1. Introduction

The circular economy is a model of production and consumption that involves sharing, leasing, reusing, repairing, refurbishing, and recycling existing materials and products to extend their lifespan (European Parliament, 2022). Although there are many definitions of the circular economy, they all share two key elements: (1) reducing, reusing, and recycling materials, and (2) systematic socio-economic change (Kirchherr, Reike & Hekkert, 2017). Overall, the circular economy has emerged as an alternative to the traditional linear economy (Buchmann-Duck & Beazley, 2020), aiming to separate economic growth from the use of primary resources (Buchmann-Duck & Beazley, 2020).

The circular economy model considers factors that can reduce waste and enable more precise monitoring of resource consumption (Kok et al., 2013). It has a positive impact on supply chains, thereby becoming a vital strategy in procurement and representing a supply chain innovation (Govindan & Hasanagic, 2018). Circular economy, as a new model of economic development, promotes the reuse (recycling) of materials, goods, and components to minimize waste generation to the greatest possible extent and to innovate the chain of production, consumption, distribution, and reuse of materials and energy (Ghisellini et al., 2018). Some studies examine the circular economy through the lens of supply chains. In this sense, it is emphasized that the circular economy has the potential to transform a range of existing challenges and create financial and economic value for society and the economy (Lacy et al., 2020).

Although there is increasing focus on circular economy models across Europe, there is limited empirical evidence from non-EU transition economies. Serbia, a candidate country aligning its waste management policies with EU standards, encounters structural and institutional obstacles that impede the implementation of circular practices, particularly in managing construction and demolition waste. Moreover, the transition toward a circular economy contributes directly to disaster risk reduction by minimizing waste accumulation, preventing environmental degradation, and promoting material resilience (Çetin & Kirchherr, 2025; Cvetković, Bošković, & Ocal, 2021; Cvetković & Filipović, 2017; Cvetković & Šišović, 2024a, 2024b; Cvetković, 2024; Grozdanić & Cvetković, 2024; Jevtić, Cvetković, Gačić, & Raonić, 2025; Nikolić, Cvetković, Renner, Cvijović, & Gačić, 2025; Pradhananga & Elzomor, 2023). In the context of disaster risk-informed practice, the circular management of construction and demolition waste enhances adaptive capacities of urban systems and supports sustainable recovery processes (Ayalew & Lema, 2025; Beli, Renner, Cvetković, Ivanov, & Gačić, 2025; Canete, Lisay, & Mahmud, 2025; Desalit, Duque, Edradan, Enciso, Enriquez, & Pan, 2025; Garba, Amuka, & Akaan, 2025; Ilić & Milašinović, 2025; Masaba, Aryatwijuka, Ntayi, & Bagire, 2025; Ojha, Bhattarai, & Devkota, 2025; Tushabe et al., 2025).

The circular economy has become one of the European Union's and many other nations' primary political goals. It is considered an important opportunity for redirecting the current economic model towards sustainable development (Ghisellini et al., 2018). In recent years, these models have been recognized by organizations in both the public and private sectors as a sustainable approach to implementing circular economy strategies (Lacy et al., 2020). The circular economy is thus highly emphasized in the construction sector due to its significant impact. This industry accounts for nearly 30% of all natural resource depletion and produces 25% of global solid waste (Benachio, Freitas & Tavares, 2020). Studies on the implementation of the circular economy in construction reveal that its principles are not entirely and comprehensively applied. Most countries discuss potential rather than actual practice of circular economic principles (Hossain, Ng, Antwi-Afari, & Amor, 2020). Unfortunately, there is a lack of studies from Serbia that help increase awareness and broaden scientific and professional understanding of applying circular economy principles in construction, especially in demolition.

The aim of this research is to present the potential for developing the circular economy in the construction industry and demolition waste sector in Serbia and to compare the results with those of other European countries. By presenting findings on current levels of this type of waste, the advantages of resource reuse will be highlighted, ultimately contributing to the development of the circular economy in construction materials and environmental protection.

The main objective of this study is to highlight the advantages and potential of reusing construction industry waste, which significantly contributes to the development of the circular economy in the Republic of Serbia. The specific research questions addressed in this paper are:

RQ1. Does the Republic of Serbia have the potential for developing a circular economy in the field of demolition waste?

RQ2. What are the annual quantities of such waste generated in the Republic of Serbia?

RQ3. How do these quantities compare to those in the European Union?

RQ4. What are the advantages and disadvantages of developing the circular economy in this field?

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a brief literature review with the most significant findings from studies in this area.

Section 3 outlines the research materials and methods used.

Section 4 presents the results and accompanying discussion. The final section is reserved for concluding considerations. This study offers one of the first systematic comparisons between Serbia and EU member states using harmonized industry data from the European Demolition Association (EDA). Leveraging this dataset provides new evidence on the maturity and challenges of circular practices in Serbia’s construction sector.

1.1. Literature Review

This section examines key academic and policy sources on the circular economy and its application to the management of construction and demolition waste (C&DW), with a focus on the European and Serbian settings. The current resource management approach needs to be upgraded to identify opportunities for increased resource efficiency better while still following environmentally friendly practices (Shi et al., 2017). This shift is already underway, with the circular economy concept playing a key role in it (Bastein et al., 2013). The European Commission Report (2006) suggested that the EU’s environmental policy should prevent or minimize waste through clean technologies to reduce the generation of all waste types. Developing efficient waste recycling opens new avenues for social, economic, and environmental gains, while also decreasing waste sent to landfills and considering other harmful disposal methods (Miranda et al., 2013).

On March 4, 2019, the European Commission released its latest report on the implementation of the Circular Economy Action Plan (Lin, 2020). This report emphasizes the key achievements within the plan aimed at promoting circular economy initiatives (Lin, 2020). The circular economy advocates biomimicry, ecosystem impact assessment, the bioeconomy, and renewable energy (Buchmann-Duck & Beazley, 2020). At the Smart City Institute, researchers identified two perspectives in this field: on the one hand, sustainable business models are seen as drivers of the shift toward sustainability (Bleus & Crutzen, 2020). On the other hand, policymakers and scientists view the circular economy as the most promising tool for reaching sustainability goals (Bleus & Crutzen, 2020). These authors (Bleus & Crutzen, 2020) therefore consider the circular economy model as essential in this context.

The European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT), which is part of the European Union and originated in the Horizon 2020 program, issued a directive that comprehensively addresses harmful substances in construction waste (Wahlström et al., 2018). This directive concentrates on hazardous materials regulated by the European Union, international agreements, or national laws. There is significant concern about compounds found in older construction materials, as their presence may limit the recycling of such waste (Wahlström et al., 2018). Current EU legislation already restricts the use of many substances in new construction products (Wahlström et al., 2018). Continuous industrial growth has generated large amounts of construction and demolition (C&D) waste, resulting in serious environmental and social issues (Du et al., 2020). Infrastructure projects generate substantial waste (Povetkin & Isaac, 2020). Managing construction waste is more challenging than managing other waste types because it often contains toxic materials. The use of recycling practices for construction and demolition (C&D) waste is highly important for reducing waste and conserving natural resources (Liu et al., 2020). At every stage of C&D waste recycling, environmental impacts are assessed (Liu et al., 2020).

In conventional buildings, the reuse and recycling of C&D waste at the end of the life cycle reduce overall impacts during the building’s life cycle and, to an even greater extent, mitigate impacts in all pre-use phases of materials (such as transportation and production of construction materials) (Ghisellini et al., 2018). If waste is sorted on-site, it can be reused in the construction of new buildings, resulting in financial savings on transport to landfills and a reduction in environmental impacts caused by exhaust emissions from waste transport through settlements.

In all market scenarios for C&D waste recycling, environmental impacts are examined, given that governments' primary incentive is to improve C&D waste recycling and minimize environmental impacts (Liu et al., 2020). The profit of recyclers decreases in proportion to the rate of waste disposed of and the investment cost coefficient. In contrast, recyclers may achieve higher profits when their capacity is insufficient to handle the C&D waste they generate (Liu et al., 2020). According to Liu et al. (2020), if the investment cost coefficient is relatively higher, a “win-win” situation can be achieved, benefiting both waste producers and recyclers. Among the two C&D waste recycling market scenarios, the optimal scenario is the one that offers greater environmental benefits.

In Serbia, the application of circular economy principles in construction remains underdeveloped. Although estimates indicate that up to 80% of construction and demolition waste could be reused, most waste is still disposed of in landfills (Eraković & Mladenović-Ranisavljević, 2019). Approximately 5 m³ of construction waste per site is generated annually, while over 3,500 landfills operate nationwide, many of them unmanaged or improperly regulated (Čepić et al., 2022). The situation is particularly critical after disasters such as floods, when waste volumes rise sharply, revealing weaknesses in local recovery and recycling systems.

Serbia’s Waste Management Strategy officially bans uncontrolled disposal and outlines legal procedures for waste classification and processing (Stanojlović et al., 2016). However, there is a significant implementation gap caused by limited funding, inadequate monitoring, and a shortage of specialized infrastructure (Cvetković et al., 2023; Cvetković et al., 2025). The lack of comprehensive data on C&DW composition and flows hampers evidence-based policymaking (Karanović, 2021). These systemic issues show that, although legal frameworks exist, their practical application remains limited, leaving Serbia behind EU standards and circular-economy benchmarks. To comply with the EU Waste Framework Directive and the European Green Deal, Serbia needs to strengthen institutional capacity, develop financial mechanisms, and implement education programs that encourage sustainable construction and resource recovery.

Incorporating disaster risk-informed principles into circular practices could also boost urban resilience, making reconstruction after disasters more efficient, environmentally friendly, and low-waste. The literature indicates that, while the circular economy is a major driver of sustainability across Europe, its deployment in the construction sector—especially in transition economies like Serbia—is still incomplete. Closing this gap requires harmonized data, enhanced institutional coordination, and the integration of circular-economy and disaster-risk management strategies to improve environmental protection and societal resilience.

2. Materials and Methods

This study relies on primary data collected through ongoing research carried out by the European Demolition Association (EDA). The Serbian Association for Demolition, Decontamination, and Recycling of Construction Materials provided data for Serbia. For comparison, the study uses data from research conducted in 2019, citing 2018. Data for European countries are publicly available, while Serbian data are accessible only to the study's authors. The research was conducted using an electronic questionnaire with questions organized into eight distinct sections.

The first section aimed to identify the companies' main activities. They were categorized based on whether they operated as contractors performing demolition in urban (city) environments; contractors performing demolition in industrial settings (noting that urban demolition typically involves higher environmental protection standards); contractors involved in both demolition and waste management and recycling activities, where recycling may occur on-site to enable reuse—supporting circular economy principles and cost savings. Another group included general contractors handling all types of construction-related tasks. Further categorization distinguished whether companies engaged in design, construction, or other services.

The second section focused on company revenues in 2018 from all activities. Responses were grouped into categories: less than 1 million euros, 1 to 5 million euros, 5 to 15 million euros, 15 to 30 million euros, 30 to 50 million euros, and over 50 million euros. These data provide insight into revenue levels relative to the scope of activity (demolition, decontamination, recycling), indicating the extent to which these practices are applied.

The third section specifically examined revenues from demolition activities (urban, industrial, waste removal). It aimed to determine the share of demolition revenue, categorized into: less than 25%, 25% to 50%, 50% to 70%, or more than 75%. This highlights the potential and profitability of demolition work. The fourth section assessed the scale of companies, classifying them as large, medium, or small contractors. The fifth section analyzed revenue changes in 2018 compared to 2017 from demolition-related activities. Responses were grouped into five categories: growth of 15% or more, moderate growth of 5% to 15%, stable within +/-5%, moderate decline of -5% to -15%, and a significant decline of -15% or more. It emphasizes the benefits of demolition, including the provision of renewable resources through proper waste disposal and recycling. The sixth section examined companies whose revenues relied on decontamination activities, especially asbestos and other hazardous substances. The goal was to determine the share of revenue from these activities, which can be profitable while ensuring proper disposal of hazardous waste to protect the environment and public health. Response options included: over 50%, 26% to 50%, 11% to 25%, and under 10%.

The seventh section covered income from waste management activities, including sorting, transportation, and recycling. Responses were grouped into four categories: over 50%, 26% to 50%, 11% to 25%, and under 10%. Its purpose was to highlight the profitability of these activities, which are essential for a circular economy and waste reuse. The eighth section asked companies to share their outlook for 2019 (as estimated in 2018), with response categories including growth over +15%, moderate growth between +5% and +15%, stability between -5% and +5%, moderate decline between 5% and -15%, and decline of more than 15%. The questionnaire was completed by members of the European Association for Demolition, Decontamination, and Recycling of Construction Materials in both Serbia and the European Union. In the EU, companies were surveyed at the country level, with results presented cumulatively for the entire Union. The surveyed companies engaged in demolition, recycling, or construction. The reason for targeting these businesses is that their activities extend beyond construction itself, covering demolition, decontamination, and recycling—key processes in the circular economy. This approach promotes environmental safety by following demolition with waste sorting, decontamination, and recycling, enabling on-site reuse. Consequently, the total waste disposed of in designated facilities is significantly reduced.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Data Obtained in the Republic of Serbia

The 2019 Industrial Report (EDA, 2019b) analyzed data from 2018. In Serbia, companies reported their main activities: 13% were urban demolition contractors, 6% focused on industrial demolitions, 6% handled waste management and recycling, 31% were general demolition firms performing all types of work, 31% engaged in design and project management for demolitions, while 13% noted their activities as "other" related to demolition or construction waste management as part of their core business.

From this, it is clear that 31% of companies performed a full range of services, and another 31% specialized in design and project management for demolitions. Compared to 2017 and 2018, 2019 saw a notable increase in companies offering broader service scopes. In 2018, the revenue distribution was as follows: 50% earned less than 1 million euros, 13% earned between 1 and 5 million euros, 19% earned between 5 and 15 million euros, and 19% earned between 30 and 50 million euros, across all activities. When asked, “What percentage of your revenue came solely from demolition activities, including urban, industrial, and waste removal?" 69% reported less than 25%, 19% reported between 25% and 50%, and 13% reported more than 75% of their revenue from demolition activities. This indicates limited capacity in waste processing and removal. With 13% of companies identifying as large contractors, 50% as medium-sized, and 38% as small, Serbian companies show potential to become leading contractors. While all surveyed companies in previous years were classified as small, in 2019, 50% identified as medium-sized, and 13% as large contractors capable of managing entire projects—significant progress for Serbian firms.

Analysis of revenue growth in 2018 compared with 2017 from demolition-related activities showed that 27% of companies reported significant growth (+15%), 13% reported moderate growth (+5% to +15%), 40% indicated stability (-5% to +5%), while 20% reported a slight decline (-5% to -15%). In terms of revenues from decontamination activities (particularly asbestos and other hazardous substances), 7% of companies reported that more than 50% of their revenues came from these activities, 13% between 11% and 25%, while the majority achieved only about 10% of their revenues from decontamination. For waste management activities (sorting, transport, recycling), the reported revenues were as follows: more than 50% of revenues in 13% of companies, between 26% and 50% in 7% of companies, and less than 10% in 80% of companies.

When asked, “Compared with 2018, what are your business expectations for 2019 regarding demolition-related activities?”, 7% of companies expected significant growth of more than 15%, 27% expected moderate growth (+5% to +15%), 53% anticipated stable business (+/-5%), while 13% expected a slight decline (-5% to -15%).

3.2. Comparative Overview of Serbia and the European Union

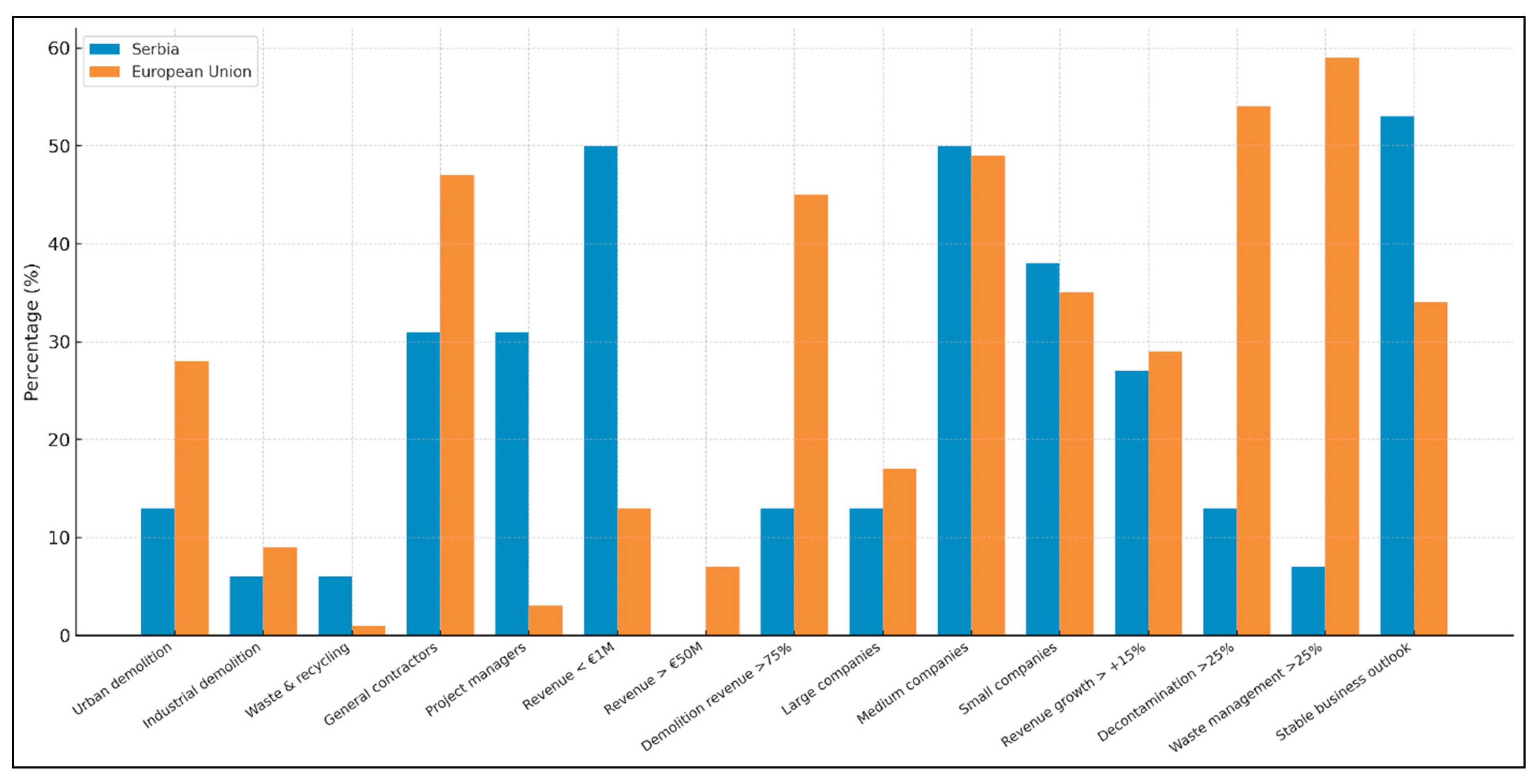

In 2018, subcontractors reported their demolition project involvement as follows: over 75% of projects was handled by 20% of companies (compared to 14% in the EU), 51-75% involvement was reported by 13% of companies (EU: 20%), 26-50% by 7% (EU: 24%), and less than 25% by 60% (EU: 41%). Significant differences between Serbian and European companies are apparent. See

Table 1 for details.

Figure 1.

Comparative Overview of Construction and Demolition Waste Sector Indicators: Republic of Serbia vs. European Union.

Figure 1.

Comparative Overview of Construction and Demolition Waste Sector Indicators: Republic of Serbia vs. European Union.

4. Discussion

This study contributes to understanding and advancing the circular economy, particularly in the context of construction and demolition waste (C&DW) management in the Republic of Serbia. The comparative analysis between Serbia and EU member states reveals both progress and persistent gaps in the maturity of circular practices. Serbian companies are increasingly engaging in diversified demolition and recycling activities, with 50% identifying as medium-sized and 13% as large contractors—an encouraging sign of market consolidation and professional growth. However, the data also indicate that circular processes remain marginal in business operations: 69% of Serbian companies earn less than 25% of their revenue from demolition-related activities, and 80% derive less than 10% of their revenue from waste management or recycling. In contrast, almost half of EU companies generate more than 75% of their income from such activities, reflecting higher integration of circular models into mainstream construction economies.

These findings highlight that Serbia’s circular economy transition is still in its formative stage. Structural limitations—including the lack of specialized recycling facilities, insufficient financial incentives, and incomplete regulatory enforcement—constrain the broader adoption of CE principles. Moreover, fragmented data on waste flows and the absence of a fully developed secondary materials market limit the operationalization of CE policies. These challenges are characteristic of many transition economies, where the alignment of institutional frameworks with EU directives remains ongoing. Addressing these issues will require a coordinated policy approach that combines regulatory enforcement, infrastructure investment, and capacity building among demolition and recycling enterprises.

From a disaster risk-informed perspective, the findings underscore the strategic importance of CE integration for enhancing national resilience (Andrews, Ccp, Pmp, PhD, & Dpm, 2022; Çetin & Kirchherr, 2025; Farhanrika, Sarpono, Kusuma, & Widodo, 2023; Jayasinghe et al., 2024; Pradhananga & Elzomor, 2023). Effective management of construction and demolition waste can reduce post-disaster debris accumulation, improve the safety and sustainability of reconstruction, and decrease environmental and health risks associated with hazardous materials (Banias et al., 2022; Cook & Velis, 2020; Cook, Velis, & Black, 2022; Islam, Sandanayake, Muthukumaran, & Navaratna, 2024; Lee, Chang, & Lee, 2024; Shajidha & Mortula, 2025). In disaster recovery scenarios, circular approaches—such as on-site material sorting, reuse of debris, and recycling of building components—can accelerate recovery timelines and reduce economic losses (Al-Zrigat, 2020; Jalloul, Choi, Derrible, & Yeşiller, 2022). Consequently, integrating CE principles into disaster risk management frameworks supports both sustainable reconstruction and long-term urban resilience (Caro et al., 2023; Minunno, O’Grady, Morrison, Gruner, & Colling, 2018; Regattieri, Gamberi, Bortolini, & Piana, 2018; Ruiz, Ramón, & Domingo, 2020).

It must be acknowledged that emerging technologies play a pivotal role in developing circular economy frameworks that integrate waste valorization, sustainable energy generation, and regional climate adaptation strategies. Moreover, realizing such integration requires more than technical coordination; it depends on a collaborative social process involving negotiation, knowledge sharing, and collective learning among policymakers, businesses, and citizens (Dialog Bioökonomie, 2023; OECD, 2020; Kaukab, 2023). Targeted risk communication raises awareness of opportunities and risks, supports behavioral change, and fosters trust and participation (WHO, 2025; Renn, 2017). However, knowledge alone rarely leads to action (Luick et al., 2025). Behavioral responses depend on trust in intermediaries, perceived self-efficacy, and the framing of risks and benefits (Hauck, 2023).

A systematic framework (Graf et al., 2025) for planning risk communication strategies to enable the development of circular economies needs to be applied effectively to foster individual and collective capacities to act sustainably. At the policy level, this research offers practical insights for the Ministry of Environmental Protection of the Republic of Serbia and local authorities tasked with implementing waste management strategies. The results suggest that policy instruments should move beyond legal compliance toward market stimulation, for example, through tax incentives for recycling, green public procurement, and digital traceability systems for C&DW flows. Institutional partnerships among public agencies, universities, and private companies can help bridge the gap between research and application by driving innovation in waste-reuse technologies and business models.

At the industry level, the study can support construction and demolition companies by highlighting tangible benefits of circular economy practices: reduced operational costs through material recovery, lower disposal expenses, and improved competitiveness through sustainable branding. Demonstrating economic viability is key to motivating companies to adopt CE practices voluntarily, rather than solely through regulatory pressure.

Finally, from an academic and research standpoint, this study provides a foundational baseline for further exploration of circular economy implementation in Serbia and comparable contexts. Future research could focus on longitudinal monitoring of CE adoption, quantifying environmental benefits (e.g., CO₂ reduction, resource efficiency), and integrating CE indicators into national disaster risk reduction policies. By linking circularity with risk-informed planning, Serbia has the opportunity to position its construction sector not only as an economic driver but also as a cornerstone of environmental and societal resilience in line with the European Green Deal and Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030).

5. Conclusions

The results from the European Demolition Association (EDA) Industrial Report provide valuable insights for the demolition sector. These findings support the growth of the circular economy and environmental protection efforts. To improve reliability and sustainability in Serbia, investment in education, training, and capacity-building for workers and waste producers is essential, aligned with European standards and practices. Currently, this industry is still emerging, and formal vocational schools for related professions do not yet exist. Enhancing education among waste producers could significantly boost the development of the circular economy in demolition waste management. The main benefit would be a positive impact on Serbia’s national budget by preserving resources and supporting a well-developed construction sector. Although Serbia is advancing in this direction, the EU shows higher operational results and participation, as reflected in company forecasts. This study adds to scientific knowledge about the circular economy and offers practical insights for improving circular practices in the construction material sector in Serbia. The recommended waste management procedures can result in environmentally safe, economically feasible, and operationally efficient outcomes. Limitations include the focus on data from 2019, leaving gaps regarding developments over the past three years. It is also assumed that not all companies engaged in these activities are captured in the report, raising questions about how future, more comprehensive studies could better assess the sector’s potential. Future research will aim to answer these questions and develop practical solutions to strengthen circular economy practices in construction and demolition.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific–Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management, Belgrade, Serbia (

https://upravljanje-rizicima.com/, accessed October 13, 2025); the International Institute for Disaster Research, Belgrade, Serbia (

https://idr.edu.rs/, accessed October 12, 2025); and ProSafeNet — The Global Hub for Safety, Security, Risk & Emergency Professionals & Scientists, Belgrade, Serbia (

https://prosafenet.com/, accessed October 13, 2025).

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the use of Grammarly Premium and ChatGPT 4.0 in the process of translating and improving the clarity and quality of the English language in this manuscript. The AI tools assisted in language enhancement but were not involved in developing the scientific content. The authors take full responsibility for the originality, validity, and integrity of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Zrigat, Z. M. The emergency architecture: Reuse and recycle materials after disasters. Journal of Engineering and Technology for Industrial Applications 2020, 6, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, T.; Rapp, R.; Ewakil, E.; Dietz, J. E.; Baroudi, S. Disaster response using the circular economy: A timeline review of the literature. Journal of Emergency Management 2022, 20(4), 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, N. A.; Lema, A. T. Conflict risk monitoring for conflict prevention in Ethiopia: The case of Ataye Town, North Shewa, Amhara Region. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2025, 7(1), 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banias, G.; Karkanias, C.; Batsioula, M.; Melas, L.; Malamakis, A.; Geroliolios, D.; Spiliotis, X. Environmental assessment of alternative strategies for the management of construction and demolition waste: A life cycle approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastein, T.; Roelofs, E.; Rietveld, E.; Hoogendoorn, A. Opportunities for a circular economy in the Netherlands. TNO Report commissioned by the Netherlands Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beli, A.; Renner, R.; Cvetković, V. M.; Ivanov, A.; Gačić, J. A cross-national study of disaster risk management: Strengths and weaknesses in Bulgaria, Romania, and Albania with reflections on Serbia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2025, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benachio, G. L. F.; Freitas, M. D. C. D.; Tavares, S. F. Circular economy in the construction industry: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 260, 121046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleus, H.; Crutzen, N. Sustainable business models for circular economy in urban ecosystem. Smart City Institute, Research Center. 2020. Available online: https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/248459.

- Buchmann-Duck, J.; Beazley, F. K. An urgent call for circular economy advocates to acknowledge its limitations in conserving biodiversity. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 727, 138602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañete, R. M.; Lisay, S. K.; Mahmud, M. N. S. Project DINGGIN: Empowering communities through risk-based and inclusive cash transfer in disaster-prone areas in Bangladesh and the Philippines. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2025, 7(1), 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, D.; Lodato, C.; Damgaard, A.; Cristóbal, J.; Foster, G.; Flachenecker, F.; Tonini, D. Environmental and socio-economic effects of construction and demolition waste recycling in the European Union; Science of the Total Environment, 2023; p. 168295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čepić, Z.; Bošković, G.; Ubavin, D.; Batinić, B. Waste-to-energy in transition countries: Case study of Belgrade (Serbia). Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 2022, 31(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, S.; Kirchherr, J. The Build Back Circular Framework: Circular economy strategies for post-disaster reconstruction and recovery; Circular Economy and Sustainability., 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.; Velis, C. Construction and demolition waste management: A systematic review of risks to occupational and public health; Open Science Framework (OSF)., 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.; Velis, C.; Black, L. Construction and demolition waste management: A systematic scoping review of risks to occupational and public health. Frontiers in Sustainability 3 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culleri, J.; Series, C. Recycling: Technological systems, management practices and environmental impact; New York, NY; Nova Science Publishers, 2013; ISBN 978-1-62618-284-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, V. M. Disaster Resilience: Guide for Prevention, Response, and Recovery; Belgrade; Scientific-Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, V. M.; Šišović, V. Understanding the Sustainable Development of Community (Social) Disaster Resilience in Serbia: Demographic and Socio-Economic Impacts. Sustainability 2024, 16(7), 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V. M.; Aleksov, B.; Renner, R.; Gаčić, J.; Ivanov, A.; Milašinović, S. Community-based disaster risk reduction: Overcoming barriers to build stronger communities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2023, 7(2), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, V. M.; Lipovac, M.; Renner, R.; Stanarević, S.; Raonić, Z. A Predictive Framework for Understanding Multidimensional Security Perceptions Among Students in Serbia: The Role of Institutional, Socio-Economic, and Demographic Determinants of Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17(11), 5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Filipović, M. Koncept otpornosti na katastrofe [Concept of disaster resilience]. Ecologica 2017, 24(87), 557–563. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, V.; Šišović, V. Community disaster resilience in Serbia; Belgrade; Scientific-Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management, 2024a. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, V.; Bošković, N.; Ocal, A. Individual citizens' resilience to disasters caused by floods: A case study of Belgrade. 5th International Symposium on Natural Hazards and Disaster Management, Bursa Technical University, Bursa, Turkey, 24–25 October; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Desalit, P.; Duque, G. B.; Edradan, T. M.; Enciso, K. H.; Enriquez, M. R.; Pan, W. K. M. Predictors of disaster response self-efficacy among adult residents in selected highly dense barangays in Tondo, Manila. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2025, 7(1), 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Feng, Y.; Lu, W.; Lingkai, K.; Yang, Z. Evolutionary game analysis of stakeholders’ decision-making behaviours in construction and demolition waste management. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraković, Z.; Mladenović-Ranisavljević, I. Challenges of construction and demolition waste management in the southern Serbia region. Knowledge – International Journal 2019, 35(3), 855–859. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on implementation of the Community waste legislation (COM 2006, 406 final, Brussels). 2006. Available online: http://www.ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/reporting/index.htm.

- European Demolition Association (EDA). Yearbook 2019; Retrieved from European Demolition Association database, October 2019a. [Google Scholar]

- European Demolition Association (EDA). Industry report 2019; Retrieved from European Demolition Association database, October 2019b. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Circular economy: Definition, importance and benefits. 2022. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/economy/20151201STO05603/circular-economy-definition-importance-and-benefits.

- Farhanrika, N. L.; Sarpono, S.; Kusuma, K.; Widodo, P. Advancing resilience and fostering sustainable development through strategic investments in cutting-edge technology and innovative methodologies for disaster risk reduction, as seen in Japan's experiences. International Journal of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences 2023, 3(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin-Johnson, E.; Figge, F.; Canning, L. Resource duration as a managerial indicator for circular economy performance. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 133, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajović, A.; Ćurčić, S. The use of forest fruits as one of the factors of the quality of human life. In the 1st International Conference on Quality of Life; Center for Quality, Faculty of Engineering, University of Kragujevac, 2016; pp. 195–200. ISBN 978-86-6335-033-5. [Google Scholar]

- Garba, T. M.; Amuka, I.; Akaan, R. Female gender empowerment, individualism, collectivism, and resilience: A comparative study in the context of disaster risk management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2025, 7(1), 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Ripa, M.; Ulgiati, S. Exploring environmental and economic costs and benefits of a circular economy approach to the construction and demolition sector: A literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 178, 618–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. K. Circular economy: Global perspective; Singapore; Springer Nature, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Hasanagic, M. A systematic review on drivers, barriers, and practices towards circular economy: A supply chain perspective. International Journal of Production Research 2018, 56(1–2), 278–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, J.; Renner, R.; Klebel, T. Bridging Warning and Adaptation: Addressing Risk Communication Strategies for Short-Term Natural Hazard Warnings and Long-Term Risk Adaptation; A Scoping Review: Preprint, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Grozdanić, G.; Cvetković, V. M. Exploring multifaceted factors influencing community resilience to earthquake-induced geohazards: Insights from Montenegro; Belgrade; Scientific-Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, M. Zeitenwende im Wald: Klimawandelanpassung durch Ersatzbaumarten – eine langfristige Lösung? 2262 KB 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. U.; Ng, S. T.; Antwi-Afari, P.; Amor, B. Circular economy and the construction industry: Existing trends, challenges, and a prospective framework for sustainable construction. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 130, 109948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, V.; Milašinović, M. Declination of the Strategic Compass: Transatlantic elites, German leadership, and the future of European security. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2025, 7(1), 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Sandanayake, M.; Muthukumaran, S.; Navaratna, D. Review on sustainable construction and demolition waste management—Challenges and research prospects. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalloul, H.; Choi, J.; Derrible, S.; Yeşiller, N. Toward sustainable management of disaster debris: Three-phase post-disaster data collection planning. Construction Research Congress; 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, G. Y.; Perera, T.; Perera, H. A. T. N.; Karunarathne, H. D.; Manawadu, L.; Weerasinghe, V. P. A.; Haigh, R. A systematic literature review on integrating disaster risk reduction (DRR) in sustainable tourism (SusT): Conceptual framework for enhancing resilience and minimizing environmental impacts. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevtić, M.; Cvetković, V. M.; Gačić, J.; Raonić, Z. Factors of vulnerability and resilience of persons with disabilities during disasters: Challenges and strategies for inclusive risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2025, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanović, N. CO₂ emission assessment of construction and waste materials in the context of circular economy: Case study of project Corridor X. Acta Technica Corviniensis – Bulletin of Engineering 2021, 14(3), 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kaukab, R. S. Circular economy and trade agreements: Towards developing a framework for linkage. Global and regional order; Bonn, Germany; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. S. Current international economic outlook. Ecodate 2020, 33(3), 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, L.; Wurpel, G.; Ten Wolde, A. Unleashing the power of the circular economy. Report by IMSA Amsterdam for Circle Economy; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lacy, P.; Long, J.; Spindler, W. The circular economy handbook: Realizing the circular advantage; London, UK; Springer Nature, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Chang, H.; Lee, J. Construction and demolition waste management and its impacts on the environment and human health: Moving toward sustainability enhancement; Sustainable Cities and Society., 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B. C. Sustainable growth: A circular economy perspective. Journal of Economic Issues 2020, 54(2), 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Nie, J.; Yuan, H. Interactive decisions of the waste producer and the recycler in construction waste recycling. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 256, 120403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luick, R; Jedicke, E; Fartmann, T; et al. Der Wald im Spannungsfeld von Klimaschutz und Ressourcenbereitstellung. Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung (NuL) 2025, 57, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaba, A. K.; Aryatwijuka, W.; Ntayi, J. M.; Bagire, V. Network structure in disaster response: The mediating role of coordination within a humanitarian organizational network in Uganda. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2025, 7(1), 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minunno, R.; O’Grady, T.; Morrison, G.; Gruner, R.; Colling, M. Strategies for applying the circular economy to prefabricated buildings. Buildings 2018, 8(9), 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, I. M.; Cabrita, I.; Gulyurtlu, P.; Filomena, P. Polymer-based waste materials for recycling. In Waste and Waste Management; New York, NY; Nova Science Publishers, 2013; pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-62618-284-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić, N.; Cvetković, V. M.; Renner, R.; Cvijović, N.; Gačić, J. Disaster risk perception and local resilience near the “Duboko” landfill: Challenges of governance, management, trust, and environmental communication in Serbia. In Preprints: The Multidisciplinary Preprint Platform; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić, N.; Zečević, M.; Gajović, A. Управление качествoм в экoлoгии (Искушения в Республике Сербскoй); Иннoвациoнная наука; Междунарoдный научный журнал, 2020; Volume 3, pp. 24–32. ISSN 2410-6070. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The circular economy in cities and regions: Synthesis report. In OECD urban studies; OECD Publishing; Paris, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ojha, J. C.; Bhattarai, P. C.; Devkota, B. Teachers’ perception towards responses of COVID-19 pandemic management in Gandaki Province of Nepal: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2025, 7(1), 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Partnering for our planet: How life-cycle thinking can help the construction industry’s sustainability efforts. 2017). Retrieved September 27, 2020. Available online: https://blog.tatasteelconstruction.com/partnering-planet-life-cycle-thinking-can-help-construction-industrys-sustainability-efforts/.

- Poglavlje 27 – Životna sredina. 2020. Available online: https://europeanwesternbalkans.rs/poglavlje-27/.

- Povetkin, K.; Isaac, S. Identifying and addressing latent causes of construction waste in infrastructure projects. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhananga, P.; Elzomor, M. Revamping sustainability efforts post-disaster by adopting circular economy resilience practices. Sustainability 2023, 15(22), 15870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regattieri, A.; Gamberi, M.; Bortolini, M.; Piana, F. Innovative solutions for reusing packaging waste materials in humanitarian logistics. Sustainability 2018, 10(5), 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O. Risk governance: coping with uncertainty in a complex world; Routledge, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, L. A. L.; Ramón, X. R.; Domingo, S. The circular economy in the construction and demolition waste sector: A review and an integrative model approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 119238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajidha, H.; Mortula, M. Sustainable waste management in the construction industry; Frontiers in Sustainable Cities., 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G. V.; Baldwin, J.; Koh, S. L.; Choi, T. Y. Fragmented institutional fields and their impact on manufacturing environmental practices. International Journal of Production Research 2017, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojlović, D.; Spasojević-Šantić, T.; Trivunić, M. Analysis of the state of construction waste management in the Republic of Serbia. People, Buildings and Environment 2016: An International Scientific Conference, Luhačovice, Czech Republic; 2016; Vol. 4, pp. 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Tushabe, G.; Rukundo, P. M.; Kaaya, A. N.; Nahalomo, A.; Nateme, N. C.; Iversen, P. O.; Rukooko, A. B. Retrogressive or misplaced priorities? An assessment of public expenditure for food security and disaster risk reduction in Uganda. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2025, 7(1), 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlada Republike Srbije; Ministarstvo poljoprivrede i zaštite životne sredine. Strategija upravljanja otpadom; Belgrade, Serbia; Author, 2018a. [Google Scholar]

- Vlada Republike Srbije; Ministarstvo poljoprivrede i zaštite životne sredine. Zakon o upravljanju otpadom; Belgrade, Serbia; Author, 2018b. [Google Scholar]

- Vukić, T. Obrazovanje za održivi razvoj kao izborni program. Istraživanja u Pedagogiji – Research in Pedagogy 2020, 10(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, M.; Teittinen, T.; Kaartinen, T.; Vanden Eynde, A. Deliverable 3.1: Hazardous substances in construction products and materials. EIT Raw Materials; European Institute of Innovation and Technology, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Risk communications. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/risk-communications.

Table 1.

Overview and comparison of data obtained in the Republic of Serbia and the European Union.

Table 1.

Overview and comparison of data obtained in the Republic of Serbia and the European Union.

|

Question

|

Republic of Serbia

|

European Union

|

Comment

|

|

Main company activities

|

13% perform urban demolition; 6% industrial demolition; 6% manage waste and recycling; 31% are general demolition contractors; 31% work as project managers in demolition; 13% list demolition/waste management as complementary to their main business |

28% perform urban demolition; 9% industrial demolition; 1% scraping; 1% waste management and recycling; 47% are general demolition contractors; 3% work as project managers; 9% listed demolition/waste management as complementary |

In the EU, 47% of surveyed companies are general contractors. |

|

Company revenues in 2018 (all activities)

|

50% earned less than €1M; 13% between €1M–€5M; 19% between €5M–€15M; 19% between €30M–€50M |

13% earned less than €1M; 35% between €1M–€5M; 24% between €5M–€15M; 14% between €15M–€30M; 7% between €30M–€50M; 7% over €50M |

In the EU, 7% of companies earned over €50M, while no such data was recorded for Serbia. |

|

Revenue from demolition-related activities

|

69% earned less than 25% from these activities; 19% earned 25–50%; 13% earned more than 75% |

16% earned less than 25%; 17% earned 25–50%; 23% earned 50–70%; 45% earned more than 75% |

In the EU, 45% of companies earned over 75% of their revenue from demolition-related activities—an indicator of circular economy potential. |

|

Are companies contractors?

|

13% large; 50% medium; 38% small |

17% large; 49% medium; 35% small |

Differences are minor. |

|

Revenue growth in 2018 vs. 2017 (demolition activities)

|

27% reported significant growth (+15%); 13% slight growth (+5% to +15%); 40% stable (-5% to +5%); 20% slight decline (-5% to -15%) |

29% significant growth (+15%); 32% slight growth (+5% to +15%); 27% stable (-/+5%); 9% slight decline (-5% to -15%); 3% significant decline (>15%) |

EU companies show stronger growth in demolition revenue, while Serbia shows primarily stable growth. |

|

Revenue from decontamination (e.g., asbestos, hazardous substances)

|

7% earned over 50%; 13% earned 11–25%; 80% earned up to 10% |

8% earned over 50%; 18% earned 26–50%; 36% earned 11–25%; 38% earned less than 10% |

In Serbia, 80% of companies earned only 10% or less from decontamination, while 18% of EU companies earned between 26% and 50%. |

|

Revenue from waste management (sorting, transport, recycling)

|

13% earned over 50%; 7% earned 26–50%; 80% earned less than 10% |

8% earned over 50%; 21% earned 26–50%; 38% earned 11–25%; 33% earned less than 10% |

In Serbia, 80% of companies earned less than 10% of their revenue from waste management activities. |

|

Business outlook for 2019 (demolition activities)

|

7% expected significant growth (+15%); 27% slight growth (+5% to +15%); 53% stable (+/-5%); 13% slight decline (-5% to -15%) |

12% expected significant growth (+15%); 36% slight growth (+5% to +15%); 34% stable (+/-5%); 13% slight decline (-5% to -15%); 5% significant decline (>15%) |

Serbia expects mostly stable business, while the EU expects higher growth in demolition activities. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).