1. Introduction

The underground infrastructure network is primarily composed of sewer and water pipelines that form the backbone of municipal utilities. The United States has approximately 1.2 million miles of water supply mains, and for every mile of interstate highway, there is an equivalent mile of sewer pipes [

1,

2]. Over time, these systems become vulnerable to structural failure, blockage, and overflow [

3]. As stated by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), around

$271 billion will be required over the next 25 years to repair and replace aging underground infrastructure, which poses one of the greatest challenges encountered by modern cities [

4]. In the United States, pipelines are confronting a critical crisis due to population growth and inadequate attention to renewal and maintenance planning, highlighting the urgent need for the rehabilitation of these systems [

5]. Significant environmental impacts and emissions are associated with pipeline activities, including material production, transportation, installation equipment, and operation and maintenance processes [

6]. Historically, only the open-cut method was used to replace and renew the defective pipelines. This technique requires excavating the ground to expose the burned pipe, which poses several problems, especially in densely populated urban environments.

In contrast, trenchless technology methods, introduced in the 1980s, were developed to reduce or eliminate adverse impacts [

7]. The process of trenchless technology involves replacing or installing new pipes in place of the failed ones with minimal excavation and reduced disruption to the surface and subsurface area. One of the most widely used trenchless technology methods is Cured-in-Place Pipe (CIPP), which was introduced in the 1970s as a construction technique for replacing damaged pipes without excavation and was proposed as an alternative to the open-cut method. CIPP reduces social and environmental impacts, extends the lifespan of the pipeline, lowers operation and maintenance costs, enhances productivity and worker safety, and decreases overall project expenses. Since then, CIPP has become one of the most popular methods of trenchless technology used in several applications, including storm and sanitary sewers, potable water pipelines, and industrial pipelines. Because of its high flexibility, CIPP is adaptable to different pipe shapes, such as straight, curved sections, varied cross sections, lateral, and misaligned pipelines [

8,

9]. However, choosing CIPP as a renewal method for a particular project is associated with many variables that should be considered. These variables include the availability of space, the chemical characteristics of the fluid carried by the pipeline, the number of manholes and service laterals, the installation length, and the structural condition of the damaging pipe [

10]. The two primary components of the CIPP system are thermosetting resin materials and a flexible fabric tube. The resin provides the structural integrity when it is cured, forming a new pipe inside the existing pipe. The most commonly used are polyester, epoxy, or vinyl ester in CIPP applications due to their excellent installation property, strong chemical resistance, and economic advantages. For more than four decades, they have remained the dominant choice. On the other hand, the fabric tube, usually made from polyester or fiberglass, serves as a carrier for the resin and ensures uniform thickness throughout the length of the pipe [

11].

CIPP is a plastic liner that is produced inside the existing damaged pipes during the rehabilitation process. This method requires only a small area for construction; thus, roadway shutdown can be avoided, and the rehabilitated pipe can be back in service within a few hours. The process involves inserting a flexible uncured resin tube made from chemical materials like felt, plastic films, fillers, and reinforcement layers into the existing pipe using hydrostatic or air inversion, or by mechanically pulling and inflating it. Styrene-based polyester and vinyl ester resins are cheaper than other resins; therefore, the majority of CIPPs have used these two resins in the United States. On the other hand, non-styrene resins are more expensive; therefore, they have been used less. After inserting the tube in the host pipe, the curing liner starts by using hot water, steam, or ultraviolet light. However, during the CIPP installation process, ambient and indoor air contamination incidents have been observed by individuals working near CIPP sites [

12]. Ra et al. [

13] reported that more than 100 air contamination incidents were linked to CIPP manufacturing sites.

In the past, several studies of CIPP chemical air monitoring have been conducted to measure the emissions released during the CIPP installation process. However, the focus of these studies was on the air of residential homes directly connected to the sanitary sewers during the renewal. In contrast, less research has investigated the implications of Volatile Organic Components (VOCs) on the health and safety of workers and the general public [

14]. VOCs pose a significant concern for the environment and public health due to their toxicity and potential to cause acute and chronic health effects. Therefore, avoiding exposure is essential during the construction process because short-term exposure may lead to symptoms such as headache, dizziness, confusion, eye and nasal irritation, and difficulty breathing. In contrast, prolonged exposure has been associated with more severe health effects, including kidney and liver damage and central nervous system disorders. Therefore, the need for this research arises from the potential health hazards associated with VOCs released during the CIPP curing [

15].

In the literature, there are some investigations focused on the chemical emissions and worker exposure occurring during the CIPP for rehabilitating sanitary sewer and stormwater pipe networks. A study by Matthews et al. [

16] identified styrene as the primary chemical concern in the CIPP process, among other VOCs. They indicated that concentrations obtained from field observations and modeling analysis could pose potential health risks. However, due to the methodological limitations in existing studies, workers' and public exposure to styrene remains insufficiently understood. Also, in 2023, Matthew et al. [

17] conducted another research revealing that most coatings used in water and steam-cured CIPP installation liners allow styrene to leak through within a week or less. On the other hand, Abbas et al. [

8] conducted a study to measure the styrene emission. The research reported that the highest styrene concentrations were found at the liner truck openings and above the termination maintenance hole during the CIPP curing process.

Ra et al. [

11] investigated the VOCs emitted from storm sewer pipe installation at different locations. The study highlighted increasing concerns regarding VOCs, mainly styrene emissions, for CIPP installation because of their potential health and environmental risks. When the resin starts curing, which involves elevated temperatures and chemical reactions, the VOCs are released to the surrounding area. Several air contamination incidents have been associated with CIPP manufacturing sites; however, there remains a lack of information about chemicals emitted and the implications on the environment and health. The California Department of Public Health also reported that more than 130 exposure incidents occurred with CIPP installations. These incidents raise concerns about the migration of VOCs into adjacent buildings through openings such as doors and windows, which may cause potential health hazards to building occupants. Many factors affect the migration of vapors to the nearby buildings, such as soil type, surface conditions, project size, and building structure [

12].

A study conducted by Ajdari [

18] observed VOC emissions during the installation of three CIPP sewer liners. The vacuum bag samplers were utilized to collect air samples. The research outcome revealed that styrene levels exceeded occupational exposure limits during the hot steam curing process, when all measurements were taken approximately 25.4 cm inside the maintenance hole. Other VOCs were not detected at measurable quantities. Sendesi et al. [

19] conducted a comprehensive investigation of volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions released during the CIPP installation process. Their findings revealed that styrene concentrations in the air were notably high, often obscuring the detection of other VOCs. The study also emphasized that factors such as site location, wind direction, and worksite activities significantly influence the magnitude of emissions. More recent research further estimated that a single CIPP installation could emit several tons of VOCs during the curing phase. These results underscore the potential health risks to workers and nearby residents, highlighting the urgent need for rigorous monitoring and effective mitigation strategies.

Najafi et al. [

9] conducted a comprehensive review of CIPP emissions revealed significant methodological deficiencies in previous studies, and the authors highlighted the need for developing standardized approaches to evaluate and manage VOC emissions. In recent research regarding the steam-cured of the CIPP installations, several essential findings concerning VOCs, especially styrene emissions. Firstly, styrene is commonly detected at CIPP sites and is considered a compound of concern because of its associated health risk. Secondly, photoionization detectors (PIDs), which are used for real-time air monitoring, have proven essential for supporting on-site decision making and enhancing worker safety through immediate detection of VOCs. Thirdly, although workers’ overall daily exposure to styrene seems safe, there are short moments during the CIPP installation when styrene levels can get dangerously high, which could be above the safety limit; therefore, more studies are needed to protect the workers and the public [

20].

The primary objectives of this study are to (1) quantify volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions generated during CIPP sewer pipe installations across different locations, resin types, and curing methods; (2) assess potential occupational health impact by comparing the measured VOC concentrations with established exposure limits defined by Occupational Safety and Health Administration OSHA, National Institutes for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; and (3) evaluate the dispersion behavior of VOC emissions to determine how concentrations vary with distance from the emission source.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Selection

In this study, six CIPP installations that employed different liners and curing methods were examined to assess emissions in varying field conditions. Both styrene-based and non-styrene vinyl ester resins were used in these installations. These installations also differed in terms of pipe length, diameter, and geographic location.

At Sites 1 and 2, the emissions monitoring was conducted in 2024 in Washington, D.C., USA. The host pipe was a 10-inch diameter vitrified clay pipe made of a blend of clay and shale, with a length of 327 linear feet, while the second liner measured 250 linear feet. Both installation liners were pulled into the damaged pipes and inflated by air pressure. Subsequently, the UV light-curing technology was applied to cure the non-styrene-based resin liners. Also, in 2024, in Washington, D.C., USA, the installation of Sites 3 and 4 was implemented. Both host pipes were also vitrified clay pipes with a 10-inch diameter; however, their length differed, measuring 241 linear feet at Site 3 and 261 linear feet at Site 4. A non-styrene-based resin liner was employed to rehabilitate the pipe. The liners were inserted into the existing pipe and inflated by water pressure to achieve a tight fit against the host pipe walls, followed by the hot water curing method.

At installations 5 and 6 in Texas, styrene-based resin liners were applied through the thermal curing method. In 2024, installation 5 was conducted in Forney, Texas, involving an 8-inch diameter host pipe that spanned 674 linear feet. The liner was inserted into the deteriorated pipe and inflated by using air pressure, followed by steam curing to achieve full polymerization of the resin. Finally, in 2023, installation 6, conducted in Garland, Texas, involved a substantially larger 48-inch-diameter host pipe with a total length of 1029 linear feet. The curing method was accomplished using hot water circulation in order to activate the styrene-based resin.

Table 1 provides an overview of the features of six CIPP installations, presenting details such as installation length, pipe diameter, year of installation, curing method, resin type, and project location.

2.2. Data Collection

In this research, two approaches were applied to capture the chemical air emissions. The first approach involved real-time monitoring of on-site measurements, using Photoionization Detectors (PIDs), while the second approach focused on laboratory analysis of air samples collected with Summa canisters and workers’ sorbent tubes.

In the real-time monitoring phase, Honeywell MiniRAE 3000 Photoionization Detectors (PIDs) were used to capture the VOC emissions. These devices are capable of measuring VOCs within a range of 0-99.9 ppm at a resolution of 0.1 ppm. Isobutylene gas was utilized to calibrate the PIDs as a surrogate standard, and chemical air emissions were determined by applying compound-specific conversion factors for each component. During the field monitoring process, three PIDs were employed: two units were used for continuous measurements, which were placed upwind and downwind of the insertion maintenance hole adjacent to the liner truck to collect data with an average of 15 minutes. The third handheld PID was used periodically, with an average of 30 minutes at key locations. These locations included 4 inches above the terminal discharge maintenance hole, five feet around the work zone, and at lateral connections. The PIDs were covered with water trap filters in order to reduce the effect of moisture, which was generated during the curing process.

On the other hand, laboratory analyses were conducted to determine the time-weighted average (TWA) concentrations of VOCs, using Summa canisters to collect the air samples. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA-TO-15), the samples were analyzed, applying gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to identify and quantify the emissions for each compound. In this research, the method detection limits were employed, which provides an accuracy of ±30% of the true concentration with a precision of ≤25% relative standard deviation. This method is reliable in both ambient and indoor air. The Summa canisters were positioned at different locations around the working area, including the upwind and downwind insertion maintenance hole, and also above the termination maintenance hole. This procedure was implemented in three phases: baseline, during the installations, and during the curing process. Worker samplings were also conducted at the job site during the CIPP installation process at each site. The two Radiello 130 (solvent) passive samplers were attached to the personnel working for an 8-hour shift. Both workers participated throughout the entire installation and curing process, including the opening of the liner truck and unloading the uncured liner, inserting the liner into the inlet maintenance hole for installation, and during the monitoring curing process. Passive worker samplers offer flexible sampling durations, including short-term (15-minute STEL) and long-term (8-hour TWA) monitoring, as well as extended sampling periods of up to 14 days. Laboratory analysis of each passive sampler was performed in accordance with a modified version of EPA Method 17. The chemical air emissions were extracted by using carbon disulfide.

Figure 1 illustrates all the devices that were used in the job sites.

2.3. Sampling Procedure

A comprehensive air sampling was conducted at all CIPP installation sites during different stages of the process. Before the construction began, baseline air sampling was collected in order to characterize the background air quality.

Figure 2 illustrates that the monitoring equipment was deployed at key locations, including the inlet, lateral, pass-through, and outlet manholes. At the insertion manhole, two canisters, two photoionization detectors (PIDs), and one worker sampler were used. Continuous monitoring was conducted from fixed upwind and downwind positions throughout installation. The outlet manhole was equipped with one canister and one worker sampler for an 8-hour sampling. During the curing phase, two additional canisters were placed on top of the inlet and outlet manholes, while TO-13 sorbent tubes were installed at both ends to capture VOC emissions. A handheld PID was also employed approximately every 30 minutes to measure concentrations near the lateral manhole, the liner transport truck, and the outlet manhole.

2.4. Exposure Limits

Air emissions are primarily characterized by the release of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), notably styrene, cumene, and acetophenone. Industrial activities and motor vehicle emissions represent the primary sources of styrene (CAS No. 100-42-8) in ambient air; however, cigarette smoking can also be a significant source of exposure [

21]. Styrene disappears quickly from water and evaporates easily; therefore, its amount in surface or groundwater is usually less than 1 microgram per liter or undetectable in most cases. This could indicate that styrene has limited persistence in aquatic environments but remains more active and mobile in the air. On the other hand, Acetophenone (CAS No. 98-86-2) is an aromatic volatile organic compound (VOC), and the industrial processes, fuel combustion, and motor vehicles are the main sources of this compound. The acetophenone exists primarily in vapor form in the atmosphere, degraded through reactions with hydroxyl radicals. Cumene (CAS No. 98-82-8) is an aromatic hydrocarbon classified as a volatile organic compound (VOC) commonly detected in both industrial and urban environments [

22].

During the Cured-in-place pipe, styrene is added to the resin in order to reduce the viscosity, which makes it easier to handle and evenly distribute inside the existing pipe. In addition, styrene plays a crucial role during the curing stage by promoting cross-linking between the molecular chains of the polyester resin, transforming it into a rigid and solid structure. This chemical reaction ensures that the proper mechanical strength and long-term performance of the rehabilitated pipe [

23].

The threshold exposure limits for styrene, cumene, and acetophenone have been established by three U.S. regulatory agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). These exposure limits are designed to address emissions issues and protect the workers and the public from the potential health effects of VOCs. OSHA specified that the permissible exposure limit (PEL) for styrene is 100 ppm as an 8-hour time-weighted average (TWA). On the other hand, NIOSH recommends a lower exposure limit of 50 ppm for styrene [

24,

25], and the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) specifies a threshold limit value of 20 ppm. ACGIH also recommends 10 ppm, as neither OSHA nor NIOSH has defined a specific limit for acetophenone. All these agencies, including OSHA, NIOSH, and ACGIH, specify that the exposure limit value of cumene is 50 ppm. Among other VOC standards, these limit values provide the basis for evaluations of occupational and environmental exposure risks during the CIPP installation and curing process.

EPA has also published Acute Exposure Limits Guideline Levels (AEGLs), establishing threshold exposure limits for hazardous materials in order to protect the environment and the general population. These guidelines are divided into three categories based on the severity of potential health effects [

26,

27,

28].

Table 2 displays the interesting VOCs that were analyzed in all summa canisters. These compounds can provide an overview of chemical emissions associated with CIPP processes and allow us to understand the potential environmental impact and health hazards to workers. There are lots of chemical compounds in the atmosphere, but the table shows only 63 chemical emissions, ranging from acetone to o-xylene. Therefore, the results are shown as values, and if the compounds are not mentioned in the upcoming tables, it means they are under detectable limits. Only the higher value of emissions among different locations of canisters will be selected for analysis. The correction factors were applied to the PID results to calculate the concentration of the existing emission.

4. Results and Discussion

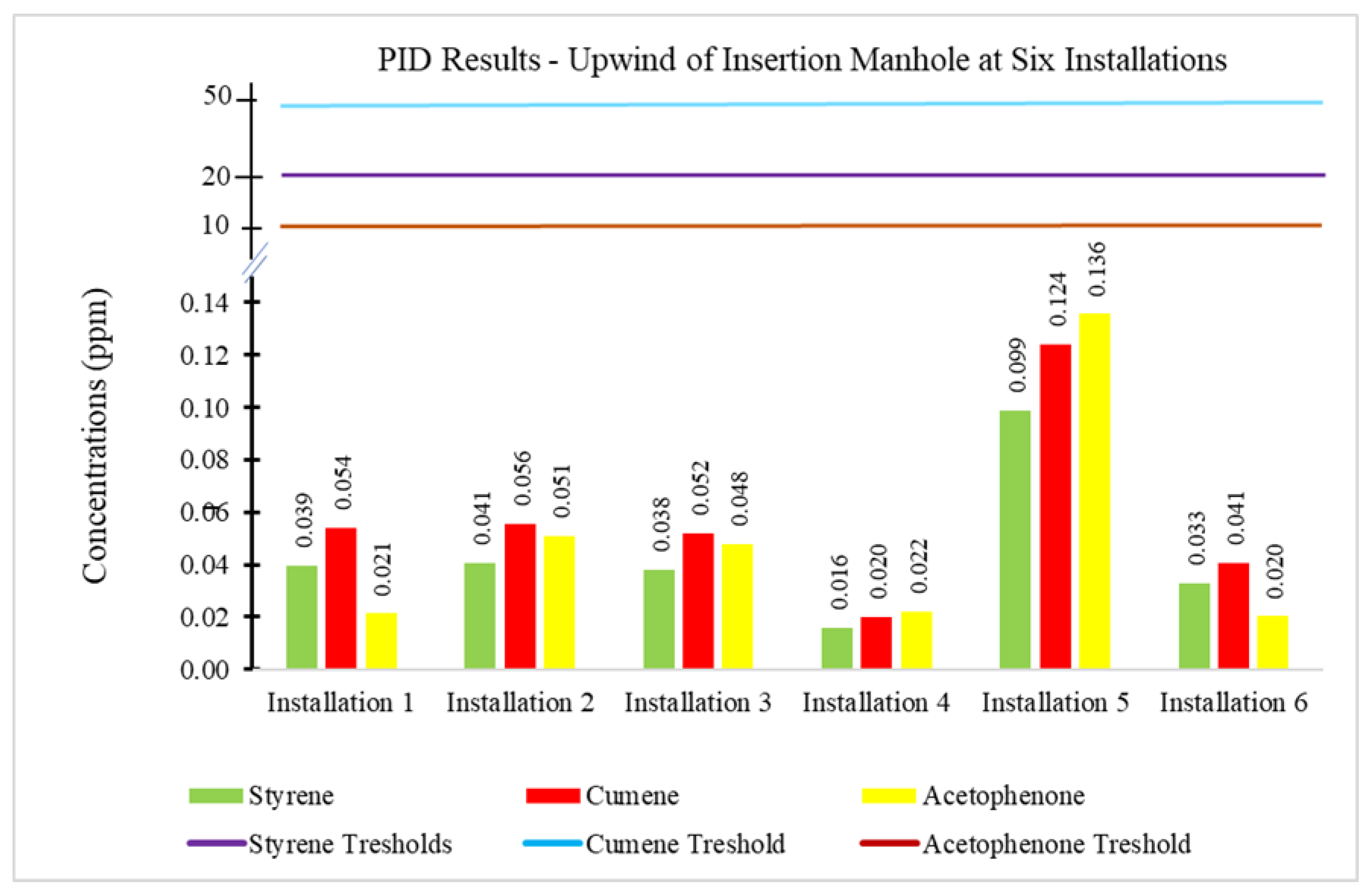

Figure 3 illustrates the photoionization detectors (PIDs) measurements obtained upwind and downwind of the insertion manhole at six CIPP installation sites. The concentrations of styrene, cumene, and acetophenone, measured in parts per million, were evaluated against their respective occupational exposure thresholds defined by regulatory agencies such as OSHA, NIOSH, and ACGIH. Across all installation sites, the measured concentrations of monitored VOCs remained the corresponding threshold limits, indicating negligible background VOC levels in the upwind air during the CIPP process. Among the captured compounds, cumene exhibited slightly higher upwind concentrations compared to styrene and acetophenone, although all values remained below 0.15 ppm. The highest readings were recorded at Installation 5, where styrene (0.099 ppm), cumene (0.124 ppm), and acetophenone (0.136 ppm) reached the peak values, which may be affected by local weather or operational factors. Installations at sites 1 through 3 showed moderate but consistent concentrations in the range of 0.038–0.056 ppm, while Installation 4 recorded the lowest emissions, indicating minimal upwind dispersion of curing-related vapors at that site. In

Figure 3, the horizontal lines represent the regulatory threshold limits for each compound: 20 ppm for styrene, 50 ppm for cumene, and 10 ppm for acetophenone. The thresholds emphasize that the recorded concentrations are several orders of magnitude below occupational exposure limits. As a result, upwind positions were not significantly affected by CIPP emissions during the sampling periods.

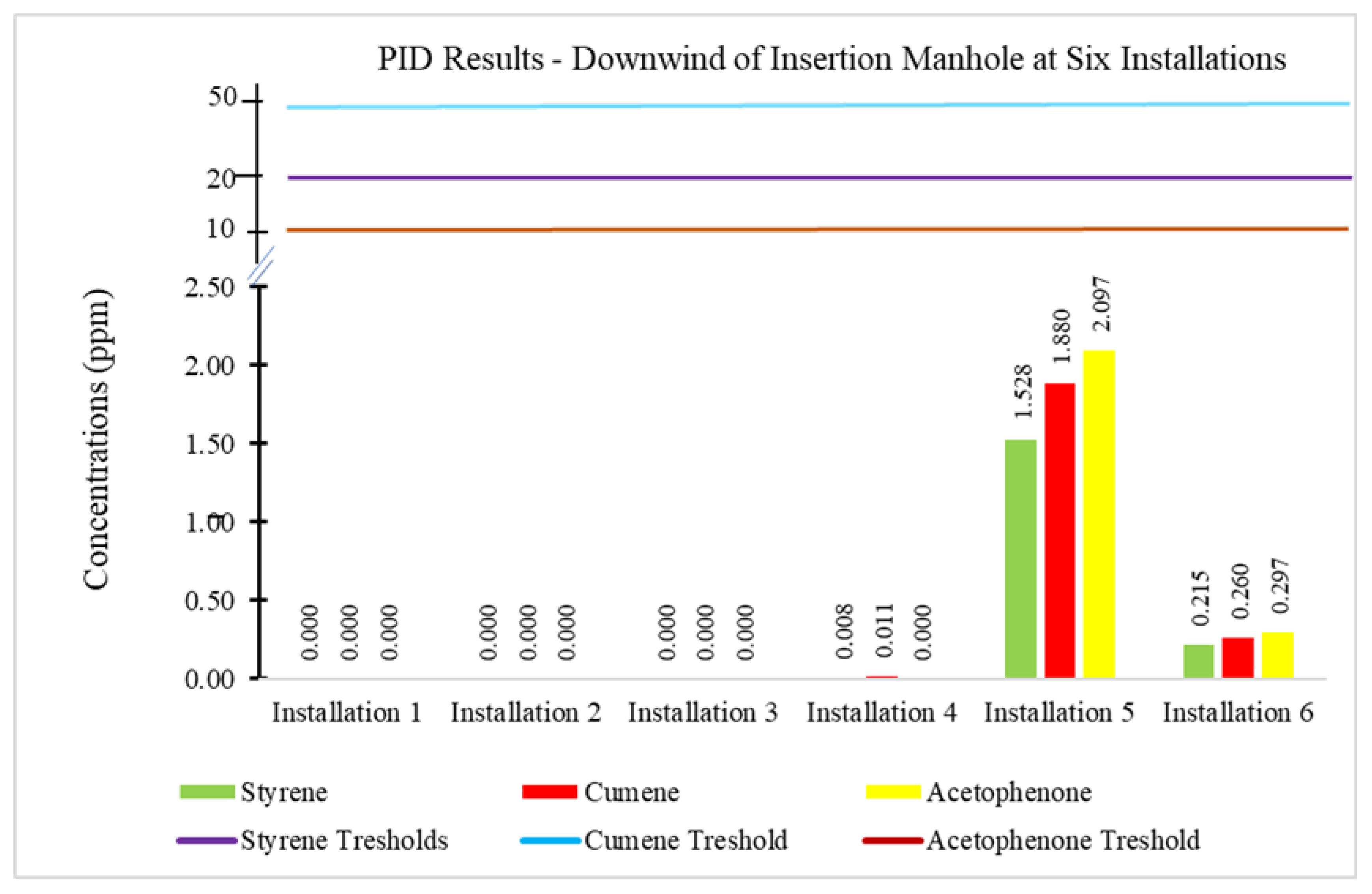

The PID results for VOC concentrations, as shown in

Figure 4, measured downwind of the insertion manhole at six installations, show a distinct pattern in comparison to the upwind measurements. Installations 1 through 4 recorded negligible concentrations for styrene, cumene, and acetophenone, with all values at or near 0.000 ppm, indicating that no significant VOC emissions were detected downwind at these locations. However, at Installations 5 and 6, there is a noticeable increase in VOC levels, though they remain well below the threshold limits. Installation 5 shows the highest concentrations, with acetophenone reaching 2.097 ppm, cumene at 1.880 ppm, and styrene at 1.528 ppm. These values, while higher than those measured upwind, still fall significantly below their respective safety thresholds (20 ppm for styrene, 50 ppm for cumene, and 10 ppm for acetophenone), suggesting that the air quality, even downwind, remains within safe exposure limits. Installation 6 also shows elevated levels compared to the other sites, with acetophenone at 0.297 ppm, cumene at 0.260 ppm, and styrene at 0.215 ppm. This increase, particularly at Installations 5 and 6, may indicate localized VOC emissions likely related to activities or conditions specific to these sites.

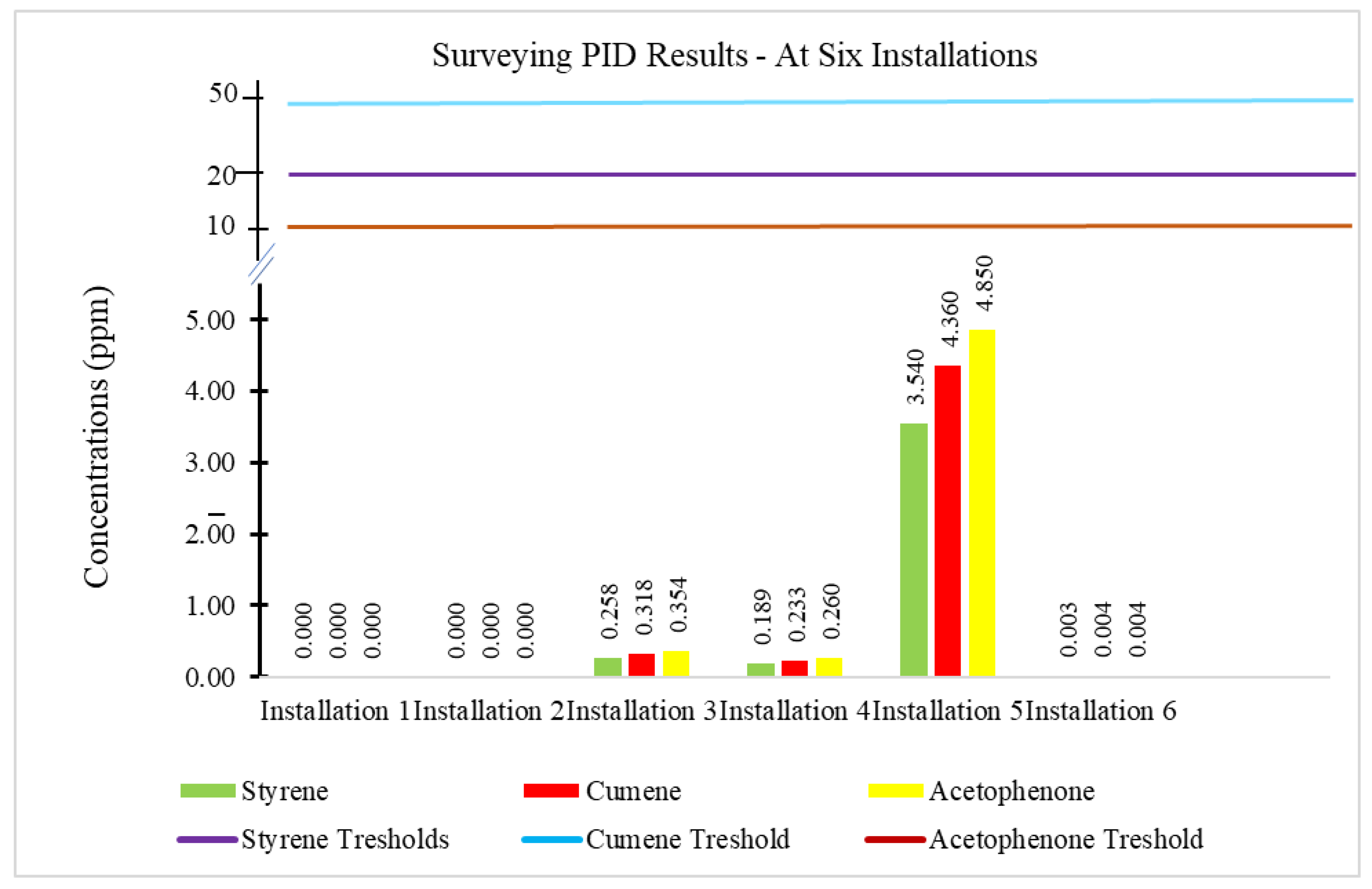

Figure 5 presents the surveying PID monitoring results of air emissions collected downwind insertion manhole. The graph illustrates the concentration (in ppm) of styrene, cumene, and acetophenone detected in ambient air against their respective regulatory threshold limits established by OSHA, NIOSH, and ACGIH. The results reveal a clear spatial difference between downwind and upwind measurements. While no detectable concentrations were recorded at Installations 1-3, small traces were identified at Installation 4 (styrene: 0.008 ppm; cumene: 0.011 ppm), which indicates limited dispersion of VOCs at that site. On the other hand, Installations 5 and 6 revealed significantly elevated VOC levels. As a result, these findings indicate stronger downwind transport of curing-related emissions from the CIPP process, likely exacerbated by thermal curing and the use of styrene-based resins. These factors likely increased the potential for VOC dispersion at the site. Similarly, Installation 6 revealed moderately elevated readings of VOCs (styrene: 0.215 ppm; cumene: 0.260 ppm; acetophenone: 0.297 ppm). Although these findings were lower than those captured in Installation 5, they indicate continued chemical migration in the downwind direction, which could be related to the curing process.

All recorded emissions remain well below the occupational exposure threshold limit, even though they slightly increase as shown by the horizontal lines in

Figure 5. As a result, the concentrations did not approach the regulatory concern levels. Overall, the figure demonstrates that wind direction plays a crucial role in influencing the spatial distribution of airborne VOCs released during CIPP installation, highlighting the importance of downwind monitoring to capture peak emission exposure conditions.

Table 3 presents a comparison of the VOC concentrations for six CIPP liner installations that were conducted by using sorbent tube worker samples at six locations. As mentioned in Chapter Three, two worker samples were used for an 8-hour working shift during the CIPP liner installations and curing processes. emissions of styrene, hexane, toluene, ethanol, and m&p-Xylenes detected during the lining and curing CIPP process, and different implications for air pollution, safety, and environmental health are associated with each compound.

Styrene emissions were highly variable across the six installations, with a range of 0 to 13.85 ppm. The styrene emitted from CIPP liner installations 1, 2, 3, and 4 was either negligible or low compared to installations 5 and 6. This is because non-styrene-based resins were applied to rehabilitate the damaged pipe in liner installations 1, 2, 3, and 4. In contrast, the concentrations of styrene for locations 5 and 6 were 8.22 and 13.85 ppm, respectively. The styrene level in installation 6 exceeded the threshold, which could indicate that the styrene-based resin used in these installations needs to be inspected closely to better understand the impacts that it could have on workers and nearby residents, as styrene is a recognized hazardous air pollutant.

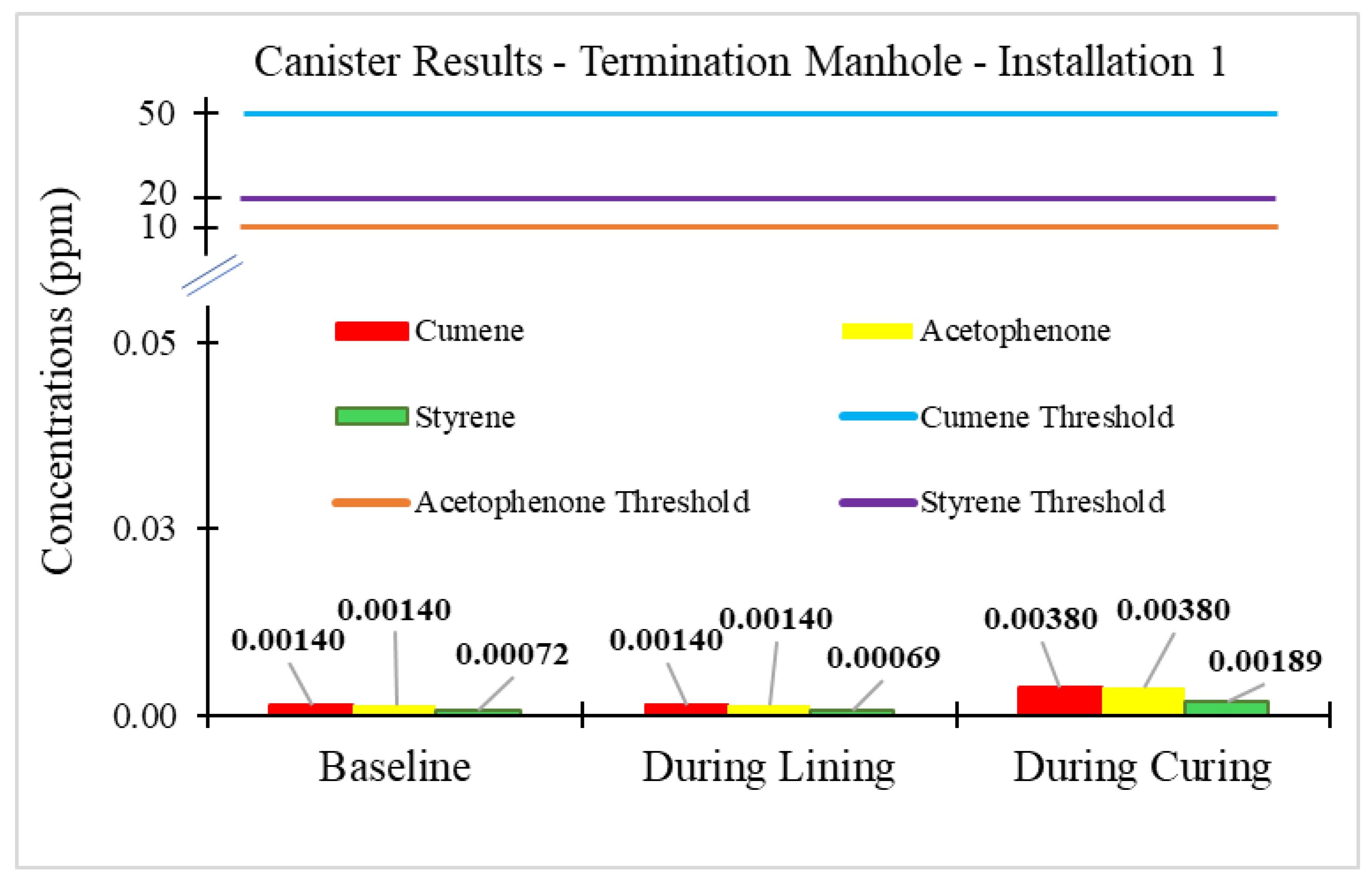

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show a comparison of styrene, acetophenone, and cumene emissions for upwind and downwind of the insertion manhole and termination manhole during different phases of the CIPP installations. The periods include baseline, lining, and curing for Installation 1. The baseline measurements were taken one day before the CIPP installation process to compare the air quality in the surrounding area during and after the CIPP installation. In the baseline stage, the following figures revealed that the concentrations of cumene, acetophenone, and styrene were not detected, which means that results listed as 'ND' were not detected at or above the listed practical quantitation limit (PQL). The PQLs for cumene and acetophenone were 0.0014 ppm, however, for the styrene were 0.00072 ppm, respectively. This explains that the presence of these compounds had low levels in the environment, causing no significant health or environmental risk in the zone area. During the CIPP lining process, concentrations of acetophenone, cumene, and styrene were not detected, with PQL values of 0.0014 ppm for acetophenone and cumene, and 0.00063 ppm for styrene. The stability of these VOC levels is significant, indicating that the lining phase at Installation 1 did not increase emissions. Similarly, during the curing phase, VOCs were either undetected or below the PQL, with cumene and acetophenone at 0.0038 ppm, and styrene at 0.00189 ppm in the termination manhole and 0.00218 ppm at both the upwind and downwind manholes. Consequently, the results fall below the threshold limits, indicating that these emissions do not pose a health hazard. In Installations 1 and 2, styrene-free resins and UV light curing were used, so they have less impact on workers and the environment. In Installations 3, 4, 5, and 6, higher concentration levels of VOC emissions occurred during the curing phases compared to the released emissions during the lining phase or baseline.

Table 4 presents the measured VOCs, including styrene, cumene, and acetophenone, across six site installations, and compares them with 8-hour occupational exposure limits of 20 ppm, 50 ppm, and 10 ppm, respectively. The outcome reveals that VOCs varied notably between the site installations, mainly for styrene. The results of cumene and acetophenone revealed that these emissions stayed at very low levels across all locations. Styrene concentration was at a low level in all locations 1-5, meaning there was little chemical exposure during the installation. Installation 6 had a much higher level of styrene, 25.5 ppm, which passed the exposure limit of 20 ppm. This indicates that workers could have a higher exposure risk at site 6.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study examined air emissions across different site conditions, focusing on the rehabilitation of aging underground sewer systems that have been in service for over ages. The cured-in-place pipe (CIPP) trenchless method offers significant advantages over the open-cut approach, particularly in minimizing surface disruption and reducing overall costs. However, growing environmental and occupational health concerns have emerged regarding worker safety and potential public exposure to chemical emissions.

Through both field and theoretical investigations at six CIPP installation sites employing different resins and curing methods, the research details the assessment of volatile organic compound emissions associated with the CIPP process. The photoionization detectors (PIDs), SUMMA canisters, and worker exposure samples were used to collect data regarding VOCs, including styrene, cumene, acetophenone, hexane, and other compounds. Then, results were analyzed and compared against regulatory standards exposure limits established by OSHA, NIOSH, and ACGIH. The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of air quality impacts during CIPP installations and highlight the need for enhanced emission control strategies and standardized monitoring protocols to ensure worker safety and environmental protection.

The results of the study revealed that VOC emissions from CIPP installations varied across sites. Installations 5 and 6 exhibited higher concentrations of styrene, acetophenone, cumene, and other compounds that exceeded regulatory standards, indicating the need for careful selection and application of resins and curing methods due to their greater environmental and occupational impacts. In contrast, non-styrene-based resins and UV light curing methods produced notably lower VOC emissions, demonstrating their potential as safer and more sustainable alternatives. The elevated emissions observed at certain sites highlight the importance of further investigation and the implementation of safety measures to minimize worker exposure to hazardous levels of VOCs. Overall, the study confirms that factors such as liner type, resin composition, curing technique, and environmental conditions significantly influence emission levels. Therefore, understanding the interactions among these variables is essential for reducing emissions, enhancing worker safety, and promoting environmental sustainability in trenchless rehabilitation practices.