3.1. Characterisation of Organic Compounds in Indoor Air and Water-Based Varnishes

In the analysed samples of indoor air and water-based varnishes (polyurethane and acrylic-polyurethane), sixteen groups of organic compounds were identified. These included additives, degradation products, precursors, resin monomers (polyester, polyurethane, acrylic), contaminants, and secondary compounds formed through interactions between varnishes and wood. Additives represented a substantial fraction, fulfilling technological functions such as photoinitiators, antioxidants, UV stabilisers, plasticisers, drying agents, adhesion promoters, gloss enhancers, and antimicrobial agents. They were detected in indoor air either in their original form or as degradation and reaction products. Their presence and concentrations depended on the type of varnish, resin composition, and interactions with the underlying wood.

In the air inside the test chamber, three main groups of organic compounds dominated: aromatic hydrocarbons (37.40 ± 12.90%) > alcohols (23.64 ± 8.74%) > carboxylic acids, esters, and acetates (10.5 ± 2.90%). Water-based varnishes were a significant source of alcohols and esters, which are widely used as solvents and resin components (Wang et al., 2022). The wooden substrate also contributed to the overall burden of aromatic hydrocarbons (9–11%), with elevated emissions of toluene and 1,3-xylene from untreated wood reported by Wang et al. (2022).

Alcohols represented the second most abundant group. Their concentrations in emissions from PUR and ACR-PUR varnishes were comparable, reflecting their role as solvents in both systems. Carboxylic acids, esters, and acetates accounted for about 10% of the total. According to Alapieti et al. (Alapieti et al., 2021), coatings significantly alter the emission profile compared to bare wood, with esters and acetates becoming dominant during early drying stages. Their release is influenced by substrate moisture. These compounds typically occur at 11–20% in coating formulations as part of polyester and acrylic resins modified with polyurethane and serve as plasticisers and lubricants.

Cyclic alkenes, mainly terpenes and isoprenoids, were released naturally from raw wood. They are constituents of resins and essential oils, especially in coniferous species. However, when coatings such as polyurethane varnishes were applied, processes occurred that altered the volatility of these compounds (Liu et al., 2020). The varnish could dissolve wood constituents, enhancing their release, or promote chemical interactions between terpenes (e.g., α-pinene, limonene) and varnish components, which modified the final emission profile. Depending on the type of varnish, some VOCs were trapped in the coating layer, while others were more intensively emitted into indoor air.

Aldehydes and ketones originated from surface treatments, construction materials, and furniture, acting as secondary pollutants. Major sources included MDF, particle boards, laminates, and adhesives. Liu et al. (Liu et al., 2020) reported mean concentrations of aldehydes and ketones in 30 monitored indoor environments at 0.432 mg/m³, with the highest values for flooring (0.648 mg/m³), furniture (0.590 mg/m³), and coatings (0.341 mg/m³).

The total VOC concentration in the test chamber was 389.33 ± 30.96 µg/m³ during days 14–21 after coating application. For the evaluation of varnish impact on indoor air quality, only compounds of anthropogenic origin and with proven health risks were considered, while terpenes and isoprenoids were excluded. In total, 96 organic compounds with potentially toxic properties were identified, several of which have been associated with Sick Building Syndrome symptoms.

3.1.1. Reproductive Toxicants

Many substances with established reproductive toxicity were detected in indoor air following the application of PUR and ACR-PUR varnishes. These included phthalates such as bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), and diethyl phthalate (DEP), glycol ethers such as 2-ethoxyethanol (EGEE), solvents such as methyl butyl ketone (MBK/2-hexanone) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), as well as styrene, toluene, and 1-ethyl-2-methylbenzene.

Among these, DEHP was detected at 7.46 ± 5.01 µg/m³ in chamber air during days 14–21, while concentrations in the polyurethane varnish reached 62.66 ± 11.33 µg/m³. After 60 days, indoor levels dropped below the detection limit. DEHP is classified as a presumed human reproductive toxicant (Repr. 1B) and as a probable human carcinogen by the U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1988). Its toxicological profile includes disruption of thyroid hormone balance, reproductive organs, the liver, and the nervous system (Rowdhwal and Chen, 2018). Although DEHP itself is not considered a direct SBS-inducing compound, its degradation product 2-ethyl-1-hexanol has been repeatedly associated with SBS symptoms in buildings with PVC flooring (Wakayama et al., 2019).

DBP was present at 6.37 ± 2.09 µg/m³ in PUR and 1.94 ± 0.10 µg/m³ in ACR-PUR varnish. In indoor air, its concentration averaged 0.16 ± 0.14 µg/m³ during days 14–21 but decreased markedly to 0.03 ± 0.002 µg/m³ after 60 days. This rapid decline is consistent with its higher volatility and lower molecular weight compared to DEHP, which facilitates faster evaporation and weaker binding to the polymer matrix. Despite its faster loss, DBP is a recognised endocrine disruptor and has been shown to exacerbate allergen-induced lung function decline and alter airway immunology (Maestre-Batlle et al., 2020).

DEP, a less potent phthalate, was detected at 6.37 ± 2.09 µg/m³ in PUR and 1.94 ± 0.1 µg/m³ in ACR-PUR varnish. Chamber concentrations averaged 0.44 ± 0.15 µg/m³ during days 14–21 and declined to 3.1 ± 0.1 ng/m³ after 60 days (Wang et al., 2023). Despite lower toxicity, its presence illustrates that even regulated or phased-out plasticisers can contribute to indoor VOC burdens.

Solvents with reproductive toxicity were also present. MBK (2-hexanone) was measured at 9.59 ± 1.42 µg/m³ in PUR and 4.97 ± 0.14 µg/m³ in ACR-PUR varnish. Chamber concentrations were stable at 0.61 ± 0.14 µg/m³ during days 14–21 and 0.60 ± 0.15 µg/m³ after 60 days, demonstrating persistence due to intermediate volatility and reversible sorption–desorption processes. DMF, used as a solvent to improve diisocyanate solubility in PUR systems, was present at 31.16 ± 11.21 µg/m³ in ACR-PUR varnish and detected in chamber air at 0.22 ± 0.07 µg/m³ during days 14–21, but declined below the detection limit after 60 days. Its rapid loss reflects its high vapour pressure and susceptibility to hydrolysis and photodegradation.

Styrene and toluene, both common VOCs in varnishes and wooden composites, were also detected. Styrene reached 26.49 ± 1.20 µg/m³ in PUR and 188.65 ± 87.25 µg/m³ in ACR-PUR varnishes, while chamber air concentrations were 3.39 ± 1.22 µg/m³ during days 14–21 and 1.13 ± 0.017 µg/m³ after 60 days. Toluene exhibited extreme variability between formulations, with 2.45 ± 3.21 µg/m³ in PUR but as high as 816.65 ± 215.1 µg/m³ in ACR-PUR varnish. In chamber air, its concentrations averaged 30.19 ± 11.45 µg/m³ in days 14–21 but fell below detection by day 60, consistent with its high volatility and photochemical reactivity.

Finally, 1-ethyl-2-methylbenzene, a by-product of varnish manufacture and a respiratory irritant, was detected at 38.28 ± 4.67 µg/m³ (PUR) and 25.27 ± 3.92 µg/m³ (ACR-PUR) in varnishes, with indoor concentrations of 0.33 ± 0.16 µg/m³ during days 14–21 and non-detectable after 60 days. Similarly, EGEE (2-ethoxyethanol), a glycol ether solvent, was measured at 1.21 ± 0.14 µg/m³ (PUR) and 6.45 ± 0.97 µg/m³ (ACR-PUR), while indoor levels declined from 0.090 ± 0.026 µg/m³ (days 14–21) to 0.044 ± 0.020 µg/m³ (day 60).

Overall, reproductive toxicants displayed different emission behaviours: some (e.g., toluene, DMF) declined rapidly, while others (e.g., MBK, phthalates) persisted for weeks. This mixture of transient and long-lasting compounds underlines the complexity of indoor exposure scenarios and their relevance to both acute and chronic SBS symptoms.

3.1.2. Mutagens in Indoor Air from Polyurethane and Acryl-Polyurethane Lacquers

Polyurethane and acryl-polyurethane lacquers can release mutagenic compounds into indoor environments, particularly benzene, glyoxal, and phenol. Benzene, a well-known mutagen and human carcinogen, originates both from natural components of wood, such as lignin and extractives, and from varnish composition. Studies have reported emissions of up to 12.82 µg/m³ from untreated solid wood (Wang et al., 2022), while concentrations in our test materials were substantially higher: 37.56 ± 11.89 µg/m³ in PUR varnish and 32.73 ± 6.83 µg/m³ in ACR-PUR varnish. In chamber air, benzene levels reached 28.42 ± 14.98 µg/m³ during days 14–21, exceeding average background values in European households 8.42 ± 14.98 µg/m³ (Fromme et al., 2025). By day 60, however, concentrations had dropped below detection, consistent with observations by Kumar et al., (2023) that VOCs from coatings rapidly decline due to volatilisation, photochemical degradation, and dilution.

Phenol is another mutagenic compound frequently found indoors, originating from coatings, adhesives, carpets, plastics, and wooden furniture. Reported background levels range from 0.2 to 21.5 µg/m³ (Campagnolo et al., 2017). In our measurements, phenol emissions from PUR varnish reached 46.04 ± 29.23 µg/m³, while ACR-PUR varnish produced 37.64 ± 11.90 µg/m³. Indoor chamber concentrations were much lower but still notable at 4.53 ± 1.97 µg/m³ (days 14–21), followed by a sharp decline to 0.06 ± 0.004 µg/m³ after 60 days. This reduction is in accordance with systematic reviews indicating that VOC emissions from coatings and building materials can diminish by 90–99% within two months of application (Kumar et al., 2023).

Glyoxal, used as a cross-linking agent in polymers and also applied as a biocide, was identified at 10.63 ± 0.97 µg/m³ in ACR-PUR varnish. Chamber concentrations averaged 0.35 ± 0.09 µg/m³ during days 14–21, comparable to residential indoor levels of 0.42 µg/m³ reported by Duncan et al. (2018). In more oxidative indoor environments, however, glyoxal has been detected at ~2 µg/m³ (Huang et al., 2019). Its absence by day 60 reflects its high reactivity and instability: as a small α-dicarbonyl compound, glyoxal undergoes rapid heterogeneous reactions with nucleophilic functional groups, sorption to surfaces, and transformation into secondary products such as imines, acetals, or oligomers. This behaviour explains its relatively short persistence in indoor air without continued emission sources.

3.1.3. Carcinogens and Potential Carcinogens in Indoor Air from Polyurethane and Acryl-polyurethane Lacquers

Several carcinogenic or potentially carcinogenic compounds were detected in association with PUR and ACR-PUR varnishes, including 1,4-dioxane, acetamide, vinyl acetate, isopropylbenzene, p-aminotoluene, tetrachloroethylene, benzophenone, and residual polymeric methylene-diphenyl diisocyanate (RMDI). As discussed in Section 3.2.3, benzene is included as one of the most relevant agents.

1,4-Dioxane, a possible human carcinogen, may occur as a residual solvent or degradation product of polyether components in varnishes. It was detected in PUR varnish at 1.69 ± 0.26 µg/m³ and at identical levels in chamber air during days 14–21. By day 60, concentrations had declined to 0.053 ± 0.002 µg/m³, approaching background values reported for households in Japan (0.02 µg/m³) (Tanaka-Kagawa et al., 2005). Importantly, the EU-US risk screening level for long-term cancer risk is 0.2 µg/m³ (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2024), meaning concentrations during the early phase exceeded health-based thresholds, though they dropped to safe levels after two months.

Acetamide, a possible by-product of synthesis or an additive, was present at ~4–5 µg/m³ in both varnish types. Chamber concentrations were modest (0.073 ± 0.052 µg/m³ during days 14–21) but increased slightly to 0.123 ± 0.003 µg/m³ after 60 days. Such delayed release is atypical but consistent with diffusion-limited behaviour in highly cross-linked polymer matrices and with potential secondary indoor sources, such as MDF panels and linoleum (Adamová et al., 2020).

Vinyl acetate, used in hybrid polymer binders, was measured at 1.80 ± 0.21 µg/m³ in PUR and 13.17 ± 8.27 µg/m³ in ACR-PUR varnishes. Indoor chamber concentrations rose from 0.621 ± 0.48 µg/m³ (days 14–21) to 1.534 ± 1.09 µg/m³ after 60 days. This trend mirrors findings by Huang et al. (2019) and reflects the slow release of polymer-bound volatiles under realistic indoor conditions.

Isopropylbenzene (cumene), a precursor for methyl methacrylate, was present at 7.67 ± 0.19 µg/m³ in PUR and 1.63 ± 0.70 µg/m³ in ACR-PUR varnishes. In chamber air, concentrations stabilised around 0.44 ± 0.18 µg/m³ (days 14–21) and 0.40 ± 0.01 µg/m³ (day 60), reflecting its relatively low volatility, high boiling point, and chemical stability.

p-Aminotoluene, an aromatic amine and known carcinogenic intermediate in pigment and polyurethane production, was found at 0.61 ± 0.05 µg/m³ in PUR varnish and 0.062 ± 0.026 µg/m³ in chamber air during days 14–21. By day 60, concentrations fell below detection, consistent with literature values for indoor environments (Palmiotto et al., 2001).

Tetrachloroethylene, widely used as a solvent in coatings, was present at ~25 µg/m³ in both PUR and ACR-PUR varnishes. Chamber air levels were much lower, averaging 0.062 ± 0.046 µg/m³ during days 14–21 and 0.040 ± 0.010 µg/m³ after 60 days. Despite rapid initial volatilisation, its persistence suggests slow desorption from indoor surfaces such as textiles and wall materials, aligning with results reported by Fromme et al. (2025).

Benzophenone, a photoinitiator and possible human carcinogen, was detected at ~20–25 µg/m³ in both varnish types. In chamber air, concentrations were 0.043 ± 0.013 µg/m³ during days 14–21 but dropped below detection by day 60. This pattern is consistent with previous studies showing its partitioning onto dust particles and resuspension in indoor air (Wan et al., 2015).

Finally, polymeric methylene-diphenyl diisocyanate (RMDI), classified by ECHA as a suspected human carcinogen (Category 2), was detected as multiple stereoisomers in indoor air. Between days 14–21, total concentrations reached 0.108 ± 0.028 µg/m³, dominated by the cis,trans isomer at 0.042 ± 0.007 µg/m³. Emissions were substantially higher in ACR-PUR varnishes (403.88 ± 42.76 µg/m³) than in PUR varnishes (64.05 ± 13.76 µg/m³), reflecting differences in prepolymerisation degree and residual monomer content (Cao et al., 2025). By day 60, however, all isomers were below detection, suggesting progressive degradation, sorption, and diffusion processes typical of reactive isocyanates.

In summary, these findings confirm that both mutagens and carcinogens are relevant components of varnish emissions. Although many compounds decline rapidly within two months, several exceed health-based guidance levels during the early post-application period, highlighting the importance of ventilation and material selection in indoor environments.

3.2. Toxicological Profile of PUR and ACR-PUR Coatings

The comparative analysis of PUR and ACR-PUR coatings demonstrates apparent differences in composition and toxicological relevance of emitted compounds. These variations are critical for assessing health risks associated with indoor exposure (

Table 3).

ACR-PUR coatings exhibited a higher neurotoxic potential, primarily due to elevated levels of 1,3-dioxolane (42.72 ± 31.05 µg/m³), compared to PUR (73.36 ± 10.75 µg/m³). This compound is associated with central nervous system effects and sensory irritation, indicating a strong neurobehavioral relevance of ACR-PUR emissions.

Reproductive toxicants also showed contrasting profiles. ACR-PUR contained markedly higher concentrations of styrene (188.65 ± 87.25 µg/m³) and toluene (816.65 ± 215.10 µg/m³), both linked to endocrine disruption and developmental toxicity. PUR, on the other hand, was characterised by higher levels of phthalates, particularly bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (62.66 ± 11.33 µg/m³), known to impair fertility and foetal development. These divergent pathways indicate that both coatings present reproductive risks, though via different mechanisms.

Mutagenic compounds were detected in both formulations. Benzene was dominant in PUR (37.56 ± 11.89 µg/m³), while glyoxal was more prominent in ACR-PUR (10.63 ± 0.97 µg/m³). Phenol was common to both, further contributing to the mutagenic burden under prolonged exposure conditions.

Carcinogenic and potentially carcinogenic substances displayed the strongest contrast. ACR-PUR contained significantly higher levels of reactive methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (RMDI) isomers, such as cis,trans- (213.17 µg/m³) and cis,cis- (153.10 µg/m³), which are associated with tumorigenic outcomes. Tetrachloroethylene (24.09 ± 7.65 µg/m³) and benzophenone (24.56 ± 1.28 µg/m³) were also more abundant in ACR-PUR, reinforcing its elevated carcinogenic potential.

These results indicate that ACR-PUR coatings pose a substantially greater toxicological burden across all evaluated categories. While PUR coatings are comparatively less hazardous, the presence of persistent compounds such as phthalates and benzene requires attention in long-term exposure scenarios.

3.4. Integrated Evaluation of Emission Behaviour and Exposure Relevance

Neurotoxicants such as 1,3-dioxolane maintained a stable transfer efficiency of 3.37% between day 14 and day 21 (2.46 ± 0.90 µg/m³ from 73.36 ± 10.75 µg/m³) and 3.39% at day 60 (2.47 ± 0.16 µg/m³ from 72.72 ± 11.40 µg/m³). This persistence confirms their potential for long-term neurobehavioral effects.

Reproductive toxicants showed the highest absolute emission load (1460 ± 121 µg/m³), but their transfer efficiency was relatively low: 3.25% between day 14 and day 21, falling to 0.30% by day 60. MBK remained comparatively stable (0.61 ± 0.14 µg/m³ versus 0.60 ± 0.15 µg/m³), whereas phthalates, toluene, and styrene declined sharply. These findings highlight the dominance of acute risks in the early phase and a limited set of persistent contributors to long-term exposure.

Mutagenic compounds displayed high early transfer rates (37.16%), particularly phenol (63.51%), but by day 60 their concentrations nearly disappeared (0.06 ± 0.004 µg/m³). It confirms their acute relevance and limited persistence in indoor air.

Carcinogens initially had low transfer rates, about 0.24% of total emissions, but several persisted over time. Ethenyl acetate increased slightly from 0.62 ± 0.48 µg/m³ to 1.53 ± 1.09 µg/m³, while acetamide and isopropylbenzene remained nearly constant. RMDI isomers and most aromatic carcinogens were present only in the early phase.

Quantitatively, aromatic hydrocarbons and alcohols accounted for more than 60% of the total VOC reduction between days 14–21 and day 60, confirming their key role in the early emission phase and their high volatility shortly after application. Esters and phthalates contributed significantly to the overall decline, although their decrease was more gradual, likely due to sorption on surfaces or within the coating matrix. Groups with marginal contributions, such as amines, amides, and ethers, showed either low initial concentrations or limited volatility, thereby reducing their overall influence on the emission balance. From the quantified compounds, 83.2% of the total VOC reduction was captured, while the remaining 16.8% represented residual concentrations that were either not degraded or had fallen below the detection limit. These substances are often characterised by low reactivity or long-term persistence and are critical for assessing chronic exposure and designing targeted filtration measures, particularly in spaces with insufficient ventilation.

Acute risks are primarily associated with highly volatile substances released shortly after coating application, while chronic exposure is shaped by low-volatility compounds with persistent emission profiles. This dual pattern underscores the importance of time-resolved assessment for effective indoor air quality management.

3.5. Sick Building Syndrome

Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) refers to a set of health problems reported by occupants of specific buildings without the identification of a distinct illness or single causative factor. As described by Norback et al. (Norback et al., 1990), SBS has a multifactorial origin, reflecting a complex interaction of chemical, physical, and psychosocial conditions. Rather than being attributable to a single pollutant, SBS arises from a combined exposure to volatile organic compounds (VOCs), inadequate indoor climate parameters (such as temperature and humidity), poor lighting, noise, occupational stress, and individual sensitivity. The heterogeneity of human response is significant, since compounds that may be tolerated by one individual can cause irritation or systemic effects in another.

3.5.1. Comparison of Coatings

The chemical compositions of emissions from polyurethane (PUR) and acryl–polyurethane (ACR-PUR) coatings show pronounced differences that can be directly linked to their SBS potential (

Table 5).

Polyurethane lacquer (PUR) is characterised by a relatively high content of alcohols (994.3 ± 135.6 µg/m³), consistent with a traditional solvent system of lower reactivity. Its emission profile also reveals lower levels of aromatic hydrocarbons (112.8 ± 34.2 µg/m³), which are typically associated with neurotoxicity and sensory irritation, and only limited concentrations of isocyanates (64.0 ± 18.3 µg/m³). Such a profile suggests either a less reactive formulation or an efficient curing process with minimal residual monomers. From the perspective of SBS, this corresponds to a coating with reduced potential to trigger acute sensory symptoms, although alcohols and diols (254.8 ± 42.7 µg/m³) still contribute substantially to overall VOC load and odour perception.

In contrast, ACR-PUR lacquer exhibits a more complex and aggressive emission spectrum. Elevated concentrations of aromatic hydrocarbons (946.2 ± 175.4 µg/m³), esters (280.8 ± 51.2 µg/m³), diols (412.7 ± 63.5 µg/m³), ethers (198.3 ± 40.1 µg/m³), and isocyanates (403.9 ± 72.6 µg/m³) are observed, reflecting a multi-component system modified with acrylates. These modifications, while improving the mechanical and optical properties of the coating, also enhance the volatility and reactivity of the formulation, which significantly increases its emission potential and toxicological burden. As a result, ACR-PUR coatings can be expected to pose a greater risk for SBS symptom onset, especially in enclosed spaces with limited ventilation.

While alcohols dominate in PUR (994.3 ± 135.6 µg/m³), ACR-PUR is strongly characterised by aromatic hydrocarbons (946.2 ± 175.4 µg/m³) and isocyanates (403.9 ± 72.6 µg/m³). This contrast is further emphasised in the bar chart, where compounds are distributed according to their SBS-related potential. Here, PUR is dominated by compounds of moderate relevance, whereas ACR-PUR belongs to strong and medium-strong categories, highlighting its elevated symptomatic potential.

PUR coatings, despite lower overall aggressiveness, still contain compounds capable of provoking irritation during prolonged exposure, whereas ACR-PUR coatings present a higher SBS risk due to elevated levels of strongly symptomatic chemical groups.

3.5.2. Indoor Air Quality After Coating Application

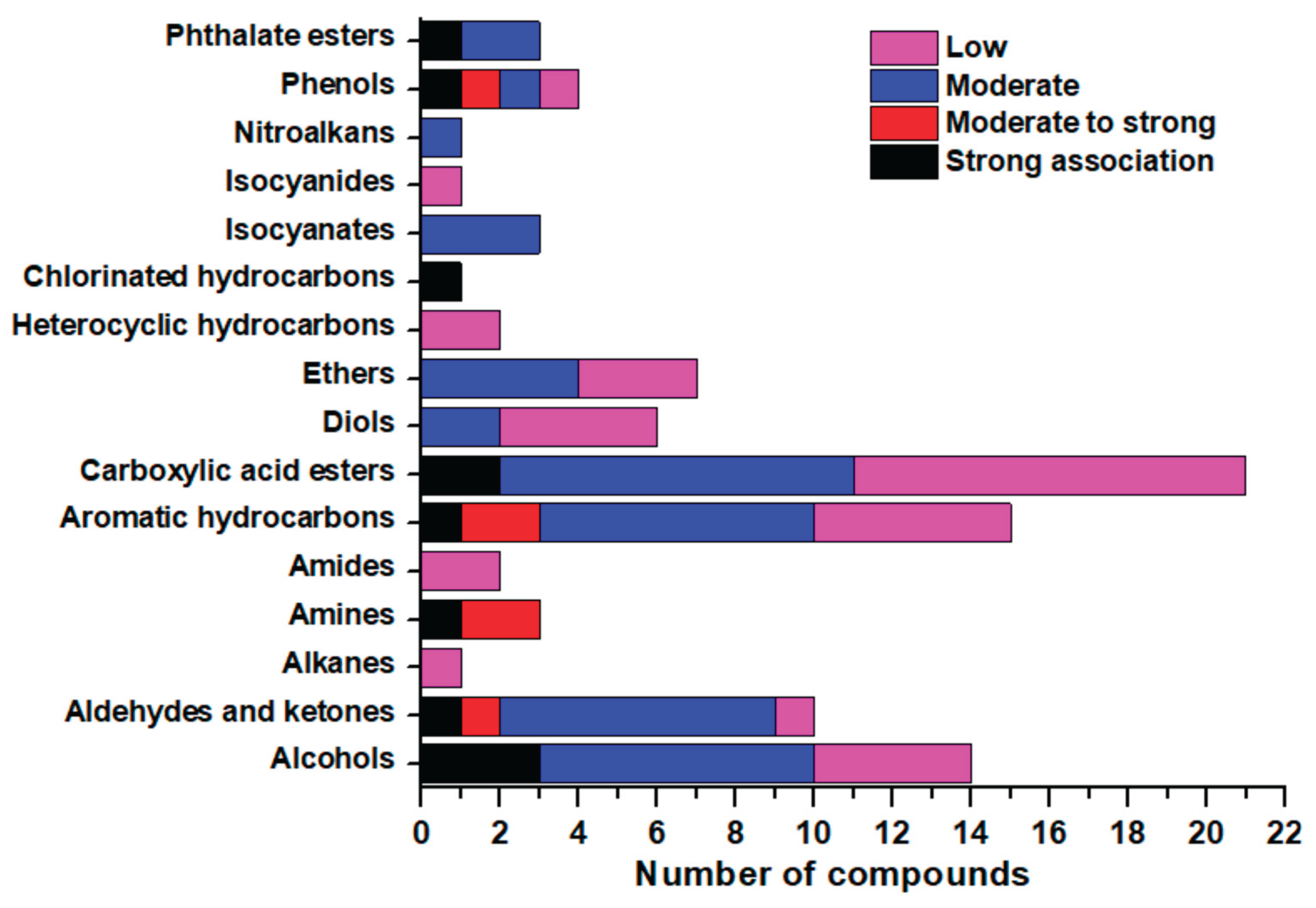

A total of 94 compounds were identified and classified into 16 chemical groups based on their structural characteristics and known associations with Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) symptoms. The distribution of these compounds by chemical class and their relative SBS relevance is shown in

Figure 1. The test chamber contained no additional materials or furnishings, which allowed a clear attribution of the measured concentrations to the coatings applied.

Most detected compounds were alcohols, aromatic hydrocarbons, and carboxylic esters, reflecting their role as primary components of waterborne coatings. These groups are strongly or moderately associated with SBS-related symptoms, including mucosal irritation, neurotoxicity, and sensory discomfort. Aldehydes, diols, ethers, and amines were also present at relevant levels, indicating secondary emissions from degradation or polymerisation processes during film curing. In contrast, groups such as isocyanates, isocyanides, nitroalkanes, alkanes, and heterocyclic hydrocarbons were represented only by individual compounds. Despite their low numbers, their toxicological significance and reactivity justify their inclusion in acute SBS screening, particularly in poorly ventilated environments.

Figure 1 illustrates the total number of chemical compounds with SBS relevance in indoor air 14–21 days after coating application, and their persistence after 60 days. At the earlier interval, compounds with strong or moderate-to-high SBS associations were dominant, confirming their role in acute symptom onset. Overall, 94 compounds were identified, of which 17 showed strong or moderate-to-strong association with SBS symptoms. Since all detected substances originated from a single emission source, it was possible to evaluate their emission behaviour and symptomatic relevance with higher accuracy and without interference from other materials. By day 60, most of these substances had declined substantially, but compounds with moderate association remained at detectable levels, representing a long-term exposure concern.

At the earlier interval, compounds with strong or moderate-to-high SBS associations were dominant, confirming their role in acute symptom onset. By day 60, most of these substances had declined substantially, but compounds with moderate association remained at detectable levels, representing a long-term exposure concern.

Quantitative analysis confirms this temporal pattern. Compounds with strong SBS association decreased from 37.03 ± 2.94 µg/m³ at 14–21 days to 2.94 ± 0.41 µg/m³ at 60 days, corresponding to a 92% reduction. Substances with moderate-to-high SBS association showed an even steeper decline of 99%, from 49.51 ± 0.33 µg/m³ to 0.33 ± 0.07 µg/m³. In contrast, compounds classified as moderate exhibited only a 67% reduction (48.16 ± 1.60 µg/m³ to 16.04 ± 0.98 µg/m³), confirming their persistence and chronic relevance. Compounds with low SBS association decreased by 89% (45.91 ± 0.50 µg/m³ to 4.95 ± 0.22 µg/m³).

The greatest relative reductions were observed for phthalate esters (99.1%), phenols (98.8%), diols (98.4%), aromatic hydrocarbons (97.7%), and carboxylic esters (89.8%), consistent with their high volatility and acute emission profiles. In contrast, aldehydes and ketones showed the lowest reduction (32%), reflecting their stability and persistent contribution to indoor air quality. This persistence aligns with long-term field studies, which emphasise the role of aldehydes as chronic drivers of SBS symptoms.

The results confirm a dual emission behaviour: acute SBS symptoms are driven by highly volatile compounds released during the first weeks after coating application, whereas chronic effects are sustained by persistent compounds such as aldehydes, ketones, and low-volatility esters. These findings underscore the need for time-resolved SBS risk classification that accounts not only for chemical type but also for emission dynamics.

In addition, groups such as isocyanates, isocyanides, nitroalkanes, and alkanes were monitored. These compounds showed very low initial concentrations and declined below the detection limit of the analytical method after 60 days. Although their absolute values were minimal, their toxicity, reactivity, and ability to trigger sensitisation justify their inclusion in the acute screening panel, particularly in environments with limited ventilation or in the presence of cumulative VOC emissions.

Aromatic hydrocarbons and alcohols accounted for more than 60% of the total VOC reduction between days 14–21 and day 60, confirming their key role in the early emission phase and their high volatility shortly after application. The relative decrease in concentrations of individual chemical groups between days 20 and 60 and their contribution to the overall reduction of VOC burden. Esters and phthalates contributed significantly to the decline, although their decrease was more gradual, likely due to sorption on surfaces or within the coating matrix. Groups with marginal contributions, such as amines, amides, and ethers, showed either low initial concentrations or limited volatility, thereby reducing their overall influence on the emission balance. From the quantified compounds, 83.2% of the total VOC reduction was captured, while the remaining 16.8% represented residual concentrations that were either not degraded or had fallen below the detection limit. These substances – often characterised by low reactivity or long-term persistence – are critical for the assessment of chronic exposure and for the design of targeted filtration measures, particularly in spaces with insufficient ventilation.

Compared with international indoor air standards, the total VOC (TVOC) values measured 14–21 days after coating application reached 180.61 ± 60.6 µg/m³. According to the German UBA guideline values (Umweltbundesamt, 2007), this corresponds to excellent air quality (< 200 µg/m³). The result is also in accordance with the WHO (Adamkiewicz and World Health Organization, 2010) recommendations, which consider TVOC levels below 300 µg/m³ as indicative of good indoor air quality. However, despite compliance with these guideline values, the presence of specific neurotoxic, reprotoxic, and irritant compounds at measurable concentrations suggests that the indoor environment may still trigger SBS-related symptoms in sensitive individuals. This finding supports the view expressed by Wolkoff, (2013), who emphasised that TVOC alone is not a reliable predictor of health outcomes, since SBS symptoms are more closely linked to the toxicological profiles of individual compounds than to their total concentration.