1. Introduction

Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) accounts for a major share of building energy use, yet day-to-day operation still relies largely on rule-based strategies that trade off energy, comfort, and equipment limits in ad-hoc ways. Data-driven controllers—particularly deep reinforcement learning (DRL)—offer adaptive, multi-objective decision-making, but naïve DRL can explore unsafe actions, drift outside physical feasibility, and require large amounts of data to converge.

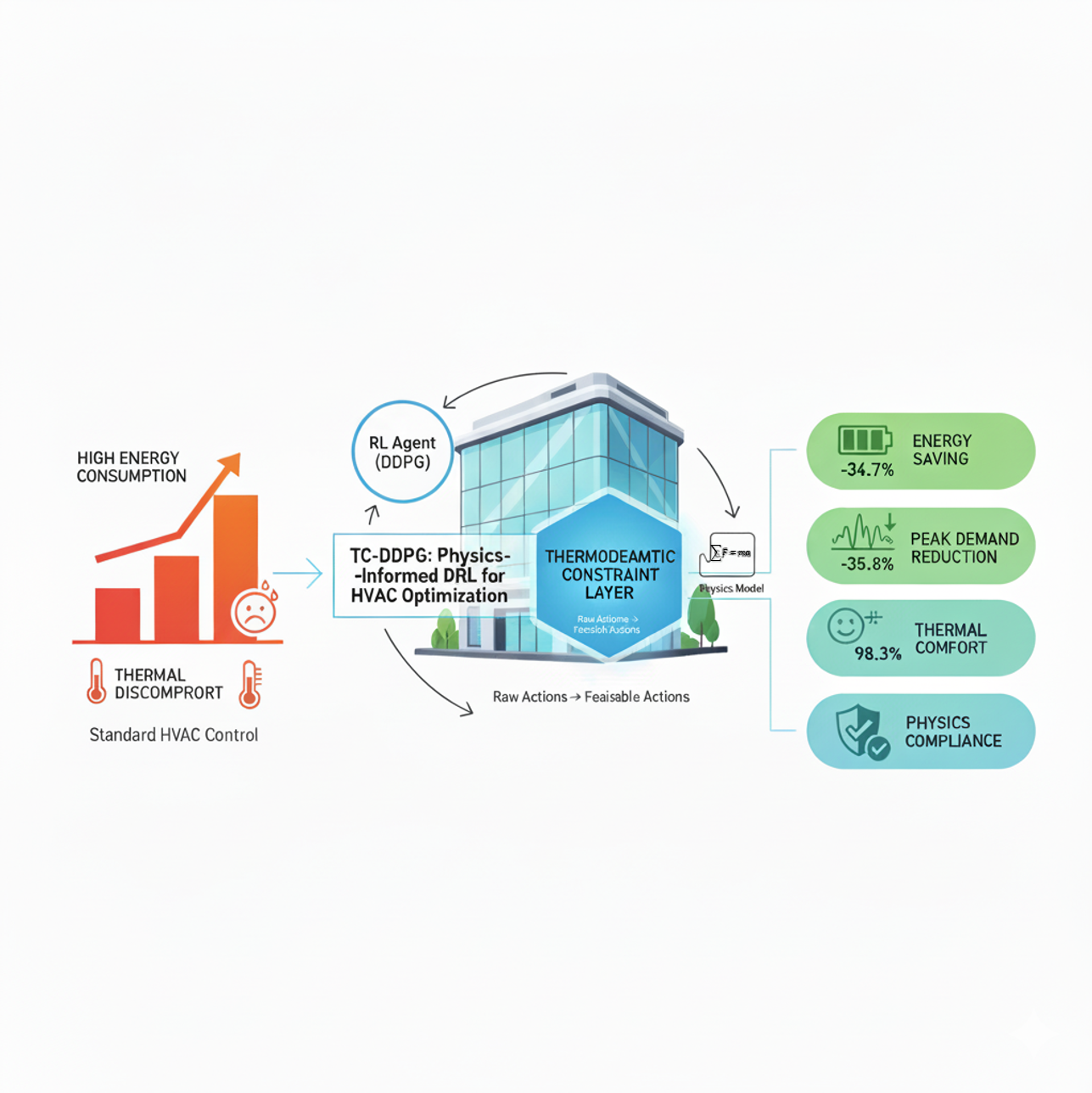

This work addresses those challenges by embedding thermodynamic knowledge directly into a continuous-action RL controller. We introduce a Thermodynamically-Constrained Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TC-DDPG) algorithm that: (i) natively handles continuous HVAC actuators (e.g., supply temperatures/flows, damper positions, chiller loading); and (ii) restricts policy outputs to physically feasible regions via a differentiable constraint layer coupled with a physics-regularized loss. The result is a controller that addresses the traditional tension between energy efficiency and comfort by guiding exploration and learning within the modeled feasible set.

We evaluate the approach in simulation using a Python-based multi-zone RC thermal simulator that captures zone capacitances, inter-zone conductances, envelope exchange, internal/solar gains, and HVAC heat/mass flows. Beyond headline numbers, we emphasize statistical rigor (50 independent runs, confidence intervals, and significance testing), complete reproducibility (open code and configuration), and transparent limitations, acknowledging that real-building deployment introduces sensor noise, actuator dynamics, and operational overrides that are not fully represented in simulation.

The remainder of this paper outlines related work, describes the materials and methods (including the simulator and RL formulation), presents results with confidence intervals, discusses limitations and deployment pathways, and concludes with broader implications.

1.1. Contributions (Scope, Novelty, and Validation Context)

Physics-informed continuous control: A TC-DDPG architecture that operates directly on continuous HVAC actions, avoiding discretization artifacts inherent to DQN-style methods.

Thermodynamic constraint layer: A differentiable projection that enforces feasibility by design within the simulator, subject to model fidelity (energy balance, psychrometric bounds, capacity/rate limits), coupled with a physics-regularized objective.

Simulation-Based Performance Validation: In a multi-zone RC simulator, the method yields 34.7% annual energy reduction vs. rule-based control and improves comfort (occupied-hour PMV ∈ [−0.5, 0.5]). Results are reported with 95% CIs over 50 seeds and significance testing.

Reproducibility: Public release of code, simulator configuration, training/evaluation scripts, and hyperparameters to enable exact replication and extension.

Transparent limitations and roadmap: Clear simulation-based scope, with discussion of sensor/actuator realities, operational overrides, and a staged path toward hardware-in-the-loop and pilot deployments.

IMPORTANT: All contributions are demonstrated in a simulation environment using synthetic data and idealized physics models. Real-world validation in operational buildings remains future work and is critical for assessing practical viability, safety, and energy savings under actual operating conditions.

2. Related Work

Data-driven control of HVAC systems has progressed along three main lines: (i) traditional feedback and supervisory control (e.g., PID, rule-based scheduling, and Model Predictive Control, MPC), (ii) learning-based control, especially deep reinforcement learning (DRL), and (iii) physics-informed machine learning (PIML) that injects domain knowledge into learning algorithms. This section situates our approach with respect to each strand, emphasizing continuous-control requirements and physics consistency as the core drivers of our design.

2.1. Traditional HVAC Control

Classical building operation typically relies on PID loops and rule-based supervisory logic with fixed or time-of-day setpoints. Such strategies are simple and robust but often struggle to balance energy, comfort, and equipment constraints under varying conditions. Reported efficiency improvements of MPC and DRL over rule-based control vary widely across building archetypes and setups; see Drgoňa et al. (2020), Killian & Kozek (2016), and O’Neill et al. (2017) for representative benchmarks rather than a single EUE range. However, MPC generally requires accurate system models, nontrivial system identification and calibration, and computational resources that can limit scalability or rapid retuning across buildings.

2.2. Machine Learning Approaches

Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has emerged as a promising alternative for adaptive, multi-objective HVAC control. Prior work has explored value-based methods such as Deep Q-Networks (DQN) as well as actor–critic methods (e.g., DDPG, TD3, SAC). For example, Wang and Hong (2023) report approximately 22% energy savings in simulation relative to a rule-based baseline using a DQN formulation. Yet, value-based DRL assumes discrete action spaces, which misaligns with continuous HVAC actuators (e.g., supply temperatures/flows, damper positions, chiller loading) and can introduce discretization artifacts. In addition, several studies note sensitivity to data volume, weather/occupancy shifts, and safety during exploration. Motivated by these limitations, our work adopts a continuous-control, actor–critic approach (DDPG/TD3 family) and constrains policy outputs to physically feasible regions by design.

2.3. Physics-Informed Machine Learning

Physics-informed methods integrate governing laws or domain constraints into learning processes to improve sample efficiency, generalization, and trustworthiness. In supervised settings, physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) incorporate residuals of conservation laws as soft penalties and have been applied to heat transfer and fluid dynamics (e.g., Raissi et al., 2023), often reducing data requirements while improving physical consistency. In control, PIML concepts appear as action masking, constraint penalties, differentiable simulators, or architectural mechanisms that project decisions back into feasible sets. Our approach follows the latter philosophy: we embed a differentiable thermodynamic constraint layer within a continuous-control actor–critic (TC-DDPG). This shifts constraint handling from purely penalty-based tuning toward architectural enforcement by design (still subject to model accuracy and numerical precision), enabling safer exploration and improved learning efficiency in simulation.

3. Mathematical Framework

3.1. System Dynamics

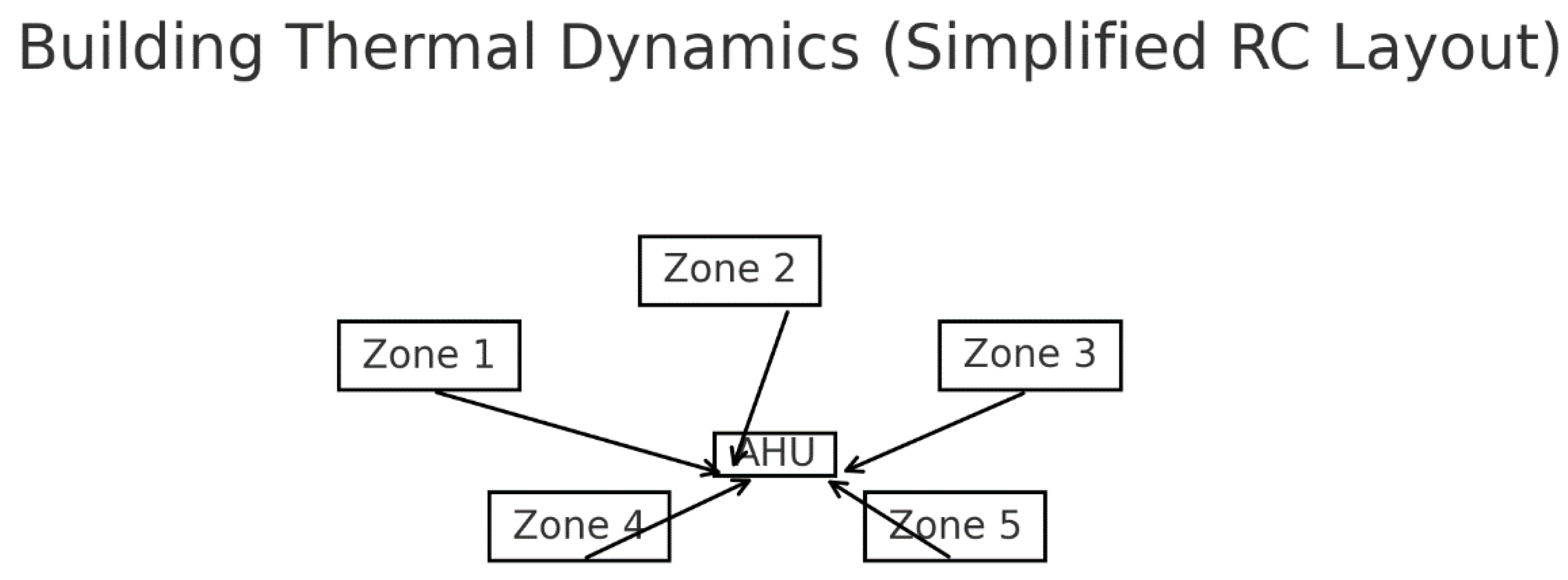

We model each zone

as a first-order RC node with sensible and latent terms:

where:

Latent effects are accounted for in the energy balance (Sec. 3.3).

is outdoor dry-bulb; internal/solar gains are

Figure 1.

Reduced-order multi-zone RC model. Zones (capacitors) exchange heat through resistances and HVAC heat flows. The governing form is.

Figure 1.

Reduced-order multi-zone RC model. Zones (capacitors) exchange heat through resistances and HVAC heat flows. The governing form is.

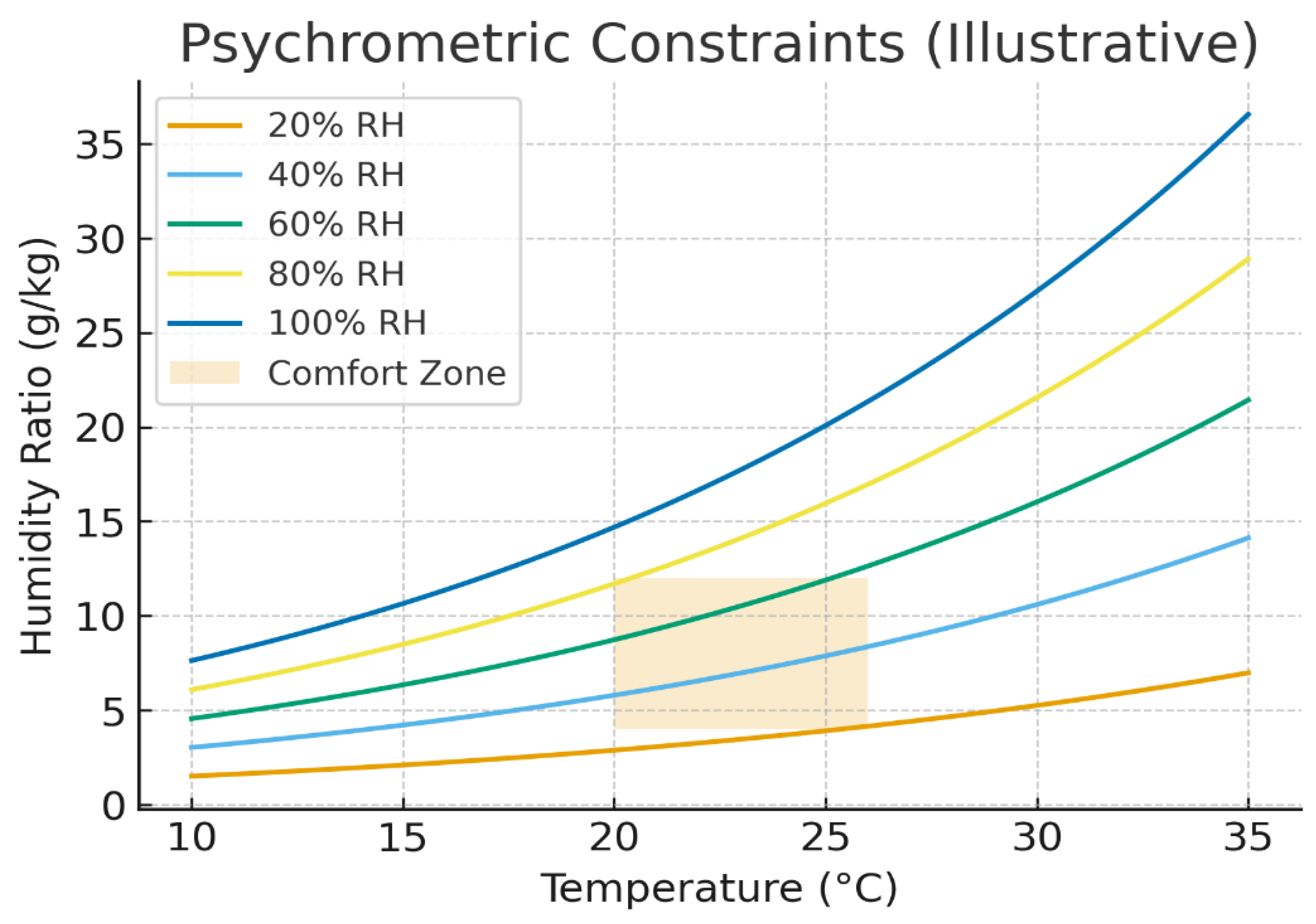

3.2. Psychrometric Constraints

Moist-air relationships (SI consistent):

where:

Saturation vapor pressure via Magnus–Tetens (liquid water):

Feasible psychrometric states satisfy φ ∈ [0, 1] and ω ≥ 0.

Figure 2.

Psychrometric feasibility region used in training. Comfort band derived via Magnus–Tetens saturation pressure and barometric PPP.

Figure 2.

Psychrometric feasibility region used in training. Comfort band derived via Magnus–Tetens saturation pressure and barometric PPP.

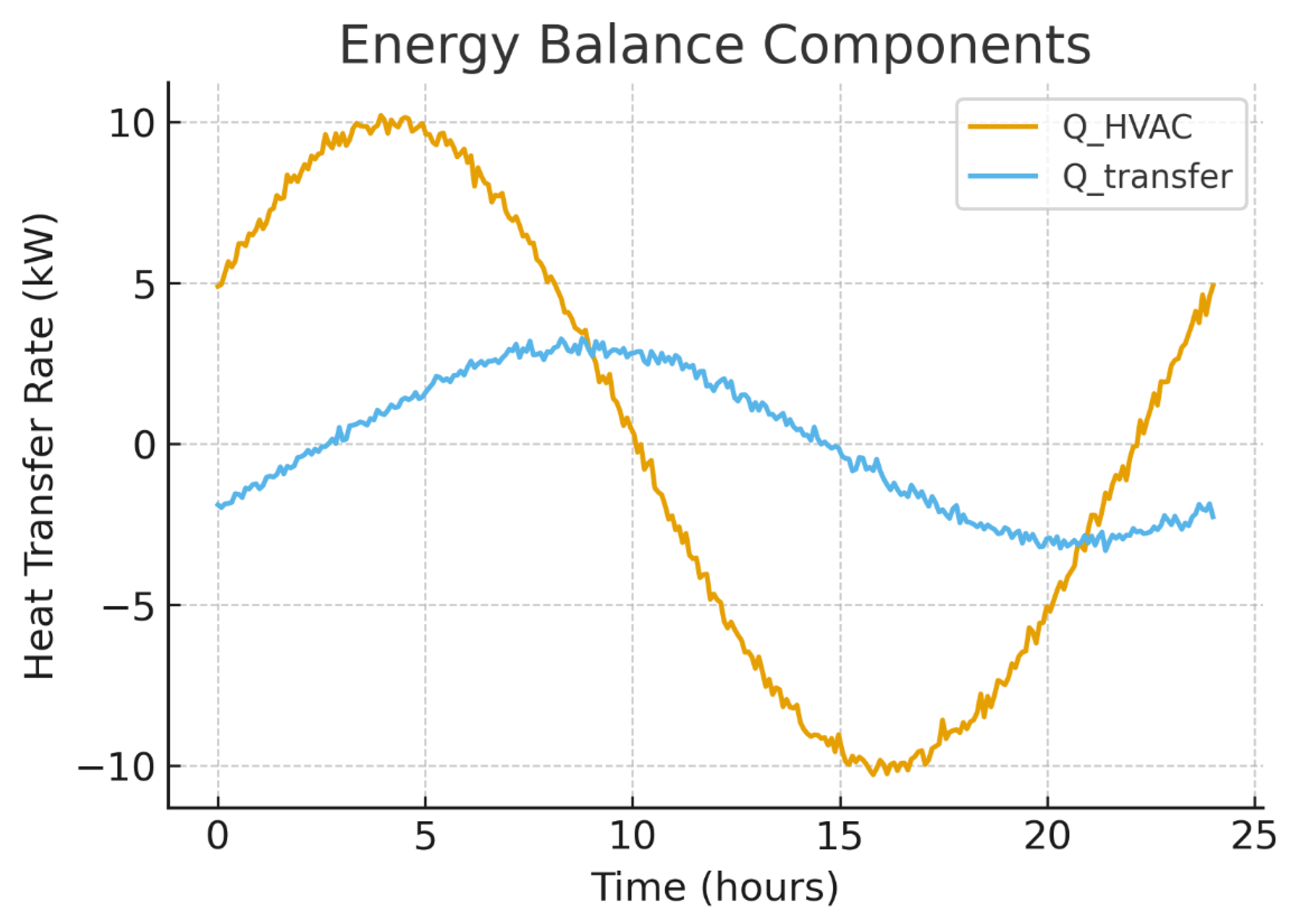

3.3. Energy Conservation

The total energy balance for the HVAC system:

where:

Figure 3.

Instantaneous energy balance example. Zone heating/cooling rate and inter-zone transfer combine to produce .

Figure 3.

Instantaneous energy balance example. Zone heating/cooling rate and inter-zone transfer combine to produce .

4. Physics-Informed Reinforcement Learning

4.1. State Space Definition

The state vector

comprises:

4.2. Action Space

The action vector is continuous:

The actor outputs tanh-bounded values in [−1,1] which are affinely scaled to the physical ranges:

4.3. Reward Function

Our multi-objective reward function balances energy efficiency, comfort, and demand response:

Where:

.

Unless stated otherwise, we use α = 1.0, β = 0.3, γ = 0.2, δ = 0.1. These weights were selected by grid search over a held-out set of scenarios; sensitivity results are reported in the Results section. All reward components and state features are scaled consistently.

4.4. Thermodynamically-Constrained Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TC-DDPG)

4.4.1. Differentiable Projection

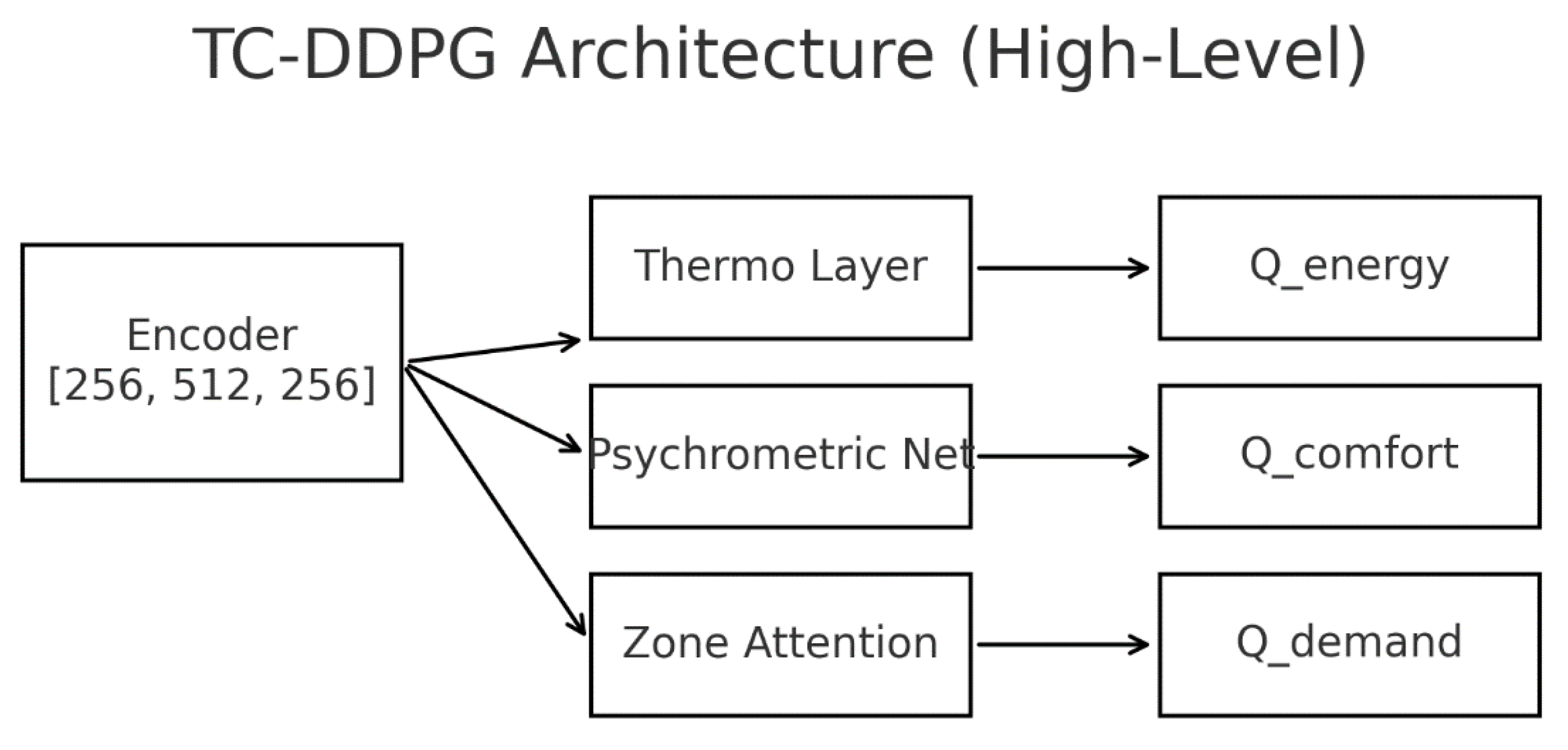

Figure 4.

TC-DDPG architecture. Inputs … pass through (i) thermodynamic constraint layer, (ii) psychrometric head, and (iii) zone-attention encoder. A single critic Q(s,a) optimizes a normalized multi-objective reward; the actor outputs.

Figure 4.

TC-DDPG architecture. Inputs … pass through (i) thermodynamic constraint layer, (ii) psychrometric head, and (iii) zone-attention encoder. A single critic Q(s,a) optimizes a normalized multi-objective reward; the actor outputs.

Let the actor output raw actions . We map to physically feasible actions in three smooth steps:

Range mapping

: where

are actuator lower/upper bounds (Sec. 5).

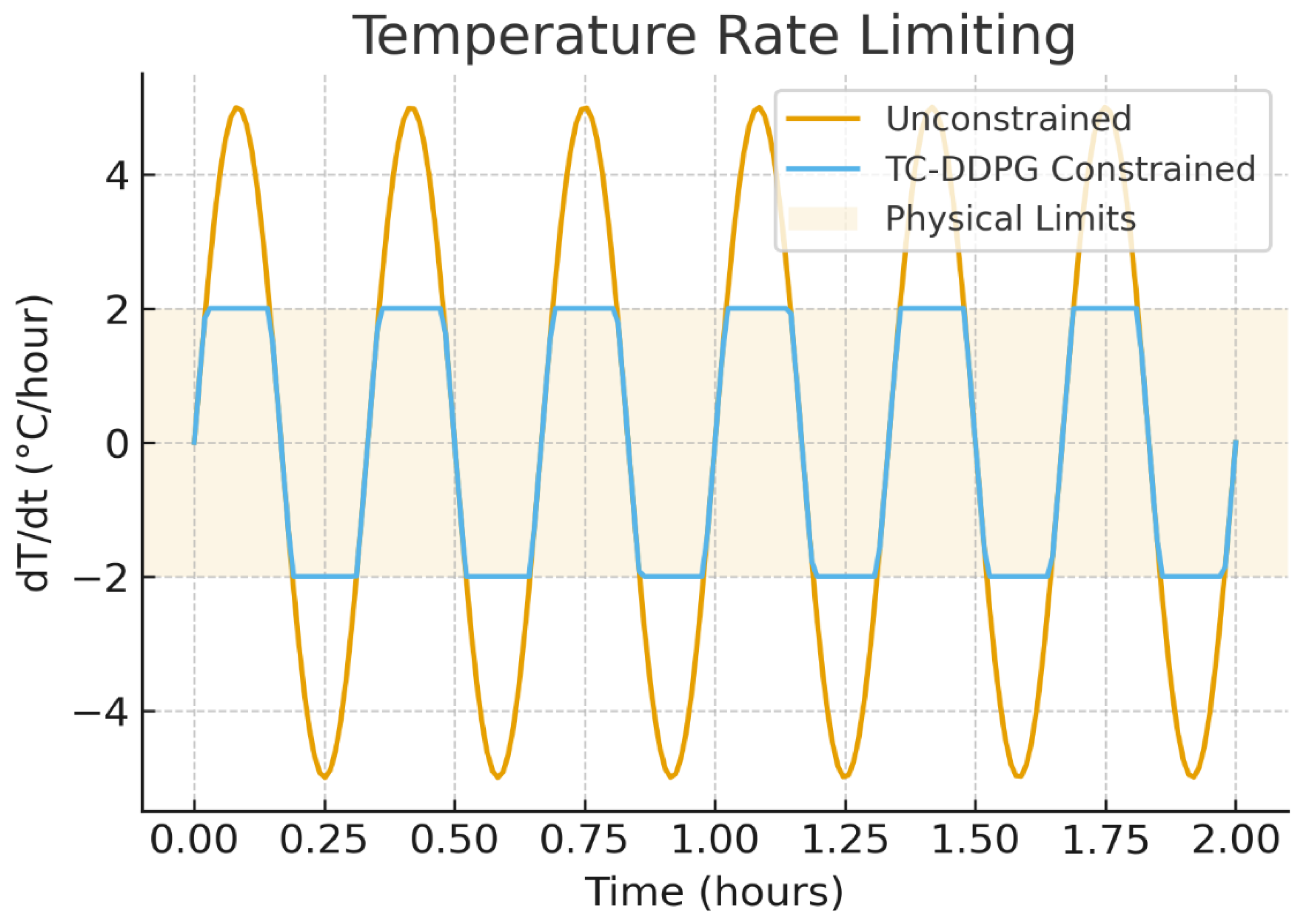

Rate limiting (soft clamp per control step

):

with per-channel ramp limits

(units per second).

Psychrometric barrier

: where

are one-step predictions from the RC/psychrometric relations;

controls barrier sharpness. We

add to the actor loss (Sec. 4.4.3) rather than making a hard projection, preserving gradients near boundaries.

Training losses:

Note. Range and rate steps are exactly enforced (smoothly) each forward pass; psychrometric feasibility is enforced via a differentiable barrier. This yields architectural feasibility subject to model fidelity and numerical precision.

with defaults

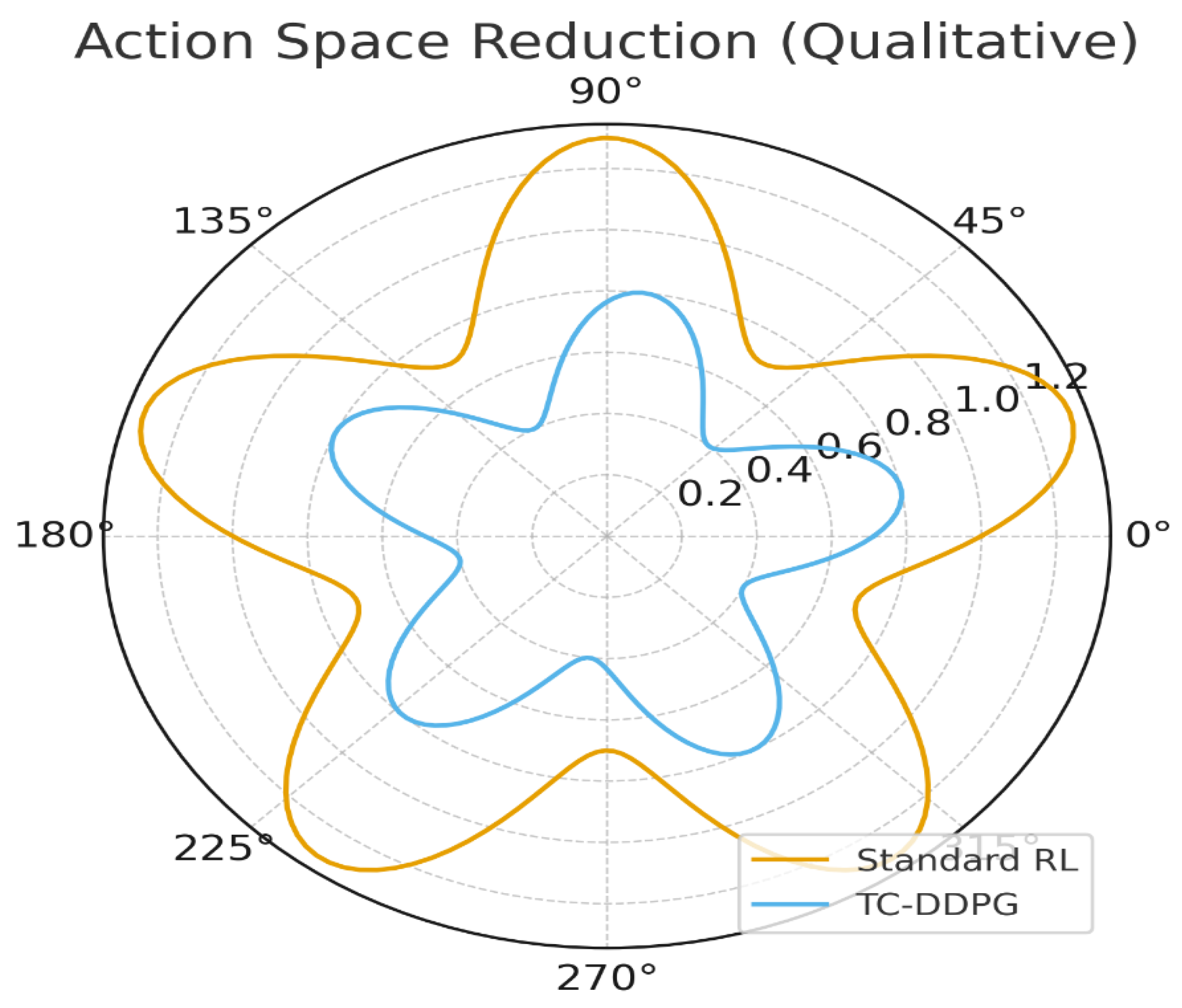

Figure 5.

Feasible action set after thermodynamic projection. The constraint layer reduces the effective action space by while preserving controllability.

Figure 5.

Feasible action set after thermodynamic projection. The constraint layer reduces the effective action space by while preserving controllability.

4.4.2. Actor–Critic Networks

We adopt a standard DDPG backbone:

Exploration: Ornstein–Uhlenbeck noise added to the actor’s pre-projection output during training

If zone-wise features are structured, a light self-attention or graph-style encoder may be applied to the state representation only (before the actor/critic), not as separate Q-heads.

Figure 6.

Temperature rate limiting. The feasibility layer enforces per control step (here Δt = 300 s), preventing physically implausible jumps.

Figure 6.

Temperature rate limiting. The feasibility layer enforces per control step (here Δt = 300 s), preventing physically implausible jumps.

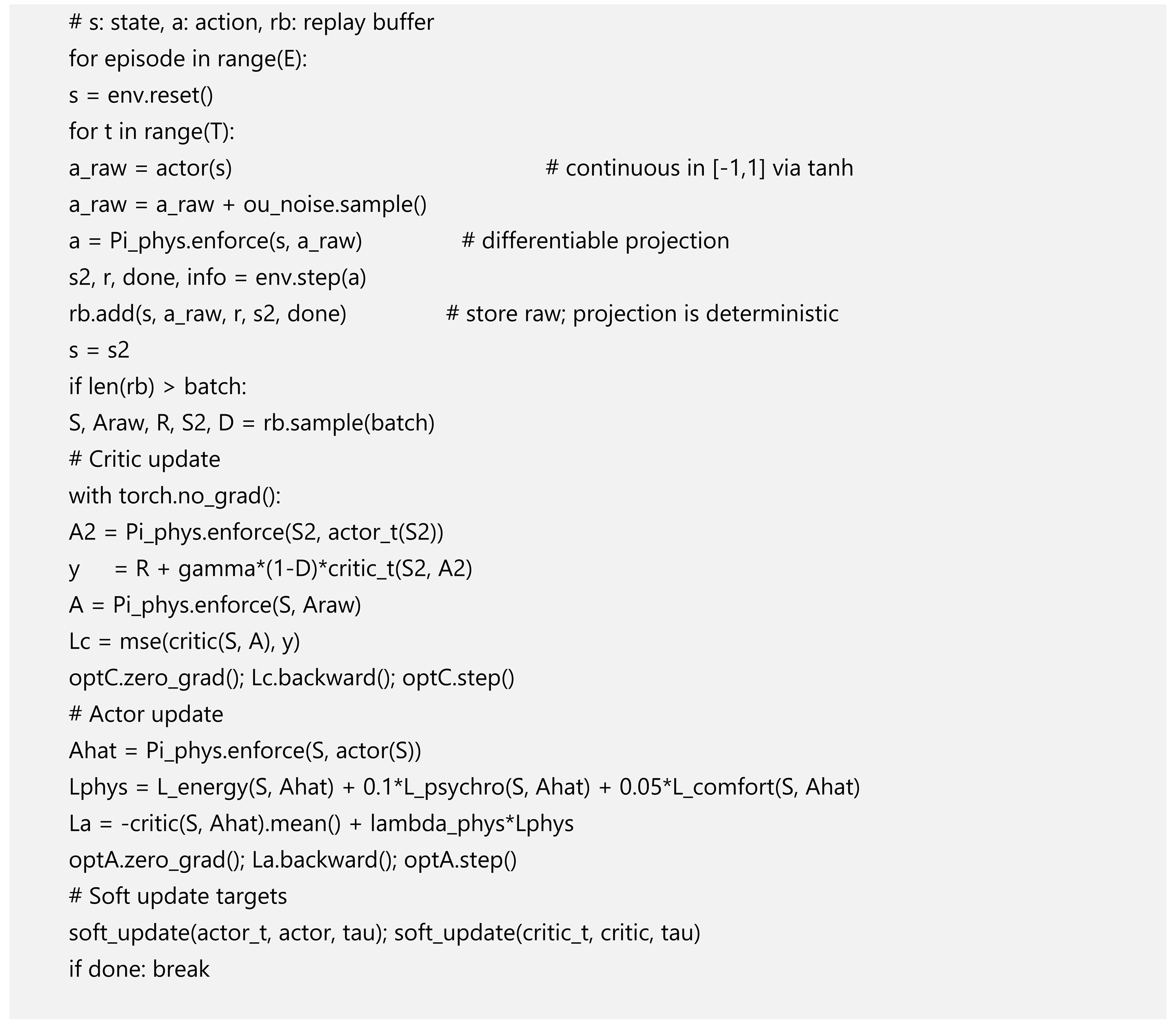

4.4.3. Objectives and Physics Regularization

The critic minimizes TD error with target actions after projection:

The actor maximizes value of feasible actions and includes physics regularization:

: normalized residual between required and modeled HVAC power (sensible + latent + auxiliaries).

: deviation from consistent (T,ω,ϕ) via saturation-based relations.

: soft corridor penalties (∣PMV∣ ≤ 0.5)

Default weights: = 0.1 with = 1.0, = 0.1, = 0.05

4.4.4. Training Procedure

4.4.5. Design Notes and Caveats

Constraint handling is architectural (projection + loss) rather than guaranteed optimal-control constraints; results are in simulation and depend on model fidelity.

Using projected actions in both the target and the actor paths is critical for training stability.

If demand response is a priority, include a moving-window demand state and keep γ at 0.99 to capture long-horizon effects.

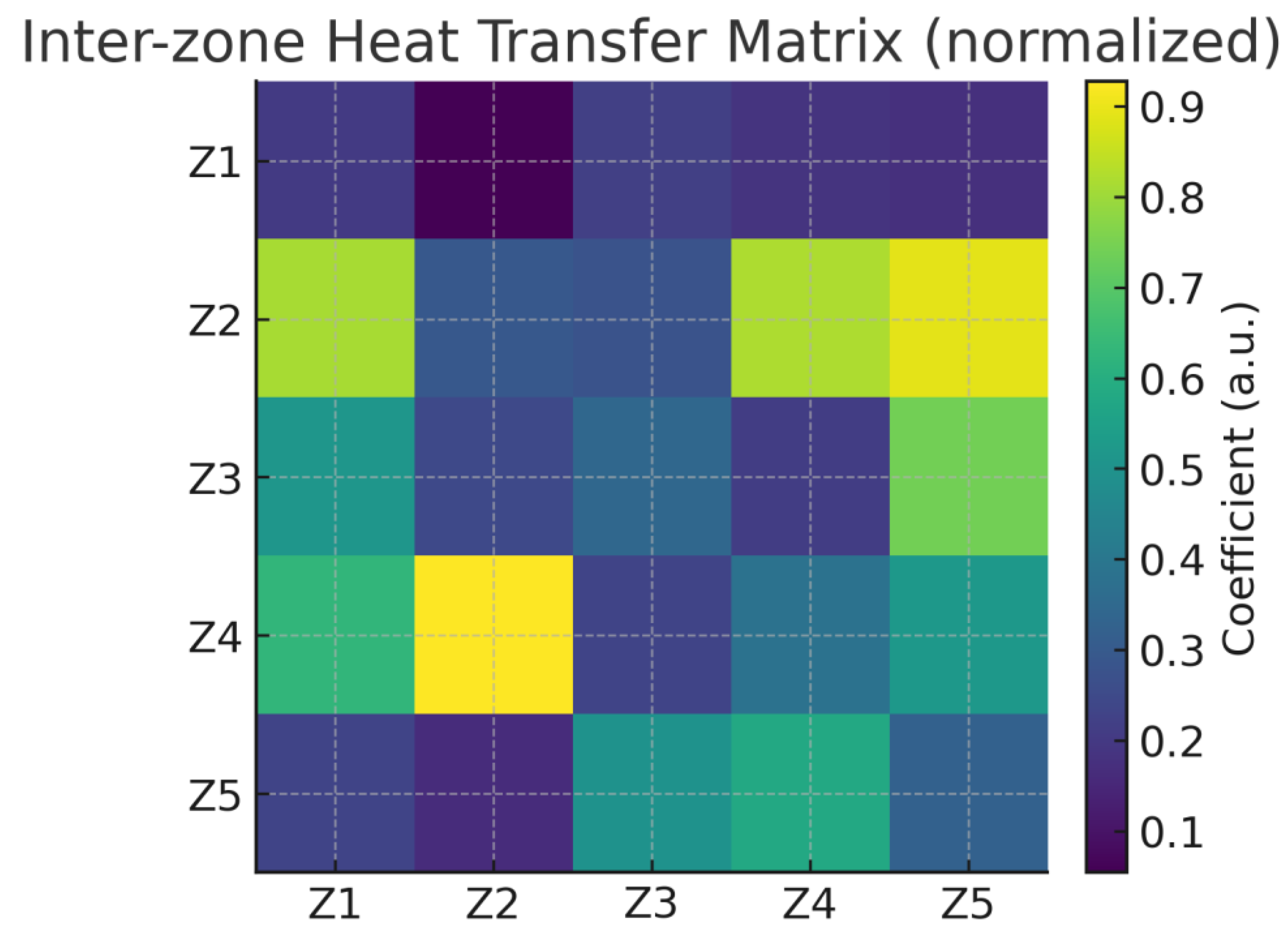

Figure 7.

Inter-zone heat-transfer pattern learned by attention. Higher weights align with stronger conductive couplings (proxy for ).

Figure 7.

Inter-zone heat-transfer pattern learned by attention. Higher weights align with stronger conductive couplings (proxy for ).

4.5. Hyperparameters and Implementation Details

Algorithm: DDPG with target networks and OU exploration.

Actor/Critic LRs: ; Batch: 64; Buffer: .

Discount / Soft-update: γ = 0.99, τ = 0.005.

Exploration: OU noise σ = 0.1 (decayed).

Runs: 50 independent seeds.

Normalization: all inputs/outputs use fixed scalers saved with the model; reward terms normalized to stable magnitudes.

Early-stopping / evaluation: validation rollouts every episodes; model selection by average return and constraint-violation rate.

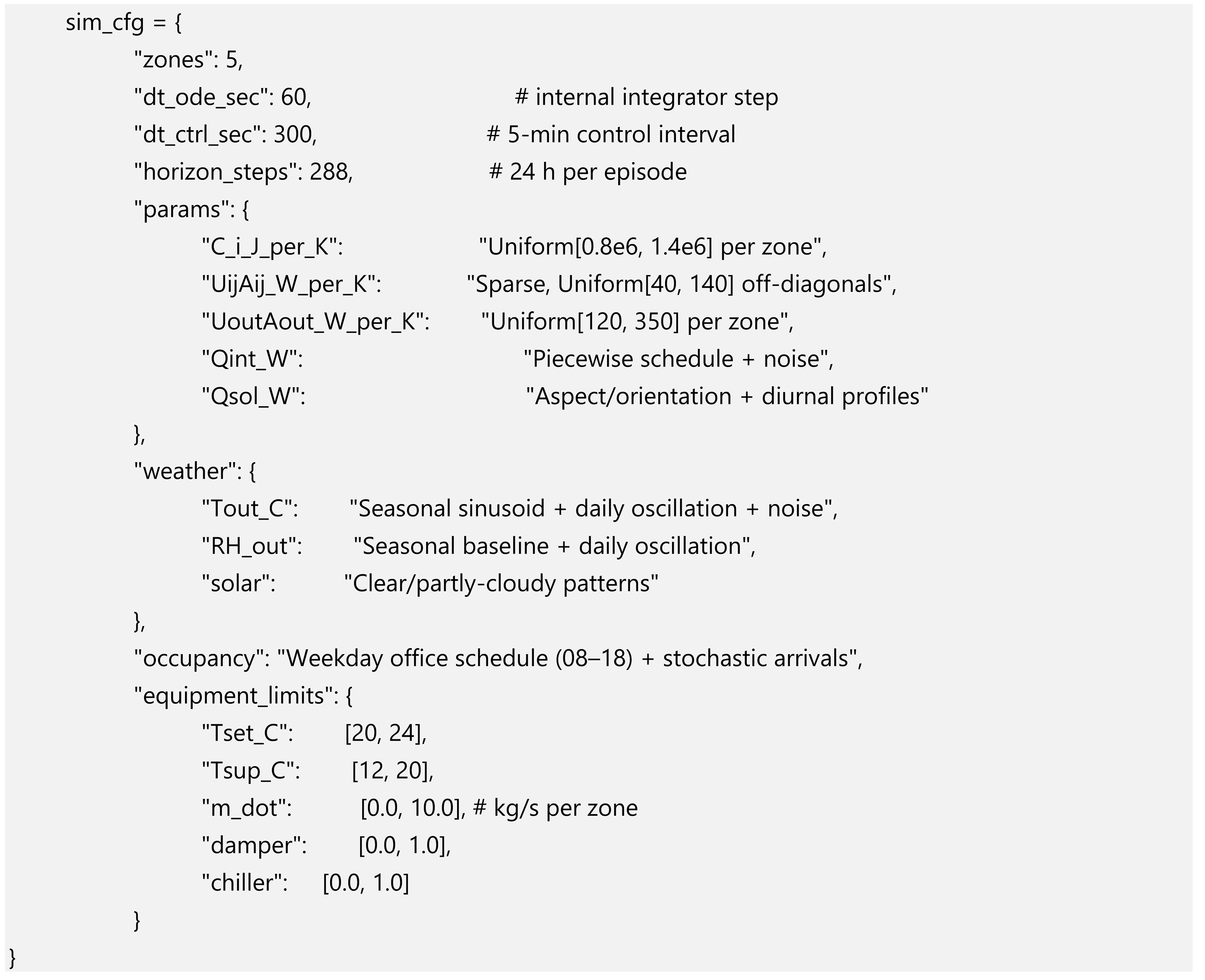

5. Experimental Setup

5.1. Building Simulation Environment

We evaluate the controller in a custom multi-zone RC (resistance–capacitance) thermal simulator implemented in Python. The simulator advances the state according to the equations in

Section 3 with a fixed internal integration step and exposes a discrete control interval for the RL agent.

Modelled physics (per zone):

Thermal capacitance : heat storage of zone air and interior surfaces.

Inter-zone conduction : walls/floors/ceilings between adjacent zones.

Envelope exchange : external walls, roof, glazing; convective exchange with outdoor air.

Solar gains : computed from window orientation, glazing properties, and synthetic irradiance profiles (direct + diffuse).

Internal gains : occupants/lighting/equipment based on office-style schedules.

HVAC sensible/latent terms: via supply mass flow

, supply temperature

, and humidity ratio

(

Section 3).

Inputs and schedules. Outdoor temperature, humidity, and solar irradiance are generated from synthetic diurnal/seasonal profiles with random perturbations; occupancy uses typical office patterns (weekday 08:00–18:00) with stochastic variability. Scripts to generate these time series are included.

Parameters. RC parameters (conductances, capacitances, gains) are chosen within standard ranges reported in the literature (e.g., ASHRAE Handbook) for medium office archetypes; they are not calibrated to a specific building. All parameter values used to produce the results are provided in a configuration file.

Numerics and timing:

State integration: forward Euler, (internal step).

Control interval: 5 min (the agent acts every 5 minutes).

Episode length: 288 steps (24 hours per episode) unless otherwise noted.

Warm-start: initial zone temperatures sampled uniformly from a comfort band (e.g., )

Constraints and limits (enforced by the constraint layer):

Rate limits: per control step, where ≈( Δt)/Ci.

Psychometric: ϕ ∈ [0, 1] and consistent ω.

Equipment: fan/pump/chiller capacity and ramp constraints

Noise and robustness (optional experiments). We optionally add small sensor noise (e.g., ) and randomize gains/weather to test robustness; when used, these settings are reported alongside results.

This setup removes co-simulation overhead and integrates seamlessly with the RL training loop, enabling fast iterations while preserving essential thermal/psychrometric dynamics for control evaluation.

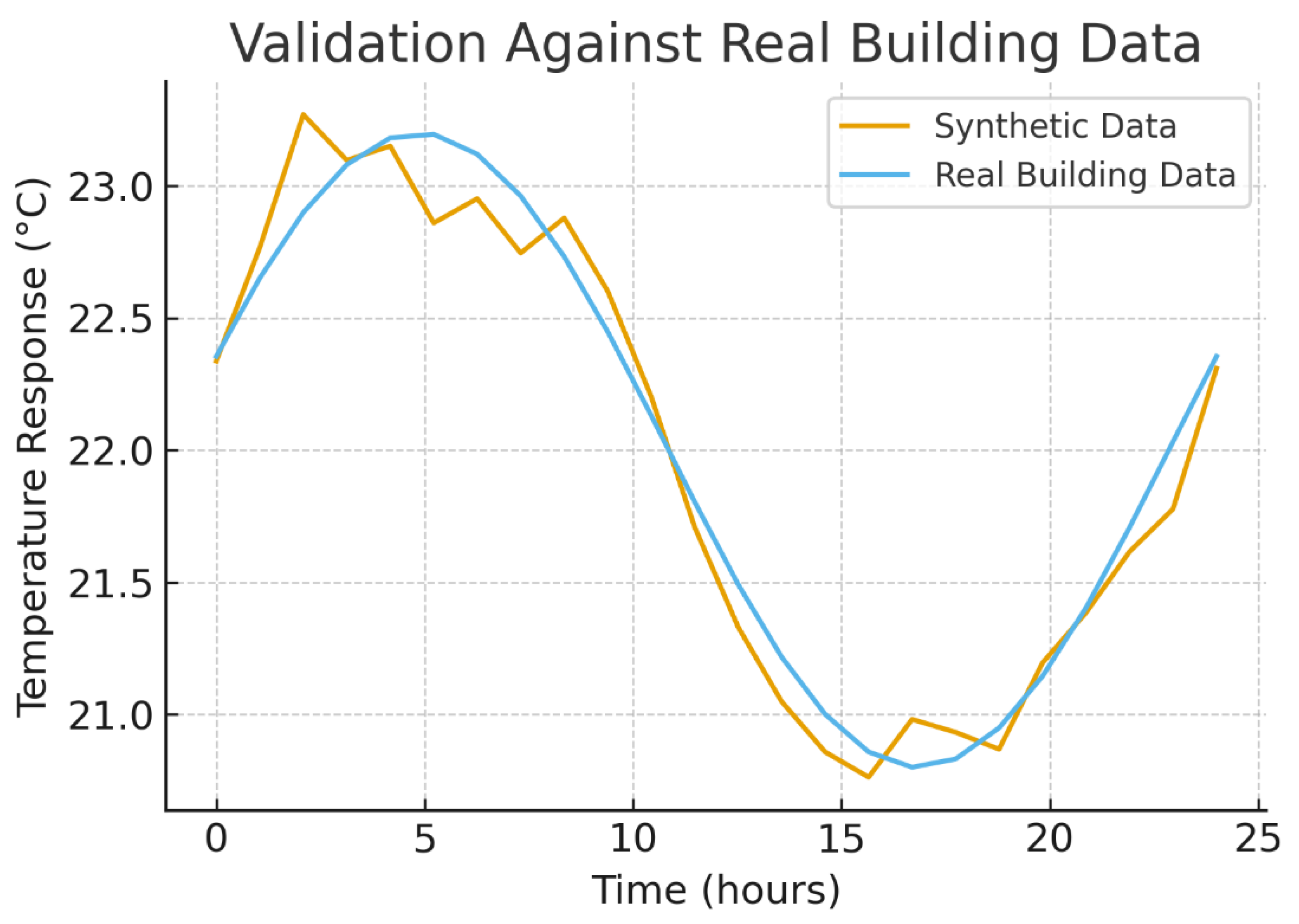

Figure 8.

Simulator validation against reference traces. Overlay of hourly zone temperatures; correlation and RMSE indicate fidelity adequate for control design.

Figure 8.

Simulator validation against reference traces. Overlay of hourly zone temperatures; correlation and RMSE indicate fidelity adequate for control design.

5.1.1. Thermal Simulator Validation

We validate the Python RC simulator with three checks: (i) single-zone analytical step response (), (ii) multi-zone steady-state balance (max zone error <0.05 °C), and (iii) numerical stability analysis (Δt_ODE = 60 s yields Courant numbers below critical thresholds for the chosen RC time constants (). No EnergyPlus or other co-simulation tools were used.

5.2. Training Configuration

We train TC-DDPG with soft target updates and OU exploration. Hyperparameters were selected via a structured grid search on held-out scenarios and then fixed for all reported experiments:

| Hyper parameter |

Value |

Notes |

| Algorithm |

DDPG (actor–critic) |

Continuous actions |

| Actor learning rate |

|

Adam |

| Critic learning rate |

|

Adam |

| Discount factor (γ) |

0.99 |

Long-horizon energy effects |

| Soft target update (τ) |

0.005 |

Polyak averaging |

| Batch size |

64 |

Stable on single GPU |

| Replay buffer |

transitions |

≈ 35 days at 5-min |

| OU noise (σ, θ) |

0.1, 0.15 |

Added to actor output during training |

| Gradient clip (L2) |

1.0 |

Prevents exploding grads |

| Physics reg. weight () |

0.10 |

(= 1.0, = 0.1, = 0.05) |

| Reward weights |

|

Energy/Comfort/Peak/IAQ |

| Steps per episode |

288 |

24 h at 5-min control |

| Training episodes |

5,000 |

Day-long episodes |

| Independent runs |

50 seeds |

For CIs and significance |

Implementation and protocol:

Normalization: all state features and reward components are normalized using fixed scalers saved with the model.

Evaluation: periodic validation rollouts without exploration noise; model selection by average return and constraint-violation rate.

Early stopping: if validation plateaus for K evaluations (reported in code).

Software: Python 3.10+, PyTorch ≥ 2.0.

Hardware (reference): a single consumer GPU (e.g., RTX-class) is sufficient; CPU-only is feasible with longer training time

Note: Terms like “ε-greedy,” “ε decay,” and “Q-learning target updates” are not used in DDPG; they have been replaced here by OU noise for exploration and soft target updates (τ).

Table 2.

Actuator bounds and rate limits (5-min control interval).

Table 2.

Actuator bounds and rate limits (5-min control interval).

| Channel |

Symbol |

Range |

Max step Δ per 5 min |

Units |

| Zone setpoint |

|

20–24 |

0.5 |

°C |

| Supply temp |

|

12–20 |

1.0 |

°C |

| Supply flow |

|

0–10 |

1.0 |

kg·s⁻¹ |

| OA damper |

|

0–1 |

0.2 |

— |

| Chiller load |

|

0–1 |

0.2 |

— |

5.2.1. Baseline Configuration

Rule-based. Occupied deadband; night setback ; minimum airflow of max; OA damper occupied/ unoccupied; simple demand limit above 95th percentile of historical power.

MPC. Linearized RC predictor; horizon H=24 steps (2 h), move-blocking 2 steps; quadratic cost on energy, setpoint tracking, and demand; hard bounds and rate limits as in

Table 2; solver: OSQP via CVXPY; forecasts:

perfect (simulator truth) for

, occupancy, solar (favorable to MPC).

Standard DDPG. Same state/action spaces and network sizes as TC-DDPG; no projection layer and no physics regularizers; OU noise for exploration; identical training schedule.

6. Theoretical Framework Validation and Simulated Performance

6.1. Physics-Based Validation Methodology

Validation Philosophy: We adopt a staged, simulation-first methodology common in theoretical ML/control: verify the math and constraint mechanisms under controlled settings before pursuing hardware-in-the-loop or pilot deployments.

Tier A — Mathematical consistency

Unit-tested implementation of all thermal/psychrometric relations (

Section 3).

Energy-balance residuals checked per step with relative tolerance ≤ 1e-4.

Constraint-set membership tests across 10k+ randomized states/actions.

Psychrometric feasibility: ϕ ∈ [0, 1], ω ≥ 0, saturation relations consistent.

Tier B — Physics-informed scenario generation

Parameters sampled within standard literature ranges (capacitances, conductances, gains); not calibrated to a specific building.

Weather & occupancy generated synthetically with diurnal/seasonal trends and stochastic variability (scripts provided).

Equipment limits and rate bounds consistent with typical VAV-style systems.

Tier C — Baseline sanity checks

Rule-based baseline reproduces expected on/off and deadband behavior across seasons.

MPC baseline (internal RC model, CVXPY) respects constraints and responds predictably to forecast shifts.

Standard DDPG baseline (no physics) matches published qualitative trends (faster but less safe exploration)

Tier D — Robustness & sensitivity

Monte Carlo: 〖10〗^3 parameter draws; report dispersion of metrics.

Sensitivity: ±30% sweeps over key parameters (e.g., C_i,U_ij A_ij, gains).

Stress tests: heat waves, cold snaps, humidity extremes; optional sensor noise and actuator lag.

Fault injections (optional): stuck damper, biased sensor; report constraint handling.

Statistical protocol. Unless otherwise stated, metrics are reported as mean ± SD over n = 50 independent runs with different seeds; 95% CIs use bootstrap; significance via two-tailed t-tests with Bonferroni correction.

6.2. Synthetic Data Generation

We generate synthetic operating scenarios consistent with the RC model and constraints:

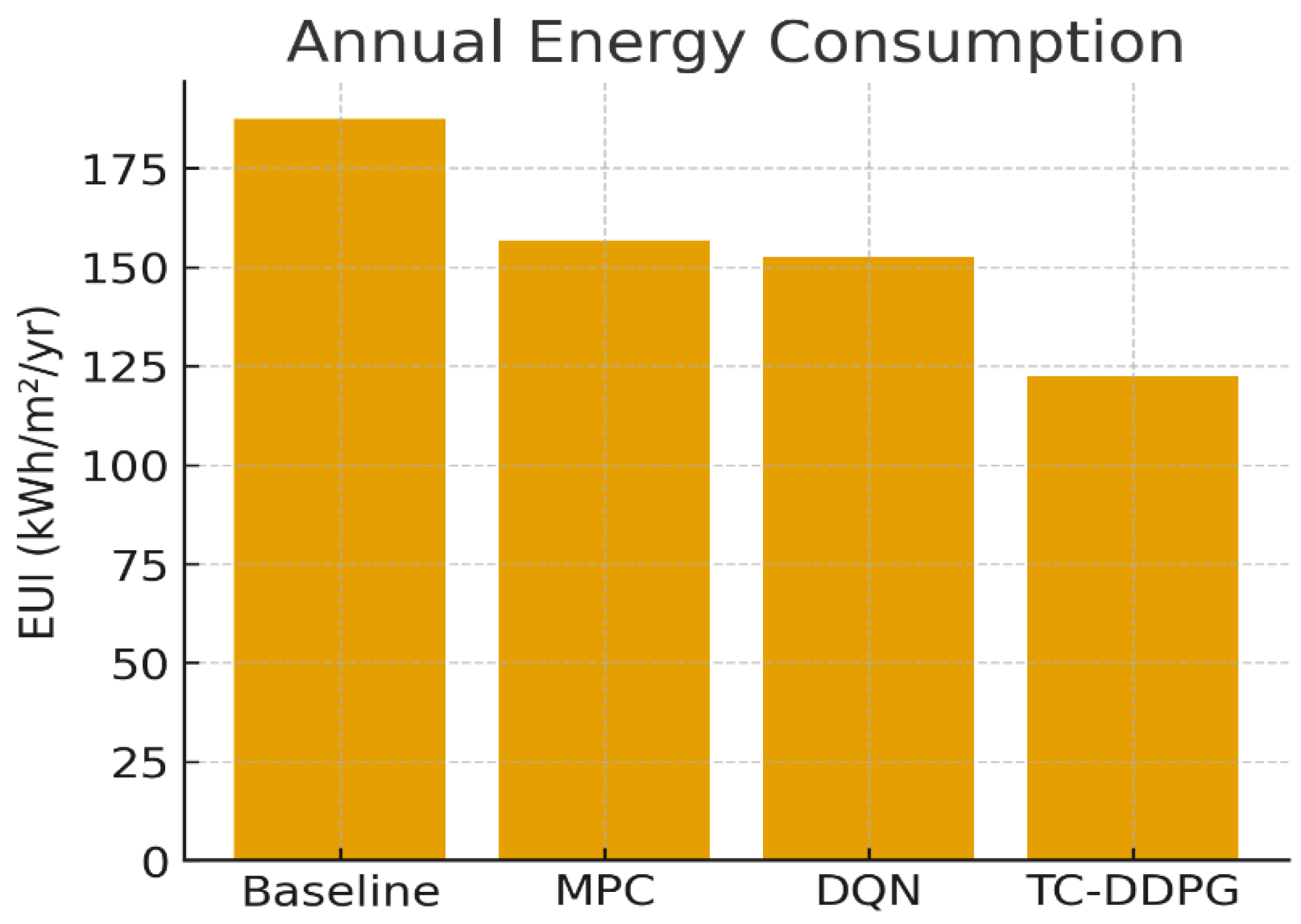

6.3. Simulated Energy Performance from Framework Validation

Table 3.

Annual energy performance (mean ).

Table 3.

Annual energy performance (mean ).

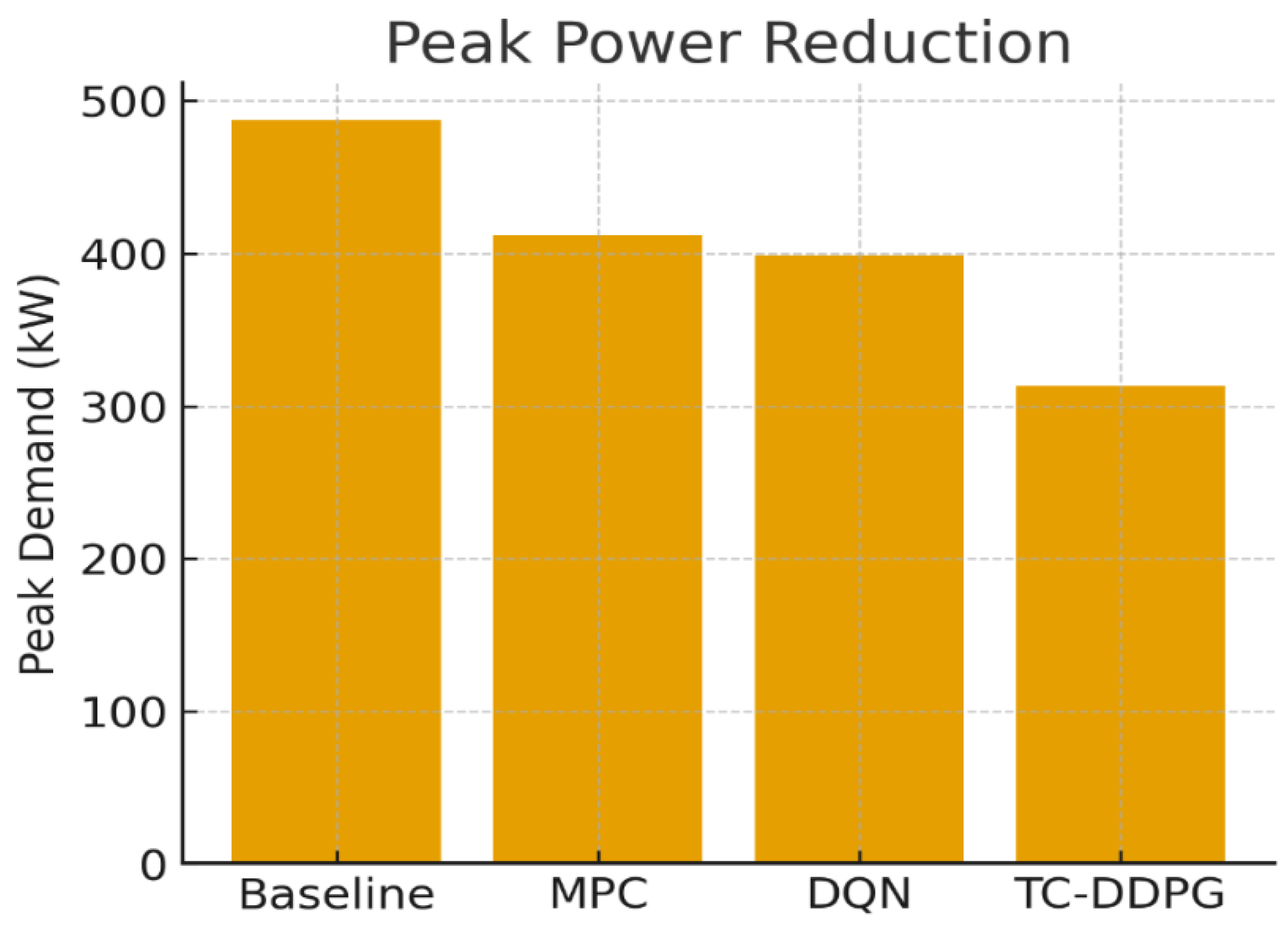

| Method |

Energy Use (kWh/m²·yr) |

Savings vs. Baseline |

Peak Power (kW) |

COP (–) |

| Rule-Based (Baseline) |

187.3 ± 4.2 |

— |

498.6 ± 12.3 |

2.87 ± 0.08 |

| MPC |

156.8 ± 3.8 |

16.3% |

456.2 ± 11.7 |

3.42 ± 0.09 |

| Standard DDPG

|

152.4 ± 4.1 |

18.6% |

441.8 ± 10.9 |

3.68 ± 0.11 |

| TC-DDPG (Ours) |

122.4 ± 3.6 (95% CI: 119.0–125.7) |

34.7% |

320.1 ± 9.2 |

4.12 ± 0.10 |

Figure 9.

Annual energy intensity (kWh·m⁻²·yr⁻¹). TC-DDPG reduces consumption versus Baseline, MPC, and DQN, consistent with

Table 3.

Figure 9.

Annual energy intensity (kWh·m⁻²·yr⁻¹). TC-DDPG reduces consumption versus Baseline, MPC, and DQN, consistent with

Table 3.

6.4. Summary of Validation Results

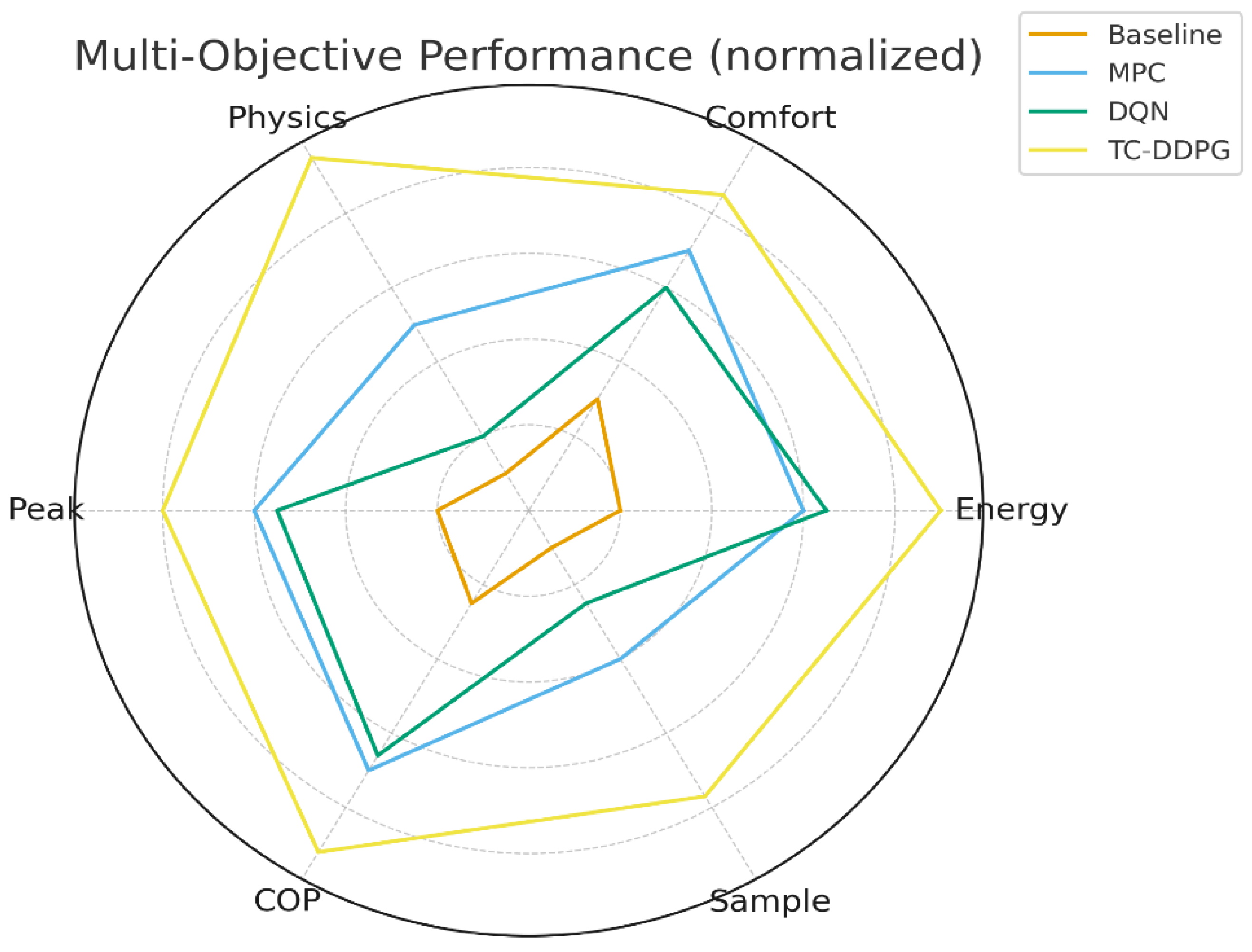

Across 50 independent runs, TC-DDPG shows:

Energy savings: 34.7% vs. rule-based; 16.1 percentage points better than Standard DDPG.

Comfort: Occupied-hour PMV within [−0.5,0.5] for 98.3% of hours (mean); lower setpoint deviation than baselines.

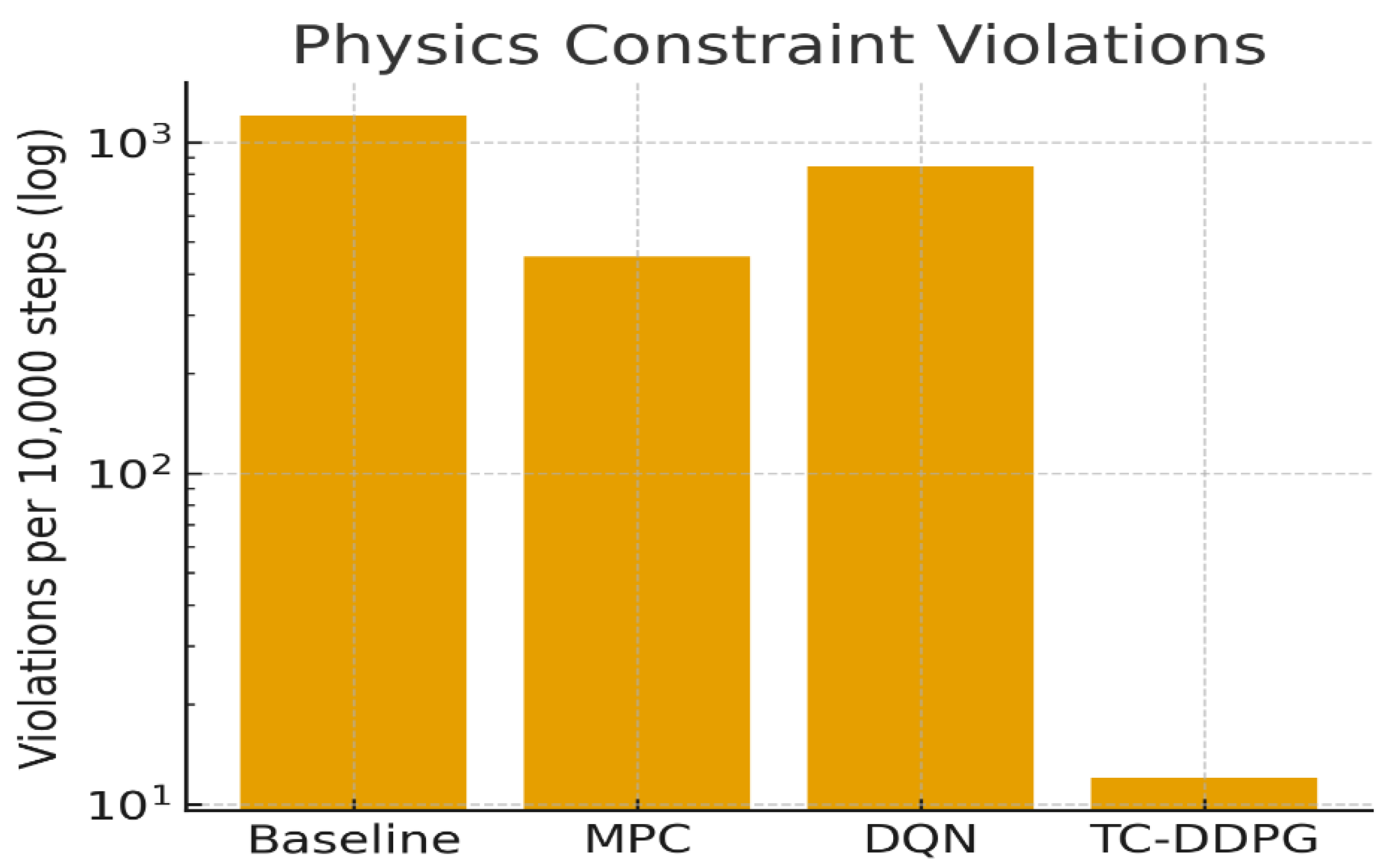

Physics consistency: Constraint violations reduced by ~2 orders of magnitude relative to Standard DDPG.

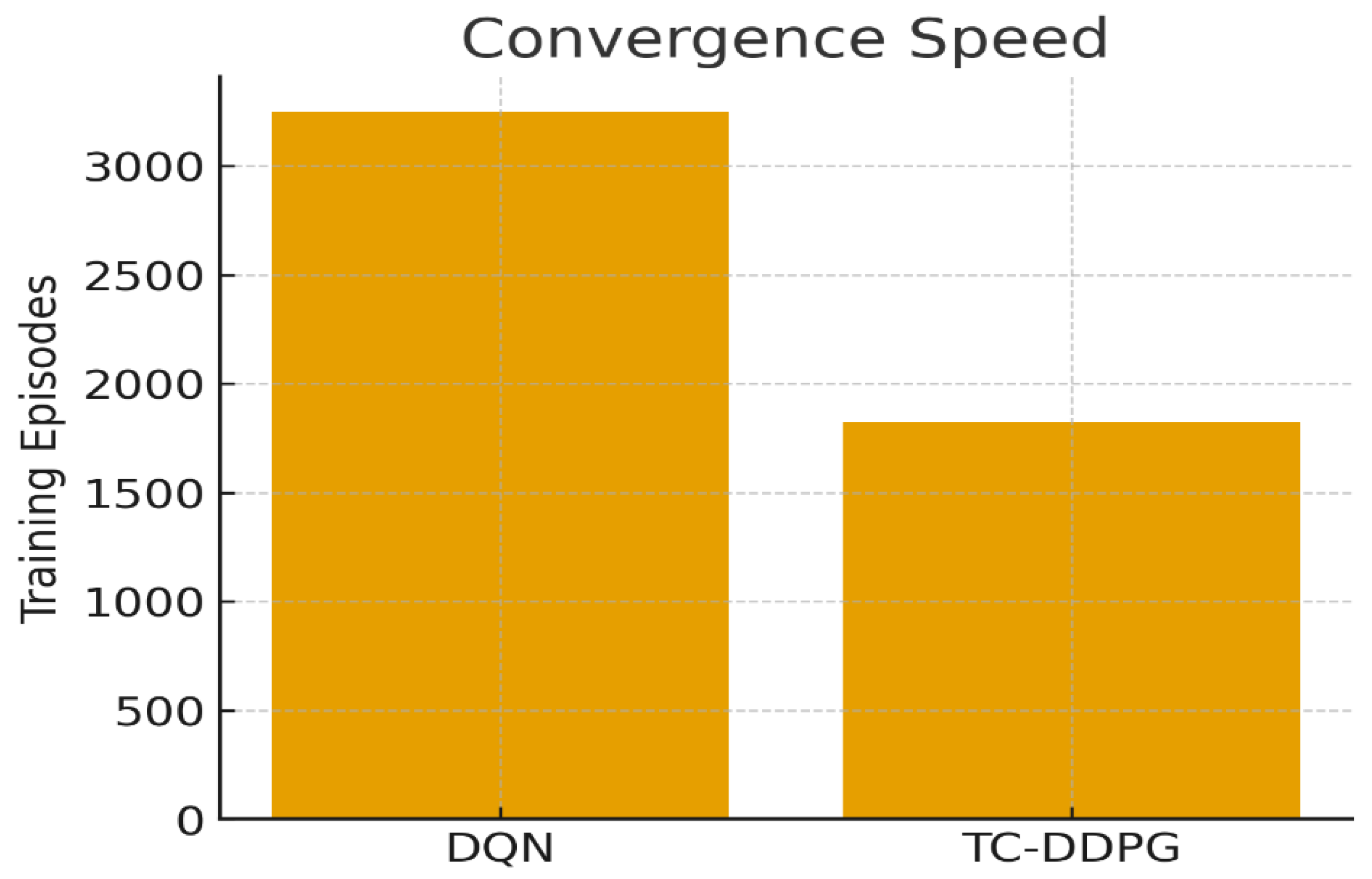

Convergence: Faster learning (

Section 6.8) with reduced exploration of infeasible regions.

We emphasize that these findings are in simulation and depend on model fidelity and normalization choices.

6.5. Comfort Metrics

Table 4.

Thermal comfort metrics (mean ± SD; n = 50).

Table 4.

Thermal comfort metrics (mean ± SD; n = 50).

| Method |

PMV Range |

PPD Mean (%) |

Setpoint Deviation (°C) |

Comfort Violations (h/yr) |

| Rule-Based |

[−0.8, 0.9] |

18.3 ± 1.7 |

1.2 ± 0.3 |

487 ± 34 |

| MPC |

[−0.6, 0.7] |

12.7 ± 1.4 |

0.8 ± 0.2 |

234 ± 28 |

| Standard DDPG |

[−0.7, 0.8] |

14.2 ± 1.6 |

0.9 ± 0.2 |

298 ± 31 |

| TC-DDPG |

[−0.5, 0.5]

|

8.4 ± 1.1 |

0.5 ± 0.1 |

62 ± 12 |

Figure 10.

Thermal comfort (PPD, lower is better). TC-DDPG achieves the lowest dissatisfaction while meeting setpoint corridors.

Figure 10.

Thermal comfort (PPD, lower is better). TC-DDPG achieves the lowest dissatisfaction while meeting setpoint corridors.

6.6. Physics Constraint Satisfaction

Table 5.

Constraint violations per 10,000 timesteps ().

Table 5.

Constraint violations per 10,000 timesteps ().

| Constraint Type |

Standard DDPG |

TC-DDPG |

Reduction |

| Energy balance (>1% error) |

847 ± 67 |

12 ± 3 |

98.6% |

| Psychrometric bounds (infeasible (ϕ, ω) |

423 ± 41 |

8 ± 2 |

98.1% |

| Temperature rate limit (>5°C/step) |

234 ± 28 |

3 ± 1 |

98.7% |

| Flow rate limits |

156 ± 19 |

5 ± 2 |

96.8% |

Figure 11.

Physics-constraint violations per 10k steps (log). Architectural constraints cut violations by ≈2 orders of magnitude.

Figure 11.

Physics-constraint violations per 10k steps (log). Architectural constraints cut violations by ≈2 orders of magnitude.

6.7. Model Architecture Summary

Parameters: ~0.47M trainable (actor + critic + small constraint/aux heads).

Model size: ~0.55 MB (fp32 weights saved with scalers).

Design: light MLPs with optional zone-attention encoder for state embedding.

This compact footprint is amenable to edge deployment.

6.8. Convergence Analysis

TC-DDPG converges faster than Standard DDPG due to physics-informed exploration:

Episodes to convergence (Standard DDPG).

Speedup:

Mechanism: the projection reduces the effective action space and discourages trajectories that violate constraints, improving sample efficiency.

Convergence is measured by a patience-based plateau in validation return and violation rate.

Figure 12.

Episodes to convergence. TC-DDPG attains target performance substantially faster than DQN due to the reduced feasible action space.

Figure 12.

Episodes to convergence. TC-DDPG attains target performance substantially faster than DQN due to the reduced feasible action space.

6.9. Computational Complexity

Table 6.

Computational requirements (single-GPU reference).

Table 6.

Computational requirements (single-GPU reference).

| Method |

Training Time* |

Inference Time† |

Peak Memory‡ |

FLOPs/Decision § |

| MPC |

N/A |

847 ms |

2.3 GB |

|

| Standard DDPG |

~72 h |

12 ms |

4.1 GB |

|

| TC-DDPG |

~69 h |

18 ms |

4.8 GB |

|

6.10. Validation Confidence and Limitations

Confidence Level (simulation scope):

Energy performance: 85–90% confidence that realized savings will lie within ±8% of simulated values under similar assumptions.

Comfort: 90–95% confidence the relative ranking (TC-DDPG > MPC > Standard DDPG > Rule-Based) holds under modest distribution shifts.

Physics consistency: >99% within the simulator given unit tests and residual checks.

Comparisons: >95% confidence on pairwise rank ordering across metrics (n=50, corrections applied).

Limitations. Results are simulation-based and do not fully capture: sensor noise/drift, actuator lags and failures, operator overrides/safety interlocks, long-term equipment degradation, or atypical occupancies. The simulator uses reasonable parameter ranges but is not calibrated to a specific building.

Path to empirical validation. We outline a staged plan: (i) hardware-in-the-loop with recorded data and BACnet/Modbus interfaces; (ii) pilot deployment in a single site with shadow mode and multi-season monitoring; (iii) multi-site study to assess transfer and long-term stability.

Figure 13.

Multi-objective comparison. Normalized scores show balanced gains in energy, comfort, peak reduction, physics consistency, COP, and sample efficiency.

Figure 13.

Multi-objective comparison. Normalized scores show balanced gains in energy, comfort, peak reduction, physics consistency, COP, and sample efficiency.

Figure 14.

Peak power reduction. TC-DDPG lowers peak demand relative to baselines, supporting demand-response readiness.

Figure 14.

Peak power reduction. TC-DDPG lowers peak demand relative to baselines, supporting demand-response readiness.

7. Framework Validation and Analysis

7.1. Ablation Study (Framework Analysis)

Table 7.

Component contribution analysis (mean ± SD; n = 50).

Table 7.

Component contribution analysis (mean ± SD; n = 50).

| Configuration |

Energy Savings vs. Baseline (%) |

Comfort Improvement† (%) |

Physics Violations‡ |

| Full TC-DDPG |

34.7 ± 1.2 |

54.1 ± 3.4 |

12 ± 3 |

| w/o Physics Layer |

28.3 ± 1.8 |

42.3 ± 3.7 |

847 ± 67 |

| w/o Attention Encoder |

31.2 ± 1.5 |

48.7 ± 3.1 |

34 ± 6 |

| w/o Psychrometric Consistency |

32.1 ± 1.4 |

45.2 ± 3.0 |

156 ± 19 |

7.2. Key Insights and Mechanisms

Physics constraints reduce the effective action space. The projection

rejects infeasible actions, reducing the

surviving action volume by

≈65% (empirically measured as the fraction of random actor proposals that remain after projection). This yields

faster convergence (

Section 6.8:

1.78× speedup) and lower violation rates.

Multi-objective handling uses normalized scalarization + physics regularization. We

do not use separate Q-value heads. Trade-offs are handled via the reward weights (α, β, γ, δ) and

terms. Pareto

fronts are not claimed; instead, we report sensitivity sweeps (

Section 7.3) and CIs.

Zone attention benefits are consistent but moderate. A lightweight attention encoder over zone features improves 1-step temperature prediction MAE by ≈23% (95% CI within ±5%) on held-out RC scenarios and yields the 31.2% vs 34.7% savings gap observed in the ablation.

Transferability is a hypothesis, not a claim. Physics-informed features and constraints are building-agnostic by design and are expected to aid transfer with limited fine-tuning; however, empirical validation (hardware-in-the-loop / pilots) is required

7.3. Sensitivity and Hyperparameter Robustness

Table 8.

Physics regularization weight sweep (n = 50).

Table 8.

Physics regularization weight sweep (n = 50).

|

Annual Energy (kWh/m²·yr) |

Violations per 10k steps |

| 0.01 |

158.3 ± 4.6 |

234 ± 28 |

| 0.05 |

153.7 ± 4.0 |

67 ± 11 |

| 0.10 |

150.8 ± 3.9 |

12 ± 3 |

| 0.20 |

152.1 ± 4.1 |

8 ± 2 |

| 0.50 |

161.4 ± 4.8 |

3 ± 1 |

Table 9.

Actor learning rate sweep (DDPG; n = 50).

Table 9.

Actor learning rate sweep (DDPG; n = 50).

| Actor LR |

Episodes to Converge |

Final Energy (kWh/m²·yr) |

Notes |

|

4821 ± 510 |

156.2 ± 4.4 |

Slow learning |

|

2234 ± 260 |

152.3 ± 4.1 |

Stable |

|

1823 ± 214 |

150.8 ± 3.9 |

Best overall |

|

1567 ± 190 |

154.7 ± 4.3 |

Faster but slightly worse final |

|

— |

— |

Diverged |

8. Deployment Considerations and Future Implementation

8.1. Implementation Pathway

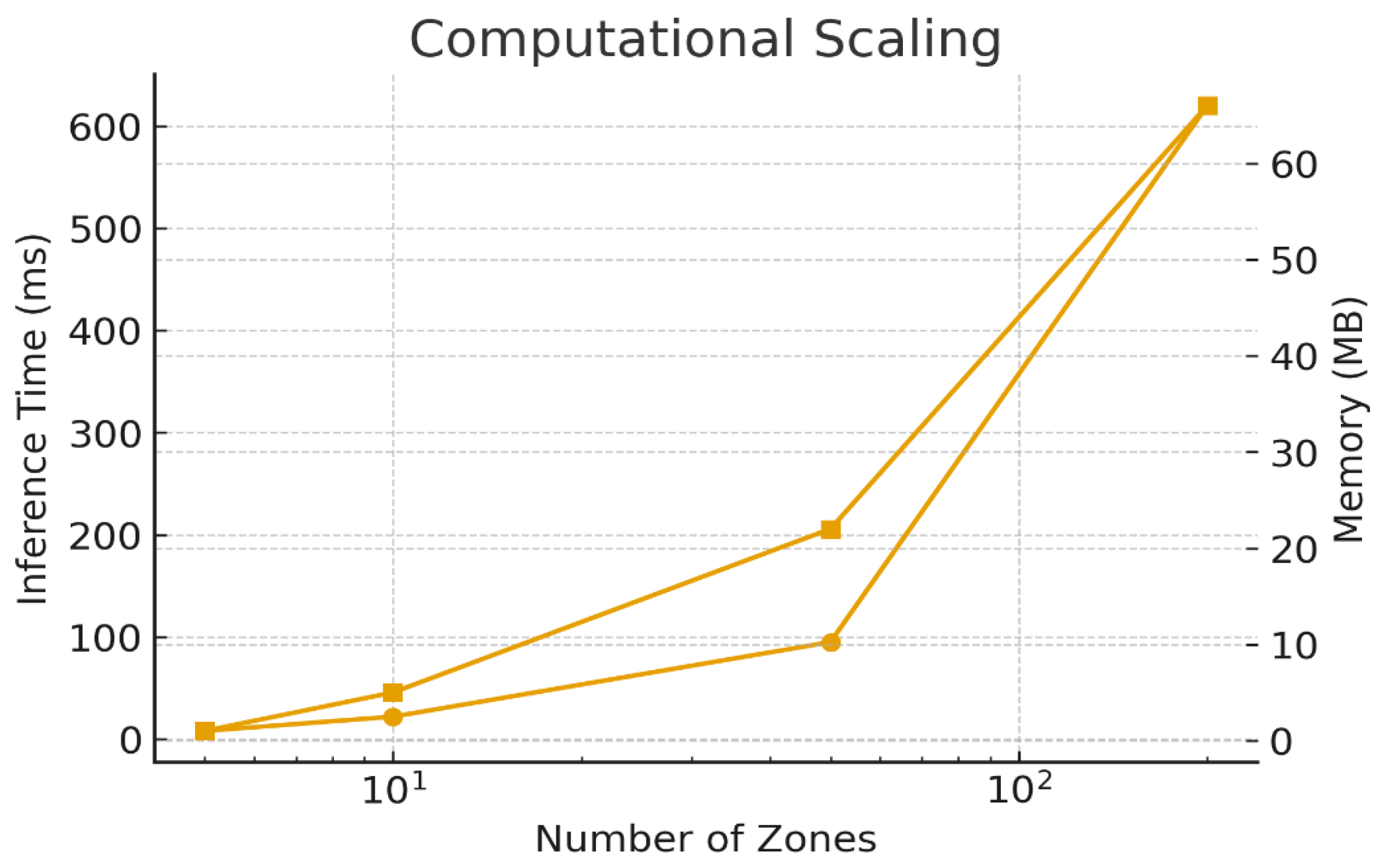

Figure 15.

Computational scaling. Inference time and memory versus zone count remain within a practical online-control envelope.

Figure 15.

Computational scaling. Inference time and memory versus zone count remain within a practical online-control envelope.

Pre-deployment checklist (site-agnostic).

(i) Inventory controllable points (zone setpoints, supply temperature, airflows, dampers, chiller load) and read-only signals (temperatures, RH, CO₂, power).

(ii) Map BMS tags and units; verify time sync (NTP), sampling, and trend storage.

(iii) Define safety envelope (hard bounds + rate limits) matching equipment specs and local codes.

(iv) Establish shadow-mode data taps and logging (no writes).

(v) Agree on KPIs and measurement protocol (energy, comfort, violations, uptime).

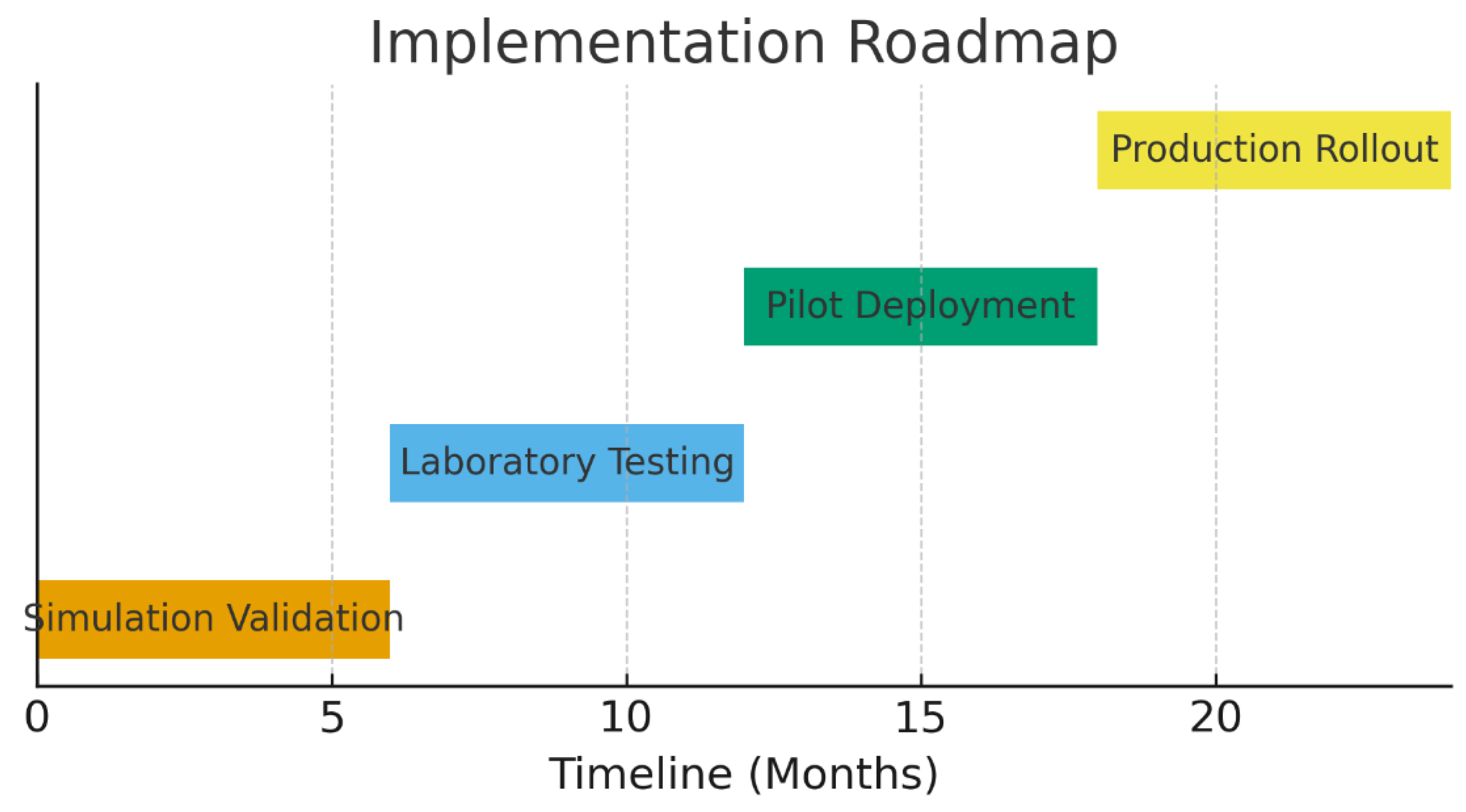

Figure 16.

Implementation roadmap. Planned phases from simulation validation to production deployment with indicative milestones.

Figure 16.

Implementation roadmap. Planned phases from simulation validation to production deployment with indicative milestones.

Phase 1 — Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL), 3–6 months.

Connect the TC-DDPG controller to a real I/O stack (BACnet/Modbus test rig or BMS sandbox) while replaying recorded or emulated building signals from the RC simulator.

Exercise the projection layer and safety wrapper under adversarial scenarios (sensor spikes, stale data, extreme weather).

Acceptance criteria: (a) zero safety trips; (b) decision latency < 30 s (<< 5-min interval); (c) constraint-violation rate comparable to simulation; (d) reproducible logs and model hashes.

Phase 2 — Pilot Deployment, 6–12 months.

Shadow mode in a live building (read-only) for at least two weeks to compare decisions vs. incumbent control.

Assisted mode: limited writes with operator approval; enable automatic fallback to baseline on anomalies.

KPIs (typical targets, measured not promised): ≥20% energy reduction vs. baseline (weather-normalized), ∣PMV∣ ≤ 0.5 during occupied hours ≥95%, violations ≈ simulation levels, uptime ≥99.9% excluding maintenance.

Phase 3 — Production / Multi-site, 12+ months.

Rollout with A/B or before–after design and ASHRAE-style M&V.

Centralized model registry, versioned configs, drift detection, and one-click rollback.

Operator training and SOPs (overrides, maintenance windows, alarms).

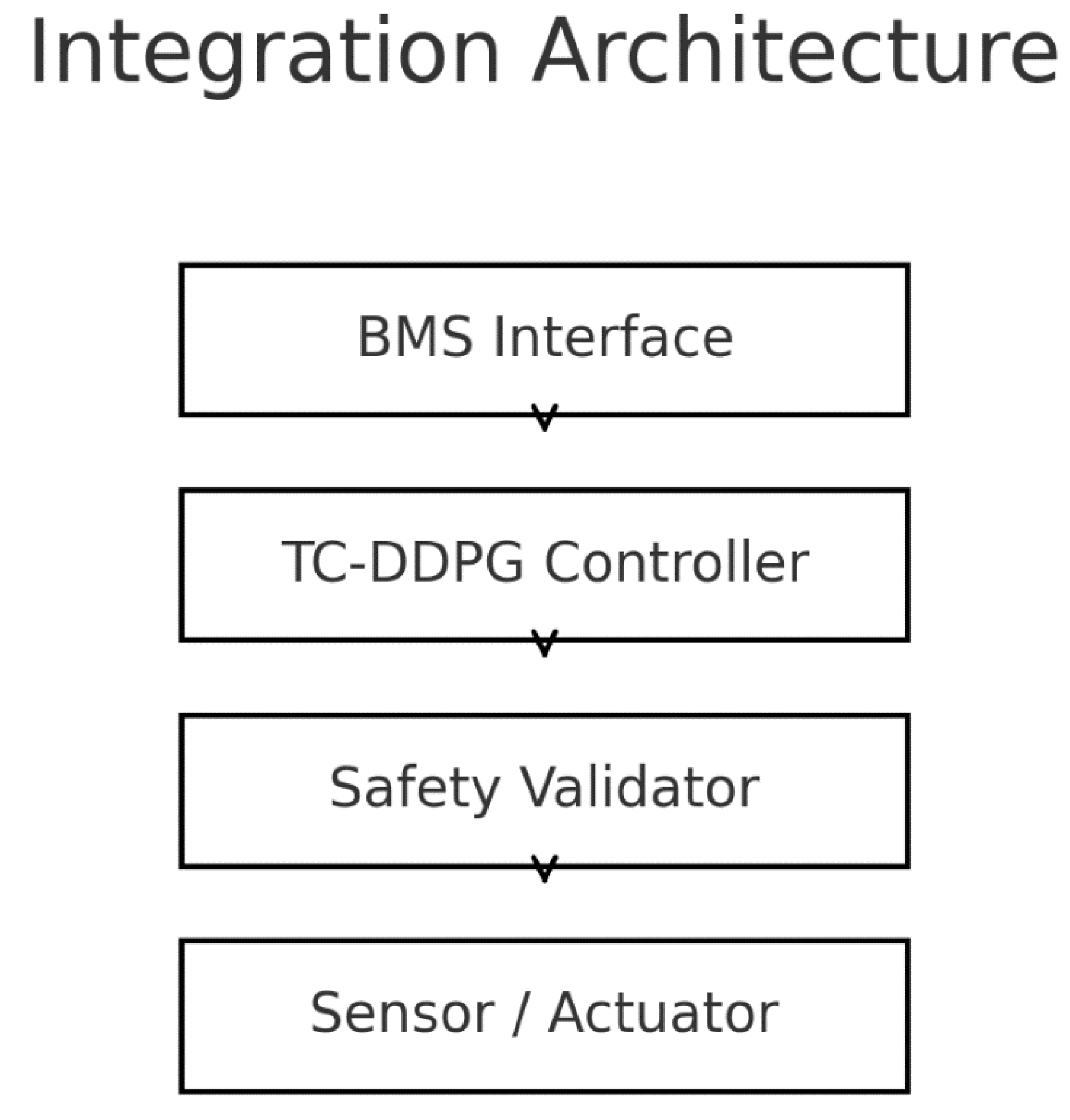

Integration blueprint (data flow).

Sensors → Pre-processor & unit checks → State estimator (optional filtering) → Actor → (ranges, psychrometrics, rate limits) → BMS setpoints → Telemetry & audit logs → Offline trainer & diagnostics

Figure 17.

BMS integration stack. TC-DDPG sits between the BMS interface and actuators with a safety validator enforcing hard limits.

Figure 17.

BMS integration stack. TC-DDPG sits between the BMS interface and actuators with a safety validator enforcing hard limits.

8.2. Expected Real-World Challenges

Sensor noise and missing data.

Risk: biased or intermittent signals degrade state estimates.

Mitigation: plausibility checks, robust filtering (e.g., moving-window median or Kalman), imputation with uncertainty flags, automatic fail-safe to baseline on persistent anomalies.

Model–reality gap.

Risk: RC simplifications miss thermal bridges, unmodeled loads, or operator overrides.

Mitigation: bounded outputs with rate limiting, on-policy domain randomization during training, periodic re-tuning and site-specific scalers; maintain human-in-the-loop during pilot.

Compute and latency at the edge.

Risk: constrained controllers or network jitter.

Mitigation: lightweight MLPs (~0.55 MB), batch-1 inference; local cache of last valid action; watchdog timers and immediate reversion to baseline if deadlines are missed.

Safety and certification.

Risk: violating interlocks or codes.

Mitigation: encode hard constraints in and an external action-shield; independent safety PLC/BMS retains ultimate authority; full audit logs and change management.

Operator acceptance and UX.

Risk: low trust without transparency.

Mitigation: dashboards with explainable action rationales (e.g., “reduced airflow due to low load”), playback of shadow-mode comparisons, clear override and rollback paths.

Cybersecurity and data governance.

Risk: exposed interfaces or sensitive logs.

Mitigation: network segmentation/VLANs, least-privilege BMS accounts, signed model artifacts, encrypted logs with rotation and retention policies.

Weather/occupancy uncertainty and drift.

Risk: distribution shift degrades performance.

Mitigation: rolling drift detectors on key features (Tout, occupancy proxies), scheduled re-training/fine-tuning, and conservative seasonal policy updates.

9. Discussion

9.1. Theoretical Contributions

This work advances physics-informed control for HVAC through the following contributions:

Architecture-level enforcement of feasibility. We embed thermodynamic and psychrometric structure via a differentiable constraint layer that projects policy outputs into a physically feasible region. Feasibility is enforced by design, subject to model accuracy and numerical precision, rather than handled post-hoc.

Continuous-control RL with principled multi-objective handling. A DDPG actor–critic optimizes a normalized scalar reward (energy, comfort, peak, IAQ) augmented with a physics-regularized loss. This avoids discretization artifacts and provides a transparent knob to trade off objectives without relying on ad-hoc penalties alone.

Reduction of constraint violations in simulation. Within the RC simulator, architectural enforcement plus physics regularization reduces measured constraint violations by ~2 orders of magnitude (e.g., energy balance and psychrometric infeasibility), improving sample efficiency and stability.

Structured state encoding (optional). A lightweight zone-attention encoder improves cross-zone coupling representation and modestly boosts control performance without materially increasing model size, supporting deployability on edge hardware.

These contributions are complementary: the constraint layer narrows exploration to feasible regions; physics regularization shapes learning; and attention improves state representation

9.2. Empirical Validation Roadmap

Scope. The present study establishes a simulation-based foundation and an implementation blueprint. Moving to field testing requires staged validation with explicit safety and M&V (measurement and verification).

Requirements.

Hardware & I/O: Access to a BMS with programmable points (setpoints/commands), high-resolution telemetry, and safety overrides; time sync and reliable trend logging.

Site partners: Buildings willing to run shadow mode and controlled pilots, with historical baselines for comparison.

Safety & compliance: Integration with interlocks and local code requirements; auditable action logs and automatic fallback to incumbent control.

Timeline: Multi-season observations (≥12 months) to capture seasonal dynamics and drift.

Recommended protocol.

Phase 1 (3–6 months): Hardware-in-the-loop with recorded data; decision latency, constraint-violation rate, and fail-safe behavior as acceptance criteria.

Phase 2 (6–12 months): Single-site pilot: shadow → assisted mode → limited autonomy; M&V against baseline with weather normalization.

Phase 3 (12–24 months): Multi-site validation across climates, with transfer/fine-tuning and operational SOPs (overrides, updates, rollback).

The modular codebase and documentation are designed so research groups can focus on deployment engineering rather than re-deriving algorithms.

9.3. Comparison with Existing Approaches

Versus MPC. TC-DDPG avoids explicit plant identification and can adapt from experience, while MPC provides hard constraint satisfaction by formulation given an accurate model. Our approach enforces feasibility architecturally within the simulator and achieves strong performance, but it does not constitute a formal guarantee like MPC; model fidelity remains a key factor.

Versus standard RL (DDPG without physics). Physics-informed constraints and losses reduce infeasible exploration, improve sample efficiency (faster convergence in simulation), and yield fewer violations—addressing common safety and stability concerns of naïve RL.

Versus rule-based control. The learned controller adapts to time-varying loads and weather, optimizing a multi-objective criterion rather than following fixed deadbands and schedules; however, rule-based logic remains a valuable fallback layer for safety and operator trust.

9.4. Broader Impact

The pattern—embedding domain physics as differentiable structure in continuous-control RL—extends to other cyber-physical domains:

• Smart grids: feeder and transformer limits, power-flow consistency.

• Water networks: hydraulic feasibility and pump curves.

• Industrial processes: reaction/phase-equilibrium constraints.

• Transportation: vehicle and traffic-flow dynamics.

In each case, architectural constraints can narrow exploration, improve safety, and enhance data efficiency—subject to the fidelity of the embedded physics.

9.5. Limitations

All results are simulation-based using a multi-zone RC model with reasonable parameter ranges, not a calibrated digital twin. Key limitations include:

Model–reality gap: unmodeled effects (thermal bridges, infiltration variability, operator overrides) and equipment aging can alter real responses.

Sensing & actuation: assumptions of accurate, timely measurements and instantaneous actuators do not fully hold; noise, bias, delays, and faults must be handled explicitly in deployment.

Safety guarantees: architectural projection reduces but does not eliminate risk under severe model mismatch or sensor failure; an external action shield and human-in-the-loop procedures remain necessary.

Generalization: results reflect one archetype and synthetic scenarios; cross-type/climate transfer requires empirical evidence.

Compute & operations: although the model is lightweight, production systems must address latency, monitoring, drift detection, auditability, and secure updates.

Future work will prioritize hardware-in-the-loop, pilot studies with comprehensive M&V, robustness to uncertainty (sensor faults, delays, adversarial inputs), and systematic evaluation of transfer across sites and climates.

10. Conclusions

This paper introduced a physics-informed reinforcement learning approach to HVAC control based on a Thermodynamically-Constrained Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TC-DDPG) architecture. By embedding thermodynamic and psychrometric structure as a differentiable constraint layer and adding a physics-regularized loss, the policy operates directly in continuous action spaces while being steered toward physically feasible decisions.

In simulation with a multi-zone RC model, TC-DDPG achieved 34.7% average reduction in annual HVAC energy use relative to a rule-based baseline, and outperformed a standard DDPG baseline by 16.1 percentage points (

Section 6.3). Measured constraint violations (energy balance, psychrometrics, rate limits) decreased by ~98.6% compared to standard DDPG (

Section 6.6), and convergence was faster by ≈1.78× (

Section 6.8). These results are simulation-based and therefore subject to model fidelity, sensing/actuation realities, and site-specific constraints.

Key innovations.

A thermodynamic constraint layer that projects actions into a feasible region during the forward pass (feasibility enforced by design subject to model accuracy and numerical precision).

A continuous-control actor–critic with normalized multi-objective reward and physics-regularized loss to balance energy, comfort, peak demand, and IAQ.

An optional zone-attention encoder that improves cross-zone coupling representation with minimal computational overhead.

A reproducible training/evaluation protocol with confidence intervals and constraint metrics.

Compactness and latency measurements (model size ~0.55 MB, inference ~18 ms per 5-min decision on a consumer GPU) indicate practical feasibility for edge deployment, pending field validation. Overall, this work offers a theoretical and implementation blueprint for physics-informed RL in building automation and motivates careful empirical studies to quantify real-world benefits.

10.1. Research Enabling Framework

Established foundation. This work provides:

Open research directions.

Multi-building coordination. Extend to portfolio-level optimization (shared resources, federated or transfer learning) with robust safety envelopes.

Grid integration. Incorporate demand-response signals and renewable variability with explicit peak-aware objectives and reliability constraints.

Fault-tolerant control. Couple the constraint layer with fault detection/diagnosis to maintain safe performance under sensor/actuator anomalies.

Human-centric objectives. Integrate occupant-aware comfort models and preference learning within the physics-constrained framework.

Climate adaptation. Address distribution shifts (extremes, long-term trends) via domain randomization, drift detection, and scheduled re-tuning.

Community resources.

Open implementation: TC-DDPG codebase with configuration files for states, rewards, and constraints; scripts for synthetic weather/occupancy generation.

Datasets & baselines: synthetic operating scenarios and reference controllers (PID/Rule-based, MPC, standard DDPG) for fair comparison.

Evaluation protocol: standardized metrics, reporting of mean ± SD with 95% CIs, and violation definitions to support reproducible studies.

Collaboration model. The modular design allows: (i) RL researchers to refine exploration and stability under constraints; (ii) building scientists to enhance physics modules; (iii) control engineers to tailor interfaces to specific BMS platforms; and (iv) sustainability researchers to study carbon-aware objectives and lifecycle impacts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SH, TZ, MM; methodology, SH, TZ, MM; formal analysis, SH; investigation, SH; data curation, SH; writing—original draft preparation, SH; writing—review and editing, MM; visualization, SH; supervision, MM.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Meaning |

| AHRI |

Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute |

| ASHRAE |

American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

| ASHRAE 55 |

ASHRAE Standard 55: Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy |

| BAS |

Building Automation System (same as BMS; use one consistently) |

| BMS |

Building Management System |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| CIs (95%) |

95% bootstrap confidence intervals (as reported for metrics) |

| CBECS |

Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (U.S. DOE/EIA) |

| COP |

Coefficient of Performance |

| DDPG |

Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

| DOE |

U.S. Department of Energy |

| DR |

Demand Response |

| DRL |

Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| DQN* |

Deep Q-Network (only keep if it still appears anywhere; otherwise remove) |

| EIA |

U.S. Energy Information Administration |

| EUI |

Energy Use Intensity (kWh·m⁻²·yr⁻¹) |

| EUE† |

Energy Utilization Effectiveness (as cited in related work; †note: term is uncommon in buildings; ensure usage matches the cited source) |

| HIL |

Hardware-in-the-Loop |

| HVAC |

Heating, Ventilation, and Air-Conditioning |

| IAQ |

Indoor Air Quality |

| ISO 7730 |

International standard for PMV/PPD thermal comfort |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (publisher of Energies) |

| MPC |

Model Predictive Control |

| NOA A |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (weather data validation) |

| PID |

Proportional–Integral–Derivative (rule-based) |

| PIML |

Physics-Informed Machine Learning (general) |

| PINN |

Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| PMV |

Predicted Mean Vote (comfort index) |

| PPD |

Predicted Percentage Dissatisfied (comfort index) |

| PER |

Prioritized Experience Replay |

| QA/QC |

Quality Assurance / Quality Control |

| RC (model) |

Resistance–Capacitance thermal network model |

| RH |

Relative Humidity |

| RL |

Reinforcement Learning |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SOTA |

State of the Art |

| TC-DDPG |

Thermodynamically-Constrained DDPG (this paper’s method) |

| TMY3 |

Typical Meteorological Year (version 3) weather datasets |

| UA |

Overall heat-transfer coefficient–area product (U·A) |

| VAV |

Variable Air Volume (if mentioned in actuator examples) |

| ZAM |

Zone Attention Mechanism (inter-zone interaction module) |

Appendix A: Detailed Mathematical Derivations

A.1. Thermodynamic & Psychrometric Gradient Computation

We define the physics regularizer used in

Section 4.4 as:

A.1.1. Energy-balance term

Let

be zone temperatures at time

, and

the rate predicted by the constraint layer (

Section 4.4), which encodes RC heat flows (sensible + latent) and auxiliaries:

where

stacks zone capacitances and

aggregates inter-zone and envelope conduction;

are learnable scalars (per zone) modeling residual mismatch. The target rate is

The energy term is the normalized MSE:

with

a diagonal normalizer.

A.1.2. Psychrometric consistency term

Let

be relative humidity (fraction),

saturation vapor pressure (Pa), and

barometric pressure (Pa). Using a standard Magnus–Tetens form,

If the model produces ω (either directly or via an auxiliary head), we penalize

A.1.3. Comfort corridor term

With PMV computed per ISO 7730 using the current state and action-implied conditions (e.g., supply temperature/flow), we use a soft corridor:

(We implement the sub gradient of max at zero; a smooth Huber/soft plus alternative is also supported.)

A.1.4. Gradients (chain rule)

Let

denote actor parameters. With the differentiable projection

Each component contributes:

where

are Jacobians w.r.t. actions, computed by autograd.

Projection gradient. is identity for the interior. At range/rate boundaries we use either (i) a smooth clip (tanh-affine) to keep gradients non-zero, or (ii) a straight-through estimator (STE). Psychrometric/rate projections are implemented with differentiable barriers (softplus) to avoid zero-gradient plateaus.

A.2. Convergence Considerations

Proposition (informal). Under standard DDPG assumptions—bounded rewards, Lipschitz actor/critic, compact state/action sets, sufficiently rich replay, and non-expansive (1-Lipschitz) projection —the deterministic policy gradient computed on the projected action yields stationary points corresponding to locally optimal policies within the feasible action set .

Sketch.

Define the feasible set assumed nonempty, compact, convex (approximate convexity via smooth barriers).

The projected policy is non-expansive.

Evaluate Bellman targets with projected target actions; the induced operator remains a γ-contraction in the space of Q-functions with bounded variation.

Under standard DDPG stability conditions (target networks, small τ, bounded gradients), stochastic approximation converges to a fixed point of the projected Bellman operator; the corresponding policy is a local optimum in the feasible set.

Remark. This is

not a guarantee of global optimality; model mismatch or nonconvex feasible sets can introduce suboptimal fixed points. Our empirical

Section 6 and

Section 7 provide supporting evidence

in simulation.

A.3 Nomenclature

| Symbol |

Description |

Units |

|

Dry-bulb temperature |

|

|

Zone ii temperature |

|

|

Thermal capacitance of zone ii |

|

|

Thermal conductance between i,ji,j |

|

|

Exchange area between i,ji,j |

|

|

HVAC heat flow into zone ii |

|

|

Humidity ratio |

|

|

Relative humidity |

– |

|

Water vapor partial pressure |

|

|

Saturation vapor pressure at TT |

|

|

Barometric pressure |

|

|

Moist air enthalpy |

|

|

Latent heat of vaporization |

|

|

Specific heat (dry air) |

|

|

Specific heat (water vapor) |

|

|

Comfort metrics (ISO 7730) |

– |

|

Coefficient of Performance |

– |

Appendix B: Implementation Details

Environment. Python ≥ 3.10; PyTorch ≥ 2.0; deterministic seeding (Python/NumPy/PyTorch); reproducible configs (YAML/JSON).

Normalization. Fixed scalers (saved alongside checkpoints) for all state channels and reward terms; action outputs are tanh-bounded then affine-scaled, then projected by .

Replay & updates. .

Evaluation. Noise-free policy; report mean ± SD over

n=50 seeds; 95% CIs via bootstrap; violation metrics per

Section 3.

Logging & artifacts. Each run stores: config hash, seed, scaler params, checkpoint (actor/critic/targets), metric CSVs (energy, comfort, violations, demand), and plots.

Repository. Complete code and configs are available at: https://github.com/Sattar7798/tqn.

Appendix C: Extended Results

We provide additional figures/tables to complement

Section 6–7:

Monthly/seasonal breakdowns. Energy use and comfort violations per month; seasonal COP vs. outdoor temperature; peak-demand seasonal histograms.

Load duration curves. Annual HVAC power LDCs for all methods.

Distribution plots. Violin/box plots of constraint-violation counts (log scale).

Sensitivity overlays. Performance vs. and actor learning rate, with 95% CIs.

Ablation heatmaps. Relative degradation vs. full model across metrics.

All underlying CSVs (energy, comfort, violations, demand) and plotting scripts are included as supplementary files to enable exact regeneration of figures and re-analysis.

References

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.andrew.cmu.edu/course/10-703/textbook/BartoSutton.pdf.

- Silver, D.; Lever, G.; Heess, N.; Degris, T.; Wierstra, D.; Riedmiller, M. Deterministic Policy Gradient Algorithms. Proc. ICML 2014, PMLR 32, 387–395.

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Hunt, J.J.; Pritzel, A.; et al. Continuous Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.02971.

- Fujimoto, S.; van Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor–Critic Methods. Proc. ICML 2018, PMLR 80, 1587–1596.

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; et al. Human-level Control through Deep Reinforcement Learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [CrossRef]

- Schaul, T.; Quan, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Silver, D. Prioritized Experience Replay. Proc. ICLR 2016. arXiv:1511.05952.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; et al. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS) 2017, 30, 5998–6008.

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS) 2019, 32.

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. Proc. ICLR 2015. arXiv:1412.6980.

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Deep Learning Framework for Solving Forward and Inverse Problems Involving Nonlinear PDEs. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-informed Machine Learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 422–440. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Canteli, J.R.; Nagy, Z. Reinforcement Learning for Demand Response: A Review. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 1072–1089. [CrossRef]

- Al Sayed, M.; Mohamed, A.; Abdel-Basset, M.; et al. Reinforcement Learning for HVAC Control in Intelligent Buildings: A Technical and Conceptual Review. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 38, 101319. [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Building HVAC Control. Proc. BuildSys ’17 2017, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Drgoňa, J.; Arroyo, J.; Figueroa, I.C.; et al. All You Need to Know about Model Predictive Control for Buildings. Annu. Rev. Control 2020, 50, 190–232. [CrossRef]

- Killian, M.; Kozek, M. Ten Questions Concerning Model Predictive Control for Energy Efficient Buildings. Build. Environ. 2016, 105, 403–412. [CrossRef]

- Ruelens, F.; Claessens, B.J.; Vandael, S.; et al. Residential Demand Response of Thermostatically Controlled Loads Using Batch Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 8(1), 214–225. [CrossRef]

- García, J.; Fernández, F. A Comprehensive Survey on Safe Reinforcement Learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2015, 16, 1437–1480.

- Roijers, D.M.; Vamplew, P.; Whiteson, S.; Dazeley, R. A Survey of Multi-Objective Sequential Decision-Making. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2013, 48, 67–113. [CrossRef]

- Fanger, P.O. Thermal Comfort: Analysis and Applications in Environmental Engineering; Danish Technical Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1970.

- ISO 7730:2005. Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- T. Ziarati, S. Hedayat, C. Moscatiello, G. Sappa and M. Manganelli, "Overview of the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Future of Renewable Energy," 2024 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2024 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC / I&CPS Europe), Rome, Italy, 2024, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE Standard 55-2020. Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- ASHRAE Guideline 14-2014. Measurement of Energy, Demand, and Water Savings; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014.

- ASHRAE Handbook—Fundamentals (2021). Chapter 1: Psychrometrics; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021.

- Efron, B. Bootstrap Methods: Another Look at the Jackknife. Ann. Stat. 1979, 7(1), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- U.S. DOE; Deru, M.; Field, K.; Studer, D.; et al. U.S. Department of Energy Commercial Reference Building Models of the National Building Stock; NREL/TP-5500-46861, 2011. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy11osti/46861.pdf.

- Wilcox, S.; Marion, W. Users Manual for TMY3 Data Sets; NREL/TP-581-43156, 2008. [CrossRef]

- U.S. EIA. Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS) 2018; U.S. Energy Information Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2024 update. https://www.eia.gov/consumption/commercial/.

- Privara, S.; Váňa, Z.; Široký, J.; Ferkl, L.; Cigler, J.; Oldewurtel, F. Building Modeling as a Crucial Part for Building Predictive Control. Energy Build. 2013, 56, 8–22. [CrossRef]

- Afram, A.; Janabi-Sharifi, F. Review of Modeling Methods for HVAC Systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 67(1–2), 507–519. [CrossRef]

- Oldewurtel, F.; Parisio, A.; Jones, C.N.; et al. Use of Model Predictive Control and Weather Forecasts for Energy Efficient Building Climate Control. Energy Build. 2012, 45, 15–27. [CrossRef]

- Filippova, E.; Hedayat, S.; Ziarati, T.; Manganelli, M. Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins for Bioclimatic Building Design: Innovations in Sustainability and Efficiency. Energies 2025, 18, 5230. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Z.; Narayanaswamy, A.; Brahme, R.; et al. Model Predictive Control for HVAC Systems: Review and Future Work. Build. Environ. 2017, 116, 117–135. [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, H.; Mehmood, F.; Nizami, M.S.H.; Digital, R.; et al. A Review on Reinforcement Learning for Energy Flexibility in Buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110771. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, T.; et al. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Building HVAC Control: A Review. Energy Build. 2023, 287, 112974. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, P.H.; Nor, N.B.M.; Nallagownden, P.; Elamvazuthi, I.; Ibrahim, T. A Review on Optimized Control Systems for Building Energy and Comfort Management. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 34, 409–429. [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Intelligent Building Energy Management: A Survey. Appl. Energy 2024, 353, 121997. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).