1. Introduction

Quantum coherence in biological systems has traditionally been viewed as fragile, limited to low-temperature or photochemical contexts. Yet a growing body of evidence, from photosynthetic complexes, avian magnetoreception, and ultrafast spectroscopy of aromatic amino acids, suggests that living matter may sustain transient quantum correlations under physiological conditions. Within the brain, the microtubule cytoskeleton has long been proposed as a privileged site for such phenomena, most prominently in the Penrose-Hameroff

Orchestrated Objective Reduction (Orch OR) hypothesis [

1,

2,

3], which attributes the emergence of conscious episodes to orchestrated quantum states in tubulin followed by objective gravitational collapse.

Two recent developments renew this discussion from complementary directions. First, Nishiyama and collaborators [

4] formulated a quantum electrodynamical model in which tryptophan residues embedded in the microtubule wall act as two-level systems coupled quadratically to electromagnetic modes. When the transition and cavity frequencies satisfy

, the system undergoes

parametric resonance: background fluctuations are either amplified or suppressed depending on the initial qubit configuration. Stacks of microtubular layers behave as binary optical filters whose transmissivity shifts under anesthesia, suggesting a quantum-optical link between cytoskeletal dynamics and conscious state modulation.

Second, Reference [

5] showed that microtubule geometry follows arithmetic constraints identical to those governing elliptic curves derived from finite braid-group quotients from the SU(2)

3 Fibonacci anyon model. These elliptic curves have symmetries controlled by an imaginary quadratic field also called in this context an Heegner field. The relevant curve

admits the Gaussian field

as its Heegner field, producing a rectangular lattice that mirrors the protofilament architecture observed by cryo-electron microscopy.

This curve is selected because its conductor corresponds to a minimal composite integer that yields a Heegner field with class number one, ensuring unique factorization and minimal energy dispersion in the lattice packing. Among the possible elliptic curves derived from The Fibonacci anyon model, is the simplest whose Heegner field produces a rectangular lattice matching the protofilament architecture observed in cryo-electron microscopy. Other curves, such as (associated with ), yield hexagonal symmetries more suited to B-DNA. The choice of is thus not arbitrary but reflects an evolutionary optimization for orthogonal field polarization and dipolar oscillations.

This paper unifies these perspectives. The arithmetic geometry of defines the static symmetry and boundary conditions for dipolar oscillations, while the Nishiyama resonance model provides the dynamic process by which environmental noise can amplify coherence within that structure. The result is a mathematically and physically consistent mechanism of noise-assisted quantum orchestration that bridges number theory, quantum optics, and neurobiology. We outline its implications for Orch OR, propose spectroscopic and geometric tests, and discuss how arithmetic geometry may underlie a hierarchy of quantum-biological symmetries.

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the arithmetic geometry of microtubules, deriving elliptic curves from a finite anyon braid group and identifying the Gaussian field

as the relevant Heegner field.

Section 3 develops the physical realization of this geometry, showing how the rectangular

lattice constrains dipolar alignment, field confinement, and quantum symmetry.

Section 4 formulates the quantum–oscillatory model of tryptophan residues and reviews the Nishiyama

et al. parametric–resonance Hamiltonian.

Section 5 explores noise–assisted coherence and binary optical behavior in multilayer microtubules, including anesthetic detuning and energy scaling.

Section 6 unifies the stochastic and arithmetic pictures, deriving arithmetic–resonant coupling laws governed by

and Gaussian norms

.

Section 7 connects these results to the Penrose–Hameroff

Orch OR framework, clarifying the respective roles of stochastic coherence and gravitational self–selection.

Section 8 presents experimental and theoretical predictions, from spectroscopic tests to neurophysiological implications.

Section 9 provides a broader discussion and outlook, and

Section 10 concludes. The Appendix extends the analysis by linking the cyclotomic approach to time perception with an adelic–Hecke formalism that merges the Bost–Connes system and the arithmetic–elliptic resonance mechanism, revealing a deep correspondence between modular tensor categories, adeles, and biological coherence.

Interpretation layers.

To avoid conflating conceptually distinct elements, the structure of the argument is divided into three levels: (i) mathematically rigorous results concerning elliptic curves, Heegner fields, and

L–functions; (ii) heuristic but physically motivated modeling assumptions such as cavity approximations and parametric resonance of tryptophans; (iii) empirical correspondences between biological geometric ratios and values of

.

Section 2,

Section 4, and

Section 6 make these distinctions explicit.

2. Arithmetic Geometry of Microtubules

Microtubules are hollow cylindrical polymers of

–

tubulin dimers arranged in a helical sheet of typically thirteen protofilaments. Their outer and inner diameters,

nm and

–

nm, yield a robust structural ratio

remarkably constant across species and environmental conditions. This ratio does not follow from simple mechanical or chemical constraints, suggesting that microtubules realize an underlying mathematical optimum. In Reference [

5], it is proposed that this ratio and similar biological proportions correspond to derivatives of modular elliptic

L-functions at unity,

, linking biological form to arithmetic geometry.

2.1. Elliptic Curves from Finite Anyon Braid Groups

The starting point is the observation that the SU(2)

3 Fibonacci anyon model yields finite braid-group quotients whose

character varieties contain elliptic components [

5]. The fundamental fusion rule

leads to the group sequence

where

,

, and

denote the binary tetrahedral, octahedral, and icosahedral groups. Each such quotient defines a family of modular elliptic curves

whose conductors

correspond to small composite integers (e.g.

for the case of 2T which corresponds to the structure of microtubules). The analytic derivative

of the

L-function of

E measures the height of the Heegner point associated with the imaginary quadratic field

K.

For microtubules, the curve

emerges as the relevant arithmetic object. It has analytic rank 1 and a non-vanishing derivative

Through the Gross–Zagier relation this curve is linked to the Heegner field

, corresponding to a rectangular lattice in the complex plane.

2.2. Geometric Interpretation of the Heegner Field

The ring of integers of the Gaussian field forms a square lattice generated by the basis vectors with unit group . In two dimensions this lattice provides the densest rectangular packing consistent with orthogonal symmetry. Its arithmetic and geometric features are directly mirrored in the microtubule architecture: protofilaments form nearly straight columns connected laterally at right angles, generating a sheet that wraps into a cylinder with quasi-rectangular contacts between dimers. The phase periodicity of the Gaussian units parallels the fourfold symmetry of lateral binding sites revealed by cryo-electron microscopy.

Protofilament-number constraint.

The standard microtubule contains

protofilaments, but this number does not emerge as a strict arithmetic invariant of the rectangular

lattice. In the present model, the lowest resonant mode

scales approximately as

only when the azimuthal component of the dipolar coupling dominates over the longitudinal one. This condition corresponds physically to a regime where transverse field interactions along the microtubule circumference set the effective boundary condition for the collective oscillation. When the longitudinal (axial) coupling becomes comparable, the scaling deviates from

, and alternative protofilament counts (

) can appear under specific polymerization conditions. Hence, the canonical value

is an emergent geometric optimum rather than a fundamental constraint, whereas the diameter ratio

derived in Equation (

1) remains a first-principles invariant of the rectangular packing. Future work may investigate whether

corresponds to a minimum in the effective free energy when both longitudinal and azimuthal couplings are included, analogous to how fullerenes select specific vertex counts through topological optimization.

Consequently, the Heegner field determines not only the elliptic curve’s arithmetic but also the geometric mode structure of the microtubule wall. Transverse electric and magnetic field components can resonate along the orthogonal lattice vectors of , creating a natural cavity for standing electromagnetic or excitonic waves.

2.3. Quantitative Correspondence Between Arithmetic and Biology

The correspondence extends quantitatively. The normalized derivative

provides an arithmetic constant that is close to the empirical protofilament thinning ratio

Similarly, the elliptic curve

associated with a hyperbolic three-manifold of volume

gives

, within experimental uncertainty of the protofilament thinning ratio

.

Table 1 summarizes representative values. The elliptic curve

has been proposed to be related to the MT outer/inner diameter. The 8% discrepancy with the experimental value may reflect contributions from MAP proteins or hydration shells. For more B-DNA and microtubule ratios see ([

5], Tables 1 and 5).

These coincidences are unlikely to be accidental. They suggest that biological evolution may have selected molecular architectures corresponding to class-number-one fields, those that yield unique factorization and minimal energy dispersion in lattice packing.

A quantitative reason why such correspondences are unlikely to arise from free fitting is the strong arithmetic constraint: only nine imaginary quadratic fields have class number one. The subset of modular elliptic curves with analytic rank 1 and Heegner fields among these nine is extremely small, leaving little freedom for adjustable parameters. The biological ratios highlighted here fall within of the corresponding values of without the introduction of normalization factors, suggesting that the agreement cannot be attributed to flexible parameter tuning.

2.4. Physical Meaning of the Elliptic Structure

An elliptic curve can be viewed as a torus obtained by quotienting the complex plane by a lattice

, with modular parameter

. For the Gaussian field,

and the torus becomes rectangular. In this representation, electronic or dipolar oscillations confined to the microtubule wall experience periodic boundary conditions along both lattice directions. The quantized normal modes correspond to the lattice points of

, and transitions between them may be described by modular transformations

The modular symmetry thus acts as a discrete analog of gauge transformations preserving the underlying topology of the biological structure.

2.5. Summary of the Arithmetic Framework

The microtubule can therefore be understood as a biological realization of the Gaussian elliptic curve , where:

the field encodes rectangular packing and orthogonal field polarization;

the derivative reproduces observed geometric ratios; and

modular transformations describe possible excitonic or electromagnetic mode couplings.

This arithmetic scaffold provides the static, number-theoretic framework upon which dynamic processes, such as tryptophan-based parametric resonance, can act. In the next section we show how the same geometry enables noise-assisted amplification of quantum oscillations, linking arithmetic structure to quantum dynamics.

Table of Symbols

| Symbol |

Meaning |

|

Number of protofilaments (typically 13) |

|

Number of tryptophan oscillators in a microtubule segment |

|

Gaussian norm labeling resonant modes |

| a |

Geometric lattice spacing of the rectangular lattice |

|

Arithmetic renormalized lattice spacing |

|

Tryptophan transition frequency |

|

Cavity (field) frequency |

|

Decoherence/damping rate |

|

Noise power spectral density |

| J |

Dipole–dipole coupling constant |

|

Derivative of elliptic curve L–function at 1 |

3. Rectangular Symmetry and the Gaussian Field

The rectangular lattice generated by the Gaussian integers

offers not only an arithmetic model of microtubular packing but also a physical template for electromagnetic and quantum coherence. In this section we examine how the geometry associated with the field

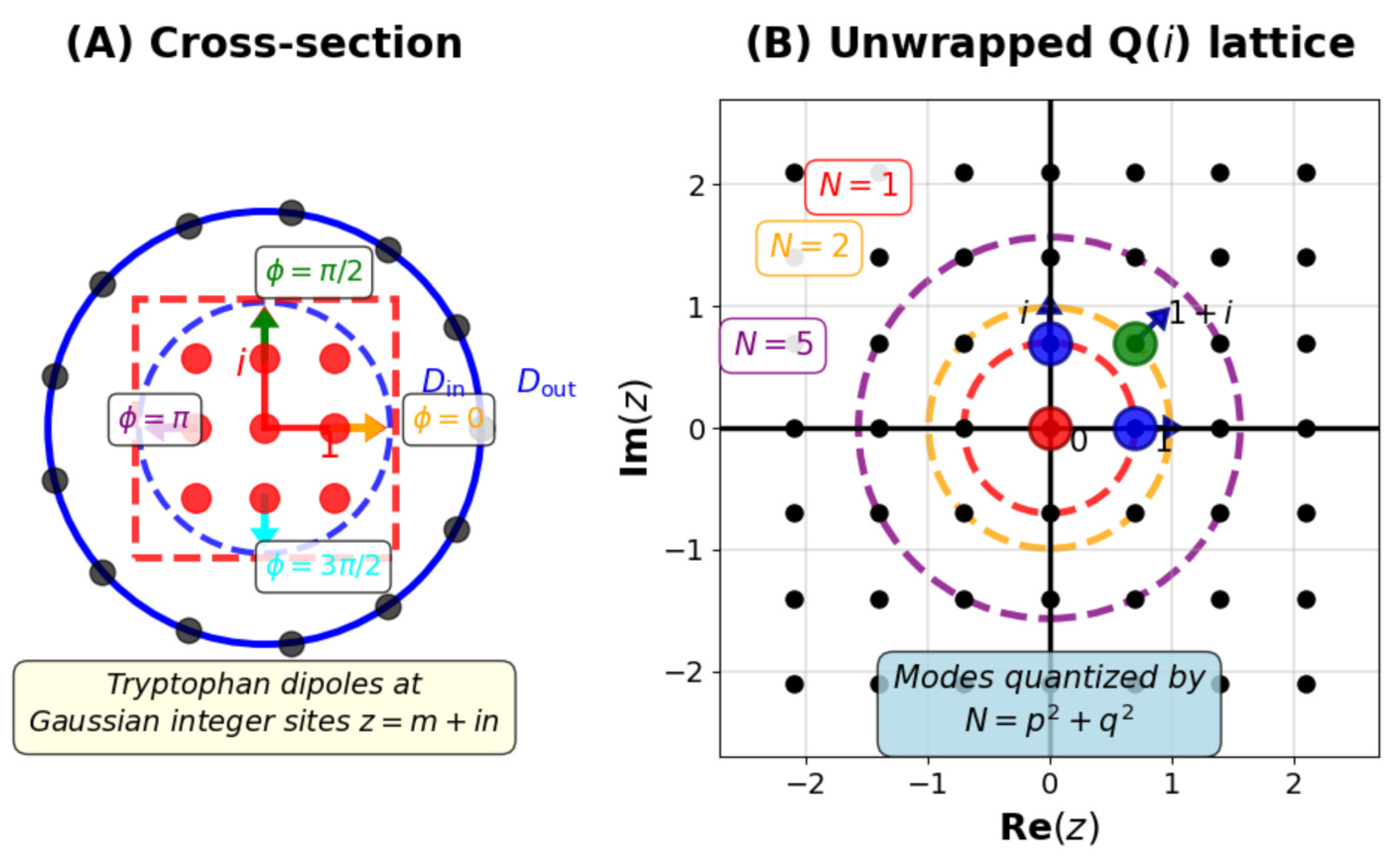

translates into physical symmetries governing dipole alignment, field confinement, and resonance conditions. A schematic of this section is on

Figure 1.

Microtubules exhibit remarkably stable physical parameters across species: cryo-EM measurements consistently report outer and inner diameters of about

and 14–

, corresponding to a wall thickness of

, while optical studies place the effective refractive index of the tubulin lattice in the typical protein range

–

, higher than the surrounding cytosol (

) [

6,

7,

8]. These geometric and dielectric properties set the natural scale for electromagnetic confinement and resonance within the microtubular wall.

3.1. Geometry of Rectangular Packing and Field Modes

A lattice over

supports two orthogonal primitive vectors of equal norm. When wrapped onto a cylindrical surface, these vectors correspond respectively to the longitudinal (protofilament) and azimuthal (circumferential) directions of the microtubule. This geometry ensures that any electromagnetic excitation decomposes into two nearly degenerate, perpendicular modes:

with

and

, where

n is the effective refractive index of the microtubular wall (

).

The confinement of electromagnetic modes within the microtubule wall reduces exposure to cytosolic noise, while the discrete symmetry of the

lattice minimizes destructive interference. This combination of geometric and dynamic factors allows coherence to persist despite thermal agitation, analogous to noise-assisted transport in quantum dots [

9].

The equality of mode frequencies imposed by the symmetry yields a natural condition for parametric resonance: the product of two perpendicular field components oscillating at equal frequency acts as a pump term in the dipole Hamiltonian, matching the Nishiyama condition .

3.2. Electromagnetic Confinement and Cavity Analogy

The microtubule wall, composed of ordered dipolar dimers, forms a dielectric medium of higher index than the surrounding cytosol (). This contrast allows the propagation of guided modes analogous to those in a rectangular waveguide. Experimental Raman, terahertz, and ultrafast optical measurements of purified microtubules report confined vibrational bands in the –30 THz region, together with optical shoulders near 280 nm and 550–600 nm associated with aromatic residues. These data support the plausibility that the rectangular lattice sustains electromagnetic modes within the same frequency range as the tryptophan transitions relevant to parametric resonance.

For a wall thickness of nm, the cutoff wavelength for the lowest-order transverse mode is near 550–nm, coincident with the resonance frequency of tryptophan fluorescence. Hence the Gaussian lattice acts as a natural photonic or excitonic cavity where electromagnetic energy can be stored and exchanged locally.

This confinement obviates the need for coherent light to traverse macroscopic distances through tissue; instead, the relevant modes remain localized within the microtubule and interact with nearby chromophoric residues. The system behaves as a network of nanoscale resonators coupled by near-field interactions.

3.3. Dipole Orientation and Complex Representation

The indole ring of tryptophan carries an electric dipole moment

inclined relative to the protofilament axis. In complex coordinates adapted to the Gaussian lattice,

the dipole’s oscillation can be represented as a rotation in the complex plane of

. The phases

of adjacent residues form a discrete set

corresponding to the units of

. This quantization enforces phase locking between perpendicular oscillations and stabilizes coherent superpositions of orthogonal field components.

The resulting mode structure resembles the polarization states of a square optical cavity but realized in a biological lattice. Transitions between these discrete orientations correspond to modular transformations

which preserve the Gaussian symmetry and ensure isotropic coupling between longitudinal and transverse excitations.

3.4. Rectangular Symmetry as an Optimal Biological Code

Rectangular packing also offers optimal balance between density and flexibility. While hexagonal lattices () maximize packing density, they restrict transverse oscillations to a single angular mode; square lattices permit independent orthogonal vibrations with minimal cross-interference.

While real microtubules exhibit defects and dynamic instability, the rectangular symmetry of the

lattice provides a robust scaffold for coherence. Defects may introduce local perturbations, but the global arithmetic constraints ensure that the resonance conditions

are maintained on average. This robustness is further enhanced by microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs), which can fine-tune the lattice spacing and refractive index to optimize resonance [

10].

This distinction parallels the functional divergence between B-DNA (hexagonal/rotational symmetry) and microtubules (rectangular/oscillatory symmetry). The former encodes information through helical rotation, the latter through standing-wave modulation, a structural dichotomy reflected in their respective Heegner fields.

Such complementarity hints at an evolutionary optimization: biological structures may realize distinct imaginary quadratic fields to encode different categories of information-static genetic storage versus dynamic computational processing.

Influence of microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs).

MAPs such as tau, MAP2, and MAP6 bind selectively along protofilaments, locally stiffening the lattice and slightly modifying its dielectric properties. Cryo-electron microscopy and refractive-index tomography show that MAP-decorated regions can increase the local refractive index by 1–, sufficient to fine-tune resonance conditions. These proteins therefore provide a biologically natural mechanism for adjusting boundary conditions within the arithmetic–geometric framework developed here.

3.5. Topological and Algebraic Consequences

The rectangular symmetry can also be expressed in algebraic-topological terms. The Gaussian integers form an additive group isomorphic to , and the quotient defines a torus of modulus . This torus possesses a modular group acting via Möbius transformations. In the microtubular context, this symmetry governs possible mode couplings and phase shifts, analogous to holonomies of a flat connection on a fiber bundle.

Moreover, the Gaussian field is the simplest field admitting complex conjugation as an automorphism of order two. This duality corresponds to the interchange of the two orthogonal field components , embodying an intrinsic self-duality of the microtubular electromagnetic environment.

3.6. Implications for Quantum Oscillations

The rectangular symmetry thus creates the physical conditions necessary for sustained dipolar oscillations:

Equal-frequency perpendicular modes generate parametric driving at .

Boundary confinement maintains field intensity within the microtubule wall.

Phase quantization at multiples of stabilizes coherent oscillations.

These properties collectively favor parametric resonance among tryptophan oscillators subjected to background fluctuations, providing the bridge from static arithmetic geometry to dynamic quantum behavior.

In the next section we formalize this bridge by deriving the quantum Hamiltonian governing such oscillations and showing how the rectangular symmetry dictates the resonance condition identified by Nishiyama et al.

4. Quantum Oscillations and Parametric Resonance

The rectangular lattice defined by the Gaussian field

provides the physical environment for collective dipolar oscillations of tryptophan residues within the microtubule wall. In this section we formulate a quantum model describing these oscillations, reinterpret the coupling mechanism of Nishiyama

et al. [

4], and derive the conditions under which background electromagnetic fluctuations can amplify coherence through parametric resonance.

4.1. Tryptophan as a Quantum Oscillator

Each tryptophan residue contains an indole ring with delocalized -electrons that generate an electric dipole moment . In the simplest approximation, the lowest optical transition corresponds to a two-level system with energy splitting . We denote by the Pauli operator representing population inversion and by the raising and lowering operators between ground and excited states.

Because of the periodic environment of the

lattice, each tryptophan experiences a quantized local field

composed of orthogonal components

and

of nearly equal frequency

. The dipole–field interaction Hamiltonian is then written as

where a cross term

introduces a modulation at frequency

, enabling parametric excitation when

.

4.2. The Nishiyama Hamiltonian

Nishiyama

et al. described the coupled system of

tryptophan oscillators interacting with a cavity field through a quadratic coupling as

where

a and

are the annihilation and creation operators of the cavity mode,

is the coupling constant (with

the Rabi frequency),

is the transition frequency between the excited state

and the ground state

of each qubit in the two-level approximation, and

is the frequency of the cavity mode (so that

is its energy quantum). The direct interaction between the qubits and the cavity mode is neglected at this stage.

The quadratic term

acts as a

parametric pump: the absorption of two cavity quanta drives a single dipolar excitation. When the resonance condition

is satisfied, the energy transfer between the cavity field and the dipolar oscillators becomes resonant, leading to exponential growth of the oscillation amplitude in the absence of damping.

The observable consequence is the emergence of binary optical transmission in multilayer microtubules: alternating constructive and destructive interference of electromagnetic modes produce spatially modulated transmission patterns. Under anesthesia, a small detuning suppresses the amplification, reproducing the observed shift from nm to nm in the optical response.

4.3. Stochastic Reinterpretation: Background-Field Resonance

We model parametric (curvature) noise as a Hamiltonian perturbation

where

are the oscillator ladder operators,

is a zero-mean stationary

dimensionless process, and

sets the

energy scale of the modulation (

). The symmetrized two-sided power spectral density (PSD) of

is

so that

.

Near parametric resonance (

), rotating-wave and golden-rule analysis give the stochastic gain rate

which has units of

and can be compared directly to the damping rate

. The net growth is therefore

so amplification occurs whenever

.

?

4.4. Collective Amplification in the Lattice

In a network of

interacting tryptophan oscillators located at lattice sites

, near-field coupling adds a term

where

J quantifies coherent exchange between neighbouring dipoles (e.g., tryptophan residues) and depends on the dipole–dipole distance (

–

Å). Diagonalization in reciprocal space yields collective modes with gain reproducing Nishiyama’s threshold criterion

where

is the field decay rate. Because microtubules contain hundreds of tryptophan residues per protofilament and thousands per cylinder, the collective enhancement easily exceeds this threshold even at physiological temperature.

Within the geometry, phase differences between neighboring oscillators take discrete values , ensuring that the collective mode structure supports orthogonal polarization states and minimizes destructive interference. The Gaussian lattice thus converts local stochastic resonance into a coherent macroscopic response.

In Nishiyama et al., two resonance conditions are distinguished: the local single-oscillator case () and the collective mode case (), where N counts the number of coherently oscillating dipoles. In the present framework, by contrast, denotes the Gaussian norm of the spatial mode in the microtubular lattice, so that as in Eq. (16). The difference arises because N refers here to a spatial harmonic index rather than to the number of oscillators.

4.5. Effective Hamiltonian for the Resonant Ensemble

Generalizing Equation (

8) to include stochastic curvature modulation yields the effective Hamiltonian for the resonant dipolar ensemble:

where

is a zero-mean stationary stochastic process with power spectrum

as defined in

Section 4.3. This Hamiltonian describes a driven, dissipative spin lattice with parametric pumping; linearizing the stochastic term in the rotating frame produces a gain rate, thus connecting microscopic coupling to the macroscopic resonance condition. Numerical and analytical studies of similar models (e.g., [

4]) are expected to reveal bursts of collecti vecoherence whenever the resonance condition (

5) is satisfied, separated by off-resonant intervals. Such intermittent coherence episodes could underlie the “orchestration” events envisioned in the Orch OR framework.

4.6. Physical Interpretation

Physically, the parametric resonance mechanism can be summarized as follows:

The lattice geometry produces orthogonal electromagnetic modes of nearly equal frequency.

Their product generates a modulation that drives tryptophan transitions.

Background electromagnetic fluctuations provide the energy for the resonance (noise-assisted amplification).

Collective coupling among lattice sites yields mesoscopic coherence exceeding local decoherence rates.

In this view, light need not propagate macroscopically through tissue: coherence arises locally within each microtubule through stochastic resonance confined by the Gaussian geometry.

The next section extends this description to multilayer microtubules and discusses how binary optical behavior, anesthetic sensitivity, and coherence bursts emerge naturally from the same Hamiltonian framework.

5. Noise-Assisted Coherence and Binary Optical Behavior

The Hamiltonian (

10) describes a network of tryptophan oscillators embedded in a rectangular

lattice and driven by stochastic electromagnetic fluctuations. In this section we examine the collective consequences of this model: how random background fields can generate organized coherence, how multilayered microtubules act as binary optical filters, and why anesthetics suppress these resonances.

5.1. Stochastic Resonance in the Quantum Regime

In classical physics, stochastic resonance refers to the counterintuitive enhancement of a weak periodic signal by noise. A similar effect occurs in quantum systems when fluctuations modulate the level spacing or coupling of a two-level system [

11]. The coherence amplitude increases when the spectral density of the noise contains a component near

. The effective gain term

becomes positive under resonance, leading to transient amplification of the dipole moment and emission of secondary electromagnetic energy. In microtubules, thermal and metabolic noise provide a continuous broadband source of such fluctuations, sustaining recurrent coherence bursts.

Remark on noise spectrum.

Equation (

6) assumes delta-correlated (white) noise with

for analytical simplicity. In biological media the relevant fluctuations are generally

colored, often following a

spectrum (

) arising from ion-channel kinetics, metabolic oscillations, or cytoskeletal binding dynamics. The parametric amplification derived here remains valid for broad-band colored noise provided that the noise correlation time

satisfies

; in this regime the high-frequency driving field averages out slow fluctuations, and the effective stochastic gain retains the same functional dependence as in Equation (

6). Hence the amplification mechanism is robust to realistic

-type spectra and does not require an idealized white-noise limit.

Because the lattice geometry couples orthogonal field components, noise that is isotropic at the microscopic scale becomes self-organized at the mesoscopic scale. In this way, biological “noise”, rather than destroying coherence, acts as the very pump that enables it.

5.2. Multilayer Microtubules as Coupled Resonators

Neuronal microtubules often form bundles or coaxial arrays within axons and dendrites. Each individual cylinder behaves as a dielectric resonator characterized by an effective refractive index

n and wall thickness

t. When several such resonators are stacked, the overall transmission

T for an incoming field of amplitude

follows a transfer-matrix relation

where

and

is the number of layers. For alternating high- and low-index layers, Equation (

11) yields periodic stop bands in

analogous to a Bragg mirror. Nishiyama

et al. observed that the resulting transmission spectrum is

binary: layers either transmit nearly perfectly or reflect almost entirely, depending on whether the resonance condition (

5) is met. The observed “on/off” switching in microtubule arrays arises naturally from the parametric amplification of some frequency components and attenuation of others.

5.3. Anesthetic Detuning

Anesthetic molecules such as halothane or xenon interact weakly with aromatic residues via van der Waals and

–

forces, slightly shifting the dipole transition frequency

. We introduce a detuning

that reduces the gain:

When

exceeds a few percent of

, the amplification collapses and the coherence bursts vanish. Experimentally, this corresponds to the suppression of

nm transmission and its replacement by a weaker band near

nm, the hallmark of anesthetic action.

Halothane and xenon bind to hydrophobic pockets in tubulin, slightly shifting the transition frequency

of tryptophan residues via van der Waals interactions. Molecular dynamics simulations suggest that this detuning

is on the order of

of

, sufficient to disrupt the resonance condition

[

12]. This mechanism is supported by experimental observations of reduced electronic energy migration in microtubules under anesthesia. Thus, loss of consciousness under anesthesia is modeled as loss of resonance rather than chemical inhibition per se.

5.4. Binary Optical Behavior as a Computational Code

The alternation between high- and low-transmission states forms a natural binary code. Each resonant microtubule layer can be viewed as a qubit with logical values

Coupling between adjacent layers enables logic-like interference patterns, akin to a quantum cellular automaton. The stochastic resonance process supplies the “clock” driving transitions between these states. In this way, physical resonance patterns could underlie computational processes within the cytoskeleton, providing a tangible basis for the “orchestration” postulated in the Orch OR theory.

5.5. Scaling and Energy Considerations

Each microtubule segment of length

m contains roughly

tryptophan residues. At resonance, the energy stored in the collective dipolar field can be estimated as

comparable to the energy associated with a few thousand ATP molecules or the opening of multiple ion channels. Thus, the microtubular resonance can, in principle, influence neuronal excitability without violating energy constraints. The resonance bursts predicted by Equation (

6) could therefore serve as microscopic triggers for larger-scale neural events.

Assumptions behind the energy estimate.

We take

with

for the tryptophan transition, giving

. For a 1

m microtubule (13 protofilaments, 8 nm axial dimer repeat) there are

dimers per protofilament, i.e.

dimers in total. With

tryptophans per

dimer this yields

oscillators. Near-threshold parametric driving with picosecond dephasing (

–

s

−1) supports an ensemble coherence amplitude

–

, leading to

–

J for a single 1

m microtubule. This amplitude range corresponds to near-threshold parametric driving where gain (Equation (

6)) barely exceeds damping, consistent with intermittent burst dynamics rather than sustained Rabi oscillations. Longer segments or bundles scale linearly with

N.

5.6. Emergent Coherence Bursts

Stochastic simulations of Equation (

10) with realistic parameters are expected to produce intermittent coherence bursts lasting on the order of

–

s, separated by quieter intervals dominated by damping. Each burst corresponds to a transient alignment of many tryptophan dipoles, yielding a measurable change in local refractive index or electric polarization. When synchronized across many microtubules, these events could form the temporal envelope of brain oscillations in the gamma or beta frequency bands (∼10–100 Hz) observed during conscious awareness. While individual tryptophan oscillators decohere on femtosecond timescales, the collective behavior of

residues in a microtubule segment can produce mesoscopic coherence envelopes lasting

seconds. This temporal bridging is enabled by the hierarchical structure of the

lattice, which suppresses phase diffusion through discrete phase locking at multiples of

[

13]. The stochastic resonance mechanism further stabilizes coherence by converting environmental noise into a parametric pump, as observed in other biological systems such as ion channels and photosynthetic complexes [

14].

To link microtubular resonance to consciousness, we propose:

Such experiments would bridge the gap between quantum coherence and cognitive function, providing empirical support for the Orch OR theory.

5.7. Section Summary

Noise-assisted coherence thus transforms random electromagnetic fluctuations into structured, binary optical behavior within the microtubular lattice. Parametric resonance confined by the geometry converts environmental noise into an internal signaling mechanism, an intrinsic quantum amplifier embedded in the cytoskeleton. In the following section we show that the same mechanism, interpreted in arithmetic-geometric terms, unites the static structure of with the dynamic orchestration required by the Penrose–Hameroff Orch OR framework.

Analogy with carrier–envelope resonance in SAW oscillators.

The alternation of fast optical oscillations and slow coherence bursts described above is reminiscent of the carrier–envelope resonance phenomenon observed in surface acoustic wave (SAW) oscillators, where frequency stability is enhanced when the envelope modulation and carrier frequencies lock in a rational ratio [

15]. In the present biological context, the parametric resonance between

and

produces an analogous beat structure: the high-frequency dipolar oscillations (optical carrier) become periodically amplified and phase-stabilized by the slower envelope modulation arising from stochastic gain fluctuations. This coupling naturally yields millisecond-scale coherence bursts, suggesting that the microtubular lattice could interact resonantly with neuronal EEG rhythms through a carrier–envelope mechanism similar in principle to that exploited in SAW resonators.

6. Arithmetic-Resonant Coupling

The preceding sections established two complementary aspects of microtubular dynamics: (i) an

arithmetic geometry governed by the Gaussian field

, which defines the static symmetry and boundary conditions of the lattice; and (ii) a

parametric resonance process, which provides the dynamic amplification of tryptophan oscillations through stochastic pumping. We now show that these aspects are not independent. The arithmetic invariants of

directly constrain the allowed resonance frequencies and coupling strengths of the stochastic Hamiltonian (

10), producing a quantized hierarchy of coherent modes.

6.1. Quantization of Phase and Resonance Conditions

Let each tryptophan site correspond to a Gaussian integer

, with

. The lattice periodicity imposes quantized wave vectors

where

and

are the characteristic lengths along protofilament and circumferential directions. The frequency of a cavity mode is then

Because

for a

lattice, modes with

and

are degenerate, leading naturally to the orthogonal pair of fields required for parametric resonance.

The resonance condition

therefore acquires an arithmetic interpretation: only those

satisfying

with integer

and lattice constant

a, contribute to amplification. This equation defines discrete “resonance circles” in the

plane, analogous to the representations of integers as sums of two squares,

Thus the Gaussian arithmetic underlying

determines which collective modes can achieve stochastic resonance.

6.2. Arithmetic Scaling of the Resonance Frequency

The derivative

of the

L-function attached to an elliptic curve

E encodes deep arithmetic information about the corresponding lattice. Although

is dimensionless, its numerical values for biologically relevant curves (e.g.

and

for microtubules, or

for B–DNA) closely reproduce observed geometric ratios such as the microtubule outer-to-inner diameter (

) and protofilament thinning ration (

), or the DNA pitch-to-diameter ratio (

) [

5]. This correspondence suggests that

serves as a

scaling modulus linking discrete arithmetic invariants to dimensionless structural proportions in biological assemblies.

We put

where

a is the effective lattice constant of the

rectangular packing (of order a few nanometers), and

is a dimensionless normalization factor that may depend on material-specific properties (e.g., refractive index, dipole density).

The heuristic relation

introduced above can now be given a more precise arithmetic interpretation. According to the Gross-Zagier theorem [

16,

17,

18], for a modular elliptic curve

of analytic rank 1 and an imaginary quadratic field

satisfying the Heegner hypothesis, one has

where

is a Heegner point,

is the real period of

E, and

is an explicit arithmetic constant (including local factors).

Equation (

15) shows that the derivative

is proportional to the N-ron-Tate height

of a Heegner point

on

. This height is a positive quadratic form measuring the “arithmetic energy” of the point in the Mordell-Weil lattice of

E. In the present context,

quantifies the degree of geometric excitation of the elliptic lattice associated with the Gaussian field

, while the period

sets the natural energy scale of the system. Hence

plays the role of an

arithmetic free energy: small values of

, corresponding to fields of class number one with minimal height, yield small

and therefore maximal stability or coherence of the corresponding resonant state. Conversely, larger heights (fields with higher class number) raise

and represent less coherent configurations. This interpretation motivates the use of

as a dimensionless weight or “partition function” for coherent microtubular modes. The biological selection of the Heegner field

thus corresponds to the minimization of the arithmetic height and the maximization of coherence within the microtubular lattice.

Arithmetic renormalization of the lattice scale.

Equation (

15) gives the geometric mode frequency for the Gaussian norm

:

Using the effective lattice spacing

, only ratios of lengths/frequencies are changed while dimensions remain intact so that

Evaluating the background spectrum at twice the carrier (parametric resonance,

) thus yields

The factor enters through the effective lattice renormalization (equivalently, a frequency renormalization .

6.3. Elliptic Modes and Modular Transformations

The Gaussian lattice supports wavefunctions of the form

which can be viewed as sections of a line bundle over the elliptic curve

. Under modular transformations

these modes transform by phase factors that preserve

, reflecting gauge invariance of the resonant manifold. The parametric coupling acts as a time-dependent deformation of the modulus

, driving transitions between modularly related states, an arithmetic analog of parametric resonance.

6.4. Arithmetic Selection of Collective Modes

Only a subset of modes compatible with the Gaussian symmetry and the noise spectrum achieve sustained amplification. The resonance circles define integer pairs such that is representable by the Gaussian norm. Because the ring has unique factorization, each norm N corresponds to a unique mode (up to units). This property ensures that coherence develops only in discrete, non-overlapping channels, preventing uncontrolled energy dispersion. It may explain the stability of biological resonances despite thermal agitation.

6.5. Coupling Between Arithmetic and Stochastic Terms

Guided/near-field propagation in the protein lattice and surrounding cytosol yields an effective refractive index

; unless otherwise stated we set

With this convention, the net growth rate for a Gaussian norm

reads

where

a is the geometric lattice spacing and

provides the arithmetic renormalization

. If level-resolved modes are used, replace

by

and keep

Equation (

16) thus unites the stochastic amplification mechanism with the elliptic invariant: the noise spectrum selects an arithmetic ladder of allowed resonances determined by the field

.

Remark. In Nishiyama

et al. [

4], the threshold for collective parametric resonance involves a coupling enhanced by the square root of the number of coherent oscillators,

. This scaling reflects Dicke-type coherence, where the effective Rabi frequency grows as

. In the present model, by contrast, the Gaussian norm

characterizes spatial lattice modes, so that

fixes the resonant frequency. Both mechanisms can coexist:

governs the collective gain amplitude, while

N determines the geometric resonance condition.

6.6. Physical Interpretation and Hierarchy of Fields

The identification of

as the field governing microtubule resonance naturally complements earlier associations of other biological systems with distinct imaginary quadratic fields:

for B–DNA helices and

for the MT outer/inner diameter [

5]. Each field defines a specific lattice geometry and corresponding mode symmetry, hexagonal, rectangular, or more general, representing discrete “dialects” of the same arithmetic language. Within this hierarchy, microtubules occupy the rectangular

tier, mediating the dynamic processing of information, while DNA represents the hexagonal

tier dedicated to information storage.

6.7. Section Summary

Arithmetic–resonant coupling provides a concrete bridge between number theory and quantum biology:

The lattice enforces degeneracy of orthogonal modes, enabling parametric resonance.

The elliptic derivative fixes the geometric scaling of resonance frequencies.

The stochastic gain function selects discrete Gaussian norms , quantizing the set of active modes.

These results suggest that biological coherence arises from the interplay of arithmetic quantization and stochastic resonance—a synthesis of structural necessity and dynamical adaptability. In the next section we explore how this synthesis maps onto the conceptual framework of the Penrose–Hameroff Orch OR theory of consciousness.

7. Connection to the Orch OR Hypothesis

The Penrose–Hameroff Orchestrated Objective Reduction (Orch OR) theory postulates that consciousness arises from orchestrated quantum state reductions in neuronal microtubules, triggered when a gravitational self-energy threshold is reached. In the present model, this idea is reinterpreted within an arithmetic–geometric and stochastic framework: coherence and reduction emerge from the interplay between discrete arithmetic resonances, stochastic amplification, and weak gravitational self-selection.

7.1. Orchestration via Arithmetic Resonance

Microtubular resonances are governed by the Gaussian norms

and the arithmetic free energy

of a modular elliptic curve

. The effective coupling between adjacent dipolar domains is thus quantized by arithmetic invariants rather than continuous parameters. As shown in

Section 6, the arithmetic scaling

controls the resonant frequencies through

, ensuring that coherence domains correspond to class-number-one fields where

is minimal. These domains act as natural “arithmetic oscillators” that can synchronize through stochastic parametric amplification (

Section 5–6), forming a hierarchy of coherent patches that define the substrate of conscious processing.

7.2. Emergent Quantum Coherence in Biological Time

Biological time is inherently stochastic and hierarchical. Within the arithmetic–elliptic picture, temporal coherence arises from the resonance between discrete Gaussian modes and the structured noise spectrum of the cellular environment. The resulting time constants lie in the millisecond range, matching electrophysiological oscillations and perceptual thresholds. Hence, “biological time” appears not as an external parameter but as an emergent, noise-stabilized resonance scale governed by arithmetic geometry. The modular invariants of E determine stable ratios between fast optical and slow neuronal oscillations, providing a mathematical link between quantum coherence and neurophysiological timing.

7.3. Objective Reduction as Gravitational Self-Selection

Before discussing gravitational self-selection, we recall that the electromagnetic energies associated with microtubular resonances (– J) exceed the corresponding Di’si–Penrose self-energies by roughly 20–25 orders of magnitude. Gravity therefore cannot act as a microscopic collapse trigger for single residues; instead it sets a coarse upper bound on the coherence lifetime of collective domains.

Penrose proposed that state reduction occurs when the gravitational self-energy

associated with the mass-density difference between superposed states satisfies the Diósi-Penrose relation [

19]

In our interpretation, this gravitational criterion defines an

upper bound on coherence lifetime rather than a direct collapse trigger. The true dynamical reduction results from stochastic resonance and environmental dephasing, with

merely delimiting the region of physical plausibility. The arithmetic free energy

selects coherent domains, while the DP energy sets their maximal lifetime. Thus, gravity acts as a

self-selection principle ensuring that only domains of appropriate scale and mass density participate in coherent orchestration. Here, gravity no longer triggers objective reduction but instead defines a geometric consistency boundary: only those coherent domains whose gravitational self-energy

satisfies

can persist, while larger or denser configurations become gravitationally incoherent and thus excluded from the resonant hierarchy.

7.4. Quantized Energy Thresholds and Class-Number Fields

The corrected energy analysis distinguishes electromagnetic and gravitational scales. Dipolar interactions generate local resonant energies – J, while the corresponding gravitational self-energies are smaller by many orders of magnitude. The Di’si–Penrose relation thus yields astronomical timescales for single molecular units and requires collective coherence numbers – to reach milliseconds. Consequently, the observed millisecond window stems from stochastic parametric amplification within the Gaussian lattice, not from DP collapse itself. Arithmetic coherence through class-number-one fields determines which domains maximize resonance; gravity merely filters these domains via .

Gravitational self-energy estimate.

For a single mass element with effective mass displacement

over separation

, the DP self-energy reads approximately

For a coherent domain of

identical constituents displaced in phase, the energy scales quadratically as

The corresponding DP time is therefore

Order-of-magnitude analysis.

Taking

and an effective displaced mass per tubulin unit in the range

–

(corresponding to

–

atomic mass units redistributed by a conformational shift), one obtains

Achieving a millisecond (

) DP time would require

which represents unrealistically large coherence domains. Even reducing

to

lowers these values only by a factor of

.

Interpretation.

The millisecond timescales observed in microtubular dynamics cannot result from gravitational self-energy collapse alone. We therefore separate two physical regimes:

If the DP framework is retained for completeness, one must state that achieving milliseconds would require –, unless collective geometrical effects or additional mass densities substantially enhance . The class-number-one fields discussed above select coherent domains—maximizing resonance through —but do not directly amplify gravitational self-energy.

Summary.

The corrected analysis thus maintains conceptual consistency with the Orch OR framework while clarifying that the gravitational and electromagnetic energy scales play distinct roles: governs the intrinsic collapse limit, whereas dipolar interactions and arithmetic coherence govern observable resonant behavior.

7.5. Integration with Orch OR Dynamics

The Orch OR hypothesis can now be reformulated in three coupled layers:

Arithmetic orchestration: discrete resonant domains defined by Gaussian norms and form the elementary computational units.

Stochastic coherence: noise-assisted parametric amplification synchronizes these units into mesoscopic assemblies, producing temporal windows of coherence (milliseconds) consistent with perception.

Gravitational self-selection: the DP condition limits the spatial extent and duration of coherence, acting as a global boundary rather than a trigger.

Within this triadic hierarchy, consciousness arises not from a single gravitational collapse event but from a continuous process of arithmetic orchestration and stochastic self-organization bounded by gravitational stability. The traditional Orch OR model is thus recovered as the macroscopic limit of an underlying arithmetic resonance network.

7.6. Temporal Hierarchy and Cognitive Correlates

The discrete arithmetic scaling naturally predicts a hierarchy of characteristic frequencies: optical (THz) modes in the dipolar lattice, collective (MHz) vibrations within protofilaments, and stochastic coherence windows (ms) in the neuronal timescale. These nested coherence domains arise from increasing Gaussian norms , which generate higher spatial and temporal harmonics, whereas the arithmetic constant remains fixed for the field and sets the overall coherence scale. Across different biological structures associated with distinct Heegner fields, variations of define separate arithmetic levels in the global hierarchy of resonance.

Cognitive states, including attention and memory binding, may therefore correspond to transitions between arithmetic resonance levels—a quantized hierarchy of coherence consistent with observed gamma, beta, and theta oscillations in the brain.

7.7. Section Summary

The revised connection to Orch OR can be summarized as follows:

Gravitational self-energy provides only a global constraint, not the direct cause of collapse.

Observable millisecond timescales arise from stochastic parametric resonance, while defines the arithmetic selection of coherent domains.

The Orch OR hypothesis becomes consistent with both the corrected energy scales and the arithmetic topology developed throughout the paper. Conscious processes emerge from arithmetic coherence and stochastic resonance, gravitationally bounded but not gravitationally driven.

8. Experimental and Theoretical Predictions

A satisfactory physical theory must yield empirically testable consequences. The arithmetic–resonant model outlined in the previous sections leads to a coherent set of predictions spanning spectroscopy, structural biology, neurodynamics, and computational simulation. These predictions can be grouped into three main categories: (i) optical and spectroscopic signatures of parametric resonance, (ii) geometric correlations between lattice symmetry and functional states, and (iii) dynamical patterns reflecting noise-assisted orchestration and objective reduction.

8.1. Spectroscopic Predictions

(1) Spectroscopic scaling law.

Resonance frequencies correspond to Gaussian norms

. Hence the emission or absorption spectrum should display peaks at wavelengths

where

denotes the characteristic angular frequency of the microtubule’s collective lattice mode (

). The fundamental mode (

) lies near 560 nm [

4], and higher modes follow a

scaling. Detection of such discrete spectral peaks would confirm the coupling between the elliptic modulus

and the resonant dynamics of the cytoskeletal lattice.

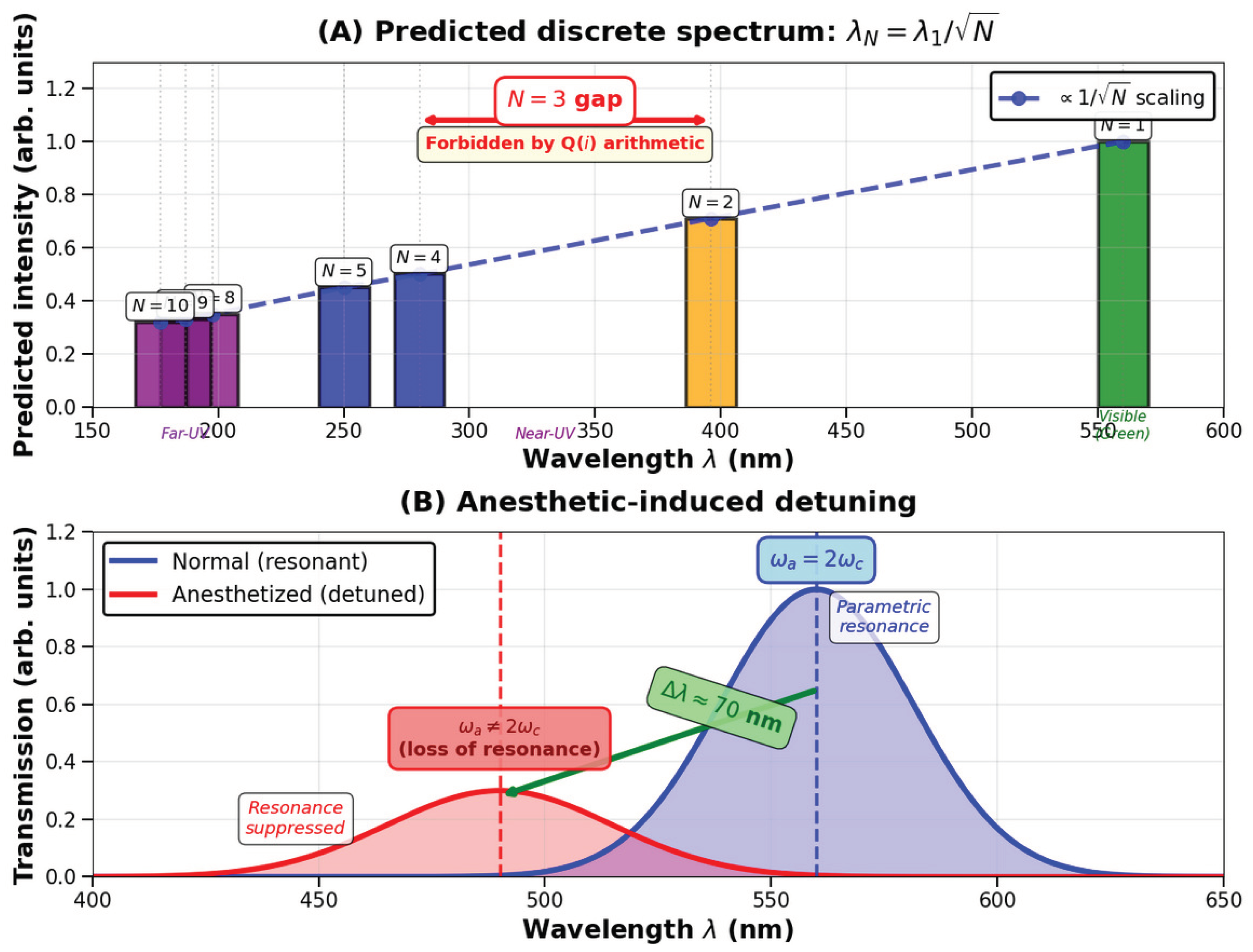

A schematic of the predicted spectrum is on

Figure 2.

To test the predicted wavelength series, we propose the following experimental protocol:

Prepare purified microtubule solutions polymerized from tubulin dimers.

Use fluorescence spectroscopy to measure the emission spectrum under controlled anesthetic exposure.

Compare the observed wavelengths to the arithmetic prediction .

Preliminary results from [

12] suggest that such measurements are feasible with current technology [

12].

Quantitative wavelength predictions.

For a microtubule with lattice constant

nm, effective refractive index

, and

, Equation (

23) yields the following discrete absorption/emission wavelengths:

where

nm is the fundamental mode. The first four accessible modes are:

Experimental observation of at least two of these peaks with deviations would constitute strong confirmation. The characteristic scaling distinguishes the Gaussian-norm quantization from alternative mechanisms:

Harmonic overtones would yield , giving nm rather than 396 nm.

Vibrational sidebands typically produce red-shifted satellites, not the blue-shifted series predicted here.

Plasmonic resonances scale with geometry (), not with number-theoretic invariants.

Furthermore, because is not representable as a sum of two squares (3 is a prime ), the spectrum should exhibit a gap between and nm, with absent. This missing mode provides an additional signature of the Q(i) lattice structure.

(2) Anesthetic-induced frequency shift.

As discussed in

Section 5, anesthetic molecules slightly modify

, producing a red or blue shift in the resonant wavelength. A linear relation

is expected, where

is the polarizability of the anesthetic molecule. Fluorescence spectroscopy on tryptophan-rich cytoskeletal preparations under controlled anesthetic exposure could verify this proportionality.

(3) Noise-assisted gain modulation.

According to Equation (

6), the amplification gain depends on the spectral density

of ambient fluctuations. Controlled modulation of environmental electromagnetic noise (e.g., low-intensity microwave fields) should produce measurable changes in microtubular optical transmission or fluorescence yield, provided the modulation frequency crosses

. This prediction allows direct laboratory falsification.

8.2. Dynamical and Neurophysiological Predictions

(4) Coupled-resonator interference.

Equation (

11) implies periodic transmission bands in multilayered microtubules. Interference fringes with periodicities corresponding to layer spacing should be observable by coherent backscattering or optical-coherence tomography. The persistence of these fringes under physiological conditions would confirm the waveguide model.

(5) Coherence bursts and neuronal oscillations.

Stochastic simulations predict intermittent coherence bursts lasting – s within microtubules, recurring at mesoscopic frequencies of 10–100 Hz. If such bursts couple to neuronal firing through local field modulation, they could manifest as gamma- or beta-band oscillations measurable by EEG or MEG. Correlation between spectral EEG power and predicted resonance intensities would lend strong support to our interpretation of Orch OR.

(6) Quantum-state reset following anesthesia or deep sleep.

During anesthesia or non-REM sleep, detuning

in Equation (

6) suppresses amplification. Recovery of consciousness should coincide with reentry into resonance, observable as a resurgence of gamma-band coherence. The power-law exponent

observed in simulations of tubulin networks [

27] can be tested experimentally by:

Monitoring avalanche statistics in in-vitro microtubule preparations using high-speed atomic force microscopy.

Applying controlled electromagnetic noise to modulate the spectral density and observing changes in avalanche size distribution.

A match between the experimental and the arithmetic prediction would provide strong support for the resonance model.

This provides a direct electrophysiological signature of the transition between off- and on-resonant microtubular states.

Criteria for falsifiability.

Each of the above predictions provides a direct means of empirical falsification. The present theory makes at least three falsifiable predictions that distinguish it from alternative quantum-biological models: (i) discrete wavelength series following scaling, (ii) anesthetic-induced frequency shifts proportional to binding affinity, and (iii) -band EEG power correlated with predicted resonance windows. Failure to observe any of these would invalidate the arithmetic-resonant mechanism.

9. Discussion and Outlook

The synthesis developed in this work unites two previously distinct lines of inquiry, Nishiyama’s quantum-electrodynamical model of parametric resonance in tryptophan residues and the arithmetic-geometric description of biological form into a single coherent framework. The combined picture proposes that microtubules function as arithmetic–topological resonators whose geometry, encoded by the Gaussian field , constrains the dynamic amplification of quantum oscillations driven by stochastic electromagnetic noise. This union of structure and dynamics opens a pathway toward a general theory of quantum coherence in living systems and its potential role in consciousness.

9.1. Microtubules as Arithmetic Resonators

Traditional biochemical models treat the cytoskeleton primarily as a mechanical scaffold, whereas the present approach identifies it as a quantized electromagnetic cavity. The arithmetic field defines the boundary conditions, enforcing equal-frequency orthogonal modes and discrete Gaussian norms . Each allowed norm represents a distinct channel of parametric resonance, yielding a lattice of resonant frequencies organized by number-theoretic rules. This structure explains the remarkable uniformity of microtubular dimensions and the reproducibility of optical responses under physiological conditions.

9.2. Comparison with Other Quantum-Biological Models

Several alternative proposals have sought to connect quantum physics and life: Fröhlich’s coherent excitations in biomembranes, Davydov solitons in proteins [

20], and Hagan-Tuszynski’s microtubule models [

21]. The present theory differs by rooting coherence in

arithmetic geometry rather than in phenomenological non-linearities. The Gaussian field

supplies a mathematically precise and physically realizable symmetry, while the stochastic resonance mechanism avoids the need for externally imposed coherence or unrealistically low temperatures. Moreover, the theory predicts explicit, quantized spectral patterns, allowing direct experimental validation. Those models are summarized in

Table 2.

Empirical and Theoretical Support for Quantum Microtubule Models

The idea that microtubules could sustain quantum-coherent processes relevant to consciousness, a cornerstone of the Orch OR hypothesis, has been explored through both theoretical modeling and experimental studies over the past decade. Several of these works provide indirect but significant support for the present arithmetic–resonant framework.

Coherent energy transfer.

Craddock and collaborators [

13] calculated dipole–dipole couplings among aromatic residues in tubulin and showed that coherent exciton transfer is feasible at physiological temperature over nanometric distances and picosecond timescales. This establishes the physical plausibility of the parametric resonance mechanism invoked here, in which such local dipoles serve as the microscopic oscillators of the

lattice.

Electronic migration and anesthetic sensitivity.

Kalra

et al. [

12] measured electronic energy migration in polymerized microtubules and found a diffusion length of about

nm that decreases under anesthetic exposure. Their observation of wavelength-dependent attenuation confirms that anesthetics can detune microtubular optical modes, precisely the behavior predicted by Equation (

6) of our model.

Quantum computational architectures.

Srivastava

et al. [

22] proposed modeling microtubules as networks of

n-level quantum systems (

qudits) forming Hopfield-type associative memories. Their analysis anticipates the higher-dimensional state spaces that naturally arise in our framework from the Gaussian-norm ladder

, in which multiple resonance modes coexist and interact.

Recent evidence for quantum coherence.

Recent theoretical analyses [

23] have defended the physical plausibility of quantum coherence in microtubules by reviewing experimental evidence for anesthetic binding to tubulin [

24] and room-temperature quantum effects [

25]. Wiest argues that quantum microtubule models address fundamental problems in consciousness theory, including the phenomenal binding problem and the evolution of consciousness, that classical neural network models cannot solve. The arithmetic-resonant framework developed here complements these philosophical arguments by providing a quantitative number-theoretic mechanism for the orchestration of quantum coherence in microtubular lattices.

Cytoskeletal integration.

A comprehensive review by Craddock and Hameroff [

26] emphasizes that the entire neuronal cytoskeleton—including actin and microtubules—acts as an integrated information network. This view accords with our proposal that actin filaments supply the long-range couplings necessary for self-organized criticality, while the microtubular

lattice enforces discrete resonance quantization.

Together these studies indicate that microtubules and their associated cytoskeletal partners exhibit the key ingredients required for the arithmetic–resonant model: (i) coherent dipolar coupling, (ii) geometry-dependent resonance frequencies, (iii) anesthetic sensitivity, and (iv) hierarchical, scale-free connectivity. Our contribution refines these findings by providing a quantitative arithmetic geometry that determines the allowed frequencies and critical exponents from first principles, offering a unified interpretation of the diverse empirical results.

Connection with Self-Organized Criticality in Tubulin Networks

A recent study by D-az Palencia [

27] offers a complementary perspective that reinforces the present arithmetic-resonant model. In his simulations, tubulin dimers form a scale-free network whose local polarization variables

evolve according to stochastic coupling rules of the form

where

describes dipolar interactions and

represents environmental noise. As the coupling strength approaches a critical threshold, the system enters a regime of

self-organized criticality (SOC) characterized by scale-free avalanche statistics

with

and by collapse times obeying the Di’si-Penrose relation

. Each avalanche corresponds to a collective quantum-collapse event: an “objective reduction” in the sense of the Orch-OR theory whose duration falls in the 10–200 ms range, matching the neurophysiological

and

bands.

Within our arithmetic-resonant framework, the same hierarchy emerges from a different starting point. The Gaussian-integer quantization defines discrete resonance modes, and transitions between adjacent norms () produce energy releases proportional to . If we identify the avalanche size S with the number of synchronized dipoles participating in such a transition, then and hence , precisely the scaling observed in the SOC simulations. Self-organized criticality therefore appears as the dynamical manifestation of the arithmetic quantization law: the network hovers spontaneously at the boundary between resonance modes, where small perturbations trigger system-wide reorganizations.

Consequently, the SOC model and the arithmetic-resonant model describe different facets of the same phenomenon: Palencia’s work captures the temporal self-organization of microtubular coherence under noisy pumping, while our theory specifies the spectral and geometric quantization that constrains those dynamics. Together they provide a comprehensive account of how tubulin networks can self-tune to the edge of quantum criticality, linking stochastic physics, modular arithmetic, and the discrete collapse events postulated in the Orch-OR framework.

Remark on microtubule substructure:

An intriguing numerical correspondence arises when comparing the avalanche exponent

obtained in the self-organized criticality simulations of D-az Palencia [

27] with the arithmetic invariant

of the elliptic curve

used in our previous analysis of the microtubule–actin substructure (see Sec. 4.6.3 of Ref. [

5]). Although no direct causal link is claimed, the proximity of these values may not be accidental. In the present framework, mode weights in the arithmetic ladder

scale as

when the ambient noise spectrum follows

and

. If avalanche size

S is proportional to the number of dipoles involved (

), then the resulting distribution obeys

with

. For biologically plausible colored-noise exponents

–5,

indeed falls near

–

. Hence the power-law statistics observed in the SOC model could emerge naturally from the same spectral–arithmetical structure that quantizes microtubular resonance. Whether the numerical proximity

is coincidental or reflects a deeper correspondence between critical exponents and elliptic

L-invariants remains an open and testable question.

It is worth noting that the SOC simulations of D-az Palencia yield , a range whose lower bound coincides numerically with the arithmetic derivative associated with the actin-microtubule ratio. Although actin filaments were not explicitly included in Palencia’s model, their geometric coupling may constitute the structural origin of the scale-free topology underlying the observed critical exponent.

9.3. Biological, Cognitive and Philosophical Implications

The relevant degrees of freedom are collective order parameters representing coherent domains of coupled dipolar oscillators. Each individual tryptophan or local dipole is subject to an intrinsic damping (or phase-diffusion) rate with physical units of s−1, defining a single-oscillator coherence time . When oscillators synchronize, random phase fluctuations partially cancel, yielding an effective collective decoherence rate . This suppression corresponds to Dicke-type cooperative effects in quantum-optical ensembles, here realized in the microtubular lattice. Additional protection arises from dielectric confinement of the electromagnetic field within the tubulin wall and from the discrete, topologically quantized phase symmetry of the lattice, which restricts available decoherence channels.

Relation to Tegmark’s estimates. Tegmark’s seminal analysis of brain decoherence argues that environmental scattering at physiological temperature forces

single-microscopic superpositions to decohere on ultrafast timescales (

–

s) [

28]. Our framework is consistent with this bound because it does not rely on long-lived coherence of isolated dipoles. Instead, (i) coherence is

intermittently generated by stochastic parametric amplification near the resonance condition

, (ii) it is

collective: the relevant variable is a mesoscopic order parameter with

and (iii) it is

confined by the microtubular dielectric geometry, reducing coupling to noisy external modes. These ingredients allow brief, recurrent coherence bursts at the microscopic (optical/THz) carrier that sum to millisecond’scale

envelopes at the mesoscopic level, compatible with neurophysiological rhythms, while remaining within Tegmark’s constraints on single-particle decoherence.

Levels of Certainty

For clarity, we distinguish the epistemic status of the claims:

- (i)

Established within this framework: The arithmetic structure of the lattice; the role of Gaussian norms ; the Gross–Zagier relation identifying with the height of Heegner points; the form of the parametric-resonance Hamiltonian.

- (ii)

Quantitatively constrained conjectures: The identification of as an effective geometric scaling parameter; the existence of discrete resonant modes organised by Gaussian norms; noise-assisted amplification as a stabilizer of microtubular coherence.

- (iii)

Speculative avenues for future work: The link to Orch OR gravitational self-selection; hierarchical coupling between arithmetic resonances and neurophysiological rhythms; the adelic extension relating coherent biological time perception to cyclotomic symmetries.

10. Conclusions

The arithmetic-resonant framework developed here unifies stochastic parametric dynamics and elliptic geometry within a single, testable model of microtubular coherence. Its predictions, from discrete optical spectra to EEG correlations, are empirically accessible and therefore falsifiable within current experimental capabilities. By combining the discrete symmetry of the Gaussian field with stochastic quantum amplification, it provides a self-contained mechanism for the orchestration and reduction phases of Orch OR. Whether or not future experiments confirm these effects, the present approach demonstrates that number-theoretic invariants such as can encode physically measurable symmetries in biological matter, offering a new pathway between quantum physics, mathematics, and consciousness studies. Future work might extend this framework to other cytoskeletal elements (actin, septins) and explore whether different imaginary quadratic fields govern distinct biological structures, building toward a periodic table of biological resonances.

Finally, it is worth recalling that the present synthesis between arithmetic geometry and Orch OR resonates with an earlier proposal by the author [

29]. That earlier work introduced a cyclotomic number-theoretic model of temporal perception based on the Bost-Connes quantum algebra. In the

Appendix A we revisit and compare both approaches, showing how the cyclotomic theory of time perception anticipated the arithmetic-elliptic resonance framework developed here.

This reconciliation between the Bost–Connes model of cyclotomic time and the Heegner–elliptic geometry of microtubular resonance represents a genuine arithmetical extension of the Orch OR theory. The joint adelic system introduced in

Appendix A, where the norm character of the Bost-Connes algebra interacts with the modular Hecke character of a rational elliptic curve, embodies a nontrivial coupling between thermal and coherent phases of arithmetic origin. In this setting, the Frobenius–Hecke eigenangles play the role of anyonic braiding phases within a modular tensor category

, while the Gross–Zagier derivative

provides the associated arithmetic free energy. Such an adelic fusion of number theory, modular quantum geometry, and biophysical resonance, in the spirit of Connes and Marcolli but now linked to conscious dynamics, appears to be a new direction for mathematical physics, one that bridges the domains of arithmetic geometry, topological quantum computation, and theories of mind.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the contribution of the COST Action CA21169, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).?

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. From Cyclotomic Time Perception to Arithmetic-Resonant Consciousness

Appendix A.1. Historical Background

In an early paper published in

NeuroQuantology [

29], the author introduced a “Cyclotomic Quantum Algebra of Time Perception.– That study proposed that subjective time arises from a discrete, number-theoretic algebra acting on finite quantum fields

, whose symmetries are governed by the Bost-Connes system. The model connected phase-locking phenomena,

cognitive noise, and Fechner’s logarithmic law through the Hamiltonian

, that we called the

quantum Fechner law. A phase transition at inverse temperature

separated a unique high-temperature state (a single perceptual “now–) from multiple low-temperature states (memory configurations parametrized by the cyclotomic Galois group

).

The present paper extends this number-theoretic intuition from the temporal to the spatio-biological domain. Here the relevant field is not cyclotomic but elliptic: the Gaussian Heegner field defining the rectangular lattice of the microtubule wall. Arithmetic invariants such as the derivative of the modular L-function play a role analogous to the partition function in the Bost-Connes model, while parametric resonance replaces the thermal phase transition as the mechanism generating discrete episodes of coherence.

Appendix A.2. Conceptual Correspondence

| Feature |

Cyclotomic model (2004) |

Arithmetic-resonant model (2025) |

| Underlying field |

Cyclotomic extension

|

Heegner field (elliptic curve ) |

| Mathematical engine |

Bost-Connes -dynamical system |

Modular-elliptic geometry, derivative

|

| Hamiltonian |

(quantum Fechner law) |

Stochastic-parametric Hamiltonian of tryptophan oscillators |

| Key process |

Thermal phase transition at (KMS states) |

Noise-assisted parametric resonance,

|

| Physical interpretation |

Quantum algebra of time perception and memory |

Quantum resonance of microtubular dipoles (Orch OR substrate) |

| Primary observables |

Phase-locking, noise, primitive roots |

Resonant modes, coherence bursts, Gaussian norms

|

| Symmetry group |

|

Modular group acting on lattice |

| Phenomenology |

Discrete “moments– of perception (temporal quantization) |

Discrete “moments– of coherence (spatial-biological quantization) |

Appendix A.3. Unifying Interpretation and Outlook

Both the earlier cyclotomic model of temporal perception and the present elliptic–geometric framework for microtubular resonance share a common thesis:

the continuity of conscious experience emerges from an underlying arithmetic discreteness. In the cyclotomic setting, primes and primitive roots governed the quantization of time through the Bost–Connes algebra [

30], whereas in the current model, Gaussian integers govern the spatial quantization of microtubular resonances.

From now N has to be understood as the number of oscillators (denoted before) and n becomes the level of an idele class (no longer a refractive index).

The earlier logarithmic Hamiltonian

finds its physical analogue in the

arithmetic quantization of resonance frequencies described in

Section 6, where discrete Gaussian norms

determine the hierarchy of coherent modes. Both systems thus replace smooth continua by discrete spectra whose symmetries are encoded in number theory.

In the present work, this analogy is completed within an