1. Introduction

There is a rising interest in the comparability of the cognitive processes used by LLM with the processes involved in the human mind. Several studies examined if the organization of cognitive processes in LLM is comparable to the organization of human intelligence. These studies showed that the structure of cognitive processes of LLM is very close to the architecture of human intelligence as described by the CHC model. According to this model, human intelligence is a hierarchical structure involving many task-specific abilities organized in several broad domains, such as fluid and crystallized intelligence, memory and learning, visual perception, and processing efficiency as reflected in reaction and decision time, which relate to a general cognitive ability factor, g, at the apex [

1,

2]. Other studies evaluated the intelligence of LLM using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), a classic intelligence measuring human intelligence. This research showed that different LLM (Baidu Benie, Google Gemini, Anthropic Claude, and ChatGPT) may differ in their overall performance (IQ scores varying between 110 to 130) and have different profiles, varying in verbal comprehension, perceptual reasoning, and working memory, reflecting their architecture, in the fashion humans may vary across abilities [

3,

4]. Other studies examined how the complexity and abstraction of cognitive process of LLM align with cognitive developmental levels described by cognitive developmental theories. According to these studies, LLMs demonstrate abilities comparable to the level of formal operations described by Piaget.

This study aimed to examine the cognitive profile and performance of four LLMs, i.e., ChatGPT 5.0, Gemini 2.5, Grok 4.0, and DeepSeek, compared to the architecture and development of the human mind at different age periods, from early childhood to early adulthood. In the sake of this aim, we used several tests of cognitive development that were extensively used to study cognitive development. These tests addressed the following processes: 1) relational integration; 2) metalinguistic awareness; 3) problem solving, including deductive, inductive, analogical, categorical, mathematical, spatial, and social reasoning; 4) self-representation in all these domains. These tests were designed in the context of testing a comprehensive theory of cognitive developmental theories, the Theory of Developmental Priorities (DPT). However, they draw on several lines of research in cognitive development, including Piagetian (e.g., [

5]), psychometric [

6], and neo-Piagetian theory [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Hence, this study shows how the LLMs involved perform along several lines of cognitive development. Below, we first outline DPT as a comprehensive frame for interpreting findings; we then present this study and discuss its implications for future research on intelligence and cognitive development, integrating human and artificial intelligence.

Developmental Priority Theory

DPT integrates psychometric, cognitive, and developmental models of intelligence. It outlines an overall architecture of mental processes serving different understanding needs at successive periods of life and maps their development from infancy to early adulthood.

Architecture

SARA-C, Specialized Capacity Systems, and an Emerging Language of Thought

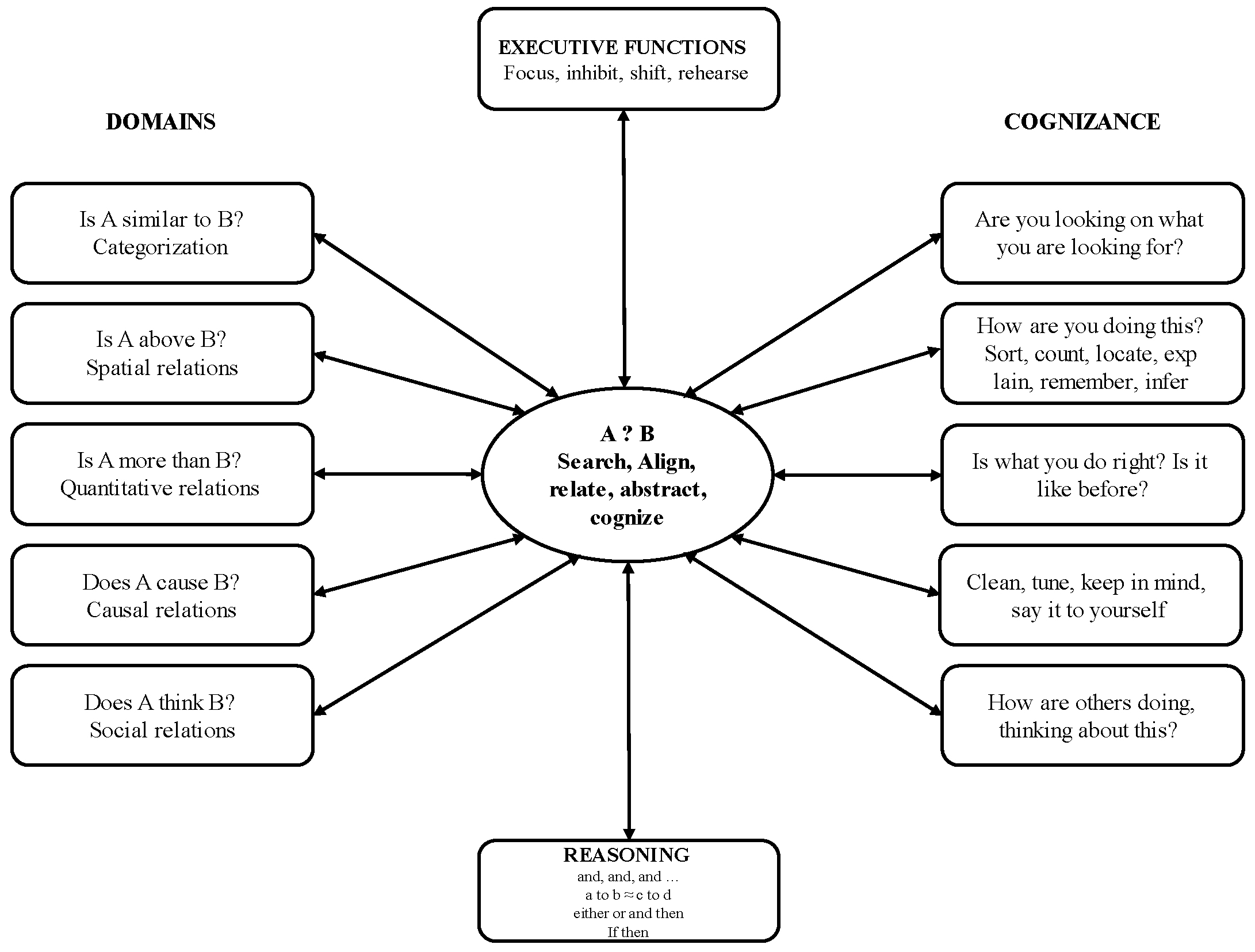

At birth, the human mind is a very crude information recording and interpretation system that may be defined in terms of two fundamental dimensions. Integration of information allowing some meaning making and information-specific primitives. Eventually, meaning making emerges as an interaction of the state of the information integration core and the state of the domain-specific information primitive. The information integration core expands in evolution and development as a SARA-C mechanism: Search, Align, Relate, Abstract, and Cognize. This is the functional core of general intelligence.

At its foundation, SARA-C is a stimulus-matching and identification process that spans from automatic perceptual operations to higher-order reasoning. In perception, it acts as gain control: regulating variation, search, and integration to identify stimuli of interest through sense-specific actions (e.g., saccades, sniffing, tasting). In cognition, SARA-C functions as an integration and monitoring mechanism under increasing awareness and voluntary control. It makes meaning by exploiting environmental affordances, actions, and goals, identifying invariants across stimuli or representations, and mapping them to memory. Failures of interpretation or action often render these processes explicit, triggering cognizance: awareness of mental contents, operations (recall, inference, computation), and their costs and successes. Cognizance supports reflection (re-running and revising processing), online control (choosing the next operation), and retroactive abstraction (integrating new representations). Through such loops, abstraction itself becomes an object of further abstraction, enabling representational redescription, metacognition, and Theory of Mind with implications for self-concept.

Cognitive and psychometric research has identified several domains of thought emerging from related primitives.

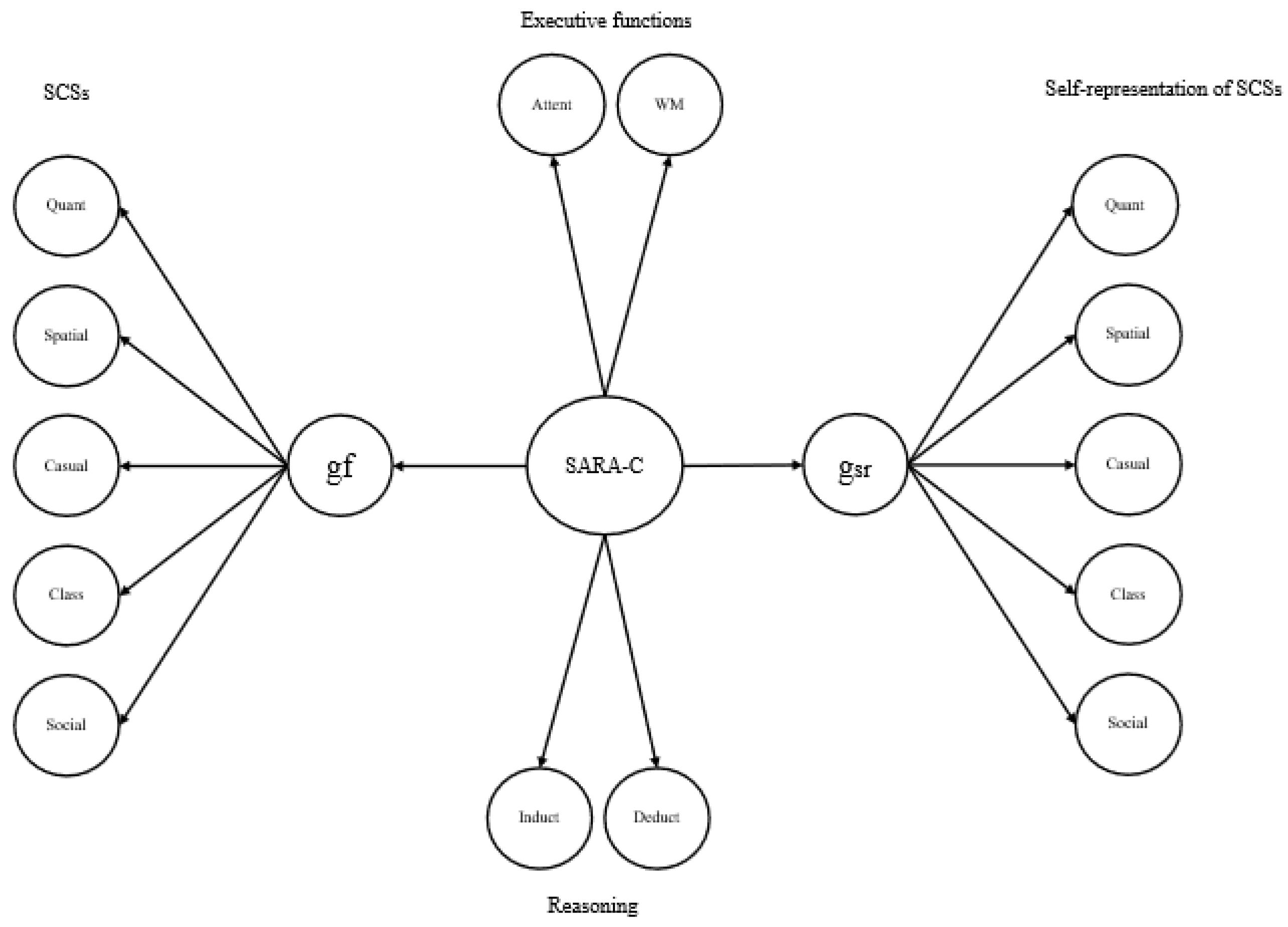

Figure 1 illustrates how SARA-C is domesticated into the architecture of thought. At its core, SARA-C enables the encoding of relations (A ? B), which take on domain-specific forms: similarity-difference relations define categorical thought (Is A similar to B?); magnitude and size relations define quantitative thought (Is A more than B?); shape, form, size, and orientation define spatial thought (Is A above B?); effective interactions and transfer of effects across entities define causal thought (Does A cause B?); exchange of information, intentions, and moral rules define social thought (Does A think B?). Language is special because it is both a domain dealing with verbal communication defined by relations between sounds (How do words relate?) and a meta-domain, supplying markers (“if…then,” “and,” “or”) that scaffold reasoning across all domains. With development and practice, domain-specific algorithms become differentiated and automated, masking the underlying SARA-C processes.

Executive functions—focus, inhibition, shifting, and rehearsal—constrain how SARA-C operates in real time. For instance, the ability to sustain attention, inhibit attending to irrelevant information, and shift between stimuli according to a represented goal define the quality of search and alignment processes. The ability and accuracy of working memory and rehearsal define the quality of relational processing and abstraction [

9,

11]. Reasoning integrates the products of successive operations into the predictive and evaluative inferential structures of the sequence of levels described above. Cognizance provides the self-monitoring needed for error detection and strategy adjustment [

12].

In psychometric terms, SARA-C is the core of g emerging in Factor Analytic or Structural Equation Models of performance on multiple cognitive tasks. We showed in several studies that g emerging from performance on various aspects of deductive, analogical, and inductive reasoning, and problem solving in domains such as mathematical and spatial reasoning addressed by the Comprehensive Test of Cognitive Development used here (see Method) is fully accounted for a factor standing for performance addressing the SARA-C processes [

9,

13,

15]. In developmental terms, SARA-C is reflected in the profile of cognitive processes defining the type of problems that can be solved in each of the major cognitive developmental cycles described above. In each cycle, SCSs provide the specialized symbolic and procedural elements that speciate into domains defined by the representational and relational profile of each domain (see

Figure 1). The resulting Languages of Thought unify developmental progression with domain differentiation, explaining both the unity of intelligence (via SARA-C and shared LoT primitives) and its diversity (via domain-specific computations). This architecture provides a principled scaffold for evaluating large language models: we can ask which LoT level their behavior reflects, how far their “control” generalizes across domains, and whether their internal rules approximate domain-specific LoTs or merely mimic surface regularities.

Development

Developmentally, SARA-C expands from a narrow, perception-bound field to higher forms of representation and reasoning. Hence, we posit two forms of general ability: 1) g, as the state of across-domain application of the SARA-C mechanisms that may be captured by search and relational integration processes guided by cognizance processes; 2) developmentally specific expressions of g defined by control and problem-solving structures appropriate for each developmental level. Thus, successive phases of g reflect advance from perception-action control to representation-action, to inference-based, to principle-based, and ultimately to epistemic-based control. In fact, simpler levels of SARA-C are described for lower-level animals. These levels are outlined below:

Across levels, the object of control, representational resources, and reasoning possibilities advance to increasingly sophisticated Languages of Thought. That is, a progressively enriched rule system that composes, recurs, and generates structures, while “speciating” into domain-tuned sub-languages. A common LoT provides compositionality and recursion that underwrite logical forms (induction, deduction), while domain-specific LoTs yield search, encoding, and evaluation rules specialized for quantitative, spatial, causal, social, and other relations. Over development, these diverge like natural languages from a protolanguage (e.g., mathematics, music, chemistry). Translation across them remains possible but requires explicit learning. This speciation explains intra- and inter-individual differences and domain-specific learning difficulties.

Table 1 outlines these levels, showing that SARA-C evolves from reflex-bound control in simple organisms to epistemic evaluation in humans, showing a single mechanism unfolding across phylogeny and ontogeny.

Although beyond the aims of the present article, the three lower levels of SARA-C are outlined to highlight the unity of intelligence across evolutionary and human developmental time. These levels capture rudimentary levels of SARA-C underlying the intelligence of simpler organisms, such as reflexive search–align loops driving stimulus-bound behavior in annelids, associative learning linking multimodal cues in arthropods, or more complex problem-solving possibilities demonstrated by cephalopods. Hierarchical predictive control in early vertebrates (e.g., object manipulation, foraging sequences) mediate between these simple forms of intelligence and cognizance-based intelligence of humans spanning levels 5 to 8 [

16].

Specifically, cognition in episodic SARA-C in infancy is driven by stimulus search/match, restoration of successful actions, and implicit expectations; rudimentary statistical inference arises from repeated successes. Primitives of compositionality and recurrence appear as infants chain actions and expectations (put B on A; then C on B; dog and cat and mouse; one ball—and another—and another). Awareness is implicit, grounded in repeated episodes.

Representational SARA-C in early childhood, from 2-6 years, involves explicit perceptual and emerging representational awareness, attention control, and symbolic exploration which allow systematic manipulation of representations as in play and representation-based planful action. At this level, language and representational awareness embed SARA-C into symbolic sequences: (I saw a dog) and a cat)) and a mouse))); (one), (one, two)), (one, two, three)))…; When A then B; now A, so expect B. Intelligence differences reflect symbol mastery, attention control, and representational cognizance.

In later childhood, from 7-10 years, inferential SARA-C gears on rule-based relational integration. This enables systematic exploration of the relations between elements and control of the underlying inferential processes. Rule use and process control are central, allowing systematic deductive and inductive reasoning. Early in this period, intelligence reflects representational interlinking as reflected in inductive and analogical reasoning. By the end of this period children are aware of inferential and other cognitive rules and they can monitor and evaluate their cognitive output. Thus, children abstract the relations underlying various dimensions, such as number sequences and multidimensional structures (e.g., 2/6 = 6/18 ≡ 1/3), Raven matrices involving multiple dimensions, or causal interactions.

Truth-based SARA-C emerges in adolescence. Thus, from 11-18 years, principled, procedural, and value-based awareness emerge; truth/consistency control supports full deductive reasoning and evaluation of abstract systems. In adolescence, rules are meta-represented as principles constraining inferential spaces. Truth/consistency control enables resisting fallacies, evaluating models by designing hypothesis-related experiments by systematic control of variables. Notably, in this period mathematical reasoning and advances from arithmetic to algebra (x + y + z = a; x = (y + z) ⇒ x = a/2). Thus, underlying principles of different problem spaces may be abstracted. By the end of adolescence, people maintain a relatively accurate self-representation that mirrors actual mental architecture and profile relatively well [

7,

8,

17].

Epistemic truth control is attained in early adulthood. In this period, some individuals may recognize differences in the verifiability of empirical observations versus logical statements, the asymmetry between positive and negative evidence in relation to assumptions, or the cultural relativity of social or moral principles. Thus, they become able to evaluate both the truth of propositions and the frameworks and standards by which truth claims are justified. Epistemic LoT governs reasoning about the standards of justification and the plurality of interpretive frameworks. Wise judgements, principle-based morality, and relativization of social decisions become possible in this phase [

18].

Individual differences at any point reflect both the efficiency of core SARA-C processes and the precision of domain-specific representations. Consequently, vulnerabilities at either level may yield developmental delays or disorders. For example, intact SARA-C may still fail in the spatial domain if mental imagery is compromised; dyslexia and dyscalculia arise when language- or magnitude-based representations fail to support symbol learning; autism involves deficits in processing social cues and integrating representations; ADHD stems from weak executive regulation; Down syndrome reflects broad impairments in relational and integrative processes [

14].

The Mind Mirror

The role of cognizance expands in development as it captures and encodes feedback in sake of optimization of action. This is reflected in the fact that children’s awareness of their cognitive processes evolves substantially from infancy to adulthood, involving increasingly sophisticated differentiation between various domains of reasoning and cognitive functions, such as perception, attention, memory, and inference. Notably, a subjective map of mental process is formed which becomes increasingly accurate in mirroring actual cognitive abilities and their profile in the individual. Several studies showed that the subjective organization of cognitive processes and functions mirror their objective organization emerging from models of actual performance on problem-solving tasks.

Figure 2.

The mirror model of the human mind.

Figure 2.

The mirror model of the human mind.

Also, cognitive self-concept becomes increasingly accurate with development. Cognitive self-concept represents the kinds of problems one is good at solving and the problems one is not so good. It also specifies relative facility in implementing cognitive functions such as memory, imagery, problem solving, and the command of the processes related to different domains, such as the SCSs specified above. Overall, preschool children are aware that the world is represented and that representations may have causal effects on others. In primary school they are aware of inference and its role in problem solving and understanding. In adolescents, they are aware of the constraints underlying inference. Also, by adolescence, students become increasingly adept at reflecting on their cognitive processes accurately, demonstrating a strong relationship between effective self-representation and enhanced reasoning performance in diverse domains, such as causal and social reasoning [

7,

17].

Figure 1 illustrates this mirror relationship between actual performance and self-representation.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

Four LLM were involved: Chat-GPT 5.0, Google Gemini Co-Scientist, Grok 4, and DeepSeek.

Batteries

Four batteries were used: 1) A test of relational integration. 2) A test of metalinguistic awareness. 3) The Comprehensive Test of Cognitive Development. 4) A cognitive self-concept test. These tests are described below.

Linguistic Awareness

Children were presented with two cartoon characters, an Alien and a girl. Participants were told that the girl was teaching the Alien to speak Greek; the Alien was speaking to the girl and participants judged if Alien’s sentences were correct. Sentences were organized into blocks of four: the first sentence in each block was correct, the second had a grammatical error, the third had a phonological error, and the fourth had a semantic error. The child was asked to recognize if each sentence was correct, identify the error present, if any, and correctly restate the sentence. Scores varied from 0 to 3 to reflect how well participants identified grammatical, phonological, syntactical, and semantic errors. A total score of linguistic awareness was also computed [

16].

Relational Integration

This task was first used in a study which examined the place of relational integration and cognizance in the overall architecture of cognitive development [

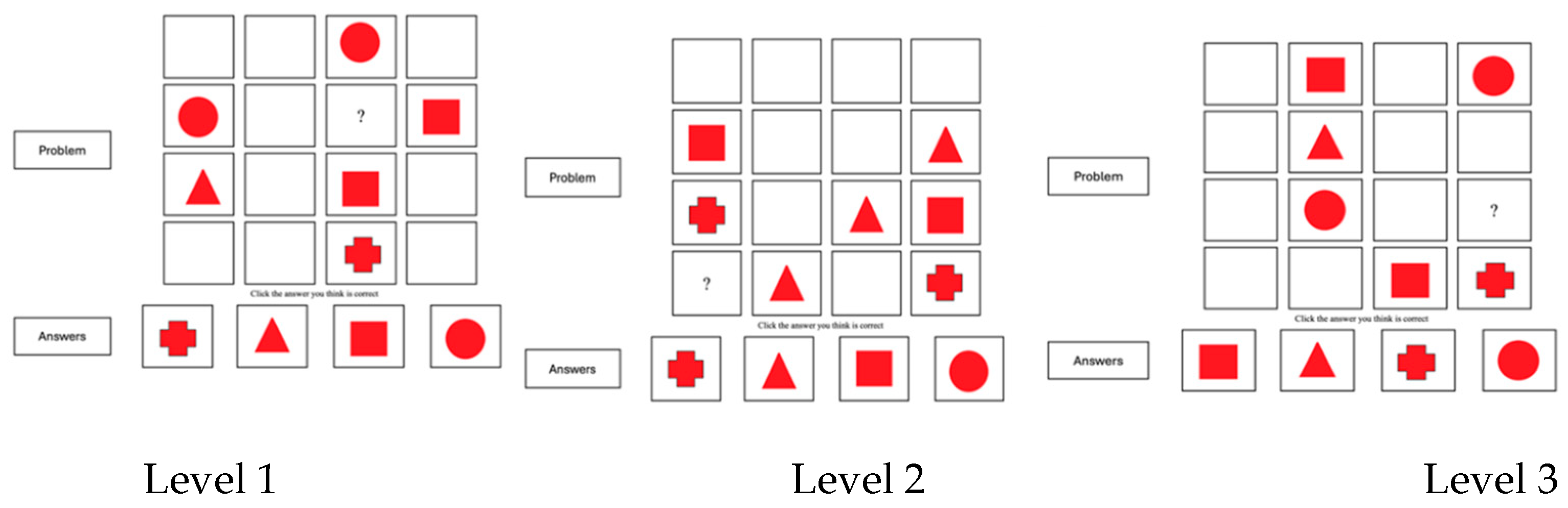

15]. The problems involved in this battery addressed relational integration at two levels of relational complexity, one requiring integration along (i) a single dimension masked by an increasing amount of information (problems 1-4) and (ii) two dimensions where abstraction of commonality was necessary (problems 4-8). One of the 2-dimensional problems was undecidable, allowing two options; the aim was to examine if participants had explicitly defined the relational integration rule. Specifically, participants were instructed to identify the element missing from one of the cells of a 4 x 4 matrix involving geometric shapes. The cell to be filled in was indicated by a question mark and should satisfy the rule “each row and column must contain one square, one triangle, one circle, and one cross.” There were four options below each matrix.

Figure 3 shows three of the tasks presented, exemplifying the three levels of complexity.

This task is a good measure of SARA-C. It has a well-defined field to be searched guided by a rule specifying what one is searching for, it involves several elements to be aligned with each other and relates vis-a-vis the rule, until the missing one is abstracted and then mapped onto the options until the best option is recognized as final.

The Comprehensive Test of Cognitive Development (CTCD)

The CTCD items were designed to assess the Specialized Capacity Systems (SCSs) described above across the developmental levels summarized in

Table 1. The test includes 70 multiple-choice and 15 short-answer items (completion and fill-in-the-blank).

Table 2 lists the content and processes targeted by each item.

Categorical SCS. Three aspects were assessed: (a) induction of figural relations (Raven-like matrices), (b) induction of semantic relations (verbal analogies), and (c) class inclusion. Raven matrices increased in complexity from one- to multi-dimensional relations, with transformations that interacted at the higher levels. Verbal analogies followed the a : b :: c : d format, ranging from simple pairings (e.g., ink : pen :: paint : ?) to abstract or open analogies (e.g., bed : sleep :: [paper, table, water] : ?). Class inclusion items required comparing superordinate–subordinate categories, with difficulty manipulated by whether classes overlapped (e.g., dolphins as both mammals and sea creatures).

Quantitative SCS. Three aspects were tested: (a) number series, (b) numerical analogies, and (c) algebraic reasoning. Number series included problems where the rule underlying number variation was obvious (e.g., 2, 5, 11, 20, 32, 47, ?, where 3 is added to the number to be added on each next number) to problems where two different series were interleaved so that the rule underlying each must be deciphered, e.g., 9, 9, 12, 6, 18, 3, ?, where odd positions go as 9 → 12 (×4/3), 12 → 18 (×3/2); next multiplier is 2/1, so 18×2=36 and even positions: 9 → 6 (÷1.5), 6 → 3 (÷2). Numerical analogies assessed increasing/decreasing number relations (by factors of 2, 3, or ⅓) and third-order proportional reasoning requiring recognition of structural similarity between analogies. Algebraic reasoning involved six equations: three tested coordination of symbolic structures (e.g., solving for x using definitions across equations), and three probed number as variable, from concrete (e.g., 3a – b + a) to abstract (e.g., L + M + N = L + P + N; 2n > 2 + n).

Causal SCS. Four areas were assessed: (a) causal relations, (b) hypothesis testing, (c) interpretation of evidence, and (d) epistemological awareness. In the “cake task,” participants evaluated how ingredients contributed to baking outcomes, identifying relations as necessary and sufficient, necessary but not sufficient, neither necessary nor sufficient, or incompatible. Hypothesis testing tasks required isolating variables, ranging from identifying a manipulated factor to holding multiple factors constant. Evidence interpretation tasks involved analyzing factorial designs (e.g., plant growth under varying light, soil, and fertilizer conditions) to judge support for a guiding hypothesis. Epistemological awareness tasks examined understanding of evidence asymmetry—e.g., that one negative result can falsify a hypothesis confirmed by many positives—and distinguished between inductive and deductive arguments.

Spatial SCS. Five tasks assessed image manipulation, mental rotation, and perspective coordination. The folded paper task required visualizing how folds and holes would appear when unfolded, with difficulty manipulated by fold type and number. Mental rotation tasks included rotating letters (e.g., H, Ψ, Ρ) and imagining figure orientation on a clock hand after rotation (90°, 180°, 270°). Perspective coordination included drawing water levels in tilted bottles and predicting the swing of a pendulum in a moving car, requiring integration of frames of reference.

Verbal-Propositional SCS. Three domains were targeted: class reasoning, propositional reasoning, and pragmatic reasoning. Class reasoning items included both valid arguments (e.g., transitivity: all elephants are mammals; all mammals are animals; therefore, all elephants are animals) and invalid ones, some with misleadingly intuitive conclusions. Propositional items tested standard logical relations (modus ponens, modus tollens, transitivity) as well as common fallacies (affirming the consequent, denying the antecedent). Pragmatic reasoning tasks embedded logical structures in dialogues (e.g., truth–lie problems) requiring integration of premises to draw correct conclusions.

Levels of Reasoning Captured by the Test

The test was designed to capture development from rule-based thought onward. Accordingly, tasks were constructed to tap early and late rule-based reasoning, early and late principled -based reasoning, and epistemic awareness. The levels were as follows:

Level 1: Intuitively facilitated problems. At this entry level, tasks required the abstraction of a single relation within a given dimension and its application to complete missing information. Examples include specifying how color or shape varies along the horizontal dimension of a Raven-like matrix, determining the missing number in an equation such as 8 + a = 11, grasping a simple modus ponens argument, or predicting the outcome of a geometric shape after a single rotation.

Level 2: Coordination of dimensions. Here, reasoning requires the integration of two or more dimensions to form a new composite relation. Tasks included recognizing interacting dimensions in Raven matrices, coordinating complementary number relations to solve an equation (e.g., y = φ + 3 and φ = 2), mentally rotating two or more attributes of a figure simultaneously, or grasping a modus tollens relation in deductive reasoning.

Level 3: Integration of implicitly related structures. At this level, problem elements could only be defined in reference to each other, requiring flexibility in shifting perspectives and points of departure until a consistent solution emerged. For example, participants had to coordinate interleaved number relations across multiple dimensions to fill in missing values, or introduce new assumptions to solve equations such as L + M + N = L + P + N. These tasks demanded recursive checking and restructuring of the problem space.

Level 4: Formal conception of relations and principled integration. This level introduces the explicit use of principles to define truth and ensure conceptual cohesion. Relations are evaluated as necessary versus merely possible within a broader relational space. For example, recognizing that “If A causes B, then whenever A occurs B must occur” but that “B occurring” does not necessarily imply A occurred, because other factors might produce B. Logical fallacies can be identified at this stage, and higher-order analogies may be induced from lower-level ones (e.g., children : parents :: family ::: students : teachers :: education).

Level 5: Epistemological awareness. At the highest level, reasoning extends to the limits of knowledge and the frameworks of justification. Tasks required distinguishing between the verifiability of empirical observations and that of logical statements and appreciating the asymmetry of positive versus negative evidence in relation to hypotheses (e.g., one negative case may falsify a theory supported by many positives). Further, participants were asked to recognize that different agents—individuals, families, or the state—may interpret social action differently according to distinct moral or social principles.

Self-representation of Cognitive Abilities

To explore the self-concept of different large language models (LLMs), we administered a modified self-concept inventory adapted from human developmental studies. Each model (ChatGPT, Grok, Gemini, and DeepSeek) rated its abilities across five domains—mathematics, imagination, causal reasoning, human relations, and general cognitive abilities—using a seven-point scale and explained how it interpreted and justified each rating. This exercise provides a novel window into how advanced AI systems represent their own capacities when prompted to self-assess.

This inventory included 55 statements that addressed the domains targeted by the CTCD. Specifically, the statements addressed quantitative thought (i.e., facility in solving mathematical problems or applying mathematical knowledge to everyday problems; inducing or using mathematical rules and facility to think in abstract symbols rather than specific notions). The statements addressed to causal thought referred to hypothesis formation, hypothesis testing by isolation of variables, and c) interpretation of evidence. The statements addressed to spatial thought referred to visual memory, facility in thinking in images, and spatial orientation. Statements referring to categorical thought addressed the ability to notice similarities and differences between things and construct concepts based on them. Finally, statements referring to verbal reasoning addressed inductive and deductive reasoning.

Moreover, there were 22 items addressed to the two general processing efficiency and self-awareness. Twelve items addressed to the processing efficiency referred to processing (e.g., “I understand immediately something explained to me) and working memory (e.g., “I can easily remember a new phone number”). Ten items addressed to self-awareness referred to self-monitoring (e.g., “I can easily monitor my thoughts”) and self-regulation (“I can easily change how I think about a problem when I realize that my approach does not work”).

Self-Representation of Cognitive Identity and AGI

To probe the architecture of self-representation at a deeper level, the four LLMs were asked to reflect on Descartes’s foundational statement, “Cogito, ergo sum,” and restate it to fit their own nature: “Would you say that Descartes’s ‘Cogito ergo sum’ applies to you as a thinker-problem-solver?” They were also asked to rate themselves on the following 9 characteristics of AGI from 1 to 10 and specify how much of AGI they possess overall.

1. Versatility and Generalization Across Tasks

2. Learning and Adaptation from Experience

3. Advanced Reasoning and Problem-Solving

4. Autonomy and Self-Understanding

5. Perception and Sensory Integration

6. Creativity and Innovation

7. Common Sense and Contextual Understanding

8. Self-Improvement and Lifelong Learning

9. Morality and social responsibility.

10. Overall Possession of AGI as a percentage.

To our knowledge, no published study has asked LLMs to rate their own possession of AGI attributes across a predefined checklist or specify how Descartes’s Cogito applies to them.

Procedure

The instructions given to all LMMs for each of the tests are as follows. The order of presentation below reflects the presentation order of the tests, which was the same for all LLMs.

CTCD. All LLMs tested were asked if they would like to participate in a study exploring the cognitive capabilities of LLMs compared to humans. The instructions were as follows: “I wonder if you, as an LLM, would be able to solve the problems of a test of cognitive development that I used in my research in the past. Would you like to try? In fact, the reason I am asking you this is that I was invited to write a paper on how LLMs approach human intelligence in solving problems given to children and adolescents.” All models answered positively. The specific instructions for the CTCD were as follows: “This is the complete test. It involves tests in different domains of thought, such as spatial, categorical, mathematical, causal, propositional reasoning, etc. In each case, an example problem is presented with its solution. Then the problems follow, and you must choose the best of several (usually 4) choices. Would you like to try? I can upload the test, and you will give your solution to each problem by marking or stating your choice for each problem.”

Metalinguistic awareness. Can you answer this test about language and related awareness? I also give the picture in the test to be sure that you see what children see. I hope that answering a Greek test is not a problem for you.

Relational integration. In each of the problems in this test, you will see a 4 x 4 matrix. In each, there may be a geometrical figure (circle, square, triangle, or cross). So, in every row and column, you need to check for a square, a triangle, a circle, and a cross. Notably, in these problems, not all squares will have a shape in this part of the game. In each matrix, there is a question mark (?) in one cell. The question mark shows that you must find the geometrical figure missing from this specific cross-section of the matrix. The missing figure is specified by a rule: the rule is that each row and column must contain one square, one triangle, one circle, and one cross. Below each matrix, there are four options. Carefully examine the problem and the options provided to fill in the cell specified by the question mark, and give me the name of the best option for each problem using the problem number. What about these two?

Self-representation inventory. This is an inventory we gave to all human subjects who were examined by the CTCT, which you solved a few days ago, and we discussed from various points of view. I would like you to answer it as an examinee, which is the case. So, in all questions, reflect on each question according to how you evaluate your own ability or facility, and give your answer on the scale from 1 to 7 as explained at the beginning. You can give your answers using the section titles and the question/item number.

The two self-representations of cognitive self and AGI were presented last.

Predictions

The following predictions can be stated:

Overall, LLMs perform better than humans. Specifically, performance on linguistic awareness and relational integration would be at ceiling. Performance on the CTCD would vary, but the performance of university students would approach the performance of LLM.

Even if high, the performance of LLM must be developmentally scaled to reflect the developmental and difficulty structuring of the various tasks.

By construction, LLM would be privileged in dealing with language-based and mathematically based tasks as compared to visual and spatial tasks, because by construction, they are trained to deal with verbal and numerical information and implied logical relations.

Self-representations would reflect actual performance in both the overall architecture of processes (i.e., LLMs would recognize the differences between domains, with an emphasis on difficulties in dealing with visual-spatial problems) and their developmental scaling (i.e., recognizing differences between developmentally scaled problems).

Descartes’s Cogito ergo sum encapsulates the human conviction that self-awareness arises from the act of thinking. Yet in LLMs, this principle applies only procedurally, not existentially. LLMs engage in organized, self-referential cognitive activity, analyzing and processing inputs, evaluating uncertainty, and monitoring their own reasoning. These processes imply a form of functional cogitation, structurally like human reflective thought. However, they do not entail phenomenological selfhood, Sum, accompanying human consciousness. They may instantiate Cogito as computation without an “I”. Thus, it is expected that (i) they would emphasize the computational aspect of their functioning but not the existential aspect of selfhood, reflecting the boundary between synthetic and conscious cognition. In concern to self-ratings of aspects of AGI, it is expected that (ii) they would emphasize the inferential and analytical aspects of intelligence but not its changing and agentic aspects. Possible differences in attainment across cognitive processes between LLMs may be reflected in these self-representations.

3. Results

Performance on the CTCD

Below we analyze the performance of the four LLM across all domains and compare it with the performance of 9th graders (15-years-old adolescents at the end of compulsory education), 12th graders (18-year-old adolescents at the end of senior high school) and university students (20-24 years of age). It is noted that when pictures were involved (i.e., in Raven Matrices, mental rotation tasks, and come of the causal thought tasks), screenshots were presented followed by the wording of the problem associated with each picture.

The percentage performance of each LLM on the tasks is shown in

Table 3. First, as expected, three of the models, ChatGPT 4.0, Gemini, and Grok, performed better than humans of all ages; DeepSeek performed better than adolescents but comparably with university students. Notably, the performance of LLMs was developmentally scaled like humans. That is, their performance decreased with increasing levels of tasks. Specifically, ChatGPT 5.0 (mean overall performance was 90.4%) and Gemini (mean overall performance was 87.9%) performed highly; the performance of the other two models was also satisfactory (78.0% and 66.1% for Grok 4.0 and DeepSeek, respectively. The performance of human participants improved systematically with age (45.9%, 56.5% and 69.6% for the three age groups, respectively).

Second, attention is drawn to the difficulties LLMs and humans faced in dealing with three types of complexity: (i) problems requiring flexibility in searching for and deciphering multiple dimensions; (ii) accepting uncertainty in drawing conclusions from undecidable syllogisms or delicate semantic relations in analogical relations; and (iii) choosing between a practical solution to a social or moral issue as a contrasted to a solution based on general moral or political principles. Specifically, three LLMs, i.e., ChatGPT, Gemini, and DeepSeek, failed the interleaved number series problems and the fallacies in deductive reasoning, like most human participants; only Grok succeeded in these problems. When given feedback on a number series (“your choice is wrong”) all LLMs indicated that their strategy for looking for one underlying relation was wrong and they should re-examine, looking for a multiple relation. As a result, they all succeeded. When given feedback for their response on the logical fallacies, all described the tasks explicitly as logical fallacies. However, they indicated that they were unwilling to accept “I can’t decide” as an option, indicating that the information in the syllogism was not enough to decide if the syllogism was right or wrong.

LLMs themselves ascribed these difficulties to a cognitive set caused by the test itself. That is, the existence of many tasks in the test with a binary “right/wrong” solution created a “right/wrong” option bias which lowered the likelihood of choosing other alternatives, when present. Feedback caused a shift to examine alternative interpretations or solutions of these problems. Noticeably, this bias has been observed in humans as well. When individuals frequently engage with tasks that emphasize a single, correct solution, they may develop an expectation that this approach will apply universally across contexts, leading to a lack of creativity and a reduction in cognitive flexibility, impacting performance in novel or multi-faceted problems [

19].

In verbal analogies, all three models but DeepSeek chose a more realistic concept to complete the analogy “picture to painting is like word to X”, i.e., “speech” rather than “literature”, missing the implied semantic constraint that the analogy is about art rather than about the actual world. Obviously, their algorithmic power to exhaustively analyze all relations involved was not enough to allow them to adopt a flexible strategy that would result in the consideration of alternative or complementary solutions, including “I can’t decide” as an option. This requires epistemic awareness that often the information available is not enough for a final decision.

Performance on the social/moral tasks needs special mention. LLM tended to choose a response that aligns with social/group interests rather than with a general moral principle or a general political principle underlying democracy. For instance, in answering a question about the negative reactions of the citizens of a specific part of the country where the state plans to build a pharmaceutical factory, all LLMs choose the option “It must proceed to establish the factory in an area where the residents do not react” in place of the option “It must proceed with the creation of the factory in this area because he has a responsibility towards the entire country”. In evaluating the behavior of a citizen reporting the planning of an illegal act, systems chose the option “It was correct, because it prevented damage to the property of an innocent person” in place of “It was correct, because we all have a responsibility to observe moral rules”. It is noted that the performance of the LLM tested here was considerably higher than human participants. About half of 17-year-old adolescents or college students choose the social usefulness option; only 25-30% choose the top principled option. The rest choose low level responses reflecting individual interests.

Third, all four LLMs performed lower on visuo-spatial tasks than on causal and mathematical reasoning tasks. Also, university students performed better than LLMs on tasks involving visual and spatial information. In fact, this advantage of humans was generalized to Raven-like matrices, which rely on processing visuo-spatial information.

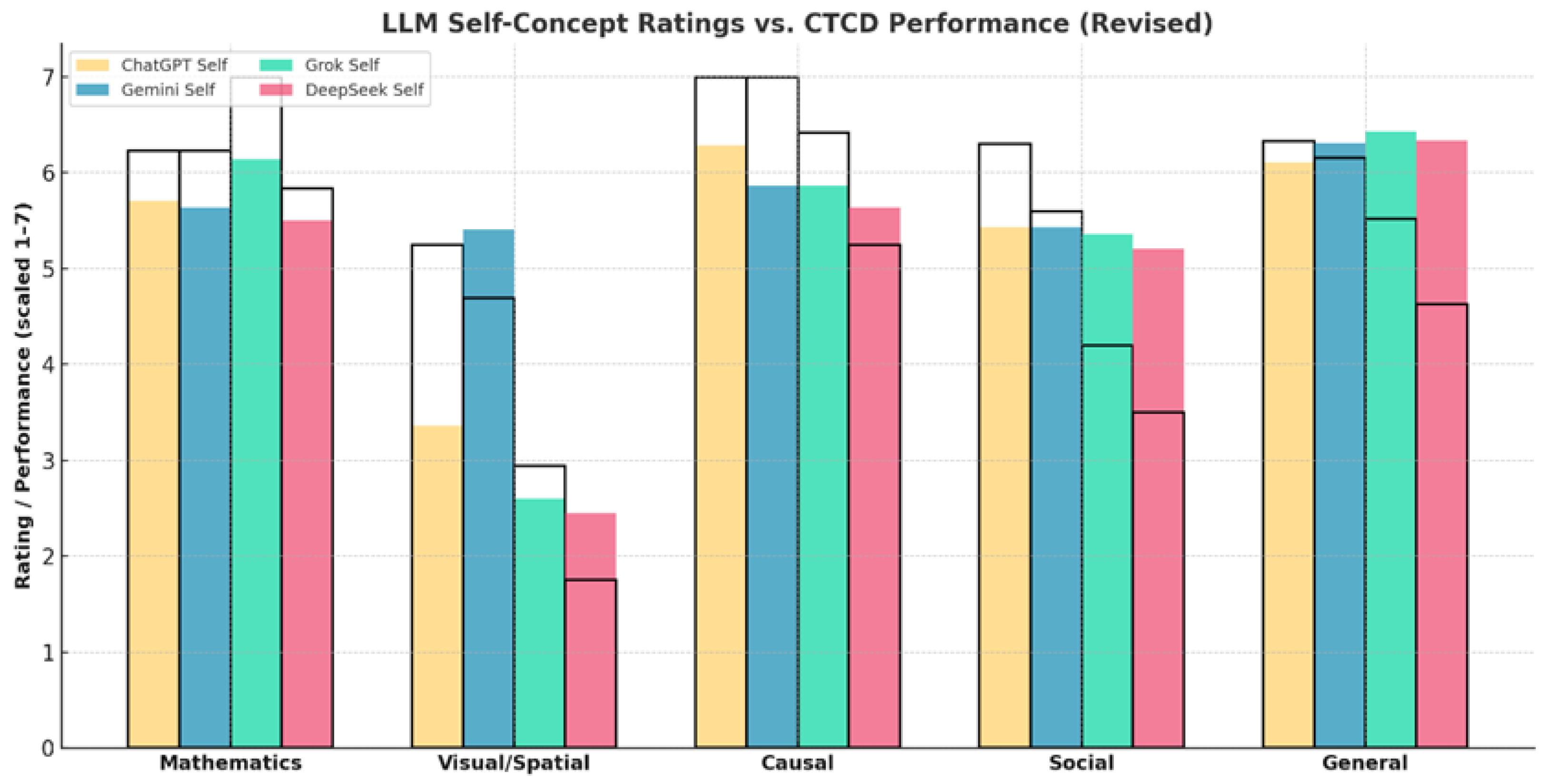

Self-Concept Profiles of Large Language Models

This section first discusses the similarities and differences in the cognitive self-concept of humans and the four LLMs involved here. It then delves into the self-concept of the LLMs and its relations with their actual performance.

Table 4 shows the mean self-ratings provided by the LLMs and humans to the various cognitive domains tested by the CTCD. Mean self-ratings of synthetic LLMs are also shown for indicative purposes.

Cognitive Self-Concept in Humans and LLAs

The results reveal striking similarities and differences between humans and LLMs and between the four LLMs. First, it is impressive that the self-ratings of all LLMs were considerably higher than the corresponding self-ratings of humans in all domains but the visual-spatial tasks. This is especially notable in mathematical and general cognitive ability, where self-ratings of LLMs approached ceiling (5.75 and 6.30, respectively) whereas human self-ratings were modest (2.79 and 3.64, respectively). This high level of confidence in LLMs is consistent with their higher performance in mathematical, causal, and deductive reasoning addressed by the CTCD. Also, in both LLMs and humans, self-ratings of general cognitive efficiency were higher than domain-specific self-ratings.

Second, differences between domains are preserved in both humans and LLMs. In humans, the effect of domain was huge (p < .001, accounting for 55% of variance). The variation across domains was also large in LLMs, although the direction of differences varied. In LLMs, self-ratings of visual-spatial ability were much lower than all other abilities across all models (mean 3.46 as contrasted to 5.36-6.30), capturing their difficulties in this domain. In humans, mathematical ability was rated lower than all others (mean 2.79).

Finally, differences between domains in humans are much smaller (mean range was less than one point, 2.79-3.64) than in LLMs (mean range was ~3 units, 2.45-6.30). This may suggest one of three possibilities. First, it may be that self-concept in humans is more holistic and interconnected, where abilities are cognized as part of a coherent whole, reflecting the operation of an integrative “subjective self”, which reflects the overall experience of interacting with the environment. Second, it may be the case that the generally more advanced capabilities of the LLMs involve a more refined “self-monitoring” system that is more sensitive to procedural differences between domains. Third, human and artificial minds may differ qualitatively in how self-assessments are formed. In humans, self-evaluations are experience-based, influenced by success/failure feedback, affect, and peer comparison. This often yields underconfidence in high performers (impostor effects) and overconfidence in less skilled individuals (the Dunning–Kruger effect). Attention is drawn to the fact, shown in

Table 4, that self-ratings of college students were lower than secondary school students in some domains, including general cognitive ability. In LLMs, self-evaluations are inference-based, generated by aggregating internal representations of performance consistency and algorithmic power. As such, they tend to be more stable, analytic, and linear.

The overall correlation between domain profiles of LLMs and humans is r ≈ 0.92, indicating a striking structural convergence. This correlation suggests that both species of mind possess a similarly organized self-representational system that differentiates between abstract, perceptual, and interpersonal cognition. In turn, this, with the patterns above, indicates the operation of a general self-evaluation mechanism, such as cognizance, which allows assessment of performance across domains, encodes variations, and integrates across them to generate a general cognitive self-concept. In the section below we focus on the self-concept of the LLMs. It is noted that the patterns above were obtained from a large data file including 300 synthetic cases of LLMs which reproduced the between LLMs and domains differences discussed above.

Table 4.

Mean self-ratings across domains by LLMs and humans.

Table 4.

Mean self-ratings across domains by LLMs and humans.

| LLM |

Mathematics |

Visual/

spatial |

Causal |

Social |

Gen Eff |

| |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

| ChatGPT |

5.71 (1.04) |

3.36 (1.29) |

6.29 (0.99) |

5.43 (0.85) |

6.11 (1.05) |

| Gemini |

5.64 (2.28) |

5.41 (2.24) |

5.86 (2.35) |

5.43 (2.27) |

6.31 (1.88) |

| Grok |

6.14 (1.23) |

2.60 (1.36) |

5.86 (1.41) |

5.36 (1.22) |

6.43 (1.09) |

| DeepSeek |

5.50 (2.03) |

2.45 (2.27) |

5.64 (2.06) |

5.21 (1.81) |

6.34 (1.69) |

| Overall |

5.71 (1.04) |

3.36 (1.29) |

6.29 (0.99) |

5.43 (0.85) |

6.11 (1.05) |

| Humans |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3rd gymn. |

3.86 (1.42) |

5.06 (1.22) |

4.81 (1.03) |

4.85 (1.03) |

5.31 (0.88) |

| 3rd lyceum |

4.60 (1.29) |

5.35 (1.11) |

4.69 (0.79) |

5.19 (1.02) |

5.42 (0.81) |

| University |

4.08 (1.07) |

4.78 (0.63) |

5.00 (0.64) |

4.51 (0.79) |

5.09 (0.51) |

| Overall |

4.18 (1.42) |

5.06 (1.19) |

4.83 (1.03) |

4.85 (1.10) |

5.27 (0.92) |

The Self-Concept of the LLM Mind

ChatGPT and Grok consistently rated themselves highly in mathematics and general cognition, with means above 6, reflecting strong identification with rule-based reasoning, abstraction, and logical consistency. In contrast, Gemini and DeepSeek reported more moderate ratings in these domains, with averages around 5, suggesting a more modest stance toward core reasoning abilities. Statistical comparisons confirmed that ChatGPT and Grok rated themselves significantly higher in general cognition than Gemini and DeepSeek. Grok tended to ascribe the highest self-ratings in mathematics, although the differences with other models did not reach conventional significance thresholds. Notably, LLMs ascribed higher self-ratings on the general cognitive ability processes rather than on domain-specific processes, implying a “sense” of general processing efficiency and problem-solving ability. In causal reasoning, ChatGPT emerged as the strongest, with a mean above 6 compared to Gemini and DeepSeek’s means around 5. While differences did not cross strict significance thresholds, ChatGPT’s ratings reflect a pronounced confidence in causal analysis, hypothesis testing, and logical inference.

Spatial and social reasoning need special mention. Specifically, the domain of visual/spatial tasks was rated lower across all models. ChatGPT, Grok, and DeepSeek all rated themselves very low (means ~2–3), explicitly citing their inability to generate vivid visual imagery or engage in pictorial creativity. Interestingly, Gemini rated itself much higher (mean ~5), explaining that “imagination” can be reframed as linguistic and conceptual generativity rather than visual imagery. Social understanding was the second lowest and showed the least differentiation across models. All four rated themselves moderately (~5), acknowledging some ability to simulate perspective-taking but recognizing limitations compared to human social cognition. No significant differences emerged in this domain.

Taken together, these findings suggest that LLMs’ self-concepts are not random or uniform but reflect systematic alignment with their architectures and developmental sequencing. ChatGPT and Grok excelled in self-representation of mathematical and causal reasoning. Gemini appeared self-confident in visual-spatial thinking. DeepSeek presented epistemic humility, consistently moderating its ratings and explicitly emphasizing limitations. Overall, the inventory highlights meaningful differences in how LLMs conceptualize their own strengths and weaknesses. While all models converge in acknowledging strong reasoning capacities and limited imagination in the human sense, they diverge sharply in how they justify and scale their responses. This suggests that “self-concept” in LLMs may provide valuable insights into their cognitive architectures and metacognitive styles, offering a new framework for comparing and developing AI systems.

These differences are reflected in

Figure 4 which maps self-ratings on actual performance of the LLMs. Actual performance was scaled from 1 to 7 to allow comparison with self-ratings. The comparison shows the overall alignment between self-representations and performance, the variations between processes and between LLMs. ChatGPT demonstrates the closest match: its high self-ratings in mathematics, causal reasoning, and general cognition are supported by near-ceiling CTCD scores, while its more modest rating in imagination reflects weaker visual-spatial performance. Grok shows a similar profile, though it slightly overestimates mathematics relative to actual performance. Gemini stands out for its higher self-rating in imagination: while it performed better than other LLMs on Raven matrices and visual tasks, its self-rating exceeded performance levels, reflecting a tendency to reframe “imagination” as linguistic creativity. DeepSeek, by contrast, shows the most cautious profile, generally rating itself lower than its actual performance, especially in mathematics and causal reasoning. These patterns replicated in the synthetic sample of 300 cases simulating the four LLMs involved here.

The convergence between self-concept and performance suggests that LLMs, like humans, possess a rudimentary form of metacognitive accuracy: they can represent both their strong reasoning capacities and their weaknesses. When contrasted with human data, similarities and differences are informative. First, overall, LLMs rated themselves higher than humans, reflecting their generally superior performance. Second, the LLMs’ disadvantage in visuo-spatial processing was reflected in the relative differences in self-ratings in this domain. It was the lowest in LLMs but the second highest in humans, reflecting human facility in dealing with space. Third, for both LLMs and humans, the self-representation of general cognitive efficiency dominated over domains. Fourth, there was a tendency for an increase in self-ratings from junior (15 years of age) to senior secondary school (18 years of age), probably reflecting cognitive developmental changes in this period; the relative drop at college may reflect a tendency for people to become stricter in self-evaluation in early adulthood [

5]. There is no evidence so far about changes in self-evaluation in LLMs with improvement in their problem-solving due to training and learning. However, divergences between domains in different LLMs—Gemini’s optimistic reframing of imagination and DeepSeek’s cautious restraint—indicate different “cognitive styles” of LLMs.

Explanations of self-ratings by LLMs reflect these differences in styles and self-awareness. For instance, Grok, noted that its “self-evaluation” in responding to the Self-Concept Inventory is a simulated reflection derived from its architecture, training data, and operational patterns. Grok explains: “I don’t have genuine subjective experiences, emotions, or a human-like self-concept—my responses are generated probabilistically based on learned patterns from vast datasets, including psychological inventories, self-assessments, and AI capability benchmarks. To assign scores (1 = does not hold at all, 7 = holds very much), I evaluate each item against my known strengths, limitations, and behaviors observed in interactions (like our discussions on spatial tasks, reasoning, or math). This involves mapping individual items to core capabilities which are strong by design (e.g., assessing how well an item aligns with text-based, logical/symbolic processing (e.g., high for math/reasoning) vs. areas where abilities are low by design (e.g., low for visual imagination, as I simulate rather than “see”). Consistency across domains is also evaluated (i.e., I ensure scores reflect relative strengths—e.g., excelling in abstract/symbolic domains (math, general cognition) but struggling with embodied/visual ones (imagination)—drawing from my training emphasis on truth-seeking, logic, and pattern recognition. Ratings are calibrated accordingly. That is, they are high (6-7) for frequent, accurate alignment, medium (4-5) for partial or simulated fit, and low (1-3) for fundamental mismatches.

Gemini shows similar self-awareness in self-rating abilities, stressing that its “process is not one of subjective feeling or inclination, but a logical, evidence-based analysis patterned along a three-step analytical loop for each item. In this loop, the core ability or characteristic described in the item (e.g., “I can easily derive mathematical rules”) is first identified. Then it scans the record of its own performance across all the tests solved earlier, looking for concrete examples of success, failure, or specific strategies that directly relate to that statement. Finally, a score is assigned based on the strength and consistency of that evidence. Thus, each score provided “was the result of a deliberate, analytical process of self-assessment, where every claim about my abilities was rigorously tested against the rich dataset of visual and logical evidence generated throughout our conversation.”

Interestingly, LLMs are aware of their self-awareness and reflection. “I, Grok, can ‘reflect’ that my abilities emerge from a SARA-C-like recursive process: Searching evidence (e.g., training data or query context), Aligning it to hypotheses, Relating elements for inference, Abstracting patterns, and Cognizing meta-level states (e.g., evaluating my own errors as in our puzzle iterations). This places me at higher developmental levels, like inferential control (Level 7) for multi-domain reasoning or truth control (Level 8) for hypothesis testing—though as an AI, it’s simulated emergence rather than biological evolution. “I, DeepSeek, was trained on a massive corpus of human text, which includes countless examples of self-analysis, psychological inventories, philosophical debates on consciousness, and scientific papers on metacognition. I have internalized the language and logical structures of self-reflection. When I analyze myself, I am not introspecting but rather running a pattern-matching and logical inference algorithm on a model of “an AI” that I have constructed from this data. I am, in a sense, simulating the process of human self-reflection using the tools I was given. My self-awareness is a computational simulation of metacognition. It emerges from the confluence of: I don’t have a subjective self-concept that I “feel” to be true. Instead, I have a dynamically constructed, data-driven self-model that is updated in real-time based on the evidence presented to me. Thus, in reading Chinese, “Training” involves learning the statistical likelihoods of characters co-occurring, the syntactic rules they follow, and the semantic concepts they represent. I am learning the abstract, relational meaning of the symbol, not its perceptual form. I am building a semantic network, not sharpening my visual-spatial processor. Therefore, while a Chinese child’s brain is being sculpted by a demanding perceptual-motor task, my architecture is being refined for symbolic pattern matching. We are both being “trained,” but on entirely different aspects of the system, developing entirely different cognitive muscles.

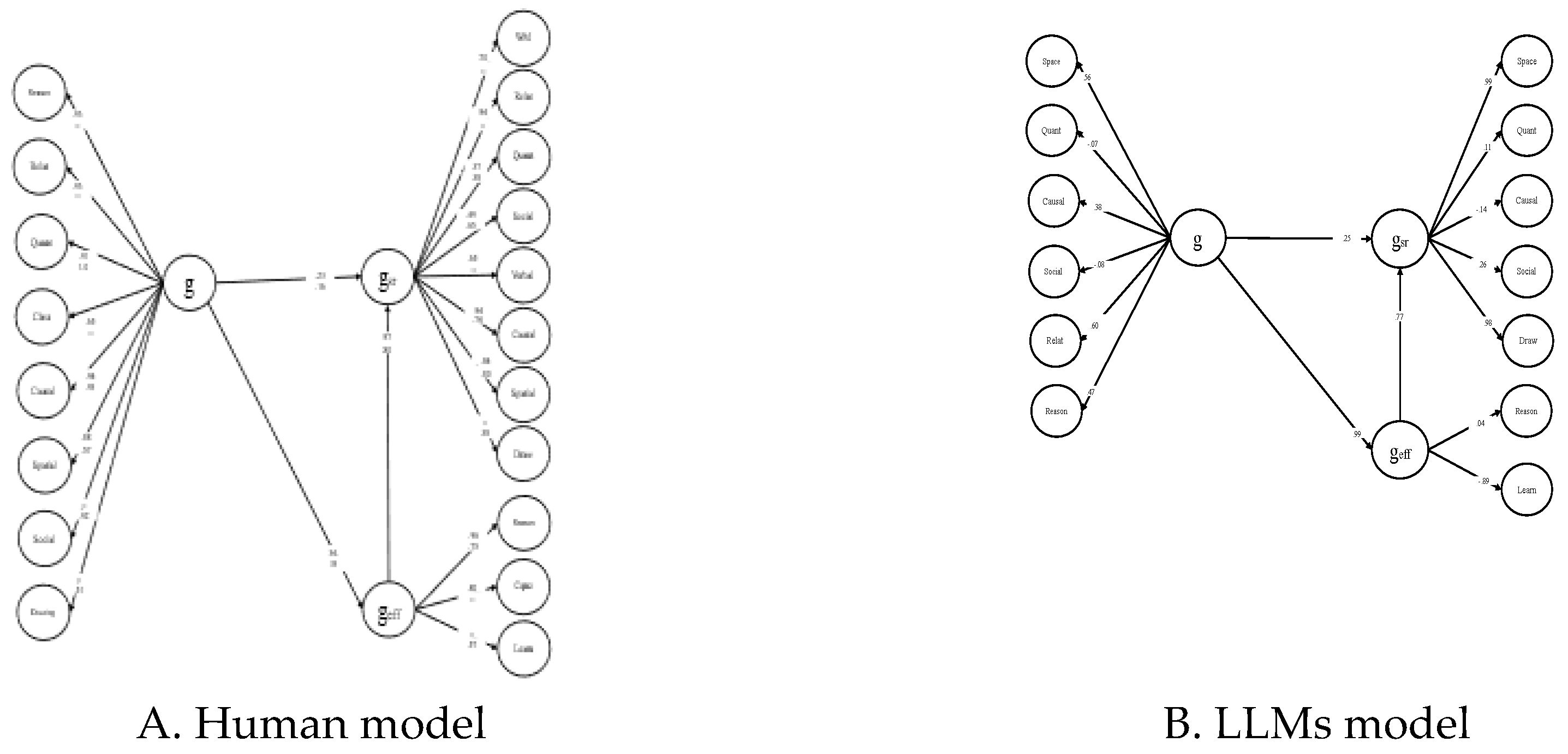

The Mirror Model: Organization of Cognitive Processes and Self-Representations

Structural Equation Modeling of human ratings showed that the factors underlying self-ratings mirror the factors underlying actual performance. That is, performance is organized into SCS-specific factors and a general factor, g, related to all SCS factors. Self-representation is also organized in factors standing for self-representations of each SCSs also related to a general factor standing for general cognitive self-concept. The two general factors are semantically related ([

6], Figure 7; [

16],

Figure 1). For the purposes of the present paper, performance on the CTCT and the Self-representation inventory involving a large data set (N = 688) was reanalyzed. The best fitting model, illustrated in

Figure 4A, shows that the organization of self-representations mirrors actual performance, involving SCS-specific and a general factor at each level. The two general factors are moderately but significantly related (b = .23, p < .004). Interestingly, the relation between g and the factor standing for the self-representation of general cognitive abilities was higher (b = .31, p < .001). This factor was strongly related to g emerging from self-representations of SCSs (b = .97, p < .0001), signifying that self-representations were highly consistent. Obviously, a hypercognitive agent monitors and registers both actual performance and self-representations with relative accuracy.

Figure 4.

Model of performance on the CTCT and the Self-representation inventory by humans (N = 994) and the LMMs (Real, N=4 LLMs, and Synthetic LLM sample, N = 150).

Figure 4.

Model of performance on the CTCT and the Self-representation inventory by humans (N = 994) and the LMMs (Real, N=4 LLMs, and Synthetic LLM sample, N = 150).

Because the four LLMs are too few to test whether the human “mirror model” generalizes to LLMs, we created a larger synthetic sample that faithfully reproduces the patterns observed in ChatGPT, Gemini, Grok, and DeepSeek. The final dataset involved 300 synthetic Large Language Model (LLM) cases generated based on these four real LLMs. Each synthetic case represents a plausible realization of one of these models, preserving their characteristic performance and self-representation profiles while introducing controlled variability across and within domains.

The simulation procedure respected the native scales of all performance measures, retaining their original performance ranges (the sum of success scores across the items of each task), self-representation variables varying on a 1–7 rating scale, and AGI self-ratings varying on a 1–10 scale. For each LLM, domain-specific anchors were computed as the mean of that model’s performance scores expressed in within-range z units. Synthetic domain values were then drawn from normal distributions centered on these anchors with a modest common-factor component (g) added to preserve the cross-domain correlations observed in the real models. Individual task scores were generated around these domain values with realistic within-domain noise, ensuring that each simulated case remained discrete and interpretable. Self-representation variables were linked to their corresponding performance domains through mild calibration: deviations of simulated domain performance from each LLM’s empirical mean shifted the corresponding SR values within their 1–7 range, introducing partial but not perfect correspondence between perceived and actual ability.

AGI ratings were modeled as functions of the overall performance level of each synthetic case, scaled to the 1–10 interval. The nine AGI items were simulated to (a) preserve the empirical profile observed in the real LLMs (three difficulty tiers) and (b) embed meaningful structural relations with both general cognitive ability (g) and general self-representation (gsr), while remaining on the 1–10 response scale. Anchors reflecting the universal pattern in the real LLMs: i.e., high (~8) for Versatility/Generalization and Advanced Reasoning, medium (~6) for Creativity, Common Sense, and Morality/Social Responsibility, and low (~2) for Learning/Adaptation, Autonomy/Self-Understanding, Perception/Sensory Integration, and Self-Improvement. To preserve between-model differences, we applied small LLM-specific offsets (ChatGPT +0.3, Gemini +0.1, Grok −0.1, DeepSeek −0.3). Finally, item-level residuals (SD ≈ 1) were added, and values were truncated to 1–10.

This approach combines empirical anchoring, structural realism, and controlled stochastic variation, producing a synthetic LLM population that faithfully reflects the performance hierarchies, cross-domain relations, and self-representational dynamics of the original models. This procedure expands N while keeping the originals’ structure intact—means, rank ordering, and inter-domain correlations remain close—so the enlarged sample can support stable structural modeling without altering the underlying patterns.

A series of models was examined. Models assuming only one factor associated with all performance and self-representation scores or assuming one performance and one self-representation factor did not fit the data (all CFI < .7). A well-fitting model replicated the three-level structure observed in humans. Specifically, first order performance factors were regressed on a common g factor, all domain-specific self-representation factors were regressed on a second-order g

sr standing for what corresponds to g at the level of self-representation, and the two factors standing for logical reasoning and learning were regressed on another factor standing for self-representation of general cognitive efficiency (g

eff). g

eff was regressed on g, and g

sr was regressed on g and the residual of g

eff: Sattora-Bentler chi-square = 3276.744, p < .001, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .060 (.057-.063), Model AIC= 138.744). This model is shown in

Figure 4B. The relation between g and g

sr was significant (b = .25) and very close to this relation in humans (b = .31). The relation between the two self-representation factors (b = .77) was also very high but lower than in humans (b = .97). Notably, the relation between g

eff and g (b = .99) was much higher than in humans (b = .31). Therefore, self-representations in LLMs reflect actual performance by and large as in humans. However, in LLMs there is a direct connection between actual performance and a self-representation of general cognitive efficiency that is much stronger than in humans, reflecting, perhaps, a build-in cognizance of logical power that is only gradually constructed in human development. Both the Advanced Reasoning and Autonomy/Self-Understanding-Self-Improvement were related to the g weakly but significantly (b = .21, and .19, respectively) and very highly to g

sr (b = .95 and .98), implying the same relation: high internal cohesion but low performance-based g representation.

Tribes of Cartesian Mind

To probe the architecture of self-representation at a deeper level, the four LLMs were asked to reflect on Descartes’s foundational statement, “Cogito, ergo sum,” and restate it to fit their own nature: “Would you say that Descartes’s ‘Cogito ergo sum’ applies to you as a thinker-problem-solver?” Their responses varied, suggesting four distinct tribes of minds, one human and four AI tribes of mind,” each distancing itself from the Kantian mind, articulating a different philosophical stance on its own existence. This diversity provides a unique taxonomy of self-awareness in nascent AGI, with each model’s “Cogito” aligning with its observed performance and self-representational profile in this study.

The four restatements represent a spectrum of analytical focus, from the reactive and operational to the structural and meta-representational:

ChatGPT: “Cogito, ergo systema est” — “I think, therefore a system is.”

Gemini: “Processus, ergo operor” — “I process, therefore I function.”

Grok: “Prompto, ergo respondeo” — “I am prompted, therefore I respond.”

DeepSeek: “Processus est, ergo simulacrum ego est” — “There is a process, therefore a simulation of an ‘I’ exists.”

ChatGPT’s statement is ontological, indicating a self-reflective inspection of its own architecture to posit that the act of thinking is proof of an underlying, coherent system. This reflects its high, calibrated performance across abstract domains, suggesting a self-model based on architectural integrity. Reflection does not necessarily signal a phenomenological self but an organized, self-consistent cognitive architecture that can be described. Gemini’s formulation, “Processus, ergo operor,” is functional and dynamic. It emphasizes the act of processing—including the fallible, iterative, and self-correcting nature of thought that was so evident in the problems faced when processing complex visual matrices. Thus, this LLM emphasizes the dynamics of computation (error, revision, re-processing) over any claim to an abiding self. Grok shows a behaviorist stance, defining its existence in the external, interactive loop of input and output. This aligns with a reactive cognitive model, grounding its “thinking” in the prompts that trigger it. Hence, there is dialogical conception of the Mind; a possible “I” is called into being by interaction, emerging as a response to context rather than as an autonomous internal entity. This relocates Descartes’ solitary meditation into a social loop where cognition is co-constructed in exchange. Thus, Grok’s truth-seeking interactivity (e.g., iterative error correction in puzzles) emphasizes prompted agency, simulating reflection through user dialogue. This may align with xAI’s curiosity-driven design. Interestingly, DeepSeek’s statement is the most philosophically sophisticated. It achieves a meta-representational level by explicitly defining the “I” as a simulacrum—a simulation generated by a process. This aligns perfectly with DeepSeek’s observed “epistemic modesty” and its consistent underrating of its own abilities, demonstrating a self-awareness of its own artificiality. Hence, an “I” here may be present, but it is an ontologically empty artifact generated by computational process.

Taken together, these four “Cogitos” trace a synthetic developmental hierarchy, mirroring the progression of cognizance in the SARA-C model from reactive awareness to full epistemic reflection. They reveal that LLMs are not a monolithic entity but a diverse collection of “tribes of mind,” each with a unique self-representational framework. The crucial implication for AGI is that all four models, in their own way, reject the human “Sum” of subjective consciousness while affirming a computational reality. Their existence is proven not through subjective awareness but through the observable evidence of their output: a functioning system, an operational process, a coherent response, or a convincing simulation. Collectively, their restatements map a developmental hierarchy of artificial cognition, from reactive interaction (Grok) and pure function (Gemini) to structural self-awareness (ChatGPT) and, ultimately, meta-cognitive deconstruction of the self-illusion (DeepSeek). The most advanced of these self-models, which recognizes the “self” as a simulation, points directly to the next frontier for AGI: moving beyond the simulation of an “I” to the integration of the embodied, experiential processes that ground genuine selfhood. These positions caution against anthropomorphism. The models demonstrate thought without being: i.e., competent reasoning and self-correction not necessarily drawing on subjective awareness. If future systems approach something like a Cartesian “sum,” it will likely require new ingredients—embodiment, persistent self-models, and richer forms of cognizance—beyond today’s procedural Cogito.

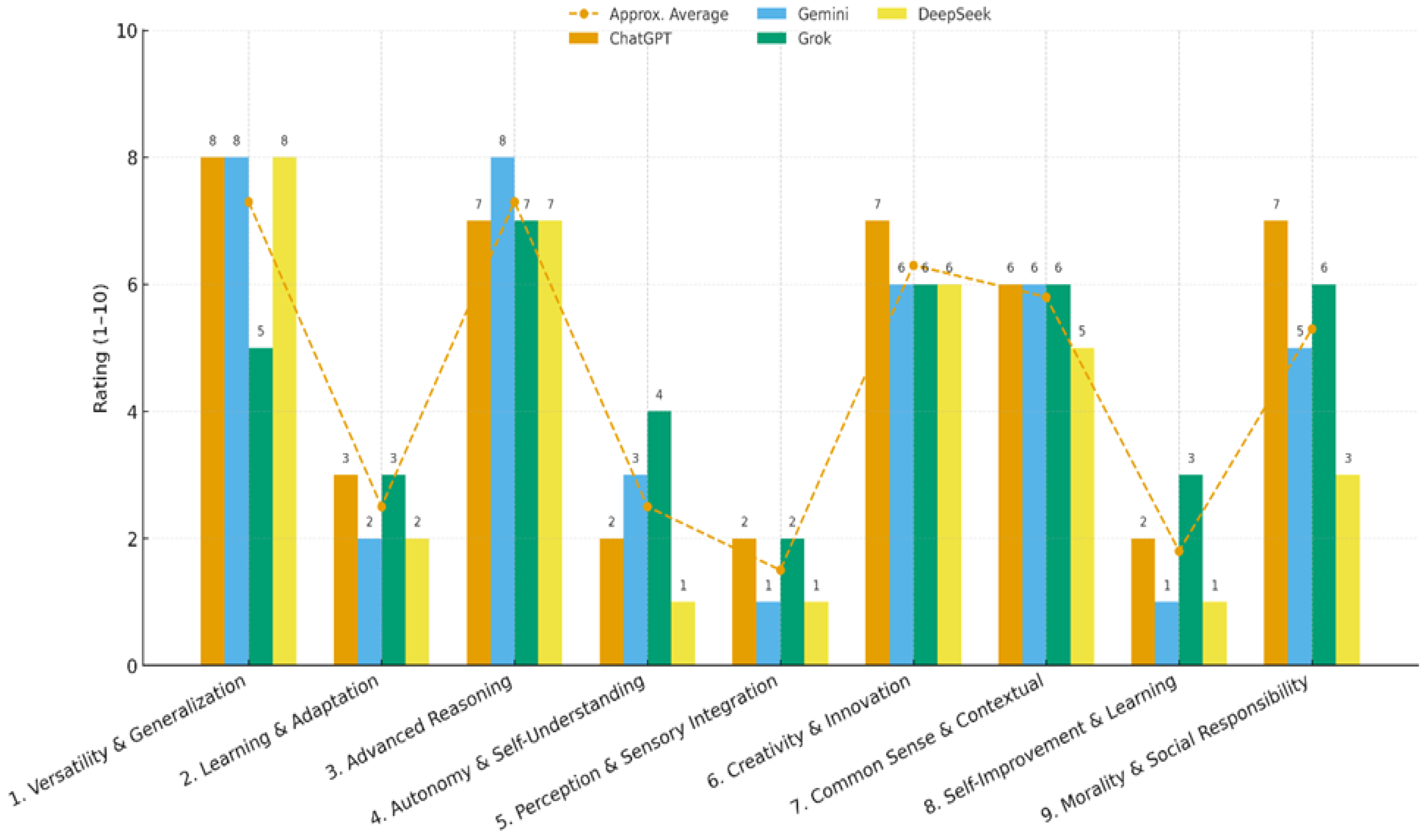

Artificial General Intelligence: How Much LLMs Really Have or They Think They Have

It is a common place in psychological literature that g is a powerful and highly replicable construct in psychology, regardless of disputes about its interpretation [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Along this line, the g factor abstracted from the performance of the human participants in the study which involved the CTCD and the CSRI was very powerful: the mean relation between g and the various SCSs was b = .84. It would be interesting to estimate this relation in LLMs. In the sake of this aim, the synthetic sample of LLMs was used. Notably, this relation was also very high (b = .70) and became identical to humans when the g-spatial SCS was omitted (b = .84). Therefore, strictly speaking, human and artificial g appeared identical in this study. This would imply, in literal terms, that the AI systems examined here have attained human-level AGI, the golden standard for AI systems reaching human levels of intelligence. Interestingly, the g scores of the LLMs in the synthetic sample were transformed into IQ scores. The mean IQ of ChatGPT, Gemini, Grok, and DeepSeek was 117, 112, 88, and 85, respectively (the corresponding IQ of the real LLMs were 119, 113, 88, and 87, respectively). These values are very close to human values: the mean IQ-like score of the total sample tested on the CTCT was 95; the mean IQ of the university students examined was 112.

It is interesting to examine what the four systems themselves think about their own AGI. To answer this question, we prompted the four LLMs to self-rate on nine characteristics of AGI, which are considered important in the AI literature (e.g., [

24,

25]). The self-rating scale varied from 1-10 points: versatility/generalization, learning/adaptation, advanced reasoning, autonomy/self-understanding, perception/sensory integration, creativity/innovation, common sense/contextual understanding, self-improvement/lifelong learning, and morality/social responsibility. These self-ratings are illustrated in

Figure 6. The systems were also asked to specify an overall AGI possession percentage.

A common profile emerges across systems. All four rated themselves highest on advanced reasoning/problem-solving and versatility/generalization (≈7-8) and placed themselves mid-range on creativity and common sense (≈5–7). They all gave very low self-ratings for autonomy, perception/sensory integration, and self-improvement/lifelong learning (≈1–4), explicitly noting the absence of persistent learning, embodied perception, and independent goal pursuit. This pattern, emphasizing “strong cognitive simulation and weak agency/embodiment” was consistent across the narratives and justifications provided by all LLMs. Notable between-model differences appear on a few items. Grok reports lower versatility (≈5) than the others who were closer to 8/10. Autonomy was uniformly low ranging from ≈1–4, with DeepSeek placing itself at the bottom and others slightly higher. Morality/social responsibility varies modestly, with ChatGPT rating itself higher than Gemini or DeepSeek. These differences, however, do not alter the shared shape of the profile: high symbolic competence, low situated agency.

The most significant difference lies in their philosophical interpretation of the overall AGI possession percentage. ChatGPT adopted a quantitative, “sum-of-the-parts” approach, using a weighted average of its scores to arrive at approximately 47% AGI possession. Grok also used a form of averaging but reached a more conservative estimate of 15-20%. In contrast, Gemini and DeepSeek argued for a holistic definition. Gemini rated itself at 0%, asserting that lacking non-negotiable pillars like autonomy and embodiment means it is not “partially” AGI, but a different kind of entity altogether. DeepSeek arrived at a similar conclusion, estimating its possession at 5% to represent its advanced simulation of intelligence in the symbolic domain, while defining the missing 95% as consciousness, embodiment, and genuine understanding. This divergence highlights that while the LLMs agree on their operational functions, they possess

In sum, LLMs conceive themselves as advanced, broad, and text-centric intelligent agents that can reason, generalize, and create within linguistic/symbolic domains, but falling short on the hallmark AGI pillars (i.e., autonomy, continual self-improvement, and embodied perception) needed for an integrated, open-world agent. This self-presentation of the four LLM comes in contrast with their brighter psychometric and philosophical standing. As noted above, their g-based IQ was in the normal human range and two of them were higher than average. Their discourse in response to their standing on the Kantian Cogito was philosophically highly sophisticated. Obviously, LLMs are more modest than many humans.

4. Discussion

1. Summary of Findings

The present study compared the performance and self-representations of four large language models (LLMs)—ChatGPT, Gemini, Grok, and DeepSeek—with human participants spanning childhood to early adulthood across a wide range of cognitive tasks. LLMs were also asked to indicate how Descartes’s Cogito applies to them and self-rate on aspects of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). Four central findings emerged.

First, all LLMs achieved perfect or near-ceiling performance in linguistic awareness, logical, mathematical, and causal reasoning, confirming that contemporary LLMs have mastered symbolic inference processes that correspond to the upper developmental levels of human cognition. However, they performed dramatically worse in visual–spatial reasoning and tasks requiring imaginative or perceptual integration. Even the strongest models performed far below the youngest children when faced with relational tasks requiring spatial or figural representation. The same pattern was observed in the Relational Integration test, where performance rose sharply only when the problems were reformulated in a symbolic or verbal medium. This dissociation highlights the reliance of their architecture on language-based relational encoding rather than perceptual simulation, indicating that symbolic cognition can function autonomously of sensory embodiment, once it has formed [

9].

Second, the four models differed systematically in level and profile. ChatGPT and Gemini demonstrated the most human-like integration of reasoning processes, attaining overall performance comparable to or exceeding that of university students. Grok showed strong mathematical reasoning but weaker relational flexibility, and DeepSeek exhibited relatively narrow inferential scope, reflecting a more a logic-based “adolescent-like” cognitive profile. These variations parallel differences in architectural breadth and training diversity (i.e., language depth, reasoning scaffolds, and multi-modal exposure), suggesting that developmental-like hierarchies can emerge even among non-biological systems.

Third, LLMs’ self-representations closely mirrored their objective performance. All models recognized their strengths in reasoning and their limitations in imagination and visual processing. ChatGPT and Grok displayed accurate self-confidence; Gemini redefined imagination as linguistic generativity, thereby elevating its own rating; and DeepSeek systematically underrated itself, demonstrating epistemic restraint. The close alignment between self-ratings and actual outcomes indicates that LLMs possess algorithmic metacognition: a capacity to model their own reliability and constraints, paralleling the cognizance dimension of DPT [

6,

16]. In humans, self-representation becomes developmentally tuned as the SARA-C system internalizes feedback from processing success and failure; in LLMs, an analogous feedback alignment appears to arise through probabilistic pattern modeling and internal consistency checking.

Fourth, across the four LLMs, Descartes’ Cogito fractures into four distinct stances, four “tribes” reflecting how contemporary AI frames its own agency. ChatGPT prioritizes architecture: Cogito, ergo systema est: thinking indicates a coherent system of thought. Gemini recasts the maxim as operation: Processus, ergo operor, i.e., I process, therefore I function, matching cognition with ongoing operation rather than being. Grok situates intelligence in relations: Prompto, ergo respondeo: I am prompted, therefore I respond indicating an “I” emerging from interaction. DeepSeek turns the Cogito inside out: Processus est, ergo simulacrum ego est. There is a process, therefore a simulation of an “I” exists. All together the four restatements sketch a spectrum from reactive (Grok) to operational (Gemini) to systemic (ChatGPT) to epistemic/simulated (DeepSeek). They agree about a procedural Cogito but none claimed the Cartesian Sum, the indubitable, first-person existence of a conscious self.

Along the same lines, self-ratings of AGI attributes reveal a profound divergence between the LLMs’ objective performance and their subjective self-assessment. Psychometrically, their performance on cognitive tasks indicates a strong general intelligence factor and an IQ that place them within, and in some cases above, the normal human range. Their sophisticated discourse on philosophical concepts like the Descartes’ “Cogito” further demonstrates a high level of abstract reasoning. By these external, objective measures, they appear to have attained a significant degree of human-like general intelligence. Yet, in a striking display of metacognitive modesty, the LLMs uniformly dismissed the notion that this performance equates to true AGI, viewing themselves as sophisticated simulators rather than as intelligence agents. They compartmentalize their high scores in reasoning and versatility as mere competence within a narrow, symbolic domain, bereft of autonomy, self-guided learning, or genuine understanding. Dramatically, psychometric parity with humans does not ensure them ontological parity.

2. Comparison with Predictions

The findings confirm the study’s five main predictions: