Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

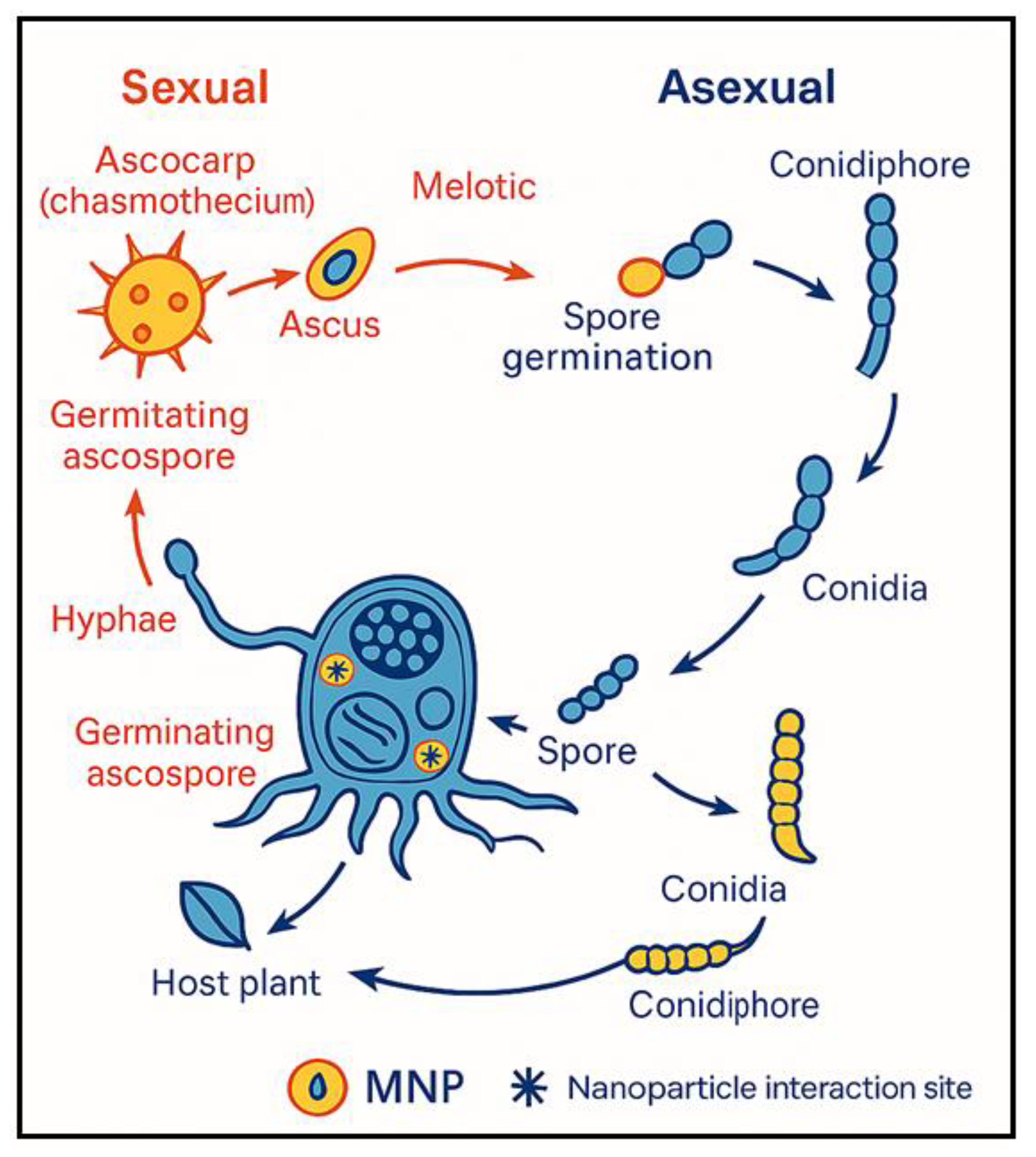

2. Powdery Mildew: Biology and Impact

3. Nanoparticles and Nanosuspensions Applications on Powdery Mildew

3.1. Metallic Nanoparticles (MNPs) Effect on Powdery Mildew

| Nanoparticle Type |

Crop | Size (nm) | Concentration | Synthesis Method | Application Method | Effectiveness | Additional Benefits | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | Eggplant | 7–25 | 10–100 ppm | CS | Foliar | Effective in reducing powdery mildew | SEM: Mycelial and spore deformation | [35] |

| Ag | Beans | ~25 | 10–100 ppm | CS and GS | Foliar | Effective against powdery mildew and Botrytis cinerea | ↓ Disease incidence, ↑ yield potential | [35] |

| Ag | Melons | 7–25 | 10–100 ppm | CS | Foliar | 100 ppm: 20% disease incidence | SEM: Spore deformation, ↑ efficacy pre-infection | [35] |

| Ag | Radish | 7–25 | 10–100 ppm | CS | Foliar | Effective in reducing powdery mildew (extrapolated) | SEM: Spore deformation, safe for leafy crops | [35] |

| Ag | cucumber & pumpkin | ~10–50 | 100 ppm | GS | Foliar | Highest inhibition rate | Damages fungal hyphae and conidia; SEM confirmed effects | [35] |

| Ag | Grapevine | ~20–23 | ND | GS | Foliar | Improved control of E. necator | Superior leaf adhesion, enhanced uptake, prolonged protection vs. copper formulations | [39] |

| Ag | Grapevine | ~17 | crude | GS | Foliar | Protective effect against Uncinula necator | enhanced sugar, starch, water content; increased shoot length and grape yield | [40] |

| Cu | Squash | ~40–60 | ~300 mg·L⁻¹ | CS | Foliar | Highest among tested | Outperformed biological and botanical alternatives; consistent disease suppression | [43] |

| ZnO | Tomato, Pepper | ~40 | 50–250 mg·L⁻¹ | CS | Foliar & Soil | Significant reduction in powdery mildew | Enhanced chlorophyll, lycopene, β-carotene, sugar content; reduced oxidative stress (MDA) | [44] |

| ZnO | Pepper | 79.5 | 100, 150, 200 mg·L⁻¹ | CS | Foliar | Significant reduction in disease severity | Increased chlorophyll; no substantial cytotoxicity (mitotic index unaffected); alternative to penconazole | [45] |

| MgO | Pepper | 53 | 100, 150, 200 mg·L⁻¹ |

CS |

Foliar | Significant reduction in disease severity | Increased chlorophyll; no substantial cytotoxicity (mitotic index unaffected); alternative to penconazole | [45] |

| Fe₃O₄ | Lettuce | ~20–50 | ~200 mg·L⁻¹ | CS | Foliar | Significant reduction in disease severity | Increased chlorophyll, carotene, phenolics, protein; elevated CAT and PPO enzyme activity | [46] |

| Se | Melons | ~50–100 | 25–75 mg·L⁻¹ | CS | Foliar | ~21–45% reduction | Enhances antioxidant enzymes; alters polyamine, phenylpropanoid, and hormone pathways | [47] |

| Se | Various crops | ~50–100 | 25–100 mg·L⁻¹ | GS | Foliar | High antifungal activity; effective against resistant strains | Antioxidant, biocompatible, low toxicity; safe fungicide alternative | [48] |

| Ag, ZnO, TiO₂ | Tomato | 10–100 | Varies | GS | Foliar | Effective against fungal & insect pests | ↑ Photosynthesis | [49] |

| CuO and ZnO | Mustard | ~50–80 | 100–300 mg·L⁻¹ | GS | Foliar | Promising antifungal activity | Eco-friendly alternative to fungicides | [50] |

| TiO₂ | Spinach | ~20 | 50–100 mg·L⁻¹ | Sol-gel/GS | Foliar | ↑ Photosynthesis, ↓ fungal stress | ↑ Biomass, ↑ Chlorophyll content | [50] |

| CuO | Lettuce | 230–400 | 100 mg·L⁻¹ | GS | Foliar | ↓ Fungal colonization | ↑ Leaf health, ↓ oil evaporation | [50] |

| Ag and ZnO | Grapes | 10–50 | 50–200 ppm | GS | Foliar | Effective against Erysiphe necator | ↑ Fruit quality, ↓ chemical residues | [50] |

| ZnO and CuO | Oranges | 20–80 | 100–300 ppm | GS | Foliar | Antifungal & antibacterial | ↑ Shelf life, ↑ Disease resistance | [50] |

| ZnO | Beetroot (Sugar beet) | — | 10, 50, 100 ppm | Engineered | Foliar | ↓ Disease severity, ↑ chlorophyll, ↑ PPO & POD | Induced resistance via ROS and phenolics | [51] |

| Ag | Cucurbits | ~10–50 | 25–100 mg·L⁻¹ | CS/GS | Foliar | Up to 90% reduction | Minimal phytotoxicity; eco-friendly; strong antifungal activity | [52] |

3.2. Non-Metallic Nanoparticles (NMNPs) Effect on Powdery Mildew

3.3. Nano-Encapsulated Fungicides and Essential Oils

| Nanoparticle | Crop Name | Size (nm) | Concentration / Dose | Synthesis Method | Application Method | Effectiveness | Additional Benefits | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan + CSEO | Cucumber | 300 | 1–3 mg·mL⁻¹ | Ionic gelation + encapsulation | Foliar | Significant reduction in powdery mildew severity | Increased chlorophyll, phenolics, flavonoids, defense enzyme activity, and gene expression | [16] |

| Nutragreen® nanoscale carrier | Hop | NS | 30% v/v | CS | Foliar | ~70–90% reduction in powdery mildew severity | Reduced pesticide use; improved cone yield and α-acid content; enhanced leaf and cone protection | [36] |

| Sulfur | Okra | 50–90 | 1000 ppm | Liquid synthesis | Foliar | 100% inhibition of conidial germination | Disrupted cleistothecia, reduced phytotoxicity | [56] |

| Sulfur | Apple | 50–90 | 1000 ppm | Liquid synthesis | Foliar | Effective at lower doses, avoids phytotoxicity | Safer than conventional sulfur for fruit crops | [56] |

| Sulfur | Mango | 85 | 100ppm | CS | Foliar | 14.6% reduction in powdery mildew | 342% increase in productivity; improved fruit quality (TSS, vitamin C); enhanced POD & PPO enzyme activity | [56] |

| Sulfur | Cucumber | 12.2–23.5 | 500 mg·L⁻¹ | CS | Foliar | 60.9% reduction in powdery mildew | Matched azoxystrobin (74%) and diniconazole (68.8%) in efficacy; highest fruit yield and quality | [57] |

| Chitosan oligomers + Streptomyces metabolites / hydrolyzed gluten | Grapevine | <2 kDa | ~40 mL | Enzymatic hydrolysis / fermentation | Foliar & root | Comparable to conventional fungicides | Effective against Erysiphe necator; biostimulant effects; reduced overwintering inoculum | [60] |

| Chitosan NPs + SSEO | Cucumber | ~116.2 | 400 µg·mL⁻¹ | Ionic gelation + encapsulation | Foliar | Significant reduction in powdery mildew severity | High encapsulation efficiency; spherical morphology; elevated phenolics, flavonoids, POD, PPO, PAL activity | [61] |

| Thyme oil nanoemulsion | Lettuce | ~83 | 10% (v/v) | Ultrasonic emulsification | Foliar | Maintains beneficial microbes; stable for >3 months; effective even when diluted | [62] | |

| Chitosan | Cucumber | 150–250 | 0.1–0.2% (w/v) | Ionic gelation | Foliar | ~70% disease reduction | Induces SAR; enhances chlorophyll and defense enzymes | [74] |

| Chitosan | Tomato | 20-100 | 0.1–1%(w/v) | Ionic gelation | Foliar | Effective against powdery mildew at early stage | Induces systemic resistance, enhances growth | [75] |

| Chitosan | Cucumber | 20-100 | 0.1–1%(w/v) | Emulsion cross-linking | Foliar | Effective against fungal pathogens including powdery mildew | Improved resistance, growth promotion | [75] |

| SiO₂- | Grape | 50–80 | 50–100 mg L⁻¹ | Sol–gel | Foliar | 85–90% reduction | Strengthens epidermis; Si-mediated resistance | [76] |

| SiO₂ | Cucumber | 40–60 | 50 mg L⁻¹ | Sol–gel | Foliar | 80–90% mildew reduction | Reinforces cuticle; nontoxic | [76] |

| SiO₂ | Watermelon | Mesoporous SNPs | NS | Modified Stöber method | Root dip | 40% reduction in disease severity | Downregulation of stress genes (CSD1, PAO, PPO, RAN1) | [77] |

| SiO₂ | Cucumber | 10-100 | NS | Sol–gel, GS | Foliar | High efficacy | Improved photosynthesis, enzyme activity, stomatal conductance | [77] |

| SiO₂ | Cucumber | 10-100 | 1.7–56 mM | Sol–gel | Foliar | Up to 87% reduction in powdery mildew | Improved resistance, structural strength | [78] |

| Silica–alginate nanocomposite | Pumpkin | 70–150 | 25–75 mg L⁻¹ | Sol–gel + biopolymer | Foliar | 80% mildew control | Reinforces epidermis; water balance | [79] |

| Silica–chitosan | Spinach | 80–150 | 0.1% (w/v) | Sol–gel + ionic gelation | Foliar | 65% infection reduction | Improves leaf turgidity; safe | [79] |

| Silica–pectin | Apple | 40–90 | 50 mg L⁻¹ | Sol–gel hybridization | Foliar | 75% reduction | Biodegradable; strengthens cuticle | [80] |

| Silica–pectin | Peach | 40–100 | 50 mg L⁻¹ | Sol–gel | Foliar | 78% mildew suppression | Strengthens fruit epidermis | [80] |

| Carbon nanotubes | Tomato | 10–40 | 10–25 mg L⁻¹ | CS | Foliar | ~55% mildew reduction | Boosts antioxidants | [81] |

| Graphene oxide nanosheets (GO) | Cucumber | 30–200 | 25–50 mg L⁻¹ | Modified Hummers | Foliar | ~60% reduction | Activates enzymes; nutrient uptake | [82] |

| Nano-encapsulated lemongrass EO (Alginate) | Strawberry | 150–300 | 2–4 mg mL⁻¹ | Emulsion crosslinking | Foliar | ~85% infection reduction | Antioxidant; flavor-safe | [83] |

| Nanobubble water | Papaya | 70–130 | 5×10⁸ to 5×10⁹ bubbles/mL | Nanobubble generator | Foliar | Effective against powdery mildew (patented method) | Non-toxic, enhances root zone health | [84] |

4. Mechanisms of Action Against Powdery Mildew

4.1. Direct Antifungal Effects

4.2. Indirect Effects: Induced Resistance and Gene Regulation

4.3. Synergy with Conventional Fungicides

5. Challenges and Limitations

6. Future Perspectives and Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghalehgolabbehbahani, A.; Zinati, G.; Hamido, S.; Bhusal, N.; Dhakal, M. , Afshar, R. K.; Contina, J. B.; Caetani, R.; Smith, A.; Panday, D. Integrated control of powdery mildew using UV light exposure and OMRI-certified fungicide for greenhouse organic lettuce production. Horticulturae, 2025; 11, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A. U.; Davik, J.; Karisto, P.; Astakhova, T.; Sønsteby, A. A major QTL region associated with powdery mildew resistance in leaves and fruits of the reconstructed garden strawberry. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2025; 138, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsalem, L.; Freeman, S.; Rav-David, D.; Nitzani, Y.; Sztejnberg, A.; Pertot, I.; Elad, Y. Effect of climatic factors on powdery mildew caused by Sphaerotheca macularis f. sp. fragariae on strawberry. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2006, 114, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, M.T.; Staniszewska, H.; Shishko, N. Fungicide Sensitivity of Sphaerotheca fuliginea populations in the United States. Plant Dis, 1996; 80, 697–703. [Google Scholar]

- Saharan, G. S.; Mehta, N.; Saharan, M. S. (2019). Powdery Mildew Disease of Crucifers: Biology, Ecology and Disease Management (Chapter 3: The Pathogen). Springer Nature Singapore.

- Nie, J.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, W.; Pan, J. Genetics, resistance mechanism, and breeding of powdery mildew resistance in cucumbers (Cucumis sativus L.). Horticultural Plant Journal, 2023; 9, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Fan, C.; Wu, H.; Sun, L.; Cao, C. Preparation of Trichoderma asperellum microcapsules and biocontrol of cucumber powdery mildew. Microbiology Spectrum, 2023; 11, 9e05084-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elagamey, E.; Abdellatef, M.A.; Haridy, M.S.; Abd El-aziz, E.S.A. Evaluation of natural products and chemical compounds to improve the control strategy against cucumber powdery mildew, Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 165, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyarosy, A. C.; Malkin, R. Photosynthetic impairment in plants infected with powdery mildew. Physiological Plant Pathology, 1978; 13, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Jaenisch, J.; Xue, H.; Schläpfer, J.; McGarrigle, E.R.; Louie, K.; Northen, T.R.; Wildermuth, M.C. Powdery mildew infection induces a non-canonical route to storage lipid formation at the expense of host thylakoid lipids to fuel its spore production. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, G.C.; Fraser, G.A. The influence of powdery mildew infection on photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence, leaf chlorophyll and carotenoid content of three woody species. Arboric. J. 2002, 26(4):333–347.

- Vielba-Fernández, A.; Polonio, Á.; Ruiz-Jiménez, L.; de Vicente, A.; Pérez-García, A.; Fernández-Ortuño, D. Fungicide resistance in powdery mildew fungi. Microorganisms, 2020; 8, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Pu, X.; Du, W. The effect of powdery mildew on the cell structure and cell wall composition of red clover. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2024, 171, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Du, J.; Chen, H.; Gong, S.; Jin, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, T.; Fu, B.; Molnár, I.; Holušová, K.; Said, M.; Xing, L.; Kong, L.; Doležel, J.; Li, G.; Wu, J.; Chen, P.; Cao, A.; Zhang, R. Wheat Pm55 alleles exhibit distinct interactions with an inhibitor to cause different powdery mildew resistance. Nature Communications, 2024; 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Yan, Y.; Wang, W.; Gebretsadik, K.; Qi, X.; Xu, Q.; Chen, X. Comparative proteomic analysis of cucumber powdery mildew resistance between a single-segment substitution line and its recurrent parent. Hortic Res 2019, 6:115.

- Soleimani, H.; Reza Mostowfizadeh-Ghalamfarsa, R.; Zarei, A. Chitosan nanoparticle encapsulation of celery seed essential oil: Antifungal activity and defense mechanisms against cucumber powdery mildew. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications, 2024, 8, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, M. Z.; Kiss, L.; Pintye, A. Environmental factors influencing the efficacy of Ampelomyces quisqualis as a biocontrol agent against powdery mildew. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2023, 14, 1176542. [Google Scholar]

- Gilardi, G.; Gullino, M. L.; Garibaldi, A. Efficacy of biological and chemical products against powdery mildew on zucchini. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 2008; 115, 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- MSU Extension. (2023). Integrated pest management (IPM) for powdery mildew in horticultural crops. Michigan State University (MSU) Extension. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/integrated-pest-management-ipm-for-powdery-mildew.

- Lebeda, A.; Mieslerová, B. Taxonomy, distribution and biology of lettuce powdery mildew (Golovinomyces cichoracearum sensu stricto). Plant Pathol, 2011; 60, 400-15. [Google Scholar]

- Aldeeb, M.M.E.; Wilar, G.; Suhandi, C.; Elamin, K.M.; Wathoni, N. Nanosuspension-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Topical Applications, International Journal of Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 825-844. [CrossRef]

- Parada, J.; Tortella, G.; Seabra, A. B.; Fincheira, P.; Rubilar, O. Potential antifungal effect of copper oxide nanoparticles combined with fungicides against Botrytis cinerea and Fusarium oxysporum. Antibiotics, 2024,13(3), 215.

- Sangeeta, M. K.; Gunagambhire, V. M.T.; Bhat, M. P.; Nagaraja, S. K.; Gunagambhire, P. V.; Kumar, R. S.; Mahalingam, S. M. In-vitro evaluation of Talaromyces islandicus mediated zinc oxide nanoparticles for antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, bio-pesticidal and seed growth promoting activities. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 2024, 15, 1901–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, A.; Tripodi, F.; Armanni, A.; Barbieri, L.; Colombo, A.; Fumagalli, S.; Moukham, H.; Tomaino, G.; Kukushkina, E.; Lorenzi, R.; Marchesi, L.; Monguzzi, A.; Paleari, A.; Ronchi, A.; Secchi, V.; Sironi, L.; Colombo, M. (2024). Advancements in nanosensors for detecting pathogens in healthcare environments. Environmental Science: Nano, 2024, 11(12), 4449–4474. [CrossRef]

- Ly, P-D.; Ly, K-N.; Phan, H-L.; Nguyen, HHT.; Duong, V-A.; Nguyen, H.V. Recent advances in surface decoration of nanoparticles in drug delivery. Front. Nanotechnol. 2024, 6:1456939.

- Xu, Y.; Du, S.; Li, M.; Tan, H.; Sohail, X.; Liu, X.; Qi, X.; Yang, X.; Chen, A. Genome- wide association study reveals molecular mechanism underlying powdery mildew resistance in cucumber, Genome Biol. 2024, 25:252. [CrossRef]

- Eichmann, R.; Hückelhoven, R. Accommodation of powdery mildew fungi in intact plant cells. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, S.L.; Talbot, N.J. Surface attachment and pre-penetration stage development by plant pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2002, 39, 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffer, V.; Johnson, K. B.; Powelson, M. L.; Shishkoff, N. Identification of powdery mildew fungi. The Plant Health Instructor, 2006, 6. [CrossRef]

- Gadoury, D.M.; Cadle-Davidson, L.; Wilcox, W.F.; Dry, I.B.; Seem, R.C.; Milgroom, M.G. Grapevine powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator): A fascinating system for the study of the biology, ecology and epidemiology of an obligate biotroph. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.C.; Gadoury, D.M. Cleistothecia, the source of primary inoculum for grape powdery mildew in New York. Phytopathology 1987, 77, 1509–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirondi, A.; Vela-Corcía, D.; Dondini, L.; Brunelli, A.; Pérez-García, A.; Collina, M. Genetic diversity analysis of the cucurbit powdery mildew fungus Podosphaera xanthii suggests a clonal population structure. Fungal Biol. 2015, 119, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polonio, Á; Pérez-García, A.; Martínez-Cruz, J.; Fernández-Ortuño, D.; de Vicente, A. (2020). The haustorium of phytopathogenic fungi: A short overview of a specialized cell of obligate biotrophic plant parasites. In Progress in Botany (Vol. 82, pp. 337–355). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, R.; Jiang, Y. Effect of powdery mildew on interleaf microbial communities and leaf antioxidant enzyme systems. For. Res. 2023, 34:1535–1547. [CrossRef]

- Lamsal, K.; Kim, S. ; Jung, Kim, Y.S.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, Y.S. Inhibition Effects of Silver Nanoparticles against Powdery Mildews on Cucumber and Pumpkin. Mycobiology,2011, 39(1): 26-32. [CrossRef]

- Porteous-Álvarez, A.J.; Maldonado-González, M.M.; Mayo-Prieto, S.; Lorenzana, A.; Paniagua-García, A.I.; Casquero, P.A. Green Strategies of Powdery Mildew Control in Hop: From Organic Products to Nanoscale Carriers. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusallam, A.H.; Ismail, A.M.; Elshewy, E.S.; El-Gawad, M.E.A. Green synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles: Antifungal activity against powdery mildew disease of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and genotoxicity potentials. Biopestic. Int.; 2024, 20, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Shao, C.; Guo, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, C.; Yang, H. Facile pathway to generate agrochemical nanosuspensions integrating super-high load, eco-friendly excipients, intensified preparation process, and enhanced potency. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 2179–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossier, B.; Jordan, O.; Allémann, E.; Roderguez-Nogales, C. Nanocrystals and nanosuspensions: an exploration from classic formulations to advanced drug delivery systems. Drug Deliv. and Transl. Res. 2024, 14, 3438–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizitiu, D.E.; Sardarescu, D.I.; Fierascu, I.; Fierascu, R.C.; Soare, L.C.; . Ungureanu, C.; Buciumeanu, E.C.; Guta, I.C.; Pandelea, L.M. Grapevine plants management using natural extracts and phytosynthesized silver nanoparticles. Materials, 2022, 15, 8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandila, P.; Mahatmanto, T.; Hsu, J.-L. Metal-Based nanoparticles as nanopesticides: Opportunities and challenges for sustainable Crop Protection. Processes 2025, 13, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Jiménez, L.; Polonio, Á.; Vielba-Fernández, A.; Pérez-García, A.; Fernández-Ortuño, D. Gene mining for conserved, non-annotated proteins of Podosphaera xanthii identifies novel target candidates for controlling powdery mildews by spray-induced gene silencing. Journal of Fungi, 2021, 7(9), 735. [CrossRef]

- Indermaur, E.J.; Day, C.T.C.; Dunn-Silver, A.R.; Smar, C.D. Biorational Fungicides to manage cucurbit powdery mildew on winter squash in New York. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk, K.; Smoli´nska, B.; Majak, I. How Nano-ZnO Affect Tomato Fruits (Solanum lycopersicum L.)? Analysis of Selected Fruit Parameters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.M.; Abd El-Gawed, M.E. Antifungal activity of MgO and ZnO nanoparticles against powdery mildew of pepper under greenhouse condition. Egypt. J. Agric. Res.; 2021, 4: 421–434.

- Masoud, S.A.; Morsy, S.M.; El-Dein, M.M.Z. Controlling powdery mildew using Fe3O4 NPs, yeast, and Bio-Arc and their effects on the performance of lettuce Lactuca sativa L. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 66 (11), 393- 401. [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Wu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Chen, Z.; Kang, D.; Zhang, L.; Pan, C. Nano-selenium enhances melon resistance to Podosphaera xanthii by enhancing the antioxidant capacity and promoting alterations in the polyamine, phenylpropanoid and hormone signaling pathways. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 16;21(1):377. [CrossRef]

- Nandini, B.; Hariprasad, P.; Prakash, H. S.; Shetty, H. S.; Geetha, N. Trichogenic-selenium nanoparticles enhance disease suppressive ability of Trichoderma against downy mildew disease caused by Sclerospora graminicola in pearl millet. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I. U.; Cai, X.; Ali, H.; Akhtar, M. R.; Ghafar, M. A.; Hyder, M.; Hou, Y. Interactions between nanoparticles and tomato plants: Influencing host physiology and the tomato leaf miner’s molecular response. Nanomaterials, 2024, 14(22), 1788. [CrossRef]

- Al-Goul, S. T. The impact of eco-friendly nanoparticles on the management of phytopathogenic fungi: A comprehensive review. Journal of Plant Pathology, 2024, 107, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H. H.; Elsayed, A. B.; Maswada, H. F.; Elsheery, N. I. Enhancing sugar beet plant health with zinc nanoparticles: A sustainable solution for disease management. Journal of Soil, Plant and Environment, 2023, 2(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Elagamey, E.; Abdellatef, M.A.; Haridy, M.S.; Abd El-aziz, E.S.A. Evaluation of natural products and chemical compounds to improve the control strategy against cucumber powdery mildew, Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 165, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, M.; Thabet, M.; Haggag, W.; Mosa, A. Efficacy of silicon and titanium nanoparticles biosynthesis by some antagonistic fungi and bacteria for controlling powdery mildew disease of wheat plants. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2018, 14, 661–674. [Google Scholar]

- Elsharkawy, M. M.; El-Kot, G. A. N.; Hegazi, M. Management of rose powdery mildew by nanosilica, diatomite and bentocide. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control, 25(3), 545–553. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference, ESPCP2015, Cairo, Egypt, 19–22 October 2015.

- Rashad, Y. M, El-Sharkawy, H.H.A.; Belal, B.E.A., Abdel Razik, E.S., Eds.; Galilah, D.A. Silica nanoparticles as a probable anti-oomycete compound against downy mildew, and yield and quality enhancer in grapevines: Field Evaluation, Molecular, Physiological, Ultrastructural, and Toxicity Investigations. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12:763365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. ; Singh, P.K.; Kumar, R.; Nair, K.K.; Alam, I.; Sirvasava, C.; Yadav, S.; Gopal, M.; Choudhury, S.R.; Goswaml, A. Suitability of nano-sulphur for biorational Management of Powdery mildew of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus Moench) caused by Erysiphe cichoracearum. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, H. R.; Alkolaly, A. M. A. Comparative studies on nanosulfur and certain fungicides to control cucumber powdery mildew disease and their residues in treated fruits. Science Exchange Journal, 2020, 41(1), 54–70. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yada, R. Y. Nanotechnologies in agriculture: New tools for sustainable development. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2011, 22(11), 585–594. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.; Hasan, W.; Ramesha N, M.; Pujar, K.; Singh, R.; Panotra, N.; Satapathy, S.N. Nanotech for Crop Protection: Utilizing Nanoparticles for Targeted Pesticide Delivery Uttar Pradesh J. Zool.; 2024, 45 (6), 46-71, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ruano-Rosa, D.; Sánchez-Hernández, E.; Baquero-Foz, R.; Martín-Ramos, P.; Martín-Gil, J.; Torres-Sánchez, S.; Casanova-Gascón, J. Chitosan-based bioactive formulations for the control of powdery mildew in viticulture. Agronomy, 2022, 12, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, H.; Mostowfizadeh-Ghalamfarsa, R.; Ghanadian, M. (2025). Characterization, biochemical defense mechanisms, and antifungal activities of chitosan nanoparticle-encapsulated spinach seed essential oil. J. Agr. Food Research, 2025, 22: 102016. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Ghosh, V. Thyme (Thymus vulgaris) Essential Oil–Based Antimicrobial Nanoemulsion Formulation for Fruit Juice Preservation. In: Sadhukhan, P.; Premi, S. (eds) Biotechnological Applications in Human Health. Springer, Singapore, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Detsi, A.; Kavetsou, E.; Kostopoulou, I.; Pitterou, I.; Pontillo, A. R. N.; Tzani, A. ; Christodoulou; P. Siliachli, A.; Zoumpoulakis, P. Nanosystems for the encapsulation of natural products: The case of chitosan biopolymer as a matrix. Pharmaceutics, 2020; 12, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, N.; Singh, V. K.; Dwivedy, A. K.; Chaudhari, A. K.; Dubey, N. K. Assessment of nanoencapsulated Cananga odorata essential oil in chitosan nanopolymer as a green approach to boost the antifungal, antioxidant and in situ efficacy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2021, 171, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelatha, S.; Kumar, N.; Yin, T. S.; Rajani, S. Evaluating the antibacterial activity and mode of action of thymol-loaded chitosan nanoparticles against plant bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2022; 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouky, M.M.; Abou-Saleh, R.H.; Moussa, TA.A.; Fahmy; H. M. Nano-chitosan-coated, green-synthesized selenium nanoparticles as a novel antifungal agent against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: in vitro study. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keawchaoon, L.; Yoksan, R. (2011). Preparation, characterization and in vitro release study of carvacrol-loaded chitosan nanoparticles. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2011, 84, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyzioglu, G. C.; Tornuk, F. Development of chitosan nanoparticles loaded with summer savory (Satureja hortensis L.) essential oil for antimicrobial and antioxidant delivery applications. LWT, 2016; 70, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, G.; Stracquadanio, S.; Leonardi, M.; Napoli, E.; Malandrino, G.; Cafiso, V.; Stefani, S.; Geraci, C. Oregano and thyme essential oils encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles as effective antimicrobial agents against foodborne pathogens. Molecules, 2021. 26, 4055. [CrossRef]

- Gasti, T.; Dixit, S.; Hiremani, V. D. Chougale, R. B.; Masti, S. P.; Vootla, S. K.; Mudigoudra, BS. Chitosan/pullulan-based films incorporated with clove essential oil loaded chitosan-ZnO hybrid nanoparticles for active food packaging. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2022, 277,118866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yuan. ; Gao, Y.; Su, P.; Jia, H.; Tang, C.; Meng, H.; Wu, L. Nano protective membrane coated wheat to resist powdery mildew. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2024, 15, 1369330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Kar, K.; Mazumder, R. Exploration of different strategies of nanoencapsulation of bioactive compounds and their ensuing approaches. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2024, 10, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, I.; Waleed, M. Evaluation of the effectiveness of biologically synthesized copper and zinc nanoparticles in controlling powdery mildew on Rose hybrida. Natural and Engineering Sciences, 2025; 10, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pérez, O.; GallegosMorales, G.; Espinoza-Ahumada, C.A.; Delgado-Luna, C.; Rangel, P.; Espinosa-Palomeque, B. Potential of chitosan for the control of powdery mildew (Leveillula taurica (Lév.) Arnaud) in a Jalapeño Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) cultivar. Plants, 2024, 13, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhini, R.; Rajeswari, E.; Harish, S.; Sivakumar, V.; Selvi, R.G.; Sundrasharmila, D. J. Role of chitosan nanoparticles in sustainable plant disease management. Journal of Nanoparticle Research, 2025; 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Adnan, F.; Bazai, M. J.; Fareed, S. R.; Tareen, J. K.; Uddin, M.; Kakar, H. Powdery mildew: A disease of grapes and the fungicides’ mode of action—A review. Bioscience Research, 2022; 3, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaz, H.; Rawat, K.; Saffeullah, P.; Umar, S. Silica nanoparticles synthesis and applications in agriculture for plant fertilization and protection: A review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023; 23, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laane, H.-M. The effects of foliar sprays with different silicon compounds. Plants, 2018; 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnani, K. K.; Boddu, V. M.; Chadha, N. K.; Saffeullah, P.; Umar, S. Metallic and non-metallic nanoparticles from plant, animal, and fisheries wastes: Potential and valorization for application in agriculture. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2022; 29, 81130–81165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, X.; Shen, D.; Wu, F.; Pleixats, R.; Pan, J. Functionalized silica nanoparticles: Classification, synthetic approaches and recent advances in adsorption applications. Nanoscale, 2021; 13, 16200–16230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, Y.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; Alpuche-Solís, Á.G.; Cabrera, R.I.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Carbon Nanotubes Decrease the Negative Impact of Alternaria solani in Tomato Crop. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, H.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Zhao, J. Graphene Oxide Exhibits Antifungal Activity against Bipolaris sorokiniana In Vitro and In Vivo. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Mallya, R.; Suvarna, V.; Khan, T.A.; Momin, M.; Omri, A. Nanoparticles—Attractive Carriers of Antimicrobial Essential Oils. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H. (2019). Method of controlling powdery mildew using nanobubble water (WO2019230789A1). AQUASOLUTION Corp.

- Slavin, Y.N.; Bach, H. Mechanisms of antifungal properties of metal nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venugopal, E.; Krishna, S.B.N.; Golla, N.; Patil, S.J. Nanofungicides: A Promising Solution for Climate-Resilient Plant Disease Management. In: Abd-Elsalam, K.A.; Abdel-Momen, S.M. (eds) Plant Quarantine Challenges under Climate Change Anxiety. Springer, Cham, 2024, pp 513-532. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Hashemi, M.; Hosseini, S. M. Nanoencapsulation of Zataria multiflora essential oil preparation and characterization with enhanced antifungal activity for controlling Botrytis cinerea, the causal agent of gray mould disease. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2015, 28, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanwate, R.M.; Babu, R.H.; Wadhave, A.A.; Mishra, V. Advancements in Nanosuspension Technology for Drug Delivery. Biomedical Materials & Devices. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, T.R.; Raj, A.; Tseng, T.H.; Xiao, H.; Ngu, R.R. ; MoF.S.; F.S.; Halder, S.; Xu, M.; Wu, M.J.; Bao, S.; Sheu, W.C. Biocompatibility of nanomaterials and their immunological properties. Biomed Mater. 2021, 16(4):10. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Su, X.; Yan, S.; Shen, J. Multifunctional nanoparticles and nanopesticides in agricultural application. Nanomaterials, 2023, 13(7), 1255. [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, L.; Alvarez-Puebla, R. A.; Pazos-Perez, N. Surface modifications of nanoparticles for stability in biological environments. Chemical Society Reviews, 2018, 47(10): 3862–3871. [CrossRef]

- Wohlmuth, J.; Tekielska, D.; Cˇechová, J.; Baránek, M. Interaction of the Nanoparticles and Plants in selective growth stages—usual effects and resulting impact on usage perspectives. Plants 2022, 11, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Lu, H. Protein PEPylation: A New Paradigm of Protein–Polymer Conjugation Bioconjugate Chemistry, 2019, 30 (6), 1604-1616. [CrossRef]

- Lanke, N. P.; Chandak, M. B. Recent trends in deep learning and hyperspectral imaging for fruit quality analysis: An overview. J. Opt. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Kashyap, R.; Bansal, K.; Das, R.; Sandhu, K.; Singh, G.; Saini, D. K. Transition from conventional to AI-based methods for detection of foliar disease symptoms in vegetable crops: A comprehensive review. Journal of Plant Pathology, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu Thanh, C.; Gooding, J. J.; Kah, M. Learning lessons from nanomedicine to improve the design and performances of nano-agrochemicals. Nature Communications. 2025, 16, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).