1. Introduction

The dam break experiment has often been addressed in the literature as a validation case for many CFD codes, e.g. [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Despite the fact that an extensive discussion of dam break wave kinematics can be found in the literature, there is some lack of data describing its dynamics, which is useful when assessing certain types of impact flows like those found in slamming and green water events [

7,

8]. In 1999, Zhou et al. [

9] validated their numerical scheme using an experimental work. In that paper, they provided a description of dam break wave kinematics as well as data on wave impact pressures on a solid vertical wall downstream the dam. The details on experimental setup and on applied force transducers were later published in [

10]. The geometry proposed therein is reproduced in the present work. Also, this setup was further used in other experimental campaigns, as those by Wemmenhove et al. [

11] or Kleefsman et al. [

12]. The former repeated and slightly altered experiments of Zhou [

9], the latter presented a fully three-dimensional dam break problem.

Research on dam break flow dynamics was also conducted by Bukreev et al. who studied the forces exerted by the dam break wave on vertical structures downstream the dam [

13,

14]. A similar test case was considered by Gómez-Gesteira et al. [

15] and by Greco et al. [

16], who studied that case to validate their computational model. Other computational works focused on measuring forces considering particular geometries with obstacles.

While literature on the dam break is not scarce, there are few studies treating dam breaks with three-dimensional flows, specially when experiments are involved,

e.g. [

17,

18]. On the contrary, most works have investigated the problem using CFD simulations. In [

19], the Finite Volume method (as implemented in OpenFoam software) was applied to study the problem of an inclined dam break (considering different slopes) with an obstacle. The OpenFoam software was also used in [

20], which addresses the dam break with an obstacle. Only a two dimensional case is studied therein. In [

21], a three dimensional flow around fixed obstacles was numerically studied using Smooth Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH).

Among the few studies addressing the problem under an experimental perspective, except for few cases such as [

22] or [

23], that provide a complete set of data on kinematics of series of several tests, there is a lack of a thorough discussion on the repeatability of variables that are measured during these events. In [

17], a three-dimensional flow in a dam break with an obstacle was experimentally studied. Three repetitions of the experiment were carried out. The flow was characterised through water level measurements at five different locations and velocity measurements using an acoustic Doppler velocimeter. No assessment of the convergence of the statistical parameters was considered. However, a probabilistic approach is crucial to properly describe the fluid dynamics. This is so because dam break flows are characterised by leading to impact events on any downstream walls or obstacles. Any small deviation on external conditions (gate speed, gate induced vibrations, temperature of the fluid, etc.) from one test to the next may induce significant variations on the values of the flow fields (pressure in particular) measured in the experiments.

This paper aims to provide a detailed insight into the dynamics of the dam break flow over a dry horizontal bed under well controlled laboratory conditions when obstacles inducing three dimensional flows are involved. In order to do so, an experimental setup similar to that used by Zhou et al. [

9] and Buchner [

10], widely considered for validation purposes (e.g. [

24,

25]), has been used. Zhou et al. published their experiments in a conference paper [

9] in 1999 and they were later (2002) published as a journal paper by Lee, Zhou her/himself and Cao [

26]. These references [

9,

26] contain the same experimental data and are cited indistinctly in the present paper. The facility used in the present research was already used by Lobovsky

et al. [

1] to perform statistical analysis of simple dam break (without obstacles) experimental data. That facility has been adapted to include an obstacle, in different positions, to induce three dimensional flows.

Special attention has been paid to measurements of the impact pressure of the downstream wave on the flat vertical wall. In order to address the repeatability of the experiments, a large set of measurements is performed under the same experimental conditions.

The main originality and outcome of this research resides in providing a probabilistic description of the impact pressure, of the rise time and of the pressure impulse, and compare them with relevant data from the literature.

The obtained results from a thorough statistical analysis of the experimental data provide novel information about the pressure measurements in 3D dam break test cases and complement the knowledge of the previously published studies discussed above.

In summary, the three main objectives of this work are:

Provide a probabilistic description of the measurements (pressure peaks and rise times), including mean, median, standard deviations, and confidence intervals. The idea is that these data can be used to validate 3D simulations of dambreak flows.

Compare the results obtained in the two configurations studied among them (both with significant 3D effects) and more importantly also with the 2D results published in [

1].

Provide data for other authors with need to validate their models for wave induced structural loads. To this aim, the figures (in MATLAB format) and abundant movies can be downloaded from this link:

https://short.upm.es/q29zb.

The paper is organised as follows: first, the experimental setup and methodology, together with the test matrix, are discussed. Next, the experimental results are presented and analysed. Also, these different cases are compared with previous results in the literature. Finally, the paper is closed by collecting some conclusions and presenting future work.

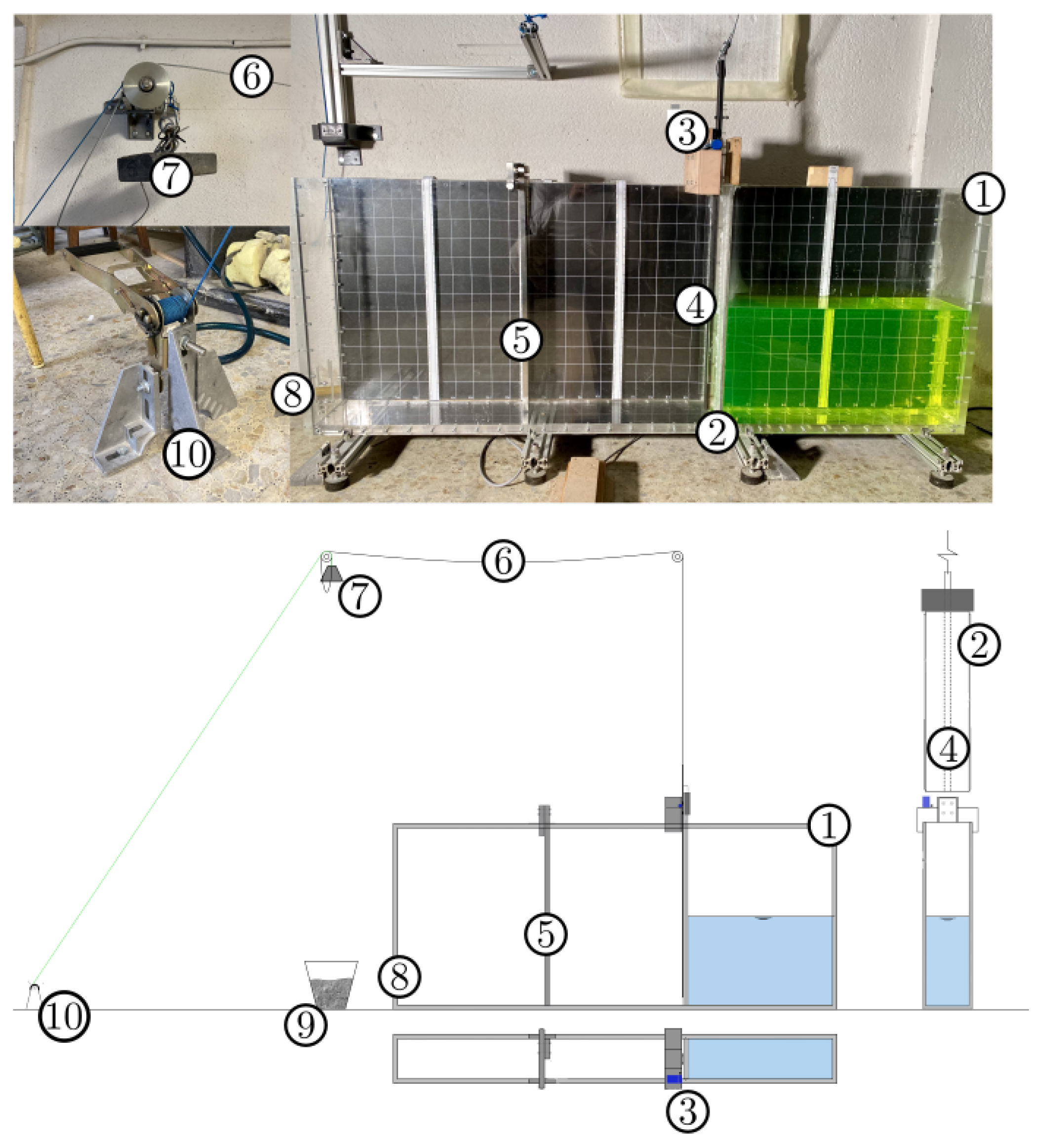

Figure 1.

Snapshot of the experimental setup in the asymmetric configuration and mm (top) and outline (bottom).(1) Plexiglass prismatic tank, (2) Removable gate, (3) Gate motion sensor, (4) Mechanical guide, (5) Rigid obstacle, (6) Set of pulleys and cable, (7) Weight of 15.265 kg, (8) Pressure probes, (9) Bucket of sand, (10) Release mechanism.

Figure 1.

Snapshot of the experimental setup in the asymmetric configuration and mm (top) and outline (bottom).(1) Plexiglass prismatic tank, (2) Removable gate, (3) Gate motion sensor, (4) Mechanical guide, (5) Rigid obstacle, (6) Set of pulleys and cable, (7) Weight of 15.265 kg, (8) Pressure probes, (9) Bucket of sand, (10) Release mechanism.

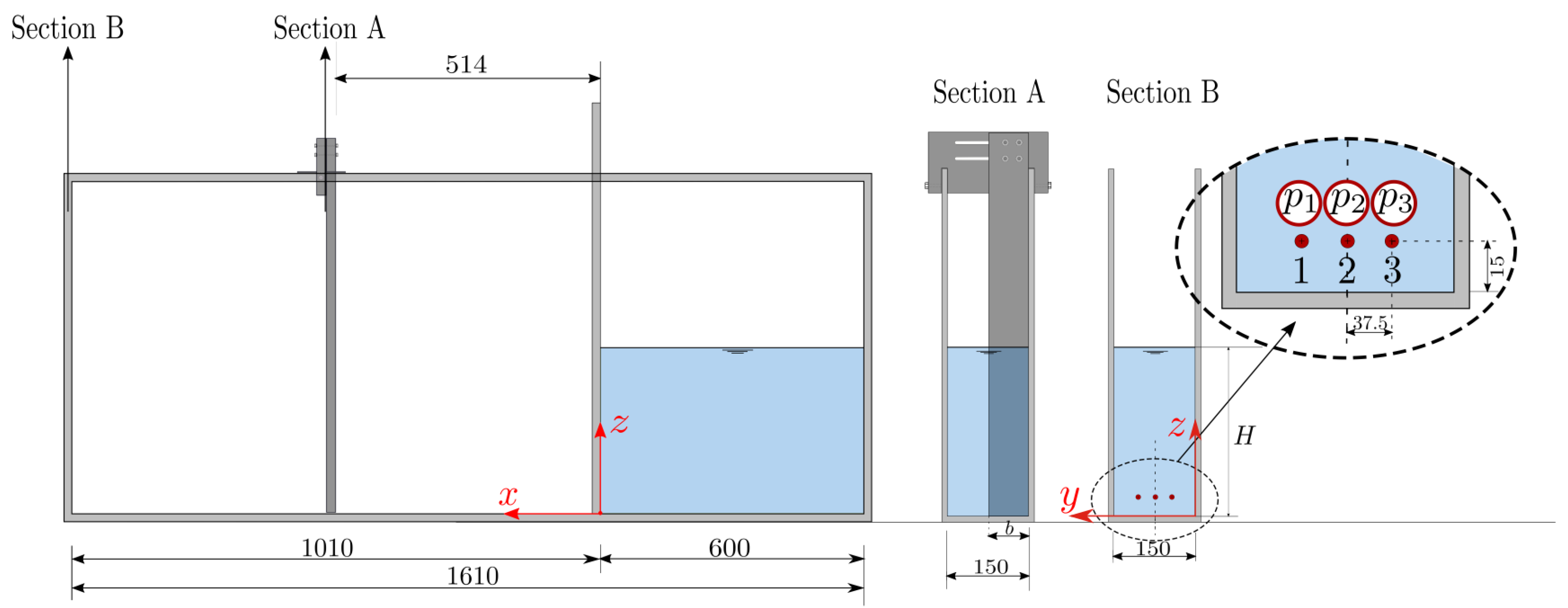

Figure 2.

Schematic of the tank with its dimensions (in mm) for the asymmetric flow configuration and the pressure probe locations. All distances are expressed in mm. Sensors 1, 2 and 3 record the pressure signals , and respectively.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the tank with its dimensions (in mm) for the asymmetric flow configuration and the pressure probe locations. All distances are expressed in mm. Sensors 1, 2 and 3 record the pressure signals , and respectively.

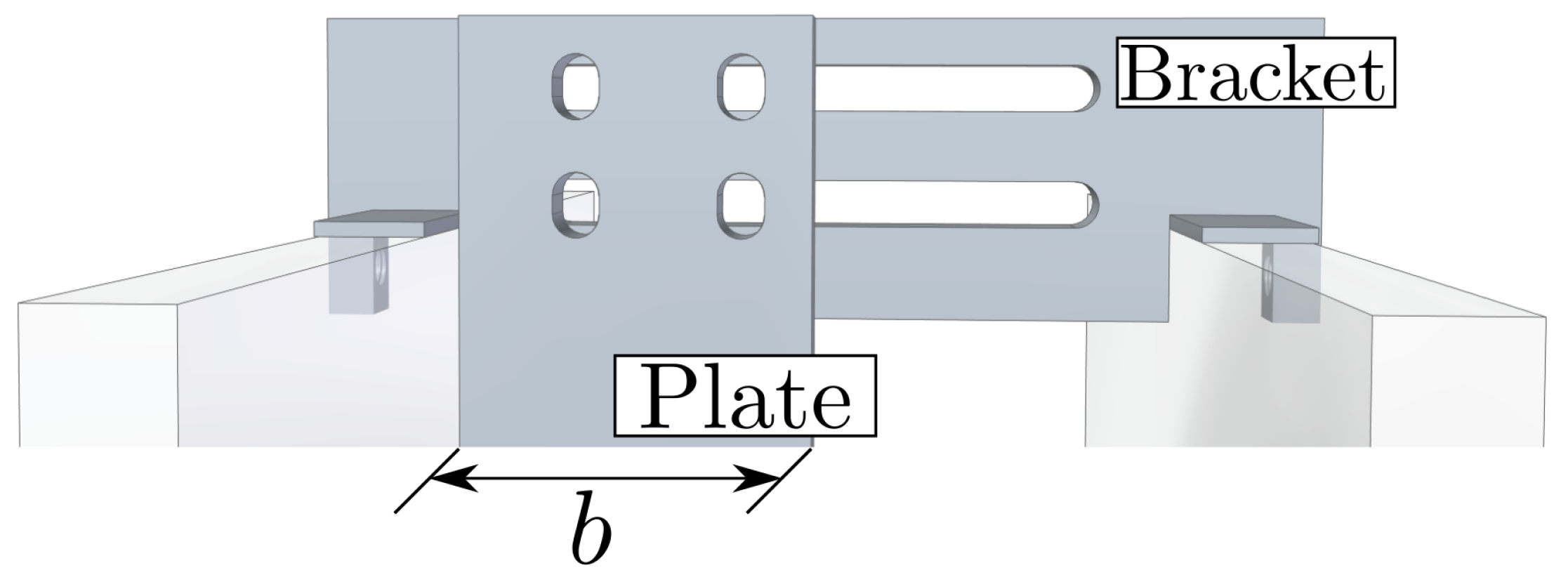

Figure 3.

Detail view of the CAD model of the obstacle placed in the asymmetric flow configuration diplaying the bracket and the plate. The length mm represents the width of the plate.

Figure 3.

Detail view of the CAD model of the obstacle placed in the asymmetric flow configuration diplaying the bracket and the plate. The length mm represents the width of the plate.

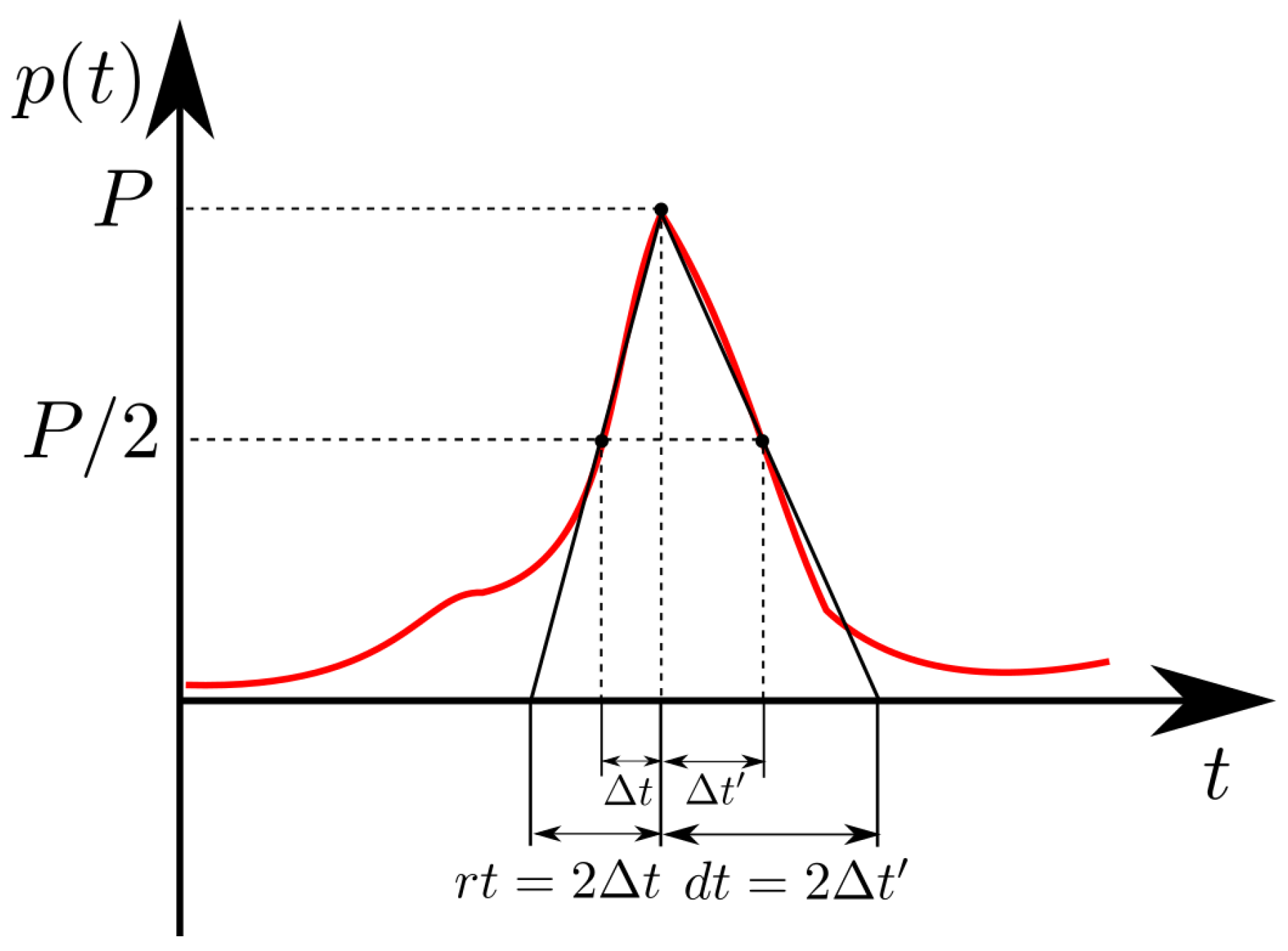

Figure 4.

Outline of the rise time and decay time definition. The continuous black line represents the triangular approximation of the pressure impulse.

Figure 4.

Outline of the rise time and decay time definition. The continuous black line represents the triangular approximation of the pressure impulse.

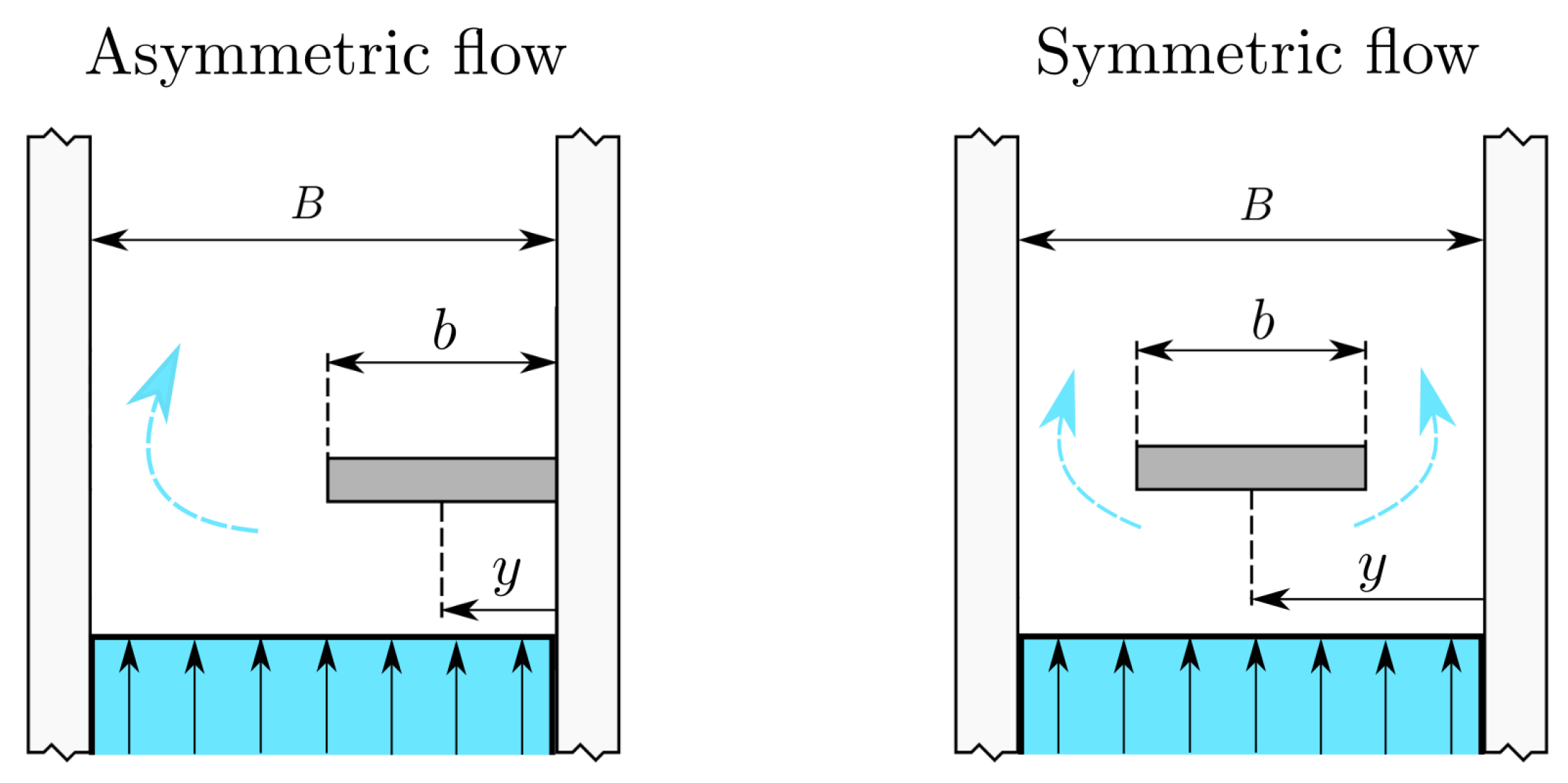

Figure 5.

Top view of the tested configurations: asymmetrical (left) and symmetrical (right). The breadth of the plate is b, the breadth of the inner volume of the tank is B, and the distance from the lateral wall to the center of the plate is y.

Figure 5.

Top view of the tested configurations: asymmetrical (left) and symmetrical (right). The breadth of the plate is b, the breadth of the inner volume of the tank is B, and the distance from the lateral wall to the center of the plate is y.

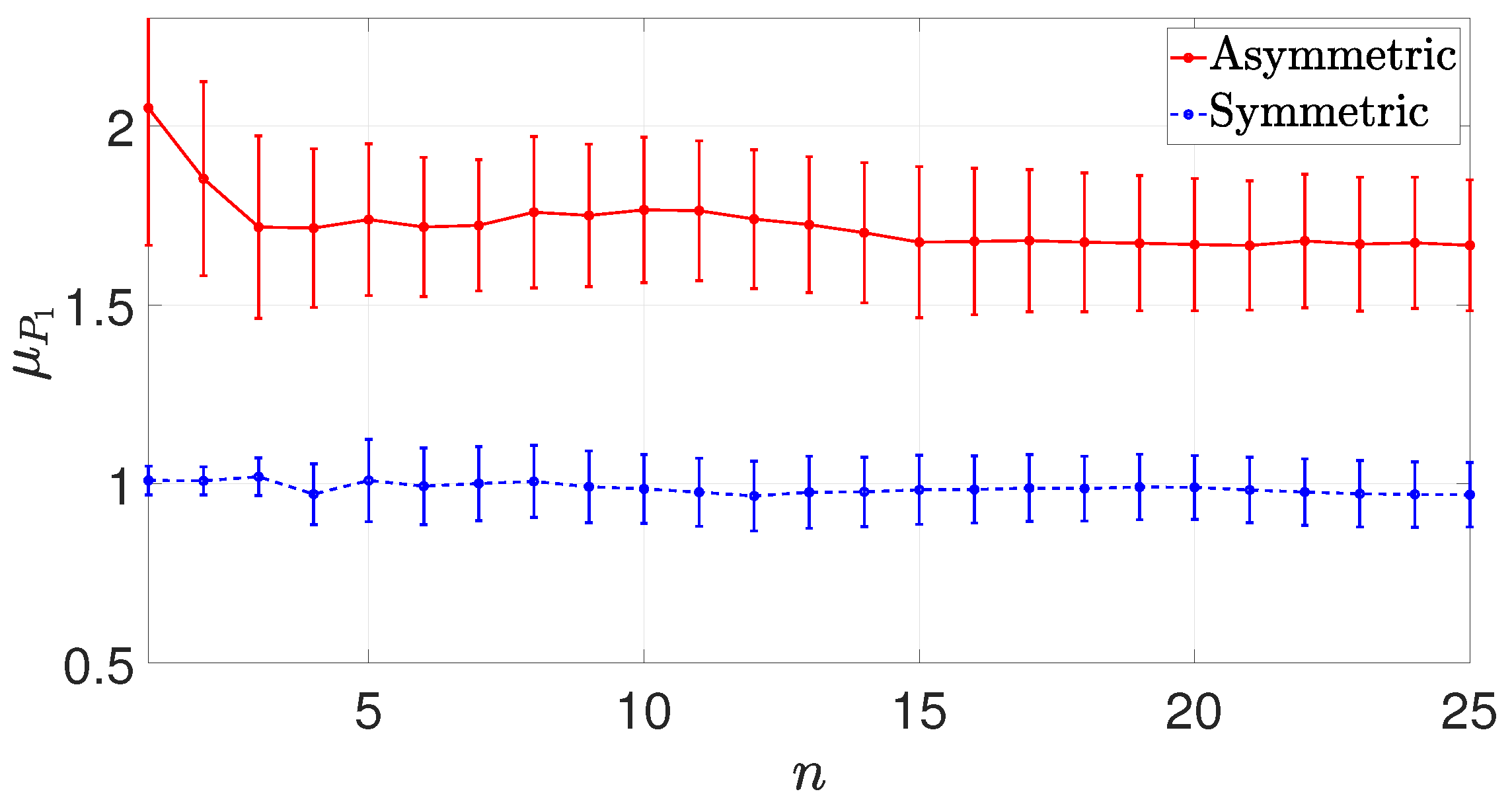

Figure 6.

Running mean (left) and running standard deviation (right) of the peak pressure values P for sensor 1 in non-dimensional units, dividing by . Presented values for asymmetric (continuous line) and symmetric configurations (dotted line).

Figure 6.

Running mean (left) and running standard deviation (right) of the peak pressure values P for sensor 1 in non-dimensional units, dividing by . Presented values for asymmetric (continuous line) and symmetric configurations (dotted line).

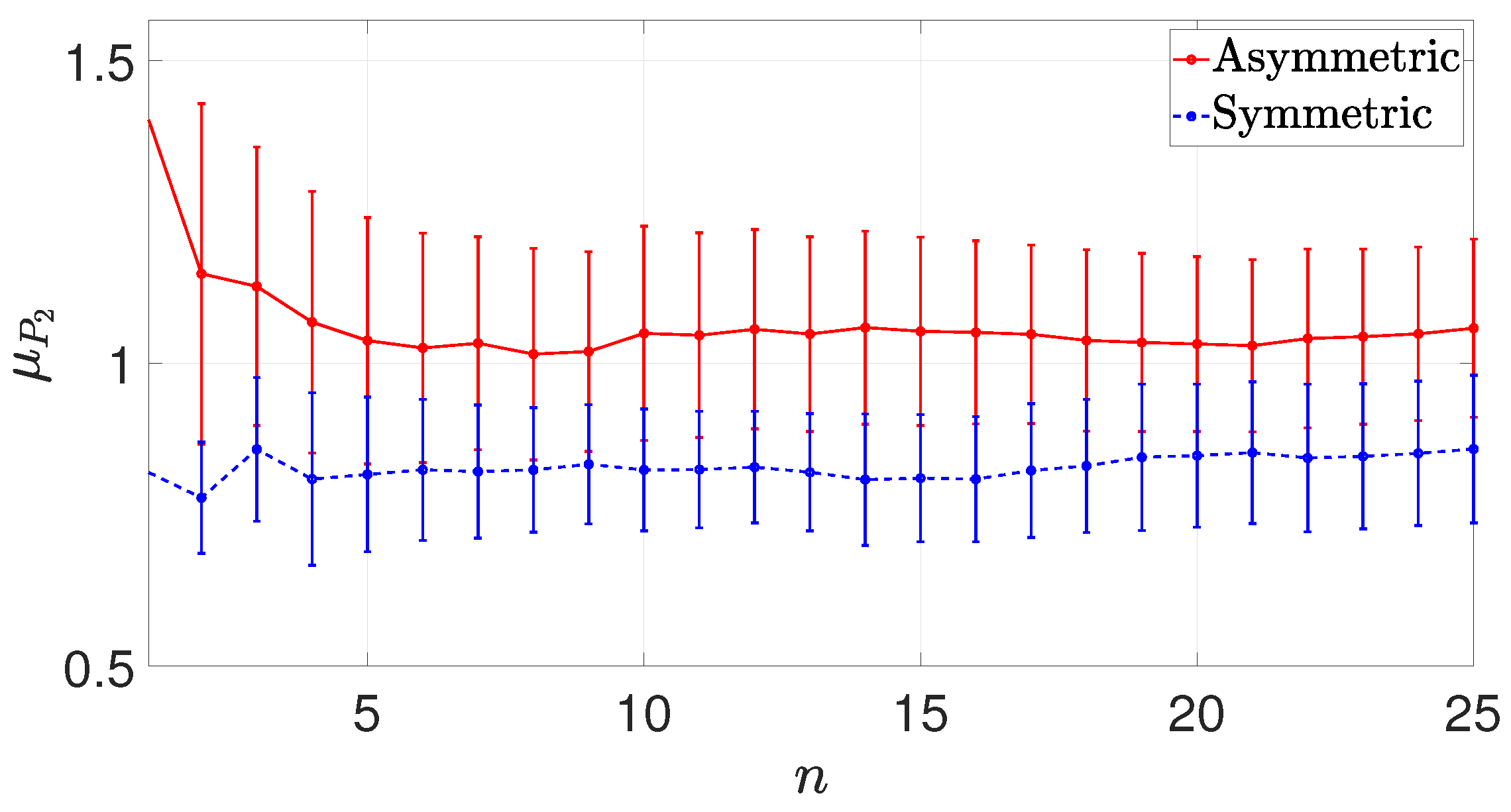

Figure 7.

Running mean (left) and running standard deviation (right) of the peak pressure values P for sensor 2 in non-dimensional units, dividing by . Presented values for asymmetric (continuous line) and symmetric configurations (dotted line).

Figure 7.

Running mean (left) and running standard deviation (right) of the peak pressure values P for sensor 2 in non-dimensional units, dividing by . Presented values for asymmetric (continuous line) and symmetric configurations (dotted line).

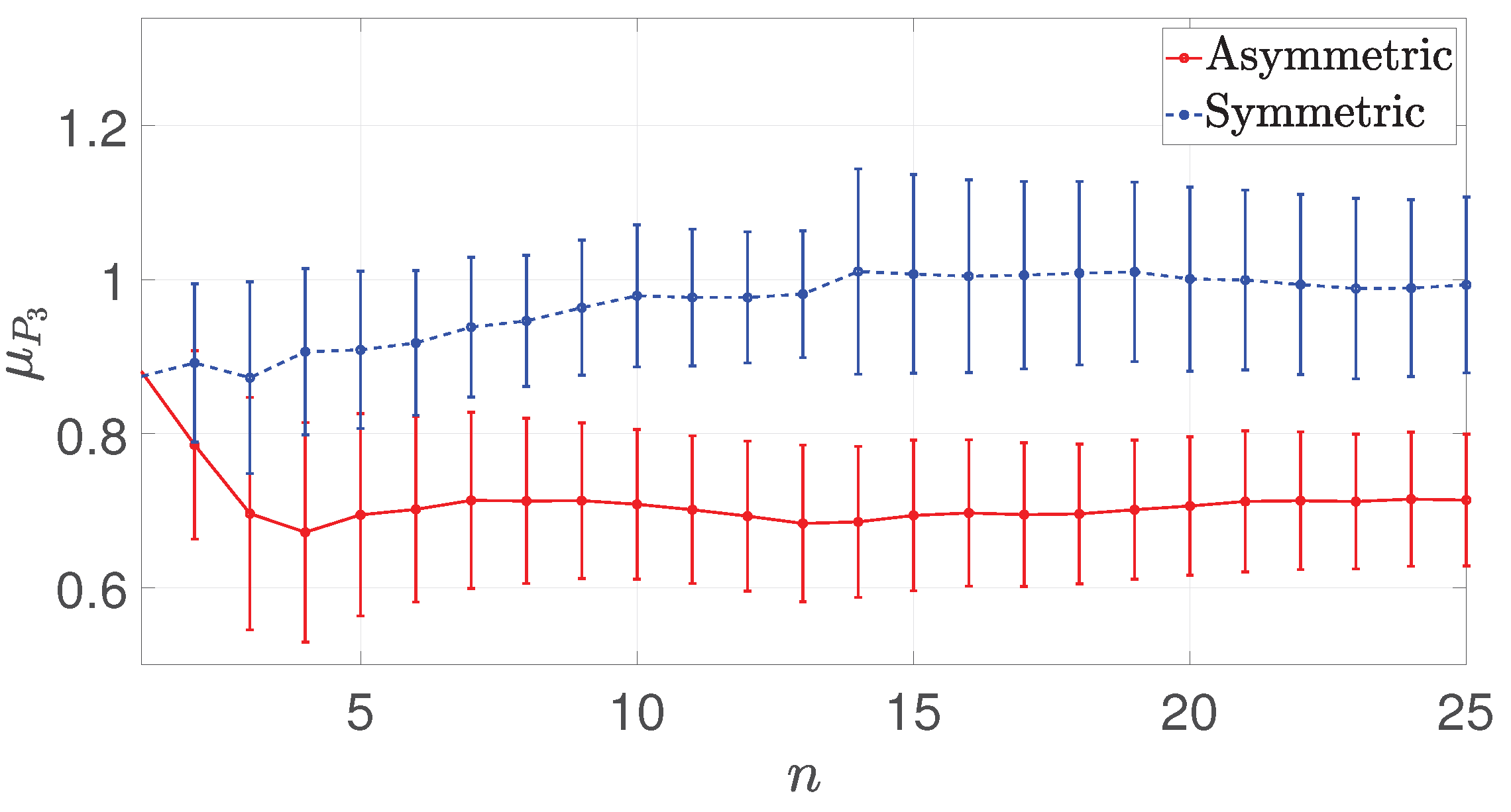

Figure 8.

Running mean (left) and running standard deviation (right) of the peak pressure values P for sensor 3 in non-dimensional units, dividing by . Presented values for asymmetric (continuous line) and symmetric configurations (dotted line).

Figure 8.

Running mean (left) and running standard deviation (right) of the peak pressure values P for sensor 3 in non-dimensional units, dividing by . Presented values for asymmetric (continuous line) and symmetric configurations (dotted line).

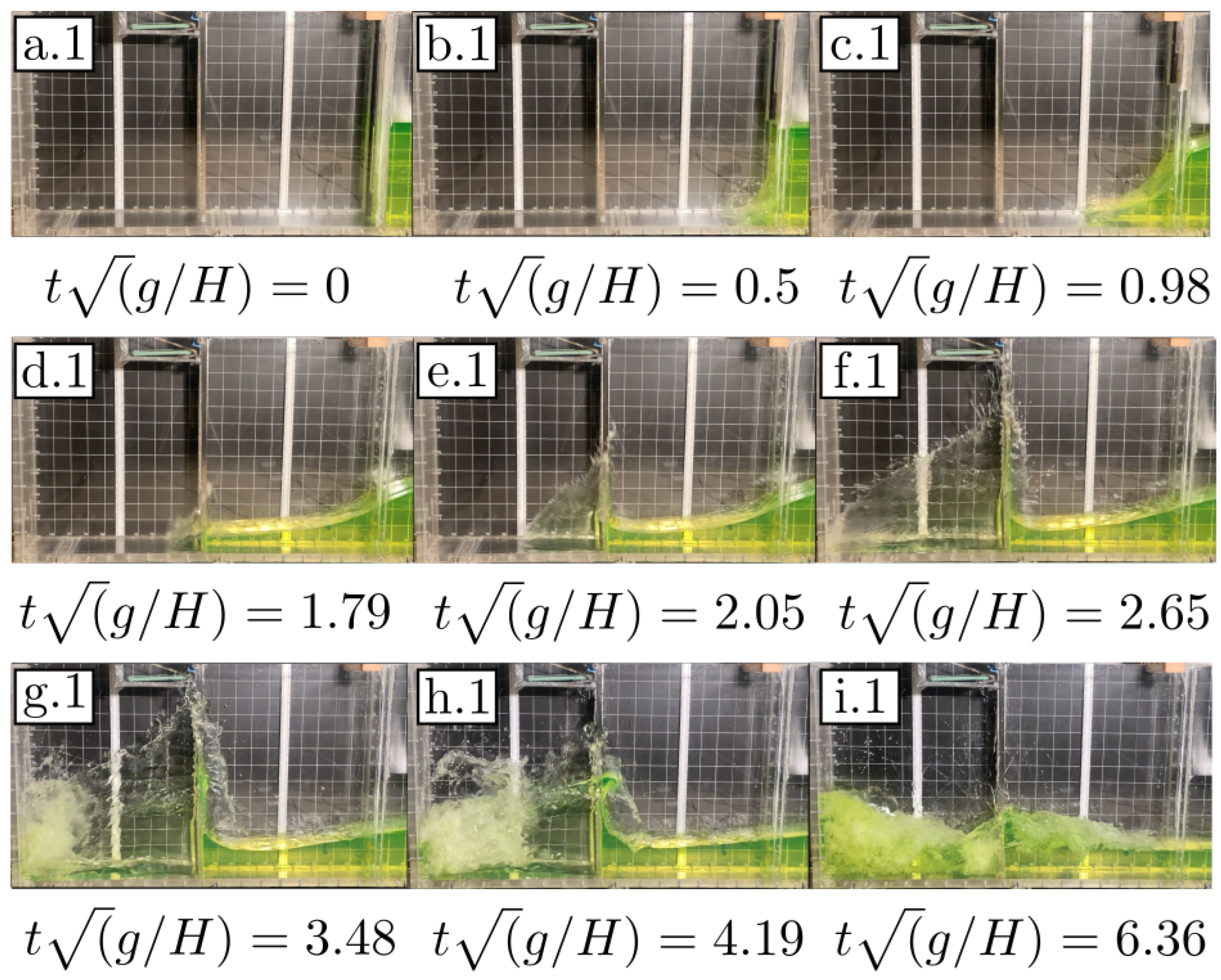

Figure 9.

Front view of the characteristic instants of a dam break experiment with the presence of an obstacle in the asymmetric configuration.

Figure 9.

Front view of the characteristic instants of a dam break experiment with the presence of an obstacle in the asymmetric configuration.

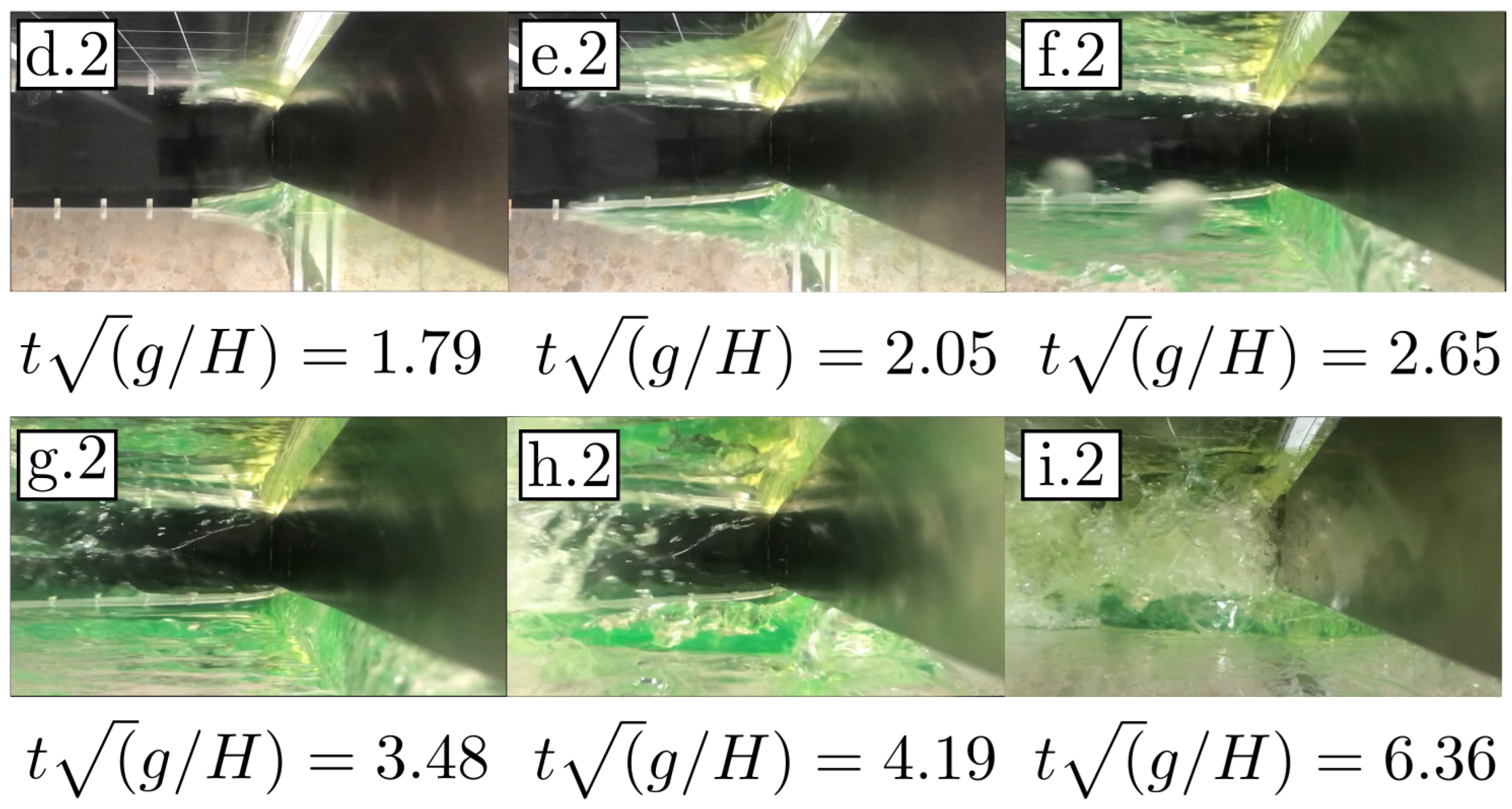

Figure 10.

Top view of the characteristic instants of a dam break experiment with the presence of an obstacle in the asymmetric configuration.

Figure 10.

Top view of the characteristic instants of a dam break experiment with the presence of an obstacle in the asymmetric configuration.

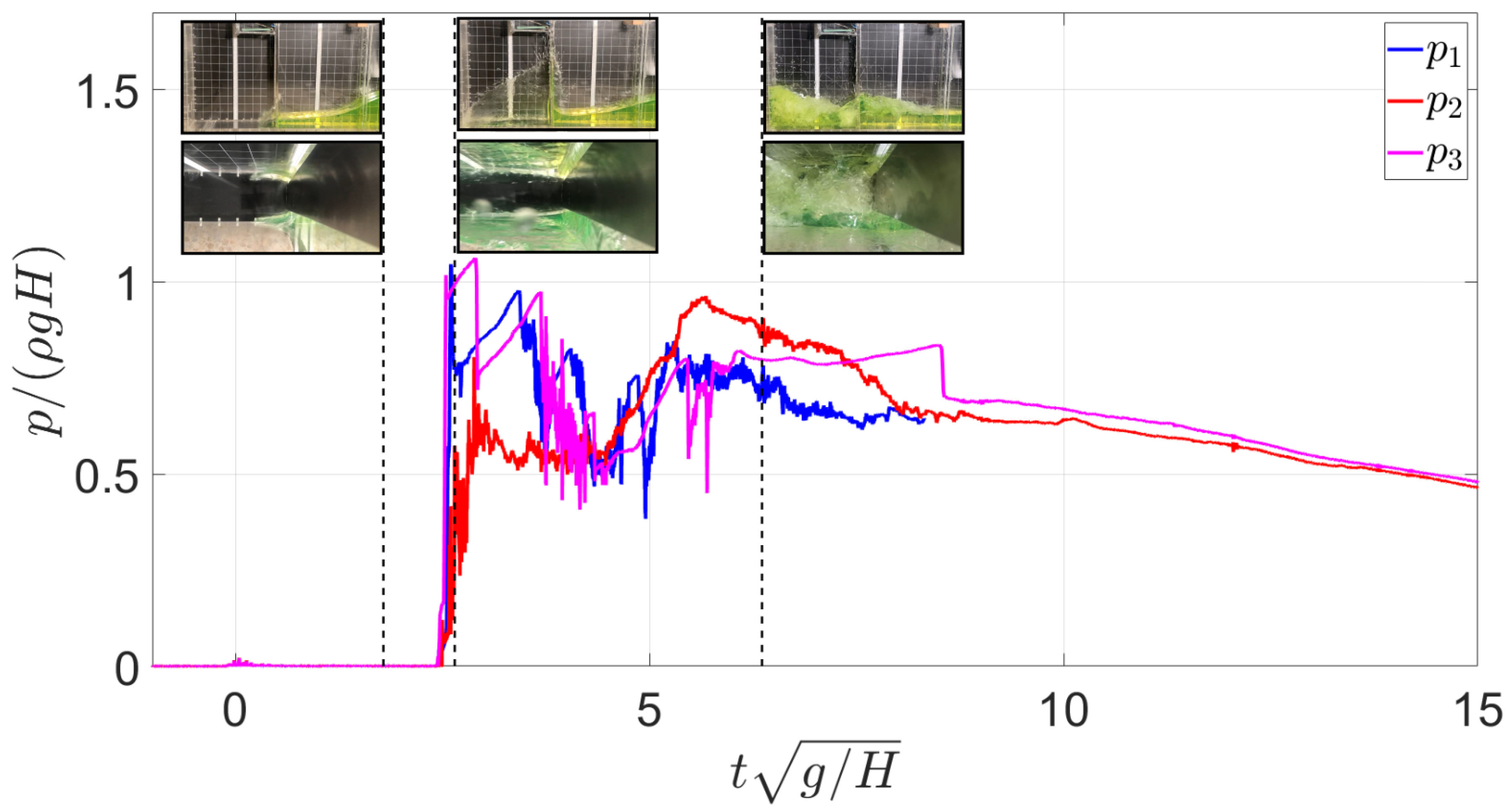

Figure 11.

Pressure measurements over time for sensors 1, 2 and 3 of a typical impact event in the asymmetric configuration.

Figure 11.

Pressure measurements over time for sensors 1, 2 and 3 of a typical impact event in the asymmetric configuration.

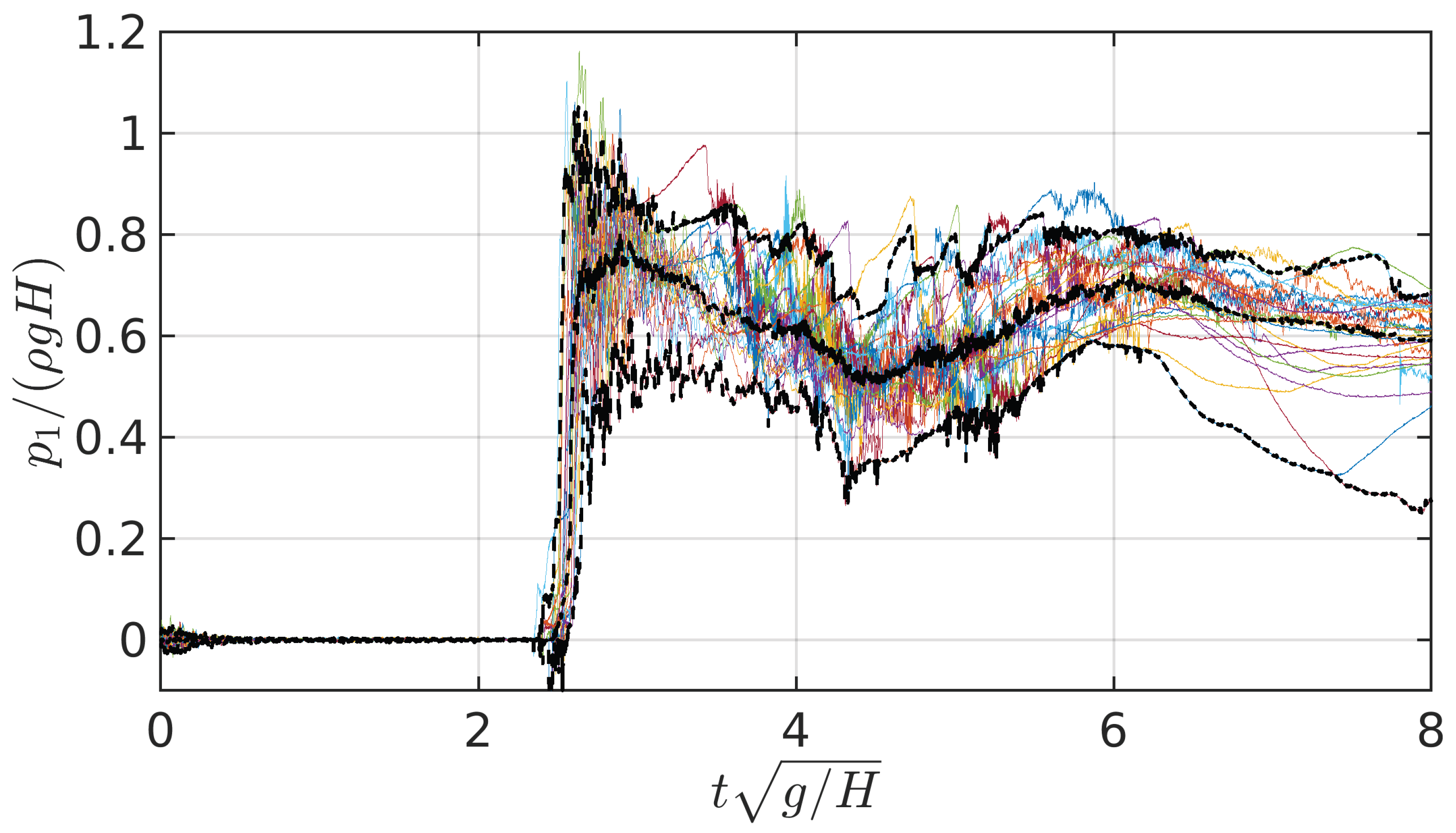

Figure 12.

Sensor 1 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the asymmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

Figure 12.

Sensor 1 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the asymmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

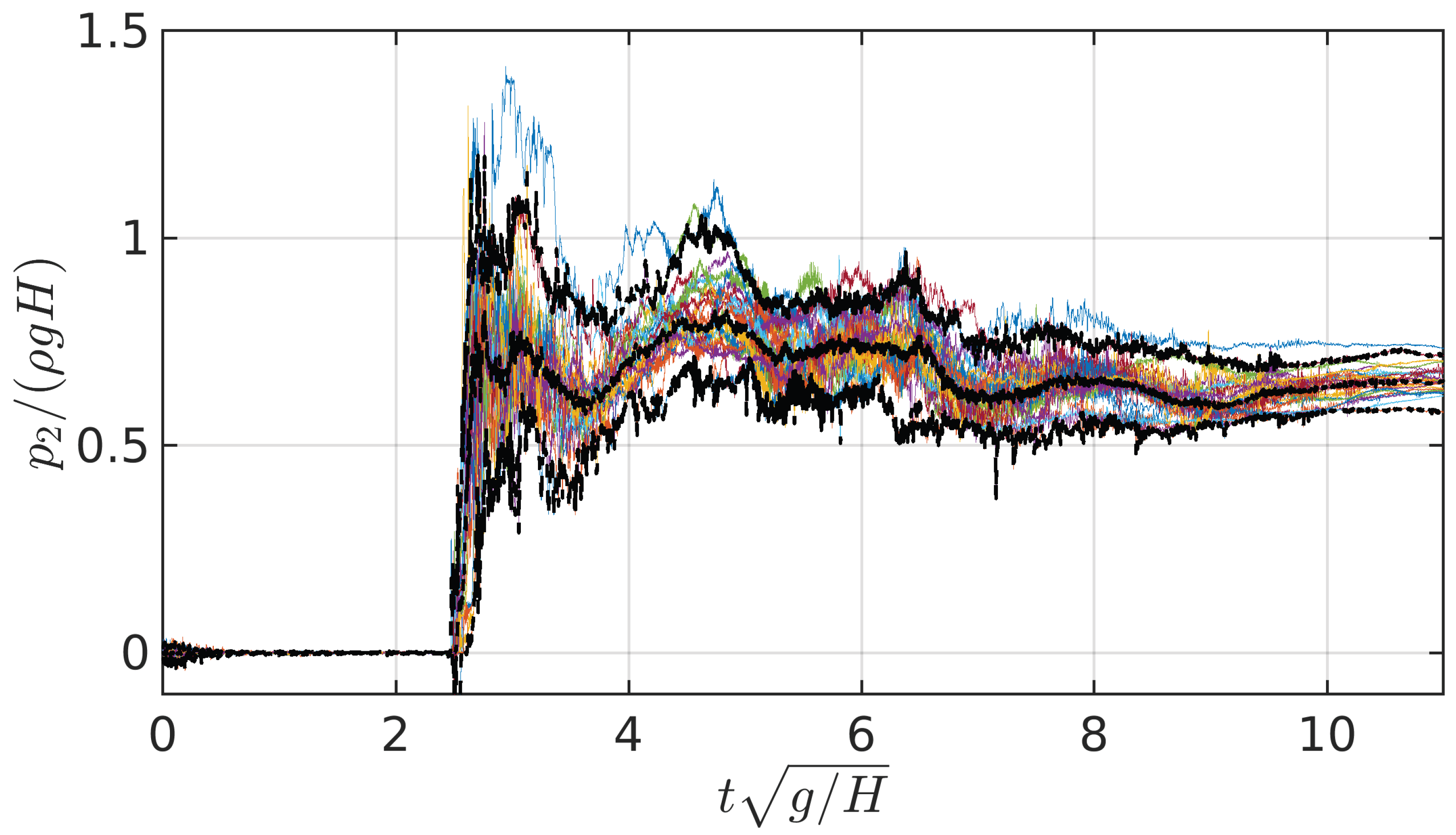

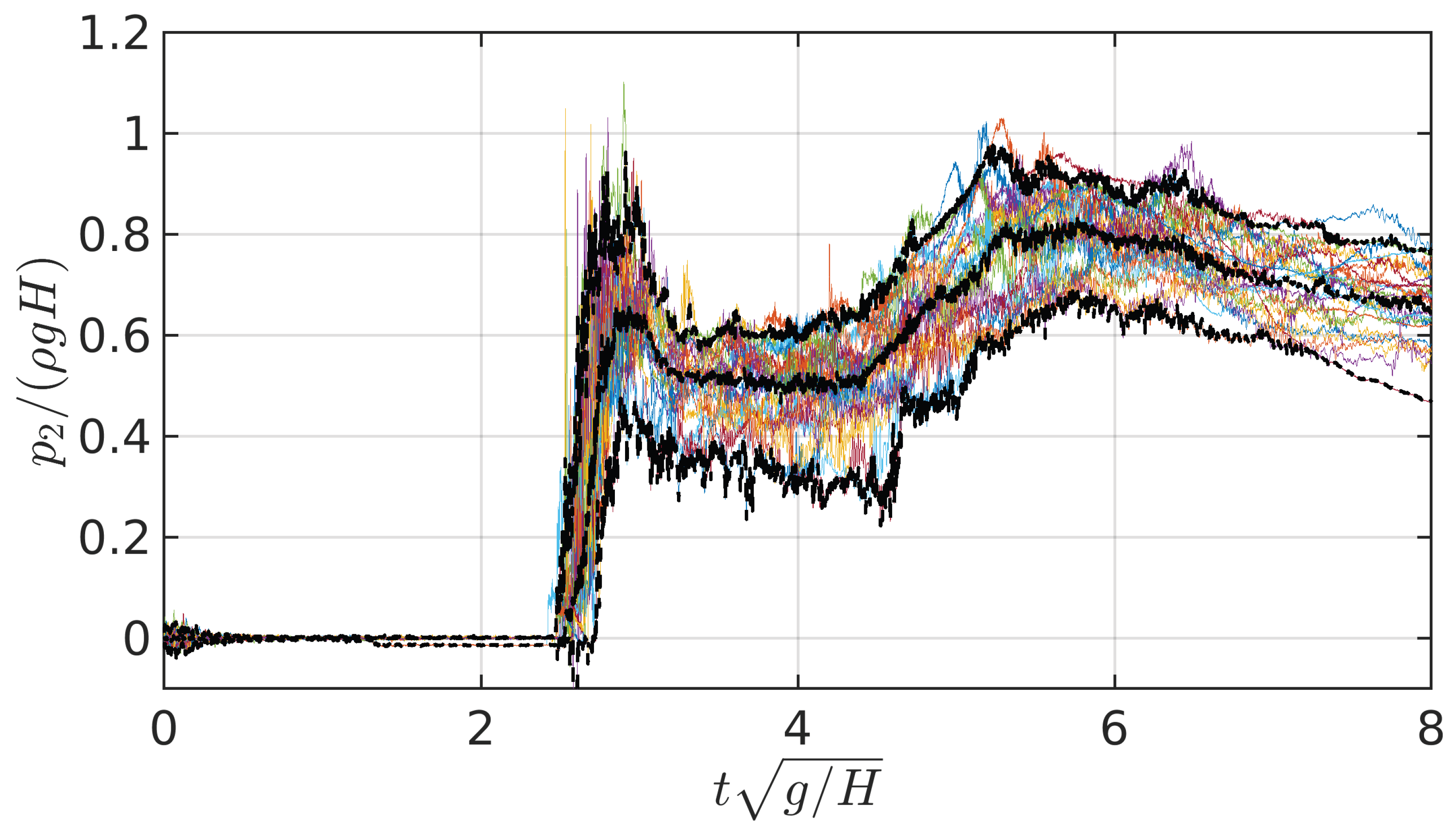

Figure 13.

Sensor 2 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the asymmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

Figure 13.

Sensor 2 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the asymmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

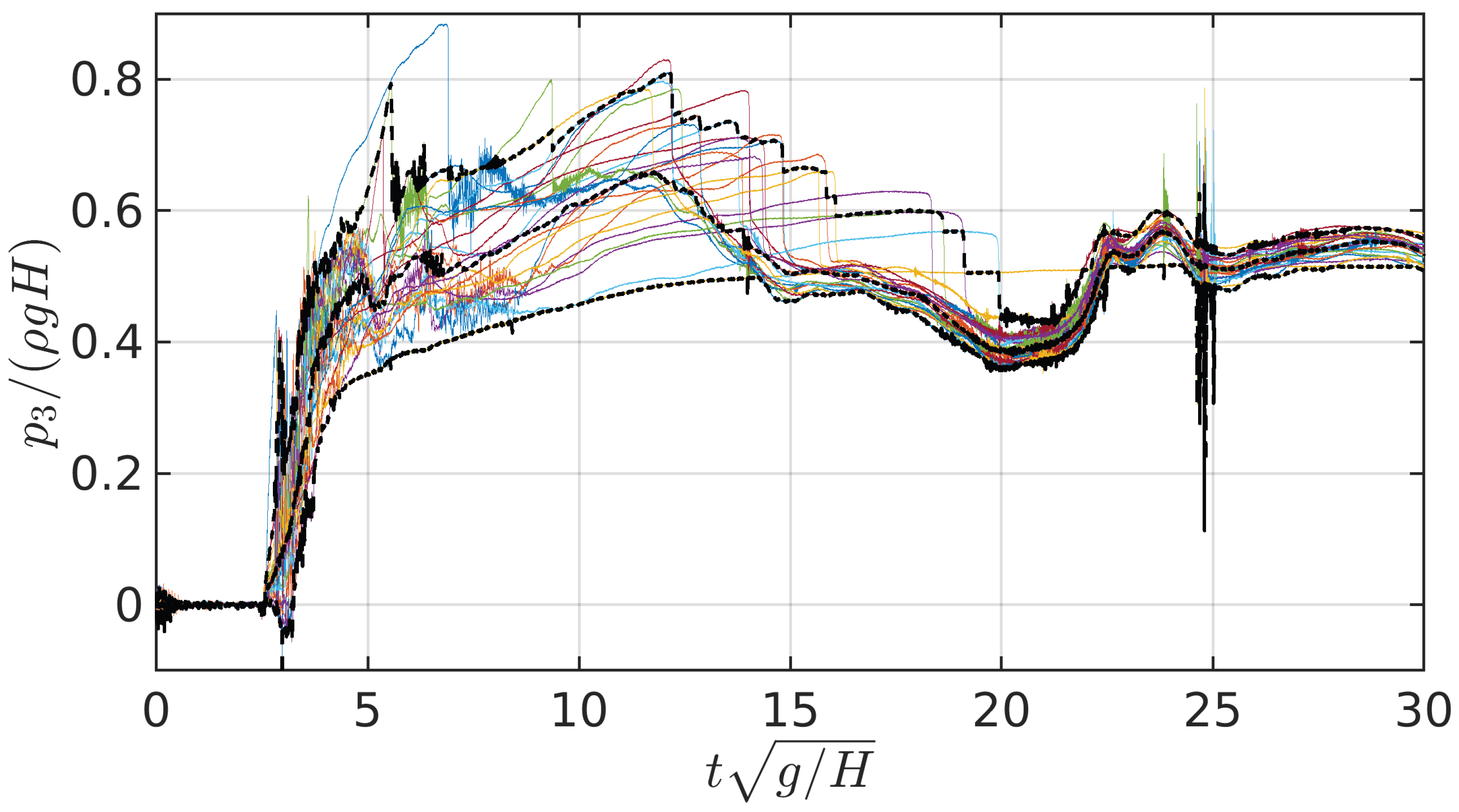

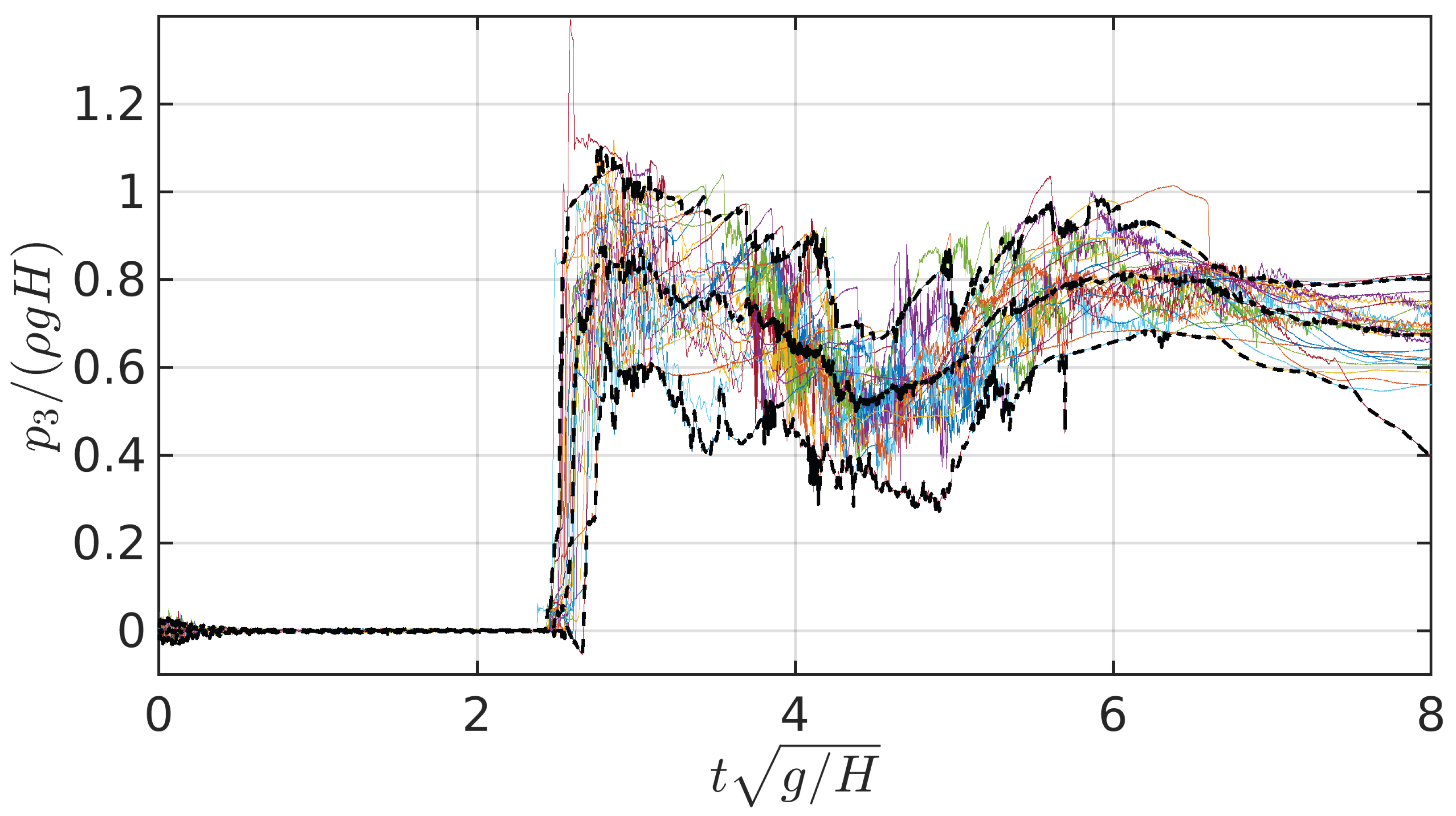

Figure 14.

Sensor 3 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the asymmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

Figure 14.

Sensor 3 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the asymmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

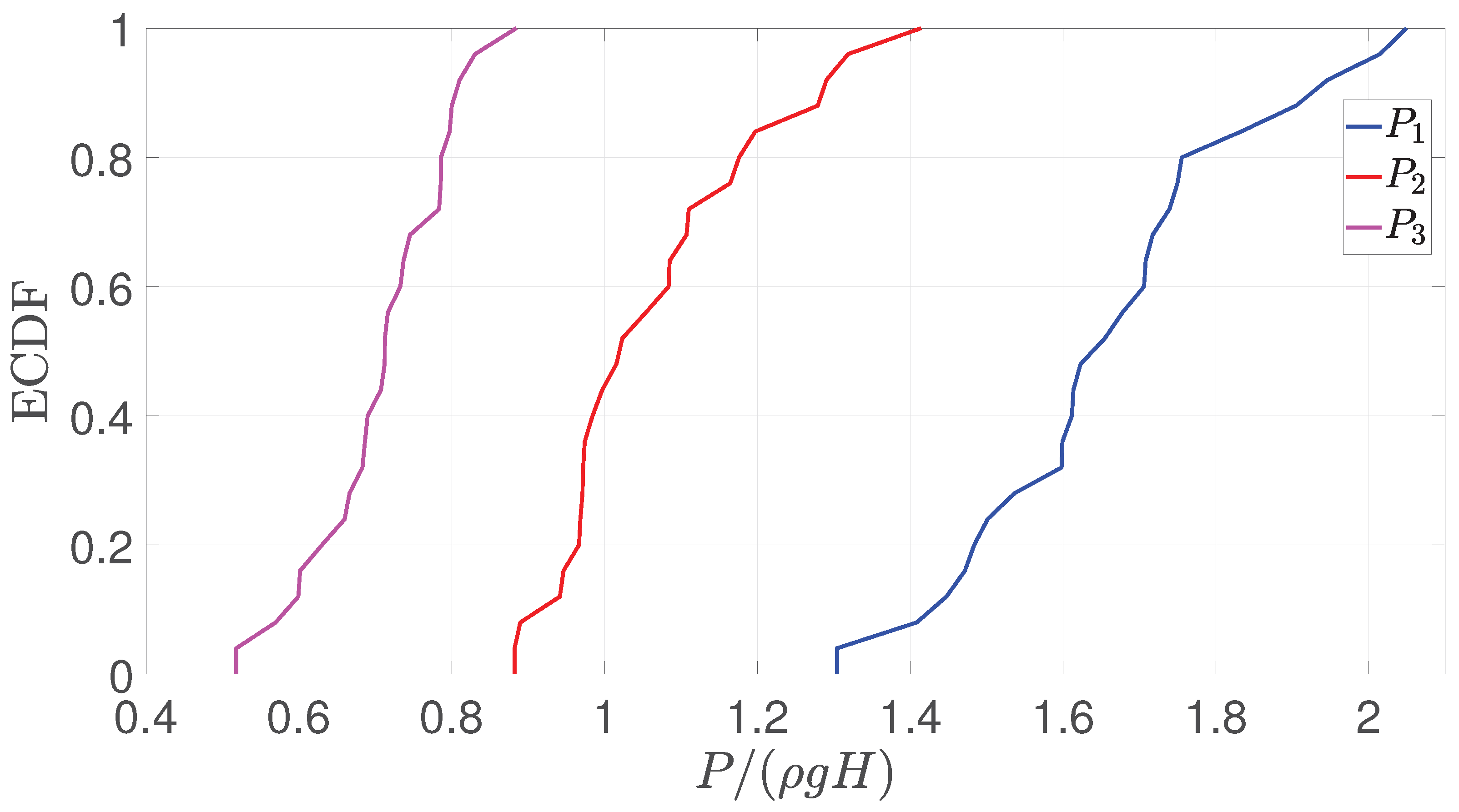

Figure 15.

ECDF of the pressure peak P for sensors 1, 2 and 3 in the asymmetric configuration.

Figure 15.

ECDF of the pressure peak P for sensors 1, 2 and 3 in the asymmetric configuration.

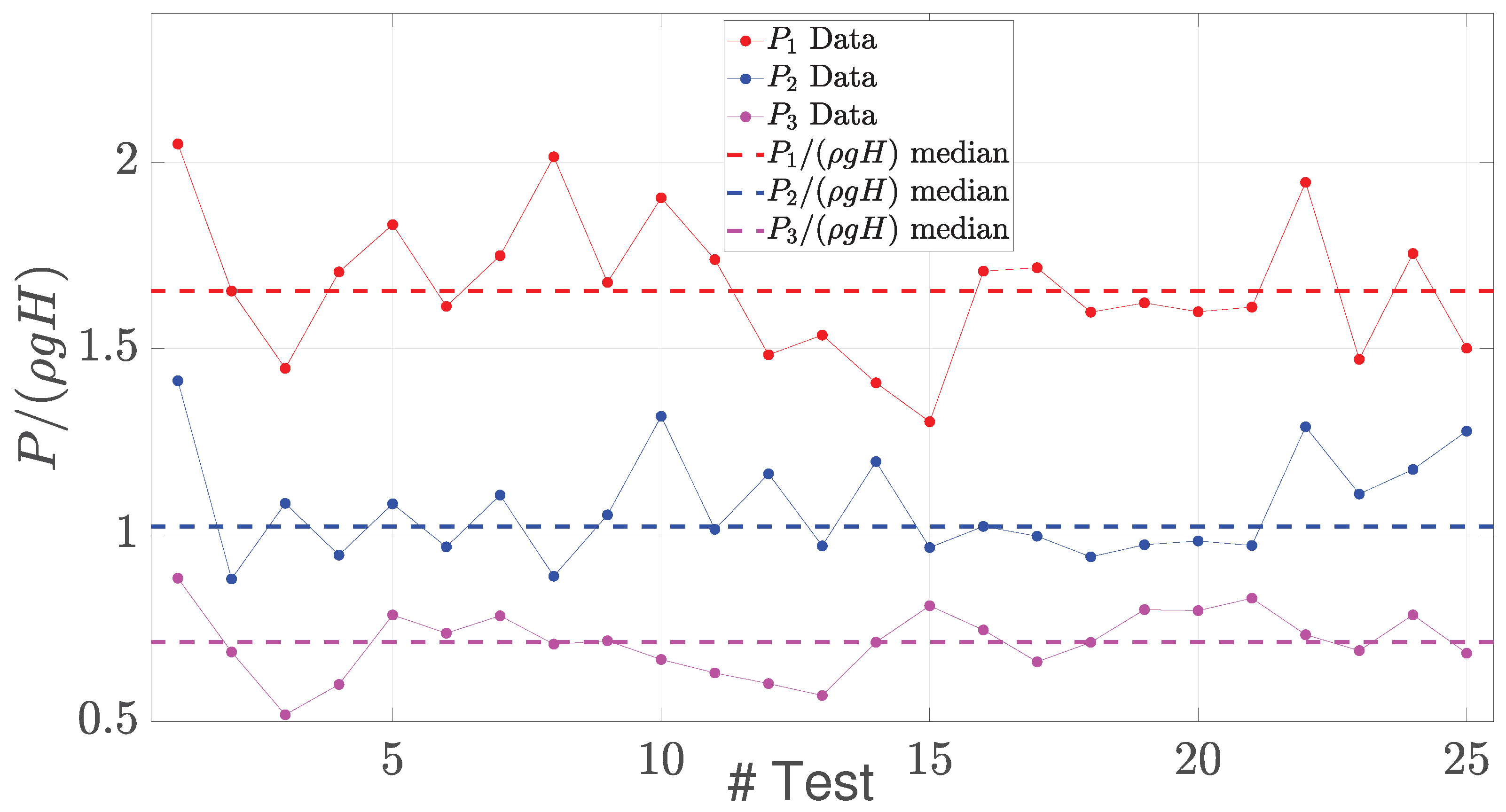

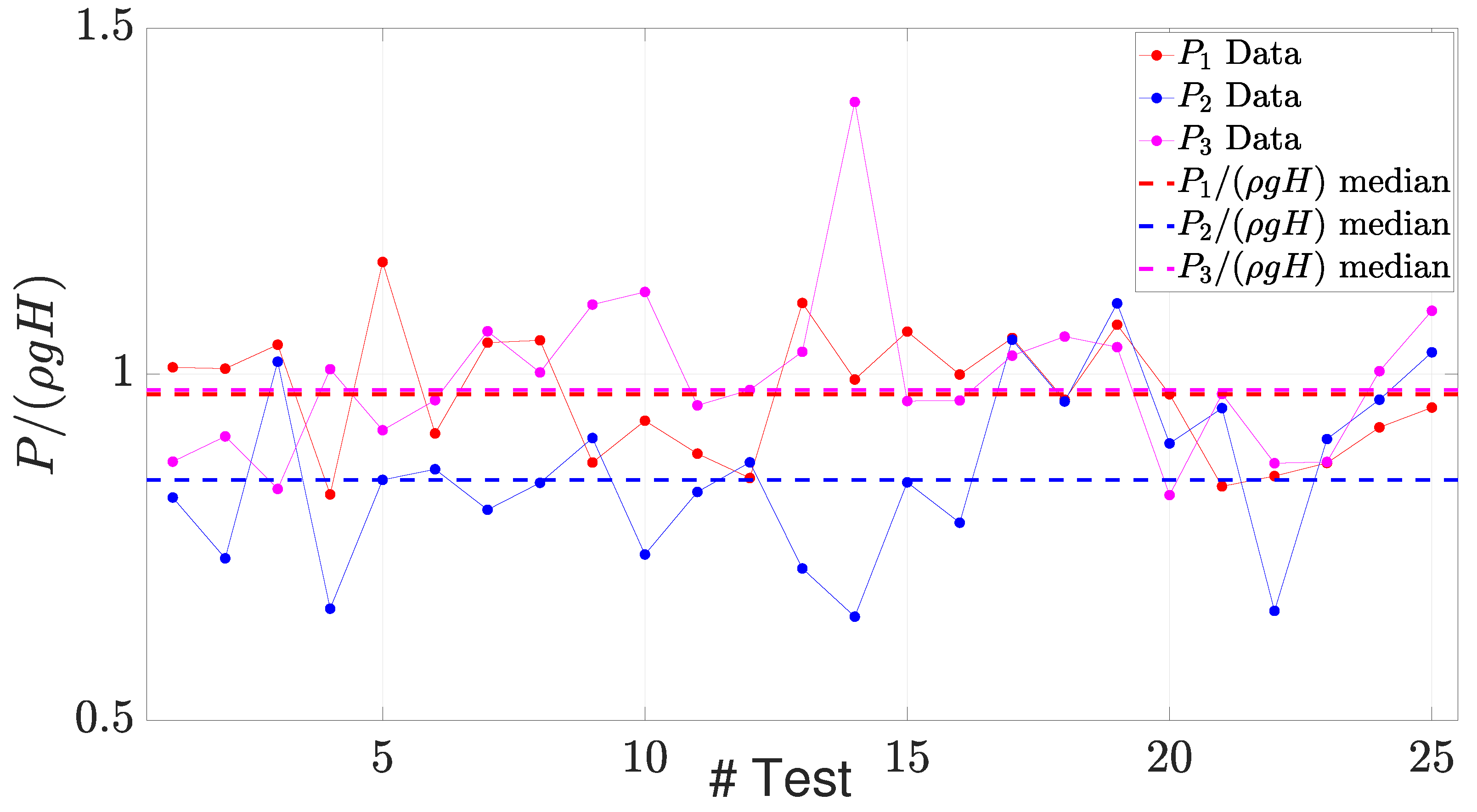

Figure 16.

Maximum pressure peaks of sensors 1, 2 and 3 and their repective medians for the conducted 25 tests in the asymmetric flow configuration.

Figure 16.

Maximum pressure peaks of sensors 1, 2 and 3 and their repective medians for the conducted 25 tests in the asymmetric flow configuration.

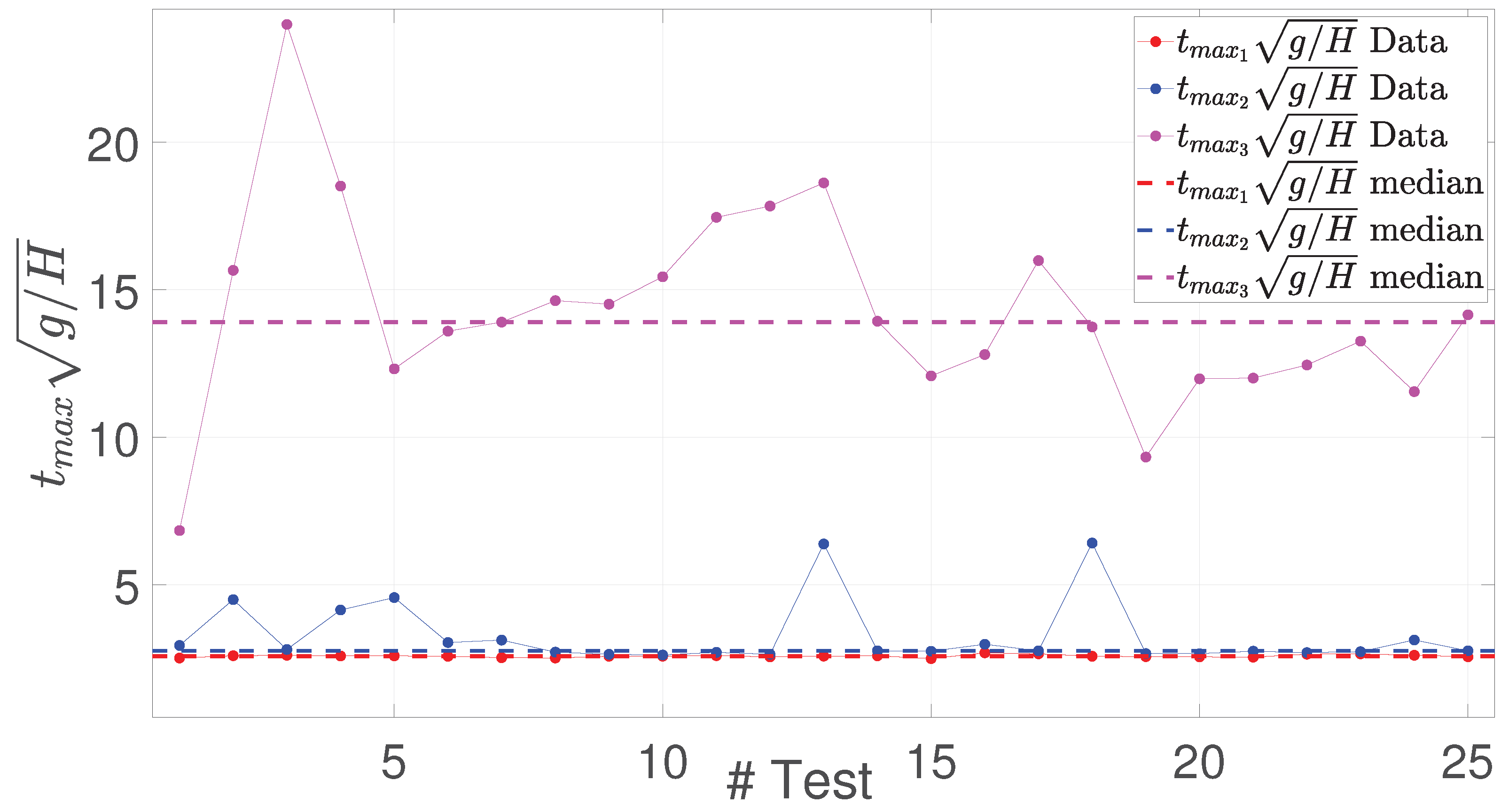

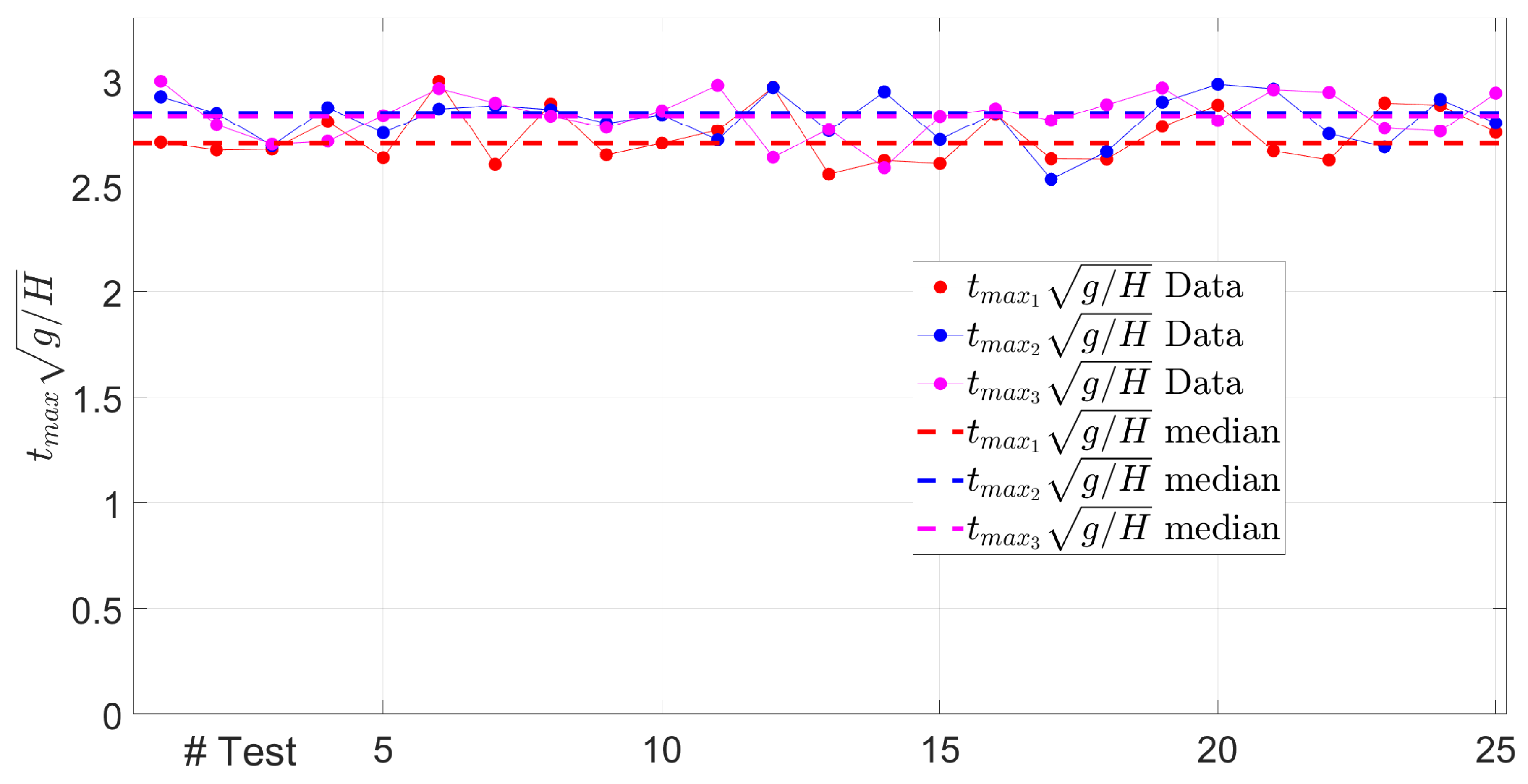

Figure 17.

Maximum pressure peak instants of sensors 1, 2 and 3 and their repective medians for the conducted 25 tests in the asymmetric flow configuration.

Figure 17.

Maximum pressure peak instants of sensors 1, 2 and 3 and their repective medians for the conducted 25 tests in the asymmetric flow configuration.

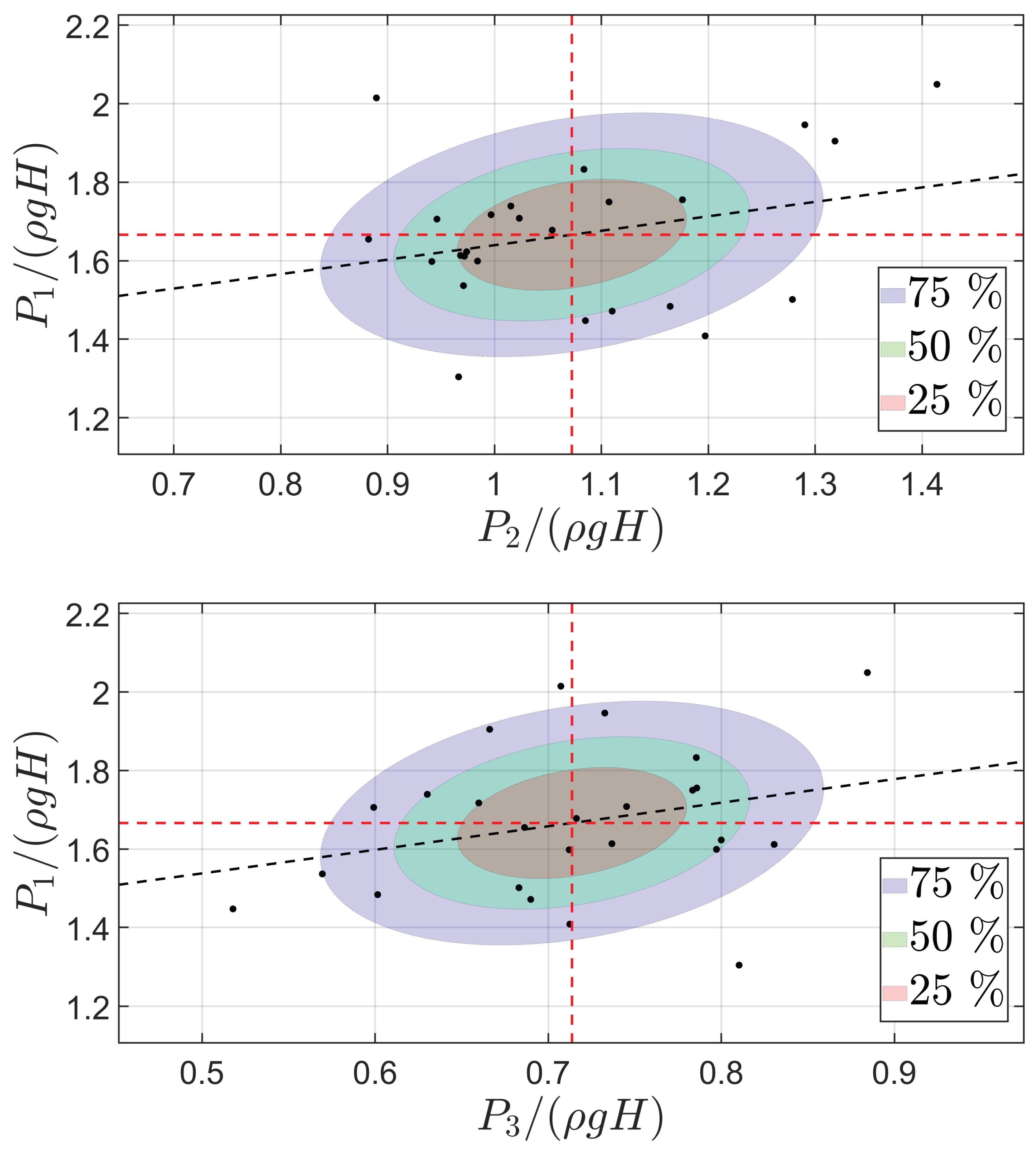

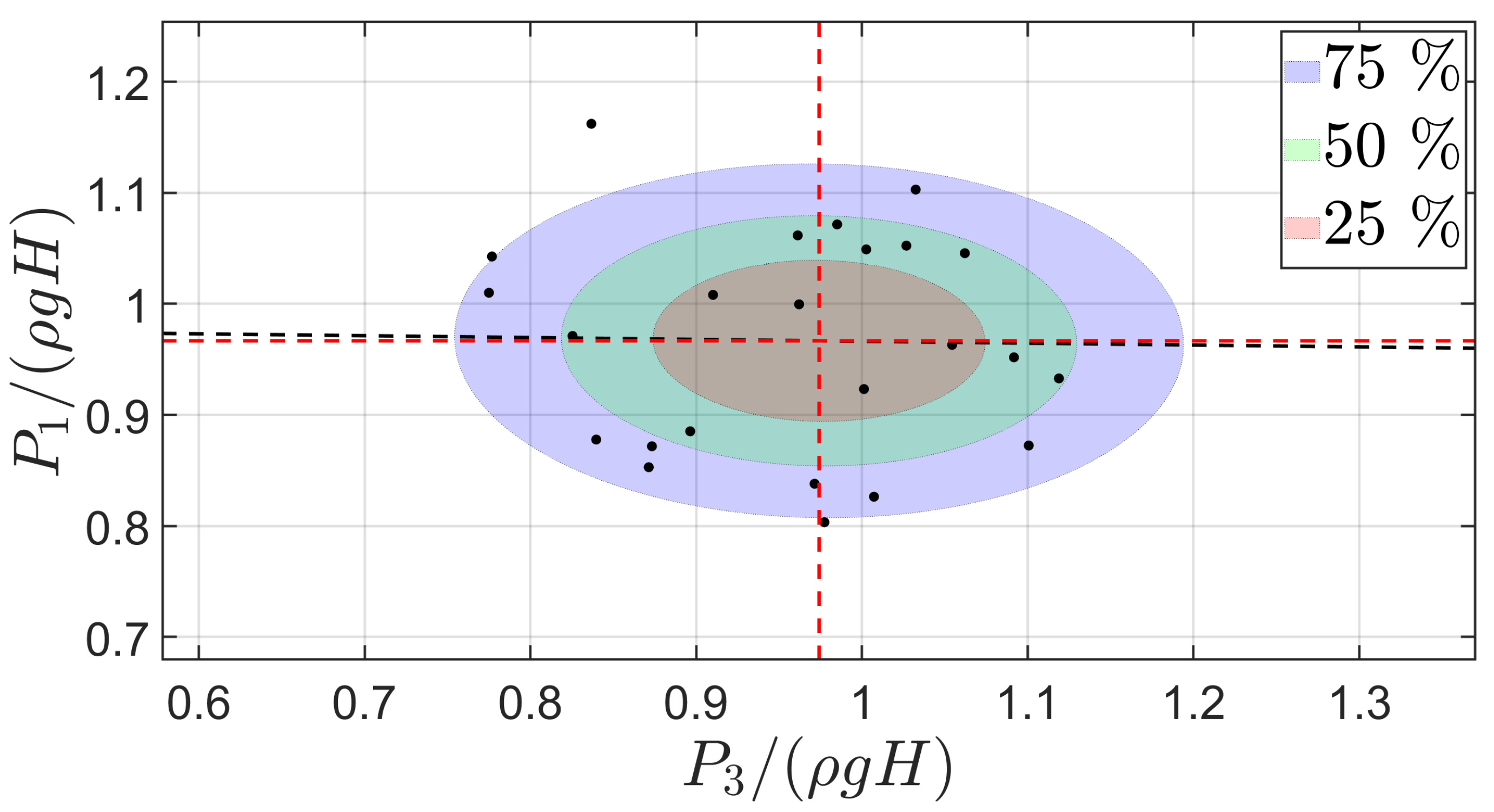

Figure 18.

Correlation between maximum pressure peak recorded by sensor 1 () and sensors 2 and 3 ( and ). Mean values are expressed by the red dotted lines. The black dotted line represents the linear fitting to the data. The 25%, 50% and 75% probability regions of the bivariate normal distribution of the sample has been plotted as reference.

Figure 18.

Correlation between maximum pressure peak recorded by sensor 1 () and sensors 2 and 3 ( and ). Mean values are expressed by the red dotted lines. The black dotted line represents the linear fitting to the data. The 25%, 50% and 75% probability regions of the bivariate normal distribution of the sample has been plotted as reference.

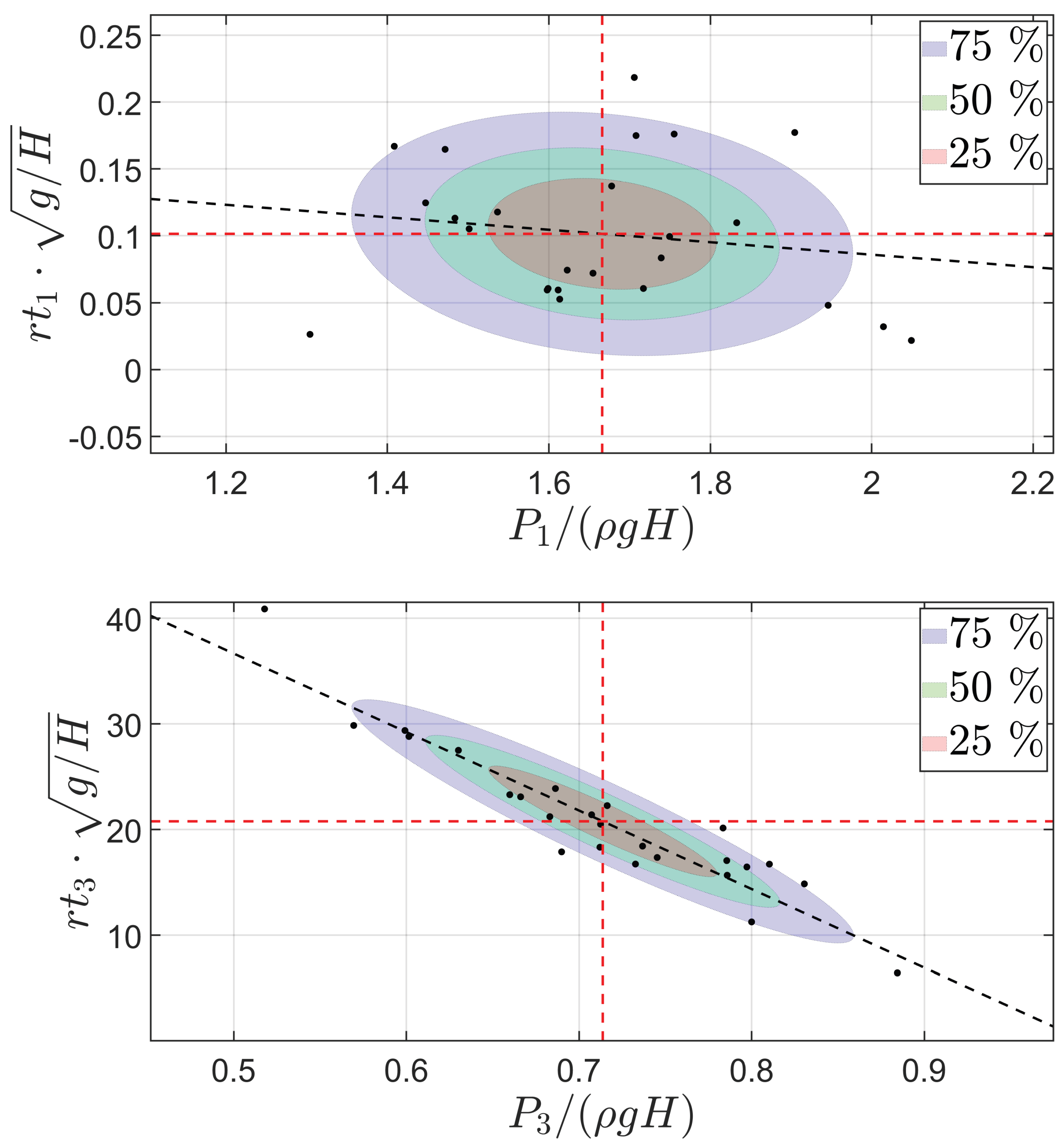

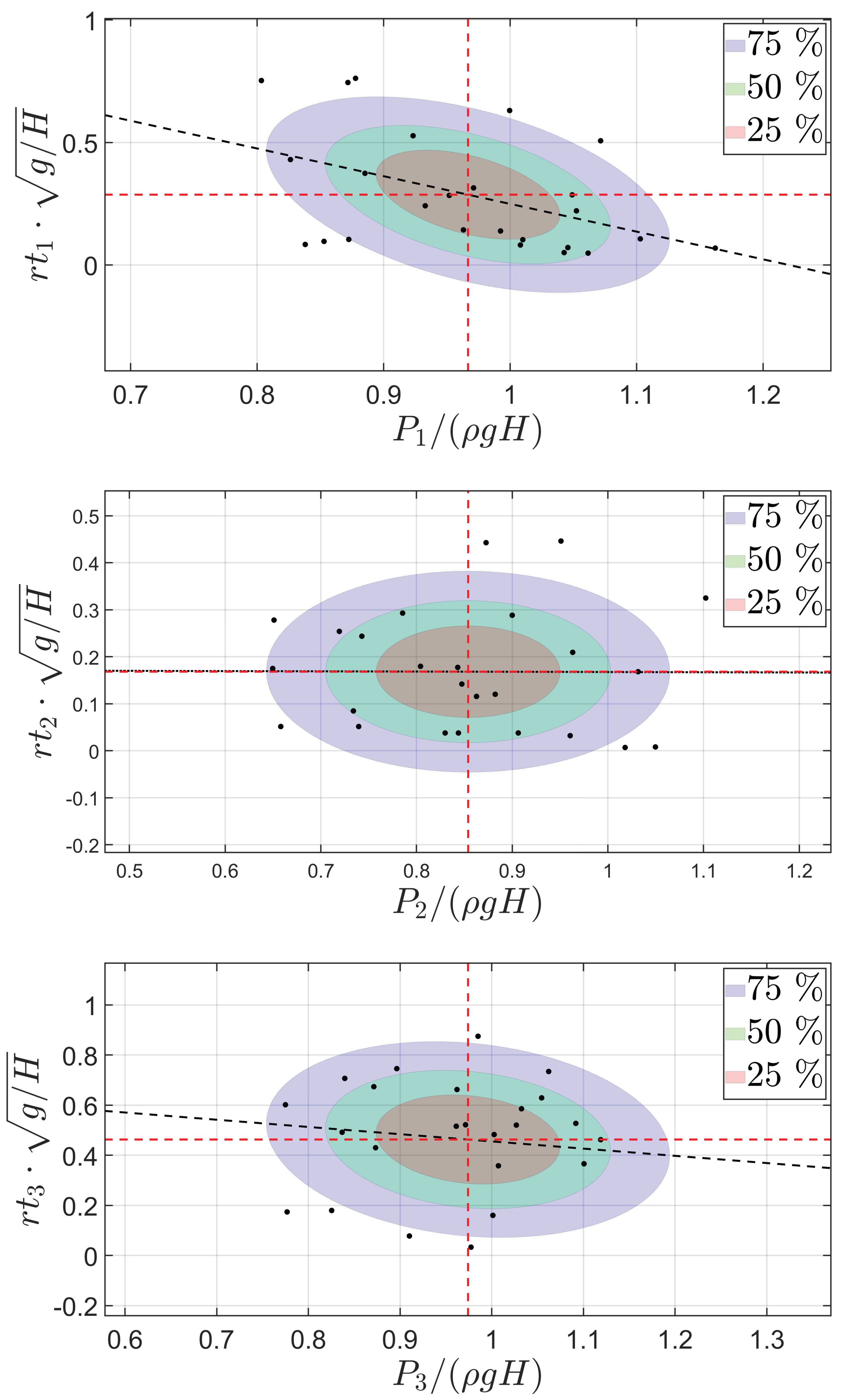

Figure 19.

Correlation between the rise time () and maximum pressure peak (P) of sensors 1 and 3. Mean values are expressed by the red dotted lines. The black dotted line represents the linear fitting to the data. The 25%, 50% and 75% probability regions of the bivariate normal distribution of the sample has been plotted as reference.

Figure 19.

Correlation between the rise time () and maximum pressure peak (P) of sensors 1 and 3. Mean values are expressed by the red dotted lines. The black dotted line represents the linear fitting to the data. The 25%, 50% and 75% probability regions of the bivariate normal distribution of the sample has been plotted as reference.

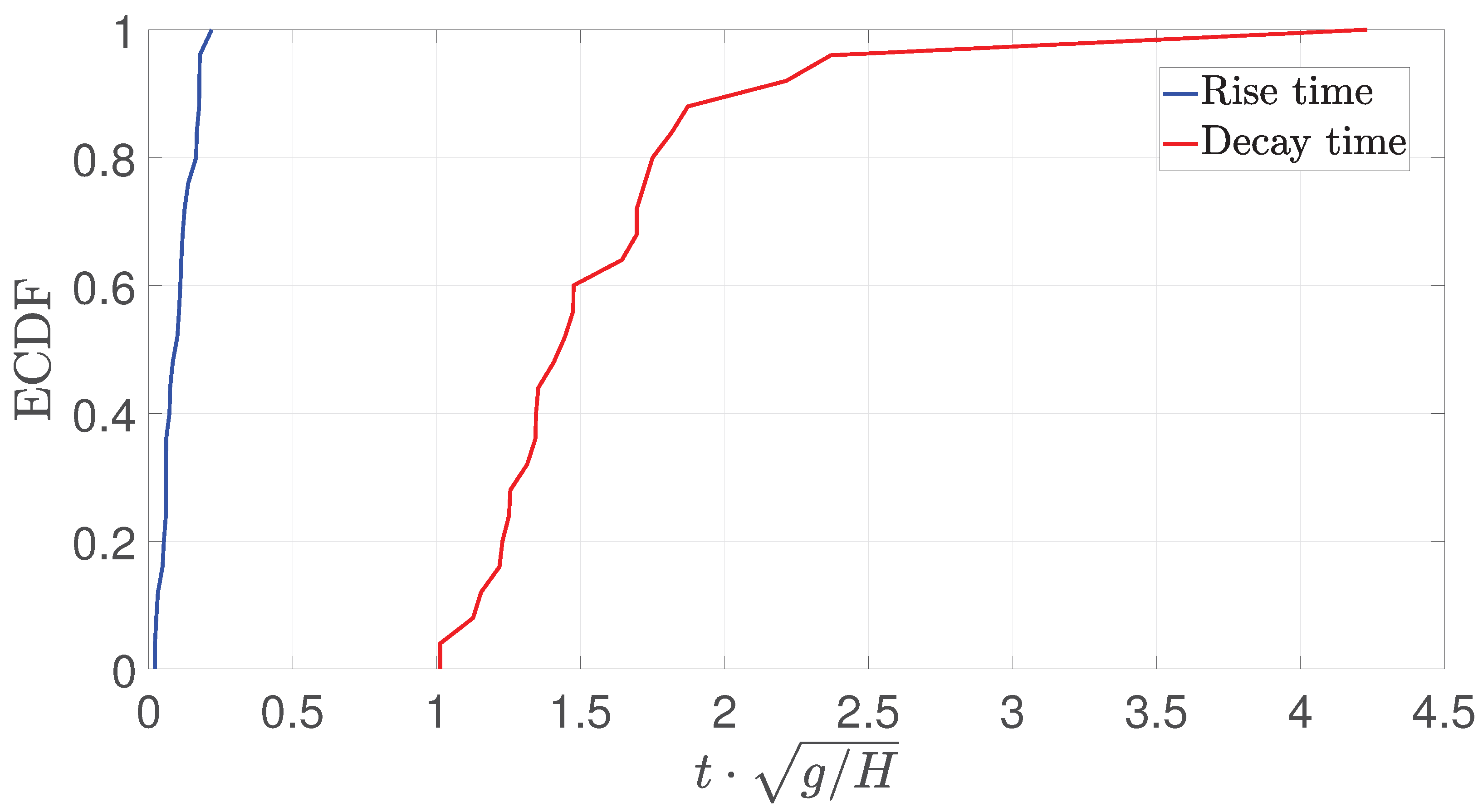

Figure 20.

ECDF of the rise and decay times for sensor 1 in the asymmetric configuration.

Figure 20.

ECDF of the rise and decay times for sensor 1 in the asymmetric configuration.

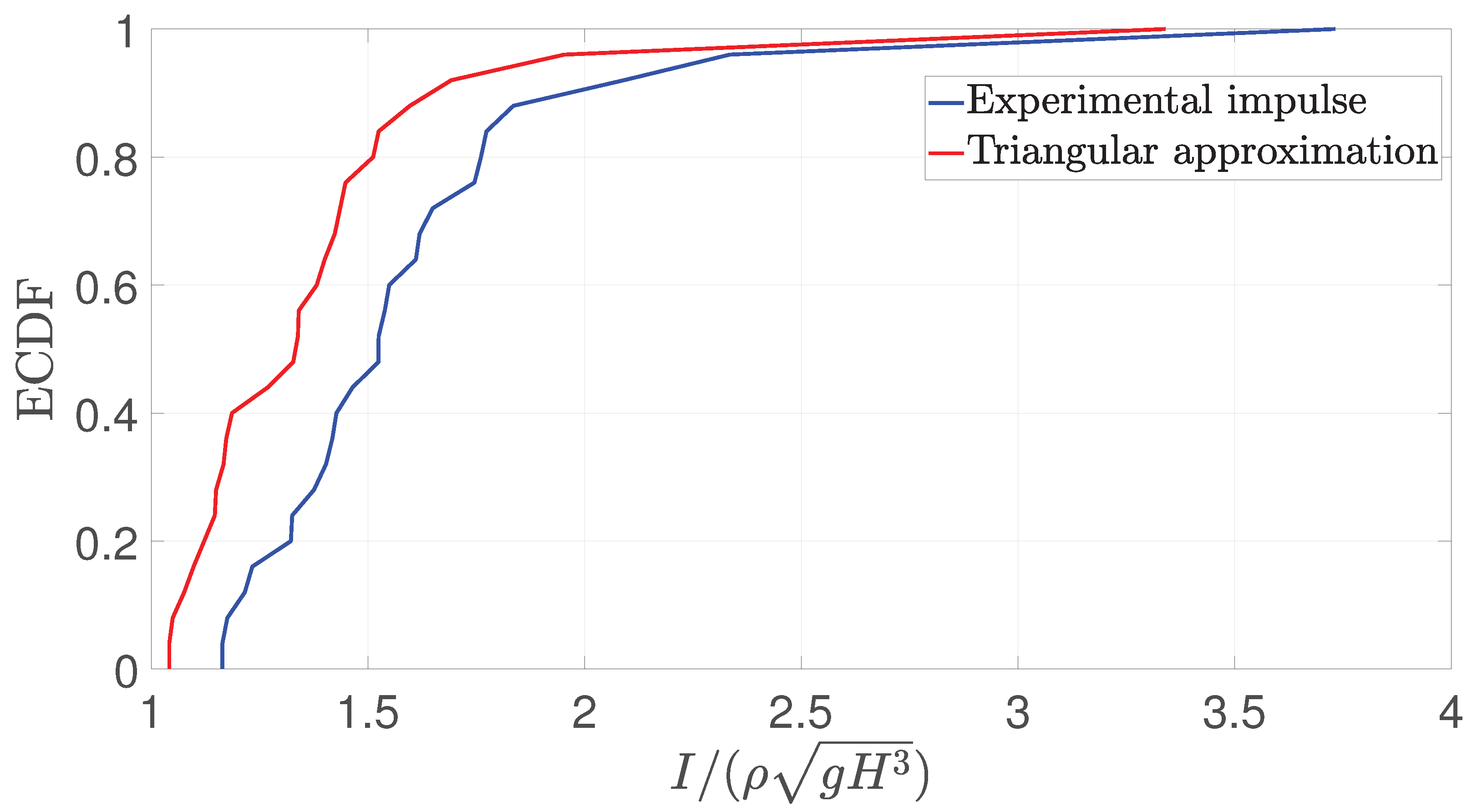

Figure 21.

ECDF of the pressure impulse (I) calculated from the pressure signals recorder by sensor 1. The red line represents the impulse calculated using the triangular approximation.

Figure 21.

ECDF of the pressure impulse (I) calculated from the pressure signals recorder by sensor 1. The red line represents the impulse calculated using the triangular approximation.

Figure 22.

Front view of the characteristic instants of a dam break experiment with the presence of an obstacle in the symmetric configuration.

Figure 22.

Front view of the characteristic instants of a dam break experiment with the presence of an obstacle in the symmetric configuration.

Figure 23.

Top view of the characteristic instants of a dam break experiment in the presence of an obstacle, symmetric configuration.

Figure 23.

Top view of the characteristic instants of a dam break experiment in the presence of an obstacle, symmetric configuration.

Figure 24.

Pressure measurements over time for sensors 1, 2 and 3 of a typical impact event in the symmetric configuration.

Figure 24.

Pressure measurements over time for sensors 1, 2 and 3 of a typical impact event in the symmetric configuration.

Figure 25.

Sensor 1 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the symmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

Figure 25.

Sensor 1 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the symmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

Figure 26.

Sensor 2 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the symmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

Figure 26.

Sensor 2 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the symmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

Figure 27.

Sensor 3 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the symmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

Figure 27.

Sensor 3 pressure time histories for the 25 repetitions in the symmetric flow configuration. The central black dotted line indicates de median, the upper and lower black dotted lines indicate the 97.5 % and 2.5 % percentiles respectively.

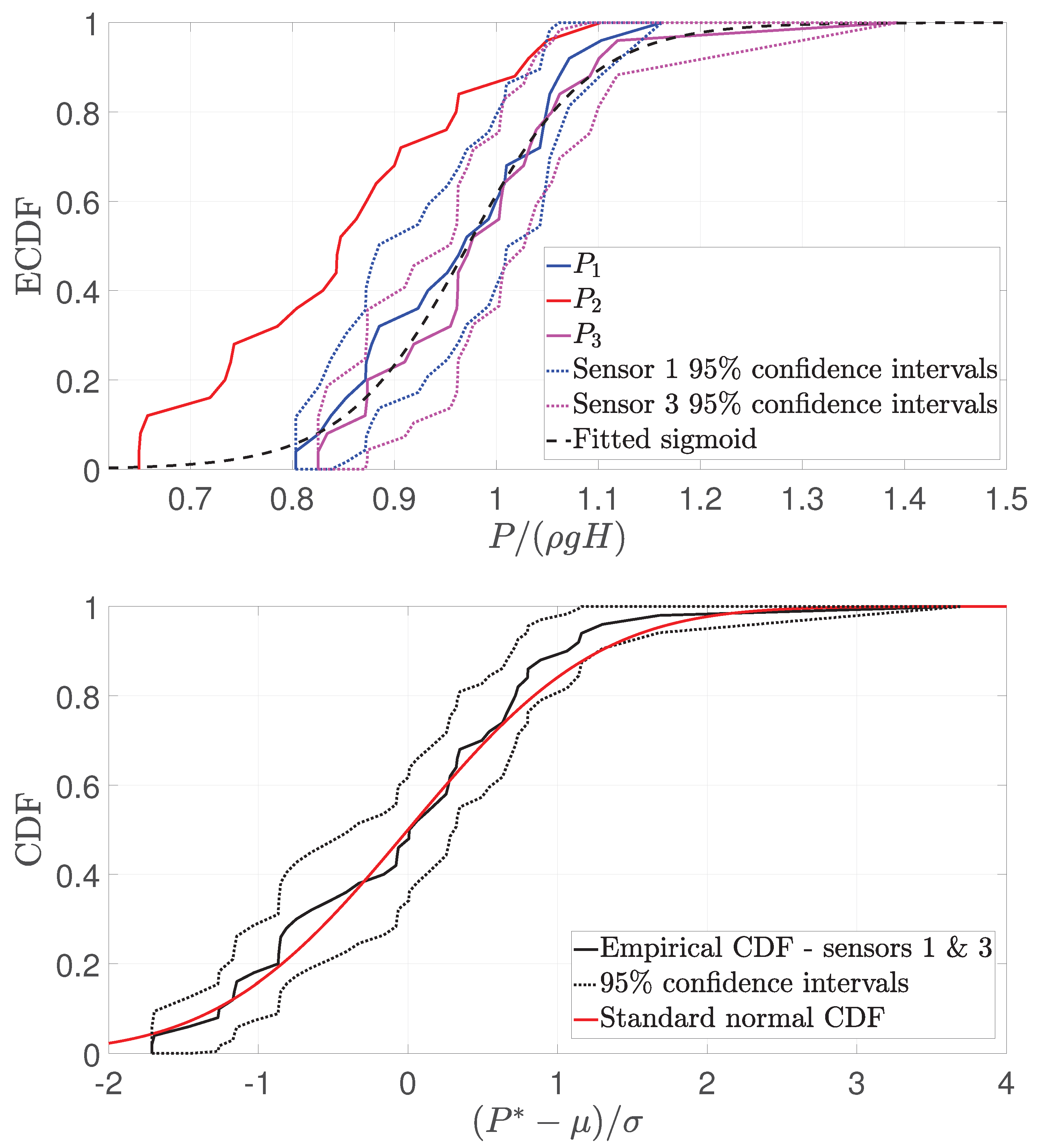

Figure 28.

Up: ECDF of the pressure peak P for sensors 1, 2 and 3 in the symmetric configuration. The 95% confidence intervals have been plotted in dotted color lines for sensors 1 and 3. The black dotted line represents the fitted sigmoid function to the data of sensors 1 and 3. Down: CDF of the normalized pressure peaks from sensors 1 and 3 along with the 95 % confidence intervals and the Standard normal CDF.

Figure 28.

Up: ECDF of the pressure peak P for sensors 1, 2 and 3 in the symmetric configuration. The 95% confidence intervals have been plotted in dotted color lines for sensors 1 and 3. The black dotted line represents the fitted sigmoid function to the data of sensors 1 and 3. Down: CDF of the normalized pressure peaks from sensors 1 and 3 along with the 95 % confidence intervals and the Standard normal CDF.

Figure 29.

Maximum pressure peaks of sensors 1, 2 and 3 and their repective medians for the conducted 25 tests in the symmetric flow configuration.

Figure 29.

Maximum pressure peaks of sensors 1, 2 and 3 and their repective medians for the conducted 25 tests in the symmetric flow configuration.

Figure 30.

Maximum pressure peak instants of sensors 1, 2 and 3 and their repective medians for the conducted 25 tests in the symmetric flow configuration.

Figure 30.

Maximum pressure peak instants of sensors 1, 2 and 3 and their repective medians for the conducted 25 tests in the symmetric flow configuration.

Figure 31.

Correlation between the maximum pressure peaks recorded by sensor 1 () and sensor 3 ().Mean values are expressed by the red dotted lines. The black dotted line represents the linear fitting to the data. The 25%, 50% and 75% probability regions of the bivariate normal distribution of the sample has been plotted as reference.

Figure 31.

Correlation between the maximum pressure peaks recorded by sensor 1 () and sensor 3 ().Mean values are expressed by the red dotted lines. The black dotted line represents the linear fitting to the data. The 25%, 50% and 75% probability regions of the bivariate normal distribution of the sample has been plotted as reference.

Figure 32.

Correlation between the rise time () and maximum pressure peak (P) of sensors 1, 2 and 3. Mean values are expressed by the red dotted lines. The black dotted line represents the linear fitting to the data. The 25%, 50% and 75% probability regions of the bivariate normal distribution of the sample has been plotted as reference.

Figure 32.

Correlation between the rise time () and maximum pressure peak (P) of sensors 1, 2 and 3. Mean values are expressed by the red dotted lines. The black dotted line represents the linear fitting to the data. The 25%, 50% and 75% probability regions of the bivariate normal distribution of the sample has been plotted as reference.

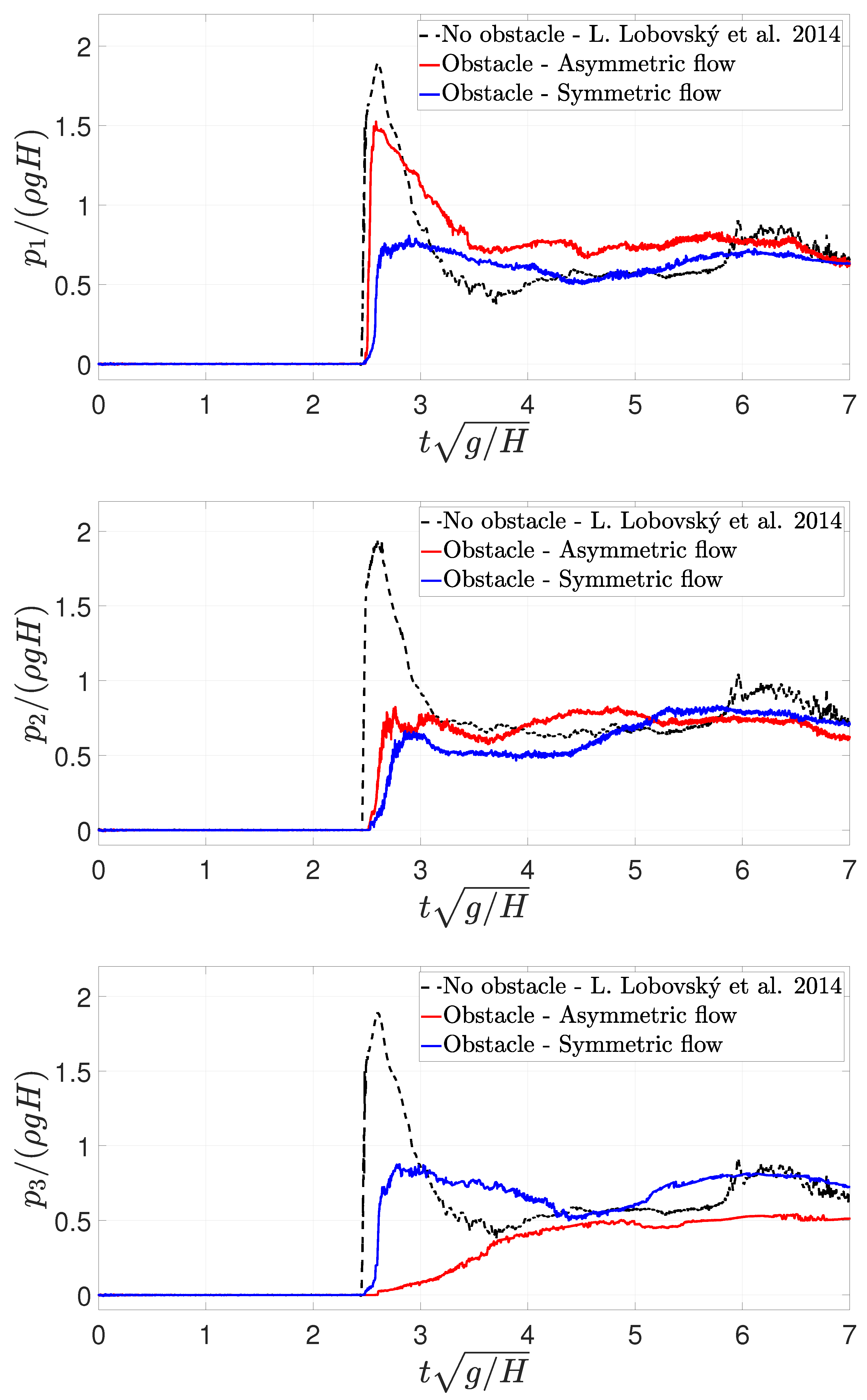

Figure 33.

Median of the pressure time histories for sensor 1 (left), 2 (centre) and 3 (right). Comparison between the data published in [

1] with no obstacle, asymmetric and symmetric configurations.

Figure 33.

Median of the pressure time histories for sensor 1 (left), 2 (centre) and 3 (right). Comparison between the data published in [

1] with no obstacle, asymmetric and symmetric configurations.

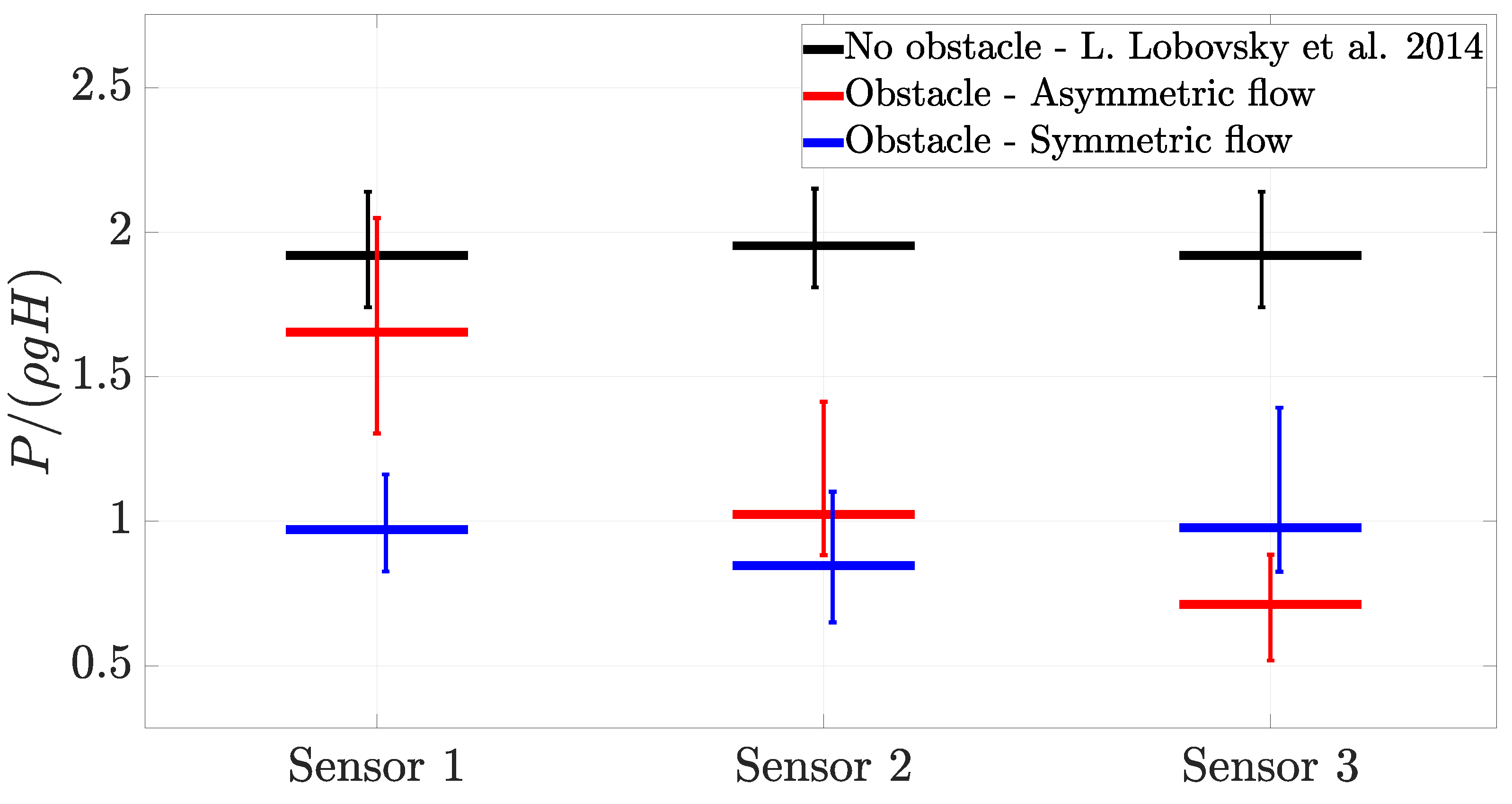

Figure 34.

Median of the maximum pressure peak for sensors 1, 2 and 3. Comparison between the data published in [

1] with no obstacle, asymmetric and symmetric configurations.The bars indicate the maximum and minimum recorded pressure peak values.

Figure 34.

Median of the maximum pressure peak for sensors 1, 2 and 3. Comparison between the data published in [

1] with no obstacle, asymmetric and symmetric configurations.The bars indicate the maximum and minimum recorded pressure peak values.

Table 1.

Mechanical properties of the tested water at 25 °C: density, dynamic viscosity and surface tension.

Table 1.

Mechanical properties of the tested water at 25 °C: density, dynamic viscosity and surface tension.

| Temperature [K] |

Density [kg/m3] |

Dynamic viscosity [Pa s] |

Surface tension [mN/m] |

| 298 |

997 |

|

72 |