The Breeding Dilemma: Biology vs Prediction?

Plant breeding is fundamentally about identifying and assembling genetic signatures that create the most favorable trait combinations for improved performance in a target population and environmental conditions. What started as direct phenotypic selection has evolved significantly over time, facilitated by various technological advancements, including high-resolution sequencing and computational advances, phenomics and envirotyping capabilities, gene discovery strategies, and prediction models, ranging from linear mixed models to powerful deep learning-based AI frameworks (Hayes et al., 2023; Crossa et al., 2025; Li et al., 2025).

Currently, breeding programs are under pressure not only to increase yield stability but also to deliver crops that are resilient, resource-efficient, and nutritionally dense, to strengthen global food supply chains amid escalating geopolitical tensions. However, achieving the optimal genomic compositions for multiple traits simultaneously remains challenging. For example, the ideotype breeding framework proposed by C.M. Donald over fifty years ago, which advocates designing plant types with ideal trait combinations (Donald, 1968), still struggles to find full implementation. Why? Because yield stability, plant architecture, or nutrient use efficiency are highly polygenic, with inherent trade-offs with other traits, and are environment-dependent. Recent advances applying ensemble-based models have initiated iterative prediction-experimental testing of ideotype targets (Cooper et al., 2025). While genomic prediction effectively captures patterns and correlations for the final trait outcome (yield per hectare), it overlooks nuanced interplay among determinant traits and their implications for plant performance. Contrastingly, functional biology-based approaches provide causal insights, but are often confirmed in limited genetic backgrounds and environments. Given this, the critical question is, what will lead to ideal crop genotypes? Following patterns, or understanding processes that shape them?

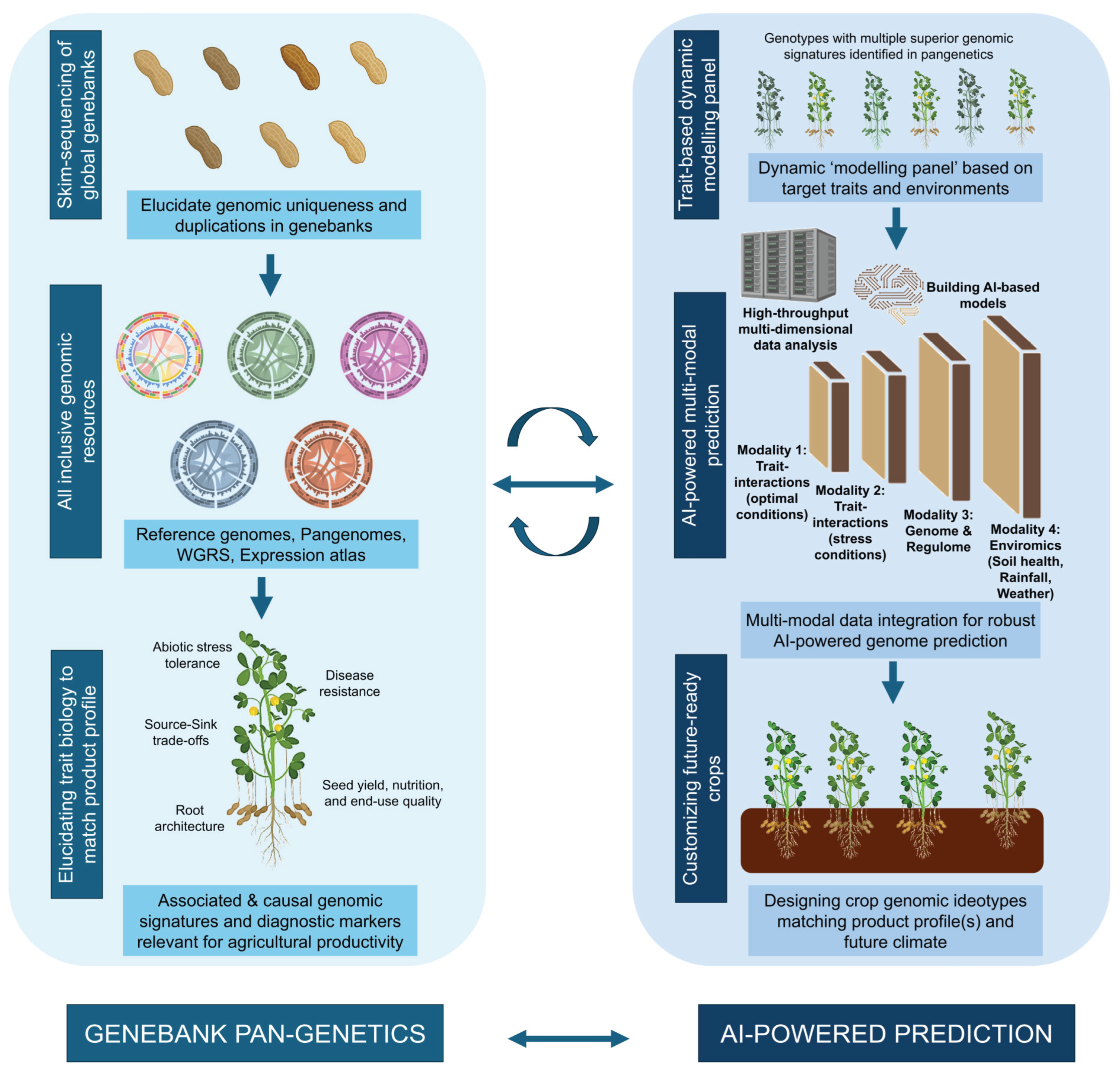

We argue that new opportunities for crop improvement lie in striking a balance – combining the statistical power and scalability of quantitative genetics with causal understanding derived from molecular genetics (

Figure 1). But, how? Here, we discuss the current progress in molecular and quantitative genetics and envision a future where they could be integrated.

Pangenetics: Unlocking Functional and Trait-Associated Polymorphisms

Global genebanks, which house millions of accessions from cultivated crops and their wild relatives, are both a legacy of the past and a hope for the future. However, their practical utility is constrained by limited knowledge on the depth of their diversity and potential duplications. Genomic curation enables large-scale digital cataloguing of genebank collections, spotting duplicates, validating accession identity, and revealing hidden allelic variation (Mascher et al., 2019). Such genebank genomics analyses facilitate an informed selection of genotypes for building pangenomes, capturing both core and variable gene sets and the full extent of structural and presence-absence variation within a species or genus. Alongside these, whole-genome resequencing, spatio-temporal gene expression atlases, and emerging single-cell transcriptomics support functional genomics and trait dissection through a reductionist approach.

This biology-first approach forms the core of what can now be termed pangenetics (Benoit et al., 2025), a conceptual expansion beyond pangenomics. While pangenomics describes the “what” of genetic variation, pangenetics aims to explain the “why” and “how”. It focuses on the functional understanding of causal polymorphisms, identifying alleles and gene regulatory networks that affect traits of agronomic and adaptive significance using a large-scale genomics approach (Benoit et al., 2025; Zhao et al., 2025). Moreover, haplotype (combinations of linked variants inherited together) provides a more powerful and informative unit for selection than SNPs for identifying the best parental lines for tailored crop improvement (Bevan et al., 2017). Integration of these multi-dimensional data layers enables the prioritization of functional polymorphisms that can then be converted into diagnostic markers for deployment in breeding.

AI-Based Prediction Models: The Power of Pattern Recognition

Quantitative genetics approach operates on the foundational principle that complex phenotypes arise from the cumulative effect of numerous small-effect variations, referred to as minor alleles. Genomic prediction builds on this concept by applying mathematical models to uncover patterns linking genotypic and phenotypic data, enabling the prediction of breeding values for informed breeding decisions (Hayes et al., 2023; Crossa et al., 2025). Until recently, genomic prediction based on linear models, relying on the additive genetic variance, was one of the most widely used genomic prediction methods. But, their limitations in modeling complex interactions, prompted increased interest in non-linear approaches to better predict phenotypic expression (Hayes et al., 2023; Crossa et al., 2025; Cooper et al., 2025).

As agricultural challenges become increasingly multidimensional, data science has entered the AI era, where robust deep learning (DL) approaches offer increased flexibility and power for detecting intricate patterns in large datasets involving multiple dimensions, incorporating genomics, phenomics and enviromics (Montesinos-López et al., 2024). While genomics captures the inherent genetic potential of the plant, phenomics reflects performance of a genotype under specific conditions, which can now be captured using high-throughput imaging or sensor technologies at increased resolution. Enviromics introduces a dynamic, environmental layer – temperature, rainfall patterns, soil health, and management practices, enabling models to predict performance under specific agroecologies. In recent years, multi-modal DL-based predictions have been successfully performed for the grain/seed yield across various crops, including soybean, maize, barley, and wheat (reviewed by Montesinos-López et al., 2024). Overall, prediction breeding is primarily a data-driven approach, allowing breeders to capitalize on large-scale enviromic, phenotypic and genomic data for the selection of promising genotypes, even when mechanistic gene-trait relationships are unclear, by explicitly accounting for the uncertainty through quantifying the distributional properties of the relationships.

Bridging the Divide: Functional Genomics Assisting Smarter Predictions

As outlined in earlier sections, AI-based prediction models mark a new milestone in plant breeding. But can integrating biological dimensions further enhance their prediction accuracy and accelerate genetic gains? Here, we emphasize that the emerging challenge is not to choose between biology and prediction, but rather to bridge the gap that ultimately leads to more informed crop breeding (

Figure 1).

Pangenetic analyses, which connect genetic polymorphisms to their trait-relevant functions, provide a foundation for this integration. Instead of treating all genetic variants equally, prediction models can now be guided by biological insights, including QTLs, haplotype variations, causal genes, and gene regulatory networks (

Figure 1). This ensures that models are informed not just by correlation, but also by trait-associated genomic signatures and genetic networks. In this context, deep learning (DL) architectures are now being tailored to incorporate key biological structures. Interestingly, DL-based genomic prediction showed better accuracies upon incorporating multi-omics datasets across three crops – wheat, maize, and tomato (Wang et al., 2023). This indicates that biologically informed AI models can provide previously missing details for model training.

But the promise need not stop at higher accuracy—it can also accelerate genetic gains. For example, rice researchers have pursued drought tolerance through two long-standing strategies: i. direct selection for grain yield (qDTYs), achieving 1.9% annual genetic gain under drought (Kumar et al., 2021); and ii. trait-based reductionist approaches like introducing deeper rooting system (DRO1) (Uga et al., 2013). Surprisingly, these strategies have been pursued only in isolation so far. Could integrating such functional insights into predictive models unlock the next leap in yield stability under drought and be scalable to other traits and crops? And how?

Pangenetics, when applied at the genebank scale unlocks hidden diversity to assemble a “dynamic modelling panel”: a curated set of lines carrying desirable genomic signatures for various determinant traits, based on a particular environment and product profile, which can be used for building multi-modal models. The resulting AI-driven predictions can inform the design of crop genomic ideotypes tailored to the specific agroecological context, aligned with evolving market demands. Bidirectional feedback based on new insights can regularly improve biological relevance of the prediction models, but also test prediction-guided functional genetics hypotheses, eventually leading to next-generation crop genomic ideotypes suiting future demands (

Figure 1).

Funding

Authors are thankful to the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India; Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) through ICAR-ICRISAT collaborative project; and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), USA, through Tropical Legumes III project.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely apologize to colleagues whose contributions could not be cited due to space restrictions. No conflict of interest declared.

References

- Benoit, M. , Jenike, K. M., Satterlee, J. W., Ramakrishnan, S., Gentile, I., Hendelman, A., Passalacqua, M. J., Suresh, H., Shohat, H., Robitaille, G. M., et al. Solanum pan-genetics reveals paralogues as contingencies in crop engineering. Nature 2025, 640, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevan, M. W. , Uauy, C., Wulff, B. B. H., Zhou, J., Krasileva, K., and Clark, M. D. Genomic innovation for crop improvement. Nature 2017, 543, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. , Tomura, S., Wilkinson, M. J., Powell, O., and Messina, C. D. Breeding perspectives on tackling trait genome-to-phenome (G2P) dimensionality using ensemble-based genomic prediction. Theor Appl Genet 2025, 138, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossa, J. , Martini, J. W. R., Vitale, P., Pérez-Rodríguez, P., Costa-Neto, G., Fritsche-Neto, R., Runcie, D., Cuevas, J., Toledo, F., Li, H., et al. Expanding genomic prediction in plant breeding: harnessing big data, machine learning, and advanced software. Trends Plant Sci 2025, 30, 756–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, C. M. The breeding of crop ideotypes. Euphytica 1968, 17, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B. J. , Chen, C., Powell, O., Dinglasan, E., Villiers, K., Kemper, K. E., and Hickey, L. T. Advancing artificial intelligence to help feed the world. Nat Biotechnol 2023, 41, 1188–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A. , Raman, A., Yadav, S., Verulkar, S. B., Mandal, N. P., Singh, O. N., Swain, P., Ram, T., Badri, J., Dwivedi, J. L., et al. Genetic gain for rice yield in rainfed environments in India. Field Crops Res 2021, 260, 107977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G. , An, L., Yang, W., Yang, L., Wei, T., Shi, J., Wang, J., Doonan, J. H., Xie, K., Fernie, A. R., et al. Integrated biotechnological and AI innovations for crop improvement. Nature 2025, 643, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascher, M. , Schreiber, M., Scholz, U., Graner, A., Reif, J. C., and Stein, N. Genebank genomics bridges the gap between the conservation of crop diversity and plant breeding. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 1076–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesinos-López, O. A. , Chavira-Flores, M., Kiasmiantini, Crespo-Herrera, L., Saint Piere, C., Li, H., Fritsche-Neto, R., Al-Nowibet, K., Montesinos-López, A., and Crossa, J. A review of multimodal deep learning methods for genomic-enabled prediction in plant breeding. Genetics 2024, 228, iyae161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uga, Y. , Sugimoto, K., Ogawa, S., Rane, J., Ishitani, M., Hara, N., Kitomi, Y., Inukai, Y., Ono, K., Kanno, N., et al. Control of root system architecture by DEEPER ROOTING 1 increases rice yield under drought conditions. Nat Genet 2013, 45, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K. , Abid, M. A., Rasheed, A., Crossa, J., Hearne, S., and Li, H. DNNGP, a deep neural network-based method for genomic prediction using multi-omics data in plants. Mol Plant 2023, 16, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K. , Xue, H., Li, G., Chitikineni, A., Fan, Y., Cao, Z., Dong, X., Lu, H., Zhao, K., Zhang, L., et al. Pangenome analysis reveals structural variation associated with seed size and weight traits in peanut. Nat Genet 2025, 57, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).