Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Implementation and National Coverage

Integration within SUS

Addressing Equity and Inclusion

Logic Model: A National–Global Research and Delivery Ecosystem for Menstrual Health

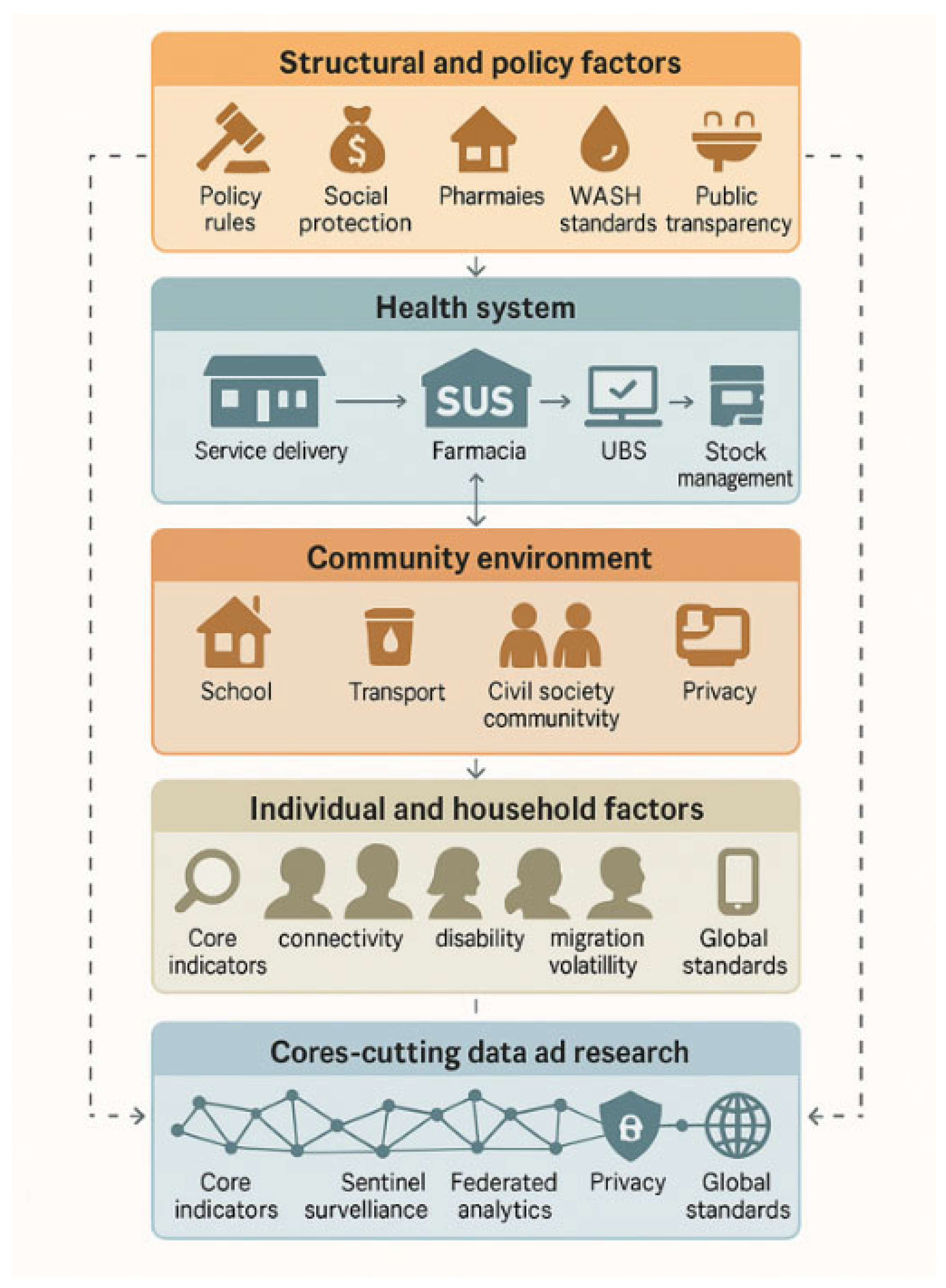

Conceptual Framework: Equity-Centred Data and Research Architecture

Structural and Policy Layer

Health System Layer (SUS Integration)

Community and Service Environment Layer

Individual and Household Layer

Data and Research Layer (Cross-Cutting Enabler)

Governance and Partnership for Global Readiness

Data and Accountability

Interpretation and Way Forward

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of interest

References

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA); United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Menstrual poverty in Brazil: inequalities and human rights violations [in Portuguese]. Brasília: UNFPA; UNICEF; 2021.

- Perucha LM, Avciño CJ, Llobet CV, Valls RT, Pinzón D, Hernández L, et al. Menstrual health and period poverty among young people who menstruate in the Barcelona metropolitan area (Spain): protocol of a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e035914. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- 3. Cobo B, Cruz C, Dick PC. Gender and racial inequalities in access to and use of Brazilian health services. Cien Saude Colet. 2021;26(9):4021–4032. [CrossRef]

- Paula MC, Monteiro BB, Ruela LO, Silva MMJ. Period poverty: a scoping review. Rev Bras Enferm. 2025;78(2):e20240567. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). State of the art for menstrual dignity promotion: advances, challenges and potentialities [in Portuguese]. Brasília: UNFPA; 2022.

- Moraes MFRC, Nunes R, Duarte I. Period poverty in Brazil: a public health emergency. Healthcare (Basel). 2025;13:1944. [CrossRef]

- Brazil. Law No. 14.214 of October 6, 2021. Establishes the Program for Protection and Promotion of Menstrual Health. Diário Oficial da União. 2021 Oct 7.

- Brazil. Decree No. 11.432 of March 8, 2023. Regulates Law No. 14.214 of October 6, 2021. Diário Oficial da União. 2023 Mar 9.

- Brazil. Ministry of Health; Ministry of Women; Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship; Ministry of Education; Ministry of Social Development and Fight Against Hunger; Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Menstrual Dignity Program – Brazil 2024 [in Portuguese]. Brasília: Federal Government of Brazil; 2024.

- Brazil. Ministry of Health. Farmácia Popular served more than 24 million Brazilians in 2024, the highest number in history [Internet]. Brasília: Ministry of Health; 2025 Jan 14 [cited 2025 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2025/janeiro/farmacia-popular-amplia-atendimento-e-chega-a-mais-de-400-novos-municipios.

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Recommendations for implementing menstrual dignity initiatives [in Portuguese]. Brasília: UNFPA; 2023.

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). 2022 Demographic Census: preliminary results [in Portuguese]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2022 [cited 2025 Sept 14]. Available from: https://censo2022.ibge.gov.br.

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Household Budget Survey 2017–2018: analysis of individual food consumption in Brazil [in Portuguese]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2020 [cited 2025 Sept 14].

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). National Health Survey 2013: perception of health status, lifestyle and chronic diseases [in Portuguese]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2014 [cited 2025 Sept 16].

- Brazil. Ministry of Social Development and Fight Against Hunger. Basic concepts: Unified Registry [in Portuguese]. Brasília: MDS; 2023 [cited 2025 Sept 19].

- Soeiro RE, Rocha L, Surita F, Bahamondes L, Costa ML. Period poverty: menstrual health and hygiene issues among adolescent and young Venezuelan migrant women at the northwestern border of Brazil. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1).

- Marques FH. Menstrual poverty among homeless women [dissertation in Portuguese]. Maringá (PR): Unicesumar; 2024.

- Gupta K, et al. Menstrual health experiences of adolescents in institutional care. SAGE Open. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Adane Y, et al. Assessment of barriers towards menstrual hygiene management: a systematic approach. Front Reprod Health. 2024.

- Machado CV, Lima LD, Andrade CLT. Political struggles for a universal health system in Brazil. Glob Health. 2019;15(1):116. [CrossRef]

- Massuda A, Hone T, Leles FAG, de Castro MC, Atun R. The Brazilian health system at crossroads: progress, crisis and resilience. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(4):e000829. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira SKS, Sene IJ Jr. Digital inclusion analysis for Brazil’s unified health system. J Health Inform. 2023;15(2):65–74. [CrossRef]

- Chinyama J, Chipungu J, Rudd C, Mwale M, Verstraete L, Sikamo C, et al. Menstrual hygiene management in rural schools of Zambia: a descriptive study of knowledge, experiences, and challenges faced by schoolgirls. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:16. [CrossRef]

- Jayathissa P, Hewapathirana R. Enhancing interoperability among health information systems in low- and middle-income countries: a review of challenges and strategies. arXiv [preprint]. 2023. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.12326.

- Brazil. Ministry of Health. OpenDataSUS: Open data platform of the Unified Health System (SUS) [Internet, in Portuguese]. Brasília: Ministry of Health; [cited 2025 Sept 18]. Available from: https://opendatasus.saude.gov.br.

| Element | What it includes | Exemplars for Brazil | Measurable indicators |

| Inputs | Political mandate; interministerial governance; SUS primary care and Farmácia Popular networks; CadÚnico and Meu SUS Digital rails; IBGE and school WASH datasets; ethics/IRB capacity; academic consortia; civil-society and youth groups; secure data infrastructure and analytics capacity | Ministry of Health, Education, Justice, Human Rights; municipal health secretariats; universities; community health workers; UNICEF/UNFPA collaborations | Annual programme budget; number of accredited dispensing points per 10,000 girls 10–19; IRB turnaround time; number of trained field researchers; active data-sharing agreements |

| Activities | Standardise national research core set; strengthen sampling frames; integrate routine data with periodic surveys; mixed-methods studies; school-based WASH auditsa; equity-focused implementation research; capacity-building for data management and open science; translation to policy briefs; global study alignment | Annual school and UBS sentinel sites; qualitative panels with Indigenous and quilombola communities; pragmatic trials on access pathways; data stewardship training; pre-registration of protocols | Proportion of studies using the national core set; share of studies with pre-registered protocols; number of sentinel schools/UBS per region; proportion of projects with community co-production plans |

| Outputs | Curated, de-identified datasets; harmonised indicators; disaggregated dashboards; validated survey tools in Portuguese and Indigenous languages; technical reports; policy briefs; open code repositories; co-authored publications with subnational data | Menstrual-health observatory; Git-hosted codebooks and analysis scripts; bilingual instrument library | Datasets published to an open catalogue; median data release latency; number of instruments validated; number of policy briefs tabled in interministerial meetings |

| Short-term outcomes (1–2 years) | Complete, comparable coverage and equity metrics; reduced administrative exclusion; better targeting in low-pharmacy and remote municipalities; improved school WASH remediation plans | UBS dispensing added where pharmacy density is low; offline authorisation via CHWs; published WASH remediation timelines | Authorisations issued and redeemed per 1,000 eligible, by age, race/colour, disability, municipality; stock-out rate; school WASH adequacy score; absenteeism due to menstruation |

| Medium-term outcomes (3–5 years) | More representative national research portfolio; Brazil enrolled in multi-country consortia with interoperable data; routine use of findings in policy; decline in stigma and missed school/work days | Brazil leading a regional node for Latin America; pooled analyses with standard metadata | Share of studies with intersectional disaggregation; proportion of global trials including Brazilian sites; effect sizes for reduced absenteeism and improved well-being |

| Impact (5+ years) | Menstrual dignity embedded in universal health coverage; resilient, equitable systems; Brazil recognised as a global evidence leader; transferable methods adopted by other LMICs | Sustainable financing line, enduring observatory, standing global collaborations | Reduction in inequity gaps between North/Northeast and South/Southeast on key indicators; independent evaluations showing sustained coverage and quality |

| Domain | Components | Purpose and Expected Outcomes |

| Mechanisms of Change and Evidence Pathways | Coverage pathway – eligibility → authorisation → redemption → continuity of supply | Ensure eligible individuals receive timely, continuous access to menstrual products, minimising drop-off points. |

| Usability pathway – products + WASH + disposal + privacy | Improve safe and dignified menstrual management, reduce infections and stigma, and increase school attendance and participation. | |

| Equity pathway – intersectional identification of barriers and tailored delivery | Reduce regional and demographic disparities through targeted service delivery via UBS, schools, and community health workers. | |

| Learning pathway – routine dashboards, sentinel studies, mixed-methods research | Enable adaptive programme management through continuous, real-time feedback loops. | |

| Globalisation pathway – adoption of common data dictionaries and metadata standards | Position Brazil to participate in multi-country research and align with global menstrual health datasets. | |

| Core Indicators and Measurement Standards | Access and continuity – authorisations issued and redeemed per 1,000 eligible; median time from eligibility to first redemption; refill regularity; stock-outs per site-month | Measure programme reach, timeliness, and supply chain reliability. |

| Equity – disaggregation by age, race/colour, region, municipality, disability, school enrolment, migration status, socioeconomic deprivation | Identify inequities and monitor whether vulnerable populations are being reached. | |

| Usability and environment – school WASH adequacy index, safe disposal availability, travel time to dispensing points or UBS, digital access proxies | Assess environmental factors influencing menstrual product use and programme usability. | |

| Outcomes – menstruation-related absenteeism, self-reported stigma, infection proxies, validated quality-of-life scales in Portuguese and Indigenous languages | Track health, social, and educational outcomes linked to menstrual health. | |

| Data quality – completeness, timeliness, concordance across sources, pre-registered protocols, reproducible code availability | Ensure high-quality, transparent, and reliable data. | |

| Study Designs and Data Architecture | Sentinel surveillance – stratified schools and UBS with oversampling of remote and marginalised populations | Generate real-time, representative data across diverse geographies and communities. |

| Periodic population surveys – rotating panels with intersectional modules, using mixed modes (in-person, phone, digital) | Capture longitudinal trends and reduce exclusion through flexible data collection methods. | |

| Implementation research – pragmatic trials comparing delivery models and WASH-linked interventions | Evaluate effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different service models, focusing on school absenteeism and participation. | |

| Qualitative inquiry – longitudinal ethnographic studies and youth advisory panels | Understand social norms, stigma, and lived experiences to refine interventions. | |

| Data linkage – privacy-preserving connections between dispensing, primary care, school health, and WASH data | Enable comprehensive analyses without moving raw, sensitive data. | |

| Open science practices – pre-registration, publicly archived analytic code, de-identified datasets | Promote transparency, reproducibility, and international collaboration. |

| Priority | Concrete actions | Success indicators |

| National core indicator set | Publish a harmonised dictionary, disaggregation rules, and survey modules; mandate use in funded studies | ≥80% of new studies adopt the core set; inter-study comparability achieved |

| Sentinel network and dashboards | Establish sentinel sites in schools and UBS across all macro-regions; develop public dashboards with equity disaggregation | Dashboards refreshed monthly; measurable reductions in equity gaps |

| Inclusive delivery models | Introduce UBS on-site dispensing; enable offline authorisation by community health workers; provide transport vouchers in low-density areas | Redemption parity between remote and urban municipalities; reduced travel time |

| WASH-linked integration | Link product provision to school WASH audits and remediation funds; develop standard disposal protocols | Increase in schools meeting WASH standards; decline in menstruation-related absenteeism |

| Ethics, privacy, and open science | Develop data protection frameworks; use federated analytics; promote pre-registration and open data practices | Faster data-sharing agreements; higher proportion of pre-registered studies |

| Global interoperability | Align indicators and metadata with global research standards; contribute to international data repositories | Increase in Brazil’s participation in multi-country projects and publications |

| Workforce and community capacity | Build a national training pipeline for researchers and field teams; establish community and youth co-production panels | Trained researchers per state; proportion of projects with documented co-production plans |

| Action area | Recommended measures |

| Closing the last-mile gap | Introduce on-site dispensing at UBS facilities in areas with few pharmacies. Enable community health workers to generate authorisations offline and support initial product redemption. |

| Linking products to WASH improvements | Integrate funding for upgrading school toilets, water access, and disposal facilities. Conduct regular audits and publish remediation timelines, prioritising the North and Northeast regions. |

| Reducing administrative exclusion | Enhance outreach to register vulnerable populations, including undocumented individuals and migrants. Simplify identification requirements for those in street situations or lacking official documents. |

| Transparent monitoring and reporting | Establish a national dashboard showing coverage rates, demographic disaggregation (age, race, municipality), stock-outs, and supply continuity. Commission independent evaluations of programme impacts on school attendance, infections, and stigma. |

| Strengthening governance and cross-sectoral collaboration | Maintain interministerial coordination, including ministries of Health, Education, Justice, and Human Rights, and extend collaboration to include sanitation and infrastructure sectors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).