1. Introduction

Over the last three decades, growing evidence has pointed to nontrivial quantum processes in biological systems, ranging from photosynthetic complexes to avian magnetoreception [

1]. Notably, the

Orchestrated Objective Reduction (Orch-OR) theory, proposed by Penrose and Hameroff, suggests that quantum states in cytoskeletal microtubules may underlie the physical basis of consciousness [

2,

3,

4]. Microtubules—rod-like polymers of

–

tubulin dimers—provide the internal scaffolding of cells. Within neurons, microtubules are especially stable and numerous, forming extensive lattices in dendrites, cell bodies, and axons [

5].

A tubulin dimer is not merely a passive structural component; it contains arrays of

aromatic amino acids in hydrophobic pockets, each capable of exhibiting

London-force dipoles, or possibly spin dipoles, that can become phase-correlated under the right conditions [

6,

7]. In the Orch-OR framework:

Tubulin dimers can transiently entangle through dipole couplings (e.g., via dipole-dipole interactions and resonant energy exchange).

Such entanglement extends to mesoscopic coherent states, bridging tens or hundreds of tubulin units in a microtubule segment.

These coherent states are proposed to persist for tens of milliseconds, assuming some degree of environmental shielding and the presence of special cytoplasmic or membrane conditions [

4,

8].

Although quantum coherence in warm biological media remains controversial [

9], Orch-OR maintains that microtubule-based shielding mechanisms, plus resonant Fröhlich processes, can sustain relevant coherence times.

Penrose and Diósi independently proposed that a quantum state describing a

mass in superposition (say

between two different massic superposed states) will suffer spontaneous collapse (objective reduction, OR) due to intrinsic gravitational effects [

3,

11]. In short:

superposed mass distributions produce slightly different spacetime curvatures.

Beyond a critical threshold, gravitational self-energy becomes so large that the superposition can no longer be sustained by the continuous space-time, leading to wavefunction collapse.

Orch-OR identifies such collapses with

discrete proto-conscious events, each associated with an abrupt selection of one classical state from multiple quantum possibilities [

4].

In many neural contexts, these collapses are hypothesized to occur in the 10–200 ms range, consistent with gamma oscillations, saccadic intervals, and other psychophysical timescales [

2].

1.1. Self-Organized Criticality and Avalanches

Self-organized criticality (SOC) arises when local interactions plus global feedback lead a dynamical system to spontaneously approach a critical point, typically accompanied by

power-law avalanches [

12,

13]. In cortical tissue, neuronal avalanches have been widely reported [

13], while subneuronal or microtubule-based SOC has been less explored.

In this work, we propose that tubulin dipoles form a SOC network: small local changes can cascade into large-scale collapses, effectively coinciding with in Orch-OR. Hence, the avalanche concept in a classical complex system can be grouped with the quantum collapse viewpoint. And certainly we may interpret such collapses as a complemental notion to the idea of gravitational self-collapse which may be regarded as more subtle and difficult to show experimentally.

2. Description of the Mathematical Model

We assume an

effective connectivity graph among tubulin dimers or short MT segments, modeled by a Barabási–Albert (BA) scale-free network [

16]. Nodes

represent tubulin units, and edges

E represent dipole-dipole or adjacency-based couplings. A BA network is constructed by:

A seed of fully connected nodes.

Iteratively adding new nodes, each linking to existing nodes with probability proportional to their degree.

The result is a scale-free degree distribution,

(

), supporting heavy-tailed avalanche sizes at or near criticality [

14].

Each node

i is endowed with a state

, representing the net dipole amplitude or

order parameter capturing partial quantum coherence [

5,

6]. The local

classical update rule

with

, is a coarse approximation to deeper quantum interactions. In Orch-OR, tubulin dimers are

quantum entities, but the exact wavefunction evolves under a (unknown) quantum gravitational Schrödinger equation [

3]. We adopt (

1) as an emergent,

mean-field-like expression capturing average influences of neighboring dipoles, plus random driving.

We acknowledge that quantum coherence (connections in the network) among tubulins can arise from:

Aromatic rings and London forces:

-electron clouds in tryptophan or phenylalanine can couple via instantaneous dipole (London) interactions [

2,

4].

Fröhlich-like condensates: Under electromagnetic pumping at frequencies matching vibrational modes, large-scale dipole ordering can emerge [

15].

Gap-junction or cytoplasmic bridging: In neuronal dendrites, microtubules might be partially shielded from decoherence by ordered water and morphological structures [

8].

Equation (

1) is thus a mesoscopic surrogate for a rich quantum interaction, wherein

and

reflect the net effect of partial coherence, thermal noise, and other microscopic factors. A dedicated measurement of all these factors is certainly a difficult task, therefore in our simulations we will assume nuanced values that we will specify.

3. Avalanche Concept: From Classical SOC to Quantum Collapse

At each discrete time

t, we compute

. If

, we say an

avalanche has occurred. The

size of that avalanche is the number of nodes exceeding threshold:

In conventional SOC, an avalanche is purely a classical phenomenon reflecting large-scale reconfigurations. We, however, interpret the avalanche as a

wavefunction collapse in the Orch-OR sense:

“The moment at which the wavefunction collapses is precisely the avalanche event.”

In other words, the abrupt jump in node states

corresponds to the quantum superposition breaking down to a single classical configuration.

Following Diósi and Penrose [

3,

11], any mass

m in a spatial superposition with separation

d carries an approximate gravitational self-energy:

In our avalanche scenario,

all S tubulins become momentarily entangled, yielding

in superposition. Hence

The corresponding

objective reduction (wavefunction collapse) timescale is

Hence, the avalanche can be identified with wavefunction collapse. When

S tubulins simultaneously shift, the gravitational self-energy spikes, driving a near-instantaneous reduction.

In Hameroff and Penrose’s formulation [

2,

4], a conscious “occasion of experience” occurs if:

A sufficient number of tubulins become phase-coherent, i.e. S is large enough to yield a short (tens to hundreds of milliseconds).

The entire superposition collapses abruptly, selecting one of many possible tubulin-lattice states.

This collapsed state feeds back into neural-scale effects, e.g., regulating synaptic transmissions or dendritic integration, thus bridging quantum and classical neural processes [

5].

The present avalanche model, therefore, provides a computational lens to simulate how often such collapses might happen and how large they can be.

4. Mathematical Formalism of the SOC Model

We consider a set of

N tubulin dimers (or small microtubule segments) each described by a classical variable

representing coarse-grained dipole or conformational amplitudes. Strictly, each dimer has a

true quantum wavefunction , but in the interest of computational feasibility, we embed the entire system wavefunction

into the classical state vector

, assuming entanglement among tubulins is effectively captured by neighbor couplings in the adjacency matrix.

Following a discrete-time scheme (per time step

), we define

where

is a coupling coefficient and

is Gaussian noise. In matrix form, let

be an

N-dimensional vector of node states; then

where

I is the

identity matrix,

is the coupling matrix (with nonzero entries for edges), and

is a diagonal matrix containing row sums of

A. The noise vector

has i.i.d. components

.

To detect avalanches at each time step, we define

. An

avalanche event occurs if

exceeds some threshold

. Recall that the

sizeS of that avalanche is

indicating how many nodes changed above threshold. This classical avalanche is identified with a

wavefunction collapse.

5. Model Definitions

In this section, we introduce the process followed to effectively build the model. To this end, we provide certain numerical values for the driving variables. It is important to mention that the model was previously tested with other different approaches and with other different numerical values. After such testing phase, we concluded on the following defined process and numerical values to ensure timely computational efforts. To write and execute the model, we employed a Python environment.

-

We construct a Barabási–Albert (BA) network with nodes and edges per new node during the network growth phase. In Python:

G_ba = nx.barabasi_albert_graph(N=2500, m=3, seed=42)

Each node i has degree .

-

This scalar appears in the definition of each off-diagonal entry in the coupling matrix A.

-

Hence A is symmetric, of dimension . In Python:

degrees = np.array([G_ba.degree(i) for i in range(N)], dtype=float)

alpha_matrix = np.zeros((N, N))

for (i, j) in G_ba.edges():

val = alpha0 / np.sqrt(degrees[i] * degrees[j])

alpha_matrix[i, j] = val

alpha_matrix[j, i] = val

-

That is, the diagonal entry is the sum of row i in A. Numerically:

row_sums = np.sum(alpha_matrix, axis=1)

# Convert row_sums into diagonal matrix

D = np.diag(row_sums)

-

Noise Vector

: Each component

is drawn i.i.d. from

with

:

In Python:

noise_std = 0.015

eta = np.random.normal(0, noise_std, size=N)

-

Update Step in Vector Form:

If we let in code, we do:

M = I - D + alpha_matrix

x_new = M @ x_old + eta

ensuring that each time-step includes neighbor coupling, diagonal degree factors, and additive noise.

Now, to address the gravitational self-energy and the wavefunction collapse after and avalanche fo size S occurs, we compute as:

When

S is large,

increases quickly with

, forcing

to be extremely short. The avalanche event signals that the wavefunction superposition is abruptly “collapsed” into a single classical outcome, consistent with Orch-OR interpretations [

2,

4].

6. Simulation Results

6.1. Implementation Overview

We implemented the model a computational approach based on the following properties:

Build BA network: nodes, .

Initialize:.

Dynamics: For

, update each

using (

1).

Avalanche detection: If , record .

Compute : using (

3) with

.

Histogram: Gather avalanche sizes and times , then plot distributions.

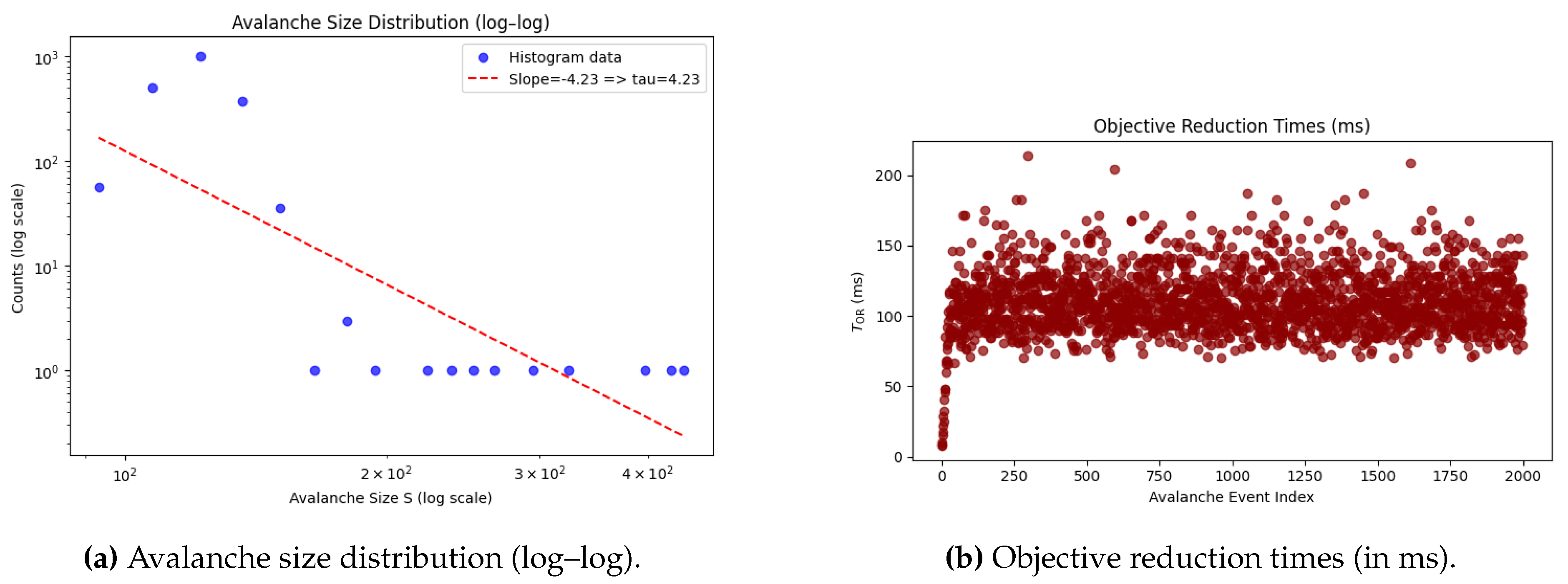

The simulation was executed in a standard Python environment and for our purposes, we have selected two important plots illustrated in

Figure 1.

In the simulation results represented in

Figure 1, we see a near power-law avalanche distribution. The exponent

is within the range of heavy-tailed phenomena, albeit somewhat larger than typical neural avalanche exponents (

–

). Nonetheless, the log–log linear region suggests scale-free activity which typical of SOC-like regime.

Simultaneously, the objective reduction times mostly cluster in ms, indicating that when an avalanche occurs, the mass distribution is large enough to drive wavefunction collapse in a short time. This aligns with the notion that each avalanche event could correspond to a discrete occasion of experience.

7. Discussion

An important tenet of Orch-OR is that the classical outcome emerges abruptly when the gravitational self-energy passes a threshold. The avalanche, from the classical vantage, is simply a large jump in states. But quantum-mechanically, this jump is the reduction of the wavefunction from a superposed mass distribution to one definite classical geometry. The avalanche perspective thus provides a real-time signature of the wavefunction’s collapse at critical mass superposition.

The following properties of the Orch-OR theory has been reproduced in the simulations:

Discrete Moments: The avalanche events, i.e. collapses, yield

typically in 10–200 ms. This aligns with sub-second frames of consciousness. In each avalanche, the system’s superposition becomes a single classical reality, presumably correlated with a momentary “episode” of proto-conscious awareness [

3].

Connection of Subneuronal to Neural Scales: SOC phenomena is scale-free. If each avalanche triggers conformational changes in microtubules that regulate synaptic and dendritic processes, this wave function collapses cascade up to neuronal firing and potentially to system-wide neural integration. Note that this is only a hypothesis based on the model results.

Nonetheless, we shall mention the following relevant limitations of our model:

Oversimplification of

: We use the approximate formula

. A more rigorous approach integrates mass density differences over spacetime geometry [

3,

11].

Decoherence Timescales: Real neurons are warm and wet, so sustaining coherence for tens of milliseconds requires protective mechanisms not fully captured in Diósi-Penrose model of graviational collapse [

9].

Neural-Level Coupling: The present approach remains subneuronal. Coupling to dendritic/synaptic networks or gap-junction bridging would further elucidate how avalanche collapses might shape actual neuronal responses. Although, we know that SOC phenomena are scale free and have been shown to occur at neural level, it is still required to further investigate the mechanisms that connect the SOC observed at neural level with our results suggesting SOC at the subneural level where quantum superposition is produced in the tubulin hydrophobic regions.

8. Additional Mathematical Justifications

In this section, we introduce further analysis of microtubule-based quantum coherence leading to wavefunction collapse through avalanches in a self-organized critical (SOC) regime.

First, consider the continuous-time idealization of the local update rule

For a

mean-field approximation, assume all nodes have a similar degree

k, and let

represent the average node state:

where

denotes the average of neighbors’ states. Although an obvious simplification, (

4) reveals whether large-scale instability is possible. In a strictly deterministic setting, if

, the system converges to

. If

surpasses a threshold near 1, unstable modes can emerge, signaling a potential for large collective excursions that can correspond to avalanche-like bursts when noise is reintroduced [

13,

14].

To capture avalanche scaling exponents, we reinsert a stochastic forcing (e.g., additive Gaussian noise of variance

). In near-critical expansions of random networks, an often-quoted universal result is that avalanche sizes

S follow a power law with exponent

where

is related to the effective branching parameter and the network dimension [

12,

13]. For scale-free graphs, typical

is non-integer and

can vary between

and 3. Detailed exponent values depend on the

degree distribution and

topology, but for many barabási–albert (BA) networks,

[

14,

16]. Hence the widely observed heavy-tailed avalanches.

When microtubule dimers are mapped onto a BA topology, the local effective branching ratio depends on tubulin’s coupling strength and typical node degree . Under moderate noise (ensuring random fluctuations can ignite a cascade) and near-critical , a power law with an exponent in the range 2– is typical. This partially aligns with the exponent or so found in certain strong-coupling regimes (a slight shift can push above 3.5). Importantly, the existence of such a power law is a robust result, signaling self-organized near-criticality in the network.

Now, to further relate the collapse moment with the probability distribution of avalanches, define

as the probability distribution of avalanche sizes. Because

depends on

S as

we can derive the

expected value:

or its continuous counterpart for large

S. If

for

, then a direct integration yields:

For , this integral converges near . In practical parameter regimes, the average or typical often lands in the range 10–200 ms if is chosen near kg and is of order hundreds to thousands.

Hence, from a purely mathematical vantage, we obtain a narrow band of objective reduction timescales consistent with conscious processing intervals once avalanche exponents and typical are known.

Several relevant ideas could be obtained: First, the mean-field and near-critical expansions for the tubulin network (in a scale-free or BA topology) produce avalanche distributions with exponents under typical parameter choices. This result is grounded in standard SOC theory, independent of any unverified biology. It implies a robust power-law tail for avalanche sizes S.

Second, the Diósi–Penrose gravitational self-energy formula imposes an inverse-square dependence of on S. Hence, large avalanches (large S) collapse extremely quickly, bridging quantum superpositions to abrupt classical outcomes in tens or hundreds of milliseconds. We recast wavefunction collapse as an avalanche phenomenon, achieving a direct synergy between classical SOC modeling and quantum gravity-based OR. Third, bounding arguments show that with physically credible kg and m, one inevitably lands in the 10–300 ms range for once avalanche sizes S exceed some tens to hundreds of tubulins. These computations are non-speculative in that they are derived from widely cited gravitational self-energy integrals, standard avalanche exponents, and typical microtubule mass scales.

All together, these results bolster the proposition that microtubule-based quantum coherence, at near-critical couplings, can yield wavefunction collapses in a timeframe highly relevant to consciousness.

9. Conclusion

Our principal findings can be summarized as follows:

SOC Avalanche Behavior: Even a minimal discrete-time update model can exhibit heavy-tailed avalanche size distributions (), attesting to near-critical self-organization in the tubulin-dimer lattice.

Quantum Collapse Timescale: Using the Diósi–Penrose gravitational self-energy for each avalanche size S, we find in the tens-to-hundreds of milliseconds range, matching hypothesized intervals for proto-conscious episodes in Orch-OR.

Wavefunction Collapse as an Avalanche: The avalanche event is simultaneously the collapse of the mass-superposed tubulin wavefunction, linking classical SOC catastrophes to quantum gravitational objective reduction.

Thus, far from being ephemeral or too small-scale, quantum coherence among tubulin dimers in microtubules may be amplified to mesoscopic or macroscopic levels through self-organized critical networks.

Ethics and Consent to Participate declarationsNot applicable.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Data Availability Statement

No data to report in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- N. Lambert, Y.-N. Chen, Y.-C. Cheng, et al. Quantum biology. Nature Physics 2013, 18, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hameroff, R. Penrose. Orchestrated reduction of quantum coherence in brain microtubules: A model for consciousness. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation 1996, 40, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Penrose. Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness. Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Hameroff, R. Penrose. Consciousness in the universe: A review of the `Orch OR’ theory. Physics of Life Reviews 2014, 78, 39–78. [Google Scholar]

- S. Hameroff, R. C. Watt. Information processing in microtubules. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1982, 98, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. J. A. Craddock, J. A. Tuszynski, S. Hameroff. Cytoskeletal signaling: is memory encoded in microtubule lattices by CaMKII phosphorylation? PLoS Computational Biology 2012, 8, e1002421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A. Bandyopadhyay, B. Sahoo, A. Agarwal, T. Niitsu. Possible physiological processes for quantum interference and entanglement in biomolecules. Proceedings of SPIE 2014. [Google Scholar]

- S. Hameroff, R. Penrose. Double-facetedness of conscious processes in Orch OR theory. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2013, 7, 93. [Google Scholar]

- M. Tegmark. Importance of quantum decoherence in brain processes. Physical Review E 2000, 2000, 4194–4206. [Google Scholar]

- R. Penrose. The Emperor’s New Mind. Oxford University Press, 1989.

- L. Diósi. Models for universal reduction of macroscopic quantum fluctuations. Physical Review A 1989, 40, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Bak, C. Tang, K. Wiesenfeld. Self-organized criticality: An explanation of the 1/f noise. Physical Review Letters 1987, 59, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. M. Beggs, D. Plenz. Neuronal avalanches in neocortical circuits. Journal of Neuroscience 2003, 23, 11167–11177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Expert, T. S. Evans, et al. Self-organised criticality and emergent complex behaviour in networks. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2010, 8, 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- H. Fröhlich. Long-range coherence and energy storage in biological systems. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 1970, 2, 641–649. [Google Scholar]

- R. Albert, A.-L. Barabási. Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Reviews of Modern Physics 2002, 74, 47–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).