Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What is the prevalence of nomophobia among college students?

- Apart from college students, who are the students in this survey who are at greater risk of experiencing feelings of regret when they go too long without using their cell phones?

- What are the most common locations on campus where students have trouble going without using their cell phones?

2. Literature Review Related Works

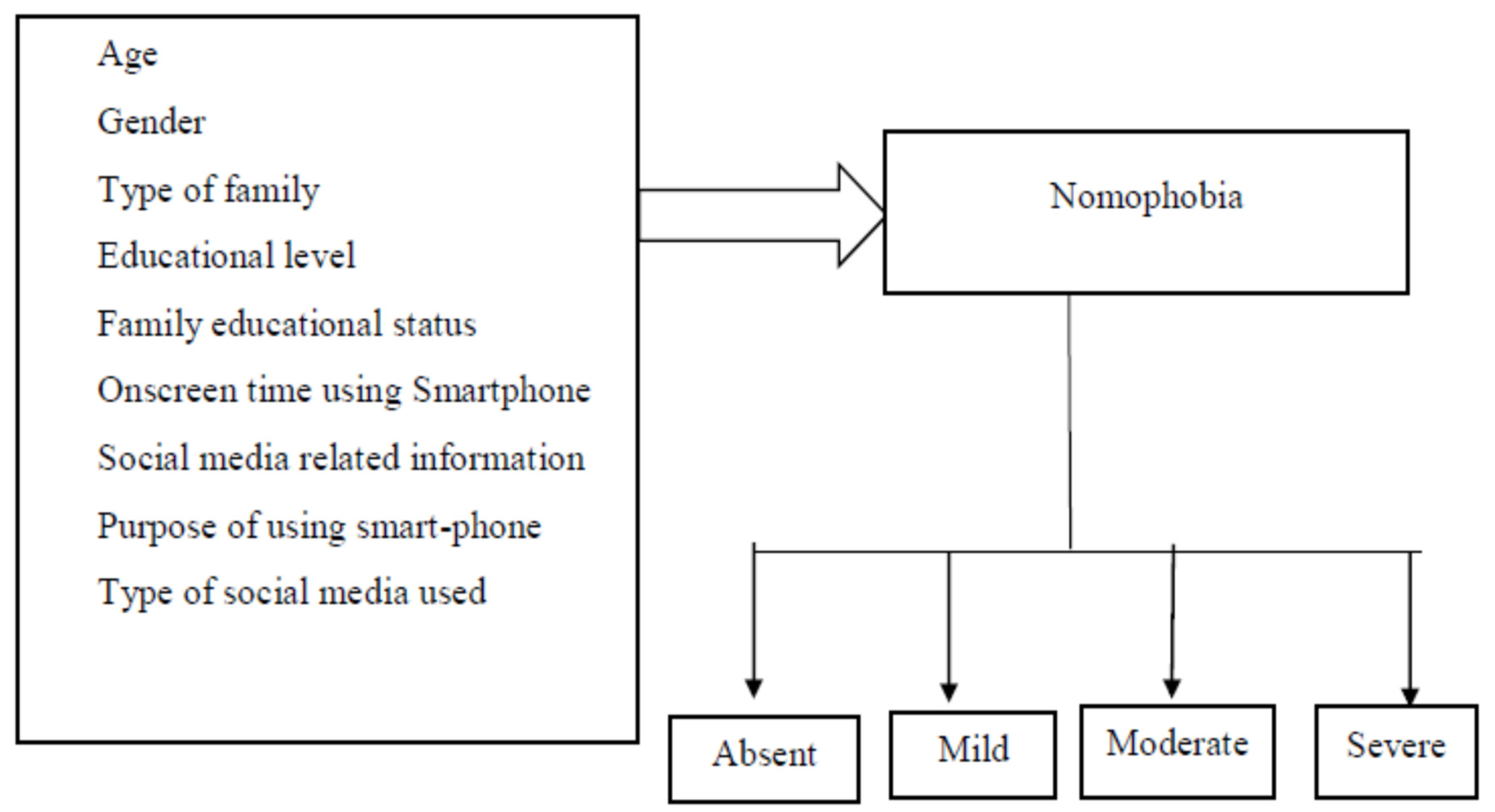

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

3.2. Study Population and Sampling

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Students studying in higher secondary levels (Grade 11 and Grade 12) of Kathmandu College of Central State.

- Enrolled in private colleges at the time of the study.

- Those students who use smartphones regularly.

- Willing to participate and provide informed consent.

3.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Students with diagnosed psychiatric disorders affecting phone usage behavior.

- Those who declined to participate or returned incomplete questionnaires.

3.4. Data Collection Instrument

3.5. Data Collection Procedure

3.6. Ethical Considerations

3.7. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Level of Nomophobia

4.31. Risk Factors of Nomophobia

4.5. Relationship Between Socio-Demographic Variables and the Level of Nomophobia

4.6. Relationship Between Risk Factors of Nomophobia and the Level of Nomophobia

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamopoulos, I. P., and N. F. Syrou. 2022. Associations and Correlations of Job Stress, Job Satisfaction and Burn out in Public Health Sector. European Journal of Environment and Public Health 6, 2: em0113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamopoulos, I. P. 2022. Job Satisfaction in Public Health Care Sector, Measures Scales and Theoretical Background. European Journal of Environment and Public Health 6, 2: em0116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamopoulos, I., D. Lamnisos, N. Syrou, and G. Boustras. 2022. Public health and work safety pilot study: Inspection of job risks, burnout syndrome, and job satisfaction of public health inspectors in Greece. Safety Science.

- Adamopoulos, I., N. Syrou, D. Lamnisos, and G. Boustras. 2023. Cross-sectional nationwide study in occupational safety and health: Inspection of job risks, burnout syndrome, and job satisfaction of public health inspectors during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. Safety Science 158: 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adawi, M., R. A. Alghamdi, and A. M. Althobaiti. 2023. Nomophobia among nursing students: prevalence and associated factors. BMC Nursing 22, 1: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M., W. Mahmood, and A. Saleem. 2024. Smartphone Induced Anxiety: An Investigation into Nomophobia and Stress Levels Among Universities Students. Journal for Social Science Archives 2, 2: 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhahir, A. M., H. M. Bintalib, R. A. Siraj, J. S. Alqahtani, O. A. Alqarni, A. A. Alqarni, and H. Alwafi. 2023. Prevalence of nomophobia and its impact on academic performance among respiratory therapy students in Saudi Arabia. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamun, F., M. A. Mamun, M. S. Prodhan, M. Muktarul, M. D. Griffiths, M. Muhit, and M. T. Sikder. 2023. Nomophobia among university students: Prevalence, correlates, and the mediating role of smartphone use between Facebook addiction and nomophobia. Heliyon 9, 3: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, M. S., M. Fox, R. Coman, Z. A. Ratan, and H. Hosseinzadeh. 2022. Smartphone Addiction Prevalence and Its Association on Academic Performance, Physical Health, and Mental Well-Being among University Students in Umm Al-Qura University (UQU), Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, 6: 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S., K. R. Anoopa, P. G. Joseph, and S. Raju. 2022. A Study to Assess the Prevalence of Nomophobia among Nursing Students in Kollam. Indian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing 19, 2: 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Article, O. 2021. Nomophobia: A rising concern among Indian. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awed, H. S., and M. A. Hammad. 2022. Relationship between nomophobia and impulsivity among deaf and hard-of-hearing youth. Scientific reports 12, 1: 14208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartwal, J., and B. Nath. 2020. Evaluation of nomophobia among medical students using smartphone in north India. Medical Journal Armed Forces India 76, 4: 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, Betul Rana, Tasnim Hokan, Mahmut Barkut, Hasan Hayani, Sidra Altaha, Ayşe Altaha, Dilek Bal, Habiba Eyvazova, Cemal Elrahmun, Kursad Nuri Baydili, Mehmet Okumus, and Enes Akyuz. 2023. Nomophobia, Anxiety, and Burnout of Medical Students in Syria. Journal of US-China Medical Science 20, 1: 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, R., and A. Amankwaa. 2021. The relationship between the nomophobic levels of higher education students in Ghana and academic achievement. PLOS ONE 16, 6: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousgheiri, F., A. Allouch, K. Sammoud, R. Navarro-Martínez, V. Ibáñez-del Valle, M. Senhaji, O. Cauli, N. El Mlili, and A. Najdi. 2024. Factors Affecting Sleep Quality among University Medical and Nursing Students: A Study in Two Countries in the Mediterranean Region. Diseases 12, 5: 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copaja-Corzo, C., B. Miranda-Chavez, D. Vizcarra-Jiménez, M. Hueda-Zavaleta, M. Rivarola-Hidalgo, E. G. Parihuana-Travezaño, and A. Taype-Rondan. 2022. Sleep Disorders and Their Associated Factors during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Data from Peruvian Medical Students. Medicina 58, 10: 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, U., and R. Dutta. 2022. A review paper on prevalence of nomophobia among students and its impact on their academic achievement. Journal of Positive School Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Essel, H. B., D. Vlachopoulos, and A. Tachie-Menson. 2021. The relationship between the nomophobic levels of higher education students in Ghana and academic achievement. PLoS ONE 16, 6: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnardellis, C., E. Vagka, A. Lagiou, and V. Notara. 2023. Nomophobia and Its Association with Depression, Anxiety and Stress (DASS Scale), among Young Adults in Greece. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 13, 12: 2765–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, S., J. P. Singh, G. Paudel, S. Khatiwada, and S. Timilsina. 2020. How addicted are newly admitted undergraduate medical students to smartphones?: A cross-sectional study from Chitwan medical college, Nepal. BMC Psychiatry 20, 1: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A., A. Ani, A. Sharma, and V. Kumari. 2021. Nomophobia and social interaction anxiety among university students. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences 15: 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazem, A. M., M. M. Emam, M. N. Alrajhi, S. S. Aldhafri, H. S. AlBarashdi, and B. A. Al-Rashdi. 2021. Nomophobia in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence: the Development and Validation of a New Interactive Electronic Nomophobia Test. Trends in Psychology 29, 3: 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubrusly, M., P. G. de B. Silva, G. V. de Vasconcelos, E. D. L. G. Leite, P. de A. Santos, and H. A. L. Rocha. 2021. Nomophobia among medical students and its association with depression, anxiety, stress and academic performance. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica 45, 3: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. J. J., S. Yar, S. Fayyaz, I. Adamopoulos, N. Syrou, and A. Jahangir. 2024. From Pressure to Performance, and Health Risks Control: Occupational Stress Management and Employee Engagement in Higher Education. Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, A. Y., H. Alwafi, R. Itani, S. Alzayani, S. Qadus, R. Al-Rousan, G. M. Abdelwahab, E. Dahmash, A. AlQatawneh, H. M. J. Khojah, A. P. Kautsar, R. Alabbasi, N. Alsahaf, R. Qutub, H. M. Alrawashdeh, A. H. I. Abukhalaf, and M. Bahlol. 2023. Authors information: BMC Psychiatry 23, 1: 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Neelima, B. Y., J. P. Kumari, R. S. Pallavi, T. Sivakala, K. Srinivas, and G. R. Prabhu. 2023. A cross sectional study on nomophobia among medical students in Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh. International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health 10, 3: 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, M., S. Shakeel, S. Saqib, T. N. Shahid, K. Nawadat, and A. Fahim. 2021. Association of Nomophobia with Decision Making of. Dental Students 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, Salleh Sahimi H, MH Norzan, NR Nik Jaafar, S Sharip, A Ashraf, K Shanmugam, NS Bistamam, NE Mohammad Arrif, S Kumar, and M Midin. 2022. Excessive smartphone use and its correlations with social anxiety and quality of life among medical students in a public university in Malaysia: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry 13: 956168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puducherry, S., H. Phvvdjhv, Q. F. Zlwk, H. Lqvwlwxwlrqv, K. Surihvvlrqdov, V. Wdnh, D. Vwhsv, V. X. Flhqw, L. Dqg, H. Derxw, Q. Dqg, and V. Whfkqrorj. 2019. Nomophobia: A Mixed-Methods Study on Prevalence, Associated Factors, and Perception among College. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R., Y. P. S. Balhara, B. R. Mishra, S. Sarkar, A. Bharti, M. Sinha, S. Ahmad, P. Kumar, M. Jain, and S. Panigrahi. 2024. Description of Nomophobia Among College Students: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Indian journal of psychological medicine 46, 4: 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A., M. Shahzad, S. Hasnain, and H. Asad. 2022. Prevalence of nomophobia and its associated factors among medical students of a private medical college in Lahore. BioMedica 38, 4: 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, M. H., N. Aisya, A. Aziz, F. Leman, M. Mu’az Shaharani, P. Palanisamy, and V. Ramachandran. 2021. A Study on Nomophobia among Students of a Medical College in Malaysia. Asian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences 4, 2: 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sami, Lalitha Krishna & Iffat. 2010. “Impact of Electronic Services on Users: A Study”. JLIS.it. 1 (2). University of Florence. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, K., S. Lama, R. Pokharel, R. Sigdel, and S. P. Rimal. 2020. Mobile phone dependence among undergraduate students of a medical college of eastern nepal: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Journal of the Nepal Medical Association 58, 224: 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuco, K. G., S. D. Castro-Diaz, D. R. Soriano-Moreno, and V. A. Benites-Zapata. 2023. Prevalence of Nomophobia in University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare Informatics Research 29, 1: 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, C., E. Sumuer, M. Adnan, and S. Yildirim. 2023. The Prevalence of Mild, Moderate, and Severe Nomophobia Symptoms: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Behavioral Sciences 13, 1: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagka, E., C. Gnardellis, A. Lagiou, and V. Notara. 2023. Prevalence and Factors Related to Nomophobia: Arising Issues among Young Adults. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 13, 8: 1467–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagka, E., C. Gnardellis, A. Lagiou, and V. Notara. 2024. Smartphone Use and Social Media Involvement in Young Adults: Association with Nomophobia, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) and Self-Esteem. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, 7: 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwilling, M. 2022. The Impact of Nomophobia, Stress, and Loneliness on Smartphone Addiction among Young Adults during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Israeli Case Analysis. Sustainability 14, 6: 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S/No | Grade | Number of Students |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Grade 11 | 117 |

| 2 | Grade 12 | 114 |

| Total | 231 | |

| S/No | Variable | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age Group | |||

| ≤17 years | 156 | 67.5 | ||

| ≥18 years | 75 | 32.46 | ||

| 2 | Gender | |||

| Male | 110 | 47.6 | ||

| Female | 121 | 52.4 | ||

| 3 | Religion | |||

| Hinduism | 188 | 81.3 | ||

| Christian | 10 | 4.3 | ||

| Buddhism | 31 | 13.4 | ||

| Islam | 2 | 0.86 | ||

| 4 | Ethnicity | |||

| Brahmin/ Chhetri | 93 | 40.3 | ||

| Janajati | 86 | 37.2 | ||

| Madhesi | 10 | 4.3 | ||

| Dalit | 6 | 2.6 | ||

| Others | 36 | 15.6 | ||

| 5 | Type of Family | |||

| Nuclear | 130 | 56.3 | ||

| Joint | 82 | 35.5 | ||

| Extended | 16 | 6.9 | ||

| Others | 3 | 1.3 | ||

| 6 | Educational Level | |||

| Grade 11 | 117 | 50.6 | ||

| Grade 12 | 114 | 49.4 | ||

| 7 | Father’s Educational Status | |||

| Cannot read and write | 12 | 5.2 | ||

| Can read and write | 41 | 17.7 | ||

| Basic Level (1-8) | 54 | 23.4 | ||

| Secondary (9-12) | 96 | 41.6 | ||

| Bachelors | 16 | 6.9 | ||

| Masters and above | 12 | 5.2 | ||

| 8 | Mother’s Educational Status | |||

| Cannot read and write | 42 | 18.2 | ||

| Can read and write | 41 | 17.7 | ||

| Basic Level (1-8) | 69 | 29.9 | ||

| Secondary (9-12) | 63 | 27.3 | ||

| Bachelors | 12 | 5.2 | ||

| Masters and above | 4 | 1.7 | ||

| 9 | Place of Resident | |||

| House | 114 | 49.4 | ||

| Hostel | 3 | 1.3 | ||

| Rent (Room) | 106 | 45.9 | ||

| Relative House | 8 | 3.5 | ||

| 10 | Total monthly income of the family | |||

| Less than 20000 | 40 | 17.2 | ||

| 21000-50000 | 98 | 42.4 | ||

| 51000-100000 | 62 | 26.8 | ||

| More than 100000 | 31 | 13.4 | ||

| S/No | Variable | Frequency | Percentage | Mean | Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mild | 74 | 32.0 | 2.0173 | 0.81 |

| 2 | Moderate | 79 | 34.2 | ||

| 3 | Severe | 78 | 33.8 | ||

| Std = standard deviation | |||||

| S/No | Variable | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Years of using a smartphone | |||

| 1-5 years | 139 | 60.2 | ||

| 6-10 years | 46 | 19.9 | ||

| 11-15 years | 27 | 11.7 | ||

| More than 15 years | 19 | 8.2 | ||

| 2 | Hours spent using a smartphone daily | |||

| Less than 1 year | 18 | 7.8 | ||

| 4-6 hours | 64 | 27.4 | ||

| 1-3 hours | 115 | 49.8 | ||

| >6 hours | 34 | 14.7 | ||

| 3 | Frequency of checking phone notifications | |||

| Every few minutes | 39 | 16.9 | ||

| Every hour | 41 | 17.7 | ||

| Rarely or only when needed | 59 | 25.5 | ||

| A few times a day | 65 | 28.1 | ||

| Once or twice a day | 27 | 11.7 | ||

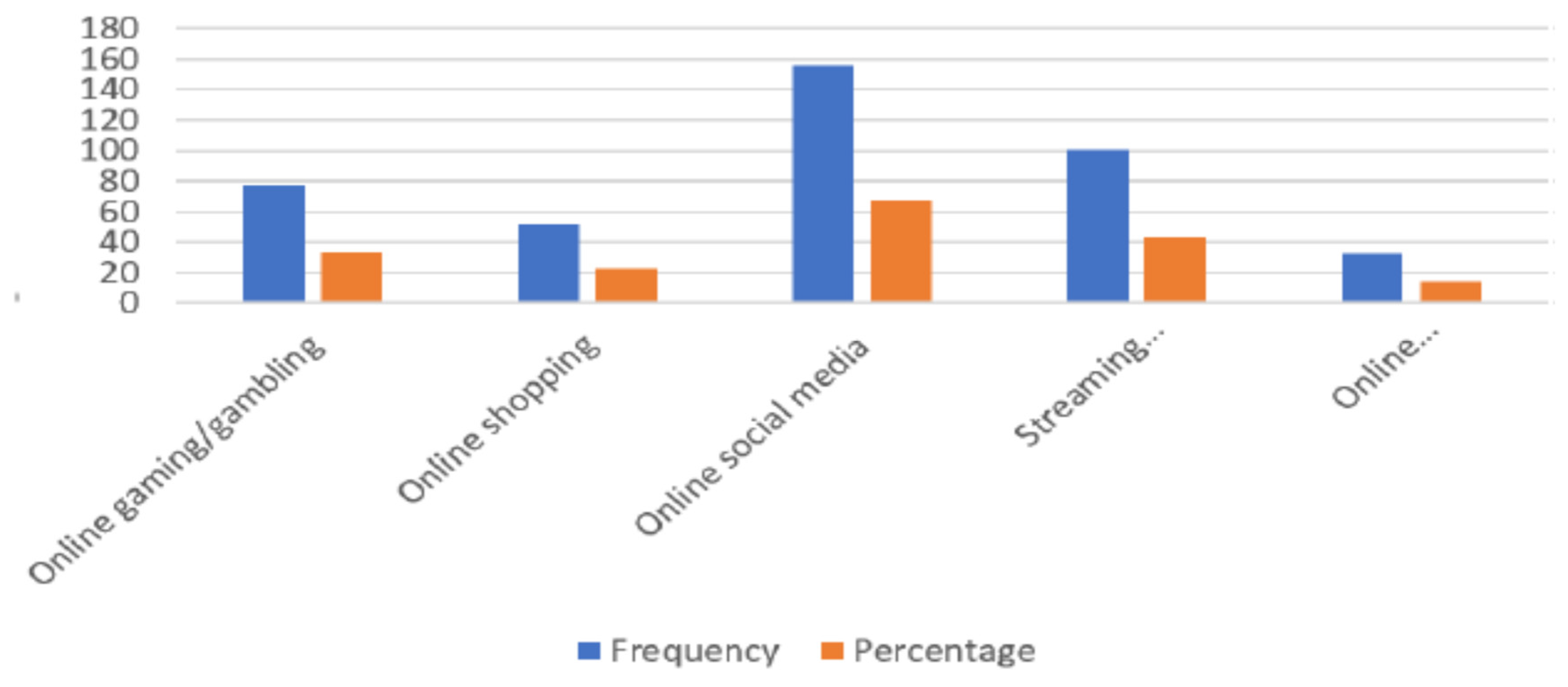

| 4 | Purpose of using smartphones | |||

| Online gaming/gambling | 77 | 33.3 | ||

| Online shopping | 52 | 22.5 | ||

| Online social media | 156 | 67.5 | ||

| Streaming (movies/ shows) | 101 | 43.7 | ||

| Online relationship | 33 | 14.3 | ||

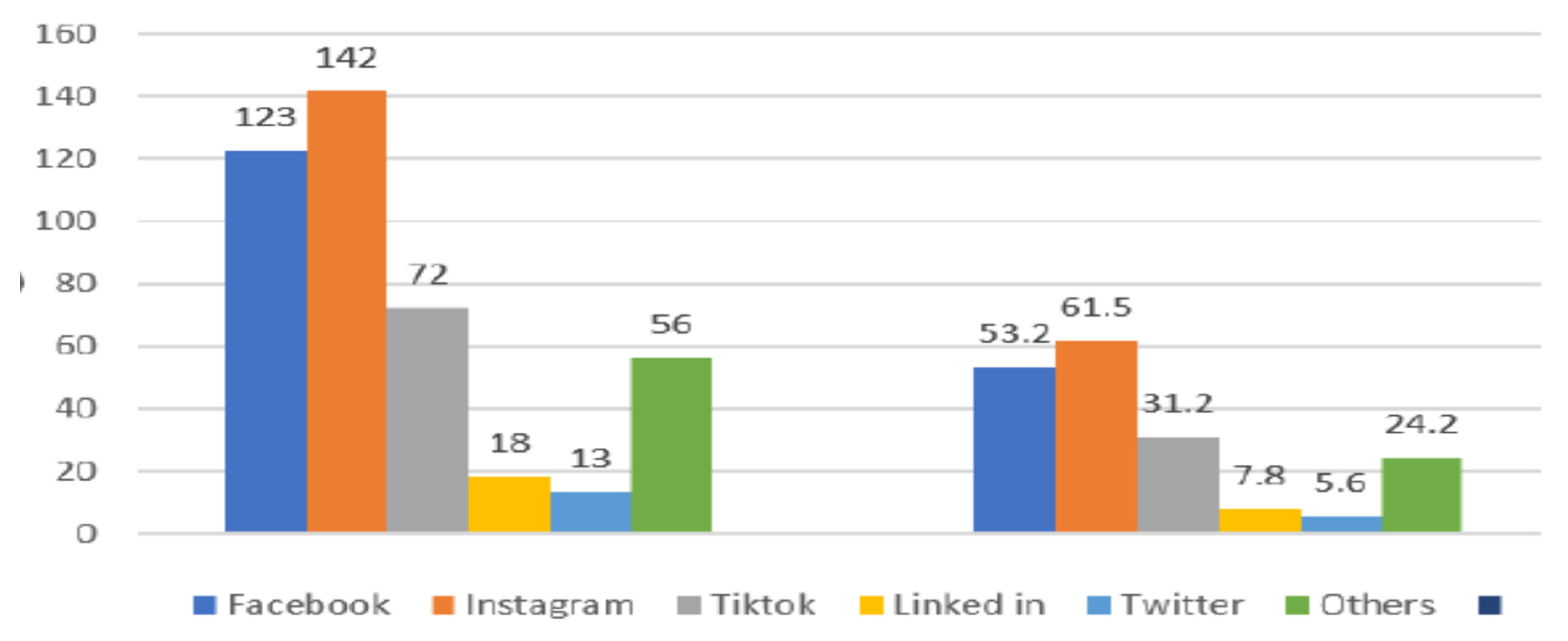

| 5 | Preferred social media platform | |||

| 123 | 53.2 | |||

| 142 | 61.5 | |||

| TikTok | 72 | 31.2 | ||

| Linked in | 18 | 7.8 | ||

| 13 | 5.6 | |||

| Others | 56 | 24.2 | ||

| S/No | Variable | Mild | Moderate | Severe | χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age Group | ||||||

| ≤17 years | 54 | 52 | 50 | 4.842 | 0.901 | ||

| ≥18 years | 20 | 27 | 28 | ||||

| 2 | Gender | ||||||

| Male | 30 | 30 | 26 | 1.392 | 0.499 | ||

| Female | 36 | 40 | 45 | ||||

| 3 | Religion | ||||||

| Hinduism | 65 | 59 | 64 | 7.469 | .280 | ||

| Christian | 3 | 5 | 2 | ||||

| Buddhism | 6 | 15 | 10 | ||||

| Islam | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | Ethnicity | ||||||

| Brahmin/Chhetri | 32 | 30 | 31 | 8.939 | .347 | ||

| Janajati | 29 | 27 | 30 | ||||

| Madhesi | 2 | 3 | 5 | ||||

| Dalit | 0 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| Others | 11 | 17 | 8 | ||||

| 5 | Type of Family | ||||||

| Nuclear | 41 | 45 | 44 | 2.633 | .853 | ||

| Joint | 26 | 27 | 29 | ||||

| Extended | 6 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| Others | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| 6 | Educational Level | ||||||

| Grade 11 | 37 | 42 | 38 | 0.329 | 0.898 | ||

| Grade 12 | 37 | 37 | 40 | ||||

| 7 | Father’s Educational Status | ||||||

| Cannot read and write | 1 | 4 | 7 | 11.242 | 0.339 | ||

| Can read and write | 15 | 13 | 13 | ||||

| Basic Level (1-8) | 13 | 21 | 20 | ||||

| Secondary (9-12) | 36 | 31 | 29 | ||||

| Bachelors | 3 | 6 | 7 | ||||

| Masters and above | 6 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| 8 | Mother’s Educational Status | ||||||

| Cannot read and write | 10 | 15 | 17 | 12.053 | .281 | ||

| Can read and write | 14 | 11 | 16 | ||||

| Basic Level (1-8) | 24 | 29 | 16 | ||||

| Secondary (9-12) | 23 | 20 | 20 | ||||

| Bachelors | 2 | 4 | 6 | ||||

| Masters and above | 1 | 0 | 3 | ||||

| 9 | Place of Resident | ||||||

| House | 34 | 38 | 42 | 1.159 | .979 | ||

| Hostel | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Rent (Room) | 36 | 37 | 33 | ||||

| Relative House | 3 | 3 | 2 | ||||

| 10 | Total monthly income of the family | ||||||

| Less than 20000 | 12 | 17 | 11 | 7.655 | 0.264 | ||

| 21000-50000 | 32 | 26 | 40 | ||||

| 51000-100000 | 18 | 27 | 17 | ||||

| More than 100000 | 12 | 9 | 10 | ||||

| S/No | Variable | Mild | Moderate | Severe | χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Years of using a smartphone | ||||||

| 1-5 years | 52 | 48 | 39 | 11.940 | 0.063 | ||

| 6-10 years | 7 | 15 | 24 | ||||

| 11-15 years | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||

| More than 15 years | 7 | 7 | 5 | ||||

| 2 | Hours spent using a smartphone daily | ||||||

| Less than 1 year | 7 | 4 | 7 | 16.013 | 0.014 | ||

| 4-6 hours | 26 | 15 | 23 | ||||

| 1-3 hours | 35 | 50 | 30 | ||||

| >6 hours | 6 | 10 | 18 | ||||

| 3 | Frequency of checking phone notifications | ||||||

| Every few minutes | 8 | 12 | 19 | 18.333 | 0.019 | ||

| Every hour | 12 | 10 | 19 | ||||

| Rarely or only when needed | 26 | 18 | 15 | ||||

| A few times a day | 23 | 24 | 18 | ||||

| Once or twice a day | 5 | 15 | 7 | ||||

| 4 | Purpose of using smartphones | ||||||

| Online gaming/gambling | 26 | 26 | 25 | 0.172 | 0.918 | ||

| Online shopping | 19 | 14 | 19 | 1.616 | 0.446 | ||

| Online social media | 51 | 52 | 53 | 0.176 | 0.916 | ||

| Streaming (movies/ shows) | 27 | 33 | 41 | 4.175 | 0.124 | ||

| Online relationship | 8 | 11 | 14 | 1.593 | 0.451 | ||

| 5 | Preferred social media platform | ||||||

| 39 | 39 | 45 | 1.106 | 0.575 | |||

| 46 | 47 | 49 | 0.205 | 0.902 | |||

| TikTok | 20 | 20 | 32 | 5.385 | 0.048 | ||

| Linked in | 1 | 8 | 9 | 6.395 | 0.061 | ||

| 4 | 6 | 3 | 1.049 | 0.592 | |||

| Others | 12 | 21 | 23 | 3.999 | 0.135 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).