety and Depression Associated With Increased Cardiovascular Disease Risk Through Accelerated Development of Risk Factors. JACC: Advances, 3(9), 101208. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F. G. D. M., Gobbi, S., Andreatto, C. A. A., Corazza, D. I., Pedroso, R. V., & Santos-Galduróz, R. F. (2013). Physical exercise modulates peripheral levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF): A systematic review of experimental studies in the elderly. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 56(1), 10–15. [CrossRef]

- Cortellessa, G., Benedictis, R. D., Fracasso, F., Orlandini, A., Umbrico, A., & Cesta, A. (2021). AI and robotics to help older adults: Revisiting projects in search of lessons learned. Paladyn, Journal of Behavioral Robotics, 12(1), 356–378. [CrossRef]

- Cyarto, E. V., Lautenschlager, N. T., Desmond, P. M., Ames, D., Szoeke, C., Salvado, O., Sharman, M. J., Ellis, K. A., Phal, P. M., Masters, C. L., Rowe, C. C., Martins, R. N., & Cox, K. L. (2012). Protocol for a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of physical activity on delaying the progression of white matter changes on MRI in older adults with memory complaints and mild cognitive impairment: The AIBL Active trial. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 167. [CrossRef]

- Daly, R., Gianoudis, J., Kersh, M., Bailey, C. A., Ebeling, P., Krug, R., Nowson, C., Hill, K., & Sanders, K. (2020). Effects of a 12-Month Supervised, Community-Based, Multimodal Exercise Program Followed by a 6-Month Research-to-Practice Transition on Bone Mineral Density, Trabecular Microarchitecture, and Physical Function in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 35. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L. da S. S. C. B., Souza, E. C., Rodrigues, R. A. S., Fett, C. A., & Piva, A. B. (2019). The effects of physical activity on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in elderly people living in the community. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 41, 36–42. [CrossRef]

- Debauche, O., Penka, J. B. N., Mahmoudi, S., Lessage, X., Hani, M., Manneback, P., Lufuluabu, U. K., Bert, N., Messaoudi, D., & Guttadauria, A. (2022). RAMi: A New Real-Time Internet of Medical Things Architecture for Elderly Patient Monitoring. Inf., 13. [CrossRef]

- Dell’Acqua, P., Klompstra, L. V., Jaarsma, T., & Samini, A. (2013). An assistive tool for monitoring physical activities in older adults. 2013 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Delle Fave, A., Bassi, M., Boccaletti, E. S., Roncaglione, C., Bernardelli, G., & Mari, D. (2018). Promoting Well-Being in Old Age: The Psychological Benefits of Two Training Programs of Adapted Physical Activity. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. [CrossRef]

- Dibello, V., Lobbezoo, F., Solfrizzi, V., Custodero, C., Lozupone, M., Pilotto, A., Dibello, A., Santarcangelo, F., Grandini, S., Daniele, A., Lafornara, D., Manfredini, D., & Panza, F. (2024). Oral health indicators and bone mineral density disorders in older age: A systematic review. Ageing Research Reviews, 100, 102412. [CrossRef]

- Downing, J., & Balady, G. J. (2011). The Role of Exercise Training in Heart Failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 58(6), 561–569. [CrossRef]

- Eggenberger, P., Annaheim, S., Kündig, K. A., Rossi, R., Münzer, T., & Bruin, E. D. de. (2020). Heart Rate Variability Mainly Relates to Cognitive Executive Functions and Improves Through Exergame Training in Older Adults: A Secondary Analysis of a 6-Month Randomized Controlled Trial. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ehn, M., Eriksson, L. C., Åkerberg, N., & Johansson, A.-C. (2018). Activity Monitors as Support for Older Persons’ Physical Activity in Daily Life: Qualitative Study of the Users’ Experiences. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 6(2), e34. [CrossRef]

- El-Kader, S. A. A., & Al-Jiffri, O. (2017). Aerobic exercise improves quality of life, psychological well-being and systemic inflammation in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease. African Health Sciences, 16 4, 1045–1055. [CrossRef]

- Fei, L., Kang, X., Sun, W., & Hu, B. (2023). Global research trends and prospects on the first-generation college students from 2002 to 2022: A bibliometric analysis via CiteSpace. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. [CrossRef]

- Figueira, H. A., Figueira, O. A., Figueira, A. A., Figueira, J. A., Polo-Ledesma, R. E., Lyra Da Silva, C. R., & Dantas, E. H. M. (2023). Impact of Physical Activity on Anxiety, Depression, Stress and Quality of Life of the Older People in Brazil. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1127. [CrossRef]

- Forberger, S., Bammann, K., Bauer, J., Boll, S., Bolte, G., Brand, T., Hein, A., Koppelin, F., Lippke, S., Meyer, J., Pischke, C., Voelcker-Rehage, C., & Zeeb, H. (2017). How to Tackle Key Challenges in the Promotion of Physical Activity among Older Adults (65+): The AEQUIPA Network Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(4), 379. [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D., Blomberg, B. B., & Paganelli, R. (2017). Aging, Obesity, and Inflammatory Age-Related Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology, 8. [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, R., Joerin, A., Gentile, B., Lakerink, L., & Rauws, M. (2018). Using Psychological Artificial Intelligence (Tess) to Relieve Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mental Health, 5. [CrossRef]

- Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2016). Positive Psychology Interventions Addressing Pleasure, Engagement, Meaning, Positive Relationships, and Accomplishment Increase Well-Being and Ameliorate Depressive Symptoms: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Online Study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. [CrossRef]

- Gilbody, S., Brabyn, S., Mitchell, A., Ekers, D., McMillan, D., Bailey, D., Hems, D., Graham, C. A. C., Keding, A., & Bosanquet, K. (2022). Can We Prevent Depression in At-Risk Older Adults Using Self-Help? The UK SHARD Trial of Behavioral Activation. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(2), 197–207. [CrossRef]

- Glenisson, P., Glänzel, W., Janssens, F., & De Moor, B. (2005). Combining full text and bibliometric information in mapping scientific disciplines. Information Processing & Management, 41(6), 1548–1572. [CrossRef]

- Goumopoulos, C., & Menti, E. (2019). Stress Detection in Seniors Using Biosensors and Psychometric Tests. Procedia Computer Science, 152, 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Graham, S. A., Lee, E. E., Jeste, D. V., Van Patten, R., Twamley, E. W., Nebeker, C., Yamada, Y., Kim, H.-C., & Depp, C. A. (2020). Artificial intelligence approaches to predicting and detecting cognitive decline in older adults: A conceptual review. Psychiatry Research, 284, 112732. [CrossRef]

- Green, A. E., Kraemer, D. J. M., DeYoung, C. G., Fossella, J. A., & Gray, J. R. (2013). A Gene–Brain–Cognition Pathway: Prefrontal Activity Mediates the Effect of COMT on Cognitive Control and IQ. Cerebral Cortex, 23(3), 552–559. [CrossRef]

- Guzik, T. J., & Touyz, R. M. (2017). Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Vascular Aging in Hypertension. Hypertension, 70(4), 660–667. [CrossRef]

- Hassandra, M., Galanis, E., Hatzigeorgiadis, A., Goudas, M., Mouzakidis, C., Karathanasi, E. M., Petridou, N., Tsolaki, M., Zikas, P., Evangelou, G., Papagiannakis, G., Bellis, G., Kokkotis, C., Panagiotopoulos, S. R., Giakas, G., & Theodorakis, Y. (2021). A Virtual Reality App for Physical and Cognitive Training of Older People With Mild Cognitive Impairment: Mixed Methods Feasibility Study. JMIR Serious Games, 9(1), e24170. [CrossRef]

- Haxhi, J., Mattia, L., Vitale, M., Pisarro, M., Conti, F., & Pugliese, G. (2022). Effects of physical activity/exercise on bone metabolism, bone mineral density and fragility fractures. International Journal of Bone Fragility. [CrossRef]

- Hong, C., Sun, L., Liu, G., Guan, B., Li, C., & Luo, Y. (2023). Response of Global Health Towards the Challenges Presented by Population Aging. China CDC Weekly, 5(39), 884. [CrossRef]

- Hou, B., Wu, Y., & Huang, Y. (2024). Physical exercise and mental health among older adults: The mediating role of social competence. Frontiers in Public Health, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hung, J. (2023). Smart Elderly Care Services in China: Challenges, Progress, and Policy Development. Sustainability, 15(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Iso-Markku, P., Kujala, U. M., Knittle, K., Polet, J., Vuoksimaa, E., & Waller, K. (2022). Physical activity as a protective factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review, meta-analysis and quality assessment of cohort and case–control studies. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 56(12), 701–709. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D., Xu, X., Liu, Z., & Yang, Q. (2023). Editorial: Mental health in older adults with cognitive impairments and dementia: a multidisciplinary perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1297903. [CrossRef]

- Jochen Gläser, Glänzel, W., & Scharnhorst, A. (2017). Same data—different results? Towards a comparative approach to the identification of thematic structures in science. Scientometrics, 111(2), 981–998. [CrossRef]

- Karim, H. T., Vahia, I. V., Iaboni, A., & Lee, E. E. (2022). Editorial: Artificial Intelligence in Geriatric Mental Health Research and Clinical Care. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 859175. [CrossRef]

- Kazeminia, M., Salari, N., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Jalali, R., Abdi, A., Mohammadi, M., Daneshkhah, A., Hosseinian-Far, M., & Shohaimi, S. (2020). The effect of exercise on anxiety in the elderly worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 363. [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, M., Izawa, K. P., Ishihara, K., Yaekura, M., Nagashima, H., Yoshizawa, T., & Okamoto, N. (2021). Predictors of activities of daily living at discharge in elderly patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart and Vessels, 36(4), 509–517. [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, M., Izawa, K. P., Taniue, H., Mimura, Y., Imamura, K., Nagashima, H., & Brubaker, P. H. (2017). Relationship between Activities of Daily Living and Readmission within 90 Days in Hospitalized Elderly Patients with Heart Failure. BioMed Research International, 2017, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Knowles, L. M., Skeath, P., Jia, M., Najafi, B., Thayer, J., & Sternberg, E. M. (2016). New and Future Directions in Integrative Medicine Research Methods with a Focus on Aging Populations: A Review. Gerontology, 62(4), 467–476. [CrossRef]

- Kochovska, S., Currow, D., Chang, S., Johnson, M., Ferreira, D., Morgan, D., Olsson, M., & Ekström, M. (2022). Persisting breathlessness and activities reduced or ceased: A population study in older men. BMJ Open Respiratory Research, 9(1), e001168. [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, O., Kari, T., & Institute for Advanced Management Systems Research, Turku, Finland; Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Helsinki, Finland. (2022). Physical Activity Application Supporting Young Elderly: Insights for Personalization. 35 Th Bled eConference Digital Restructuring and Human (Re)Action, 81–95. [CrossRef]

- Lauzé, M., Martel, D. D., & Aubertin-Leheudre, M. (2017). Feasibility and Effects of a Physical Activity Program Using Gerontechnology in Assisted Living Communities for Older Adults. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18(12), 1069–1075. [CrossRef]

- Lavie, C. J., Ozemek, C., Carbone, S., Katzmarzyk, P. T., & Blair, S. N. (2019). Sedentary Behavior, Exercise, and Cardiovascular Health. Circulation Research, 124(5), 799–815. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-J., So, W.-Y., Youn, H.-S., & Kim, J. (2021). Effects of School-Based Physical Activity Programs on Health-Related Physical Fitness of Korean Adolescents: A Preliminary Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2976. [CrossRef]

- Leung, F. P., Yung, L. M., Laher, I., Yao, X., Chen, Z. Y., & Huang, Y. (2008). Exercise, Vascular Wall and Cardiovascular Diseases. Sports Medicine, 38(12), 1009–1024. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. (2023). Evaluation and Analysis of Elderly Mental Health Based on Artificial Intelligence. Occupational Therapy International, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-Y., Tseng, H.-Y., Lin, Y.-J., Wang, C.-J., & Hsu, W.-C. (2020). Using virtual reality-based training to improve cognitive function, instrumental activities of daily living and neural efficiency in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 56(1). [CrossRef]

- Lindsay Smith, G., Banting, L., Eime, R., O’Sullivan, G., & van Uffelen, J. G. Z. (2017). The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 56. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. (2023). Analysis of Elderly Psychological Resilience and Its Role in Coping with Life Stress. International Journal of Education and Humanities, 11(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Chau, K.-Y., Liu, X., & Wan, Y. (2023). The Progress of Smart Elderly Care Research: A Scientometric Analysis Based on CNKI and WOS. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1086. [CrossRef]

- Lo Coco, D., Corrao, S., & Lopez, G. (2016). Cognitive impairment and stroke in elderly patients. Vascular Health and Risk Management, 105. [CrossRef]

- Lok, N., Lok, S., & Canbaz, M. (2017). The effect of physical activity on depressive symptoms and quality of life among elderly nursing home residents: Randomized controlled trial. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 70, 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Lucia, S., Forte, R., Boccacci, L., Grimandi, L., Bittner, M., Aydin, M., Trentin, C., Tocci, N., & Di Russo, F. (2024). A Nonpharmacologic Treatment for Anxiety in Older Adults Based on Cognitive-Motor Training With Response-Generated Feedback. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 79(2), gbad170. [CrossRef]

- Malle, Vivienne Chi1, , and Claudia B. Rebola2, Gorbunova, G., Yashkin, A., Kravchenko, J., Yashin, A., Akushevich, I., & Stallard, E. (2023). OLDER ADULTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF SIGNALS COMMUNICATED BY ROBOT COMPANIONS FOR CAREGIVING. Innovation in Aging, 7(Supplement_1), 608–609. [CrossRef]

- Mane, K. K., & Börner, K. (2004). Mapping topics and topic bursts in PNAS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(suppl_1), 5287–5290. [CrossRef]

- Marques-Aleixo, I., Santos-Alves, E., Balça, M. M., Rizo-Roca, D., Moreira, P. I., Oliveira, P. J., Magalhães, J., & Ascensão, A. (2015). Physical exercise improves brain cortex and cerebellum mitochondrial bioenergetics and alters apoptotic, dynamic and auto(mito)phagy markers. Neuroscience, 301, 480–495. [CrossRef]

- Mashhadi, Z., Saadati, H., & Dadkhah, M. (2021). Investigating the Putative Mechanisms Mediating the Beneficial Effects of Exercise on the Brain and Cognitive Function. International Journal of Medical Reviews, 8(1), 45–56. [CrossRef]

- McLeod, M., Breen, L., Hamilton, D. L., & Philp, A. (2016). Live strong and prosper: The importance of skeletal muscle strength for healthy ageing. Biogerontology, 17(3), 497–510. [CrossRef]

- Meho, L. I., & Yang, K. (2007). Impact of data sources on citation counts and rankings of LIS faculty: Web of science versus scopus and google scholar. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(13), 2105–2125. [CrossRef]

- Meza, R. M., Santos, R., Nolazco-Flores, J., Rodríguez-Ortiz, G., Anguiano, R., Ríos, A., & Block, A. E. (2017). PlaIMoS: A Remote Mobile Healthcare Platform to Monitor Cardiovascular and Respiratory Variables. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 17. [CrossRef]

- Militello, R., Luti, S., Gamberi, T., Pellegrino, A., Modesti, A., & Modesti, P. A. (2024). Physical Activity and Oxidative Stress in Aging. Antioxidants, 13(5), 557. [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.-P., Nyunt, M. S. Z., Feng, L., Feng, L., Niti, M., Tan, B. Y., Chan, G., Khoo, S. A., Chan, S. M., Yap, P., & Yap, K. B. (2017). Multi-domains lifestyle interventions reduces depressive symptoms among frail and pre-frail older persons: Randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 21(8), 918–926. [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C. L., Miller, B. F., & Lewis, T. L. (2023). Exercise and mitochondrial remodeling to prevent age-related neurodegeneration. Journal of Applied Physiology, 134(1), 181–189. [CrossRef]

- Paillard, T., Rolland, Y., & de Souto Barreto, P. (2015). Protective Effects of Physical Exercise in Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Neurology, 11(3), 212–219. [CrossRef]

- Parker, B. (Ed.). (2012). Stress Proof the Heart: Behavioral Interventions for Cardiac Patients. Springer New York. [CrossRef]

- Pasqualini, L., Ministrini, S., Lombardini, R., Bagaglia, F., Paltriccia, R., Pippi, R., Collebrusco, L., Reginato, E., Sbroma Tomaro, E., Marini, E., D’Abbondanza, M., Scarponi, A. M., De Feo, P., & Pirro, M. (2019). Effects of a 3-month weight-bearing and resistance exercise training on circulating osteogenic cells and bone formation markers in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. Osteoporosis International, 30(4), 797–806. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M., Fernández-Pascual, R., Caballero-Mariscal, D., Sales, D., Guerrero, D., & Uribe, A. (2019). Scientific production on mobile information literacy in higher education: A bibliometric analysis (2006–2017). Scientometrics, 120(1), 57–85. [CrossRef]

- Prabha, S., Sajad, M., Hasan, G. M., Islam, A., Imtaiyaz Hassan, M., & Thakur, S. C. (2024). Recent advancement in understanding of Alzheimer’s disease: Risk factors, subtypes, and drug targets and potential therapeutics. Ageing Research Reviews, 101, 102476. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P., & Zala, L. N. (n.d.). Bibliometrics Analysis and Comparison of Global Research Literatures on Research Data Management extracted from Scopus and Web of Science during 2000—2019.

- Pranckutė, R. (2021). Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications, 9(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Qian, K., Zhang, Z., Yamamoto, Y., & Schuller, B. W. (2021). Artificial Intelligence Internet of Things for the Elderly: From Assisted Living to Health-Care Monitoring. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 38(4), 78–88. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R., Manan, A., Kim, J., & Choi, S. (2024). NLRP3 inflammasome: A key player in the pathogenesis of life-style disorders. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 56(7), 1488–1500. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F., Jacinto, M., Couto, N., Monteiro, D., Monteiro, A. M., Forte, P., & Antunes, R. (2023). Motivational Correlates, Satisfaction with Life, and Physical Activity in Older Adults: A Structural Equation Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 59(3), 599. [CrossRef]

- Rothman, S. M., & Mattson, M. P. (2013). Activity-dependent, stress-responsive BDNF signaling and the quest for optimal brain health and resilience throughout the lifespan. Neuroscience, 239, 228–240. [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, T. M., Abe, M. S., Koculak, M., & Otake-Matsuura, M. (n.d.). Cognitive Assessment Estimation from Behavioral Responses in Emotional Faces Evaluation Task—AI Regression Approach for Dementia Onset Prediction in Aging Societies -.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (n.d.). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.

- Sánchez-Duffhues, G., Hiepen, C., Knaus, P., & Ten Dijke, P. (2015). Bone morphogenetic protein signaling in bone homeostasis. Bone, 80, 43–59. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, A., Reinwand, D., & Schlomann, A. (2019). Designing and Using Digital Mental Health Interventions for Older Adults: Being Aware of Digital Inequality. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10. [CrossRef]

- Senoner, T., & Dichtl, W. (2019). Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Diseases: Still a Therapeutic Target? Nutrients, 11(9), 2090. [CrossRef]

- Shaik, T., Tao, X., Higgins, N., Li, L., Gururajan, R., Zhou, X., & Acharya, U. R. (2023). Remote patient monitoring using artificial intelligence: Current state, applications, and challenges. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 13(2), e1485. [CrossRef]

- Simonsson, E., Sandström, S. L., Hedlund, M., Holmberg, H., Johansson, B., Lindelöf, N., Boraxbekk, C., & Rosendahl, E. (2023). Effects of Controlled Supramaximal High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Global Cognitive Function in Older Adults: The Umeå HIT Study—A Randomized Controlled Trial. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 78, 1581–1590. [CrossRef]

- Sleiman, S. F., Henry, J., Al-Haddad, R., El Hayek, L., Abou Haidar, E., Stringer, T., Ulja, D., Karuppagounder, S. S., Holson, E. B., Ratan, R. R., Ninan, I., & Chao, M. V. (2016). Exercise promotes the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) through the action of the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate. eLife, 5, e15092. [CrossRef]

- Small, H. (1973). Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 24(4), 265–269. [CrossRef]

- Song, D., & Yu, D. S. F. (2019). Effects of a moderate-intensity aerobic exercise programme on the cognitive function and quality of life of community-dwelling elderly people with mild cognitive impairment: A randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 93, 97–105. [CrossRef]

- Suzman, R., Beard, J. R., Boerma, T., & Chatterji, S. (2015). Health in an ageing world—What do we know? The Lancet, 385(9967), 484–486. [CrossRef]

- Tao, X., Chen, Y., Zhen, K., Ren, S., Lv, Y., & Yu, L. (2023). Effect of continuous aerobic exercise on endothelial function: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Physiology, 14. [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z., Wang, L., Li, S., Tan, Y., Qiu, Y., Wu, C., Jin, K., Chen, J., Huang, J., Tang, H., Xiang, H., Wang, B., Yuan, H., & Wu, H. (2021). Low BDNF levels in serum are associated with cognitive impairments in medication-naïve patients with current depressive episode in BD II and MDD. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 90–96. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B. P., Tarumi, T., Sheng, M., Tseng, B., Womack, K. B., Cullum, C. M., Rypma, B., Zhang, R., & Lu, H. (2020). Brain Perfusion Change in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment After 12 Months of Aerobic Exercise Training. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease : JAD, 75(2), 617. [CrossRef]

- Tieland, M., Trouwborst, I., & Clark, B. (2017). Skeletal muscle performance and ageing. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 9, 3–19. [CrossRef]

- van Praag, H., & Christie, B. (2015). Tracking Effects of Exercise on Neuronal Plasticity. Brain Plasticity, 1(1), 3–4. [CrossRef]

- Vankipuram, M., McMahon, S., & Fleury, J. (2012). ReadySteady: App for Accelerometer-based Activity Monitoring and Wellness-Motivation Feedback System for Older Adults. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, 2012, 931.

- Vigorito, C., & Giallauria, F. (2014). Effects of exercise on cardiovascular performance in the elderly. Frontiers in Physiology, 5. [CrossRef]

- Walker, K. A., Ficek, B. N., & Westbrook, R. (2019). Understanding the Role of Systemic Inflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 10(8), 3340–3342. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. P.-H., Ho, Y.-S., Leung, W. K., Goto, T., & Chang, R. C.-C. (2019). Systemic inflammation linking chronic periodontitis to cognitive decline. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 81, 63–73. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Liu, H., Zhang, B.-S., Soares, J. C., & Zhang, X. Y. (2016). Low BDNF is associated with cognitive impairments in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 29, 66–71. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Morkūnas, M., & Wei, J. (2024). Mapping the Landscape of Climate-Smart Agriculture and Food Loss: A Bibliometric and Bibliographic Analysis. Sustainability, 16(17), Article 17. [CrossRef]

- Watson, S., Weeks, B., Weis, L., Harding, A., Horan, S., & Beck, B. (2019). High-Intensity Resistance and Impact Training Improves Bone Mineral Density and Physical Function in Postmenopausal Women With Osteopenia and Osteoporosis: The LIFTMOR Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 34. [CrossRef]

- Wermelinger Ávila, M. P., Corrêa, J. C., Lucchetti, A. L. G., & Lucchetti, G. (2022). Relationship Between Mental Health, Resilience, and Physical Activity in Older Adults: A 2-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 30(1), 73–81. [CrossRef]

- Wilmink, G., Dupey, K., Alkire, S., Grote, J., Zobel, G., Fillit, H. M., & Movva, S. (2020). Artificial Intelligence-Powered Digital Health Platform and Wearable Devices Improve Outcomes for Older Adults in Assisted Living Communities: Pilot Intervention Study. JMIR Aging, 3(2), e19554. [CrossRef]

- Wirth, M., Haase, C. M., Villeneuve, S., Vogel, J., & Jagust, W. J. (2014). Neuroprotective pathways: Lifestyle activity, brain pathology, and cognition in cognitively normal older adults. Neurobiology of Aging, 35(8), 1873–1882. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Niu, L., Yang, K., Xu, J., Zhang, D., Ling, J., Xia, P., Wu, Y., Liu, X., Liu, J., Zhang, J., & Yu, P. (2024). The role and mechanism of RNA-binding proteins in bone metabolism and osteoporosis. Ageing Research Reviews, 96, 102234. [CrossRef]

- Wu, N. N., Tian, H., Chen, P., Wang, D., Ren, J., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Physical Exercise and Selective Autophagy: Benefit and Risk on Cardiovascular Health. Cells, 8(11), 1436. [CrossRef]

- Xi J.-Y., Lin X., & Hao Y.-T. (2022). Measurement and projection of the burden of disease attributable to population aging in 188 countries, 1990-2050: A population-based study. Journal of Global Health, 12, 04093. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Dong, Y., & Chawla, N. V. (2014). Predicting Node Degree Centrality with the Node Prominence Profile (No. arXiv:1412.2269). arXiv. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).