Submitted:

04 November 2025

Posted:

05 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of the Nursery Phase

1.2. Determinants of Nursery Success

1.2.1. Irrigation

1.2.2. Fertilization

1.2.3. Cultivar Selection

1.3. Challenges in Integrated Management

1.4. Current Limitations in Nursery Water and Nutrient Management

1.5. Research Rationale and Objectives

2. Results and Discussion

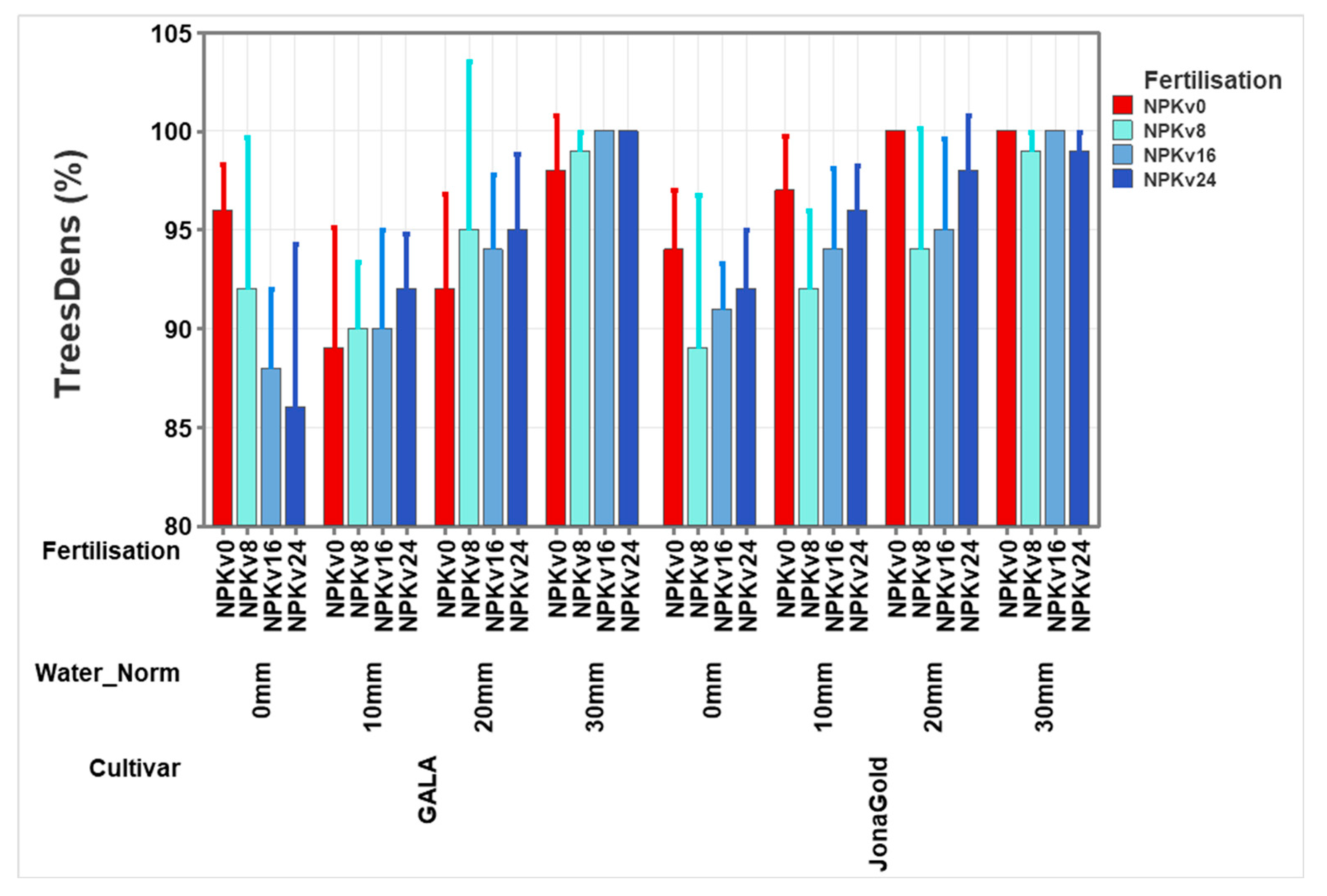

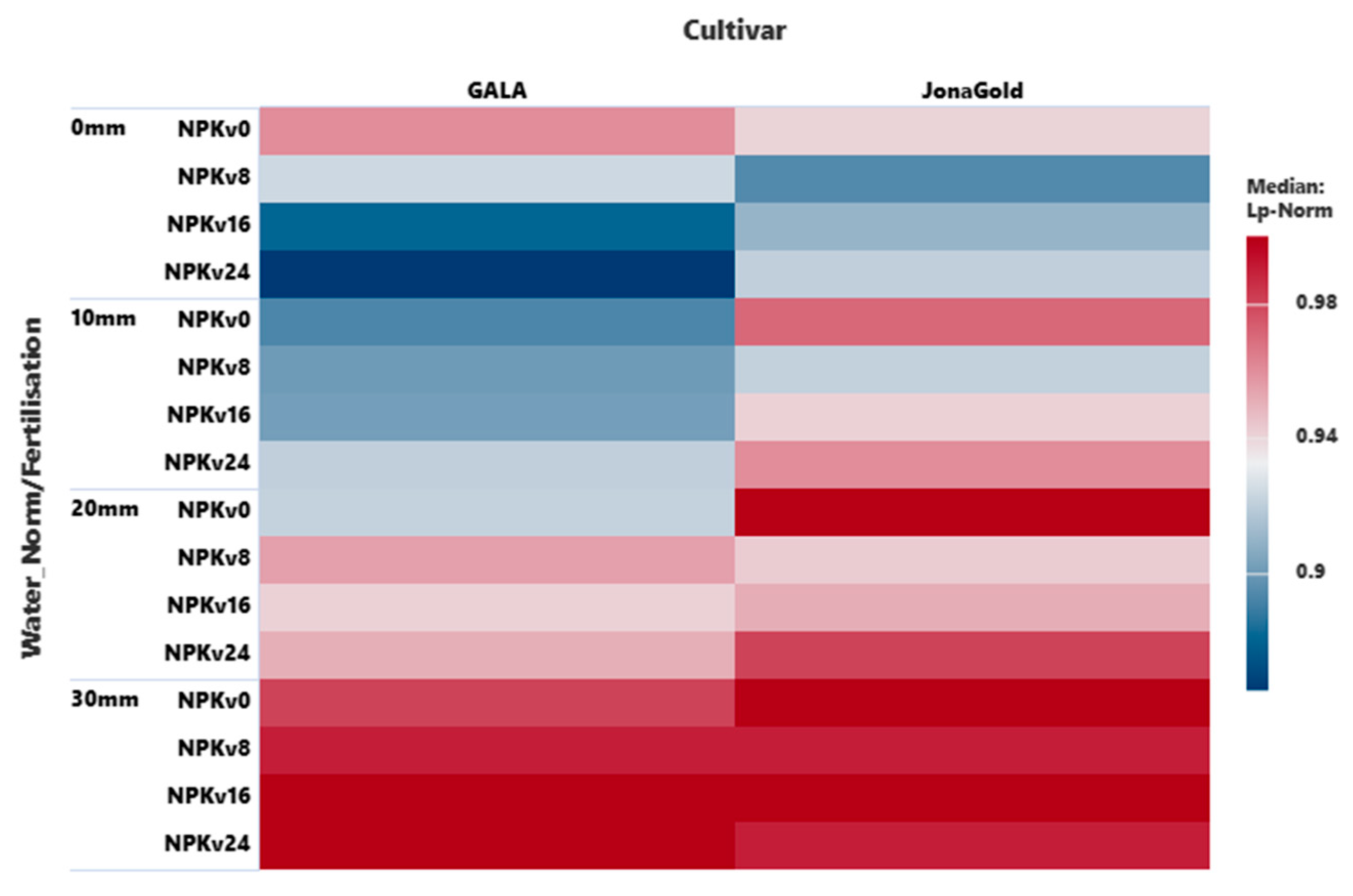

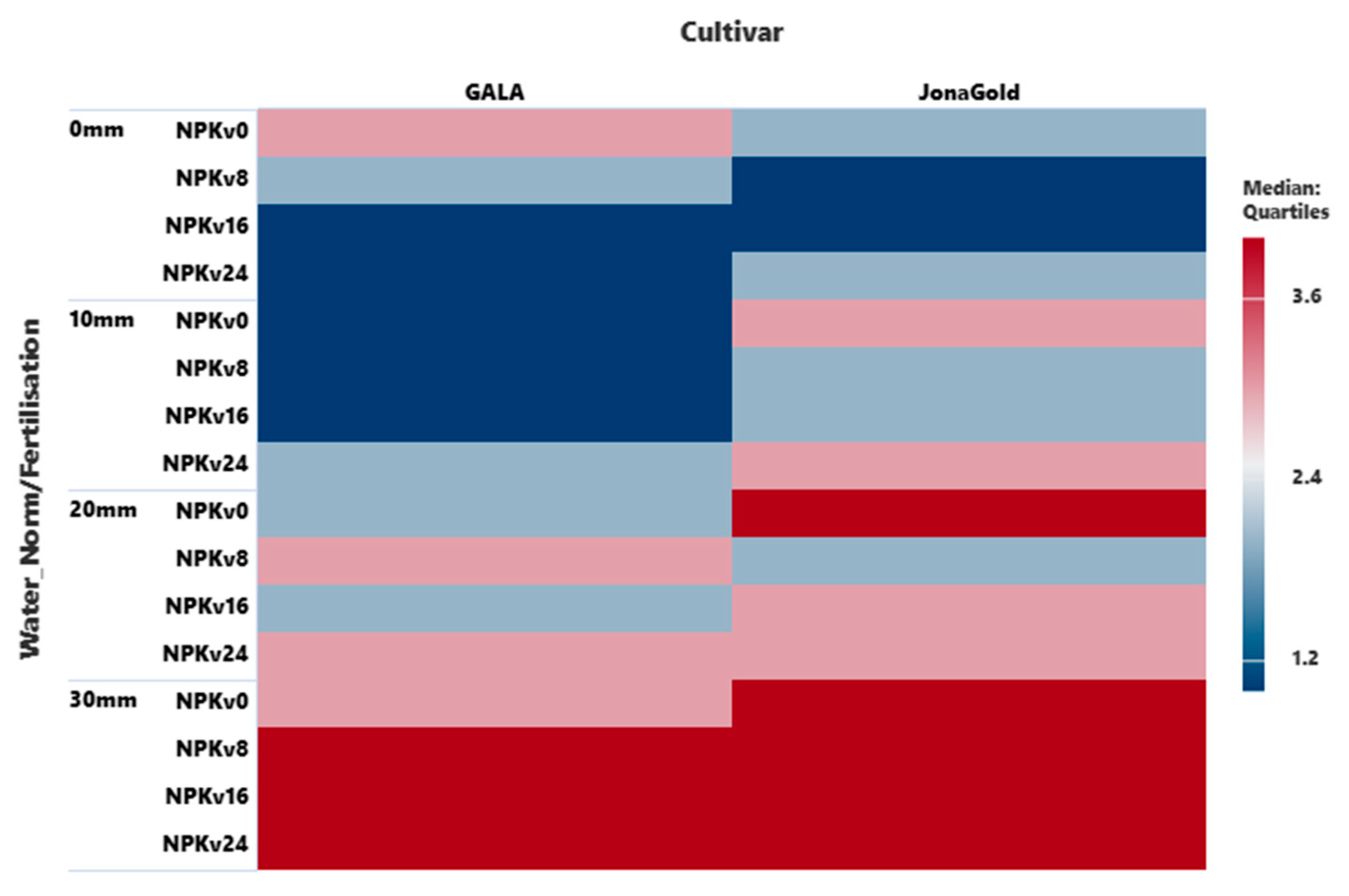

2.1. Effect of Fertilisation, Watering Norm and Cultivar on Apple Trees Density

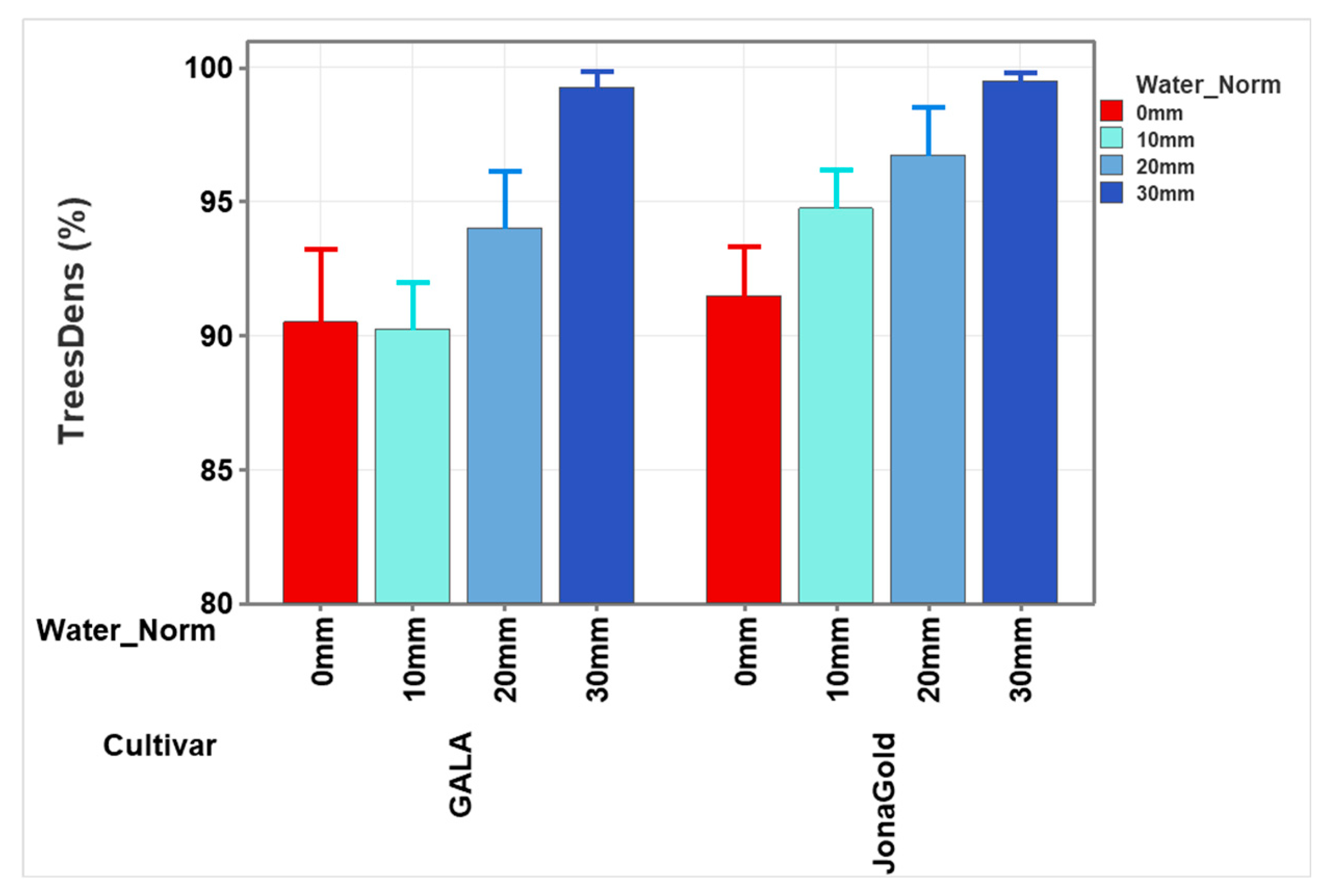

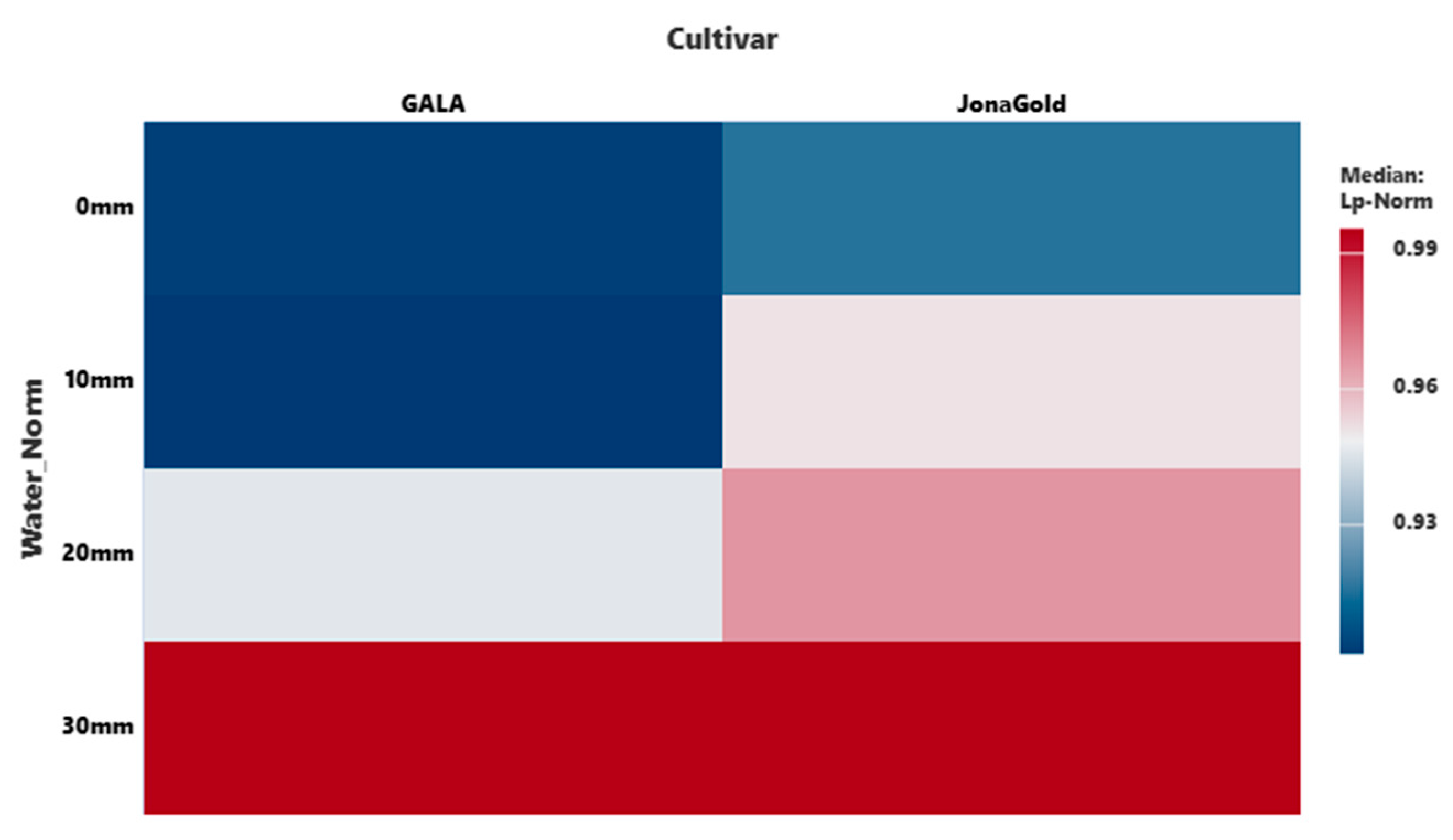

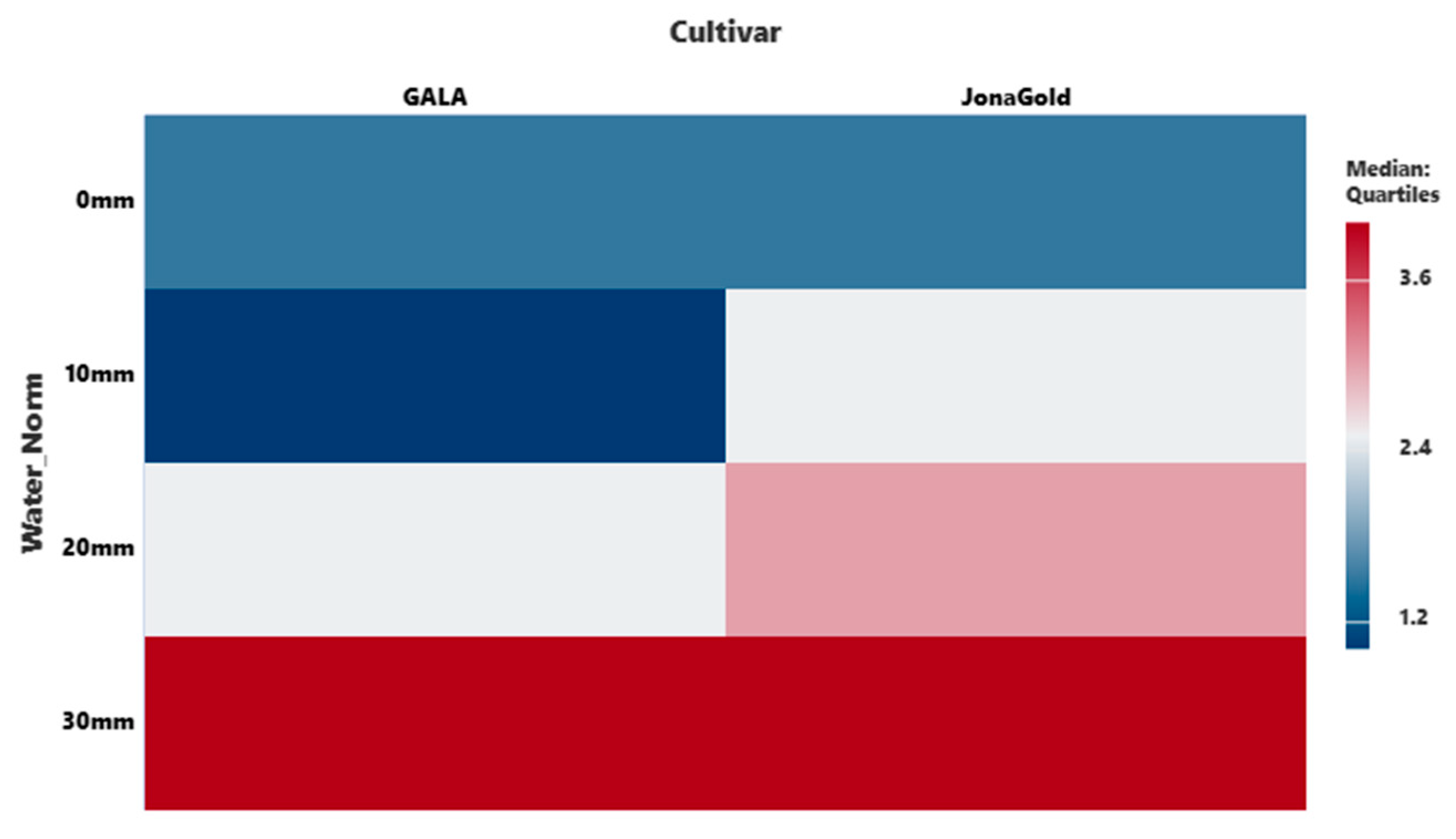

2.2. Effect of Water Norm and Cultivar on Apple Trees Density

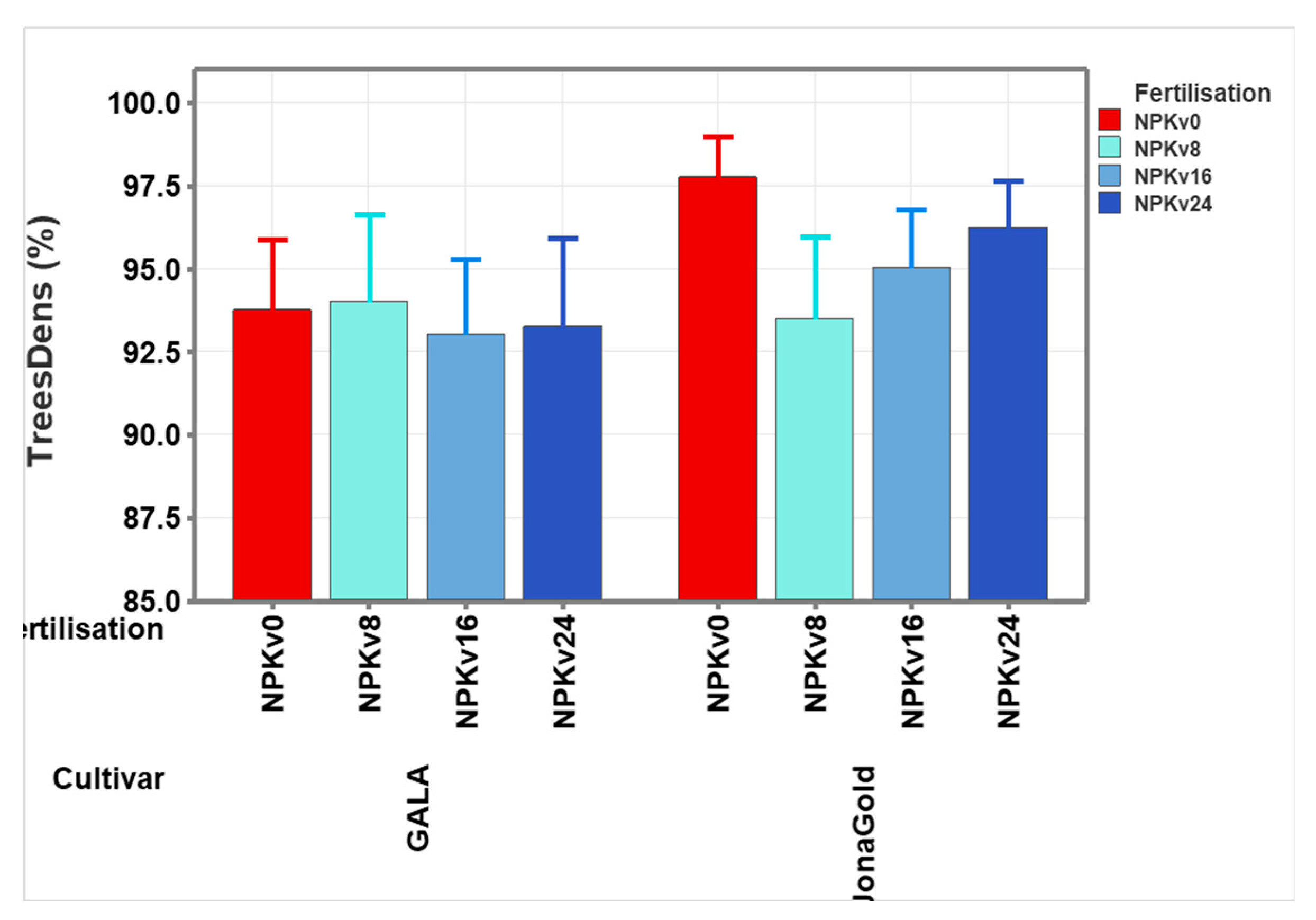

2.3. Effect of Fertilisation and Cultivar on Apple Trees Density

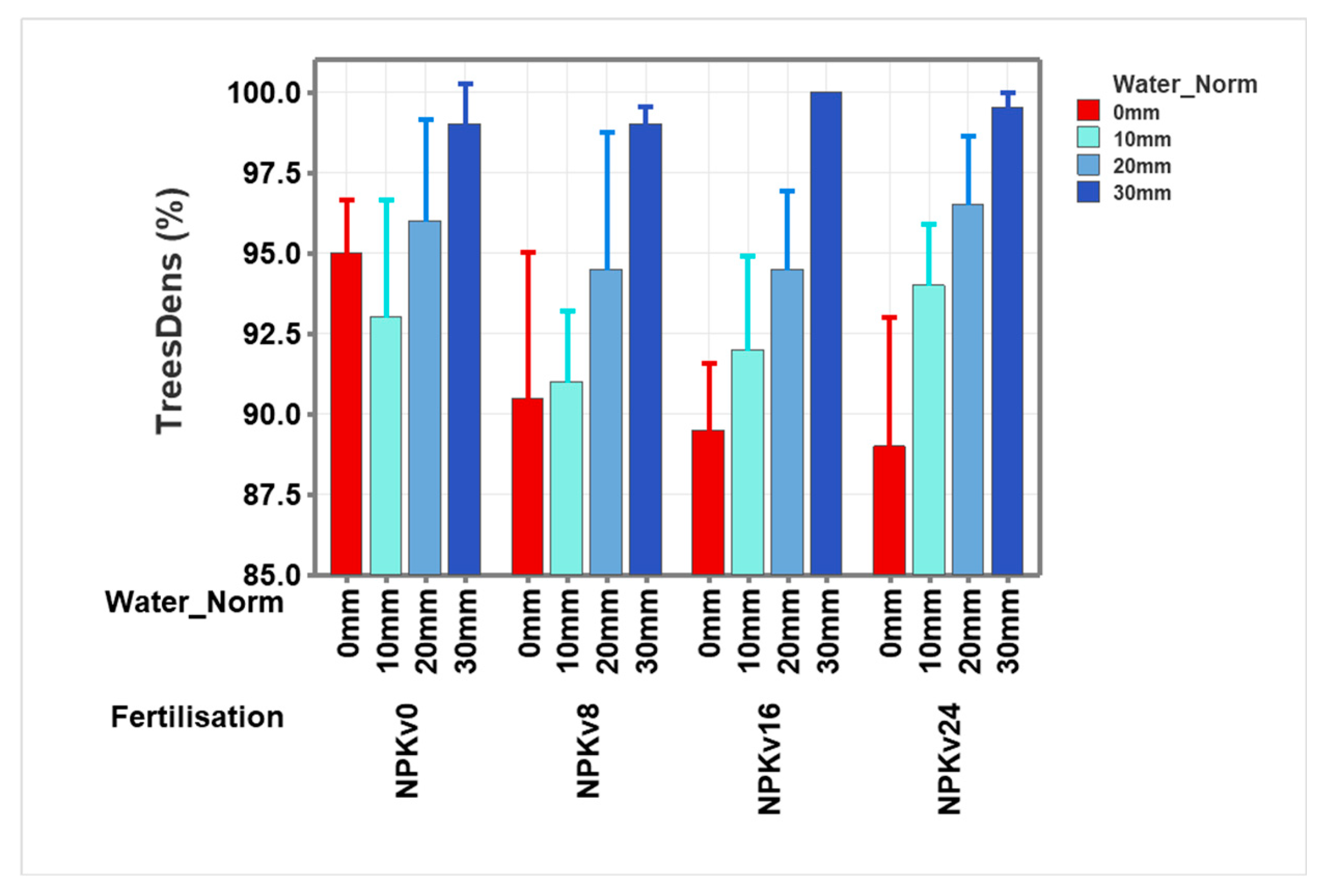

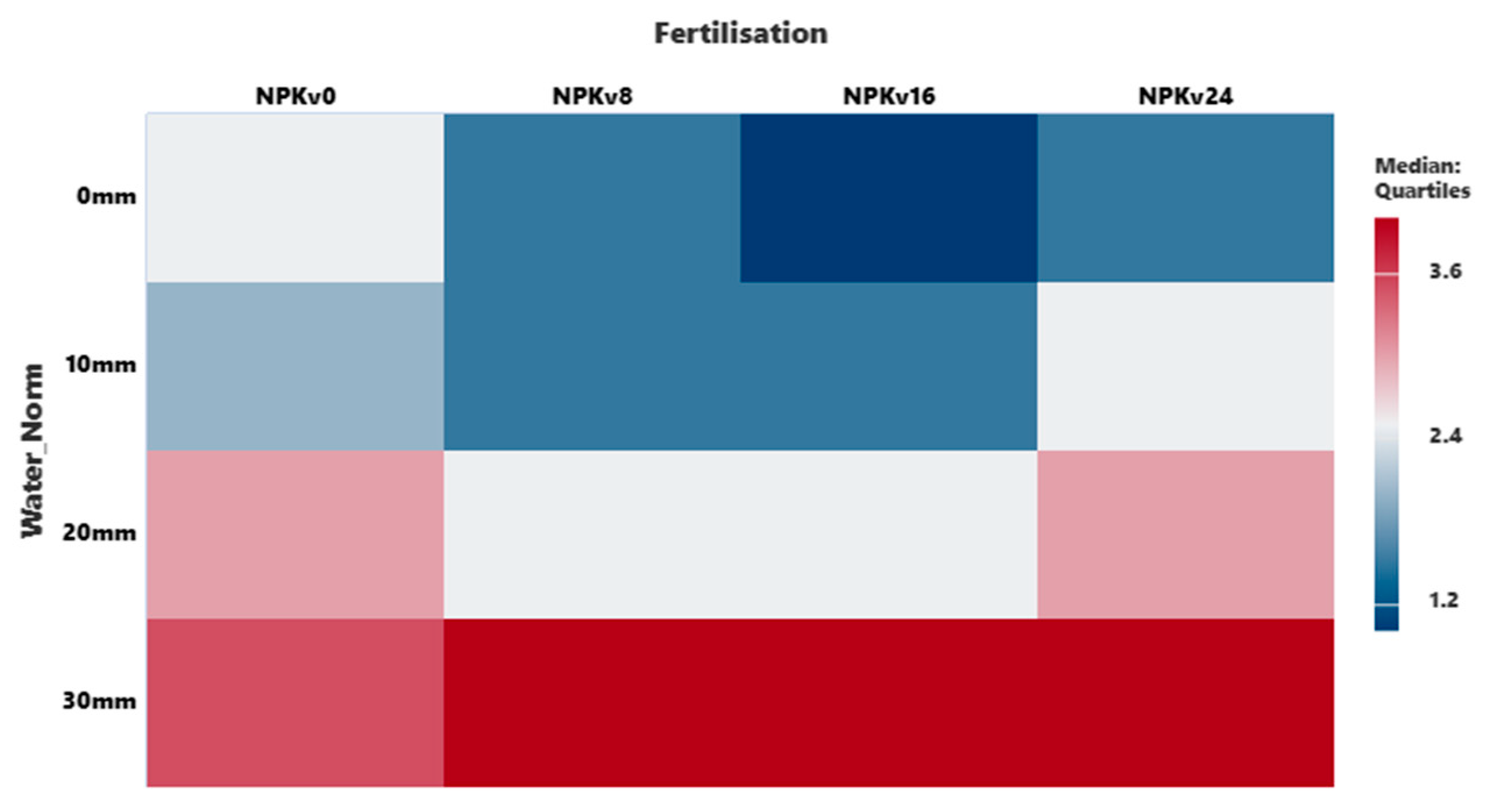

2.4. Effect of Watering Norm and Fertilisation on Apple Trees Density

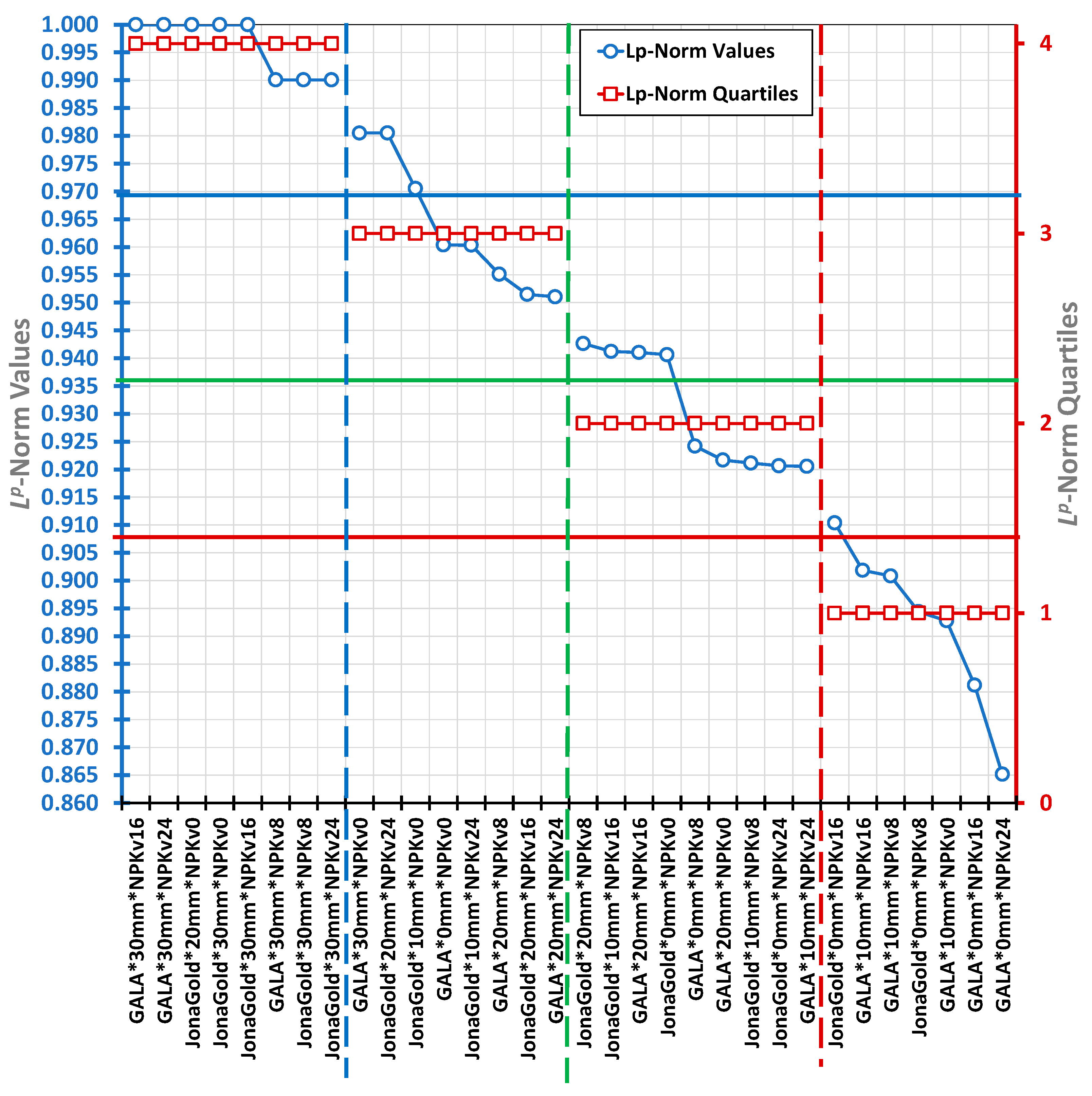

2.5. Classification of Apple Cultivars Based on Water and Fertilisation Treatments

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Climate and Soil Conditions of the Research Location

3.2. Research Methods and Biological Material Used

3.3. Calculations

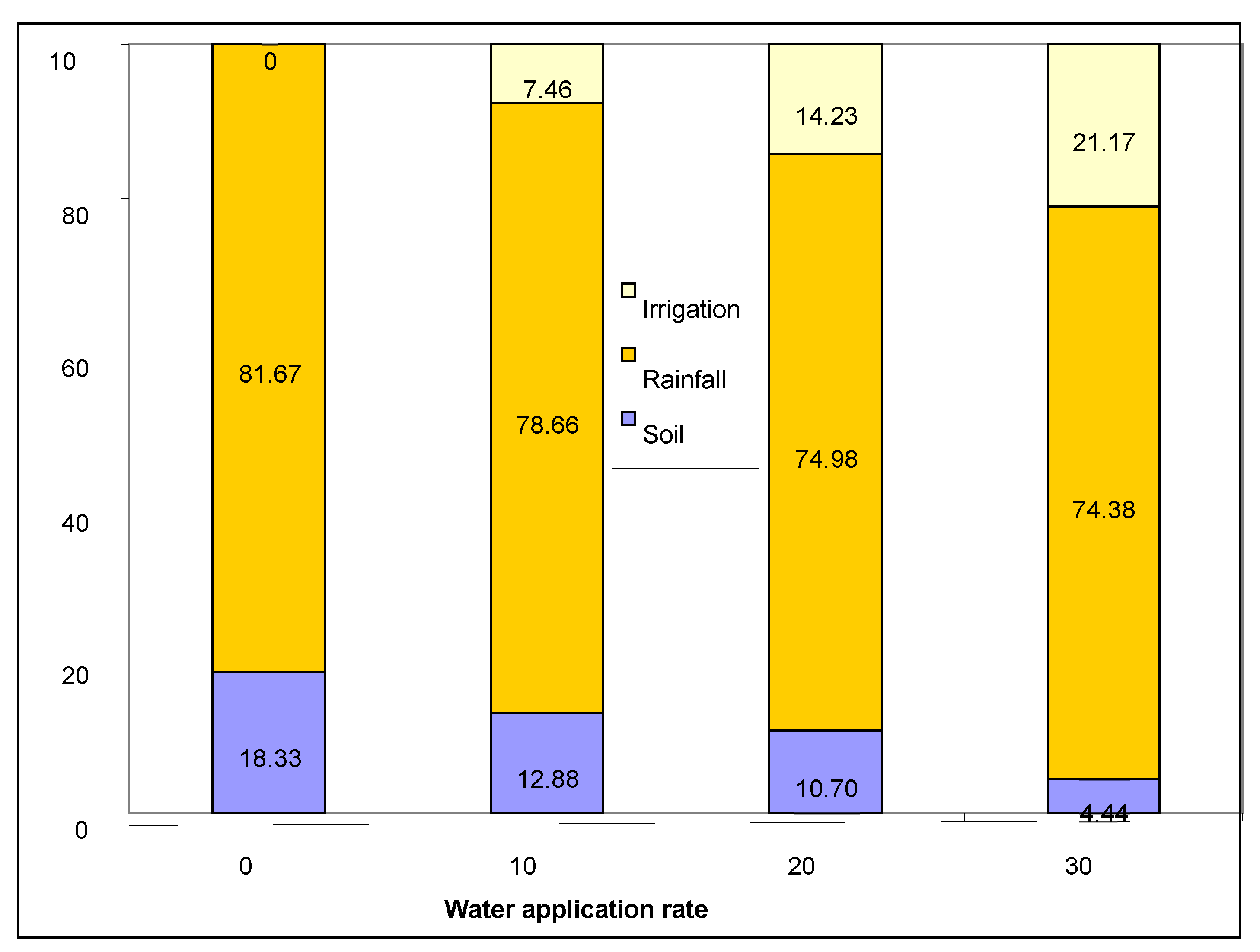

3.4. Water Consumption for Different Irrigation Conditions

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spinelli, G.; Bonarrigo, A.C.; Cui, W.; Grobowsky, K.; Jordan, S.H.; Ondris, K.; Dahlke, H.E. Evaluating the Distribution Uniformity of Ten Overhead Sprinkler Models Used in Container Nurseries. Agricultural Water Management 2024, 303, 109042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardivo, C.; Patel, S.; Bowman, K.D.; Albrecht, U. Nursery Characteristics and Field Performance of Nine Novel Citrus Rootstocks under HLB-Endemic Conditions. HortScience 2025, 60, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Xu, W.; Kang, B.; Eisner, R.; Muleke, A.; Rodriguez, D.; Harrison, M.T. Irrigation with Artificial Intelligence: Problems, Premises, Promises. Hum.-Cent. Intell. Syst. 2024, 4, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Sharma, N.C.; Kumar, P.; Verma, P.; Singh, U.; Verma, P. Optimisation of Budding Timing and Methods for Production of Quality Apricot Nursery Plants. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, M.K.V. Irrigation Research: Developing a Holistic Approach. Acta Hortic. 2000, 537, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.; Ragettli, S.; Sinha, R.; Zhovtonog, O.; Yu, W.; Karimi, P. Regional Irrigation Expansion Can Support Climate-Resilient Crop Production in Post-Invasion Ukraine. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolae, S.; Butac, M.; Chivu, M. Comparative Study in the Nursery of Vegetative Plum Rootstocks, ‘Mirodad 1’ and ‘Saint Julien A’. Sci. Pap. Ser. B Hortic. 2024, LXVIII(1), 94–98. Print ISSN 2285-5653.

- Kumawat, K.L.; Raja, W.H.; Nabi, S.U. Quality of Nursery Trees Is Critical for Optimal Growth and Inducing Precocity in Apple. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2024, 66, 2135–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, K.L.; Raja, W.H.; Chand, L.; Rai, K.M.; Lal, S. Influence of Plant Growth Regulators on Growth and Formation of Sylleptic Shoots in One-Year-Old Apple cv. Gala Mast. J. Environ. Biol. 2023, 44, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Majumder, S. Water Management in Agriculture: Innovations for Efficient Irrigation. Mod. Agron. 2024, 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Heera, J. Challenges Encountered by Nursery Owners When Producing Seedlings. Indo-Am. J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2025, 13(2), 1–10.

- Oyedele, O.O.; Adebisi-Adelani, O.; Amao, I.O.; Ibe, R.B.; Arogundade, O.; Amosu, S.A.; Alamu, O.O. Knowledge Uptake of Stakeholders in Fruit Tree Production Training in Ibadan, Oyo State. J. Agric. Ext. 2025, 29(3), 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, H.N.; Sema, A.; Singh, B.; Sarkar, A.; Konjengbam, R. Nursery Performance of Khasi Mandarin on Different Citrus Rootstocks in Northeast India. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2025, 67, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, R.; Alavekar, M.S.; Singh, R.P.; Singh, D. Nursery Management and Disease Control. Hortic. Crops 2025, 174. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, L.I.; Robinson, T.L. Effects of Tree Lateral Branch Number and Angle on Early Growth and Yield of High-Density Apple Trees. HortTechnology 2025, 35, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. My Little Fruit Tree; Franckh Kosmos Publishing House: Stuttgart, Germany, 2019; p. 113. ISBN 9783440163645.

- Zahir, S.A.D.M.; Jamlos, M.F.; Omar, A.F.; Nordin, M.A.H.; Raypah, M.E.A.; Mamat, R.; Muncan, J. Quantifying the Impact of Varied NPK Fertilizer Levels on Oil Palm Plants during the Nursery Stage: A Vis-NIR Spectral Reflectance Analysis. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.S.; Raja, W.; Kanth, R.H.; Dar, E.A.; Shah, Z.A.; Bhat, M.A.; Salem, A. Optimizing Irrigation and Nitrogen Levels to Achieve Sustainable Rice Productivity and Profitability. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotowa, O.J.; Małek, S.; Jasik, M.; Staszel-Szlachta, K. Substrate and Fertilisation Used in the Nursery Influence Biomass and Nutrient Allocation in Fagus sylvatica and Quercus robur Seedlings after the First Year of Growth in a Newly Established Forest. Forests 2025, 16, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-H.; Kim, D.-Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, K.H. Effect of Nutrient Management during the Nursery Period on the Growth, Tissue Nutrient Content, and Flowering Characteristics of Hydroponic Strawberry in 2022. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Liu, D.; Li, C.; Xu, C.; Huang, H. Dwarfing of Fruit Trees: From Old Cognitions to New Insights. Hortic. Adv. 2025, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aglar, E.; Ozturk, B.; Saracoglu, O.; Demirsoy, H.; Demirsoy, L. Rootstock and Training Effects on Growth and Fruit Quality of Young ‘0900 Ziraat’ Sweet Cherry Trees. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2024, 66, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.U.; Malik, A.U.; Saleem, B.A.; Raza, H.; Amin, M. Supplementation of Potassium and Phosphorus Nutrients to Young Trees Reduced Rind Thickness and Improved Sweetness in ‘Kinnow’ Mandarin Fruit. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2023, 65, 1657–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nečas, T.; Wolf, J.; Kiss, T.; Göttingerová, M.; Ondrášek, I.; Venuta, R.; Laňar, L.; Letocha, T. Improving the Quality of Nursery Apple and Pear Trees with the Use of Different Plant Growth Regulators. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2020, 85, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Kiss, T.; Ondrašek, I.; Nečas, T. Induction of Lateral Branching of Sweet Cherry and Plum in Fruit Nursery. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobo Cluj Napoca 2019, 47, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyad-Amin, P. A Review on Breeding Fruit Trees Against Climate Changes. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2022, 64, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.S.S.; Soares, P.R.; Guilherme, R.; Vitali, G.; Boulet, A.; Harrison, M.T.; Malamiri, H.; Duarte, A.C.; Kalantari, Z.; Ferreira, A.J.D. Sustainable Water Management in Horticulture: Problems, Premises, and Promises. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, K.; Witcher, A.; Baysal-Gurel, F. An Evaluation of the Effect of Fertilizer Rate on Tree Growth and the Detection of Nutrient Stress in Different Irrigation Systems. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Optimization of Irrigation and Fertilization of Apples under Magnetoelectric Water Irrigation in Extremely Arid Areas. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1356338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankotia, S.; Sharma, J. C.; Verma, M. L. Impact of Irrigation and Fertigation Schedules on Physical and Biochemical Properties of Apple under High-Density Plantation. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2024, 56, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mašán, V.; Burg, P.; Vaštík, L.; Vlk, R.; Souček, J.; Krakowiak-Bal, A. The Evaluation of the Impact of Different Drip Irrigation Systems on the Vegetative Growth and Fruitfulness of ‘Gala’ Apple Trees. Agronomy 2025, 15(9), 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chira, L.; Pașca, I. Apple Trees Growing; MAST Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2004; p. 37. ISBN 9738497981.

- Zhou, H.; Niu, X.; Yan, H.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, F.; Wu, L.; Yin, D.; Kjelgren, R. Effect of Water–Fertilizer Coupling on the Growth and Physiological Characteristics of Young Apple Trees. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Effects of water and nitrogen regulation on apple tree growth and physiological characteristics. Plants 2024, 13, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Optimizing planting density for production of high-quality apple nursery stock. New Zeal. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2015, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ladon, T.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Optimizing apple orchard management: Investigating the impact of planting density, training systems, and fertigation levels on tree growth, yield, and fruit quality. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 289, 110428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csihon, Á.; Holb, I.J.; Szabó, Z.; Kovács, G.; Varga, A.; Tóth, B.; Sárközi, M.; Tóth, M.; Bálint, A.; Kocsis, M.; et al. Impacts of N-P-K-Mg fertilizer combinations on tree parameters and fungal disease incidences in apple cultivars with varying disease susceptibility. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Investigation of effective irrigation strategies for high-density apple orchards. Agronomy 2021, 11, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tojnko, S.; Čmelik, Z. Influence of irrigation and fertilization on performances of young apple trees. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2000, 65, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, E.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Effects of irrigation on cropping of ‘Elstar’, ‘Golden Delicious’, ‘Idared’, and ‘Jonagold’ apple trees. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2005, 70, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sompouviset, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Mulching and irrigation strategies for climate-resilient apple orchards. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 86552. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Effects of fertilization and drip irrigation on the growth and physiological characteristics of young apple trees. Forests 2024, 15, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, B.; Kannan, S.; McGregor, A. Approximating the Best–Fit Tree Under Lp Norms. In Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Approximation Algorithms for Combinatorial Optimization Problems (APPROX 2005) and the 8th International Workshop on Randomization and Computation (RANDOM 2005), Berkeley, CA, USA, 22–24 August 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 118–129. [Google Scholar]

- Enache, L. Agrometeorology, Sitech Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2012.

| Cultivar | Frequency | Tree_Density (%) |

|---|---|---|

| GALA | 80 | 93.50b ± 6.195 |

| JonaGold | 80 | 95.63a ± 4.790 |

| Water_Norm | Frequency | Tree_Density (%) |

| 0mm | 40 | 91.00c ± 5.987 |

| 10mm | 40 | 92.50c ± 4.701 |

| 20mm | 40 | 95.38b ± 5.236 |

| 30mm | 40 | 99.38a ± 1.295 |

| Fertilisation | Frequency | Tree_Density (%) |

| NPKv0 | 40 | 95.75a ± 4.882 |

| NPKv8 | 40 | 93.75a ± 6.484 |

| NPKv16 | 40 | 94.00a ± 5.330 |

| NPKv24 | 40 | 94.75a ± 5.665 |

| Cultivar*Water_Norm | Frequency | Tree_Density (%) |

|---|---|---|

| GALA_0mm | 20 | 90.50d ± 7.090 |

| GALA_10mm | 20 | 90.25d ± 4.494 |

| GALA_20mm | 20 | 94.00bc ± 5.544 |

| GALA_30mm | 20 | 99.25a ± 1.650 |

| JonaGold_0mm | 20 | 91.50cd ± 4.774 |

| JonaGold_10mm | 20 | 94.75b ± 3.810 |

| JonaGold_20mm | 20 | 96.75ab ± 4.644 |

| JonaGold_30mm | 20 | 99.50a ± 0.827 |

| Cultivar*Fertilisation | Frequency | Tree_Density (%) |

| GALA_NPKv0 | 20 | 93.75bc ± 5.486 |

| GALA_NPKv8 | 20 | 94.00c ± 6.751 |

| GALA_NPKv16 | 20 | 93.00bc ± 5.912 |

| GALA_NPKv24 | 20 | 93.25bc ± 6.950 |

| JonaGold_NPKv0 | 20 | 97.75a ± 3.226 |

| JonaGold_NPKv8 | 20 | 93.50abc ± 6.370 |

| JonaGold_NPKv16 | 20 | 95.00ab ± 4.611 |

| JonaGold_NPKv24 | 20 | 96.25bc ± 3.582 |

| Fertilisation*Water_Norm | Frequency | Tree_Density (%) |

|---|---|---|

| NPKv0_0mm | 10 | 95.00bcd ± 2.867 |

| NPKv0_10mm | 10 | 93.00de ± 6.325 |

| NPKv0_20mm | 10 | 96.00e ± 5.416 |

| NPKv0_30mm | 10 | 99.00e ± 2.211 |

| NPKv8_0mm | 10 | 90.50cde ± 7.807 |

| NPKv8_10mm | 10 | 91.00de ± 3.801 |

| NPKv8_20mm | 10 | 94.50cde ± 7.382 |

| NPKv8_30mm | 10 | 99.00cd ± 0.943 |

| NPKv16_0mm | 10 | 89.50abc ± 3.598 |

| NPKv16_10mm | 10 | 92.00cd ± 5.011 |

| NPKv16_20mm | 10 | 94.50cd ± 4.223 |

| NPKv16_30mm | 10 | 100.00abc ± 0.000 |

| NPKv24_0mm | 10 | 89.00ab ± 6.944 |

| NPKv24_10mm | 10 | 94.00ab ± 3.266 |

| NPKv24_20mm | 10 | 96.50a ± 3.689 |

| NPKv24_30mm | 10 | 99.50a ± 0.850 |

| Month | Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Average monthly temperatures (0C) |

-2.5 | -1.9 | 4.0 | 12.5 | 16.0 | 19.5 | 24.0 | 20.0 | 18.3 | 13.5 | 7.5 | -2.4 | 10.7 |

|

Average monthly precipitations (mm) |

12.5 | 15.7 | 18.0 | 2.0 | 103.8 | 55.6 | 86.4 | 30.8 | 57 | 63 | 20.4 | 54.3 | 43.29 |

| Year | Irrigation rate | Total water consumption (m3/ha) |

Source of water consumption coverage (m3 /ha) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | Rainfall | Irrigation | |||

| 2024 | 0 mm | 3.872 | 0.071 | 3.162 | - |

| 10 mm | 4.020 | 0.0558 | 3.162 | 0.3 | |

| 20 mm | 4.217 | 0.0455 | 3.162 | 0.6 | |

| 30 mm | 4.251 | 0.0189 | 3.162 | 0.9 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).