Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

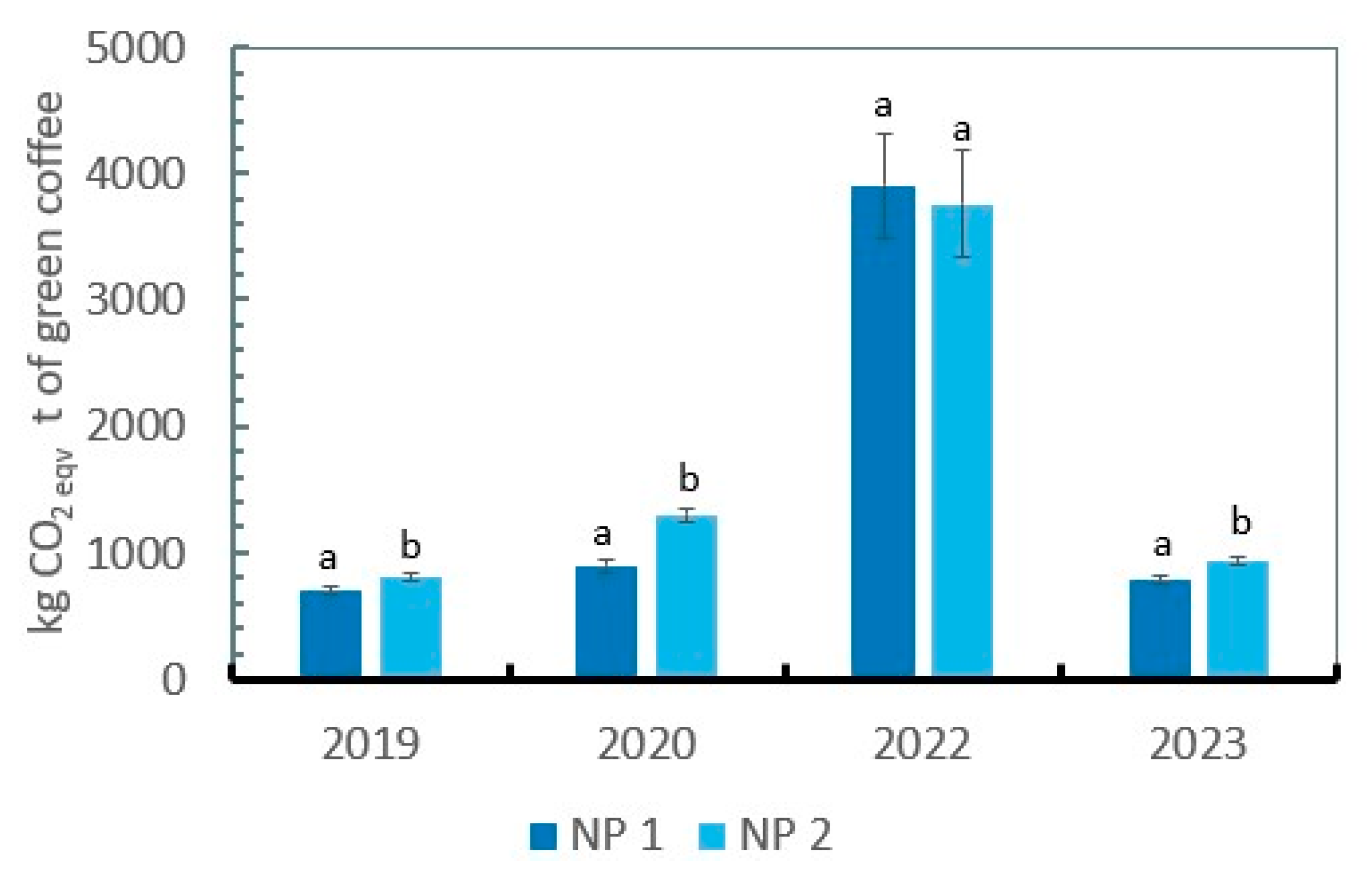

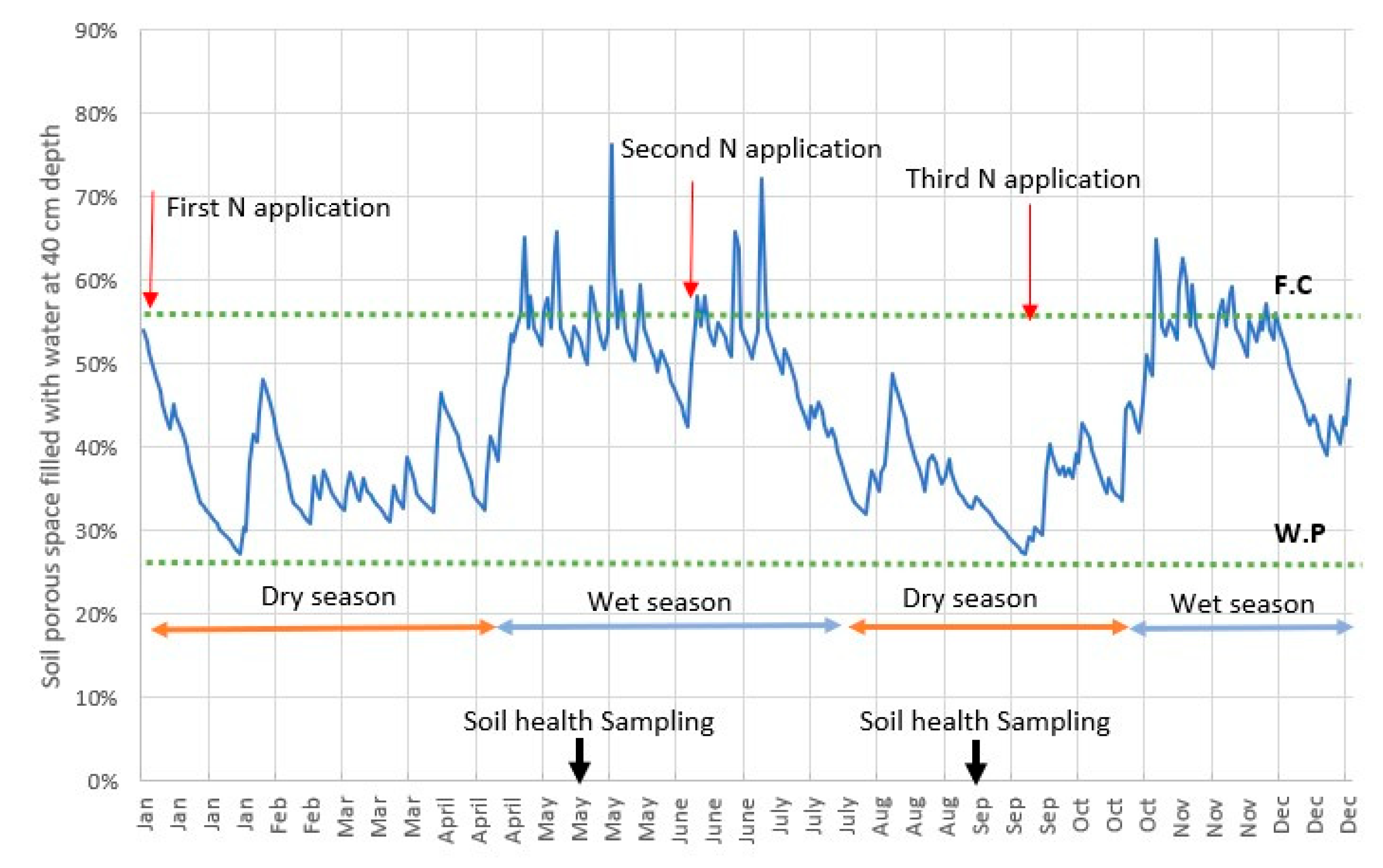

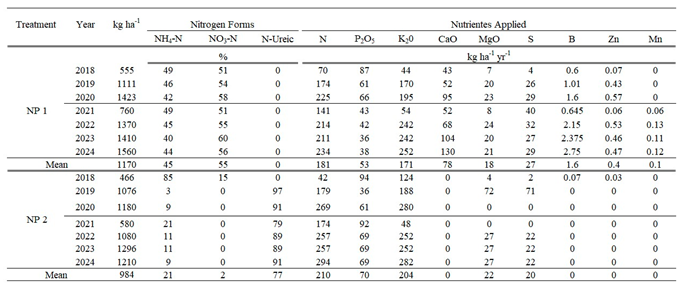

Nitrogen (N) is the most applied nutrient by the coffee farmers, followed by potassium (K), and phosphorous (P), without application of other important macronutrients like calcium (Ca), boron (B) and zinc (Zn). The study conducted in Colombia, in the Central-west coffee region during 2018 to 2024, evaluated the response of coffee (cv. Castillo®) with two different nutritional management practices (NPs) on productivity, nitrogen use efficiency (NUE), carbon footprint (CFP) and soil health. The NPs evaluated were NP1: Ammonium-nitrate based NPK with 15% less nitrogen containing the most important nutrients to produce coffee in acid soils (181 kg N, 53 kg P2O5, 171 kg K2O, 78 kg CaO, 18 kg MgO, 27 kg S-1.6 kg B,0.4 kg Zn, 0.1 kg Mn), and NP 2: Urea based NPK blend, representing common farmer practice (210 kg N, 70 kg P2O5, 204 kg K2O; 22 kg MgO and 22 kg S, without CaO). Both treatments were amended with dolomitic lime to increase base saturation (˃60%) and soil pH (˃5.0). After six years trial no significant differences on coffee yield were observed (2.55 and 2.50 t ha-1 of green coffee beans for NP 1 and 2, respectively), but significant differences occurred on NUE with 45% and 35% for NP 1 and 2, respectively, as well as for CFP, with significant differences during 2019, 2020 and 2023. Soil health indicators estimated by Solvita ® test including soil respiration and microbial biomass were significantly influenced by NP, soil depth and sampling time (wet season- May and dry season- September ), but other soil fertility parameters were less affected by soil moisture variation, with higher contents of Ca, Mg, S, B in the soil profile and lower soil acidity for NP 1 as compared to NP 2.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Influence of Two Nutrient Management Practices on Productivity and NUE

2.2. Influence of Two Nutrient Management Practices on the Carbon Footprint

2.3. Influence of Nutrient Management Practices on Soil Health Indicators

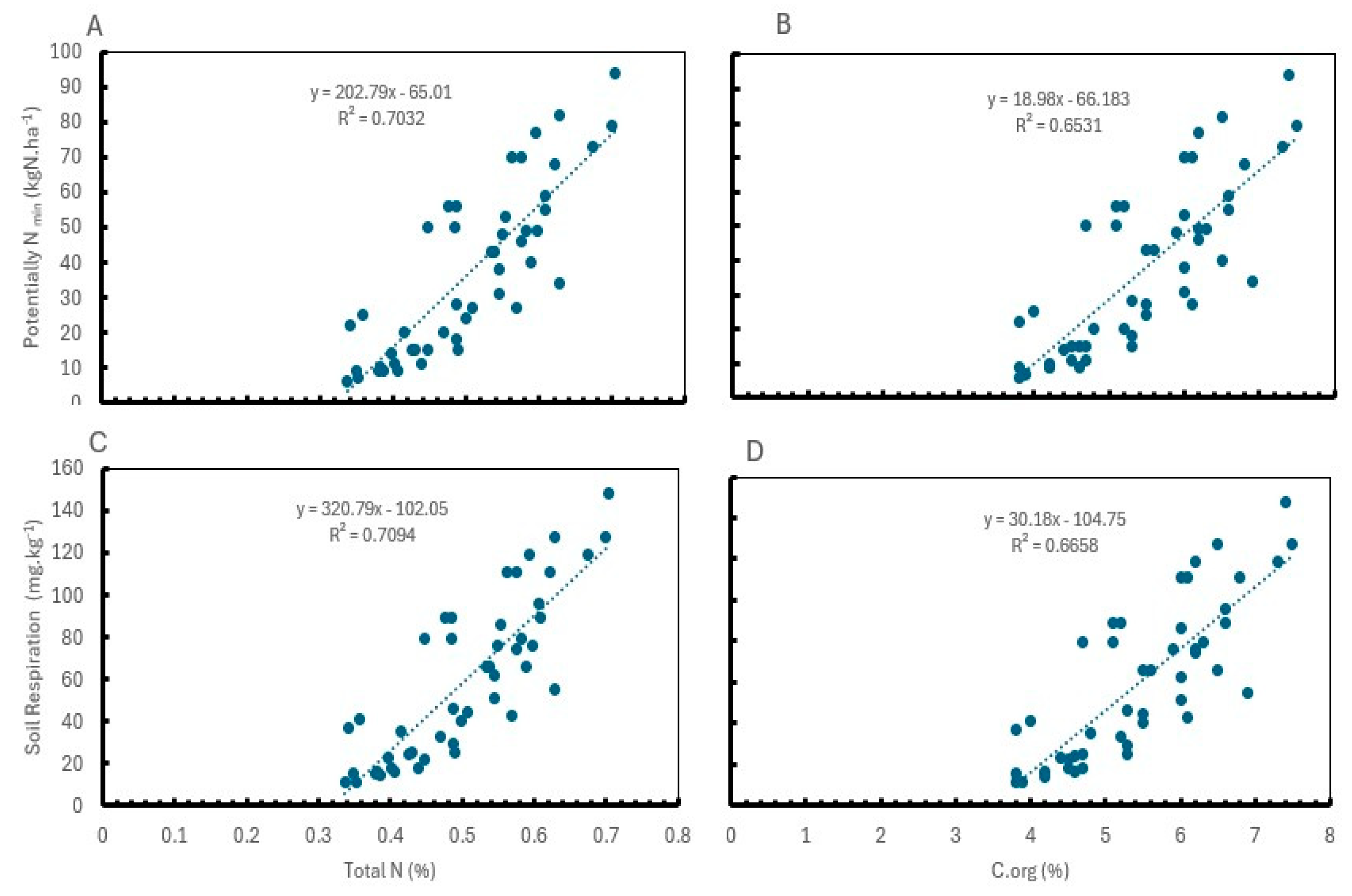

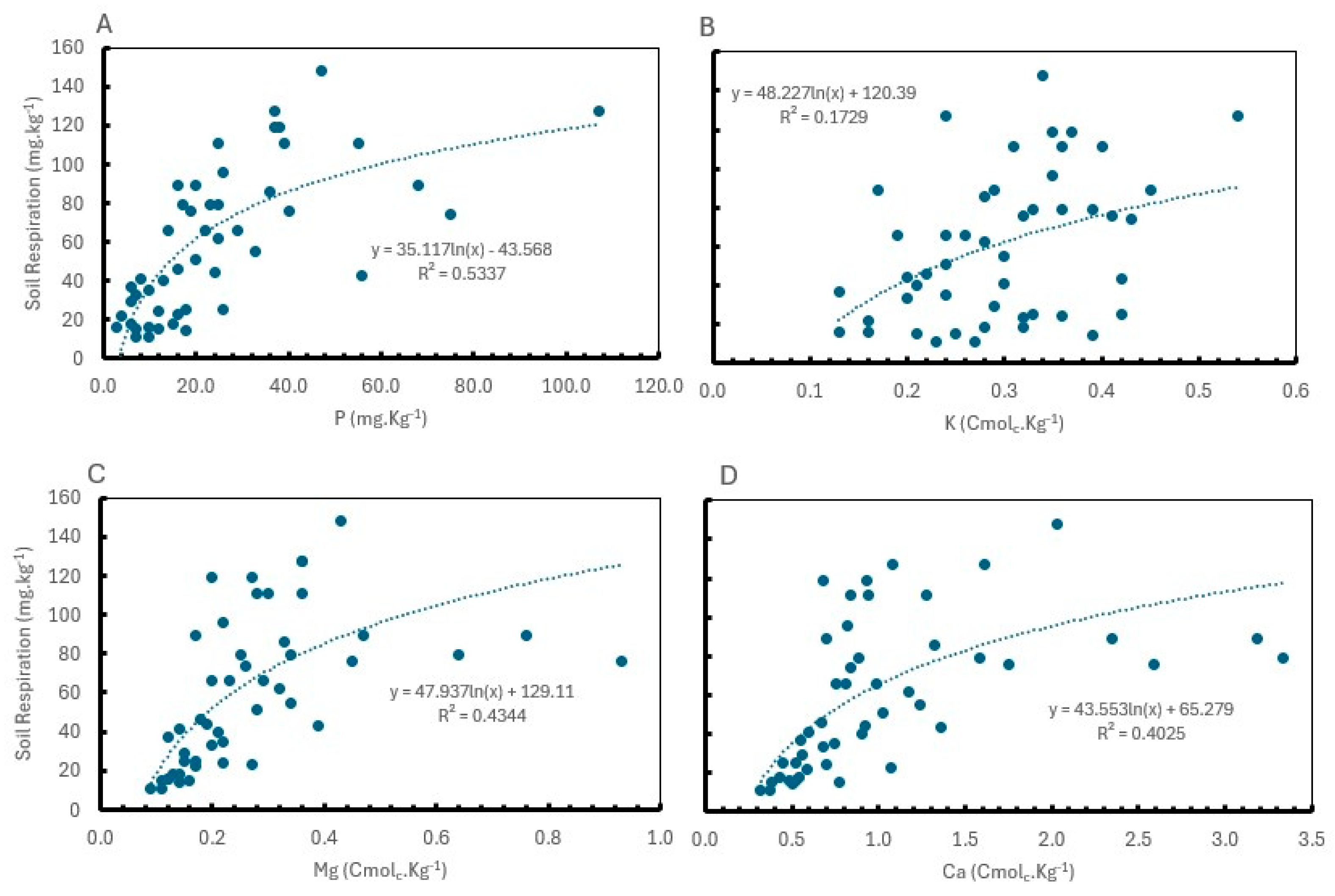

2.4. Correlation Between Soil Health Indicators

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Location

4.2. Treatment Description

4.3. Variables Evaluated

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FC | Soil volumetric moisture at field capacity |

| WP | Soil volumetric moisture at wilting point |

| P.Nmin | Potentially mineralizable nitrogen |

| NUE | Nitrogen use efficiency |

| PCF | Product carbon footprint |

References

- Federación Nacional de Cafeteros Colombia-FNC. Informe del gerente 2023 al 92 congreso nacional de cafeteros 2023. 58p.

- Sadeghian, S. Soil acidity, a common limitation for coffee production (in Spanish). Avances técnicos, 2016; No 466, pp.1-8 www.cenicafe.org.

- Duque, H., Salazar, H., Rojas, L., & Gaitán, Á. (2021). Economic Analysis of Technologies for Coffee Production in Colombia (in Spanish). In Análisis económico de tecnologías para la producción de café en Colombia. 2021, Cenicafé. [CrossRef]

- Favarin, J.L.; de Souza, L.T.; Mazzafera, P.; Dimenstein, L. Soil correction and fertilization of irrigated coffee plants in production (In Portuguese). 2021, In Cafeicultura do Cerrado/Editores Técnicos Gladyston Rodrigues/Carvalho et al-Belo Horizonte; EPAMIG: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 564p.

- Ramírez, B.V.H., Küsters, J., Thiele, E., & Lopez, J. Physiological and Agronomical Response of Coffee to Different Nitrogen Forms with and without Water Stress. Plants. 2024, Vol. 13, Page 1387, 13(10), 1387. [CrossRef]

- Cannavo, P., Harmand, J.-M., Zeller, B., Vaast, P., Ramírez, J.E., and Dambrine, E. Low nitrogen uses efficiency and high nitrate leaching in a highly fertilized Coffea arabica–Inga densiflora agroforestry system: a 15N labeled fertilizer study. Nutr. Cycl, Agroecosyst. 2013,95, 377–394. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. Enhanced nitrogen fertiliser technologies support the ’4R’concept to optimize crop production and minimize environmental losses. Soil Research. 2017, 55:463-472. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.C. Coffee, Cocoa and tea. Crop production science in horticulture series, 1999, 8 CABI, (UK). ISBN 0-85198-919-5.300p.

- Favarin, L, J.; Bernades, M.D.; de Souza, T.L.; Corte, B.J.L. Roads to improve productivity of arabica coffee (in Portuguese). Informaciones Agronomicas, 2018, 164. 6p.

- Sadeghian, S., & González-Osorio, H.Fertilizantes nitrogenados. Implicaciones agronómicas para el cultivo del café en Colombia. Avances Técnicos Cenicafé. 2022, 544, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, B.V.H., Küsters, J., Thiele, E., & Leal, L. Boron Nutrition in Coffee Improves Drought Stress Resistance and, Together with Calcium, Improves Long-Term Productivity and Seed Composition. Agronomy. 2024, Vol. 14, Page 474, 14(3), 474. [CrossRef]

- Leal, L., Salamanca, A., & Sadeghian, S. Urea Volatilization Losses from Coffee Plantations. Better Crops. 2010, 94. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265233941.

- Cantarella, H., Mattos, Jr. D., Quaggio, J.A., and Rigolin, A.T. New trends in sugarcane fertilization: Implications for NH₃ volatilization, N₂O emissions and crop yields. Journal of Environmental Management. 2003, 342, 118233. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, T.; Bartelega, L.; Santos, C.; Dutra, M.P.; Sarkis, L.F.; Guimarães, R.J.; Dominghetti, A.W.; Zito, P.C.; Fernandes, T.J.; Guelfi, D. Technologies for Fertilizers and Management Strategies of N-Fertilization in Coffee Cropping Systems to Reduce Ammonia Losses by Volatilization. Plants. 2022 11, 3323. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, L.T., de Oliveira, P.D., Ferreira, S.C., Pereira, R.T.H., Campos, C.J.P., da Silva, R.E.R., Fernandes, J.T., de Souza, R.T., Ramirez, B.V., and Guelfi, D. Nitrogen fertilizer technologies: Opportunities to improve nutrient use efficiency towards sustainable coffee production systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023 345, 108317. [CrossRef]

- Fenelli, B. T.A.; Reichardt, K.; Favarin, J.L.; Bacchi, S.O.O.; Silva, L.A.; Timm, L.C. Fertilizer 15N balance in a coffee cropping system: A case study in Brazil. R. Bras.Ci.Solo. 2008 32:1459-1469.

- Cantarella, H., Mattos Jr., D., Quaggio, J. A., & Rigolin, A. T. Fruit yield of Valencia sweet orange fertilized with different nitrogen sources and the loss of applied N. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems. 2003, 67(3), 215–223. [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, L., Dutra, M., dos Santos, C., Rodrigues, B., Urquiaga, S., & Guelfi, D. Nitrogen fertilizers technologies as a smart strategy to mitigate nitrous oxide emissions and preserve carbon and nitrogen soil stocks in a coffee crop system. Atmospheric Environment: X. 2023, 20, 100224. [CrossRef]

- Vaast, P., Zasoski, R. J., & Bledsoe, C. S. Effects of solution pH, temperature, nitrate/ammonium ratios, and inhibitors on ammonium and nitrate uptake by Arabica coffee in short-term solution culture. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 1998, 21(7), 1551–1564. [CrossRef]

- Carr, N. F., Boaretto, R. M., & Mattos, D. Coffee seedlings growth under varied NO3−:NH4+ ratio: Consequences for nitrogen metabolism, amino acids profile, and regulation of plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2020, 154, 11–20. [CrossRef]

- Arias S., E., Sadeghian K., S., Mejía M., B., & Morales L., C. S. Nitrogen leaching in some soils of the coffee zone and its relationship with texture (in Spanish). Cenicafé. 2009, 60(3), 239–252. Recuperado de https://biblioteca.cenicafe.org/handle/10778/154.

- Sadeghian, K.S.; Gonzalez, O.H. Response of coffee (Coffea arabica L.) to nitrogen sources and doses in the seedling stage (in Spanish).Cenicafé. 2014, 65,1:34-43.

- Santos, C., Malta, M. R., Gonçalves, M. G. M., Borém, F. M., Pozza, A. A. A., Martinez, H. E. P., de Souza, T. L., Chagas, W. F. T., de Melo, M. E. A., Oliveira, D. P., Lima, A. D. C., de Abreu, L. B., Reis, T. H. P., de Souza, T. R., Builes, V. R., & Guelfi, D. Chloride Applied via Fertilizer Affects Plant Nutrition and Coffee Quality. Plants. 2023, 12(4), 885. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, V. H., Küsters, J., Thiele, E., Leal-Varon, L. A., & Arteta-Vizcaino, J. (2023). Influence of Variable Chloride/Sulfur Doses as Part of Potassium Fertilization on Nitrogen Use Efficiency by Coffee. Plants. 2023, 12(10). [CrossRef]

- Gmünder, S.; Toro, C.;Rojas, A.M.; Rodriguez, V.N. Enviromental Footprint of coffee in Colombia: Guide Document: 2020, 88p. Swiss cooperation Agency/FNC/Centro Nacional de Producción Mas Limpia/Insitu/Quantis. Available in: ENVIRONMENTAL-COFFEE-IN-COLOMBIA-1-comprimido.pdf.

- Pirani, A., Fuglestvedt, J. S., Byers, E., O’Neill, B., Riahi, K., Lee, J.-Y., Marotzke, J., Rose, S. K., Schaeffer, R., & Tebaldi, C. Scenarios in IPCC assessments: lessons from AR6 and opportunities for AR7. Npj Climate Action, 2024, 3:1, 3(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.; Alden, J.; Baranowski, P. The changing climate of the Colombia Coffee. Coffee and Cocoa International 2019, 46,2:1-5.

- Perez, R.E.P.; Ramirez, B.V.H.; Peña, Q.A.J. Spatial and temporal variability of the air temperature in the Colombian coffee zone (in Spanish). Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía. 2016, UNAM, 89:23-40. [CrossRef]

- Avelino, J.; Cristancho, M.; Georgion, S.; Imbach, P.; Aguilar, L.; Bornemann, G.; Läderach, P.; Anzueto, F.; Hruska, J.A.; Morales, C. (2015). The coffee rust crisis in Colombia and Central America (2008-2013): impacts, plausible causes and proposed solutions. Food Security, 7:303-321. [CrossRef]

- Poore, J., Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science. 2018 360, 987–992. [CrossRef]

- Bunn, C., Läderach, P., Ovalle Rivera, O., & Kirschke, D. A bitter cup: climate change profile of global production of Arabica and Robusta coffee. Climate Change. 2015, 129(1–2), 89–101. [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.N.; Perfecto, I.; Vandermeer, J. Synergies between agricultural intensification and climate change could create surprising vulnerabilities for crops. BioScience. 2008, 58,9: 847-854. [CrossRef]

- Noponen, R.A.M.; Haggar, P.J.; Jones E.G.; Healey, R.J. Intensification of coffee systems can increase the effectiveness of REDD mechanisms. Agricultural Systems. 2013, 119:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Hijbeek R, van Loon MP, van Ittersum MK. Fertiliser use and soil carbon sequestration: opportunities and trade-offs. CCAFS Working. 2019, Paper no. 264. Wageningen, the Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Available online at: www.ccafs.cgiar.org.

- Schreefel, L.; Shulte, R.P.O.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Pas Schrijver, A.; van Zaten, H.H.E. Regenerative agriculture- the soil is the base. Global Food Security. 2020, 26, 100404. [CrossRef]

- Brentrup, F., Lammel, J., Stephani, T., & Christensen, B. Updated carbon footprint values for mineral fertilizer from different world regions. 2018. LCA Food 2018 and LCA AgriFood Asia 2, 1. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329774170.

- Gao, Y., & Cabrera, A. Greenhouse gas emissions from nitrogen fertilizers could be reduced by up to one-fifth of current levels by 2050 with combined interventions. Nature Food. 2023, 4:2, 4(2), 170–178. [CrossRef]

- Baligar, V.C.; Fragaria, N.K.; He, L. Nutrient uses efficiency in plants. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis. 2001, 32:7-8, 921-950. [CrossRef]

- Grzebisz, W.; Diatta, J.; Barłóg, P.; Biber, M.; Potarzycki, J.; Łukowiak, R.; Przygocka-Cyna, K.; Szczepaniak, W.Soil Fertility Clock—Crop Rotation as a Paradigm in Nitrogen Fertilizer Productivity Control. Plants. 2022, 11, 2841. [CrossRef]

- Barłóg, P. Improving Fertilizer Use Efficiency—Methods and Strategies for the Future. Plants. 2023, 12, 3658. [CrossRef]

- Brentrup, F.; Lammel, J. Nitrogen Uses Efficiency, Nitrogen balance and Nitrogen productivity- a combined indicator system to evaluate Nitrogen use in crop production systems. Procedings of the International Nitrogen Initiative Conference, “ Solutions to improve nitrogen use efficiency for the world”. 2016, 4-8, Melbourne, Australia.

- Fenelli, B. T.A.; Reichardt, K.; Favarin, J.L.; Bacchi, S.O.O.; Silva, L.A.; Timm, L.C. Fertilizer 15N balance in a coffee cropping system: A case study in Brazil. R. Bras.Ci.Solo. 2008, 32:1459-1469.

- Salamanca, J.A.; Doane, A.T.; Horwalth, R.W. Nitrogen use efficiency in Coffee at the vegetative stage as influenced by fertilizer application method. Frontiers in Plan Science. 2017, 8, 223.11p. [CrossRef]

- Van, H., Schroth, G., Läderach, P., & Rodríguez, B. Carbon footprints and carbon stocks reveal climate-friendly coffee production. Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 2014, 34(4), 887–897. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.; Lal, R. Carbon accounting for coffee-base farming systems. 2021. World Coffee Research/Center for Carbon Management and Sequestration, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH. 43210, USA, 26p.

- Vargas, V.; Coser, T.; de Souza, T.R.; Brentrup, F.; Hesan, M.; Neves, C.; Bungener, S.; Otto, R.; Santana-Carvalho, M.C.;Guelfi, D.; Cantarella, H. Carbon Footprint in Agriculture: Insights towards neutral crop production and industry integration. Informaciones Agronomicas Nutricion de Plantas. 2023, 20:1-18. informacoes-agronomicas-2023.pdf.

- Alvarez, R., & Alvarez, C. R. Soil organic matter pools and their associations with carbon mineralization kinetics. Soil Science Society America Journal. 2000, 64, 184–189. [CrossRef]

- Haney, R.L.; Brinton, H.W., Evans, E. Estimating soil carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus mineralization from short-term carbon dioxide respiration. Communication in Soil Science and Plant Analysis. 2008, 39:2206-2720. [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A.J.; Haney, R.L.; Honey, C.W.; Schomberg, H.H.; Hons, M.F. Flush of carbon dioxide following rewetting of dried soil relates to active organic pools. Soil Sci.Soc.Am.J. 2000,64:613-623. [CrossRef]

- Haney, R.L; Franzluebbers, A.J. Soil CO2 evolution: Response from arginine additions. Applied Soil Ecology, 2009,42,3:324-327. [CrossRef]

- Mac Bean, G.; Kitchen, R.N.; Veum, S.K.;Camberato, J.J.; Ferguson, B.R.; Fernandez, G.F.; Franzen, W.D.; Laboski, A.M.S.; Nafziger, D.E.; Sawyer, E.J.; Yost, M. Relating four-day soil respiration to corn fertilizer need across 49 U.S Midwest fields. Soil Sci.Soc.Am.J. 2020,84:1195-1208. [CrossRef]

- Culman, S. W., Snapp, S. S., Freeman, M. A., Schipanski, M. E., Beniston, J., Lal, R., Wander, M. M. Permanganate oxidizable carbon reflects a processed soil fraction that is sensitive to management. Soil Science Society of America Journal. 2012, 76, 494–504. [CrossRef]

- Hurisso, T. T., Culman, S. W., Horwath, W. R., Wade, J., Cass, D., Beniston, J. W., Ugarte, C. M. Comparison of permanganate-oxidizable carbon and mineralizable carbon for assessment of organic matter stabilization and mineralization. Soil Sci. Soc. of Am. J. 2016, 8,5: 1352–1364. [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, S.; Barot, S.; Barré, P.; Bdioui, N.; Rumpel, C. Stability of organic carbon in deep soil layers controlled by fresh carbon supply. Nature-Letters. 2007, 450,8:277-280. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Machmuller, B.M.; Blecker, W.S.; Buchanan, M.C.; A.B.I.; Firth, G.A.; Ippolito, A.J. Comparising the soil management assessment framework to the Haney Soil Health test across managed agroecosystems. agronomy.2025,15,643. [CrossRef]

- Hergoualc’h, K.; Blachart, E.; Skiba, U.; Hénault, C.; Harmad, J.M. Changes in carbon stock and greenhouse gas balance in a coffee (Coffea arabica) monoculture versus and agroforestry system with Inga densiflora, in Costa Rica. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 2012, 148:102-110. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Shan, Y.; Yue, Z.; Giacchini, P.; Montechio, D.; Gaggia, F.; Alberoni, D.;Baffoni, L.; Zhang, Q.; Xiong, P.; Marzadori, C.; Gioia, D.D. Factors Driving Soil Respiration Rate After Different Fertilizer Sources Addition. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2468. [CrossRef]

- Linn, D.M.; Doran, J.W. Effect of Water-Filled Pore Space on Carbon Dioxide and Nitrous Oxide Production in Tilled and Non tilled Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. of Am. J. 1984, 48, 6:1267-1272. [CrossRef]

- US-Department of Agriculture & Natural Resources Conservation Service. Soil Respiration, Soil Health-Guides or Educators. 2022, 10p. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-10/Soil%20Respiration.pd.

- Jones, D. L., & Shannon, D. Mineralization of amino acids applied to soils impact of soil sieving, storage, and inorganic nitrogen additions. Soil Sci. Soc. of Am. J. 1999, 63, 1199– 1206. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, B.V.H., Küsters, J., de Souza, T., & Simmes, C. Calcium Nutrition in Coffee and Its Influence on Growth, Stress Tolerance, Cations Uptake, and Productivity. Frontiers in Agronomy. 2020, 2, 590892. [CrossRef]

- de Castro-Lopes, A.A.; Gomes de Sousa, D.M.; Montandon, C.G; dos Reis Junior, F.B.; Goedert, J.W.; Mendes, C.I. Interpretation of Microbial Soil Indicators as a Funtion of Crop Yeld and Organic Carbon. Soil Sci. Soc. of Am. J. 2013, 77, 461-472. [CrossRef]

- González, O.H. Identification of the main soil units in the coffee area. In Manual del Cafetero Colombiano: Investigación y Tecnología Para la Sostenibilidad de la Caficultura. 2013 Cenicafé; Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, Volume 1, pp. 269–283, (In Spanish).

- Ramirez, B. V.H.; Küsters, J. Calcium and Potassium Nutrition Increases the Water Use Efficiency in Coffee: A Promising Strategy to Adapt to Climate Change. Hydrology. 2021, 8, 75. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, V., Jaramillo, A., Arcila, J., & Montoya, E. Estimación de la humedad del suelo en cafetales a libre exposición solar. Cenicafé. 2010, 61(3), 251–259.

- Arcila, J., Buhr, L., Bleiholder, H., Hack, H., Meier, U., & Wicke, H. Application of the extended BBCH scale for the description of the growth stages of coffee (Coffea spp.). Annals of Applied Biology. 2002, 141(1), 19–27. [CrossRef]

- Montilla, J., Arcila, J., Aristizábal, M., Montoya, E., Puerta, G., Oliveros, E., & Cadena, G. Characterization of some physical properties and conversion factors of coffee during the traditional wet milling process (in Spanish). Cenicafé. 2008, 59(2), 120–142.

- Dobermann, A. Nutrient use efficiency – measurement and management. Department of Agronomy and Horticulture: Faculty Publications. 2007. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/agronomyfacpub/1442.

- Haney, R.L.; Haney, E.B. Simple and Rapid Laboratory Method for Rewetting Dry Soil for Incubations. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2010, 41, 1493–1501. [CrossRef]

- Haney, L.R.; Haney, B.E.; Smith, R.D.; Harmel, D. R.; White, J.M. The soil health tool- Theory and initial broad-scale application. Applied Soil Ecology. 2018,125:162-168. [CrossRef]

- Di Rienzo, J. A., Casanoves, F., Balzarini, M. G., Gonzalez, L., Tablada, M., & Robledo, C. W. Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. 2016 InfoStat software estadístico versión 2012. Manual de usuario. InfoStat versión 2016. Acceso, 30(09).

| Year | Yield (t ha-1) | NUE (%) | N content in leaves (%) | Total N content in soil (%) | ||||

| NP 1 | NP 2 | NP 1 | NP 2 | NP 1 | NP 2 | NP 1 | NP 2 | |

| 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 |

2.65 2.38 -- 0.47 2.27 5.17 |

2.40 2.06 -- 0.63 2.31 5.12 |

47.0b 49.0b -- 7.0a 44.0b 86.0b |

37.0a 27.0a -- 8.0a 36.0a 68.0a |

-- 2.79 -- 2.56 2.67 -- |

-- 2.95 -- 2.43 2.73 -- |

-- 0.45 -- -- 0.48 -- |

-- 0.44 -- -- 0.45 -- |

| Mean | 2.55 | 2.50 | 45.0B | 35.0A | 2.68 | 2.70 | 0.46 | 0.44 |

| Years Treatments |

** ns |

** ** |

** ns |

** ns |

||||

| Treatment | N content in the coffee cherries (%) |

N uptake per t of green coffee bean kg t-1 |

| NP 1 NP 2 |

1.85 1.77 |

38.3 36.7 |

| Mean | 1.81 | 37.5 |

| p-value | 0.2615ns | 0.2574ns |

| Treatment | Soil depth | C.org | Soil respiration | Microbial biomass | P.Nmin¥ | Total N |

| cm | % | mg kg-1 kg ha-1 | % | |||

| NP 1 | 0-10 | 6.28c | 82.50cd | 1845.0cd | 51.50cd | 0.59d |

| NP 2 | 5.18a | 60.00bc | 1350.0bc | 37.50bcd | 0.48b | |

| Mean | 5.73C | 71.25C | 1.597.5C | 50.50C | 0.54C | |

| NP 1 | 10-20 | 5.43b | 59.75bc | 1344.5bc | 37.50bcd | 0.51bc |

| NP 2 | 4.43a | 20.00a | 470.0a | 12.25ab | 0.40a | |

| Mean | 4.93B | 39.90B | 907.0B | 24.9B | 0.45B | |

| NP 1 | 20-30 | 4.28b | 22.75ab | 530.5ab | 14.0ab | 0.39a |

| NP 2 | 3.88a | 19.50a | 459.0a | 11.75a | 0.35a | |

| Mean | 4.08A | 21.10A | 494.0A | 12.9A | 0.37A | |

| NP 1 | Mean | 5.33B | 55.00B | 1240.0B | 34.33B | 0.49B |

| NP 2 | 4.49A | 33.17A | 759.67A | 20.50A | 0.41A | |

| Treatment | Depth | C.org | Soil respiration | Microbial biomass | P. Nmin¥ | Total N |

| cm | % | mg kg-1 | % | |||

| NP 1 | 0-10 | 6.48cd | 87.0bc | 1944.0bc | 54.5bc | 0.60cd |

| NP 2 | 6.93d | 100.0c | 2230.0c | 61.75c | 0.64d | |

| Mean | 6.70C | 93.5B | 2087.0B | 58.12B | 0.62C | |

| NP 1 | 10-20 | 5.93bc | 82.25bc | 1839.5bc | 51.7bc | 0.55bc |

| NP 2 | 6.28cd | 100.0c | 2230.0c | 63.0c | 0.59cd | |

| Mean | 6.10B | 91.25B | 2034.7B | 57.3B | 0.57B | |

| NP 1 | 20-30 | 5.35ab | 52.50ab | 1185.0ab | 32.75ab | 0.49ab |

| NP 2 | 4.88a | 26.75a | 618.8a | 16.5a | 0.45a | |

| Mean | 5.11A | 39.62A | 901.9A | 24.6A | 0.47A | |

| NP 1 | Mean | 5.92 A | 73.92 A | 1656.1A | 46.33 A | 0.55 A |

| NP 2 | 6.03 A | 75.28 A | 1692.8 A | 47.08 A | 0.56 A | |

| Season/Soil parameter | pH | Al | K | Ca | Mg | P | B | S |

| Cmolc.kg-1 | mg.kg-1 | |||||||

| Wet season- May 2024 | ||||||||

| NPs | 0.2087 | 0.8855 | ˂0.0001* | 0.0053* | 0.054 | 0.0049* | ˂0.0001** | 0.2516 |

| Soil depths | ˂0.0001** | ˂0.0001** | ˂0.0001** | ˂0.0001** | ˂0.0001** | ˂0.0001** | 0.9337 | 0.0050* |

| Dry season-Sep 2024 | ||||||||

| NPs | 0.0018* | 0.0024* | ˂0.0001*** | 0.0127* | 0.0623 | 0.0029* | ˂0.0001* | 0.1407 |

| Soil depths | 0.1942 | 0.0646 | 0.0029* | 0.0812 | 0.2250 | 0.0001** | 0.2267 | 0.0582 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).