3. Results

TLK1 is implicated in resistance to multiple DNA damaging agents including UV and cisplatin. By phosphorylating its substrates (e.g., NEK1, RAD54 and ASF1), TLK1 plays roles in resistance to a number of DNA damaging agents, including ionizing radiation (IR), UV and CPT [

16,

17,

18,

19]. We recently synthesized a specific and potent TLK1 inhibitor (J54) [

20], and tested its usefulness in conferring resistance to different genotoxins [

21,

22]. Notably, J54, through inhibition of TLK1>Rad54-promoted HRR, resulted in synthetic lethality (SL) with CPT-induced ICLs that are typically repaired via TC-NER intermediates [

22]. This prompted us to test the SL potential of J54 with UV.

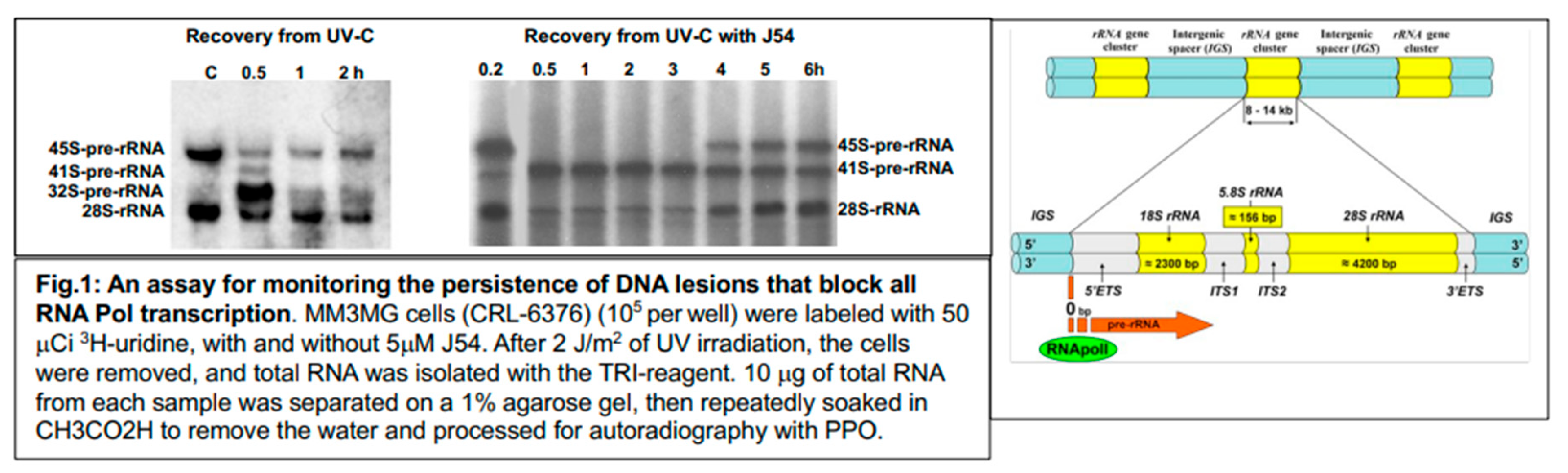

It is well known that UV damage, via formation of Cyclo-Pyrimidine Dimers (CPDs), arrests transcription progress of both PolII and PolI RNA polymerases [

23]. The cryo-EM structure of an RNA Polymerase I (Pol I) stalled at a cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) lesion has been solved at a resolution of 3.6 Å and provides the molecular mechanism for Pol I stalling in the presence of UV light-induced DNA damage[

24]. Therefore, recovery of transcription of the 45S rRNA precursor is an indirect but reliable indicator for completion of repair of DNA lesions that block transcription [

23]. We have thus determined the recovery of 45S rRNA transcription after UV exposure in cells simultaneously treated with J54 (

Figure 1). Notably, cells exposed only to UV recovered transcription of the 45S rRNA precursor after about 2h, and also recovered the rapid processing of the 32S precursor that was also interrupted, indicating the ability to restore the final processing of pre-existing intermediates. In contrast, in cells simultaneously exposed to UV and J54, recovery of transcription did not occur until the 4

th hour; processing was evidently arrested at the earlier 41S to 32S cleavage step [

25]; and the residual 41S intermediates escaped further processing even after transcription by PolI recovered. In fact, it is likely that the newly accumulated 28S rRNAs after 4 hours of recovery in presence of J54 derive entirely from newly transcribed and processed 45S pre-RNA species. We should point out that this recovery of rRNA transcription and processing is in fact a mechanism of

bona fide TC-NER, and that we previously reported that TLK1 was heavily localized to foci in the nucleoli after IR [

21]. Since the heterochromatic and tightly clustered rRNA genes are more difficult and lengthier to repair, and hyper-autophosphorylation of TLKs was recently reported to negatively regulate their permanence at the DNA damage sites [

26], it is tempting to speculate that their persistence in the nucleoli at damaged rRNA genes portends their critical importance in recovering stalled PolI-dependent transcription and processing. Additionally, it was reported that in HeLa cells,

TLK loss increased chromatin accessibility at heterochromatic regions and caused spurious transcription of silenced repetitive elements [

27], which we can now suggest may be another key role in orchestrating the precisely initiated and coordinated transcription of the rRNA genes clusters (cartoon on right reproduced from [

28])

while suppressing aberrant events.

The fact that inhibiting TLK1 may delay the recovery of PolI transcripts, as well as precursor rRNA processing, is not that surprising per se, but the question is what might the mechanism be? Our working hypothesis is that this is the result of reduced ERCC6/CSB activity dependent on the TLK1>NEK1>ERCC6 axis. In fact, it is important to point out that there is strong evidence that CSB is a critical component of PolI transcription [

29,

30] as well as its more established roles [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35] in TC-NER when PolII is arrested at CPD lesions of ‘protein-coding’ genes.

Nek1 and ERCC6 specific interaction as possible reason for TLK1-mediated UV resistance. The TLKs are known to play important roles in DNA repair (rev in [

36]), and one of the earliest reports described the activity of overexpressed TLK1B in promoting more rapid removal of CPDs (determined with an antibody detection or accessibility to CPD-specific T4-nucleaseV) and conferring greatly increased viability [

37]. However, the direct regulated target(s), or interactors, of TLK1 that play this role in repair of CPDs remained unknown [

38], except for the possible indirect involvement of APEX that was implicated in some aspects of UV-damage repair [

39].

However, we knew that a key regulatory function of TLK1 is as an activator of the important kinase NEK1 through its phosphorylation at T141 in the ‘activation loop’ [

38]. Nek1 derives its name from the founding member of the NIMA (

Never

in

Mitosis Gene

A) family of protein kinases that was originally identified in

Aspergillus nidulans as a kinase essential for mitosis [

40], and expression of a dominant-negative mutant of NIMA results in G2 arrest in vertebrate cells [

41].

NIMA related kinases (NEKs) have adapted to a variety of cellular functions in addition to mitosis [

42]. In human cells, 11 NEKs were identified that are involved in several functions. For example, NEK2 is critical for centrosome duplication [

42], whereas NEK6, 7, 9 are regulators of the mitotic spindle and cytokinesis [

43]. NEK1, NEK4, NEK8, NEK10 and NEK 11 have been linked to the DNA damage response (DDR) and DNA repair pathways as well as ciliogenesis [

42]. NEK1 mediates Chk1 activation likely by modulating the ATRIP/ATR interaction and activity [

44], and this was reported as its main role in participating in the DDC (DNA Damage Checkpoint). However, NEK1 may also play more direct roles in DNA repair that could be a leading cause in its implied etiology in ALS. Following DNA damage induction,

NEK1-ALS motor neurons and NEK1 knockdown cells exhibit accumulation of γH2AX over time, indicating a lack of DNA repair [

45].

The NEK1 interactome, while probably incomplete, was reported [

46] and revealed several proteins that are known to be involved in DNA repair, but none particularly related to UV-damage repair. However, its paralog NEK4 revealed, via a MS proteomic screen, its own direct interaction with ERCC6/CSB [

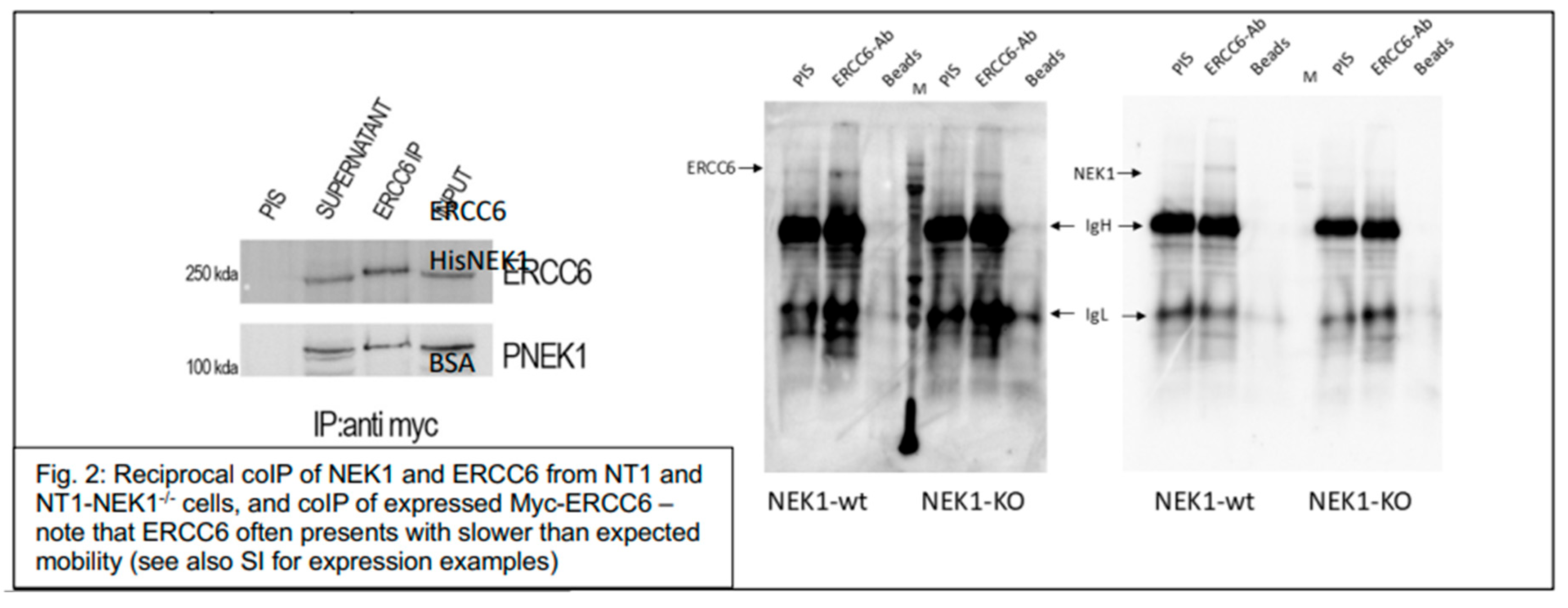

47]. We thus decided to test if NEK1 also interacted with ERCC6 and whether it might be a suitable substrate. Indeed, a pulldown of NEK1 co-immunoprecipitated also ERCC6 and the reciprocal occurred, but not in cells with Nek1-KO (

Figure 2), revealing high specificity for the interaction, despite the weak rendering of the WBs owing to the low abundance of the two proteins at the normal endogenous level. When Myc-ERCC6 was overexpressed in Hek293 cells, the coIP revealed strong intracellular interaction. Moreover, they readily associate in vitro when purified as recombinant proteins. In

Figure 3, we carried out a copurification of ERCC6 (Origene) and recombinant His-NEK1 isolated from bacteria, both at 0.1µg/µl. HisNEK1 was readily associated with ERCC6 after repurification on Ni-Sepharose, whereas competitor BSA showed no appreciable association with it. The fraction of ERCC6 retained (indirectly) by the resin was in excess of the unbound fraction. In contrast, ERCC6 was quantitatively bound by resin, while none of BSA was. Beside confirming their physical interaction in vitro, and resulting in the phosphorylation of key residues in the ‘hydroxy patch’ in IVK reactions (

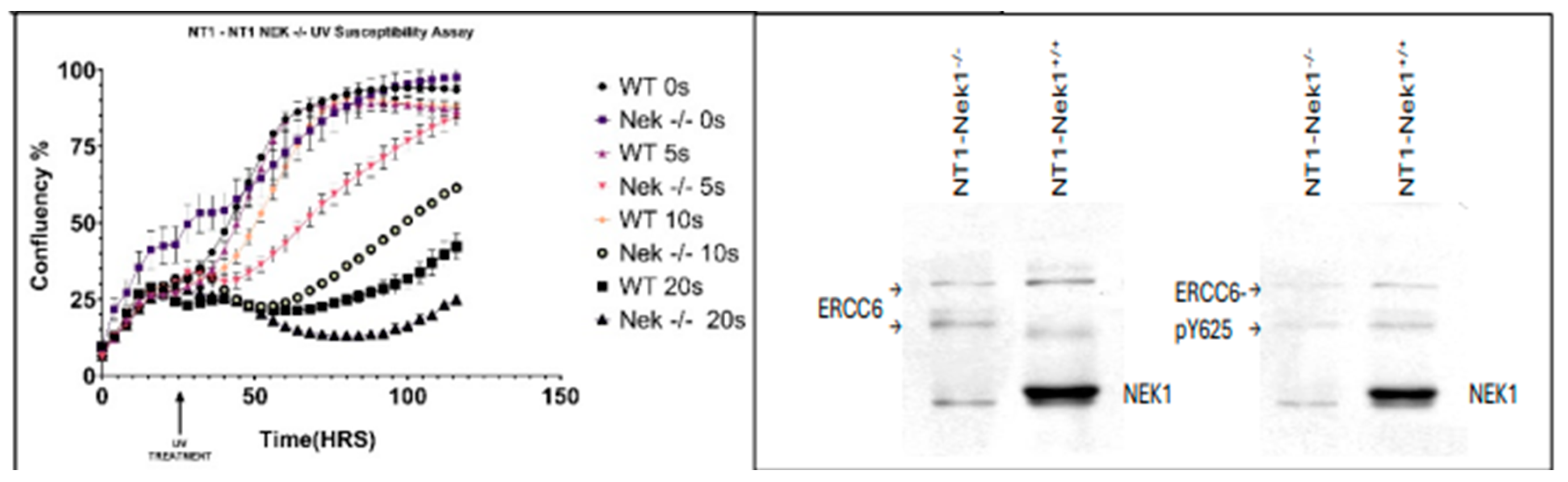

Figure 6 below), the confirmation of pY625 dependence on Nek1 was confirmed in CRISPR-KO NT1 cells [

12] (

Figure 5 below).

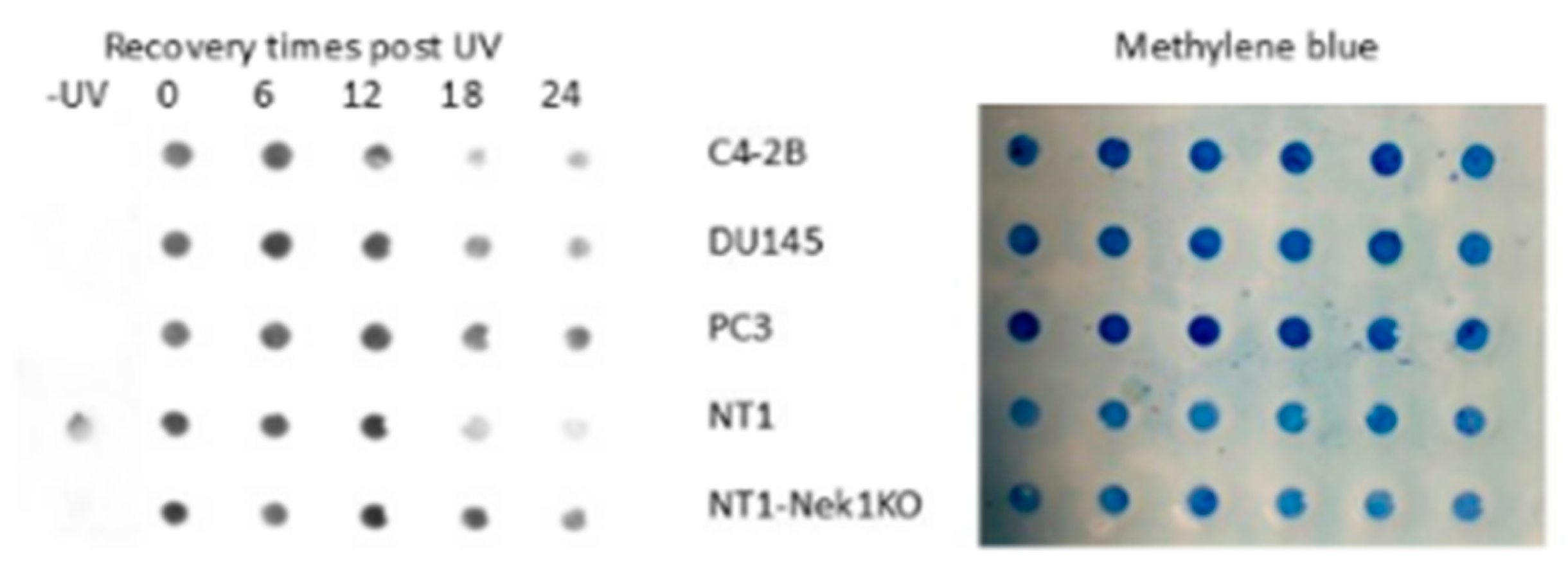

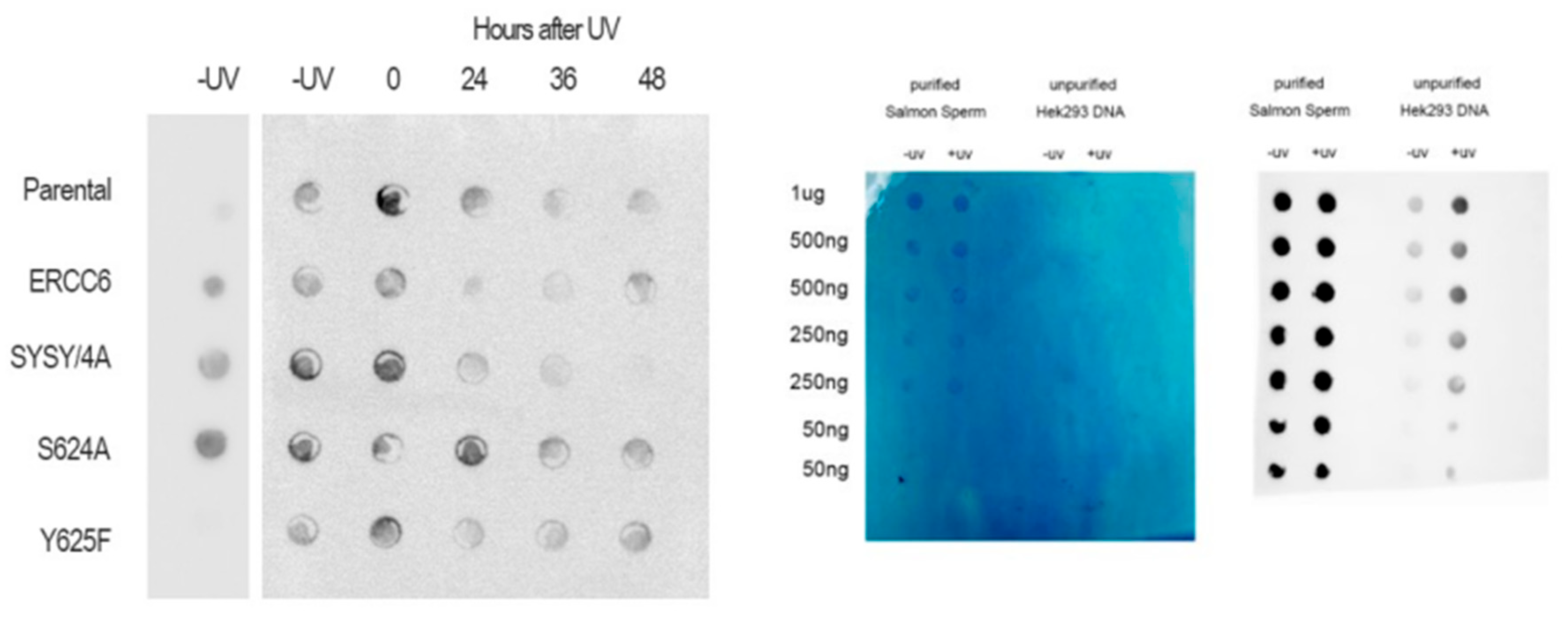

Nek1-deficient cells show reduced capacity to repair CPDs. The interaction of ERCC6 with NEK1 immediately posed the question of whether NEK1 could regulate the activity of ERCC6 in TC-NER and establish the intriguing nexus:TLK1>NEK1>ERCC6>CPD-Repair. We thus empolyed a Southwestern blot technique to probe the kinetics of CPD removal from total DNA in UV-irradiated control NT1 cells and congenic Nek1-KO [

48], as well as 3 other typical human PCa lines for comparison. Consistent with our hypothesis, while elimination of CPDs was completed within 12h in control NT1 cells, there was almost no detectable reduction in the Nek1-KO cells (

Figure 4 and SI4 for repeat with quantitation). Note, however, that this assay does not distinguish between TC-NER and GG-NER, so that the inolvement of ERCC6 in the elimination of CPDs is only a partial explanation for the proposed TLK1>NEK1>ERCC6 activity on UV-damaged DNA. An obvious issue was to investigate the pattern of UV sensitivity in the NT1-Nek1-KO cells compared to parental NT1. UV exposure results in a cell cycle arrest, and then there is an expected recovery lag before proliferation resumes, but more importantly, when it does, the slope of proliferation rate gives a key estimate of how good the repair was, as an indication of the overall ‘fitness’’ of the cells population after recovery from a highly mutagenic event. As shown in

Figure 5, at all UV doses tested, except for the highest 20s (highly lethal) exposure, the Nek1-KO cells were much less fit for recovery, indicating a deficiency in NER capacity decreased their viability.

NEK1 phosphorylates ERCC6 in vitro at several residues and one main consensus patch.

An extensive peptide-based screen for NEK1 consesus phospho-sites has been published [

49], but we think it may actually not represent the correct situation. Apart from the incorrect conclusion that NEK1 does not phosphorylate at Tyrosines, which argues against the very incept of its initial identification [

50], it is also not the situation we have encontered when we IVK’ed several substrates (including NEK1 autophosphorylated iteslf) with the recombinant kinase [

48,

51] (for published examples). In fact, our work suggests that the best consensus sequence is a tight patch of hydroxy AA residues – in YAP the key residue(s) phosphorylated was the

SY in the patch SMSSY [

48]; and in RAD54, the main site was all 3

S in KSSSETQIQ [

51]. Interestingly, there are two such sets in human and mouse ERCC6 (highlighted) and one is further highly conserved even in two yeast species (

Figure 6 - highlighted in red and yellow). In fact, all 5 (bracketed) residues were found to be phosphorylated by an IVK with recombinant NEK1 and ERCC6, determined by MS ion fragmentation analysis. Both pS624 and pY625 are annotated in PhosphoStie-plus as previously identified in vivo by MS.

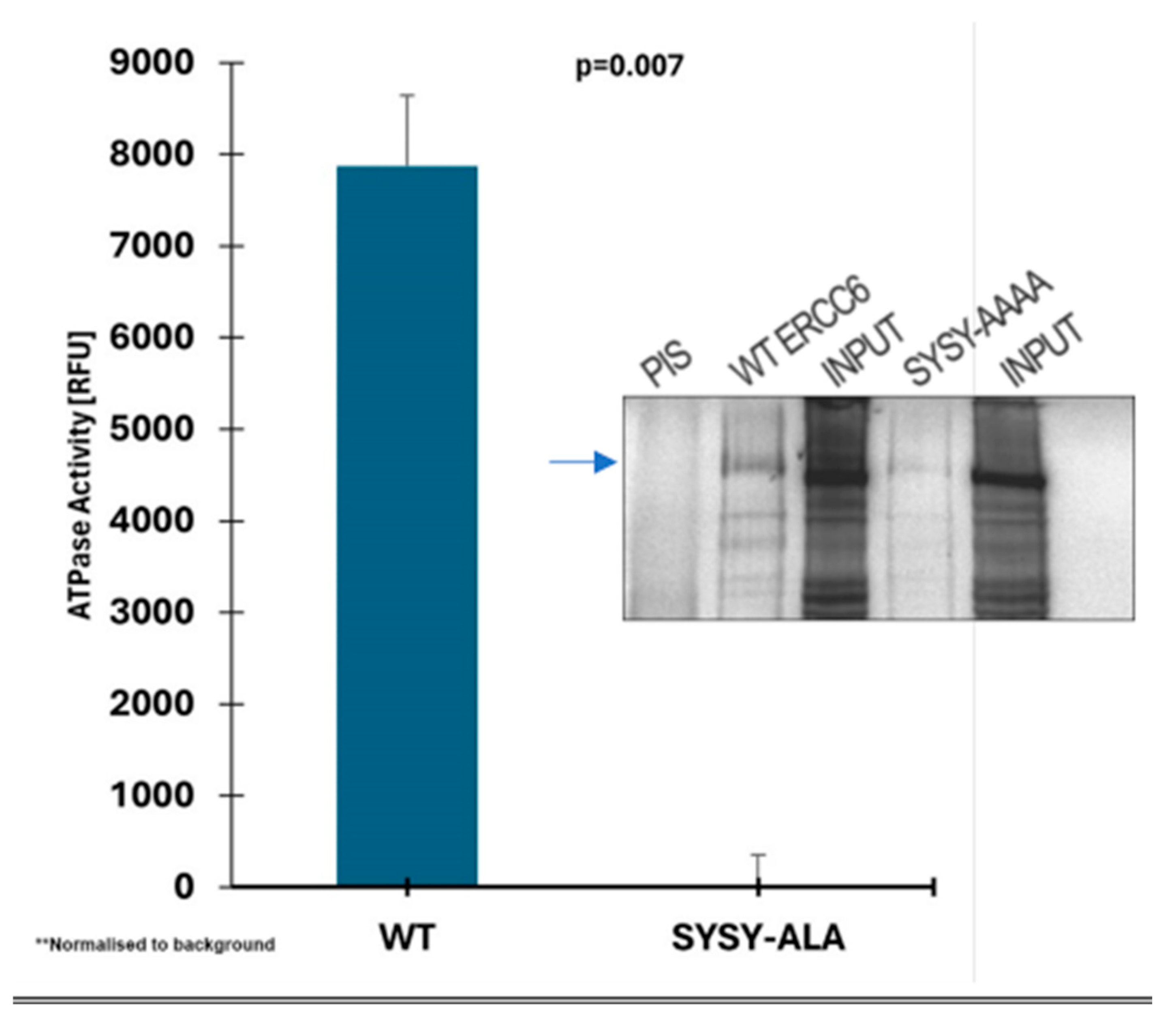

The consensus TSYSY box is critical for the ATPase functional activity of ERCC6. We have demostrated by MS analysis that all 5 residues in the high NEK1 consensus site of ERCC6 are in fact phosphorylated in vitro by recombinant NEK1. In order to seek a quick answer for the possible regulatory function of these potential phosphorylation sites on the activity of the CSB protein in vitro (ATPase activity in presence and absense of substoichiometric amount of NEK1) we replaced the SYSY with Ala residues. We then first determined the ATPase activity of the recombinat wt and mutant proteins, in presence of the essential DNA. To our surprise, the Ala-replaced mutant protein was completely inactive for the ATPase function, even without any potential contribution from NEK1 phosphorylation/activation (

Figure 7 – note that the slight reduction in expression compared the wt ERCC6 cannot explain the total loss of activity for the SYSY/4A protein). This, clearly indicated those residues are actually essential for the function of CSB and not just potential regulatory site(s) via reversible phosphorylation, and complicates a possible interpretation for the possible regulation of CSB by NEK1. We should point out that we have previously also made Hek293 cells expressing NEK1-wt and dominant inactive T141A mutant [

38], which have similar doubling times, unlike the NT1-Nek1-KO cells. These Hek/Nek1-T141A cells are in fact highly sensitive to UV or H2O2 [

38], and we could have made a case for the direct “loss” of regulation/ activation of CSB by the hypoactive Nek1-T141A mutant (that cannot be activated by TLK1) as the immediate cause for their damage sensitivity. However, it was previously demonstrated by Lee Zou’s group [

52], and confirmed by us [

38], that NEK1 is a key ‘primer’ for the activation of ATR, particularly after UV exposure – in fact, the only one of the 11-members Nek family that posses such activity [

52]. Thus, following this line of investigation would have led to ambiguous interpretation for the UV sensitivity in attributing this to its NEK1 and ERCC6 interplay.

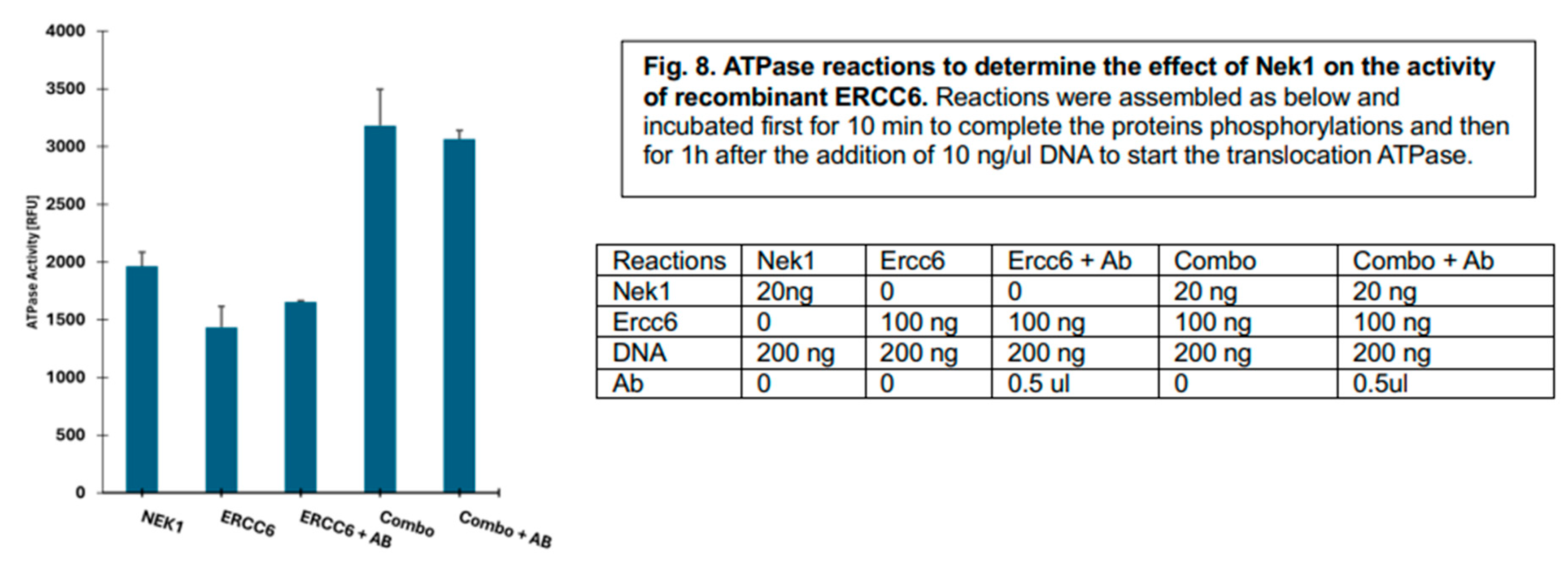

The 6. with NEK1 increase its ATPase activity.

While the structure/fnction significance of the SYSY/Ala replacement requires a complex investigation with molecular dynamics (see below), we sought to determine is the converse phosphorylation by NEK1 (overall at all target sites) could result in a change of the ATPase activity. For this, highly recombinant proteins were used and assmebled in reactions that essntially determine the accumulation of ADP at the end point (ADP-Hunter, DicoverX).

For control reactions testing specificity, we added ~200 ng of ERCC6 antiserum, which unfortunately did not appear to block its, DNA-dependent ATPase, likely because of inoperative inactivation of a critical acitivity site. Despite the lack of this desired control, the results obtained suggest that the addition of sub-stoichiometric amounts of NEK1 more than additively enhanced the overall ATP>ADP conversion attributable to ERCC6 produced by its DNA translocation function (

Figure 8 – note that the DNA subtrate was added after the kinase/phosphorylation activation step of Nek1 (ADP-generating) was complete and thus only the ERCC6 ATPase remained. Perhaps the additional negative charge developing on the TSYSY patch upon NEK1 phosphorylation may loosen the contact with DNA enhance the overall ‘translocase’ activity of ERCC6. It is not clear how in general this would affect the TC-NER function(s) of this complex protein-machine. However, a model proposed for the E.coli homolog, Mfd, indicated a highly regulated process with mutliple rounds of rather ‘slow’ATP hydrolysis accompanied with conformational changes, for the initial assocition with the stalled EC (not present in our conditions of course). But these intramolecular rearrangements are likely involved in the discrimination between a EC that is simply ‘paused’ vs.one that is stalled at a DNA lesion [

8] - the likely key difference being the presence of a significant lesion-induced distortion in the DNA helix.

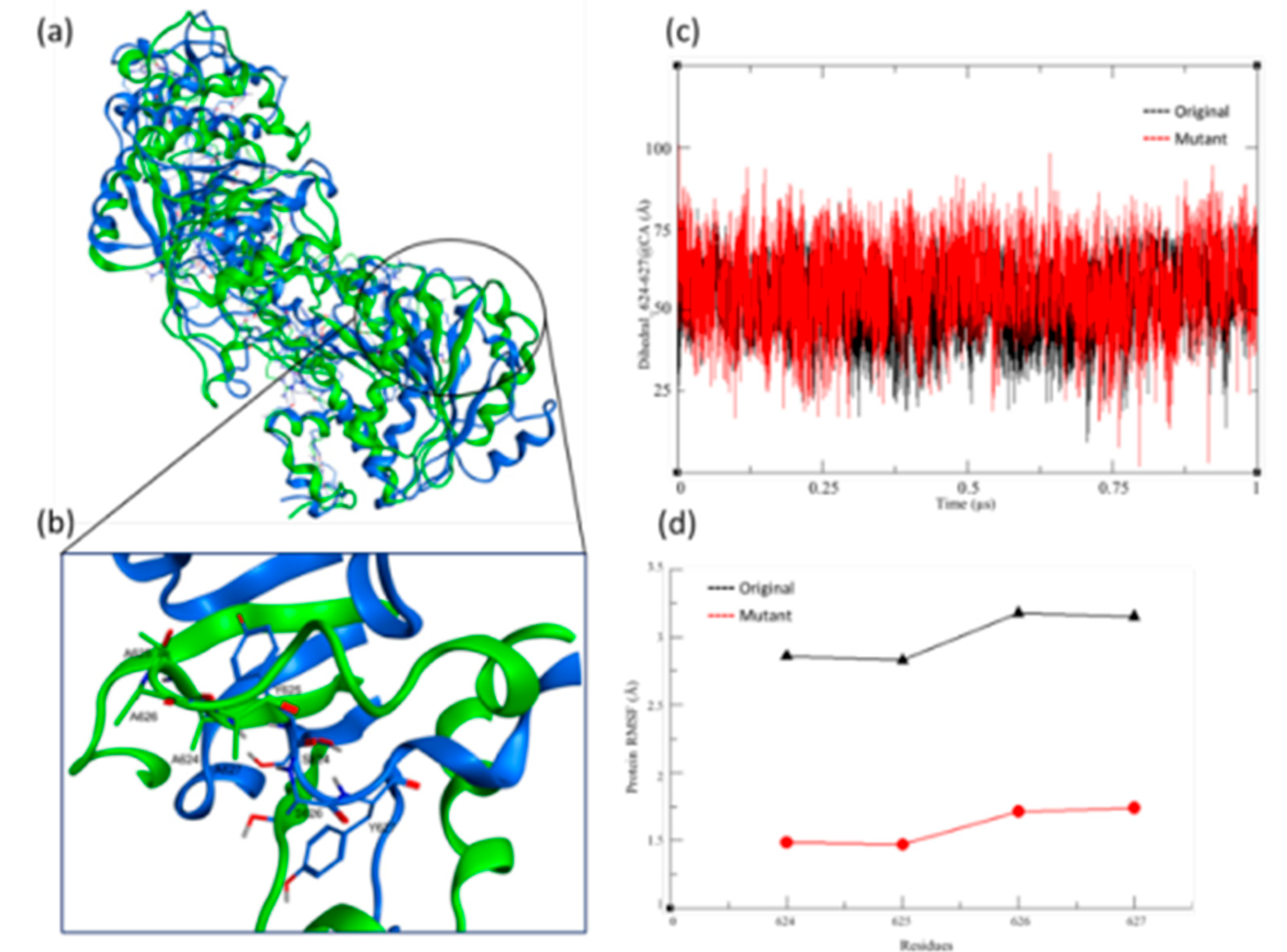

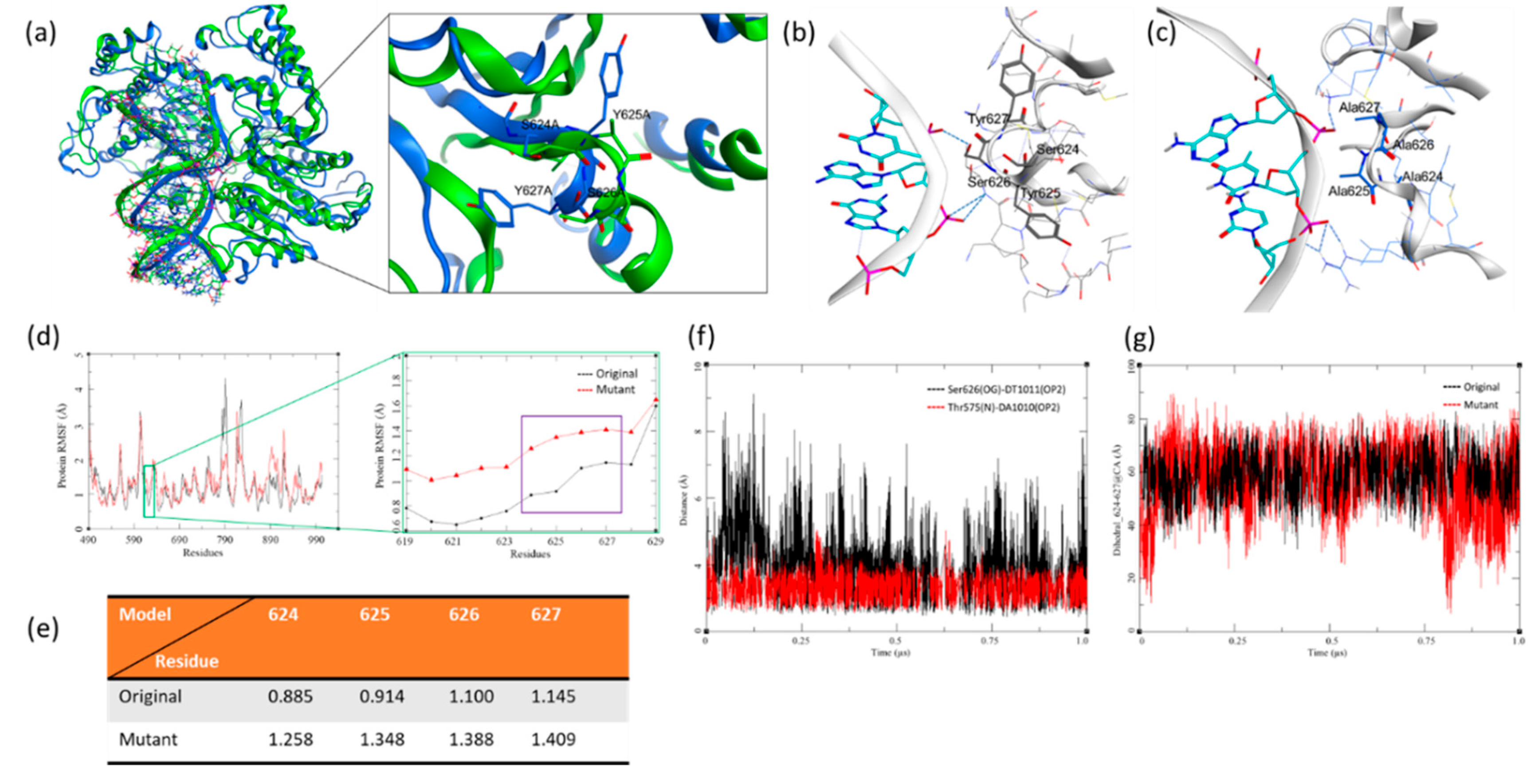

Modeling of ERCC6-wt and SYSY mutant and its contact with DNA. Due to the lack of a crystallographic or cryo-EM structure for the DNA excision repair protein ERCC-6 sequence in its DNA-bound and unbound form, we use AlphaFold3 (Abramson, J et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold3. Nature (2024)) for modelling the protein and protein-DNA complex. Here, we also studied some reference models to understand better the larger complexes like the human transcription-DNA repair coupling (PDB: 7OOP) (

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03906-4). To begin with, we used the complete ERCC-6 (Q03468 · ERCC6_HUMAN,

https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q03468/entry) sequence to investigate the structure of the protein in the bound and unbound state. Two models were generated with an original sequence and the other with mutations at the S624A, Y625A, S626A and Y627A residues. The goal was to understand the effect of these four mutations on the flexibility, inter- and intramolecular interactions, stability and flexibility of the protein structure in this DNA binding region of the ERCC-6. Here, the first study was focused on the unbound states (

Figure 9a), and the model was built using the most recent version of the Alfafold3 tool. The AlphaFold3 model showed a predicted template modelling (pTM) score of 0.56, suggesting the overall structure predicted might be similar to the actual structure. However, the structural validation using the Ramachandran

φ and

ψ analysis, MolProbity score and the Qmean values suggested for structural optimisation. To address this challenge, these structures were subjected to a 1.0 µs classical molecular dynamics (cMD) simulation under an explicit solvent model; the details of the setup and the parameters are provided in the supplementary information. The original and the mutant model’s cMD trajectories were analysed, and the structural aspects were explored to seek insights into the structural dynamics of ERCC-6 in its original and mutated state. For the original sequence model, the protein Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) was found to fluctuate from 2-8Å accounting for a 6Å deviation, with a steep rise around 0.25 µs, reaching its highest during 0.6 µs, and then going down gradually till the end of the simulation. However, in the case of the mutant model, there were no sudden changes in the protein RMSD; it showed a slow and steady rise of about 1Å till the first 0.4 µs and later remained within 1Å, totaling a fluctuation of 2Å throughout the simulation duration. These limited fluctuations suggest a stable structure of the modelled protein (SI_Figure Ia). The same behavior was observed with the Root Mean Square Fluctuations (RMSF) of the individual residues of the protein structure, where the original sequence model showed an overall higher fluctuation, with the mutant model showing higher spikes in the loop regions, which is an obvious nature of the protein dynamics (SI_Figure Ib). These modelled proteins were subjected to structural validations before and after the simulations, where their secondary nature (SI_Figure Ic,d), Ramachandran analysis (SI_Figure Ie) and template modelling scores (SI_Figure If) were calculated and tabulated. The MolProbity score for the original sequence model improved from 1.76 to 1.70, and from 1.59 to 1.42 for the mutant sequence model; a lower MolProbity score shows improvement of the protein structure regarding steric clashes and geometric optimisation. Similarly, the Qmean scores improved to 0.66 and 0.68 for the original and mutant sequence models. The higher Qmean score indicates the sound quality of the protein structure model with regard to residue-residue distances matching closely to the homologous structures in the PDB databases. A close analysis of the mutated sequence S624A, Y625A, S626A and Y627A shows the loss of intramolecular interactions for the mutant sequence model (

Figure 9b), which was anticipated due to the lack of sidechain in residue alanine. A dihedral analysis was performed to compare this behaviour. The αC atoms for these four residues in the original and mutant were analysed to find common ground. The dihedral angle analysis (

Figure 9c) shows higher fluctuations in the mutant sequence (624A, 625A, 626A and 627A) model, which corroborates the fact that due to the lack of sidechains and thus the lack of intramolecular interaction leads to higher mobility (20 - 90 Å). The original sequence (624S, 625Y, 626S and 627Y) shows lower backbone dihedral fluctuations between 30 - 60 Å as sidechains stabilise this region. The mutant residue analysis for its RMSF corroborates that the SYSY domain shows higher fluctuations due to the flexibility, whereas the mutant (AAAA) domain lacks this structural feature (

Figure 9d). In these initial experiments, we established the model and the structural nature of the ERCC-6 in its original and mutated state. The next step was to understand the effect of DNA's presence and how the protein-DNA interactions and loss of interactions affect the ERCC-6-mediated regulation.

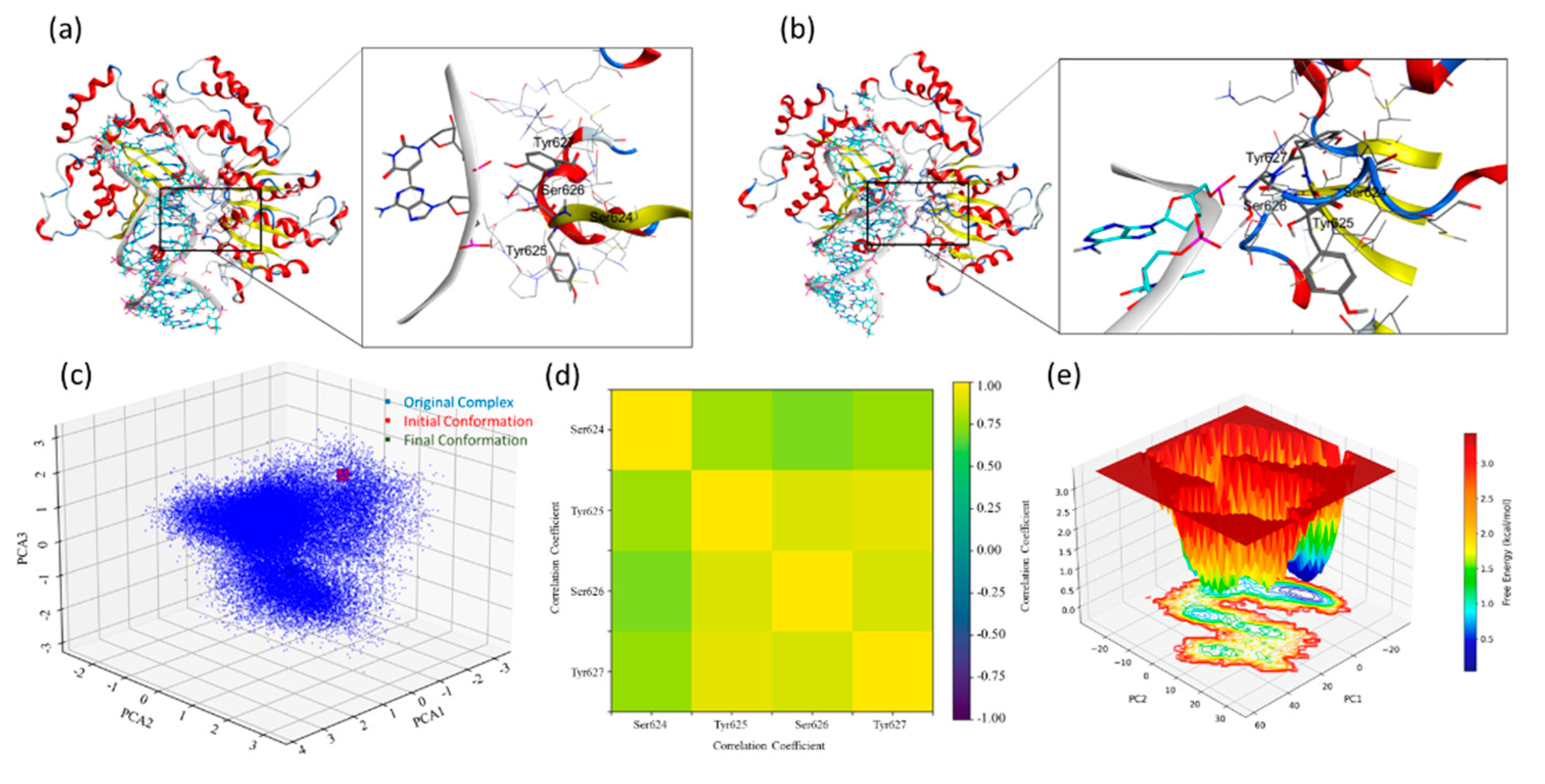

The protein-DNA complex modelling and cMD simulations were performed similarly to those mentioned earlier, and details about methods and materials are provided in the SI. However, the analysis was extended for the DNA, and a deeper study was performed involving the energetics of the original and the mutated sequence models. The protein RMSD was analysed, the original sequence model showed a steep rise in the RMSD accounting for 2-3 Å between 0-250 ns, next spike in the RMSD was observed around 500 ns, but the average RMSD remains at 2 Å for the 1.0 µs. The mutant sequence model showed a slow rise in the RMSD over the first 500 ns, but remained within 2.0 Å, and shows a convergence in its fluctuations by remaining with 1.0 Å for the rest of the simulation (SI_Figure IIa). This RMSD fluctuation pattern is similar to the one observed in earlier experiments, except for the lower fluctuations that could be due to the presence of the DNA segment, stabilising this protein dynamics. The protein RMSF calculated for the complete trajectory showed a similar pattern of fluctuations except for some highly flexible regions around residues 790-810 and 890-910. Again, the lower RMSF for both structures indicate stabilisation of the protein models with the reduction of overall RMSF by about 2.0 Å when compared with the DNA bond and unbound form (SI_Figure IIb). The protein radius of Gyration (RoG) for the Original and the Mutant sequence mode remained between 25.25 to 26.25Å and 25.5 to 26.75Å, respectively, throughout the MDS. This indicates that the protein complexes are compact and highly stable (SI_Figure IIc). The αC atom dihedral for the residues 624-627 in the protein-DNA complexes was also analysed and it shows the characteristic high fluctuations for the mutant sequence model with a range of 20 – 80 Å along with several spikes in the fluctuations, whereas the original sequence model showed a comparatively stable composition with fluctuations between 40 – 80 Å (SI_Figure IId), this is strengths our understanding of the intra ad intermolecular interaction for the bound and unbound state of the ERCC-6 protein. In this study, the DNA segment with 32 base pairs in the form of duplex DNA is bound to the ERCC-6 protein; the simulations were able to sample a stable complex through the 1.0 µs MDS for the original and mutant protein sequence models (

Figure 10a, f). Along with the protein structures, the DNA segment was also analysed for its structural integrity and interaction with the protein binding site, as suggested in the literature (10.7554/eLife.62117,

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03906-4). The DNA RMSD was calculated for the base pairs in both complexes; the RMSD in both cases was limited within 3.0 - 6.5 Å throughout the simulation trajectory (SI_Figure IIe). This was also supported by the DNA RoG where the DNA bound to the original protein sequence model was within the 16.5 - 19.5 Å and for mutant complex it was between 16.5 - 18.5 Å, for the DNA structures, RoG between 15-30Å is considered as highly stable and compact structure, indicating the higher stable complexes (SI_Figure IIf). The structural aspects were further validated similarly as discussed earlier, the original sequence model in complex with DNA had MolProbity, Qmean, TM and IDDT scores of 1.50, 0.70, 0.93 and 0.74, respectively, suggesting its stability and compact nature. The RC plot shows an acceptable range of favoured region, and RMSD to the initial pose from the MDS simulation was 2.37 Å, which is a promising number since it is a large protein with a duplex DNA complex (SI_Figure IIg,h). The mutant sequence model in complex with DNA had MolProbity, Qmean, TM and IDDT scores of 1.46, 0.68, 0.92 and 0.72, respectively, suggesting its stability and compact nature. The RC plot shows an acceptable range of favoured region, a bit higher compared to the original sequence model, and RMSD to the initial pose from the MDS simulation was 2.56 Å, which is suitable for a large protein in complex with the duplex DNA segment (SI_Figure IIg, i).

The presence of side chains at the interface of the ERCC6-DNA is crucial for the stability of this complex. We extracted these complexes' initial and final poses to investigate and explain this mechanism. Visual analysis of the original sequence model shows hydrogen bond interactions between the SYSY motif residues with the base pairs of the duplex DNA segment, the Ser626 forms an hydrogen bond interaction with DNA and this bond was found to stabilise throughout the MD simulation, apart from these interactions Tyr627 forms a hydrogen bond interaction with the base pairs (Figure10a,b). The MDS trajectory analysis has already established a compact complex for the original sequence model, but analysing the different modes and motion of the system over 1.0 µs MDS is difficult. We calculated the covariance matrix from the atomic coordinates to perform this analysis and identify the dominant motions and conformational changes. We then extracted the principal components (eigenvectors and eigenvalues) and projected these components for more straightforward interpretation of the standard modes using principal component analysis (PCA). The PCA plot shows three PCA components over the X-Y-Z axis with the initial and final state of the protein-DNA complex conformation from the MDS. The PCA analysis suggests two major components clustered around the final conformation (

Figure 10c). Significant clustering could be observed over PC1 (between 1 and -2 over the x-axis), capturing the large-scale motion of the complex and suggesting one central cluster of stable conformations (SI_Figure IIIa). This explains the minor difference between the complex's initial and final pose, with the converged complex following initial fluctuations. A Dynamical Cross-Correlation Matrix (DCCM) plot was analysed for the trajectory to investigate the per-residue interaction stability, a complete scan and focused (S624, Y625, S626 and Y627) residue analysis was performed (

Figure 10d and SI_Figure IIIb ). A Dynamic cross correlation maps (DCCM) plot highlights the correlated motions between the atoms and the residues in a given protein structure during the MDS, allowing for the exploration of positive and negative correlations, the collective motion of the residues, and deciphering the functional mechanism of the protein system. The DCCM analysis of the select residues from the ERCC-6 protein shows a positively correlated motion with a coefficient of 0.75 and 1.0 for the 1.0 µs MDS trajectory analysis of the original sequence model (Figure_10d). Whereas, the complete protein structure shows an overall satisfactory correlation coefficient ranging between -0.75 and 1.0 for most of the residues and 1.0 for the diagonal elements, explaining the stability of this complex (SI_Figure IIIb). A free energy landscape (FEL) analysis was performed to investigate the stability of the complex and its conformational states.

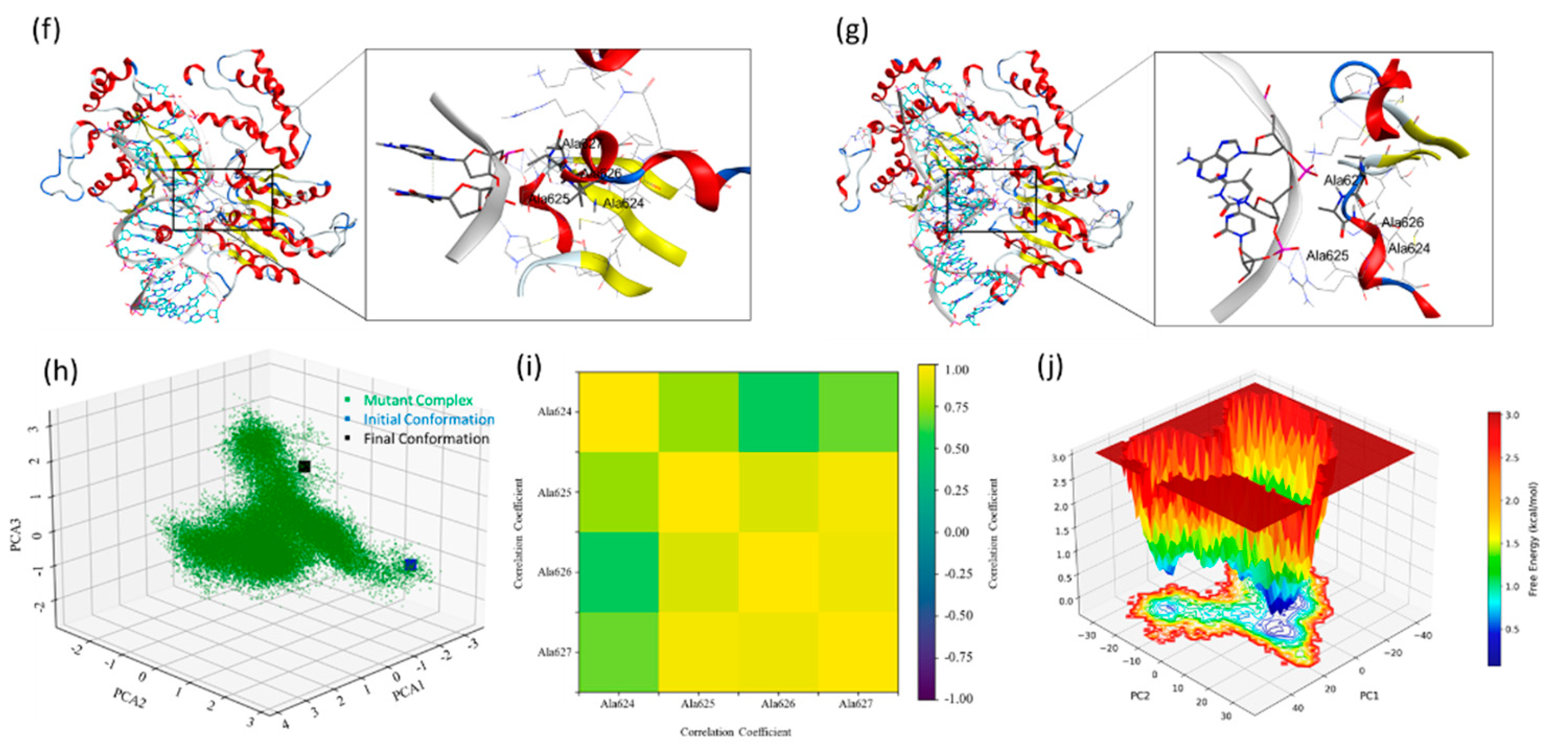

Figure 10e shows several deep and shallow minima representing the highly stable and transforming conformations converging towards stable conformations. These show the free energy levels in the range of 1.5 to about 0.5 kcal/mol and below for some of the conformational ensembles (PC1:PC2:PC3; -20:5:0). It also shows a continuous minima transitioning from shallow to deeper minima leading to a deeper minima valley indicating a stable low energy conformation was achieved during the simulation. On the same lines, the mutant sequence model was examined. The visual analysis of the mutated sequence patch of S624A, Y625A, S626A and Y627A shows loss of interactions between the residues and the adjacent bases (

Figure 10f and g), which was expected due to the lack of sidechain due to the induced mutation. However, the tight packing of the DNA segment in the binding domain allows for the interaction with the residues from the adjacent amino acids, like Thr575, which shows a stable interaction with the adjoining adenine from the DNA segment. Two-dimensional PCA presents an unclear picture about the clustering of the eigenvalues with the initial and the final state close, based on the two principal components (PC1 and PC2) (SI_Figure IIIc). To verify this observation, a 3D-plot for three PC’s were studied, which supports the initial reading as the significant conformation variations fall in 2-3 closely packed conformation buckets, leading to a low conformational deviation once the complex achieves a convergence as observed from the protein and DNA backbone RMSD (

Figure 10h, SI_Figure IIa and e). The DCCM analysis of this trajectory indicates a positive correlation coefficient of about 0.25 for Ala626, but the diagonal coefficient is near 1.0 (

Figure 10i). The DCCM analysis of the complete structure (SI_Figure IIId) shows a negative correlation coefficient for several regions, suggesting a higher fluctuation area of the complex. The loss of interaction, such as hydrogen bond interactions, of the given mutation patch has increased the dynamic motion of this portion of the backbone, allowing it to stay in the helical form instead of the sheet form for most of the simulation instances. The FEL analysis for the mutant sequence model showed a clear reflection of the PCA analysis, where the two distinct deep minima were observed and a low barrier transition was seen from the starting to the lowest energy conformation over the PC1 (

Figure 10j). The FEL shows low energy conformations, indicating the complex enters a higher stable state, possibly due to a lack or loss of function.

In this study, the mutation of residues 624-627 (SYSY) has impacted the interaction with the bound DNA base pairs. It also affected the structural form of this protein patch, where the mutant model shows a string helical nature due to the presence of alanine. In contrast, the original sequence tends to form beta sheet-like interactions (

Figure 11a, Geen= AAAA, Blue= SYSY). Our investigation focused on this patch and its surrounding region since the DNA segment finds several interaction points throughout its length. Several intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonds were observed in both complexes. Hydrogen bond interactions are the intermolecular forces formed between donor-acceptor pairs. They are based on how distant the bond-forming heavy atoms are and the directionality of the covalent hydrogen atom. H-bond interactions maintain and hold base pairs, stabilise protein structures, and regulate DNA-protein interactions. In this case, we observed these hydrogen bond interactions between the ERCC-6 and the DNA segment where the Ser626 forms the H-bond with DNA bases. Still, these are not limited to residues of interest; the adjacent residues also interact with these bases (

Figure 11b, c). The RMSF of the patch residues shows interesting fluctuations; the original sequence model shows low RMSF due to its stabilisation by forming hydrogen bond interactions with the adjacent DNA bases, owing to their side chains (

Figure 11d). Whereas the mutant sequence shows higher fluctuations due to the lack of these H-bond interactions, these differences are quite noticeable given the tight packing of these regions (

Figure 11e). The distance-based H-bond and the Dihedral were calculated for these models to ascertain our results. The mutant patch did not yield any results, which was evident due to the lack of side chains and the distance from the backbone was beyond the range of H-bond (2.5 to 3.7 Å). The original sequence model showed two prominent hydrogen bond interactions throughout the 1.0 µs MDS simulation. First, Ser626(OG)-DT1011(OP2), which belongs to the patch of interest; this H-bond showed high fluctuation but existed for most of the simulation towards the lower limit of 2.5 Å, the make and break nature is due to the flexibility imparted by the dynamic motion of the side chain and the bases (

Figure 11f). Second Thr575(N)-DA1010(OP2), this was investigated to understand the stability of the complex, where the residues adjacent to the DNA segment, other than the SYSY patch, hold the complex together. This H-bond presents a strong interaction while staying within 2.5 to 3.7 Å for most instances (

Figure 11f). In this case, the lack of sidechains limited our dihedral analysis to the backbone atoms. Hence, the αC were plotted over the simulated time. The plot in

Figure 11g clearly indicates the stability of the original sequence model’s complex; here, the dihedral angle is highly restricted, within 40° (40-80 on the Y-axis) throughout the simulation, indicating the stability of the complex and thus higher interaction with the DNA bases. Meanwhile, the mutations led to higher dihedral motion; hence, its backbone movement is less stable, indicating a lack of interaction with the adjacent DNA bases, which also implies that this mutation could lead to the loss of function.

The comple loss of ATPase activity for the SYS/4A ERCC6 mutant, combined with the apparent activity dependence on phosphorylation by NEK1, prompted us to monitor via modeling and molecular dynamics the structure of the protein and possible contact with DNA at that specific site. This revealed that the SYSY hydroxy patch that is the main consesus target of NEK1 forms an actual springlike machine that is presumed to function in translocation (or unwinding) consuming ATP. It also may be a very active part of protein carrying out extensive intramolecular displacements to either move along the DNA helix, or potentially dragging along the stuck EC. The high intramolecular rearrangements at theis active site were further confirmed in molecular dynamics simulations and interpretation of RMSD and RMSF after 1 µs, showing that in contrast to the wt, the SYS/4A mutant is essntially ‘frozen’ and incapable of movement.

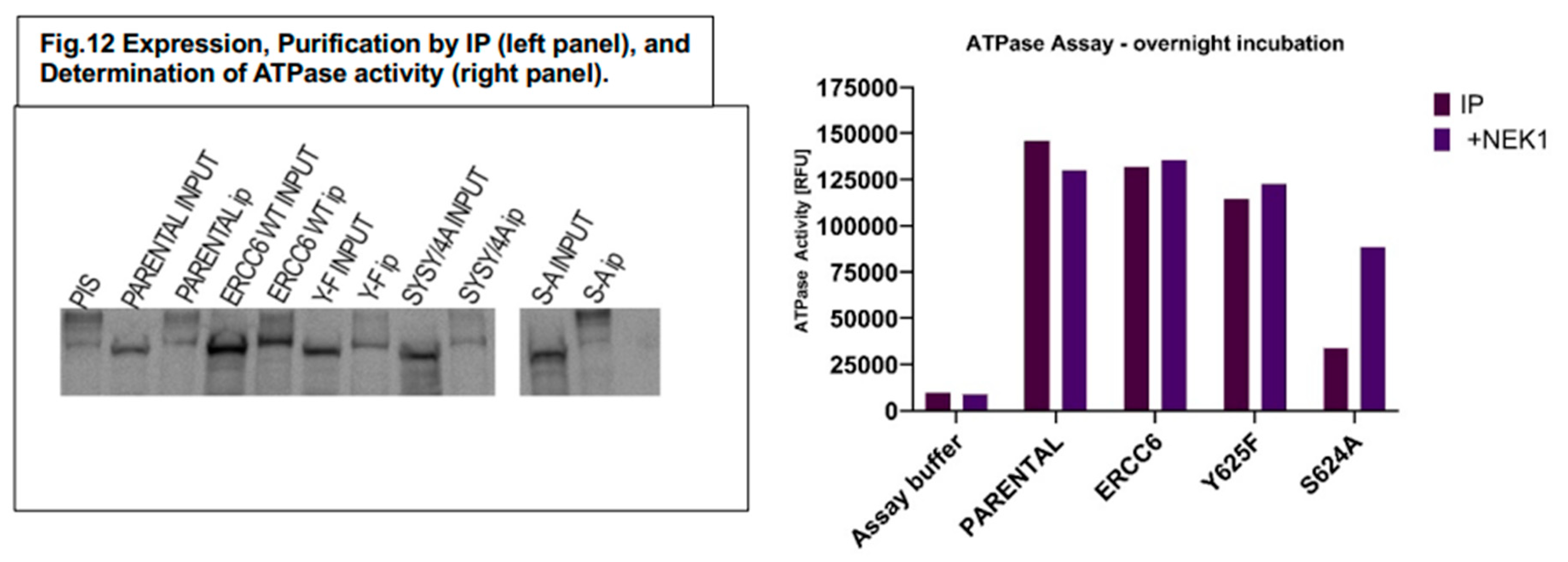

In vitro ATPase activity of the various mutant ERCC6. We IP’d the different ERCC6 versions and carried out ATPase assays on ‘bound’ ProteinA/G beads, with and w/o a small amount of NEK1 to determine their activation. Due to the small amount of recovered proteins (panel B), the ATPase reactions were carried out overnight. Endogenous ERCC6 (parental) and wt- overexpressed protein in Hek293 gave essentially the same signal and no dependence on added Nek1 (as expected since these are likely already phosphorylated in vivo). The Y-F is mostly a dead protein that likely contributes no activity over the endogenous ERCC6 in vivo, suggesting that the Y625 is critical for functioning. The S624A is also mostly inactive, but in a long incubation, it can be resuscitated significantly in presence of Nek1 stimulation. So, we suggest that the Y625 is critical for the ERCC6 overall catalytic activity in presence of DNA (ATPase), while the S624 is likely the main residue that is most subject to regulation by Nek1 and can fine-tune/orchestrate its function.

Figure 12.

Expression, Purification by IP (left panel), and Determination of ATPase activity (right panel).

Figure 12.

Expression, Purification by IP (left panel), and Determination of ATPase activity (right panel).

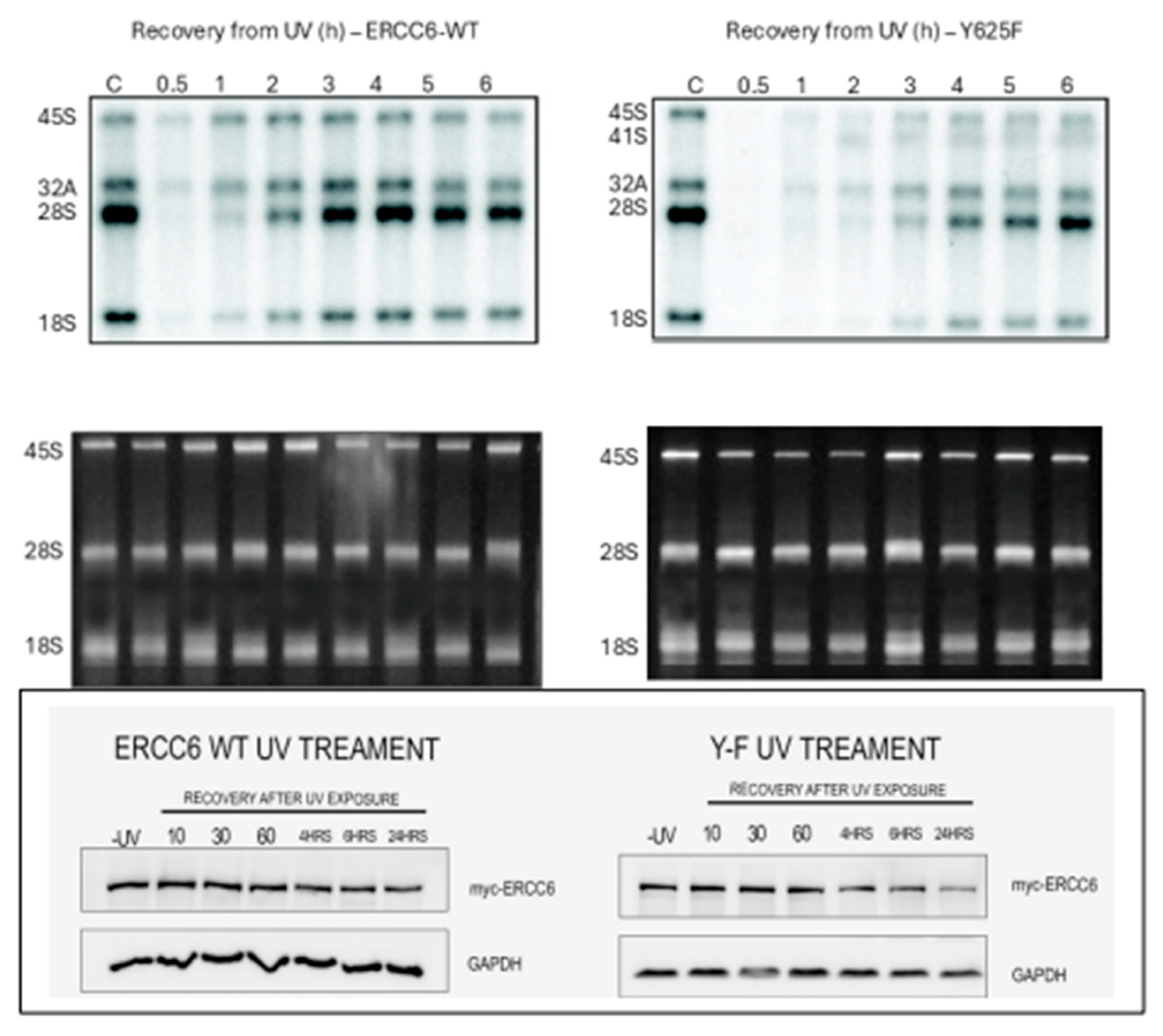

Delayed recovery of rRNA expression after UV in the Y625F mutant cells. Our hypothesis derived from the experiments so far on the roles of ERCC6 in TC-NER (both PolII and PolI), and recovery of transcription and processing of rRNA genes is that the overexpressed wt- protein should hasten these processes, while the poorly active Y625F mutant, that cannot be phosphorylated by NEK1, should act as a dominant negative machine in recovery from UV. We set to determine if this is true with a

3H-Uridine pulse labeling time course after a 10 sec UV exposure (or non-irradiated controls) in which the cells were labeled during the last 20 min of each time point. The result confirmed that the wt-ERCC6 overexpressing Hek293 cells fully recovered transcriptional activity and processing of mature 28S and 18S after 2h. In contrast, the Y625F expressing cells barely recovered full PolI transcriptional activity after 6h. Moreover, the ratio of 32S to 28S did not yet reverse even at 6h, and there was some accumulation of the 41S pre-rRNA. Interestingly, a reflection of this phenomenon was visible even at the level of EtBr staining of the major rRNA species (typically stable) in that there was a visible progressive decrease of the 45S precursor in the Y>F OE cells up to the point where PolI transcription restarts at 3h, whereas that did not happen in cells with OE-ERCC6. These data confirmed the critical role of active, presumably phosphorylated Y625, after recovery from UV. It would be a mistake to underestimate the significance of a few hours delay in recovery of the expression of rRNA (mature) transcripts for cells’ viability, since the generation of rRNA is coordinated with the Integrated Stress Response (ISR) enacted at transcriptional and translational levels for most ribosomal genes [

53]. Restoring normal functionality in a cell that typically replicates in <24h with such a a sreious delay may result in the (observed) loss of cell replicative capacity and even viability – note however that the Y>F cells grow well and syntheize rRNA at about the same rate as the wt-OE cell (or ‘parental’) in the absense of UV.

It is important to point out that the expression and stability of the Y625F mutant protein is not different than the wt, and thus, it is its activity that is rather defective in rRNA expression after UV recovery.

Figure 13.

Top. Determination of rRNA synthesis and processing rates in Hek293 expressing wt or Y625F ERCC6. 105 cells plated in 24-wells were exposed to UV for 10s and allowed to recover for the indicated times and labeled during the last 20 min of each time point with 50µCi/ml 3H-Uridine. RNA was isolated, fractionated on a 1.2% agarose gel, then processed for fluorography with PPO. Bottom. Expression and stability of wt and Y625F after UV.

Figure 13.

Top. Determination of rRNA synthesis and processing rates in Hek293 expressing wt or Y625F ERCC6. 105 cells plated in 24-wells were exposed to UV for 10s and allowed to recover for the indicated times and labeled during the last 20 min of each time point with 50µCi/ml 3H-Uridine. RNA was isolated, fractionated on a 1.2% agarose gel, then processed for fluorography with PPO. Bottom. Expression and stability of wt and Y625F after UV.

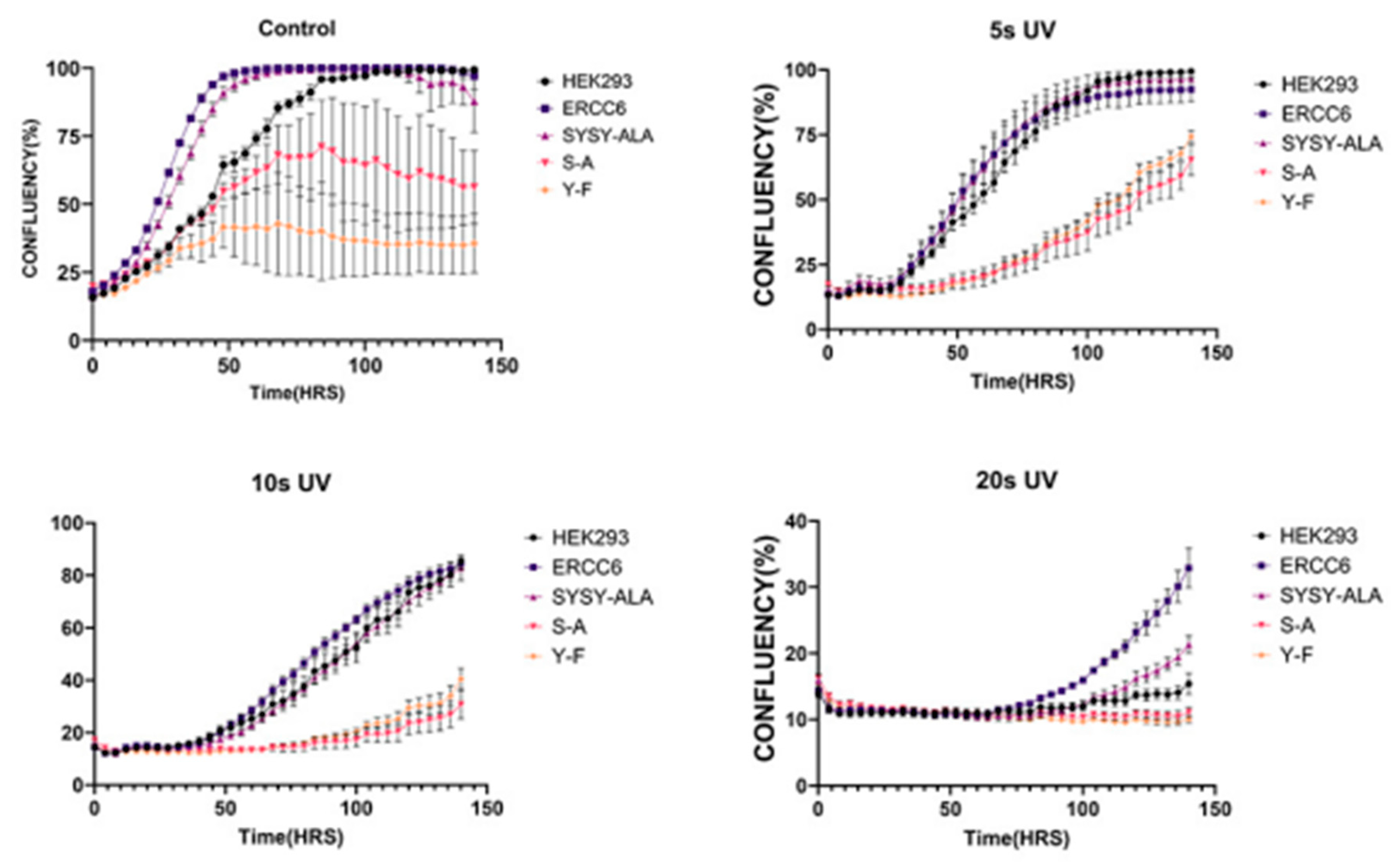

Figure 14.

Growth curves of Hek293 expressing wt of mutants ERCC6 following increasing times of UV exposure (top panel).

Figure 14.

Growth curves of Hek293 expressing wt of mutants ERCC6 following increasing times of UV exposure (top panel).

The different ERCC6 mutants-carrying lines were tested for their sensitivity to UV, expecting they would exert dominant effects over the endogenous wt-protein. Of course, we first examined their growth rate w/o UV (

Figure 15). Interestingly, SYSY/4A (SYSY-ALA) grew well and no different than parental HEK293, in contrast to all the mutants and even the OE-WT (ERCC6) that showed partial growht impairment. This indicates that even under normal unchallenged conditions ERCC6 expression, and particularly the dominant-negative mutants, confer growth impairments, except for the SYSY/4A completely unfunctional protein. After UV irradiation, all ERCC6 OE mutants were much more sensitivie to all doses (exposure time in sec)except for the OE-WT that conferred significant resistance even at 20s exposure, as could be predicted. While the effects on UV sensitivity were anticipated given the critical role of ERCC6 in TC-NER, the lack of growth inhbition w/o UV in the OE-SYSY/4A, which is a completely non-functional protein, may seem odd. So, an analogy seems appropriate. The NER ‘core mechanism’ consists of a pair of spacely-defined cuts bracketing the lesion, and the replacement of the offending flap followed by re-syntesis of the corrected complementary strand. The analogy is that a pair of rusty scissors that poorly open/close is not a huge problem because they are just not used while there is still the endogenous functional pair (ERCC6-WT). But a pair of not-sharp scissors (The S-A or Y-F dominant mutants) can be a serious problem even in non-irradiated cells. Until, of course, there is lot of work to be done (as after UV) in which case, the cells are forced to use also the rusty scissors (SYSY/4A) - and then they don't do that well.

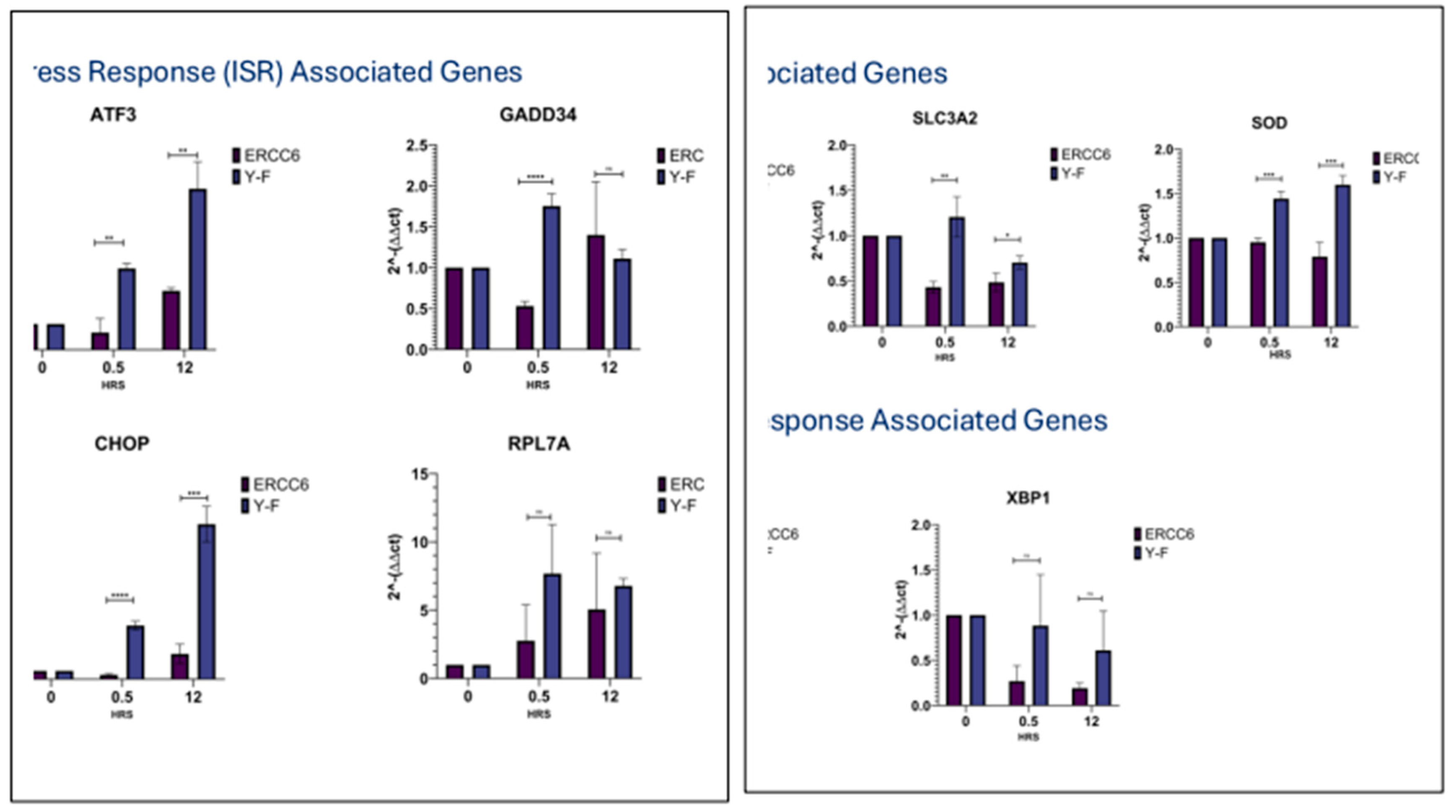

Prolonged activation of the ISR in the Y625F expressing cells. The delayed recovery of rRNA expression in the Y625F expressing cells revoring from UV was expected to result in prolonged activation of the ISR. In fact, all the expression of all ISR genes we tested were affected by the delayed recovery of rRNA expression in the Y625F mutant (

Figure 16). Notably, the strong increased ATF3 expression in the Y625F mutant may play a key role in maintaining suppression of some 70% of PolII genes after UV as a key ISR mechanism to UV [

54], but with the important exception of ribosomal proteins genes, like RPL7A. But interestingly, GADD34, a eIF2 alpha phosphatase that turns off the ER stress that was activated by GCN2 or PERK after UV [

55], showed rapidly increased expression after 0.5h of recovery and was still somewhat elevated after 12h. This is perhaps an attempt to maintain ribosomes biogenesis by maintaining partial translation of ribosomal proteins and utilizing a pre-existing rRNA pool to compensate for the delayed recovery of newly synthesized mature rRNA species, despite the fact that the ‘call’ for increased expression of mRNA for ribosomal proteins was not as robust in the recovering Y625F mutants (e.g., RPL7A). XBP1, or X-box binding protein 1, a transcription factor critical for protecting cells from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and is specifically ‘processed’ via the IRE1 pathway, and that plays a key role in regulating genes involved in immune and cellular stress responses, showed the Y625F mutant cells retained more of the ‘unspliced form’ (uXBP1) after UV, and thus slower ‘coping’. Although the ‘spliced form’ (sXBP1 – derived from IRE1-processing) is believed to be the ‘master regulator’ of the ER stress genes, it is now believed that the uXBP1 has an underappreciated role [

56]. In any case, it was clear that the delayed recovery of mature rRNA expression in the Y625F mutant during recovery from UV had a dramtic effect on the ISR as a whole, and consequently viability. UV exposure can at the same time cause mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress that, in toto, can augment the ISR in the Y625F mutant expressing cells, while the arrest in ribosomes biogenesis and related ‘translation’ stress form P-eIF2 can be sensed in the ER as a UPR.

Evidence for a conserved evolutionary pathway in the regulation of ERCC6/Rad26 activity by NEK and phosphorylation of the Hyrdoxy patch. The RAD26 gene is

not essential for viability in the yeast

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, meaning yeast cells can survive and grow without it. However, its absence leads to defects in DNA repair and increased sensitivity to DNA damage, but primarily bulky adducts[

57,

58]. In fact, while Rad26 activities in TC-NER are believed to be similar [

58]to the mammalian ERCC6, there are also some key differences:

Non-essential function: Unlike its human homolog CSB, a mutation in yeast's RAD26 does not cause hypersensitivity to ultraviolet (UV) light under normal conditions [

59]. This is because yeast has an alternative and highly efficient DNA repair pathway (Global Genome Repair, or GGR) that compensates for the loss of Rad26.

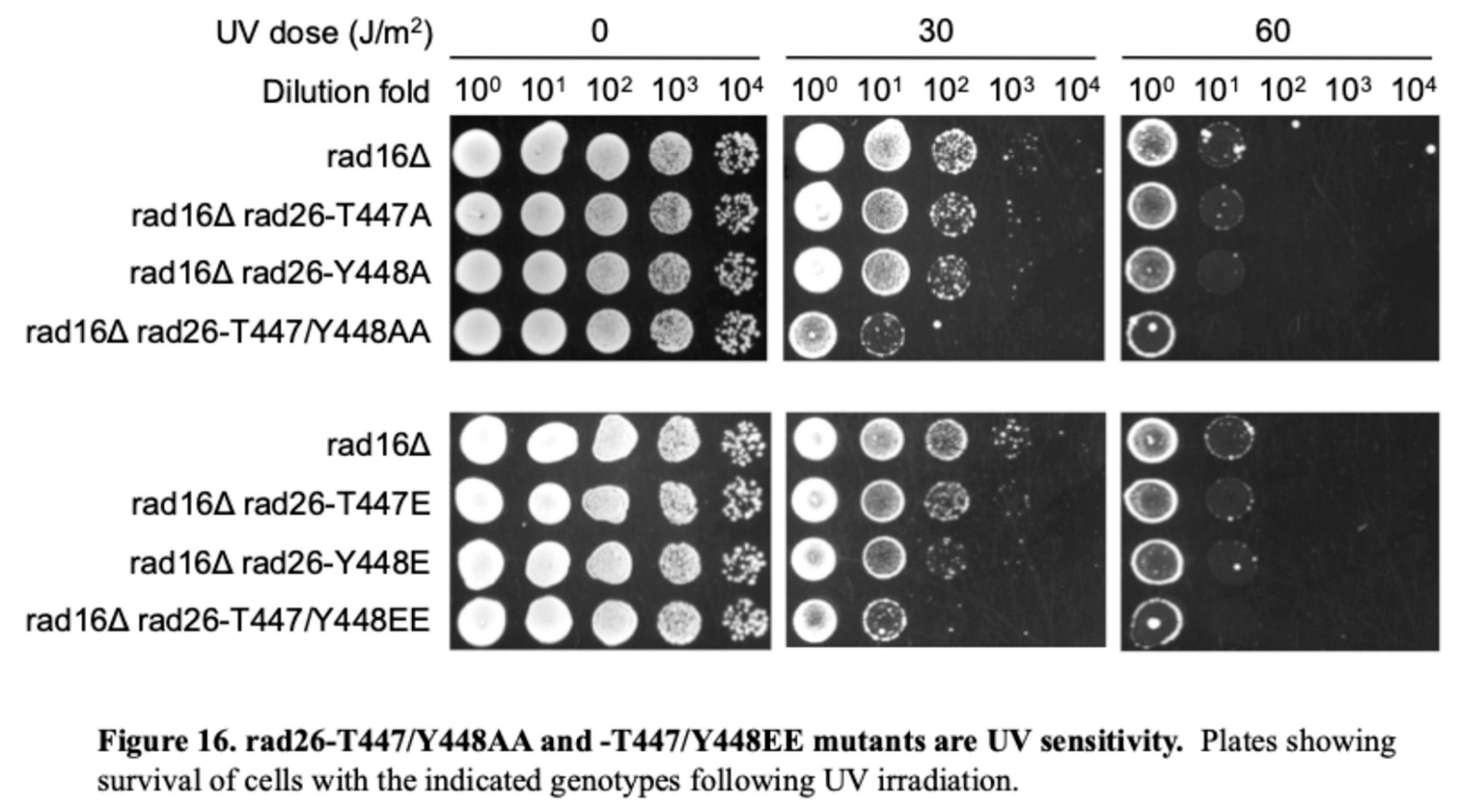

Increased sensitivity under specific conditions: When the alternative GGR pathway is also disabled (such as in a rad16∆ rad26∆ double mutant), the yeast becomes much more sensitive to DNA-damaging agents like UV light. Our work proceeded under these premises.

Based on the assumption that the conserved Hydroxy patch would serve a similar structure/function relationship, we conducted a CRISPR-mediated SDM of residues T447 and Y448 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad26 correspond to residues S624 and Y625 within the TSYSY box of human ERCC6. To determine the role of the TSYSY box in transcription-coupled repair (TCR), we substituted Rad26 residues T447 and Y448 with either alanine (A) or glutamic acid (E) in rad16Δ cells, which are defective in global genomic repair (GGR) and thus allow unambiguous analysis of TCR [

60].

Single mutations—

rad26-T447A,

rad26-Y448A,

rad26-T447E, or

rad26-Y448E—had little effect on cellular UV sensitivity (

Figure 16). In contrast, the double mutants

rad26-T447/Y448A and

rad26-T447/Y448E displayed significantly increased UV sensitivity, indicating that these substitutions compromised Rad26’s TCR function. As both AA and EE substitutions displayed greate UV sensitivity, one possible explanation is that activity regulation (perhaps DNA translocation) may require cycles of phosphorylation and de-phosphorylation, for which examples in other proteins are known (e.g., eIF4E in translation initiation cycles [

61]. Of course, we had to guess that a kinase exists for the phosphorylation of those specific residues, wherein the yesat Nek homologue is Kin3. This kinase has obvious actvities in regulating the cell cycle, but also in sensitivity to certain DNA damage types and is involved in DNA adducts damage response [

62], although sensitivity to UV (just as for Rad26) does not seem strong, which we confirmed independently in 3 different strains (not shown). And direct proof of phosphorylation of these reisdues by Kin3 is very difficult in yeast.

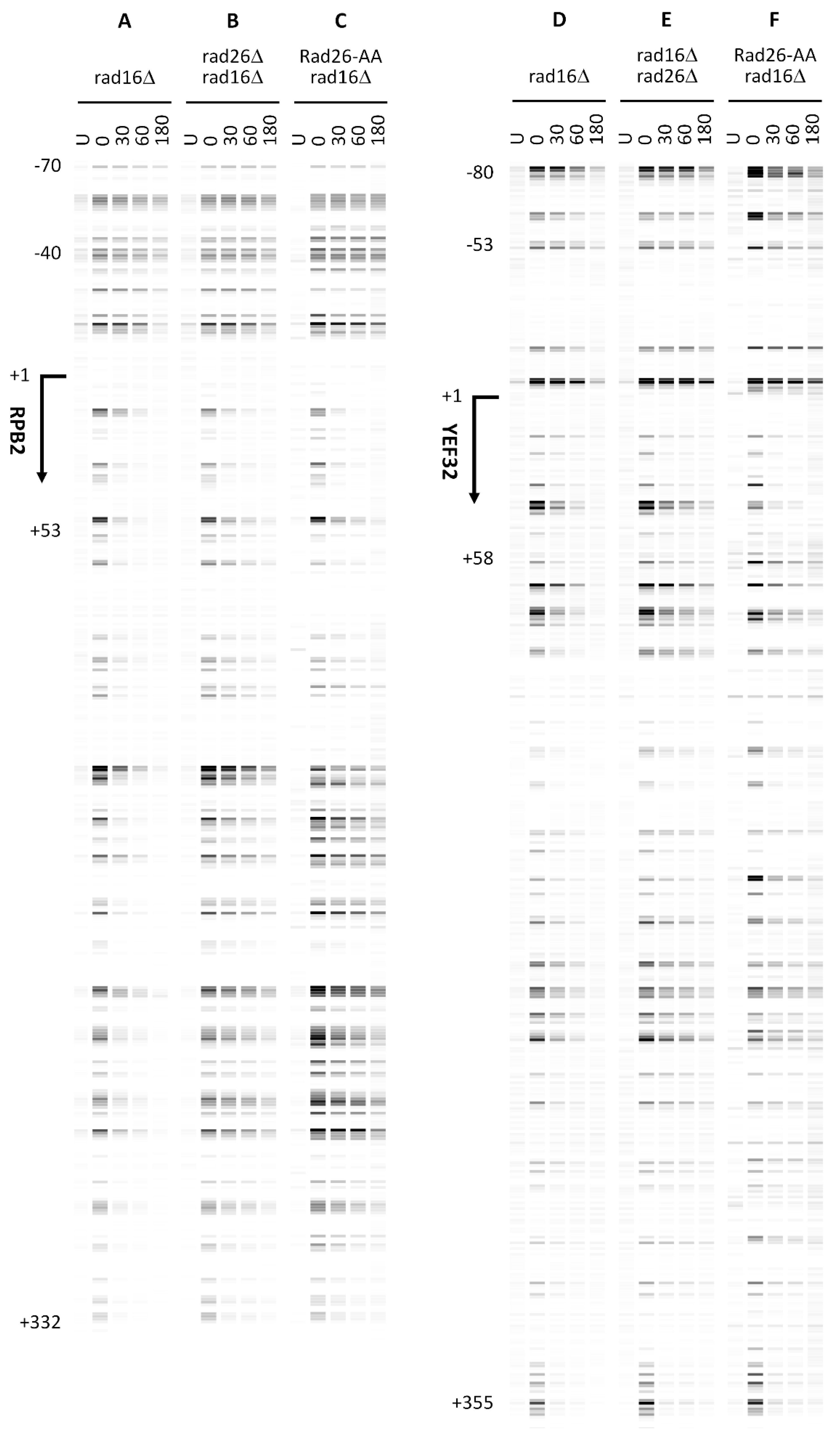

To study directly the impact of these Rad26 mutations on TC-NER (of Pol2 genes in this case, which is much simpler for the yeast genome complexity), we directly measured the impact of

rad26-T447/Y448A on TCR of UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) using our LAF-seq technique [

15]. In

rad16Δ cells, rapid CPD repair occurred immediately downstream of the major transcription start site (TSS) on the transcribed strand (TS) of the moderately transcribed

RPB2 gene (

Figure 17) and the highly transcribed

YEF3 gene (

Figure 2D). Deletion of

RAD26 (

rad26Δ) markedly slowed TCR (

Figure 17, compare B with A, and E with D). The

rad26-T447/Y448A mutation reduced TCR to a similar extent as

rad26Δ (

Figure 17, compare C with B, and F with E), indicating that

rad26-T447/Y448A effectively abolished Rad26’s TCR activity.