1. Introduction

Modern construction imposes increasingly stringent requirements on the quality, serviceability, and durability of reinforced concrete structures, such as piles, which are a common solution for foundation systems of various buildings and infrastructure [

4]. One of the key factors determining the service life of reinforced concrete piles in aggressive environments is their water absorption. Increased porosity and capillary permeability of the concrete matrix facilitate moisture ingress, leading to a reduction in mechanical strength, leaching of cement paste components, and accelerated corrosion of reinforcing steel.

To mitigate these negative effects, there has been growing interest in recent years in the development and application of modified concrete compositions with hydrophobic properties [

5]. The integration of modern chemical admixtures, nanomodifiers, and technological treatments (such as vacuum processing and heat curing) enables the formation of a dense, water-repellent concrete structure, reducing both capillary and hygroscopic water absorption without compromising strength performance [

6,

7,

8].

The relevance of this research lies in the need to improve the durability of reinforced concrete piles under conditions of periodic wetting, freezing, and exposure to aggressive groundwater [

4,

9,

10]. In the context of a construction market focused on resource efficiency and structural reliability, the development of effective methods for modifying concrete mixes to impart hydrophobic properties has become a priority in the field of construction materials technology.

The aim of this study is to develop and scientifically substantiate an effective composition of modified concrete with enhanced hydrophobic properties that ensures reduced water absorption and increased durability of reinforced concrete piles under various service conditions.

Reducing water absorption and permeability in concrete has traditionally been achieved by decreasing the quantity and size of pores within the cement paste. This is commonly done by lowering the water-to-cement (W/C) ratio using high-performance superplasticizers, which reduce excess mixing water and the resulting porosity during curing. Additionally, active mineral additives—such as silica fume, fly ash, and metakaolin—are employed to fill micropores and densify the cement matrix through pozzolanic reactions. The incorporation of fine fillers also contributes to increased matrix density. These strategies effectively reduce the capillary suction capacity of concrete.

However, even in an optimally dense structure, it is difficult to completely eliminate water ingress if the surface energy of the pores remains high—that is, if the material remains hydrophilic [

11,

12]. Moreover, technological treatments such as vacuum processing or steam curing can further reduce open porosity but do not impart intrinsic water-repellent (hydrophobic) properties to the material. Therefore, structural densification alone is insufficient to ensure long-term hydrophobicity of concrete.

An alternative approach to reducing concrete’s water absorption is the use of specialized hydrophobic admixtures introduced directly into the mix [

13,

14]. These admixtures impart water-repellent properties to concrete by forming a hydrophobic layer on the pore walls or by sealing pores with water-insoluble compounds [

15,

16]. Hydrophobic admixtures are conventionally classified as either organic or inorganic.

Organic compounds—such as organosilicon materials (siloxanes, silanes, silicone emulsions), as well as hydrophobic fatty acids and their salts—interact effectively with the cement matrix, creating a hydrophobic coating on the capillary surfaces that reduces water wetting [

17,

18]. However, many organic admixtures are sensitive to the alkaline environment of fresh concrete and may undergo partial degradation or leaching. Therefore, it is essential to select alkali-resistant formulations and determine optimal dosages.

Inorganic hydrophobizing agents—such as complex silicon-containing additives, modified aluminosilicates, and nanostructured compositions—exhibit high thermal and chemical stability [

11,

19]. These substances can also participate in additional crystallization reactions within the cement paste, thereby densifying the matrix while simultaneously reducing its permeability. As a result, inorganic admixtures combine both densification and hydrophobization effects, although they are often more expensive.

One of the most promising directions is the use of multifunctional hydrophobic admixtures that combine water-repellent effects with the ability to interact with cement hydration products [

20]. These admixtures can simultaneously reduce the number of capillary pores and lower their wettability, while also enhancing the strength and durability of concrete due to an additional cementing effect.

Nevertheless, each approach—whether structural densification or the introduction of hydrophobic agents—has its limitations. Excessive reduction of the water-to-cement ratio without maintaining adequate workability complicates concrete placement, while overdosing hydrophobic admixtures may adversely affect cement hydration and mechanical strength. Furthermore, compatibility between hydrophobizing agents and other concrete components—as well as with manufacturing technologies such as vibro-compaction and steam curing—remains a critical concern.

Given these limitations, there is a clear need for a comprehensive approach to concrete mix modification that ensures significant reduction in water absorption without compromising strength. This approach should place particular emphasis on the careful selection of mix components—from the type of cement and mineral additives to the optimal dosage of the hydrophobic agent—tailored to the specific production conditions of reinforced concrete piles.

Currently, there is a sustained interest in the application of hydrophobic technologies in concrete and cement-based materials, particularly under conditions of aggressive moisture exposure, fluctuating climates, and the presence of corrosive agents. The development of hydrophobic concrete compositions is aimed at enhancing water repellency, reducing capillary suction, and, consequently, improving the overall durability of construction materials [

21].

Modern research increasingly emphasizes integral modification of concrete, whereby hydrophobic properties are developed not only through surface treatments but also by incorporating active components directly into the concrete mix [

22]. For example, the study explores methods for achieving a superhydrophobic concrete surface that provides self-cleaning properties and long-term moisture resistance, even under extended service conditions [

23].

Several researchers have systematized approaches to modifying cement-based composites. These include chemical coatings, the use of templated structures, and the incorporation of nanoparticles. It has been confirmed that internal admixtures—particularly those containing nanostructured components—offer more stable and durable effects compared to external coatings [

24,

25].

The particular interest is the impact of hydrophobic admixtures on the long-term durability of concrete. The study demonstrated that properly selected hydrophobic compositions can protect concrete from water ingress and aggressive agents for many years, reducing internal moisture content and minimizing the formation of microcracks [

26,

27]. Similar conclusions are presented in other studies, which reports a significant reduction in water absorption and permeability following the incorporation of nanoscale hydrophobizing agents [

28,

29].

As part of research into the secondary use of materials it has been established that hydrophobic treatments can also enhance the performance characteristics of concrete made with recycled aggregates. This opens up new possibilities for sustainable construction and broadens the application scope of hydrophobic technologies [

28,

30].

From a practical standpoint, some review summarizes the mechanisms underlying hydrophobic effects, the substances employed (e.g., siloxane- and organosilicon-based compounds), and the methods of their incorporation into concrete mixtures [

19,

31]. A critical factor discussed is the interaction of hydrophobic agents with the pore system of concrete, which determines both their efficiency and long-term effectiveness.

Thus, modern approaches to hydrophobic modification of concrete establish a strong scientific and practical foundation for the widespread implementation of such solutions in infrastructure and civil engineering projects—especially under conditions of high humidity, freeze–thaw cycles, and aggressive environments. Numerous scientific publications indexed in Scopus and ScienceDirect confirm the effectiveness and promise of hydrophobic systems as a means to enhance the durability of concrete and reinforced concrete structures.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

In this section, where applicable, authors are required to disclose details of how generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been used in this paper (e.g., to generate text, data, or graphics, or to assist in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation). The use of GenAI for superficial text editing (e.g., grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting) does not need to be declared.

2. Materials and Methods

Achieving hydrophobic and superhydrophobic properties in cement-based materials typically involves three main strategies: surface coating, internal mixing, and templating. Surface coating applies a water-repellent layer, which improves resistance but can be prone to damage. Internal mixing integrates hydrophobic agents throughout the material, offering resilience even if the surface wears, though it might impact mechanical strength. Templating creates micro- or nano-structures that mimic natural hydrophobic surfaces, like lotus leaves, trapping air to achieve superhydrophobicity.

In this study, the internal mixing method was selected to impart hydrophobic properties to cement-based materials. This approach involves incorporating hydrophobic agents directly into the cement mix during the preparation phase, ensuring a uniform distribution throughout the material.

For the experimental study, laboratory concrete samples were prepared with varying contents of a hydrophobic admixture. Sulfate-resistant Portland cement (strength class ≥ 42.5) was used as the binder, and multi-fractional quartz sand was used as the fine aggregate, with a total mass of 1350 g per 450 g of cement. In all mixtures, the water-to-cement ratio (W/C) was maintained at 0.3.

To ensure the required workability at a low W/C ratio, a polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer was added. The dosage was determined experimentally to achieve a flowability equivalent to consistency class P5. The hydrophobic admixture, based on an organosilicon compound, was introduced into the mix in the form of a water-based emulsion at dosages of 0%, 0.2%, 0.4%, and 0.6% by cement mass.

The concrete mix compositions for each series are shown in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Concrete mix composition with varying hydrophobic admixture content (per 1 kg of cement).

Table 1.

Concrete mix composition with varying hydrophobic admixture content (per 1 kg of cement).

| Hydrophobic admixture (% of cement) |

Cement (g) |

Sand (multi-fractional), g |

Water-to-cement ratio (W/C) |

| 0 |

450 |

1350 |

0,3 |

| 0,2 |

450 |

1350 |

0,3 |

| 0,4 |

450 |

1350 |

0,3 |

| 0,6 |

450 |

1350 |

0,3 |

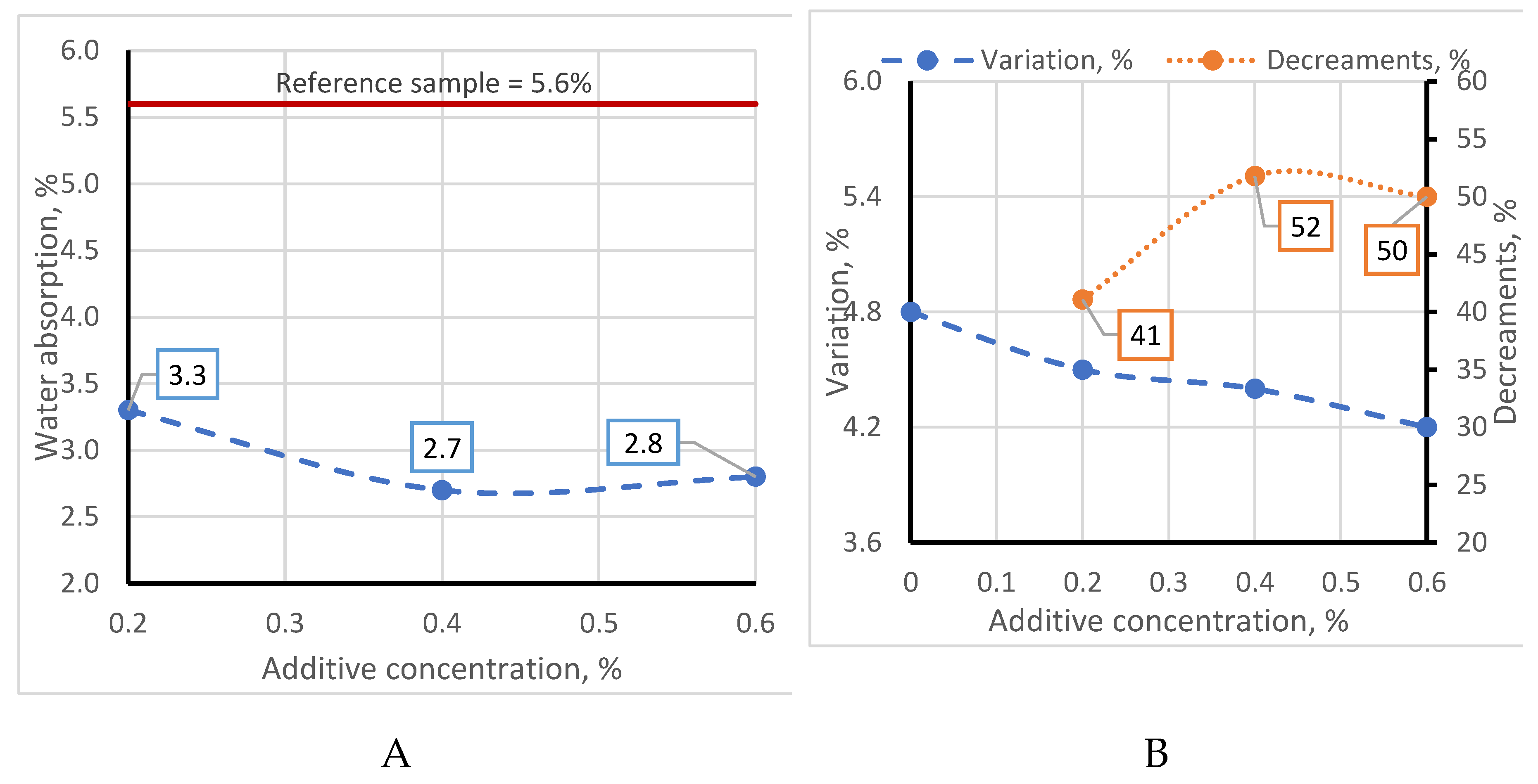

Control specimens were molded from the prepared concrete mixes for testing purposes. To determine compressive strength, cubes measuring 100×100×100 mm were cast for each mix series. Flexural strength was measured using prismatic specimens with a cross-section of 40×40 mm and a length of 160 mm (

Figure 1). The specimens were cast in steel molds and compacted using a vibrating table. After an initial 24-hour curing period at room temperature, the specimens underwent steam curing to simulate plant conditions. The steam treatment was carried out in a chamber at approximately 80 °C for 6 hours, followed by slow cooling, which ensured the development of early-age strength. After curing, the specimens were stored in a moist curing chamber (temperature ≈ 20 °C, relative humidity > 95%) until testing at the age of 28 days.

Compressive strength was determined according to the standard method—by crushing cubes on a hydraulic press, with the average value calculated in MPa (

Figure 2). Flexural strength was determined by three-point bending of prismatic samples (three samples per series, and the result was averaged). Water absorption was determined by mass: the samples, dried to a constant weight, were saturated with water for 48 hours, after which the increase in mass was calculated as a percentage. Water impermeability was assessed using the normative "wet spot" method, determining the maximum water pressure at which no moisture passes through the sample. The result was expressed as a grade for water impermeability, W (e.g., W4, W6, W8, etc., where the number corresponds to the maximum pressure of 0.1 MPa). For each series, the grade for the water impermeability of the experimental samples was determined.

3. Results

The key properties of the obtained concrete samples with varying amounts of hydrophobic additive are summarized in

Table 2. This includes the results of tests for water absorption, water impermeability, and compressive and flexural strength. The introduction of the hydrophobizing additive significantly reduced the water absorption of the concrete and increased its water impermeability. At the same time, the effect of the additive on strength characteristics was noted—at low dosages, the strength increased, while excess additive led to a slight decrease in strength compared to the optimal amount. Detailed data and analysis are presented below.

Table 2.

Properties of Concrete Depending on the Content of the Hydrophobic Additive.

Table 2.

Properties of Concrete Depending on the Content of the Hydrophobic Additive.

| Hydrophobic Additive, % |

Water Absorption, % |

Water Impermeability Grade |

Compressive Strength, MPa |

Flexural Strength, MPa |

| 0 |

5,6 |

W4 |

39 |

4,5 |

| 0,2 |

3,3 |

W8 |

48 |

5,8 |

| 0,4 |

2,7 |

W10 |

45 |

5,1 |

| 0,6 |

2,8 |

W10 |

40 |

4,6 |

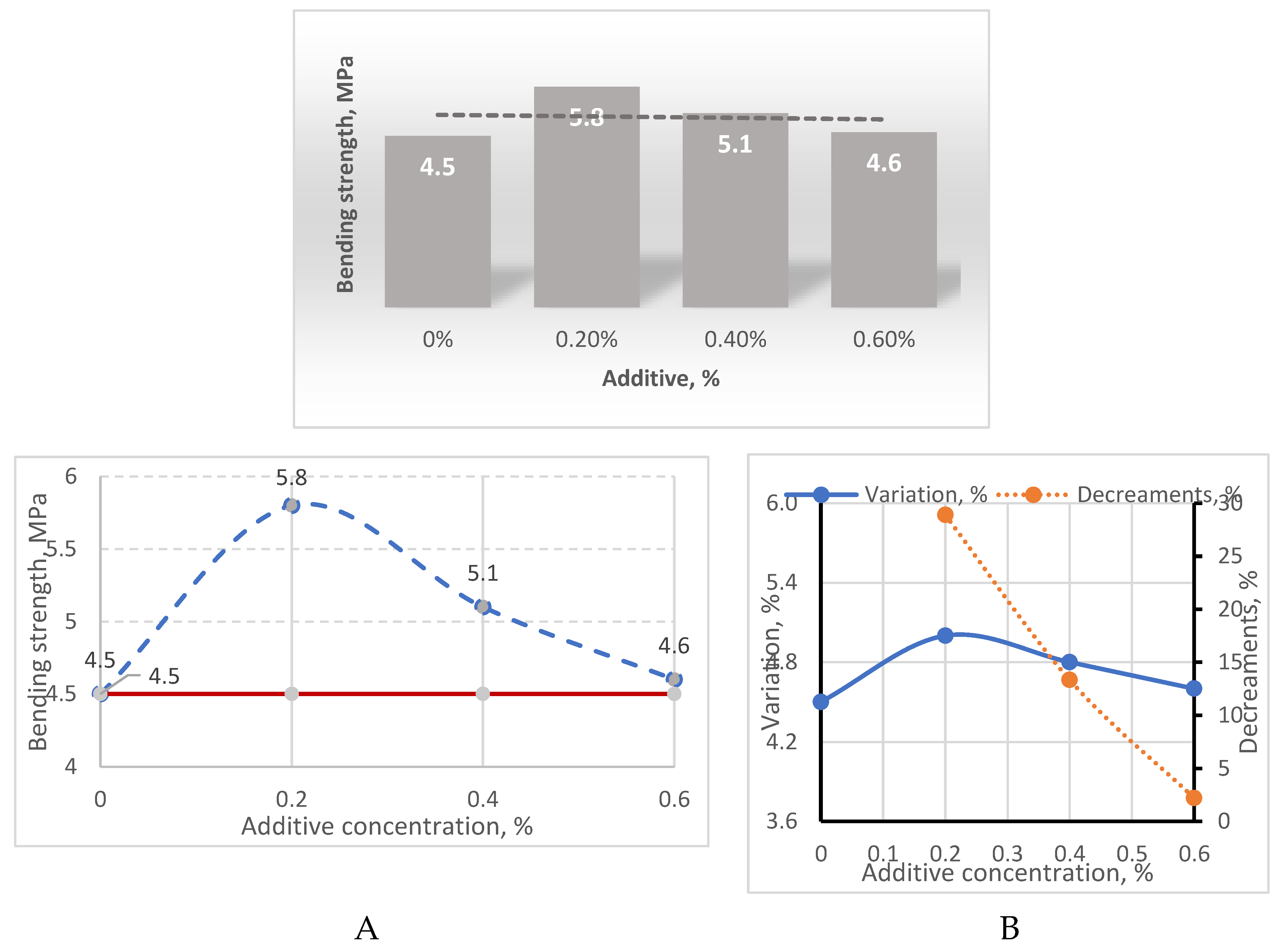

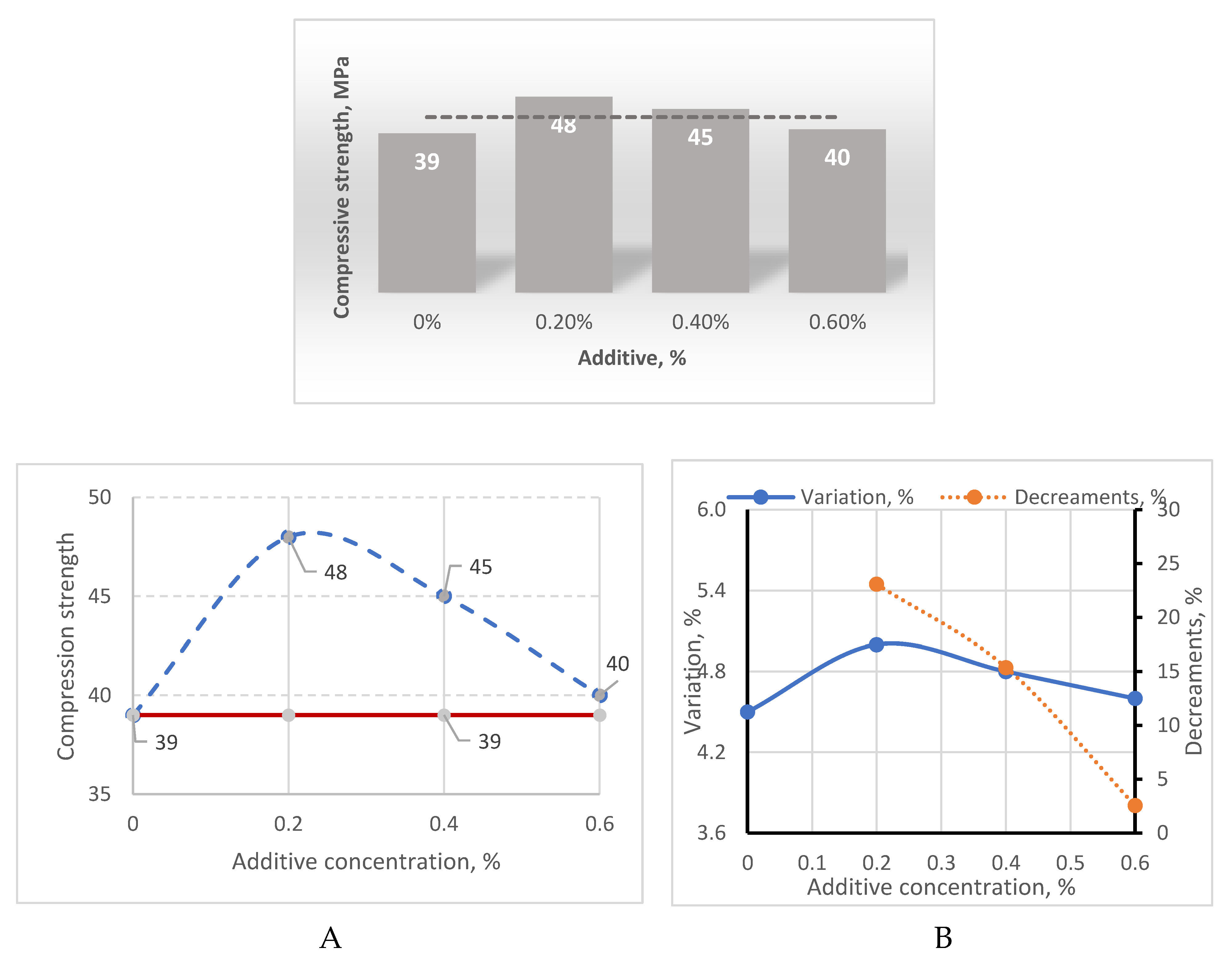

As shown in

Figure 3, the introduction of a small amount of hydrophobizing agent (0.2%) leads to a noticeable increase in compressive strength compared to the control mixture without the additive. The strength increases from 39 MPa (at 0%) to 48 MPa at a dosage of 0.2%, which represents a gain of approximately 23%. This increase in strength can be explained by the densification of the cement paste structure at the optimal dosage of the additive. It is likely that the hydrophobizing agent, in small quantities, helps to distribute water evenly and form a more compact matrix. As the dosage increases to 0.4%, the strength slightly decreases (to 45 MPa), and at 0.6%, it returns to a level around 40 MPa. The reduction in strength at higher doses is likely due to the excessive amount of hydrophobic substance, which disrupts the material's structure or prevents complete cement hydration. Thus, there is an optimal dosage of the hydrophobizing additive, exceeding which leads to a loss of its positive effect on strength properties.

The trend in the change of flexural strength is similar to the dynamics of compressive strength (

Figure 2). The maximum value of flexural strength is observed at an additive dosage of 0.2%, around 5.8 MPa compared to 4.5 MPa for the non-filled concrete. A moderate amount of hydrophobizing agent likely improves the bond between the cement paste and the aggregate, which positively affects the flexural resistance. As the additive content increases to 0.4%, the flexural strength slightly decreases (to 5.1 MPa), and at 0.6%, it almost returns to the original level (4.6 MPa). Although these changes are not as pronounced as those observed for compressive strength, they confirm that an excess of the hydrophobic additive can neutralize its positive effect. Even at the maximum dosage of 0.6%, the flexural strength is slightly higher than the initial value, but the gain is minimal, whereas the optimum of 0.2% results in the greatest strength increase.

Figure 4.

Influence of Hydrophobic Additive Content on the Tensile Strength of Concrete.

Figure 4.

Influence of Hydrophobic Additive Content on the Tensile Strength of Concrete.

Figure 5.

Influence of Hydrophobic Additive Content on the Water Absorption of Concrete.

Figure 5.

Influence of Hydrophobic Additive Content on the Water Absorption of Concrete.

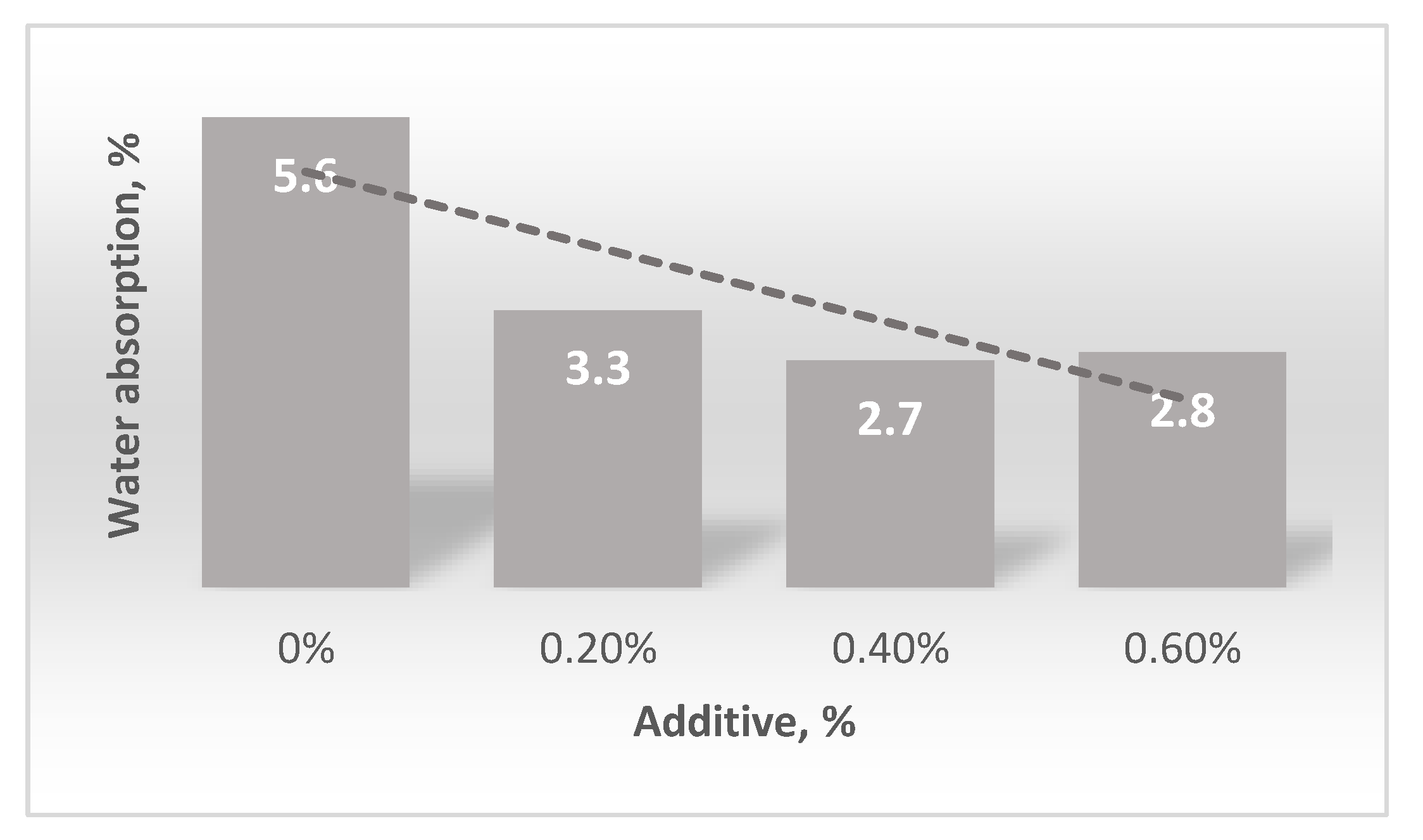

The hydrophobizing additive had the most significant impact on the water absorption of concrete (

Figure 3). An additive of just 0.2% by weight of cement reduced the water absorption almost by half— from 5.6% to 3.3%. At a dosage of 0.4%, water absorption decreases even further, to 2.7%, indicating a pronounced hydrophobic effect in the material structure. Further increasing the dosage to 0.6% does not provide a noticeable additional effect (water absorption is 2.8%, almost at the same level). The obtained results indicate the existence of a saturation limit in the structure of the hydrophobic agent: when the concentration exceeds a certain threshold, the capillaries of the concrete are already completely covered with a water-repellent layer, and additional additives do not reduce water absorption further.

The reduction in water absorption is directly related to the increase in water impermeability of the concrete. The original concrete had a water impermeability grade of W4 (which corresponds to withstanding water pressure of approximately 0.4 MPa), but with the addition of 0.2% additive, the water impermeability increased to W8. At 0.4% and 0.6%, the samples reached a W10 grade, meaning they were able to withstand a pressure of around 1.0 MPa without water penetration. The increase in water impermeability class from W4 to W10 indicates a significant improvement in the concrete structure’s resistance to water filtration under pressure. It is likely that the hydrophobizing additive forms a thin film on the pore walls, which prevents water penetration, and may also contribute to additional filling of the pores with reaction products (in the case of silica-containing compositions). As a result of this combined effect—matrix densification and reduced wettability—concrete acquires a stable hydrophobic barrier. This is especially important for piles used in moist soils: reduced water absorption and increased impermeability will prevent the leaching of the cement paste and protect the reinforcement from corrosion, thereby extending the service life of the structure.

4. Discussion

The results obtained in this study clearly show that adding a small amount of a hydrophobic additive based on organosilicon compounds significantly improves the waterproofing properties of concrete without compromising its mechanical characteristics. The observed decrease in water absorption from 5.6% to approximately 2.7% and the simultaneous increase in water resistance from W4 to W10 confirm the formation of a stable hydrophobic barrier in the cement matrix. This improvement can be explained by the dual mechanism of action of the additive — both physical blocking of capillary pores and chemical modification of the pore surface by adsorption of hydrophobic compounds. There are research, which reported that silane- and stearic acid-based water-repellent agents effectively reduce water permeability by changing the surface energy of the pores while maintaining the overall integrity of the matrix [

32,

33].

The enhancement in compressive and flexural strength at the optimal dosage (0.2 % by cement mass) indicates that the hydrophobic admixture not only limits capillary water ingress but also contributes to microstructural densification. This phenomenon aligns with the findings of related research [

34,

35], who demonstrated that composite hydrophobic agents can act as secondary cementitious materials, filling microvoids and promoting additional hydration products that strengthen the interfacial transition zone.

At higher dosages (≥ 0.4 %), however, the decrease in strength observed in this work may result from incomplete cement hydration or weak interfacial bonding due to the excessive accumulation of hydrophobic films [

36]. Therefore, the dosage of the hydrophobizing admixture must be optimized to balance its beneficial and adverse effects.

The optimal dosage range (0.2–0.4 %) established in this study provides a practical guideline for industrial applications, balancing the desired hydrophobicity and mechanical integrity. The obtained compressive strength of 45–48 MPa and water impermeability grade W10 exceed the minimum durability requirements specified for piles subjected to groundwater exposure in cold regions.

Future research should focus on evaluating the long-term performance of the developed hydrophobic concrete under cyclic wetting–drying, freeze–thaw exposure, and chloride penetration tests. It is also important to investigate the compatibility of different hydrophobic agents with supplementary cementitious materials such as fly ash, metakaolin, and silica fume, which may further enhance the synergy between densification and water repellency. Additionally, advanced microstructural analyses using SEM, XRD, and contact-angle measurements can clarify the mechanism of hydrophobic film formation and its stability over time.