Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Validation of the Prediction Model

2.2. Summary of miRNA Sequencing Data in Endometrial Tissue and Plasma Samples

2.3. Endometrial miRNA Expression Profile During the Peri-Implantation Window

2.4. Functional Analysis of Endometrial Dynamic DE miRNAs

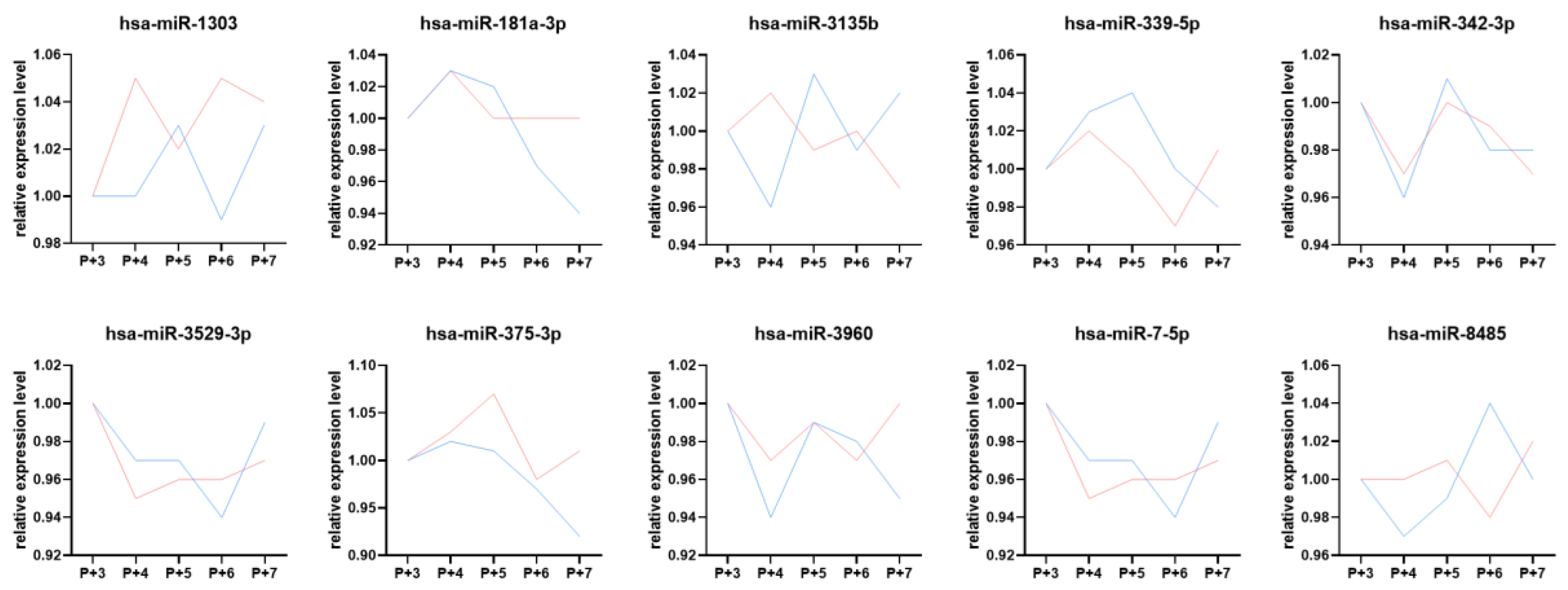

2.5. Plasma Dynamic DE miRNAs and Their Biological Functions During the Peri-Implantation Window

2.6. Comparison of Dynamic DE miRNAs Between Endometrial Tissue and Plasma Samples

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Approval

4.2. Study Population

4.3. Endometrial Tissue and Plasma Sample Collection and Preparation

4.4. Endometrial Tissue Small RNA Extraction

4.5. Plasma Small RNA Extraction

4.6. miRNA Library Construction and Sequencing

4.7. NGS Data Analysis Pipeline

4.8. Identification of Dynamic and DE miRNAs

4.9. miRNA List and Target Gene Retrieval

4.10. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

4.11. Correlation Analysis Between Clinical Characteristics and DE miRNAs

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BP | Biological process |

| DE miRNAs | Differentially expressed miRNAs |

| FSH | Follicle stimulating hormone |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| HRT | Hormone replacement therapy |

| IVF | In vitro fertilization |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LH | Luteinizing hormone |

| microRNAs | miRNAs |

| MTI | miRNA-target interaction |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| UMI | Unique molecular index |

| WOI | Window of implantation |

References

- Paria, B.C.; Huet-Hudson, Y.M.; Dey, S.K. , Blastocyst's state of activity determines the "window" of implantation in the receptive mouse uterus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993, 90, 10159–10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.A.; Elberger, L.; Borghi, M.; Calamera, J.C.; Chemes, H.; Doncel, G.F.; Kliman, H.; Lema, B.; Lustig, L.; Papier, S. , Endometrial dating and determination of the window of implantation in healthy fertile women. Fertil Steril 2000, 73, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.A. , Control of the immunological environment of the uterus. Rev Reprod 2000, 5, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, H.; Kong, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Armant, D.R. , Physiological and molecular determinants of embryo implantation. Mol Aspects Med 2013, 34, 939–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamonsen, L.A.; Evans, J.; Nguyen, H.P.; Edgell, T.A. , The Microenvironment of Human Implantation: Determinant of Reproductive Success. Am J Reprod Immunol 2016, 75, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomic, V.; Kasum, M.; Vucic, K. , Impact of embryo quality and endometrial thickness on implantation in natural cycle IVF. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2020, 301, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galliano, D.; Pellicer, A. , MicroRNA and implantation. Fertil Steril 2014, 101, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.B. M.; Sadek, S.T.; Mahesan, A.M. , The role of microRNAs in human embryo implantation: a review. J Assist Reprod Genet 2019, 36, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. , Role of microRNAs in embryo implantation. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2017, 15, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Kim, V.N. , Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014, 15, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, J.; Jung, S.; Keller, S.; Gregory, R.I.; Diederichs, S. , Many roads to maturity: microRNA biogenesis pathways and their regulation. Nat Cell Biol 2009, 11, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, A.; Choi, Y.J.; Han, S.G.; Song, H.; Park, C.; Hong, K.; Kim, J.H. , Roles of microRNAs in mammalian reproduction: from the commitment of germ cells to peri-implantation embryos. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2019, 94, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salilew-Wondim, D.; Gebremedhn, S.; Hoelker, M.; Tholen, E.; Hailay, T.; Tesfaye, D. , The Role of MicroRNAs in Mammalian Fertility: From Gametogenesis to Embryo Implantation. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Lu, F.; Yang, W.J.; Yang, P.E.; Chen, W.M.; Kang, S.T.; Huang, Y.S.; Kao, Y.C.; Feng, C.T.; Chang, P.C.; Wang, T.; Hsieh, C.A.; Lin, Y.C.; Jen Huang, J.Y.; Wang, L.H. , A novel platform for discovery of differentially expressed microRNAs in patients with repeated implantation failure. Fertil Steril 2021, 116, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Lu, F.; Yang, W.J.; Chen, W.M.; Yang, P.E.; Kang, S.T.; Wang, T.; Chang, P.C.; Feng, C.T.; Yang, J.H.; Liu, C.Y.; Hsieh, C.A.; Wang, L.H.; Huang, J.Y. , Development of a Novel Endometrial Signature Based on Endometrial microRNA for Determining the Optimal Timing for Embryo Transfer. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, X.; Taylor, H. , MicroRNA and gynecological reproductive diseases. Fertil Steril 2014, 101, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilabert-Estelles, J.; Braza-Boils, A.; Ramon, L.A.; Zorio, E.; Medina, P.; Espana, F.; Estelles, A. , Role of microRNAs in gynecological pathology. Curr Med Chem 2012, 19, 2406–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Grothusen, C.; Frisendahl, C.; Modhukur, V.; Lalitkumar, P.G.; Peters, M.; Faridani, O.R.; Salumets, A.; Boggavarapu, N.R.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K. , Uterine fluid microRNAs are dysregulated in women with recurrent implantation failure. Hum Reprod 2022, 37, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Fu, Y.; Shen, L.; Quan, S. , MicroRNA signatures in plasma and plasma exosome during window of implantation for implantation failure following in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2021, 19, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zeng, H.; Fu, Y.; Ma, W.; Guo, X.; Luo, G.; Hua, R.; Wang, X.; Shi, X.; Wu, B.; Luo, C.; Quan, S. , Specific plasma microRNA profiles could be potential non-invasive biomarkers for biochemical pregnancy loss following embryo transfer. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitit, M.; Kose, M.; Kaya, M.S.; Kirbas, M.; Dursun, S.; Alak, I.; Atli, M.O. , Circulating miRNAs in maternal plasma as potential biomarkers of early pregnancy in sheep. Front Genet 2022, 13, 929477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.J.; Hsu, A.; Lin, P.Y.; Chen, Y.L.; Wu, K.W.; Chen, K.C.; Wang, T.; Yi, Y.C.; Kung, H.F.; Chang, J.C.; Yang, W.J.; Lu, F.; Guu, H.F.; Chen, Y.F.; Chuan, S.T.; Chen, L.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Yang, P.E.; Huang, J.Y. , Development of a Predictive Model for Optimization of Embryo Transfer Timing Using Blood-Based microRNA Expression Profile. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, N.; Kropp, J.; Khatib, H. , MicroRNA Signaling in Embryo Development. Biology (Basel) 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, C.; Shen, R.; Guo, X.; Ling, X.; Liu, C. , Expression and potential role of microRNA-29b in mouse early embryo development. Cell Physiol Biochem 2015, 35, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, B.; Zhong, L.; Dou, S.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Shi, Q.; Mei, Y.; Wu, M. , miRNA-181 regulates embryo implantation in mice through targeting leukemia inhibitory factor. J Mol Cell Biol 2015, 7, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Sui, C.; Huang, K.; Wang, L.; Hu, D.; Xiong, T.; Wang, R.; Zhang, H. , MicroRNA-223-3p suppresses leukemia inhibitory factor expression and pinopodes formation during embryo implantation in mice. Am J Transl Res 2016, 8, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Wang, L.; Xing, Y.; Qian, J.; He, X.; Wu, J.; Zhou, J.; Hai, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Huang, J.; Gou, X.; Ju, Y.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Su, D.; Kong, L.; Liang, B.; Wang, X. , Dynamic peripheral blood microRNA expression landscape during the peri-implantation stage in women with successful pregnancy achieved by single frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer. Hum Reprod Open 2023, 2023, hoad034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourvinou, I.S.; Markou, A.; Lianidou, E.S. , Quantification of circulating miRNAs in plasma: effect of preanalytical and analytical parameters on their isolation and stability. J Mol Diagn 2013, 15, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. , Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Cho, M.; Do, Y.; Park, J.K.; Bae, S.J.; Joo, J.; Ha, K.T. , Autophagy as a Therapeutic Target of Natural Products Enhancing Embryo Implantation. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, B.; Kovacs, K.; Sulyok, E.; Varnagy, A.; Bodis, J. , Thrombocytes and Platelet-Rich Plasma as Modulators of Reproduction and Fertility. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.Y.; Rajamahendran, R. , Expression of Bcl-2 and Bax proteins in relation to quality of bovine oocytes and embryos produced in vitro. Anim Reprod Sci 2002, 70, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia-da-Silva, G.; Bell, S.C.; Pringle, J.H.; Teixeira, N.A. , Patterns of expression of Bax, Bcl-2 and Bcl-x(L) in the implantation site in rat during pregnancy. Placenta 2005, 26, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, C.; de Ruijter-Villani, M.; Stout, T.A. E. , Insulin-like growth factor system components expressed at the conceptus-maternal interface during the establishment of equine pregnancy. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 912721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulovski, N.; Whorton, A.E.; Shi, M.; Hayashi, K.; MacLean, J.A. , 2nd, Insulin signaling is an essential regulator of endometrial proliferation and implantation in mice. FASEB J 2021, 35, e21440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lague, M.N.; Detmar, J.; Paquet, M.; Boyer, A.; Richards, J.S.; Adamson, S.L.; Boerboom, D. , Decidual PTEN expression is required for trophoblast invasion in the mouse. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010, 299, E936–E946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makker, A.; Goel, M.M.; Nigam, D.; Mahdi, A.A.; Das, V.; Agarwal, A.; Pandey, A.; Gautam, A. , Aberrant Akt Activation During Implantation Window in Infertile Women With Intramural Uterine Fibroids. Reprod Sci 2018, 25, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajeddin, N.; Ahadi, A.M.; Javadi, G.; Ayat, H. , Evaluation of Myc Gene Expression as a Preventive Marker for Increasing the Implantation Success in the Infertile Women. Int J Prev Med 2020, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Raja, S.; Davis, M.K.; Tawfik, O.; Dey, S.K.; Das, S.K. , Evidence for coordinated interaction of cyclin D3 with p21 and cdk6 in directing the development of uterine stromal cell decidualization and polyploidy during implantation. Mech Dev 2002, 111, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Z.; Kuang, H.X.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Fu, Q.; Jiang, B.; Wang, W.; Jiang, S.; Ren, L.; Ma, L.; Pan, X.; Feng, X.L. , Temporal changes in cyclinD-CDK4/CDK6 and cyclinE-CDK2 pathways: implications for the mechanism of deficient decidualization in an immune-based mouse model of unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Mol Med 2022, 28, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, J.H.; Oh, S.J.; Yoo, J.Y.; Kwon, H.S.; Kim, Y.I.; Ferguson, S.D.; Ahn, J.Y.; Ku, B.J.; Fazleabas, A.T.; Lim, J.M.; Jeong, J.W. , Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 signaling pathway is required for endometrial decidualization in mice and human. PLoS One 2013, 8, e75282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilini, D.; Busacca, M.; Di Francesco, S.; Vignali, M.; Vigano, P.; Di Blasio, A.M. , PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 signalling pathways are involved in endometrial cell migration induced by 17beta-estradiol and growth factors. Mol Hum Reprod 2007, 13, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeddeker, S.J.; Hess, A.P. , The role of apoptosis in human embryo implantation. J Reprod Immunol 2015, 108, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Kaponis, A.; Iwabe, T.; Taniguchi, F.; Makrydimas, G.; Sofikitis, N.; Paschopoulos, M.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Terakawa, N. , Apoptosis in human endometrium and endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update 2004, 10, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devis-Jauregui, L.; Eritja, N.; Davis, M.L.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Llobet-Navas, D. , Autophagy in the physiological endometrium and cancer. Autophagy 2021, 17, 1077–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, J.J.; He, J.L.; Liu, X.Q.; Chen, X.M.; Ding, Y.B.; Tong, C.; Peng, C.; Geng, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.X.; Gao, R.F. , Endometrial autophagy is essential for embryo implantation during early pregnancy. J Mol Med (Berl) 2020, 98, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Wang, H.; Li, D.; Li, M. , Role of Endometrial Autophagy in Physiological and Pathophysiological Processes. J Cancer 2019, 10, 3459–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusumi, M.; Ihana, T.; Kurosawa, T.; Ohashi, Y.; Tsutsumi, O. , Intrauterine administration of platelet-rich plasma improves embryo implantation by increasing the endometrial thickness in women with repeated implantation failure: A single-arm self-controlled trial. Reprod Med Biol 2020, 19, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Wei, L.; Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Liang, X. , Autologous platelet-rich plasma promotes endometrial growth and improves pregnancy outcome during in vitro fertilization. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015, 8, 1286–1290. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, L.N.; Pang, J.; Chen, J.; Liang, X. , Autologous platelet-rich plasma infusion improves clinical pregnancy rate in frozen embryo transfer cycles for women with thin endometrium. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e14062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodis, J. , Role of platelets in female reproduction. Hum Reprod 2022, 37, 384–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.Z.; Yang, Y.; Lang, J.; Sun, P.; Leng, J. , Plasma miR-17-5p, miR-20a and miR-22 are down-regulated in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2013, 28, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Xu, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C. , The role of MiRNA in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Gene 2019, 706, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, X.; Xu, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Deng, M. , Differential expression of plasma-derived exosomal miRNAs in polycystic ovary syndrome as a circulating biomarker. Biomed Rep 2023, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellizar, A.; Refuerzo, V.; Ramos, J.D.; Albano, P.M. , Expression of specific microRNAs in tissue and plasma in colorectal cancer. J Pathol Transl Med 2023, 57, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Su, M.; Wu, Y.; Fu, L.; Kang, K.; Li, Q.; Li, L.; Hui, G.; Li, F.; Gou, D. , Circulating Plasma miRNAs as Potential Biomarkers of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Obtained by High-Throughput Real-Time PCR Profiling. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019, 28, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kin, K.; Miyagawa, S.; Fukushima, S.; Shirakawa, Y.; Torikai, K.; Shimamura, K.; Daimon, T.; Kawahara, Y.; Kuratani, T.; Sawa, Y. , Tissue- and plasma-specific MicroRNA signatures for atherosclerotic abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Am Heart Assoc 2012, 1, e000745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelescu, M.A.; Andronic, O.; Dima, S.O.; Popescu, I.; Meivar-Levy, I.; Ferber, S.; Lixandru, D. , miRNAs as Biomarkers in Diabetes: Moving towards Precision Medicine. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyyaly, M.A.; Vorobeva, E.V.; Kothalawala, D.M.; Fong, W.C. G.; He, P.; Sones, C.L.; Al-Zahrani, M.; Sanchez-Elsner, T.; Arshad, S.H.; Kurukulaaratchy, R.J. , MicroRNAs-A Promising Tool for Asthma Diagnosis and Severity Assessment: A Systematic Review. J Pers Med 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ba, Y.; Ma, L.; Cai, X.; Yin, Y.; Wang, K.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, X.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, X.; Xiang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; Shang, X.; Gong, T.; Ning, G.; Wang, J.; Zen, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.Y. , Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res 2008, 18, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P.S.; Parkin, R.K.; Kroh, E.M.; Fritz, B.R.; Wyman, S.K.; Pogosova-Agadjanyan, E.L.; Peterson, A.; Noteboom, J.; O'Briant, K.C.; Allen, A.; Lin, D.W.; Urban, N.; Drescher, C.W.; Knudsen, B.S.; Stirewalt, D.L.; Gentleman, R.; Vessella, R.L.; Nelson, P.S.; Martin, D.B.; Tewari, M. , Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 10513–10518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupec, T.; Bleilevens, A.; Iborra, S.; Najjari, L.; Wittenborn, J.; Maurer, J.; Stickeler, E. , Stability of circulating microRNAs in serum. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0268958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, E.; Ruiz-Alonso, M.; Miravet, J.; Simon, C. , Human Endometrial Transcriptomics: Implications for Embryonic Implantation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015, 5, a022996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumusoglu, S.; Polat, M.; Ozbek, I.Y.; Bozdag, G.; Papanikolaou, E.G.; Esteves, S.C.; Humaidan, P.; Yarali, H. , Preparation of the Endometrium for Frozen Embryo Transfer: A Systematic Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 688237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuokkanen, S.; Chen, B.; Ojalvo, L.; Benard, L.; Santoro, N.; Pollard, J.W. , Genomic profiling of microRNAs and messenger RNAs reveals hormonal regulation in microRNA expression in human endometrium. Biol Reprod 2010, 82, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirohi, V.K.; Gupta, K.; Kumar, R.; Shukla, V.; Dwivedi, A. , Selective estrogen receptor modulator ormeloxifene suppresses embryo implantation via inducing miR-140 and targeting insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in rat uterus. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2018, 178, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. , FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. In Babraham Bioinformatics, Babraham Institute, Cambridge, United Kingdom: 2010.

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. , Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. , Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozomara, A.; Birgaoanu, M.; Griffiths-Jones, S. , miRBase: from microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, (D1), D155–D162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; Genome Project Data Processing, S. , The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Y.; Kechris, K.J.; Tabakoff, B.; Hoffman, P.; Radcliffe, R.A.; Bowler, R.; Mahaffey, S.; Rossi, S.; Calin, G.A.; Bemis, L.; Theodorescu, D. , The multiMiR R package and database: integration of microRNA-target interactions along with their disease and drug associations. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.Y.; Lin, Y.C.; Cui, S.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xu, J.; Bao, J.; Li, Y.; Wen, J.; Zuo, H.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Ni, J.; Ruan, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Cai, X.; Chen, X.; Yao, L.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Y.; LuXu, S.; Luo, M.; Chiu, C.M.; Ma, K.; Zhu, L.; Cheng, G.J.; Bai, C.; Chiang, Y.C.; Wang, L.; Wei, F.; Lee, T.Y.; Huang, H.D. , miRTarBase update 2022: an informative resource for experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D222–D230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. , clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. , KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; Harris, M.A.; Hill, D.P.; Issel-Tarver, L.; Kasarskis, A.; Lewis, S.; Matese, J.C.; Richardson, J.E.; Ringwald, M.; Rubin, G.M.; Sherlock, G. , Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, D.; O'Kelly, G.; Wu, G.; Haw, R.; Gillespie, M.; Matthews, L.; Caudy, M.; Garapati, P.; Gopinath, G.; Jassal, B.; Jupe, S.; Kalatskaya, I.; Mahajan, S.; May, B.; Ndegwa, N.; Schmidt, E.; Shamovsky, V.; Yung, C.; Birney, E.; Hermjakob, H.; D'Eustachio, P.; Stein, L. , Reactome: a database of reactions, pathways and biological processes. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39, D691–D697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsella, R.J.; Kahari, A.; Haider, S.; Zamora, J.; Proctor, G.; Spudich, G.; Almeida-King, J.; Staines, D.; Derwent, P.; Kerhornou, A.; Kersey, P.; Flicek, P. , Ensembl BioMarts: a hub for data retrieval across taxonomic space. Database (Oxford) 2011, 2011, bar030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, J. , Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences., 3rd ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, N.J, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| P+ Day | P+3 | P+4 | P+5 | P+6 | P+7 | ANOVA p-value |

|||||||||||

| Sample number |

12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 12 | - | |||||||||||

| Age (mean ± SD) |

31.3 | ± | 4.6 | 29.2 | ± | 2.8 | 30.3 | ± | 4.1 | 31.6 | ± | 4.7 | 30.6 | ± | 3.7 | 0.599 | |

| BMI (mean ± SD) |

21.9 | ± | 2.1 | 22.1 | ± | 1.9 | 22.6 | ± | 3.7 | 21.4 | ± | 2.4 | 22.3 | ± | 2.4 | 0.796 | |

| sample number with a history of pregnancy |

7 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 6 | - | |||||||||||

| sample number without a history of pregnancy |

5 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 6 | - | |||||||||||

| FSH (mIU/ml) (mean ± SD) |

Day 2 | 6.28 | ± | 1.90 | 6.16 | ± | 1.45 | 8.09 | ± | 2.43 | 7.25 | ± | 2.04 | 6.50 | ± | 1.78 | 0.085 |

| Day 10-12 | 6.19 | ± | 2.16 | 6.05 | ± | 2.14 | 6.33 | ± | 1.63 | 6.33 | ± | 2.08 | 6.15 | ± | 1.24 | 0.995 | |

| P+ day | 3.30 | ± | 1.37 | 3.88 | ± | 1.33 | 4.14 | ± | 1.90 | 3.26 | ± | 0.89 | 4.02 | ± | 1.61 | 0.411 | |

| LH (mIU/ml) (mean ± SD) |

Day 2 | 4.19 | ± | 1.43 | 4.09 | ± | 1.40 | 4.05 | ± | 1.79 | 4.81 | ± | 3.86 | 4.83 | ± | 3.23 | 0.880 |

| Day 10-12 | 15.78 | ± | 8.78 | 14.09 | ± | 9.49 | 11.98 | ± | 7.12 | 15.53 | ± | 7.42 | 16.74 | ± | 7.58 | 0.622 | |

| P+ day | 4.66 | ± | 2.12 | 5.36 | ± | 2.91 | 5.08 | ± | 2.24 | 7.00 | ± | 3.55 | 6.99 | ± | 4.24 | 0.196 | |

| Estrogen (pg/ml) (mean ± SD) |

Day 2 | 42.83 | ± | 29.66 | 49.67 | ± | 16.91 | 52.31 | ± | 19.86 | 48.00 | ± | 26.36 | 50.17 | ± | 23.51 | 0.890 |

| Day 10-12 | 503.42 | ± | 187.38 | 462.17 | ± | 137.92 | 505.54 | ± | 259.17 | 616.08 | ± | 317.34 | 535.17 | ± | 261.35 | 0.590 | |

| P+ day | 376.58 | ± | 192.60 | 238.17 | ± | 94.36 | 353.23 | ± | 179.89 | 363.08 | ± | 190.00 | 336.08 | ± | 213.03 | 0.341 | |

| Progesteron (ng/ml) (mean ± SD) |

Day 2 | 0.33 | ± | 0.25 | 0.39 | ± | 0.31 | 0.67 | ± | 0.57 | 0.32 | ± | 0.17 | 0.48 | ± | 0.20 | 0.059 |

| Day 10-12 | 0.30 | ± | 0.21 | 0.28 | ± | 0.14 | 0.34 | ± | 0.20 | 0.38 | ± | 0.24 | 0.37 | ± | 0.24 | 0.685 | |

| P+ day | 3.82 | ± | 1.50 | 3.90 | ± | 1.46 | 3.05 | ± | 1.33 | 3.55 | ± | 1.70 | 3.06 | ± | 1.34 | 0.448 | |

| Endometrial thickness (mm) (mean ± SD) |

Day 2 | 5.55 | ± | 1.22 | 7.33 | ± | 2.89 | 6.55 | ± | 2.08 | 6.65 | ± | 2.21 | 6.46 | ± | 1.78 | 0.367 |

| Day 10-12 | 9.43 | ± | 1.69 | 9.78 | ± | 1.98 | 10.00 | ± | 2.67 | 10.27 | ± | 1.60 | 12.15 | ± | 2.16 | 0.019 | |

| P+ day | 10.47 | ± | 2.53 | 10.18 | ± | 2.14 | 11.24 | ± | 2.92 | 11.38 | ± | 2.32 | 12.13 | ± | 3.21 | 0.397 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).