Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

05 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Individual Differences in the Affective Experience of Writing a Gratitude Letter: Who Benefits Most?

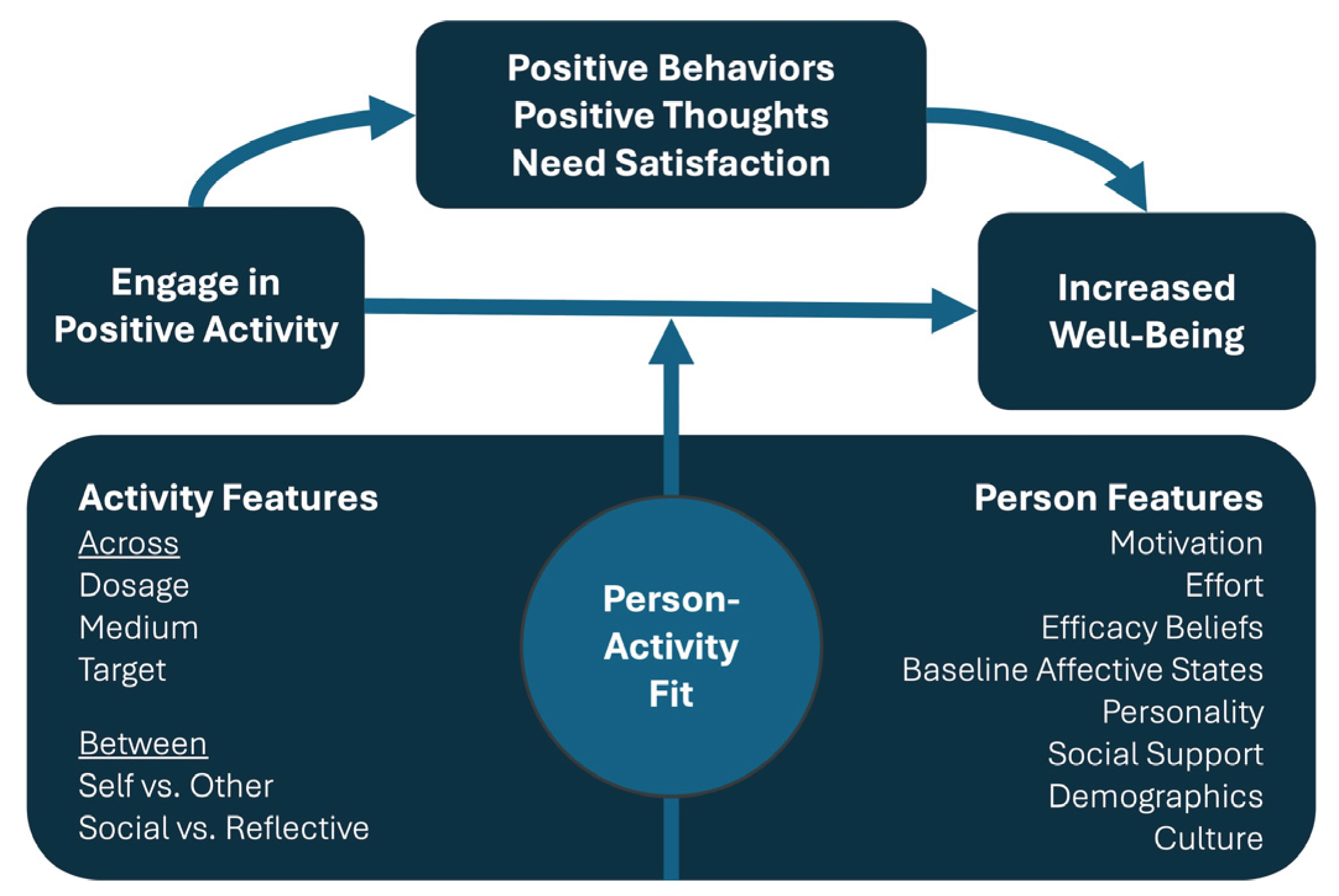

Writing Gratitude Letters: The Role of Person-Activity Fit

Past Research on the Effects of Gratitude PAIs Based on Person Features

Demographics

Personality

Activity Effort

Trait Gratitude

Baseline Affective States

The Present Study

Activity Fit Predictions: Do Distinct Affect Clusters Emerge?

Person Features Predictions: Who Benefits Most from Gratitude Interventions?

Methods

- Regan, Walsh, Lyubomirsky (2022; n = 157), henceforth the Ways of Expressing Gratitude study (https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-022-00160-3).

- Walsh, Regan, Twenge, Lyubomirsky (2022; n = 231), henceforth the Optimal Way to Give Thanks study (https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-022-00150-5).

- Walsh, Regan, Lyubomirsky (2022; n = 99), henceforth the Thanking Parents study (https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1991449).

Data Preparation

Participants

Activity Fit Measures

Person Features Measures

Coding the Gratitude Letters

Data Exclusion Criteria

Analytic Approach

Results

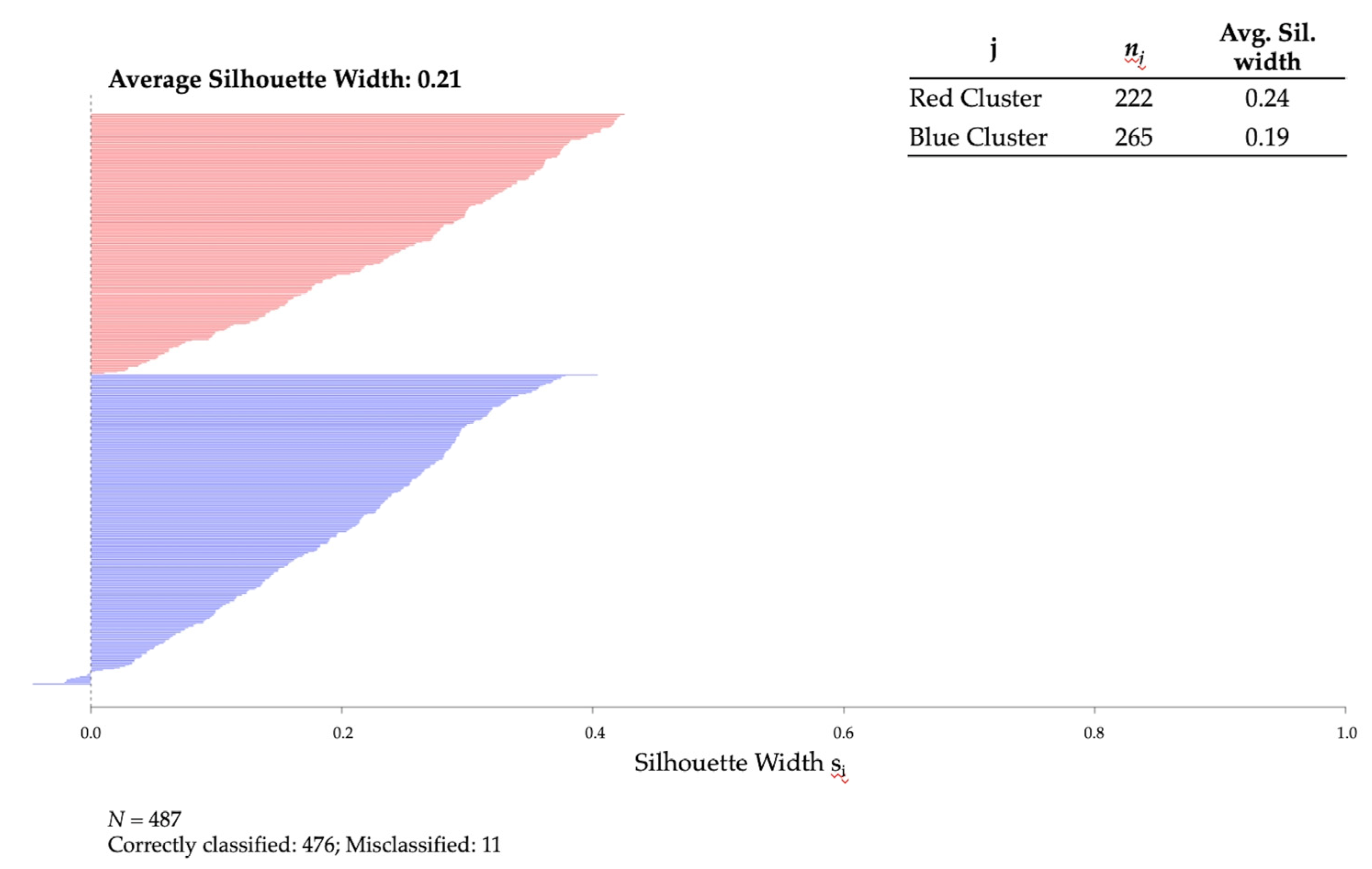

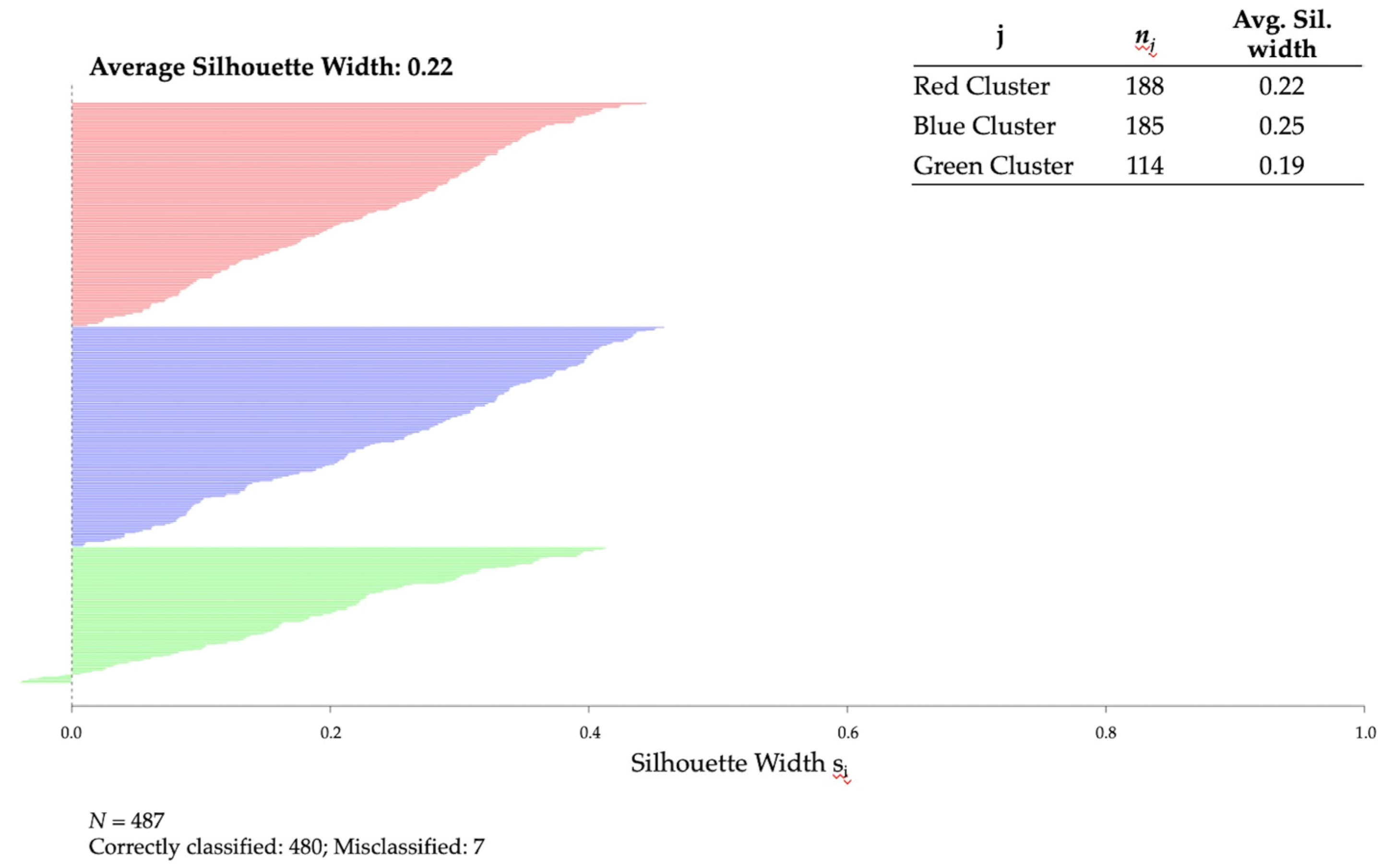

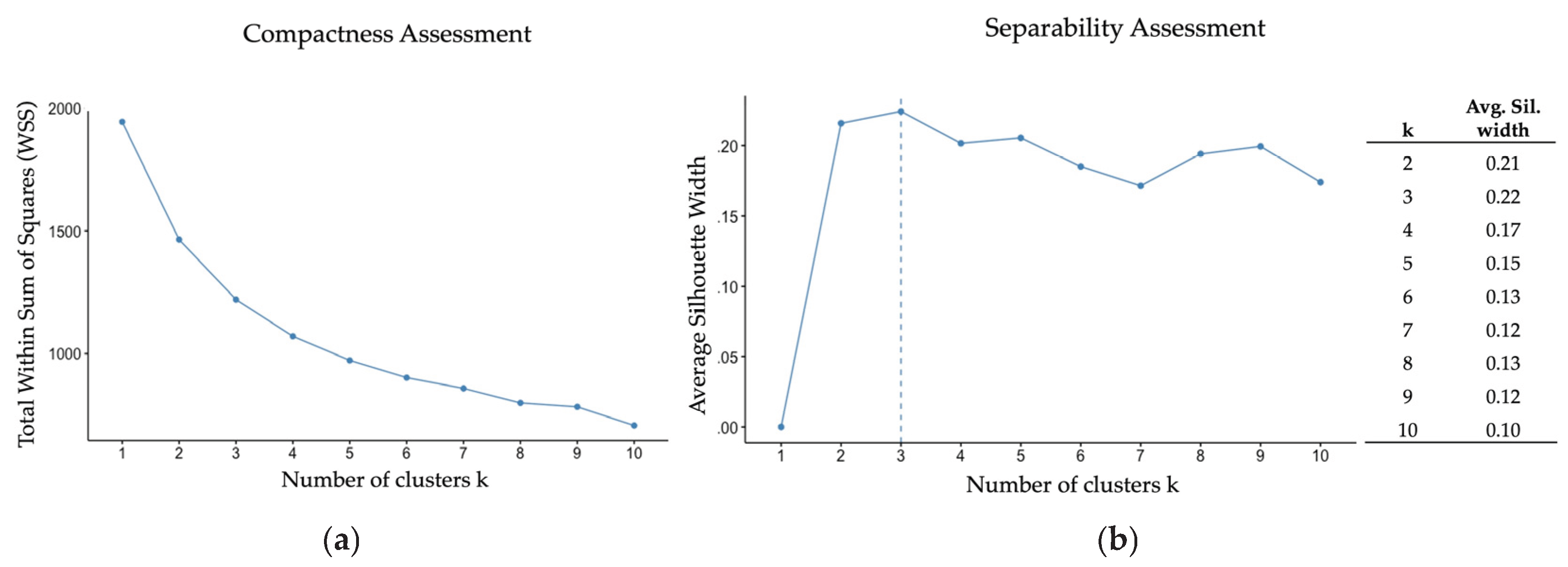

Do Distinct Affect Clusters Emerge After Writing a Gratitude Letter?

Demographics

Personality

Baseline Affect and Trait Gratitude

Activity Effort

Coded Gratitude Letters

Discussion

Do Distinct Affect Clusters Emerge After Writing a Gratitude Letter?

Who Benefits Most—and Least—from Writing a Gratitude Letter?

Limitations

Conclusions

Who Might Benefit?

Who Might not Benefit as Much?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Tables

| Merged Dataset |

Ways of Expressing Gratitude Study |

Optimal Way to Give Thanks Study |

Thanking Parents Study |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 487) | (n = 157) | (n = 231) | (n = 99) | |

| Age (M ± SD in years) | 28 (15.7) | 47 (15.6) | 19 (1.85) | 19 (1.5) |

| Generation | ||||

| Gen Z | 67% | 5% | 99% | 91% |

| Millennial | 12% | 30% | 1% | 9% |

| Gen X | 9% | 28% | 0% | 0% |

| Boomer | 10% | 32% | 0% | 0% |

| 2% | 5% | 0% | 0% | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 62% | 50% | 66% | 73% |

| Male | 38% | 50% | 33% | 27% |

| Other | 0% | 0% | 1% | NA |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 34% | 85% | 8% | 14% |

| Black | 6% | 10% | 3% | 9% |

| Hispanic | 24% | 0% | 35% | 35% |

| Asian | 26% | 0% | 44% | 24% |

| Other | 10% | 5% | 10% | 17% |

| Relationship Status | ||||

| Single, not in a relationship | 38% | 17% | 69% | NA |

| Relationship | 19% | 15% | 29% | NA |

| Cohabiting | 3% | 8% | 0% | NA |

| Single (not defined) | 20% | NA | NA | 100% |

| Married | 15% | 44% | 1% | 0% |

| Divorced/Separated | 5% | 14% | 0% | 0% |

| Widowed | 1% | 3% | 0% | 0% |

| Present Study |

Ways of Expressing Gratitude Study |

Optimal Way to Give Thanks Study |

Thanking Parents Study |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | Elev | NA | SCA | PA | Elev | NA | SCA | PA | Elev | NA | SCA | PA | Elev | NA | SCA | |

| Positive Affect (PA) |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Elevation (Elev) |

.48 | 1 | .46 | 1 | .56 | 1 | .38 | 1 | ||||||||

| Negative Affect (NA) |

-.37 | -.27 | 1 | -.34 | -.10 | 1 | -.51 | -.48 | 1 | -.32 | .01 | 1 | ||||

| Self-Conscious Affect (SCA) |

-.06 | -.02 | .39 | 1 | -.01 | -.01 | .41 | 1 | -.07 | -.13 | .39 | 1 | -.15 | .15 | .38 | 1 |

| PC1 | PC2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect | .57 | .34 |

| Elevation | .52 | .44 |

| Negative Affect | -.56 | .33 |

| Self-Conscious Affect | -.31 | .76 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.36 | 1.06 |

| Proportion of Variance | .46 | .28 |

| Cumulative Proportion | .46 | .74 |

| Items | Backfired | Mixed Feelings | Buffered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect | |||

| Happy | -0.63 | 0.47 | 0.25 |

| Pleased | -0.58 | 0.51 | 0.10 |

| Joyful | -0.58 | 0.54 | 0.05 |

| Enjoyment | -0.45 | 0.52 | -0.13 |

| Elevation | |||

| Moved | -0.51 | 0.52 | -0.04 |

| Uplifted | -0.63 | 0.55 | 0.11 |

| Optimistic about humanity | -0.46 | 0.46 | -0.01 |

| A warm feeling in your chest | -0.57 | 0.50 | 0.11 |

| A desire to help others | -0.44 | 0.39 | 0.06 |

| A desire to become a better person | -0.38 | 0.39 | -0.01 |

| Negative Affect | |||

| Unhappy | 0.54 | -0.02 | -0.83 |

| Worried/Anxious | 0.40 | -0.10 | -0.49 |

| Angry/Hostile | 0.42 | 0.11 | -0.88 |

| Frustrated | 0.53 | -0.06 | -0.76 |

| Depressed/Blue | 0.48 | -0.03 | -0.74 |

| Self-Conscious Affect | |||

| Indebted | -0.16 | 0.46 | -0.51 |

| Guilty | 0.18 | 0.22 | -0.66 |

| Embarrassed | 0.20 | 0.25 | -0.73 |

| Uncomfortable | 0.29 | 0.18 | -0.76 |

| Ashamed | 0.21 | 0.27 | -0.78 |

| Backfired | Mixed Feelings | Buffered | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | |

| (n = 185) | (n = 188) | (n = 114) | |

| Age (M ± SD in years) | 27 (15.0) | 28 (17.2) | 29 (14.2) |

| Generation | |||

| Gen Z | 69% C | 70% C | 58% |

| Millennial | 12% | 9% | 18% |

| Gen X | 9% | 6% | 14% |

| Boomer | 9% | 12% | 11% |

| Silent | 2% | 3% | 0% |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 60% | 62% | 66% |

| Male | 40% | 38% | 33% |

| Other | 1% | 0% | 1% |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 32% | 32% | 41% |

| Black | 7% | 5% | 9% |

| Hispanic | 25% | 23% | 24% |

| Asian | 27% | 30% | 18% |

| Other | 10% | 10% | 9% |

| Relationship Status | |||

| Single, no relationship | 41% | 36% | 37% |

| Relationship | 20% | 19% | 17% |

| Cohabiting | 3% | 3% | 2% |

| Single (not defined) | 19% | 23% | 18% |

| Married | 14% | 13% | 18% |

| Divorced/Separated | 4% | 4% | 8% |

| Widowed | 1% | 2% | 0% |

| Backfired | Mixed Feelings | Buffered | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personality | (A) | (B) | (C) |

| Neuroticism | |||

| Mean | 3.06 | 2.96 | 3.67 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.00 |

| Pairwise Comparison | - | - | AB |

| Agreeableness | |||

| Mean | 3.73 | 3.88 | 3.57 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| Pairwise Comparison | - | C | - |

| Conscientiousness | |||

| Mean | 3.51 | 3.45 | 3.23 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.85 |

| Pairwise Comparison | C | - | - |

| Openness | |||

| Mean | 3.59 | 3.47 | 3.34 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.85 |

| Pairwise Comparison | C | - | - |

| Extraversion | |||

| Mean | 3.02 | 2.82 | 2.81 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| Pairwise Comparison | - | - | - |

| Personality Type | Contrast | Diff | p Adj | Cohen’s D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | -0.10 | .718 | -0.09 |

| Neuroticism | Buffered-Backfired | 0.61 | <.000 | 0.57 |

| Neuroticism | Buffered-Mixed Feelings | 0.71 | <.000 | 0.66 |

| Agreeableness | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | 0.14 | .241 | 0.19 |

| Agreeableness | Buffered-Backfired | -0.16 | .233 | -0.22 |

| Agreeableness | Buffered-Mixed Feelings | -0.31 | .007 | -0.40 |

| Conscientiousness | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | -0.07 | .797 | -0.07 |

| Conscientiousness | Buffered-Backfired | -0.28 | .037 | -0.33 |

| Conscientiousness | Buffered-Mixed Feelings | -0.22 | .142 | -0.25 |

| Openness | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | -0.12 | .386 | -0.15 |

| Openness | Buffered-Backfired | -0.24 | .047 | -0.31 |

| Openness | Buffered-Mixed Feelings | -0.12 | .452 | -0.16 |

| Extraversion | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | -0.19 | .177 | -0.21 |

| Extraversion | Buffered-Backfired | -0.21 | .204 | -0.23 |

| Extraversion | Buffered-Mixed Feelings | -0.02 | .990 | -0.02 |

| Backfired | Mixed Feelings | Buffered | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Affect | (A) | (B) | (C) |

| Positive Affect | |||

| Mean | 4.47 | 3.95 | 3.70 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.31 | 1.29 | 1.37 |

| Pairwise Comparison | BC | - | - |

| Elevation | |||

| Mean | 4.18 | 3.77 | 3.73 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.24 | 1.20 | 1.34 |

| Pairwise Comparison | BC | - | - |

| Negative Affect | |||

| Mean | 2.29 | 2.35 | 3.85 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.04 | 1.07 | 1.30 |

| Pairwise Comparison | - | - | AB |

| Self-Conscious Affect | |||

| Mean | 1.71 | 1.61 | 2.80 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.82 | 0.85 | 1.10 |

| Pairwise Comparison | - | - | AB |

| Trait Gratitude | |||

| Mean | 5.89 | 5.73 | 5.39 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.01 | 1.12 | 1.31 |

| Pairwise Comparison | C | C | - |

| Measure | Contrast | Diff | p Adj | Cohen’s D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect T0 | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | -0.52 | <.000 | -0.40 |

| Positive Affect T0 | Buffered-Backfired | -0.78 | <.000 | -0.59 |

| Positive Affect T0 | Buffered-Mixed Feelings | -0.25 | .243 | -0.19 |

| Elevation T0 | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | -0.42 | .004 | -0.33 |

| Elevation T0 | Buffered-Backfired | -0.45 | .007 | -0.36 |

| Elevation T0 | Buffered-Mixed Feelings | -0.04 | .967 | -0.03 |

| Negative Affect T0 | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | 0.06 | .857 | 0.05 |

| Negative Affect T0 | Buffered-Backfired | 1.55 | <.000 | 1.39 |

| Negative Affect T0 | Buffered-Mixed Feelings | 1.49 | <.000 | 1.34 |

| Self-Conscious Affect T0 | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | -0.10 | .535 | -0.11 |

| Self-Conscious Affect T1 | Buffered-Backfired | 1.09 | <.000 | 1.21 |

| Self-Conscious Affect T2 | Buffered-Mixed Feelings | 1.19 | <.000 | 1.32 |

| Trait Gratitude | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | -0.17 | .331 | -0.15 |

| Trait Gratitude | Buffered-Backfired | -0.50 | .001 | -0.45 |

| Trait Gratitude | Buffered-Mixed Feelings | -0.34 | .032 | -0.30 |

| Backfired | Mixed Feelings | Buffered | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effort | (A) | (B) | (C) |

| Mean | 5.40 | 5.71 | 5.65 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.24 |

| Pairwise Comparison | - | - | - |

| Measure | Contrast | Diff | p Adj | Cohen’s D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effort | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | 0.33 | .058 | 0.28 |

| Effort | Buffered-Backfired | 0.36 | .089 | 0.31 |

| Effort | Buffered-Mixed Feelings | 0.03 | .979 | 0.03 |

| Coding Theme | Contrast | Diff | p Adj | Cohen’s D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Writer effort | Buffered-Backfired | -0.04 | .977 | -0.03 |

| Writer effort | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | 0.44 | .037 | 0.38 |

| Writer effort | Mixed Feelings-Buffered | 0.48 | .029 | 0.42 |

| Level of detail | Buffered-Backfired | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 |

| Level of detail | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | 0.51 | .007 | 0.47 |

| Level of detail | Mixed Feelings-Buffered | 0.51 | .011 | 0.47 |

| Heartfelt sincerity | Buffered-Backfired | 0.03 | .978 | 0.03 |

| Heartfelt sincerity | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | 0.38 | .039 | 0.38 |

| Heartfelt sincerity | Mixed Feelings-Buffered | 0.35 | .087 | 0.34 |

| Reflection depth | Buffered-Backfired | -0.02 | .997 | -0.01 |

| Reflection depth | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | 0.48 | .017 | 0.42 |

| Reflection depth | Mixed Feelings-Buffered | 0.50 | .020 | 0.44 |

| Genuineness | Buffered-Backfired | -0.03 | .989 | -0.02 |

| Genuineness | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | 0.44 | .021 | 0.41 |

| Genuineness | Mixed Feelings-Buffered | 0.47 | .020 | 0.44 |

| Superficiality | Buffered-Backfired | -0.18 | .547 | -0.18 |

| Superficiality | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | -0.50 | .003 | -0.50 |

| Superficiality | Mixed Feelings-Buffered | -0.32 | .109 | -0.33 |

| Benefactor effort | Buffered-Backfired | -0.19 | .515 | -0.19 |

| Benefactor effort | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | 0.30 | .147 | 0.29 |

| Benefactor effort | Mixed Feelings-Buffered | 0.49 | .010 | 0.48 |

| Backfired | Mixed Feelings | Buffered | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Word Count | (A) | (B) | (C) |

| Mean | 114.61 | 135.56 | 107.05 |

| Standard Deviation | 86.94 | 75.04 | 68.67 |

| Pairwise Comparison | - | - | - |

| Measure | Contrast | Diff | p Adj | Cohen’s D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Words in Letter | Buffered-Backfired | -7.56 | .834 | -0.10 |

| Number of Words in Letter | Mixed Feelings-Backfired | 20.96 | .185 | 0.27 |

| Number of Words in Letter | Mixed Feelings-Buffered | 28.52 | .061 | 0.37 |

Appendix B. Figures

References

- Algoe, S. B., Gable, S. L., & Maisel, N. C. (2010). It’s the little things: Everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 17(2), 217–233. [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. (1993). The structure and properties of the Sense of Coherence scale. Social Science & Medicine, 36(6), 725–733. [CrossRef]

- Armenta, C. N., Fritz, M. M., Walsh, L. C., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2022). Satisfied yet striving: Gratitude fosters life satisfaction and improvement motivation in youth. Emotion, 22(5), 1004–1016. [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 57, 289–300. [CrossRef]

- Bono, G., & Sender, J. T. (2018). How gratitude connects humans to the best in themselves and in others. Research in Human Development, 15(3-4), 224–237. [CrossRef]

- Breen, W. E., Kashdan, T. B., Lenser, M. L., & Fincham, F. D. (2010). Gratitude and forgiveness: convergence and divergence on self-report and informant ratings. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(8), 932–937. [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, L. N., John, D. R., Rindfleisch, A., & Froh, J. J. (2018). The impact of gratitude on adolescent materialism and generosity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(4), 502–511. [CrossRef]

- Chopik, W. J., Newton, N. J., Ryan, L. H., Kashdan, T. B., & Jarden, A. J. (2019). Gratitude across the life span: Age differences and links to subjective well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(3), 292–302. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Corona, K., Senft, N., Campos, B., Chen, C., Shiota, M., & Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E. (2020). Ethnic variation in gratitude and well-being. Emotion, 20(3), 518–524. [CrossRef]

- Dickens, L. R. (2017). Using gratitude to promote positive change: A series of meta-analyses investigating the effectiveness of gratitude interventions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(4), 193–208. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1105–1117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.47.5.1105.

- Dunn, J. R., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2005). Feeling and believing: The influence of emotion on trust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(5), 736–748. [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389. [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R. A., & Mishra, A. (2011). Why gratitude enhances well-being: What we know, what we need to know. In K. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan & Steger, M. F. (Eds.), Designing positive psychology: Taking stock and moving forward (1st ed., pp. 248-262). Oxford University Press. https://academic.oup.com/book/4376.

- Folk, D., & Dunn, E. (2023). A systematic review of the strength of evidence for the most commonly recommended happiness strategies in mainstream media. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(10), 1697–1707. [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300–319. [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 359(1449), 1367–1378. [CrossRef]

- Froh, J. J., & Bono, G. (2008). The gratitude of youth. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Positive psychology: Exploring the best in people, Vol. 2. Capitalizing on emotional experiences (pp. 55–78). Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Froh, J. J., Bono, G., & Emmons, R. (2010). Being grateful is beyond good manners: Gratitude and motivation to contribute to society among early adolescents. Motivation and Emotion, 34(2), 144–157. [CrossRef]

- Froh, J. J., Emmons, R. A., Card, N. A., Bono, G., & Wilson, J. A. (2011). Gratitude and the reduced costs of materialism in adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(2), 289–302. [CrossRef]

- Froh, J. J., Kashdan, T. B., Ozimkowski, K. M., & Miller, N. (2009a). Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention in children and adolescents? Examining positive affect as a moderator. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(5), 408–422. [CrossRef]

- Froh, J. J., Sefick, W. J., & Emmons, R. A. (2008). Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. Journal of School Psychology, 46(2), 213–233. [CrossRef]

- Froh, J. J., Yurkewicz, C., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009b). Gratitude and subjective well--being in early adolescence: Examining gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 633–650. [CrossRef]

- Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2, 156– 168. [CrossRef]

- Götz, F. M., Gosling, S. D., & Rentfrow, J. (2021). Small effects: The indispensable foundation for a cumulative psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(1), 205–215.

- Grant, A. M., & Gino, F. (2010). A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(6), 946–955. [CrossRef]

- Harbaugh, C. N., & Vasey, M. W. (2014). When do people benefit from Gratitude Practice? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(6), 535–546. [CrossRef]

- Hareli, S., & Parkinson, B. (2008). What’s social about social emotions? Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 38(2), 131–156. [CrossRef]

- Hodge, A. S., Ellis, H. M., Zuniga, S., Zhang, H., Davis, C. W., McLaughlin, A. T., Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., & Van Tongeren, D. R. (2023). Linguistic and thematic differences in written letters of gratitude to god and gratitude toward others. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 19(1), 83–94. [CrossRef]

- Howell, D. C. (2013). Statistical Methods for Psychology (8th ed.). Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- Jain, A. K. (2010). Data clustering: 50 years beyond K-means. Pattern Recognition Letters, 31(8), 651–666. [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T. B., Mishra, A., Breen, W. E., & Froh, J. J. (2009). Gender differences in gratitude: Examining appraisals, narratives, the willingness to express emotions, and changes in psychological needs. Journal of Personality, 77(3), 691–730. [CrossRef]

- Kern, M. L., Eichstaedt, J. C., Schwartz, H. A., Park, G., Ungar, L. H., Stillwell, D. J., Kosinski, M., Dziurzynski, L., & Seligman, M. E. (2014). From “Sooo excited!!!” to “so proud”: Using language to study development. Developmental Psychology, 50(1), 178–188. [CrossRef]

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for Reliability Research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Kubacka, K. E., Finkenauer, C., Rusbult, C. E., & Keijsers, L. (2011). Maintaining close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(10), 1362–1375. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., & Epley, N. (2018). Undervaluing gratitude: Expressers misunderstand the consequences of showing appreciation. Psychological Science, 29(9), 1423–1435. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N. M., Graham, S. M., Fincham, F. D., & Stillman, T. F. (2009). A changed perspective: How gratitude can affect sense of coherence through positive reframing. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 461–470. [CrossRef]

- Layous, K., Lee, H., Choi, I., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). Culture matters when designing a successful haPAIness-increasing activity: A comparison of the United States and South Korea. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(8), 1294–1303. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022022113487591.

- Layous, K., Sweeny, K., Armenta, C., Na, S., Choi, I., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2017). The proximal experience of gratitude. PLOS ONE, 12(7). [CrossRef]

- Lindström, B., Eriksson, M. (2005). Salutogenesis. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(6), 440–442. [CrossRef]

- Liu, I., Liu, F., Xiao, Y., Huang, Y., Wu, S., & Ni, S. (2024a). Investigating the key success factors of chatbot-based positive psychology intervention with retrieval and generative pre-trained transformer (GPT)-based chatbots. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 41(1), 341–352. [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S., Dickerhoof, R., Boehm, J. K., & Sheldon, K. M. (2011). Becoming happier takes both a will and a proper way: An experimental longitudinal intervention to boost well-being. Emotion, 11(2), 391–402. [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S., & Layous, K. (2013). How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(1), 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111–131. [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J.-A. (2002). The Grateful Disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112–127. [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M. E., Tsang, J.-A., & Emmons, R. A. (2004). Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: Links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 295–309. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J. M., Hardy, S. A., Tice, D., & Schnitker, S. A. (2023). Returning thanks to god and others: Prosocial consequences of transcendent indebtedness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 19(1), 121–135. [CrossRef]

- Oltean, L.-E., Miu, A. C., Șoflău, R., & Szentágotai-Tătar, A. (2022). Tailoring gratitude interventions. how and for whom do they work? the potential mediating role of reward processing and the moderating role of childhood adversity and trait gratitude. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(6), 3007–3030. [CrossRef]

- Oriol, X., Unanue, J., Miranda, R., Amutio, A. & Bazán, C. (2020). Self-transcendent aspirations and life satisfaction: The moderated mediation role of gratitude considering conditional effects of affective and cognitive empathy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Pison, G., Struyf, A., & Rousseeuw, P. J. (1999). Displaying a clustering with CLUSPLOT. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 30(4), 381–392. [CrossRef]

- Rash, J. A., Matsuba, M. K., & Prkachin, K. M. (2011). Gratitude and well--being: Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3(3), 350–369. [CrossRef]

- Reckart, H., Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., & Valois, R. F. (2017). A preliminary study of the origins of early adolescents’ gratitude differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 44–50. [CrossRef]

- Regan, A., Walsh, L. C., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2022). Are some ways of expressing gratitude more beneficial than others? Results from a randomized controlled experiment. Affective Science, 4(1), 72–81. [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P. J. (1987). Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 20, 53–65. [CrossRef]

- Schnall, S., Roper, J., & Fessler, D. M. T. (2010). Elevation leads to altruistic behavior. Psychological Science, 21(3), 315–320. http://doi.org/10.1177/0956797609359882.

- Seligman, M. E., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. [CrossRef]

- Shin, L. J., Armenta, C. N., Kamble, S. V., Chang, S.-L., Wu, H.-Y., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2020). Gratitude in collectivist and individualist cultures. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(5), 598–604. [CrossRef]

- Shin, L. J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2017). Increasing well-being in independent and interdependent cultures. In S. Donaldson & M. Rao (Eds.), Scientific advances in positive psychology (1st ed., pp. 11-36). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/scientific-advances-in-positive-psychology-9781440834806/.

- Soto, C. J., & John, O. P. (2017). Short and extra-short forms of the Big Five Inventory–2: The BFI-2-S and BFI- 2-XS. Journal of Research in Personality, 68, 69-81.

- Szcześniak, M., Rodzeń, W., Malinowska, A., & Kroplewski, Z. (2020). Big five personality traits and gratitude: The role of emotional intelligence. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 977–988. [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J. P. (Ed.). (2012). Self-conscious emotions. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 446–478). The Guilford Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2012-10435-021.

- Toepfer, S. M., Cichy, K., & Peters, P. (2012). Letters of gratitude: Further evidence for author benefits. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(1), 187–201. [CrossRef]

- Tsang, J.-A. (2006). The effects of helper intention on gratitude and indebtedness. Motivation and Emotion, 30(3), 198–204. [CrossRef]

- Tsang, J.-A. (2007). Gratitude for small and large favors: A behavioral test. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(3), 157–167. [CrossRef]

- Vargha, A., Bergman, L. R., & Takács, S. (2016). Performing cluster analysis within a person-oriented context: Some methods for evaluating the quality of Cluster Solutions. Journal for Person-Oriented Research, 2(1–2), 78–86. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, L. C., Armenta, C. N., Itzchakov, G., Fritz, M. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2022c). More than merely positive: The immediate affective and motivational consequences of gratitude. Sustainability, 14(14), 8679. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, L. C., Regan, A., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2022a). The role of actors, targets, and witnesses: Examining gratitude exchanges in a social context. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 17(2), 233–249. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, L. C., Regan, A., Twenge, J. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2022b). What is the optimal way to give thanks? Comparing the effects of gratitude expressed privately, one-to-one via text, or publicly on social media. Affective Science, 4(1), 82–91. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Adele., Nelson-Coffey, S. K., Layous, K., Jacobs Bao, K., Davis, O. S., & Haworth, C. M. (2017). Moderators of wellbeing interventions: Why do some people respond more positively than others? PLOS ONE, 12(11). [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P., Scheer, J., Ovnicek, M., & Kolts, R. (2006). The debt of gratitude: Dissociating Gratitude and indebtedness. Cognition & Emotion, 20(2), 217–241. [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Gillett, R., Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2008a). The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(4), 854–871. [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Stewart, N., & Joseph, S. (2008b). Conceptualizing gratitude and appreciation as a unitary personality trait. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(3), 621–632. [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, K. (2016). Application of K-means clustering in psychological studies. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 12(2), 87–100. [CrossRef]

| Two-Cluster Solution | Three-Cluster Solution | ||||

| Backfired | Uplifted | Backfired |

Mixed Feelings |

Buffered | |

| n = | 222 | 265 | 185 | 188 | 114 |

| Positive Affect | -0.60 | 0.51 | -0.69 | 0.64 | 0.07 |

| Elevation | -0.58 | 0.48 | -0.72 | 0.68 | 0.06 |

| Negative Affect | 0.61 | -0.51 | 0.66 | -0.03 | -1.02 |

| Self-Conscious Affect | 0.32 | -0.27 | 0.20 | 0.45 | -1.06 |

| Two-Cluster Solution | Three-Cluster Solution | ||||

| Backfired | Uplifted | Backfired |

Mixed Feelings |

Buffered | |

| n = | 222 | 265 | 185 | 188 | 114 |

| Positive Affect | -0.60 | 0.51 | -0.69 | 0.64 | 0.07 |

| Elevation | -0.58 | 0.48 | -0.72 | 0.68 | 0.06 |

| Negative Affect | 0.61 | -0.51 | 0.66 | -0.03 | -1.02 |

| Self-Conscious Affect | 0.32 | -0.27 | 0.20 | 0.45 | -1.06 |

| r Indebtedness | ||

| Items | T0 | T1 |

| Positive Affect | ||

| Happy | -.01 | .05 |

| Pleased | .06 | .14 |

| Joyful | .09 | .07 |

| Enjoyment | .09 | .06 |

| Elevation | ||

| Moved | .20 | .29 |

| Uplifted | .09 | .24 |

| Optimistic about humanity | .13 | .21 |

| A warm feeling in your chest | .14 | .27 |

| A desire to help others | .12 | .19 |

| A desire to become a better person | .06 | .12 |

| Negative Affect | ||

| Unhappy | .23 | .07 |

| Worried/Anxious | .14 | -.06 |

| Angry/Hostile | .25 | .08 |

| Frustrated | .26 | .01 |

| Depressed/Blue | .13 | .05 |

| Self-Conscious Affect | ||

| Indebted | 1 | 1 |

| Guilty | .27 | .28 |

| Embarrassed | .32 | .28 |

| Uncomfortable | .21 | .15 |

| Ashamed | .38 | .29 |

| Backfired | Mixed Feelings | Buffered | |

| Coding Theme | (A) | (B) | (C) |

| Writer effort | |||

| Mean | 2.99 | 3.43 | 2.95 |

| Standard deviation | 1.31 | 1.06 | 1.10 |

| Pairwise comparison | - | AC | - |

| Level of detail | |||

| Mean | 2.63 | 3.13 | 2.62 |

| Standard deviation | 1.18 | 1.00 | 1.06 |

| Pairwise comparison | - | AC | - |

| Heartfelt sincerity | |||

| Mean | 3.14 | 3.53 | 3.18 |

| Standard deviation | 1.20 | 0.88 | 0.97 |

| Pairwise comparison | - | A | - |

| Reflection depth | |||

| Mean | 2.69 | 3.17 | 2.68 |

| Standard deviation | 1.22 | 1.07 | 1.12 |

| Pairwise comparison | - | AC | - |

| Genuineness | |||

| Mean | 3.10 | 3.54 | 3.07 |

| Standard deviation | 1.25 | 0.94 | 1.02 |

| Pairwise comparison | - | AC | - |

| Superficiality | |||

| Mean | 2.34 | 1.84 | 2.16 |

| Standard deviation | 1.17 | 0.80 | 0.99 |

| Pairwise comparison | B | - | - |

| Benefactor Effort | |||

| Mean | 2.68 | 2.98 | 2.48 |

| Standard deviation | 1.15 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| Pairwise comparison | - | C | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).