Submitted:

01 November 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

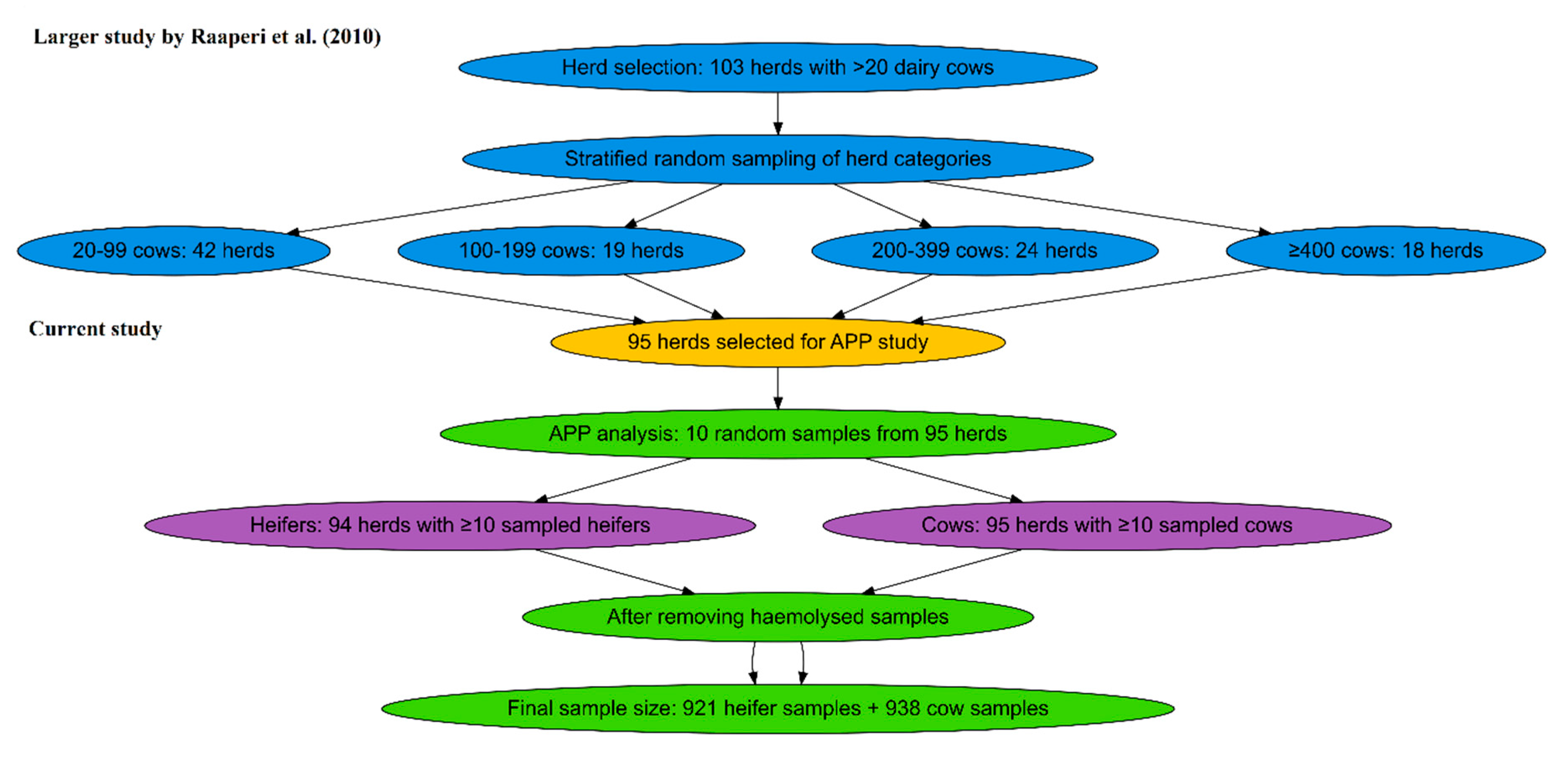

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sampling of Animals and Sample Analysis

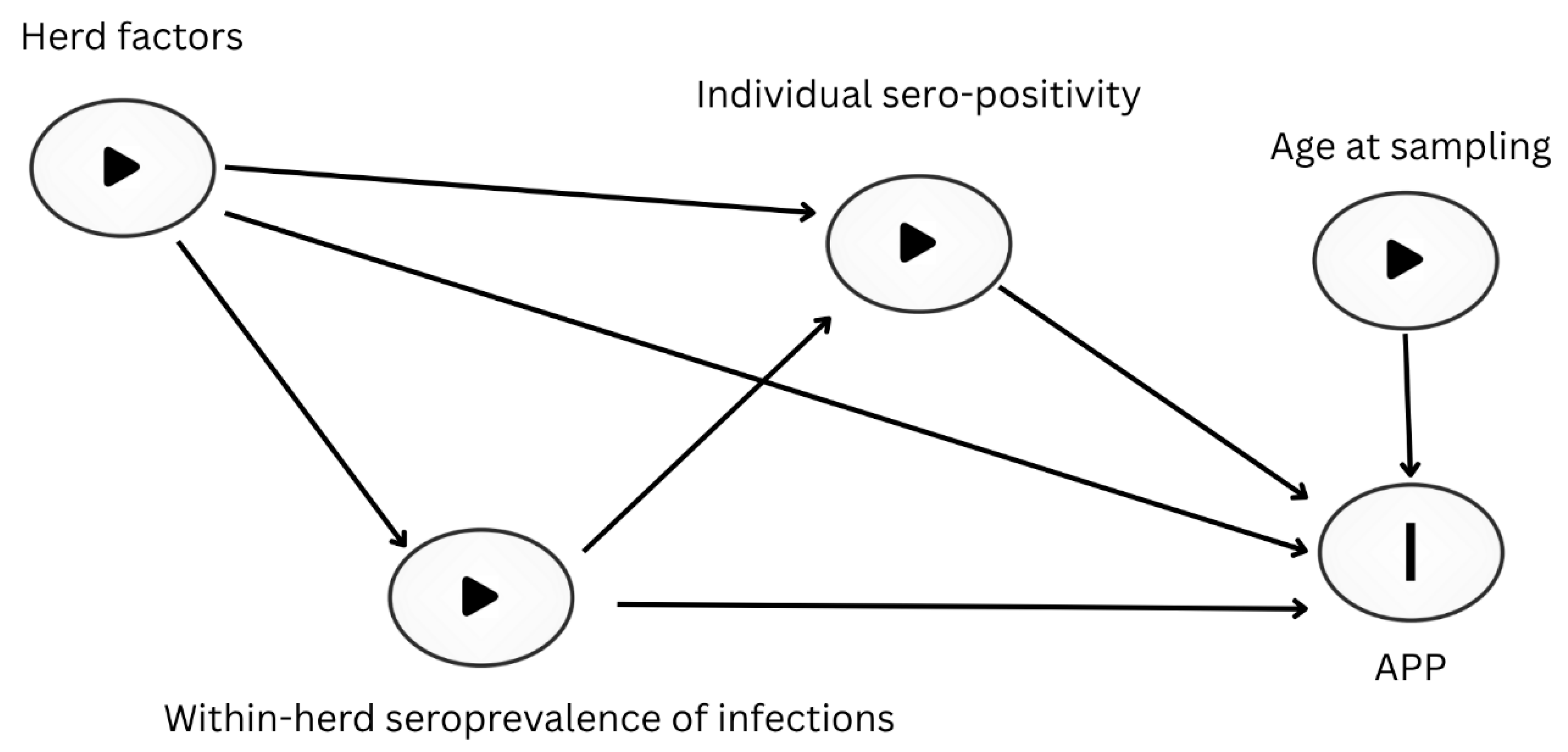

2.3. Statistical Analysis

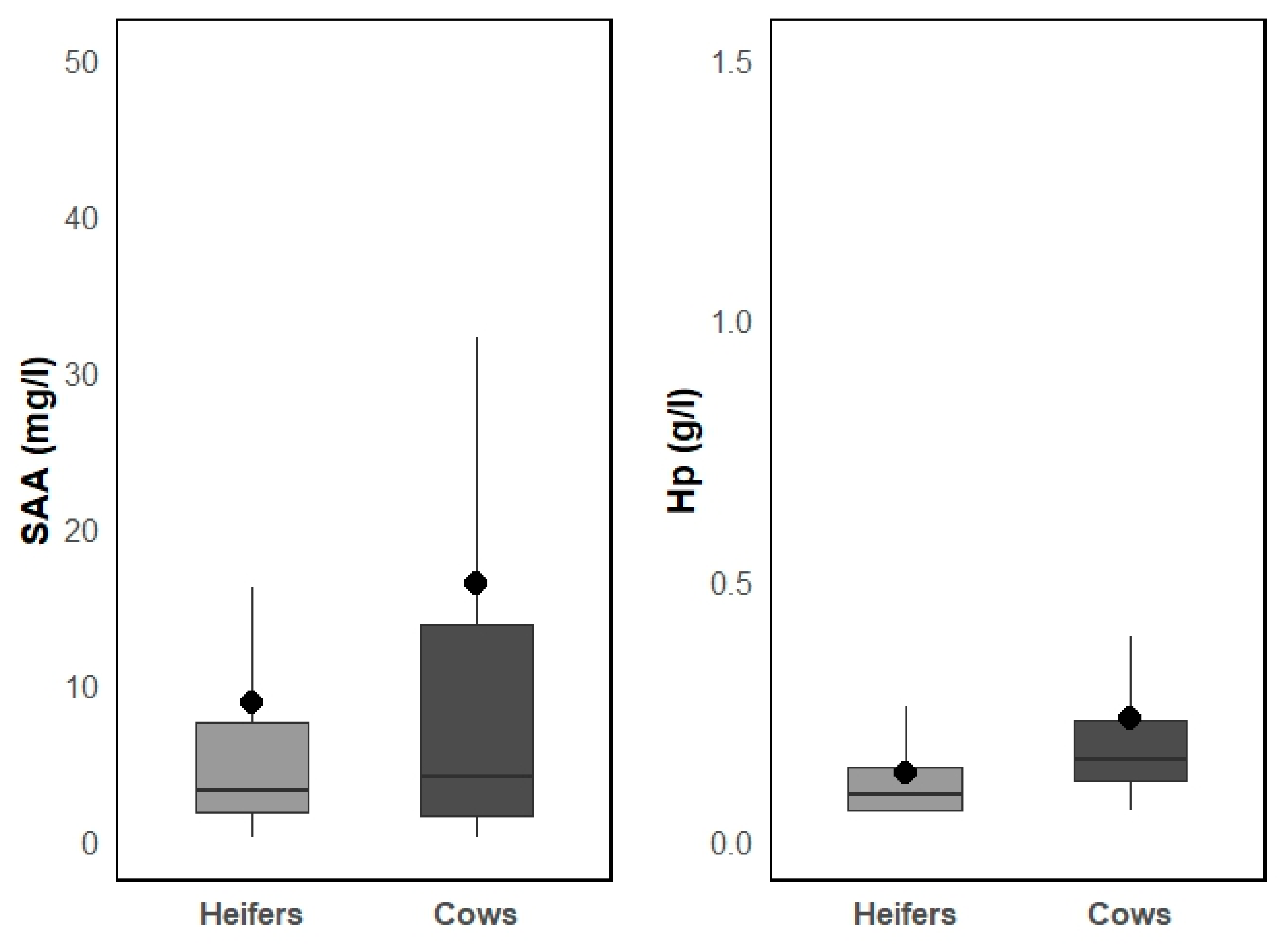

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Seroprevalence of Infections Associated with APP in Cows and Heifers

4.2. Herd-Level Factors Associated with APP in Cows and Heifers

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicola, I.; Cerutti, F.; Grego, E.; Bertone, I.; Gianella, P.; D’Angelo, A.; Peletto, S.; Bellino, C. Characterization of the upper and lower respiratory tract microbiota in Piedmontese calves. Microbiome 2017, 5, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, M.; Ferreras, M.D.C.; Giráldez, F.J.; Benavides, J.; Pérez, V. Production significance of bovine respiratory disease lesions in slaughtered beef cattle. Animals 2020, 10, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas-Gómez, I.; McGee, M.; Sánchez, J.M.; O’Riordan, E.; Byrne, N.; McDaneld, T.; Earley, B. Association between clinical respiratory signs, lung lesions detected by thoracic ultrasonography and growth performance in pre-weaned dairy calves. Ir. Vet. J. 2021, 74, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callan, R.J.; Garry, F.B. Biosecurity and bovine respiratory disease. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2002, 18, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisset, G.P.; White, B.J.; Larson, R.L. Structured literature review of responses of cattle to viral and bacterial pathogens causing bovine respiratory disease complex. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2015, 29, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heegaard, P.M.; Godson, T.L.; Toussaint, M.J.; Tjørnehøj, K.; Larsen, L.E.; Viuff, B.; Rønsholt, L. The acute phase response of haptoglobin and serum amyloid A (SAA) in cattle undergoing experimental infection with bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2000, 77, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orro, T.; Pohjanvirta, T.; Rikula, U.; Huovilainen, A.; Alasuutari, S.; Sihvonen, L.; Pelkonen, S.; Soveri, T. Acute phase protein changes in calves during an outbreak of respiratory disease caused by bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 34, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunsell, F.P.; Donovan, G.A. Mycoplasma bovis infections in young calves. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2009, 25, 139–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterbock, W.M. The impact of BRD: the current dairy experience. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2014, 15, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikunen, S.; Härtel, H.; Orro, T.; Neuvonen, E.; Tanskanen, R.; Kivelä, S.L.; Sankari, S.; Aho, P.; Pyörälä, S.; Saloniemi, H.; Soveri, T. Association of bovine respiratory disease with clinical status and acute phase proteins in calves. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007, 30, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gånheim, C.; Hultén, C.; Carlsson, U.; Kindahl, H.; Niskanen, R.; Waller, K.P. The acute phase response in calves experimentally infected with bovine viral diarrhoea virus and/or Mannheimia haemolytica. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health 2003, 50, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thielen, M.A.; Mielenz, M.; Hiss, S.; Zerbe, H.; Petzl, W.; Schuberth, H.J.; Seyfert, H.M.; Sauerwein, H. Short communication: Cellular localization of haptoglobin mRNA in the experimentally infected bovine mammary gland. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 1215–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, H.H.; Nielsen, J.P.; Heegaard, P.M.H. Application of acute phase protein measurements in veterinary clinical chemistry. Vet. Res. 2004, 35, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horadagoda, N.U.; Knox, K.M.G.; Gibbs, H.A.; Reid, S.W.J.; Horadagoda, A.; Edwards, S.E.R.; Eckersall, P.D. Acute phase proteins in cattle: discrimination between acute and chronic inflammation. Vet. Rec. 1999, 144, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanghe, J.R.; Langlois, M.R.; De Bacquer, D.; Mak, R.; Capel, P.; Van Renterghem, L.; De Backer, G. Discriminative value of serum amyloid A and other acute-phase proteins for coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis 2002, 160, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saco, Y.; Bassols, A. Acute phase proteins in cattle and swine: A review. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2023, 52 Suppl 1, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomorska-Mól, M.; Markowska-Daniel, I.; Kwit, K.; Stępniewska, K.; Pejsak, Z. C-reactive protein, haptoglobin, serum amyloid A and pig major acute phase protein response in pigs simultaneously infected with H1N1 swine influenza virus and Pasteurella multocida. BMC Vet. Res. 2013, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mõtus, K.; Rilanto, T.; Viidu, D.A.; Orro, T.; Viltrop, A. Seroprevalence of selected endemic infectious diseases in large-scale Estonian dairy herds and their associations with cow longevity and culling rates. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 192, 105389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaperi, K.; Nurmoja, I.; Orro, T.; Viltrop, A. Seroepidemiology of bovine herpes virus 1 (BHV1) infection among Estonian dairy herds and risk factors for the spread within herds. Prev. Vet. Med. 2010, 96, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeant, E.S.G. Epitools Epidemiological Calculators. Ausvet. Available online: http://epitools.ausvet.com.au (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Hove, H. Serological analysis of a small herd-sample to predict presence or absence of animals persistently infected with bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) in dairy herds. Res. Vet. Sci. 1992, 53, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makimura, S.; Suzuki, N. Quantitative determination of bovine serum haptoglobin and its elevation in some inflammatory diseases. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi 1982, 44, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsemgeest, S.P.M.; Kalsbeek, H.C.; Wensing, T.; Koeman, J.P.; Van Ederen, A.M.; Gruys, E. Concentrations of serum amyloid-A (SAA) and haptoglobin (HP) as parameters of inflammatory diseases in cattle. Vet. Q. 1994, 16, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Textor, J.; van der Zander, B.; Gilthorpe, M.K.; Liskiewicz, M.; Ellison, G.T.H. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: The R package dagitty. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckersall, P.D.; Bell, R. Acute phase proteins: Biomarkers of infection and inflammation in veterinary medicine. Vet. J. 2010, 185, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muylkens, B.; Thiry, J.; Kirten, P.; Schynts, F.; Thiry, E. Bovine herpesvirus 1 infection and infectious bovine rhinotracheitis. Vet. Res. 2007, 38, 181–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaperi, K.; Bougeard, S.; Aleksejev, A.; Orro, T.; Viltrop, A. Association of herd BHV-1 seroprevalence with respiratory disease in youngstock in Estonian dairy cattle. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012, 93, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento-Silva, R.E.; Nakamura-Lopez, Y.; Vaughan, G. Epidemiology, molecular epidemiology and evolution of bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Viruses 2012, 30, 3452–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klem, T.B.; Gulliksen, S.M.; Lie, K.I.; Løken, T.; Østerås, O.; Stokstad, M. Bovine respiratory syncytial virus: Infection dynamics within and between herds. Vet. Rec. 2013, 173, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägglund, S.; Svensson, C.; Emanuelson, U.; Valarcher, J.F.; Alenius, S. Dynamics of virus infections involved in the bovine respiratory disease complex in Swedish dairy herds. Vet. J. 2006, 172, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, L.J. Bovine respiratory coronavirus. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2010, 26, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, K.; Nicholas, R.A.J.; Szacawa, E.; Bednarek, D. Mycoplasma bovis infections—occurrence, diagnosis and control. Pathogens 2020, 9, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengarten, R.; Citti, C.; Glew, M.; Lischewski, A.; Droeße, M.; Much, P.; Winner, F.; Brank, M.; Spergser, J. Host-pathogen interactions in mycoplasma pathogenesis: virulence and survival strategies of minimalist prokaryotes. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2000, 290, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, J.W.; Brandt, P.; Mahoney, J.R., Jr.; Lee, J.T. Haptoglobin: a natural bacteriostat. Science 1982, 215, 691–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthington, J.D.; Eicher, S.D.; Kunkle, W.E.; Martin, F.G. Effect of transportation and commingling on the acute-phase protein response, growth, and feed intake of newly weaned beef calves. J. Anim. Sci. 2003, 81, 1120–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seppä-Lassila, L.; Orro, T.; Lassen, B.; Lasonen, R.; Autio, T.; Pelkonen, S.; Soveri, T. Intestinal pathogens, diarrhoea and acute phase proteins in naturally infected dairy calves. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 41, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.B.; Wawegama, N.K.; Denwood, M.; Markham, P.F.; Browning, G.F.; Nielsen, L.R. Mycoplasma bovis antibody dynamics in naturally exposed dairy calves according to two diagnostic tests. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penterman, P.M.; Holzhauer, M.; van Engelen, E.; Smits, D.; Velthuis, A.G.J. Dynamics of Mycoplasma bovis in Dutch dairy herds during acute clinical outbreaks. Vet. J. 2022, 283–284, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.B.; Pedersen, L.; Pedersen, L.M.; Nielsen, L.R. Experience of antibody testing against Mycoplasma bovis in adult cows in commercial Danish dairy cattle herds. Pathogens 2020, 9, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaura, R.; Dorbek-Kolin, E.; Loch, M.; Viidu, D.A.; Orro, T.; Mõtus, K. Association of clinical respiratory disease signs and lower respiratory tract bacterial pathogens with systemic inflammatory response in preweaning dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 5988–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantón, G.; Llada, I.; Margineda, C.; Urtizbiría, F.; Fanti, S.; Scioli, V.; Fiorentino, M.A.; Louge Uriarte, E.; Morrell, E.; Sticotti, E.; Tamiozzo, P. Mycoplasma bovis-pneumonia and polyarthritis in feedlot calves in Argentina: First local isolation. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2022, 54, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, S.; de Jong, E.; McCubbin, K.D.; Biesheuvel, M.M.; van der Meer, F.J.U.M.; De Buck, J.; Lhermie, G.; Hall, D.C.; Kalbfleisch, K.N.; Kastelic, J.P.; Orsel, K.; Barkema, H.W. Herd-level prevalence of bovine leukemia virus, Salmonella Dublin, and Neospora caninum in Alberta, Canada, dairy herds using ELISA on bulk tank milk samples. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 8313–8328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mayet, F.; Jones, C. Stress Can Induce Bovine Alpha-Herpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1) Reactivation from Latency. Viruses 2024, 16, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.H.; Yang, J.Y.; Upadhaya, S.D.; Lee, H.J.; Yun, C.H.; Ha, J.K. The stress of weaning influences serum concentrations of acute-phase proteins, iron-binding proteins, inflammatory cytokines, cortisol, and leukocyte subsets in Holstein calves. J. Vet. Sci. 2011, 12, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenneker, K.; Schulze, M.; Pieper, L.; Jung, M.; Schmicke, M.; Beyer, F. Comparative assessment of the stress response of cattle to common dairy management practices. Animals 2023, 13, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huzzey, J.M.; Nydam, D.V.; Grant, R.J.; Overton, T.R. Associations of prepartum plasma cortisol, haptoglobin, fecal cortisol metabolites, and nonesterified fatty acids with postpartum health status in Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 5878–5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givens, M.D. Review: Risks of disease transmission through semen in cattle. Animal 2018, 12, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Poel, W.H.; Langedijk, J.P.; Kramps, J.A.; Middel, W.G.; Brand, A.; Van Oirschot, J.T. Serological indication for persistence of bovine respiratory syncytial virus in cattle and attempts to detect the virus. Arch. Virol. 1997, 142, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riigiteataja. Animal Protection Act (Consolidated version as of Jan. 1, 2023). Riigi Teataja. Available online: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/505102023013/consolide (accessed on 5 September 2025).

| Pathogen | Animals tested | Sample size considerations | Diagnostic test for antibodies (Se1; Sp2 %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHV-13 | Cows and heifers |

Sample size for prevalence estimation: Expected prevalence of the infection was based on prior information when available. Otherwise, expected prevalence of 50% for youngstock and 75% for cows were assumed with 10% accepted error. In previously known negative herds, sample size for detection of the infection in the herd was calculated using 5% expected prevalence, and 95% confidence level (Epitools; [20]). Average sample size per herd was 50 for cows (range: 16–116) and 55 for heifers (range: 11–237) [19]. |

IDEXX IBR gB X3 (IDEXX Laboratories) (96.0; 99.0) |

| BVDV4 | Heifers | Spot testing of the herd to define the herd BVDV status regarding persistent infection: 10 animals per herd. A herd was considered suspect for containing persistently infected animals if at least six out of 10 young animals tested positive for BVDV antibodies [21]. Detection of minimum prevalence: 28% with 95% confidence [19]. | PrioCheck BVDV Ab (Prionics AG, Switzerland) (98.0; 99.0) |

|

M. bovis5, BRSV6 |

Cows and heifers |

Sample size to estimate within-herd prevalence: Minimum detectable prevalence (design prevalence): 27% in cows, 15% in heifers with 95% confidence (Epitools3). Average sample size per herd was 9.8 for cows (min-max: 8–10) and 18.6 for heifers (min-max: 10–20). |

BIO K 260 (Bio-X Diagnostics, Belgium) (49.1; 89.6), SVANOVIR BRSV-Ab (Boehringer Ingelheim Svanova) (94.6; 100.0) |

| PIV-37, BCV8, BAV9 |

Heifers |

Sample size to estimate within-herd prevalence: Detection of minimum prevalence: 15% with 95% confidence (Epitools3). Average sample size per herd was 18.6 (min-max: 11–20). |

SVANOVIR PIV3-Ab (Boehringer Ingelheim Svanova) (95.4; 98.5), SVANOVIR BCV-Ab (Boehringer Ingelheim Svanova) (84.6; 100.0), Adenovirus-Ab (IDEXX, USA) (Not available) |

| Variable | Coeff. | SE | p-value | Wald test p-value |

| Age of cows (year) | -0.242 | 0.109 | 0.027 | |

| Age of cow squared (year) | 0.023 | 0.009 | 0.011 | |

| Within-herd prevalence of BHV-1 in cows: | <0.001 | |||

| 0% (n = 365/37) | 0 | |||

| 1-50% (n = 256/26) | 0.219 | 0.160 | 0.172 | |

| >50% (n = 317/32) | 0.729 | 0.169 | <0.001 | |

| Within-herd prevalence of BRSV in cows: | 0.021 | |||

| 0% (n = 178/18) | 0 | |||

| 1-50% (n = 209/21) | 0.404 | 0.195 | 0.038 | |

| >50% (n = 551/56) | 0.504 | 0.182 | 0.006 | |

| Veterinarian is an employee of the farm: | ||||

| No (n = 741/72) | 0 | |||

| Yes (n = 197/20) | -0.542 | 0.184 | 0.003 | |

| Herd size: | 0.011 | |||

| <50 (n = 237/24) | 0 | |||

| 50-99 (n = 140/14) | 0.541 | 0.198 | 0.006 | |

| 100-199 (n = 140/14) | 0.043 | 0.203 | 0.831 | |

| 200-399 (n = 220/22) | 0.369 | 0.190 | 0.052 | |

| >399 (n = 201/21) | 0.570 | 0.217 | 0.009 | |

| Constant | 1.228 | 0.333 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Coeff. | SE | p-value | Wald test p-value |

| Age of cows (years) | -0.021 | 0.011 | 0.056 | |

| Cow M. bovis status: | ||||

| Negative (n = 664) | 0 | |||

| Positive (n = 274) | -0.105 | 0.048 | 0.030 | |

| Haemolysis in serum sample: | <0.001 | |||

| No haemolysis (n = 763) | 0 | |||

| Slight haemolysis (n = 120) | -0.436 | 0.066 | <0.001 | |

| Marked haemolysis (n = 55) | -0.898 | 0.093 | <0.001 | |

| Herd size: | 0.291 | |||

| <50 (n = 237/24) | 0 | |||

| 50-99 (n = 140/14) | -0.015 | 0.083 | 0.852 | |

| 100-199 (n = 140/14) | 0.107 | 0.082 | 0.193 | |

| 200-399 (n = 220/22) | 0.027 | 0.072 | 0.706 | |

| >399 (n = 201/21) | -0.077 | 0.074 | 0.302 | |

| Constant | 2.744 | 0.078 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Coeff. | SE | p-value | Wald test p-value |

| Age of heifers (months) | -0.082 | 0.025 | 0.001 | |

| Age of heifers squared (months) | 0.002 | 0.0006 | 0.001 | |

| Number of heifers at farm x 100 | 0.052 | 0.027 | 0.058 | |

| Haemolysis in serum sample: | <0.001 | |||

| No haemolysis (n = 661) | 0 | |||

| Slight haemolysis (n = 181) | -0.171 | 0.098 | 0.083 | |

| Marked haemolysis (n = 79) | -0.572 | 0.138 | <0.001 | |

| Within-herd prevalence of BHV-1 in heifers: | 0.007 | |||

| 0% (n = 543/56) | 0 | |||

| 1-50% (n = 269/27) | 0.386 | 0.132 | 0.004 | |

| >50% (n = 109/11) | -0.036 | 0.206 | 0.861 | |

|

Within-herd prevalence of M. bovisin heifers: |

0.003 | |||

| 0-30% (n = 119/13) | 0 | |||

| 31-50% (n = 356/36) | -0.065 | 0.182 | 0.719 | |

| >50% (n = 446/45) | -0.446 | 0.179 | 0.013 | |

| Housing system for heifers: | 0.043 | |||

| Tie stall (n = 240/24) | 0 | |||

| Free stall (n = 232/24) | 0.350 | 0.16 | 0.029 | |

| Mixed (n = 449/46) | 0.319 | 0.14 | 0.023 | |

| Constant | 1.864 | 0.287 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Coeff.1 | SE | p-value | Wald test p-value |

| Age of heifers (months) | -0.013 | 0.005 | 0.007 | |

| Number of heifers at farm x 100 | -0.069 | 0.022 | 0.001 | |

| Haemolysis of sample: | <0.001 | |||

| No haemolysis (n = 661) | 0 | |||

| Slight haemolysis (n = 181) | -0.843 | 0.082 | <0.001 | |

| Marked haemolysis (n = 79) | -1.551 | 0.116 | <0.001 | |

| Within-herd prevalence of BHV-1 in heifers: | 0.023 | |||

| 0% (n = 543/56) | 0 | |||

| 1-50% (n = 269/27) | 0.224 | 0.109 | 0.040 | |

| >50% (n = 109/11) | 0.398 | 0.169 | 0.018 | |

| Use of a breeding bull in heifers: | ||||

| No (n = 594/60) | 0 | |||

| Yes (n = 327/34) | -0.205 | 0.098 | 0.038 | |

| Constant | 4.061 | 0.119 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).