Submitted:

04 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Underpinning

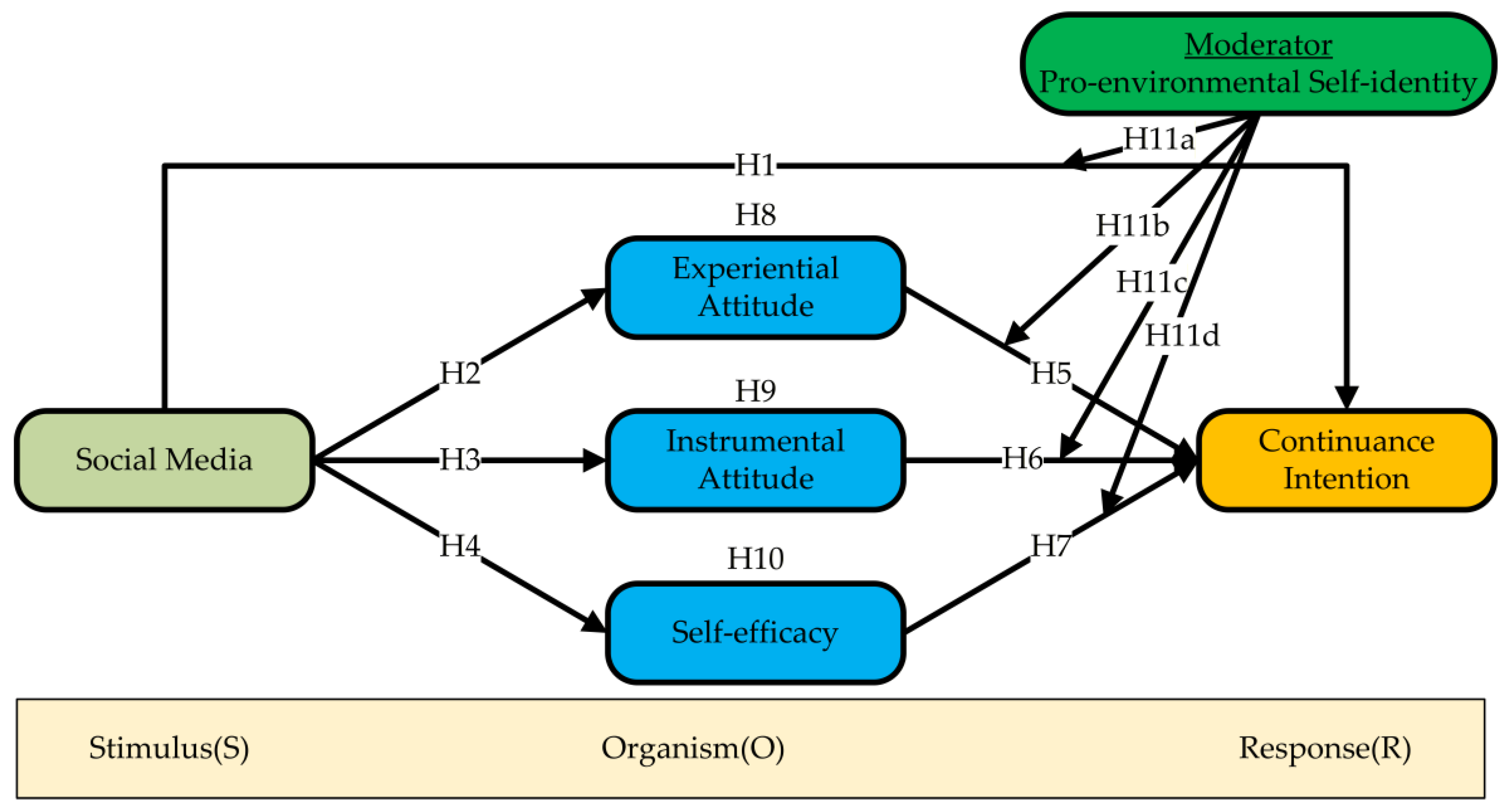

2.1. Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O-R) Theory

3. Literature and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Social Media and Continuance Intention

3.2. Social Media and Experiential Attitude, Instrumental Attitude

3.3. Social Media and Self-Efficacy

3.4. Experiential Attitude, Instrumental Attitude, and Continuance Intention

3.5. Self-Efficacy and Continuance Intention

3.6. Pro-Environmental Self-Identity (PESI)

4. Research Method

4.1. Measures

4.2. Data Collection

5. Data Analysis

5.1. Common Method Variance

5.2. Reliability and Validity

5.3. Discriminant Validity

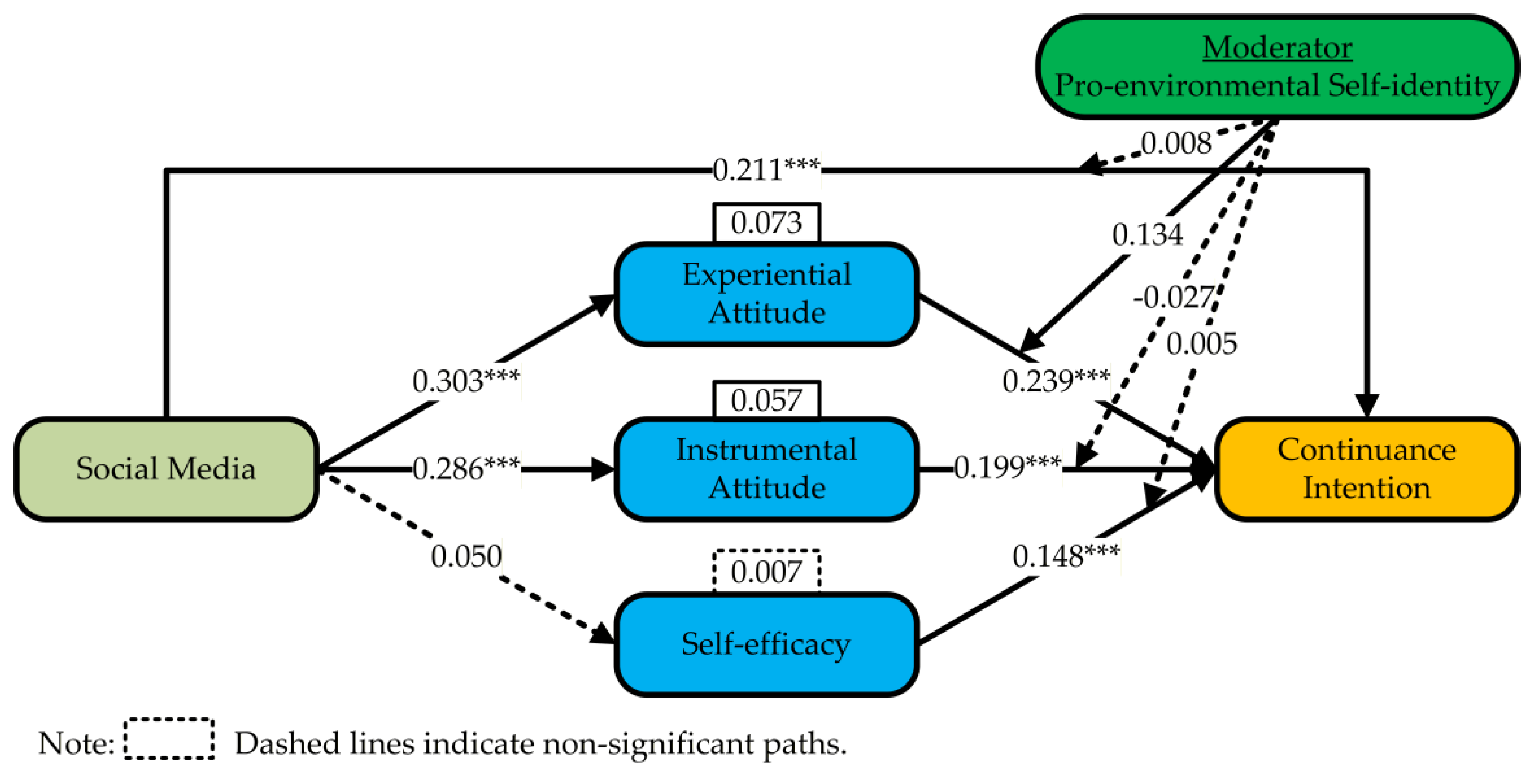

5.4. Hypotheses Testing

6. Discussion

7. Conclusion

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

7.2. Managerial Implications

7.3. Research Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| SOR | Stimulus–Organism–Response |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AVs | Autonomous Vehicles |

| IDC | International Data Corporation |

| CLF | Common Latent Factor |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| SM | Social Media |

| EA | Experiential Attitude |

| IA | Instrumental Attitude |

| SE | Self-efficacy |

| PESI | Pro-Environmental Self-Identity |

| CI | Continuance Intention |

| HTMT | Heterotrait-Monotrait |

Appendix A

| Construct | Item | Content | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media (SM) |

SM1 | I have encountered information about autonomous taxis shared by individuals within my social media network. | [120] |

| SM2 | I have read posts or reports recommending autonomous taxis on social media platforms. | ||

| SM3 | I have come across news or discussions about autonomous taxis on popular social media platforms or forums. | ||

| Experiential Attitude (EA) |

In the next two weeks, my continuance intention to use autonomous taxis would be: | [25] | |

| EA1 | Bad - Good | ||

| EA2 | Stressful - Relaxing | ||

| EA3 | Unpleasant - Pleasant | ||

| EA4 | Boring - Interesting | ||

| Instrumental Attitude (IA) |

IA1 | Unwise - Wise | |

| IA2 | Harmful - Beneficial | ||

| IA3 | Useless - Useful | ||

| IA4 | Wrong - Right | ||

| Self-efficacy (SE) |

SE1 | I believe I am capable of mastering the skills required to use an autonomous taxi. | [110] |

| SE2 | I believe I can effectively issue commands to an autonomous taxi according to system instructions. | ||

| SE3 | I believe I am able to successfully complete a trip using an autonomous taxi. | ||

| SE4 | Overall, I believe I am capable of using an autonomous taxi. | ||

| Pro-environmental Self-identity (PESI) |

PESI1 | I consider myself an environmentally friendly consumer. | [29,105] |

| PESI2 | I regard myself as someone who is very concerned about environmental issues. | ||

| PESI3 | I would feel uncomfortable if others considered me to have an environmentally friendly lifestyle. (reverse-coded) | ||

| PESI4 | I would not want my family or friends to think of me as someone who cares about environmental issues. (reverse-coded) | ||

| Continuance Intention (CI) |

CI1 | I intend to continue using autonomous taxi services rather than discontinue them. | [119] |

| CI2 | I expect to frequently use autonomous taxi services in the future. | ||

| CI3 | If possible, I would prefer to regularly use autonomous taxi services. | ||

References

- Narayanan, S.; Chaniotakis, E.; Antoniou, C. Shared autonomous vehicle services: A comprehensive review. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2020, 111, 255–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepardson, D. Uber, Waymo launch autonomous ride-hailing service in Atlanta. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/uber-waymo-launch-autonomous-ride-hailing-service-atlanta-2025-06-24/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Miller, C. Amazon's Self-Driving Zoox Vehicles Begin Ride-Hailing Service in Las Vegas. Available online: https://www.caranddriver.com/news/a66068584/amazon-zoox-autonomous-ride-hailing-las-vegas/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Wei, W.; Sun, J.; Miao, W.; Chen, T.; Sun, H.; Lin, S.; Gu, C. Using the Extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology to explore how to increase users’ intention to take a robotaxi. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T. Chinese robotaxis are gunning for global domination tesla joins the robotaxi race, but Chinese AV companies are ahead. Available online: https://spectrum.ieee.org/tesla-robotaxi-chinese-competitors (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Chang, A.; Jeng, V.; Delaney, M.; Keung, R. Global Technology: China’s Robotaxi market - the road to commercialization. Available online: https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/goldman-sachs-research/chinas-robotaxi-market (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- White, E. China vies for lead in the race to self-driving vehicles. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/41bac535-9237-444b-ba56-a9cf38c11b3f (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Leonard, J.J.; Mindell, D.A.; Stayton, E.L. Autonomous vehicles, mobility, and employment policy: the roads ahead. Available online: https://workofthefuture.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2020-07/WotF-2020-Research-Brief-Leonard-Mindell-Stayton.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Yigitcanlar, T. Autonomous Urban Mobility: Understanding Adoption Parameters, Perceptions, Perspectives; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.; Md Nordin, S.; bin Bahruddin, M.A.; Ali, M. How trust can drive forward the user acceptance to the technology? In-vehicle technology for autonomous vehicle. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2018, 118, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, C.; Oberfeld, D.; Hoffmann, C.; Weismüller, D.; Hecht, H. User acceptance of automated public transport: Valence of an autonomous minibus experience. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 2020, 70, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajunen, T.; Sullman, M.J.M. Attitudes Toward Four Levels of Self-Driving Technology Among Elderly Drivers. Frontiers in Psychology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Yin, T.; Zheng, K. They May Not Work! An evaluation of eleven sentiment analysis tools on seven social media datasets. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2022, 132, 104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Tsou, M.-H.; Nara, A.; Cassels, S.; Dodge, S. Developing a social sensing index for monitoring place-oriented mental health issues using social media (twitter) data. Urban Informatics 2024, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (CNNIC), C.I.N.I.C. China has over 1.12 billion internet users, boosting prowess in culture, AI. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202507/21/content_WS687dd259c6d0868f4e8f4501.html (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Wu, J.; Kim, S.-T. An integrated SOR and SCT model approach to exploring chinese public perception of autonomous vehicles. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 21727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, J.H.C.G.; Wang, S.; Peng, Z.; Zhuge, C. Attention and attitudes of Chinese social media users towards autonomous vehicles: sentimental, statistical and spatiotemporal perspectives. Transportation 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, K. Exploring the implications of autonomous vehicles: a comprehensive review. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions 2022, 7, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolinário-Hagen, J.; Fritsche, L.; Wopperer, J.; Wals, F.; Harrer, M.; Lehr, D.; Ebert, D.D.; Salewski, C. Investigating the Persuasive Effects of Testimonials on the Acceptance of Digital Stress Management Trainings Among University Students and Underlying Mechanisms: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Frontiers in Psychology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.H.; Chang, Y.P. Investigating consumer attitude and intention toward free trials of technology-based services. Computers in Human Behavior 2014, 30, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach; Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- La Barbera, F.; Ajzen, I. Instrumental vs. experiential attitudes in the theory of planned behaviour: two studies on intention to perform a recommended amount of physical activity. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2024, 22, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, A.L.; Maupin, D.J.; Sena, M.P.; Zhuang, Y. The role of ease of use, usefulness and attitude in the prediction of World Wide Web usage. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1998 ACM SIGCPR conference on Computer personnel research, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, P.; Rise, J.; Sutton, S.; Røysamb, E. Perceived difficulty in the theory of planned behaviour: perceived behavioural control or affective attitude? Br J Soc Psychol 2005, 44, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEachan, R.; Taylor, N.; Harrison, R.; Lawton, R.; Gardner, P.; Conner, M. Meta-Analysis of the Reasoned Action Approach (RAA) to Understanding Health Behaviors. Ann Behav Med 2016, 50, 592–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. 1986.https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1985-98423-000.

- Belk, R.W. Attachment to Possessions. In Place Attachment, Altman, I., Low, S.M., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1992; pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, P.; Shepherd, R. Self-Identity and the Theory of Planned Behavior: Assesing the Role of Identification with "Green Consumerism". Social Psychology Quarterly 1992, 55, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Gong, Y.; Liu, S. Self-image motives for electric vehicle adoption: Evidence from China. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2022, 109, 103383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z. Consumer preferences for battery electric vehicles: A choice experimental survey in China. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2020, 78, 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bodin, J. Advances in consumer electric vehicle adoption research: A review and research agenda. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2015, 34, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermody, J.; Koenig-Lewis, N.; Zhao, A.L.; Hanmer-Lloyd, S. Appraising the influence of pro-environmental self-identity on sustainable consumption buying and curtailment in emerging markets: Evidence from China and Poland. Journal of Business Research 2018, 86, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Bohlen, G.M. Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. Journal of Business Research 2003, 56, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Zhou, L. Elucidation of user autonomous driving system preference mechanisms under the extension of internal and external factors. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 30060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, J.; Zhou, L.; Yang, C. Research on the Behavior Influence Mechanism of Users’ Continuous Usage of Autonomous Driving Systems Based on the Extended Technology Acceptance Model and External Factors. Sustainability 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International, S.A.E. Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/j3016_202104/ (accessed on.

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. The basic emotional impact of environments. Percept Mot Skills 1974, 38, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Grebinevych, O.; Roubaud, D. Green factors stimulating the purchase intention of innovative luxury organic beauty products: Implications for sustainable development. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 301, 113899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanuddin, K.A.; Handayani, P.W. User continuance intention to use social commerce livestreaming shopping based on stimulus-organism-response theory. Cogent Business & Management 2025, 12, 2479178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liangyu, C.; Chang, J.; Cheng, T.; Jin, C.; Gu, C. How Multilingual Services Affect Foreign Users' Behavior Intention to Use Robotaxi: An Empirical Study Using Sem and Fsqca. Available at SSRN 534 7552.

- Chou, S.-Y.; Shen, G.C.; Chiu, H.-C.; Chou, Y.-T. Multichannel service providers' strategy: Understanding customers' switching and free-riding behavior. Journal of Business Research 2016, 69, 2226–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cho, H.-K.; Kim, M.-Y. A Study on Factors Affecting the Continuance Usage Intention of Social Robots with Episodic Memory: A Stimulus–Organism–Response Perspective. Applied Sciences 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus-Organism-Response Reconsidered: An Evolutionary Step in Modeling (Consumer) Behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R.; Roubaud, D.; Grebinevych, O. Sustainable consumption behaviour: Mediating role of pro-environment self-identity, attitude, and moderation role of environmental protection emotion. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 347, 119106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R. Organic green purchasing: Moderation of environmental protection emotion and price sensitivity. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 368, 133113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A. Exploring intention to enroll university using an extended stimulus-organism-response model. Academy of Strategic Management Journal 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, T.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, H.; Qian, S. Continuance intention toward VR games of intangible cultural heritage: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. Virtual Reality 2024, 28, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, J. Modelling the acceptance of fully autonomous vehicles: A media-based perception and adoption model. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 2020, 73, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Baig, F.; Li, X. Media Influence, Trust, and the Public Adoption of Automated Vehicles. IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine 2022, 14, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tao, D.; Qu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, H. Automated vehicle acceptance in China: Social influence and initial trust are key determinants. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2020, 112, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Jing Yi, T.; Hanifah, H.; Nikbin, D.; Shojaei, S.A. Examining autonomous vehicle adoption: A media-based perception and adoption model. Travel Behaviour and Society 2025, 40, 101041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafar, Z. The Positive and Negative Aspects of Social media platforms in many Fields, Academic and Non-academic, all over the World in the Digital Era: A Critical Review. JOURNAL OF DIGITAL LEARNING AND DISTANCE EDUCATION 2024, 2, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasri, M.; Vij, A. The potential impact of media commentary and social influence on consumer preferences for driverless cars. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2021, 127, 103132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Ashaduzzaman, M. How do electronic word of mouth practices contribute to mobile banking adoption? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 52, 101920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Du, H.; Wu, J. Media and Trust Influence Consumers' Acceptance of Self-driving Cars. In Proceedings of the 2022 10th International Conference on Traffic and Logistic Engineering (ICTLE), 12-14 Aug. 2022; 2022; pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anania, E.C.; Rice, S.; Walters, N.W.; Pierce, M.; Winter, S.R.; Milner, M.N. The effects of positive and negative information on consumers’ willingness to ride in a driverless vehicle. Transport Policy 2018, 72, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinski, L.; Etzrodt, K.; Engesser, S. Undifferentiated optimism and scandalized accidents: the media coverage of autonomous driving in Germany. Journal of Science Communication 2021, 20, A02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Xie, Y.; Ma, M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Su, B.; Xu, W.; Li, T. Recent surge in public interest in transportation: Sentiment analysis of Baidu Apollo Go using Weibo data. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.10088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.; Spangenberg, E.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the Hedonic and Utilitarian Dimensions of Consumer Attitude. Journal of Marketing Research - J MARKET RES-CHICAGO 2003, 40, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crites, S.; Fabrigar, L.; Petty, R. Measuring the Affective and Cognitive Properties of Attitudes: Conceptual and Methodological Issues. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 1994, 20, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Petty, R.E. The Role of the Affective and Cognitive Bases of Attitudes in Susceptibility to Affectively and Cognitively Based Persuasion. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 1999, 25, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock, G.; Maio, G.R. Chapter Two - Inter-individual differences in attitude content: Cognition, affect, and attitudes. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Olson, J.M., Ed.; Academic Press, 2019; Volume 59, pp. 53–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ahtola, O.T. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes. Marketing Letters 1991, 2, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Driver, B. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Leisure Choice. Journal of Leisure Research 1992, 24, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. Experiential and instrumental attitudes: Interaction effect of attitude and subjective norm on recycling intention. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2017, 50, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Frieze, I.; Tang, C.S. Understanding adolescent peer sexual harassment and abuse: using the theory of planned behavior. Sex Abuse 2010, 22, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Foxall, G.R.; Pallister, J. Beyond the Intention–Behaviour Mythology: An Integrated Model of Recycling. Marketing Theory 2002, 2, 29–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Yu, A. The role of perceived effectiveness of policy measures in predicting recycling behaviour in Hong Kong. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2014, 83, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, R.; Conner, M.; McEachan, R. Desire or reason: predicting health behaviors from affective and cognitive attitudes. Health Psychol 2009, 28, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, D.; Le, T.; Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, T. The Impact Of Social Media Marketing On Cognitive And Affective Destination Image Toward Intention To Visit Cultural Destinations In Vietnam. 2025; pp. 300–315. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-B.; Kim, D.-Y.; Wise, K. The effect of searching and surfing on recognition of destination images on Facebook pages. Computers in Human Behavior 2014, 30, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Worth Publishers: 1997; https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=eJ-PN9g_o-EC.

- Compeau, D.R.; Higgins, C.A. Computer Self-Efficacy: Development of a Measure and Initial Test. MIS Quarterly 1995, 19, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology1. Management Information Systems Quarterly 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abang Othman, D.N.; Abdul Gani, A.; Ahmad, N.F. Social media information and hotel selection: Integration of TAM and IAM models. Journal of Tourism, Hospitality & Culinary Arts (JTHCA) 2017, 9, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Zhu, G.; Zheng, J. Why travelers trust and accept self-driving cars: An empirical study. Travel Behaviour and Society 2021, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, D.; Lim, R. The mediating effects of habit on continuance intention. International Journal of Information Management 2017, 37, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Iranmanesh, M.; Kuppusamy, M.; Ganesan, Y.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Senali, M.G. Determinants of continuance intention to use gamification applications for task management: an extension of technology continuance theory. The Electronic Library 2023, 41, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T. Psychological factors affecting potential users’ intention to use autonomous vehicles. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0282915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; He, M.; Xing, C. Public Acceptance of Autonomous Vehicles in China. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2024, 40, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, T. Recent Trends in the Public Acceptance of Autonomous Vehicles: A Review. Vehicles 2025, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, H. “It’s Up to Me Whether I Do—Or Don’t—Watch Deepfakes”: Deepfakes and Behavioral Intention. SAGE Open 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlin, D.L.A. Comparing Automated Shared Taxis and Conventional Bus Transit for a Small City. Journal of Public Transportation 2017, 20, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, S. Competition between autonomous and traditional ride-hailing platforms: Market equilibrium and technology transfer. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2024, 165, 104728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanbonmatsu, D.M.; Strayer, D.L.; Yu, Z.; Biondi, F.; Cooper, J.M. Cognitive underpinnings of beliefs and confidence in beliefs about fully automated vehicles. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 2018, 55, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.; Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Organizational Management. Academy of Management Review 1989, 14, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-H.; Chiu, C.-M. Internet self-efficacy and electronic service acceptance. Decision Support Systems 2004, 38, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ye, P.; Tan, J. Exploring college students’ continuance learning intention in data analysis technology courses: the moderating role of self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, I.B.; Hwang, K.-H. Exploring the Influence of Prompt Self-Efficacy: Accurate and Customized Information, Perceived Ease of Use, Satisfaction, and Continuance Intention to Use ChatGPT. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Saini, J.R. On the Role of Teachers’ Acceptance, Continuance Intention and Self-Efficacy in the Use of Digital Technologies in Teaching Practices. Journal of Further and Higher Education 2022, 46, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.G.; Hamari, J.; Kesharwani, A.; Tak, P. Understanding continuance intention to play online games: roles of self-expressiveness, self-congruity, self-efficacy, and perceived risk. Behaviour & Information Technology 2022, 41, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Giménez, D.; Rolo-González, G.; Suárez, E.; Muinos, G. The Influence of Environmental Self-Identity on the Relationship between Consumer Identities and Frugal Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effron, Daniel A. Beyond “being good frees us to be bad”: Moral self-licensing and the fabrication of moral credentials. In Cheating, Corruption, and Concealment: The Roots of Dishonesty, Prooijen, J.-W.v., Lange, P.A.M.v., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2016; pp. 33–54. [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H.; Yan, L.; Guo, R.; Saeed, A.; Ashraf, B.N. The Defining Role of Environmental Self-Identity among Consumption Values and Behavioral Intention to Consume Organic Food. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O'Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balundė, A.; Jovarauskaitė, L.; Poškus, M.S. Exploring the Relationship Between Connectedness With Nature, Environmental Identity, and Environmental Self-Identity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sage Open 2019, 9, 2158244019841925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, C.; Gollwitzer, P.M.; Oettingen, G. A green paradox: Validating green choices has ironic effects on behavior, cognition, and perception. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2014, 50, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W.P.; Khazian, A.M.; Zaleski, A.C. Using normative social influence to promote conservation among hotel guests. Social Influence 2008, 3, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.H. The Role and the Person. American Journal of Sociology 1978, 84, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, P.J. The Self: Measurement Requirements from an Interactionist Perspective. Social Psychology Quarterly 1980, 43, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.J.; Kerr, G.N.; Moore, K. Attitudes and intentions towards purchasing GM food. Journal of Economic Psychology 2002, 23, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Opotow, S. Identity and the Natural Environment: The Psychological Significance of Nature; The MIT Press, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Tabanico, J. Self, Identity, and the Natural Environment: Exploring Implicit Connections With Nature. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2007, 37, 1219–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Buscicchio, G.; Catellani, P. Proenvironmental self identity as a moderator of psychosocial predictors in the purchase of sustainable clothing. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 23968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stets, J.; Biga, C. Bringing Identity Theory Into Environmental Sociology. Sociological Theory 2003, 21, 398–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermody, J.; Hanmer-Lloyd, S.; Koenig-Lewis, N.; Zhao, A.L. Advancing sustainable consumption in the UK and China: the mediating effect of pro-environmental self-identity. Journal of Marketing Management 2015, 31, 1472–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, Y.; Paladino, A.; Margetts, E.A. Environmentalist identity and environmental striving. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2014, 38, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Review and Avenues for Further Research. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. I Am What I Am, by Looking Past the Present: The Influence of Biospheric Values and Past Behavior on Environmental Self-Identity. Environment and Behavior 2013, 46, 626–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C.; Beckmann, S.C.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Moons, I.; Gwozdz, W. A self-identity based model of electric car adoption intention: A cross-cultural comparative study. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2015, 42, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skippon, S.; Garwood, M. Responses to battery electric vehicles: UK consumer attitudes and attributions of symbolic meaning following direct experience to reduce psychological distance. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2011, 16, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Moons, I. Personal Values, Green Self-identity and Electric Car Adoption. Ecological Economics 2017, 140, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, S.; Khan, S. Autonomous vehicles adoption motivations and tourist pro-environmental behavior: the mediating role of tourists’ green self-image. Tourism Review 2024, 80, 664–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Wu, Q.; Bi, C.; Deng, Y.; Hu, Q. The relationship between climate change anxiety and pro-environmental behavior in adolescents: the mediating role of future self-continuity and the moderating role of green self-efficacy. BMC Psychology 2024, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: an expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.T.T.; Corner, J. The impact of communication channels on mobile banking adoption. International Journal of Bank Marketing 2016, 34, 78–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govorova, A.V. History and Paradoxes of the Chinese Car Market: Eastern Strategies and the Asian Regulator. Studies on Russian Economic Development 2023, 34, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Li, G.; Chen, J.; Long, Y.; Chen, T.; Chen, L.; Xia, Q. The adaptability and challenges of autonomous vehicles to pedestrians in urban China. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2020, 145, 105692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Wang, J. Autonomous Driving Capabilities Assessment, 2024. Available online: https://my.idc.com/getdoc.jsp?containerId=CHE50962524 (accessed on May 2024).

- Shen, M.; Yu, L.; Xu, J.; Sang, Z.; Li, R.; Yuan, X. Shaping the Future of Urban Mobility: Insights into Autonomous Vehicle Acceptance in Shanghai Through TAM and Perceived Risk Analysis. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heineke, K.; Kellner, M.; Smith, A.-S.; Rebmann, M. Are consumers ready for remote driving? Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/features/mckinsey-center-for-future-mobility/mckinsey-on-urban-mobility/are-consumers-ready-for-remote-driving (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Zhao, H. Social Media Statistics for China [Updated 2025]. Available online: https://www.meltwater.com/en/blog/social-media-statistics-china (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Pick, J.B.; Ren, F.; Sarkar, A. Social media access and purposeful use in China: Geospatial patterns and socioeconomic and COVID-19 influences. Telecommunications Policy 2025, 49, 103002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Page, M.; Brunsveld, N. Essentials of Business Research Methods; 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Babin, B.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis : Pearson New International Edition. 2013, 740. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: A Comment. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: a comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Montoya, A.K.; Rockwood, N.J. The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ) 2017, 25, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regorz, A. PROCESS Model 14 moderated mediation. 2021, doi:https://www.regorz-statistik.de/en/process_model_14_moderated_mediation.html.

- Hasan, M.; Sohail, M.S. The Influence of Social Media Marketing on Consumers’ Purchase Decision: Investigating the Effects of Local and Nonlocal Brands. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 2020, 33, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, D.L.; Carlson, J.; Filieri, R.; Jacobson, J.; Jain, V.; Karjaluoto, H.; Kefi, H.; Krishen, A.S.; et al. Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. International Journal of Information Management 2021, 59, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, X.K.; Lee, V.H.; Loh, X.M.; Tan, G.W.; Ooi, K.B.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The Dark Side of Mobile Learning via Social Media: How Bad Can It Get? Inf Syst Front 2022, 24, 1887–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirbabaie, M.; Stieglitz, S.; Marx, J. Negative Word of Mouth On Social Media: A Case Study of Deutsche Bahn’s Accountability Management. Schmalenbach Journal of Business Research 2023, 75, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Zheng, J.; Du, H.; Hou, J. Insights into Autonomous Vehicles Aversion: Unveiling the Ripple Effect of Negative Media on Perceived Risk, Anxiety, and Negative WOM. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2025, 41, 8684–8701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.-A.; Chrysochou, P.; Mitkidis, P. The paradox of technology: Negativity bias in consumer adoption of innovative technologies. Psychology & Marketing 2023, 40, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; So, K.K.F.; Hudson, S. Inside the sharing economy: Understanding consumer motivations behind the adoption of mobile applications. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Timko, C. Correspondence Between Health Attitudes and Behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology - BASIC APPL SOC PSYCHOL 1986, 7, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, R.; Conner, M.; Parker, D. Beyond cognition: predicting health risk behaviors from instrumental and affective beliefs. Health Psychol 2007, 26, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udall, A.M.; de Groot, J.I.M.; de Jong, S.B.; Shankar, A. How do I see myself? A systematic review of identities in pro-environmental behaviour research. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 2020, 19, 108–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Catellani, P.; Teresa Del, G.; Cicia, G. Why Do Consumers Intend to Purchase Natural Food? Integrating Theory of Planned Behavior, Value-Belief-Norm Theory, and Trust. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, J.; Hitosug, M.; Wang, Z. Traffic safety and public health in China – Past knowledge, current status, and future directions. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2023, 192, 107272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B. Using an evidence-based safety approach to develop China’s urban safety strategies for the improvement of urban safety: From an accident prevention perspective. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2022, 163, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITF. Lost in Transmission: Communicating for Safe Automated Vehicle Interactions in Cities. Available online: https://www.itf-oecd.org/communicating-safe-automated-vehicle-cities (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Mayfield, A. What is social media. 2008, doi:https://www.antonymayfield.com/2008/03/22/what-is-social-media-ebook-on-mashable/.

- Yuan, Y.-P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Cham, T.-H.; Ooi, K.-B.; Aw, E.C.-X.; Currie, W. Government Digital Transformation: Understanding the Role of Government Social Media. Government Information Quarterly 2023, 40, 101775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Park, S.-D. Decoding Green Consumption Behavior Among Chinese Consumers: Insights from Machine Learning Models on Emotional and Social Influences. Behavioral Sciences 2025, 15, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander Rangel, V.; Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Hanifah, H.; Nikbin, D. Understanding autonomous vehicle adoption intentions in Malaysia through behavioral reasoning theory. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 2024, 107, 1214–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Items | Frequency | Percentage% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 428 | 52.4 |

| Female | 389 | 47.6 | |

| Age | Under25 | 125 | 15.3 |

| 26-35 | 117 | 14.3 | |

| 36-45 | 209 | 25.6 | |

| 46-55 | 269 | 32.9 | |

| Over 55 | 97 | 11.9 | |

| Education | High School or Below | 52 | 6.4 |

| Associate Degree | 258 | 31.6 | |

| Bachelor's Degree | 468 | 57.3 | |

| Master's Degree or Above | 39 | 4.8 | |

| Occupation | Government employee | 36 | 4.4 |

| Private employee | 287 | 35.1 | |

| Own business | 261 | 31.9 | |

| Others | 125 | 15.3 | |

| Income status (monthly) | Below CNY ¥5000 | 144 | 17.6 |

| CNY ¥5001-CNY ¥8000 | 265 | 32.4 | |

| CNY ¥8001-CNY ¥11000 | 189 | 23.1 | |

| CNY ¥11001-CNY ¥14000 | 147 | 18 | |

| Above CNY ¥14001 | 72 | 8.8 |

| Model | x²/df | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | SMRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLF factor | 1.480 | 0.990 | 0.988 | 0.990 | 0.024 | 0.026 |

| 6 factor | 1.561 | 0.988 | 0.985 | 0.988 | 0.026 | 0.029 |

| 5 factor | 4.569 | 0.920 | 0.920 | 0.920 | 0.066 | 0.061 |

| 4 factor | 8.709 | 0.823 | 0.800 | 0.822 | 0.097 | 0.078 |

| 3 factor | 15.399 | 0.662 | 0.626 | 0.661 | 0.133 | 0.107 |

| 2 factor | 21.332 | 0.516 | 0.471 | 0.515 | 0.158 | 0.126 |

| 1 factor | 22.790 | 0.476 | 0.433 | 0.475 | 0.163 | 0.129 |

| Criteria | Acceptable <5 |

Acceptable >0.8 |

Acceptable >0.8 |

Acceptable >0.8 |

Acceptable <0.08 |

Acceptable <0.08 |

| Ideally <3 | Ideally >0.9 | Ideally >0.9 | Ideally >0.9 |

| Variables | Items | Loadings | CR | AVE | Cronbach's alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media (SM) |

SM1 | 0.608 | .761 | .517 | .755 |

| SM2 | 0.779 | ||||

| SM3 | 0.758 | ||||

| Experiential Attitude (EA) |

EA1 | 0.667 | .839 | .567 | .838 |

| EA2 | 0.787 | ||||

| EA3 | 0.746 | ||||

| EA4 | 0.804 | ||||

| Instrumental Attitude (IA) |

IA1 | 0.872 | .876 | .642 | .871 |

| IA2 | 0.734 | ||||

| IA3 | 0.909 | ||||

| IA4 | 0.666 | ||||

| Self-efficacy (SE) |

SE1 | 0.727 | .873 | .638 | .866 |

| SE2 | 0.931 | ||||

| SE3 | 0.858 | ||||

| SE4 | 0.647 | ||||

| Pro-environmental Self-identity (PESI) |

PESI1 | 0.630 | .873 | .637 | .867 |

| PESI2 | 0.891 | ||||

| PESI3 | 0.745 | ||||

| PESI4 | 0.895 | ||||

| Continuance Intention (CI) |

CI1 | 0.754 | .786 | .555 | .771 |

| CI2 | 0.602 | ||||

| CI3 | 0.857 |

| Constructs | SM | EA | IA | SE | PESI | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media (SM) |

0.719 | 0.358 | 0.321 | 0.053 | 0.151 | 0.439 |

| Experiential Attitude (EA) |

0.357 | 0.753 | 0.582 | 0.344 | 0.469 | 0.558 |

| Instrumental Attitude (IA) |

0.319 | 0.580 | 0.801 | 0.412 | 0.335 | 0.506 |

| Self-efficacy (SE) |

0.052 | 0.343 | 0.410 | 0.799 | 0.258 | 0.382 |

| Pro-environmental Self-identity (PESI) |

0.150 | 0.467 | 0.333 | 0.256 | 0.798 | 0.306 |

| Continuance Intention (CI) |

0.436 | 0.554 | 0.502 | 0.379 | 0.303 | 0.745 |

| Path | Coefficients | S.E. | t | p | 95% CILL | 95% CIUL | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects | |||||||

| SM→CI | 0.211 | 0.031 | 6.831 | 0.000 | 0.151 | 0.272 | Yes |

| SM→EA | 0.303 | 0.035 | 8.670 | 0.000 | 0.235 | 0.372 | Yes |

| SM→IA | 0.286 | 0.034 | 8.265 | 0.000 | 0.218 | 0.354 | Yes |

| SM→SE | 0.050 | 0.036 | 1.374 | 0.170 | -0.021 | 0.122 | NO |

| EA→CI | 0.239 | 0.035 | 6.839 | 0.000 | 0.171 | 0.308 | Yes |

| IA→CI | 0.199 | 0.035 | 5.713 | 0.000 | 0.131 | 0.267 | Yes |

| SE→CI | 0.148 | 0.031 | 4.866 | 0.000 | 0.089 | 0.208 | Yes |

| Mediating effects | |||||||

| SM→EA→CI | 0.073 | 0.014 | 0.046 | 0.103 | Yes | ||

| SM→IA→CI | 0.057 | 0.013 | 0.034 | 0.084 | Yes | ||

| SM→SE→CI | 0.007 | 0.006 | -0.003 | 0.019 | NO | ||

| Moderating effects | |||||||

| SM*PESI→CI | 0.008 | 0.031 | 0.267 | 0.790 | -0.052 | 0.069 | NO |

| EA*PESI→CI | 0.134 | 0.036 | 3.696 | 0.000 | 0.063 | 0.204 | Yes |

| IA*PESI→CI | -0.027 | 0.034 | -0.782 | 0.435 | -0.093 | 0.040 | NO |

| SE*PESI→CI | 0.005 | 0.030 | 0.179 | 0.858 | -0.054 | 0.065 | NO |

| Mediator | Clusters | Coefficients | S.E. | 95% CILL | 95% CIUL | Index of moderated mediation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | 95% CI | ||||||

| EA | High PESI | 0.114 | 0.022 | 0.074 | 0.160 | 0.041 | [0.018,0.067] |

| Low PESI | 0.031 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.064 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).