Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: In the context of reproductive health, women have the right to positive birth experiences that safeguard both physical integrity and emotional well-being. Within this framework, we conducted a systematic review aiming to synthesize evidence on women’s experiences -both positive and non-positive- during childbirth in formal healthcare settings, classify these experiences, describe their prevalence, and assess their impact on women’s self-perceived health. Methods: The protocol was prior registered, and the review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Searches were conducted in PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, and Google Scholar. The risk of bias was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute tools. Results: A total of 40 studies from 14 countries were included, encompassing 80,295 women. Findings revealed a broad spectrum of positive and non-positive experiences, latter with prevalence rates ranging from 4.5% to 61.3%. Moreover, 7 of the 40 studies (n = 50,395 women) documented instances of disrespectful and abusive care practices. Reported prevalence ranged from 2.4% to 83.4% for non-consensual procedures, 0.8% to 24.4% for non-dignified care, and 5.4% to 48% for abandonment of care. Conclusions: Our findings suggest that there is room for improvement related to the childbirth experience. Promoting positive birth experiences and sensitizing healthcare professionals to improve respectful maternity care are key priorities. In this regard, adopting a patient-centered model may represent a paradigm shift, empowering women to make informed decisions and enhancing maternal health outcomes.

Keywords:

- This review offers a comprehensive synthesis of women’s childbirth experiences—both positive and non-positive—within formal healthcare facilities.

- To our knowledge, it represents the first systematic attempt to classify women’s experiences of disrespectful and abusive care during facility-based childbirth.

- The findings highlight the urgent need to ensure physical and emotional support that respects women’s preferences, beliefs, and values, fully aligned with the principles of patient-centered care.

Introduction

Objectives

- Describe women´s experiences during childbirth in formal healthcare institutions.

- Classify women´s experiences during childbirth in formal healthcare institutions.

- Describe the prevalence of these experiences across different countries and cultures.

- Determine the impact of these experiences on self-perceived women's health in aspects related to physical, psychological, and social domains.

Method

Information Sources

Search Strategy

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Study Design

Study Participants

Geographical Location

Time Frame

Outcome/s

Settings

Selection Process

Data Collection Process

Synthesis Methods

Risk of Bias Assessment

Results

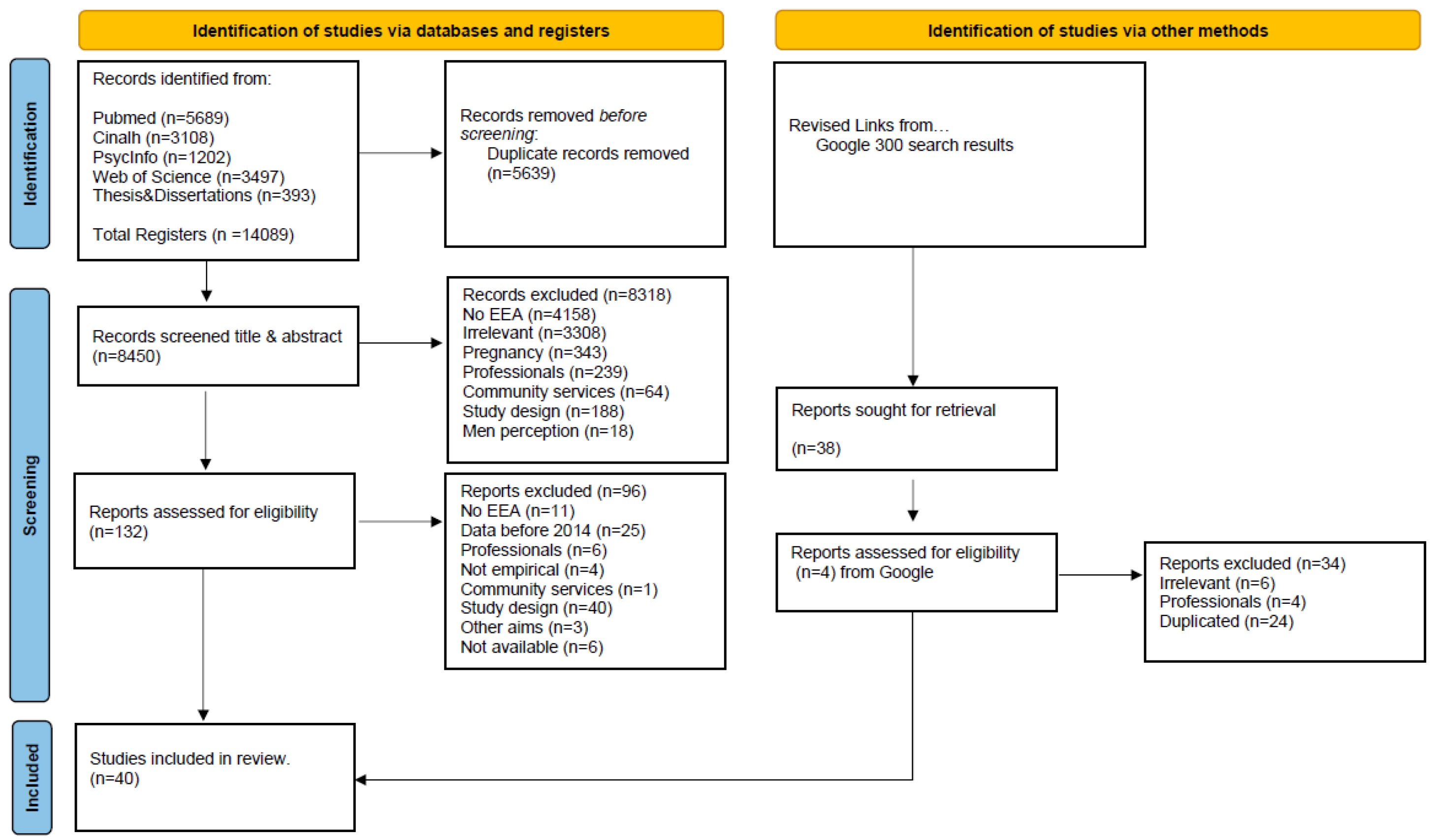

Search Results

Sample Characteristics

Methodological Data of Studies

| Author | Country | Inclusion criteria | Sample (m_age; sd) Range age Groups |

Nationality Race or Ethnicity |

Labor* | Parity | Mode of birth | Birth Plan | Non-Positive Birth Experience (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basso,AM, 2016 | Portugal | Women with internet access | N=519 30 – 35 years |

NR | Induction 33.6% | Primip 79.0% | Eutocic 21.6% Inst 49.7% CS 28.7% |

Total 13.9% | NR |

| Carquillat et al., 2016 |

Switzerland | Women speaking, writing, reading French, primiparous, singleton fetus, gestational up to 37 weeks, and newborn not separated for medical reasons during the maternity stay. | n=291 (30.8; 4.7) Spontaneous n=150 Instrumental n=55 ElectCS n=20 EmergCS n=60 |

Swiss/ European 86% |

Induction 43.2% |

Primip 100% | Eutocic 51% Inst 19% CS 30% |

Total 20.8% | 22.9 |

| Perdok et al., 2018 |

Netherlands | Women attended during their puerperium by midwifery care. | n=187 (31.4; 4.1) Midwife care primary n=136 Midwife care at labor n=36 ObstCare primary n=15 ObstCare labor n=36 |

Dutch 98% | Induction 12.8% | Primip 41.7% | Eutocic 87.2 % Inst 9.1% CS 3.7% |

NR | 27.3 |

| Baranowska et al. 2019 |

Poland | Women who declared that they had given birth in 2017 or 2018 |

n=8378 26 – 35 years |

NR | NR | NR | Eutocic 61.3 % Inst 2.5% CS 36.2% |

NR | NR |

| Ryan et al., 2019 | Ireland | Women with one previous CS. | n=347 (34.9; NR) ElectCS n=62 EmergCS n=285 |

Irish 79.5% | NR | Primip 0% | Eutocic 0% Inst 0% CS 100% |

NR | 11 ElectCS; 6.1 EmergCS; 15.9 |

| Baptie et al., 2020 | United Kingdom |

Participants must have had their baby within the last 12 months and be >18 years old. | n=222 (NR) 18 – 44 years |

NR | NR | Primip 63.1% | Eutocic NR Inst NR CS 23.5% |

NR | NR |

| Mena-Tudela et al., 2020 |

Spain | Women attended to in a Spanish public or private hospital to give birth naturally or by CS, or for miscarriage. |

n=17541 (NR) Public Healthcare n=11450 Mixed care n=4261 Private n=1830 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | Total 73.5% | 54.5 |

| Mena-Tudela et al.,2021 |

Spain | Women attended to in a Spanish public or private hospital to give birth naturally or by CS, or for miscarriage. | n=17541 (NR) Public Healthcare n=11450 Mixed care n=4261 Private n=1830 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 61.3 |

| Chabbert et al.,2021 |

France | Women >18 years who gave birth to healthy, full-term, singleton infants. | n=265 (31.5; NR) 18 – 46 years |

NR | Induction 37.4% |

Primip 46.5% | Eutocic 57.9% Inst 16.5% CS 25.6% |

NR | 23.3 |

| Author | Country | Inclusion criteria | Sample (m_age; sd) Range age Groups |

Nationality Race or Ethnicity |

Labor* |

Parity | Mode of birth | Birth Plan | Non-Positive Birth Experience (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| González-de la Torre et al., 2021 |

Spain | Pregnant women with single pregnancy, eutocic vaginal delivery or dystocic-instrumental vaginal delivery. | n=257 (31.6; 5.6) 18 – 45 years |

NR | Induction 44.0% |

Primip 51.4% |

Eutocic 89.9% Inst 10.1% CS 0% |

NR | 50.5 |

| Oelhafen et al.,2021 |

Switzerland | Women aged 18 years or older who had given birth in Switzerland within the previous 12 months. | n=6054 (NR) 18 – 46 years |

Swiss 81.6% | Induction 28.0% |

Primip 57.9% | Eutocic 65.3% Inst 11.4% CS 23.3% |

NR | NR |

| Rodriguez et al.,2021 |

Spain | Participants with legal age; being able to understand enough Spanish language; having a minimum amount of computer knowledge to answer an online questionnaire. | n=194 (32.8; 5.5) 20 – 48 years High Hospital n=97 Med Hospital n=97 |

Spanish 85.0% | Induction 40.7% | Primip 53.1% | Eutocic 63.9% Inst 34% CS 3.6% |

Total 76.3% High Hosp 78% Med Hosp 74% |

33.1 |

| Westergren et al.,2021 |

Sweden | Healthy women with normal pregnancies and expected to have uncomplicated vaginal births. | n=239 (30.8;4,6) With BP n=129 Without BP n=110 |

Swedish 90.0% | Induction 68.2% | Primip 46.4% | Eutocic NR Inst 6.3% CS 9.6% |

Total 54% | 22.8 |

| Deherder et al., 2022 |

Netherlands | Knowledge of the Dutch language, being 18 years or older, having given birth at least once, being in the postpartum period (between 2-12 months postpartum). | n=617 (NR) 18 – 39 years |

NR | Induction 38.9% |

Primp 54.3% |

Eutocic 48.3% Inst 4.7% CS 47.0% |

NR | 25.0 |

| Reppen et al., 2023 |

Norway | Women giving birth, 18 years and above and had given birth to a healthy newborn. | n=680 (31.7; 4.6) 18 – 30 years |

Norwegian 77.5% | Induction 25.1% | Primp 51.2% | Eutocic 69.7% Inst 9.4% CS 20.8% |

NR | 9.0 |

| Viirman et al., 2023 |

Sweden | Women aged 18 years or older, who gave birth to a live infant, and rated overall childbirth experience. | n=2953 (31.1; 4.4) | Swedish 74.6% | Induction 34.5% | Primip 48.7% | Eutocic 83.5% Inst 6.5% CS 9.4% |

NR | 6.3 |

| Schönborn et al., 2024 |

Belgium | Women at least 16 years old; having given birth within the last two weeks; speaking French, Dutch, Arabic, Riff, Peul, English,or Spanish, regardless of health insurance, legal status, or literacy. | N=877 (NR) 25 – 36 years |

Belgium 48.8% | NR | Primip 36.3% | Eutocic 79.4% Inst 0% CS 20.6% |

NR | 14.5 |

| Author | Country | Inclusion criteria | Sample (m_age; sd) Range age Groups |

Nationality Race or Ethnicity |

Labor* |

Parity | Mode of birth | Birth Plan | Non-Positive Birth Experience (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favilli et al., 2018 |

Italy |

Women aged > 18 years, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I or II, and single gestation at term. | n=261 (31.9; 5.2) Epidural analgesia n=100 No epidural n=161 |

White 89.0% | Induction 39.8% | Primip 64.8% | Eutocic 87% Inst 8.8% CS 3.8% |

NR | NR |

| Fenaroli et al., 2019 |

Italy | Nulliparous, aged >18 years, fluent in Italian, with a singleton pregnancy, and a planned normal vaginal birth. | n=111 (32.3; 5.2) 19 – 46 years |

NR | Induction 42.2% | Primip 100% | Eutocic 66.4% Inst 14.2% CS 19.4% |

NR | NR |

| Alexandroia et al. ,2019 |

Romania |

Primiparous patients, interviewed after at least 6 weeks of postpartum, delivery by vaginal method or CS, and patients with live newborns. | n=78 (27.5; 5.2) |

NR | NR | Primip 100% | Eutocic NR Inst NR CS NR |

NR | NR |

| Adler et al.,2020 |

Finland |

Women with live singleton pregnancies in cephalic presentation at or beyond 37 gestational weeks with the aim of vaginal delivery. | n=18396 (31.8; 5) |

NR | Induction 28.9% | Primp 47.0% | Eutocic 78.7% Inst 11.9% CS 9.4% |

NR | 4.5 |

| Bouvet et al., 2020 |

France |

Women who consent to participate, without elective cesarean delivery, or emergency cesarean delivery not in labor or intrauterine fetal death, therapeutic abortion. | n=193 (30; NR) 26 – 34 years Oral intake (n=119) No oral intake (n=74) |

NR | Induction 59.0% | Primp 49.0% | Eutocic 94.0% Inst 16.0% CS 6.0% |

NR | NR |

| Arthuis et al., 2022 |

France |

All adult women who understood French and gave birth. | n=2135 (39.8; NR) 19 – 45 years |

NR | Induction 24.6% | Primip 44.2% | Eutocic 85.6% Inst 17.1% CS 14.3% |

Total 36.7% | 7.3 |

| Lyngbye et al., 2022 |

Denmark | Women giving birth to a singleton liveborn child, gestational age 37 to 41. | n= 237 (29.3; 4,3) Nullipara n= 107 Multipara n=130 |

NR | Induction 51.9% | Primip 45.1% | Eutocic 85.3% Inst 6.3% CS 8.4% |

NR | 52.0 |

| Leavy et al., 2023 |

France | Women were included if aged 18 years old or more, spoke French and had given birth to viable and a live-born child | n=123 |

French 95.9% | Induction 16.6% | Primp 45.5% | Eutocic 73.2% Inst 10.6% CS 16.2% |

NR | 10.6 |

| Author | Country | Inclusion criteria | Sample (m_age; sd) Range age Groups |

Nationality Race or Ethnicity |

Labor* |

Parity | Mode of birth | Birth Plan | Non-Positive Birth Experience (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rönnerhag et al., 2018 |

Sweden |

Women who had given birth in previous 12 months and received care at a labor Ward shortly before and after the birth, speaking Swedish. | n=16 (NR) 23 – 46 years |

NR | NR | Primip 37.5% | Eutocic 81.2% Inst 6.3% CS 12.6% |

NR | NR |

| Bringedal & Aune, 2019 |

Norway | Healthy women, given birth for the first time between pregnancy weeks 37-42, with healthy child, speak Norwegian and had a partner, with vaginal and non-instrumental birth but could have had an epidural or been induced. | n=10 (NR) 24 – 31 years |

NR | Induction 20.0% | Primip 100% | Eutocic 100% Inst 0% CS 0% |

NR | NR |

| Pereda-Goikoetxea et al., 2019 |

Spain |

Comprehension of the Spanish and/or Basque language, delivery of a live newborn, pregnancy of 37 weeks or longer, cephalic presentation, 18 years of age or older, written informed consent. | n=43 (34.6; NR) 25 – 43 years |

NR | NR | Primip 60.4% | Eutoc 65.1% Inst 23.1% CS 11.6% |

NR | NR |

| Prosen, M., 2019 |

Slovenia | Women who had given birth in an institutional setting | n=18 (29.3; NR) 20 – 39 years |

NR | NR | Primip 44.4% | Eutoc 55.5% Inst 0% CS 44.5 % |

NR | NR |

| Daniels, S., 2020 |

Sweden | Women who had experienced childbirth during the last 3-20 months. | n=13 (NR) 24 – 37 years |

NR | Induction 23.0% |

Primip 38.0% |

Eutoc 84.6% Inst 0% CS 15.0% |

NR | NR |

| Wiklund et al., 2020 |

Sweden | Swedish-speaking parents that had given birth to a healthy child and who declared that they had experienced bedside reporting during labour. |

n=12 couples (35; 9) |

NR | NR | Primip 75.0% |

Eutoc 91.6% Inst 8.4% CS 0% |

Total 100% | NR |

| López-Toribio et al. 2021 | Spain | Women aged 18 years or older who had given birth at HCB in the previous 12 months. |

n=23 20 – 46 years |

Spanish 78.0% | Induction 61.0% | Primip 100% | Eutoc 78.0% Inst 9.0 % CS 13.0% |

Total 100% | NR |

| Schantz et al., 2021 |

France |

All women interviewed after delivery had given birth by CS. | 284 (31.5; NR) 27 – 36 years |

French 67.3% | NR | Primip 62.3% |

Eutoc 83.3% Inst 0 % CS 16.8% |

NR | 13.8 |

| Alba- Rodríguez et al., 2022 |

Spain |

Mothers who wished to collaborate and were willing to share their experiences and feelings being selected. | n=7 (NR) | NR | NR | NR | NR | Total 5.0% | NR |

| Author | Country | Inclusion criteria | Sample (m_age; sd) Range age Groups |

Nationality Race or Ethnicity |

Labor* |

Parity | Mode of birth | Birth Plan | Non-Positive Birth Experience (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esteban-Sepúlveda et al., 2022 |

Spain |

Women being 18years or older and to communicate in Spanish or Catalan. | n= 15 (32.5; 7.9) 19 – 40 years |

NR | NR | Primip 62.5% | Eutoc 87.5% Inst 0 % CS 12.5% |

NR | NR |

| Huschke, 2022 |

Ireland | Women pregnant or had given birth in Ireland in the last 12 months | n=23 (NR) 20 – 47 years |

Irish 60.9% | NR | Primip 56.5% | NR | NR | NR |

| Eri et al., 2023 |

Norway | Primiparous respondents who had given birth in Norway in a specialized obstetric unit. | n=677 (29; NR) | NR | NR | Primip 100% | NR | NR | NR |

| Pereda-Goikoetxea et al., 2023 |

Spain | Women being18 years or older, live newborn, cephalic presentation, pregnancy 37 weeks or longer, speaking Spanish or Basque. | n=43 (34.6; 3.6) 25 – 43 years |

NR | Induction 44.2% | Primip 60.5% | Eutoc 65.1% Inst 23.3 % CS 11.6% |

NR | NR |

| Širvinskienė et al., 2023 |

Lithuania | Lithuania as the country of residence, given birth within the last 5 years in Lithuania. | n=373 (31.9; 4.7) | NR | NR | Primip 45.0% | NR | NR | NR |

| Pereda-Goikoetxea et al., 2024 |

Spain | Women being18 years or older, live newborn, cephalic presentation, pregnancy 37 weeks or longer, speaking Spanish or Basque. | n=42 (34.6; 3.4) | NR | Induction 42.8% | Primip 59.5% | Eutoc 64.3% Inst 23.8 % CS 11.9% |

NR | NR |

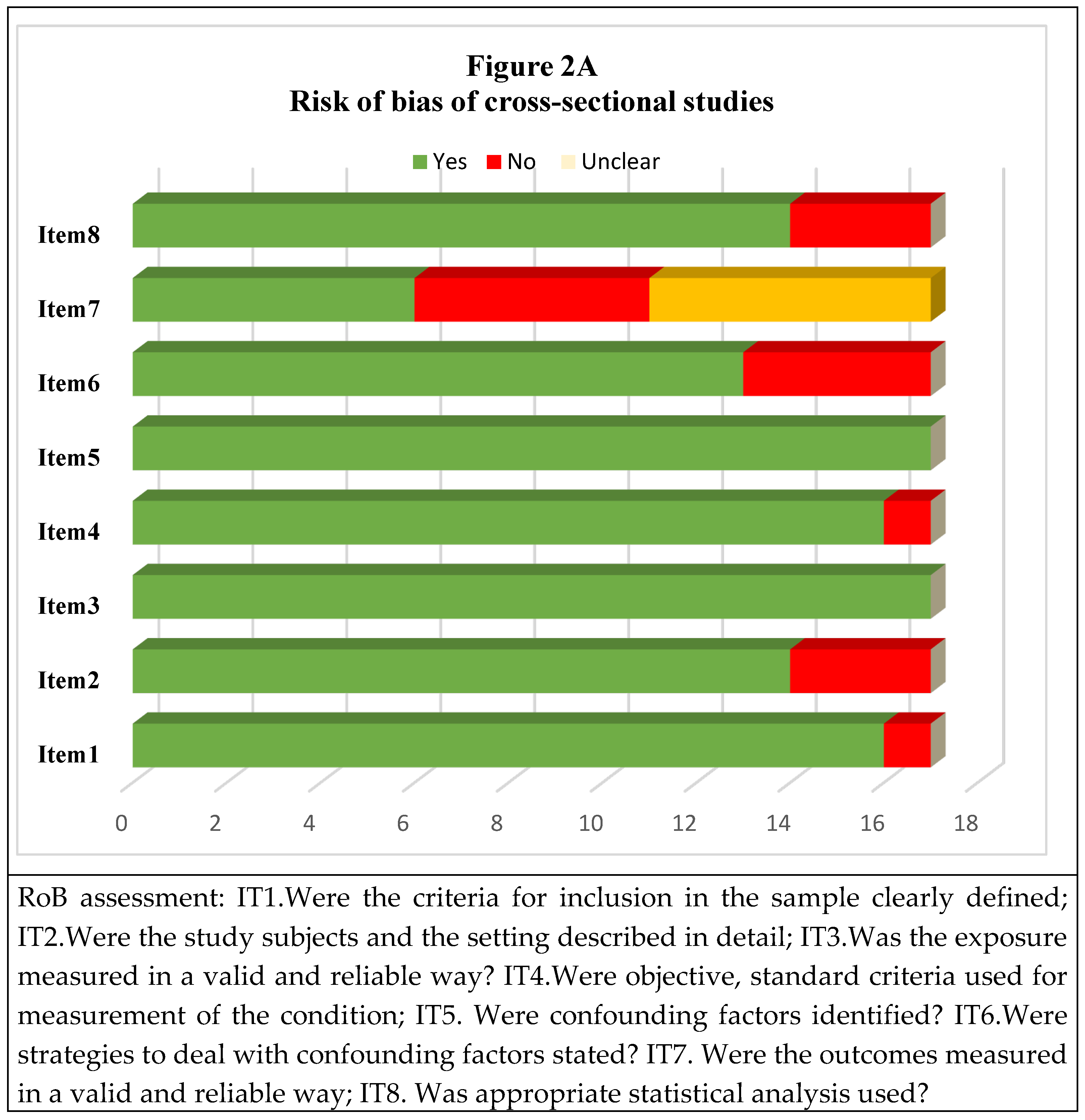

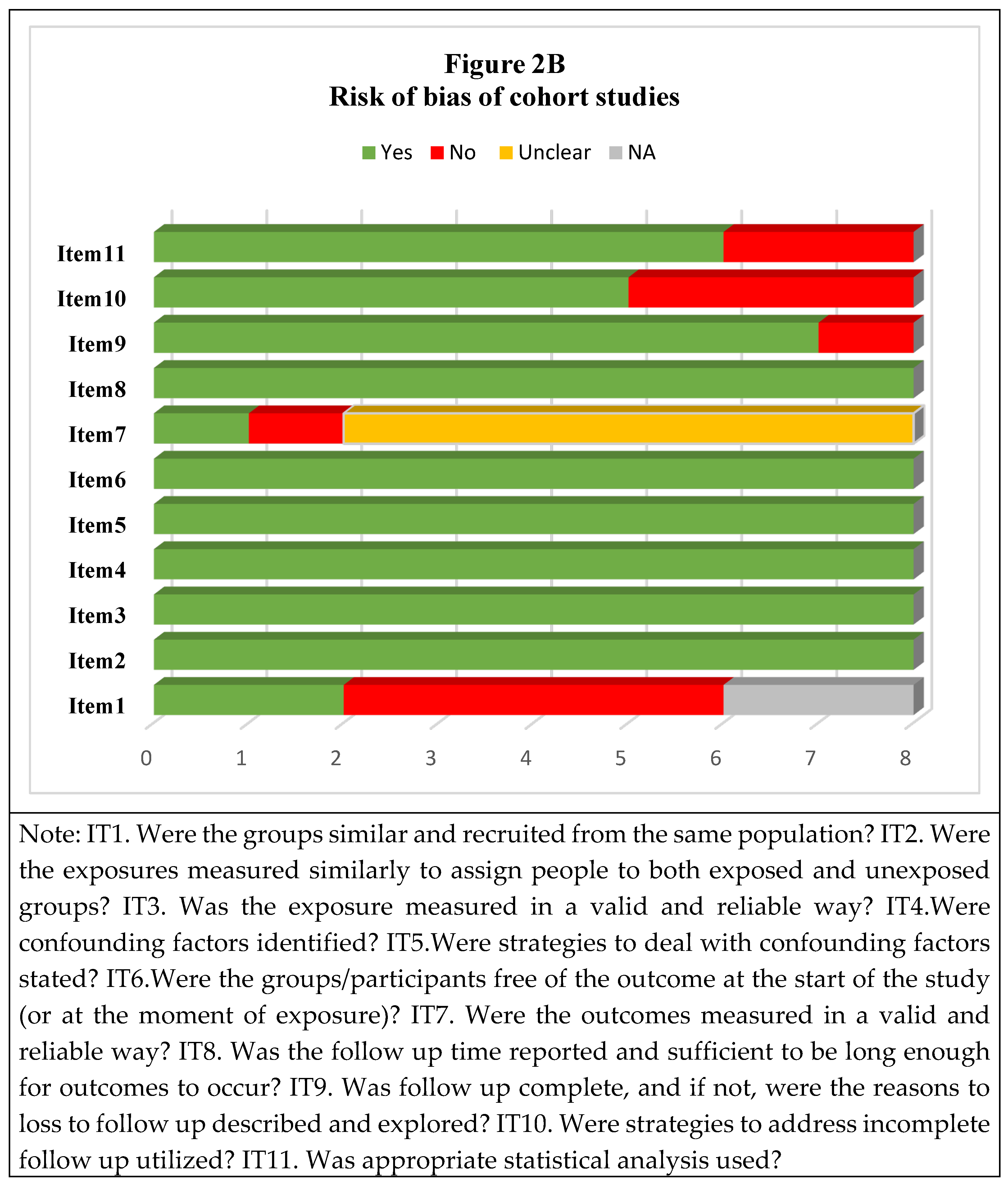

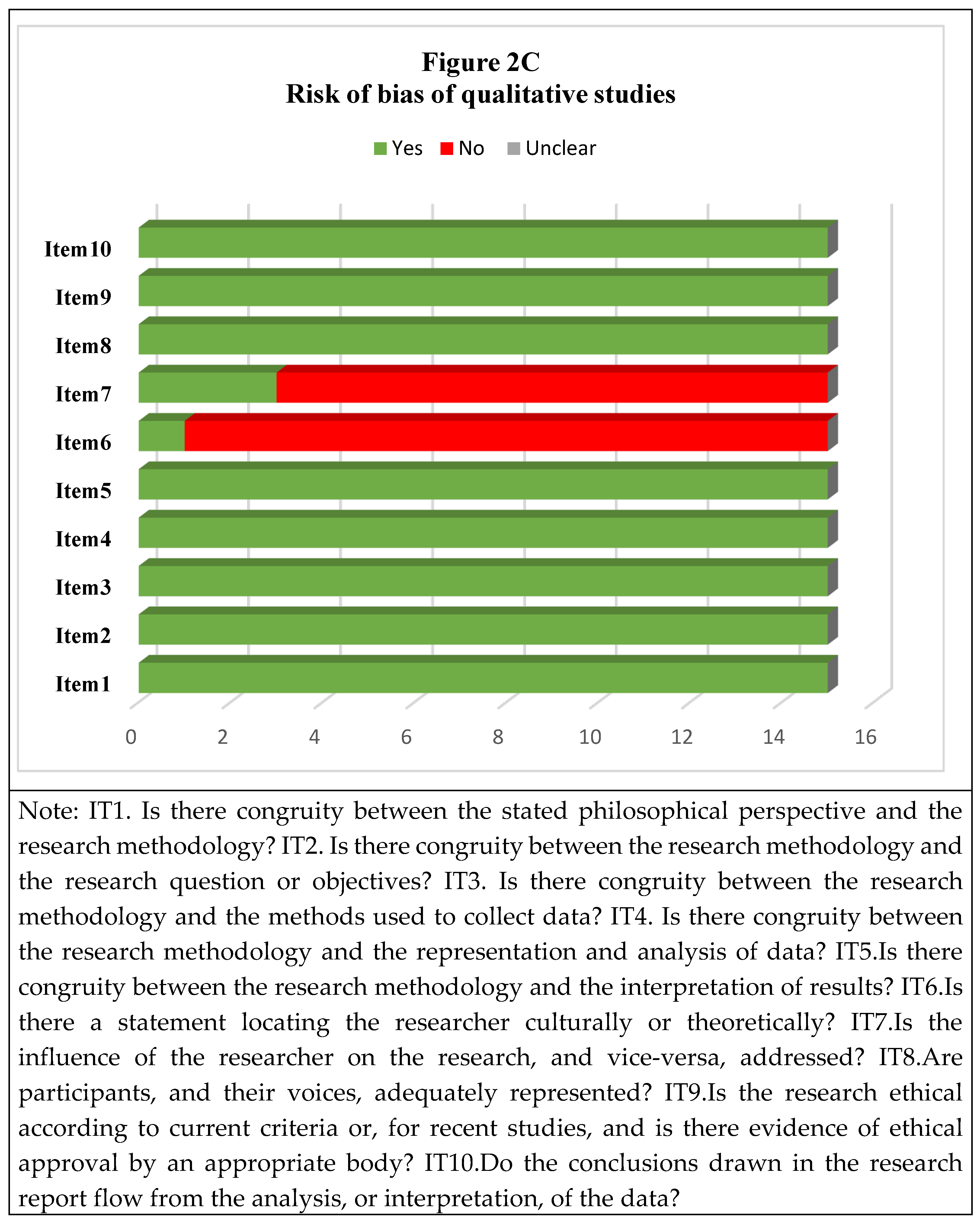

Risk of Bias

Women’s Experiences

Disrespectful Care During Childbirth in Health Facilities (DACF)

| Author Country |

Sample | Childbirth practices* |

Disrespectful/abusive care during childbirth in health facilities (DACF) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical abuse |

Non-confidential care |

Discriminatory care |

Detention in facility |

Non-consented care |

Non-dignified care |

Abandonment of care |

|||

| Basso, MA, 2016 | General | 90.2% Vaginal palpations 73.5% Trichotomy 70.5% Enema 55.6% Amniotomy 68.5% Episiotomy 35.0% Kristeller 31.6% Induction |

2.7% physical abuse | 38.5% No respect 17.4% Feel offended |

76.6% of Episiotomy 83.6% of Kristeller 42.6% of Induction 28.8% of Amniotomy 15.6% of Trichotomy 8.7 % of Enema |

||||

| Baranowska et al., 2019 Poland |

General | 48.1% Baby bath 46.1% Presence students 43.2% Bottle feeding baby 40.8% Intravenous canula 36.6% Baby drug administration 32.9% Vaginal examinations 30.5% Episiotomy 29.1% Oxytocin 27.3% Baby examination 27.1% Induction 17.4% Shaving vulva 12.4% Baby vaccination 4.3% Enema |

0.5% Being poked | 19.3% No respect for intimacy |

16.3% Not respect 14.2% Rude manners 8.8% Feeling of being discriminated/stigmatized |

2.8% Forced legs apart when pushing 0.8% Legs tied to delivery bed |

48.1% Baby bath 46.1% Presence students 43.2% Bottle feeding baby 40.8% Intravenous canula 36.6% Baby drug administration 35.3% Provider did not explain procedures/updates 32.9% Vaginal examination 30.5% Episiotomy 29.1% Oxytocin 27.3% Baby examination 27.1% Induction 17.4% Shaving vulva 12.4% Baby vaccination 4.3% Enema |

24.4% Inappropriate comments 20.3% Nonchalant treatment 17.1% No answering 15.6% Disrespectful expressions 10.1% Mocking 6.8% Insulting 4.9% Blackmailing with child’s/woman’s health |

32.6% No access to lactation consultant 31% Undelicate care 28.8% No support in breastfeeding 16.6% No support in dealing depression 13% No access to epidural anesthesia |

| Mena-Tudela et al., 2020 Spain |

General | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 83.4% No consent for procedures 45.9% Provider did not explain procedures/updates 12.9% No respect BP without giving reasons |

34.5% Critized 31.4% Nicknames |

54.5% Felt insecure 48.0% Difficult to voice doubts, fears, concerns 35.0% No support in postpartum 37.6% No support in breastfeeding 44.4% Unnecessary or painful procedures |

| Author | Sample | Childbirth practices* |

Disrespectful/abusive care during childbirth in facilities (DACF) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical abuse |

Non-confidential care |

Discriminatory care |

Detention in facility |

Non-consented care |

Non-dignified care |

Abandonment of care |

|||

| Mena-Tudela et al., 2021 Spain |

General | 48.3% Oxytocin 39.3% Episiotomy 36.3% Amniorrhexis 34.3% Drink/food restriction 34.2% Kristeller maneuver 32.1% Newborn examination 31.9% Vaginal palpations 23.6% Cupping glass 21.5% Hamilton maneuver 21% Early umbilical clamp 11.2% Removed placenta 9.1% Apply enemas 7.7% Shaving vulva 10.1% Other procedures |

NR | NR | NR | 39.5% Restricted mobility | 42.1% Provider did not explain procedures/updates 13.6% Bottle feeding baby |

NR | 36.9% Separated baby without reason 27.9% Not allowed accompanied |

| Oelhafen et al., 2021 Switzerland |

General | 24.8% Amniotomy 20% Induction 12.6% Episiotomy 6.8% Fundal pressure |

NR | NR | NR | NR | 16.3% of women felt pressure to consent for procedures (episiotomy, induction…) | 9.5% Insulting | 27% Felt intimidated |

| Westergren et al., 2021 Sweden |

General | 63.4% IFM 45.2% Oxytocin 44.5% IUC 41.0% ARM 22.7% Induction 5.2% Episiotomy |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 65.5% Women undergone painful procedures without epidural analgesia |

| Leavy et al., 2023 France |

General | 81.3% Episiotomy | NR | NR | 1.6% Provider used language difficult to understand | NR | 2.4% Not decision-making |

3.3% Inappropriate attitude 0.8% Inappropriate language |

5.7% Not consider pain |

Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

Conclusions

Recommendations for Future Research

Relevance for Clinical Practice

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Disclosure statement

Ethics statement

Protocol registration

References

- Sadler M, Santos MJ, Ruiz-Berdún D, et al. Moving beyond disrespect and abuse: addressing the structural dimensions of obstetric violence. Reprod Health Matters. 2016;24(47):47-55. [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Sepúlveda S, Fabregas-Mitjans M, Ordobas-Pages L, Tutusaus-Arderiu A, Andreica LE, Leyva-Moral JM. The experience of giving birth in a hospital in Spain: Humanization versus technification. Enfermeria Clin Engl Ed. 2022;32 Suppl 1:S14-S22. [CrossRef]

- Miller S, Lalonde A. The global epidemic of abuse and disrespect during childbirth: History, evidence, interventions, and FIGO’s mother-baby friendly birthing facilities initiative. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;131:S49-S52. [CrossRef]

- OHCHR. Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Preventable Maternal Mortality and Morbidity and Human Rights. United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights; 2010:1-31. http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/14session/A.HRC.14.39_AEV-2.pdf.

- OHCHR. Technical Guidance on the Application of a Human Rights- Based Approach to the Implementation of Policies and Programmes to Reduce Preventable Maternal Morbidity and Mortality: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights; 2012:20. https://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/women/docs/A.HRC.21.22_en.pdf.

- da Silva MG, Marcelino MC, Rodrigues LSP, Toro RC, Shimo AKK. Obstetric violence according to obstetric nurses. Rev Rede Enferm Nordeste. 2014;15(4):720-728. [CrossRef]

- Vogels-Broeke M, Cellissen E, Daemers D, Budé L, de Vries R, Nieuwenhuijze M. Women’s decision-making autonomy in Dutch maternity care. Birth Berkeley Calif. 2023;50(2):384-395. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience. World Health Organization; 2018. Accessed March 4, 2024. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/260178.

- Mena-Tudela D, Cervera-Gasch A, Alemany-Anchel MJ, Andreu-Pejó L, González-Chordá VM. Design and Validation of the PercOV-S Questionnaire for Measuring Perceived Obstetric Violence in Nursing, Midwifery and Medical Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):8022. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire NP, Joshi SK, Dahal P, Swahnberg K. Women’s experience of disrespect and abuse during institutional delivery in biratnagar, Nepal. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18). [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. A human rights-based approach to mistreatment and violence against women in reproductive health services with a focus on childbirth and obstetric violence. Off Secr Gen. 2019;11859(July):23.

- Reed R, Sharman R, Inglis C. Women’s descriptions of childbirth trauma relating to care provider actions and interactions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):21. [CrossRef]

- Ayers S, Bond R, Bertullies S, Wijma K. The aetiology of post-traumatic stress following childbirth: a meta-analysis and theoretical framework. Psychol Med. 2016;46(6):1121-1134. [CrossRef]

- Tunçalp Ӧ., Were W, MacLennan C, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns—the WHO vision. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;122(8):1045-1049. [CrossRef]

- Downe S, Finlayson K, Oladapo O, Bonet M, Gülmezoglu AM. What matters to women during childbirth: A systematic qualitative review. Norhayati MN, ed. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0194906. [CrossRef]

- Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):77. [CrossRef]

- Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, et al. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. The Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1129-1145. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372. [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):39. [CrossRef]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. Published online 1960:37-46.

- do Nascimento A, Gabriela dos M, Andréia Pereira Soares dos F, et al. Expresiones de violencia institucionalizada en el parto: una revisión integradora. Enferm Glob. 2016;44:478-489.

- Garcia LM. A concept analysis of obstetric violence in the United States of America. Nurs Forum (Auckl). 2020;55(4):654-663. [CrossRef]

- Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Checklist for Cohort Studies. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer´s Manual. 2017.

- Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porrit L. Checklist for qualitative research. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179-187.

- Baptie G, Andrade J, Bacon AM, Norman A. Birth trauma: the mediating effects of perceived support. Br J Midwifery. 2020;28(10):724-730. [CrossRef]

- Ryan G, O Doherty KC, Devane D, McAuliffe F, Morrison J. Questionnaire survey on women’s views after a first caesarean delivery in two tertiary centres in Ireland and their preference for involvement in a future randomised trial on mode of birth. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e031766. [CrossRef]

- Bringedal H, Aune I. Able to choose? Women’s thoughts and experiences regarding informed choices during birth. Midwifery. 2019;77:123-129. [CrossRef]

- Alba-Rodríguez R, Coronado-Carvajal MP, Hidalgo-Lopezosa P. The Birth Plan Experience—A Pilot Qualitative Study in Southern Spain. Healthcare. 2022;10(1):95. [CrossRef]

- Eri TS, Røysum IG, Meyer FB, et al. Important aspects of intrapartum care described by first-time mothers giving birth in specialised obstetric units in Norway: A qualitative analysis of two questions from the Babies Born Better study. Midwifery. 2023;123:103710. [CrossRef]

- Huschke S. ‘The System is Not Set up for the Benefit of Women’: Women’s Experiences of Decision-Making During Pregnancy and Birth in Ireland. Qual Health Res. 2022;32(2):330-344.

- Mena-Tudela D, Iglesias-Casás S, González-Chordá VM, Cervera-Gasch Á, Andreu-Pejó L, Valero-Chilleron MJ. Obstetric Violence in Spain (Part I): Women’s Perception and Interterritorial Differences. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7726. [CrossRef]

- Širvinskienė G, Grincevičienė Š, Pranskevičiūtė-Amoson R, Kukulskienė M, Downe S. ‘To be informed and involved’: Women’s insights on optimising childbirth care in Lithuania. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy. 2023;26(4):1514-1523. [CrossRef]

- Baranowska B, Doroszewska A, Kubicka-Kraszyńska U, et al. Is there respectful maternity care in Poland? Women’s views about care during labor and birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):520. [CrossRef]

- Mena-Tudela D, Iglesias-Casás S, González-Chordá VM, Cervera-Gasch Á, Andreu-Pejó L, Valero-Chilleron MJ. Obstetric violence in Spain (Part II): Interventionism and medicalization during birth. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(1):1-14. [CrossRef]

- Basso AM. A Outra Dor do Parto: Género, Relações de Poder e Violência Obstétrica na Assistência Hospitalar ao Parto. M.A. Universidade NOVA de Lisboa (Portugal); 2016. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/outra-dor-do-parto-género-relações-de-poder-e/docview/3039368165/se-2?accountid=15292.

- González-de la Torre H, Miñarro-Jiménez S, Palma-Arjona I, Jeppesen-Gutierrez J, Berenguer-Pérez M, Verdú-Soriano J. Perceived satisfaction of women during labour at the Hospital Universitario Materno-Infantil of the Canary Islands through the Childbirth Experience Questionnaire (CEQ-E). Enfermeria Clin Engl Ed. 2021;31(1):21-30. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez P, Casañas R, Collado Palomares A, et al. Women’s childbirth satisfaction and obstetric outcomes comparison between two birth hospitals in Barcelona with different level of assistance and complexity. Cent Eur J Nurs Midwifery. 2021;12(1):235-244. [CrossRef]

- Viirman F, Hesselman S, Poromaa IS, Svanberg AS, Wikman A. Overall childbirth experience: what does it mean? A comparison between an overall childbirth experience rating and the Childbirth Experience Questionnaire 2. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):176. [CrossRef]

- Carquillat P, Boulvain M, Guittier MJ. How does delivery method influence factors that contribute to women’s childbirth experiences? Midwifery. 2016;43:21-28. [CrossRef]

- Chabbert M, Rozenberg P, Wendland J. Predictors of Negative Childbirth Experiences Among French Women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs JOGNN. 2021;50(4):450-463. [CrossRef]

- Deherder E, Delbaere I, Macedo A, Nieuwenhuijze MJ, Van Laere S, Beeckman K. Women’s view on shared decision making and autonomy in childbirth: cohort study of Belgian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):551. [CrossRef]

- Perdok H, Verhoeven CJ, van Dillen J, et al. Continuity of care is an important and distinct aspect of childbirth experience: findings of a survey evaluating experienced continuity of care, experienced quality of care and women’s perception of labor. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):13. [CrossRef]

- Oelhafen S, Trachsel M, Monteverde S, Raio L, Cignacco E. Informal coercion during childbirth: risk factors and prevalence estimates from a nationwide survey of women in Switzerland. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):369. [CrossRef]

- Adler K, Rahkonen L, Kruit H. Maternal childbirth experience in induced and spontaneous labour measured in a visual analog scale and the factors influencing it; a two-year cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):415. [CrossRef]

- Bouvet L, Garrigue J, Desgranges FP, Piana F, Lamblin G, Chassard D. Women’s view on fasting during labor in a tertiary care obstetric unit. A prospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;253:25-30. [CrossRef]

- Favilli A, Laganà AS, Indraccolo U, et al. What women want? Results from a prospective multicenter study on women’s preference about pain management during labour. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;228:197-202. [CrossRef]

- Arthuis C, LeGoff J, Olivier M, et al. The experience of giving birth: a prospective cohort in a French perinatal network. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):439. [CrossRef]

- Fenaroli V, Molgora S, Dodaro S, et al. The childbirth experience: obstetric and psychological predictors in Italian primiparous women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):419. [CrossRef]

- Lyngbye K, Melgaard D, Lindblad V, et al. Do women’s perceptions of their childbirth experiences change over time? A six-week follow-up study in a Danish population. Midwifery. 2022;113:N.PAG-N.PAG. [CrossRef]

- Alexandroaia C, Sima RM, Balalau OD, Olaru GO, Ples L. Patients’ perception of childbirth according to the delivery method: The experience in our clinic. J Mind Med Sci. 2019;6(2):311-318. [CrossRef]

- Schantz C, Pantelias AC, de Loenzien M, et al. “A caesarean section is like you’ve never delivered a baby”: A mixed methods study of the experience of childbirth among French women. Reprod Biomed Soc Online. 2021;12:69-78. [CrossRef]

- López-Toribio M, Bravo P, Llupià A. Exploring women’s experiences of participation in shared decision-making during childbirth: a qualitative study at a reference hospital in Spain. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):631. [CrossRef]

- Mena-Tudela D, Iglesias-Casás S, González-Chordá VM, Cervera-Gasch Á, Andreu-Pejó L, Valero-Chilleron MJ. Obstetric Violence in Spain (Part II): Interventionism and Medicalization during Birth. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18(1):199. [CrossRef]

- Reppen K, Henriksen L, Schei B, Magnussen EB, Infanti JJ. Experiences of childbirth care among immigrant and non-immigrant women: a cross-sectional questionnaire study from a hospital in Norway. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):1-12. [CrossRef]

- Westergren A, Edin K, Lindkvist M, Christianson M. Exploring the medicalisation of childbirth through women’s preferences for and use of pain relief. Women Birth J Aust Coll Midwives. 2021;34(2):e118-e127. [CrossRef]

- Wiklund I, Sahar Z, Papadopolou M, Löfgren M. Parental experience of bedside handover during childbirth: A qualitative interview study. Sex Reprod Healthc Off J Swed Assoc Midwives. 2020;24:100496. [CrossRef]

- Leavy E, Cortet M, Huissoud C, et al. Disrespect during childbirth and postpartum mental health: a French cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):241. [CrossRef]

- Betran A, Torloni M, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu A, the WHO Working Group on Caesarean Section. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;123(5):667-670. [CrossRef]

- European Parlamient. Obstetric and gynaecological violence in the EU - Prevalence, legal frameworks and educational guidelines for prevention and elimination. Published online 2024. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2024/761478/IPOL_STU(2024)761478_EN.pdf.

- Rodríguez J, Martínez A. La violencia obstétrica: una práctica invisibilizada en la atención médica en España. Gac Sanit. 2021;35(3):211-212. [CrossRef]

- Mena-Tudela D, Iglesias-Casás S, González-Chordá VM, Valero-Chillerón MJ, Andreu-Pejó L, Cervera-Gasch Á. Obstetric violence in Spain (Part III): Healthcare professionals, times and areas. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7). [CrossRef]

- Coulter A, Oldham J. Person-centred care: what is it and how do we get there? Future Hosp J. 2016;3(2):114-116. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Implementation Guidance: Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services: The Revised Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. World Health Organization; 2018. Accessed March 4, 2024. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/272943.

- Aktaş S, Küçük Alemdar D. Why mothers with midwifery-led vaginal births recommend that mode of birth: a qualitative study. J Reprod Infant Psychol. Published online March 11, 2024:1-22. [CrossRef]

- Werdofa HM, Thoresen L, Lulseged B, Lindahl AK. ‘I believe respect means providing necessary treatment on time’ - a qualitative study of health care providers’ perspectives on disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):257. [CrossRef]

- Mena-Tudela D, Roman P, González-Chordá VM, Rodriguez-Arrastia M, Gutiérrez-Cascajares L, Ropero-Padilla C. Experiences with obstetric violence among healthcare professionals and students in Spain: A constructivist grounded theory study. Women Birth. 2023;36(2):e219-e226. [CrossRef]

- Sheferaw ED, Mengesha TZ, Wase SB. Development of a tool to measure women’s perception of respectful maternity care in public health facilities. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):67. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).