1. Introduction

In today’s increasingly uncertain environment, corporate management faces significant challenges due to the heightened risk of bankruptcy arising from deteriorating business performance. Bankruptcies impose substantial losses on stakeholders, including business partners, investors, and financial institutions. Accordingly, developing models that prevent or enable the early detection of bankruptcy has become essential. While traditional research has relied on statistical approaches, recent advances in machine learning have enabled more objective and accurate predictions.

This study builds on earlier work by applying ensemble learning methods—Random Forest and LightGBM—while addressing key challenges such as feature selection, imbalanced data, and industry-specific modeling. In particular, the study integrates resampling techniques with stepwise feature selection, thereby enhancing model generalization, interpretability, and the ability to uncover sector-specific bankruptcy patterns.

Corporate bankruptcy prediction has long attracted scholarly and practical attention. Foundational studies, including Beaver (1966), Altman (1968), Ohlson (1980), and Zmijewski (1984), demonstrated the predictive power of accounting ratios and introduced discriminant and probit/logit models (Nam and Jinn, 2000). Subsequent refinements included hazard models (Shumway, 2001), industry effects (Chava and Jarrow, 2004), market-based indicators (Hillegeist et al., 2004; Wu, Gaunt, and Gray, 2010), and hybrid approaches integrating accounting, market, and macroeconomic variables (Hernández Tinoco and Wilson, 2013; Ciampi, 2015; Martín and Rojo, 2019). Altman himself and subsequent studies have proposed variations of the Z-score model to extend its applicability to non-manufacturing firms, private companies, and firms in emerging markets (Altman et al., 2017). Lin and McClean (2001) and Varetto (1998) applied data mining and genetic algorithms, while Sun and Shenoy (2007) employed Bayesian networks. Huang et al. (2004) conducted a comparative study using support vector machines and neural networks for credit rating analysis, highlighting the effectiveness of advanced machine learning techniques for financial risk assessment. More recently, Choi and Lee (2018) applied multi-label learning techniques for corporate bankruptcy prediction, demonstrating the potential of advanced machine learning methods to handle multiple bankruptcy indicators simultaneously. These studies provided interpretability but faced limitations in capturing nonlinearities and complex interactions.

Since the 2000s, machine learning has transformed bankruptcy prediction. Ensemble methods, including Breiman’s (2001) Random Forest and Dietterich’s (2000) ensemble strategies, demonstrated the advantages of combining classifiers. Boosting algorithms such as AdaBoost (Heo and Yang, 2014), Gradient Boosting (Chen and Guestrin, 2016), and LightGBM (Ke et al., 2017) proved highly effective. Hybrid frameworks integrated multiple learners (Wang et al., 2010; Tang and Yan, 2021; Yu and Zhang, 2020), while CatBoost-based models further enhanced accuracy (Ben Jabeur et al., 2021; Mishra and Singh, 2022). Comparative studies confirm that ensemble models consistently outperform single classifiers in both stability and predictive performance (Bandyopadhyay and Lang, 2013; Lahsasna et al., 2018; Lee and Chen, 2020; Kraus and Feuerriegel, 2019; Guillén and Salas, 2021). Stacking and meta-learning frameworks have also been proposed (Tsai and Hsu, 2013; Tang, Zhang, and Chawla, 2009). Moreover, multi-industry frameworks such as Lee and Choi (2013) demonstrate the importance of accounting for sectoral heterogeneity in model design.

A persistent methodological challenge is class imbalance. Bankruptcies are rare compared with solvent cases, and classifiers trained on such datasets often achieve inflated accuracy while failing to capture true defaults. Early work by He and Garcia (2009) and Huang and Ling (2005) highlighted methodological biases, and later studies proposed over- and under-sampling approaches. SMOTE (Chawla et al., 2002), SMOTE-ENN (Batista et al., 2004; Liu and Wu, 2021), and SMOTE-IPF (Sáez et al., 2015) effectively rebalance class distributions. Undersampling approaches such as exploratory undersampling (Liu, Wu, and Zhou, 2009) provided alternatives. Reviews confirm the importance of these methods (Fernandez, García, and Herrera, 2018; Fernández et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2014). Neural network studies further revealed imbalance sensitivity (Buda, Maki, and Mazurowski, 2018). More recent work integrated rebalancing with ensemble learning (Zhao and Wang, 2018; Shetty, Musa, and Brédart, 2022). Recent advances also include hybrid approaches that integrate evolutionary algorithms with domain adaptation (Ansah-Narh et al., 2024).

Feature engineering and dimensionality reduction are also critical. While early studies relied on accounting ratios, more recent work incorporated diverse features such as governance (Ciampi, 2015), market variables, and macroeconomic indicators (Sun et al., 2014). Feature selection reduces noise and overfitting (Guyon and Elisseeff, 2003; Tsai, 2009; Jain and Johnson, 2020). Hybrid strategies (Ko, Kim, and Kang, 2021; Pramodh and Ravi, 2016; Hossari and Rahman, 2022; Kotze and Beukes, 2021; García et al., 2019), explainable AI (Lundberg and Lee, 2017; Wu and Wang, 2022; Zhang and Wang, 2021; Giudici and Hadji-Misheva, 2022; Yeh, Chi, and Lin, 2022), and advances in scikit-learn (Pedregosa et al., 2011) have further improved transparency and reproducibility. In addition, Dikshit and Pradhan (2021) demonstrated the applicability of interpretable models in environmental risk prediction, highlighting the transferability of explainable AI across domains.

Deep learning has expanded the methodological toolkit. Neural networks were introduced by Atiya (2001), Lin, Chiu, and Tsai (2010), and Kim (2011), with more recent contributions focusing on sequential and attention-based models (Li, Sun, and Wu, 2022; Kim, Cho, and Ryu, 2022). Ensemble deep learning reviews further highlight the growing promise of these methods (Ganaie and Hu, 2022). BERT adaptations extend to textual features (Kim and Yoon, 2023), while hybrid frameworks combine neural networks with market and macroeconomic data (Zhang and Wang, 2021). Comparative studies highlight their growing competitiveness (Iparraguirre-Villanueva and Cabanillas-Carbonell, 2023). Industry- and country-specific determinants remain key: Korean construction (Heo and Yang, 2014), French SMEs (Mselmi, Lahiani, and Hamza, 2017), crisis contexts (Nam and Jinn, 2000; Narvekar and Guha, 2021), dotcom failures (Chandra, Ravi, and Bose, 2009), firm size and volatility in Pakistan (Rashid, Hassan, and Karamat, 2021), policy uncertainty (Fedorova et al., 2022), and early banking distress detection (Ravisankar and Ravi, 2010) further illustrate contextual variation.

Several meta-studies have synthesized these developments. Bellovary, Giacomino, and Akers (2007) reviewed early research, while Ravi Kumar and Ravi (2007), Alaka et al. (2018), Sun et al. (2014), and Dasilas and Rigani (2024) provided systematic reviews. Xu and Ouenniche (2018) applied DEA benchmarking, Radovanovic and Haas (2023) assessed socio-economic costs, and Razzak, Imran, and Xu (2019) reviewed deep learning for credit scoring. Succurro, Arcuri, and Costanzo (2019) introduced robust PCA, and Sánchez-Medina et al. (2024) investigated bankruptcy resolution prediction. Wu, Gaunt, and Gray (2010) compared alternative models, while Yeh and Lien (2009) analyzed credit card default risks in relation to corporate bankruptcy prediction. Du Jardin (2016) further demonstrated the effectiveness of a two-stage classification strategy, motivating the two-stage approach of this study.

Overall, the literature reveals a clear progression from interpretable statistical models to increasingly complex, data-driven, and explainable frameworks. Prediction success depends not only on algorithmic choice but also on handling imbalanced data, selecting informative features, and incorporating industry-specific determinants. Building on this understanding, the present study adopts a two-stage machine learning framework for bankruptcy prediction among Tokyo Stock Exchange–listed firms. In the first stage, comprehensive learning is performed using 173 financial indicators. In the second stage, wrapper-based feature selection is applied to gradually reduce dimensionality, eliminate noise, and arrive at an optimal seven-feature set. This approach enhances both predictive performance and interpretability.

To capture sector-specific heterogeneity, separate models are constructed for six industries—Construction, Real Estate, Services, Retail, Wholesale, and Electrical Equipment—thus uncovering sectoral bankruptcy determinants and patterns. In addition, three resampling techniques—SMOTE, SMOTE-ENN, and k-means clustering—are incorporated to address class imbalance. Empirical results reveal that Random Forest correctly predicts 566 bankruptcies and LightGBM predicts 451, both substantially outperforming models without feature reduction. By simultaneously addressing four key challenges—methodological choices, dataset design, class imbalance, and industry heterogeneity—this study underscores both its novelty and practical relevance.

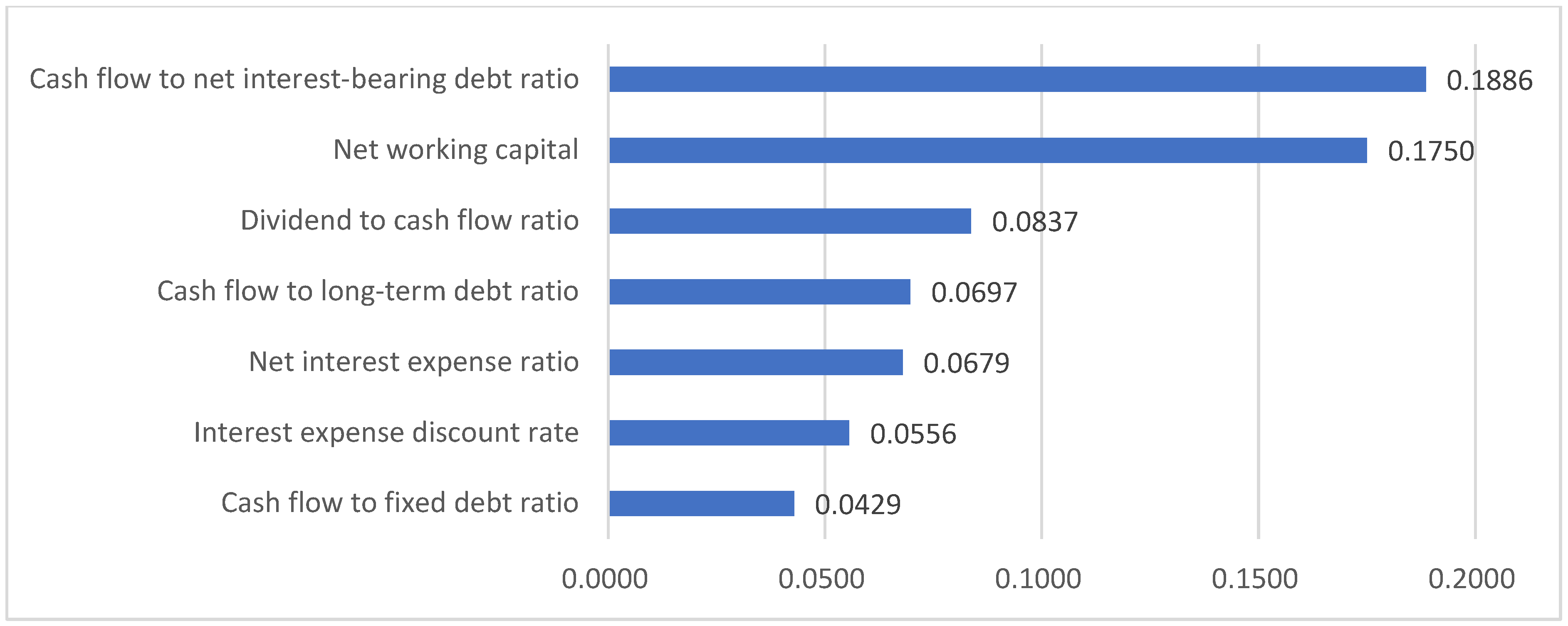

Figure 1.

Random Forest feature importance scores for 173 features under SMOTE-ENN resampling using the financial dataset for the electrical equipment industry.

Figure 1.

Random Forest feature importance scores for 173 features under SMOTE-ENN resampling using the financial dataset for the electrical equipment industry.

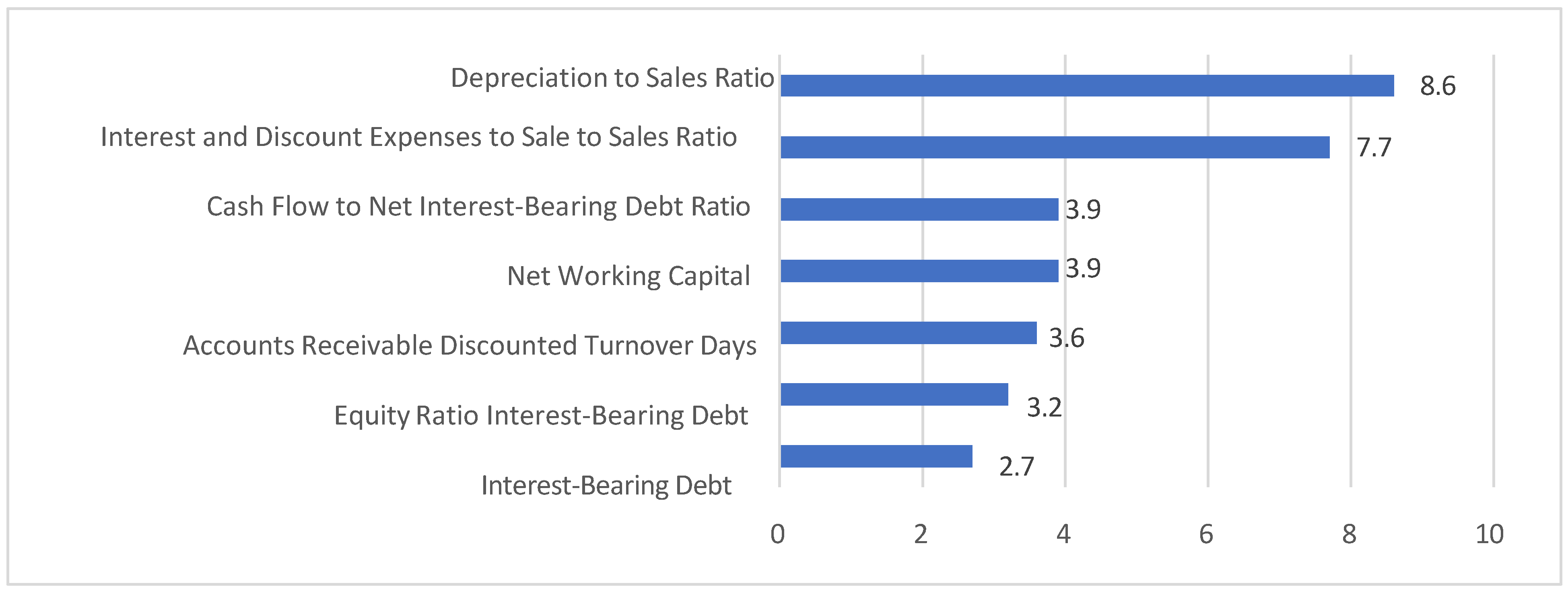

Figure 2.

LightGBM feature importance scores for 173 features under SMOTE-ENN resampling using the financial dataset for the electrical equipment industry.

Figure 2.

LightGBM feature importance scores for 173 features under SMOTE-ENN resampling using the financial dataset for the electrical equipment industry.

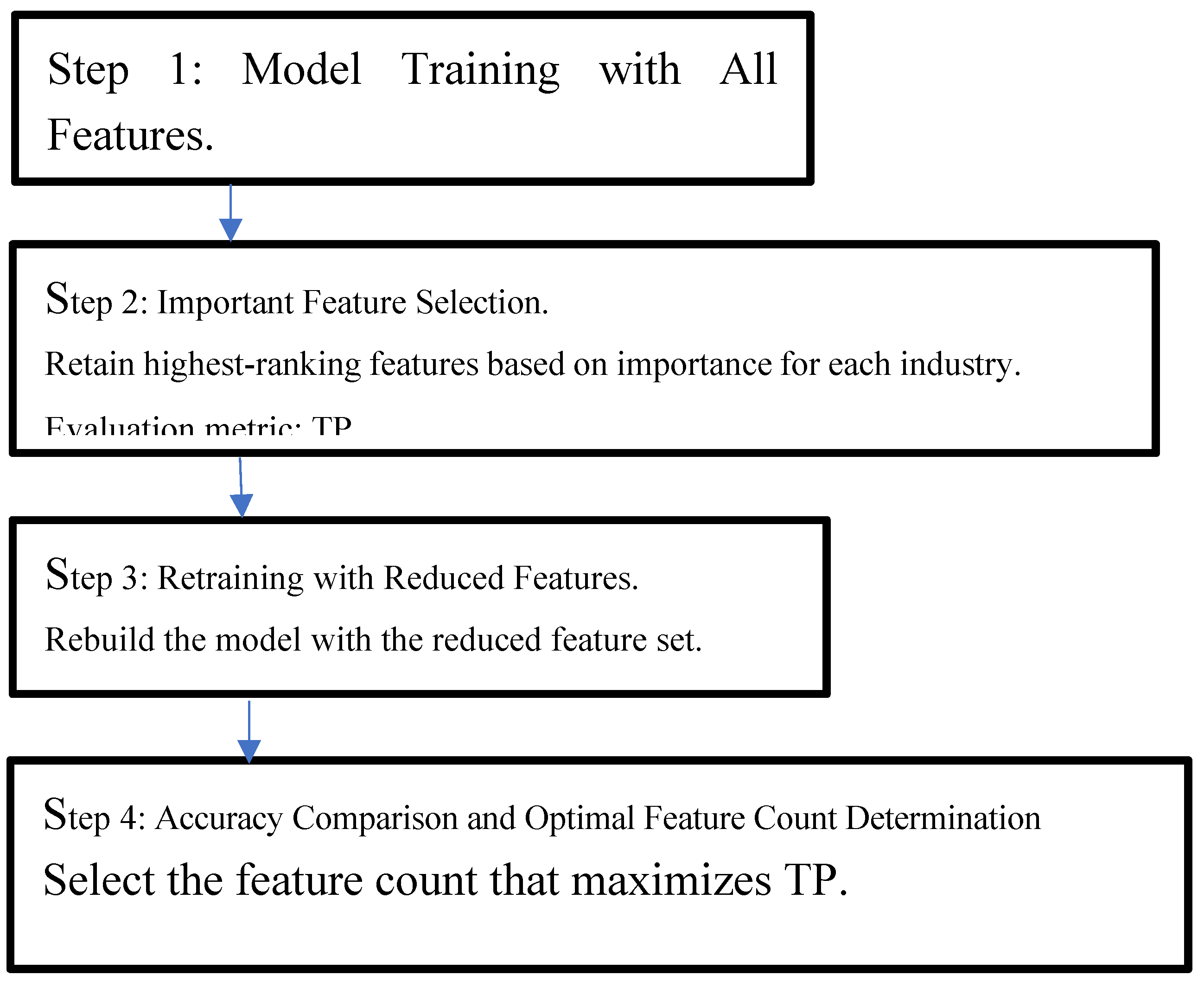

Figure 3.

Workflow of wrapper-based feature selection (Steps 1–4).

Figure 3.

Workflow of wrapper-based feature selection (Steps 1–4).

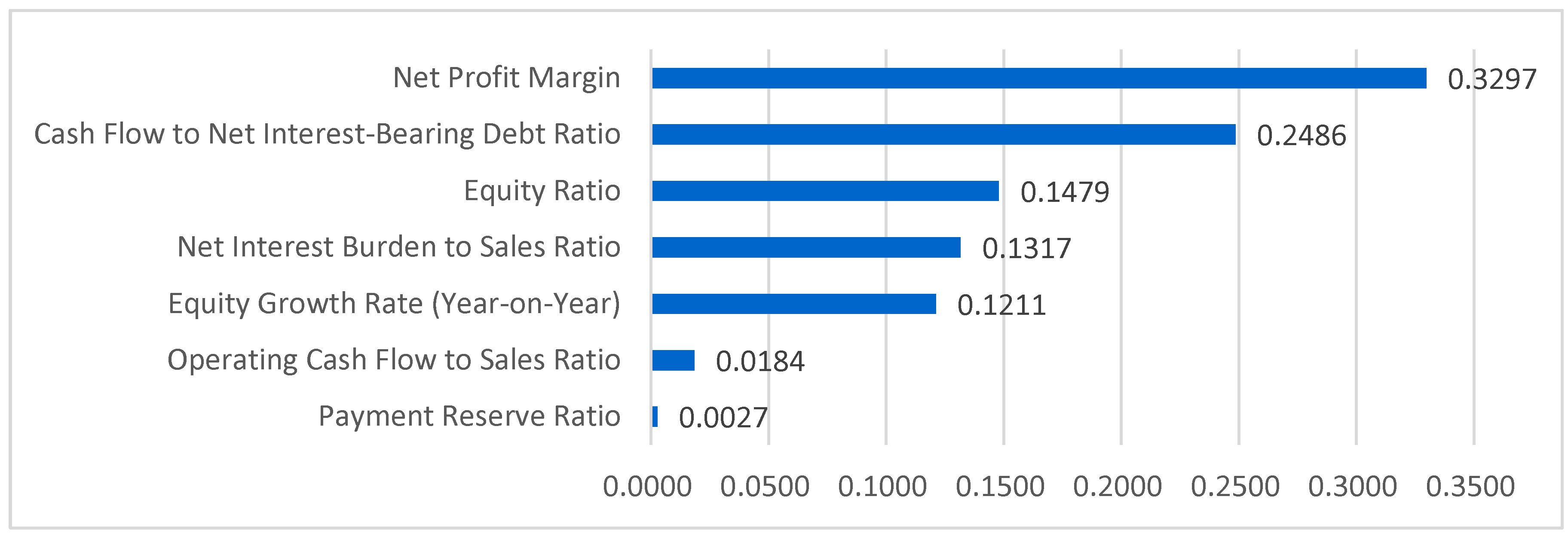

Figure 4.

Importance scores for the top seven features under SMOTE-ENN resampling using the financial dataset for the electrical equipment industry.

Figure 4.

Importance scores for the top seven features under SMOTE-ENN resampling using the financial dataset for the electrical equipment industry.

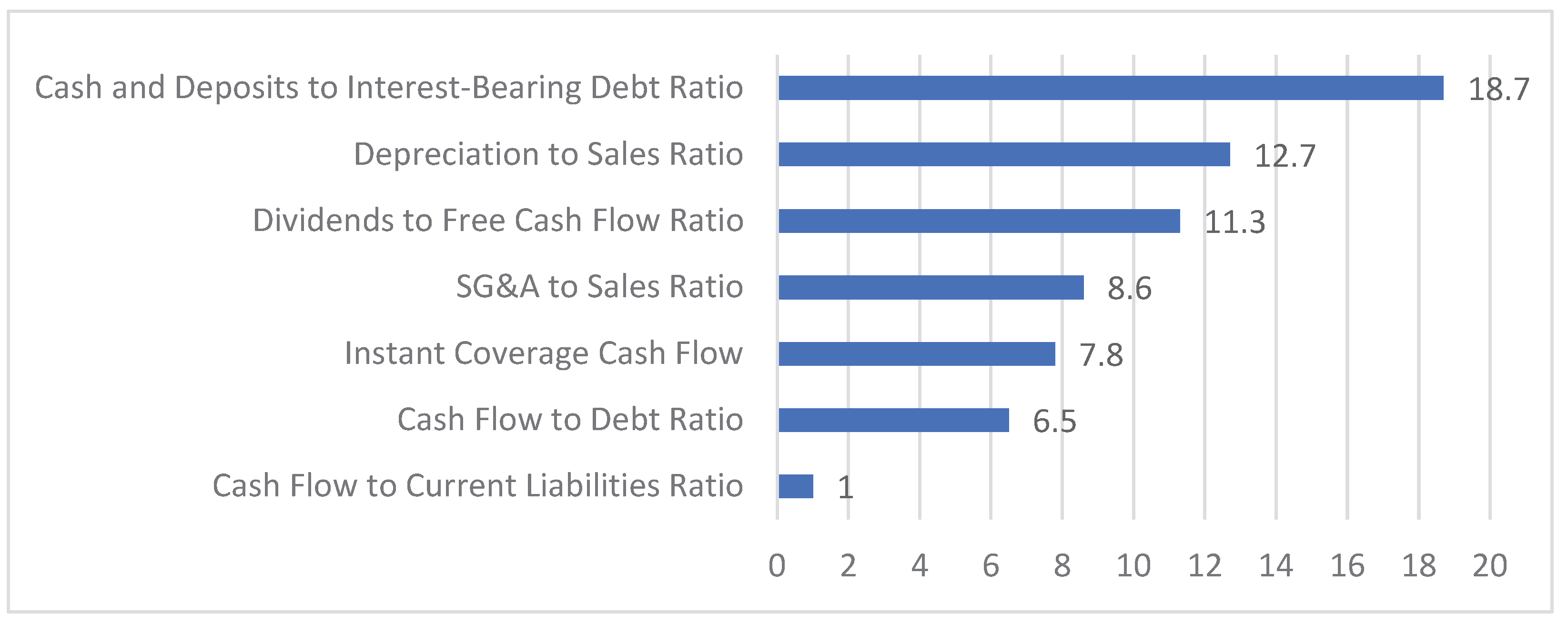

Figure 5.

Importance scores for the top seven features under SMOTE-ENN resampling using the financial dataset for the electrical equipment industry.

Figure 5.

Importance scores for the top seven features under SMOTE-ENN resampling using the financial dataset for the electrical equipment industry.

Table 1.

Datasets.

| Industry |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

| |

Bankrupt |

Non-bankrupt |

Total |

Bankrupt |

Non-bankrupt |

Total |

Bankrupt |

Non-bankrupt |

Total |

| Construction |

42 |

6,280 |

6,322 |

25 |

3,848 |

3,873 |

25 |

3,848 |

3,873 |

| Real estate |

34 |

3,603 |

3,637 |

21 |

2,089 |

2,110 |

21 |

2,089 |

2,110 |

| Service |

25 |

11,445 |

11,470 |

5 |

4,480 |

4,485 |

5 |

4,480 |

4,485 |

| Retail |

23 |

11,531 |

11,554 |

10 |

5,808 |

5,818 |

10 |

5,808 |

5,818 |

| Electrical equipment |

23 |

9,043 |

9,066 |

11 |

4,722 |

4,733 |

11 |

4,722 |

4,733 |

| Wholesale |

16 |

10,935 |

10,951 |

5 |

5,650 |

5,655 |

5 |

5,650 |

5,655 |

| Total |

163 |

52,787 |

52,950 |

77 |

26,597 |

26,674 |

77 |

26,597 |

26,674 |

Table 2.

Financial indicators and features.

Table 2.

Financial indicators and features.

| Classification of financial indicators |

Number of features |

Examples of features |

| Profitability |

47 |

Profit margin |

| Return on capital |

15 |

Return on assets |

| Margin related |

10 |

EBIT 1 margin |

| Productivity |

6 |

Revenue per employee |

| Safety |

35 |

Equity ratio |

| Growth |

15 |

Revenue growth rate (YOY 2) |

| Cash flow |

33 |

Cash flow to net debt ratio |

Table 3.

Hardware and software specifications.

Table 3.

Hardware and software specifications.

| Hardware/Software |

Specification |

| CPU 1

|

Core i9-10885H |

| RAM 2

|

32.0 GB4

|

| OS 3

|

Windows 11 Pro |

| Programming Language |

Python 3.9.7 |

| Machine Learning Package |

scikit-learn |

| Parameter Optimization Package |

Optuna |

Table 4.

Random Forest true positive count by dataset configuration.

Table 4.

Random Forest true positive count by dataset configuration.

| Actual |

Predicted |

| |

Total |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

| 951 |

478 |

284 |

97 |

97 |

Table 5.

Random Forest true positive count by resampling method and dataset configuration.

Table 5.

Random Forest true positive count by resampling method and dataset configuration.

| Resampling |

Actual |

Predicted |

| Total |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

| SMOTE |

317 |

115 |

74 |

19 |

22 |

| SMOTE-ENN |

317 |

177 |

100 |

40 |

37 |

| Kmeans |

317 |

186 |

110 |

38 |

38 |

| Total |

951 |

478 |

284 |

97 |

97 |

Table 6.

Random Forest true positive count by industry and dataset configuration.

Table 6.

Random Forest true positive count by industry and dataset configuration.

| Industry |

Total |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

| |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

| Construction |

276 |

152 |

55.07 |

126 |

75 |

59.52 |

75 |

37 |

49.33 |

75 |

40 |

53.33 |

| Real estate |

228 |

133 |

58.33 |

102 |

69 |

67.65 |

63 |

31 |

49.21 |

63 |

33 |

52.38 |

| Service |

105 |

55 |

52.38 |

75 |

50 |

66.67 |

15 |

3 |

20.0 |

15 |

2 |

13.33 |

| Retail |

129 |

58 |

44.96 |

69 |

39 |

56.52 |

30 |

10 |

33.3 |

30 |

9 |

30.00 |

| Electrical equipment |

135 |

59 |

43.70 |

69 |

31 |

44.93 |

33 |

15 |

45.45 |

33 |

13 |

39.39 |

| Wholesale |

78 |

21 |

26.92 |

48 |

20 |

41.67 |

15 |

1 |

6.67 |

15 |

0 |

0.00 |

| Total |

951 |

478 |

50.26 |

317 |

284 |

89.59 |

317 |

97 |

30.6 |

317 |

97 |

30.60 |

Table 7.

Random Forest true positive count and recall rate by resampling method and industry.

Table 7.

Random Forest true positive count and recall rate by resampling method and industry.

| Industry |

Total |

SMOTE |

SMOTE-ENN |

K-means |

| |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

| Construction |

276 |

152 |

55.07 |

92 |

35 |

39.13 |

92 |

57 |

61.96 |

92 |

59 |

64.13 |

| Real estate |

228 |

133 |

58.33 |

76 |

37 |

48.68 |

76 |

50 |

65.79 |

76 |

46 |

60.53 |

| Service |

105 |

55 |

52.38 |

35 |

15 |

42.86 |

35 |

18 |

51.43 |

35 |

22 |

62.86 |

| Retail |

129 |

58 |

44.96 |

43 |

9 |

20.93 |

43 |

24 |

55.81 |

43 |

25 |

58.14 |

| Electrical equipment |

135 |

59 |

43.70 |

45 |

15 |

33.33 |

45 |

20 |

44.44 |

45 |

24 |

53.33 |

| Wholesale |

78 |

21 |

26.92 |

26 |

3 |

11.54 |

26 |

8 |

30.77 |

26 |

10 |

38.46 |

| Total |

951 |

478 |

50.26 |

317 |

115 |

36.28 |

317 |

177 |

55.84 |

317 |

186 |

58.68 |

Table 8.

LightGBM true positive count by dataset configuration.

Table 8.

LightGBM true positive count by dataset configuration.

| Actual |

Predicted |

| |

Total |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

| 951 |

420 |

264 |

58 |

97 |

Table 9.

LightGBM true positive count by resampling method and dataset configuration.

Table 9.

LightGBM true positive count by resampling method and dataset configuration.

| Resampling |

Actual |

Predicted |

|

| |

|

Total |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

|

| SMOTE |

317 |

141 |

85 |

21 |

35 |

|

| SMOTE-ENN |

317 |

149 |

98 |

22 |

29 |

|

| K-means |

317 |

129 |

81 |

15 |

33 |

|

| Total |

951 |

420 |

264 |

58 |

97 |

|

Table 10.

LightGBM true positive count and recall rate by industry and dataset configuration.

Table 10.

LightGBM true positive count and recall rate by industry and dataset configuration.

| Industry |

Total |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

| |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

| Construction |

105 |

61 |

58.10 |

75 |

47 |

62.70 |

15 |

6 |

40.00 |

15 |

8 |

53.17 |

| Real estate |

228 |

139 |

60.96 |

102 |

62 |

60.78 |

63 |

36 |

57.14 |

63 |

41 |

65.69 |

| Service |

78 |

34 |

43.95 |

48 |

24 |

49.28 |

15 |

2 |

10.00 |

15 |

9 |

60.87 |

| Retail |

129 |

59 |

45.67 |

69 |

47 |

68.00 |

30 |

8 |

26.67 |

30 |

4 |

13.33 |

| Electrical equipment |

276 |

67 |

24.30 |

126 |

50 |

39.58 |

75 |

0 |

0.00 |

75 |

17 |

22.92 |

| Wholesale |

135 |

59 |

43.86 |

69 |

35 |

50.72 |

33 |

7 |

21.21 |

33 |

17 |

52.17 |

| Total |

951 |

420 |

44.15 |

489 |

264 |

54.08 |

231 |

58 |

25.32 |

231 |

97 |

41.95 |

Table 11.

LightGBM true positive count and recall rate by resampling method and industry.

Table 11.

LightGBM true positive count and recall rate by resampling method and industry.

| Industry |

Total |

SMOTE |

SMOTE-ENN |

K-means |

| |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

| Construction |

105 |

61 |

58.10 |

35 |

19 |

54.29 |

35 |

21 |

60.00 |

35 |

21 |

60.00 |

| Real estate |

228 |

139 |

60.96 |

76 |

47 |

61.84 |

76 |

49 |

64.47 |

76 |

44 |

57.89 |

| Service |

78 |

34 |

43.95 |

26 |

12 |

46.15 |

26 |

11 |

42.31 |

26 |

11 |

42.31 |

| Retail |

129 |

59 |

45.67 |

43 |

21 |

48.83 |

43 |

22 |

51.16 |

43 |

17 |

39.53 |

| Electrical equipment |

276 |

67 |

24.30 |

92 |

24 |

26.09 |

92 |

28 |

30.43 |

92 |

15 |

16.30 |

| Wholesale |

135 |

59 |

43.86 |

45 |

19 |

42.22 |

45 |

19 |

42.22 |

45 |

21 |

46.67 |

| Total |

951 |

420 |

44.15 |

317 |

141 |

44.48 |

317 |

149 |

47.00 |

317 |

129 |

40.69 |

Table 12.

Changes in true positive count by feature count.

Table 12.

Changes in true positive count by feature count.

| Features |

4 |

5 |

7 |

15 |

130 |

161 |

| TP |

559 |

560 |

566 |

529 |

504 |

483 |

Table 13.

Random Forest true positive counts by dataset configuration.

Table 13.

Random Forest true positive counts by dataset configuration.

| Actual |

Predicted |

| |

Total |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

| 951 |

566 |

303 |

142 |

121 |

Table 14.

Random Forest true positive counts by resampling method and dataset configuration.

Table 14.

Random Forest true positive counts by resampling method and dataset configuration.

| Resampling |

Actual |

Predicted |

|

| |

|

Total |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

|

| SMOTE |

317 |

149 |

84 |

34 |

31 |

|

| SMOTE-ENN |

317 |

211 |

113 |

52 |

46 |

|

| K-means |

317 |

206 |

106 |

56 |

44 |

|

| Total |

951 |

566 |

303 |

142 |

121 |

|

Table 15.

Random Forest true positive count and recall rate by industry and dataset configuration.

Table 15.

Random Forest true positive count and recall rate by industry and dataset configuration.

| Industry |

Total |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

| |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

| Construction |

276 |

172 |

62.32 |

126 |

87 |

69.05 |

75 |

44 |

58.67 |

75 |

41 |

54.67 |

| Real estate |

228 |

157 |

68.86 |

102 |

71 |

69.61 |

63 |

43 |

68.25 |

63 |

43 |

68.25 |

| Service |

105 |

57 |

54.29 |

75 |

52 |

69.33 |

15 |

3 |

20.00 |

15 |

2 |

13.33 |

| Retail |

129 |

71 |

55.04 |

69 |

45 |

65.22 |

30 |

14 |

46.67 |

30 |

12 |

40.00 |

| Electrical equipment |

276 |

61 |

62.32 |

126 |

18 |

69.05 |

75 |

29 |

58.67 |

75 |

14 |

54.67 |

| Wholesale |

78 |

48 |

61.54 |

48 |

30 |

62.50 |

50 |

9 |

60.00 |

15 |

9 |

60.00 |

| Total |

951 |

566 |

59.52 |

489 |

303 |

61.96 |

231 |

142 |

61.47 |

231 |

121 |

52.38 |

Table 16.

Random Forest true positive count and recall rate by resampling method and industry.

Table 16.

Random Forest true positive count and recall rate by resampling method and industry.

| Industry |

Total |

SMOTE |

SMOTE-ENN |

K-means |

| |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

| Construction |

276 |

172 |

62.32 |

92 |

43 |

46.74 |

92 |

67 |

72.83 |

92 |

62 |

67.39 |

| Real estate |

228 |

157 |

68.86 |

76 |

46 |

60.53 |

76 |

60 |

78.95 |

76 |

51 |

67.11 |

| Service |

105 |

57 |

54.29 |

35 |

16 |

45.71 |

35 |

21 |

60.00 |

35 |

20 |

57.14 |

| Retail |

129 |

71 |

55.04 |

43 |

18 |

41.86 |

43 |

26 |

60.47 |

43 |

27 |

62.79 |

| Electrical equipment |

135 |

61 |

45.19 |

45 |

14 |

31.11 |

45 |

20 |

44.44 |

45 |

27 |

60.00 |

| Wholesale |

78 |

48 |

61.54 |

26 |

12 |

46.15 |

26 |

17 |

65.38 |

26 |

19 |

73.08 |

| Total |

951 |

566 |

59.52 |

317 |

149 |

47.00 |

317 |

211 |

66.56 |

317 |

206 |

64.98 |

Table 17.

Comparison of the top seven features identified by Random Forest from the full set with the seven features selected for the optimized model.

Table 17.

Comparison of the top seven features identified by Random Forest from the full set with the seven features selected for the optimized model.

| 173 Features |

7 Features |

| Cash Flow to Net Interest-Bearing Debt Ratio |

Net Profit Margin |

| Net Working Capital |

Cash Flow to Net Interest-Bearing Debt Ratio |

| Dividends to Cash Flow Ratio |

Equity Ratio |

| Cash Flow to Long-Term Debt Ratio |

Net Interest Burden to Sales Ratio |

| Net Interest Burden to Sales Ratio |

Equity Growth Rate (Year-on-Year) |

| Interest and Discount Expenses to Sales Ratio |

Operating Cash Flow to Sales Ratio |

| Cash Flow to Fixed Liabilities Ratio |

Payment Reserve Ratio |

Table 18.

LightGBM true positive count by dataset configuration.

Table 18.

LightGBM true positive count by dataset configuration.

| Actual |

Predicted |

| |

Total |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

| 951 |

451 |

283 |

87 |

81 |

Table 20.

LightGBM true positive count by industry and dataset configuration.

Table 20.

LightGBM true positive count by industry and dataset configuration.

| Industry |

Total |

Financial |

Investment-financing |

Comparison |

| |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

| Construction |

105 |

72 |

68.57 |

75 |

53 |

72.60 |

15 |

10 |

66.67 |

15 |

9 |

60.00 |

| Real estate |

228 |

138 |

60.53 |

102 |

72 |

70.59 |

63 |

34 |

53.97 |

63 |

32 |

50.79 |

| Service |

78 |

42 |

53.85 |

48 |

32 |

66.67 |

15 |

5 |

33.33 |

15 |

5 |

33.33 |

| Retail |

129 |

44 |

34.11 |

69 |

34 |

49.28 |

30 |

2 |

6.67 |

30 |

8 |

26.67 |

| Electrical equipment |

276 |

93 |

33.70 |

126 |

53 |

42.06 |

75 |

25 |

33.33 |

75 |

15 |

20.00 |

| Wholesale |

135 |

62 |

45.93 |

69 |

37 |

53.62 |

33 |

12 |

36.36 |

33 |

13 |

39.39 |

| Total |

951 |

451 |

47.42 |

489 |

281 |

57.46 |

231 |

88 |

38.10 |

231 |

82 |

35.50 |

Table 21.

LightGBM true positive count and recall rate by resampling method and industry.

Table 21.

LightGBM true positive count and recall rate by resampling method and industry.

| Industry |

Total |

SMOTE |

SMOTE -ENN |

K-means |

| |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

Actual |

Predicted |

Recall |

| Construction |

105 |

72 |

68.57 |

35 |

28 |

80.00 |

35 |

28 |

80.00 |

35 |

17 |

48.57 |

| Real estate |

228 |

138 |

60.53 |

76 |

59 |

77.63 |

76 |

60 |

78.95 |

76 |

19 |

25.00 |

| Service |

78 |

43 |

55.13 |

26 |

15 |

57.69 |

26 |

16 |

61.65 |

26 |

2 |

7.69 |

| Retail |

129 |

43 |

33.33 |

43 |

19 |

44.19 |

43 |

22 |

51.16 |

43 |

3 |

6.98 |

| Electrical equipment |

276 |

93 |

33.70 |

92 |

54 |

58.70 |

92 |

39 |

42.39 |

92 |

0 |

0.00 |

| Wholesale |

135 |

62 |

45.93 |

45 |

25 |

55.56 |

45 |

27 |

60.00 |

45 |

10 |

22.22 |

| Total |

951 |

451 |

47.42 |

317 |

199 |

62.78 |

317 |

191 |

60.25 |

317 |

61 |

19.24 |

Table 22.

Comparison of the top seven features identified by LightGBM from the full set with the seven features selected for the optimized model.

Table 22.

Comparison of the top seven features identified by LightGBM from the full set with the seven features selected for the optimized model.

| 173 Features |

7 Features |

| Depreciation to Sales Ratio |

Cash and Deposits to Interest-Bearing Debt Ratio |

| Interest and Discount Expenses to Sales Ratio |

Depreciation to Sales Ratio |

| Net Working Capital |

Dividends to Free Cash Flow Ratio |

| Cash Flow to Net Interest-Bearing Debt Ratio |

SG&A to Sales Ratio |

| Accounts Receivable Discounted Turnover Days |

Instant Coverage Cash Flow |

| Equity Ratio |

Cash Flow to Debt Ratio |

| Interest-Bearing Debt |

Cash Flow to Current Liabilities Ratio |