1. Introduction

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, TB and COVID-19 have been among the leading causes of death from a single infectious agent,[

1] with TB reclaiming the top position in 2023 [

2]. Health service disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic, impacted care of people with TB and caused a global decline in TB testing and diagnosis [1, 3, 4].

TB recovery plans aim to address the impact of COVID-19 by finding "missing" TB patients, ensuring linkage to care for those diagnosed, and strengthening retention into care and TB prevention. For South Africa (SA), the TB Recovery plan [5, 6] includes Targeted Universal Testing for TB (TUTT) [

7] which tests individuals in three high-risk groups including contacts of individuals with active disease, individuals with recent TB diagnosis (last two years) and people living with HIV (PLHIV); this was trialed immediately before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in SA, demonstrating that intervention clinics had a 17% relative increase in TB patients diagnosed per month compared to non-intervention clinics, taking into account secular reductions in TB diagnoses [

8].

Previously, diagnosis of TB, in SA, relied on passive, self-presentation of individuals with symptoms at health care facilities (HCFs) [

9]. The WHO-recommended four-symptom screen (W4SS) for TB [

10] was primarily used to identify individuals for further investigation – in most instances this would be sputum collection, subjected to molecular WHO-approved rapid diagnostic tests (mWRDs) for TB [

10]. The problem with this approach is that up to half of all TB cases are asymptomatic (bacteriologically unconfirmed TB), potentially contributing to transmission [

11]. Active, community or facility-based interventions such as the TUTT approach are therefore crucial in identifying additional TB cases. However, their implementation was impacted during COVID-19 due to restrictions on movement; reduced collection of sputum, and symptoms common to TB and COVID-19: making it difficult to distinguish pathogens without testing [12, 13]. Typically, upper respiratory specimens such as nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs are used for SARS-CoV-2 detection whereas for TB, sputum is required for molecular testing and sputum culture remains the gold standard for TB diagnosis [

14]. Whilst the interaction between TB and COVID-19 is still being investigated, studies suggest that TB status and history might play a role in the development and progression of COVID-19 infection [15, 16]. Furthermore, TB disease is reported to be more common among patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection than in those with bacterial or other viral infections [

13]. SARS-CoV-2 infection has also been shown to mask or intensify TB infection with potential severe consequences [

17].

In early 2021, to minimise and reverse the impact of COVID-19 on TB diagnosis, USAID and Stop TB Partnership recommended simultaneous testing for COVID-19 and TB in high TB burden countries, using a NP swab and sputum for individuals presenting with respiratory symptoms [

18]. Simultaneous rapid molecular testing for TB and SARS-CoV-2 has the advantage of reducing transmission of both pathogens in the community and HCFs [

19]. This approach was piloted at five HCFs in the Greater Accra Region in Ghana and demonstrated the potential of improving case detection for both COVID-19 and TB [

20].

We previously conducted a small pilot study to assess the feasibility of detecting both SARS-CoV-2 and

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) from a single sputum, demonstrating that both pathogens can be successfully detected from the same specimen [

21]. In this larger study, we attempted to confirm the utility of testing a single sputum for both pathogens collected from symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals presenting at primary health care clinics (PHCH) and who under routine conditions at the time would have been tested for SARS-CoV-2 only. Concordance of SARS-CoV-2 detection using the sputum swab capture method was assessed by comparing its results with those obtained from routine PCR testing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample size

Previous findings in SA showed that around 1.2% of patients with symptoms requiring a SARS-CoV-2 test were positive for MTBC using Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Ultra) assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), about double the general TB prevalence in Gauteng. With decreasing COVID-19 cases and an assumed difference of 0.09, we estimated enrolling at least 1,000 participants, yielding around ninety TB patients and at least two hundred COVID-19 patients, depending on a potential fourth COVID-19 surge.

2.2. Participant recruitment

Recruitment occurred between November 2021 and June 2022. Adults (>18 years) attending two large PHCHs in Soweto, Johannesburg, SA were invited to enroll in the study. Both clinics, at the beginning of recruitment, had a respiratory queue where patients with respiratory symptoms had an NP swab taken for routine testing for SARS-CoV-2. This changed over time and close to the end of the study, patients required a doctor’s confirmation for testing for SARS-CoV-2. Inclusion criteria included individuals with respiratory symptoms awaiting a public sector SARS-CoV-2 molecular test or those belonging to a high risk for TB group. All participants had the same data collected, detailing their symptoms, and including both their W4SS and upper respiratory and constitution symptoms (

Table S1: Symptoms reported by participants). Anthropometrics and vital signs were also captured.

2.3. Specimen collection

Once informed consent was obtained, one NP swab, one tongue swab (TS), ~3mL saliva and ~4mL sputum were collected from each participant. Sputum and saliva were collected in the open (away from other participants and patients) under the supervision of a study staffer who remained at least 2 meters away from the participant and wore appropriate protective personal equipment.

2.4. Specimen testing

2.4.1. Nasopharyngeal swabs

Each participant’s NP swab was sent to the routine National Health Laboratory Service, or if NP SARS-CoV-2 testing was not indicated by current policy, to the research laboratory in Braamfontein, Johannesburg for SARS-CoV-2 testing. Assays used for routine testing included: Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 (Xpress) (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA); cobas® SARS CoV-2 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland); Allplex™ SARS-CoV-2 (Seegene, Seoul, South Korea) and TaqPath™ COVID-19 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.4.2. Sputum

Sputum was sent to the research lab for MTBC investigation using Ultra and for SARS-CoV-2 detection using the Xpress assay, using a swab capture method, previously described [21, 22]. Briefly, nylon flocked swabs were inserted into sputum, twirled around and any material collected on the swab was re-suspended in phosphate buffer (PB). The eluate was tested for SARS-CoV-2. Xpress results were compared to routine PCR and only specimens with valid results were included in the analysis. Concordance between the Xpress assay and routine PCR was assessed using percent agreement and the kappa statistic using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Residual sputum was tested on the Ultra, as per manufacturer instructions.

2.4.3. Saliva and tongue swabs

Saliva and tongue swabs were stored for future testing.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

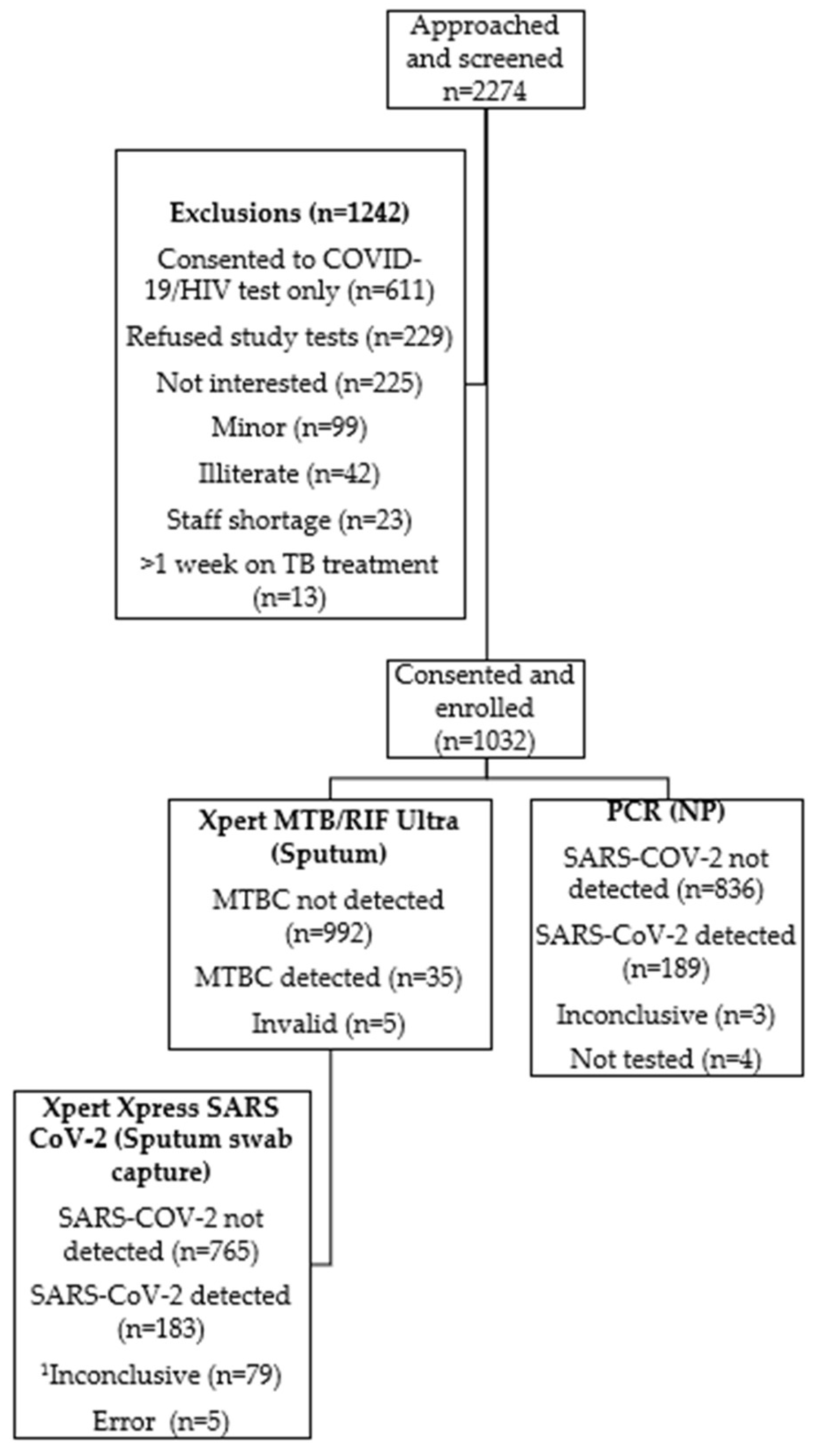

A total of 2274 individuals were screened for enrolment and informed consent was obtained from 1032 participants (

Figure 1). Participants mean age was 41 years (interquartile range, 18-84 years) (

Table 1); 45% were male and 24% were PLHIV. Participant enrolment was similar between the two study sites but participants from one site had longer duration of symptoms prior to seeking healthcare (up to 62 days). At least 90% of PLHIV recruited were receiving antiretroviral (ARV) therapy at study enrolment. Hypertension was the most common co-morbidity reported (16%) by participants across both sites. Cough was the most common symptom reported (94%). There were 15/1032 (1.5%) participants who, despite not reporting having, had elevated random glucose levels.

HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus; MTBC, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex; NP, nasopharyngeal swab; PCR, polymerase chain reaction, Xpert Xpress SARS CoV-2 is used for detection of SARS CoV-2 in upper respiratory specimens; Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra is used for the detection of MTBC and rifampicin-resistance associated mutations from respiratory specimens, PCR for SARS CoV-2 is used for detection of SARS CoV-2 in respiratory specimens; 1Inconclusive result determined using National Health Laboratory Services algorithm

3.2. TB and drug-resistant TB

A total of 35/1032 (3.4%) participants had bacteriological confirmation of TB using Ultra (

Figure 1 and

Table 2). Among these 35 individuals, 34 (97.1%) reported respiratory symptoms. Among the 35 participants, 16 (45.7%) were considered to be in at least one high-risk for TB groups; three experienced a previous episode of TB, three were in contact with a person diagnosed with TB, and ten were HIV-positive. Furthermore, 7 participants (20%) had Rif resistance detected on Ultra. Five specimens produced unsuccessful results.

3.3. COVID-19 routine PCR results

A total of 189/1028 (18.4%) participants tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 using routine PCR (

Figure 2). Of these, 8/189 (4.2%) were asymptomatic. Symptom duration among participants ranged from 1- 38 days. Cough and headache accounted for >80% of symptoms reported. Hypertension was the most common co-morbidity reported by 33/189 (17.5%) participants. Results were unavailable for four participants due to either missing specimens or laboratory rejection. Three specimens produced inconclusive results.

Xpert Xpress SARS CoV-2 is used for detection of SARS CoV-2 in upper respiratory specimens; Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra is used for the detection of MTBC and rifampicin-resistance associated mutations from respiratory specimens, SARS CoV-2 test is used for detection of SARS CoV-2 in respiratory specimens

3.4. Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 results

Of the 1032 participants, 183 (18%) were positive for SARS-CoV-2 using the Xpress sputum swab capture method (

Table 2). Cough was the leading symptom reported by 155/171 (91%) participants. The average duration of symptoms reported for this cohort is 4.7 days (range: 1-38 days). Fifteen participants reported having a previous TB episode. Five specimens produced unsuccessful results. A total of 79/1032 (8%) results were recorded as inconclusive (as per National Health Laboratory Services (NHLS) reporting where a single E or N2 gene has a Ct >38 or where both E and N2 genes has Ct >40 (internal memo Dr M.P. da Silva)). Of the 941 participants which demonstrated valid results for the Xpress assay and routine PCR, 869 (92%) (

Table 3) showed substantial agreement between the two assays (Kappa: 0.755).

Xpert Xpress SARS CoV-2 is used for detection of SARS CoV-2 in upper respiratory specimens, SARS CoV-2 test is used for detection of SARS CoV-2 in respiratory specimens

3.5. TB/SARS-CoV-2 co-infection

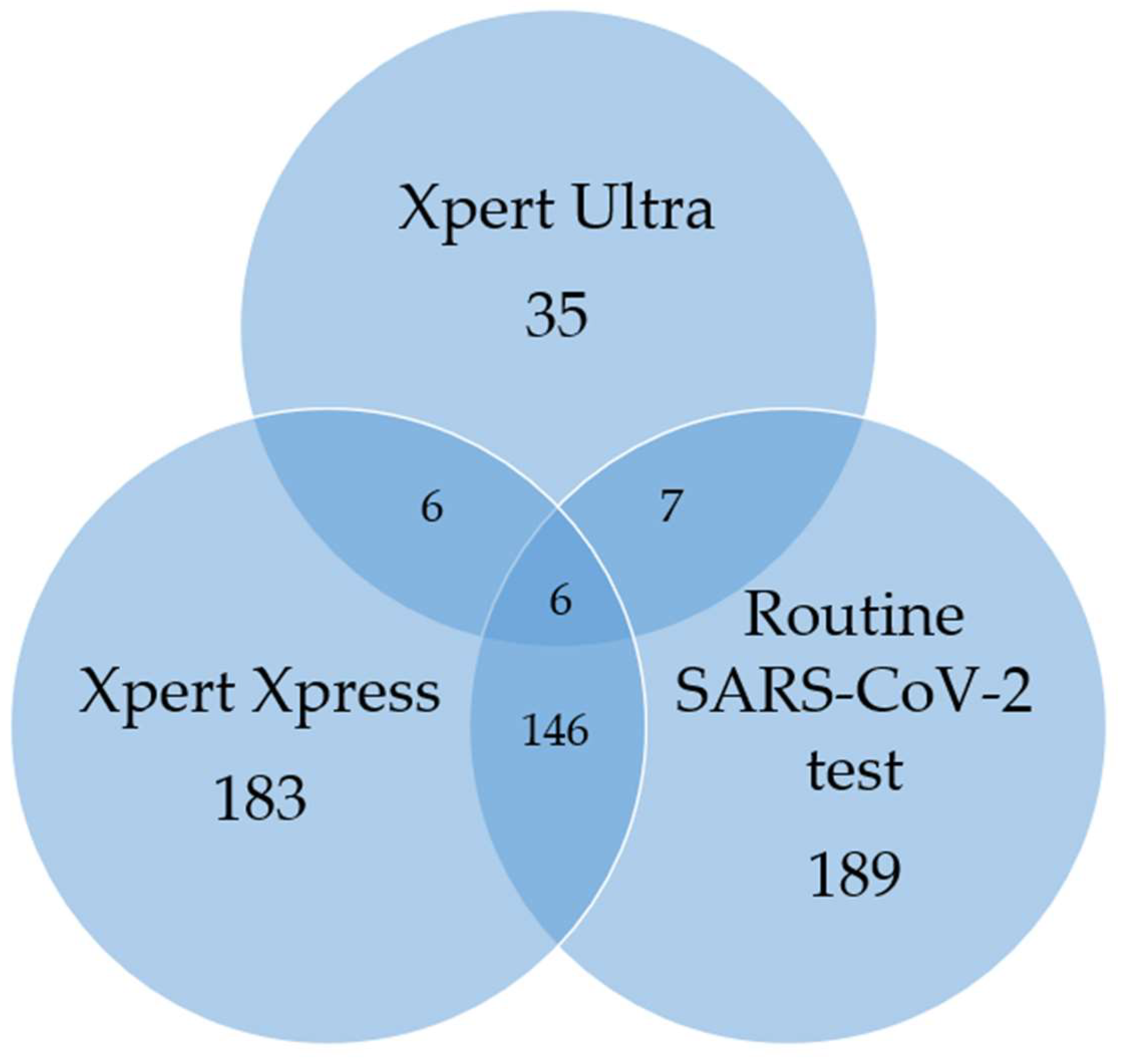

A total of 10/1032 (4%) had both MTBC, and SARS-CoV-2 detected, either on routine PCR or the Xpress sputum capture method (

Table 2 and

Figure 2). None of these ten co-infected participants were contacts of people with active TB or reported a previous TB episode. Of the ten individuals, 9 (90%) had not received a COVID-19 vaccine. In addition, 5/10 (50%) were HIV-positive. All participants reported respiratory symptoms for an average duration of 9.6 days.

4. Discussion

In this study, bi-disease testing for COVID-19 and TB was investigated using a single sputum from each participant. The Xpress assay detected SARS-CoV-2 in a similar proportion of cases as routine PCR (17.7% vs. 18.3%). There was substantial agreement between routine PCR and Xpress, suggesting that the swab capture method is reliable for COVID-19 diagnosis. MTBC was detected in 3% of participants and 1% of participants demonstrated dual detection of MTBC and SARS-CoV-2.

Participant recruitment coincided with SA's fourth and fifth COVID-19 waves, when ~99% of sequenced specimens were identified as the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 [23, 24]. Other than cough and headache which accounted for the majority of symptoms reported, common symptoms included sore throat, fatigue, nasal congestion/runny nose and self-reported fever/chills each accounting for ≥35% of symptoms which is consistent with the most common Omicron symptoms reported at that time [

25]. Most participants seeking health care did so within days of symptom onset. Since diabetes is among five key drivers of the global TB epidemic [

3], this prompted assessment of participant glucose levels. Although various factors can influence random glucose levels, 15 participants exhibited elevated glucose levels, which may increase their risk of developing TB.

There were 37 participants where SARS-CoV-2 was detected by Xpress but not by routine PCR. Findings by Marais et al. (2021) [

26] indicate that SARS-CoV-2 detection in the early stages of infection (0–3 days) is more reliable in oral samples than in nasal samples, particularly for the Omicron variant. Since 43% of participants presented to the HCF within three days of symptom onset, this may explain the detection of the virus in sputum but not in NP specimens. These findings highlight the potential advantage of testing oral specimens in individuals presenting to healthcare facilities shortly after symptom onset. Another factor for consideration is the S-gene target failure observed with the TaqPath™ COVID-19 assay during the study period, which likely contributed to reduced assay sensitivity [

27]. Notably, this assay was most used for routine PCR testing in Gauteng. This study focused on dual testing for TB and COVID-19, screening for other common seasonal pathogens, such as influenza, was not performed.

For the 35 participants in whom SARS-CoV-2 was detected by routine PCR but not by Xpress, one possible explanation is a known issue with the Xpress assay sensitivity due to delayed PCR hybridization due to a 1% drop in E-gene coverage [

27].

As per the NHLS algorithm, specimens with Ct values close to the cut-off and meeting certain criteria were treated with caution and reported as ‘inconclusive’ rather than positive. This classification applied to 8% of study participants. Although these tests were not repeated in this study, the swab capture method allows for repeat testing if sputum is still available.

Of the 35 participants with MTBC detected, 15 were diagnosed during the fourth and fifth COVID-19 waves. During these peaks, most HCFs only referred patients for further diagnostics if they tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 and returned to facility if still unwell. Given their COVID-19 symptoms, these participants likely would not have been tested for TB and would have remained undiagnosed, had they not been enrolled in this study. A notable portion of the TB-diseased population belonged to high-risk for TB groups, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions and effective management strategies for these individuals. Additionally, 7/35 (20%) were found to be RIF-resistant and although the sample size is small, this is higher than the reported estimated SA RIF-resistance rate of up to 4.3% [

28].

It has been suggested that individuals with COVID-19 and concurrent or history of TB have an approximately two-times greater risk of hospital-based mortality than those without TB [

29]. For the ten participants who were found to be TB/SARS-CoV-2 co-infected in this study, it is likely that the risk of hospitalization and mortality was low due to the reduced clinical severity of the Omicron variant. [

30] For symptomatic participants, 75% sought care within 10 days of symptom onset which translates to earlier diagnosis and management of both diseases. Ninety percent of co-infected participants were unvaccinated, which potentially increased their risk of contracting COVID-19. None had prior TB, suggesting SARS-CoV-2 may have triggered latent TB to progress to active disease or accelerated its progression as reported in previous studies. [31, 32] However, since both diseases were diagnosed simultaneously, the possibility also exists that these individuals first contracted TB, remained undiagnosed due to disrupted TB services [

33] and later contracted COVID-19.

Initiatives such as TUTT, which were already being investigated pre-COVID-19, demonstrated that under-diagnosis of TB is a reality. Active case finding strategies are therefore critical. A similar initiative to TUTT, called "Tuberculosis Neighborhood Expanded Testing" or TB NET, [

34] was launched by Médecins Sans Frontières and the City of Cape Town. This initiative screened households near index TB cases by requesting individuals to self-collect and drop off sputum at dedicated community points for TB testing. Despite challenges like household refusal to participate due to stigma and a low return rate of sputum jars (151/1400), the program achieved a 7.9% TB positivity rate among those tested.

Another factor to consider is the availability of instruments that can perform multi-disease testing (sequential or simultaneous testing of multiple infectious agents), such as the GeneXpert system used in this study. The concept of multi-disease testing was already identified by WHO in 2018 as an essential step to not only simplify the diagnosis of infectious diseases but also crucial to end pandemics [

35]. Bi-disease testing has been used previously for HIV and TB [

36] and for COVID-19 and TB [

20] but not using a single specimen. These initiatives require resources, time, and effort in addition to investigations into which specimen collection methods, areas (community based and/or targeted screening at HCF) and diagnostics will be most effective but if they assist with finding the “missing millions” and with stopping the TB epidemic, post COVID-19, more of these active case finding programs should be implemented.

While the WHO COVID-19 dashboard (

https://covid19.who.int, date last accessed 30 January 2025) indicates a decrease in COVID-19 cases, this research emphasizes the significance of conducting tests for multiple diseases, especially during a pandemic when resources are limited and focused away from “routine” testing programmes.

5. Conclusions

The study findings underscore a substantial identification of TB and Rifampicin-resistant TB that would have been missed without a bi-disease testing approach. The swab capture method was also shown to be reliable for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Additionally, this approach demonstrates the feasibility of utilizing a single specimen on an analyzer with multiplexing capabilities. Implementation of such an innovative approach should be taken into consideration, not only for patient management but also for future pandemic preparedness.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Table S1: Symptoms reported by participants

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Anura David, Lesley Scott and Neil Martinson; Data curation, Anura David; Formal analysis, Anura David; Funding acquisition, Lesley Scott and Wendy Stevens; Investigation, Anura David and Lyndel Singh; Methodology, Anura David and Lesley Scott; Project administration, Lesley Scott and Wendy Stevens; Resources, Leisha Genade and Neil Martinson; Supervision, Lyndel Singh; Validation, Anura David; Visualization, Anura David and Neil Martinson; Writing – original draft, Anura David; Writing – review & editing, Anura David, Leisha Genade, Lesley Scott, Pedro Da Silva, Lyndel Singh, Wendy Stevens and Neil Martinson. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, grant number OPP1171455.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 210908B and date of approval 25 October 2021. The trial was registered with the South African National Clinical Trials Registry (DOH-27-072022-8705).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Participants who consented to be in the study, the management and staff of the Chiawelo Community Health Centre and Mofolo Community Health Centre that hosted study staff, the Johannesburg Health District and National Department of Health, WitsDIH TB lab staff, Trish Kahamba.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TB |

tuberculosis |

| MTBC |

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex |

| Xpress |

Xpert Xpress SARS CoV-2 |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| TUTT |

Targeted Universal Testing for TB |

| PLHIV |

people living with HIV |

| HCFs |

health care facilities |

| W4SS |

WHO-recommended four-symptom screen |

| WHO |

World Health Organisation |

| mWRDs |

WHO-approved rapid diagnostic tests |

| NP |

nasopharyngeal |

| PHCH |

primary health care clinics |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| TS |

Tongue swab |

| ARV |

antiretroviral |

| |

|

References

- Global Tuberculosis Report 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/97892400370212021 (accessed on 04 May 2022).

- Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024 (accessed on 04 November 2024).

- Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061729 (accessed on 19 November 2022).

- Global Tuberculosis Report 2023. World Health Organization; Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240083851 (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- South Africa TB Recovery plan to mitigate the impact of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Recovery_Plan_South_Africa_FINAL-remediated.pdf (accessed on 05 November 2022).

- National TB Recovery Plan 2.0. 2023. Available online: https://tbthinktank.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/TB-Recovery-Plan-2.0-April-2023-March-2024.pdf (accessed on 03 September 2024).

- Martinson NA, Nonyane BAS, Genade LP, Berhanu RH, Naidoo P, Brey Z, et al. Evaluating systematic targeted universal testing for tuberculosis in primary care clinics of South Africa: A cluster-randomized trial (TheTUTT Trial). PLoS Med. 2023, 20: e1004237. [CrossRef]

- Martinson N, Nonyane B, Genade L, Berhanu R, Naidoo P, Brey Z, et al. A Cluster Randomized Trial of Systematic Targeted Universal Testing for Tuberculosis in Primary Care Clinics of South Africa (The TUTT Study). Preprint in the The Lancet. 2021.

- South African National Department of Health. National Tuberculosis Management Guidelines. Available online: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/elibrary/national-tuberculosis-management-guidelines (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Module 2: Systematic screening for tuberculosis disease, WHO consolidated guidelines on Tuberculosis. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022676 (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Frascella B, Richards A, Sossen B, Emery J, Odone A, Law I, et al. Subclinical tuberculosis disease - review and analysis of prevalence surveys to inform definitions, burden, associations, and screening methodology. Clin Infect Dis. 2021, 73:e830-e41. [CrossRef]

- Patterson B, Bryden W, Call C, McKerry A, Leonard B, Seldon R, et al. Cough-independent production of viable Mycobacterium tuberculosis in bioaerosol. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2021, 126:102038. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Prasad R, Gupta A, Das K, Gupta N. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 and pulmonary tuberculosis: convergence can be fatal. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2020,22. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, YJ. Diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: recent advances and diagnostic algorithms. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2015, 78:64-71. [CrossRef]

- Visca D, Ong CWM, Tiberi S, Centis R, D’Ambrosio L, Chen B, et al. Tuberculosis and COVID-19 interaction: A review of biological, clinical and public health effects. Pulmonology. 2021, 27:151-65. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Yu Y, Fleming J, Wang T, Shen S, Wang Y, et al. Severe COVID-19 cases with a history of active or latent tuberculosis. Int J TB Lung Dis. 2020, 24:747-749. [CrossRef]

- Sy KTL, Haw NHL, Uy J. Previous and active tuberculosis increases risk of death and prolongs recovery in patients with COVID-19. Infect Dis. 2020, 52:902-7. [CrossRef]

- Simultaneous, integrated diagnostic testing approach to detect COVID-19 and TB in high TB burden countries. Available online: http://www.stoptb.org/assets/documents/covid/COVID-TB%20Testing%20Simultaneous_March%202021.pdf. (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Glogowska A, Przybylski G, Bukowski J, Zebracka R, Krawiecka D. TB and COVID-19 co-infection in a pulmonology hospital. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2023, 27:574-7. [CrossRef]

- Adusi-Poku Y, Wagaw Z, Frimpong-Mansoh R, Asamoah I, Sorvor F, Afutu F, et al. Bidirectional screening and testing for TB and COVID-19 among outpatient department attendees: outcome of an initial intervention in Ghana. BMC Infect Dis. 2023, 17:236. [CrossRef]

- Genade L, Kahamba T, Scott L, Tempia S, Walaza S, David A, et al. Co-testing a single sputum specimen for TB and SARS-CoV-2. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2023, 1:146-7. [CrossRef]

- Kahamba T, David A, Martinson N, Nabeemeeah F, Zitha J, Moosa F, et al. Dual detection of TB and SARS CoV 2 disease from sputum among in patients with pneumonia using the GeneXpert ® system. In Proceedings of The Union, 52nd World Conference on Lung Health, virtual, 19-22 October 2021.

- Network for Genomics Surveillance in South Africa. SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance update. Available online: https://www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Update-of-SA-sequencing-data-from-GISAID-14-Jan-2022_dash_v2-Read-Only.pdf (accessed on 07 November 2022).

- Network for Genomics Surveillance in South Africa. SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance update. Available online: https://www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Update-of-SA-sequencing-data-from-GISAID-24-June-2022.pdf. (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Lacobucci, G. Covid-19: runny nose, headache and fatigue are commonest symptoms of omicron, early data show. BMJ. 2021, 375:n3103. [CrossRef]

- Marais G, Hsiao N, Iranzadeh A, Doolabh D, Enoch A, Chu C, et al. Saliva swabs are the preferred sample for Omicron detection. medRxiv. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Scott LE, Hsiao N, Dor G, Hans L, Marokane P, da Silva MP, et al. How South Africa Used National Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values to Continuously Monitor SARS-CoV-2 Laboratory Test Quality. Diagnostics. 2023, 13:2554. [CrossRef]

- South African tuberculosis drug resistance survey 2012–14: National Institute for Communicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.nicd.ac.za/assets/files/K-12750%20NICD%20National%20Survey%20Report_Dev_V11-LR.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Dheda K, Perumal T, Moultrie H, Perumal R, Esmail A, Scott A, et al. The intersecting pandemics of tuberculosis and COVID-19: population-level and patient-level impact, clinical presentation, and corrective interventions. Lancet Respir Med. 2022, 10:603-22. [CrossRef]

- Jassat W, Karim S, Mudara C, Welch R, Ozougwu L, Groome M, et al. Clinical severity of COVID-19 in patients admitted to hospital during the omicron wave in South Africa: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2022, 10:e961-69. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Prasad R, Gupta A, Das K, Gupta N. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 and pulmonary tuberculosis: convergence can be fatal. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2020, 90. [CrossRef]

- Luke E, Swafford K, Shirazi G, Venketaraman V. TB and COVID-19: An Exploration of the Characteristics and Resulting Complications of Co-infection. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2022, 14:6. [CrossRef]

- Karim Q, Baxter C. COVID-19: Impact on the HIV and Tuberculosis Response, Service Delivery, and Research in South Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2022, 19:46-53. [CrossRef]

- Zokufa N, Lebelo K, Hacking D, Tabo L, Runeyi P, Malabi N, et al. Community-based TB testing as an essential part of TB recovery plans in the COVID-19 era. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2021, 25:406-8. [CrossRef]

- Multi-disease diagnostic landscape for the integrated management of HIV, HCV, TB and other co-infections. Available online: https://unitaid.org/assets/multi-disease-diagnostics-landscape-for-integrated-management-of-HIV-HCV-TB-and-other-coinfections-january-2018.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Ndlovu Z, Fajardo E, Mbofana E, Maparo T, Garone D, Metcalf C, et al. Multidisease testing for HIV and TB using the GeneXpert platform: A feasibility study in rural Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2018, 2:e0193577. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).