1. Introduction

Engineering has emerged as a cornerstone in addressing pressing global health challenges, as emphasized in UNESCO’s Engineering for Sustainable Development report (2021), which recognizes the discipline as a central pillar of the 2030 Agenda. Among the Sustainable Development Goals, SDG 3 — “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” — underscores the need for accessible and affordable technologies to strengthen medical diagnostics and healthcare delivery [

1]. Within this framework, brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) have gained increasing international attention for their potential to revolutionize human–machine interaction in clinical, rehabilitative, and assistive domains. Beyond their scientific and societal impact, BCIs are also economically significant: the global market is projected to reach USD 2.21 billion by 2025 and expand further to USD 3.60 billion by 2030, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.29 [

2]. This convergence of societal need, technological innovation, and market growth highlights BCIs as a key enabler for sustainable health solutions.

Within this landscape, electroencephalography (EEG) has become a foundational technology for BCI implementation, owing to its non-invasive nature, low cost, portability, and high temporal resolution [

3]. EEG captures the brain’s electrical activity through scalp-mounted electrodes and enables the use of advanced signal processing techniques such as event-related potentials (ERPs), which are widely used to assess cognitive and motor functions [

4]. These features have established EEG as the technological backbone of many modern BCI platforms, allowing for the decoding of neural signals to control external devices without requiring muscular input [

5]. Among the various paradigms, motor imagery (MI)—the mental rehearsal of movement without physical execution—has demonstrated remarkable clinical potential in post-stroke rehabilitation, neuroprosthetic control, and assistive technologies such as robotic wheelchairs and virtual spellers [

6].

Despite its versatility, EEG-based BCI systems face inherent structural limitations, primarily due to the physical and physiological nature of the recorded brain signals [

7]. These constraints compromise both signal quality and interpretability, directly affecting their clinical and functional applicability [

8]. One of the most critical challenges is inter-subject variability, which introduces significant inconsistency in neural activation patterns and undermines the generalization of classification models used in BCI [

9,

10]. This variability has been strongly linked to the phenomenon known as BCI illiteracy, where a substantial subset of users is unable to gain intentional control of the system, even after repeated training sessions [

11,

12]. Beyond its technical implications, this limitation poses a fundamental challenge to the inclusion and scalability of BCI technologies in real-world clinical settings, where system adaptability to diverse neurophysiological profiles is essential [

13]. Another key obstacle in the development of EEG-based BCI systems is their limited spatial resolution, which is inherently constrained by volume conduction effects. Unlike imaging modalities such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or Magnetoencephalography (MEG), EEG suffers from spatial distortions because neural electrical signals must traverse multiple layers with varying conductivities—such as the skull and scalp—before being recorded at the surface electrodes [

14]. This biophysical phenomenon results in signal mixing across electrodes, making it difficult to accurately localize cortical activity [

14]. Consequently, spatial specificity is reduced in applications that require fine-grained identification of motor or sensory regions, ultimately limiting the system’s performance in rehabilitation, neurofeedback, and precision control tasks [

15].

In this context, various classical signal processing and machine learning methods have been proposed to improve signal quality and extract discriminative features from EEG recordings, particularly in MI paradigms. Among the earliest approaches, time–frequency domain techniques such as the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) [

16] and the wavelet transform [

17,

18] have proven effective in decomposing EEG signals into more informative components by capturing their non-stationary nature. These tools facilitate the identification of relevant brain rhythms, particularly the

(8–12 Hz) and

(13–30 Hz) bands, which have been widely linked to movement execution and motor imagery [

19]. Additionally, the filter bank common spatial patterns (FBCSP) approach extends this principle by dividing the EEG into multiple frequency sub-bands and applying the CSP algorithm to each of them, thereby enhancing class discrimination [

20]. While these strategies improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), their effectiveness depends on fixed or heuristically defined frequency ranges, which limits their adaptability to inter-subject spectral variability [

21]. Furthermore, CSP variants—such as regularized CSP, discriminative CSP, and sparse CSP—attempt to mitigate overfitting and improve generalization, but remain noise-sensitive and often require subject-specific calibration [

22]. Crucially, these approaches provide limited robustness to the spatial distortions inherent in EEG, caused by volume conduction, which restricts their ability to resolve cortical sources with precision and thus limits their performance in tasks requiring spatial specificity [

23].

Conversely, recent approaches have leveraged deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), to extract hierarchical representations from raw EEG signals. Architectures such as EEG network (EEGNet) [

24], shallow convolutional network (ShallowNet) and deep convolutional network (DeepConvNet) [

25], and temporal–channel fusion network (TCFusionNet) [

26] have shown potential in MI classification by learning spatial and temporal patterns without the need for manual feature engineering. These models exhibit increased robustness to noise and, in some cases, can implicitly compensate for spatial distortions through convolutional kernels. Building on this foundation, kernel-based regularized EEGNet (KREEGNet) [

27] introduces explicit spatial encodings and specialized convolutional kernels to enhance cortical sensitivity, offering a more targeted solution to the spatial resolution limitations of EEG. Nevertheless, the performance of these architectures remains highly dependent on large, high-quality datasets, and deeper networks are particularly prone to overfitting. Moreover, achieving robust model generalization remains a significant challenge, particularly due to high inter-subject variability in EEG patterns. As a result, most approaches still rely on subject-specific calibration or employ transfer learning strategies to adapt models across individuals [

28]. Beyond CNNs, cutting-edge research has begun to explore attention mechanisms, transformer architectures, and generative modeling [

29]. Transformer-based models have shown strong performance in capturing long-range temporal dependencies and improving generalization across subjects. For instance, convolutional Transformer network (CTNet) [

30] leverages multi-head self-attention to dynamically extract discriminative spatial-temporal features. Similarly, spatial–temporal transformer models have demonstrated robustness in multi-scale temporal feature extraction [

31]. Complementary generative approaches, including autoencoders and variational autoencoders (VAEs), have been employed for nonlinear denoising and unsupervised feature learning [

32,

33]; however, these models inadvertently discard class-discriminative information unless properly regularized [

33]. More recently, multimodal and diffusion-based transformer models have been proposed to integrate spatial, temporal, and topological EEG dynamics [

34], though their architectural complexity and computational demands may limit their application in real-time or clinical settings [

32].

In addition to approaches based on local or spatial features, EEG representation through connectivity models has been extensively explored, including spectral, structural, directed, and functional connectivity. Spectral connectivity, based on measures such as coherence and spectral entropy, allows for the capture of phase and power relationships between cortical regions, but may be sensitive to noise and the choice of frequency bands [

35]. Structural connectivity, typically derived from neuroimaging techniques such as MRI, is difficult to obtain from EEG and is rarely integrated directly into non-invasive applications [

36]. Directed connectivity aims to identify causal relationships between regions using metrics like partial directed coherence or dynamic causal modeling [

37]; although it enhances interpretability, it often entails significant computational complexity. Functional connectivity, by contrast, has been the most widely applied in EEG contexts due to its ability to model statistical dependencies. As a recent advancement, Gaussian functional connectivity has been proposed as a more robust representation for capturing nonlinear spectral-domain relationships. This formulation was employed in the kernel cross-spectral functional connectivity network (KCS-FCNet) model [

38], which integrates kernelized functional connectivity to enhance class discrimination in motor imagery paradigms. Overall, although various forms of connectivity have been explored in conjunction with deep learning, their direct application has yet to mature to a point that effectively addresses critical challenges such as inter-subject variability and limited spatial resolution [

36].

Here, we introduce EEG-GCIRNet—a Gaussian connectivity–driven EEG imaging representation Network. This framework is designed to transform functional connectivity patterns into a robust image-based representation for MI classification using a variational autoencoder. Unlike conventional approaches, our method creates a rich representation by generating topographic maps from Gaussian functional connectivity, which model nonlinear spatial–functional dependencies across brain regions. Our EEG-GCIRNet framework comprises three key stages:

- –

Image-based encoding: Gaussian connectivity-based image representations are encoded into a shared latent space that captures complementary spatio-temporal and frequency information, enabling more discriminative and interpretable feature representations.

- –

Multi-objective training: The model is optimized through a composite loss that jointly enforces reconstruction fidelity, classification accuracy, and latent space regularization, enhancing robustness to noise and mitigating inter-subject variability.

- –

VAE-based interpretability: The framework’s variational autoencoder design enables direct qualitative assessment. By analyzing the reconstructed topographic maps and visualizing the latent space, we can validate the physiological relevance of the learned features and confirm the model’s ability to create a well-separated feature space, enhancing overall transparency.

Experimental evaluations on benchmark MI datasets demonstrate that EEG-GCIRNet consistently outperforms state-of-the-art baselines, achieving superior classification accuracy. Moreover, interpretability analyses reveal distinct functional connectivity structures that align with known motor cortical regions, offering neurophysiological validation of the model’s learned representations. As such, the proposed framework advances the development of robust and interpretable EEG-based BCIs, paving the way for adaptive neurotechnologies in rehabilitation, assistive communication, and motor recovery. By combining multimodal encoding, multi-objective learning, and explainable AI, EEG-GCIRNet contributes a reproducible and scalable paradigm for addressing two of the most persistent challenges in EEG-based BCI research: inter-subject variability and limited spatial specificity.

The agenda is as follows.

Section 2 describes the materials and methods.

Section 4 presents the experiments and results.

Section 5 provides the discussion. Finally,

Section 6 outlines the conclusions and future work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. GIGAScience Dataset for EEG-based Motor Imagery

The Giga Motor Imagery–DBIII (GigaScience) dataset, publicly available at

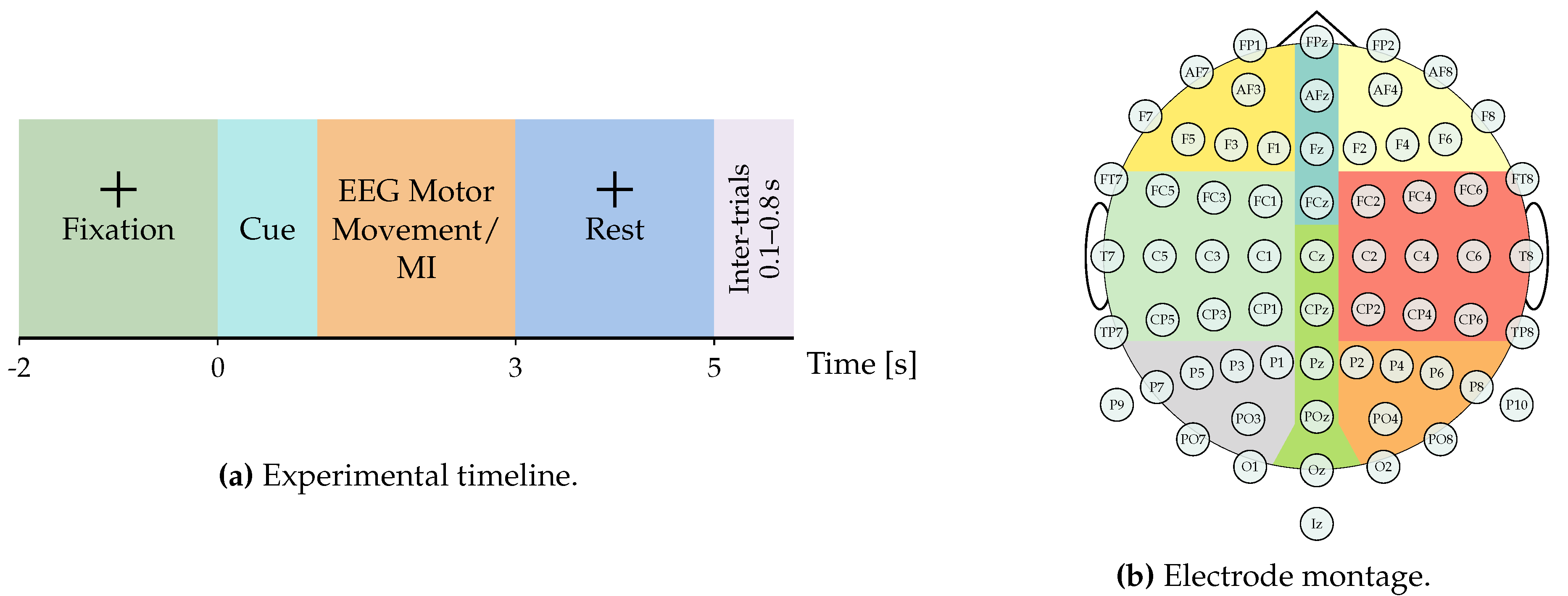

http://gigadb.org/dataset/100295 (accessed on 1 July 2025), provides one of the most comprehensive EEG corpora for MI analysis. The dataset comprises recordings from 52 healthy participants (50 with usable data), each performing a single EEG-MI session. Every session consists of five to six experimental blocks, with each block containing approximately 100–120 trials per class. Each trial spans seven seconds and follows a fixed timeline: an initial blank screen (0–2 s), a visual cue indicating either left- or right-hand MI (2–5 s), and a concluding blank interval (5–7 s). Inter-trial intervals vary randomly between 0.1 s and 0.8 s to mitigate anticipatory bias, as illustrated in

Figure 1. EEG signals were recorded at a sampling frequency of 512 Hz using a 64-channel cap arranged according to the international 10–10 electrode placement system. In addition to the MI sessions, the dataset includes recordings of real motor execution and six auxiliary non-task-related events—eye blinks, vertical and horizontal eye movements, head motions, jaw clenching, and resting state—enabling a broader exploration of EEG noise sources and artifact correction. This multimodal composition makes the GigaScience particularly valuable for benchmarking advanced deep learning and connectivity-based EEG decoding frameworks, as it supports both intra-subject and inter-subject generalization studies. [subfigure]justification=centering

Each MI trial is structured for the proposed framework. Let denote a multichannel EEG and its associated MI target label, where represents the EEG recording with C spatial channels and temporal samples, and is a one-hot encoded vector indicating the MI class among Q possible categories.

2.2. Laplacian Filtering and Time Segmentation

To enhance the spatial resolution and mitigate the volume conduction effects inherent in EEG recordings, a Surface Laplacian filter is applied to each trial

. This filter acts as a spatial high-pass filter by estimating the second spatial derivative of the scalp potential at each electrode

with respect to its neighbors

, where

. Following the methodology in [

39], this is achieved by using spherical splines to project the electrode positions onto a unit sphere, which allows for the interpolation of scalp potentials via Legendre polynomials. The interaction between any pair of electrodes

is modeled as:

where

is the Legendre Polynomial of order

n,

is the highest polynomial order considered,

is a smoothness constant, and

are the 3D electrode positions normalized to a unit-radius sphere. The cosine distance is defined as

.

The Laplacian-filtered EEG data, denoted as

, is subsequently computed using the weighting matrices derived from the spline interpolation:

where

is a column vector of ones,

is the identity matrix, and

is a regularization parameter. The matrix

is a regularized (smoothed) version of

. The weighting matrices

hold the elements derived from Equation (

1), with their specific values determined by the parameter

as follows:

where

and

are the elements of matrices

and

, respectively. This filtering step produces a spatially enhanced representation

that serves as input for the subsequent feature extraction stages.

Further, to focus the analysis exclusively on the period of active motor imagery, the Laplacian-filtered signal

is temporally segmented. The time window corresponding to the MI task, specifically between

and

seconds of each trial, is retained. Let

and

be the start and end times of the MI segment, and

be the sampling frequency, the segmented signal

is obtained as:

where the slicing notation

indicates the selection of temporal samples from the start index to the end index. For brevity, this segmented signal will be denoted as

in the subsequent sections.

2.3. Kernel-Based Cross-Spectral Gaussian Connectivity for EEG Imaging

To model the mutual dependency between EEG channels, we consider any two channels

from a given trial

(where

). Their mutual dependency can be captured using a stationary kernel

, which maps both signals into a reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS) via a nonlinear feature map

[

40]. Indeed, according to Bochner’s theorem, a sufficient condition for the kernel

to be stationary is that it admits a spectral representation [

41]:

where

is a frequency vector, and

is the cross-spectral density between

and

, derived from the spectral distribution

.

Building on this spectral representation, the cross-spectral power within a specific frequency band

can be computed via the Fourier transform of the kernel:

where

denotes the Fourier transform. This spectral formulation allows capturing both linear and nonlinear dependencies in the frequency domain, making it particularly useful for analyzing brain signals.

A widely used choice for

is the Gaussian kernel, which ensures smoothness, locality, and analytic tractability [

42]:

where

is a bandwidth hyper-parameter.

Inspired by the kernel-based spectral approaches introduced in [

38,

43], we compute a Gaussian kernel cross-spectral connectivity estimator to encode spatio–frequency interactions among pairwise EEG channels. Specifically, for each EEG channel

c, a band-limited spectral reconstruction is obtained as:

where

denotes a given frequency bandwidth (rhythm). Then, the Gaussian Function Connectivity (GFC) matrix

is derived to quantify the degree of similarity between the spectral representations of all channel pairs, as:

where

is a Gaussian kernel with scale parameter

. To ensure adaptive sensitivity across rhythms,

is estimated as the median of all pairwise Euclidean distances between spectral reconstructions

and

,

. This formulation provides a data-driven normalization of connectivity strength, enabling robust comparison across heterogeneous EEG rhythms and subjects.

Afterward, we propose to compute an EEG connectivity flow from

, preserving a direct one-to-one correspondence with the electrode spatial configuration. Specifically, the GFC flow vector

holds elements:

where each element

represents the mean functional coupling of channel

c with all other channels within the given frequency band

. The latter compresses the pairwise connectivity information into a compact, channel-wise flow representation while retaining the spatial and spectral data patterns.

To ensure a consistent feature scale for the imaging stage, the GFC flow vectors are normalized across the entire training dataset. Specifically, a channel-wise Min-Max normalization is applied, scaling the connectivity values of each channel to a uniform range of . This procedure preserves the relative topography of neural connectivity while standardizing the input scale, yielding the normalized flow vector for each trial.

2.4. Topographic Map Generation

The final feature engineering step transforms the one-dimensional GFC flow vectors into two-dimensional topographic images, creating a data representation suitable for convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures. For each trial, this process converts the normalized flow vector from each frequency band into a corresponding topographic image .

This transformation is accomplished via spatial interpolation guided by Delaunay triangulation. First, the set of 2D scalp coordinates of the electrodes, , is triangulated. This partitions the electrode layout into a mesh of non-overlapping triangles, where the circumcircle of each triangle contains no other electrode points. This triangulation provides a structured grid for interpolating the connectivity values, where each element is associated with its corresponding coordinate .

To generate the final image, the value

for each pixel is computed using barycentric interpolation within its enclosing triangle

:

where

is the connectivity value at vertex

, and

are the barycentric coordinates of

satisfying

and

. This procedure is applied across all pixels to render the smooth topographic map

. The resulting set of four maps (one for each frequency band) is then stacked to form a multi-channel image, which serves as the final input to the deep learning model.

2.5. EEG-GCIRNet: Multimodal Architecture

The proposed model is a variational autoencoder (VAE) designed to process topographic maps derived from functional connectivity representations. Its architecture relies on a single input stream that learns to extract and encode the most relevant spatial features from the maps, which are then projected into a shared latent space where a multivariate Gaussian distribution is modeled. From this latent space, the model simultaneously performs reconstruction of the topographic maps and classification of motor imagery tasks. These objectives are integrated within a composite loss function that balances reconstruction fidelity, classification accuracy, and latent space regularization. This approach enables the learning of robust and interpretable latent representations capable of capturing discriminative spatial relationships and adapting to the variability and noise inherent in EEG signals.

The core of our framework is a VAE based on the LeNet-5 architecture, which is partitioned into three functional blocks: an encoder, a decoder, and a classifier, all operating on the shared latent space. Let be the multi-channel input image for a given trial, formed by stacking the B topographic maps (one for each frequency band).

The encoder, defined as a function

parameterized by

, maps the input image

Y to the parameters of the posterior distribution

. This transformation is realized through a composition of functions, where each function represents a layer in the network:

Here,

and

are convolutional layers with ReLU activation,

and

are average pooling layers, and

is a fully connected layer with ReLU activation after flattening the feature maps. The resulting hidden representation

is then linearly transformed to produce the mean vector

and the log-variance vector

of the latent space:

The decoder, defined as a function

parameterized by

, reconstructs the original input image

from a latent vector

. Its architecture mirrors the encoder by composing functions that progressively up-sample the representation to the original image dimensions:

Here, is a fully connected layer followed by a reshape operation, is a transposed convolutional layer with ReLU activation, and is a final transposed convolutional layer with a Sigmoid activation to ensure the output pixel values are in a normalized range.

Concurrently, the classifier, a function

parameterized by

, predicts the MI task label probabilities

from the same latent vector

z. It is implemented as a multi-layer perceptron:

Formally, the latent vector

for a given input sample

i is computed using the reparameterization trick:

where

and

denote the mean and variance of the approximate posterior distribution learned by the encoder for sample

i, and

is drawn from a standard normal distribution. The exponential term ensures the sampled standard deviation remains strictly positive.

The total objective function,

, is defined as a weighted sum of the three loss terms:

where

where

,

, and

are hyperparameters controlling the contribution of each term. The first component,

, is the normalized mean squared error (NMSE), which evaluates reconstruction accuracy by comparing the original topographic maps (

) and their reconstructions (

), normalized by the dataset’s variance (

is the mean image). The Frobenius norm,

, is used for the image-wise error. The second term,

, represents the normalized binary cross-entropy (NBCE). It penalizes misclassifications between the true one-hot labels (

) and predicted probabilities (

), while adjusting the loss based on the entropy over an ideal, non-informative prediction (e.g., a uniform distribution

). This maintains a balanced contribution from all classes. Finally, the third term,

, is the normalized Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between the approximate posterior

and a unit Gaussian prior

. This regularizes the latent space, promoting smoothness and disentanglement in the learned representations.

This KL divergence term encourages the latent representations to follow a standard normal distribution, promoting structure and generalization. The use of in the denominator prevents this term from dominating the loss in large batches. Taken together, these components ensure that the model jointly optimizes for faithful reconstruction, discriminative performance, and a well-regularized latent structure—crucial for interpretable and generalizable multimodal brain–computer interfaces.

The model is trained by solving the following optimization problem:

where

denotes the complete set of trainable parameters in the encoder, decoder, and classifier, respectively.

3. Experimental Set-Up

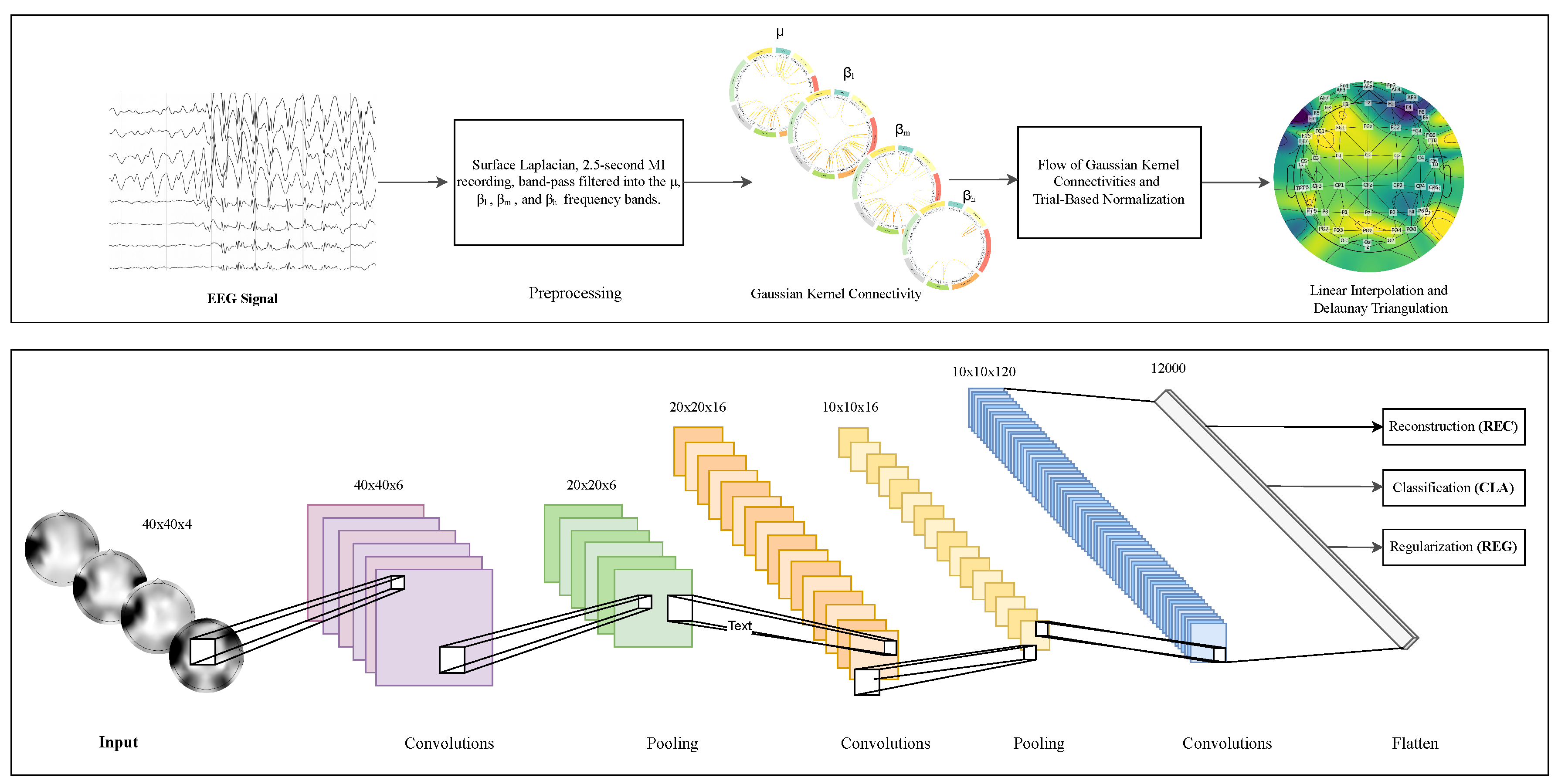

This work presents EEG-GCIRNet, a framework for MI classification built upon topographic maps derived from functional connectivity. The proposed methodology, illustrated in

Figure 2, comprises three primary stages: (i) preprocessing raw EEG signals to compute GFC-based flow vectors; (ii) generating 2D topographic maps from these vectors; and (iii) processing the resulting images with a deep learning architecture for simultaneous classification and reconstruction.

3.1. Stage 1: Signal Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

First, an average reference was applied, which included the original reference electrode to ensure the data retained full rank. Subsequently, a fifth-order Butterworth bandpass filter was applied in the

Hz range. To reduce computational load and maintain consistency across the evaluated deep learning models, the filtered signals were resampled from 512Hz to 128Hz [

38,

44]. This entire pipeline was applied to a subset of 50 subjects from the original dataset; participants 29 and 34 were excluded due to data availability constraints.

Building upon this preprocessed data, the feature engineering process involves applying a Surface Laplacian filter to enhance the spatial resolution of the signals. The data is then temporally segmented to isolate the active MI period, retaining the window from to seconds. This segmented data is further decomposed via band-pass filtering into four functionally distinct frequency bands: (Hz), low-beta (, Hz), mid-beta (, Hz), and high-beta (, Hz). For each frequency band, GFC is computed to quantify the functional relationships between all channel pairs. The resulting connectivity information is then condensed into a normalized, channel-wise flow vector for each band.

3.2. Stage 2: Topographic Map Generation

The second stage of the pipeline transforms the one-dimensional, GFC-based flow vectors into a two-dimensional, image-based representation suitable for processing with a CNN. This conversion is critical as it re-introduces the spatial topography of the EEG electrodes, allowing the model to learn spatially coherent features.

This transformation was achieved via spatial interpolation, a process implemented using the visualization utilities within the MNE-Python library

1. For each frequency band, the corresponding flow vector’s values are mapped to the

coordinates of the EEG electrodes. A mesh is then constructed over these coordinates using Delaunay triangulation. The pixel values for the final topographic map are subsequently estimated using linear barycentric interpolation within this mesh.This procedure is repeated for each of the four frequency bands (

,

,

, and

), yielding a set of four distinct topographic maps per trial. These maps are then stacked along the channel dimension to form a single, multi-channel image of size

. This resulting data structure serves as the final input to the EEG-GCIRNet architecture, providing a rich, spatio-spectral representation of the brain’s functional connectivity during motor imagery.

3.3. Stage 3: EEG-GCIRNet Architecture and Training

The core of this model is a VAE with a convolutional architecture inspired by LeNet-5. This architecture is composed of three interconnected functional blocks operating on a shared latent space: an encoder, a decoder, and a classifier.

The encoder block consists of two sequential pairs of convolutional and average pooling layers, which extract hierarchical spatial features from the input image. These features are then flattened and passed through a dense layer to produce a compact representation, which in turn parameterizes the mean (

) and log-variance (

) vectors of the latent space. The decoder mirrors this structure using transposed convolutional layers to upsample the latent representation back to the original image dimensions. Concurrently, the classifier, a simple multi-layer perceptron, operates on the same latent vector to perform the final classification. The detailed layer-wise configuration of the EEG-GCIRNet is summarized in

Table 1.

The EEG-GCIRNet model was trained end-to-end by optimizing the composite loss function described in sub

Section 2.5. The training was performed using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of

. The hyperparameters that weight the loss components were set using

KerasTuner framework to ensure a balanced contribution from reconstruction, classification, and regularization objectives during training. The model was trained for a total of 200 epochs with a batch size of 64. An early stopping mechanism was employed with a patience of 10 epochs, monitoring the validation loss to prevent overfitting and save the model with the best generalization performance. The dataset was split using a subject-wise cross-validation scheme to ensure that the training and testing sets were independent at the subject level.

3.4. Evaluation Criteria

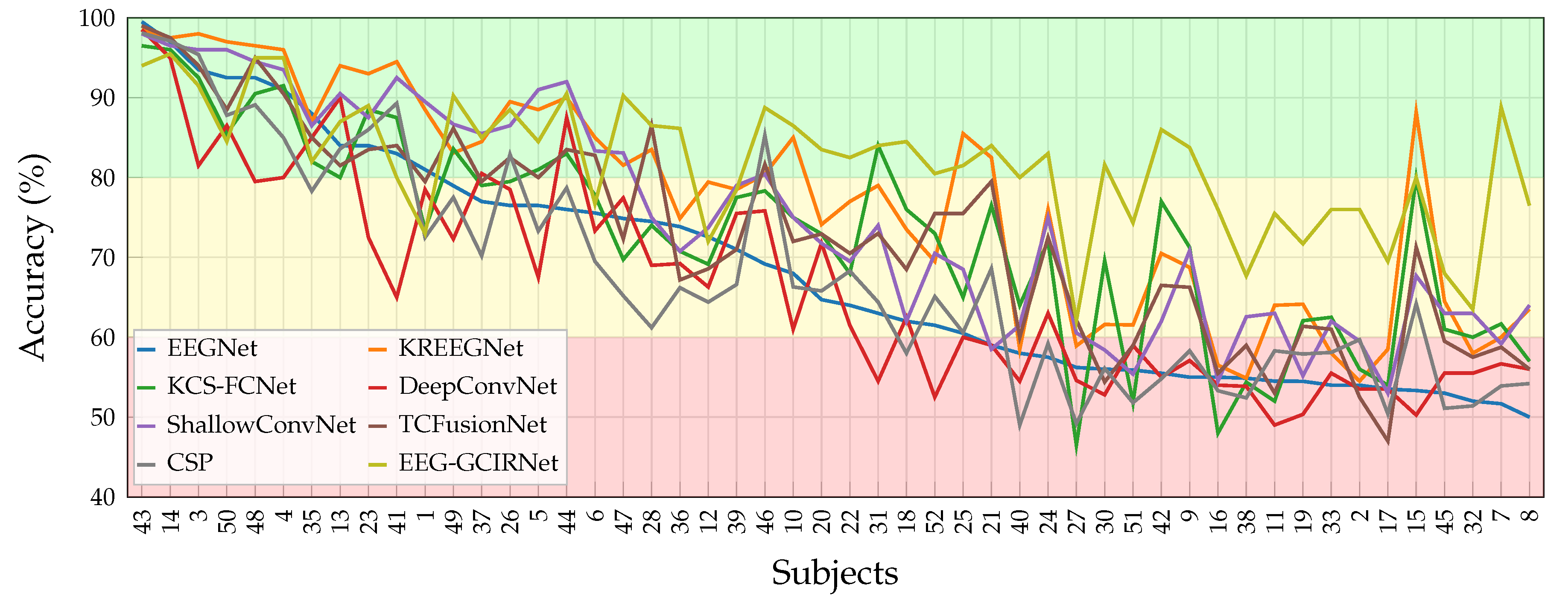

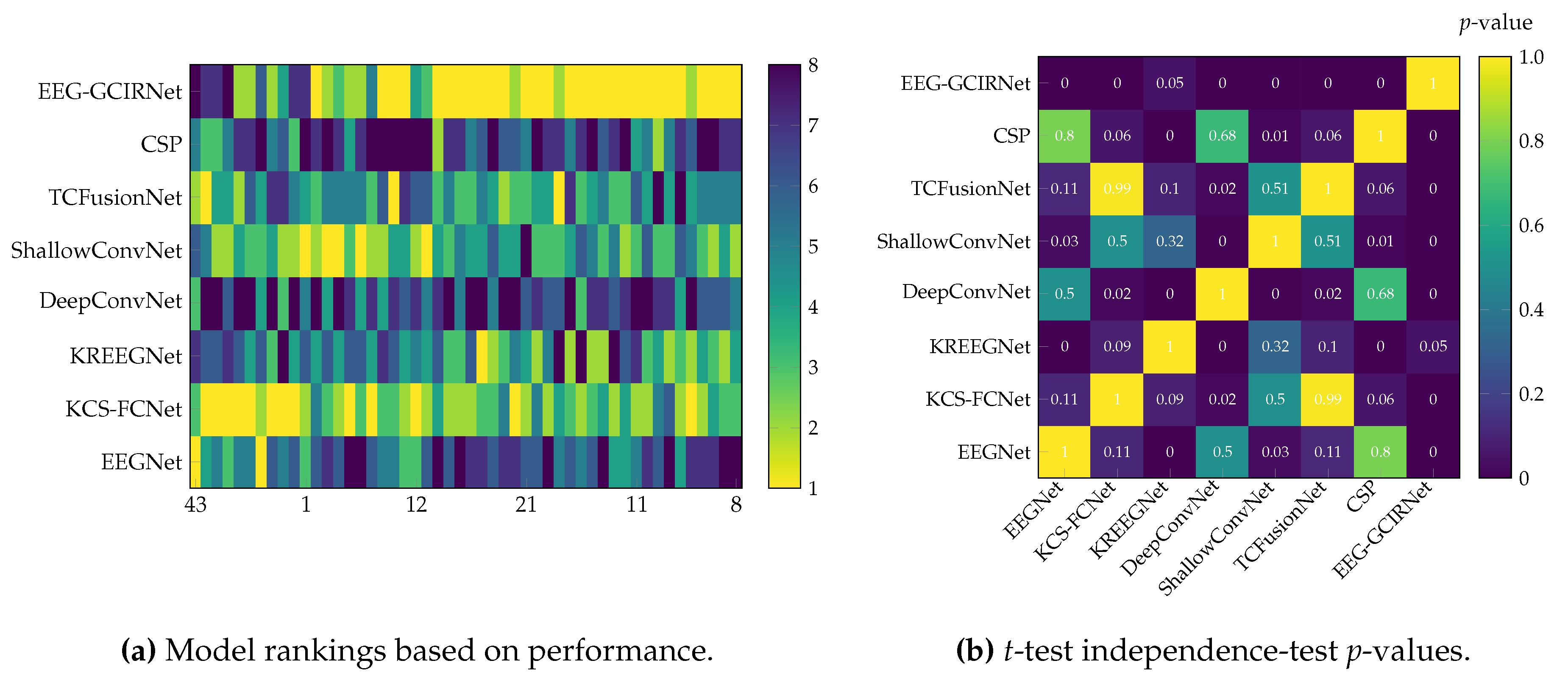

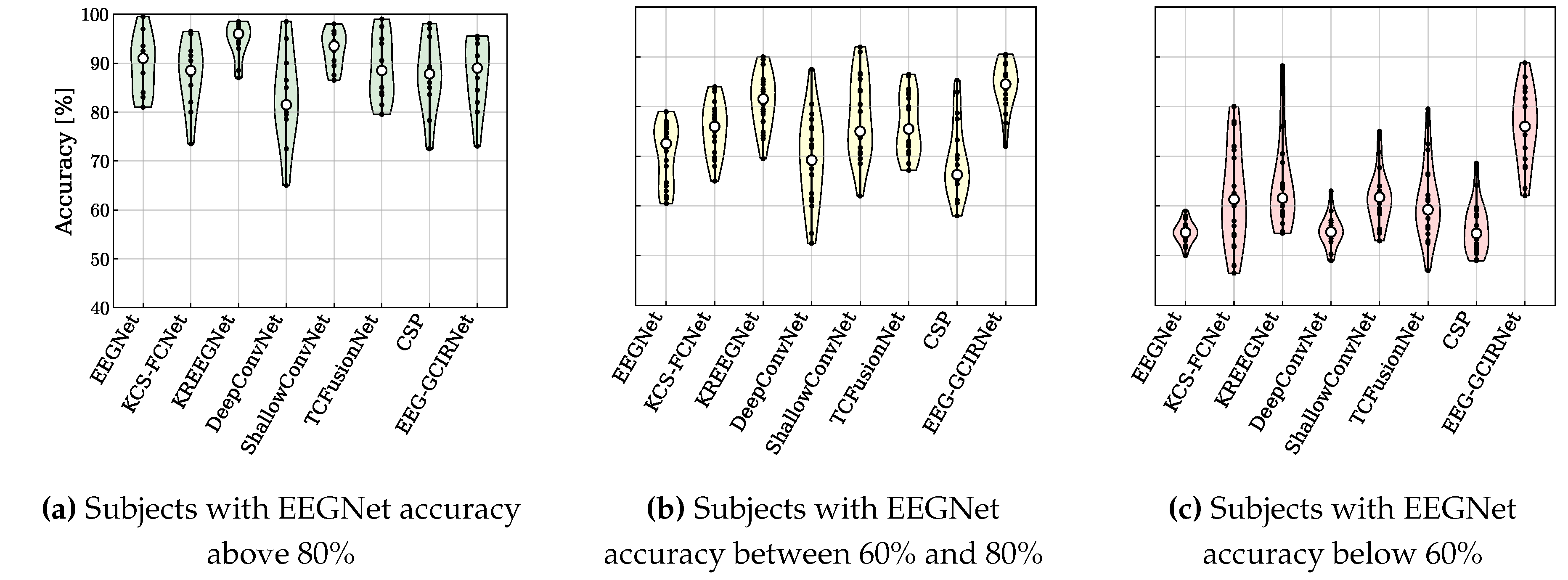

The performance of the proposed EEG-GCIRNet was rigorously evaluated using a multi-faceted approach. The primary quantitative metric was subject-specific classification accuracy, which was benchmarked against seven baseline and state-of-the-art models. To validate the findings, a robust statistical framework was employed, using a Friedman test to assess overall significance, followed by post-hoc pairwise t-tests for direct model comparisons. The framework’s robustness and generalization capabilities were further analyzed by stratifying subjects into “Good” (with EEGNet accuracy above 80%), “Mid” (with EEGNet accuracy between 60% and 80%), and “Bad” (with EEGNet accuracy below 60%) performance groups, allowing for a targeted assessment of its effectiveness across varying EEG signal qualities.

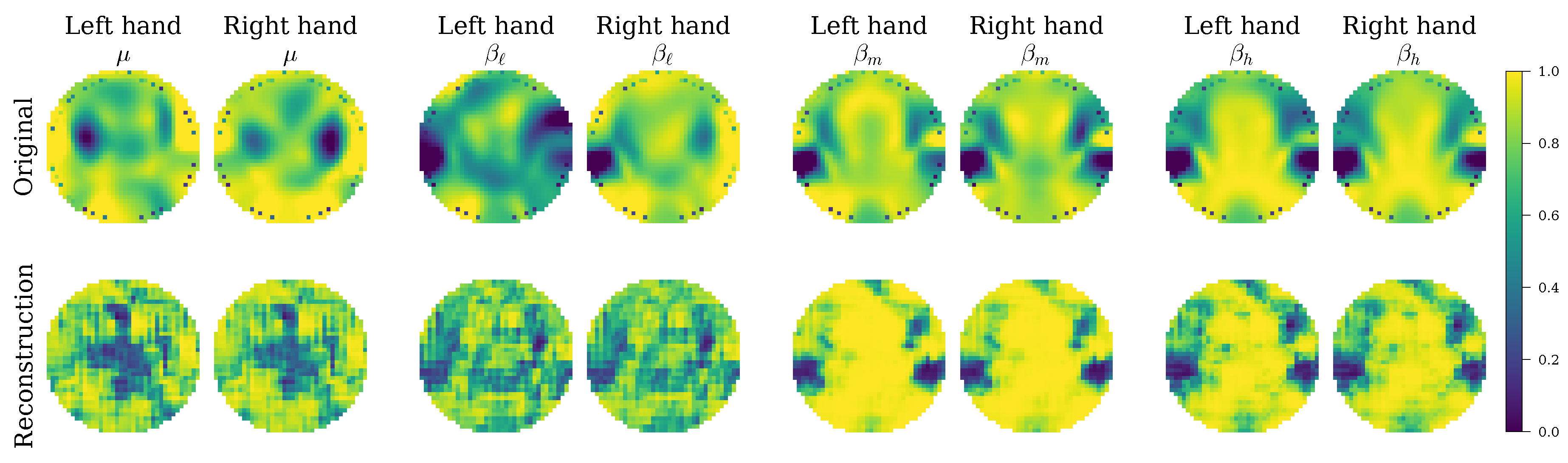

Beyond quantitative metrics, the evaluation delved into the model’s interpretability by leveraging its variational autoencoder architecture. This qualitative assessment involved two key methods: first, a visual analysis of the reconstructed topographic maps to confirm that the model learned physiologically relevant spatio-spectral patterns; and second, the visualization of the latent space using t-SNE projections to directly inspect the quality of class separability and feature disentanglement. This combined quantitative and qualitative evaluation provides a holistic validation of the EEG-GCIRNet framework, covering its accuracy, statistical significance, and the meaningfulness of its learned internal representations.

5. Discussion

The results obtained with the proposed EEG-GCIRNet architecture provide valuable insights into how model design and latent regularization can jointly address key challenges in motor imagery decoding. This study demonstrated that by transforming functional connectivity into an image-based representation and processing it with a variational autoencoder, it is possible to create a BCI framework that is not only highly accurate but also robust and interpretable. The model achieved remarkable performance across subjects, reaching the highest average accuracy () and the lowest inter-subject variability among all evaluated methods, confirming the efficacy of this unimodal, VAE-based approach.

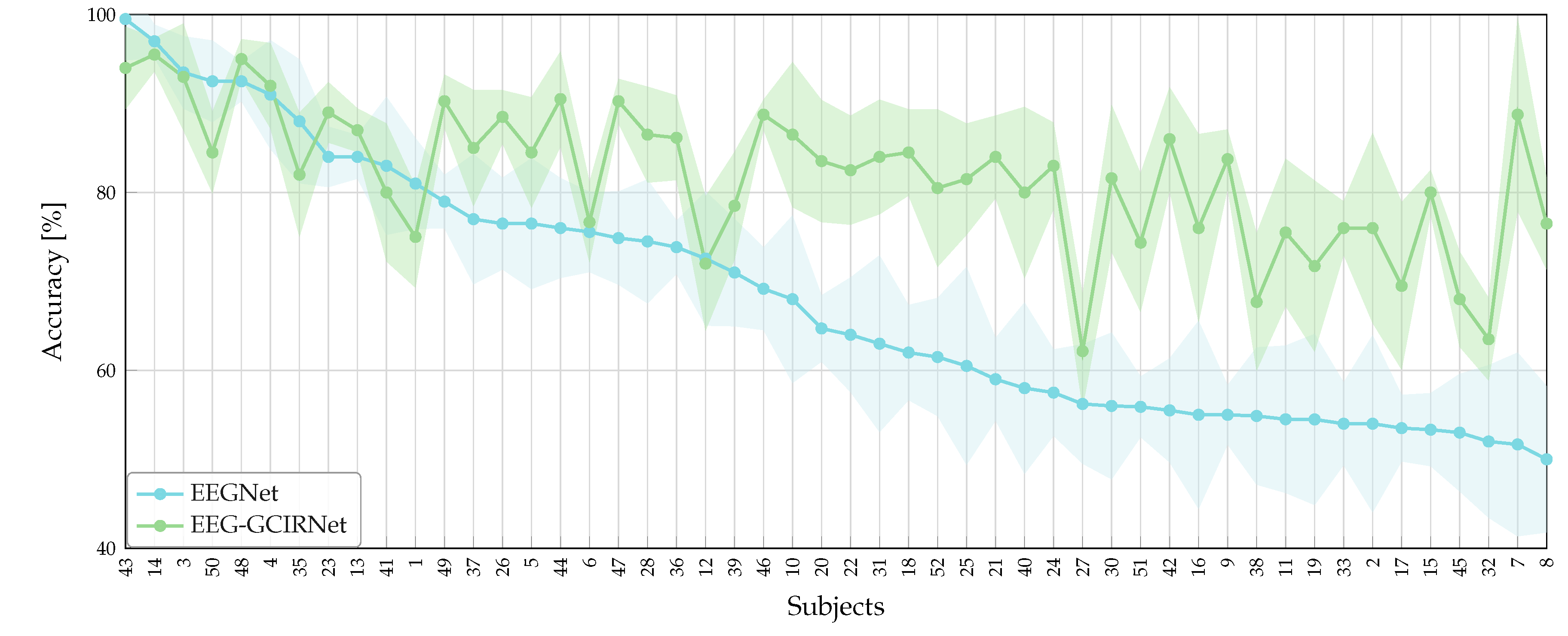

A key contribution of this work lies in its direct response to the critical challenges of inter-subject variability and “BCI illiteracy”. The most compelling finding was the complete elimination of the “Bad” performance group (

Figure 5), coupled with substantial accuracy gains of

and

pp for the “Bad” and “Mid” groups, respectively (

Table 4). This demonstrates the profound robustness of EEG-GCIRNet in handling noisy or low-separability EEG signals, where conventional architectures typically fail. By elevating the performance of these challenging subjects, the framework serves a corrective function, suggesting a promising path toward more inclusive and reliable BCI systems that can adapt to a wider range of users.

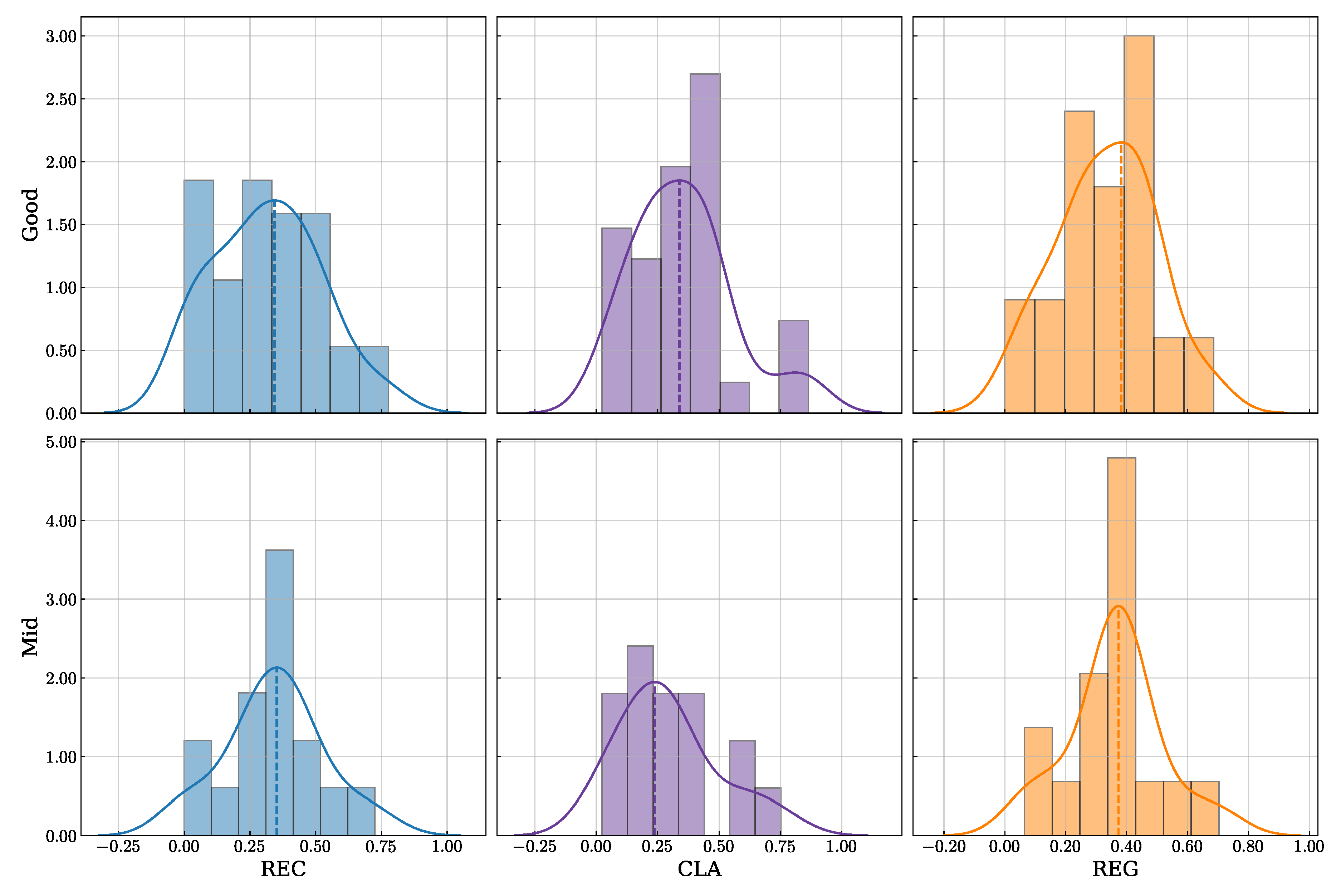

The mechanism underlying this robustness appears to be the model’s sophisticated, adaptive learning strategy. The analysis of the loss weight distributions (

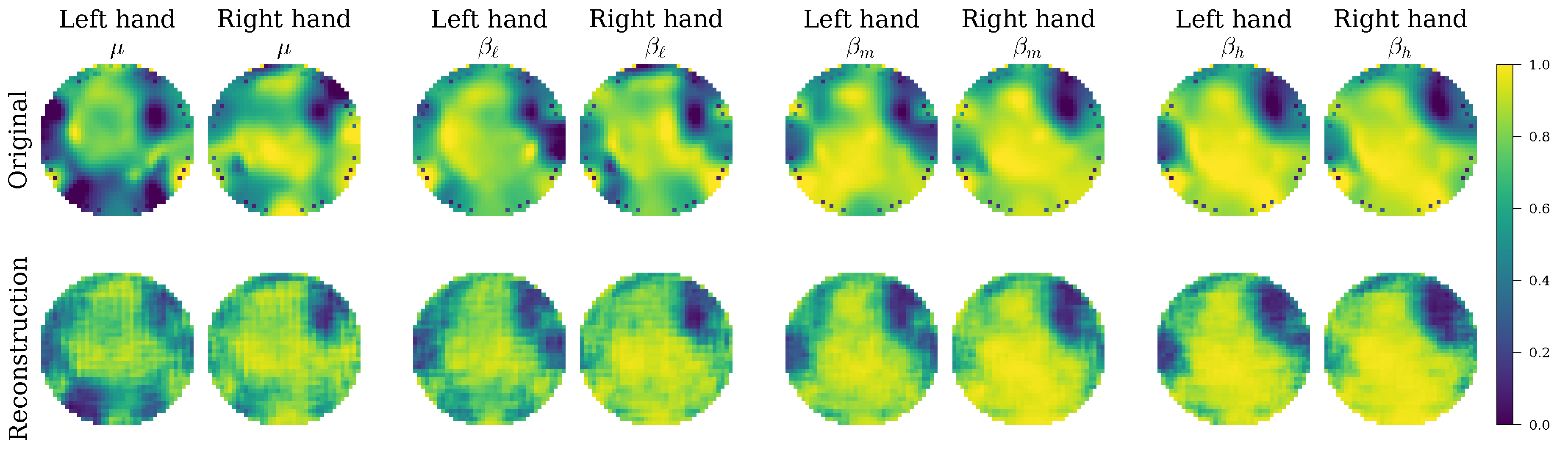

Figure 7) revealed that EEG-GCIRNet is not a static “black box” but dynamically reorganizes its optimization priorities based on signal quality. For subjects with high-quality signals, it maintains a harmonious balance between reconstruction, classification, and regularization. For subjects with more challenging signals, it strategically prioritizes representation learning (REC loss) over immediate classification (CLA loss). This intelligent trade-off is visually confirmed by the qualitative analysis of the reconstructions (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), which shows that the model consistently generates spatially coherent and physiologically plausible connectivity maps. This behavior supports the notion that a well-regularized and accurately reconstructed representation is a prerequisite for effective classification, especially in noisy conditions.

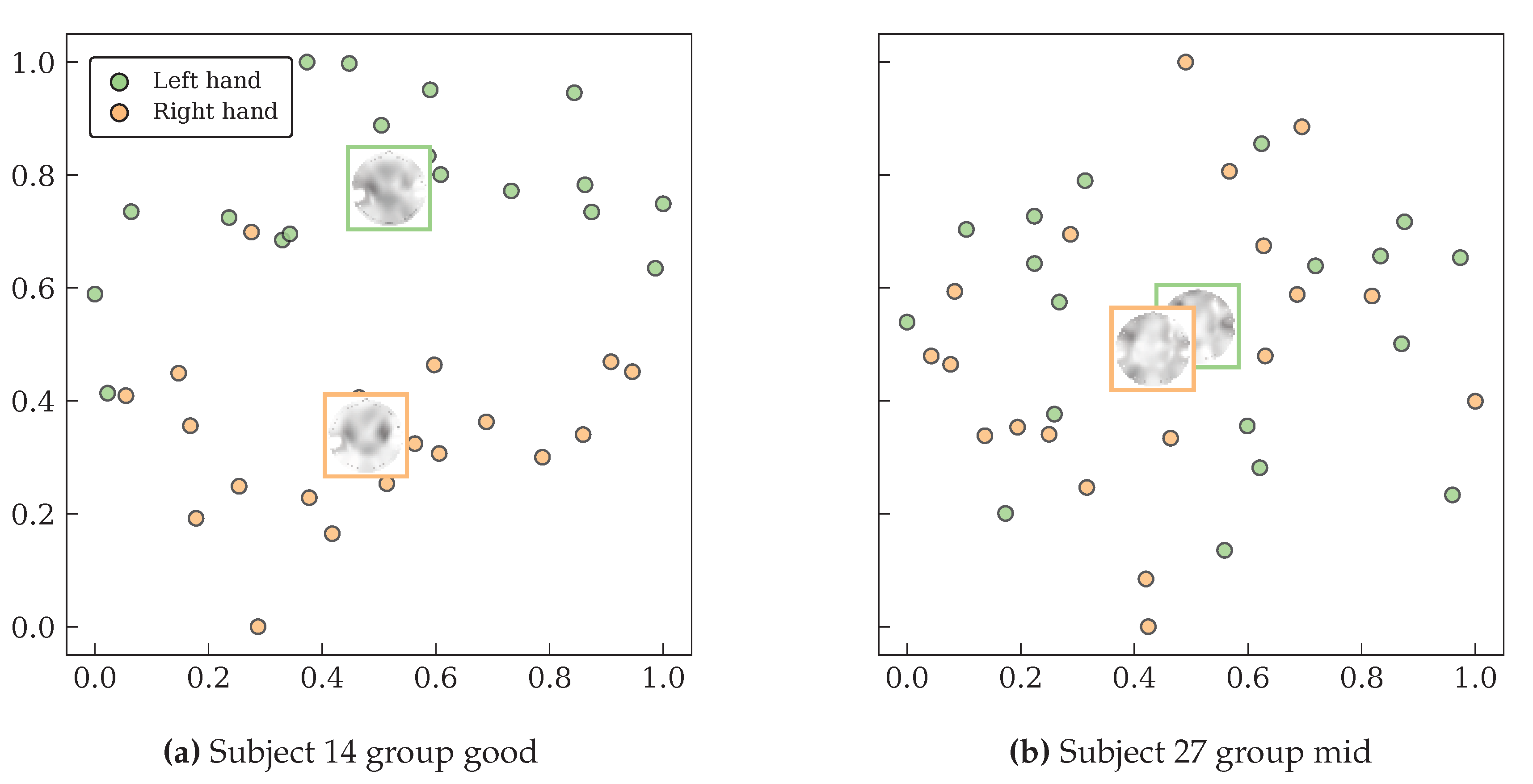

The ultimate outcome of this adaptive process is the creation of a well-structured and discriminative latent space. The t-SNE visualizations (

Figure 10) provide direct evidence that the encoder successfully learns to disentangle the features of different MI classes, creating clearly separated clusters for high-performing subjects and maintaining reasonable separation even for mid-performing subjects. This demonstrates that the variational formulation and structured latent regularization are the primary drivers of the model’s superior performance, allowing it to move beyond the limitations of conventional architectures that often struggle with noisy or overlapping feature distributions.

Finally, the statistical analysis (

Figure 4,

Table 3) confirms the superiority of EEG-GCIRNet, which achieved the lowest average ranking (

) and the most significant

p-value (

). This indicates that the observed performance gains are not random fluctuations but a consistent outcome of the model’s design. By learning robust latent structures directly from connectivity-based topographic representations, EEG-GCIRNet emerges as a reliable, interpretable, and computationally efficient framework for motor imagery decoding. It effectively balances accuracy, generalization, and representational stability, allowing it to adapt to diverse subject profiles and maintain strong performance across varying signal quality conditions while preserving a physiologically consistent representational organization.

6. Concluding Remarks

In this work, we introduced EEG-GCIRNet, a unimodal framework based on a variational autoencoder designed to process topographic representations of functional connectivity for motor imagery classification. Through a comprehensive analysis, we demonstrated that this approach effectively addresses the persistent challenges of low accuracy and high inter-subject variability in EEG-based BCIs. The findings confirm that our proposed method not only sets a new benchmark for performance but also provides a robust and interpretable solution.

The primary contribution of this study is the demonstration of superior classification performance. EEG-GCIRNet achieved the highest average accuracy () and, critically, the lowest inter-subject variability () among all evaluated state-of-the-art and baseline models. The statistical analysis confirmed that this performance advantage is significant (), establishing EEG-GCIRNet as a highly reliable and consistent framework for MI decoding.

Perhaps the most significant finding is the model’s robustness in handling challenging EEG signals. By providing substantial accuracy gains for both “Mid” () and “Bad” () performance groups, and by completely eliminating the “Bad” group, EEG-GCIRNet proved its ability to mitigate the effects of BCI illiteracy. This corrective capability suggests that the framework can make BCI technology accessible and effective for a much broader range of users, a crucial step toward the development of inclusive neurotechnology.

This robust performance is driven by the model’s adaptive, multi-objective learning strategy. The analysis of the loss component weights revealed that EEG-GCIRNet dynamically prioritizes its learning objectives, balancing reconstruction, classification, and regularization, based on the quality of the input signals. This intelligent mechanism enables the creation of a well-structured and disentangled latent space, as confirmed by reconstruction and t-SNE analyses. This demonstrates that the model’s success is not a "black box" phenomenon but a direct result of its principled variational design, which effectively learns physiologically meaningful representations even from noisy data.

Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the model was trained and evaluated exclusively on a single motor imagery dataset. This constrains the generalizability of our findings to other BCI paradigms (e.g., P300, SSVEP) or datasets with different characteristics. Second, although the model demonstrated adaptive behavior, the hyperparameters weighting the loss components were static. This fixed weighting may not be optimal for all subjects, and no strategies for dynamic, performance-based adaptation were explored. Finally, our interpretability analysis, while insightful, remains indirect. The analysis of reconstructions and latent space provides a high-level understanding but does not offer the granular, feature-level attribution that techniques like attention-based visualization can provide.

The findings and limitations of this study open several avenues for future research. To address generalizability, the next logical step is to evaluate the EEG-GCIRNet framework on more diverse and larger-scale datasets, including different BCI paradigms and clinical populations. Furthermore, we propose exploring extensions of the model that incorporate dynamic weighting mechanisms for the loss components, which could allow for even greater subject-specific adaptation. We also plan to investigate hybrid architectures, particularly those based on Transformers, to enhance the fusion of raw temporal EEG signals with our connectivity-derived topographic maps, potentially creating a more powerful, end-to-end model. Finally, integrating complementary interpretability techniques, such as feature attribution or attention-based visualization methods, will be crucial for providing a more precise understanding of the model’s decision-making process at the clinical level.