1. Introduction

The energy sector is moving away from centralised, fossil-based generation, towards decentralised renewable-driven systems. This transition is made possible by the growing availability of small-scale generation technologies like rooftop solar panels, which allow consumers to become active participants in the energy system. In this context, energy communities have emerged as local collectives that can produce, consume, store, and manage energy together. However, setting up and managing such a community is a complex task. Members may have conflicting priorities, energy consumption patterns, renewable energy production is not constant, and the regulatory and pricing environment is still evolving. Traditional approaches using RBCs can be too rigid in such dynamic environments.

This paper explores the potential of Reinforcement Learning as an adaptive solution for energy management optimization in energy communities. The advantage of reinforcement learning agents is their ability to learn optimal strategies through direct interaction with the environment, without requiring a complete mathematical model of the system, allowing them to learn an intelligent control strategy which can maximize the economic and environmental benefits of integrating local renewable energy resources.

To evaluate the potential of reinforcement learning under realistic conditions, this study examines three diverse community schemas. Each schema is meant to represent a different scenario in which an energy community might find itself in. The first schema represents a heterogeneous community, with both prosumers and consumers, meant to simulate more diverse and non-ideal configurations. The second schema represents a small community with a large producer, meant to simulate small communities which include a commercial space, like a supermarket, with different consumption patterns and production capabilities. And the third configuration is similar to the second, however it represents an ideal energy community in which all members are prosumers, with the ability to store energy.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the state of the art and related work in microgrid optimization and energy management.

Section 3 describes the methodology used, presenting the three energy communities scenarios used, the CityLearn simulation environment, and the implementation of the PPO agent.

Section 4 presents and compares results obtained by the PPO, the RBC, and baseline scenario.

Section 5 discusses these results, the limitations of this study, highlights the conclusions, and presents future research directions.

2. Key Research Directions in Microgrid and Energy Community Management

2.1. Microgrid and Energy Storage Optimization

Modern research focuses on optimizing microgrid configurations to balance economic viability and operational ability. Often targeting commercial or remote applications [

1,

2]. These models usually focus on minimizing net present cost and carbon emissions while ensuring demand is met, either through backup generators or smart battery state management. Real-time energy monitoring is a key component of Industry 5.0’s energy efficiency efforts. Smart Grids leverage IoT sensors to capture and analyze energy consumption data in real time, enabling a deeper understanding of energy usage patterns and identifying areas of potential energy wastage. Smart Grids are equipped with IoT sensors that are installed at various points within the grid, including households, businesses, and industrial facilities. These sensors continuously collect data on energy consumption, such as electricity usage, voltage levels, and power quality parameters.

The IoT sensors transmit the collected data in real time to a centralized monitoring system. This data includes information on energy consumption patterns, usage trends, and peak demand periods. It provides a comprehensive view of the energy flow throughout the grid and identifies areas where energy efficiency improvements can be made. The real-time energy consumption data is analyzed using data analytics techniques, including machine learning and AI algorithms. These algorithms identify patterns, anomalies, and correlations within the data, enabling insights into energy usage behaviors and potential areas of energy wastage. Real-time energy monitoring helps in identifying peak demand periods accurately. With this information, energy providers can implement demand-response strategies to manage peak loads efficiently. By incentivizing consumers to shift their energy usage to off-peak hours or adjust their consumption during peak periods, the grid’s overall energy efficiency can be improved.

The insights derived from real-time energy monitoring can be used to provide personalized recommendations and feedback to consumers. By analyzing individual energy consumption patterns, consumers can receive suggestions on how to reduce energy waste and optimize their usage. This can include tips on adjusting thermostat settings, optimizing lighting usage, or upgrading to energy-efficient appliances.

Overall, real-time energy monitoring enables utilities, businesses, and consumers to make data-driven decisions to improve energy efficiency. By identifying energy usage patterns, peak demand periods, and causes of power losses, real-time monitoring allows targeted interventions and optimization strategies that contribute to a more sustainable and efficient energy ecosystem.

In recent years, there has been an increasing trend of production capacities from renewable sources, i.e., wind and solar power plants. Recently, various research has been performed on different types of floating offshore wind turbines and floating photovoltaic energy yield and performance models, designing optimized structural platforms for climate-resilient systems. Thus, in the technological mix of the electricity production system, the share of energy produced from renewable sources increases. The problem that arises in the case of energy produced from renewable sources is that it has an intermittent character, that is, at night or when the wind is not blowing, the energy production is minimal, and if the sun shines brightly or the wind blows, a large amount of energy is produced, sometimes even an amount that cannot be consumed at that moment. For this reason, capacities are needed to ensure the flexibility of the power system and to be able to respond quickly to the intermittency of wind and solar radiation, i.e., when too much energy is produced, to store the excess energy, and when the production is minimal, to release the stored energy. A solution would be the use of technologies for energy storage, such as high-capacity batteries, the most common and practically deployable solution to support renewable integration and local flexibility.

2.2. Grid Robustness and Resilience.

Grid robustness and resilience have also been notable areas of research in recent studies regarding modern power systems. In the context of energy communities, robustness generally refers to the energy system’s ability to maintain stable functionality under expected conditions without performance degradation. Resilience generally refers to an energy system’s ability to recover from or resist more rare or extreme conditions, such as natural disasters or large-scale equipment failure [

3].

As small-scale renewable energy solutions become more popular, traditional centralized control strategies may struggle to fulfill these requirements, making local or community level control strategies necessary [

4]. These community level control strategies can improve voltage stability, reduce stress on the distribution network and maintain functionality during faults by taking advantage of techniques, such as intelligent scheduling, load shifting and distributed storage coordination.

Grid resilience research is also being conducted on the physical side of energy communities and microgrids implementations. Bi-directional power flow, voltage deviations, and network losses are being addressed through energy transaction algorithms and efficient PV placement [

5,

6,

7].

Physical resilience measures, such as grid segmentation, islanding, backup generators, additional power lines and communication redundancy remain popular, however recent research hints towards a shift from traditional hardware reinforcement to resilience through control strategies. Adaptive and A.I. controllers can detect abnormalities and recover easier from failures by dynamically configuring microgrids and managing distributed storage. Together, these studies suggest that resilience and robustness cannot rely only on physical redundancy, but must also incorporate intelligent coordination.

2.3. Transactive Energy and Market-Based Coordination

Transactive Energy Frameworks (TEFs) are a modern approach to coordinate distributed energy resources and improve local autonomy by facilitating structured interactions between prosumers, aggregators and the main grid [

7,

8]. By dynamically pricing electricity based on supply and demand conditions, these frameworks encourage participants to adjust consumption, generation, and storage schedules in a way that benefits both the local community and the grid operator. [

9,

10]

In such systems, coordination mechanisms are varied. Peep-to-peer (P2P) trading is one such coordination mechanism, which allows for direct energy trades between members of a community, either for free or at a discounted rate, to encourage consumption of self-generated energy and discourage dependency on the grid [

1,

5]. Another example of a TEF are aggregator-based structures, which uses a central agent to manage energy transactions within a community, and can offer better scalability than P2P, requiring less infrastructure to be implemented. The use of blockchain technology and smart-contract platforms have also been proposed to record and validate transactions within the community, ensuring transparency and trust without the need of a central intermediary [

3,

4].

However, implementing TEFs comes at the cost of new operational and computational challenges. Managing a large number of transactions, forecasting demand and generation, and determining fair and stable prices require adaptive control. Reinforcement learning agents have shown strong potential in bidding automation, pricing, and scheduling decisions by learning optimal policies directly from market feedback [

11,

12]. Multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) techniques are proposed to enable decentralized negotiation between members of a community, leading to faster convergence without the need of a central coordinator. Despite these advances, several challenges remain. Designing fair compensation and incentive mechanisms and interoperability of heterogeneous members are still active areas of research, especially when integrating services such as demand response and storage dispatch in community-level markets [

13].

Research suggests that combining market-based coordination with adaptable strategies, such as the PPO agent explored in this study, could provide a balanced framework which merges economic efficiency with operational adaptability [

14,

15].

2.4. Challenges

Energy communities are often made up of many actors, each with their own infrastructure, usage patterns, demands, and priorities. Within a single community, some buildings might have solar panels, and batteries, while others are supplied only from the grid. Some members might have fixed consumption patterns while for others these vary. Weather variability is another challenge, most renewable energy in these communities come from solar panels, which only produce energy during the day and are very sensitive to weather fluctuations. Coordinating the operation of multiple distributed storage devices across a long time horizon results in a very large search space. The scheduling problem becomes NP-hard, meaning that the number of possible control actions grows exponentially with the number of buildings, devices, and time steps [

16]. This motivates the use of reinforcement learning or genetic algorithms, which can approximate near-optimal solutions without a complete state space search.

Even if technical solutions are in place, the problem of coordination remains. The members of the community have different production capabilities, load demands, and consumption patterns. Prosumers, aggregators, and collaborative networks of prosumers play an important role in ensuring resilience and in exploiting renewable energy sources in such a way as to achieve sovereignty over critical resources for the future [

12,

17].

Due to the complexity and variability of managing energy communities, traditional rule-based approaches might be hard to build or have poor performance. Reinforcement Learning learns from interacting with the environment, without requiring a full model of the system, learning directly from data, making it a fitting solution for systems with unpredictable dynamics.

While existing studies have explored microgrid optimization, storage strategies, and even reinforcement learning for demand response, several limitations remain. Many studies rely on rule-based controllers, which cannot adapt dynamically to uncertain conditions. Other studies apply reinforcement learning but focus narrowly on a single objective, such as cost minimization, without considering the impact on emissions, grid stability, or fairness. Comparative studies across heterogeneous communities, which include transactional systems like peer-to-peer energy sharing, and the use of aggregators are also scarce. In addition to rule-based approaches, many studies have applied multi-objective optimization algorithms, such as genetic algorithms or Pareto-based methods for P2P transactions in energy communities (e.g., NSGA-II). These methods are effective in exploring trade-offs between costs, emissions, and stability, but they require extensive offline computation and rely on predefined objective functions, making them more challenging to implement. Our work aims to fill this gap by testing a PPO-based reinforcement learning agent for three representative community schemas, and comparing the agent’s performance against traditional rule-based controllers [

18,

19].

3. Reinforcement Learning for Energy Communities

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a machine learning paradigm that fits problems which involve sequential decision making in uncertain environments. RL agents learn from feedback given from the environment to the agent in the form of rewards or punishments. In energy communities, the environment could represent the electrical grid, buildings, storage systems, and solar panels, while rewards could be represented by cost savings, carbon footprint reduction or meeting demand. What makes RL a good fit for this task is its ability to adapt to dynamic or incomplete systems, weather patterns, consumption habits, and system constraints. For example, an agent could learn when to charge or discharge a battery depending on predicted solar generation and user demand.

3.1. Research Objectives and Problem Formulation

The primary research objective of this work is to explore the viability and effectiveness of Reinforcement Learning as an energy management system for energy communities with access to renewable energy. The aim is to show how an RL-based agent can optimize dispatch decisions to minimize costs, and the environmental impact, comparing results for multiple scenarios. These scenarios range from a non-optimised configuration, where buildings draw energy from the grid whenever required (Grid-only), to a passive utilization of local photovoltaic generation without coordinated storage management (Grid + Solar). Finally, more advanced control strategies are explored, including a rule-based controller (RBC) and a reinforcement learning (PPO) agent.

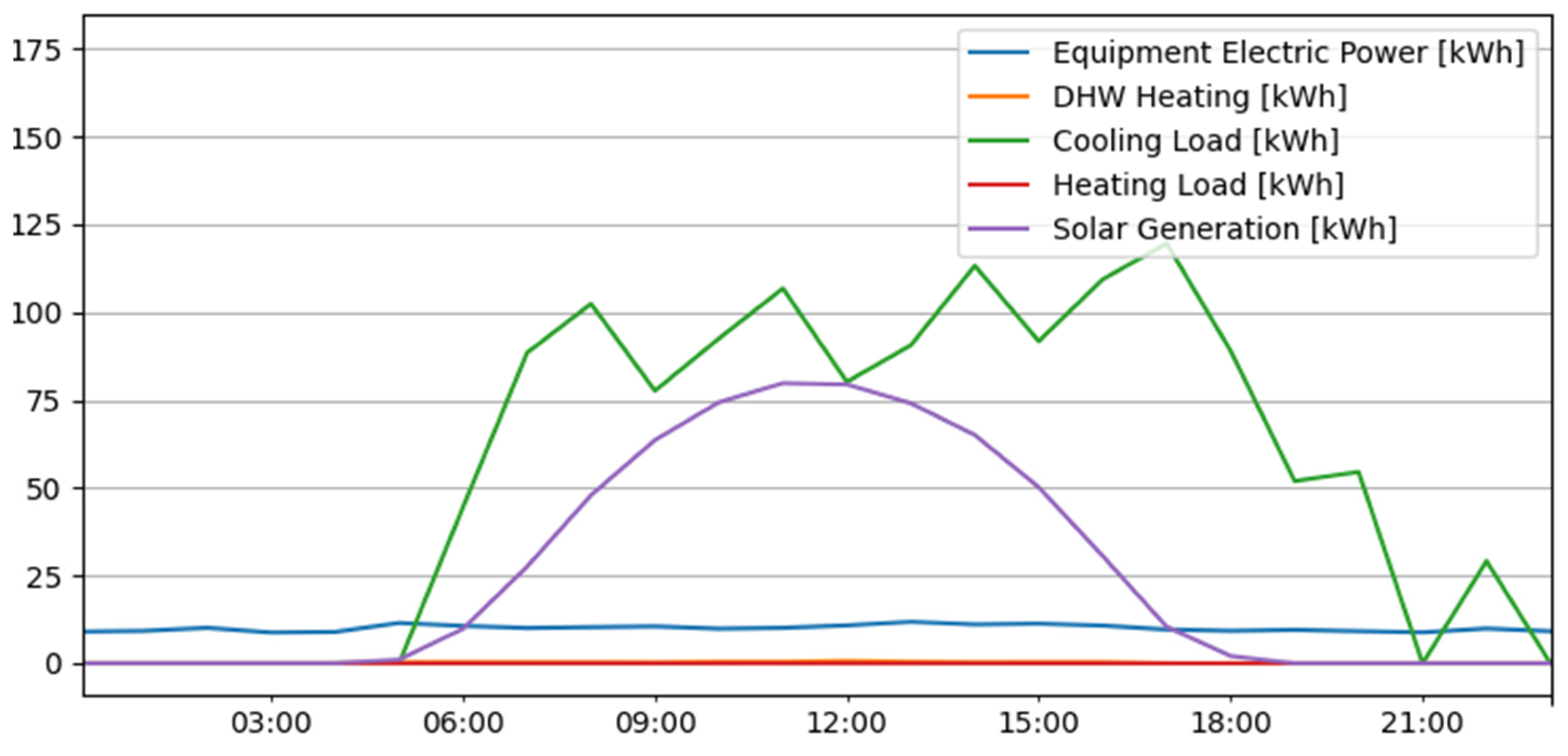

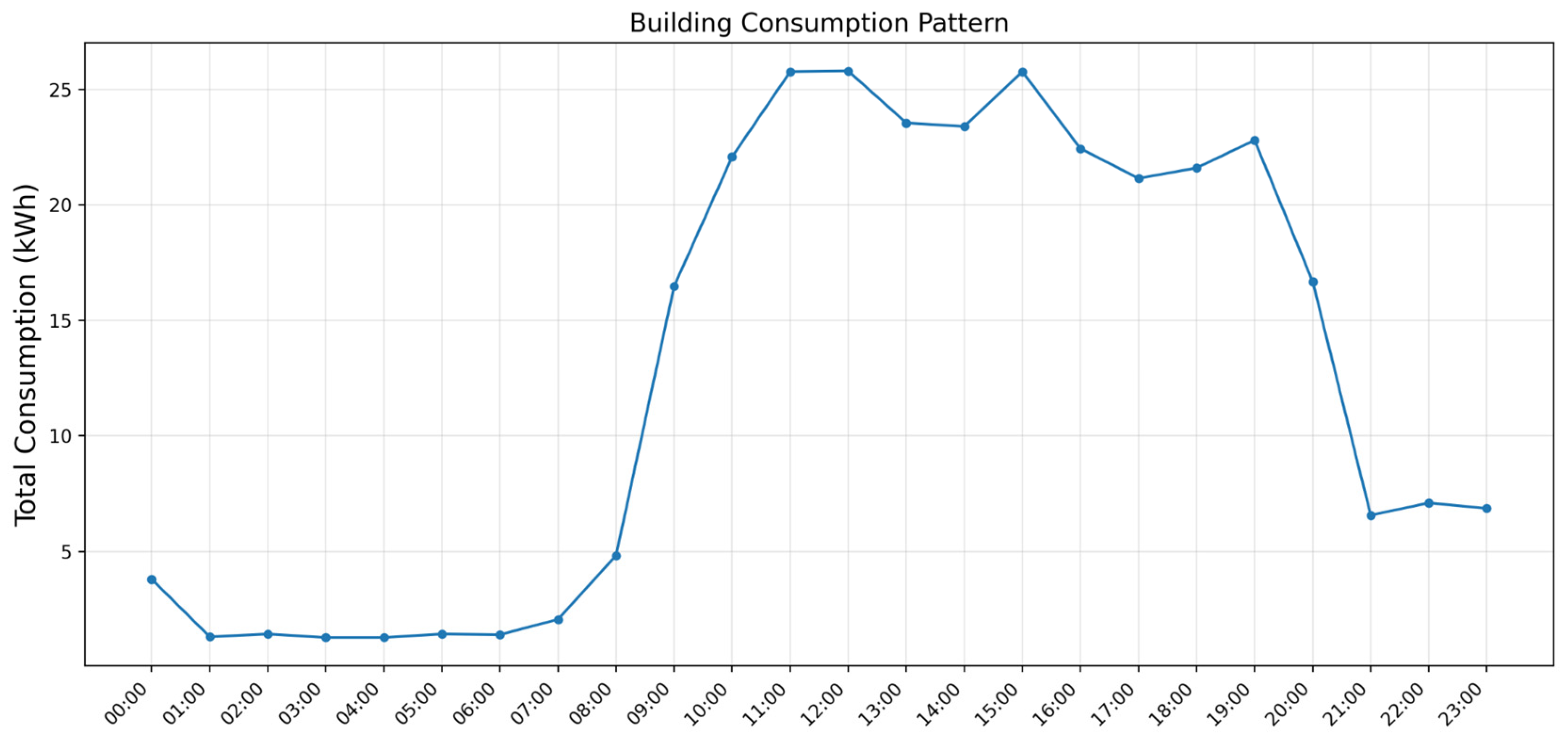

Figure 1.

Sample of energy loads and PV production over 24 hours

1.

Figure 1.

Sample of energy loads and PV production over 24 hours

1.

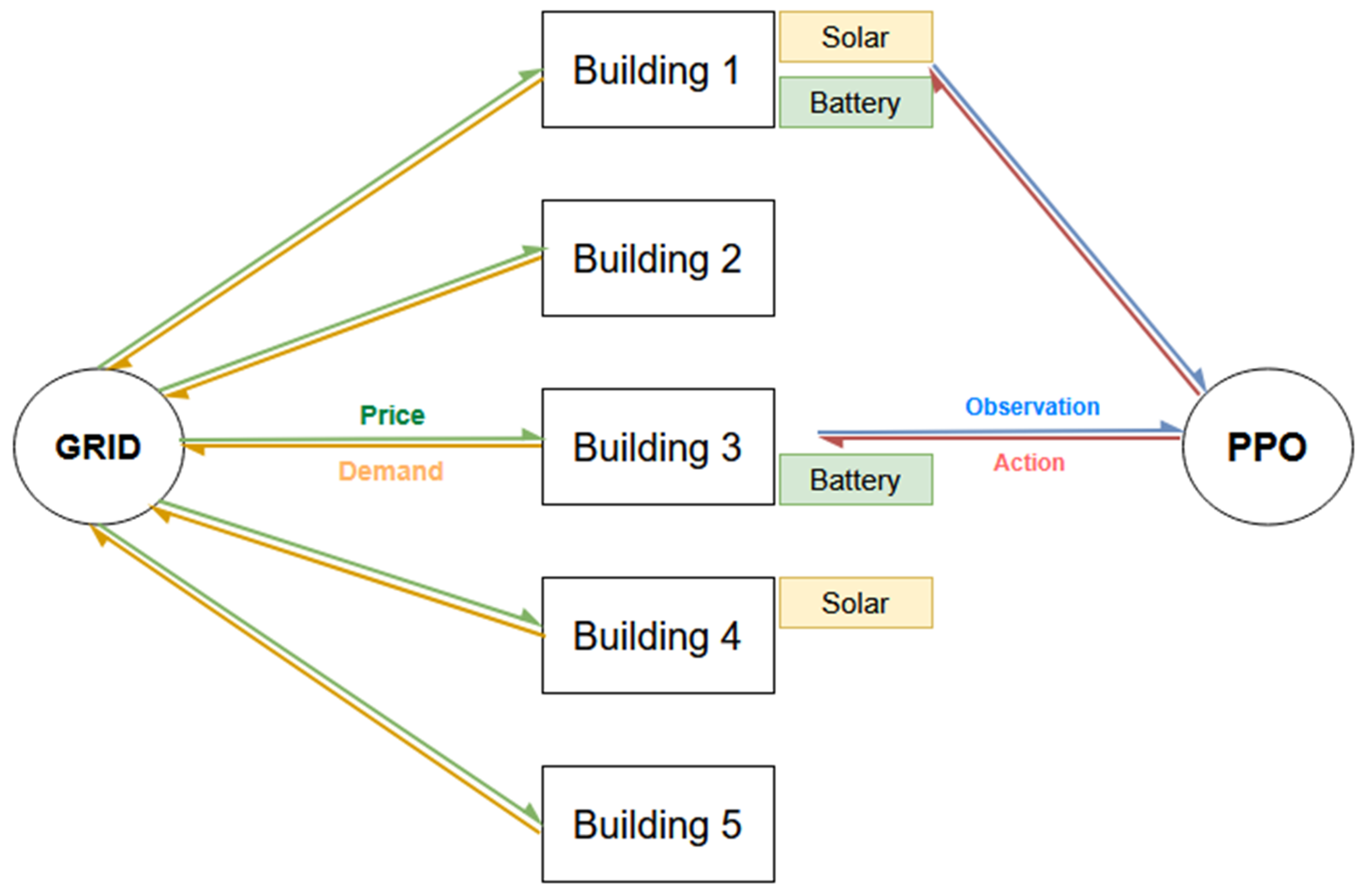

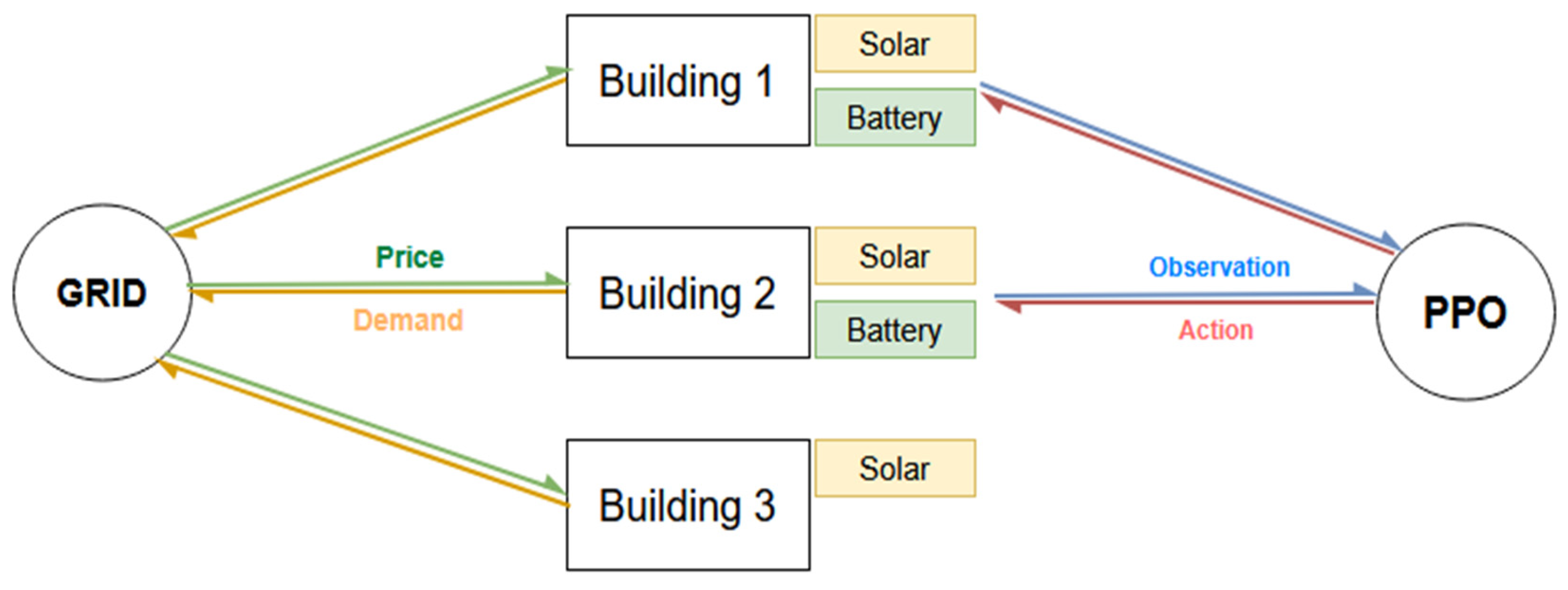

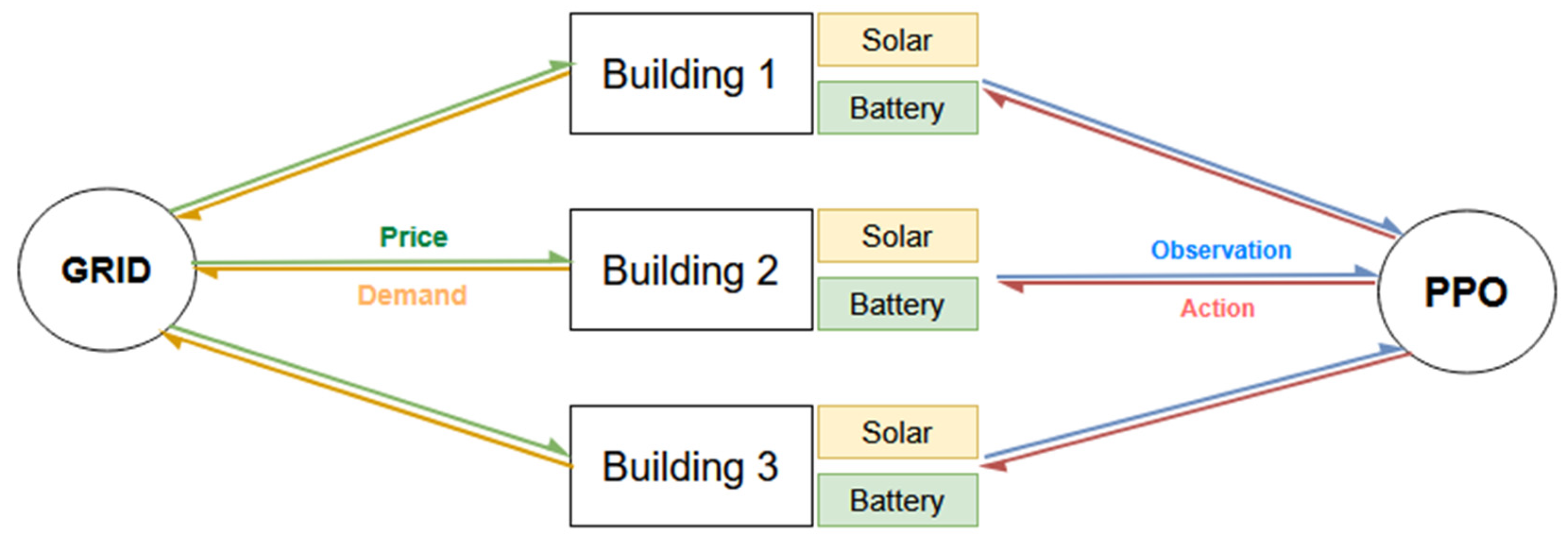

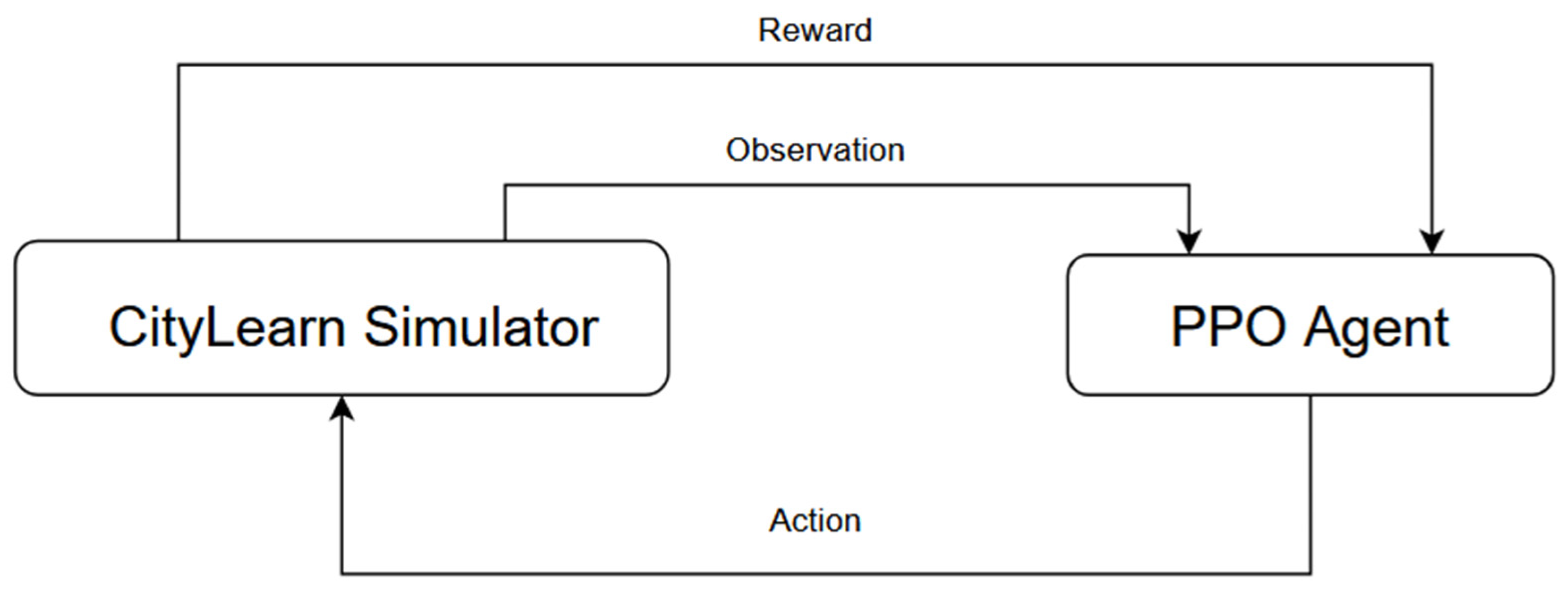

In this work we focus on three schemas, simulating multiple realistic energy community configurations. The buildings interact directly with the grid, and indirectly with each other. When local production does not exist or is not sufficient, demand is covered by imports from the grid, while excess generation can be stored in local batteries or sold back into the grid. The PPO agent observes these interactions and decides in real time whether to charge or discharge available batteries, while the rule-based controller follows fixed schedules based on the time of day, without adapting dynamically to load or generation variability. These communication signals can be seen in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, where the buildings demand a certain amount of energy from the grid, which supplies them with the requested energy at a given cost, whereas the PPO agent observes the current state and, where possible, makes a decision whether to charge or discharge the batteries.

Schema 1, seen in

Figure 2 and described in

Table 1, models a community of 5 residential buildings. Building 1 is a regular prosumer, with a battery and PV, buildings 2 and 5 represent a typical consumer, with neither solar or storage capabilities, while building 3 only has PV, and building 4 only storage capabilities. Building 4 includes only an energy storage system, without local PV generation. This was introduced to test whether a storage-only participant could provide value through energy arbitrage or load balancing within the community. Consumption patterns for residential buildings are provided by the CityLearn framework and represent cooling load, heating load, domestic hot water (DHW) demand, and general appliance and lighting consumption (see

Figure 1).

Schema 2 simulates a smaller community of 3 entities, 2 regular prosumers and a third entity with a larger power consumption and generation capacity, but without a battery, similar to a local supermarket (see

Figure 3 and

Table 2).

Schema 3 is similar to schema 2, but the third building has a battery. It simulates an ideal case, a small community in which all participants are prosumers (see

Figure 4 and

Table 3).

3.2. Environment and Simulation

The environment in which our RL agent trains is CityLearn

2 [

20,

21]. CityLearn is an open-source environment built on the OpenAi Gym interface, developed for testing energy management strategies in building clusters and urban energy communities. It includes components that simulate building electricity demand, photovoltaic generation, energy storage systems, and dynamic grid pricing. This framework provides realistic datasets based on real measurements and supports both centralized and multi-agent control schemes.

In our implementation, the three community schemas defined in

Section 3.1 were configured through the framework’s JSON environment files by specifying the number of buildings, their generation and storage capacities, and load profiles. The chosen schemas were inspired by the values given in the CityLearn Challenge 2021 datasets. [

22]. Since CityLearn is open-source, it can be extended by modifying or adding environment components, such as custom reward functions, new state variables, or peer-to-peer trading mechanisms, allowing for future work involving transactive energy systems.

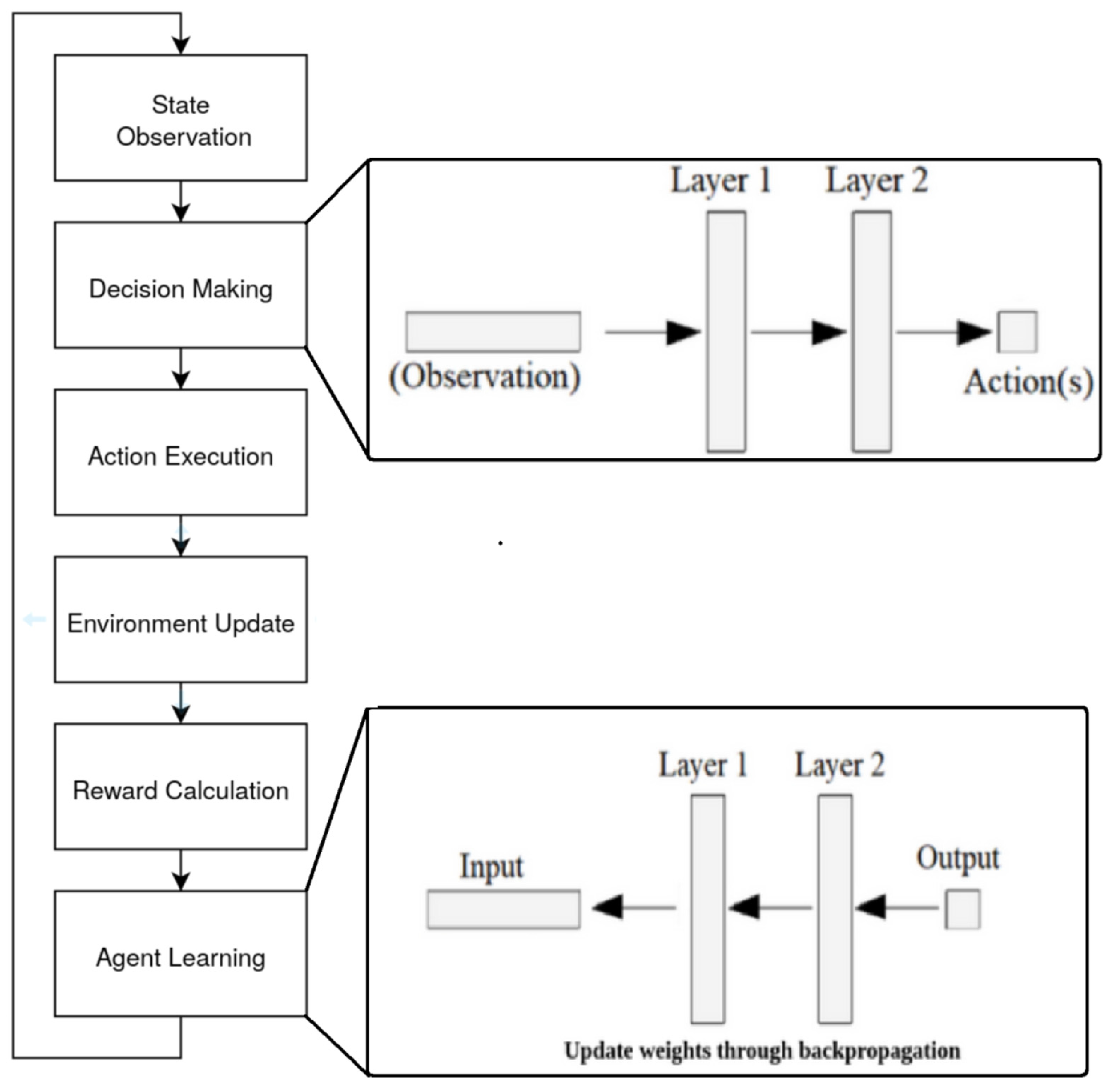

Figure 5 illustrates the general flow of reinforcement learning training. The process begins when the environment provides the agent with a state observation

3, based on this, the RL agent’s neural network generates an action

4. This action is then applied to the simulated environment, which then updates its state, returning a reward signal

5 and a new state observation. This cycle continues for every step in the simulation, until the episode is done, allowing the agents to learn optimal strategies through experience rather than explicit programming.

By default, each building operates independently, drawing electricity from the grid whenever local PV generation or battery storage cannot meet its demand. This approach ensures the demand is met but results in high grid dependency, energy costs and emissions. To lower energy costs and carbon emissions, control strategies can be implemented to manage how and when each building uses or stores energy. In this study, two control strategies are evaluated and compared against a non-controlled baseline, where solar energy is used directly. The first strategy is a Rule-Based Controller (RBC), which follows a fixed schedule for charging and discharging. The second is a reinforcement learning proximal policy approximation (PPO) agent, which learns optimal control strategies through interaction with the environment. An example of how a control strategy could lower costs is energy arbitrage, taking advantage of lower energy prices during the night to charge the battery, and discharge it when energy is more costly during the day. Unfortunately, this scenario is not available in every country, differentiated prices at different times of the day not yet being regulated [

12].

3.3. State, Action, and Reward Spaces

In our case, a state is represented by a series of values which describe the environment at each step, i.e., current and predicted electricity prices, carbon footprint metrics, outdoor temperature and energy loads (see

Table 4).

A possible action in this environment represents a decision to charge or discharge an energy storage device and how fast. Values are normalized between -1 and 1, where 1 is charging as fast as possible and -1 represents a discharge as fast as possible.

The reward function in training RL is designed to guide the agent towards a desired behavior. Initial experiments focused on minimizing wasted energy generated by PV, however this caused the agent to only charge the battery, never actually using it in fear of wasting some solar energy. When the reward function was changed to focus on decreasing the overall energy consumption the agent learned a more balanced strategy. The exact formula used to calculate the reward was:

where

e is net energy consumption, thus punishing the agents for consuming energy from the grid, guiding them towards focusing on self-sustainability, and lower power peaks.

3.4. Algorithm and Training

Figure 1 and

Figure 6 give a more detailed energy profile for a generic actor in a community. Generally, energy usage starts at ~07:00 and continues well into the evening. And the solar generation starts a bit earlier at ~06:00, with a drastic decrease at ~14:00. Provided with this information, the RBC was set to charge as fast as possible when the energy is the cheapest, during the night (22:00 - 06:00), to rely on solar generation at peak hours (07:00 - 14:00), and to discharge during the evening (14:00-22:00) when the solar generation cannot cover the consumption anymore.

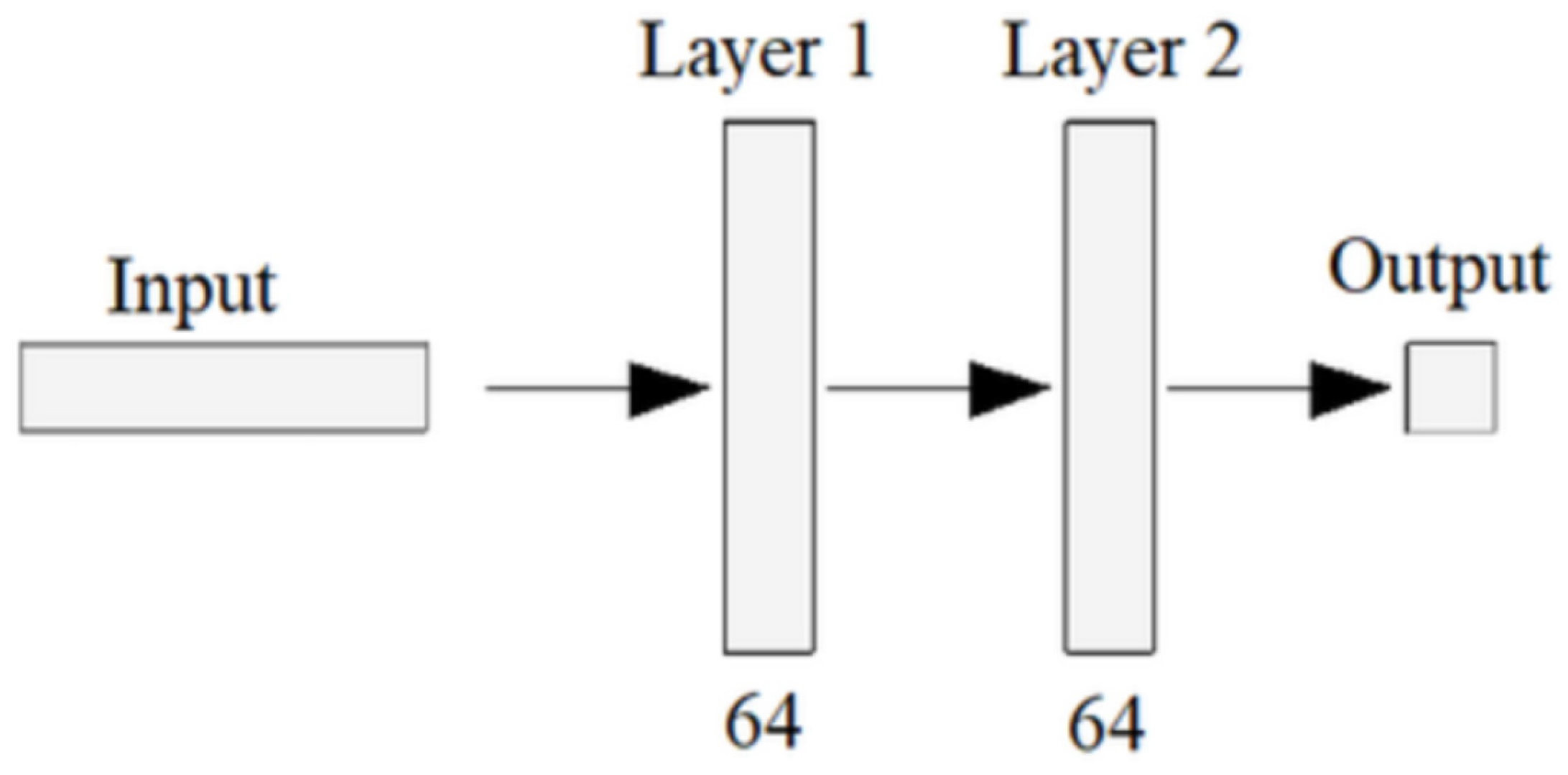

We chose PPO as the RL algorithm due to its ability to work with environments with continuous action spaces and robustness during training. PPO’s implementation prevents the sudden performance drops which appear due to large updates present with other RL implementations. We used the standard PPO implementation from the Stable Baselines3 library, 2 fully connected layers of 64 neurons each (see

Figure 7). Given the tabular nature of the data, no convolutional layers were used, because the improvement in the feature extraction does not compensate for the additional computational cost. Similar architectures have been applied to energy management and demand-response problems, showing PPO’s stability and sample efficiency in continuous microgrid environments [

23].

The simulation and decision making process follow the steps shown in

Figure 8. It gets an observation from the environment, this is passed through the agent’s neural network, and the dispatcher selects an action using the neural network’s output. After selecting an action, the environment is updated using the selected action, and the reward is calculated using the reward function, which helps the agent’s network to make better decisions.

Table 5.

Hyperparameters used for training the RL agent.

Table 5.

Hyperparameters used for training the RL agent.

| Hyperparameter |

Value |

Description |

| Training steps |

400,000 |

Total number of environment interactions used for training. This determines the overall training duration. |

| Learning rate |

0.0001 |

Step size for gradient updates. Small values slow down convergence but also ensure gradual stable learning. |

| Gamma |

0.99 |

Discount factor which controls how much future rewards influence current decisions. |

| Batch size |

64 |

Number of samples used per gradient update. |

| Steps per update |

2048 |

Number of environment steps collected before each policy update. |

| Epochs |

10 |

Number of passes over each batch during optimisation |

| GAE Lambda |

0.95 |

Generalised Advantage Estimation. Trades off bias and variance in advantage computation for smoother learning. |

4. Results

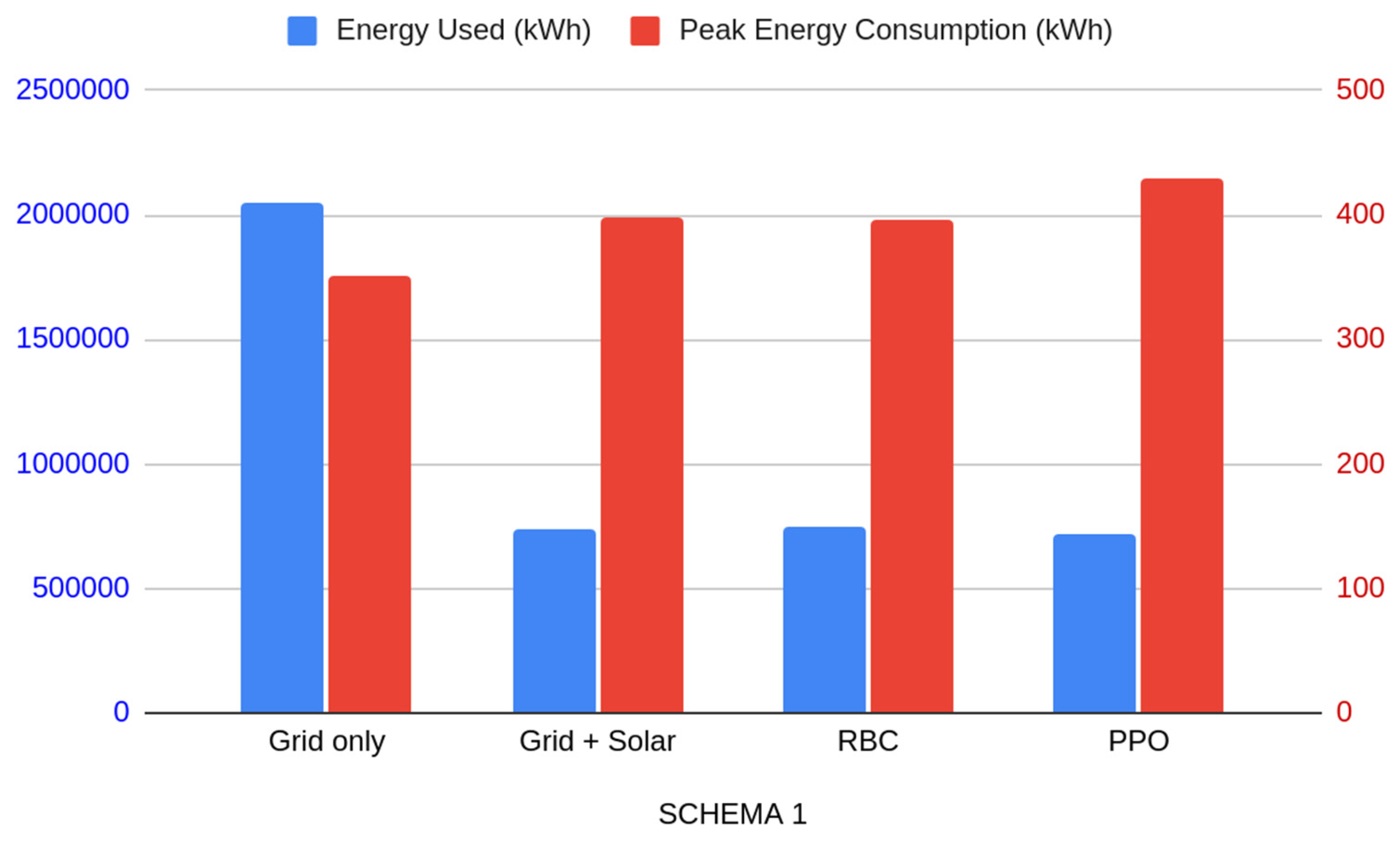

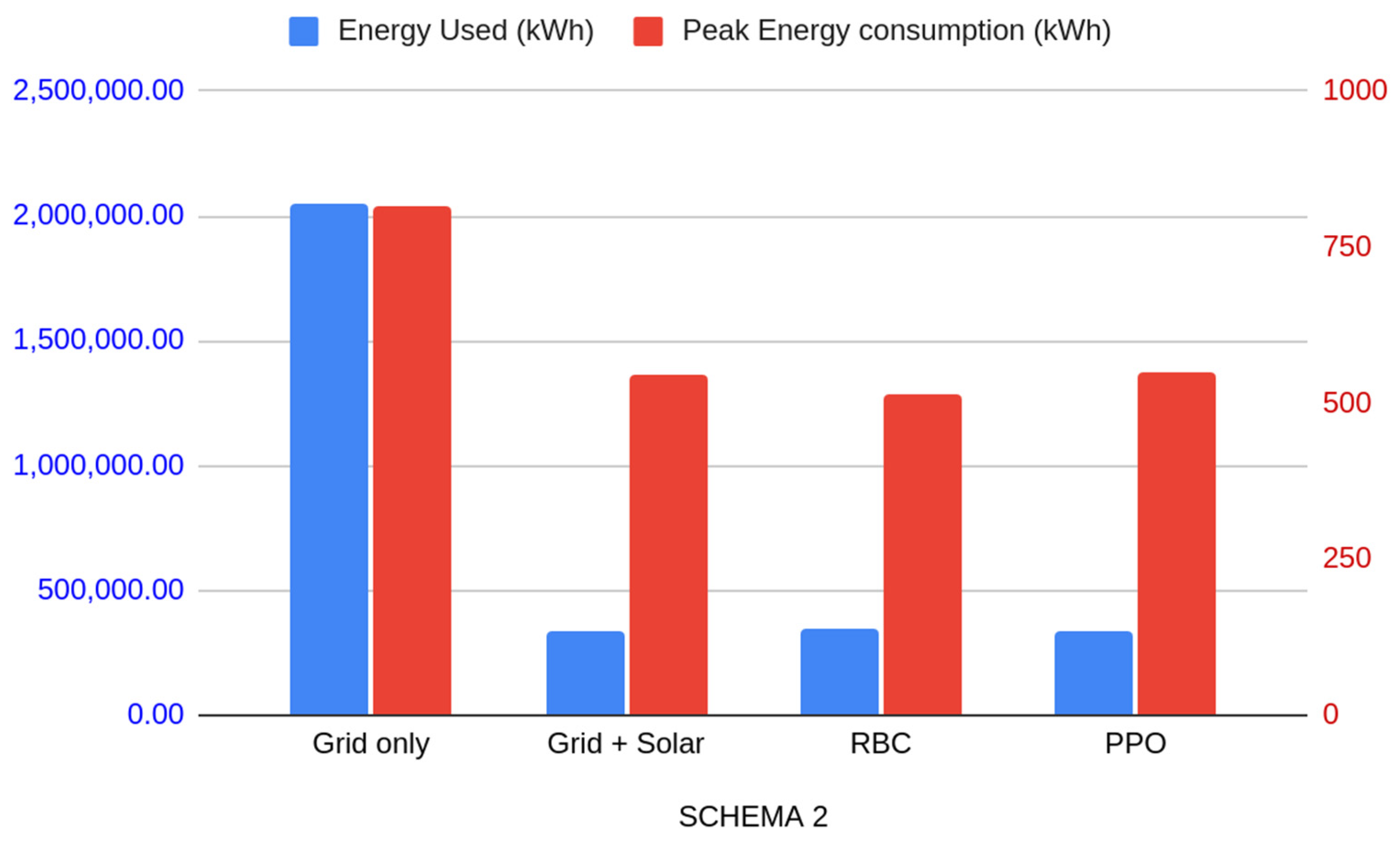

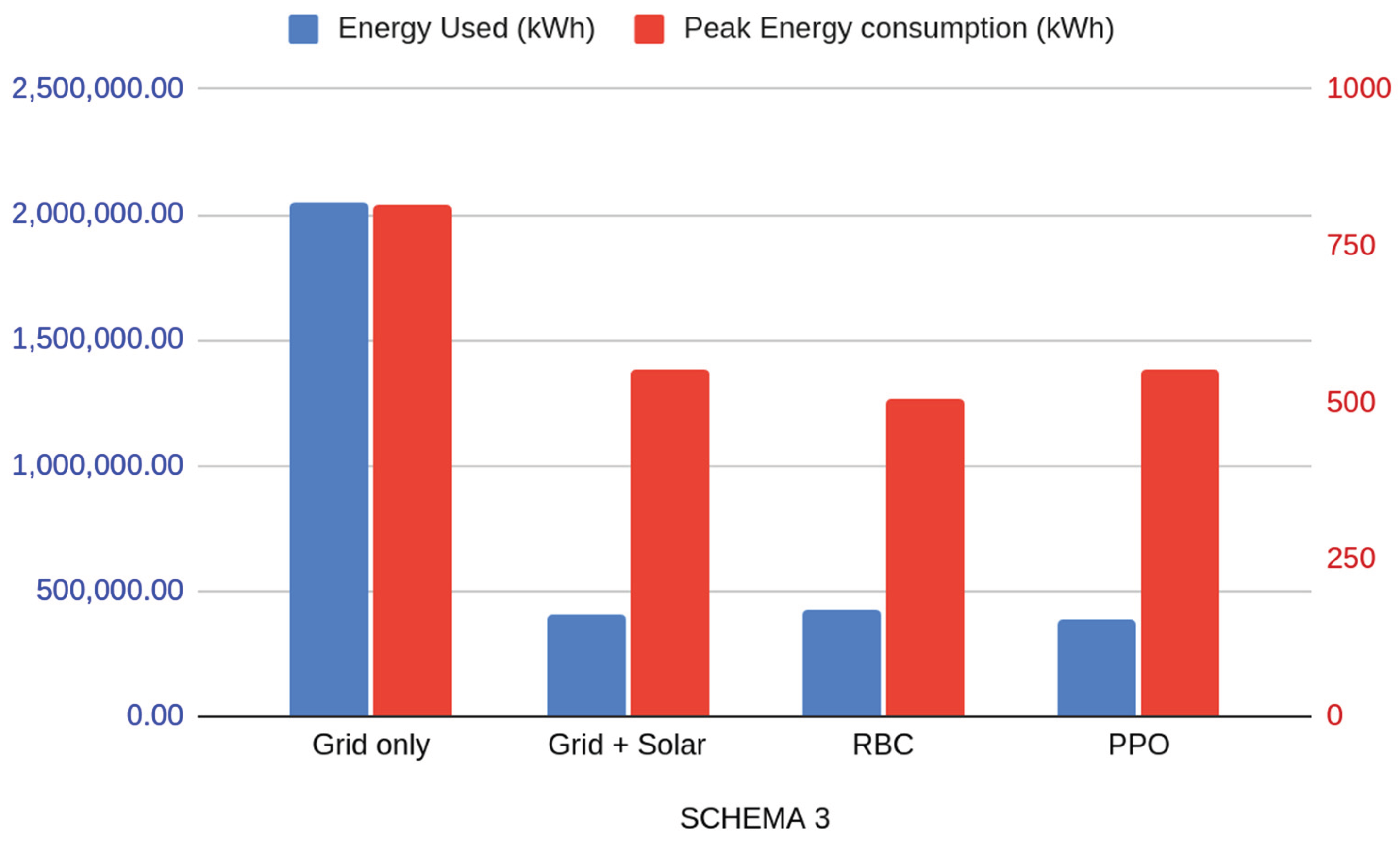

For each of our experimental setups four scenarios were considered in order to minimize the impact of each change. A grid-only scenario was used to show the raw energy needs of the community. A second scenario was a community which has access to solar panels but no control strategies, representing a passive system where buildings consume energy from the local PV and the remaining demand is supplied by the grid, which we used as a baseline to test control strategies against each other. The remaining two scenarios represent the same community with access to PV, storage capabilities, and two control strategies, a RBC and a PPO agent, respectively.

The performance of the control strategies is measured based on economic, stability, and environmental factors. We focus on the total amount of energy used, its cost, the amount of carbon emissions generated, and the peak energy consumption at the end of a one-year simulation period. All economic indicators in this study refer strictly to electricity costs from energy consumption, not accounting for installation of hardware investment costs. All percentage improvements reported below are computed relative to the corresponding baseline within the same schema, using the formula:

where

is the baseline value, and

is the value we compare with.

As expected in all situations, simply adding solar energy to the community greatly diminishes economic, and environmental impacts. When compared to the “Grid-only” baseline, the “Grid + Solar” configuration reduced annual costs by 72.4%, 87.2% and 84.7%, and reduced the amount of carbon emissions by 62.4%, 82.9%, and 79.5% in each schema respectively.

The improvements depend on how many resources the RL agent is able to control. For Schema 1, the agent can control 3 out of 5 buildings, since only 3 buildings in the community had batteries. When compared to the

“Grid + Solar” scenario, the PPO-controlled community achieved a 2.5% reduction in annual costs and carbon emissions (see

Table 6,

Figure 9), while the RBC-controlled community performed 1.9% worse. This demonstrates that an improper control strategy can degrade performance in certain conditions. Overall, the PPO agent was able to lower energy consumption and carbon footprint by 4.4% more than the RBC (calculated relative to the common

“Grid + Solar” reference).

For schema 2, even though the agent had control over 2 out of 3 buildings, most of the energy available for the community is produced by the largest entity, which the agent cannot control. We see that in this case, none of the controllers could provide better performance than the

“Grid + Solar” scenario. The PPO-controlled community achieved a 1.28% higher power consumption, and the RBC-controlled community achieved a 3.96% higher energy consumption. In such communities investing in any form of control system only brings the local distribution system operator (DSO) the advantage of a lower peak power consumption (see

Table 7,

Figure 10). While PPO remains superior to RBC in cost and carbon footprint reduction, the best solution in this case would be to go with a simpler system, of just using the power generated by the PV without storing anything.

In Schema 3, where all actors in the community had energy storage options, and the PPO agent was able to manage resources, we see a similar result to Schema 1. When comparing a scenario in which the PPO agent controls resources against a

“Grid + Solar” baseline, we see a 4.3% reduction in costs and carbon emissions, and a 9.2% performance difference between PPO control and RBC control (see

Table 8,

Figure 11) (when comparing both against the

“Grid + Solar” baseline).

One disadvantage of the PPO-controlled community is that given the current configuration and implementation it consistently registers higher peak power consumption due to the nature of the reward function, which does not punish the agent for reaching high power peaks.

5. Discussion

Results show that while simply integrating solar energy is highly effective, the choice of a control strategy can further improve economic and environmental outcomes. The choice of control strategy should depend on the layout of the energy community and its complexity. Reinforcement Learning is best suited for variable environments with controllable resources and rule-based approaches are more efficient in simpler or less flexible systems. The PPO agent consistently showed better performance for minimizing costs and carbon emissions compared to the RBC in the scenarios, provided it had enough control over the communities’ resources.

While the PPO agent is superior when it comes to resource optimization, one notable advantage of the RBC over the PPO agent is peak energy consumption. The RBC shows a clear advantage when it comes to reducing the peak power consumption, a metric of the grid stability. Schema 3, slightly different from schema 2, shows the advantage of providing control to a RL agent. Only by adding a battery to the third entity helps the RL agent make more impactful decisions, thus improving the overall performance against the baseline.

This research was conducted in the CityLearn framework, which has its limitations. While the framework provides a robust environment for simulating energy communities, it doesn’t support more advanced concepts, like peer-to-peer energy trading or the role of energy aggregators. It does not provide specific electrical characteristics such as nominal voltage or current for the battery models either. This is a limitation of the simulation and was not a parameter considered in this study. The nominal power and capacity values for the PV panels and batteries were not arbitrarily chosen, they were specifically taken from one of the CityLearn Challenge datasets, which are designed to model realistic community configurations. These datasets leverage real-world data from sources like the End-Use Load Profiles for the U.S. Building Stock to create their scenarios [

20].

6. Conclusions

This study analyzed the effectiveness of using a PPO reinforcement learning agent for energy management in three energy communities’ configurations, comparing it to a more traditional Rule-Based approach. Results show that the effectiveness of the PPO agent was directly linked to the degree of control it had over the available resources.

Across three community schemas, adding photovoltaic generation alone reduced annual operational costs by 72-87% and carbon emissions by 62-83% relative to grid-only operation. When storage and control were introduced, the PPO agent achieved up to 4.3% additional reductions of costs and carbon emissions when compared to a “Grid + Solar” baseline, and a 4-9% improvement over the rule-based controller. These results indicate that RL agent control strategies are advantageous in communities where the participants are prosumers, or a mixed community, where multiple buildings are equipped with photovoltaic generation and battery storage. In these configurations, the PPO agent can coordinate charging and discharging decisions, adapting to variables in the environment to minimize overall costs, whereas rule-based controllers may still be preferable in communities with a predictable energy dynamic, like commercial or industrial sites.

Future development will focus on methods for expanding the PPO agent’s control, by introducing new systems to the CityLearn framework. Implementation of an optimization algorithm based on Pareto non-dominance (e.g., NSGA-II, NSGA-III, CNSGA-II) to generate feasible offline or semi-online control and energy transfer strategies followed by implementation and testing of the resulting reward structures will represent a further step to follow in our research. Systems like Peer-To-Peer energy sharing and third-party energy aggregators could allow the Reinforcement Learning agent to explore more complex decisions and potentially achieve better results. Grid stability and peak energy consumption analysis also represent future focus points, given the framework’s built-in power outage scenarios, the computational capabilities for complex reward functions.

| 1 |

Taken from building 1, schema 1, 1st of July. |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

Information describing the current state of the environment, this can be current demand, solar generation, electricity prices, etc. |

| 4 |

A value in the range [−1, 1], which determines whether to charge, discharge or remain idle. |

| 5 |

A numeric value given by the reward function which helps guide the RL agent’s learning process. |

| 6 |

|

References

- I.-H. Chung, “Exploring the economic benefits and stability of renewable energy microgrids with controllable power sources under carbon fee and random outage scenarios,” Energy Rep., vol. 13, pp. 6017–6041, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. Rego, R. Castro, and J. Lagarto, “Sustainable energy trading and fair benefit allocation in renewable energy communities: A simulation model for Portugal,” Util. Policy, vol. 96, p. 101986, Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Sarker, H. Shafei, L. Li, R. P. Aguilera, M. J. Hossain, and S. M. Muyeen, “Advancing microgrid cyber resilience: Fundamentals, trends and case study on data-driven practices,” Appl. Energy, vol. 401, p. 126753, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Hamidieh and M. Ghassemi, “Microgrids and Resilience: A Review,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 106059–106080, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, Y. Chen, Z. Li, and S. Golshannavaz, “Robust Co-planning of distributed photovoltaics and energy storage for enhancing the hosting capacity of active distribution networks,” Renew. Energy, vol. 253, p. 123645, Nov. 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, P. Zhao, H. Qu, N. Liu, K. Zhao, and C. Xiao, “Optimal Placement and Sizing of Distributed PV-Storage in Distribution Networks Using Cluster-Based Partitioning,” Processes, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 1765, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Cui, S. Xu, J. Fang, X. Ai, and J. Wen, “A novel stable grand coalition for transactive multi-energy management in an integrated energy system,” Appl. Energy, vol. 394, p. 126155, Sept. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Hussain, M. Imran Azim, C. Lai, and U. Eicker, “Smart home integration and distribution network optimization through transactive energy framework – a review,” Appl. Energy, vol. 395, p. 126193, Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Nepal, N. Yuangyai, S. Gyawali, and C. Yuangyai, “Blockchain-Based Smart Renewable Energy: Review of Operational and Transactional Challenges,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 13, p. 4911, July 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Singh, R. Seshu Kumar, M. Bajaj, B. Hemanth Kumar, V. Blazek, and L. Prokop, “A blockchain-enabled multi-agent deep reinforcement learning framework for real-time demand response in renewable energy grids,” Energy Strategy Rev., vol. 62, p. 101905, Nov. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ye, Y. Tang, H. Wang, X.-P. Zhang, and G. Strbac, “A Scalable Privacy-Preserving Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach for Large-Scale Peer-to-Peer Transactive Energy Trading,” IEEE Trans. Smart Grid, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 5185–5200, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhang, F. Eliassen, A. Taherkordi, H.-A. Jacobsen, H.-M. Chung, and Y. Zhang, “Energy Trading with Demand Response in a Community-based P2P Energy Market,” in 2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (SmartGridComm), Beijing, China: IEEE, Oct. 2019, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, J. Wu, C. Long, and W. Ming, “State-of-the-Art Analysis and Perspectives for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading,” Engineering, vol. 6, no. 7, pp. 739–753, July 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. François-Lavet, D. Taralla, D. Ernst, and R. Fonteneau, “Deep Reinforcement Learning Solutions for Energy Microgrids Management”.

- J. R. Vázquez-Canteli and Z. Nagy, “Reinforcement learning for demand response: A review of algorithms and modeling techniques,” Appl. Energy, vol. 235, pp. 1072–1089, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- O. Pisacane, M. Severini, M. Fagiani, and S. Squartini, “Collaborative energy management in a micro-grid by multi-objective mathematical programming,” Energy Build., vol. 203, p. 109432, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Gellert, U. Fiore, A. Florea, R. Chis, and F. Palmieri, “Forecasting Electricity Consumption and Production in Smart Homes through Statistical Methods,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 76, p. 103426, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Shirinshahrakfard, A. Suratgar, M. Menhaj, and G. B. Gharehpetian, Multi-Objective Optimization of Peer-to-Peer Transactions in Arizona State University’s Microgrid by NSGA II. 2024, p. 5. [CrossRef]

- L. Kharatovi, R. Gantassi, Z. Masood, and Y. Choi, “A Multi-Objective Optimization Framework for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading in South Korea’s Tiered Pricing System,” Appl. Sci., vol. 14, no. 23, p. 11071, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Nweye et al.., “CityLearn v2: Energy-flexible, resilient, occupant-centric, and carbon-aware management of grid-interactive communities,” J. Build. Perform. Simul., vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 17–38, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Vazquez-Canteli, S. Dey, G. Henze, and Z. Nagy, “CityLearn: Standardizing Research in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Demand Response and Urban Energy Management,” Dec. 18, 2020, arXiv: arXiv:2012.10504. [CrossRef]

- Z. Nagy, J. Vázquez-Canteli, and S. Dey, The citylearn challenge 2021. 2021, p. 219. [CrossRef]

- A. Rizki, A. Touil, A. Echchatbi, R. Oucheikh, and M. Ahlaqqach, “A Reinforcement Learning-Based Proximal Policy Optimization Approach to Solve the Economic Dispatch Problem,” Eng. Proc., vol. 97, no. 1, p. 24, 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).