Submitted:

14 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Maternity rights are perceived and fulfilled differently according to women’s psychosocial characteristics, leading to varying maternal experiences and outcomes. It is necessary to know the impact of cultural context, emotional well-being, and resource availability on the maternal woman's clinical care experience. The aim is to identify if these factors contribute to disparities in the perception of maternity rights fulfillment in Spain and Colombia. This was a retrospective observational study focus on women who received healthcare during maternity in Spain or Colombia. A total of 185 women were selected (Spanish=53; Colombian=132). It was recorded social and obstetric history, and resilience, positive and negative affect, derailment, and maternity beliefs. It also evaluated the women's knowledge of healthcare rights (MatCODE), the perception of resource scarcity (MatER), and the fulfillment of maternity rights (FMR). The C-section was significantly more prevalent in Colombia and had higher score in maternity beliefs as a sense of life and as a social duty than Spanish women. The FMR was higher in Spanish context. Women in Colombia perceived lower social support and participation in medical treatment. The FMR was correlated with positive affect, MatCODE, and MatER. The FMR models detected negative factors such as giving birth in Colombia (β=-0.30 [-0.58; -0.03]), previous miscarriages (β=-0.32 [-0.54; -0.09]), exposure to a C-section in the last labor (β=-0.46 [-0.54; -0.0]) and the MatER, and positive factors such as gestational age, women age and previous C-section (β=0.39 [0.11; 0.66]). The perception of the fulfillment of maternity rights depends on socio-healthcare contexts, women age, obstetric history, and resources. It is suggested to apply culturally sensitive strategies focused on women's needs in terms of information, emotional and social support, privacy and autonomy to manage a positive experience.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Setting Social-Health Context

2.3. Participants of the Study

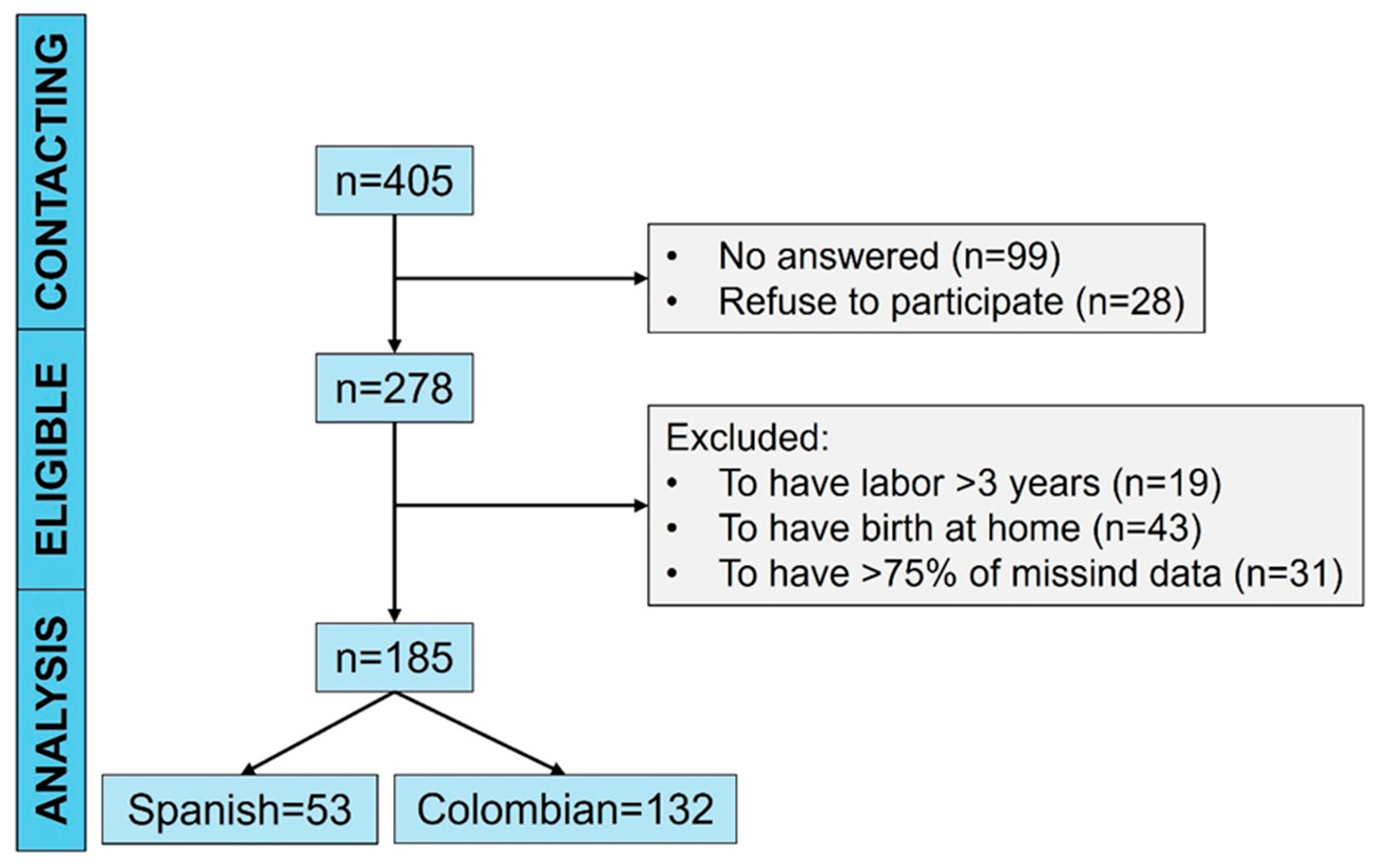

2.4. Study Design and Procedure

2.4.1. Psychological Instruments to Explore Emotional Variables

2.4.2. Perception Scales to Explore Maternity Rights and Resources

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Social and Obstetrical Characteristics

3.2. Emotional Variables During the Last Pregnancy and Postpartum

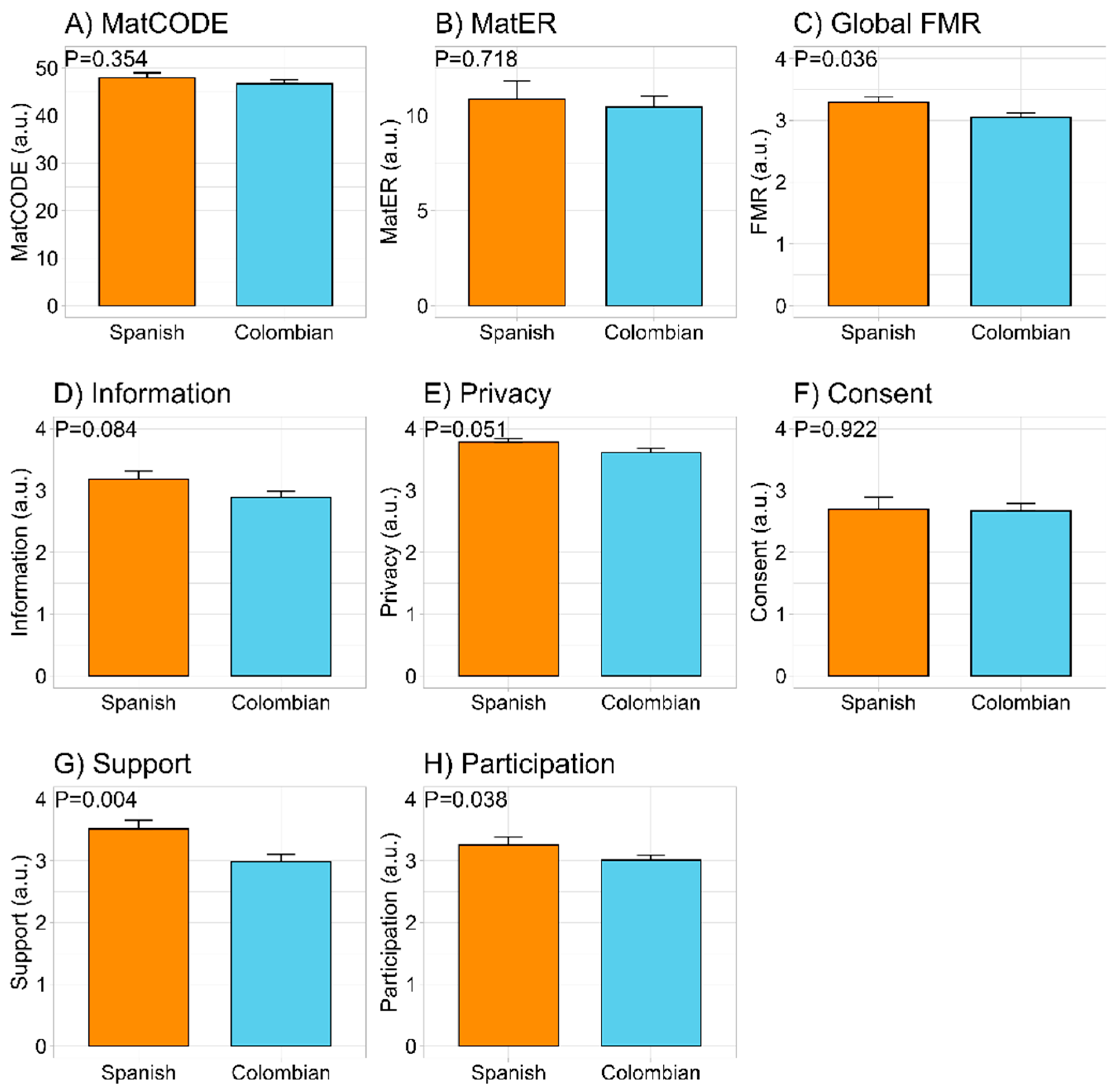

3.3. Perception of Maternity Rights and Resources During the Last Pregnancy, Childbirth and Postpartum

3.4. Correlations Between Perception of Maternity Rights and Emotional Variables

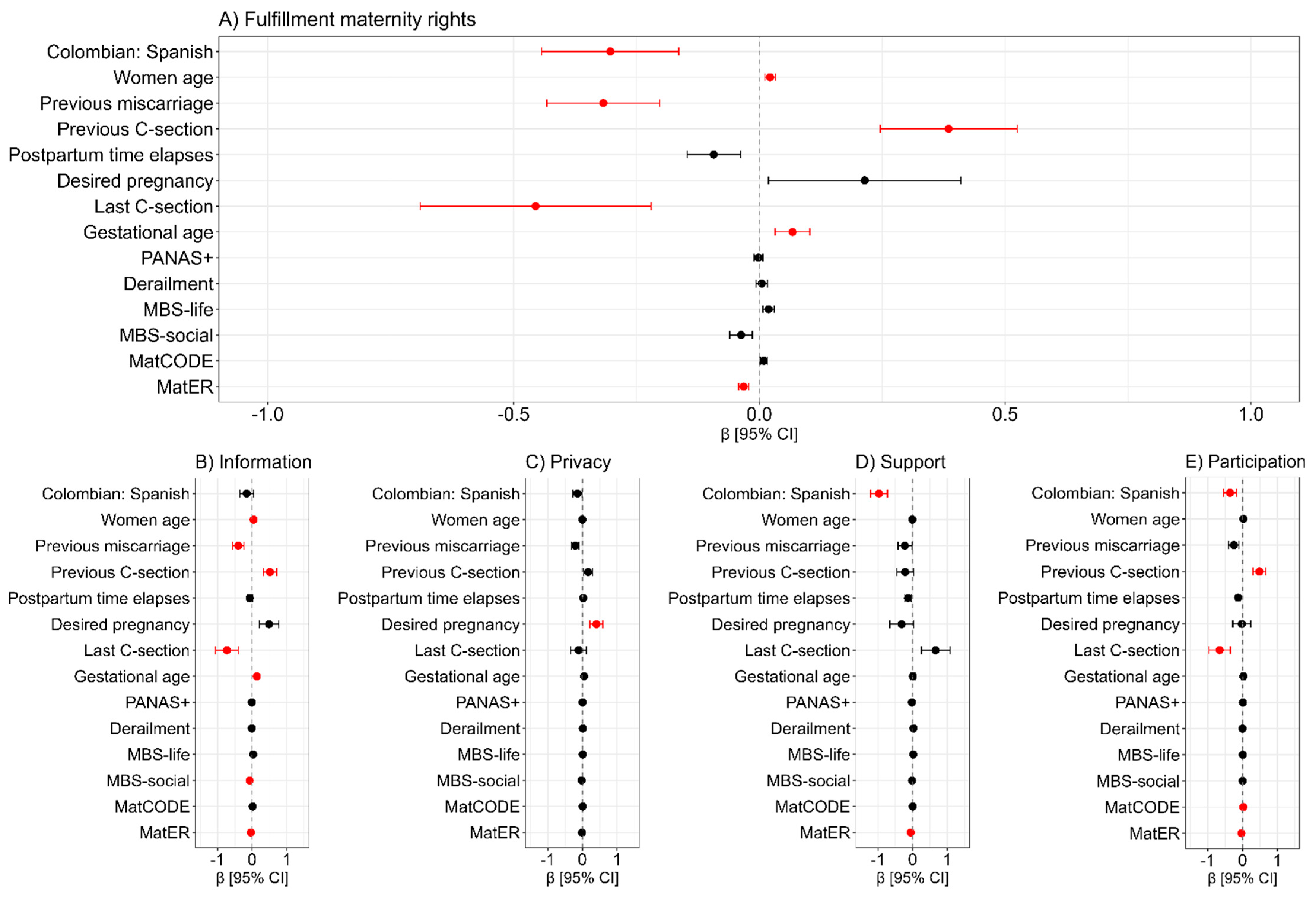

3.5. Women-Centered Model to Explain Their Perception of Fulfillment of Maternity Rights

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) One in 5 Women Reported Mistreatment While Receiving Maternity Care. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2023/s0822-vs-maternity-mistreatment.html#print (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Mena-Tudela, D.; Iglesias-Casás, S.; González-Chordá, V.M.; Cervera-Gasch, Á.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; Valero-Chilleron, M.J. Obstetric Violence in Spain (Part I): Women’s Perception and Interterritorial Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jojoa-Tobar, E.; Cuchumbe-Sánchez, Y.D.; Ledesma-Rengifo, J.B.; Muñoz-Mosquera, M.C.; Suarez-Bravo, J.P. Violencia Obstétrica: Haciendo Visible Lo Invisible. Rev. Univ. Ind. Santander Salud 2019, 51, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandall, J.; Soltani, H.; Gates, S.; Shennan, A.; Devane, D. Midwife-Led Continuity Models versus Other Models of Care for Childbearing Women. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Sandall, J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Arribas, A.; Escuriet, R.; Borràs-Santos, A.; Vila-Candel, R.; González-Blázquez, C. A Comparison between Midwifery and Obstetric Care at Birth in Spain: Across-Sectional Study of Perinatal Outcomes. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 126, 104129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhinaraset, M.; Giessler, K.; Nakphong, M.K.; Roy, K.P.; Sahu, A.B.; Sharma, K.; Montagu, D.; Green, C. Can Changes to Improve Person-Centred Maternity Care Be Spread across Public Health Facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India? Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2021, 29, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, J.-F.; Harris, M.F.; Russell, G. Patient-Centred Access to Health Care: Conceptualising Access at the Interface of Health Systems and Populations. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grand-Guillaume-Perrenoud, J.A.; Origlia, P.; Cignacco, E. Barriers and Facilitators of Maternal Healthcare Utilisation in the Perinatal Period among Women with Social Disadvantage: A Theory-Guided Systematic Review. Midwifery 2022, 105, 103237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blount, A.J.; Adams, C.R.; Anderson-Berry, A.L.; Hanson, C.; Schneider, K.; Pendyala, G. Biopsychosocial Factors during the Perinatal Period: Risks, Preventative Factors, and Implications for Healthcare Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumas, N.; Godoy, A.C.; Peresini, V.; Peisino, M.E.; Boldrini, G.; Vaggione, G.; Acevedo, G.E. El Cuidado Prenatal y Los Determinantes Sociales: Estudio Ecológico En Argentina. Poblac. Salud Mesoam. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Guide for Integration of Perinatal Mental Health in Maternal and Child Health Services. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240057142 (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Contreras-Carreto, N.A.; Moreno-Sánchez, P.; Márquez-Sánchez, E.; Vázquez-Solares, V.; Pichardo-Cuevas, M.; Ramírez-Montiel, M.L.; Segovia-Nova, S.; González-Yóguez, T.A.; Mancilla-Ramírez, J. Salud Mental Perinatal y Recomendaciones Para Su Atención Integral En Hospitales Ginecoobstétricos. Cir. Cir. 2022, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S.; Cignacco, E.; Monteverde, S.; Trachsel, M.; Raio, L.; Oelhafen, S. ‘We Felt like Part of a Production System’: A Qualitative Study on Women’s Experiences of Mistreatment during Childbirth in Switzerland. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Fernandez, C.S.; de la Calle, M.; Arribas, S.M.; Garrosa, E.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Factors Associated with Obstetric Violence Implicated in the Development of Postpartum Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 1553–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, I.A.; Silva, C.M.; Costa, E.M.; Ferreira, M. de J.; Abuchaim, E. de S.V. Continued Breastfeeding and Work: Scenario of Maternal Persistence and Resilience. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2023, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paricio del Castillo, R.; Polo Usaola, C. Maternity and Maternal Identity: Therapeutic Deconstruction of Narratives. Rev. Asoc. Esp. Neuropsiq. 2020, 40, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuman, H.L.; Grupp, A.M.; Robb, L.A.; Akers, K.G.; Bedi, G.; Shah, M.A.; Janis, A.; Caldart, C.G.; Gupta, U.; Vaghasia, J.K.; et al. Approaches and Geographical Locations of Respectful Maternity Care Research: A Scoping Review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakibazadeh, E.; Namadian, M.; Bohren, M.; Vogel, J.; Rashidian, A.; Nogueira Pileggi, V.; Madeira, S.; Leathersich, S.; Tunçalp, Ӧ.; Oladapo, O.; et al. Respectful Care during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. BJOG 2018, 125, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.; Lattof, S.R.; Coast, E. Interventions to Provide Culturally-Appropriate Maternity Care Services: Factors Affecting Implementation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elm, E. von; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The World Bank (IBRD-IDA) How Does the World Bank Classify Countries? Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/378834-how-does-the-world-bank-classify-countries (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Guerrero, R.; Gallego, A.I.; Becerril-Montekio, V.; Vásquez, J. The Health System of Colombia. Salud Publica Mex. 2011, 53, SI144–SI155. [Google Scholar]

- oletín Oficial del Estado (BOE) Ley 41/2002, de 14 de Noviembre, Básica Reguladora de La Autonomía Del Paciente y de Derechos y Obligaciones En Materia de Información y Documentación Clínica.; Gobierno de España. 2003.

- Ministry of Health and Consumers´ Affaires Strategy for Assistance at Normal Childbirth in the National Health System; 1st ed. ; Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Gobierno de España: Madrid, 2007.

- Administración de la Fundación Pública Ley 2244 de 2022 Por Medio de La Cual Se Reconocen Los Derechos de La Mujer En Embarazo, Trabajo Departo, Parto y Posparto y Se Dictan Otras Disposiciones o “Ley de Parto Digno, Respetado y Humanizado. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=189347: Colombia, 2022; 1893.

- Gila-Díaz, A.; Carrillo, G.H.; López de Pablo, Á.L.; Arribas, S.M.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Association between Maternal Postpartum Depression, Stress, Optimism, and Breastfeeding Pattern in the First Six Months. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Teruel, D.; Robles-Bello, M.A. 14-Item Resilience Scale (RS-14): Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version. Rev. Iberoam. Diagnóstico Evaluación – Avaliação Psicológica 2015, 2, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wagnild, G.M.; Young, H.M. Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 1993, 1, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Surzykiewicz, J.; Konaszewski, K.; Wagnild, G. Polish Version of the Resilience Scale (RS-14): A Validity and Reliability Study in Three Samples. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilemann, M. V.; Lee, K.; Kury, F.S. Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the Resilience Scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 2003, 11, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Gómez, I.; Hervás, G.; Vázquez, C. Adaptación de Las “Escalas de Afecto Positivo y Negativo” (PANAS) En Una Muestra General Española. Behav. Psychol. 2015, 23, 529–548. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-García, A.; González-Robles, A.; Mor, S.; Mira, A.; Quero, S.; García-Palacios, A.; Baños, R.M.; Botella, C. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Psychometric Properties of the Online Spanish Version in a Clinical Sample with Emotional Disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratner, K.; Burrow, A.L.; Thoemmes, F.; Mendle, J. Invariance of the Derailment Scale-6: Testing the Measurement and Correlates of Derailment across Adulthood. Psychol. Assess. 2022, 34, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishima, Y.; Nagamine, M. Unpredictable Changes: Different Effects of Derailment on Well-Being Between North American and East Asian Samples. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 3457–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrow, A.L.; Hill, P.L.; Ratner, K.; Fuller-Rowell, T.E. Derailment: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Adjustment Correlates of Perceived Change in Self and Direction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 118, 584–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratner, K.; Zhu, G.; Li, Q.; Rice, M.; Estevez, M.; Burrow, A.L. Derailment in Adolescence: Factor Analytic Structure and Correlates. J. Res. Adolesc. 2024, 34, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preis, H.; Benyamini, Y. The Birth Beliefs Scale – a New Measure to Assess Basic Beliefs about Birth. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 38, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, C.; Calleja, N.; Bravo, C.; Meléndez, J. Escala de Creencias Sobre La Maternidad: Construcción y Validación En Mujeres Mexicanas. Rev. Iberoam. De Diagnóstico Y Evaluación – E Avaliação Psicológica 2019, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Fernández, C.S.; de la Calle, M.; Suta, M.A.; Arribas, S.M.; Garrosa, E.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Psychometric Evaluation of Women’s Knowledge of Healthcare Rights and Perception of Resource Scarcity during Maternity. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO); WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience. 1st ed. World Health Organization: Genova, 2018; ISBN 978-92-4-155021-5.

- Silva-Fernández, C.S.; de la Calle, M.; Camacho, P.A.; Arribas, S.M.; Garrosa, E.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Psychometric Reliability to Assess the Perception of Women’s Fulfillment of Maternity Rights. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2248–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Roosmalen, J.; van den Akker, T. Continuous and Caring Support Right Now. BJOG 2016, 123, 675–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, D.M.B.; Modena, C.M. Obstetric Violence in the Daily Routine of Care and Its Characteristics. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2018, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.K.; Gavin, N.I.; Benedict, M.B. Access for Pregnant Women on Medicaid: Variation by Race and Ethnicity. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2005, 16, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedam, S.; Stoll, K.; Taiwo, T.K.; Rubashkin, N.; Cheyney, M.; Strauss, N.; McLemore, M.; Cadena, M.; Nethery, E.; Rushton, E.; et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers Study: Inequity and Mistreatment during Pregnancy and Childbirth in the United States. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlanga Fernández, S.; Vizcaya-Moreno, M.F.; Pérez-Cañaveras, R.M. Percepción de La Transición a La Maternidad: Estudio Fenomenológico En La Provincia de Barcelona. Aten. Primaria 2013, 45, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.E.; Newby, A. Family Support and Pregnancy Behavior among Women in Two Border Mexican Cities. Front. Norte 2010, 22, 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pluut, H.; Ilies, R.; Curşeu, P.L.; Liu, Y. Social Support at Work and at Home: Dual-Buffering Effects in the Work-Family Conflict Process. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 2018, 146, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Fernández, R.; Rodríguez Llagüerri, S.; Presado, M.E.; Lavareda Baixinho, C.; Martín Vázquez, C.; Liébana Presa, C. Autoeficacia En La Lactancia y Apoyo Social: Un Estudio de Revisión Sistemática. New Trends Qual. Res. 2023, 18, e875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazeau, N.; Reisz, S.; Jacobvitz, D.; George, C. Understanding the Connection between Attachment Trauma and Maternal Self-Efficacy in Depressed Mothers. Infant. Ment. Health J. 2018, 39, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Pan, W.; Mu, P.; Gau, M. Birth Environment Interventions and Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Birth 2023, 50, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist-Mackey, A.N.; Wiley, M.L.; Erba, J. “You’re Doing Great. Keep Doing What You’re Doing”: Socially Supportive Communication during First-Generation College Students’ Socialization. Commun. Educ. 2018, 67, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero Rubio, P.J.; Morales Eliche, J.; Vega Cabezudo, L.; Montoro Martínez, J.; Linares Abad, M.; Álvarez Nieto, C. Actitud y Adaptación Maternal En El Embarazo. Cult. Cuid. Rev. Enfermería Y Humanidades 2007, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Nieto, N.; Herrera-Medina, R.; Fuertes-Bucheli, J.F.; Osorio-Murillo, O.; Castro-Valencia, C. Mejoramiento de La Lactancia Materna Exclusiva a Través de Una Estrategia de Información y Comunicación Prenatal y Posnatal, Cali (Colombia): 2014-2017. Univ. Salud 2023, 26, E1–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginbottom, G.M.; Morgan, M.; Alexandre, M.; Chiu, Y.; Forgeron, J.; Kocay, D.; Barolia, R. Immigrant Women’s Experiences of Maternity-Care Services in Canada: A Systematic Review Using a Narrative Synthesis. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigidi, S.; Busquets-Gallego, M. Interseccionalidades de Género y Violencias Obstétricas. MUSAS 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.; Erol, R.Y.; Luciano, E.C. Development of Self-Esteem from Age 4 to 94 Years: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 1045–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçalp, Ӧ.; Pena-Rosas, J.; Lawrie, T.; Bucagu, M.; Oladapo, O.; Portela, A.; Metin Gülmezoglu, A. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience—Going beyond Survival. BJOG 2017, 124, 860–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, S.; Conde, M.; González, S.; Parada, M.E. ¿Violencia Obstétrica En España, Realidad o Mito? 17.000 Mujeres Opinan. Musas 2019, 4, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smarandache, A.; Kim, T.H.M.; Bohr, Y.; Tamim, H. Predictors of a Negative Labour and Birth Experience Based on a National Survey of Canadian Women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldenström, U.; Hildingsson, I.; Rubertsson, C.; Rådestad, I. A Negative Birth Experience: Prevalence and Risk Factors in a National Sample. Birth 2004, 31, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, V.E.; Gilboa, A. What Is a Memory Schema? A Historical Perspective on Current Neuroscience Literature. Neuropsychologia 2014, 53, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monreal-Gimeno, M. del C.; Povedano-Díaz, A.; Martínez-Ferrer, B. Ecological Model of Factors Associated with Dating Violence. J. Educ. Teach. Train. 2014, 5, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, D. Pregnancy Loss: Consequences for Mental Health. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- deMontigny, F.; Verdon, C.; Meunier, S.; Gervais, C.; Coté, I. Protective and Risk Factors for Women’s Mental Health after a Spontaneous Abortion. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, D.C.; Craver, C. Effects of Pregnancy Loss on Subsequent Postpartum Mental Health: A Prospective Longitudinal Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsey, C.B.; Baptiste-Roberts, K.; Zhu, J.; Kjerulff, K.H. Effect of Previous Miscarriage on the Maternal Birth Experience in the First Baby Study. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2013, 42, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutti, M.H.; Armstrong, D.S.; Myers, J.A.; Hall, L.A. Grief Intensity, Psychological Well-Being, and the Intimate Partner Relationship in the Subsequent Pregnancy after a Perinatal Loss. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2015, 44, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumankuuro, J.; Crockett, J.; Wang, S. Sociocultural Barriers to Maternity Services Delivery: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of the Literature. Public Health 2018, 157, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liss, M.; Schiffrin, H.H.; Mackintosh, V.H.; Miles-McLean, H.; Erchull, M.J. Development and Validation of a Quantitative Measure of Intensive Parenting Attitudes. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2013, 22, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, H.D.; Henderson, A.C. The Modern Mystique: Institutional Mediation of Hegemonic Motherhood. Sociol. Inq. 2014, 84, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, O.; Berkovitch, N.; Segal-Engelchin, D. “I Kind of Want to Want”: Women Who Are Undecided About Becoming Mothers. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeussen, L.; Van Laar, C. Feeling Pressure to Be a Perfect Mother Relates to Parental Burnout and Career Ambitions. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, L.L.; van der Pijl, M.S.G.; Vedam, S.; Barkema, W.S.; van Lohuizen, M.T.; Jansen, D.E.M.C.; Feijen-de Jong, E.I. Assessing Dutch Women’s Experiences of Labour and Birth: Adaptations and Psychometric Evaluations of the Measures Mothers on Autonomy in Decision Making Scale, Mothers on Respect Index, and Childbirth Experience Questionnaire 2.0. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajizadeh, K.; Asghari Jafarabadi, M.; Vaezi, M.; Meedya, S.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S.; Mirghafourvand, M. The Psychometric Properties of the Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) for an Iranian Population. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creanga, A.A.; Syverson, C.; Seed, K.; Callaghan, W.M. Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2017, 130, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krukowski, R.A.; Jacobson, L.T.; John, J.; Kinser, P.; Campbell, K.; Ledoux, T.; Gavin, K.L.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Wang, J.; Kruper, A. Correlates of Early Prenatal Care Access among U.S. Women: Data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). Matern. Child. Health J. 2022, 26, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n=185) |

Spanish (n=53) |

Colombian (n=132) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women age (years) | 29.3±6.3 | 30.6±5.8 | 28.8±6.5 | 0.054 |

| Educational level | ||||

| Primary school | 4.9% (9) | 1.9% (1) | 6.1% (8) | 0.625 |

| Secondary school | 50.8% (94) | 52.8% (28) | 50.0% (66) | |

| University | 44.3% (82) | 45.3% (24) | 43.9% (58) | |

| Working situation | ||||

| Employed | 58.9% (109) | 52.8% (28) | 61.4% (81) | 0.367 |

| Unemployed | 41.1% (76) | 47.2% (25) | 38.6% (51) | |

| Civil status | ||||

| Single | 18.9% (35) | 18.9% (10) | 18.9% (25) | >0.999 |

| Married | 81.1% (150) | 81.1% (43) | 81.1% (107) | |

| Biparental family | 84.3% (156) | 90.6% (48) | 81.8% (108) | 0.209 |

| Total (n=185) |

Spanish (n=53) |

Colombia (n=132) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravida | 1.7±1.0 | 1.7±0.8 | 1.8±1.1 | 0.441 |

| Parity | 1.4±0.9 | 1.4±0.6 | 1.5±1.0 | 0.312 |

| Previous miscarriage | 0.2±0.5 | 0.4±0.7 | 0.1±0.4 | 0.020 |

| Previous labor by C-section | 0.7±0.8 | 0.3±0.6 | 0.8±0.9 | <0.001 |

| Postpartum time elapses (years) | 1.17±1.20 | 1.57±1.25 | 1.01±1.14 | 0.006 |

| Assisted reproduction techniques | 4.9% (9) | 9.4% (5) | 3.0% (4) | 0.122 |

| Multiple pregnancy in the last gestation | 1.6% (3) | 3.8% (2) | 0.8% (1) | 0.198 |

| Desired last pregnancy | 87.3% (144) | 100% (53) | 81.2% (91) | 0.002 |

| Last labor by C-section | 46.5% (86) | 22.6% (12) | 56.1% (74) | <0.001 |

| Gestational age (completed weeks) | 38.7±1.7 | 39.1±2.0 | 38.5±1.6 | 0.034 |

| Preterm birth | 7.6% (14) | 11.3% (6) | 6.1% (8) | 0.230 |

| Obstetrical complications | 31.4% (58) | 88.7% (47) | 93.9% (124) | 0.968 |

| Fetal complications | 17.8% (33) | 20.8% (11) | 16.7% (22) | 0.657 |

| Labor complications | 20.5% (38) | 28.3% (15) | 17.4% (23) | 0.146 |

| Postpartum complications | 17.8% (33) | 17.0% (9) | 18.2% (24) | >0.999 |

| Neonatal complications during labor | 13.5% (25) | 17.0% (9) | 12.1% (16) | 0.525 |

| Neonatal complications during postpartum | 10.3% (19) | 9.4% (5) | 10.6% (14) | >0.999 |

| Total (n=185) |

Spanish (n=53) |

Colombia (n=132) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience | 82.1±13.2 | 83.0±9.4 | 81.7±14.5 | 0.469 |

| PANAS positive | 36.7±7.6 | 37.7±7.1 | 36.2±7.8 | 0.252 |

| PANAS negative | 23.8±8.7 | 23.3±9.2 | 24.0±8.5 | 0.644 |

| Derailment | 20.4±5.4 | 19.4±5.2 | 20.9±5.5 | 0.055 |

| MBS-life | 17.3±7.4 | 14.8±6.4 | 18.4±7.6 | 0.003 |

| MBS-social | 8.0±3.7 | 6.7±2.6 | 8.5±3.9 | 0.001 |

| Total | Spanish | Colombian | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience | 0.11 [-0.06; 0.27] P=0.220 | 0.17 [-0.11; 0.43] P=0.235 | 0.09 [-0.13; 0.30] P=0.433 |

| PANAS positive | 0.17 [0.00; 0.33] P=0.047 | 0.17 [-0.11; 0.43] P=0.231 | 0.23 [0.04; 0.40] P=0.016 |

| PANAS negative | -0.10 [-0.26; 0.07] P=0.260 | -0.40 [-0.61; -0.14] P=0.004 | 0.04 [-0.17; 0.25] P=0.699 |

| Derailment | -0.09 [-0.25; 0.08] P=0.304 | -0.32 [-0.55; -0.04] P=0.023 | 0.02 [-0.20; 0.23] P=0.883 |

| MBS-life | 0.02 [-0.15; 0.19] P=0.808 | -0.10 [-0.37; 0.18] P=0.493 | 0.12 [-0.10; 0.32] P=0.289 |

| MBS-social | -0.08 [-0.24; 0.09] P=0.372 | -0.24 [-0.49; 0.04] P=0.089 | 0.01 [-0.21; 0.22] P=0.937 |

| MatCODE | 0.19 [0.03; 0.35] P=0.027 | 0.24 [-0.04; 0.48] P=0.095 | 0.16 [-0.06; 0.36] P=0.146 |

| MatER | -0.31 [-0.46; -0.16] P<0.001 | -0.42 [-0.62; -0.15] P=0.003 | -0.29 [-0.48; -0.08] P=0.007 |

| Global FMR |

FMR Information |

FMR Support |

FMR Participation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombian socio-health context | − | − | ||

| Women age | + | + | ||

| Previous miscarriage | − | − | ||

| Previous C-section | + | + | + | |

| Desired pregnancy | + | |||

| Last C-section | − | − | − | |

| Gestational age | + | + | ||

| Maternity beliefs as a social duty | − | |||

| Knowledge of maternity rights | + | |||

| Scarcity of resources | − | − | − |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).