Descriptive Statistics

From the corpus of SLRs (

Table 1), the evidence shows higher performance metrics on the side of top-ranked articles. For instance, the average CiteScore of top-ranked SLRs (x̄

Mean-Top = 16.8 with 95%CI

SE[14.83, 18.03]) is much higher than bottom-ranked SLRs (x̄

Mean-Top = 6.14 with 95%CI

SE[5.49, 6.83]), with median values placing more emphasis on the difference between the score of top-ranked (Med = 17.4, IQR = 10.6) and bottom-ranked SLRs (Med = 5.3, IQR = 4.4). The CoV (Coefficient of Variation) suggests similarity in groups, i.e., both samples are highly variable relative to the mean (~0.7). Lastly, it should be noted that 69 articles indexed in SCOPUS did not have an impact factor, out of which 62 articles were bottom-ranked SLRs.

The descriptive statistics of retrieved SLRs suggest that almost a quarter of the sample has no explicit RQ. Next, the CiteScore show slightly higher citation impact of studies with an explicit RQ considering both Median (MedTrue = 9.8, MedFalse = 7.3) and Mean values (x̄CiteScore-True = 11.58 with 95%CISE[10.56, 12.89]; x̄CiteScore-False = 9.93 with 95%CISE[8.51, 11.22]), with higher variation in studies that do have an explicit RQ (CoV = 0.94). The mean difference of PCN indicates a much higher citation rate in studies with the RQ (x̄PCN-True = 90.74 with 95%CISE[78.83, 104.72], x̄PCN-False = 55.61 with 95%CISE[40.94, 72.38])). It is important to note that both samples had the same WoS-IF when comparing Median scores (MedTrue = 3.9, IQRTrue = 5.7; MedFalse = 3.9, IQRFalse = 7.5). These results are similar in Mean scores (x̄WoS-IF-True = 5.57 with 95%CISE[5.05, 6.08], x̄WoS-IF-False = 5.00 with 95%CISE[4.15, 5.84])), which suggests that SLRs with and without RQ do not significantly differ from each other considering publication type.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics RQ Split.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics RQ Split.

| Feature |

RQ |

n |

Med |

Mean |

SE |

95%CIU |

95%CIL |

STD |

CoV |

IQR |

Var |

Min |

Max |

| CiteScore |

False |

97 |

7.30 |

9.93 |

0.70 |

11.22 |

8.51 |

6.93 |

0.70 |

11.60 |

47.97 |

0.00 |

23.60 |

| CiteScore |

True |

294 |

9.80 |

11.58 |

0.64 |

12.89 |

10.56 |

10.91 |

0.94 |

12.80 |

119.09 |

0.00 |

138.00 |

| WoS-IF |

False |

97 |

3.90 |

5.00 |

0.42 |

5.84 |

4.15 |

4.09 |

0.82 |

5.70 |

16.76 |

0.00 |

12.80 |

| WoS-IF |

True |

294 |

3.90 |

5.57 |

0.27 |

6.08 |

5.05 |

4.56 |

0.82 |

7.50 |

20.79 |

0.00 |

35.60 |

| PCN |

False |

97 |

11.00 |

55.61 |

8.12 |

72.38 |

40.94 |

79.9 |

1.44 |

84.0 |

6390 |

0.00 |

392.0 |

| PCN |

True |

294 |

79.50 |

90.74 |

6.54 |

104.72 |

78.33 |

112.1 |

1.24 |

132.0 |

12567 |

0.00 |

1081 |

Finally, after splitting the sample of SLR studies into samples with and without QFL, the results suggest a significantly higher proportion of studies that did not use the RQ framework (nQFL-True = 17, nQFL-False = 374), i.e., QFL when constructing and proposing an explicit RQ. Next, the descriptive statistics indicate almost the same average point estimates when considering CiteScore and WoS-IF between studies with and without QFL. However, there is a slightly higher score when comparing CiteScore mean values in studies without the QFL (x̄CiteScore-False = 11.256 with 95%CISE[8.62, 11.20], x̄CiteScore-True = 9.30 with 95%CISE[10.49, 12.98]), with higher dispersion in studies without QFL explained by CoVQFL-False = 0.91 and CoVQFL-True = 0.5.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics QFL Split.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics QFL Split.

| Feature |

QFL |

n |

Med |

Mean |

SE |

95%CIU |

95%CIL |

STD |

CoV |

IQR |

Var |

Min |

Max |

| CiteScore |

False |

374 |

9.80 |

11.26 |

0.53 |

11.20 |

8.62 |

10.26 |

0.91 |

13.60 |

105.35 |

0.00 |

138.00 |

| CiteScore |

True |

17 |

9.80 |

9.30 |

1.12 |

12.98 |

10.49 |

4.63 |

0.50 |

7.40 |

21.42 |

3.20 |

20.40 |

| WoS-IF |

False |

374 |

3.90 |

5.45 |

0.23 |

5.83 |

4.22 |

4.51 |

0.83 |

7.58 |

20.30 |

0.00 |

35.60 |

| WoS-IF |

True |

17 |

3.90 |

4.92 |

0.74 |

6.12 |

5.05 |

3.03 |

0.62 |

5.20 |

9.18 |

0.30 |

11.10 |

| PCN |

False |

374 |

43.50 |

81.49 |

5.46 |

96.23 |

43.18 |

105.6 |

1.30 |

118.8 |

11151 |

0.00 |

1081.0 |

| PCN |

True |

17 |

73.00 |

93.77 |

28.68 |

98.36 |

77.23 |

118.2 |

1.26 |

145.00 |

13982 |

3.00 |

466.0 |

Overall, the descriptive statistics provide interesting remarks. Namely, a quarter of SLR studies in the engineering-based domain do not have an explicit RQ, while more concerning is the fact that only 4.3% (17/391 SLRs) use an explicit QFL, i.e., RQ framework in designing and constructing their RQ.

Contingency Models

The results (

Table 4) suggest that many articles that contain an explicit RQ are published, regardless of the class of engineering-based SLR defined. However, this difference is more prevalent in top-ranked SLRs when comparing within-group and bottom-ranked SLRs. The results of the contingency table suggest that 54.3% (159/293) propose an explicit RQ are placed within top-ranked SLRs. In contrast, 61.22% (60/98) of SLRs do not provide an explicit RQ and are bottom-ranked SLRs.

The Chi-square test statistics (

Table 5) suggest a significant association between RQ and class (

p = 0.009). After performing the diagnosticity of

p values, the evidence suggests strong evidence favouring the alternative hypothesis (VS-MPR = 11.259), i.e., there exists an association between proposing an explicit RQ and class of SLRs and there is more than ten times higher likelihood of finding the evidence under the alternative hypothesis. The Fisher’s exact test (

Table 6) report a significant association between the class of SLRs and RQ (

p = 0.007). The odds ratio suggests that it is 0.5 less likely that RQ will appear in bottom-ranked SLRs, i.e., the top-ranked SLRs are 1.91 times more likely to propose an explicit RQ. However, although reported statistics are significant, the strength of the relationship shows a small effect size of

φ = 0.138, as recommended by Cohen (1992).

Interestingly, the between-class analysis on whether SLRs have utilised QFL in their RQ design, the results (

Table 7) show almost exact results with no association between them. Thus, there was no reported statistically significant association between QFL and RQ considering Chi-square (

p = 0.812) and Fisher’s test statistic (

p = 0.504).

Independent Samples’ Statistics

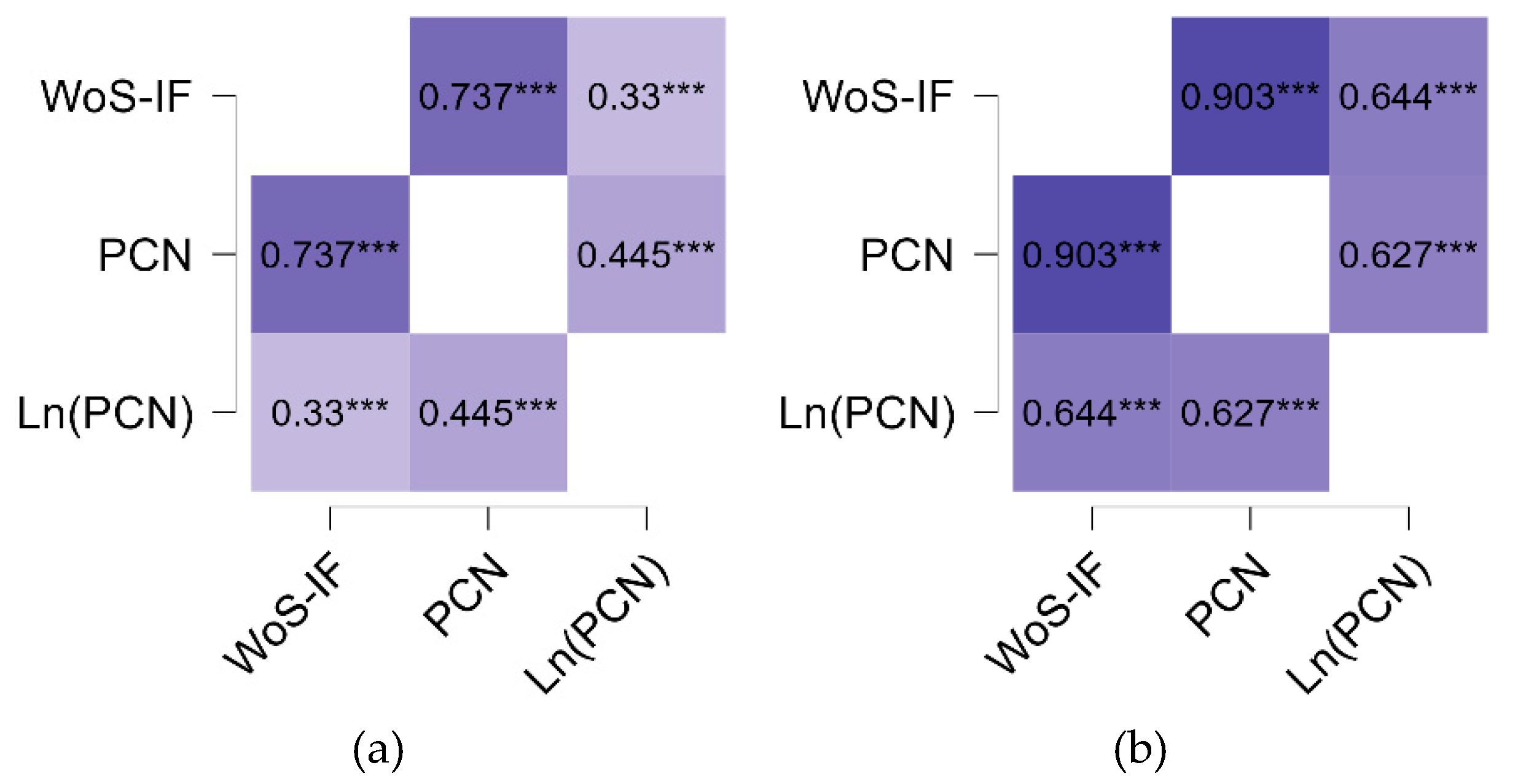

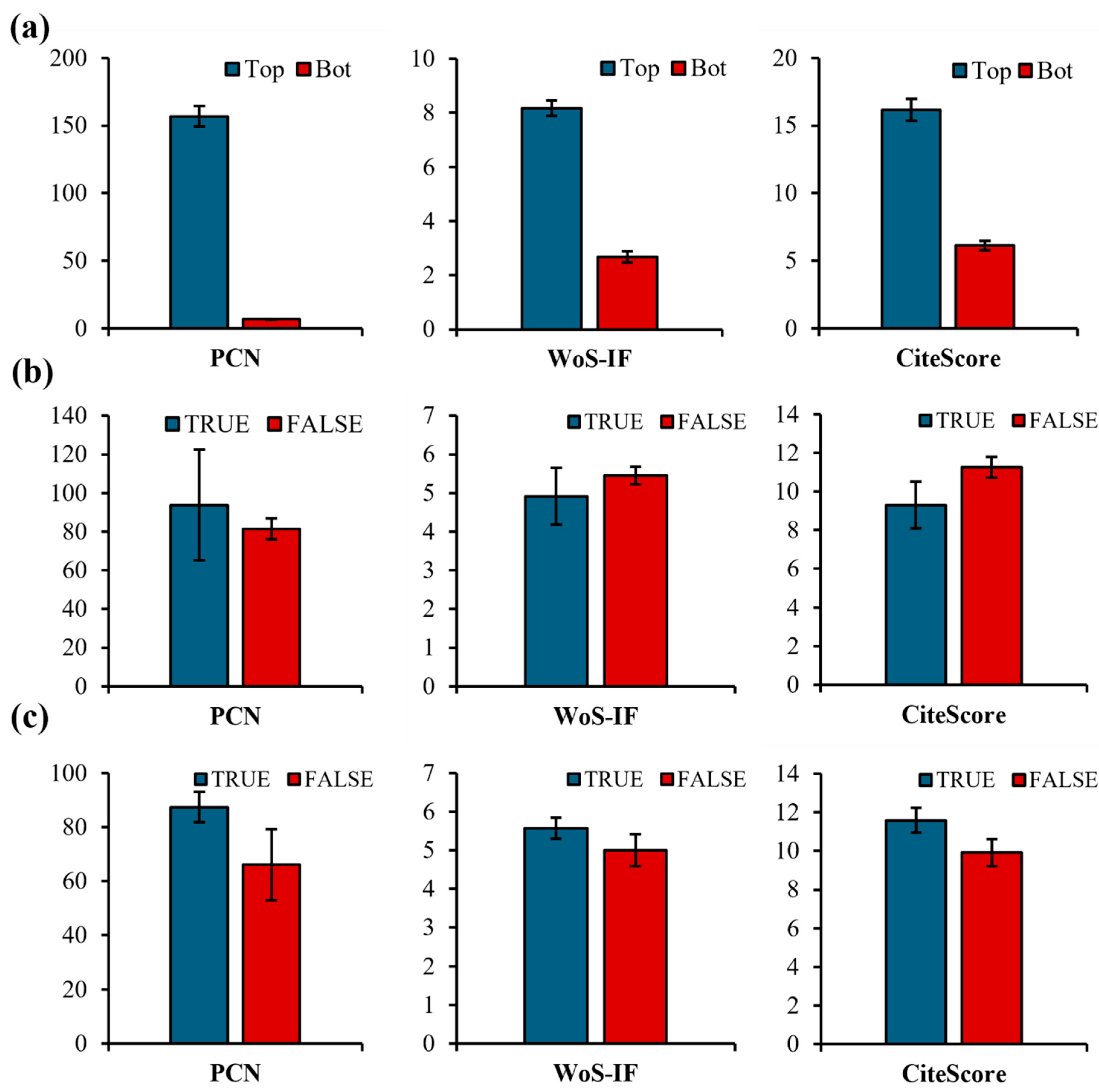

Descriptives are provided visually to gain more insights about the effects of samples. Namely, when comparing top- and bottom-ranked engineering-based SLRs, the data (a) exhibits a difference in means when considering PCN, WoS-IF, and CiteScore. Next, the QFL assessment (

Figure 1b-left) suggests that papers that include QFL tend to receive higher citation counts; however, no statistically significant difference supports such claims. Surprisingly, contrasting QFL in WoS-IF (

Figure 1b-middle) and (

Figure 1b-right), the results show a higher tendency to include QFL in lower-ranked journals considering WoS-IF and CiteScore. Lastly, the RQ analysis (

Figure 1c), suggests that SLRs with an explicit RQ may expect a higher citation rate (

Figure 1c-left). This is also seen more in journals with higher WoS-IF (

Figure 1c-middle) and CiteScore (

Figure 1c-right). Therefore, additional inferential analysis is performed using parametric and non-parametric independent samples t-tests.

The results (

Table 8) suggest that the Student’s t-test did not provide statistically significant results (

p < 0.05) on whether the proposed RQ is seen more in journals with higher CiteScore. For the analysis of means between samples, Welch’s statistic (

p = 0.041) can be considered more suitable given the unequal samples (true = 294, false = 97). However, although Brown-Forsythe did not suggest a violation of equality of variances (

F = 1.075;

p = 0.301), the normality assumption is violated in both samples per Shapiro-Wilk (

WRQ-true = 0.893,

WRQ-false = 0.591,

p < 0.001). Thus, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney

U test suggests that current evidence fails to reject the null (

p = 0.117), which leads to the conclusion that there was not enough evidence that proposing RQ within SLRs is most likely to be present in journals (or conferences) with higher CiteScore. The performed analysis offers similar results when analysing WoS-IF (

p > 0.05). Ultimately, this suggests that although there is a tendency that explicit RQ is most likely to be seen in journals with higher WoS-IF and CiteScore, the findings are inconclusive since the statistically significant difference is only reported per Welch’s t-test statistic but with violation of normality assumption.

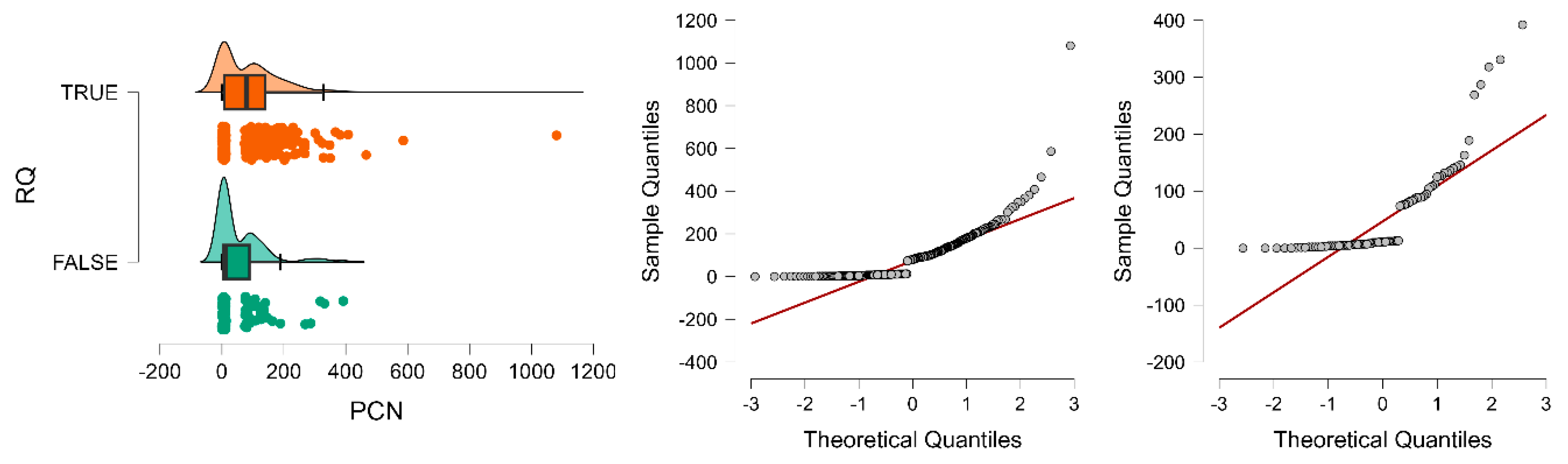

After contrasting the PCN scores based on the RQ split, the analysis suggests statistically significant results. Namely, both Student's (

p = 0.002; VS-MPR = 26.652) and Welch's

t-test (

p < 0.001; VS-MPR = 108.211) suggest the presence of a significant difference. However, due to the presence of extreme values (outliers) of citations in particular studies (

Figure 2-left), the Brown-Forsythe test suggests inequality of variances (

p = 0.004). Shapiro-Wilk shows the absence of normality (

p < 0.001) in both cases (

Figure 2, middle and right). Thus, the interpretation relying on point (mean) estimates does not guarantee rigorous findings. Thus, turning to the Mann-Whitney

U test as a non-parametric alternative, the evidence indeed suggests significant results (

U = 10951,

p < 0.001, VS-MPR = 149.6) but with small effect sizes (RBC = -0.232) per Cohen (2013).

Although the proposed findings indicate the presence of significant differences, a comparison is performed to investigate the presence of an effect within class categories. Thus, after performing the analysis of PCN within top-ranked SLRs, the results (

Table 9) suggest no statistically significant difference in Student’s t-test (

p = 0.086), while Welch’s t-test (

p = 0.050) is on the borderline. Nevertheless, due to the violation of normality and inequality of samples, the Mann-Whitney U test is performed, and results suggest a significant difference (

p = 0.009, VS-MPR = 8.351) with a small effect size (RBC = -0.248). Conversely, the analysis of bottom-ranked SLRs regarding PCN did not show statistically significant results considering both parametric and non-parametric test statistics.

Table 10.

Independent sample test of bottom-ranked SLRs.

Table 10.

Independent sample test of bottom-ranked SLRs.

| |

Test |

Statistic |

df |

p |

VS-MPR |

Effect Size* |

SE Effect Size |

| PCN |

Student |

-0.936 |

194 |

0.175 |

1.206 |

-0.145 |

0.156 |

| |

Welch |

-0.921 |

71.594 |

0.180 |

1.193 |

-0.144 |

0.156 |

| |

Mann-Whitney |

3744.5 |

|

0.200 |

1.143 |

-0.075 |

0.090 |

Overall, a general trend suggests that SLRs with an explicit RQ tend to receive higher PCN, indicating an influence of clearly defined RQ within top-ranked engineering-based SLRs. However, although this is consistent in the retrieved sample, the within-group comparison suggests that this trend is more common in journals with higher CiteScore or WoS-IF. Given that the violation of normality is observed in both samples, parametric Student’s and Welch’s tests show no significant evidence indicating that SLRs with explicit RQs receive more citations. Instead, due to violation of normality, the results of the Mann-Whitney U test support the trend that articles with explicit RQs tend to receive higher citations but within journals with higher CiteScore and WoS-IF. Still, the effect size suggests that practical significance might be limited.