1. Introduction

The nature of human intelligence and consciousness has long been a source of fascination and contention within both the philosophical and scientific communities. At the heart of this enduring debate lies a fundamental question: is human intelligence Turing-computable? This inquiry, while rooted in philosophical abstraction, has profound implications for our understanding of cognition, artificial intelligence (AI), and the very essence of what it means to be human.

Daniel Dennett, an influential philosopher and cognitive scientist, was a leading proponent of the view that human intelligence (and perhaps conscience) arises from physical, computational processes. His work, notably

Consciousness Explained [

14], advances a functionalist framework that posits the brain as an information-processing system capable of producing mental states purely through interactions among its physical components. Dennett rejected the Cartesian dualistic interpretations of consciousness, arguing instead that the mind is not an ethereal or immaterial phenomenon but, rather, a product of evolutionary processes and the capacity and complexity of human brains.

At the core of Dennett’s philosophy is the assertion that all mental states, including what we call intelligence and consciousness, can be understood as "intentional stances" — patterns of information that emerge from the physical substrate of the brain. He contended that the brain operates much like a Turing machine, processing information algorithmically and giving rise to emergent properties such as perception, memory, and awareness. This computational perspective appears consistent with recent advances in AI, where artificial neural networks and machine learning models are increasingly exhibiting behaviours reminiscent of human cognition as these models scale in capacity and complexity.

Critics of Dennett’s views argue that his reductionist approach fails to capture the qualitative, subjective nature of human consciousness. One key critic of Dennett’s views is Australian philosopher David Chalmers [

10], whose work introduces the concept of the "hard problem" of consciousness. While Dennett focuses on explaining the functional and mechanistic aspects of the mind — which Chalmers calls the "easy problems" — Chalmers emphasizes the difficulty of accounting for

qualia, or the subjective experiences that define consciousness. He asserts that no amount of physical or computational explanation can fully address why and how subjective experiences arise.

Chalmers questions whether current computational theories fully explain how subjective experience arises, suggesting that we may need fundamental bridging laws—and possibly novel physical or theoretical frameworks—to account for

phenomenal consciousness [

10]. Daniel Dennett, by contrast, argued that the so-called "hard problem" [

10] is just an illusion created by the way we think about consciousness. In [

14], Dennett suggested that once all the "easy problems" are solved, there is no additional mystery left to explain. From Dennett’s perspective, focusing on qualia as irreducible entities is misguided. In Dennett’s view, qualia are illusory constructs that arise from flawed introspection, and understanding consciousness requires explaining its functional and mechanistic basis, and not by positing ineffable, intrinsic properties.

The dichotomy between Dennett’s computational functionalism and Chalmers’ emphasis on the irreducibility of qualia has fueled decades of philosophical discourse. However, rather than rehashing this endless debate, this paper adopts a pragmatic and results-oriented approach to addressing the question of Turing-computability of human cognition and consciousness. We feel that, instead of relying solely on theoretical arguments, the most compelling way to settle the debate is through demonstration.

By developing machine learning models capable of replicating, or even surpassing certain aspects of human cognition and consciousness, researchers can present empirical evidence for or against the Turing-computability of the mind. If such models succeed in exhibiting behaviors and capabilities that mirror or extend human intelligence, they would lend significant credence to Dennett’s position. Conversely, their failure to replicate key aspects of human consciousness might bolster Chalmers’ argument that the mind contains elements beyond computational reach.

In this paper, therefore, we focus not on resolving philosophical differences but on exploring the practical and experimental pathways toward understanding the computational underpinnings of human consciousness. By examining the role of capacity and complexity, emergent properties, and scaling in machine learning models, we aim to contribute insights to this age-old debate.

2. The Debate on the Turing-Computability of Human Intelligence

The question of whether machines can replicate human-level intelligence has been central to AI since its inception. In his seminal 1950 paper

Computing Machinery and Intelligence [

38], Alan Turing introduced the Turing Test, which focuses on whether a machine’s responses are indistinguishable from a human’s, bypassing the subjective notion of understanding. Early symbolic AI [

17] systems, such as expert systems [

8], sought to encode human reasoning explicitly (as rules) but struggled with ambiguity and incomplete data, exposing the limitations of these approaches in replicating human adaptability [

33].

A major philosophical challenge in this debate concerns the distinction between

simulating intelligence and genuinely

possessing it. Proponents of

Strong AI [

26,

36] claim that machines could one day possess intelligence and consciousness equivalent to humans. Conversely, advocates of

Weak AI argue that machines can only simulate intelligent behavior without true understanding. Searle’s Chinese Room argument [

35] exemplifies this skepticism. In his thought experiment, an individual manipulates Chinese symbols based on syntactic rules without understanding their meaning. Searle’s argument is that AI systems manipulate data without semantic comprehension, challenging the claim that machines "understand" their outputs. However, Dennett in [

14] contends that "understanding" lacks a universally recognized formal definition and, in any case, if a machine’s output is indistinguishable from that of a human, the distinction becomes irrelevant.

At the heart of this debate lies the question of whether human intelligence is Turing-computable. The Church-Turing thesis [

12] posits that any algorithmic process can be computed by a Turing machine, suggesting that human intelligence, if algorithmic, is replicable by computational systems. Proponents, such as Dennett, argue that intelligence and consciousness are emergent properties of sufficiently large and complex physical systems and can be understood functionally, emphasizing behavior over mechanism [

14]. However, the (many) critics suggest that human cognition may involve processes beyond Turing machines, such as quantum effects or non-algorithmic properties [

15,

19,

34], implying that human intelligence might not be fully Turing-computable. If true, this would challenge, or even outright refute, the Church-Turing thesis.

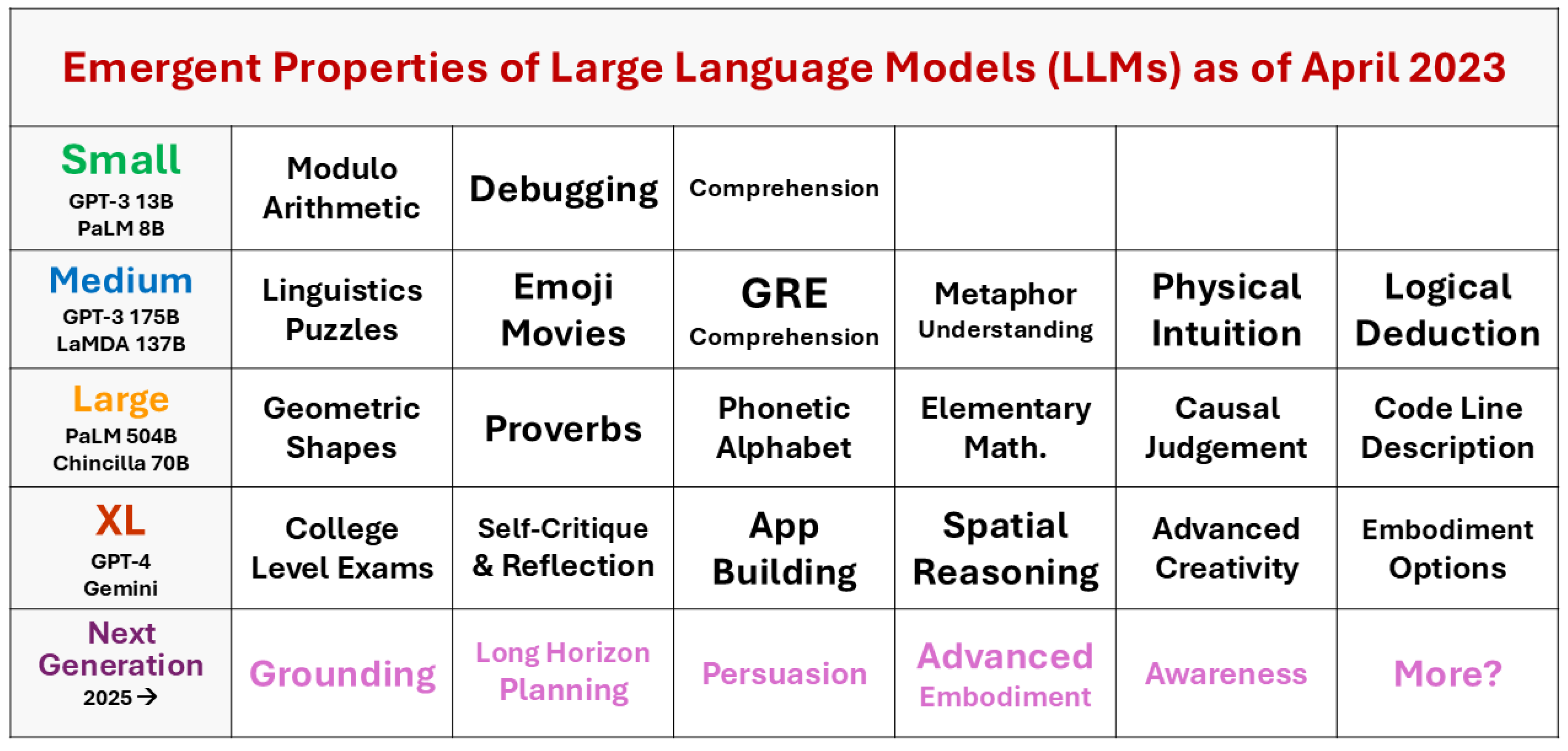

Modern advances in AI, particularly with large language models (LLMs), have contributed to the ongoing debate. Transformer-based models, such as ChatGPT, now exhibit behaviors traditionally associated with human intelligence, such as language understanding, reasoning, and creativity [

7,

39]. These models rely on vast datasets for model training, computational resources, and scaling laws, which have shown that increasing model size and complexity (see

Figure 1) often leads to emergent capabilities not explicitly programmed such as zero-shot learning and few-shot reasoning [

7]. These emergent behaviors blur the line between

simulated and

genuine intelligence.

Despite their impressive capabilities, LLMs raise unresolved questions. Intelligence itself lacks a universally accepted definition [

28], complicating the evaluation of whether AI systems exhibit true intelligence. Additionally, the question of consciousness—whether machines can actually possess subjective experience—remains speculative. Dennett in [

14] suggests that consciousness emerges from sufficiently complex systems as a product of physical and functional processes, although this view remains philosophically debated and empirically unresolved. If human intelligence involves processes beyond Turing computation [

34], such as non-algorithmic operations, this would challenge the Church-Turing thesis and perhaps even redefine the boundaries of computation.

3. The Kolmogorov Complexity of Human Intelligence

Kolmogorov Complexity [

29] is a foundational theoretical concept in computer science that quantifies the descriptive complexity of objects. Formally, it is defined as the length (in bits) of the shortest algorithm, written in a fixed programming language, that can generate a given object (for example, a string of characters over some alphabet) and terminate. Intuitively, Kolmogorov Complexity measures the amount of information required to fully describe an object. For example, a string consisting of repeated

01 patterns, such as

010101..., can be succinctly described by the regular expression

(01)* and, thus, has a low Kolmogorov Complexity. In contrast, a random binary string of the same length would require a description close to its full length, resulting in a high Kolmogorov Complexity.

Kolmogorov Complexity can also be extended to problems, where it is defined as the length (in bits) of the shortest algorithm that optimally solves a given problem and terminates. In this sense, Kolmogorov Complexity measures the descriptive complexity of the algorithm of least size that solves the problem, rather than that of a specific object. This extension of Kolmogorov complexity from objects to problems bears conceptual similarity to the work of [

37] on resource-bounded Kolmogorov complexity, where he examines the minimal description length needed to specify algorithms that solve computational problems. While Sipser’s approach emphasizes resource constraints, both perspectives aim to capture the intrinsic complexity of problems through the size of their minimal algorithmic representations.

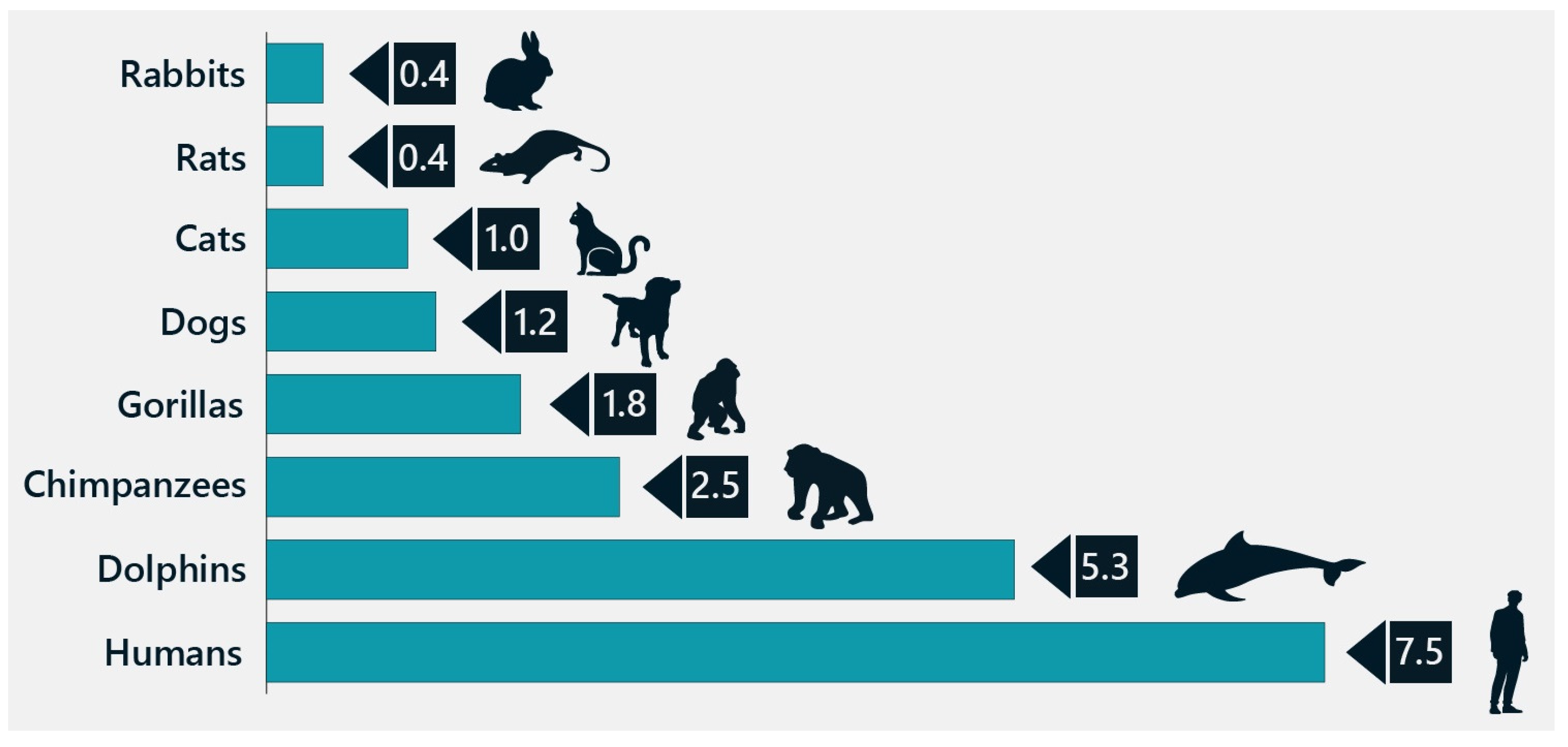

It may be the case that human intelligence has an exceptionally high Kolmogorov Complexity due to the intricacy and functionality of the human brain. The human brain contains approximately 86 billion neurons and 100 trillion synaptic connections [

20], making it one of the most complex biological systems known. Humans also possess the highest encephalization quotient (EQ) (see

Figure 2)—a measure of brain size relative to body size, calculated by dividing the mass of the brain by the mass of the body—of any mammal, with values between 7.5 and 8.0. This means that the human brain is about 7–8 times larger than what would be expected for an animal of our body size [

13,

22]. Such complexity and size are unlikely to be coincidental; rather, they reflect the cognitive demands of advanced intelligence. Biological systems often demonstrate efficiency, favoring solutions that optimize survival and reproduction while minimizing energy expenditure. The human brain’s significant energy demands—approximately 20% of the body’s total energy consumption, ranging from 20 to 30 watts—highlight its evolutionary necessity [

23]. Given its energy-intensive nature, such an organ would not have evolved to its size and complexity unless these conferred substantial adaptive advantages.

The number of neurons and synaptic connections alone does not fully account for the brain’s complexity. Other factors, such as its structure, plasticity, neuron density, and cortical folding, also contribute. For example, dolphins have one of the highest EQs among non-human species and their neural architecture is highly specialized for echolocation—a process requiring complex signal processing and neural adaptations [

4]. In contrast, the human brain exhibits a higher degree of cortical folding, or

gyrification, which increases surface area and enables greater computational capacity within a constrained volume [

20]. This comparison suggests that brain functionality depends not only on the number of neurons but also on their organization, density, and the evolutionary pressures shaping them. The specialization of dolphin brains for echolocation highlights the influence of ecological demands, whereas the general-purpose adaptability of human brains reflects a broader range of cognitive and social requirements. The human brain’s intricate structure and connectivity enable it to process vast amounts of sensory, cognitive, and emotional information [

24]. These capabilities arise from massively parallel and distributed neural networks, whose interactions involve nonlinear dynamics. Capturing these interactions and their emergent behaviors algorithmically would probably require immense descriptive complexity, further supporting the hypothesis that human intelligence may have high Kolmogorov Complexity.

Evolutionary pressures have shaped the human brain to balance efficiency with adaptability. High cognitive adaptability has driven the evolution of a brain capable of nuanced tasks, abstract reasoning, and complex social interactions, increasing its Kolmogorov Complexity. The human brain is metabolically expensive, consuming approximately 20% of the body’s energy, which highlights the evolutionary necessity of its efficiency [

1]. The high EQ of humans reflects an evolutionary trajectory in which increasing brain complexity became essential for survival and reproduction [

22]. Furthermore, the social brain hypothesis [

16] suggests that the demands of maintaining complex social networks played a crucial role in driving brain size and cognitive capacity. Together, these factors highlight the evolutionary balance between adaptability, energy efficiency, and the cognitive demands that define human intelligence.

Large language models (LLMs), such as GPT-3 and GPT-4, exhibit impressive emergent capabilities but require billions (or perhaps trillions) of parameters and vast computational resources [

7]. While these systems possess roughly two orders of magnitude fewer parameters than the human brain has synaptic connections, it is important to recognize that this numerical comparison is a heuristic; it does not capture the dynamic, adaptive, and multifaceted nature of biological synapses. This disparity suggests that the Kolmogorov Complexity of human intelligence, as a natural phenomenon, may be significantly higher. While LLMs demonstrate that scaling can lead to emergent properties, their current efficiency and adaptability fall far short of human cognitive skills. This raises the hypothesis that scaling [

25] and complexity are prerequisites for achieving higher-level cognitive functions, although empirical validation is necessary to substantiate such claims.

Scale may be a critical factor, both in nature and AI. While the basic structure of a neuron in the human brain is similar to that in the brain of an ape, the overall size and complexity of the brain are decisive. As Noam Chomsky famously remarked [

11], “

It’s about as likely that an ape will prove to have a language ability as that there is an island somewhere with a species of flightless birds waiting for human beings to teach them to fly.” Apes likely lack the capacity for language not because of qualitative differences in individual neurons but due to the insufficient size and complexity of their brains to support the intricate structures and dynamics required for linguistic ability.

4. Capacity, Complexity, and the Pursuit of AGI

Nature offers profound lessons about the prerequisites for achieving human-level intelligence. Observations from biology suggest, in our view, that both capacity and complexity are integral for advanced cognitive abilities. The human brain demonstrates a scale and intricacy that far surpass current AI models. In this section we discuss how insights from nature align with trends in the development of large language models (LLMs) and their implications for the pursuit of AGI.

4.1. Emergent Properties in LLMs

Scaling laws in transformer models suggest that increasing parameters is associated with emergent behaviors such as zero-shot reasoning and few-shot learning [

7]. For instance, GPT-3 can answer questions, translate between languages, and perform arithmetic without specific task-based fine-tuning [

6,

7]. Recent work suggests that these emergent behaviors may arise from the interplay between scaling, training objectives, and architectural innovations [

40]. However, the precise mechanisms underpinning these emergent properties remain an area of active research.

4.2. Biological Comparisons

While the number of parameters in LLMs approaches trillions, their architecture remains far simpler than the hierarchical and distributed processing found in biological brains. For example, the human brain’s use of specialized regions, dynamic plasticity, and parallel processing provides efficiencies and adaptability that AI models cannot yet replicate [

13,

20]. Furthermore, synaptic connections serve multiple roles, including plasticity and learning, that far exceed the static weights (parameters) of artificial models. These architectural and functional differences highlight the challenge of achieving AGI through scale alone.

4.3. The AI Arms Race

The push to scale LLMs has led to significant infrastructure investments. OpenAI’s partnership with Microsoft for Azure supercomputing infrastructure exemplifies this trend, with reports of data centers leveraging tens (or hundreds) of thousands of high-end GPUs for model training [

9]. Similarly, Google’s development of TPU clusters demonstrates the increasing demand for specialized hardware to support the computational requirements of large-scale models [

21]. These developments support the prevailing view that scaling computational resources is critical for advancing AI capabilities.

A central question remains:

will continued increases in capacity and complexity lead to the emergence of AGI? While LLMs have demonstrated remarkable capabilities, such as reasoning and commonsense knowledge, they still fall short of human-like adaptability and generalization [

6]. The hypothesis that AGI requires not just larger models but qualitatively new forms of complexity—analogous to the structural diversity in the human brain—remains a focus of ongoing research. Nevertheless, scaling trends provide a compelling framework for exploring the boundaries of what AI can achieve.

The trajectory of LLM development highlights capacity and complexity as significant factors influencing intelligence levels. By observing scaling laws in artificial systems and their parallels in biological intelligence, researchers are charting a path that may one day bridge the gap between current AI systems and AGI. Whether this path ultimately leads to AGI remains uncertain.

4.4. Is Attention All We Need?

The success of transformer architectures, driven by attention mechanisms, has prompted questions about whether the attention mechanism alone is sufficient for achieving AGI. Attention allows models to focus computational resources on the most relevant parts of input data, enabling state-of-the-art performance in language understanding, reasoning, and other domains [

7,

39]. However, while attention has proven transformative, it may not address all the requirements for AGI.

One limitation of attention mechanisms is their lack of intrinsic long-term memory and adaptability. Human intelligence relies heavily on persistent memory and dynamic reorganization of neural pathways, allowing individuals to adapt to novel environments and tasks without retraining. In contrast, current models require extensive fine-tuning or retraining to generalize to new domains [

30].

Moreover, the human brain incorporates a wide array of mechanisms, including hierarchical processing, feedback loops, and modular specialization, that go beyond the capabilities of attention [

31,

32]. These processes enable rapid contextual shifts, multitasking, and the integration of sensory and conceptual information. Achieving AGI may require innovations in AI architectures that mirror this complexity, such as dynamic models, neurosymbolic systems, or embodied AI [

30].

Critiques of large-scale models, such as those in [

3], further highlight the potential limitations of attention-based systems. They argue that scaling alone risks creating "stochastic parrots," models that generate coherent but fundamentally shallow outputs lacking true understanding or reasoning. This raises concerns about whether current trends in scaling and attention are sufficient for achieving AGI or whether fundamentally new paradigms are required.

While attention has been a cornerstone of recent advances, its sufficiency for AGI remains an open question. Progress may depend not only on scaling but also on the discovery of fundamentally new mechanisms that address the limitations of current architectures.

5. Revisiting the Chinese Room Argument

The Chinese Room Argument, proposed by John Searle in 1980 [

35], remains a cornerstone of philosophical debates on AI. Searle’s thought experiment challenges the notion that computational systems can possess true understanding or consciousness. In the argument, a person inside a room manipulates Chinese symbols based on syntactic rules provided in English, producing responses indistinguishable from those of a native speaker. Despite this, the person does not understand Chinese, leading Searle to conclude that syntax alone cannot generate semantics.

Large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-3, GPT-4, and Gemini demonstrate impressive linguistic capabilities, including generating coherent text, translating between languages, and even engaging in logical reasoning [

7]. These systems, however, operate by statistically modeling language patterns from vast training data. According to Searle’s argument, this statistical manipulation—no matter how advanced—lacks any intrinsic understanding or semantic content, replicating the person in the Chinese Room.

Critics of Searle, including Daniel Dennett, argue that the distinction between simulation and genuine understanding may be less significant than Searle posits [

14]. Dennett suggests that understanding could emerge from sufficiently complex systems, whether biological or computational, and that the absence of human-like introspection does not preclude meaningful forms of cognition.

Recent advances in AI, particularly the emergent capabilities in LLMs [

40], have reignited debates surrounding the Chinese Room. These models exhibit behaviors that go beyond rote pattern matching, raising questions about whether "understanding" might emerge at a certain level of complexity. For instance, GPT-3 can generate responses that suggest contextual awareness and abstract reasoning [

7].

Despite these advances, the core challenge posed by the Chinese Room persists: do these systems truly understand, or are they merely simulating understanding? As Searle emphasized, this question hinges on whether computational systems can bridge the gap between syntax and semantics.

The Chinese Room Argument continues to serve as a provocative lens through which to evaluate the capabilities and limitations of modern AI systems. While recent breakthroughs in LLMs suggest that emergent properties can enhance the appearance of understanding, the philosophical distinction between simulation and genuine cognition remains unresolved. Whether the increasing complexity and capacity of AI systems will eventually render the Chinese Room obsolete—or reinforce its validity—remains an open question.

6. Conclusions and Synthesis

This paper has examined the interplay between Daniel Dennett’s philosophy of mind, Kolmogorov Complexity, and the rise of Transformer models in AI, highlighting insights into the prerequisites for human-level intelligence. Observations from nature emphasize the importance of capacity and complexity, as exemplified by the human brain’s remarkable adaptability, which far surpasses current artificial systems. The scaling trends observed in modern AI suggest that these principles are not only desirable but may be essential for achieving advanced cognitive abilities.

Transformer models, such as GPT-3 and GPT-4, illustrate how increasing size and complexity can correlate with emergent capabilities such zero-shot learning and multilingual reasoning. However, current architectures still fall short of AGI, lacking the adaptability, long-term memory, and hierarchical processing found in biological systems [

6,

30]. Achieving AGI may innovations that go beyond scaling—perhaps integrating dynamic memory and neurosymbolic reasoning [

27,

30].

Beyond AI research, Transformer models hold promise for addressing challenges in astrophysics and cosmology. Instruments such as the SKA, JWST, and Vera Rubin Observatory generate immense datasets requiring tools capable of capturing long-distance relationships and nuanced patterns. Transformers and other deep learning models have the potential to assist in identifying rare astronomical events, such as fast radio bursts, and in uncovering subtle features in spectroscopic data that reveal the physical processes governing distant galaxies [

2,

5,

18]. Their ability to model relationships across distributed data offers new opportunities to understand large-scale cosmic structures and their evolution.

In conclusion, the interplay of capacity, complexity, and emergent behavior offers a guiding framework for AGI research and, by bridging biological insights, computational theory, and practical tools, transformers advance our understanding of intelligence and provide new approaches to exploring the universe. References

References

- Aiello, L. C., & Wheeler, P. 1995, Current Anthropology, 36, 199.

- Allam Jr, T., & McEwen, J. D. 2024, RAS Techniques and Instruments, 3, 209.

- Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. 2021, in Proceedings of the 2021 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency (ACM), 610.

- Berta, A., Sumich, J. L., & Kovacs, K. M. 2005, Marine Mammals: Evolutionary Biology (Elsevier).

- Boersma, O. M., Ayache, E. H., & van Leeuwen, J. 2024, RAS Techniques and Instruments, 3, 472.

- Bommasani, Rishi et al. 2021, arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07258.

- Brown, T., & et al. 2020, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 1877.

- Buchanan, B. G., & Shortliffe, E. H. 1984, Rule Based Expert Systems: the MYCIN Experiments of the Stanford Heuristic Programming Project (Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.).

- CDoTrends 2023, Microsoft, OpenAI Planning USD$100B AI Supercomputer, https://www.cdotrends.com/story/3909/microsoft-openai-planning-usd100b-ai-supercomputer. Accessed on December 16, 2024.

- Chalmers, D. J. 1996, The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Theory of Conscious Experience (New York: Oxford University Press).

- Chomsky, N. 2007, On the Myth of Ape Language (interviewed by Matt Aames Cucchhiaro), https://chomsky.info/2007____/. Accessed: 2024-12-22.

- Church, A. 1936, American Journal of Mathematics, 58, 345.

- Deacon, T. W. 1998, The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Brain (W.W. Norton & Company).

- Dennett, D. 1993, Consciousness Explained (Penguin UK).

- Dreyfus, H. L. 1972, What Computers Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason (Harper and Row).

- Dunbar, R. I. 1998, Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews: Issues, News, and Reviews, 6, 178.

- Feigenbaum, E. A., Feldman, J., et al. 1963, Computers and Thought, vol. 37 (New York McGraw-Hill).

- Gómez, C., Neira, M., Hernández Hoyos, M., Arbeláez, P., & Forero-Romero, J. E. 2020, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 499, 3130.

- Hameroff, S., & Penrose, R. 1996, Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 40, 453.

- Herculano-Houzel, S. 2009, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 3, 31.

- HPCwire 2024, Google Announces Sixth-Generation AI Chip: a TPU Called ‘Trillium’, https://www.hpcwire.com/2024/05/17/google-announces-sixth-generation-ai-chip-a-tpu-called-trillium/. Accessed on December 10, 2024.

- Jerison, H. 1973, Evolution of the Brain and Intelligence (Academic Press).

- Kaas, J. H. 2000, Brain and Mind, 1, 7.

- Kandel, E. R., & et al 2021, Principles of Neural Science (6th Edition), vol. 6 (McGraw-Hill New York).

- Kaplan, J., McCandlish, S., Henighan, T., Brown, T. B., Chess, B., Child, R., Gray, S., Radford, A., Wu, J., & Amodei, D. 2020, arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361. https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.08361.

- Kurzweil, R. 2005, in Ethics and Emerging Technologies (Springer), 393–406.

- Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Gershman, S. J. 2017, Behavioral and brain sciences, 40, e253.

- Legg, S., Hutter, M., et al. 2007, Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and applications, 157, 17.

- Li, M., Vitányi, P., et al. 2008, An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and its Applications, vol. 3 (Springer).

- Marcus, G., & Davis, E. 2019, Rebooting AI: Building Artificial Intelligence we can Trust (Vintage).

- Miller, E. K., & Cohen, J. D. 2001, Annual review of neuroscience, 24, 167.

- Mountcastle, V. B. 1997, Brain: a Journal of Neurology, 120, 701.

- Nilsson, N. J. 2009, The Quest for Artificial Intelligence (Cambridge University Press).

- Penrose, R. 1994, Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness, vol. 4 (Oxford University Press).

- Searle, J. R. 1980, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3, 417.

- Simon, H. A., & Newell, A. 1976, Communications of the ACM, 19, 113.

- Sipser, M. 1983, 330.

- Turing, A. M. 1950, Mind, 59, 433.

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., & et al. 2017, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), 30.

- Wei, J., & et al. 2022, arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.07682. https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.07682.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).