1. Introduction

Frailty has a significant impact on clinical practice and global socio-health policies, influencing hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality [

1]. It is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [

2], potentially affecting 25.8% of patients with heart failure and 32% of those with coronary syndrome [

3,

4].

Spain is one of the countries with the highest aging population worldwide and, consequently, has a high mortality rate associated with CVD [

5].

Frailty in older adults over 80 years with coronary syndrome has been independently associated with mortality (HR: 1.96; p < 0.001) [

6]. Additionally, in older adults (≥65 years) diagnosed with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS), invasive coronary angiography has been linked with myocardial infarction, urgent coronary revascularization, increased bleeding, and all-cause mortality within one year of receiving healthcare (HR: 2.79; 95%CI: 1.28–6.08; p = 0.01) [

7].

The incidence of patients with frailty and CVD requiring unplanned hospital readmission can reach up to 34.4% (p = 0.02) [

7]. A higher risk of readmission has been established compared to robust patients (HR: 2.32; 95% CI: 1.93–2.80, p < 0.001; HR: 1.73; 95% CI: 1.06–2.82, p < 0.028) [

3,

4].

Survival analysis results differ by sex. A community cohort study of individuals over 60 years showed that the degree of frailty influenced mortality risk more acutely in men than in women (HR = 1.171; 95%CI: 1.139–1.249 vs HR = 1.119; 95%CI: 1.249) [

8]. Among men diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome, pre-frailty and frailty have been associated with increased mortality (HR: 3.47; 95% CI: 1.22–9.89; HR: 3.19; 95% CI: 1.08–9.43), while in women, this association has only been confirmed in frail individuals compared to robust and pre-frail ones (HR: 5.68; 95% CI: 1.91–16.18) [

9].

Frailty is a multifactorial concept that includes phenotypic aspects and cumulative deficits, making it difficult to generalize therapeutic strategies [

10,

11,

12].

The FRAIL scale is commonly used for its speed and simplicity in assessing frailty across five domains: fatigue, resistance, ambulation, comorbidity, and weight loss [

12]. This scale includes four questions related to cardiovascular health [

13]. It has been used to evaluate 30-day postoperative prognosis in orthopedic patients and the risk of unplanned hospital readmission in patients with NSTE-ACS [

9,

14].

Survival studies often focus on time to unplanned hospital readmission and mortality. Hospitalization is a major stressor that can disrupt the homeostasis of frail patients [

15]. A six-month follow-up by Lorente et al. on elderly patients with NSTE-ACS suggests evaluating other factors beyond the main clinical diagnosis [

16].

One predictor of mortality after hospitalization in older adults is functional dependency associated with frailty, age, and sex (HR = 0.94; 95%CI: 0.89–0.98; p < 0.01) [

17]. Nutrition is also essential in comprehensive geriatric assessment, with malnutrition being strongly associated with frailty (OR = 3.736; 95%CI: 2.488–5.610; p < 0.001) [

18]. The metabolic changes during aging are exacerbated by frailty and are closely linked to diabetes mellitus [

19]. Other blood biomarkers such as hemoglobin and albumin have been identified as predictors of mortality in older adults, relating to anemia and hypoalbuminemia respectively (HR = 8.05; p < 0.001) [

20].

Given the strong relationship between frailty and comorbidities, it is essential to consider other aspects of healthcare in survival analyses.

Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the relationship between frailty identified by the FRAIL scale and the survival of frail older adults hospitalized with heart disease. The survival event was defined as the healthcare received after discharge from the index admission, including the first cardiology follow-up, other medical consultations, emergency department visits, unplanned hospital readmission, and death during the 365 days following discharge.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Population, and Sample

A cohort observational study was conducted on patients aged ≥60 years admitted to a cardiology hospitalization unit between March 2022 and April 2024 at a tertiary-level hospital within the public healthcare network of Castile & León, Spain.

Selected patients had a minimum hospital stay of 3 days. Patients admitted for interventional cardiology procedures with a hospital stay shorter than 3 days were excluded. Patients from healthcare areas outside the hospital’s coverage or those for whom follow-up could not be completed were also excluded.

The participants of the study were selected through a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method in the cardiology unit, being consecutively recruited as they were admitted to the unit.

The study is reported according to STROBE reporting guidelines for observational research.

2.1.1. Sample size

A minimum sample of 28 patients in the frail group and 57 in the non-frail group was sufficient to detect a statistically significant effect between two independent censored groups using Log-rank survival analysis, with 80% power, a significance level of p < 0.05, a readmission incidence rate of 0.344 [

7], a ratio between frail and robust group sizes of 0.47, and a hazard ratio (HR) equal to or greater than 2.32 for unplanned hospital readmission, assuming a 5% loss to follow-up [

3].

2.2. Variables

Sociodemographic variables

Collected variables included age (in years), sex (biological sex identified according to the sex assigned at birth), and the clinical diagnosis at admission (arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular disease, and infectious endocarditis).

Clinical variables

Clinical parameters included body mass index (BMI, kg/m²) measured using a calibrated scale and stadiometer, abdominal circumference (cm) using a millimetric tape, degree of dependency using the Barthel Index (independent = 100 points; mild dependence = 91–99; moderate dependence = 61–90) [

21], presence of diabetes mellitus (Yes/No), length of hospital stay (days), previous readmissions (Yes/No), presence of dyspnea (Yes/No), and blood biomarkers: total cholesterol (mg/dL), HDL cholesterol (mg/dL), LDL cholesterol (mg/dL), hemoglobin (g/dL), albumin (g/dL), and serum creatinine (mg/dL).

Frailty identification

Frailty status was assessed using the FRAIL scale, which consists of five domains evaluated by five questions [

12]:

Are you feeling fatigued?

Are you unable to climb one flight of stairs?

Are you unable to walk one block?

Do you have more than five illnesses?

Have you lost more than 5% of your weight in the past six months?

Patients were categorized into three groups: robust (no positive domains), pre-frail (1 or 2 positive domains), and frail (3 or more positive domains).

Dependent variables

The following time-based outcomes were measured (in days): time to first follow-up cardiology visit, time to first medical visit for non-cardiac reasons, time to first emergency room visit, time to unplanned hospital readmission, and time to death.

2.3. Procedures

One week prior to the start of the study, a one-hour training session was provided to the cardiology unit nurses involved in the study. The session covered the administration of the frailty assessment scale to minimize variability.

Patient recruitment was carried out consecutively over the two-year study period, upon admission to the cardiology unit. After obtaining informed consent, data collection was performed within the first three days of admission. This strategy ensured data uniformity before any potential clinical deterioration. During this period, nurses administered the FRAIL scale and collected anthropometric measurements. The remaining variables were obtained from the patient´s medical records.

Post-discharge follow-up of healthcare utilization was conducted at one month, three months, six months, and one year using the patient´s electronic medical records.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

Participant anonymity and data confidentiality were safeguarded using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software (

https://project-redcap.org/), in compliance with European Regulation 2016/679 of the European Parliament and Council of April 27, 2016, and Spanish Organic Law 3/2018 of December 5, on Personal Data Protection and Digital Rights Guarantee. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Valladolid Ethics Committee for Research with medicinal products (ECRmp) involving humans under the reference code PI-20-1612 on 23 January 2020.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, kurtosis, and skewness. Quantitative variables were presented as means and standard deviations (SD), while categorical variables were expressed as frequency distributions. Quantitative variables were compared using Student’s t-test, and categorical variables using Pearson’s chi-squared test. The homogeneity of variance was verified using Levene’s test.

Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves, with result sensitivity reinforced through the Mantel-Cox Log-rank test. To estimate the hazard rate (HR), univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used. Additionally, a backward stepwise multivariate model was applied to refine the models, retaining only those variables with statistically significant predictive value. A 95% confidence interval and a significance level of p < 0.05 were applied.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM® SPSS® Statistics v.29 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

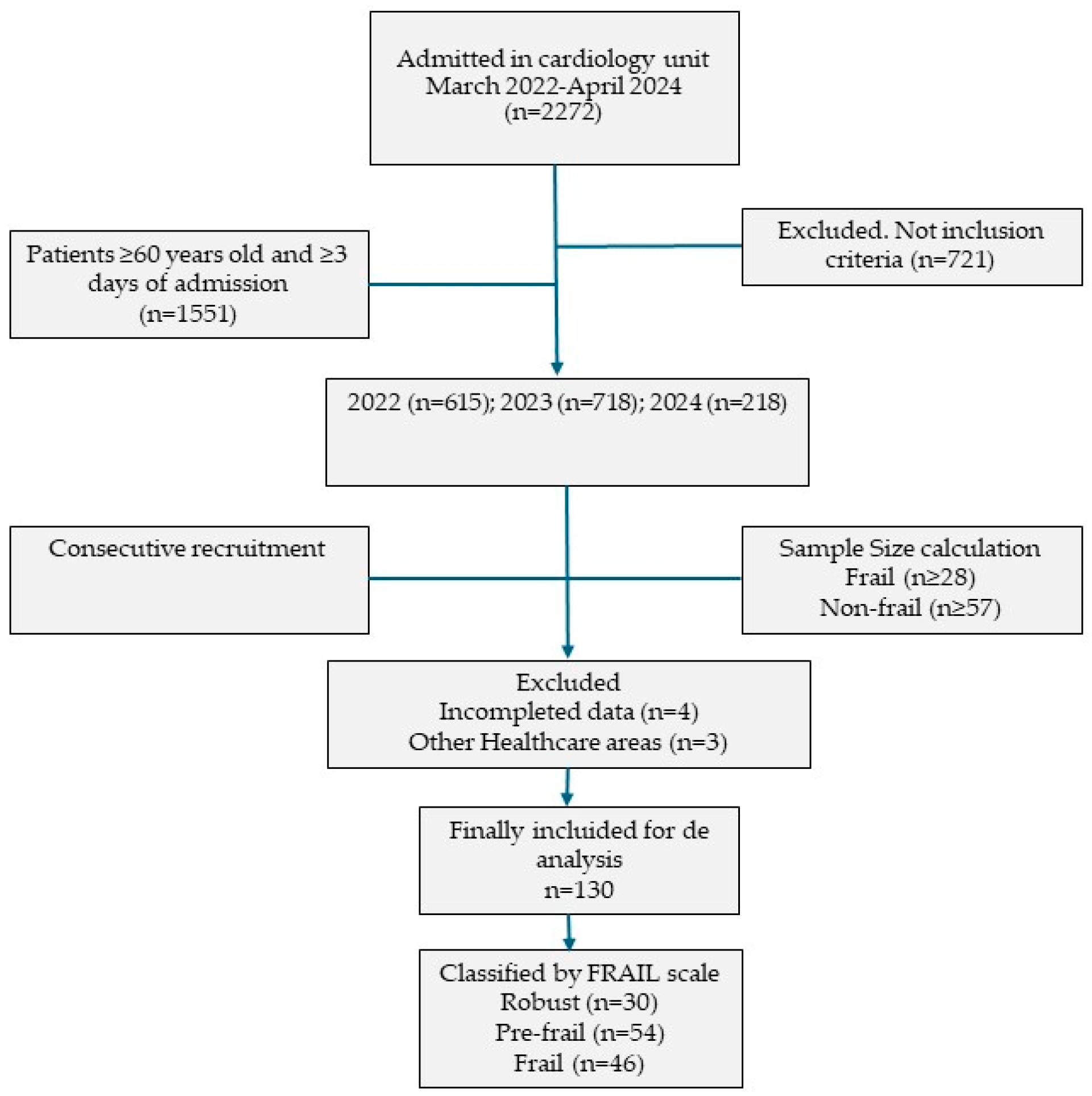

The final sample consisted of 137 patients. Of these, 4 were excluded due to incomplete data and 3 because they belonged to other healthcare areas during follow-up, as shown in the flow diagram in

Figure 1.

Among the final 130 older adult participants, 68.46% were men and 31.54% were women. The mean age was 72.98 years (SD = 7.67). Frailty was identified in 35.38% of the patients. The mean length of hospital stay was 8.84 days (SD = 5.68), significantly longer in frail patients (p = 0.040). The mean Barthel Index score was 96.00 (SD = 8.39), with significantly higher scores among robust patients (p = 0.003). Regarding nutritional status, the average BMI was similar across frailty groups. No statistically significant differences were found in blood analytical values between frailty groups. Cholesterol levels were similar across all groups. Albumin levels were lower in the frailty group compared to robust patients (3.73 ± 0.72 g/dL vs. 4.14 ± 1.50 g/dL), as were mean hemoglobin levels (13.48 ± 2.26 g/dL vs. 14.13 ± 1.63 g/dL). However, creatinine levels were higher in the frail group (1.33 ± 1.26 g/dL vs. 0.95 ± 0.22 g/dL) (

Table 1).

The most frequent diagnosis was coronary artery disease (59.23%). Diabetes Mellitus was diagnosed in 35.38% of the patients, 28.46% presented with dyspnea upon admission, and 14.62% were experiencing a readmission to the cardiology unit.

Among the patients identified as frail, 30.43% had experienced a readmission (p = 0.039), a significantly higher percentage than robust patients (6.67%). Frail patients also had a higher prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus (43.48% vs. 13.33%; p = 0.017).

When analyzed by sex, the average abdominal circumference was greater in men (104.60 cm ± 10.98 vs. 98.41 cm ± 16.28; p = 0.0012), but the average BMI was higher in women with pre-frailty. Robust men showed a near-complete level of independence compared to frail men (p = 0.015). Frail women had a higher degree of dependence than the other two groups and even more than frail men, although this difference was not statistically significant. Regarding blood biomarkers, no statistically significant differences were found between men and women across the frailty, pre-frailty, and robust groups. However, among men, there were minimal differences in the average values of each biomarker except for hemoglobin. Among women, robust individuals showed higher mean values in total cholesterol and HDL. The lowest HDL cholesterol levels were recorded in frail men. No significant differences were found in LDL levels. The lowest hemoglobin levels were observed in frail women (12.65 ± 1.76 g/dL). In both sexes, hospital stay was longer in frail patients, with the longest average observed in frail men (

Table 1).

3.1. Survival Analysis

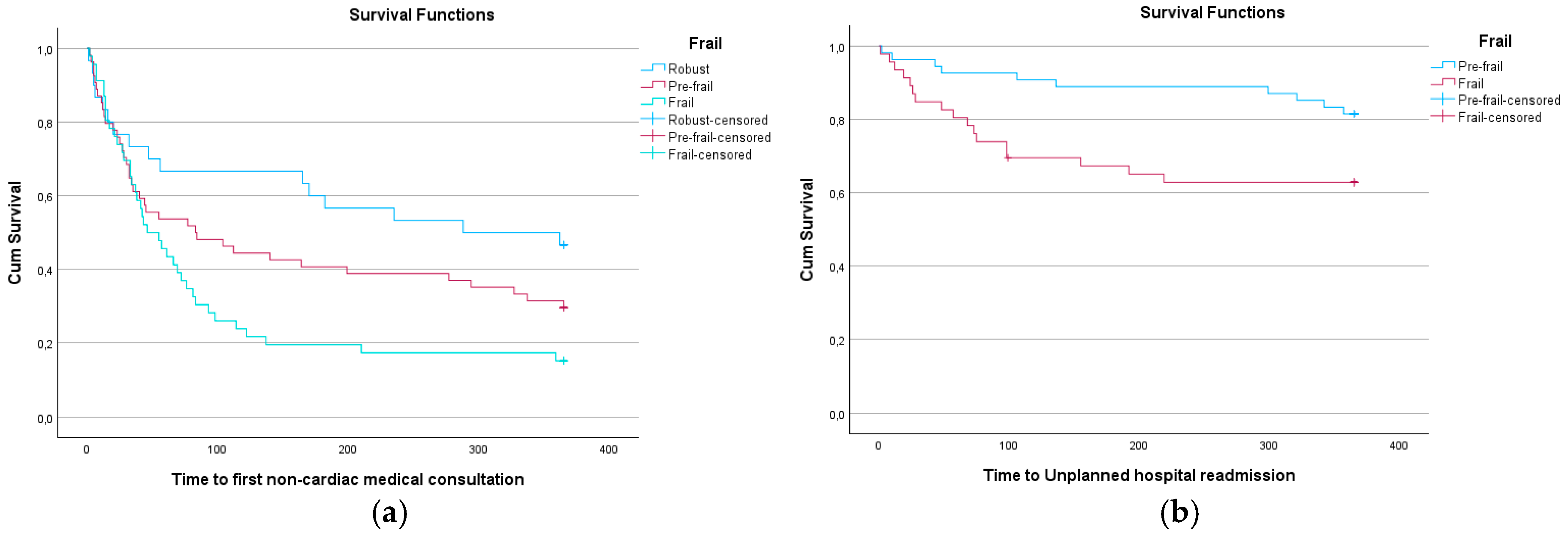

After analyzing the survival times for the first cardiology follow-up visit, first consultation for other reasons, emergency department visit, and new hospital admission, it was observed that frail patients generally had shorter average times compared to the other two patient groups. The difference among groups in the time to the first consultation for non-cardiac reasons was statistically significant, and the difference in time to new hospital admission was close to statistical significance. Only two patients from the study sample died within the 365-day follow-up period post-discharge: one belonged to the frailty group and the other to the pre-frailty group (

Table 2).

At 359 days, frail patients had a 22.50% probability of not requiring another consultation, compared to 26.90% in pre-frail patients at 365 days, and 31.90% in robust patients (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). At 219 days, frail patients had a 62.80% probability of not needing a new hospital admission, while at 299 days, pre-frail patients had an 87.00% probability. This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.025) (

Figure 2 and

Table 3).

3.2. Univariate Analysis of Frailty Groups and Survival Events

Cox regression analysis showed that frail patients, compared to robust and pre-frail patients, required a medical consultation for non-cardiology reasons 1.513 times sooner (p = 0.004), and 2.386 times sooner than robust patients within the first 365 days post-discharge. When comparing frail to pre-frail patients, frail individuals showed a lower risk of hospital readmission. When grouping robust and pre-frail patients against those with frailty, survival times across all variables were consistently lower in the frail group and the speed to reach the analyzed event was greater in the frail group than in the combined group of robust and pre-frail individuals, although this was not statistically significant for emergency care (

Table 4).

3.3. Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Sociodemographic and Clinical Variables about Frailty Status and Survival Events

In the univariate analysis of sociodemographic and clinical variables, although older age suggested a greater risk of the analyzed events, the results were not statistically significant—nor was frailty status in general. Similarly, no relationship was found between survival time for the four defined outcomes and sex.

3.3.1. First Cardiology Consultation

Factors associated with this event included lower levels of albumin (HR = 0.644; 95% CI = 0.459–0.905; p = 0.011), lower hemoglobin (HR = 0.856; 95% CI = 0.770–0.951; p = 0.004), and longer hospital stay (HR = 1.079; 95% CI = 1.037–1.122; p < 0.01). In the multivariate analysis, hemoglobin remained an independent predictor (HR = 0.808; 95% CI = 0.686–0.952; p = 0.011), along with total cholesterol (HR = 0.980; 95% CI = 0.961–0.999; p = 0.037), higher HDL cholesterol levels (HR = 1.029; 95% CI = 1.002–1.058; p = 0.036), LDL cholesterol (HR = 1.022; 95% CI = 1.002–1.042; p = 0.030), and longer hospital stay (HR = 1.085; 95% CI = 1.031–1.141; p = 0.002) (

Table 5).

3.3.2. First Medical Consultation for Other Reasons

In the univariate model, frail patients were 1.513 times more likely to require a medical consultation for non-cardiology reasons after hospital discharge compared to robust patients (HR = 1.513; 95% CI = 1.143–2.003; p = 0.004), similarly, patients with diabetes (HR = 1.719; 95% CI: 1.134–2.605; p = 0.011), those with lower levels of hemoglobin (HR = 0.885; 95% CI: 0.796–0.984; p = 0.024), and those with lower LDL cholesterol (HR = 0.993; 95% CI: 0.987–0.999; p = 0.034) were more likely to require a non-cardiology medical consultation. However, in the multivariate model, none of the variables were identified as independent predictors for the first consultation for other reasons. Nevertheless, frailty continued to show a trend suggesting a potential relationship with this event (HR = 1.473; 95% CI: 0.971–2.232; p = 0.068) (

Table 5).

3.3.3. Emergency Care

Patients who had longer hospital stays were 1.055 times more likely to require emergency care post-discharge for each additional day of hospitalization (p = 0.011). This relationship remained in the multivariate analysis (HR = 1.083; 95% CI: 1.018–1.153; p = 0.011), along with higher albumin levels, which approached statistical significance (p = 0.069) (

Table 5).

3.3.4. Unplanned Hospital Readmission

In the univariate analysis, the following variables were statistically significant: the primary diagnosis at discharge indicated a higher risk of unplanned readmission (HR = 1.550; 95% CI: 1.061–2.265; p = 0.023), the presence of diabetes mellitus (HR = 2.394; 95% CI: 1.220–4.697; p = 0.011), and a higher Barthel Index score at discharge, which decreased this risk (HR = 0.970; 95% CI: 0.942–0.999; p=0,040) and yet, for each additional day of hospital stay, the risk increased by 1.086 times (HR = 1.086; 95% CI: 1.034–1.140; p < 0.001). In the multivariate analysis, only LDL cholesterol showed a statistically significant association as an independent predictive factor for unplanned hospital readmission (HR = 1.038; 95% CI: 1.006–1.071; p = 0.021) (

Table 5).

3.4. Multivariate Backward Stepwise Analysis

3.4.1. First Cardiology Consultation

Frailty could not be identified as an independent predictive factor. To assess model sensitivity, a multivariate backward stepwise analysis was performed. Regarding the first cardiology consultation, 13 steps were required while maintaining overall statistical significance of the models (step 1; p = 0.02). Although frail patients tended to require the first cardiology consultation sooner, this was not statistically significant from step 1 (HR = 1.934; 95% CI = 0.844–4.429; p = 0.119), and frailty was removed in step 7 (χ² = 2.18; df = 2; p = 0.336), indicating that its adjusted effect was not statistically significant when controlled for covariates.

The independent predictive factors that remained were: hemoglobin (HR = 0.807; 95% CI = 0.686–0.952; p = 0.011), total cholesterol (HR = 0.979; 95% CI = 0.961–0.998; p = 0.032), HDL cholesterol (HR = 1.029; 95% CI = 1.002–1.058; p = 0.034), LDL cholesterol (HR = 1.023; 95% CI = 1.003–1.043; p = 0.026), and length of hospital stay (HR = 1.086; 95% CI = 1.033–1.142; p = 0.001). In the final step (13), the independent predictors were: age (HR = 1.036; 95% CI = 1.002–1.072), and length of hospital stay (HR = 1.078; 95% CI = 1.029–1.128; p = 0.001). Higher Barthel Index scores (HR = 1.038; 95% CI = 0.997–1.082; p = 0.073), lower albumin levels (HR = 0.704; 95% CI = 0.479–1.034; p = 0.074), and lower hemoglobin levels (HR = 0.894; 95% CI = 0.793–1.007; p = 0.065) showed trends toward statistical significance in relation to the first cardiology consultation.

3.4.2. First Medical Consultation for Other Reasons

In this model, frailty was maintained as a significant predictor. In the final step (step 16; χ² = 10.59; df = 3; p = 0.014), it showed a significant association with a higher probability of requiring a medical consultation for reasons other than cardiology (HR = 2.329; 95% CI: 1.163–4.664; p = 0.017). None of the other covariates showed statistically significant relationships

3.4.3. Emergency Care

In the analysis for emergency care, frailty did not remain a significant variable in the final steps of the model. In the first step, it showed a trend (HR = 1.383; 95% CI: 0.541–3.539; p = 0.499), but it was not retained. The variables that remained statistically significant as independent predictors in step 12 (χ² = 15.71; df = 6; p = 0.015) were: albumin (HR = 1.327; 95% CI: 1.022–1.723; p = 0.033), BMI (HR = 1.201; 95% CI: 1.048–1.376; p = 0.008), abdominal circumference (HR = 0.949; 95% CI: 0.911–0.989; p = 0.012), length of hospital stay (HR = 1.084; 95% CI: 1.033–1.138; p = 0.001). Total cholesterol (HR = 0.993; 95% CI: 0.986–1.000; p = 0.059) and HDL cholesterol (HR = 1.022; 95% CI: 0.998–1.047; p=0.074) showed trends toward significance.

3.4.4. Unplanned Hospital Readmission

In the final model for unplanned hospital readmission, frailty also did not reach statistical significance (HR = 1.009; 95% CI: 0.291–3.496; p = 0.989). Statistical significance of the models was maintained from step 1 (χ² = 34.099; df = 18; p = 0.012), where only total cholesterol (HR = 0.966; 95% CI: 0.937–0.996; p = 0.027) and LDL cholesterol (HR = 1.046; 95% CI: 1.012–1.081; p = 0.007) behaved as independent predictive factors. However, in step 16, the following were also identified as independent predictors: Diabetes Mellitus (HR = 2.292; 95% CI: 1.087–4.833; p = 0.029), and previous hospital stay duration (HR = 1.081; 95% CI: 1.025–1.140; p = 0.004).

4. Discussion

The results obtained show that the presence of frailty in older adults hospitalized with cardiovascular disease (CVD) is associated with a less favorable clinical profile, with greater care needs and follow-up requirements after discharge from a cardiology unit compared to robust and pre-frail patients. It is worth highlighting the high prevalence of patients with pre-frailty. These findings are in line with scientific literature that identifies frailty as an independent risk predictor for adverse events in older adults, generating a significant impact on the health and social care system [

22].

The prevalence of frailty (35.38%) is within the range identified by other authors for patients with CVD [

3,

4,

7], which reinforces the representativeness of the sample. As described previously, frail patients presented a higher average age than robust patients and showed poorer functional scores according to the Barthel Index, confirming the association between aging (HR = 1.05; 95% CI = 1.01–1.09; p = 0.011), the degree of functional dependence (HR = 120; 95% CI = 7.7–1700; p < 0.001), and frailty, without overlooking the importance of pre-frailty status [

23,

24].

Frail patients had a longer average hospital stay than robust patients, suggesting that these individuals undergo more complex clinical processes or have a lower recovery capacity than non-frail or pre-frail individuals. Moreover, serum creatinine levels were higher in these patients, which may be related to greater renal function impairment—a condition also linked to frailty and chronic inflammatory states [

25]. It is also worth noting the higher proportion of patients with Diabetes Mellitus among the frail group compared to the robust group, as well as their higher rate of readmissions, which may be related to the increased burden of chronic disease and comorbidities. This could lead to a disruption in the homeostasis of these individuals, raising the risk of clinical decompensation, such as vascular complications (pre-frail: HR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.02–1.18; frail: HR = 1.52; 95% CI = 1.36–1.69), and consequently, readmissions as described by Wu et al. [

26].

In the survival analyses, frail patients showed a significantly shorter survival time until the first consultation for reasons other than the initial cardiology admission, and a trend toward a shorter time until requiring a new hospital readmission—results that align with other studies [

3,

4]. These findings were confirmed through Cox regression analysis, which identified frailty as an independent predictive factor. Frail patients required a medical consultation 2.386 times faster than robust patients, indicating a higher demand for healthcare services [

4]. On the other hand, a higher score on the Barthel Index acted as a protective factor against unplanned readmission, underscoring the importance of the degree of functional dependence as a prognostic and predictive factor of clinical evolution at hospital discharge, and its relationship with frailty (t = 6.27; p < 0.001) [

24].

In the resulting multivariate models, hemoglobin levels, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and length of hospital stay in the cardiology unit emerged as independent predictive factors for some outcomes. In our study, the mean levels of total cholesterol and LDL were lower in robust patients, consistent with findings by Liang et al. (cholesterol: 4.12 ± 1.12 mmol/L vs. 4.57 ± 1.09 mmol/L; p = 0.012; LDL: 2.73 ± 0.92 mmol/L vs. 3.07 ± 0.86 mmol/L; p = 0.016) [

27]. Hemoglobin is a nutritional marker, with low levels indicating potential malnutrition, similar to hypoalbuminemia [

20]. These factors reflect nutritional and metabolic domains that are gaining increasing relevance in comprehensive geriatric assessment. The FRAIL scale captures these aspects tangentially in its fifth domain, which inquires about unintentional weight loss over the past six months. Malnutrition risk has been identified as a predictor of frailty and three-year mortality (OR = 1.685; 95% CI = 1.474–2.914; p < 0.01) [

18]. These findings suggest that frail patients may exhibit greater multisystemic involvement, aligning with the holistic concept of frailty.

Although sex-related differences were not observed in our results, contrary to previous studies [

9], women exhibited a higher degree of dependency compared to men. This may reflect a clear disparity in functional performance, underscoring the need for focused attention on frail women in rehabilitation and functional follow-up programs. Shi et al. identified a greater accumulation of deficits in women, whereas men had a higher mortality risk [

8].

Although frailty could not be identified as an independent predictive factor in all multivariate models, a trend toward faster healthcare utilization was evident, reinforcing its prognostic value in older adults hospitalized for cardiovascular disease. The analysis revealed other clinically relevant predictors of post-discharge outcomes: low hemoglobin and total cholesterol levels, longer hospital stays, and anthropometric indicators such as BMI and abdominal circumference. These functional, nutritional, and metabolic factors should be jointly considered in more complex predictive models that incorporate frailty as an additional dimension, especially given its dynamic nature and the tendency for progression toward frailty. This supports the need for comprehensive assessment and individualized therapeutic management in this patient population [

28].

In this regard, it is plausible that frail patients, given their poorer baseline condition, require increased healthcare services. However, it is equally plausible that suboptimal or insufficient care may exacerbate frailty, suggesting a bidirectional relationship that warrants further exploration in future studies.

Regarding the first cardiology follow-up visit, although frail patients showed a shorter time to this consultation, this association did not persist in the final multivariate model. Instead, longer hospital stays, and lower levels of hemoglobin and total cholesterol were the main determinants of the timing of cardiology follow-up. Age was also included in the final model. As described in previous studies, frailty is closely associated with advanced age [

29,

30], indicating that clinical complexity at discharge, older age, and metabolic status are key elements in planning post-discharge care continuity.

In contrast to the previous outcome, frailty was confirmed as an independent predictor for the need for medical consultations unrelated to the initial cardiology admission. Frail patients were more than twice as likely to require non-cardiology specialist care post-discharge, reflecting higher clinical vulnerability and potential decompensation of comorbid conditions. This highlights the utility of frailty screening to anticipate broader healthcare needs beyond the cardiology scope [

14,

23].

About emergency care, frailty was not retained as an independent predictor in the multivariate analysis. However, BMI, abdominal circumference, and length of hospital stay were significant factors, suggesting these clinical parameters may influence emergency care needs. Despite this, frailty remains a key marker of vulnerability that should not be overlooked [

31].

As for unplanned hospital readmissions, frailty was also not a predictor in the adjusted model. Instead, diabetes mellitus and length of hospital stay emerged as significant factors. It is plausible that an overlap between frailty and comorbidities may account for the loss of statistical significance in the final model. Nevertheless, frailty remains a valuable tool for identifying at-risk patients, particularly when combined with other predictors [

32].

A notable aspect is the low mortality rate observed in this cohort, which limits the evaluation of frailty as a predictor of death within 365 days post-discharge from the cardiology unit. This outcome may be attributable to the inclusion of patients with greater clinical stability or lower complexity at discharge, potentially introducing selection bias.

This study provides relevant evidence regarding the prognostic value of the FRAIL scale in older adults hospitalized with CVD. The tool proved useful in anticipating healthcare needs following discharge from a cardiology unit, particularly in predicting the need for non-cardiology medical consultations. It is also noteworthy that a substantial proportion of patients were identified as pre-frail, a group that occupies a potentially reversible stage. Given the dynamic nature of frailty, it would be advisable to assess frailty status at multiple points post-discharge to monitor its progression and adapt therapeutic interventions accordingly, with the aim of implementing preventive strategies to avoid progression to full frailty.

The study was conducted in a single cardiology unit, and the inclusion criteria were very strict, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other healthcare settings. Sensitivity analyses were not performed; however, several subgroup analyses based on frailty status were conducted. The handling of missing data was not formally described, although the loss to follow-up rate was low. Frailty was assessed within the first three days of admission, which may reduce variability but might not capture subsequent clinical changes. The low mortality rate observed in this cohort limited the ability to detect differences in this outcome. Nonetheless, the consecutive recruitment over a two-year period, the broad inclusion criteria, and the thorough follow-up strengthen the robustness of the findings. Rather than undermining the results, these limitations underscore the need to replicate this type of study in other contexts and with more diverse samples to further strengthen the evidence on the prognostic role of frailty in older adults hospitalized for cardiovascular disease.

5. Conclusions

The FRAIL scale can moderately predict 365-day post-discharge risk, with special attention warranted for pre-frail patients. In hospitalized older adults with cardiovascular disease, frailty is linked to poorer functional status and greater comorbidity burden, requiring longer hospital stays and increased post-discharge healthcare utilization, including medical consultations, readmissions, and a faster onset of clinical events. This scale is a valuable clinical tool for identifying vulnerable patients. Functional status, nutritional and metabolic biomarkers (such as hemoglobin, albumin, total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL), and length of hospital stay were key determinants of post-discharge care requirements.

These findings reinforce the importance of early and systematic frailty assessment upon hospital admission in cardiology units, in order to tailor therapeutic interventions, improve the management of frailty progression, and potentially anticipate post-discharge complications. Functional dependency, hemoglobin, albumin, and lipid profile values should be considered in discharge predictive models and used to guide healthcare planning and optimize resource allocation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N. R-G. and M.L; methodology, N.R-G., M.F-C., B.M-G; validation, N.R-G., M.L., MJ.C., and JA.SR.; formal analysis, N.R-G., B.M-G., M. F-C.; investigation, N.R-G; resources, N.R-G, M.L., MJ. C.; data curation, N.R-G; writing—original draft preparation, N.R-G; writing—review and editing, N.R-G; M.L., MJ. C., M.F-C., B.M-G., E.R-G., JA. SR; visualization, N. R-G., M.L., MJ. C., M.F-C., B.M-G., E.R-G., JA. SR.; supervision, M.L; project administration, M.L., MJ.C., and JA.SR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of de Investigación con medicamentos del área de salud Valladolid Este (protocol code PI-20-1612 and 23 de enero de 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted in alignment with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for observational research [

33].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACS |

Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular Disease |

| FRAIL |

Fatige, Resistence, Ambulation, Illnesses, Loss of weight |

| HDL |

High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| LDL |

Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| HR |

Hazard Rate |

| NSTE-ACS |

Non-ST Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

References

- Hoogendijk, E.O.; Afilalo, J.; Ensrud, K.E.; et al. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet 2019, 394, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, Q.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; et al. Prognostic value of frailty in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Cai, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. Frailty as a predictor of all-cause mortality and readmission in older patients with acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2020, 132, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.M.; Zheng, P.P.; Liang, Y.D.; et al. Predicting non-elective hospital readmission or death using a composite assessment of cognitive and physical frailty in elderly inpatients with cardiovascular disease. BMC Geriatr 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, H.; Beatriz, P.-G. Global rounds: cardiovascular health, disease, and Care in Spain. Circulation 2019, 140, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Queraltó, O.; Formiga, F.; López-Palop, R.; et al. FRAIL Scale also Predicts Long-Term Outcomes in Older Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020, 21, 683–687e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, J.; Qiu, W.; Gu, S.; et al. One-year clinical outcomes in older patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome undergoing coronary angiography: An analysis of the ICON1 study. Int J Cardiol 2019, 274, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Tao, Y.; Meng, L.; et al. Frailty Status Among the Elderly of Different Genders and the Death Risk: A Follow-Up Study. Front Med; 8. Epub ahead of print 2021. [CrossRef]

- Vicent, L.; Ariza-Solé, A.; Alegre, O.; et al. Octogenarian women with acute coronary syndrome present frailty and readmissions more frequently than men. Eur Hear J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2019, 8, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in Older Adults. N Engl J Med 2024, 391, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Cohen, A.A.; Xue, Q.-L.; et al. The physical frailty syndrome as a transition from homeostatic symphony to cacophony. Nat Aging 2021, 1, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Miller, D.K. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged african americans. J Nutr Heal Aging 2012, 16, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, A.B.; Gottdiener, J.S.; McBurnie, M.A.; et al. Associations of subclinical cardiovascular disease with frailty. Journals Gerontol - Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001, 56, M158–M166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleason, L.J.; Benton, E.A.; Alvarez-Nebreda, M.L.; et al. FRAIL Questionnaire Screening Tool and Short-Term Outcomes in Geriatric Fracture Patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017, 18, 1082–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xujiao, C.; Genxiang, M.; XLeng, S. Frailty syndrome: an overview. Clin Interv Aging 2014, 19, 433–441. [Google Scholar]

- Lorente, V.; Ariza-solé, A.; Jacob, J.; et al. Criterios de ingreso en unidades de críticos del paciente anciano con síndrome coronario agudo desde los servicios de urgencias hospitalarios de España. Estudio de cohorte LONGEVO-SCA 2019, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Benraad, C.E.M.; Haaksma, M.L.; Karlietis, M.H.J.; et al. Frailty as a predictor of mortality in older adults within 5 years of psychiatric admission. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2020, 35, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Mañas, L.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, B.; Carnicero, J.A.; et al. Impact of nutritional status according to GLIM criteria on the risk of incident frailty and mortality in community-dwelling older adults. Clin Nutr 2021, 40, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Abdelhafiz, A.H. Metabolic Impact of Frailty Changes Diabetes Trajectory. Metabolites; 13. Epub ahead of print 2023. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Corona, L.P.; de Oliveira Duarte, Y.A.; Lebrão, M.L. Markers of nutritional status and mortality in older adults: The role of anemia and hypoalbuminemia. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2018, 18, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, F.I.; Barthel, D.W. FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION: THE BARTHEL INDEX. Md State Med J 1965, 14, 61–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liotta, G.; Gilardi, F.; Orlando, S.; et al. Cost of hospital care for the older adults according to their level of frailty. A cohort study in the Lazio region, Italy. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0217829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Escalera, G.; Graña, M.; Irazusta, J.; et al. Mortality Risks after Two Years in Frail and Pre-Frail Older Adults Admitted to Hospital. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, H.; Wang, C.; Jiang, H.; et al. Prevalence and determinants of frailty in older adult patients with chronic coronary syndrome: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.; Vatic, M.; da Fonseca, G.W.P.; et al. Sarcopenia and Frailty in Heart Failure: Is There a Biomarker Signature? Curr Heart Fail Rep 2022, 19, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xiong, T.; Tan, X.; et al. Frailty and risk of microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes: a population-based cohort study. BMC Med 2022, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Li, X.; Lin, X.; et al. The correlation between nutrition and frailty and the receiver operating characteristic curve of different nutritional indexes for frailty. BMC Geriatr 2021, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markle-Reid, M.; Browne, G. Conceptualizations of frailty in relation to older adults. J Adv Nurs 2003, 44, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas-González, N.; López, M.; Martín-Gil, B.; et al. Relationship Between Frailty and Risk of Falls Among Hospitalised Older People with Cardiac Conditions: An Observational Cohort Study. Nurs Reports 2025, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, D.; Guasti, L.; Walker, D.; et al. Frailty in cardiology: Definition, assessment and clinical implications for general cardiology. A consensus document of the Council for Cardiology Practice (CCP), Association for Acute Cardio Vascular Care (ACVC), Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022, 29, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, A.; Kilbane, L.; Briggs, R.; et al. Screening for frailty in older emergency department patients: the utility of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe Frailty Instrument. QJM An Int J Med 2018, 111, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, P.; et al. Impact of frailty on survival and readmission in patients with gastric cancer undergoing gastrectomy: A meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ 2007, 85, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).