Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

II. Two Series Resistors Model

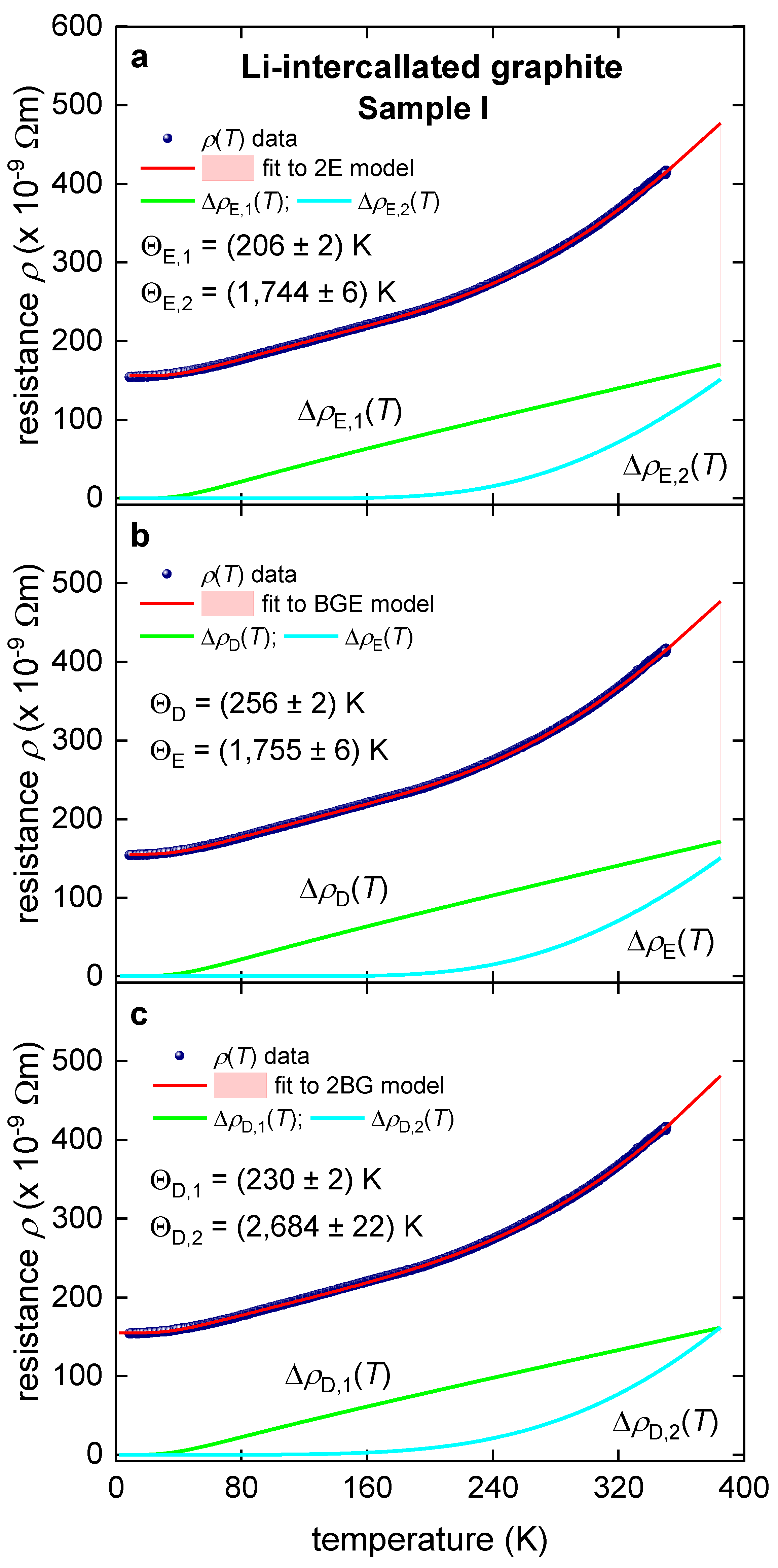

III. Einstein and Debye Temperatures in Intercalated Graphite Samples

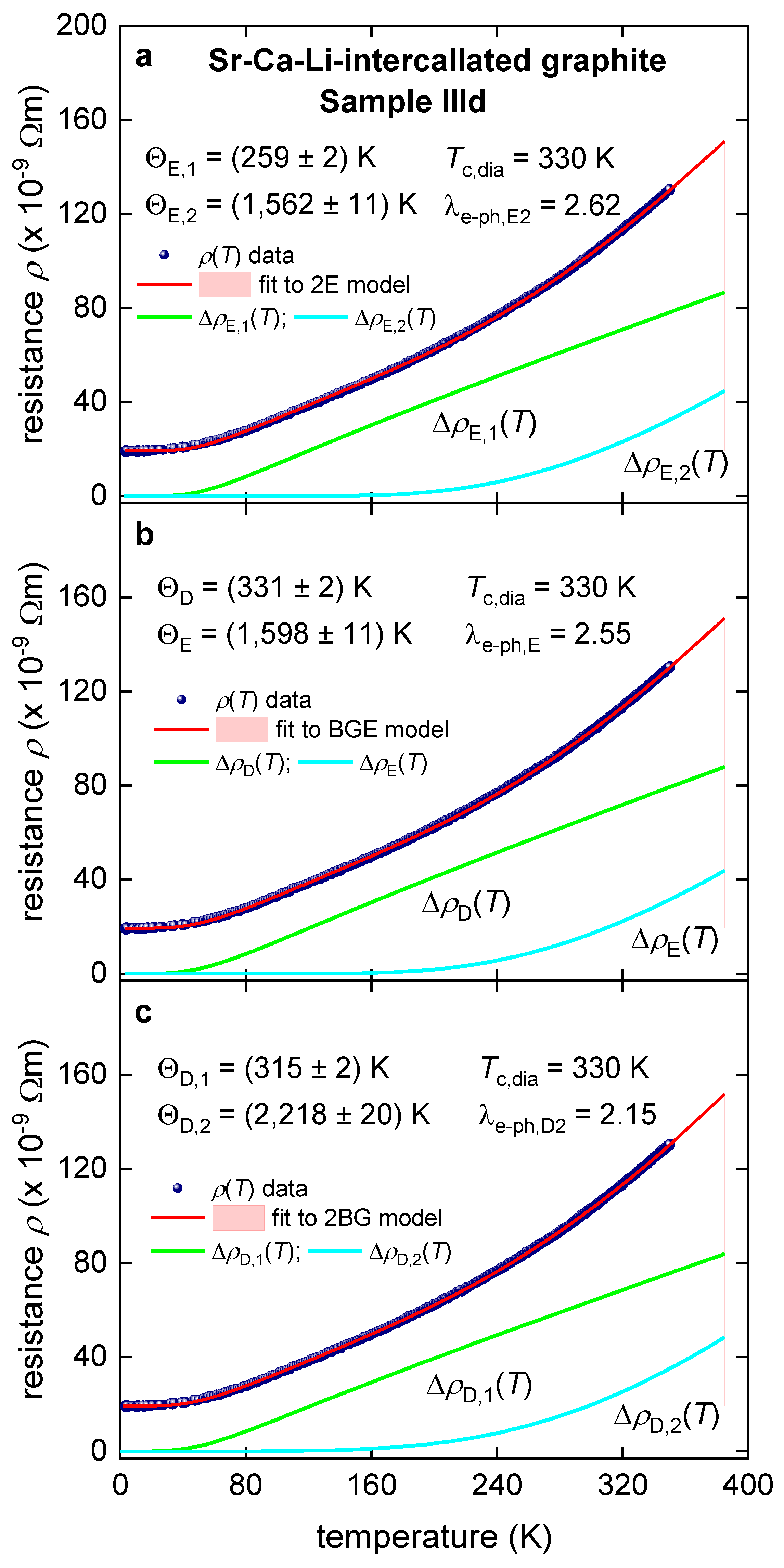

IV. Electron-Phonon Coupling Constant in Room Temperature Superconductor Sr-Ca-Li-Graphite

V. Discussion

VI. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Drozdov, A.P.; Eremets, M.I.; Troyan, I.A.; Ksenofontov, V.; Shylin, S.I. Conventional superconductivity at 203 kelvin at high pressures in the sulfur hydride system. Nature 2015, 525, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Naumov, I. I., Hoffmann, R., Ashcroft, N. W. & Hemley, R. J. Potential high- T c superconducting lanthanum and yttrium hydrides at high pressure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 6990–6995 (2017).

- Drozdov, A.P.; Kong, P.P.; Minkov, V.S.; Besedin, S.P.; Kuzovnikov, M.A.; Mozaffari, S.; Balicas, L.; Balakirev, F.F.; Graf, D.E.; Prakapenka, V.B.; et al. Superconductivity at 250 K in lanthanum hydride under high pressures. Nature 2019, 569, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somayazulu, M.; Ahart, M.; Mishra, A.K.; Geballe, Z.M.; Baldini, M.; Meng, Y.; Struzhkin, V.V.; Hemley, R.J. Evidence for Superconductivity above 260 K in Lanthanum Superhydride at Megabar Pressures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 027001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.-L.; et al. Predicted hot superconductivity in LaSc 2 H 24 under pressure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, (2024).

- Minkov, V.S.; Prakapenka, V.B.; Greenberg, E.; Eremets, M.I. A Boosted Critical Temperature of 166 K in Superconducting D3S Synthesized from Elemental Sulfur and Hydrogen. Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 19132–19136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Minkov, V.S.; Mozaffari, S.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chariton, S.; Prakapenka, V.B.; Eremets, M.I.; Balicas, L.; Balakirev, F.F. High-temperature superconductivity on the verge of a structural instability in lanthanum superhydride. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; et al. Superconductivity above 180 K in Ca-Mg Ternary Superhydrides at Megabar Pressures. http://arxiv.org/abs/2312.06090 (2023).

- Kong, P.; Minkov, V.S.; Kuzovnikov, M.A.; Drozdov, A.P.; Besedin, S.P.; Mozaffari, S.; Balicas, L.; Balakirev, F.F.; Prakapenka, V.B.; Chariton, S.; et al. Superconductivity up to 243 K in the yttrium-hydrogen system under high pressure. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilia, B.; et al. The 2021 room-temperature superconductivity roadmap. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 34, 183002 (2022).

- Drozdov, A. P., Eremets, M. I. & Troyan, I. A. Superconductivity above 100 K in PH3 at high pressures. http://arxiv.org/abs/1508.06224 (2015).

- Chen, W.; et al. High-Temperature Superconducting Phases in Cerium Superhydride with a Tc up to 115 K below a Pressure of 1 Megabar. Phys Rev Lett 127, 117001 (2021).

- Troyan, I. A., Semenok, D. V., Sadakov, A. V., Lyubutin, I. . S. & Pudalov, V. M. PROGRESS, PROBLEMY I PERSPEKTIVY KOMNATNO-TEMPERATURNOY SVERKhPROVODIMOSTI. Žurnal èksperimentalʹnoj i teoretičeskoj fiziki. 2024, 166, 74–88. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; et al. Enhancement of superconducting properties in the La–Ce–H system at moderate pressures. Nat Commun 14, 2660 (2023).

- Zhou, D.; Semenok, D.V.; Duan, D.; Xie, H.; Chen, W.; Huang, X.; Li, X.; Liu, B.; Oganov, A.R.; Cui, T. Superconducting praseodymium superhydrides. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaax6849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Semenok, D.; Shutov, G.; Zhou, D.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wu, X.; Luther, S.; Helm, T.; et al. Unusual metallic state in superconducting A15-type La4H23. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenok, D.V.; Kvashnin, A.G.; Ivanova, A.G.; Svitlyk, V.; Fominski, V.Y.; Sadakov, A.V.; Sobolevskiy, O.A.; Pudalov, V.M.; Troyan, I.A.; Oganov, A.R. Superconductivity at 161 K in thorium hydride ThH10: Synthesis and properties. Mater. Today 2020, 33, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyan, I. A.; et al. High-temperature superconductivity in hydrides. Physics-Uspekhi 65, 748–761 (2022).

- Chen, W.; Semenok, D.V.; Kvashnin, A.G.; Huang, X.; Kruglov, I.A.; Galasso, M.; Song, H.; Duan, D.; Goncharov, A.F.; Prakapenka, V.B.; et al. Synthesis of molecular metallic barium superhydride: pseudocubic BaH12. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; et al. Soft superconductivity in covalent bismuth dihydride BiH$_2$ under extreme conditions. http://arxiv.org/abs/2505.12062 (2025).

- Troyan, I. A.; et al. Non-Fermi-Liquid Behavior of Superconducting SnH 4. Advanced Science 10, (2023).

- Semenok, D.V.; Troyan, I.A.; Ivanova, A.G.; Kvashnin, A.G.; Kruglov, I.A.; Hanfland, M.; Sadakov, A.V.; Sobolevskiy, O.A.; Pervakov, K.S.; Lyubutin, I.S.; et al. Superconductivity at 253 K in lanthanum–yttrium ternary hydrides. Mater. Today 2021, 48, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyan, I. A.; et al. Anomalous High-Temperature Superconductivity in YH 6. Advanced Materials 33, 2006832 (2021).

- Semenok, D.V.; Troyan, I.A.; Sadakov, A.V.; Zhou, D.; Galasso, M.; Kvashnin, A.G.; Ivanova, A.G.; Kruglov, I.A.; Bykov, A.A.; Terent'EV, K.Y.; et al. Effect of Magnetic Impurities on Superconductivity in LaH10. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2204038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; et al. Stoichiometric Ternary Superhydride LaBeH8 as a New Template for High-Temperature Superconductivity at 110 K under 80 GPa. Phys Rev Lett 130, 266001 (2023).

- Ma, C.; et al. Synthesis of medium-entropy alloy superhydride (La,Y,Ce)H10±x with high-temperature superconductivity under high pressure. Phys Rev B 111, 024505 (2025).

- Bi, J.; Nakamoto, Y.; Zhang, P.; Shimizu, K.; Zou, B.; Liu, H.; Zhou, M.; Liu, G.; Wang, H.; Ma, Y. Giant enhancement of superconducting critical temperature in substitutional alloy (La,Ce)H9. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, D.; Liu, Y.; Tian, F.; Li, D.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, H.; Liu, B.; Tian, W.; Cui, T. Pressure-induced metallization of dense (H2S)2H2 with high-Tc superconductivity. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Hao, X.; Wei, X.; He, X.-L.; Liu, H.; Ma, L.; Liu, G.; Wang, H.; Niu, J.; Wang, S.; et al. Superconductivity above 105 K in Nonclathrate Ternary Lanthanum Borohydride below Megabar Pressure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 13797–13804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; et al. High-Temperature Superconducting Phase in Clathrate Calcium Hydride CaH6 up to 215 K at a Pressure of 172 GPa. Phys Rev Lett 128, 167001 (2022).

- Sun, Y.; Lv, J.; Xie, Y.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y. Route to a Superconducting Phase above Room Temperature in Electron-Doped Hydride Compounds under High Pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 097001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Nakamoto, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Zou, B.; Shimizu, K.; Liu, H.; Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; et al. Stabilization of superconductive La–Y alloy superhydride with Tc above 90 K at megabar pressure. Mater. Today Phys. 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Lu, K.; Zhang, S.; Min, B.; Zhang, J.; Shi, L.; Feng, S.; Liu, Q.; et al. Superconductivity discovered in niobium polyhydride at high pressures. Mater. Today Phys. 2023, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Synthesis and superconductivity in yttrium superhydrides under high pressure. Chinese Physics B 31, 106201 (2022).

- Li, X.; Huang, X.; Duan, D.; Pickard, C.J.; Zhou, D.; Xie, H.; Zhuang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, B.; et al. Polyhydride CeH9 with an atomic-like hydrogen clathrate structure. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.; Shan, P.; Yang, L.; Yue, B.; Yang, P.; Liu, Z.; Sun, J.; Dai, J.; Yu, H.; Yin, Y.; et al. Possible superconductivity at ∼70 K in tin hydride SnHx under high pressure. Mater. Today Phys. 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salke, N.P.; Esfahani, M.M.D.; Zhang, Y.; Kruglov, I.A.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Greenberg, E.; Prakapenka, V.B.; Liu, J.; Oganov, A.R.; et al. Synthesis of clathrate cerium superhydride CeH9 at 80-100 GPa with atomic hydrogen sublattice. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; He, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Min, B.; Zhang, J.; Lu, K.; Zhao, J.; Shi, L.; Peng, Y.; et al. Superconductivity above 80 K in polyhydrides of hafnium. Mater. Today Phys. 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, P.; et al. Molecular Hydride Superconductor BiH 4 with T c up to 91 K at 170 GPa. J Am Chem Soc 147, 4375–4381 (2025).

- Huang, G.; et al. Synthesis of superconducting phase of La 0.5 Ce 0.5 H 10 at high pressures. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 36, 075702 (2024).

- Chen, L.-C.; Luo, T.; Cao, Z.-Y.; Dalladay-Simpson, P.; Huang, G.; Peng, D.; Zhang, L.-L.; Gorelli, F.A.; Zhong, G.-H.; Lin, H.-Q.; et al. Synthesis and superconductivity in yttrium-cerium hydrides at high pressures. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.-Y.; et al. Probing superconducting gap in CeH$_9$ under pressure. ArXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/2401.12682 (2024).

- Ma, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhou, M.; Liu, G.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y. Hydrogen-Vacancy-Induced Stable Superconducting Niobium Hydride at High Pressure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 11028–11035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racioppi, S. & Zurek, E. Quantum Effects or Theoretical Artifacts? A Computational Reanalysis of Hydrogen at High-Pressure. ArXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/2510.02098 (2025).

- Ma, L.; et al. High Pressure Superconducting transition in Dihydride BiH$_2$ with Bismuth Open-Channel Framework. Phys Rev Lett https://doi.org/10.1103/kjnw-n6ds (2025). [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; et al. Room-Temperature Superconductivity at 298 K in Ternary La-Sc-H System at High-pressure Conditions. ArXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/2510.01273 (2025).

- Du, F.; Balakirev, F.F.; Minkov, V.S.; Smith, G.A.; Maiorov, B.; Kong, P.P.; Drozdov, A.P.; Eremets, M.I. Tunneling Spectroscopy at Megabar Pressures: Determination of the Superconducting Gap in Sulfur. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 036002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Drozdov, A.P.; Minkov, V.S.; Balakirev, F.F.; Kong, P.; Smith, G.A.; Yan, J.; Shen, B.; Gegenwart, P.; Eremets, M.I. Superconducting gap of H3S measured by tunnelling spectroscopy. Nature 2025, 641, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, P.; Chen, W.; Huang, X.; Chatterjee, S.; Huang, B.; Kobrin, B.; Lyu, Y.; Smart, T.J.; Block, M.; Wang, E.; et al. Imaging the Meissner effect in hydride superconductors using quantum sensors. Nature 2024, 627, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marathamkottil, A. H. M.; et al. X-ray Diffraction and Electrical Transport Imaging of Superconducting Superhydride (La,Y)H10. (2025).

- Liu, L.; et al. Evidence for the Meissner Effect in the Nickelate Superconductor La3Ni2O7−δ Single Crystal Using Diamond Quantum Sensors. Phys Rev Lett 135, 096001 (2025).

- Ku, C.-H.; Atanov, O.; Yip, K.Y.; Wang, W.; Lam, S.T.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Poon, T.F.; et al. Point-contact Andreev reflection spectroscopy of layered superconductors with device-integrated diamond anvil cells. Rev. Sci. Instruments 2025, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietwyk, K.J.; Shaji, A.; Robertson, I.O.; Healey, A.J.; Singh, P.; Scholten, S.C.; Reineck, P.; Broadway, D.A.; Tetienne, J.-P. Practical limits to spatial resolution of magnetic imaging with a quantum diamond microscope. AVS Quantum Sci. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Imaging magnetic flux trapping in lanthanum hydride using diamond quantum sensors. ArXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/2510.21877 (2025).

- Eremets, M. I. , Minkov, V. S., Drozdov, A. P. & Kong, P. P. The characterization of superconductivity under high pressure. Nat Mater 23, 26–27 (2024).

- Minkov, V.S.; Ksenofontov, V.; Bud’kO, S.L.; Talantsev, E.F.; Eremets, M.I. Magnetic flux trapping in hydrogen-rich high-temperature superconductors. Nat. Phys. 2023, 19, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkov, V. S.; et al. Revaluation of the lower critical field in superconducting H$_3$S and LaH$_{10}$ (Nature Comm. 13, 3194, 2022). http://arxiv.org/abs/2408.12675 (2024).

- Minkov, V.S.; Bud’kO, S.L.; Balakirev, F.F.; Prakapenka, V.B.; Chariton, S.; Husband, R.J.; Liermann, H.P.; Eremets, M.I. Magnetic field screening in hydrogen-rich high-temperature superconductors. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, T.F.T.; Fang, Y.; Errea, I.; Sanna, A.; Marques, M.A.L. Searching Materials Space for Hydride Superconductors at Ambient Pressure. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; et al. Design of High- T c Quaternary Hydrides Under Moderate Pressures Through Substitutional Doping. Adv Funct Mater 35, (2025).

- Jiang, Q.; et al. Prediction of Room-Temperature Superconductivity in Quasi-Atomic H 2 -Type Hydrides at High Pressure. Advanced Science 11, (2024).

- Belli, F.; Torres, S.; Contreras-García, J.; Zurek, E. Refining Tc Prediction in Hydrides via Symbolic-Regression-Enhanced Electron-Localization-Function-Based Descriptors. Ann. der Phys. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M. F.; et al. Synthesis of Mg2IrH5 : A potential pathway to high- Tc hydride superconductivity at ambient pressure. Phys Rev B 110, 214513 (2024).

- Rastkhadiv, M. A. Revisiting YH$_9$ Superconductivity and Predicting High-T$_c$ in GdYH$_5$. ArXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/2510.10720 (2025).

- Talantsev, E.F. Primary Superconducting Parameters of Highly Compressed Nonclathrate Ternary Hydride LaB2H8. Phys. Met. Met. 2025, 126, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkov, V. S.; et al. Long-Term Stability of Superconducting Metal Superhydrides. http://arxiv.org/abs/2507.08009 (2025).

- Talantsev, E. F. Structural and superconducting parameters of highly compressed H3S. [CrossRef]

- Wrona, I.A.; Niegodajew, P.; Durajski, A.P. A recipe for an effective selection of promising candidates for high-temperature superconductors among binary hydrides. Mater. Today Phys. 2024, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; et al. High-Throughput Study of Ambient-Pressure High-Temperature Superconductivity in Ductile Few-Hydrogen Metal-Bonded Perovskites. Adv Funct Mater 34, (2024).

- Huang, H.; Yan, X.; Wang, M.; Du, M.; Song, H.; Liu, Z.; Duan, D.; Cui, T.; Wei, X. High-Temperature Superconductivity of Thermodynamically Stable Fluorite-Type Hydrides at Ambient Pressure. Adv. Sci. 2025, e12696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksenofontov, V. , Minkov, V. S., Drozdov, A. P., Pöschl, U. & Eremets, M. I. Signs of Possible High-Temperature Superconductivity in Graphite Intercalated with Lithium-Based Alloys. ArXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/2510.03256 (2025).

- McMillan, W.L. Transition Temperature of Strong-Coupled Superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 1968, 167, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynes, R. McMillan's equation and the Tc of superconductors. Solid State Commun. 1972, 10, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantsev, E.F. Advanced McMillan’s equation and its application for the analysis of highly-compressed superconductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2020, 33, 094009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantsev, E.F.; Stolze, K. Resistive transition of hydrogen-rich superconductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2021, 34, 064001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantsev, E.F. The electron–phonon coupling constant and the Debye temperature in polyhydrides of thorium, hexadeuteride of yttrium, and metallic hydrogen phase III. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 130, 195901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errea, I. Superconducting hydrides on a quantum landscape. J. Physics: Condens. Matter 2022, 34, 231501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickard, C. J. , Errea, I. & Eremets, M. I. Superconducting Hydrides Under Pressure. Annu Rev Condens Matter Phys 11, 57–76 (2020).

- Errea, I.; Calandra, M.; Pickard, C.J.; Nelson, J.; Needs, R.J.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Mauri, F. High-Pressure Hydrogen Sulfide from First Principles: A Strongly Anharmonic Phonon-Mediated Superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 157004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Errea, I.; Calandra, M.; Pickard, C.J.; Nelson, J.R.; Needs, R.J.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Mauri, F. Quantum hydrogen-bond symmetrization in the superconducting hydrogen sulfide system. Nature 2016, 532, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errea, I.; Belli, F.; Monacelli, L.; Sanna, A.; Koretsune, T.; Tadano, T.; Bianco, R.; Calandra, M.; Arita, R.; Mauri, F.; et al. Quantum crystal structure in the 250-kelvin superconducting lanthanum hydride. Nature 2020, 578, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; et al. The Maximum $T_c$ of Conventional Superconductors at Ambient Pressure. http://arxiv.org/abs/2502.18281 (2025).

- Pallecchi, I.; et al. Experimental investigation of electronic interactions in collapsed and uncollapsed LaFe2As2 phases. Phys Rev B 108, 014512 (2023).

- Yang, K.; et al. Charge fluctuations above TCDW revealed by glasslike thermal transport in kagome metals AV3Sb5 (A=K,Rb,Cs). Phys Rev B 107, 184506 (2023).

- Poole, C. P. , Farach, H., Creswick, R. & Prozorov, R. Superconductivity. (Academic Press, London, UK, 2007).

- Ni, D.; Mudiyanselage, R.S.D.; Xu, X.; Mun, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, W.; Cava, R.J. Layered polymorph of titanium triiodide. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2022, 6, 124001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouquet, F.; Wang, Y.; A Fisher, R.; Hinks, D.G.; Jorgensen, J.D.; Junod, A.; E Phillips, N. Phenomenological two-gap model for the specific heat of MgB 2. EPL (Europhysics Lett. 2001, 56, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wälti, Ch.; et al. Strong electron-phonon coupling in superconducting MgB2: A specific heat study. Phys Rev B 64, 172515 (2001).

- Wang, A.; et al. Magnetic mixed valent semimetal EuZnSb2 with Dirac states in the band structure. Phys Rev Res 2, 033462 (2020).

- Shang, T.; et al. Enhanced T c and multiband superconductivity in the fully-gapped ReBe 22 superconductor. New J Phys 21, 073034 (2019).

- Bloch, F. Zum elektrischen Widerstandsgesetz bei tiefen Temperaturen. Eur. Phys. J. A 1930, 59, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüneisen, E. Die Abhängigkeit des elektrischen Widerstandes reiner Metalle von der Temperatur. Ann. der Phys. 1933, 408, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantsev, E.F. An approach to identifying unconventional superconductivity in highly-compressed superconductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2020, 33, 124001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantsev, E.F. The dominance of non-electron–phonon charge carrier interaction in highly-compressed superhydrides. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2021, 34, 115001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczuk, T.; Królak, S.; Cava, R.J. Superconductivity of Ta-Hf and Ta-Zr alloys: Potential alloys for use in superconducting devices. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2023, 7, 064802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; et al. Superconductivity with High Upper Critical Field in the Cubic Centrosymmetric η-Carbide Nb 4 Rh 2 C 1−δ. ACS Materials Au 1, 55–61 (2021).

- Jonas, D.G.C.; Biswas, P.K.; Hillier, A.D.; Mayoh, D.A.; Lees, M.R. Quantum muon diffusion and the preservation of time-reversal symmetry in the superconducting state of type-I rhenium. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, L020503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, H.; Ogunbunmi, M.O.; Tong, X.; Wang, Q.; Graf, D.; Pudełko, W.R.; Liu, Y.; Lei, H.; et al. Robust three-dimensional type-II Dirac semimetal state in SrAgBi. npj Quantum Mater. 2023, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susner, M.A.; Bhatia, M.; Sumption, M.D.; Collings, E.W. Electrical resistivity, Debye temperature, and connectivity in heavily doped bulk MgB2 superconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 103916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putti, M.; D'Agliano, E.G.; Marrè, D.; Napoli, F.; Tassisto, M.; Manfrinetti, P.; Palenzona, A.; Rizzuto, C.; Massidda, S. Electron transport properties of MgB2 in the normal state. Eur. Phys. J. B 2002, 25, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; et al. Physical properties and electronic structure of Sr2Cr3As2O2 containing CrO2 and Cr2As2 square-planar lattices. Phys Rev B 92, 205107 (2015).

- Wiesmann, H.; et al. Simple Model for Characterizing the Electrical Resistivity in A−15 Superconductors. Phys Rev Lett 38, 782–785 (1977).

- Varshney, D. Impurity, phonon and electron contributions to the electrical resistivity of single-crystal MgB2. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2006, 19, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.R. Electrical resistivity of an Einstein solid. Phys. Rev. B 1974, 9, 2778–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsook, U.; Tanthum, P. Universal resistivity from electron-phonon interaction based on Einstein model: Application to near-room temperature superconductors. Next Mater. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xu, S.; Cheng, Z.; Hashemi, N.; Deng, C.; Wang, X. The defect level and ideal thermal conductivity of graphene uncovered by residual thermal reffusivity at the 0 K limit. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 10101–10110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.-X.; Kang, W.; Cheng, Z.-F.; Zheng, R.-L. Temperature-Dependent Debye Temperature and Specific Capacity of Graphene. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2016, 33, 126501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, E.; Varshney, V.; Roy, A.K. Thermal properties of graphene: Fundamentals and applications. MRS Bull. 2012, 37, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewary, V.K.; Yang, B. Singular behavior of the Debye-Waller factor of graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 125416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreh, R.; Shnieg, N.; Zabel, H. Effective and Debye temperatures of alkali-metal atoms in graphite intercalation compounds. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 1311–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.B.; Dynes, R.C. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors reanalyzed. Phys. Rev. B 1975, 12, 905–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenok, D. Computational design of new superconducting materials and their targeted experimental synthesis. PhD Thesis; Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology (2023). [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J. , Cooper, L. N. & Schrieffer, J. R. Theory of Superconductivity. Physical Review 108, 1175–1204 (1957).

- G. M. Eliashberg. Interactions between Electrons and Lattice Vibrations in a Superconductor. Sov. Phys.–JETP 11, 696 (1960).

- Riley, G.N.; Malozemoff, A.P.; Li, Q.; Fleshler, S.; Holesinger, T.G. The freeway model: New concepts in understanding supercurrent transport in Bi-2223 tapes. JOM 1997, 49, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadifi, H.; Ouali, A.; Grigorescu, C.; Faqir, H.; Monnereau, O.; Tortet, L.; Vacquier, G.; Boulesteix, C. Superconductive percolation in Bi-based superconductor/Bi-based insulator composites: case of Bi-2223/Bi-2310 and Bi-2212/BiFeO3. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2000, 13, 1174–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshurun, Y.; Malozemoff, A.P.; Shaulov, A. Magnetic relaxation in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1996, 68, 911–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElfresh, M.; Yeshurun, Y.; Malozemoff, A.; Holtzberg, F. Remanent magnetization, lower critical fields and surface barriers in an YBa2Cu3O7 crystal. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. its Appl. 1990, 168, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eley, S.; Miura, M.; Maiorov, B.; Civale, L. Universal lower limit on vortex creep in superconductors. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mchenry, M.; Sutton, R. Flux pinning and dissipation in high temperature oxide superconductors. Prog. Mater. Sci. 1994, 38, 159–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maley, M. P. , Willis, J. O., Lessure, H. & McHenry, M. E. Dependence of flux-creep activation energy upon current density in grain-aligned YBa2Cu3O7-x. Phys Rev B 42, 2639–2642 (1990).

- Eley, S.; Willa, R.; Chan, M.K.; Bauer, E.D.; Civale, L. Vortex phases and glassy dynamics in the highly anisotropic superconductor HgBa2CuO4+δ. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, H. M.; et al. Plastic vortex creep and dimensional crossovers in the highly anisotropic superconductor HgBa2CuO4+x. Phys Rev B 107, 104509 (2023).

- Iida, K.; Hänisch, J.; Tarantini, C. Fe-based superconducting thin films on metallic substrates: Growth, characteristics, and relevant properties. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2018, 5, 031304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).