Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fulfillment in Maternity Rights Instrument

2.2. Evaluation by Judges

2.3. Pilot Test

2.4. Participants and Study Design

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Content Validity

3.2. Descriptive of Sample

3.3. Construct Validity by Factor Analysis

3.4. Divergent and Know-Groups Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item | Factor | During last pregnancy | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I1 | 1 | You had sufficient and clear information about the healthcare procedures that you and your newborn should have for a healthy pregnancy. | |||||

| I4 | 1 | You had sufficient and clear information about the administrative steps you had to take to ensure your healthcare. | |||||

| I7 | 1 | You had sufficient and clear information about the medical procedures performed on you. | |||||

| I42 | 2 | Your privacy or avoidance of exposure of your body (covering intimate parts, regulating the exhibition of your body to persons not involved in the treatment) was respected during healthcare. | |||||

| I45 | 2 | Confidentiality of information about your health was maintained during healthcare. | |||||

| I15 | 3 | Your written consent was requested for healthcare procedures involving the invasion of your body (vaginal examinations or ultrasound). | |||||

| I27 | 4 | If you requested family support or accompaniment during healthcare, they were allowed access. If you never requested it, check option "4". | |||||

| I35 | 5 | During the healthcare, your feelings, emotions, doubts, and opinions were listened. | |||||

| Item | Factor | During last labor | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I2 | 1 | You had sufficient and clear information about the healthcare procedures that you and your newborn should have for an effective delivery/C-section. | |||||

| I5 | 1 | You had sufficient and clear information about the administrative steps you had to take to ensure your healthcare. | |||||

| I46 | 2 | Confidentiality of information about your and your newborn’s health status was maintained during healthcare. | |||||

| I50 | 2 | If your rights were violated during healthcare, you consider that you defended them. If your rights were not violated, answer option "4". | |||||

| I13 | 3 | You were asked for your verbal consent for healthcare processes that involved the invasion of your body (perineal cutting or ultrasounds). | |||||

| I16 | 3 | You were asked for your written consent for healthcare processes involving invasion of your body (perineal cutting or ultrasound). | |||||

| I28 | 4 | If you requested family support or accompaniment during healthcare, they were allowed access. If you never requested it, check option "4". | |||||

| I22 | 5 | They respected your decisions on self-care and newborn care behaviors that were not risky for either of you. | |||||

| I31 | 5 | Health professionals performed or allowed to you to perform pain control (medication, application of compresses, walking, postural control). | |||||

| I36 | 5 | During healthcare, they listened to your feelings, emotions, doubts, and opinions. | |||||

| Item | Factor | During last immediate postpartum (up to 40 days after labor) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I3 | 1 | You had sufficient and clear information about the healthcare procedures that you and your newborn should have for a healthy postpartum period. | |||||

| I6 | 1 | You had sufficient and clear information about the administrative steps you had to take to ensure your healthcare. | |||||

| I9 | 1 | You had sufficient and clear information about the medical procedures that were performed on you. | |||||

| I11 | 1 | You had sufficient and clear information to initiate and maintain breastfeeding in a correct and painless way. | |||||

| I47 | 2 | Confidentiality of information about your and your newborn’s health status was maintained during healthcare. | |||||

| I49 | 2 | You consider that some of the healthcare practices you received may have been both uncomfortable and unnecessary (application of bandages, among others). | |||||

| I17 | 3 | You were asked for your written consent for healthcare procedures that involved invasion of your body (dressings, tubal ligation, or ultrasound). | |||||

| I29 | 4 | In the case of having requested family support or accompaniment during healthcare, they were you allowed access. If you never requested it, check option "4". | |||||

| I23 | 5 | They respected your decisions on self-care and newborn care behaviors that were not risky for either of you (type of contraception, type of breastfeeding, among others). | |||||

| I32 | 5 | Health professionals performed or allowed to you to perform actions to control pain (medication, application of compresses, etc.). | |||||

| I37 | 5 | During healthcare, they listened to your feelings, emotions, doubts, and opinions. | |||||

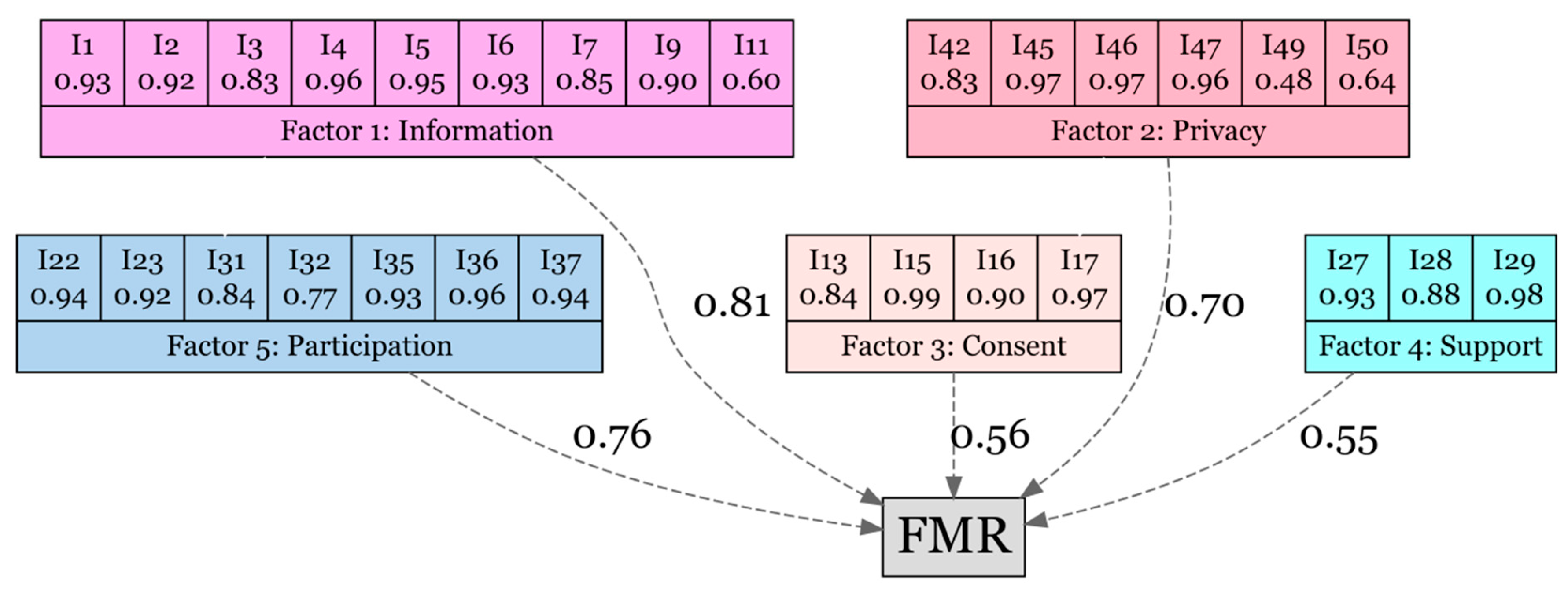

| Factor 1 gathers items related to receive adequate healthcare information (Factor 1=Information), factor 2 gathers rights related to privacy and confidentiality of health information (Factor 2=Privacy), factor 3 refers to consent to medical procedures (Factor 3=Consent), factor 4 refers to social support during maternity (Factor 4=Support) and factor 5 to participation and active listening in medical treatment (Factor 5=Participation). | |||||||

References

- Bohren, M.A.; Vogel, J.P.; Hunter, E.C.; Lutsiv, O.; Makh, S.K.; Souza, J.P.; Aguiar, C.; Saraiva Coneglian, F.; Diniz, A.L.A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLoS Med 2015, 12, e1001847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroll, A.-M.; Kjærgaard, H.; Midtgaard, J. Encountering Abuse in Health Care; Lifetime Experiences in Postnatal Women - a Qualitative Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Fernandez, C.S.; de la Calle, M.; Arribas, S.M.; Garrosa, E.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Factors Associated with Obstetric Violence Implicated in the Development of Postpartum Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review. Nurs Rep 2023, 13, 1553–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumont, M.S.; Dekker, C.S.; Rabinovitch Blecker, N.; Turlington Burns, C.; Strauss, N.E. Every Mother Counts: Listening to Mothers to Transform Maternity Care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023, 228, S954–S964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasse, M.; Schroll, A.; Karro, H.; Schei, B.; Steingrimsdottir, T.; Van Parys, A.; Ryding, E.L.; Tabor, A. Prevalence of Experienced Abuse in Healthcare and Associated Obstetric Characteristics in Six European Countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015, 94, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, M.A.; Mehrtash, H.; Fawole, B.; Maung, T.M.; Balde, M.D.; Maya, E.; Thwin, S.S.; Aderoba, A.K.; Vogel, J.P.; Irinyenikan, T.A.; et al. How Women Are Treated during Facility-Based Childbirth in Four Countries: A Cross-Sectional Study with Labour Observations and Community-Based Surveys. The Lancet 2019, 394, 1750–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, A.J.; Wijma, B.; Swahnberg, K. Abuse in Health Care: A Concept Analysis. Scand J Caring Sci 2012, 26, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afulani, P.A.; Sayi, T.S.; Montagu, D. Predictors of Person-Centered Maternity Care: The Role of Socioeconomic Status, Empowerment, and Facility Type. BMC Health Serv Res 2018, 18, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, C.; Wint, K.; Burke, J.; Chang, J.C.; Documet, P.; Kaselitz, E.; Mendez, D. Overlap between Birth Trauma and Mistreatment: A Qualitative Analysis Exploring American Clinician Perspectives on Patient Birth Experiences. Reprod Health 2023, 20, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Mollá, T.M.; Siles, J.; Solano, M. del C. Evitar La Violencia Obstétrica: Motivo Para Decidir El Parto En Casa. MUSAS 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, M.A.; Hunter, E.C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.M.; Souza, J.P.; Vogel, J.P.; Gülmezoglu, A.M. Facilitators and Barriers to Facility-Based Delivery in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Reprod Health 2014, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Roosmalen, J.; van den Akker, T. Continuous and Caring Support Right Now. BJOG 2016, 123, 675–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White Ribbon Alliance Respectful Maternity Care Charter Assets. Available online: https://whiteribbonalliance.org/resources/rmc-charter/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Fontein-Kuipers, Y.; de Groot, R.; van Staa, A. Woman-Centered Care 2.0: Bringing the Concept into Focus. Eur J Midwifery 2018, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, R.S.; Perra, O.; Boyle, B.; Stockdale, J. Perceived Treatment of Respectful Maternity Care among Pregnant Women at Healthcare Facilities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Midwifery 2023, 123, 103714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedam, S.; Stoll, K.; Rubashkin, N.; Martin, K.; Miller-Vedam, Z.; Hayes-Klein, H.; Jolicoeur, G. The Mothers on Respect (MOR) Index: Measuring Quality, Safety, and Human Rights in Childbirth. SSM Popul Health 2017, 3, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro Blazquez, R.; Corchon, S.; Ferrer Ferrandiz, E. Validity of Instruments for Measuring the Satisfaction of a Woman and Her Partner with Care Received during Labour and Childbirth: Systematic Review. Midwifery 2017, 55, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Human Rights. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-rights-and-health (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Aiken, L.R. Three Coefficients for Analyzing the Reliability and Validity of Ratings. Educ Psychol Meas 1985, 45, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gila-Díaz, A.; Carrillo, G.H.; López de Pablo, Á.L.; Arribas, S.M.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Association between Maternal Postpartum Depression, Stress, Optimism, and Breastfeeding Pattern in the First Six Months. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiola, T.; Udofia, O. Psychometric Assessment of the Wagnild and Young’s Resilience Scale in Kano, Nigeria. BMC Res Notes 2011, 4, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surzykiewicz, J.; Konaszewski, K.; Wagnild, G. Polish Version of the Resilience Scale (RS-14): A Validity and Reliability Study in Three Samples. Front Psychol 2018, 9, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.R.; Henry, J.D. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct Validity, Measurement Properties and Normative Data in a Large Non-Clinical Sample. Br J Clin Psychol 2004, 43, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandín, B.; Chorot, P.; Joiner, T.E.; Santed Miguel, A.; Valiente, R.M. Escalas PANAS de Afecto Positivo y Negativo: Validación Factorial y Convergencia Transcultural. Psicothema 1999, 11, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- González, C.; Calleja, N.; Bravo, C.; Meléndez, J. Escala de Creencias Sobre La Maternidad: Construcción y Validación En Mujeres Mexicanas. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación – e Avaliação Psicológica 2019, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado-Mateus, M.; Cuero-Acosta, Y.A.; Guzman-Rincón, A. Evaluation of Psychometric Properties of Perceived Value Applied to Universities. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0284351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.F.; Korevaar, D.A.; Altman, D.G.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Hooft, L.; Irwig, L.; Levine, D.; Reitsma, J.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; et al. STARD 2015 Guidelines for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Wetzel, A. Factor Analysis: A Means for Theory and Instrument Development in Support of Construct Validity. Int J Med Educ 2020, 11, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, E.; Turkheimer, E. Item Selection, Evaluation, and Simple Structure in Personality Data. J Res Pers 2010, 44, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyndt, E.; Onghena, P. The Integration of Work and Learning: Tackling the Complexity with Structural Equation Modelling. In; 2014; pp. 255–291.

- He, S.; Yang, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S. Affective Well-Being of Chinese Urban Postpartum Women: Predictive Effect of Spousal Support and Maternal Role Adaptation. Arch Womens Ment Health 2022, 25, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokuhaki, S.; Dokuhaki, F.; Akbarzadeh, M. The Relationship of Maternal Anxiety, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, and Fatigue with Neonatal Psychological Health upon Childbirth. Contracept Reprod Med 2021, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobe, H.; Kita, S.; Hayashi, M.; Umeshita, K.; Kamibeppu, K. Mediating Effect of Resilience during Pregnancy on the Association between Maternal Trait Anger and Postnatal Depression. Compr Psychiatry 2020, 102, 152190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arghavanian, F.E.; Roudsari, R.L.; Heydari, A.; Bahmani, M.N.D. Pregnant Women’s Experiences of Social Roles: An Ethnophenomenological Study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2020, 25, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcelar, L.; Jonas, E.; Rute, L. Obstetric Violence in Public Maternity Wards of the State of Tocantins. Revista de Estudios Feministas 2018, 26, e43278. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E.P.; Narayan, A.J. Pregnancy as a Period of Risk, Adaptation, and Resilience for Mothers and Infants. Dev Psychopathol 2020, 32, 1625–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasloff, E.; Schytt, E.; Waldenstrom, U. First Time Mothers’ Pregnancy and Birth Experiences Varying by Age. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007, 86, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aasheim, V.; Waldenström, U.; Rasmussen, S.; Espehaug, B.; Schytt, E. Satisfaction with Life during Pregnancy and Early Motherhood in First-Time Mothers of Advanced Age: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quick, A.D.; Tung, I.; Keenan, K.; Hipwell, A.E. Psychological Well-Being across the Perinatal Period: Life Satisfaction and Flourishing in a Longitudinal Study of Black and White American Women. J Happiness Stud 2023, 24, 1283–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrampour, H.; Heaman, M.; Duncan, K.A.; Tough, S. Comparison of Perception of Pregnancy Risk of Nulliparous Women of Advanced Maternal Age and Younger Age. J Midwifery Womens Health 2012, 57, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, C.A.; Boivin, J.; Gibson, F.L.; Hammarberg, K.; Wynter, K.; Saunders, D.; Fisher, J. Age at First Birth, Mode of Conception and Psychological Wellbeing in Pregnancy: Findings from the Parental Age and Transition to Parenthood Australia (PATPA) Study. Human Reproduction 2011, 26, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semasaka, J.P.S.; Krantz, G.; Nzayirambaho, M.; Munyanshongore, C.; Edvardsson, K.; Mogren, I. “Not Taken Seriously”-A Qualitative Interview Study of Postpartum Rwandan Women Who Have Experienced Pregnancy-Related Complications. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0212001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenaroli, V.; Molgora, S.; Dodaro, S.; Svelato, A.; Gesi, L.; Molidoro, G.; Saita, E.; Ragusa, A. The Childbirth Experience: Obstetric and Psychological Predictors in Italian Primiparous Women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, E.; Nourizadeh, R.; Simbar, M.; Rohana, N. Iranian Women’s Experiences of Dealing with the Complexities of an Unplanned Pregnancy: A Qualitative Study. Midwifery 2018, 62, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | Mean | SD | SEM | Median | Q1 | Q3 | Range | Skew | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 3.19 | 1.28 | 0.09 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.37 | 0.42 |

| I2 | 2.96 | 1.41 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.05 | -0.40 |

| I3 | 2.90 | 1.38 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -0.90 | -0.66 |

| I4 | 2.91 | 1.42 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.01 | -0.46 |

| I5 | 2.81 | 1.46 | 0.11 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -0.87 | -0.76 |

| I6 | 2.72 | 1.47 | 0.11 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -0.74 | -0.97 |

| I7 | 3.23 | 1.28 | 0.09 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.50 | 0.78 |

| I9 | 3.06 | 1.37 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.21 | -0.03 |

| I11 | 2.97 | 1.42 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.05 | -0.44 |

| I13 | 3.03 | 1.41 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.12 | -0.27 |

| I15 | 2.57 | 1.69 | 0.12 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -0.58 | -1.43 |

| I16 | 2.63 | 1.67 | 0.12 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -0.63 | -1.37 |

| I17 | 2.48 | 1.74 | 0.13 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -0.50 | -1.55 |

| I22 | 3.48 | 1.04 | 0.08 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -2.02 | 3.05 |

| I23 | 3.48 | 1.01 | 0.07 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -2.02 | 3.19 |

| I27 | 3.06 | 1.48 | 0.11 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.15 | -0.37 |

| I28 | 3.08 | 1.51 | 0.11 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.23 | -0.25 |

| I29 | 3.27 | 1.31 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.51 | 0.71 |

| I31 | 3.01 | 1.45 | 0.11 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.10 | -0.40 |

| I32 | 3.11 | 1.39 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.28 | 0.09 |

| I35 | 2.95 | 1.38 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -1.04 | -0.37 |

| I36 | 2.75 | 1.49 | 0.11 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -0.78 | -0.95 |

| I37 | 2.78 | 1.49 | 0.11 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -0.84 | -0.85 |

| I42 | 3.58 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -2.67 | 6.23 |

| I45 | 3.73 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -3.35 | 11.57 |

| I46 | 3.66 | 0.88 | 0.06 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -3.03 | 8.71 |

| I47 | 3.68 | 0.83 | 0.06 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -3.12 | 9.77 |

| I49 | 3.66 | 0.92 | 0.07 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -3.02 | 8.52 |

| I50 | 3.63 | 0.99 | 0.07 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4 | -2.72 | 6.30 |

| Mean | SD | SEM | Median | Q1 | Q3 | Range | Skew | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 2.97 | 1.09 | 0.08 | 3.22 | 2.56 | 3.89 | 4.00 | -1.12 | 0.30 |

| Factor 2 | 3.66 | 0.66 | 0.05 | 4.00 | 3.50 | 4.00 | 4.00 | -3.26 | 12.22 |

| Factor 3 | 2.68 | 1.41 | 0.10 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | -0.57 | -1.23 |

| Factor 4 | 3.14 | 1.28 | 0.09 | 4.00 | 2.33 | 4.00 | 4.00 | -1.24 | 0.16 |

| Factor 5 | 3.08 | 0.96 | 0.07 | 3.43 | 2.43 | 4.00 | 4.00 | -0.98 | 0.30 |

| FMR | 15.53 | 3.86 | 0.28 | 16.48 | 13.52 | 18.55 | 17.67 | -1.13 | 0.82 |

| Factor 1 std | 23.37 | 8.71 | 0.64 | 25.96 | 20.12 | 30.88 | 31.48 | -1.11 | 0.23 |

| Factor 2 std | 17.76 | 3.33 | 0.24 | 19.40 | 17.48 | 19.40 | 19.40 | -3.28 | 11.91 |

| Factor 3 std | 9.86 | 5.27 | 0.39 | 11.32 | 3.83 | 14.80 | 14.80 | -0.56 | -1.26 |

| Factor 4 std | 8.76 | 3.57 | 0.26 | 11.16 | 6.61 | 11.16 | 11.16 | -1.25 | 0.18 |

| Factor 5 std | 19.34 | 6.06 | 0.45 | 21.52 | 14.76 | 25.12 | 25.12 | -0.97 | 0.28 |

| FMR std | 56.40 | 14.41 | 1.06 | 61.37 | 49.18 | 66.39 | 63.53 | -1.19 | 0.79 |

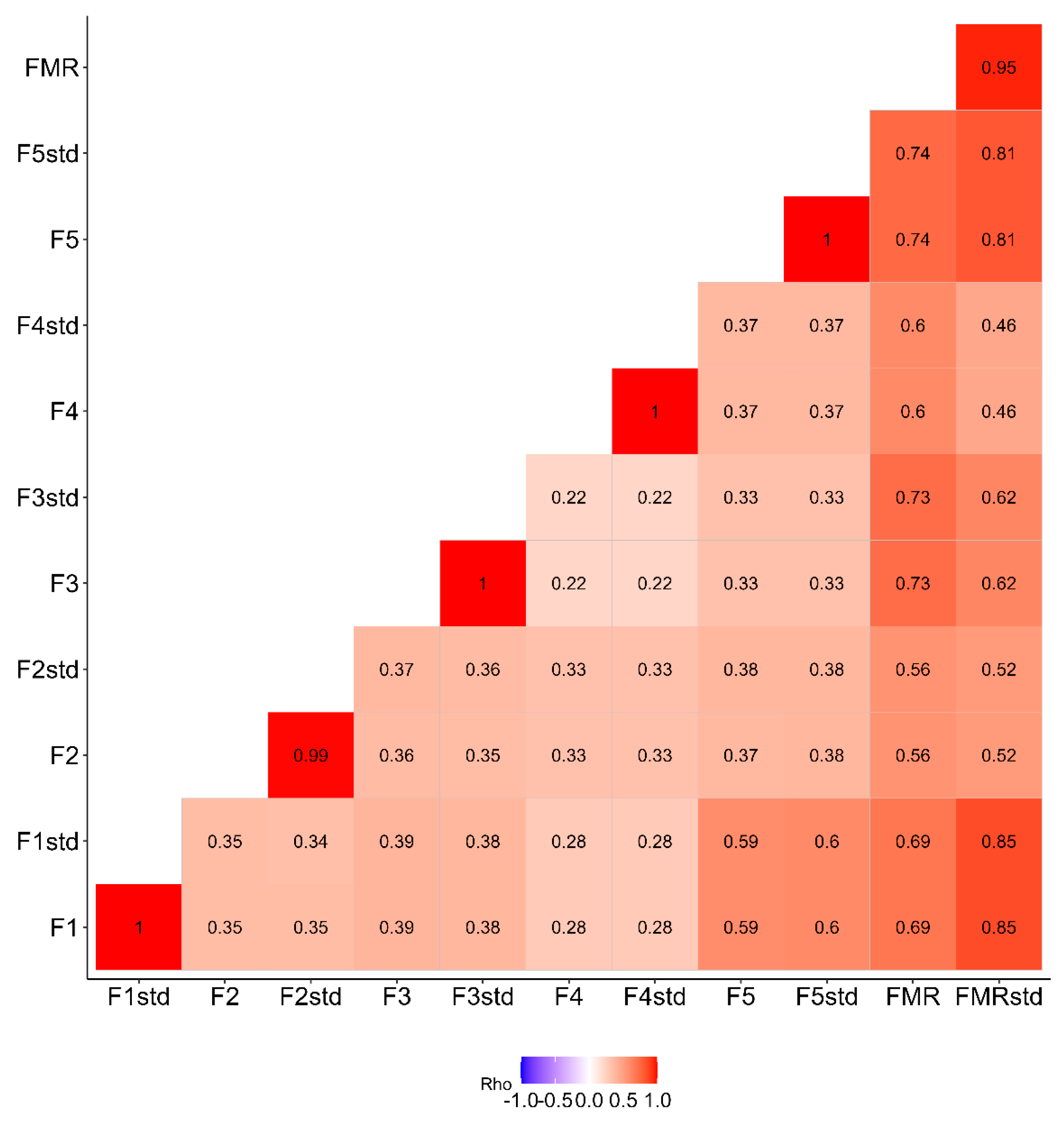

| Factor 1. Information | Factor 2. Privacy | Factor 3. Consent | Factor 4. Support | Factor 5. Participation | FMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVE | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.79 |

| MSV | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.41 | - |

| ASV | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.49 | - |

| Omega | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.97 |

| Alpha | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.93 |

|

Non-intended pregnancy |

Intended pregnancy |

P | Vaginal | C-section | P | |

| Factor 1 | 2.89 [1.56; 3.33] | 3.33 [2.64; 4.00] | 0.048 | 3.33 [2.67; 3.89] | 3.11 [2.44; 3.89] | 0.350 |

| Factor 2 | 3.83 [3.33; 4.00] | 4.00 [3.67; 4.00] | 0.117 | 3.83 [3.50; 4.00] | 4.00 [3.67; 4.00] | 0.113 |

| Factor 3 | 3.00 [1.75; 4.00] | 3.25 [1.00; 4.00] | 0.523 | 3.00 [1.00; 4.00] | 3.00 [2.00; 4.00] | 0.395 |

| Factor 4 | 4.00 [3.00; 4.00] | 4.00 [2.58; 4.00] | 0.408 | 3.00 [1.00; 4.00] | 4.00 [2.42; 4.00] | 0.460 |

| Factor 5 | 3.29 [2.14; 3.71] | 3.50 [2.39; 4.00] | 0.250 | 3.43 [2.43; 4.00] | 3.29 [2.29; 4.00] | 0.961 |

| FMR | 16.0 [12.1; 17.2] | 16.7 [13.8; 18.7] | 0.157 | 16.4 [13.1; 18.5] | 16.7 [13.8; 18.6] | 0.682 |

|

Uncomplicated pregnancy |

Complicated pregnancy |

P |

Uncomplicated postpartum |

Complicated postpartum |

P | |

| Factor 1 | 3.33 [2.67; 4.00] | 3.22 [2.25; 3.78] | 0.340 | 3.33 [2.67; 4.00] | 2.89 [2.11; 3.67] | 0.103 |

| Factor 2 | 4.00 [3.50; 4.00] | 4.00 [3.50; 4.00] | 0.654 | 4.00 [3.50; 4.00] | 3.83 [3.50; 4.00] | 0.238 |

| Factor 3 | 3.00 [1.00; 4.00] | 3.12 [2.00; 4.00] | 0.429 | 3.50 [1.25; 4.00] | 2.25 [1.00; 3.75] | 0.084 |

| Factor 4 | 4.00 [2.33; 4.00] | 4.00 [2.42; 4.00] | 0.774 | 4.00 [2.92; 4.00] | 3.00 [2.00; 4.00] | 0.012 |

| Factor 5 | 3.57 [2.43; 4.00] | 3.07 [2.29; 3.71] | 0.078 | 3.57 [2.43; 4.00] | 2.86 [2.14; 3.57] | 0.002 |

| FMR | 16.6 [13.8; 18.7] | 16.4 [13.3; 18.1] | 0.505 | 16.7 [13.9; 18.7] | 14.7 [12.7; 17.1] | 0.005 |

|

Uncomplicated labor |

Complicated labor |

P | ||||

| Factor 1 | 3.22 [2.50; 4.00] | 3.17 [2.67; 3.67] | 0.539 | |||

| Factor 2 | 4.00 [3.50; 4.00] | 4.00 [3.50; 4.00] | 0.739 | |||

| Factor 3 | 3.00 [1.00; 4.00] | 3.12 [1.44; 4.00] | 0.968 | |||

| Factor 4 | 4.00 [2.33; 4.00] | 4.00 [2.25; 4.00] | 0.605 | |||

| Factor 5 | 3.43 [2.43; 4.00] | 3.07 [2.32; 3.71] | 0.495 | |||

| FMR | 16.6 [13.5; 18.6] | 16.4 [14.1; 18.1] | 0.618 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).