1. Introduction

Except for the alpine regions, Romania’s pedoclimatic conditions are generally suitable for tree production. They help produce fruits of exceptional quality that are exquisitely colored, have a unique scent, and have a delightful flavor. Rich in readily absorbed sugars, proteins, organic acids, pectic and aromatic compounds, mineral salts, lipids, and other nutrients, fruits constitute an essential part of the human diet. Fruit tree culture is also very significant in Romania since it produces a solid base of fresh and preserved fruit and serves as a raw material for the food sector. From this perspective, our nation’s geographic location offers significant benefits. Large tracts of land are used for fruit cultivation, which is the primary reason it is important in our nation.

An integrated framework that produces planting material in specialized nurseries is beneficial to Romanian fruit growing. Concentrating the production of tree planting material in these nurseries first implies the production of high-quality trees, strict sanitary and biological control, rapid opportunities to introduce the most valuable cultivars, the development of a profitable economic activity, and the use of efficient culture technologies.

The primary method of improving the amount and quality of fruit tree output, as well as the sensible and effective use of natural resources, is to optimize fruit plant culture methods.

The extension of the fruit producing sector, the filling of gaps in the new orchards, and the replanting of the lands still held by old orchards are all significant jobs facing our nation’s fruit growing industry. A lot of high-quality tree planting material must be produced to complete these duties.

Given the need to quickly produce many trees and fruit bushes of valuable cultivars and exceptional quality, nurseries are even more important in the current stage of fruit producing growth. To produce huge numbers of high-quality seedlings and grafted trees, the soil’s fertility must be permanently increased, and the soil must contain the appropriate amount of water.

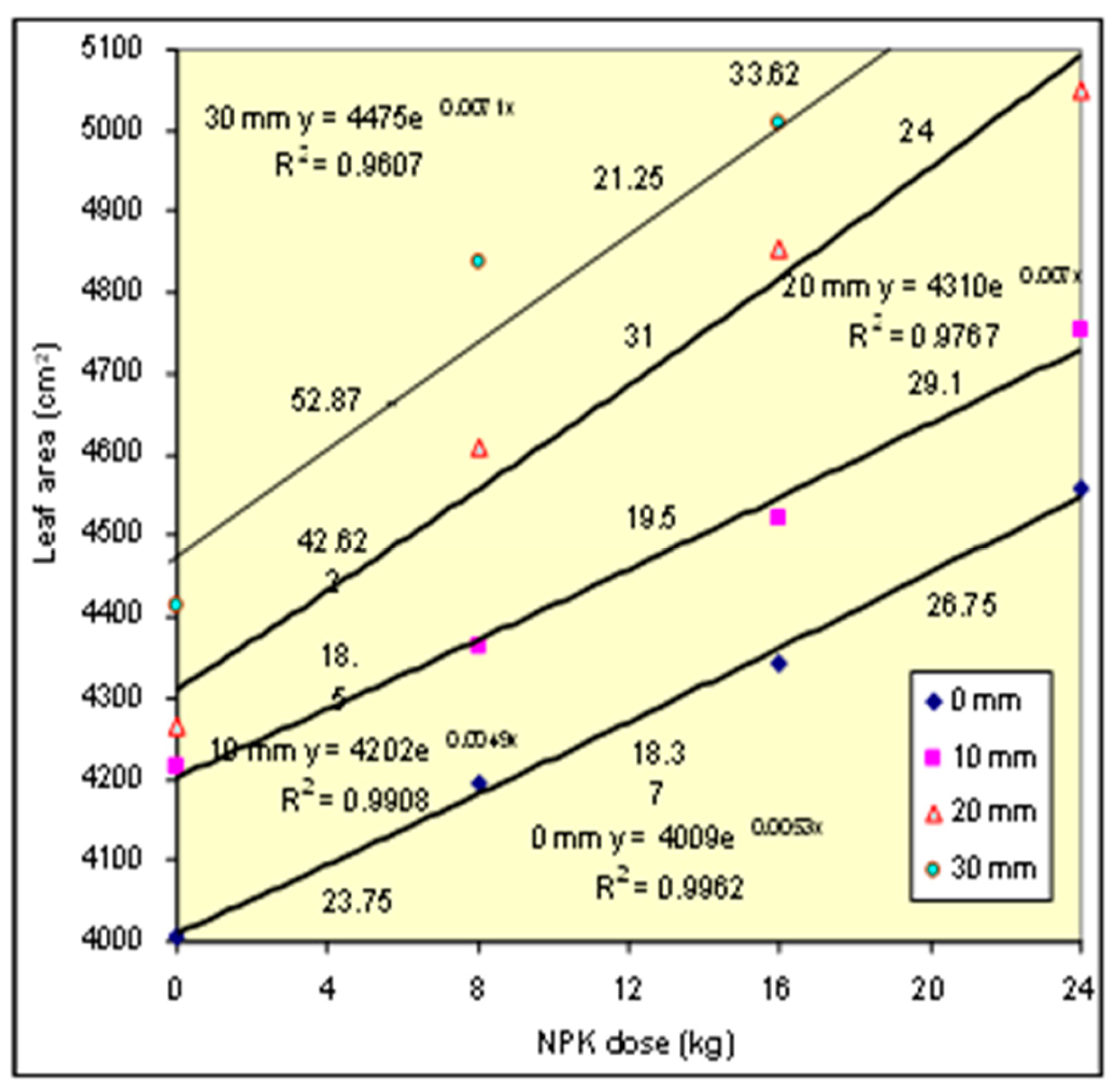

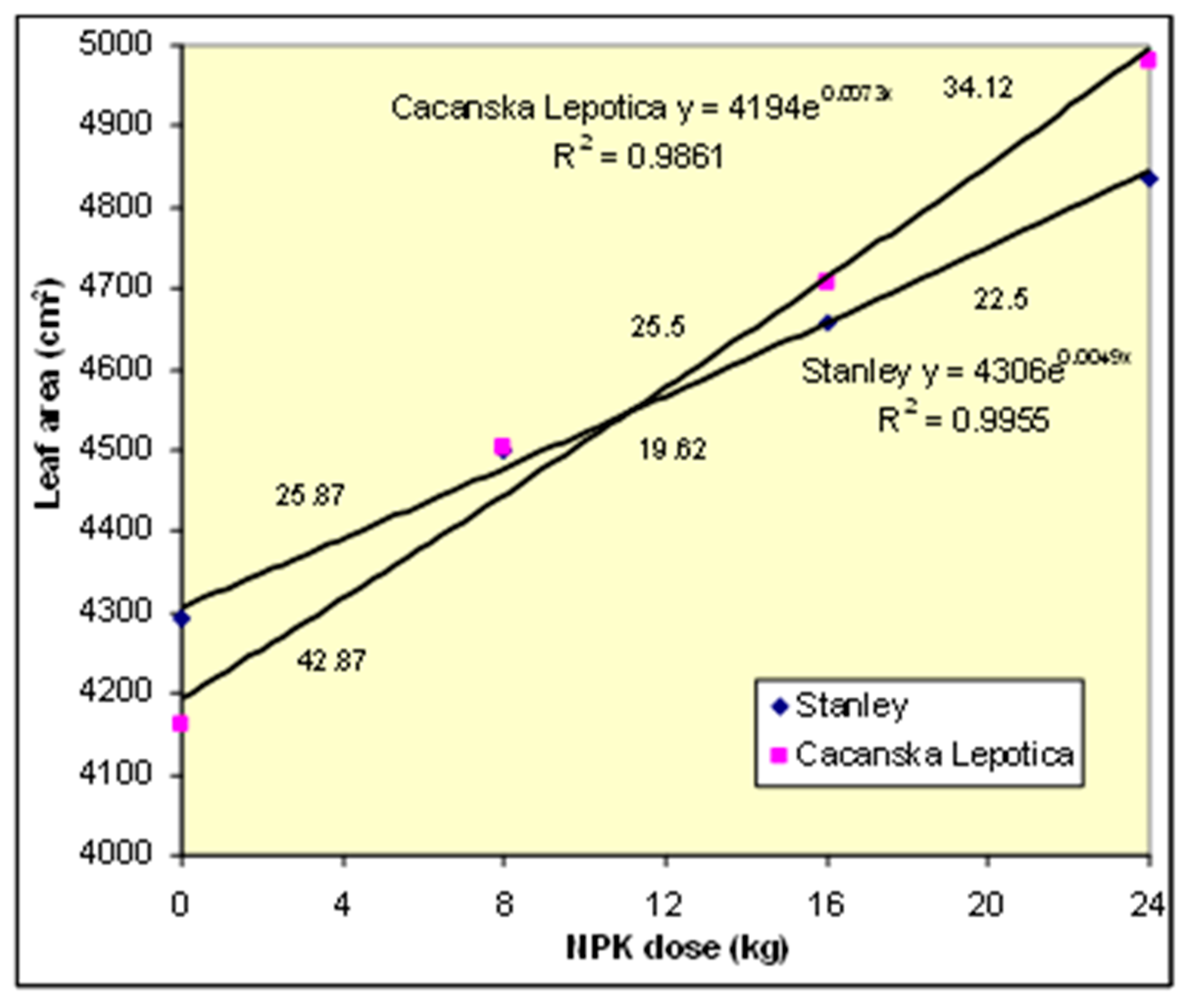

Economic efficiency and yield levels in irrigated agriculture depend primarily on the irrigation regime applied to each individual crop. By establishing and applying a rational irrigation regime, the aim is to supply the soil with water in accordance with the requirements of the plants. The irrigation regime is influenced by natural and technical factors [

1]. Among the natural factors, climate has a decisive influence, through the amount of precipitation and its distribution, through the evolution of temperatures, relative air humidity, droughts, etc. The soil manifests its influence through its physical and hydro physical properties, determines the possibility of retaining water from precipitation and the possibility of making water available to plants. The irrigation regime must be applied according to the distribution of rainfall in the respective year, increasing or reducing the number of waterings according to the water reserve in the soil. In fruit nurseries, the water content in the soil must be maintained within the range of active humidity, i.e., at a level higher than the minimum ceiling. Thus, the water content of the soil must be maintained above the wilting coefficient near which the plants undergo a series of changes during the growth process. For the correct assessment of the irrigation moment, the field capacity of the soil for water or the range of active moisture must be considered. The need to irrigate crops stands out if comparisons are made, on the one hand, between the water consumption of the plants and the amount of useful water from precipitation and groundwater intake, and, on the other hand, between the productions obtained in slightly rainier years than normal and dry years or in irrigated and non-irrigated crop [

2]. In addition to precipitation, to appreciate the need for irrigation, one must know the course of temperature, relative air humidity, the frequency and intensity of winds, because the destructive effects of drought are amplified in dry periods accompanied by high temperatures, low relative air humidity, hot and dry winds. In such cases, the soil drought is also accompanied by an atmospheric drought. The growth of horticultural plants is affected by high temperatures and drought, through the inhibitory effects they have on cell division and extension, as well as on some morphological changes regarding the increase in thickness of leaves and cuticle, reduction of the number of stomata, wilting, change in position of leaves on the plant, abscission, and the change in the number of aquaporins. Unfortunately, in recent years Romania has faced a severe atmospheric drought.

Although nurseries are organized in Romania on generally fertile land, the application of fertilizers is required to create the most favorable conditions for the growth of seedlings and trees, as well as for the activity of soil microorganisms. Although the climatic conditions in Romania ensure the normal growth of saplings and trees without irrigation, nevertheless in excessively dry years this work becomes necessary. Prolonged drought hampers the growth of plants in nurseries. To this is added the fact that in the nursery the trees must have a rapid growth rate, in a short period, in the conditions where the root system of the saplings has been considerably reduced by shaping, to plant and must be restored in the shortest possible time, to be able to explore a large volume of soil. Hence the need to apply fertilizers and works to improve soil fertility and obtain high productions of fruit trees in nurseries. Fertilization of the nursery must include a complex of works that lead to the long-term improvement of the physical and chemical properties and to the completion of the necessary nutrients in assimilable forms per vegetation phase, in relation to the requirements of the trees [

3].

In modern fruit growing, fertilization is one of the most important technological links. Due to their specificity, fruit plants occupy the same area of land for a long time, develop their root system at a significant depth and due to the high productivity, they achieve, they extract from the soil, with the harvest, appreciable amounts of nutrients. Under these conditions, it is necessary to intervene every year, in several rounds, with fertilizations that ensure, on the one hand, the achievement of a certain level of production, and on the other hand, a certain level and ratio of the nutritional elements through returning the amounts of easily accessible nutrients extracted with the harvest in order to be able to maintain, in this way, the fertility of the soil in accordance with the age of the plantation and the level of production [

4]. Fertilization must be based on the permanent follow-up of the level of soil supply with the requirements of the trees, the differentiated establishment of the fertilization system under the ratio the type, doses, and periods of fertilizer administration. The system of fertilization must also be differentiated depending on the species, cultivar, rootstock [

5].

Chemical fertilizers with phosphorus and potassium are an integral part of basic soil fertilization. The appropriate supply of phosphorus and potassium ensures the good growth of the planting material and especially the maturation of the wood [

6]. The insufficiency of these nutrients results in rapid growth, without the maturation of the wood. When the fruit trees are supplied with nitrogen, the lack of phosphorus and potassium causes the extension of the vegetation period and the under-ripening of the wood, so that the leaves of the trees do not fall until the arrival of frost, and the planting material is sensitive to frost. Phosphorus and potassium from fertilizers have a low mobility in the soil, their ions being retained by chemical processes for a long time near the place where they were placed [

7]. Therefore, to be effective, fertilizers with phosphorus and potassium must be incorporated to the depth of spreading of the root system. Among the chemical properties of the soil, determinants of the quality of the planting material, the most important are the reaction and the humus content [

8].

The annual consumption of nutrients from the soil in a nursery with a production of 50,000 trees per hectare is around 70-80 kg N, 15-20 kg P

2O

5 and 50-60 kg K

2O. Soils whose values of physical and chemical properties are within the limits considered optimal, in the geographical area where Romania is located, can annually pass into soluble forms 20-40 kg N, 5-10 kg P

2O

5 and 30-50 kg K

2O per hectare, insufficient quantities to obtain a high quality tree planting material. Trees in the nursery phase require nitrogen in large quantities to ensure growth [

9]. The phase of maximum nitrogen consumption corresponds to the phenophase of intense shoot growth. Towards the end of the vegetation period, the consumption of nitrogen must decrease in favor of the consumption of phosphorus and potassium [

10]. Nitrogen from chemical fertilizers is in very soluble forms, which move in the soil both by diffusion and by water flow. The doses and the time of application must be established so that the nitrogen in the fertilizers is found at the level of the spreading of the roots at the times and in the quantities required by the trees [

11].

It is known that the irrational application of fertilizers in the nursery, in large doses, in a unilateral and unbalanced way, the administration of some forms of fertilizers that do not correspond to the biological requirements of the species and soils can have negative effects, so that instead of the expected increases in tree production its decreases are recorded [

12].

Nitrogen is considered an essential and indispensable element for plant growth and development, with functions and presence in plant tissues noted over three centuries ago. Nitrogen is considered a main component of proteins and protides, which are a constituent part of the enzymes involved in energy and synthesis transformations in the plant [

13]. Nitrogen participates in building the molecular architecture of the substances that make up the organism’s genetic code, in growth processes and where growth occurs, protein substances are formed. With the previously stated essential roles, it can be concluded that nitrogen is a primary macro element (along with P and K) with determining roles in the quantitative and qualitative formation of agricultural and horticultural plant crops [

14]. Phosphorus participates in building the molecular architecture of nucleic acids, which make up the genetic code of cells. It has an essential role in the processes of phosphorylation, generating energy-rich compounds, such as adenosine triphosphoric acid, which through enzymatically controlled biochemical reactions release the energy needed for metabolic processes [

15]. Phosphorus intervenes in chlorophyll functions, participating in the synthesis of carbohydrates, as well as some fats and lipids. It favorably influences the processes of fruiting, transport, and deposition of carbohydrates in fruits, roots, tubers. It accelerates maturity and stimulates the development of the root system. Phosphorus is an element that increases the resistance of plants to adverse conditions (frost, diseases, falling and breaking, etc.) It increases the resistance of plants to drought, counterbalances the excess of nitrogen, the growth of the root system [

16]. According to these specific but also complex roles, phosphorus is attributed the quality of primary macro element with essential functions found in importance and effects alongside nitrogen and potassium. Due to its reduced mobility and the great possibilities of being fixed in chemical compounds with low solubility or insoluble, certain rules must be followed when applying phosphorus fertilizers, first, poorly soluble phosphorus fertilizers must be applied as close as possible to the tree roots [

17]. This is the most efficient method of improving their nutrition with phosphorus; adjusting the pH to values of 6-7 determines an increase in phosphorus mobility and, respectively, in its absorption by the trees; the repeated application of phosphorus fertilizers leads over time to the enrichment of the upper part of the soil in phosphorus and the advancement in depth of the area well supplied with phosphorus; application of easily soluble phosphorus fertilizers together with irrigation water [

18]. The natural cycle of phosphorus is different from that of nitrogen. Soils contain lower amounts of phosphorus than nitrogen or potassium. On the other hand, phosphorus tends to react with soil constituents to form insoluble compounds that are difficult for plants to access, which requires the application of fertilizers [

19]. Phosphorus deficiency slows down the synthesis of ribonucleic acid, which causes a decrease in protein formation, a slowdown in plant growth: the leaves remain small, purple-reddish spots or striations begin to appear and the leaf petiole elongates. In a more advanced phase, because of unfavorable conditions for nitrogen assimilation, the leaves turn yellow. In fruit trees there is a decrease in the formation of fruit buds and poor fruiting [

20].

Insufficiency or excess of P causes major disturbances in the synthesis, translocation, and accumulation of organic substances in plants. In the insufficient state, small and insufficient amounts of compounds with P are synthesized, which should accumulate the energy for the metabolic processes in the plant. Consequently, in this situation, the synthesis of proteins, carbohydrates and lipids is disturbed. N-NO

3 accumulates in plants at the expense of proteins [

21]. Excessive phosphating causes a deficiency of Zn and Cu and reduced accumulations of chlorophyll, carbohydrates, and proteins. Fruit trees have a P content in leaves of 0.3-0.9%, in fruit branches 0.2-0.4%, and in the trunk, old branches and roots of 0.09-0.3%. The rate of absorption of phosphorus ions from the soil solution by plant roots is determined by their concentration in the vicinity of active roots [

22]. This concentration, in turn, depends on the intensity of the nutrient diffusion processes and the displacement of the soil solution following the absorption of water by the plants. In horticultural practice, the aim is to increase the concentration of phosphorus in the liquid phase of the soil through the application of fertilizers and measures that contribute to increasing the coefficient of use of phosphorus in the soil (granulation, localized application, etc.) [

23].

Regarding the efficiency in relation to the presence of other ions in the soil, there is an interaction between phosphorus ions and other ions in the soil, which influences the efficiency and the coefficient of use of phosphorus fertilizers [

24]. The P/N interaction in the soil is due to some chemical interactions that increase the accessibility of phosphorus, some physiological interactions (photosynthesis, respiration, consumption) that increase the assimilation capacity, as well as a direct effect of some fertilizers that increase the solubility of phosphates. In the case of the P/K interaction, potassium salts increase the assimilability of phosphorus fertilizers. The effect of phosphorus fertilizers is also manifested in the following years, in relation to the dose used, the type of fertilizers and the soil conditions. Plants use 1/10 to ½ of the total phosphate fertilizers in the environment, and the rest accumulates in the soil in compounds that are more difficult to dissolve and less accessible to plants [

25].

Phosphorus, considered to have multiple nutritional roles and involved in the synthesis of some compounds but also in the proportionate growth and development of tissues and plants can be included among the elements that stabilize the resistance of plants to the attack of diseases and pests [

26].

Potassium, along with nitrogen and phosphorus, is one of the primary macro elements with an essential role in plant nutrition, with distinct and known physiological and metabolic functions. Potassium is necessary for plant growth and development and is found in all cells, tissues and organs of living plants, growth zones, cambial tissue, seeds. In the plant, most of it is in the form of ions (K+) [

18]. Due to its enzymatic roles largely channeled in the synthesis of high molecular weight carbohydrates (starch, cellulose) and proteins, it is very involved in increasing the resistance of plants to the attack of diseases and pests. Fertilization with K increases plant resistance to fungi, bacteria, viruses [

27]. The efficiency of potassium fertilizers increases when plants are supplied with assimilable forms of nitrogen and phosphorus. In fruit trees, the greatest yield increases are obtained when potash fertilizers are applied together with nitrogen fertilizers. As a fertilizer for plants, its role and efficiency have increased especially since the middle of the last century, when the theory and practice of uniform fertilizations were abandoned and the optimal and rational ones, in accordance with the requirements of soils and plants, were abandoned. In addition, the conditions of multi-year fertilizations only with N and P, ignoring the specific effects in this context of potassium, made the application of this element current and necessary, under the conditions of rational use of other elements [

20]. Quantitatively and qualitatively increased yields cannot be achieved without the application of potassium. Potassium is administered in all types of soil in the form of potash, having a content of 30-40% or 50% K

2O [

28]. Potassium plays an important role in the process of growth, fruiting, and tissue maturation. Mineral fertilizers can be applied in the form of dust, granules, granulated organo-minerals in liquid form. Its roles and importance as a nutrient are known, some of them since the last two centuries, and it is appreciated as the most important cation for plant organisms, especially since it is among the cations the most abundant and necessary for plant cells and tissues. However, unlike nitrogen and phosphorus, recognized as elements with predominantly plastic roles, potassium does not enter the composition of the main organic compounds in plant tissues and is found in cells mainly in an ionic state [

29]. Potassium is absorbed by plants in significant quantities, in some cases superior to other nutrients, including nitrogen. Unlike the other macro elements of primary or secondary order, potassium does not enter the composition of organic substances in plants. The presence of potassium in the cells of the roots at sufficiently high content levels, causes the easier absorption of water from the soil and its transfer to the central cylinder of the root and from there to the other organs of the plant. In this way, plants become more resistant to stressful drought conditions. Potassium regulates the intracellular pressure and the state of turgor of plant tissues, which causes the elongation of young tissues [

30].

The amount of potassium necessary for the complete realization of the life cycle of agricultural and horticultural crops is a net appropriation of the respective species and depends on their specific potassium consumption and on the size of the harvest obtained or expected [

31].

Regarding the need to ensure the necessary water in the nursery, it is known that water conditions the growth process of the planting material in the nursery [

32]. The decrease of the water content in the soil below certain limits causes a decrease in the water content of the plant, which at the level of the cell causes a decrease in its turgor The reduction of turgor has the effect of slowing down the processes of cell division, but especially slowing down the process of cell elongation which, in turn, affects the growth of leaves, shoots and roots [

33]. The decrease in cellular turgor influences the photosynthetic activity by reducing the surface of the leaves and by the productivity of photosynthesis per surface unit, reducing the degree of opening of the stomata. In the nursery, especially by promoting the new methods of rapid multiplication, there are many situations when the soil must be well supplied with water, to create conditions for the growth of the fruit tree planting material [

34]. The distribution of precipitation on the territory of Romania ensures in some areas and periods of the year an optimal supply of soil with water.

However, there are also many years, especially in areas with annual rainfall of less than 600 mm, when there are significant water deficits in the soil that negatively influence the growth of the nursery stock, and as such the application of irrigation is necessary

The practical value of the research consists in the application of different rules of irrigation and fertilization on the plum seedlings in the nursery, for the development of the horticultural field and raising it to a productive level. This research is a current one, in the context of the need to provide the soil in the nursery with nutrients and water, to obtain large productions of high-quality tree planting material. By applying different irrigation and fertilization rules, they will consist in obtaining a healthy and vigorous tree planting material. It is known that the irrational application of fertilizers in large doses, in a unilateral and unbalanced way, the administration of some forms of fertilizers that do not meet the biological requirements of the species and soils can have negative effects, so that instead of the expected increases in production, decreases are recorded. Regarding irrigation, excess water always has adverse influences on the growth and fruiting of fruit plants in general. It can favor the extension of the vegetation period in autumn, the decrease in resistance to the attack of cryptogamic diseases in general, the decrease in the volume of the root system and its functioning until asphyxiation.