Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

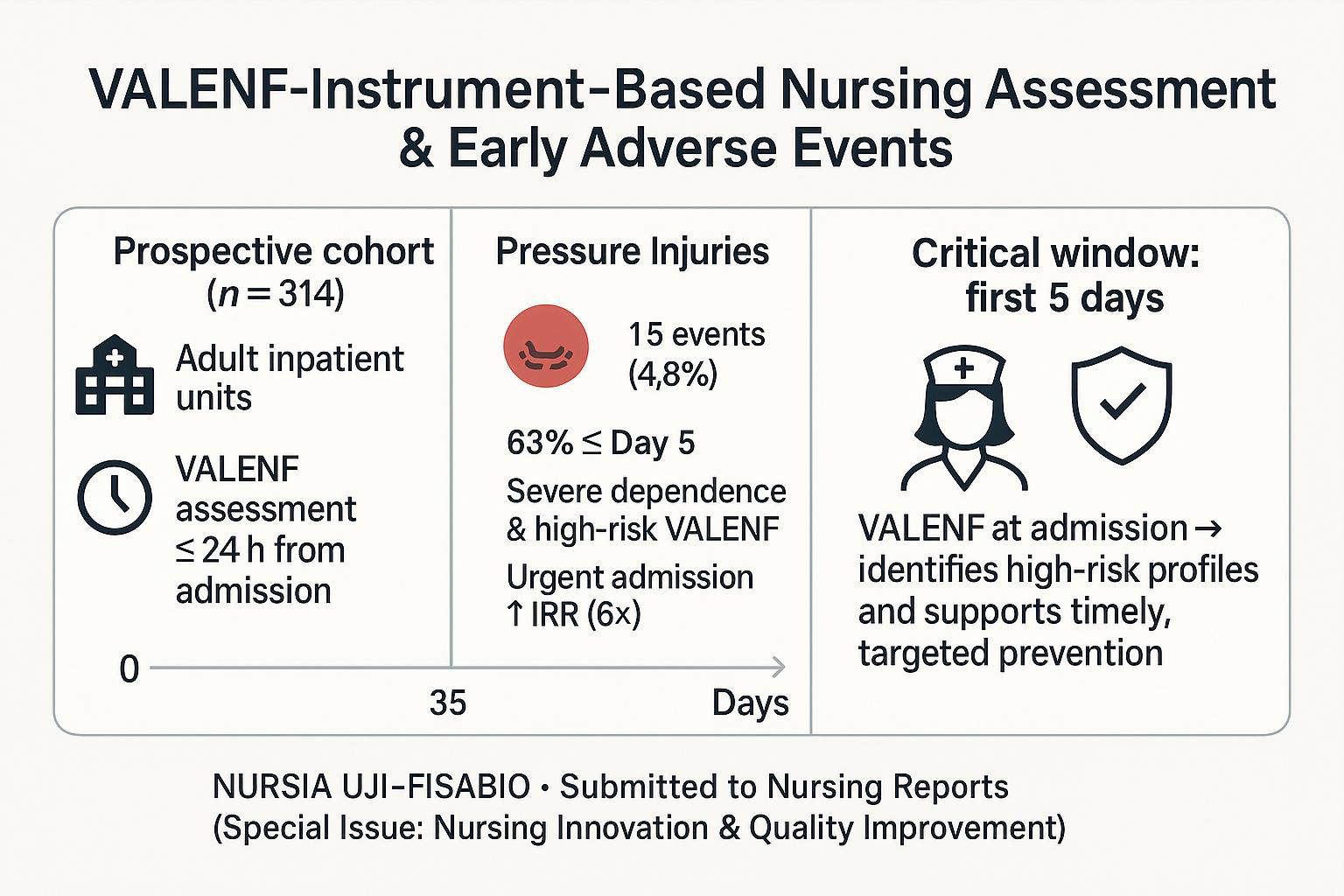

Background/Objectives: Pressure injuries and falls are frequent hospital adverse events. Identifying high-risk periods during hospitalization is essential for guiding effective prevention. In this study, we aimed to estimate the time from hospital admission to the occurrence of pressure injuries and/or falls and analyze its relationship with the nursing assessment at admission. Methods: A longitudinal observational study was conducted with a systematic sample of 314 adult patients admitted between January and May 2024. Survival analysis was performed to describe the temporal distribution of adverse events and compare their occurrence across nursing assessment variables using the log-rank test. Poisson Generalized Linear Models were applied to explore associated factors. Results: Fifteen pressure injuries and four falls were recorded. Overall, 63% of these adverse events occurred within the first five days of hospitalization. Patients with lower functional capacity (log-rank p<0.001) and high-pressure injury risk (log-rank p<0.001) according to the VALENF Instrument were more likely to acquire new pressure injuries. Similarly, fall risk scores (log-rank p=0.037) obtained with the same instrument were associated with falls. Patients classified as high risk for pressure injuries showed a nine-fold higher likelihood of developing new injuries (Wald χ2, p < 0.001), while urgent admission further increased this risk more than six-fold (Wald χ2, p = 0.015). Conclusions: This exploratory study highlights the value of early nursing assessment using the VALENF Instrument in identifying high-risk patients and planning timely, individualized preventive care during hospitalization.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

2.2. Participants and Sample

2.3. Variables

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis Procedures

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Sample

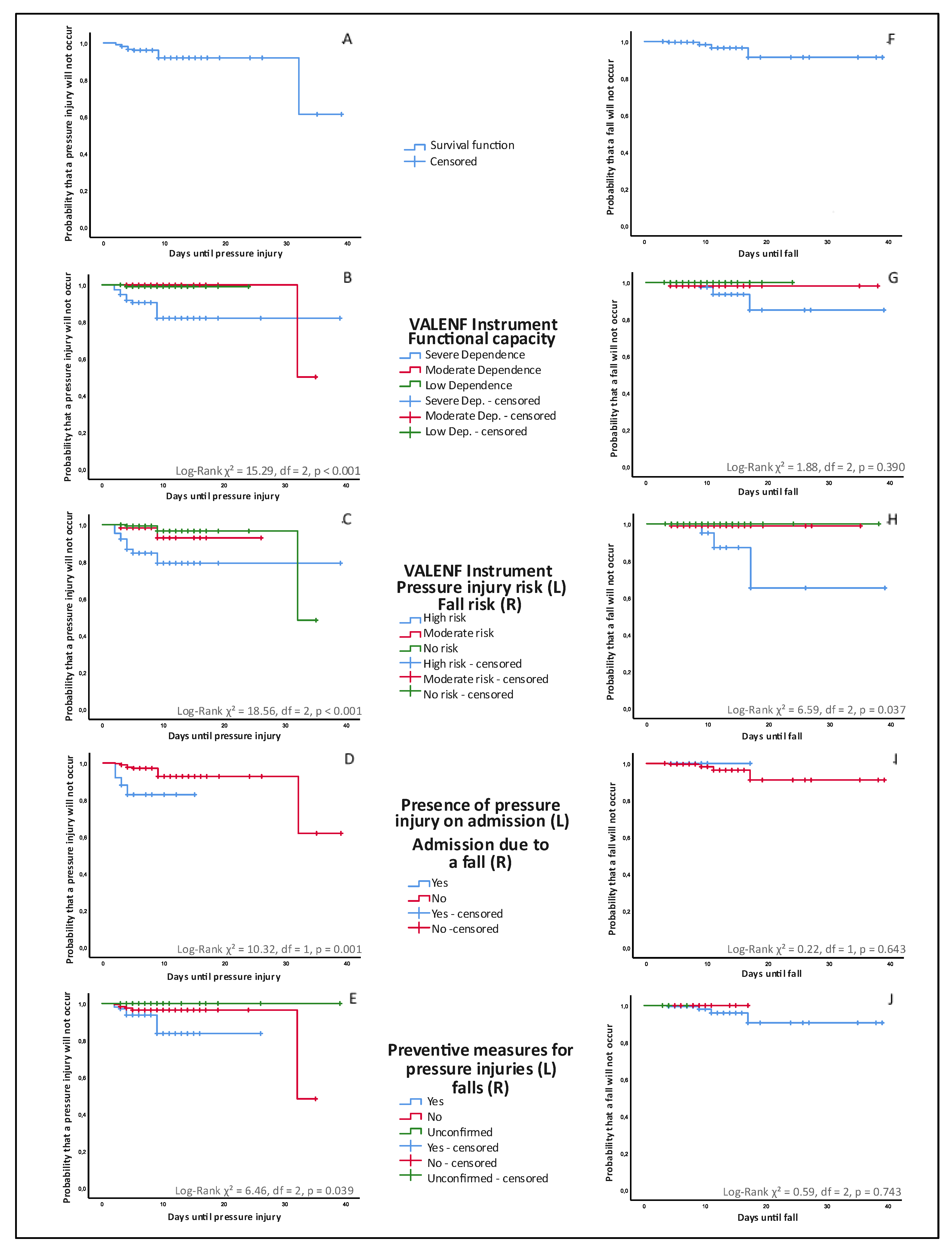

3.2. Bivariate Analysis of Time-to-event outcomes (Pressure Injuries and Falls)

| Table 2. Comparative survival analysis of time-to-event outcomes (pressure injuries and falls) according to the results of the nursing assessment using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test. | |||||||

| Pressure injuries | Events | Censored | |||||

| n1 | %2 | median3 | range (IQR)4 | n1 | %2 | p5 | |

| VALENF Instrument—Functional capacity | <0.001 | ||||||

| Severe dependence | 13 | 0.7 | 4 | 7(5) | 101 | 99.3 | |

| Moderate dependence | 1 | 1.6 | 32 | -(-) | 61 | 98.4 | |

| Low dependence | 1 | 0.7 | 4 | -(-) | 137 | 99.3 | |

| VALENF Instrument—Pressure injury risk | <0.001 | ||||||

| High risk | 10 | 15.6 | 3.5 | 7(2) | 54 | 84.4 | |

| Moderate risk | 2 | 3.4 | 6 | 6(-) | 56 | 96.6 | |

| No risk | 3 | 1.6 | 9 | 28(-) | 189 | 98.4 | |

| Presence of pressure injury on admission | 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 4 | 16 | 2.5 | 2(2) | 21 | 84 | |

| No | 11 | 3.8 | 4 | 30(6) | 278 | 96.2 | |

| Preventive measures for pressure injuries | 0.039 | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | 8.8 | 4 | 7(7) | 93 | 91.2 | |

| No | 6 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 30(9) | 165 | 96.5 | |

| Unconfirmed | - | - | - | - | 41 | 100 | |

| Falls | Events | Censored | |||||

| n1 | %2 | median3 | range (IQR)4 | n1 | %2 | p5 | |

| VALENF Instrument—Functional capacity | 0.390 | ||||||

| Severe dependence | 3 | 2.6 | 11 | 8(-) | 111 | 97.4 | |

| Moderate dependence | 1 | 1.6 | 4 | -(-) | 61 | 98.4 | |

| Low dependence | - | - | - | -(-) | 138 | 100 | |

| VALENF Instrument—Fall risk | 0.037 | ||||||

| High risk | 3 | 4.6 | 11 | 8(-) | 62 | 95.4 | |

| Moderate risk | 1 | 1 | 4 | -(-) | 100 | 99 | |

| No risk | - | - | - | -(-) | 148 | 100 | |

| Admission due to a fall | 0.643 | ||||||

| Yes | - | - | - | - | 25 | 100 | |

| No | 4 | 1.4 | 10 | 13(10) | 285 | 98.6 | |

| Preventive measures for falls | 0.743 | ||||||

| Yes | 4 | 1.6 | 10 | 13(10) | 244 | 98.4 | |

| No | - | - | - | -(-) | 60 | 100 | |

| Unconfirmed | - | - | - | -(-) | 6 | 100 | |

| 1Absolute frequencies; 2relative frequencies; 3estimate of the day on which the events take place (median); 4Min-Max Range (interquartile range); 5log-rank (Mantel–Cox) | |||||||

3.3. Multivariate Analysis of Event Incidence Rates (Pressure Injuries and Falls)

| Table 3. Generalized Linear Models (Poisson regression) for pressure injury incidence according to functional capacity and pressure injury risk (VALENF Instrument). | ||||||

| (LRT χ2; df; p)1 | B2 | (Wald χ2; df; p)3 | IRR (95% CI)4 | |||

| Predictor variable: functional capacity (VALENF Instrument) | ||||||

| Functional Capacity (base model) |

Intercept | (2777.94; 1; <0.001) | -6.49 | (87.79; 1; <0.001) | 0.002 (0.000 - 0.006) | |

| Severe dependence | (10.47; 2; 0.005) | 2.34 | (9.79; 1; 0.002) | 10.38 (2.4 - 44.98) | ||

| Moderate or low dependence | 0 | |||||

| Scale parameter | 1.319 | |||||

| Model summary | AIC = 122.77; Omnibus Chi-square = 11.36 (df = 1, p < 0.001). | |||||

| Functional Capacity adjusted for covariate: pressure injury on admission |

Intercept | (3121.23; 1; 0.001) | -4.350 | (11.55; 1; 0.001) | 0.01 (0.001 - 0.159) | |

| Severe dependence | (9.59; 1; 0.002) | 2.195 | (8.63; 1; 0.003) | 8.98 (2.08 - 38.86) | ||

| Moderate or low dependence | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Pressure injury on admission | (2.27; 1; 0.132) | -1.108 | (3.44; 1; 0.064) | 0.33 (0.102 - 1.066) | ||

| Scale parameter | 1.286 | |||||

| Model summary | AIC = 121.85; Omnibus Chi-square = 13.92 (df = 2, p < 0.001). | |||||

| (LRT χ2; df; p)1 | B2 | (Wald χ2; df; p)3 | IRR (95% CI)4 | |||

| Predictor variable: risk of pressure injury (VALENF Instrument) | ||||||

| Pressure injury risk (base model) |

Intercept | (2509.43; 1; <0.001) | -5.825 | (176.28; 1; <0.001) | 0.003 (0.001 - 0.007) | |

| High risk of pressure injury | (10.76; 1; <0.001) | 2.007 | (13.39; 1; <0.001) | 7.44 (2.54 - 21.81) | ||

| Moderate or risk of pressure injury | 0 | |||||

| Scale parameter | 1.33 | |||||

| Model summary | AIC = 123.466; Omnibus Chi-square = 10.76 (df = 1, p = 0.001) | |||||

| Pressure injury risk adjusted for covariate: Admission type |

Intercept | (2490.4; 1; <0.001) | -7.989 | (46.68; 1; <0.001) | 0.000 (0.000034-0.003) | |

| High risk of pressure injury | (12.5; 1; <0.001) | 2.285 | (13.82; 1; <0.001) | 9.83 (2.95-32.80) | ||

| Moderate or risk of pressure injury | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Urgent admission | (2.69; 1; 0.101) | 1.851 | (5.93; 1; 0.015) | 6.37 (1.44-28.25) | ||

| Scale parameter | 1.330 | |||||

| Model summary | AIC = 121.85; Omnibus Chi-square = 13.46 (df = 2, p = 0.001). | |||||

| 1(Likelihood Ratio Chi-square test; degrees of freedom; p-value); 2B coefficient; 3(Wald Chi-square test; degrees of freedom; p-value); 4incidence rate ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||||

| Table 4. Generalized Linear Models (Poisson regression) for fall incidence according to fall risk (VALENF Instrument). | |||||

| (LRT χ2; df; p)1 | B2 | (Wald χ2; df; p)3 | IRR (95% CI)4 | ||

| Predictor variable: fall risk (VALENF Instrument) | |||||

| Intercept | (2161.95; 1; <0.001) | -1.185 | (385.7; 1; <0.001) | 0.31 (0.27-0.34) | |

| High fall risk | (8.7; 2; 0.013) | -0.213 | (3.69; 1; 0.055) | 0.808 (0.65-1.00) | |

| Moderate fall risk | -0.203 | (4.58; 1; 0.032) | 0.817 (0.68-0.98) | ||

| Low fall risk | 0 | 1 | |||

| Scale parameter | 0.761 | ||||

| Model summary | Omnibus Chi-square = 8.699 (df = 2, p = 0.013). | ||||

|

1(Likelihood Ratio Chi-square test; degrees of freedom; p-value); 2B coefficient; 3(Wald Chi-square test; degrees of freedom; p-value); 4incidence rate ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||||

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shenoy, A. Patient Safety from the Perspective of Quality Management Frameworks: A Review. Patient Saf. Surg. 2021, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-H.; Kim, C.-W.; Lee, S.-Y. Nurse-Perceived Patient Adverse Events and Nursing Practice Environment. J. Prev. Med. Pub. Health 2014, 47, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeleníková, R.; Jarošová, D.; Mynaříková, E.; Plevová, I.; Kachlová, M. Reporting the Adverse Events and Healthcare-Associated Infections in Relation to the Work Environment. Pielegniarstwo XXI Wieku Nurs. 21st Century 2023, 22, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lin, F.; Thalib, L.; Chaboyer, W. Global Prevalence and Incidence of Pressure Injuries in Hospitalised Adult Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 105, 103546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, A.; Price, A.; Harding, K. Pressure Ulcers in Patients Receiving Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, A.L.; Zheng, S.; Gardner, J.W.; Bohn, R.E. When Do Workarounds Help or Hurt Patient Outcomes? The Moderating Role of Operational Failures. J. Oper. Manag. 2020, 66, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padula, W.V. Effectiveness and Value of Prophylactic 5-Layer Foam Sacral Dressings to Prevent Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injuries in Acute Care Hospitals: An Observational Cohort Study. J. Wound. Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2017, 44, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeLaurin, J.H.; Shorr, R.I. Preventing Falls in Hospitalized Patients. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2019, 35, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miake-Lye, I.M.; Hempel, S.; Ganz, D.A.; Shekelle, P.G. Inpatient Fall Prevention Programs as a Patient Safety Strategy: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.-Y.; Fu, M.-L.; Zhao, Q.-H.; Huang, H.-H.; Luo, D.; Xiao, M.-Z. Analysis of Hospitalization Costs Related to Fall Injuries in Elderly Patients. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 1271–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissane, H.; Knowles, J.; Tanzer, J.R.; Laplume, H.; Antosh, H.; Brady, D.; Cullman, J. Relationship Between Mobility and Falls in the Hospital Setting. J. Brown Hosp. Med. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperini, B.; Pelusi, G.; Frascati, A.; Sarti, D.; Dolcini, F.; Espinosa, E.; Prospero, E. Predictors of Adverse Outcomes Using a Multidimensional Nursing Assessment in an Italian Community Hospital. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0249630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, B.M.; Latimer, S.; Walker, R.M.; McInnes, E.; Moore, Z.; Eskes, A.M.; Li, Z.; Schoonhoven, L.; Boorman, R.J.; Chaboyer, W. The Quality and Clinical Applicability of Recommendations in Pressure Injury Guidelines: A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 115, 103857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, J.P.; Peiris, C.L.; Hill, A.-M.; Peterson, S.; Thwaites, C.; Fowler-Davis, S.; Morris, M.E. Hospital Falls Clinical Practice Guidelines: A Global Analysis and Systematic Review. Age Ageing 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, A.M.; Kim, P.; Aribindi, V.; Huang, C.-Y.; Kim, M.-O.; Rangarajan, S.; Schorger, K.; Aldrich, J.M.; Lee, H. Dynamic Risk Prediction for Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injury in Adult Critical Care Patients. Crit. Care Explor. 2021, 3, e0580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.; DeAngelo, B.; Paulson, A.; Suico, S. Temporal Patterns of Patient Falls in an Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility: A Retrospective Analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 104, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, I.; Walker, R.M.; Gillespie, B.M.; Scott, I.; Sugathapala, R.D.U.P.; Chaboyer, W. Risk Factors Predicting Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injury in Adult Patients: An Overview of Reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 150, 104642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Seo, B.-J.; Kim, M.-Y. Time-Varying Hazard of Patient Falls in Hospital: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ven, S.; Steele, M.; Burston, A.; Fulbrook, P.; Lovegrove, J.; Miles, S.; Prince, S. Incidence and Characteristics of Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injuries in Acute Palliative Care Patients: A Four-Year Analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2025; jocn.17829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Surineni, K. Falls in Hospitalized Patients and Preventive Strategies: A Narrative Review. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Open Sci. Educ. Pract. 2025, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Aleixos, D.; Llagostera-Reverter, I.; Castelló-Benavent, X.; Aquilué-Ballarín, M.; Mecho-Montoliu, G.; Cervera-Gasch, Á.; Valero-Chillerón, M.J.; Mena-Tudela, D.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; Martínez-Gonzálbez, R.; et al. Development and Validation of a Meta-Instrument for Nursing Assessment in Adult Hospitalization Units (VALENF Instrument) (Part I). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022 Vol 19 Page 14622 2022, 19, 14622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna-Aleixos, D.; Llagostera-Reverter, I.; Castelló-Benavent, X.; Aquilué-Ballarín, M.; Mecho-Montoliu, G.; Cervera-Gasch, Á.; Valero-Chillerón, M.J.; Mena-Tudela, D.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; Martínez-Gonzálbez, R.; et al. Development and Validation of a Meta-Instrument for the Assessment of Functional Capacity, the Risk of Falls and Pressure Injuries in Adult Hospitalization Units (VALENF Instrument) (Part II). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Chordá, V.M.; Aleixos, D.L.; Reverter, I.L.; Cervera-Gash, À.; Machancoses, F.H.; Moreno-Casbas, M.T.; Arasil, P.F.; Chillerón, M.J.V. Diagnostic Accuracy Study of the VALENF Instrument in Hospitalization Units for Adults: A Study Protocol. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancorbo-Hidalgo, P.; García-Fernández, F.; Pérez-López, C.; Agreda, J.J.S. Prevalence of Pressure Injuries and Other Dependence-Related Skin Lesions in Adult Patients Admitted to Spanish Hospitals: The Fifth National Study in 2017. Gerokomos 2019, 30, 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- CIE-10-ES: Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades : 10 a Revisión; 5a edición: enero 2024. ; Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo: Madrid, 2024; ISBN 978-84-340-2953-8.

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.; Sundararajan, V.; Halfon, P.; Fong, A.; Burnand, B.; Luthi, J.-C.; Saunders, L.D.; Beck, C.A.; Feasby, T.E.; Ghali, W.A. Coding Algorithms for Defining Comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 Administrative Data: Med. Care 2005, 43, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mickey, R.M.; Greenland, S. The Impact of Confounder Selection Criteria on Effect Estimation. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1989, 129, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.H.; Burstyn, I. Identification of Confounder in Epidemiologic Data Contaminated by Measurement Error in Covariates. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INCLASNS:Key Indicators National Health System [Internet]. Madrid:Ministry of Health; 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 20]. Available from: https://inclasns.sanidad.gob.es/main.html.

- Sardo, P.M.G.; Teixeira, J.P.F.; Machado, A.M.S.F.; Oliveira, B.F.; Alves, I.M. A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Incidence of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries in Hospital Emergency Services. J. Tissue Viability 2023, 32, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, B.; Bechenati, D.; Bethel, H.M.; Cho, S.; Rajjoub, N.S.; Murad, S.T.; Kabbara Allababidi, A.; Rajjo, T.I.; Yousufuddin, M. A Systematic Review of Length of Stay Linked to Hospital-Acquired Falls, Pressure Ulcers, Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infections, and Surgical Site Infections. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2025, 9, 100607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyd, C.; Markland, A.D.; Zhang, Y.; Fowler, M.; Harper, S.; Wright, N.C.; Carter, C.S.; Buford, T.W.; Smith, C.H.; Kennedy, R.; et al. Prevalence of Hospital-Associated Disability in Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 455–461.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córcoles-Jiménez, M.P.; Ruiz-García, M.V.; Saiz-Vinuesa, M.D.; Muñoz-Mansilla, E.; Herreros-Sáez, L.; Fernández-Pallarés, P.; Calero-Yáñez, F.; Muñoz-Serrano, M.T. Deterioro funcional asociado a la hospitalización en pacientes mayores de 65 años. Enferm. Clínica 2016, 26, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, C.; Sherrington, C.; Tilden, W.; Jennings, M.; Richards, B.; Hill, A.-M.; Fairbrother, G.; Ling, F.; Naganathan, V.; Haynes, A. Considerations across Multiple Stakeholder Groups When Implementing Fall Prevention Programs in the Acute Hospital Setting: A Qualitative Study. Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, I.; Walker, R.; Gillespie, B. Pressure Injury Prevention in the Perioperative Setting: An Integrative Review. J. Perioper. Nurs. 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Wilson, V.; Tuqiri, K. The Pressure Injury Prevalence and Practice Improvements ( PIPPI ) Study: A Multiple Methods Evaluation of Pressure Injury Prevention Practices in an Acute-care Hospital. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e70050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera-Salmerón, E.; Mota-Romero, E.; Romero-Béjar, J.L.; Dominguez-Nogueira, C.; Gómez-Pozo, B. Pressure Ulcers Risk Assessment According to Nursing Criteria. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinelli, J.; Zuniga, S.; Kipnis, P.; Kawar, L.N.; Liu, V.; Escobar, G.J. Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injury: Risk-Adjusted Comparisons in an Integrated Healthcare Delivery System. Nurs. Res. 2018, 67, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaul, E.; Barron, J.; Rosenzweig, J.P.; Menczel, J. An Overview of Co-Morbidities and the Development of Pressure Ulcers among Older Adults. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.-L.; Widdel, M.; Kirchhoff, J.; Sellin, J.; Jelali, M.; Geiser, F.; Mücke, M.; Conrad, R. Risk Factors for Pressure Injuries in Adult Patients: A Narrative Synthesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulbrook, P.; Lovegrove, J.; Ven, S.; Miles, S.J. Pressure Injury Risk Assessment and Prescription of Preventative Interventions Using a Structured Tool versus Clinical Judgement: An Interrater Agreement Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 80, 4523–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisberg, A.; Shadmi, E.; Gur-Yaish, N.; Tonkikh, O.; Sinoff, G. Hospital-Associated Functional Decline: The Role of Hospitalization Processes Beyond Individual Risk Factors. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covinsky, K.E.; Pierluissi, E.; Johnston, C.B. Hospitalization-Associated Disability: “She Was Probably Able to Ambulate, but I’m Not Sure. ” JAMA 2011, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervo-Heikkinen, T.A.; Heikkilä, A.; Koivunen, M.; Kortteisto, T.; Peltokoski, J.; Salmela, S.; Sankelo, M.; Ylitörmänen, T.S.; Junttila, K. Pressure Injury Prevalence and Incidence in Acute Inpatient Care and Related Risk Factors: A Cross-sectional National Study. Int. Wound J. 2022, 19, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.W.; Mallery, K.; Rockwood, K.; Theou, O. Impact of Hospitalization on Patients Ability to Perform Basic Activities of Daily Living. Can. Geriatr. J. 2023, 26, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cruz, M.; Parra-Anguita, L.; López-Martínez, C.; Moreno-Cámara, S.; del-Pino-Casado, R. Burden and Anxiety in Family Caregivers in the Hospital That Debut in Caregiving. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roderman, N.; Wilcox, S.; Beal, A. Effectively Addressing Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injuries With a Multidisciplinary Approach. HCA Healthc. J. Med. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-González, E.; Mayordomo-Cava, J.; Vidán, M.T.; Valadés-Malagón, M.I.; Serra-Rexach, J.A.; Ortiz-Alonso, J. Functional Trajectories Associated with Acute Illness and Hospitalization in Oldest Old Patients: Impact on Mortality. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 937115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovegrove, J.; Fulbrook, P.; Miles, S. Prescription of Pressure Injury Preventative Interventions Following Risk Assessment: An Exploratory, Descriptive Study. Int. Wound J. 2018, 15, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, C. “The Road to Hell Is Paved with Good Intentions” — the Cognitive Bias of Immobility in in-Patients at Risk of Falling. Rev. Assoc. Médica Bras. 2023, 69, 365–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growdon, M.E.; Shorr, R.I.; Inouye, S.K. The Tension Between Promoting Mobility and Preventing Falls in the Hospital. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabkowski, E.; Cooper, S.; Duncan, J.R.; Missen, K. Adult Inpatients’ Perceptions of Their Fall Risk: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solares, N.P.; Calero, P.; Connelly, C.D. Patient Perception of Fall Risk and Fall Risk Screening Scores. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2023, 38, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, S.; Park, E.; Ku, S.; Kim, S.; Yu, W.; Jeong, E.; Park, S.; Park, Y.; Kim, S.R. Congruency and Its Related Factors between Patients’ Fall Risk Perception and Nurses’ Fall Risk Assessment in Acute Care Hospitals. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2024, 56, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hedrera, F.J.; Noguera-Quijada, C.; Sanz-Márquez, S.; Pérez-Fernández, E.; Acevedo-García, M.; Domínguez-Rincón, R.; Martínez-Simón, J.J.; González-Piñero, B.; Carmona-Monge, F.J.; Camacho-Pastor, J.L. Incidencia y características de las caídas de pacientes hospitalizados: estudio de cohortes. Enferm. Clínica 2021, 31, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymkew, H.; Taylor, B.; Vyers, K.; Costantinou, E.; Arroyo, C.; Schallom, M. Original Research: Patient Perception of Fall Risk in the Acute Care Setting. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2023, 123, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heikkilä, A.; Lehtonen, L.; Junttila, K. Consequences of Inpatient Falls in Acute Care: A Retrospective Register Study. J. Patient Saf. 2024, 20, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. (Lucy); Kim, H. Older Adult Inpatient Falls in Acute Care Hospitals: Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Environmental Factors. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2015, 41, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.W.; Levine, D.M.; Salmasian, H.; Syrowatka, A.; Shahian, D.M.; Lipsitz, S.; Zebrowski, J.P.; Myers, L.C.; Logan, M.S.; Roy, C.G.; et al. The Safety of Inpatient Health Care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Global | Pressure injuries | Falls | |||

| %(n)1 | CI (n)2 | ID3 | CI (n)2 | ID3 | |

| 100 (314) | 4.8 (15) | 7 | 1.3 (4) | 2 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 51 (160) | 3.1 (5) | 5 | 1.9 (3) | 3 |

| Female | 49 (154) | 6.5 (10) | 4 | 0.6 (1) | 1 |

| Age | |||||

| 19-51 years | 13.4 (42) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| 52-74 years | 36.9 (116) | 4.3 (5) | 6 | 1.7 (2) | 2 |

| 75-98 years | 49.7 (156) | 6.4 (10) | 10 | 1.3 (2) | 2 |

| Process type | |||||

| Medical | 83.4 (262) | 4.2 (11) | 6 | 1.1 (3) | 2 |

| Surgical | 16.6 (52) | 7.7 (4) | 12 | 1.9 (1) | 3 |

| Admission type | |||||

| Scheduled | 6.4 (20) | 10 (2) | 17 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Emergency | 93.6 (294) | 4.4 (13) | 6 | 1.3 (4) | 2 |

| Hospitalization unit | |||||

| Traumatology | 24.2 (76) | 5.3 (4) | 8 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Surgery/Gynecology | 16.6 (52) | 5.8 (3) | 8 | 5.8 (3) | 8 |

| Cardio/Gastroenterology | 9.9 (31) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Neuro/Pulmonology | 23.6 (74) | 6.8 (5) | 9 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| General surgery | 17.5 (55) | 3.6 (2) | 6 | 1.8 (1) | 3 |

| Internal medicine | 8.3 (26) | 3.8 (1) | 5 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Barthel index categories at admission | |||||

| Slight (80-100) | 47.8 (150) | 0.7 (1) | 1 | (0) | 0 |

| Moderate (35-75) | 26.4 (83) | 3.6 (3) | 5 | 2.4 (2) | 3 |

| Severe (0-30) | 25,8 (81) | 13.6 (11) | 19 | 2.5 (2) | 3 |

| Charlson Index | |||||

| Absence (0-1) | 21.7 (68) | 2.9 (2) | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Low (2) | 8.6 (27) | 3.7 (1) | 6 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| High (≥3) | 69.7 (219) | 5.5 (12) | 8 | 1.8 (4) | 2 |

| Pressure injury on admission | |||||

| 1.0 (3) | 33.3 (1) | 91 | 0 (0) | 0 | |

| Admission motivated by fall | |||||

| 0.3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 | |

| Preventive measures for pressure injuries | |||||

| Applied | 32.5 (102) | 8.82 (9) | 13 | ||

| Not Applied | 54.5 (171) | 3.51 (6) | 5 | ||

| Unconfirmed | 13.1 (41) | 0 (0) | 0 | ||

| Preventive measures for falls | |||||

| Applied | 79 (248) | 1.61 (4) | 2 | ||

| Not Applied | 19.1 (60) | 0 (0) | 0 | ||

| Unconfirmed | 1.9 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 | ||

| 1Percentage by column (sample); 2percentage cumulative incidence (sample); 3incidence density per 1000 person-days | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).