Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Channel Dropout Regularization: Introducing structural noise to simulate montage variability and improve generalization.

- LayerCAM Integration: Enhancing model transparency by visualizing discriminative EEG regions per MI class.

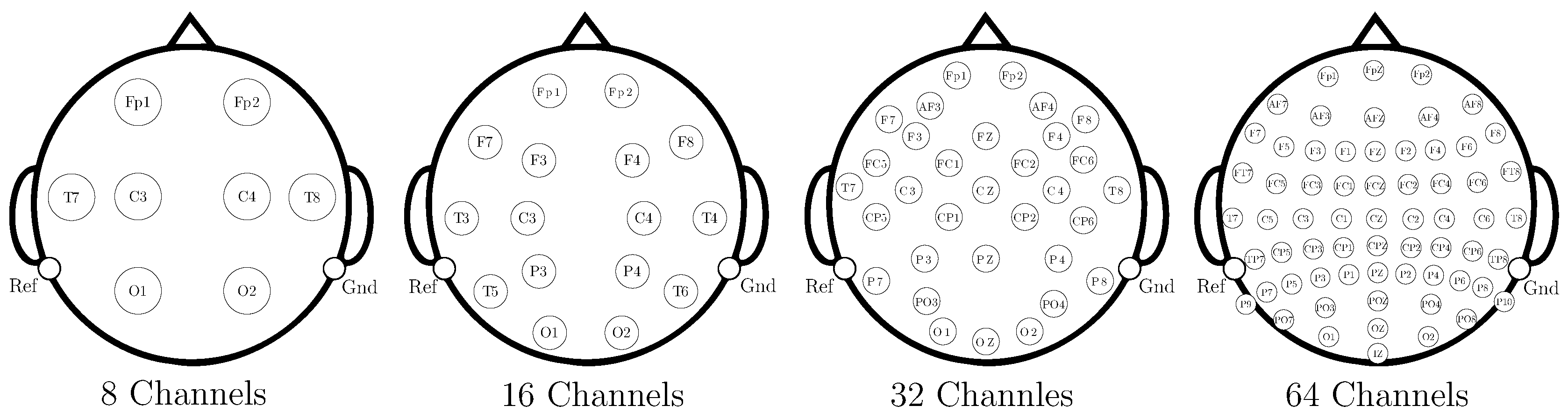

- Evaluation Across Varying Montages: Testing 8, 16, 32, and 64-channel configurations to assess robustness and practical applicability.

- Performance Analysis by Subject Grouping: Stratifying subjects into high- and low-performing cohorts to investigate model behavior across heterogeneous EEG data.

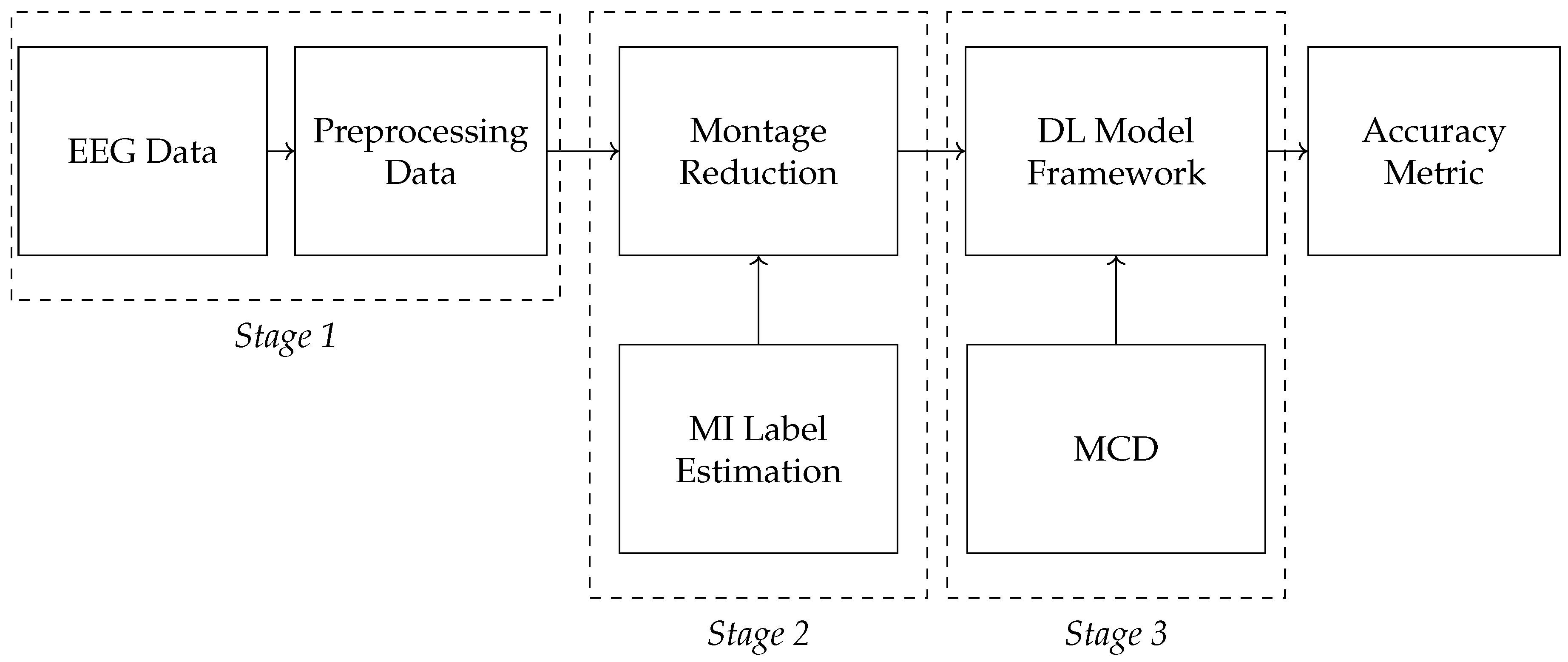

2. Materials and Methods

Baseline Feature Extraction of Spatiotemporal Characteristics

Deep Learning Frameworks for Feature Extraction of MI Responses

- ∗

- ∗

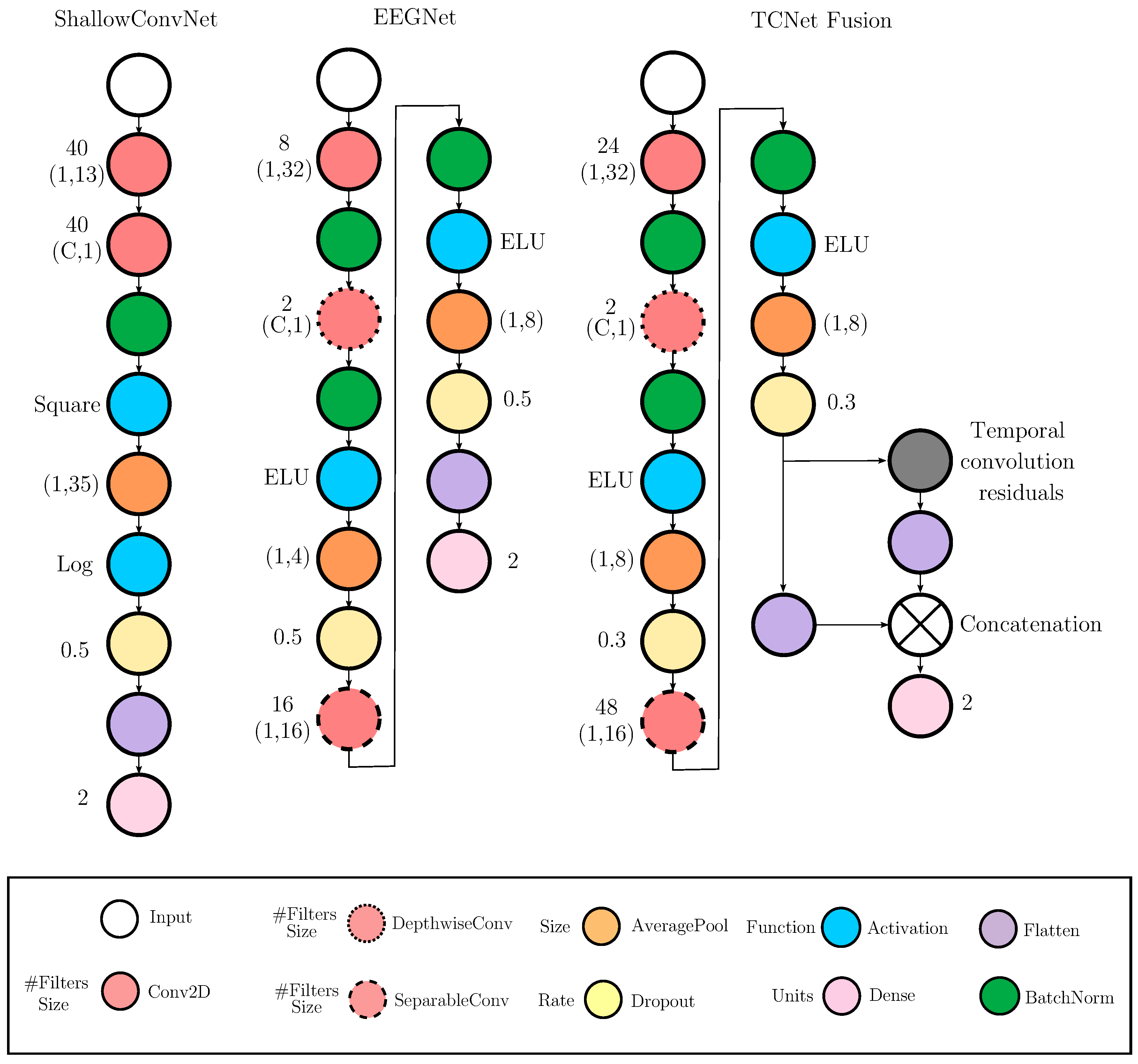

- EEGNet Framework. In this architecture, feature extraction is carried out through a sequence of convolutional blocks , structured as [25]:where and denote the number of temporal and separable filters, respectively; and are the kernel sizes for the temporal and depthwise convolutions; and is the number of spatial filters. Each block is followed by batch normalization and non-linear activation.

- ∗

- TCNet (Temporal Convolutional Network) Framework. TCNet extends the prior architectures by integrating temporal convolutional modules with residual connections [26,27]. The model combines filter bank design with deep temporal processing through the sequential application of blocks , as follows:where and are the kernel sizes for the initial and filter bank convolutions, is the number of feature maps, L is the number of residual blocks, , and denotes a temporal convolutional block with dilated convolutions. The dilation factor increases with l, enabling exponential growth in the receptive field while preserving temporal resolution.

Monte Carlo Dropout with CAM Integration for MI Classification

3. Experimental Set-Up

Evaluating Framework

- ∗

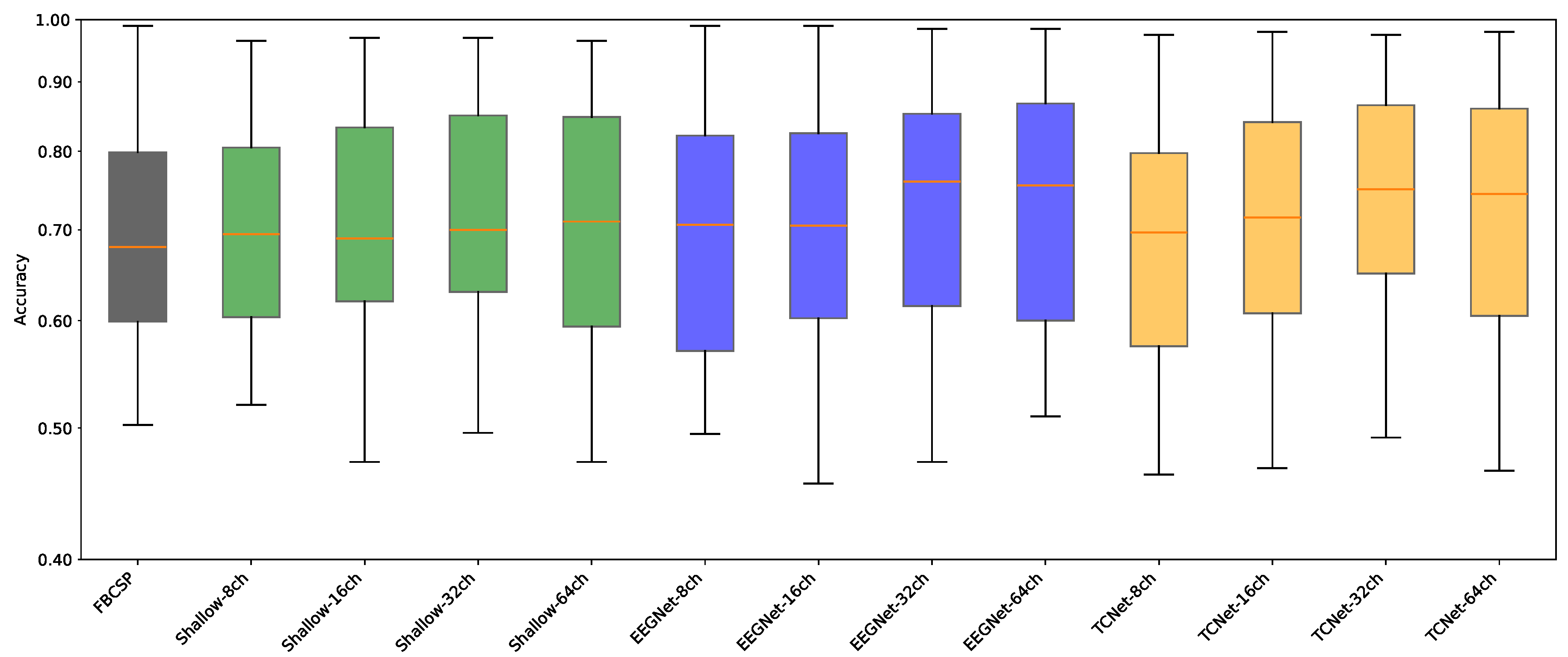

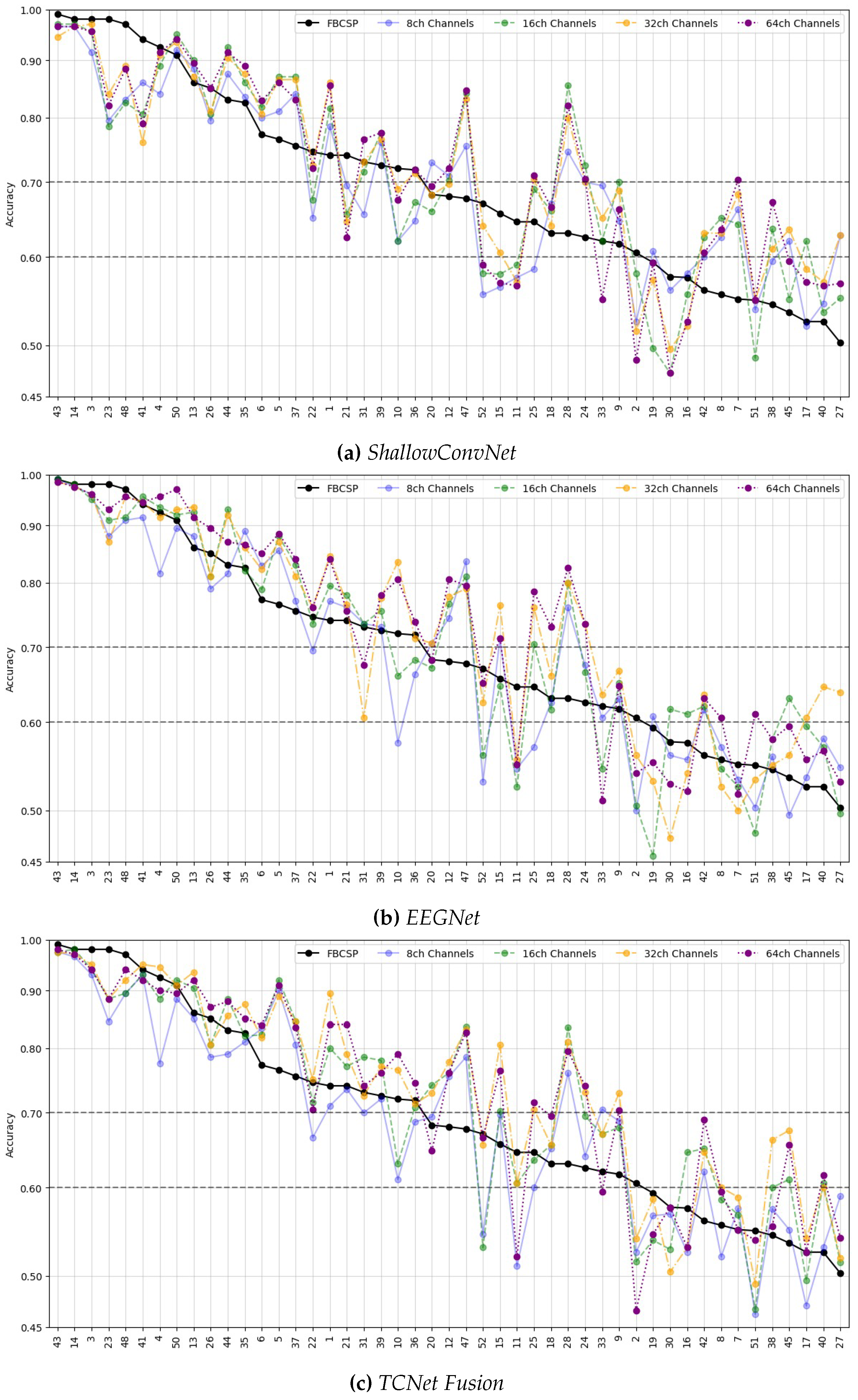

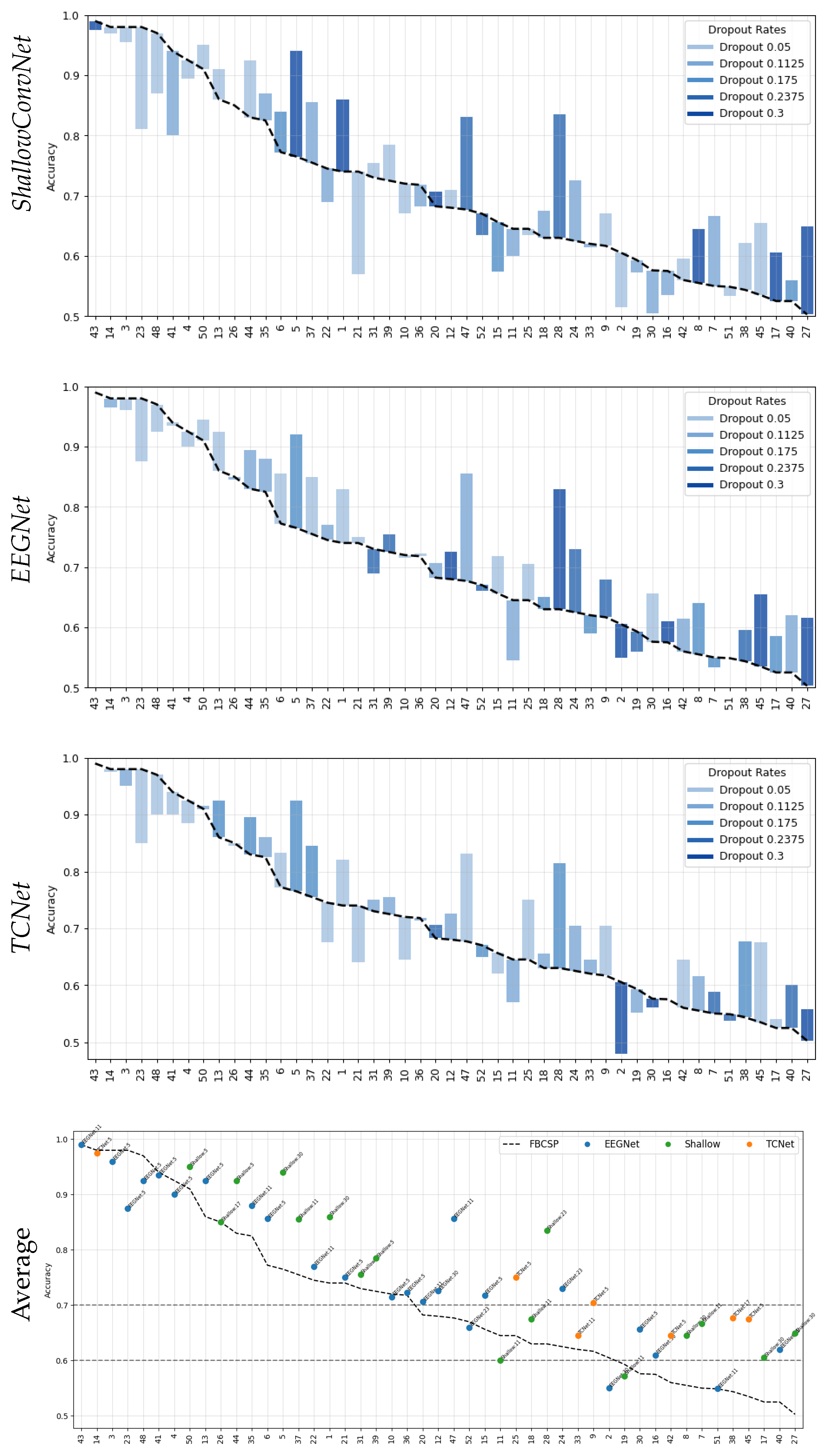

- Data Preprocessing and Montage Reduction. We evaluate the impact of EEG montage size on model generalizability, hypothesizing that excessive channels promote overfitting on spatially correlated artifacts rather than task-specific MI neural dynamics. Montage sizes are tested separately for the best- and worst-performing subjects. Subjects are stratified into high (best)- and low (worst)-performance cohorts based on evaluated trial accuracy ( or). This serves as a conventional reference for evaluating the benefits of DL-based frameworks in ranking subjects based on their trial-level classification accuracy.

- ∗

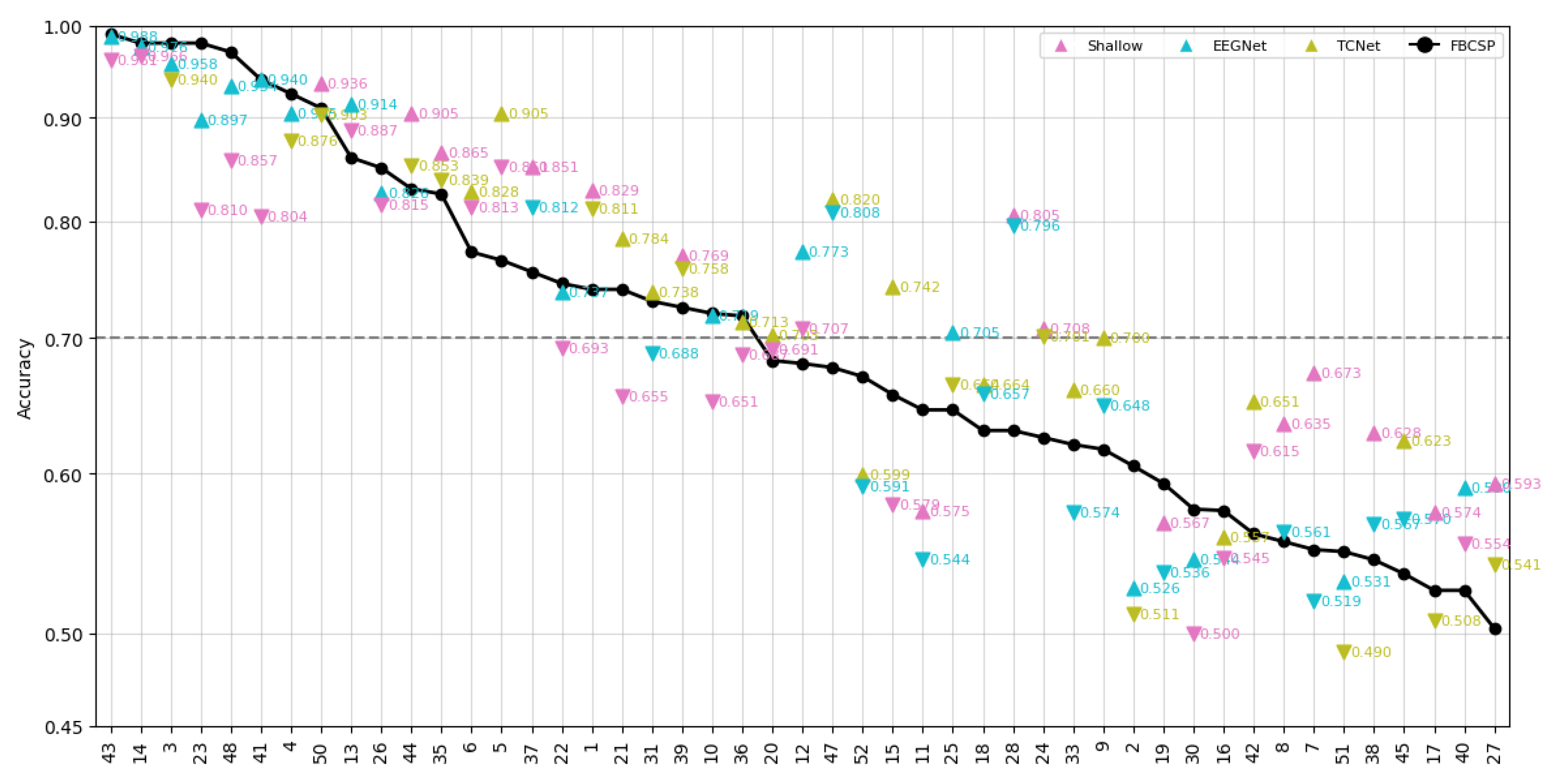

- Subject Grouping Based on the Classification Accuracy of MI Responses. We evaluate three Neural network models for EEG-based classification, EEGNet and ShallowConvNet, for their real-time applicability, alongside the advanced TCNet Fusion architecture for enhanced performance. As stated above, we use FBCSP as a classical baseline for extracting subject-specific spatio-spectral features. This provides a conventional reference to assess the benefits of deep learning-based approaches.

- ∗

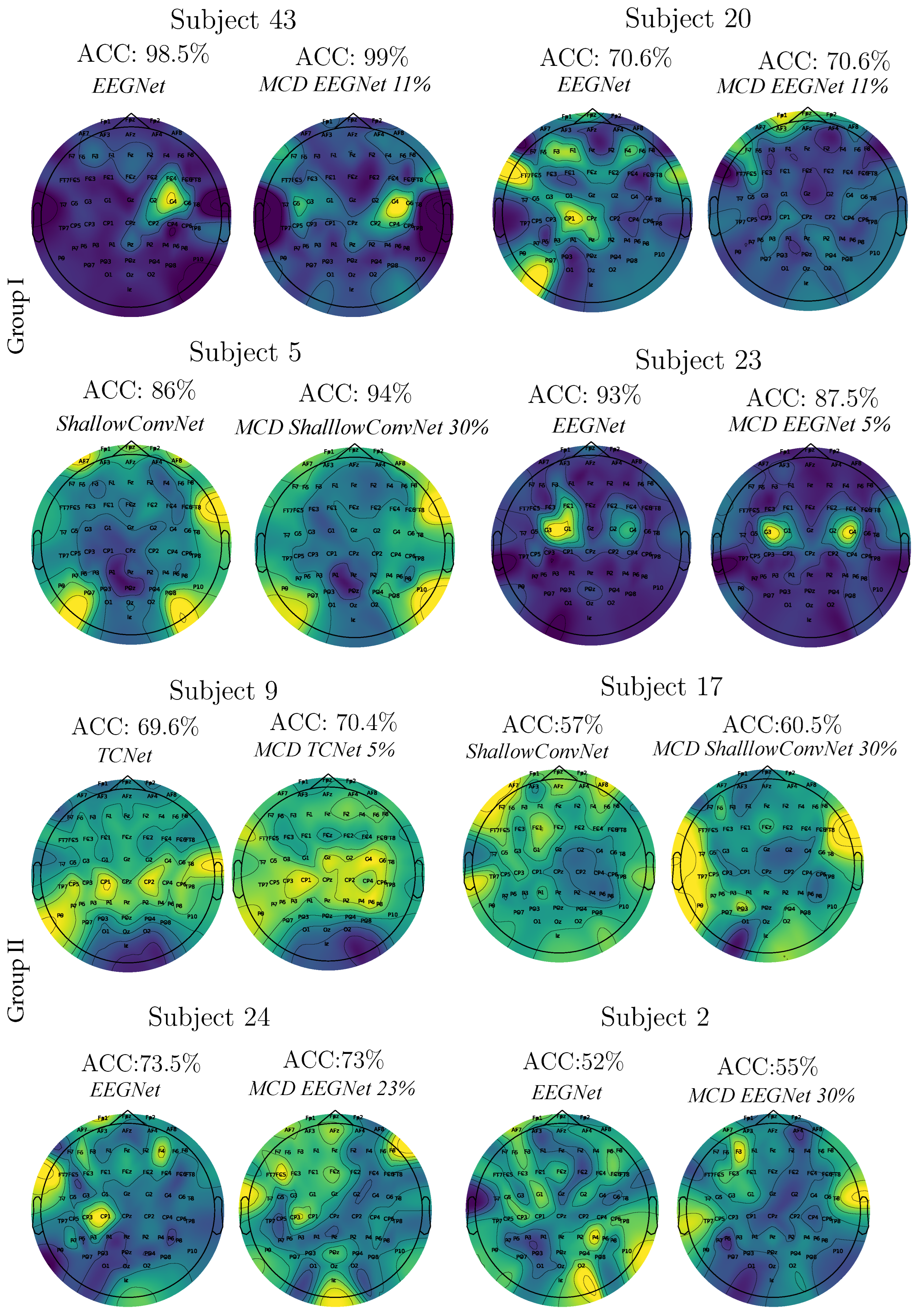

- Spatio-temporal uncertainty estimation. MCD is applied to assess each model’s ability to learn robust, channel-independent features, thereby reducing overfitting and improving generalization. Furthermore, MCD is combined with CAMs to estimate spatio-temporal uncertainty and enhance model interpretability. Specifically, the variance computed across CAMs is overlaid onto the original CAM representation, highlighting regions where the model exhibits reduced certainty in its interpretation of MI responses.

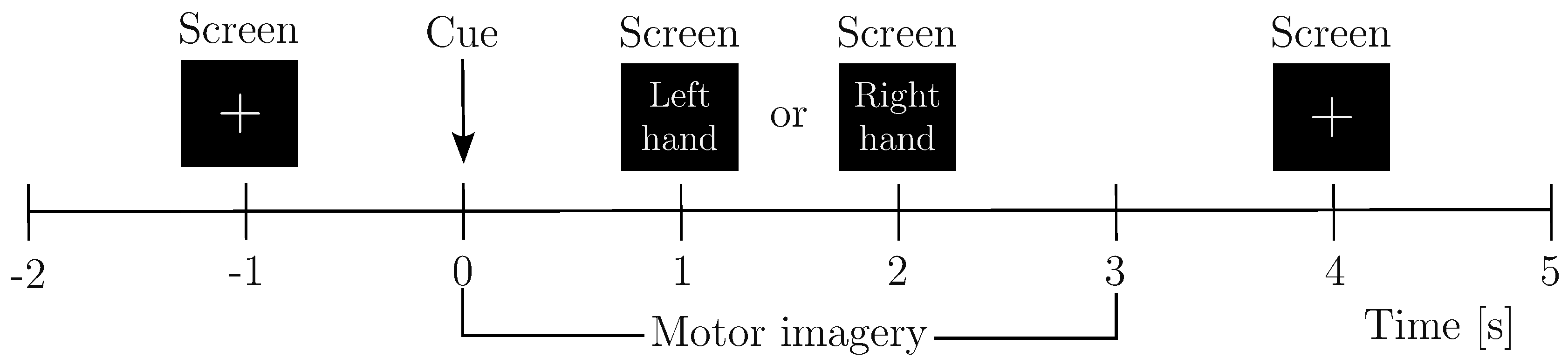

EEG Preprocessing and Reduction of EEG-Channel Montage Set-Up

Evaluated Deep Learning Models for EEG-based Classification

- ∗

- ShallowConvNet [36]: A low-complexity architecture that emphasizes early-stage feature extraction through sequential convolutional layers, square and logarithmic nonlinearities, and pooling operations. It effectively emulates the principles of the classical FBCSP pipeline within an end-to-end trainable deep learning framework, offering robust performance in MI classification tasks.

- ∗

- EEGNet [25]: A compact, parameter-efficient model that utilizes depthwise and separable convolutions to disentangle spatial and temporal features. Designed for cross-subject generalization and computational efficiency, EEGNet maintains competitive accuracy across a wide range of EEG-based paradigms.

- ∗

- TCNet Fusion [37]: A high-capacity architecture that incorporates residual connections, dilated convolutions, and convolutions to construct a multi-pathway fusion network. Its hierarchical design captures long-range temporal dependencies and enhances feature integration across time, improving classification performance in complex MI scenarios.

Subject Grouping Based on the Classification Accuracy of MI Responses

- ∗

- Group I: Well-performing subjects with binary classification accuracy above 70%, as proposed in [39].

- ∗

- Group II: Poor-performing subjects with accuracy below this threshold.

Enhanced CAM-Based Spatial Interpretability

4. Results and Discussion

Tuning of validated DL models

Accuracy of MI Responses: Results of Subject Grouping

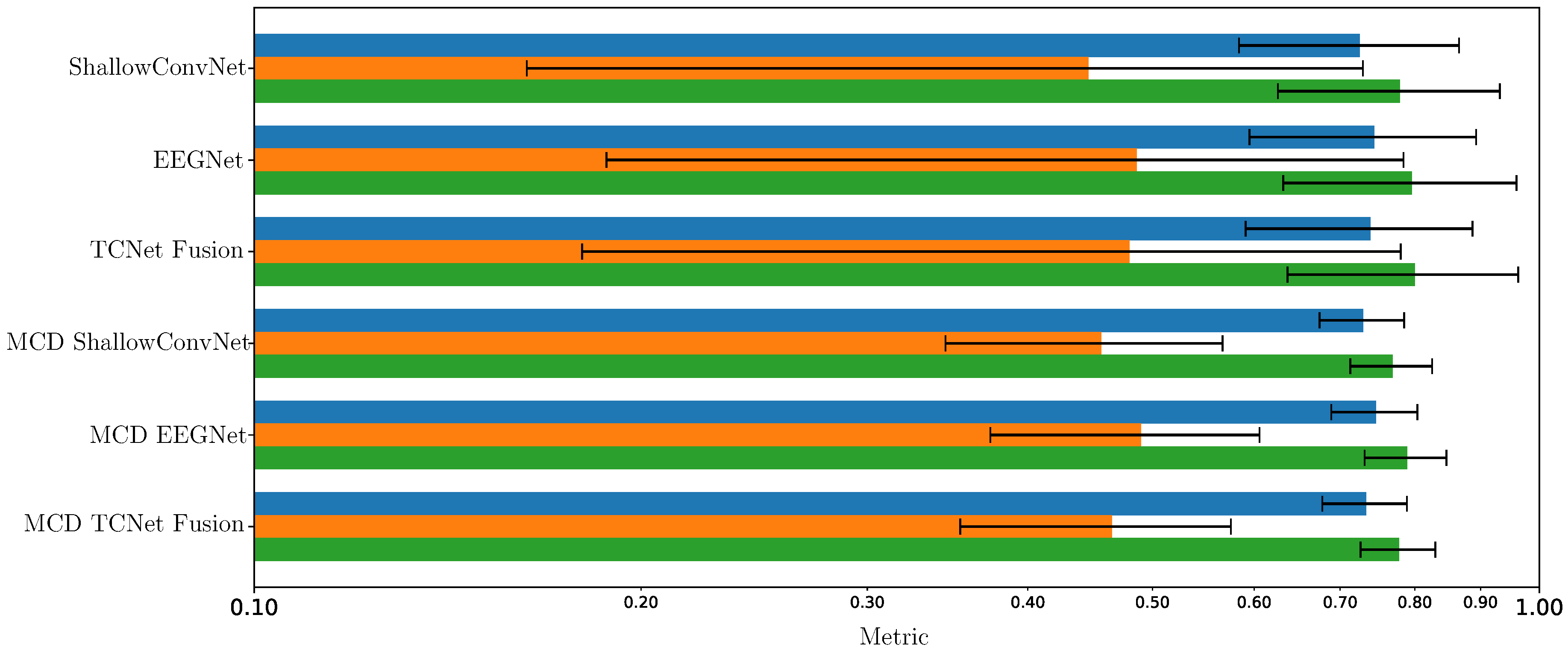

Enhanced Consistency of DL Model Performance Using Monte Carlo Dropout

CAM-Based Interpretability of Spatial Patterns

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 |

References

- Pichiorri, F.; Morone, G.; Patanè, F.; Toppi, J.; Molinari, M.; Astolfi, L.; Cincotti, F. Brain-computer interface boosts motor imagery practice during stroke recovery. Annals of Neurology 2020, 87, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolas-Alonso, L.F.; Gomez-Gil, J. Brain Computer Interfaces, a Review. Sensors 2021, 12, 1211–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlQaysi, Z.; et al. Challenges in EEG-Based Classification. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2021, 356, 109123. [Google Scholar]

- George, S.; et al. EEG Signal Variability in BCI Applications. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2021, 29, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Altaheri, H.; et al. Optimizing DL Architectures for EEG. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 8901–8915. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; et al. Overfitting in EEG DL Models. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 2021, 15, 678901. [Google Scholar]

- Milanes-Hermosilla, J.; et al. Channel Configurations in Portable EEG. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 82, 104567. [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli, F.; et al. Data Quality in EEG Systems. Journal of Neural Engineering 2022, 19, 034001. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; et al. Interpretability Challenges in DL. Nature Machine Intelligence 2021, 3, 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Jalali, A.; et al. Advances in Explainable BCI. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2024, 71, 789–800. [Google Scholar]

- Milanes-Hermosilla, J.; et al. Uncertainty in BCI with MCD. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2021, 68, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; et al. Overfitting in EEG DL. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022, 33, 2345–2356. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, E.; et al. Dropout Tuning in DL Models. Neural Networks 2023, 158, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Keutayeva, A.; et al. LayerCAM for EEG Interpretability. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 10987–11001. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, M.; et al. Dropout in Sparse EEG Montages. Journal of Medical Systems 2023, 47, 4567. [Google Scholar]

- Collazos-Huertas, D.; et al. EEG Non-Stationarity in MI. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics 2022, 16, 890123. [Google Scholar]

- Collazos-Huertas, D.; et al. CSP Limitations in EEG. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2021, 29, 1456–1467. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Velasco, M.; et al. Explainable AI in EEG. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2024, 150, 104567. [Google Scholar]

- Liman, T.; et al. Hybrid Regularization in EEG. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 67890–67901. [Google Scholar]

- Ramoser, H.; Müller-Gerking, J.; Pfurtscheller, G. Optimal spatial filtering of single trial EEG during imagined hand movement. IEEE Transactions on Rehabilitation Engineering 2000, 8, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankertz, B.; Tomioka, R.; Lemm, S.; Kawanabe, M.; Müller, K.R. Optimizing spatial filters for robust EEG single-trial analysis. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2008, 25, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, K.K.; Chin, Z.Y.; Zhang, H.; Guan, C. Filter bank common spatial pattern (FBCSP) in brain–computer interface. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE; 2012; pp. 2390–2397. [Google Scholar]

- Saibene, F.; Marini, L.; Valenza, G. Benchmarking Deep Learning Architectures for EEG-Based Motor Imagery Classification: A Comparative Study. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2024, 32, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schirrmeister, R.T.; Springenberg, J.T.; Fiederer, L.D.J.; Glasstetter, M.; Eggensperger, K.; Tangermann, M.; Hutter, F.; Burgard, W.; Ball, T. Deep learning with convolutional neural networks for EEG decoding and visualization. Human Brain Mapping 2017, 38, 5391–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawhern, V.; Solon, A.; Waytowich, N.; Gordon, S.; Hung, H.; Lance, B. EEGNet: A Compact Convolutional Neural Network for EEG-based Brain-Computer Interfaces. Journal of Neural Engineering 2018, 15, 056013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, D.; Calvo, R.A. Optimal fusion of EEG motor imagery and speech using deep learning with dilated convolutions. Journal of Neural Engineering 2019, 16, 066030. [Google Scholar]

- Proverbio, A.M.; Pischedda, F. Measuring Brain Potentials of Imagination Linked to Physiological Needs and Motivational States. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2023, 17, 1146789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leingang, O.; Riedl, S.; Mai, J.; et al. Estimating Patient-Level Uncertainty in Seizure Detection Using Group-Specific Out-of-Distribution Detection Technique. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 19545. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Luo, J.; Chu, S.; Cannard, C.; Hoffmann, S.; Miyakoshi, M. ICA’s bug: How ghost ICs emerge from effective rank deficiency caused by EEG electrode interpolation and incorrect re-referencing. Frontiers in Signal Processing 2023, 3, 1064138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Qin, C.; Fang, J. Motor-imagery classification model for brain-computer interface: a sparse group filter bank representation model. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vempati, R.; Sharma, L. EEG rhythm based emotion recognition using multivariate decomposition and ensemble machine learning classifier. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2023, 393, 109879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, F.; Sobahi, N.; Siuly, S.; Sengur, A. Exploring deep learning features for automatic classification of human emotion using EEG rhythms. IEEE Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 14923–14930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Murillo, D.G.; Álvarez-Meza, A.M.; Castellanos-Dominguez, C.G. Kcs-fcnet: Kernel cross-spectral functional connectivity network for eeg-based motor imagery classification. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saibene, A.; Ghaemi, H.; Dagdevir, E. Deep learning in motor imagery EEG signal decoding: A Systematic Review. Neurocomputing 2024, 610, 128577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, S.W. Rethinking CNN architecture for enhancing decoding performance of motor imagery-based EEG signals. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 96984–96996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musallam, Y.K.; AlFassam, N.I.; Muhammad, G.; Amin, S.U.; Alsulaiman, M.; Abdul, W.; Altaheri, H.; Bencherif, M.A.; Algabri, M. Electroencephalography-based motor imagery classification using temporal convolutional network fusion. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2021, 69, 102826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, B.J.; Zhang, S.; Schalk, G.; Brunner, P.; Müller-Putz, G.; Guan, C.; He, B. Non-invasive brain-computer interfaces: state of the art and trends. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collazos-Huertas, D.F.; Velasquez-Martinez, L.F.; Perez-Nastar, H.D.; Alvarez-Meza, A.M.; Castellanos-Dominguez, G. Deep and Wide Transfer Learning with Kernel Matching for Pooling Data from Electroencephalography and Psychological Questionnaires. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.T.; Zhang, C.B.; Hou, Q.; Cheng, M.M.; Wei, Y. LayerCAM: Exploring hierarchical class activation maps for localization. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2021, 30, 5875–5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Patel, S.; Kim, H. Uncertainty Quantification in EEG Classification Using Monte Carlo Dropout. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2024, 71, 123456. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Yuan, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, R.; Jiang, T. Towards best practice of interpreting deep learning models for EEG-based brain computer interfaces. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 2023, 17, 1232925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nzakuna, K.R.; Agbangla, N.F.; Tchoffo, D.; Dossou-Gbétchi, W.M.; Amey, K. Monte Carlo-based Strategy for Assessing the Impact of EEG Data Uncertainty on Confidence in Convolutional Neural Network Classification. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2025, 81, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wu, D.; Lin, C.T. Transfer learning for brain–computer interfaces: A Euclidean space data alignment approach. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2020, 67, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, Q.; Onishi, A.; Cichocki, A. Multi-kernel extreme learning machine for EEG classification in brain–computer interface. Expert Systems with Applications 2020, 149, 113285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liman, M.D.; Osanga, S.; Alu, E.S.; Zakariya, S. Regularization Effects in Deep Learning Architecture. Journal of the Nigerian Society of Physical Sciences 2024, 6, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiahao, H.U.; Ur Rahman, M.M.; Al-Naffouri, T.; Laleg-Kirati, T.M. Uncertainty Estimation and Model Calibration in EEG Signal Classification for Epileptic Seizures Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–4.

- Cho, H.; Ahn, M.; Ahn, S.; Kwon, M.; Jun, Sung, C. Supporting data for "EEG datasets for motor imagery brain computer interface", 2017. [CrossRef]

| Model | 8 Channels | 16 Channels | 32 Channels | 64 Channels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ShallowConvNet | ||||

| EEGNet | ||||

| TCNet Fusion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).