Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analytical Scope and Purpose

2.2. Source Selection

2.3. Analytical Procedure and Indicators

2.4. Ensuring Theoretical Rigor

3. Results

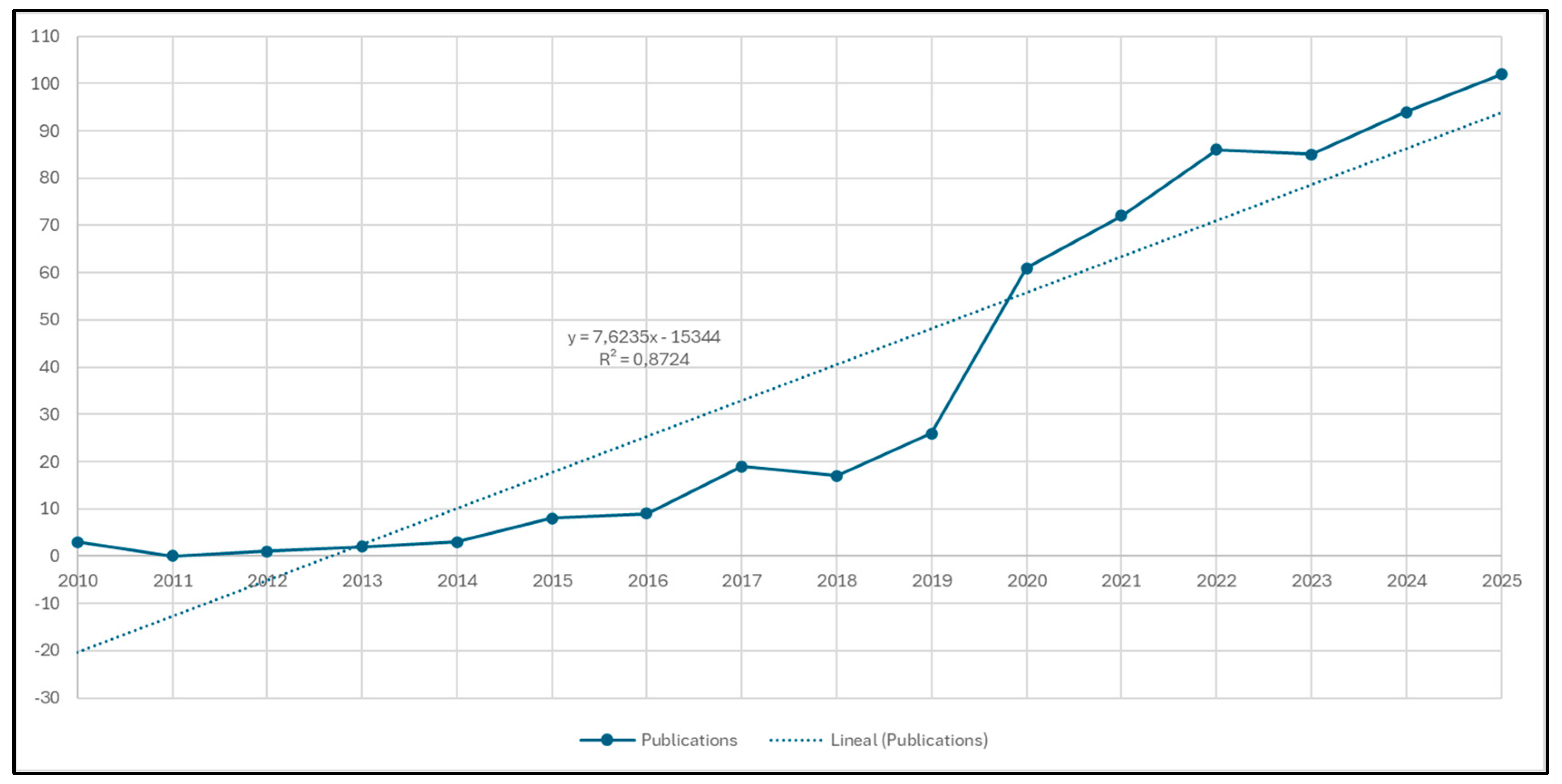

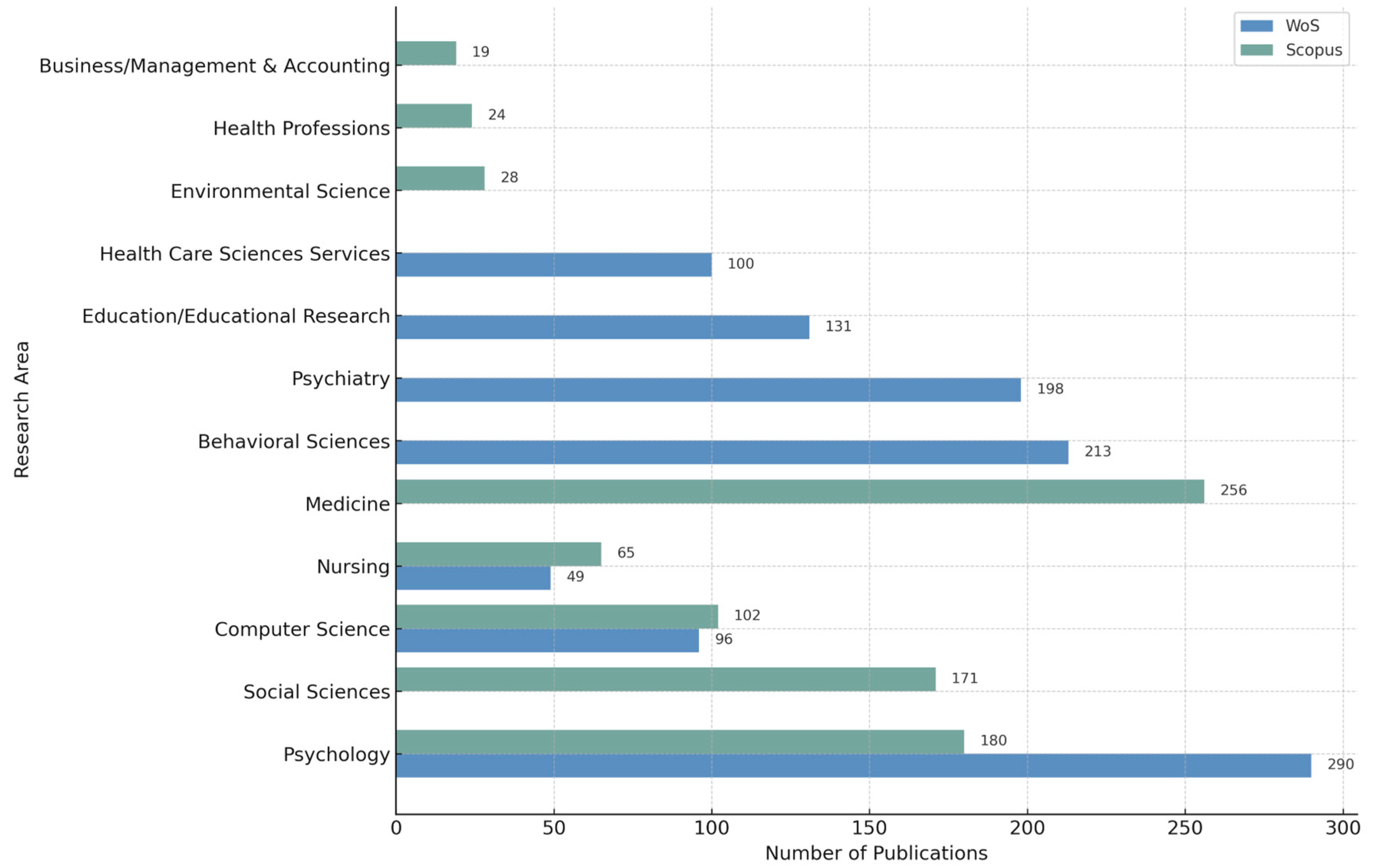

3.1. Findings and Proposals Regarding Objectives 1 and 2

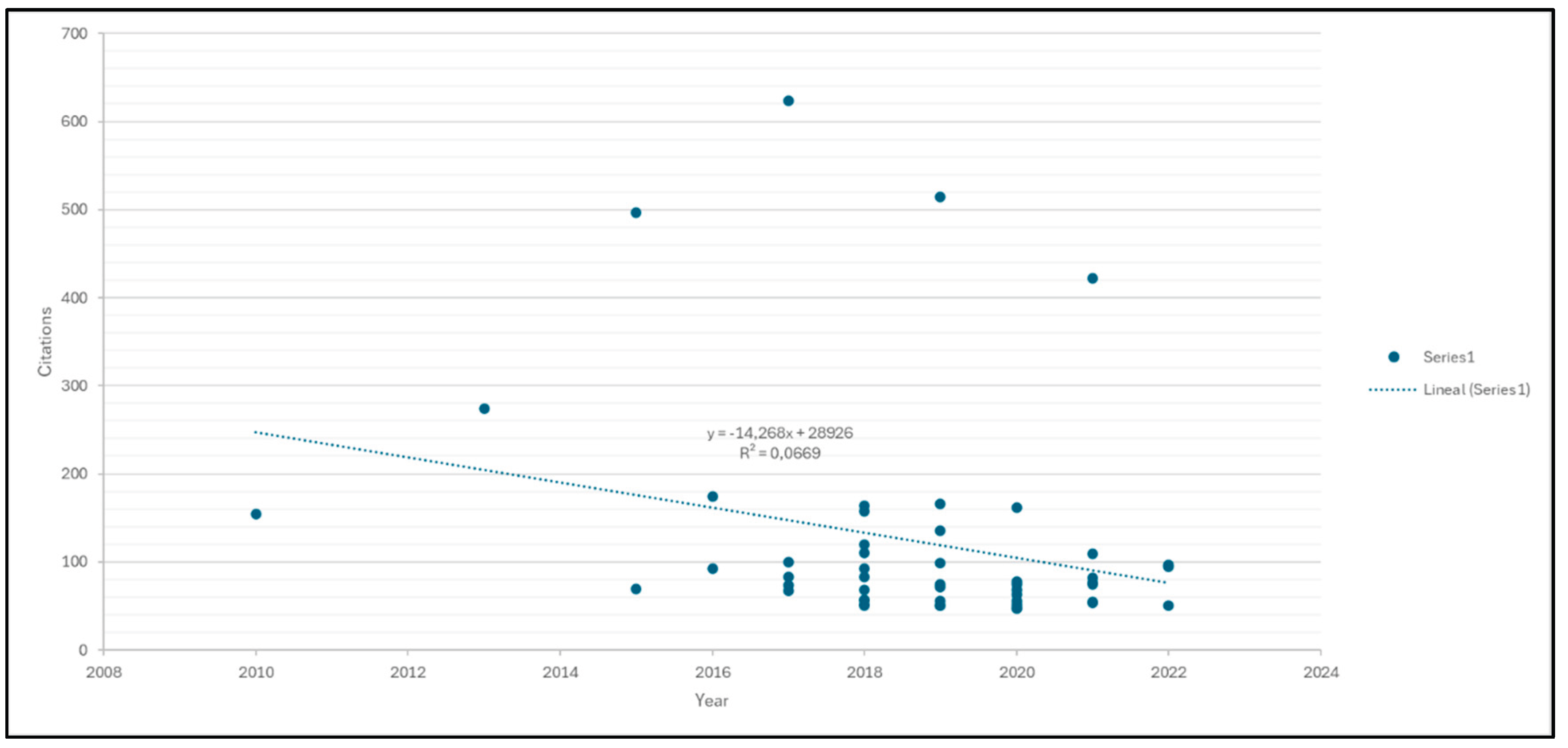

3.2. Academic Vitality, Gaps and Controversies

3.3. Findings and Proposals Regarding Objectives 3 and 4

| Level | Intervention Pillar | Main Measures |

Key Indicators |

Target (4–12 weeks) |

|

- MICRO- (Individual/ Family) |

||||

|

Circadian Regulation & Sleep Hygiene |

Implement a digital curfew and create a phone-free sleep sanctuary. | 90-min digital disconnect before sleep Phone-free bedrooms Automated "Do Not Disturb and red filters" (20:00–07:00) |

Sleep latency (min) Sleep quality (scale 1-5) Nocturnal awakenings Total sleep time (min) |

+30–45 min sleep; 0 nocturnal device use |

|

Digital Environment Redesign |

Configure device settings to minimize attention capture and compulsive use. | Activate grayscale mode Disable non-essential notifications & badges Remove autoplay features Use app limits (e.g., 15 min, 3x/day) |

Daily device checks Notifications received/day Minutes in targeted apps |

≥30% reduction in checks; improved sustained attention |

|

Nature Connection |

Integrate daily, phone-free exposure to natural environments. | 10-15 min daily "green breaks" Phone-free walks before/after digital sessions |

Weekly green time (min) Outdoor minutes/day Perceived stress (scale 1-5) |

+20% green time; reduced stress scores |

|

Physical Activity |

Incorporate regular movement and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA). | ≥60 min/day MVPA (adolescents) 150–300 min/week MVPA (adults) Active breaks every 50–90 min |

MVPA minutes/week Daily steps Well-being score (WHO-5) |

+15% MVPA; enhanced well-being |

| Education & Training | Deliver a curriculum on the digital attention economy and self-regulation. | Module 1: The Attention Economy Module 2: Persuasive Design Module 3: Self-Regulation Strategies |

Task completion rates Sleep quality Phone separation anxiety (0-10) |

Reduced anxiety; improved sleep & task compliance |

|

Adult Modeling |

Demonstrate coherent digital behaviors aligned with established family rules. | Create shared family agreements Adults adhere to all device rules (e.g., no phones at meals) |

% of phone-free meals Adherence to "phone-out-of-bedroom" rule |

≥80% behavioral coherence |

|

- MESO - (Organizational) | ||||

| Redesign of Education & Work Practices | Restructure processes to intrinsically protect focus and reduce digital intrusions. | Implement single-task blocks (25-50 min) Establish asynchronous communication protocols Redesign LMS/tools to batch notifications |

% of scheduled focus blocks respected Avg. response time to non-urgent messages Non-essential alerts/user/week |

Improved attentional climate; reduced perceived fatigue |

|

Explicit Institutional Policies |

Establish and enforce clear digital well-being norms. | Institutional "night mode" (no comms after hours) Designated device-free zones/classrooms |

Policy adherence rate Number of phone-free spaces |

Reinforced digital norms |

| Capacity Building | Train staff to lead and sustain digital well-being initiatives. | Staff training in critical digital literacy Implementation of psychoeducation programs | Number of trained personnel Number of active programs |

Strengthened institutional culture |

|

- MACRO - (Policy/Sectoral) | ||||

| Public Policy | Integrate digital well-being standards across health and education sectors. | Develop integrated well-being standards Enact notification regulations Launch public awareness campaigns |

% of orgs with phone-free policies Inclusion in national health surveys |

Systemic alignment |

| Regulatory Oversight | Ensure platform accountability and compliance with safety standards. | Enforce DSA/equivalent regulations Conduct independent platform audits |

Compliance rates Audit outcomes |

Accountable platform ecosystem |

| Investment & Research | Fund research and develop national guidelines for digital mental health. | Allocate public funding for research Develop national guidelines |

||

| Level | Dimension to Evaluate | Data Source & Method | Frequency |

| Micro (Individual/ Family) |

Changes in digital habits, sleep, stress, well-being, and knowledge. |

Pre-/Post-Questionnaires (Standardized scales) Digital Tracker Data Focus Groups with families & adolescents. |

Baseline, 3, 6, 12 months. |

| Meso (Organizational) | Implementation fidelity, changes in organizational climate, and policy adherence. |

Organizational Audits: Document review of policies and LMS notification settings. Staff/Student Surveys: On attentional climate and communication norms. Structured Interviews: with administrators and team leaders. |

Baseline, 6, 12 months. |

| Macro (Policy/Sectoral) | Policy adoption, shifts in public discourse, and research investment. |

Policy Analysis: of new regulations, public health campaigns, and educational curricula. Analysis of Public Data, e.g., Research funding databases, national health survey results. Stakeholder Interviews with policymakers and platform regulators. |

3.4. Behavioral and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Protocols

| Intervention Technique | Therapeutic Foundation | Specific Implementation & Rationale |

| Scheduled Usage Windows |

Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) Committed Action |

Value-driven actions for focused attention and reduce mobile use. |

| Contingency Contracts | Mindfulness & Self-Monitoring |

Self-monitoring as a non-judgmental practice of mindful awareness. |

| Self Regulation Training |

Skill Building & Goal Setting |

Direct training in foundational self-regulation skills, such as specific goal-setting techniques and brief, daily mindfulness practices. |

| Boredom Tolerance Workshops |

Attentional Restoration & Self-Regulation | Structured training to build the capacity to remain in states of non-stimulation through exercises like observation, meditation, or waiting without a device. |

| In-Person Social Skills Training |

Social Development & Anxiety Management | For younger populations, direct training to counteract deficits in conversation skills, eye contact, and social anxiety management, reducing reliance on the device as a social crutch. |

3.5. Psychoeducation and Critical Digital Literacy

| Strategic Pillar | Core Objective | Key Actions & Implementation |

| Promotion of a "Culture of Disconnection" |

To extend the "right to disconnect" from the workplace to all spheres of life, legitimizing digital boundaries as essential for mental health and deep work. | Normalize Explicit Practices: Encourage the use of status messages (e.g., "In focus mode") and manage response-time expectations. Deactivate Guilt: Publicly affirm that not being permanently reachable is a necessity, not a failure. |

| Critical Stance Digital Literacy & Advocacy |

To move from individual awareness to collective empowerment, enabling citizens to demand and shape a more ethical digital ecosystem. | Citizen Audits: Train people to collectively identify, document, and report pernicious addictive design patterns to pressure platforms. Demand "Ethical Design": Foster informed consumer choice and actively support platforms that avoid dark patterns, offer healthy defaults, and ensure algorithmic transparency. |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

References

- Ahmed, M.D.F. Rethinking Digital Mental Health: From Nomophobia to Neurocognitive Exhaustion in LMIC Youth. Health Science Reports 2025, 8, e71278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrubaia, H.; Alabdi, Z.; Alnaim, M.; Alkhteeb, N.; Almulhim, A.; Alsalem, A.; Aldarwish, R.; Algouf, I.; Almaqhawi, A. The impact of cell phone use after light out on sleep quality, headache, tiredness, and distractibility among high school students: Cross sectional study. Heliyon 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asha, S.; Radhakrishnan, V. Beyond the screen: The psychological significance of ecophilia in childhood. MethodsX 2025, 14, 103263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalatti, S.; Pawar, U. Addictive Interfaces: How Persuasion, Psychology Principles, and Emotions Shape Engagement. In Interactive Media with Next-Gen Technologies and Their Usability Evaluation; Chapman and Hall/CRC: 2024; pp. 47–66.

- Bandura, A.; Ross, D.; Ross, S.A. Vicarious reinforcement and imitative learning. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 1963, 67, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Extended self in a digital world. Journal of Consumer Research 2013, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum-Ross, A.; Livingstone, S. Families and screen time : Current advice and emerging research. Media Policy Brief 2016.

- Bragazzi, N. L.; Del Puente, G. A proposal for including nomophobia in the new DSM-V. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttaboni, C.; Colangelo, G.; Floridi, L. The Ethical and Legal Implications of the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act in the European Union Legal Framework. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=5110753.

- Chaouche, D. C.; Bessais, T. Social Networks and the Exploitation of Digital Data From the Empire of Surveillance to the Economy of Attention. Dirasat: Human and Social Sciences, 2022; 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, J. D.; Moreno, M. A. Not at the dinner table–take it to your room: adolescent reports of parental screen time rules. Communication Research Reports, 2019; 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, P. G.; Pérez-Verdugo, M.; Barandiaran, X. E. Attention is all they need: Cognitive science and the (techno) political economy of attention in humans and machines. AI & SOCIETY 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Masip, V.; Sora, B.; Serrano-Fernandez, M. J.; Boada-Grau, J.; Lampert, B. Personality and Nomophobia: The Role of Dysfunctional Obsessive Beliefs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2023; 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, M. E.; Aistis, L. A.; Sachs, N. A.; Williams, M.; Roberts, J. D.; Rosenberg Goldstein, R. E. Reducing Anxiety with Nature and Gardening (RANG): Evaluating the Impacts of Gardening and Outdoor Activities on Anxiety among U.S. Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022; 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A. B. , Fabbri, A., Baum, F., Bertscher, A., Bondy, K., Chang, H. J., Demaio, S., Erzse, A., Freudenberg, N., Friel, S., Hofman, K. J., Johns, P., Abdool Karim, S., Lacy-Nichols, J., de Carvalho, C. M. P., Marten, R., McKee, M., Petticrew, M., Robertson, L., … Thow, A. M. Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. The Lancet, 2023; 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göktaş; A; Üstündağ; A The association between anxiety, activity performance and nomophobia in students. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 34414.

- Göktaş; A; Üstündağ; A The association between anxiety, activity performance and nomophobia in students. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 34414.

- González-Cabrera, J.; León-Mejía, A.; Pérez-Sancho, C.; Calvete, E. Adaptación al español del cuestionario Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q) en una muestra de adolescentes TT - Adaptation of the Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q) to Spanish in a sample of adolescents. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría, 2017; 45. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear, V. A. , Randhawa, A., Adab, P., Al-Janabi, H., Fenton, S., Jones, K., Michail, M., Morrison, B., Patterson, P., Quinlan, J. School phone policies and their association with mental wellbeing, phone use, and social media use (SMART Schools): a cross-sectional observational study. The Lancet Regional Health–Europe, 2025; 51. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, A.; Gatersleben, B. Let’s go outside! Environmental restoration amongst adolescents and the impact of friends and phones. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2016, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra Ayala, M. J. , Alegre de la Rosa, O. M., Chambi Catacora, M. A. del P., Vargas Onofre, E., Cari Checa, E., Díaz Flores, D. Nomophobia, phubbing, and deficient sleep patterns in college students. Frontiers in Education 2025, 9, 1421162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, C.L. C. , de Oliveira, L. B. S., Pereira, R. S., da Silva, P. G. N., Gouveia, V. V. Nomophobia and smartphone addiction: do the variables age and sex explain this relationship? Psico-USF, 2022; 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guld, Á. Influencer Agencies: The Institutionalization of the Digital Attention Economy. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Social Analysis, 2023; 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habelt, L.; Kemmler, G.; Defrancesco, M.; Spanier, B.; Henningsen, P.; Halle, M.; Sperner-Unterweger, B.; Hüfner, K. Why do we climb mountains? An exploration of features of behavioural addiction in mountaineering and the association with stress-related psychiatric disorders. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 2023, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handa, S.; Jain, N. Always On, Always Trapped: Nomophobia and the Rising Tide of Stress. International Journal of Indian Psych, 2025; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, T. M. , Arnold, D. H. Mobile Technology and School Readiness: An Adverse Relationship with Executive Functioning in Low-Income Preschoolers. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2024, 33, 3338–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmayer, M. The second wave of attention economics. Attention as a universal symbolic currency on social media and beyond. Interacting with Computers 2025, 37, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, K.; Ferreira, P.; Brown, B.; Lampinen, A. Away and (Dis)connection: Reconsidering the use of digital technologies in light of long-term outdoor activities. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 2019; 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessari, H.; Busch, P.; Smith, S. Tackling nomophobia: the influence of support systems and organizational practices. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2025, 30, 572–601. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, A.C. Y. , Thi, T. D. P., Hou, X. Understanding problematic TikTok use: Cognitive absorption, nomophobia, and life stress. Acta Psychologica 2025, 260, 105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, V.V. The impact of public health interventions in a developing nation: an overview. South Sudan Medical Journal 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kear, A.; Folkes, S.L. Digital technology disorder: Justification and a proposed model of treatment. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Exercise rehabilitation for smartphone addiction. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.L. S. , Valença, A. M., Nardi, A. E. Nomophobia: The mobile phone in panic disorder with agoraphobia: Reducing phobias or worsening of dependence? Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology 2010, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.L. S. , Valença, A. M., Silva, A. C. O., Baczynski, T., Carvalho, M. R., Nardi, A. E. Nomophobia: Dependency on virtual environments or social phobia? Computers in Human Behavior 2013, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.L. S. , Valença, A. M., Silva, A. C., Sancassiani, F., Machado, S., Nardi, A. E. “Nomophobia”: Impact of Cell Phone Use Interfering with Symptoms and Emotions of Individuals with Panic Disorder Compared with a Control Group. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 2014; 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyzelis, M. The Philosophical Aspect of Contemporary Technology: Ellulian Technique and Infinite Scroll within Social Media. Filosofija, Sociologija, 2024; 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Mejía, A. C. , Gutiérrez-Ortega, M., Serrano-Pintado, I., González-Cabrera, J. (). A systematic review on nomophobia prevalence: Surfacing results and standard guidelines for future research. PLoS ONE, 2021; 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Mejía, A.; Calvete, E.; Patino-Alonso, C.; Machimbarrena, J. M. , González-Cabrera, J. Nomophobia questionnaire (Nmp-q): Factorial structure and cut-off points for the spanish version. Adicciones, 2021; 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L.; Wei, R. More than just talk on the move: Uses and gratifications of the cellular phone. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 2000, 77, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, R. A brief history of individual addressability: The role of mobile communication in being permanently connected. In Permanently Online, Permanently Connected; Routledge: 2017; pp. 10–17.

- Linnenluecke, M. K. , Marrone, M., Singh, A. K. Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. K. Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Australian Journal of Management 2020, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G.; Wojtowicz, Z. The economics of attention. Journal of Economic Literature 2025, 63, 1038–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddock, J. E. , Frumkin, H. Physical activity in natural settings: An opportunity for lifestyle medicine. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 2025, 19, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makas, S.; Bekir, S.; Dombak, K.; Batmaz, H.; Kaya, M.; Celik, E. Loneliness and nomophobia in the context of risks to mental health: smartphone addiction. Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology 2025, 25, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, S.; Eller, M.; Stout, R. Lifestyle medicine and behavioral health: A time for deeper integration. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezei, K.; Träger, A. Risks and Resilience in the European Union’s Regulation of Online Platforms and Artificial Intelligence: Hungary in Digital Europe. The Resilience of the Hungarian Legal System since 2025, 2010, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Mialon, M. An overview of the commercial determinants of health. Globalization and Health 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miksch, L.; Schulz, C. (2018). Disconnect to Reconnect: The Phenomenon of Digital Detox as a Reaction to Technology Overload. In LUP Student Papers.

- Mohamed, S.A.A. K. , Shaban, M. Digital Dependence in Aging: Nomophobia as the New Mental Health Threat for Older Adults. Journal of Emergency Nursing 2025, 51, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, A. A. , Tanvir, S., Ramzan, M., Mukhtar, M., Ullah, R. EFFECT OF NOMOPHOBIA ON ACADEMIC STRESS AND ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE AMONG STUDENTS. Contemporary Journal of Social Science Review 2025, 3, 2886–2898. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Rodríguez, J. M. , Torrijos Fincias, P., Serrate González, S., Murciano Hueso, A. Digital environments, connectivity and education: Time perception and management in the construction of young people’s digital identity. Revista Espanola de Pedagogia, 2020; 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L. S. , Norris, J. M., White, D. E., Moules, N. J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2017; 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Brezmes, J.; Ruiz-Hernández, A.; Blanco-Ocampo, D.; García-Lara, G. M. , Garach-Gómez, A. Mobile phone use, sleep disorders and obesity in a social exclusion zone. Anales de Pediatría (English Edition) 2023, 98, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoye, C.A.F. O. , Harry, H. O.-N., Obikwelu, V. C. Nomophobia among undergraduate: Predictive influence of personality traits. Practicum Psychologia, 2017; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Orhan, Z. Digital dependency and its consequences for human well-being. Future Digital Technologies and Artificial Intelligence 2025, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J. , Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., Mcdonald, S., … Mckenzie, J. E. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ, 2021; 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotidi, M.; Overton, P. Attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms predict problematic mobile phone use. Current Psychology 2022, 41, 2765–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păsărelu, C. R. , Andersson, G., Dobrean, A. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder mobile apps: A systematic review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 2020; 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspitasari, F. D. , Lee, L.-H. Review of Persuasive User Interface as strategy for technology addiction in Virtual Environments. 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), 2022; 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Radesky, J. S. , Kaciroti, N., Weeks, H. M., Schaller, A., Miller, A. L. Longitudinal associations between use of mobile devices for calming and emotional reactivity and executive functioning in children aged 3 to 5 years. JAMA Pediatrics 2023, 177, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, T.; Apel, T.; Schenkel, K.; Keller, J.; von Lindern, E. Digital detox: An effective solution in the smartphone era? A systematic literature review. Mobile Media and Communication 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, N.; Al-Asoom, L. I. , Alsunni, A. A., Saudagar, F. N., Almulhim, L., Alkaltham, G. Effects of mobile use on subjective sleep quality. Effects of mobile use on subjective sleep quality. Nature and Science of Sleep 2020, 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Soler, I.; López-Sánchez, C.; Quiles-Soler, C. Nomophobia in teenagers: Digital lifestyle, social networking and smartphone abuse. Communication and Society 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, M.; Niermann, C.; Jekauc, D.; Woll, A. Long-term health benefits of physical activity – a systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Lu, X.; Ren, S.; Li, M.; Liu, T. Comparative network analysis of nomophobia and mental health symptoms among college and middle school students. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 2025; 19. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, R. E. , Janssen, I., Bredin, S. S., Warburton, D. E., Bauman, A. Physical activity: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychology & Health 2017, 32, 942–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, A.-M.; Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J.; Lopez Belmonte, J. Nomophobia: An individual’s growing fear of being without a smartphone—a systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ŞAHİN; Y. L., SARSAR, F., SAPMAZ, F., HAMUTOĞLU, N. B. The Examination of Self-Regulation Abilities in High School Students within the Framework of an Integrated Model of Personality Traits, Cyberloafing and Nomophobia. Cukurova University Faculty of Education Journal, 2022; 51. [CrossRef]

- Sattar, F.; Rafique, N. Examining Relationship Between Nomophobia and Academic Performance; Moderating Role of Academic Motivation. Qlantic Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 2025, 6, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovov, R. Yu. Interdisciplinary Synthesis of Behavioral Design Theory. AlterEconomics 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, S.E. H. , Gan, W. Y., Poon, W. C., Lee, L. J., Ruckwongpatr, K., Kukreti, S., Griffiths, M. D., Pakpour, A. H., Lin, C.-Y. The mediating effect of nomophobia in the relationship between problematic social media use/problematic smartphone use and psychological distress among university students. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 2025; 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Uguz, G.; Bacaksiz, F.E. Relationships between personality traits and nomophobia: Research on nurses working in public hospitals. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsaw, R. E. , Jones, A., Rose, A. K., Newton-Fenner, A., Alshukri, S., Gage, S. H. Mobile technology use and its association with executive functioning in healthy young adults: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 643542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmer, H. H. , Chein, J. M. Mobile technology habits: patterns of association among device usage, intertemporal preference, impulse control, and reward sensitivity. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2016, 23, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Liang, Y.; Shang, H. Long-term impact of using mobile phones and playing computer games on the brain structure and the risk of neurodegenerative diseases: Large population-based study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2025, 27, e59663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanxia zhu Jun, C.; Enming, Z. Understanding and addressing smartphone addiction: A multidisciplinary perspective. Journal of Addiction Medicine and Therapeutic Science 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Hikida, K.; Lu, Y.; Wang, L.; Dai, Q.; Aki, M.; Shibata, M.; Zakia, H.; Yang, J.; Oishi, N. Brain network alterations in mobile phone use problem severity: A multimodal neuroimaging analysis. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2025, 14, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Zhang, X.; Gong, Q. (). The effect of exposure to the natural environment on stress reduction: A meta-analysis. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 2021; 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Shen, Y. Development and validation of the compensatory belief scale for the internet instant gratification behavior. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yun, J.; Yao, W. A systematic review of the anxiety-alleviation benefits of exposure to the natural environment. Reviews on Environmental Health 2023, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).