1. Introduction

In 2030, an estimated 20% of the United States population will be over the age of 65, and the percentage of older adults with burns has steadily increased over the last 5 years. The ABA national burn repository reported that adults aged 60 years and older represent more than 14% of patients admitted to U.S. burn centers [

1]. Older adults are at increased risk for burn injuries due to normal age-related physiological changes, including impaired sensation, decreased executive function, decreased reaction time, and impaired muscle performance [

2,

3]. Beyond the increased risk of sustaining an injury, older patients, particularly those older than 75 years, have higher rates of mortality, more in-hospital complications, loss of independence, and decreased quality of life. They are also more likely to be discharged to a Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF), hospice, or long-term care [

4,

5,

6]. Furthermore, the stress of hospitalization, surgical anesthesia, decreased nutrition, and post-operative pain are poorly tolerated by the older frail adult, which can lead to an accelerated decline in function and cognition during their admission [

7].

Although chronological age has been associated with worse outcomes, individuals physiologically age at different rates [

5,

10]; therefore, a measure of frailty is considered a more accurate index of physiologic reserve and speaks to an individual’s accumulation of health deficits over time [

8]. Frailty is increasingly recognized as an important construct with health implications for older adults, particularly those hospitalized in the acute care setting following geriatric trauma [

10]. Frailty has been linked to a variety of negative consequences, including fall risk, delirium, mortality, disability, and institutionalization [

12,

13]. In geriatric trauma, frailty has been shown to be a superior predictor over age alone [

9]. Romanowski and colleagues previously identified a link between pre-injury frailty assessments and mortality in elderly burn patients [

14]. Other studies have associated higher frailty scores with an increased likelihood of discharge to an SNF [

9]. However, few additional studies assist with prognostication regarding long-term recovery to facilitate education to families on realistic expectations, and no studies include long-term functional outcomes inclusive of frailty following a burn injury.

Appropriately assessing frailty allows clinicians to better predict outcomes and risks following a burn injury, which can lead to the development of specific interventions, clinical management, and targeted discharge planning strategies in the acute care setting. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the impact of frailty, as measured by the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), on discharge location from acute care and to describe trends in long-term function at least 6 months to one year following burn injury. We aim to assist burn care providers in making informed decisions regarding the patient’s plan of care and discussions of long-term outcome expectations.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patient Selection

A prospective cohort study was conducted at a single U.S. ABA-verified burn center from September 2019 to September 2021. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). All patients older than 55 years old who were admitted to the inpatient burn unit were prospectively screened and enrolled. Potential subjects were provided a fact sheet and reviewed the study expectations, providing verbal consent prior to participation.

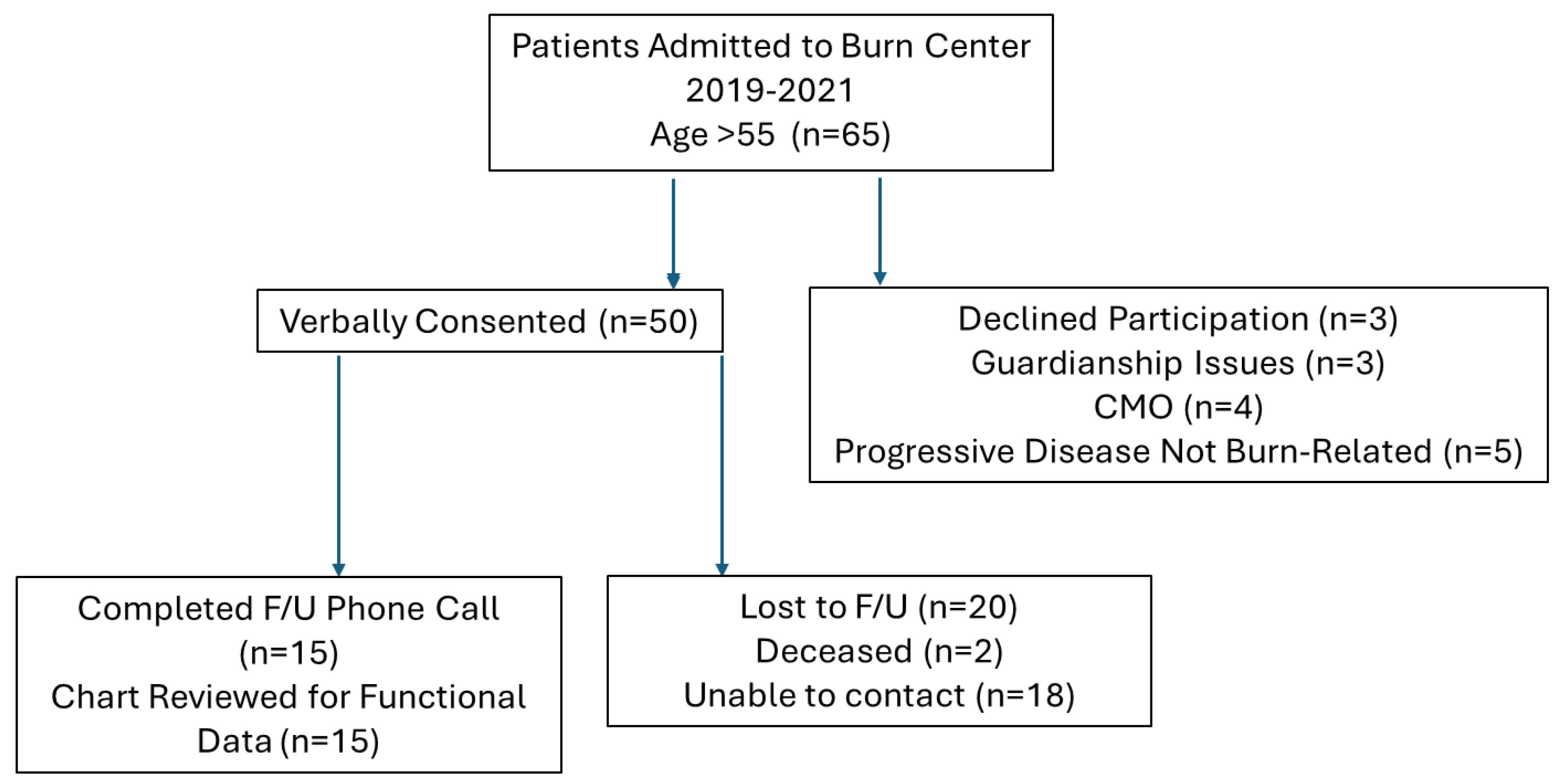

Exclusion criteria included terminal illness, progressive neurologic disease, and a non-survivable burn injury as determined by the burn service. A total of 65 patients met the age criteria. Of those, 50 provided verbal consent and were enrolled. A total of 30 subjects completed follow-up (

Figure 1).

Data Collection and Outcome Measures

Patient and injury demographics were collected via the electronic medical record, including age, gender, Total Body Surface Area (TBSA), and need for surgical intervention. The primary independent variable was frailty, assessed using the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging [

8]. The primary outcome measure was discharge disposition from acute hospitalization: Home, Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility (IRF), or Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF).

Secondary outcome measures focused on long-term function and were collected through a questionnaire and follow-up phone calls 6 months to 1.5 years following discharge. These included: Barthel Index, a 10-item questionnaire assessing a patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) and mobility tasks [

16]; and a functional questionnaire, a four-question survey developed for the study which included questions regarding the use of an assistive device (walker, cane, none), ability to access the community at least three times per week, current living environment, and social support.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables are presented as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (range) as appropriate. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the difference in CFS scores across the three discharge disposition groups. Predictors of discharge location were assessed using a regression model, including Barthel Index, Length of Stay, Age, CFS, TBSA, and social/functional factors. A P-value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Data from the 50 patients enrolled included an average age of 71 (SD 10.44) years, an average Total Body Surface Area (TBSA) of 7.44% (SD 13.22), and a mean Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) score of 3.4 (SD 1.65). The average Length of Stay (LOS) was 20 (SD 25) days. All patients included in the analysis underwent grafting for their burns. The full patient demographics are summarized in

Table 1.

Discharge disposition from acute care was categorized as Home (n=27), Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility (IRF) (n=13), or Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) (n=10). A clear distinction was observed in baseline characteristics based on discharge location (

Table 2).

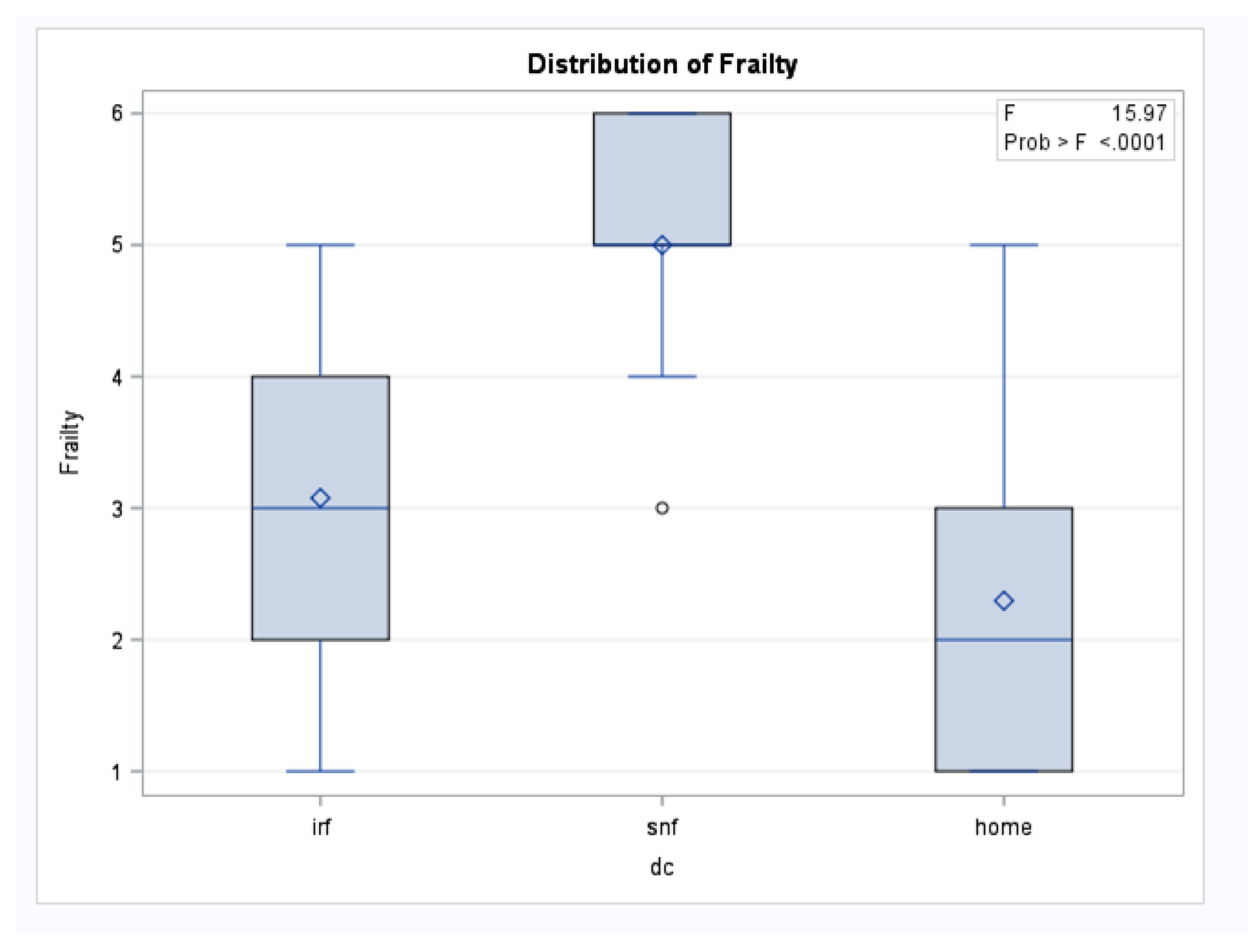

Patients who discharged to an SNF had a significantly higher mean CFS score (5.0, SD 0.94) compared to patients discharging to Home (2.2, SD 1.2) or IRF (3.0, SD 1.3). Notably, the SNF group was younger (average age 72.3 years) and had the smallest TBSA (3.56%) compared to the IRF group (average age 77 years, average TBSA 13.5%). The IRF group had the longest mean LOS at 37 (SD 39) days.

An ANOVA test demonstrated a statistically significant difference in mean frailty scores among the three discharge disposition groups (F = 15.97; P < .0001) (

Figure 2). A multivariable analysis was used to predict discharge location and the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) was found to be a significant predictor (t-value = -3.51; P = .0005). Other factors that were significant predictors included the Barthel Activity Index (t-value = 7.22; P < .0001), Age (t-value = -2.93; P = .0065), and the need for a device (t-value = -3.29; P = .0026). TBSA was not found to be a significant predictor of discharge location (P = .9923) (

Table 3).

Box-and-whisker plots show frailty scores across three discharge destinations: inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF), skilled nursing facility (SNF), and home. The box represents the interquartile range (25th to 75th percentile), with the horizontal line indicating the median. The diamond symbol indicates the mean frailty score, and circles represent statistical outliers. An ANOVA test demonstrated a statistically significant difference in frailty scores among the groups (F = 15.97; P < .0001).

Follow-up data was completed for 30 subjects. In this cohort, the average CFS was 2.89 (SD 1.5). The average Barthel Index Activity Score at the time of follow-up was 95/100 (Range 50-100). When asked about function, 90% (41 of 50 patients who answered the question) of patients stated that they had returned to their self-reported baseline and were living in their prior living environment by the follow-up time point.

A comparison of patients who did and did not return to their baseline was also performed (

Table 4). This revealed that patients who did not return to their baseline had a higher TBSA (22.2% vs. 8.6%) and a significantly higher CFS score (5.5 vs. 2.8).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is a powerful predictor of discharge disposition and long-term functional recovery in older adults with burn injury, surpassing the prognostic value of age and TBSA alone.

Our primary finding is the statistically significant difference in mean CFS scores across discharge groups. Patients discharging to a Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) had a mean CFS of 5.0, compared to 3.0 for those discharging to Inpatient Rehabilitation (IRF) and 2.2 for those going Home. This aligns with existing literature in geriatric trauma that shows frailty is a superior predictor of negative outcomes and institutionalization than age alone [

9,

12]. Critically, our data shows that the CFS score was the discriminating factor for institutional discharge, as the SNF group was younger (72.3 years) and had a smaller average TBSA (3.56%) than the IRF group (age 77 years, TBSA 13.5%). This highlights that a smaller injury can still lead to a poorer discharge outcome if the patient has reduced physiological reserve due to high frailty.

The fact that the majority of the cohort (90%) returned to baseline functioning and prior living environment at long-term follow-up (6 months to 1.5 years) is an encouraging finding, supporting a positive prognosis for most older adults who survive their initial burn injury. Patients who did not return to their baseline, however, had a significantly higher average CFS (5.5 vs. 2.8) and a higher average TBSA (22.2% vs. 8.6%) [

Table 4]. This result suggests that while most will recover, frailty identifies a vulnerable subgroup for whom functional goals should be adjusted early in the hospitalization.

The comprehensive assessment of frailty, which goes beyond chronological age, allows burn providers to set appropriate patient and family expectations regarding discharge from the hospital and return to functioning [

10]. Early conversations guided by a patient’s CFS score can facilitate proactive discharge planning, which may help to decrease length of stay, as delays often occur while arranging post-acute care [23,24]. Since a traumatic injury, such as a burn, can often serve as an inflection point for functional decline in the frail older adult, CFS can be used as a simple and effective tool to screen for those who may need a coordinated geriatric care model or specific interventions [25,26].

This study has several limitations. It was a single-center study, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. The overall sample size was small (n=50), and the follow-up rate was limited (n=30), which could introduce selection bias, particularly if the patients who were lost to follow-up had poorer outcomes. The Barthel Index score at baseline was not available, and long-term function was largely based on a self-reported return to baseline, which is a subjective measure. Finally, the four-question functional questionnaire was not a validated tool.

5. Conclusions

Frailty, as measured by the Clinical Frailty Scale, is a significant and superior predictor of both discharge disposition and long-term functional recovery in older adults following a burn injury. Patients with a higher frailty score were significantly more likely to discharge to a skilled nursing facility and less likely to return to their prior level of function, independent of age and TBSA. The integration of the Clinical Frailty Scale into the burn care protocol can aid burn providers in early prognostication, clinical management, and setting realistic outcome expectations for older adults and their families.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, writing: VD, EP, DA, MS, JS and JG; statistical analysis PN. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Massachusetts General Hospital.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Massachusetts General Hospital (Protocol #:2019P001699, 5/1/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Given the low-risk nature of the study, the Massachusetts General Hospital IRB waved the requirement for written consent. A verbal consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Massachusetts General Hospital and can be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nancy Goode, PT, DPT, and Kevin Schell, PT, DPT, for their contributions to data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFS |

Clinical Frailty Scale |

| TBSA |

Total Body Surface Area |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SNF |

Skilled Nursing Facility |

| IRF |

Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility |

| ADLs |

Activities of Daily Living |

References

- American Burn Association. National Burn Repository 2017 Update: Data from 2008–2017.

- Guccione A, Wong R, Avers D. Geriatric Physical Therapy. 3rd ed. Elsevier Mosby; 2012.

- Rani M, Schwacha M. Aging and the Pathogenic Response to Burn. Aging Dis. 2012, 3, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harrington D, Rogers A. Annual Burn Injury Summary. American Burn Association; 2023.

- Jeschke M, Pinto R, Costford S. Threshold Age and Burn Size Associated with Poor Outcomes in the Elderly after Burn Injury. Burns. 2016, 42, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein M, Lezotte D, Heltsh S, et al. Functional and Psychosocial Outcomes of Older Adults after Burn Injury: Results From a Multicenter Database of Severe Burn Injury. J Burn Care Res. 2011, 32, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galet C, Lawrence K, Lilienthal D, et al. Admission Frailty Scores are Associated with Increased Risk of Acute Respiratory Failure and Mortality in Burn Patients 50 and Older. J Burn Care Res. 2023, 44, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung A, Haas B, Ringer TJ, et al. Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale: Does it Predict Adverse Outcomes Among Geriatric Trauma Patients? J Am Coll Surg. 2017, 225, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellal J, Viraj P, Bardiya Z. Superiority of Frailty over Age in Predicting Outcomes Among Geriatric Trauma Patients. JAMA Surg. 2014, 149, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqarni A, Gladman J, Obasi A, Ollivere B. Does Frailty Status Predict Outcome in Major Trauma in Older People: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2023, 52, I–II. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin HS, McBride RL, Hubbard RE. Frailty and Anesthesia—Risks During and Post-Surgery. Local Reg Anesth, 2018; 11, 61–73. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, G. Frailty as a Predictor of Nursing Home Placement Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2018, 41, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeiren S, Vella-Azzopardi R, Beckwée D, et al. Frailty and the Prediction of Negative Health Outcomes: a Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016, 17, 1163. [Google Scholar]

- Romanowski KS, Tuffaha S, Hustedt J, et al. Preinjury Frailty Predicts Mortality in Elderly Burn Patients. Burns. 2017, 43, 953–958. [Google Scholar]

- Barthel Index. This reference is assumed to be the original publication of the Barthel Index scale.

- Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: Interactions and Outcomes Across the Care Continuum. J Aging Health, 2021; 33, 469–481. [CrossRef]

- Church S, Rogers E, Rockwood K, Theou O. A Scoping Review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar A, Dhar M, Agarwal M, et al. Predictors of Frailty in the Elderly Population: a Cross-Sectional Study at a Tertiary Care Center. Cureus. 2022, 14, e30656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).