1. Introduction

Tuberculosis remains one of the most significant global public health challenges, representing a persistent issue in the control of infectious diseases. The COVID-19 pandemic has further intensified these challenges, directly affecting the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. According to the Global Tuberculosis Report 2024 by the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 10.8 million people developed tuberculosis in 2023, with an estimated 1.25 million deaths attributed to the disease. Additionally, it is estimated that 2.7 million people remained undiagnosed or unreported, exacerbating underreporting and complicating epidemiological control efforts [

1].

In Brazil, according to the 2024 Tuberculosis Epidemiological Bulletin published by the Ministry of Health, 84.308 new tuberculosis cases were reported in 2024, corresponding to an incidence rate of 39.7 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. In 2023, there were 6.025 tuberculosis-related deaths in the country, resulting in a mortality rate of 2.8 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants [

2].

This scenario is especially alarming among vulnerable populations, such as people coinfected with HIV, individuals in correctional facilities, and those experiencing homelessness. Living conditions and socioeconomic factors directly influence the incidence and spread of tuberculosis within these groups. In correctional facilities, where overcrowding and poor ventilation are common, tuberculosis prevalence is significantly higher than in the general population. Such environments function as institutional amplifiers of infectious diseases, including tuberculosis and HIV, facilitating transmission due to overcrowding, poor ventilation, and limited access to healthcare services [

3]. This vulnerability is exacerbated during crisis situations, such as natural disasters, which further compromise sanitary conditions and disrupt prevention and treatment efforts [

4]. The structural inadequacies of correctional facilities not only increase health risks for incarcerated individuals but also pose an ongoing threat to public health, hindering tuberculosis control both inside and beyond penitentiary settings [

3,

5]. In Latin America, the incidence of tuberculosis among incarcerated individuals is up to 26 times higher than in the general population [

5].

In addition to technical limitations, access to diagnosis is hindered by logistical barriers, such as geographic location and transportation and infrastructure challenges in hard-to-reach areas [

6]. These barriers are particularly impactful in isolated populations, such as those on islands, in remote areas, or in penitentiaries. Thus, there is an urgent need to improve access to, as well as increase the quality of, diagnostic methods, particularly in resource-limited regions.

In recent years, our group has focused on developing and validating simplified DNA extraction protocols from complex matrices, such as sputum or skin biopsies, that can be used in low-resource settings [

7,

8]. We have shown that the DNA obtained by these protocols allows, under laboratory conditions, for the identification of genomic markers of pathogenic organisms such as

Mycobacterium tuberculosis or

Mycobacterium leprae, helping in the diagnosis of tuberculosis and leprosy, respectively [

8,

9]. Interestingly, despite belonging to the same phylogenetic genus, we have found that the matrix of the sample exerts a bigger influence on the simplified DNA extraction protocol of the bacilli

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and

Mycobacterium leprae: Sputum is better liquified using thiocyanate salts, while skin is better liquified using urea as chaotropic salts.

Despite the recognized impact of tuberculosis on vulnerable and hard-to-reach populations, access to rapid and reliable molecular testing remains extremely limited in these settings. Unlike established portable molecular platforms like GeneXpert Ultra and Truenat, which rely on proprietary cartridges and cold-chain storage, our simplified DNA extraction protocol, combined with a portable quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) device, operates with minimal equipment and reduced cost. This configuration reduces overall costs, eliminates reliance on specialized consumables, and allows molecular testing to be performed in settings without conventional laboratory infrastructure. In the present study, we sought to validate the simplified protocol, coupled with a portable qPCR instrument, in its intended setting, namely, low-resource and hard-to-reach environments, including an incarceration facility. Our main aim is to show that the simplified platform is suitable for performing active searches in specific areas, helping health officials to tackle outbreaks in specific situations by screening the local population using a molecular diagnostic test.

2. Results

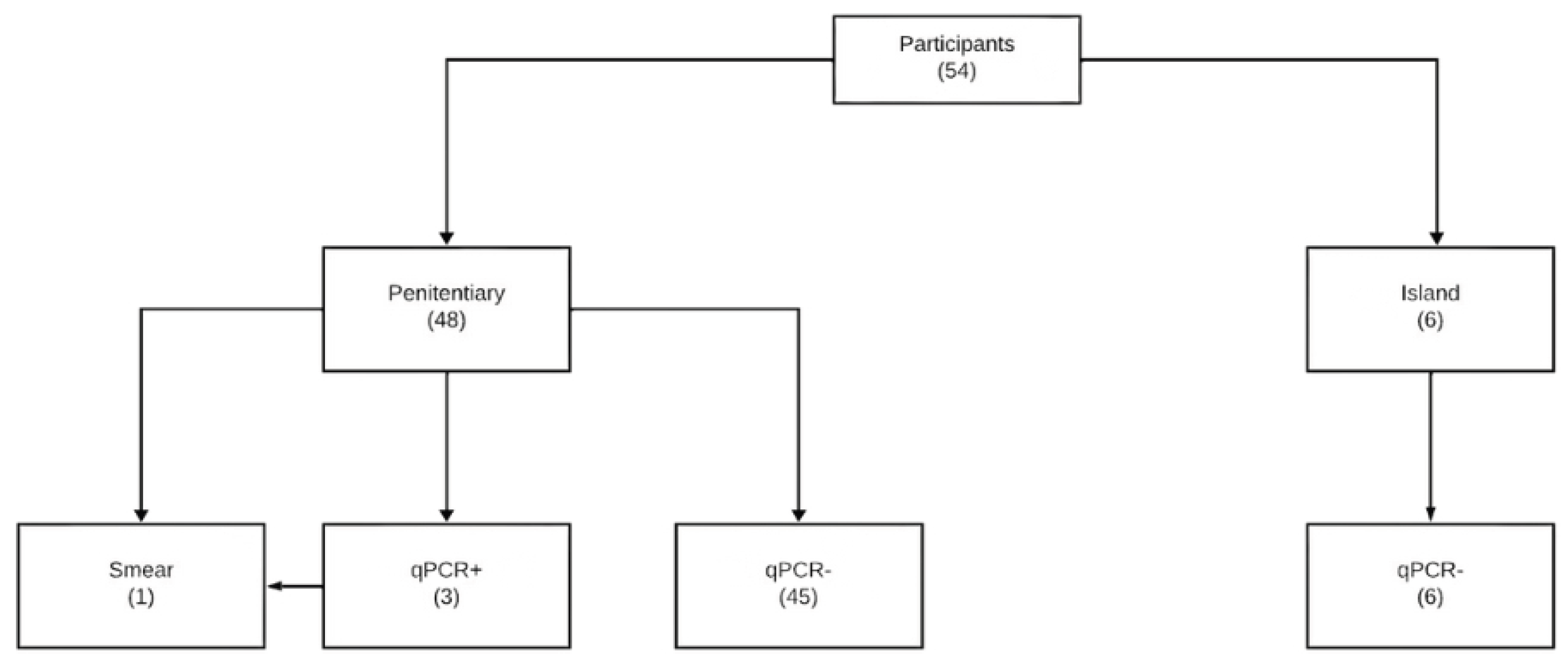

This The human marker 18S rRNA was detected within an acceptable range in all samples, indicating the successful performance of the DNA extraction protocol, as well as the qPCR setup, in both low-infrastructure locations. Of the 48 samples collected at the Venâncio Aires State Penitentiary (PEVA), 3 were positive for M. tuberculosis DNA. Only 1 of them was also positive in sputum smear microscopy, and none presented a positive culture in the confirmatory test. Because no culture-positive samples were obtained, this study did not aim to estimate sensitivity or other diagnostic performance parameters. Instead, the results demonstrate the feasibility and operational applicability of performing portable qPCR-based screening for M. tuberculosis directly in the field. The mean cycle threshold (Ct) value for IS6110 amplification among the three qPCR-positive samples was 36.2 ± 3.4, while the internal control 18S rRNA amplified consistently with Ct values of 19.4 ± 2.5, confirming both DNA integrity and successful reaction performance.

To better illustrate distribution of results across methods, we summarized the results obtained with qPCR, smear microscopy, and culture (

Table 1). Among the 54 sputum samples analyzed, qPCR identified three positives (5.6%), while smear microscopy confirmed only one case (1.9%), and culture yielded no positive results. In five participants, confirmatory testing by smear microscopy and culture could not be performed due to insufficient sample collection on the following day.

The absence of culture-positive results represents an important limitation of this study, as it prevented the use of a reliable microbiological gold standard and precluded the estimation of sensitivity and specificity. Consequently, the findings should be interpreted strictly as a feasibility demonstration rather than as a diagnostic performance assessment.

The flow of participants, from recruitment to diagnostic testing and inclusion in the analyses, is presented in

Figure 1.

No indeterminate or invalid results were observed in either the qPCR or the reference standard tests. All samples produced valid and analyzable results. The agreement between qPCR and smear microscopy was moderate, with a Cohen's Kappa coefficient of 0.484 (IC 95%: 0,24–0,73; z = 3.91, p = 0.00009), indicating statistically significant agreement beyond chance.

Five of the 48 participants did not undergo sputum smear microscopy because they were unable to produce a sufficient sputum sample on the following day for confirmatory testing. These cases were excluded from the agreement analysis. All qPCR results were complete and valid, and no indeterminate or invalid results were observed for either the index or reference tests.

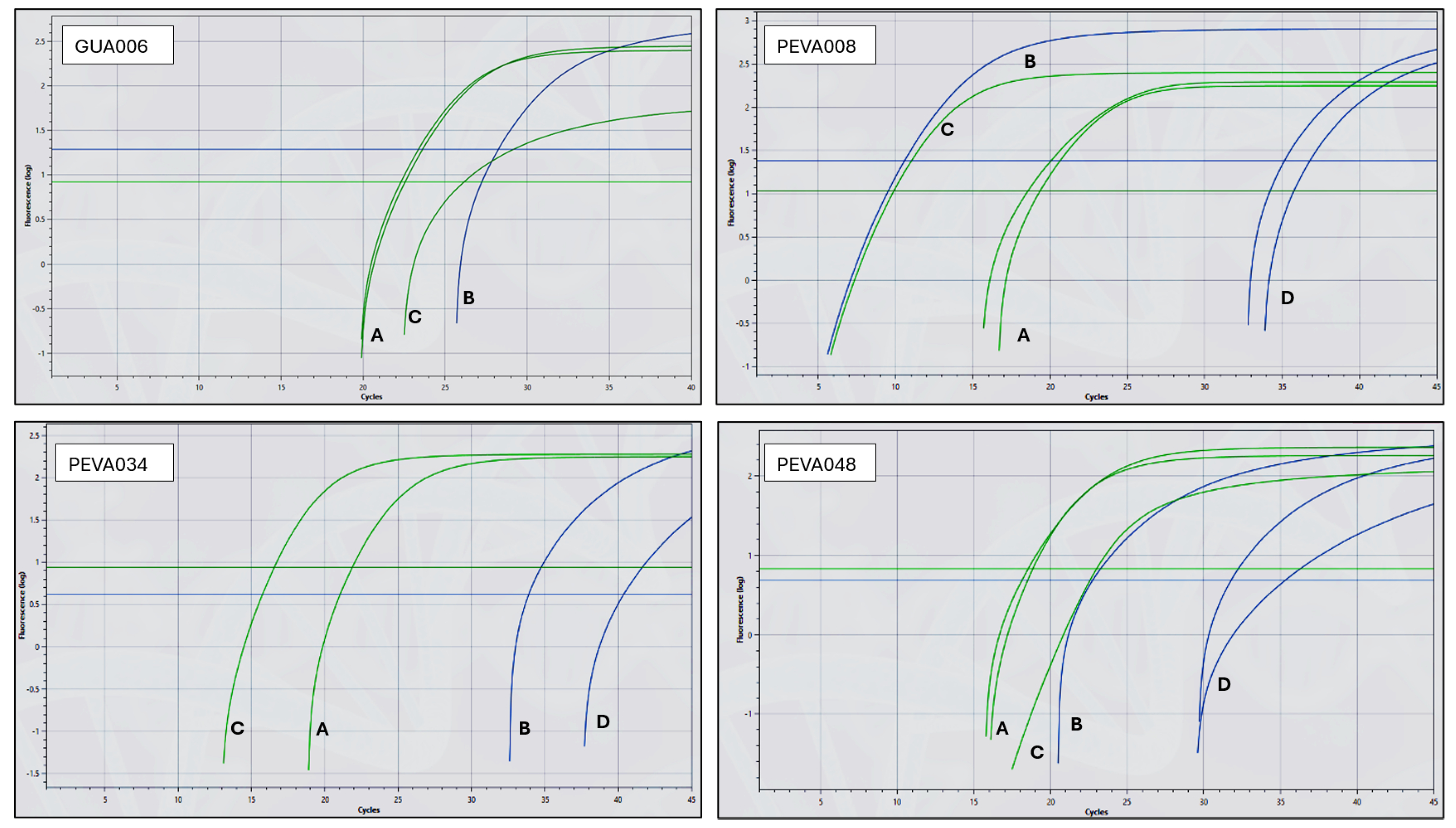

Figure 2 presents representative amplification curves for positive and negative samples. The green curves represent amplification of the human 18S rRNA gene, while the blue curves indicate amplification of the genomic marker IS6110, specific for

M. tuberculosis. The observed Ct values for the IS6110 and 18S rRNA targets were consistent with the mean values reported above. To validate the reactions, both controls (synthetic DNA containing the IS6110 oligonucleotide sequences and extracted human DNA) were added to one of the six wells of each chip. Therefore, successful amplification of the green (18S rRNA) and blue (IS6110) curves in this control well is expected in all valid chips. In negative samples, such as GUA006, no amplification of IS6110 is observed in the clinical sample wells. However, the control well shows successful amplification for both targets: IS6110 (GUA006 panel, line B; Ct 28.2) and 18S rRNA (GUA006 panel, line C; Ct 26.1), confirming the validity of the reaction. Additionally, the internal control for human DNA in the sample wells (green, lines A, Ct 22.4 ± 0.18) confirms adequate nucleic acid extraction. In positive samples, such as PEVA048, amplification of the IS6110 target is observed in the clinical sample wells (blue, lines D; Ct 34.7±4.11), indicating the presence of

M. tuberculosis DNA. The internal control (green, line A; Ct 18.69 ± 0.22) confirms sample integrity. The control well also amplified both targets (IS6110, line B; Ct 22.5 and 18S rRNA, line C; Ct 23.0), validating the chip and confirming overall reaction performance.

No adverse events were observed or reported because of performing the qPCR (index test) or the reference standard tests (smear microscopy and culture).

3. Discussion

The application of a simplified DNA extraction protocol, followed by the use of a portable qPCR instrument in two challenging environments outside laboratory settings, proved effective for detecting M. tuberculosis DNA in 3 out of 54 collected sputum samples. These results highlight the feasibility of this procedure under challenging conditions, suggesting that this approach might contribute significantly to tuberculosis detection in high-risk populations and to assist in controlling the disease in remote and confined locations.

Compared to existing portable molecular platforms such as GeneXpert Ultra and Truenat, which rely on proprietary cartridges, specialized consumables, and strict cold-chain storage, our simplified protocol requires only basic rea-gents and minimal equipment. This reduces both logistical complexity and operational costs, while maintaining analytical reliability. Moreover, the method can be executed by personnel with basic technical training, further enhancing its applicability in field conditions where laboratory infrastructure and specialized expertise are limited.

The demographic and clinical data presented in

Table 1 provide a deeper understanding of some of the participants' characteristics, emphasizing factors that may influence the prevalence and transmission of tuberculosis (TB) within penitentiary settings. The presence of TB-related symptoms in 25% of participants and the high prevalence of smoking (40%) reflect the respiratory vulnerability of this population and reinforce the need for accessible diagnostic strategies. These findings also illustrate how tuberculosis can often be mistaken for other conditions, such as colds, influenza, allergies, or even the consequences of smoking, leading to delayed recognition and underdiagnosis, particularly in high-risk environments. Smoking is a well-documented risk factor for the development and progression of TB, as it compromises pulmonary health and increases susceptibility to respiratory infections. which, combined with overcrowded and poorly ventilated conditions, underscores the relevance of deploying portable diagnostic tools for early case detection. Therefore, rather than exploring behavioral determinants in depth, this study focuses on demonstrating the operational feasibility of implementing on-site molecular testing in such high-risk environments.

Overcrowding, limited ventilation, and close contact among incarcerated individuals create conditions that facilitate the spread of various microorganisms, including

M. tuberculosis. Correctional facilities are recognized as propitious environments for the transmission of tuberculosis, characterized by overcrowded and poorly ventilated spaces and a high turnover of inmates, which perpetuates the introduction and spread of infectious diseases. Global studies indicate a higher incidence of TB among incarcerated populations compared to the general population, highlighting the importance of active case finding and early diagnosis in such settings [

15,

16].

Molecular biology-based methods, such as PCR, offer significant advantages over traditional methods like sputum smear microscopy and culture. Its higher sensitivity enables the detection of DNA fragments from the bacillus, even in cases of low bacterial load or latent infections. This also explains the positive results observed, even when not con-firmed by other techniques. PCR can detect not only active infections but also latent cases or residual DNA fragments in samples where viable bacilli are insufficient for culture [

17]. This occurs because PCR detects DNA, rather than live microorganisms, which can yield positive results even in patients who have eradicated the infection but still retain the pathogen’s DNA in their bodies. Positive PCR results can reflect either an active infection or a history of tuberculosis, necessitating caution in interpreting these data and highlighting the importance of clinical evaluation for case confirmation [

18].

The moderate agreement observed between qPCR and smear microscopy reflects the intrinsic differences between these diagnostic methods. While smear microscopy relies on the direct visualization of bacilli and is limited by bacteria-al load and operator expertise, qPCR can detect minimal amounts of M. tuberculosis DNA, including in paucibacillary or early-stage cases. This supports the interpretation that these methods are complementary, not interchangeable, and reinforces the importance of integrating molecular results with clinical evaluation and, when feasible, additional di-agnostic tools to ensure accurate diagnosis. Nevertheless, the moderate level of agreement (Kappa = 0.48) should be interpreted with caution, as the very small number of positive samples limits the statistical robustness of this estimate and may lead to wide confidence intervals. Therefore, these findings should be viewed as preliminary and supportive of feasibility rather than as definitive evidence of diagnostic concordance.

The simplified DNA extraction protocol, followed by a portable qPCR assay, has proven advantageous for field applications, offering convenience and portability, which are key factors for on-site screening. [

7,

9] This approach avoids the need to transport samples to distant laboratories, facilitates rapid diagnostics, and supports timely clinical decision-making in resource-limited settings. Portability eliminates the need to transport samples to distant laboratories, which is particularly critical in hard-to-reach areas, where logistical transport is complex and time-consuming. Performing tests on-site also reduces the risk of sample degradation or contamination. The portable qPCR provides results within a few hours, enabling rapid clinical decisions and, consequently, reducing the window of disease trans-mission. Its high sensitivity also effectively detects bacterial DNA in samples with low bacterial load, which is crucial in overcrowded settings, such as correctional facilities, where the risk of tuberculosis transmission is elevated. Additionally, early diagnosis strategies, particularly in penitentiary settings, have been shown to significantly increase tuberculosis case notifications and contribute to better disease control among people deprived of liberty [

19].

Despite these benefits, the use of portable qPCR still faces significant challenges. The need for trained operators and the relatively high cost of reagents and equipment remain major obstacles in regions with limited financial and human resources potentially restricting the widespread use of this technology.

Study limitations must be acknowledged. The small number of positive TB cases (n = 3) limits the statistical power to conclusions about diagnostic accuracy or subgroup performance. These findings should thus be interpreted within the context of a proof-of-concept feasibility study, designed to demonstrate operational applicability in challenging field conditions rather than to provide robust accuracy metrics. Additionally, the study was conducted in two specific and controlled environments (a remote village and a penitentiary), which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or settings. Although procedures were standardized and anonymized, the absence of a formal clinical follow-up may introduce uncertainty regarding the final diagnostic status of the participants. Although blinding procedures were rigorously applied, field operators necessarily knew that participants were recruited based on symptoms or cell-sharing, which may introduce residual expectation bias despite not having access to individual clinical details. Moreover, the implementation of portable qPCR in the field is still challenged by the relatively high cost of reagents and equipment, as well as the need for operators with at least basic technical training to correctly handle the device and interpret results. These barriers may hinder broader adoption in low-resource settings. Finally, while qPCR offers high sensitivity, interpreting positive results without clinical correlation can lead to potential overdiagnosis, especially in cases of latent or past infection. Furthermore, the absence of culture-confirmed cases in our sample precludes any inference about true sensitivity and reinforces that our findings should be interpreted primarily as evidence of feasibility rather than diagnostic accuracy.

4. Methods

This study was designed as a prospective, cross-sectional diagnostic feasibility study conducted under field conditions to evaluate the analytical performance and real-world applicability of a simplified DNA extraction protocol coupled with portable qPCR for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in low-resource and hard-to-reach environments. Sample processing was carried out entirely outside conventional laboratory infrastructure to assess its operational feasibility in true field conditions.

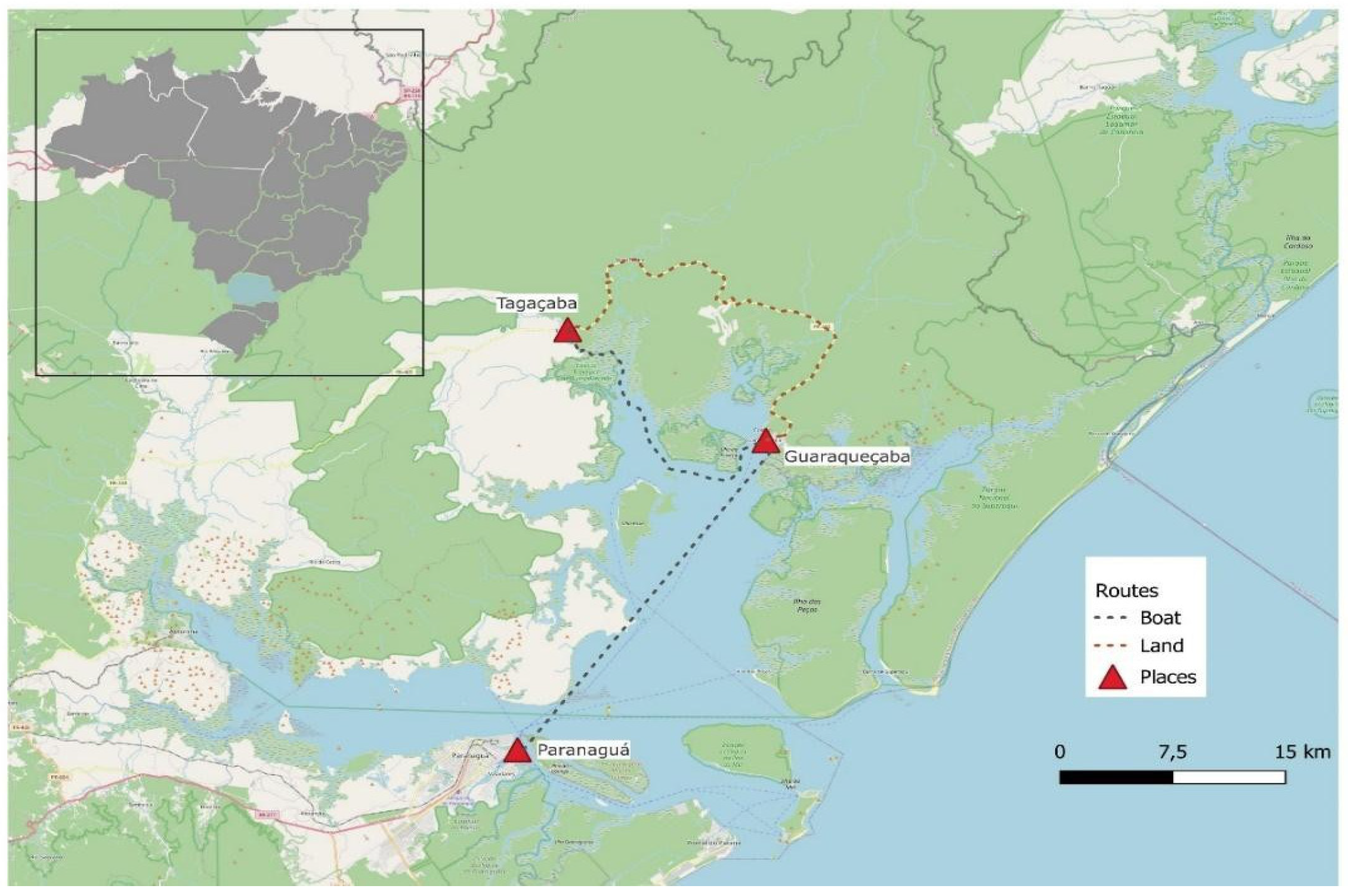

4.1. Samples

A total of 54 samples were analyzed, including both symptomatic individuals and asymptomatic close contacts, collected in two distinct low-resource environments. The first location was the remote village of Tagaçaba, in the municipality of Guaraqueçaba, state of Parana (south of Brazil). Six samples were collected at the patients’ houses by a health agent. They were immediately processed at the local health post, situated in the same remote village just a few meters away. Guaraqueçaba is located inside a preservation area, and the only way to reach it is by using 4x4 off-road vehicles or by boat. During stormy days, the municipality´s connection to the main city of Paranaguá across the bay is cut off. The remote village of Tagaçaba is located a further 90-minute drive from Guaraqueçaba city center, through roads that close during rainy days (

Figure 3).

The second location was the State Penitentiary of Venâncio Aires (PEVA), located in the municipality of Venâncio Aires, state of Rio Grande do Sul (south of Brazil). Forty-eight samples were collected from all individuals in four cells, each housing 12 inmates. At PEVA, both symptomatic and asympto-matic individuals were sampled so that we could also evaluate the close contacts of any possible positive patient. The demographic characteristics of the participants from both collection sites — the remote village of Tagaçaba and the State Penitentiary of Venâncio Aires (PEVA) — are summarized in

Table 2.

Sample collection and processing were carried out on two separate field trips: one to the remote village of Taga-çaba in July 2023, and another to the State Penitentiary of Venâncio Aires (PEVA) in March 2024.

No formal sample size calculation was performed. The number of samples was determined by logistical feasibility and accessibility to field sites during the study period, considering the limitations imposed by infrastructure, transportation, and the availability of local services. This study was therefore conceived as an exploratory, proof-of-concept field validation, with the primary aim of assessing feasibility rather than establishing definitive diagnostic accuracy estimates.

After 24 hours of the first sample collection, a second sputum collection was performed for all study participants for confirmatory testing using the routine services of the health system. Bacilloscopy was performed using the Ziehl-Neelsen method, while culture was performed in Löwnestein-Jensen medium after treatment with sodium lauryl sulfate, according to the Brazilian National Manual for the Laboratory Surveillance of Tuberculosis and other Mycobacteria [

10].

All study procedures were conducted independently. The team responsible for obtaining informed consent was not involved in sample processing or qPCR analysis. The qPCR operators did not have access to participants' clinical information or the results of the reference standard tests. Likewise, the professionals who performed smear microscopy and culture at the routine health facilities were blinded to the index test results. All samples were anonymized using numeric codes, and participant identities were not disclosed to laboratory personnel at any stage of the study. Field operators were aware of the site allocation since the tests were performed directly in the field, and that participant selection was based on the presence of respiratory symptoms or, in the penitentiary, on cell-sharing with symptomatic individuals. Field operators did not have access to individual clinical details or to information indicating which samples belonged to symptomatic or contact participants. To avoid contamination and sample mix-up, each specimen was handled individually, rigorously labeled, and processed using strict identification procedures, preventing any possibility of tube or container interchange.

The study was registered in the Brazilian Registry of Clinical Trials, under the number RBR-288qb6h.

4.2. Simplified DNA Extraction

The simplified protocol was performed as previously described [

7,

9]. A minimum sputum volume of 250 µL was re-quired to proceed with the DNA extraction. Briefly, the method consists of adding a denaturing solution and proteinase K (1 µg/µL) to the sputum, vigorously vortexing at maximum speed, and subsequently applying this mixture onto an FTA Micro Elute card (Whatman®). The cards were left to dry out at room temperature for 60-90 minutes. Next, a 6-mm punch was made using a paper punch, which was collected in a 1.5 mL tube. DNA was eluted from the filter paper by adding TE pH 8.0, vertexing, and incubating at 95°C for 5 minutes. The tube was spun at maximum speed for 3 seconds to pellet the paper punch and filter fibers, providing a cleaner supernatant. Aliquots of the supernatant were collected and immediately used for downstream quantitative PCR (qPCR).

4.3 qPCR

Detection of the IS6110 genomic marker of

M. tuberculosis was performed as previously described [

7,

9]. Since this is a field study, the qPCR was performed in the lightweight and portable Q3-plus instrument, which uses a 6-reaction silicon chip to thermocycle and execute fluorescence-based reactions [

11,

12].

Duplex reactions were performed using the commercial PCR mixture GoTaq Probe qPCR Master Mix (2X) (Promega®, USA) to detect a bacterial and a human target as a reaction control, ensuring the presence of sample DNA. Oligonucleotides for detection of the

M. tuberculosis genomic marker IS6110 were obtained commercially in the Taqman Oligomix format (forward 5’-CAGGACCACGATCGCTGAT-3’, reverse 5’-TGCTGGTGGTCCGAA-3’, and the probe 5’ FAM-TCCCGCCGATCTCG- HQI-3’). Specific oligonucleotides for the detection of the human internal control gene 18S rRNA were used, at 0.2 µM for the forward (18SF 5’ AAACTGCGAATGGCTCATTAAATCA 3’) and reverse 918SR 5’ CCCGTCGGCATGTATTAGCTCT 3’) primers and 0.1 µM for the probe (5’ HEX- TGGTTCCTTT-GGTCGCTCGCTCC-BHQ1 3’) [

13,

14]. The final reaction volume in the Q3-Plus portable equipment was 5 µL, of which 2 µL was DNA. Cycling conditions were as follows: 95˚C/80 sec and 40 x (95˚C/15 sec + 60˚C/1 min). Baseline and threshold were automatically generated by the software. Since the protocol was performed under field conditions and its reproducibility was previously evaluated under laboratory conditions, a single DNA extraction was performed per sample. However, all qPCR reactions were run in duplicate to confirm result reproducibility.

Optical parameters for the FAM channel were defined as an exposure time of 1 second, an LED power of 3, and an analog gain of 15, while for the VIC/HEX channel, the parameters were 2 seconds of exposure time, an LED power of 10, and an analog gain of 15.

The DNA extraction protocol followed by portable qPCR used in this study was previously validated under laboratory conditions [

7] while the chip gelification process was described by Costa et al. [

15]. Both were adapted for use under field conditions in the present study. A separate full study protocol was not registered or made publicly available.

The test positivity cut-off for the index test was pre-specified and defined as any detectable amplification signal for the IS6110 target, in accordance with previously validated protocols. No additional Ct cut-off was applied in this field validation because prior laboratory-based validations of this protocol demonstrated high specificity with the ‘any amplification’ criterion. Introducing an arbitrary Ct threshold under field conditions could have increased the risk of false negatives by excluding true low-level signals. Importantly, because this assay was applied as a screening tool, any detectable amplification is intended to indicate the need for further diagnostic investigation rather than to serve as a standalone diagnosis. Final case confirmation requires integration with additional microbiological testing and clinical assessment. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that late amplification and background noise may contribute to diagnostic ambiguity, and future larger studies should explore the definition of optimized Ct cut-offs for field use.

No changes to the predefined outcome measures were made after the study began. The primary outcome — detection of M. tuberculosis DNA via qPCR — was maintained throughout the study.

In preparation for use in low infrastructure settings, qPCR reagents were pre-loaded onto the Q3-Plus chips and subjected to a gelification process, which renders the qPCR mixture stable at refrigerator temperatures (2 to 8 ºC) instead of freezer temperatures (-15 to -30 °C) for at least 3 months without losing significant efficiency [

12,

13]. In brief, the gelification process substitutes excess water of the qPCR reaction with a gelification mixture consisting of sugars and ly-sine. This mixture is then subjected to vacuum cycles at 30 °C, evaporating the remaining water of the mix, effectively forming a protective matrix around the enzymes and oligonucleotides, allowing them to be stored in refrigerators [

13]. Although the study describing the gelification process did not provide specific reagent pricing, it estimated that eliminating the requirement for cold-chain storage could reduce overall qPCR operational costs by approximately 20%. This cost reduction reflects savings in reagent transport, storage, and energy demands, which are particularly relevant for feasibility in resource-limited environments [

12].

4.4. Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical data, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations. Cycle threshold (Ct) values were reported as mean ± standard deviation. To assess the agreement between molecular and conventional diagnostic methods, Cohen’s Kappa coefficient and its 95% confidence interval were calculated for qPCR and smear microscopy results. Given the small number of positive samples, 95% confidence intervals were computed using a normal approximation, and the limited precision of these estimates is acknowledged. Due to the absence of favorable results in culture-based testing, Cohen’s Kappa could not be calculated for comparison with culture. All analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.2) and the irr package, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

Implementing portable qPCR assays for tuberculosis control in hard-to-reach areas shows considerable potential. Despite challenges related to cost and the minimal infrastructure required, the possibility of conducting rapid and sensitive tests directly in the field may provide a more effective approach to managing tuberculosis in vulnerable populations. Beyond remote settings, this platform could also be adapted to semi-urban or high-density environments, pro-vided that minimal biosafety and training requirements are met. However, scaling up its use in high-burden regions would require careful integration with existing diagnostic networks, cost optimization, and sustainable supply chains. Also, beyond tuberculosis, the platform is being validated in field conditions to help diagnose leprosy and malaria (unpublished results).

It is important to emphasize, however, that qPCR detects genetic material and not necessarily viable bacilli. Therefore, positive results should be interpreted with caution and always correlated with clinical and epidemiological data to distinguish active infection from residual DNA or past disease.

This strategy could therefore contribute to a more agile and efficient public health response, especially when ac-companied by confirmatory testing and medical assessment to ensure diagnostic reliability and appropriate interventions. Ultimately, the portability of the procedure may facilitate the identification of additional individuals positive for TB, helping to reduce community transmission and alleviate the disease burden on society.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Summary and de-identified data for participants with positive qPCR results. Cycle threshold (Ct) values for the 18S and IS6110 targets are presented, as well as basic demographic and clinical variables: age, weight, height, sex, collection site, ethnicity, prior history of tuberculosis, HIV status, presence of neoplasia/cancer, smoking status, smear microscopy results, and presence of clinical symptoms of tuberculosis. These data are included to promote transparency and reproducibility of results. STARD and CONSORT checklists are also provided.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, design, data collection, analysis, and writing of this manuscript. Specific contributions will be detailed according to the CRediT taxonomy at the time of submission.

Funding

This study was financed in part by grant #445954/2020-5 (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq, Chamada #30/2020 – INOVA PROEP/PEC), as well as fellowships offered by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES). The funding agencies had no role in the design of the study, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Oswaldo Cruz Institute (IOC) Research Ethics Committee under protocol number CAAE 44423120.0.1001.5248 on July 27th, 2021. The study is registered at the Brazilian Registry of Clinical Research (ReBEC) under the number RBR-288qb6h. All participants provided written informed consent before sample collection and data use.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to any sample collection. Participants were informed about the purpose of the research, the procedures involved and their right to refuse participation without any consequences. Participation was entirely voluntary.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical constraints to protect participant confidentiality. However, anonymized data can be made available by the corresponding author upon request and subject to Institutional Review Board approval. De-identified summary-level data for qPCR-positive participants, including Ct values and basic demographic/clinical covariates, are presented in

Supplementary Table S1 to enhance transparency and reproducibility.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the teams at the Tagaçaba Basic Health Unit and the Venâncio Aires State Penitentiary for their logistical support and collaboration during field sample collection and processing. We also thank all study participants for their willingness and essential contribution to this work. We acknowledge the institutional support of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) through the Plataforma de Pesquisa Clínica da Vice-Presidência de Pesquisa e Coleções Biológicas da Fiocruz and the “Programa Fiocruz de Fomento à Inovação (INOVA)”, of the University of Santa Cruz do Sul (UNISC), as well as the technical support provided by the BiPOC and NUPESISP research groups. We are also grateful to the State Health Department of Paraná for operational assistance and to the funding agencies that supported the research and innovation phases of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| qPCR |

quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| Ct |

Cycle threshold |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| PEVA |

State Penitentiary of Venâncio Aires |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. 2024.

- Ministério da Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico. 2025. www.gov.br/saude.

- Andrews, J.R.; Liu, Y.E.; Croda, J. Enduring Injustice: Infectious Disease Outbreaks in Carceral Settings. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2024, 229, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Possuelo, L.G.; Ely, K.Z.; Soto, M.M.D.; et al. Health Care for the Population Deprived of Liberty: Overcoming Challenges and Promoting Citizenship. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 2024, 57, e006042024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sequera, G.; Aguirre, S.; Estigarribia, G.; et al. Incarceration and TB: the epidemic beyond prison walls. BMJ Global Health. 2024, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.; Bello, G.L.; Rossetti, M.L.R.; Krieger, M.A.; Costa, A.D.T. Demonstration of a fast and easy sample-to-answer protocol for tuberculosis screening in point-of-care settings: A proof of concept study. PLoS ONE. 2020, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenta, M.D.; Ogundijo, O.A.; Warsame, A.A.A.; Belay, A.G. Facilitators and barriers to tuberculosis active case findings in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2023, 23, 515–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertão-Santos, A.; Dias Lda, S.; Ribeiro-Alves, M.; et al. Validation of the performance of a point of care molecular test for leprosy: From a simplified DNA extraction protocol to a portable qPCR. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2024, 18, e0012032–e0012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares Tdos, S.; Bello, G.L.; dos Santos Petry, I.M.; et al. Laboratory validation of a simplified DNA extraction protocol followed by a portable qPCR detection of M. tuberculosis DNA suitable for point of care settings. Ahmed S, ed. PLOS ONE. 2024, 19, e0302345–e0302345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Saúde. National Manual for the Laboratory Surveillance of Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacteria. 2008. http://www.saude.gov.br/bvs.

- Cereda, M.; Cocci, A.; Cucchi, D.; et al. Q3: A compact device for quick, high precision qPCR. Sensors (Switzerland). [CrossRef]

- Rampazzo, R.C.P.; Graziani, A.C.; Leite, K.K.; et al. Proof of Concept for a Portable Platform for Molecular Diagnosis of Tropical Diseases: On-Chip Ready-to-Use Real-Time Quantitative PCR for Detection of Trypanosoma cruzi or Plasmodium spp. Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2019, 21, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manta, F.S.D.N.; Leal-Calvo, T.; Moreira, S.J.M.; et al. Ultra-sensitive detection of Mycobacterium leprae: DNA extraction and PCR assays. Poonawala H, ed. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2020, 14, e0008325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manta, F.S.D.N.; Jacomasso, T.; Rampazzo, R.D.C.P.; et al. Development and validation of a multiplex real-time qPCR assay using GMP-grade reagents for leprosy diagnosis. Adams LB, ed. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2022, 16, e0009850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.D.T.; Amadei, S.S.; Bertão-Santos, A.; Rodrigues, T. Ready-To-Use qPCR for Detection of DNA from Trypanosoma cruzi or Other Pathogenic Organisms. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2022, 2022, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.R.; Rabahi, M.F.; Sant’Anna, C.C.; et al. Consenso sobre o diagnóstico da tuberculose da sociedade brasileira de pneumologia e tisiologia. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia. 2021, 47, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busatto, C.; Bierhals, D.V.; Vianna, J.S.; Silva, P.E.A.D.; Possuelo, L.G.; Ramis, I.B. Epidemiology and control strategies for tuberculosis in countries with the largest prison populations. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2022, 55, e0060-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simões, M.; Castro, R. Pesquisa mostra impacto do encarceramento na epidemia da tuberculose na América Latina. https://fiocruz.br/noticia/2024/10/pesquisa-mostra-impacto-do-encarceramento-na-epidemia-da-tuberculose-na-america. Published online 2024.

- Valença, M.S.; Possuelo, L.G.; Cezar-Vaz, M.R.; da Silva, P.E.A. Tuberculose em presídios brasileiros: Uma revisão integrativa da literatura. Ciencia e Saude Coletiva. 2016, 21, 2147–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).