1. Introduction

The United States faces a public health crisis of maternal morbidity and mortality, the contributors to which are incompletely understood. The maternal mortality rate (MMR), defined by the World Health Organization as number of deaths during pregnancy and up to 42 days postpartum per 100,000 live births, has increased annually from 17.4 to 32.9 from 2018-2021 [

1]. An estimated 80% of maternal deaths are preventable [

2]. Nation-wide data, on average, obscure the wide disparities by race and geography. Specifically, the MMR for non-Hispanic Black birthing people is 2.6 times the rate of their White counterparts. MMR varies greatly by state, ranging from 10.1 in California to 43.0 in Mississippi [

3]. Mental health conditions, hemorrhage, and coronary conditions were the most common underlying causes of death (22.7%, 13.7%, and 12.8%, respectively) for maternal deaths up to one year postpartum [

2,

4]. Homicide is another significant cause of maternal mortality especially among Black women. The prevalence of homicide was 16% higher during pregnancy or within 42 days postpartum than in nonpregnant females of reproductive age and exceeded all other causes of maternal mortality by more than two-fold [

5], highlighting dynamic contributions to maternal death beyond the medical.

The drivers of this crisis are complex and multifactorial. Social determinants of health shape access to quality prenatal and postpartum care. Disadvantaged communities, often shaped by a legacy of racism and redlining, suffer not only from poorer access to maternal healthcare [

6], but also to social conditions, such as poverty and chronic racial stress, that make chronic disease and comorbidities more likely [

7].

Furthermore, the political landscape shapes access to maternity care through regulation of procedures and funding for maternity care services. States with less restrictive abortion laws [

8], paid family leave [

9], and Medicaid expansion [

10] tend to have lower rates of maternal mortality. In a review of maternal deaths from 2015 through 2018, there was a 7% higher total maternal mortality in states with restrictive abortion laws [

11]. The COVID pandemic has also contributed to worsening maternal outcomes, both directly through disease, as well as indirectly by straining healthcare systems and driving patients to defer care [

12]. Finally, a nationwide trend toward motherhood at older ages increases the likelihood of comorbidities and high-risk pregnancies [

13].

Mistreatment of birthing persons during childbirth is an understudied factor influencing maternal outcomes. While the World Health Organization upholds Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) as a vital component of birthing persons’ health, Disrespect and Abuse (D&A) in childbirth has been identified as a global issue [

14]. D&A, also known as obstetric violence, consists of physical abuse, non-consented care, non-confidential care, non-dignified care, discrimination, abandonment of care, and detention in facilities [

15]. Bekele et al (2020) characterizes disrespectful care as “one of the silent causes of maternal mortality and morbidity worldwide” [

16]. D&A has been associated with decreased uptake of healthcare services, psychological trauma, and postpartum depression [

17]. In the US context, where mental health conditions and lack of care access contribute highly to mortality, understanding D&A is necessary to improve maternal health. However, studies in the US are limited [

18,

19,

20]. One in six US birthing persons report being mistreated, with higher rates of mistreatment reported by younger patients, those with higher-risk pregnancies, and by Black, Indigenous, and people of color [

20].

The barriers to respectful maternity care cannot be fully addressed without an understanding of the perspectives of obstetric care providers. Their insights can expand beyond the interaction dynamics of the patient-provider dyad and identify root causes of D&A. Physicians, midwives, nurses, and other birth attendants are uniquely positioned as advocates for respectful maternity care, not only in their patient interactions, but also within their healthcare organizations to identify policies and structural influences on best practices. The aim of this study is to examine obstetric care providers’ observation and perception of underlying root causes of disrespect and abuse at an urban tertiary care center in the United States.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study of labor and delivery staff was carried out from April 2023 to January 2024 at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, Massachusetts. MGH is an academic teaching hospital that provides care for an estimated 3,800 births annually. The results presented here are data from an online survey, which was conducted as part of a mixed-method study that also included qualitative interviews.

Participants in this study were health care professionals (HCPs) who provided care to patients in childbirth. Physicians (including resident physicians), midwives, and nurses who had worked on the hospital labor and delivery floor for at least one year were included. Medical students and resident physicians with less than one year of clinical experience were excluded.

The study protocol was approved by the Mass General Brigham Human Research Committee. Data was collected through an open and anonymous voluntary electronic survey using the REDCap application for online surveys. To ensure confidentiality, the data collection tool was available as an open survey. Participants received a written statement of the research study aims and risks before voluntary completion of the online survey. The study was advertised through department-wide emails, presentation at staff meetings, and flyers posted on the labor and delivery floor.

The survey contained questions about demographic characteristics, observation of disrespectful behaviors at MGH, performance of respectful care, stress and support factors, and opinions on disrespectful care. The domains of disrespect were based on the framework first categorized by Bowser and Hill: [

15] physical abuse, non-consented care, non-confidential care, non-dignified care, discrimination, abandonment of care, and detention in facilities. The last category, detention in facilities, was excluded, as it has not historically been applicable to MGH. Questions about respectful care were modified from the US Person-Centered Maternity Scale (PCMC-US) [

21] and adapted to fit the provider perspective of respectful maternity care performed. Stress was assessed with the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) [

22]. The study questions were primarily closed-ended but included several open-response questions. The survey was pilot tested by a physician, a nurse, and a midwife to check for clarity. The full questionnaire is available as supplementary data.

The survey received 56 responses. Ten entries were removed due to lack of completion. Since the open nature of the survey allowed for the possibility that a single respondent could answer multiple times, data was examined for duplicate responses. Data was cleaned and analyzed using R version 023.03.0. For the primary analysis, we calculated descriptive statistics of proportions and frequencies of variables of interest. Exploratory analysis examined the difference in proportions between different occupations (physicians, midwives, and nurses) using Fisher’s Exact Test. Open response questions were coded using Dedoose version 9.0.107, a qualitative analysis software.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Forty-six providers completed the survey. Response rate to the open internet survey varied depending on profession: 58.6% of physicians, 66.7% of midwives, and 40.5% of nurses responded. Nurses constituted half the respondents, reflecting the significant role and number of nurses in the makeup of the labor and delivery workforce. Racial and ethnic diversity of the sample was limited, with 80.4% of respondents identifying as white and 91.3% identifying as non-Hispanic. This is consistent with the demographics of hospital staff at MGH. Nine out of ten of the respondents were women, reflecting outsized participation of women in the obstetrics and nursing field [

23]. A slight majority (58.7%) were relatively new to MGH, with less than 5 years of experience. Full demographics of the sample are shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Knowledge of Disrespectful Care

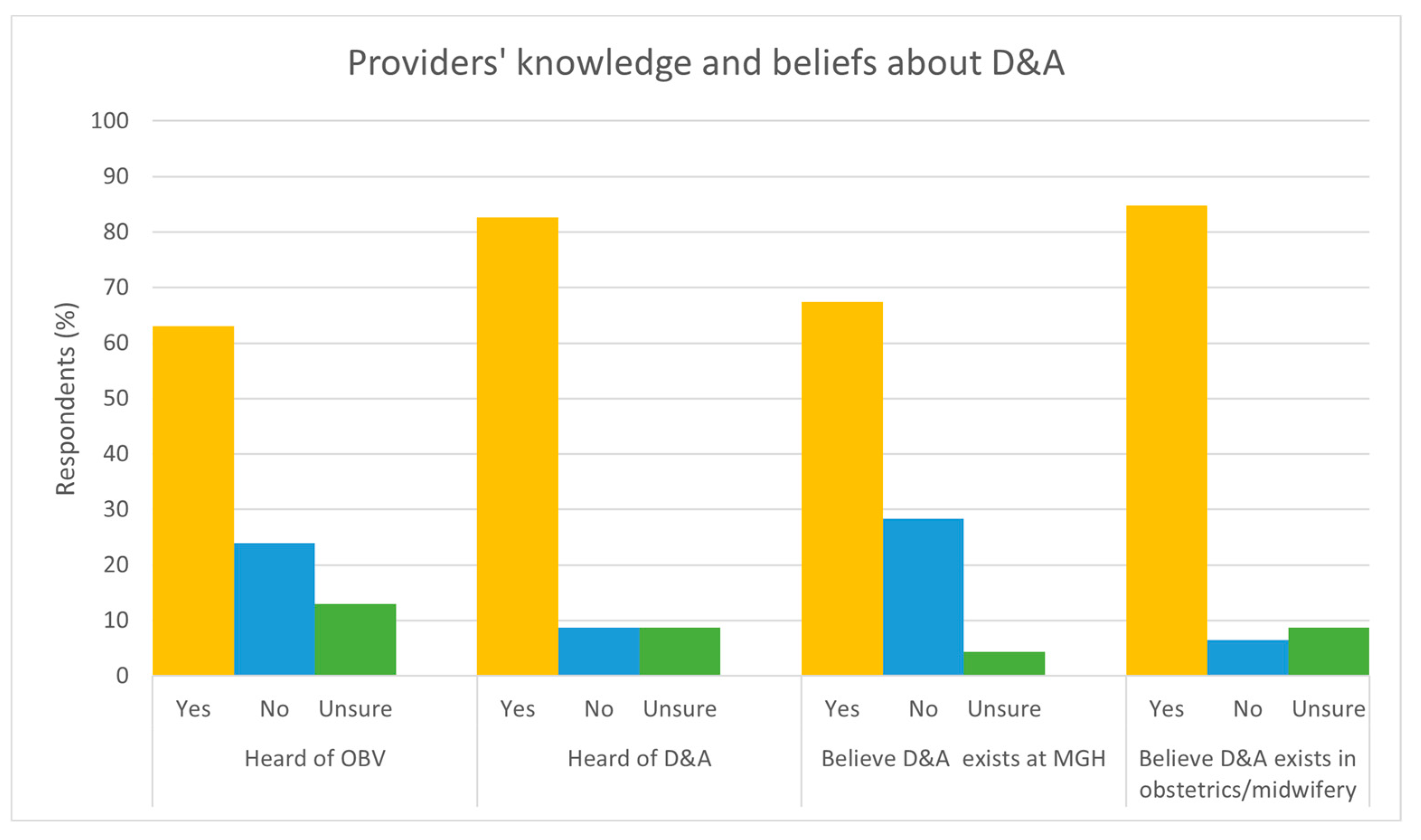

Respondents reported a high baseline knowledge of D&A/OBV. A large majority (84.8%) believed that disrespect and abuse is an issue in the obstetrics field, and a smaller majority (67.4%) believed that it is an issue at MGH specifically. “Disrespect and abuse” was a more familiar term than “obstetric violence”, although both terms were recognized by most respondents. Figure 1 graphs providers’ knowledge and beliefs about D&A.

3.3. Disrespectful Care Witnessed

The most reported observed disrespectful behavior was dismissing patients’ pain (87.0%), followed by discriminatory care based on physical characteristics (67.4%) and race (65.2%), and uncomfortable vaginal examinations (65.2%). The full results are listed in

Table 2.

Qualitative responses further elaborated on dismissal of patients’ pain or other concerns, one noting they had witnessed “Dismissing concerns about fetal status, nausea, anxiety.” Reports of derogatory comments in the patient’s presence were not as common (30.4%), though some noted that some verbal disrespect may be unintentional, or not take place in the patient’s presence:

“There are times when I feel the language people use, whether intentionally or not, can sound rude and disrespectful.”

“Conversations outside of the room about a patient or family member that is judgmental or unkind.”

Others noted poor communication and lack of true informed consent, with three write-in responses specifically mentioning “coercion.” One responded elaborated in this way:

“Adequate consenting by providers for medications and procedures in labor feels inadequate. Many of the information that I hear providers offer to patients during care planning feels incomplete and biased towards what the provider most wants the patient to do/feels most convenient.”

Uncomfortable vaginal examinations (65.2%) and not allowing patients to give birth in their preferred position (63%) were the most noted types of physical disrespect, while restraining (9%) was very rarely witnessed. When asked to elaborate further, five responses specifically noted Cook balloon placement as being problematic, for example:

“Trying multiple times to place cook balloons on patients who are uncomfortable”

“After traumatic cook balloon placement, MD agreed he wasn’t going to put balloon to tension right away and then pulled balloon so hard that patient had vagal response and prolonged deceleration that resulted in unnecessary intervention and unnecessary emotional and physical trauma to patient”

Compared with other domains of disrespect, unnecessary procedures or procedures performed without explanations were less frequently reported. The most problematic procedure was artificial rupture of membrane (39.1% reported witnessing or hearing about this being performed without explanation) while fewer than one-fifth of respondents reported witnessing an unexplained Cesarean section (C-section), stitching, transfusion, sterilization, injection, shaving, or catheter placement. A slight majority, 53.7%, noted neglecting or leaving a patient unattended.

A majority reported discriminatory care based on race (65.2%), culture (60.9%) or physical characteristics (67.4%). 45.7% reported discrimination based on language, and several qualitative responses expounded upon this type of discrimination:

“Often a lack of respect and consideration of patients whose primary language is not English - increasing volume, not addressing them directly, making side comments to staff.”

The proportion of respondents who reported observing disrespectful behaviors was similar across occupations, with some exceptions. Nurses were significantly more likely than physicians to report witnessing or hearing about a patient being threatened with an unnecessary C-section (69.6% of nurses compared to 12.5% of midwives and 13.3% of physicians, Fisher’s exact test p= 0.0004126). They also were more likely to report C-sections being carried out to speed the birth process when the mother and the fetus were not compromised (52.2% of nurses compared to 12.5% of midwives and 13.3% of physicians, Fisher’s exact test p= 0.02005).

3.4. Respectful Care Performed

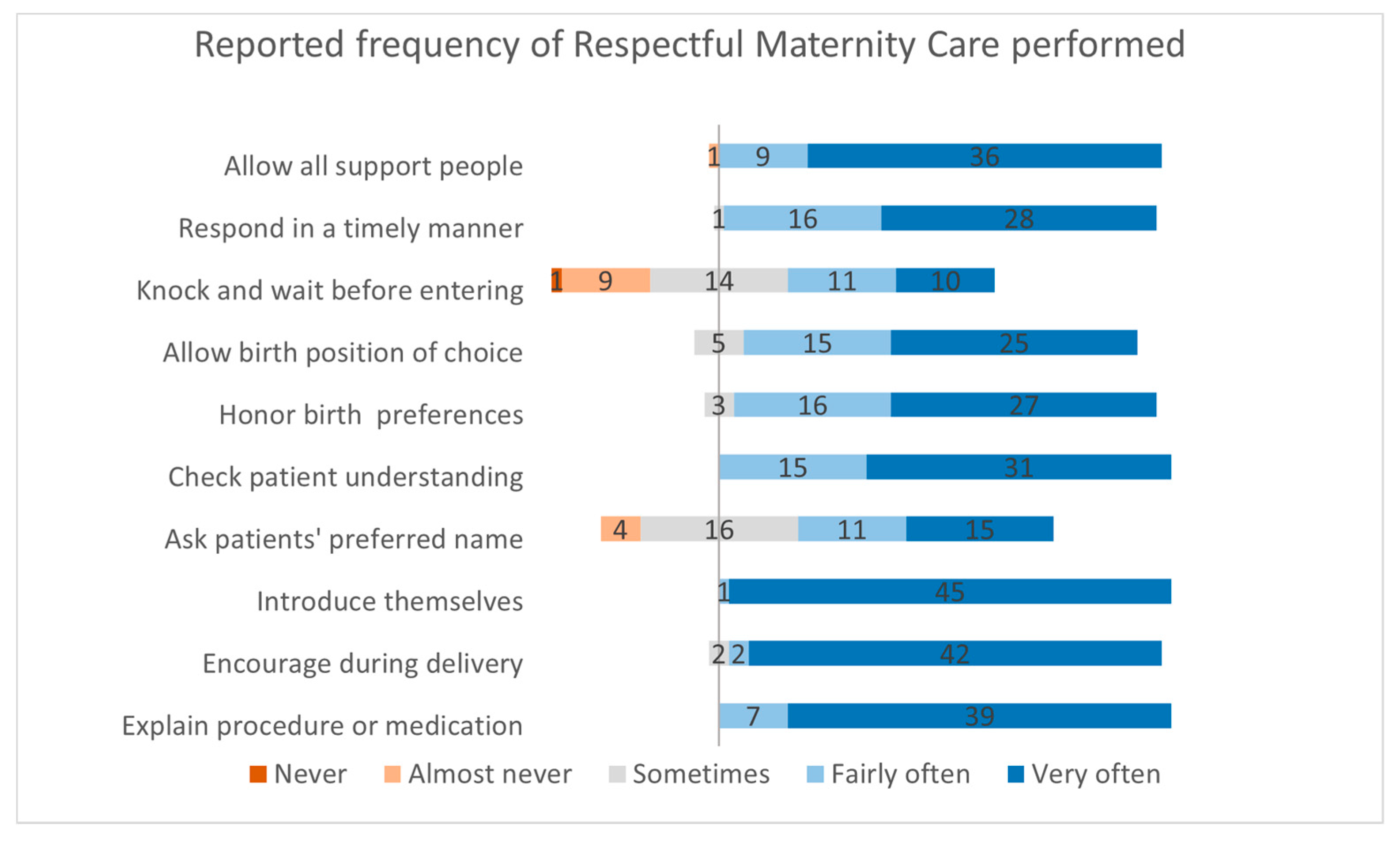

Respectful care is illustrated in Figure 2. Staff reported performing respectful care behaviors often. A vast majority (84.8-100%) of respondents reported performing most respectful items fairly or very often, except for asking patients for their preferred name (56.5%) and knocking and waiting for an answer when entering patient’s rooms (45.6%).

3.5. Stress & Support Factors

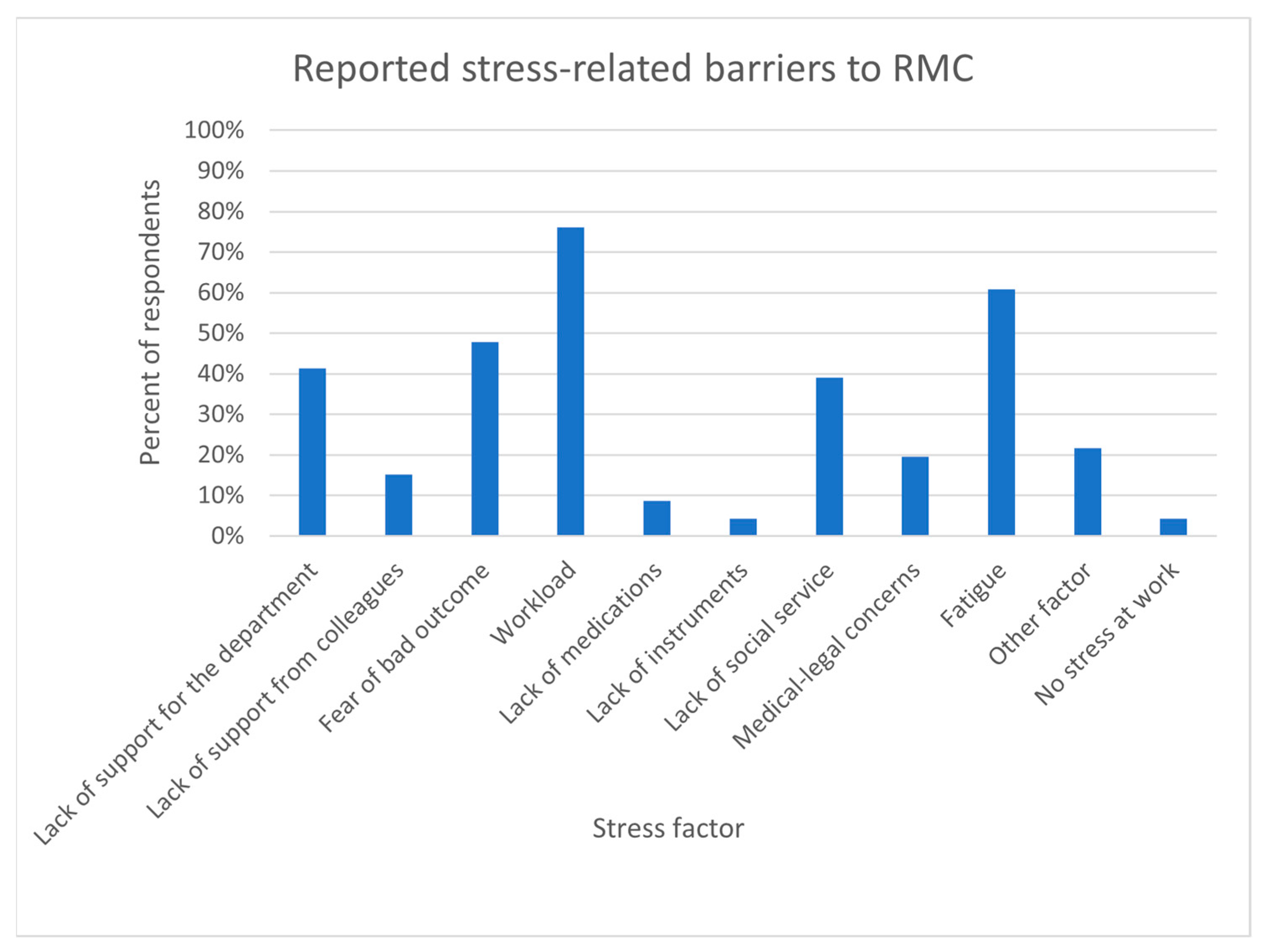

The median Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) score was 6 (interquartile range: 3-8) out of 16, with 16 indicating the highest level of stress. Frequency of responses for stress factors are displayed in Figure 3. The most-commonly reported stress-related barriers to RMC were related to being overburdened at work: 76.1% cited workload and 60.9% cited fatigue. Open-ended responses also pointed to inadequate number or experience level of staff, with one respondent noting “Leaders not creating a system with adequate staffing to compassionately, safely provide excellent care to all our patients.” While lack of time may be an issue, lack of supplies does not seem to be a major barrier: less than one in ten cited a lack of medications and/or a lack of instruments as a problem.

4. Discussion

While respectful maternity care was performed at MGH in the majority of encounters, a survey of forty-six obstetrical providers identified that D&A/OBV remains an issue in childbirth. Specific clinician observations included the dismissal of pain, discriminatory behavior based on physical characteristics and race, and uncomfortable vaginal examinations. Clinicians identified the most common stress-related barriers to providing respectful maternity care included workload and fatigue.

This study corroborates findings from other US-based studies surveying patients that report discrimination based on sociodemographic factors [

20,

24]. This particularly highlights the need for interventions to address both clinician implicit and explicit bias towards patients from marginalized backgrounds [

25]. These findings stress the interplay between D&A/OBV and maternal outcomes, specifically as ‘delay, denial, and dismissal’ as contributing factors to obstetric racism in maternal morbidity and mortality [

26].

While most existing respectful maternity care-related studies in the US focus on the patient experience during childbirth, our study is among the first investigation of specifically clinician perspectives. Morton et al (2018) surveyed American and Canadian doulas and nurses, quantifying their reports of witnessed disrespect [

19]. While other global studies have been performed on clinician perspectives of root causes of disrespect in Nigeria and Kenya, these may not be fully generalizable to the US context. Notably, Afulani et al’s analysis in Kenya highlight provider stress and burnout, system infrastructure, and provider bias as contributing factors in D&A/OBV [

27]. Our study also highlights the contributions of clinician burnout and structural factors such as workload, lack of support, and fatigue on patient experiences of care. Our findings affirm the need for provider-based interventions as pointed out by the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report’s call to action for clinician training surrounding “discrimination, stigma and unconscious bias, cultural awareness, and communication techniques in the context of broader quality improvement initiatives” [

28].

The limitations of our study include its small sample size and low survey response rate and therefore may not be generalizable to other settings. The response rate for nurses (40.5%) was lower than the physician and midwife response rate (58.6% and 66.7% respectively), which could be due to the irregularity of many nursing shifts and number of nurses working per diem. Our response rates are consistent with those reported in a review of health professional response rates in online surveys, which ranged from 36.77% - 57.4% [

29]. When interpreting the results, it is important to note that clinician reports of D&A/OBV may not correlate with individual patient experiences. The proportion of providers who report witnessing D&A/OBV should not be conflated with the true prevalence of such incidences. Multiple providers may have observed the same incident, and providers who have worked at a facility over a longer period have had more years of experience over which to witness such incidents. Social desirability bias may also reduce reports of observed D&A/OV on the labor and delivery unit, and selection bias could be present if respondents who were more knowledgeable about D&A had higher response rates that those who were less knowledgeable.

It is also likely that sensitivity of the subject may have deterred providers from participating. Health care providers have shown some level of apprehension with the use of “obstetric violence” as a term to capture disrespectful maternity care [

30], and may describe disrespectful care using other terminology such as “birth trauma” instead [

31]. One commentary suggests changing the term to “obstetrical mistreatment” to better define the challenge to respectful care and reduce stigma when care falls short [

30]. It is possible that the ongoing debate and confusion around defining such mistreatment in care, and the role in which a provider may play, was a significant deterrent and thus a reason for the low response rate. Providers, as key stakeholders in the pursuit of respectful maternity care, must be empowered to improve the quality of care without being overly subjected to blame for system-level drivers. Sustained progress in respectful maternity care requires moving from a “blame culture” to a “just culture”, balancing individual accountability with systems-level accountability, with an emphasis on organizational learning and continuous improvement [

32].

Results from this study will guide training initiatives for clinicians staffing the labor and delivery unit to improve birth equity outcomes. Future research can help assess the efficacy of clinician-facing interventions on provision of respectful maternity care for birthing persons. In summary, our study demonstrates that barriers to respectful maternity are witnessed in a contemporary US obstetrics unit at a major tertiary hospital and may be a contributor to the maternal morbidity and mortality crisis in the United States.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and C.D.B.; methodology, A.G., C.D.B., K.D.F., S.T. and K.V.K; investigation, K.V.K., A.C., P.B. and A.F.; formal analysis, K.D.F. and S.N.; writing—original draft preparation, K.D.F. and S.T.; writing—review and editing, S.N., C.D.B., A.G., K.V.K., A.C. A.F., and P.B.; Visualization, K.D.F.; supervision, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Massachusetts General Hospital endowed Global Health Fund – Strength & Serenity, Fund number 1200 020707.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Mass General Brigham Human Research Committee (protocol 2022P003287, approved Feb 27, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support and guidance of Susan Hernandez CNM MSN FACNM, Legislative Co-Chair, Massachusetts American College of Nurse-Midwives; Rebecca D. Minehart MD MSHPEd, Division Chief, Obstetric Anesthesiology at Brown University Health; and Dr. Jeffrey Ecker MD, Chief of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hoyert D. Maternal mortality rates in the United States, 2021 [Internet]. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.); 2023 Mar [cited 2023 Sep 29]. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/124678.

- Trost S, Beauregard J, Nije F. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 29]. Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US States, 2017–2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/erase-mm/data-mmrc.html.

- Maternal deaths and mortality rates: Each state, the District of Columbia, United States, 2018-2021. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Ststistics (NCHS), National Vital Statistics System.

- Hollier LM, Busacker A, Njie F, Syverson C, Goodman DA. Pregnancy-Related Deaths Due to Hemorrhage: Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, 2012–2019. Obstet Gynecol. 2024 Aug;144(2):252. [CrossRef]

- Wallace M, Gillispie-Bell V, Cruz K, Davis K, Vilda D. Homicide During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period in the United States, 2018–2019. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Nov;138(5):762–9. [CrossRef]

- Crear-Perry J, Correa-de-Araujo R, Lewis Johnson T, McLemore MR, Neilson E, Wallace M. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health. J Womens Health. 2021 Feb;30(2):230–5. [CrossRef]

- Howell EA, Zeitlin J. Improving hospital quality to reduce disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2017 Aug 1;41(5):266–72. [CrossRef]

- Kheyfets A, Dhaurali S, Feyock P, Khan F, Lockley A, Miller B, et al. The impact of hostile abortion legislation on the United States maternal mortality crisis: a call for increased abortion education. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Dec 5 [cited 2024 Apr 19];11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1291668/full.

- Bhatia, R. Family Leave and Maternal Mortality in the US. JAMA. 2023 Oct 10;330(14):1387. [CrossRef]

- Eliason, EL. Adoption of Medicaid Expansion Is Associated with Lower Maternal Mortality. Womens Health Issues. 2020 May 1;30(3):147–52. [CrossRef]

- Vilda D, Wallace ME, Daniel C, Evans MG, Stoecker C, Theall KP. State Abortion Policies and Maternal Death in the United States, 2015‒2018. Am J Public Health. 2021 Sep;111(9):1696–704. [CrossRef]

- Goyal M, Singh P, Singh K, Shekhar S, Agrawal N, Misra S. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal health due to delay in seeking health care: Experience from a tertiary center. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):231–5. [CrossRef]

- Davis NL, Hoyert DL, Goodman DA, Hirai AH, Callaghan WM. Contribution of maternal age and pregnancy checkbox on maternal mortality ratios in the United States, 1978–2012. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Sep;217(3):352.e1-352.e7.

- World Health Organization. The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth: WHO statement. 2014.

- Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring Evidence for Disrespect and Abuse in Facility-Based Childbirth: Report of a Landscape Analysis. USAID-Tract Proj. 2010.

- Bekele W, Bayou NB, Garedew MG. Magnitude of disrespectful and abusive care among women during facility-based childbirth in Shambu town, Horro Guduru Wollega zone, Ethiopia. Midwifery. 2020 Apr 1;83:102629. [CrossRef]

- Perrotte V, Chaudhary A, Goodman A. “At Least Your Baby Is Healthy” Obstetric Violence or Disrespect and Abuse in Childbirth Occurrence Worldwide: A Literature Review. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;10(11):1544–62. [CrossRef]

- Liese KL, Davis-Floyd R, Stewart K, Cheyney M. Obstetric iatrogenesis in the United States: the spectrum of unintentional harm, disrespect, violence, and abuse. Anthropol Med. 2021 Jun;28(2):188–204. [CrossRef]

- Morton CH, Henley MM, Seacrist M, Roth LM. Bearing witness: United States and Canadian maternity support workers’ observations of disrespectful care in childbirth. Birth Berkeley Calif. 2018 Sep;45(3):263–74. [CrossRef]

- Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, Rubashkin N, Cheyney M, Strauss N, et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019 Jun 11;16(1):77. [CrossRef]

- Afulani PA, Altman MR, Castillo E, Bernal N, Jones L, Camara T, et al. Adaptation of the Person-Centered Maternity Care Scale in the United States: Prioritizing the Experiences of Black Women and Birthing People. Womens Health Issues. 2022 Jul 1;32(4):352–61. [CrossRef]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. [CrossRef]

- Shannon G, Minckas N, Tan D, Haghparast-Bidgoli H, Batura N, Mannell J. Feminisation of the health workforce and wage conditions of health professions: an exploratory analysis. Hum Resour Health. 2019 Dec;17(1):72.

- Patel SJ, Truong S, DeAndrade S, Jacober J, Medina M, Diouf K, et al. Respectful Maternity Care in the United States-Characterizing Inequities Experienced by Birthing People. Matern Child Health J. 2024 Jul;28(7):1133–47. [CrossRef]

- Green CL, Perez SL, Walker A, Estriplet T, Ogunwole SM, Auguste TC, et al. The Cycle to Respectful Care: A Qualitative Approach to the Creation of an Actionable Framework to Address Maternal Outcome Disparities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 May 6;18(9):4933. [CrossRef]

- Cantor AG, Jungbauer RM, Skelly AC, Hart EL, Jorda K, Davis-O’Reilly C, et al. Respectful Maternity Care : A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2024 Jan;177(1):50–64.

- Afulani PA, Kelly AM, Buback L, Asunka J, Kirumbi L, Lyndon A. Providers’ perceptions of disrespect and abuse during childbirth: a mixed-methods study in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2020 Jun 1;35(5):577–86. [CrossRef]

- Mohamoud YA. Vital Signs: Maternity Care Experiences — United States, April 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 2];72. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7235e1.htm.

- L’Ecuyer KM, Subramaniam DS, Swope C, Lach HW. An Integrative Review of Response Rates in Nursing Research Utilizing Online Surveys. Nurs Res. 2023 Dec;72(6):471. [CrossRef]

- Chervenak FA, McLeod-Sordjan R, Pollet SL, De Four Jones M, Gordon MR, Combs A, et al. Obstetric violence is a misnomer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024 Mar;230(3S):S1138–45. [CrossRef]

- Salter C, Wint K, Burke J, Chang JC, Documet P, Kaselitz E, et al. Overlap between birth trauma and mistreatment: a qualitative analysis exploring American clinician perspectives on patient birth experiences. Reprod Health. 2023 Apr 21;20(1):63. [CrossRef]

- Khatri N, Brown GD, Hicks LL. From a blame culture to a just culture in health care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2009;34(4):312–22. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Respondent demographics.

Table 1.

Respondent demographics.

| Variable |

N (%) |

| Occupation |

|

| Nurse |

23 (50.0%) |

| Midwife |

8 (17.4%) |

| Physician |

15 (32.6%) |

| Age |

|

| Less than 30 years old |

10 (21.7%) |

| 30-39 years old |

17 (37%) |

| 40-49 years old |

8 (17.4%) |

| 50 or older |

11 (23.9%) |

| Gender |

|

| Man |

4 (8.7%) |

| Woman |

42 (91.3%) |

| Other |

0 (0%) |

| Education |

|

| Associate’s degree or diploma program (ex: ADN) |

1 (2.2%) |

| Bachelor’s degree (ex: BSN) |

19 (41.3%) |

| Master’s degree (ex: MSN, CNM) |

11 (23.9%) |

| Doctorate degree (ex: MD, DNP) |

15 (32.6%) |

| Race |

|

| Asian or Pacific Islander |

3 (6.5%) |

| Black or African American |

3 (6.5%) |

| White |

37 (80.4%) |

| Multiracial/Other race |

2 (4.3%) |

| NA |

1 (2.2%) |

| Ethnicity |

|

| Hispanic or Latino |

3 (6.5%) |

| Non-Hispanic or non-Latino |

42 (91.3%) |

| NA |

1 (2.2%) |

| Years of Experience at MGH |

|

| 1-4 years |

27 (58.7%) |

| 5-9 years |

5 (10.9%) |

| 10-14 years |

1 (2.2%) |

| 15+ years |

13 (28.3%) |

| Years of Experience in Obstetric Care |

|

| 1-4 years |

18 (39.1%) |

| 5-9 years |

9 (19.6%) |

| 10-14 years |

3 (6.5%) |

| 15+ years |

16 (34.8%) |

Table 2.

Disrespectful care witnessed or heard about.

Table 2.

Disrespectful care witnessed or heard about.

| Domain of disrespect |

Item |

N (%) |

| Verbal disrespect |

Dismissing/disbelieving a patient’s reports of pain |

40 (87.0%) |

| Scolding |

29 (63.0%) |

| Threatening with unnecessary C-Section |

19 (41.3%) |

| Other verbal/psychological disrespect |

19 (41.3%) |

| Derogatory comment |

14 (30.4%) |

| Physical disrespect |

Vigorous/uncomfortable vaginal examinations |

30 (65.2%) |

| Not allowing patients position of choice in birth |

29 (63.0%) |

| Other physical disrespect |

9 (19.6%) |

| Restraining |

4 (8.7%) |

| Privacy violations/ Neglect/ Unnecessary procedures |

Asking private questions in the presence of others |

27 (58.7%) |

| Leaving patients unattended for long periods of time |

25 (54.3%) |

| Neglecting a patient |

24 (52.2%) |

| Medically unnecessary C-section |

15 (32.6%) |

| Medically unnecessary episiotomy |

13 (28.3%) |

| Delivery or examination in public |

3 (6.5%) |

| Other disrespectful/abusive actions |

2 (4.3%) |

| Discriminatory care |

Discriminatory care based on physical characteristics |

31 (67.4%) |

| Discriminatory care based on race |

30 (65.2%) |

| Discriminatory care based on culture |

28 (60.9%) |

| Discriminatory care based on language |

21 (45.7%) |

| Discriminatory care based on age |

20 (43.5%) |

| Discriminatory care based on immigration status |

14 (30.4%) |

| Discriminatory care based on number of children |

14 (30.4%) |

| Discriminatory care based on socio-economic status |

13 (28.3%) |

| Discriminatory care based on gender identity or sexual orientation |

12 (26.1%) |

| Discriminatory care based on marital status |

6 (13%) |

| Discriminatory care based on insurance status |

4 (8.7%) |

| Discriminatory care based on other patient characteristic |

3 (6.5%) |

| Performance of procedures without explanation |

Artificial rupture of membrane |

18 (39.1%) |

| Episiotomy |

16 (34.8%) |

| Stripping membrane |

16 (34.8%) |

| Rectal exam |

11 (23.9%) |

| Vaginal exam |

11 (23.9%) |

| Placement of FSE or IUPC |

10 (21.7%) |

| Placement of Foley catheter |

7 (15.2%) |

| C-section |

6 (13%) |

| Shaving |

6 (13%) |

| Stitching |

5 (10.9%) |

| Placement of straight catheter |

5 (10.9%) |

| Injection |

4 (8.7%) |

| Use of assistive device for delivery |

3 (6.5%) |

| Blood transfusion |

1 (2.2%) |

| Sterilization |

1 (2.2%) |

| Other procedure |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).